1. Introduction

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is a rare entity typically occurring in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis (PD) and carries significant morbidity and mortality rates [

1,

2,

3]. The first description of EPS dates from 1907 when Dr. Owtschinnikow described as

peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata [

4]. Subsequently, in 1978 EPS was referred to as the abdominal “cocoon” and in 1980 EPS was found to be associated with PD [

5,

6]. However, EPS has also been described in other conditions such as abdominal or gynecological cancer, endometriosis, cirrhosis, organ transplantation, drug administration, infection, systemic rheumatologic and inflammatory diseases, mechanical and chemical intraabdominal irritants or as primary EPS with unclear etiology [

7].

For patients administered PD, the major risk factor is the time spent receiving treatment. The disease is rarely encountered in the first 3 years of dialysis and after 5 years, the incidence of EPS remains low but increases continuously. Notably, in two-thirds of patients, symptoms of EPS appear months or even years after the transfer to hemodialysis or kidney transplant. This feature along with different transplant or hemodialysis access policies explains the variable incidence of EPS reported by registries [

1,

8,

9,

10].

Clinical manifestations of EPS consist of signs and symptoms of intestinal dysfunction (such as abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, malnutrition and total bowel obstruction in the late stages) sometimes associated with ultrafiltration failure, bloody effluent or recurrent sterile peritonitis. These symptoms are chronic, insidious and non-specific, but are essential for diagnosis as they raise the suspicion in predisposed patients [

11].

A positive diagnosis of EPS is established based on the aforementioned clinical signs in conjunction with CT scan images that show loculated ascites, calcifications and thickening of the parietal and visceral peritoneum [

12]. Direct visualization of the abdomen and histology can also be used to establish a diagnosis but are rarely needed. Several types of lesions have been described: the peritoneal surface is reduced to a thickened and rough membrane, compared by some authors to the sole of a worn shoe [

13], and the thickening of the peritoneum can be cellular (through the activation of fibroblasts) or acellular (likely through interstitial collagen deposits) [

14]. Thickening of the peritoneal membrane determines the rigidity and thickening of the intestinal serosa and subsequently the decrease of intestinal motility until it has disappeared, culminating with intestinal occlusion. The mesentery, stomach, liver and spleen are also affected by sclerosis, which also characteristically does not affect the entire abdomen to the same degree, and only the most affected areas cause the appearance of the abdominal “cocoon” [

13,

15].

Tamoxifen and/or steroids administered in the early stages and extensive surgical adhesiolysis in the late stages significantly ameliorate the morbidity and mortality of EPS [

16].

Purpose: Although intestinal obstruction is the common manifestation that results in a referral of patients with EPS to a surgeon, there have been cases that required emergency surgery for reasons other than EPS. In the present study, we sought to determine whether there is a correlation between the morpho-pathological results of these patients who underwent emergency surgery and the common EPS morpho-pathological changes.

2. Materials and Methods

A group of 63 patients who underwent PD and were admitted to the General Surgery Department of “Dr Carol Davila” Teaching Hospital of Nephrology (Bucharest, Romania) for catheter replacement, catheter removal or surgical co-morbidities from November 2011 to March 2021 were analyzed.

The demographic and clinical parameters of the included patients were retrospectively extracted from the medical electronic records. In all EPS cases, samples were collected from the peritoneum for pathological examination. All samples were analyzed by the same pathologist.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Analyse-it™ Standard Edition (Analyse-it Software, Ltd., Leeds, UK) package. Categorical variables are presented as percentages, comparisons of which were performed using Pearson’s χ2 test. A p≤0,05 was considered statistically significant.

Continuous variables are presented as median and quartiles [1; 3], comparisons of which were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

3. Results

All 63 patients (44% women; median age, 62 [48,0; 70,8] years) were treated with continuous ambulatory PD. Catheter removal for scheduled transfer to hemodialysis and for refractory PD-associated infections were the two highest causes for surgical intervention (52,4 and 27,0%, respectively). An additional 11% of interventions were for catheter reposition, 4,7% for co-morbidities, 3,2% for EPS and 1,6% for catheter removal following a successful kidney transplant. The same team performed all surgeries. Of the 63 patients, 5 (7,9%) had a final diagnosis of EPS.

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics and morpho-pathological changes of these 5 patients with EPS.

