1. Background of the Study

In higher education programs, the development of research competency is a major milestone in students’ curriculum due to its potential to instill critical thinking and transition students into the professional workforce [

1]. A pivotal aspect of research competency development lies in statistics, given its fundamental role in analyzing data to support research findings [

2]. For example, researchers need descriptive statistics to summarize characteristics of the data, while inferential statistics makes inferences of the population from the sample at hand to test hypotheses and answer research questions [

2,

3]. At a more advanced level, structural equation modeling (SEM), a multivariate statistical technique, is often utilized to examine relationships between variables of interest [

4]. Despite its significance, statistics components are often perceived as challenging by students [

5]. This difficulty is attributed to the mathematical components inherent in statistics, which might pose comprehension challenges compared to content that focuses on facts and ideas [

6,

7].

In fact, a considerable number of students who learn statistics belong to majors outside mathematics or statistics, such as political science or psychology [

8]. The challenges faced by these students in statistics courses could induce subject-related anxiety, highlighting the struggle in grasping statistical concepts [

5,

9]. It is established that students’ proficiency in statistics, as represented by their formative assessment scores, can determine their overall performance in the statistics course [

9,

10]. However, whether students’ statistical proficiency can predict their research competency, as reflected by their final scores in a research methods course, has yet to be examined. In response to this gap, we performed an investigation to identify specific statistical topics that can predict students’ final course grades in a research methods course. This investigation seeks to identify areas of importance, providing a foundation for a strategic approach to emphasize and refine relevant topics in the statistics course.

To fulfill the aim of our research, we employed a supervised machine learning model to identify influential predictors of students’ performance in a research method class. The overarching research question is: "

How is the predictability of skills in statistics to students’ research competency?” The predictor variables are students’ formative scores in each topic from a statistics course, as well as their learning behavior in the statistics course as auxiliary variables. The outcome variable is students’ learning performance in the research method class. Results from the analysis include a predictive regression model for students’ final course score in a research method course, a predictive classification model for students’ success in the research method course, and lists of important predictors to the targeted variable as well as their influence on the prediction. While predicting students’ statistical competency is more directly related to the predictors, predicting students’ research competency may allow us to extrapolate the results to examine how well students can practically apply statistical concepts to real-world research scenarios, especially in research-oriented professions [

11].

Instead of relying on traditional statistical analysis for retrospective inference, we employed a machine learning approach to predict students’ research competency. This approach offers an algorithm and predictors as a guideline to inform instructors in developing their course designs on the research methods topics [

12]. Furthermore, this study contributes to the body of knowledge by identifying topics in statistics that are crucial in determining students’ research competency. Ideally, instructors should ensure that students understand every topic of the course material. However, it is impractical to deliver the entire course content at a detailed yet slow pace, considering the time limit of a standard program. Such a program typically allows a maximum of three teaching hours per day over a 16-week semester [

13]. This research could highlight the topics in statistics that need more emphasis to increase efficiency in developing students’ research competency. By investing time and resources into enhancing the accessibility of these topics, instructors could enhance students’ background knowledge in statistics and consequently their competency in the research methods course.

4. Methods

4.1. Dataset, Feature selection, and Data Preprocessing

The dataset utilized in this study encompasses undergraduate students’ profiles from both a statistics course and a research methods course at a Thai university, totaling N = 385 participants. Data preprocessing and predictive model development primarily relied on the R programming language [

23]. The variables of interest were derived as by products of student assessment performance across their university study. Assessments were conducted in Thai, the official language and medium of instruction at the university.

Table 1 describes a list of variables utilized in this study and their code. The dataset utilized in this study is classified as secondary data due to its its anonymity to the primary researchers. This ensures minimal ethical concerns as there exists no feasible method for re-identifying the participants.

For feature selection, statistics topics were categorized into three main categories: 1. Interpretation, which includes topics involved in translating and summarizing the analysis results from data (i.e., describing the data distribution, analyzing the relationship between variables using statistical measures and data visualizations, and interpreting results from hypothesis testing such as t-test or ANOVA. 2. Concept, comprising topics involving essential theories and principles of statistical methods such as sampling distributions, estimation, and hypothesis testing. This category also covers the understanding of statistical assumptions for statistical tests, the rationale behind different types of data scales (nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio), and the conceptual framework for choosing appropriate statistical tests based on research questions and data characteristics. 3. Method Selection, involving the practical application of statistical techniques and decision-making processes to choose the most suitable methods for data analysis based on the nature of data and research objective. Specifically, this category includes selecting the correct types of t-tests (one-sample, independent, or paired-sample), choosing between parametric and non-parametric tests based on data distribution and sample size, deciding on the appropriate correlation coefficients (Pearson, Spearman, or Cramer’s V) to examine the strength and direction of relationships between variables, and selecting the appropriate regression model for predicting outcomes or explaining the relationship between multiple variables.

