Submitted:

07 April 2024

Posted:

08 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathogenesis

3. Kidney Graft Involvement

4. Immune Response

4.1. Humoral Immune Response

4.2. Cellular Immune Response

5. Diagnosis

5.1. Urine Cytology

5.2. BKPyV Viruria

5.3. BKPyV Viremia

5.4. BKPyV-Specific Cell Immune Monitoring

5.5. Allograft Biopsy

6. Risk Factors of BKPyV Nephropathy in the Immunosuppressed Patient

6.1. Immunosuppression

6.2. Other Risk Factors

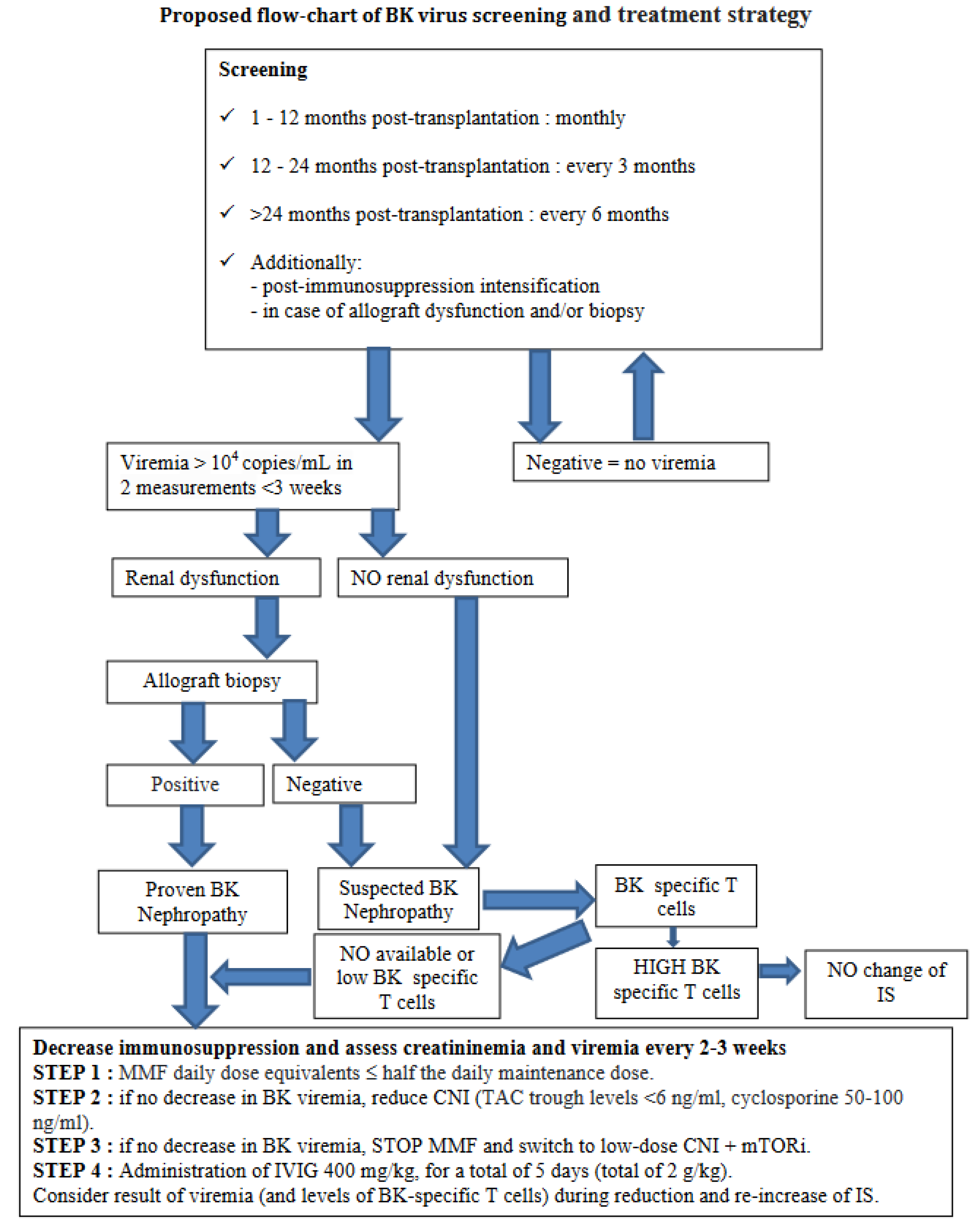

7. How to Manage BKPyV in Pediatric Kidney Transplantation

8. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moens U, Calvignac-Spencer S, Lauber C, Ramqvist T, Feltkamp MCW, Daugherty MD, Verschoor EJ, Ehlers B, Ictv Report Consortium. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol. 2017 Jun;98(6):1159-1160. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vilchez RA, Butel JS. Emergent human pathogen simian virus 40 and its role in cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004 Jul;17(3):495-508, table of contents. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gardner SD, Field AM, Coleman DV, Hulme B. New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation. Lancet. 1971 Jun 19;1(7712):1253-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgett BL, Walker DL. Prevalence of antibodies in human sera against JC virus, an isolate from a case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis. 1973 Apr;127(4):467-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCaprio JA, Garcea RL. A cornucopia of human polyomaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013 Apr;11(4):264-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goudsmit J, Wertheim-van Dillen P, van Strien A, van der Noordaa J. The role of BK virus in acute respiratory tract disease and the presence of BKV DNA in tonsils. J Med Virol. 1982;10(2):91-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolt A, Sasnauskas K, Koskela P, Lehtinen M, Dillner J. Seroepidemiology of the human polyomaviruses. J Gen Virol. 2003 Jun;84(Pt 6):1499-1504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldorini R, Veggiani C, Barco D, Monga G. Kidney and urinary tract poyomavirus infection and distribution: molecular biology investigation of 10 consecutive autopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005 Jan;129(1):69-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma R, Tzetzo S, Patel S, Zachariah M, Sharma S, Melendy T. BK Virus in Kidney Transplant: Current Concepts, Recent Advances, and Future Directions. Exp Clin Transplant. 2016 Aug;14(4):377-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch HH, Knowles W, Dickenmann M, Passweg J, Klimkait T, Mihatsch MJ, Steiger J. Prospective study of polyomavirus type BK replication and nephropathy in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 15;347(7):488-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuypers DR. Management of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy in renal transplant recipients. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012 Apr 17;8(7):390-402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt C, Raggub L, Linnenweber-Held S, Adams O, Schwarz A, Heim A. Donor origin of BKV replication after kidney transplantation. J Clin Virol. 2014 Feb;59(2):120-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gras J, Nere ML, Peraldi MN, Bonnet-Madin L, Salmona M, Taupin JL, Desgrandchamps F, Verine J, Brochot E, Amara A, Molina JM, Delaugerre C. BK virus genotypes and humoral response in kidney transplant recipients with BKV associated nephropathy. Transpl Infect Dis. 2023 Apr;25(2):e14012. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mineeva-Sangwo O, Martí-Carreras J, Cleenders E, Kuypers D, Maes P, Andrei G, Naesens M, Snoeck R. Polyomavirus BK Genome Comparison Shows High Genetic Diversity in Kidney Transplant Recipients Three Months after Transplantation. Viruses. 2022 Jul 14;14(7):1533. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosen S, Harmon W, Krensky AM, Edelson PJ, Padgett BL, Grinnell BW, Rubino MJ, Walker DL. Tubulo-interstitial nephritis associated with polyomavirus (BK type) infection. N Engl J Med. 1983 May 19;308(20):1192-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunderink HF, van der Meijden E, van der Blij-de Brouwer CS, Mallat MJ, Haasnoot GW, van Zwet EW, Claas EC, de Fijter JW, Kroes AC, Arnold F, Touzé A, Claas FH, Rotmans JI, Feltkamp MC. Pretransplantation Donor-Recipient Pair Seroreactivity Against BK Polyomavirus Predicts Viremia and Nephropathy After Kidney Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017 Jan;17(1):161-172. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solis M, Velay A, Porcher R, Domingo-Calap P, Soulier E, Joly M, Meddeb M, Kack-Kack W, Moulin B, Bahram S, Stoll-Keller F, Barth H, Caillard S, Fafi-Kremer S. Neutralizing Antibody-Mediated Response and Risk of BK Virus-Associated Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Jan;29(1):326-334. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dakroub F, Touzé A, Sater FA, Fiore T, Morel V, Tinez C, Helle F, François C, Choukroun G, Presne C, Guillaume N, Duverlie G, Castelain S, Akl H, Brochot E. Impact of pre-graft serology on risk of BKPyV infection post-renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022 Mar 25;37(4):781-788. Erratum in: Nephrol Dial Transplant. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariharan S, Cohen EP, Vasudev B, Orentas R, Viscidi RP, Kakela J, DuChateau B. BK virus-specific antibodies and BKV DNA in renal transplant recipients with BKV nephritis. Am J Transplant. 2005 Nov;5(11):2719-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Y, Trofe J, Gordon J, Du Pasquier RA, Roy-Chaudhury P, Kuroda MJ, Woodle ES, Khalili K, Koralnik IJ. Interplay of cellular and humoral immune responses against BK virus in kidney transplant recipients with polyomavirus nephropathy. J Virol. 2006 Apr;80(7):3495-505. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schachtner T, Stein M, Sefrin A, Babel N, Reinke P. Inflammatory actvation and recovering BKV-specific immunity correlate with self-limited BKV replication after renal transplantation. Transpl Int. 2014 Mr;27(3):290-301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leboeuf C, Wilk S, Achermann R, Binet I, Golshayan D, Hadaya K, Hirzel C, Hoffmann M, Huynh-Do U, Koller MT, Manuel O, Mueller NJ, Mueller TF, Schaub S, van Delden C, Weissbach FH, Hirsch HH; Swiss Transplant Cohort Study. BK Polyomavirus-Specific 9mer CD8 T Cell Responses Correlate With Clearance of BK Viremia in Kidney Transplant Recipients: First Report From the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study. Am J Transplant. 2017 Oct;17(10):2591-2600. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur A, Wilhelm M, Wilk S, Hirsch HH. BK polyomavirus-specific antibody and T-cell responses in kidney transplantation: update. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2019 Dec;32(6):575-583. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond JE, Shah KV, Donnenberg AD. Cell-mediated immune responses to BK virus in normal individuals. J Med Virol. 1985 Nov;17(3):237-47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koralnik IJ, Du Pasquier RA, Letvin NL. JC virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in individuals with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Virol. 2001 Apr;75(7):3483-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leung AY, Chan M, Tang SC, Liang R, Kwong YL. Real-time quantitative analysis of polyoma BK viremia and viruria in renal allograft recipients. J Virol Methods. 2002 May;103(1):51-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosser SE, Orentas RJ, Jurgens L, Cohen EP, Hariharan S. Recovery of BK virus large T-antigen-specific cellular immune response correlates with resolution of bk virus nephritis. Transplantation. 