Following univariable analysis, it was demonstrated that patients with EPS were younger (median age, 39 [30; 52] vs 63 [50,8; 71,2] years; p=0,0019) and had received PD for longer (114 [86; 132] vs 18 [11; 46,5] months; p=0,0013) compared with patients without EPS. Of the 5 patients with EPS, 2 required emergency surgery for gynecological conditions, further details of which are described below.

The first patient was a 25-year-old woman with lupus nephritis who had undergone PD for 10 years. The PD history of the patient was associated with three episodes of peritonitis (including

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Enterococcus faecalis and

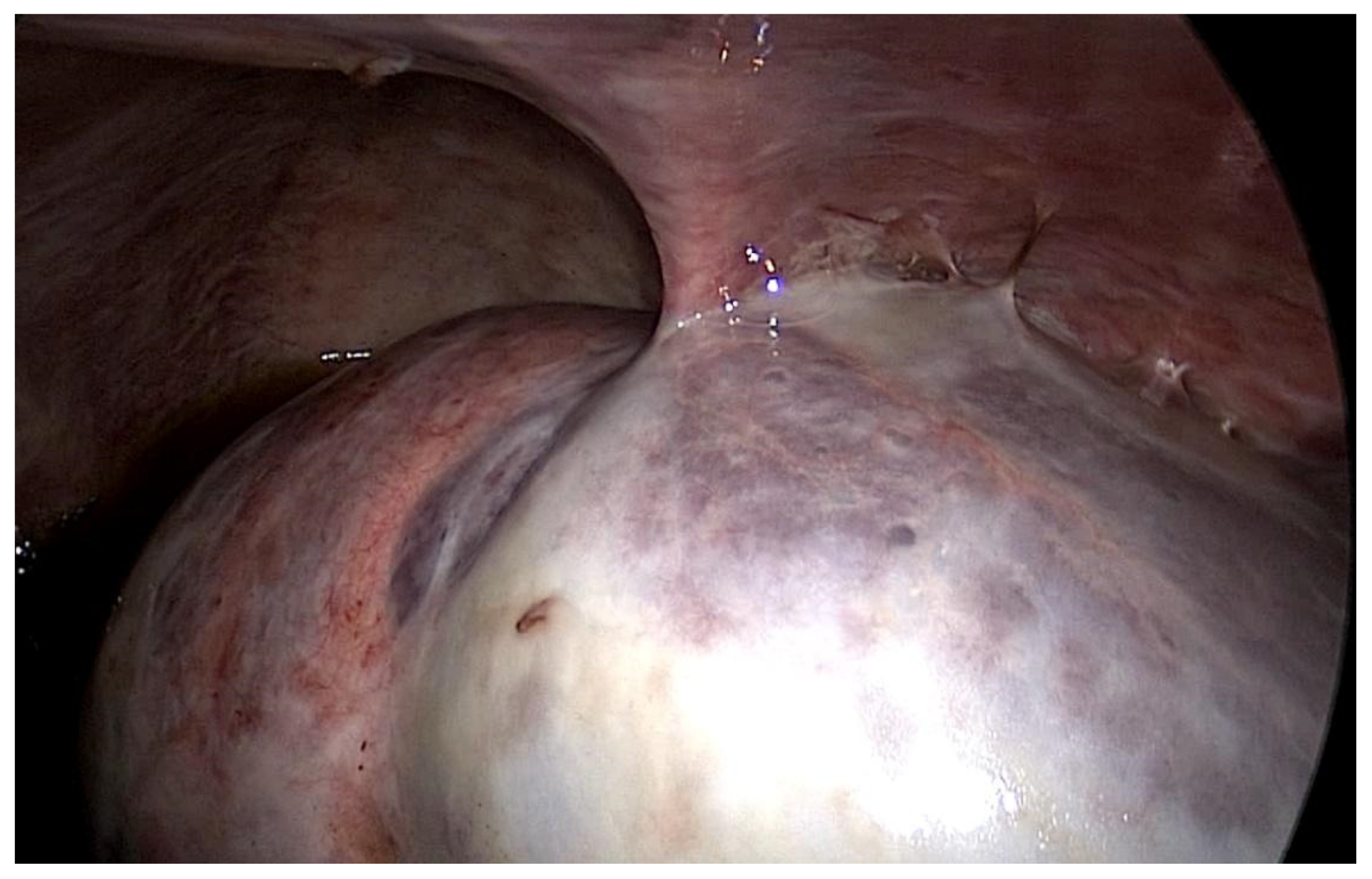

Staphylococcus aureus infections, the last of which was 6 years before presentation) and negative ultrafiltration for several months requiring four hypertonic exchanges daily (2X 1,36% and 2X 3,86% Dianeal PD Solution (Baxter International)) for controlling overhydration. For several months, the patient was suffering from metrorrhagia and bloody effluent for several days. During hospitalization, the effluent became notably hemorrhagic with acute anemia. Emergency surgery was performed revealing hemoperitoneum due to an adnexal pathology. Intraoperatively, we found extensive peritoneal fibrosis encapsulating the small bowel loops and the organs located in the pelvis in a “cocoon” (