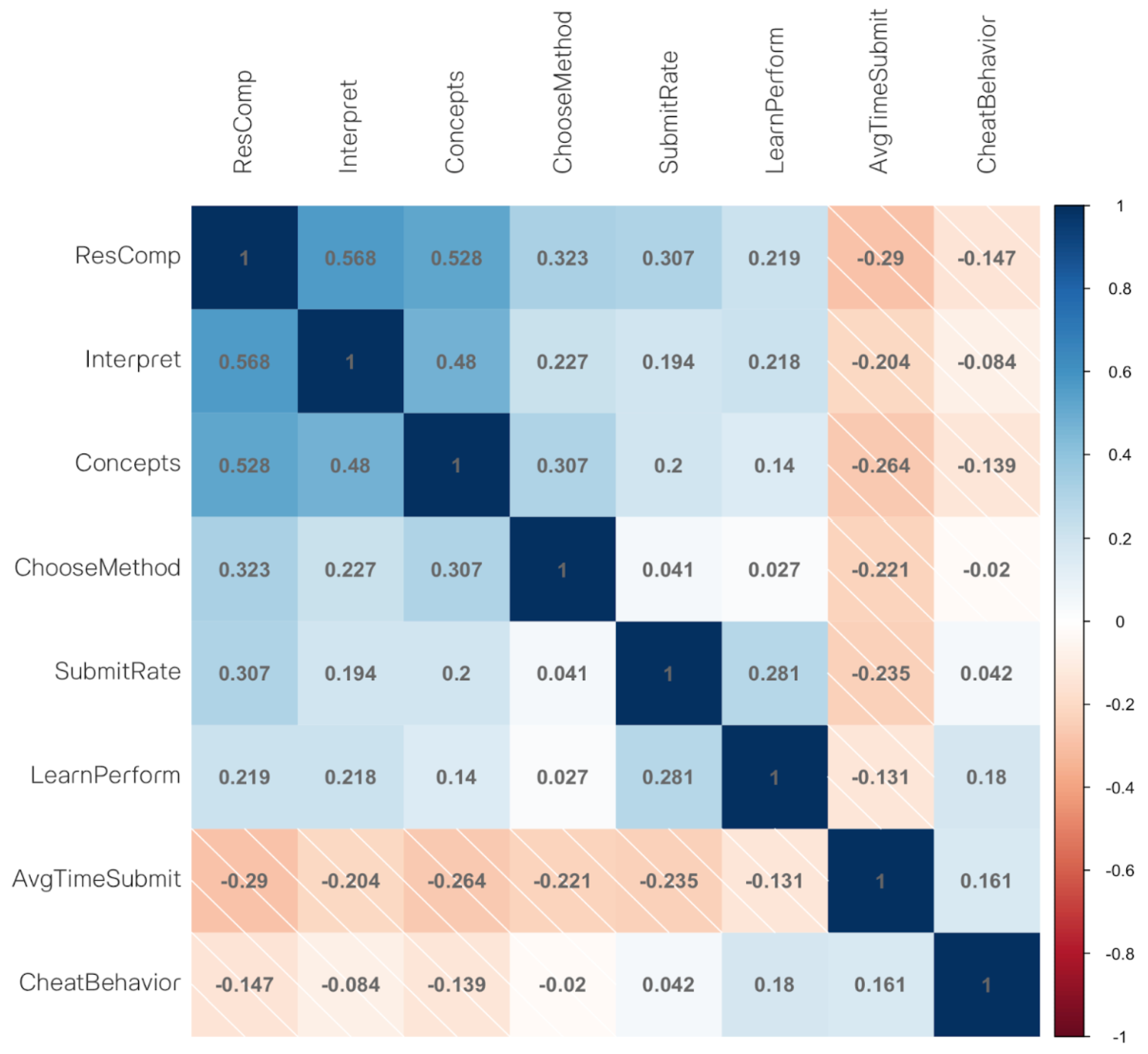

Predictors that account for students’ background comprised four variables as follows: First, students’ time taken to complete the assignment, represented by their average time of submission. Second, students’ submission rate (whether students submitted the assignment). Third, students’ post-lecture quiz performance, represented by average score of post-class exercise in each lecture. These exercises are designed to assess the understanding of the lecture, providing a measure of students’ attention to the concepts taught in class. Finally, students’ cheating behavior is indicated by the median cosine similarity among their open-ended homework responses. A value close to 1.00 means a student’s work is very similar to others’, hinting at possible plagiarism. In total, seven variables served as predictors in this study. All of these variables were continuous. The outcome variable is students’ final course score in the research method course for the regression task. For the classification task, the score was categorized into two classes, with class 1 represents students who achieve 80% and above in the final research method course grade and class 0 represents students who achieve below 80% in the final research method course grade. All predictors were examined with a correlational analysis to ensure their relationships among each other and relationships to the outcome variable.

In terms of data preprocessing, one case exhibited missing values, which were addressed using bootstrap aggregating trees imputation technique via the recipe package [

24]. We conducted the train-test split procedure using the

initial split function from the rsample package [

24], with a split ratio of 80% for training data and 20% for testing data. For the classification task, there was a 60:248 discrepancy between the number of instances in class 1 and class 0 respectively, indicating a moderate class imbalance issue. To mitigate this, we employed the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) from the themis package [

25]. SMOTE synthesized additional instances of the minority class (class 1), resulting in a balanced class proportion of N = 248 for each class in the final dataset used for classification. The final dataset for the classification task comprised 419 instances for training and 77 for testing datasets. For the regression task, the final dataset consisted of 308 instances for training and 77 instances for testing datasets.