2008 Jan 27;85(2):185-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlenstiel-Grunow T, Pape L. Diagnostics, treatment, and immune response in BK polyomavirus infection after pediatric kidney transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020 Mar;35(3):375-382. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlenstiel-Grunow T, Sester M, Sester U, Hirsch HH, Pape L. BK Polyomavirus-specific T Cells as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Marker for BK Polyomavirus Infections After Pediatric Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation. 2020 Nov;104(11):2393-2402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogazzi GB, Cantú M, Saglimbeni L. 'Decoy cells' in the urine due to polyomavirus BK infection: easily seen by phase-contrast microscopy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001 Jul;16(7):1496-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada Y, Tsuchiya T, Inagaki I, Seishima M, Deguchi T. Prediction of Early BK Virus Infection in Kidney Transplant Recipients by the Number of Cells With Intranuclear Inclusion Bodies (Decoy Cells). Transplant Direct. 2018 Feb 2;4(2):e340. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Randhawa P, Vats A, Shapiro R. Monitoring for polyomavirus BK And JC in urine: comparison of quantitative polymerase chain reaction with urine cytology. Transplantation. 2005 Apr 27;79(8):984-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viscount HB, Eid AJ, Espy MJ, Griffin MD, Thomsen KM, Harmsen WS, Razonable RR, Smith TF. Polyomavirus polymerase chain reaction as a surrogate marker of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy. Transplantation. 2007 Aug 15;84(3):340-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höcker B, Schneble L, Murer L, Carraro A, Pape L, Kranz B, Oh J, Zirngibl M, Dello Strologo L, Büscher A, Weber LT, Awan A, Pohl M, Bald M, Printza N, Rusai K, Peruzzi L, Topaloglu R, Fichtner A, Krupka K, Köster L, Bruckner T, Schnitzler P, Hirsch HH, Tönshoff B. Epidemiology of and Risk Factors for BK Polyomavirus Replication and Nephropathy in Pediatric Renal Transplant Recipients: An International CERTAIN Registry Study. Transplantation. 2019 Jun;103(6):1224-1233. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch HH, Babel N, Comoli P, Friman V, Ginevri F, Jardine A, Lautenschlager I, Legendre C, Midtvedt K, Muñoz P, Randhawa P, Rinaldo CH, Wieszek A; ESCMID Study Group of Infection in Compromised Hosts. European perspective on human polyomavirus infection, replication and disease in solid organ transplantation. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014 Sep;20 Suppl 7:74-88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch HH, Randhawa PS; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. BK polyomavirus in solid organ transplantation-Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019 Sep;33(9):e13528. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleenders E, Koshy P, Van Loon E, Lagrou K, Beuselinck K, Andrei G, Crespo M, De Vusser K, Kuypers D, Lerut E, Mertens K, Mineeva-Sangwo O, Randhawa P, Senev A, Snoeck R, Sprangers B, Tinel C, Van Craenenbroeck A, van den Brand J, Van Ranst M, Verbeke G, Coemans M, Naesens M. An observational cohort study of histological screening for BK polyomavirus nephropathy following viral replication in plasma. Kidney Int. 2023 Nov;104(5):1018-1034. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfadawy N, Flechner SM, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Poggio E, Fatica R, Avery R, Mossad SB. Transient versus persistent BK viremia and long-term outcomes after kidney and kidney-pancreas transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Mar;9(3):553-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alméras C, Foulongne V, Garrigue V, Szwarc I, Vetromile F, Segondy M, Mourad G. Does reduction in immunosuppression in viremic patients prevent BK virus nephropathy in de novo renal transplant recipients? A prospective study. Transplantation. 