Image 1). Furthermore, there was significant bleeding from the site where the right adnexa should have been located and the right fallopian tube and right ovary could not be identified. A visceral “block” representing the right adnexa was dissected and isolated with great difficulty, which was resected to stop the source of the intraperitoneal hemorrhage. A final diagnosis of EPS was confirmed by the pathologist. The immediate and late postoperative outcomes were good, without any surgical complications; however, the patient subsequently died 6 months later due to a hemorrhagic stroke.

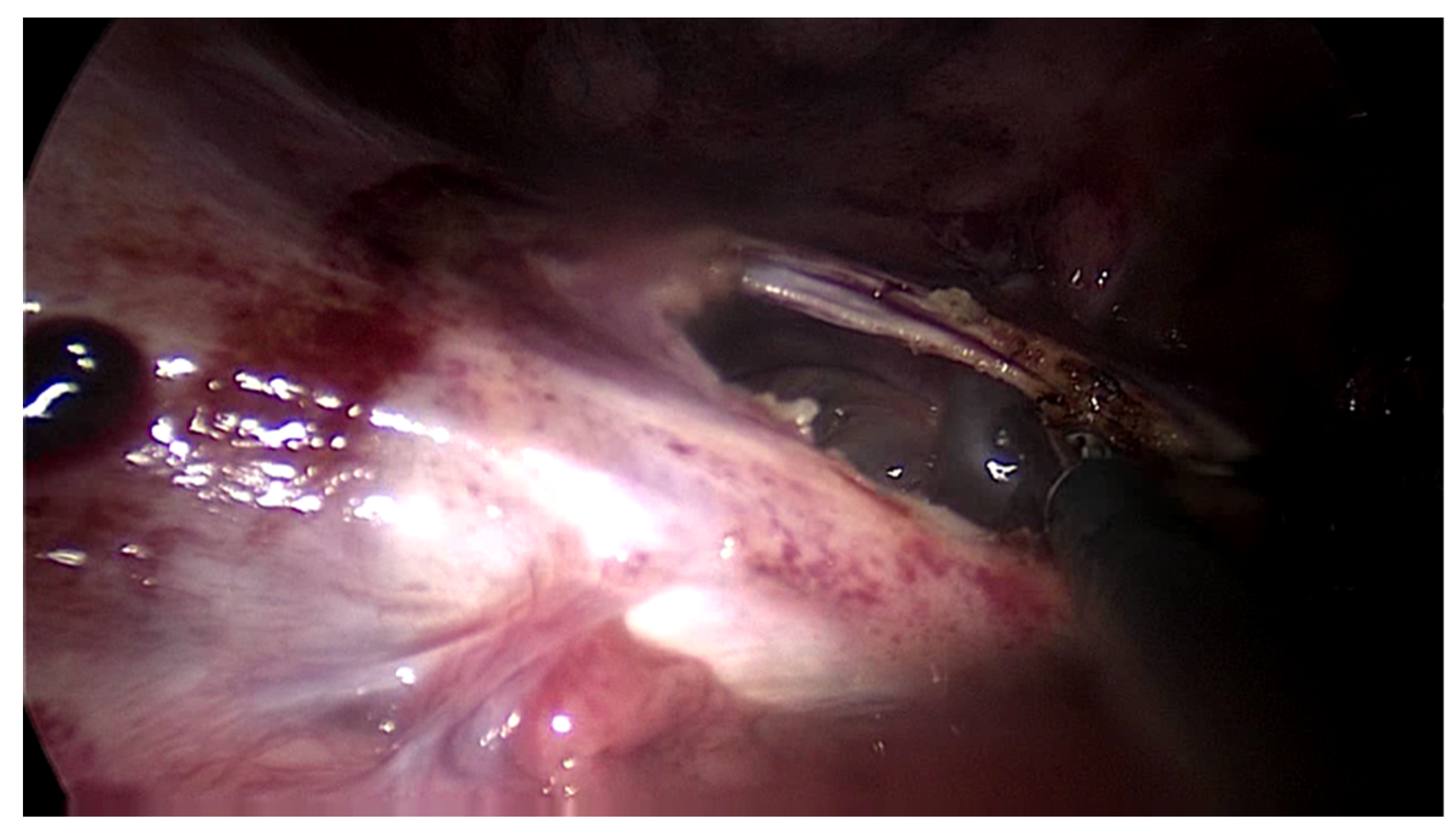

The second patient was a 44-year-old woman who had undergone PD for 11 years. The patient was referred for nausea, vomiting and metrorrhagia accompanied by a palpable mass in the lower abdomen. A CT scan revealed the presence of an abdominopelvic tumor measuring 12-cm in diameter, suggestive of a uterine fibroid causing compression of the rectum. A hemostatic curettage was performed in an attempt to postpone surgery, which proved unsuccessful. Then, laparotomy and a definitive transfer to hemodialysis treatment was decided. The intraoperative macroscopic appearance of the parietal and visceral peritoneum revealed only some areas of peritoneal fibrosis, except for the pelvic peritoneum which showed extensive fibrosis (

Image 2). The fibromatous uterus was encapsulated in a pelvic “cocoon” and the rectosigmoid junction adhered to this “pelvic block”.

The procedure then consisted of a total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy. The adhesiolysis of the rectosigmoid junction from the pelvic block was performed with great difficulty, with the surgical procedure lasting 4.5 h. The patient had a slow postoperative recovery as it was marked by a difficult resumption of the gastrointestinal transit.