4.2. Predictive Algorithm

For predicting the outcome variable, we employed the Elastic-net regularized generalized linear model (GLM) as our predictive algorithm [

26,

27]. This choice was made after comparing various predictive algorithms for both regression and classification tasks, including Random forest, k-nearest neighbor, support vector machine, and extreme gradient boosting trees. These algorithms yielded comparable results. However, the Elastic-net GLM possesses an advantage of interpretability. Given its linear nature, this model allows for clear interpretation of how predictors influence the outcome variable directionally [

26]. Additionally, linear models, like the Elastic-net GLM, have been shown to perform well with small sample sizes compared to ensemble models such as Random Forest [

28]. This advantage is further enhanced by the quality of the data, as variables were meticulously selected based on their pairwise relationships [

29]. By employing the Elastic-net GLM, our aim is to leverage its interpretability and effectiveness in modeling the relationship between predictors and the outcome variable.

4.3. Hyperparameter Tuning

To optimize both the regression and classification algorithms, the Latin Hypercube grid search method was utilized for its efficiency, offering comparable results to other approaches but at a lower computational cost [

30,

31]. The tuned hyperparameters are Elastic-net penalty terms and mixing parameters, both possessing the range of 0 to 1. Both algorithms were with 50 sets of random hyperparameter values, through 10-fold cross validation with 5 repetitions method (5x10-fold CV), totalling 2,500 number of trials. Following the identification of the optimal hyperparameter combination, both regressor and classifier model underwent further training, testing, and validation using 5x10-fold CV to ensure optimal performance. The evaluation of the regression algorithm’s effectiveness was based on regression metrics such as root mean squared error (RMSE) and R-squared. For the classification algorithm, classification metrics such as area under curve (AUC), precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy were consulted.