2008 Apr 27;85(8):1099-104. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schachtner T, Stein M, Babel N, Reinke P. The Loss of BKV-specific Immunity From Pretransplantation to Posttransplantation Identifies Kidney Transplant Recipients at Increased Risk of BKV Replication. Am J Transplant. 2015 Aug;15(8):2159-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickeleit V, Singh HK, Randhawa P, Drachenberg CB, Bhatnagar R, Bracamonte E, Chang A, Chon WJ, Dadhania D, Davis VG, Hopfer H, Mihatsch MJ, Papadimitriou JC, Schaub S, Stokes MB, Tungekar MF, Seshan SV; Banff Working Group on Polyomavirus Nephropathy. The Banff Working Group Classification of Definitive Polyomavirus Nephropathy: Morphologic Definitions and Clinical Correlations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Feb;29(2):680-693. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Masutani K, Shapiro R, Basu A, Tan H, Wijkstrom M, Randhawa P. The Banff 2009 Working Proposal for polyomavirus nephropathy: a critical evaluation of its utility as a determinant of clinical outcome. Am J Transplant. 2012 Apr;12(4):907-18. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Drachenberg CB, Papadimitriou JC, Hirsch HH, Wali R, Crowder C, Nogueira J, Cangro CB, Mendley S, Mian A, Ramos E. Histological patterns of polyomavirus nephropathy: correlation with graft outcome and viral load. Am J Transplant. 2004 Dec;4(12):2082-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharnidharka VR, Cherikh WS, Abbott KC. An OPTN analysis of national registry data on treatment of BK virus allograft nephropathy in the United States. Transplantation. 2009 Apr 15;87(7):1019-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gately R, Milanzi E, Lim W, Teixeira-Pinto A, Clayton P, Isbel N, Johnson DW, Hawley C, Campbell S, Wong G. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Kidney Transplant Recipients With BK Polyomavirus-Associated Nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2022 Dec 30;8(3):531-543. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hirsch HH, Vincenti F, Friman S, Tuncer M, Citterio F, Wiecek A, Scheuermann EH, Klinger M, Russ G, Pescovitz MD, Prestele H. Polyomavirus BK replication in de novo kidney transplant patients receiving tacrolimus or cyclosporine: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Transplant. 2013 Jan;13(1):136-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel H, Rodig N, Agrawal N, Cardarelli F. Incidence and risk factors of kidney allograft loss due to BK nephropathy in the pediatric population: A retrospective analysis of the UNOS/OPTN database. Pediatr Transplant. 2021 Aug;25(5):e13927. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer IR, Wagener ME, Robertson JM, Turner AP, Araki K, Ahmed R, Kirk AD, Larsen CP, Ford ML. Cutting edge: Rapamycin augments pathogen-specific but not graft-reactive CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol. 2010 Aug 15;185(4):2004-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McCabe MT, Low JA, Imperiale MJ, Day ML. Human polyomavirus BKV transcriptionally activates DNA methyltransferase 1 through the pRb/E2F pathway. Oncogene. 2006 May 4;25(19):2727-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liacini A, Seamone ME, Muruve DA, Tibbles LA. Anti-BK virus mechanisms of sirolimus and leflunomide alone and in combination: toward a new therapy for BK virus infection. Transplantation. 2010 Dec 27;90(12):1450-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouve T, Rostaing L, Malvezzi P. Place of mTOR inhibitors in management of BKV infection after kidney transplantation. J Nephropathol. 2016 Jan;5(1):1-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suwelack B, Malyar V, Koch M, Sester M, Sommerer C. The influence of immunosuppressive agents on BK virus risk following kidney transplantation, and implications for choice of regimen. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2012 Jul;26(3):201-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallat SG, Tanios BY, Itani HS, Lotfi T, McMullan C, Gabardi S, Akl EA, Azzi JR. CMV and BKPyV Infections in Renal Transplant Recipients Receiving an mTOR Inhibitor-Based Regimen Versus a CNI-Based Regimen: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 Aug 7;12(8):1321-1336. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berger SP, Sommerer C, Witzke O, Tedesco H, Chadban S, Mulgaonkar S, Qazi Y, de Fijter JW, Oppenheimer F, Cruzado JM, Watarai Y, Massari P, Legendre C, Citterio F, Henry M, Srinivas TR, Vincenti F, Gutierrez MPH, Marti AM, Bernhardt P, Pascual J; TRANSFORM investigators. Two-year outcomes in de novo renal transplant recipients receiving everolimus-facilitated calcineurin inhibitor reduction regimen from the TRANSFORM study. Am J Transplant. 2019 Nov;19(11):3018-3034. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscarelli L, Caroti L, Antognoli G, Zanazzi M, Di Maria L, Carta P, Minetti E. Everolimus leads to a lower risk of BKV viremia than mycophenolic acid in de novo renal transplantation patients: a single-center experience. Clin Transplant. 2013 Jul-Aug;27(4):546-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz VT, Kisaoglu A, Avanaz A, Dandin O, Ozel D, Mutlu D, Akkaya B, Aydinli B, Kocak H. Predictive Factors of BK Virus Development in Kidney Transplant Recipients and the Effect of Low-Dose Tacrolimus Plus Everolimus on Clinical Outcomes. Exp Clin Transplant. 2023 Sep;21(9):727-734. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatas M, Tatar E, Okut G, Yildirim AM, Kocabas E, Tasli Alkan F, Simsek C, Dogan SM, Uslu A. Efficacy of mTOR Inhibitors and Intravenous Immunoglobulin for Treatment of Polyoma BK Nephropathy in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Biopsy-Proven Study. Exp Clin Transplant. 2024 Jan;22(Suppl 1):118-127. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sener A, House AA, Jevnikar AM, Boudville N, McAlister VC, Muirhead N, Rehman F, Luke PP. Intravenous immunoglobulin as a treatment for BK virus associated nephropathy: one-year follow-up of renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2006 Jan 15;81(1):117-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu SW, Chang HR, Lian JD. The effect of low-dose cidofovir on the long-term outcome of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 Mar;24(3):1034-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy G, Erkan M, Koyun M, Çomak E, Toru HS, Mutlu D, Akkaya B, Akman S. Treatment of BK Polyomavirus-Associated Nephropathy in Paediatric Kidney Transplant Recipients: Leflunomide Versus Cidofovir. Exp Clin Transplant. 2024 Jan;22(1):29-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faguer S, Hirsch HH, Kamar N, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Ribes D, Guitard J, Esposito L, Cointault O, Modesto A, Lavit M, Mengelle C, Rostaing L. Leflunomide treatment for polyomavirus BK-associated nephropathy after kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2007 Nov;20(11):962-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung YH, Moon KC, Ha JW, Kim SJ, Ha IS, Cheong HI, Kang HG. Leflunomide therapy for BK virus allograft nephropathy after pediatric kidney transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2013 Mar;17(2):E50-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araya CE, Garin EH, Neiberger RE, Dharnidharka VR. Leflunomide therapy for BK virus allograft nephropathy in pediatric and young adult kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2010 Feb;14(1):145-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pape L, Tönshoff B, Hirsch HH; Members of the Working Group ‘Transplantation’ of the European Society for Paediatric Nephrology. Perception, diagnosis and management of BK polyomavirus replication and disease in paediatric kidney transplant recipients in Europe. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 May;31(5):842-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).