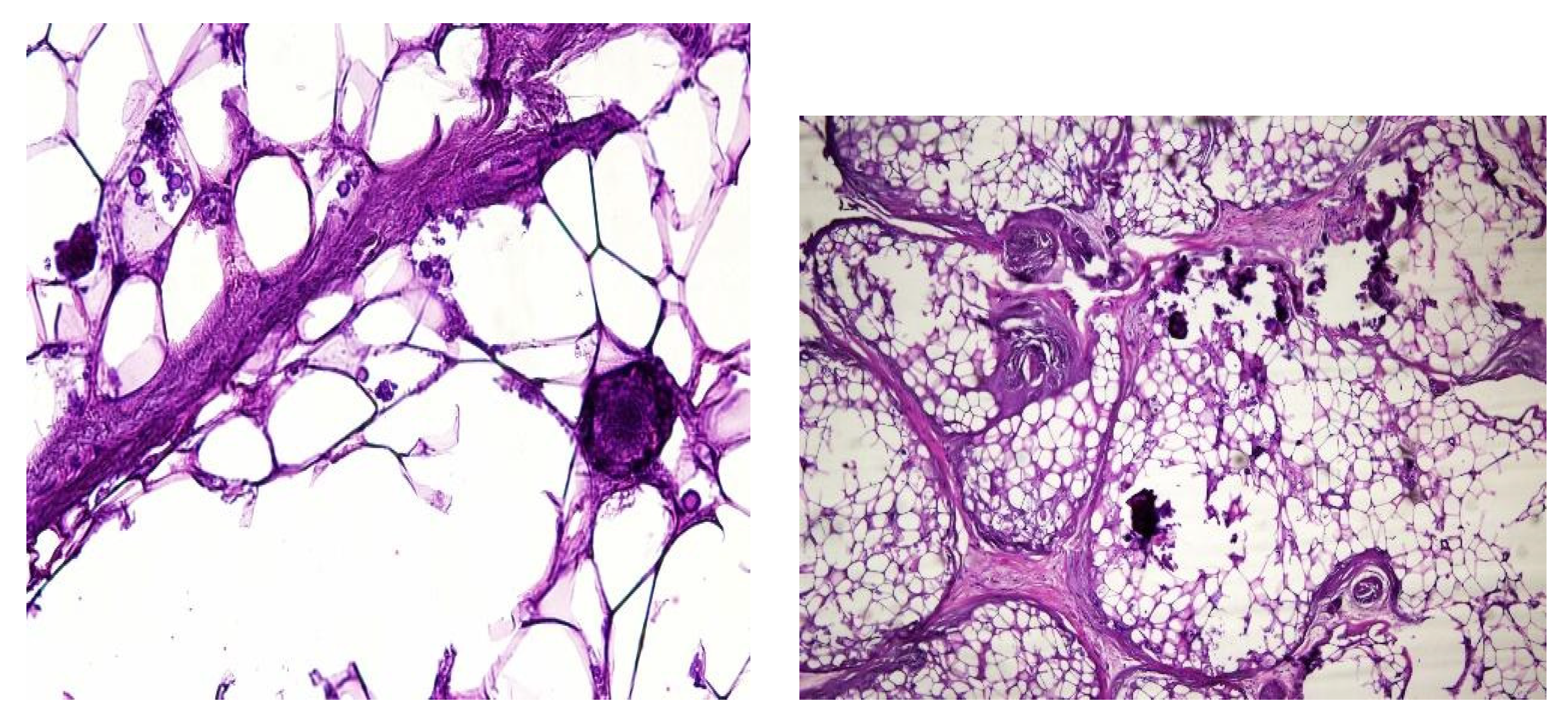

In both of the described cases, optical microscopy revealed lamellar fibrosis, deposits of fibrin on the surface of the peritoneum (

Images 3 and 4) and dystrophic calcifications in the peritoneum (

Images 5 and 6).

All 5 patients with EPS underwent extensive adhesiolysis, 2 of which (patients 1 and 5) also received prednisone (0,5 mg/Kc daily for 1 month, which was then progressively decreased). The immediate postoperative period (7 days after surgery) was without complications and the patients were discharged.

4. Discussion

Herein, we present data from a single tertiary surgery center that has dedicated teams for patients receiving dialysis. Extensive adhesiolysis for EPS was performed in almost 8% of the surgical patients receiving PD. In agreement with the literature, these patients were young and had a long duration of treatment [

17]. All patients had suggestive symptoms for several months, which were not recognized by their physicians. In Romania, the prevalence of PD is very low (1,7%, 10-15 patients/dialysis unit). Therefore, a physicians’ lack of experience is one of the major factors that negatively influences the prognosis of patients receiving PD and most likely explains the lack of recognition of early EPS symptoms in more than half of the presented patients in this study (overhydration in patients 1 and 4, nausea and vomiting in patient 2) [

18].

The aim of the present study was to emphasize the possibility of other surgical pathologies overlapping with EPS, increasing the complexity of the surgical intervention. To the best of our knowledge, the association between EPS and benign gynecological pathology in patients receiving PD has not yet been described. When searching the literature, we found only one case report of a 66-year-old non-nephrological woman who was hospitalized for diarrhea and abdominal distension. Extensive work-up revealed ascites, bulky ovaries, a fibroid uterus and multiple peritoneal and mesenteric deposits. During laparotomy, the bowel was firm and solid with no obvious peristalsis due to serosal fibrosis and histology showed a fibrous process with spindle cells and inflammation. After hysterectomy, the patient remined symptom-free and a normal CT image was observed after 6 months of follow-up [