6. Discussion

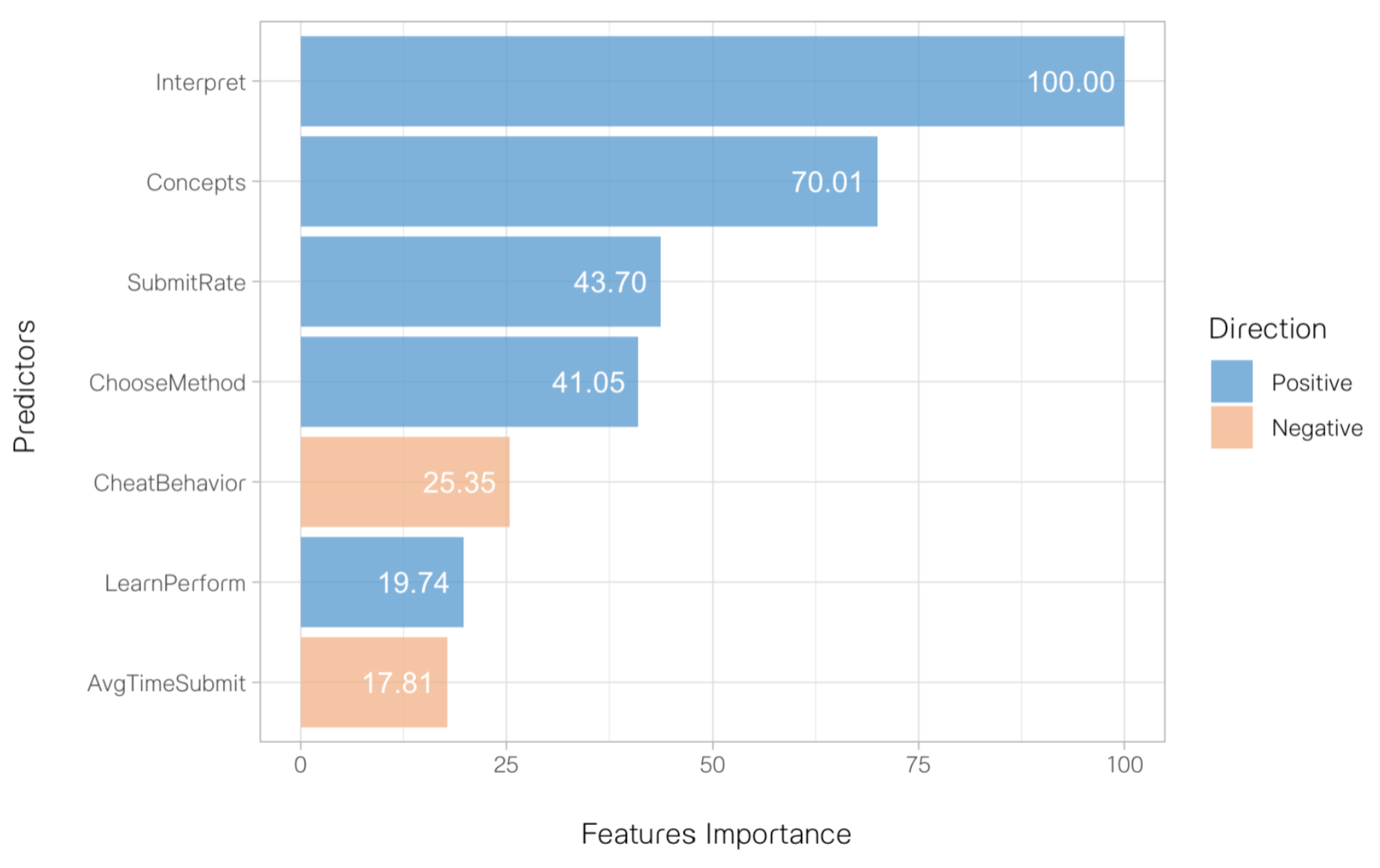

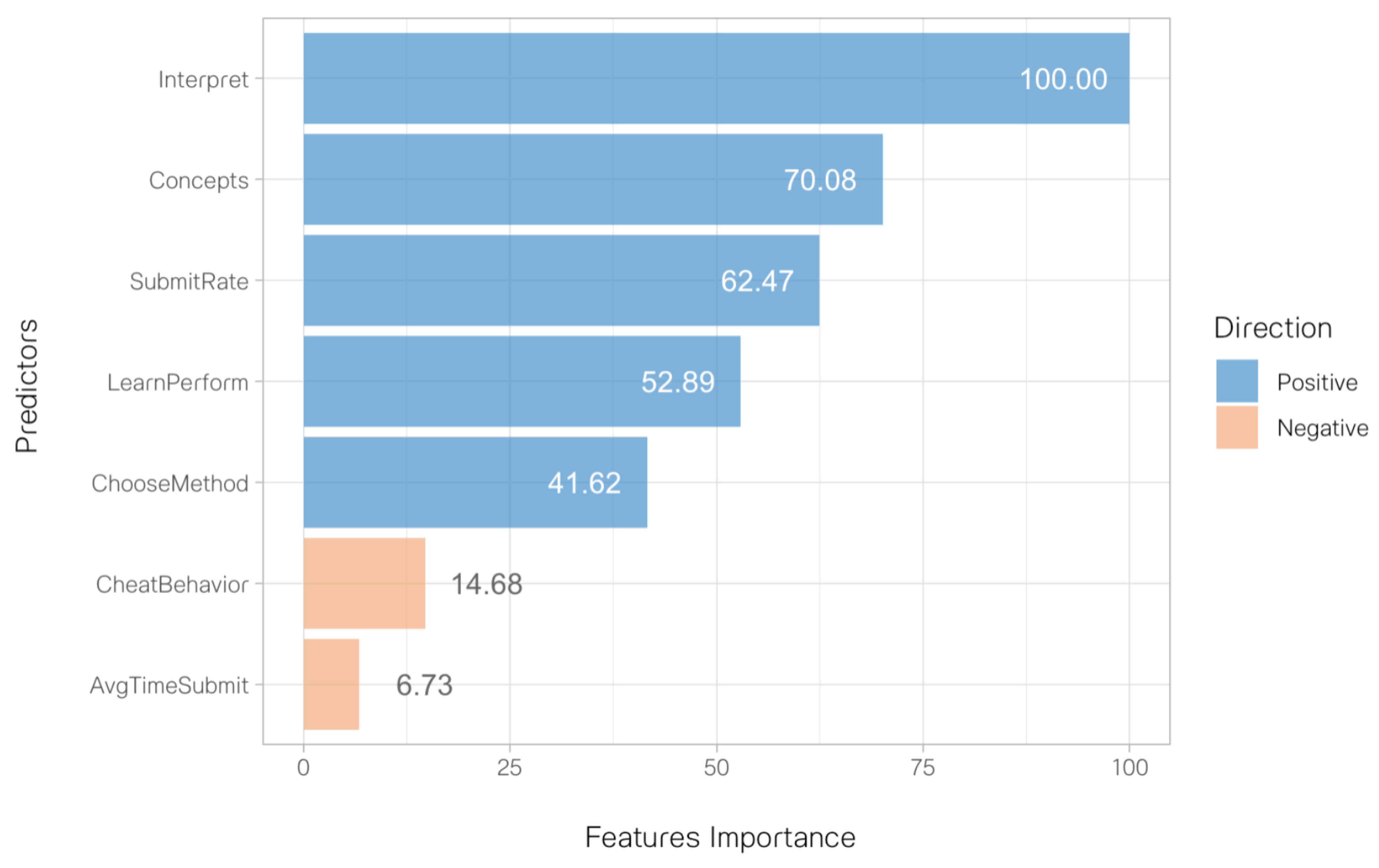

This study aims to identify key predictors among undergraduate students’ statistical skills and learning behavior within a statistics course, with the goal of predicting their research competency as represented by their performance in a research methods course. Employing supervised machine learning techniques, the research performed both regression and classification tasks to predict students’ final course scores and likelihood of achieving a letter grade of B or higher, respectively. The guiding research question is: "How is the predictability of skills in statistics to students’ research competency?" To answer the research question, our findings indicate that three primary categories of statistical skills—namely, understanding of statistical concepts, proficiency in selecting appropriate statistical methods, and statistics interpretation skills— can be used to predict students’ research competency, as demonstrated by their final course scores and letter grades. Additionally, factors related to students’ learning behavior, such as assignment submission rates, post-lecture quiz performance, and academic dishonesty, serve as supplementary predictors. Our analyses reveal that statistics interpretation skills emerge as the most influential predictor, followed by understanding of statistical concepts and method selection proficiency, respectively. These insights hold implications for instructors seeking to enhance the design of research methods courses within higher education contexts.

The findings of this study aligns with various learning theories. Specifically, the statistics interpretation skills are positioned on the evaluating and analyzing levels on Bloom’s revised taxonomy, because they involve the critical process of making sense of statistical outputs by analyzing results and assessing their quality [

32]. These two levels on Bloom’s require higher comprehension in the subject matter, and therefore could be inferred that students who mastered the statistics interpretation skills can apply their statistical knowledge more effectively in developing their research competency. Conversely, students’ grasp of statistical concepts resides at the understanding level within Bloom’s framework, which involves the ability to describe the relationship between principles of statistical methods and their underlying assumptions [

19]. Similarly, proficiency in selecting appropriate statistical methods operates primarily at the understanding and remembering levels, as students must match suitable data analysis techniques with the characteristics of their data. This skill may entail a lower level of comprehension compared to the understanding of statistical concepts, given its focus on the practical matching of data and methods rather than abstract conceptualization [

19,

32]. Consequently, it is reasonable to infer that these latter two skills may exhibit comparatively less predictive power regarding students’ research competency, as they require a lower level of comprehension in the subject matter compared to statistics interpretation skills.