19]. The morpho-pathological changes were similar to those observed in the two female patients with gynecological pathology (“iced” abdomen due to extensive fibrosis and histology with low grade inflammation) described in the present study; however, these two patients had more severe disease with bone metaplasia and a pelvic “block” encapsulating all internal genitalia. Moreover, this last feature was the single morpho-pathological feature that differentiated these patients from the other 3 patients, receiving PD raising the question of a contribution of pelvic pathology with EPS severity in association with long PD treatment.

Several studies have attempted to identify and/or standardize the morpho-pathological changes in EPS differentiating it from PS, which is a common occurrence in patients receiving PD and presents as a simple sclerosis [

15,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The most frequent aspects observed were fibrin deposits, fibroblast swelling and mononuclear cell infiltration [

14,

15,

21]. Garosi et al investigated 39 biopsies from patients with EPS and found that tissue and arterial calcification, thickening of the submesothelial layer and vasculopathy were the most significant observed changes [

12]. In another study, Sherif et al found that only fibrin deposits and thickening of the compacta were significant [

24]. In the present study, lamellar fibrosis, decreased cellularity, low grade perivascular inflammation and dystrophic peritoneal calcifications were frequent histological changes. Similarly, Braun et al attempted to standardize the lesions and to define reproducible histological parameters in patients with EPS. It was found that calcification was a highly indicative criteria for EPS. Furthermore, mesothelial denudation, chronic inflammation, fibrin deposits, decreased cellularity and the presence of fibroblast-like cells were also indicative of EPS [

13].