The findings of this study also align with the framework of feedback levels proposed by Hattie and Timperley [

33], which distinguishes between task-level feedback (i.e., how tasks are performed) and process-level feedback (i.e., the cognitive processes necessary to execute tasks effectively). When instructing students on the selection of statistical analysis methods, the majority of the feedback may concentrate on the task level, emphasizing correct and incorrect answers based on factual knowledge [

33]. For instance, instructors might guide students to choose ANOVA for comparing continuous variables across multiple categorical groups, citing its formula and applicability [

19]. This task-oriented instruction pertains to concrete and surface-level knowledge, demanding primarily task-level feedback. In contrast, teaching students about statistical principles and the interpretation of statistical results involves a more analytical approach. Here, students must connect underlying statistical principles with the context of their study to derive meaningful interpretations. For example, understanding the nature of an intervention is crucial for interpreting statistical significance between pre-treatment and post-treatment data [

19]. Such tasks necessitate process-level instruction and feedback due to the abstract nature of statistical principles and contextual variables involved. Consequently, skills related to understanding statistical concepts and interpreting statistical results may wield greater influence on students’ research competency, as they engage learners in deeper levels of understanding and cognitive processing [

33].

The inclusion of behavioral aspects such as submission rates and cheating behavior as predictors of students’ research competency aligns with previous literature in a sense that formative learning activities can be used to predict students’ learning performance [

10]. In fact, the negative relationship of cheating behavior and time taken to complete assignments to students’ research competency can be attributed to the concept of self-efficacy, which plays a crucial role in shaping students’ academic outcomes [

34,

35]. Individuals with low self-efficacy may exhibit reduced effort in their learning endeavors due to diminished motivation and a sense of lack of control over their academic success [

34,

36]. Consequently, they may perceive themselves as incapable of achieving high scores, leading to behaviors such as procrastination or resorting to academic dishonesty. Conversely, the positive association between students’ submission rates and post-lecture quiz performance reflects their intrinsic motivation and attention to learning [

36]. Students with high self-efficacy levels are more likely to be driven by internal motivations to excel academically, resulting in greater engagement and ultimately enhanced proficiency in statistics that contribute to their research competency [

36]. Although these behavioral variables serve as auxiliary factors within the scope of this study, they offer valuable insights into students’ learning behaviors and motivations in a broader educational context.

The implications of this study highlights the importance for instructors of statistics courses to prioritize lessons and tasks aimed at cultivating students’ foundational understanding of statistical principles and their skills in interpreting statistical results. In the context of research methods courses, instructors could incorporate review lectures focusing on these areas to reinforce students’ proficiency and readiness for applying statistical concepts to research formulation. This approach has the potential to bolster students’ research competency by equipping them with a robust statistical foundation. Moreover, this study can be viewed through the lens of learning analytics, as it leverages the capability of machine learning alongside students’ learning data encompassing both performance metrics and learning activities [

37]. Researchers and instructors can leverage these findings to develop predictive systems that inform teaching and feedback strategies. For instance, instructors could utilize such systems to monitor students’ progress in statistical skills across the three categories of statistical skills and intervene proactively when students show signs of falling behind, thereby ensuring that students maintain a solid grasp of statistics essential for effective learning in research methods courses. By integrating these strategies, instructors can foster a supportive learning environment conducive to enhancing students’ research competency and overall academic success.

This study has limitations to be aware of. Firstly, the small sample size, while common in undergraduate-level courses like statistics and research methods due to the nature of supervision-based learning, may limit the generalizability of the findings, particularly in the context of machine learning studies. Future research could address this limitation by collecting data longitudinally, allowing for a larger sample size that could enhance the robustness of predictive algorithms. Secondly, the constrained sample size also restricts the selection of predictive algorithms, precluding the use of more complex models such as neural networks or random forest ensembles in their most effective form. With a larger dataset, researchers could explore the application of these advanced algorithms, potentially yielding more reliable prediction outcomes suitable for developing predictive systems in educational settings. Lastly, future investigations could expand upon the variables considered, including factors like the implementation of problem-based learning approach. Such an approach could promote knowledge retention and the practical application of skills acquired in higher education, such as statistics and research, within real-world scenarios [

38]. By incorporating these additional variables, future studies can provide a more thorough understanding of the factors influencing students’ research competency to inform the design of more effective educational interventions.