According to the “two hit” hypothesis of EPS pathogeny, peritonitis episodes, transfer to hemodialysis, kidney transplant and acute intra-abdominal pathology are triggers (second hit) for peritoneal inflammation that already has an inflammatory state (first hit) due to chronic exposure to PD solution [

25]. Supporting this theory, Wong et al found that 1 in every 5 patients receiving long-term PD with catheter removal for refractory peritonitis (19,5%; median duration of therapy, 71,6 ± 43,3 months) evolved to EPS in a 6 month period of observation. This was explained by the presence of two important “second hit” factors (bacterial peritonitis and withdrawal of dialysis) [

26]. In the present study, all patients had possible “second hit” type events before EPS symptoms presented (peritonitis, hemodialysis transfer, hemorrhagic ovary cyst and uterine fibroid), but due to the small number of patients an analysis of possible associations was not possible.

The surgical treatment of EPS has extensively changed over the years and improved survival [

1,

27,

28]. Treatment mainly consists of adhesiolysis and removal of the encapsulated membrane, hence clearing the bowel loops. However, the treatment is still not standardized and data from the literature shows a post-surgery survival rate of 61-100% [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The main cause of death is uncontrolled peritonitis during postoperative care. In addition, bowel resection is associated with an increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality, and therefore, in specialized centers, this procedure is avoided as much as possible [

3,

15,

20]. Almost one-quarter of patients have recurrent disease in the first 2 years following surgery [

29]. Unfortunately, follow-up data was only available for 2 patients in the present study. These patients received steroids with no relapse during the 6 months of follow-up. We consider that medical treatment after surgery could further ameliorate prognosis by lowering the chances of relapse, but this requires further research.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in the present study we aimed to describe a very rare condition, EPS, that affects patients undergoing PD and that leads to intestinal obstruction. We presented two cases of patients whose clinical manifestations of EPS were underrecognized. Intraoperative exploration for other acute pathologies and histological findings established the definitive diagnosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.I. and C.R.I.; methodology, I.A.; software, I.A.; validation, C.I., S.H.S. and V.S.; formal analysis, I.A.; investigation, T.C.; resources, T.C. and I.A..; data curation, V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.I.; writing—review and editing, C.I.; visualization, T.C..; supervision, S.H.S..; project administration, C.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kawanishi H, Kawaguchi Y, Fukui H, et al: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan: A prospective, controlled, multicenter study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:729–737.

- Kawanishi H,Mujais S,Topley N,Oreopoulos GD: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis:definition,etiology,diagnosis,and treatment. Peritoneal Dialysis International 2000,Vol 20,Suppl 4, S43-S55.

- Johnson DW, Cho Y, Livingston BER, Hawley CM, McDonald SP, Brown FG, Rosman JB, Bannister KM, Wiggins KJ: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: Incidence, predictors, and outcomes. Kidney Int. 2010;77:904–912. [CrossRef]

- Owtschinnikow PJ: Peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata. Arch Klin Chir. 1907;83:623–634.

- Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A: Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: The abdominal cocoon.British Journal of Surgery, vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 427–430, 1978. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi et al: Sclerotic thickening of the peritoneal membrane in Maintenance peritoneal dialysis patients. Arch Int Med 1980; 140:1201-1203. [CrossRef]

- Danford CJ, Lin SC, Smith MP, Wolf JL: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. World J Gastroenterol 24(28): 3101-3111, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Brown EA, Van Biesen W, Finkelstein FO, et al: Length of time on peritoneal dialysis and encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: Position paper for ISPD. Perit Dial Int. 2009;29:595–600.

- Johnson DW, Cho Y, Livingston BE, et al: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: Incidence, predictors, and outcomes. Kidney Int. 2010;77:904–912. [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S: Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25(Suppl 4):S39–S47.

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, Nakayama M, Miyazaki M, Nakamoto H, Tranaeus A: Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: Diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures.Perit Dial Int. 2005 Apr;25 Suppl 4:S83-95.

- Garosi G, Di Paolo N:Peritoneal Sclerosis:One or Two Nosological Entities? Seminars in Dialysis 2000, Vol 13, nr 5, 297-308. [CrossRef]

- Braun N, Fritz P, Ulmer C, Latus J, Kimmel M, Biegger D, Ott G, Reinold F, Thon KP, Dippon J, Segerer S, Alscher MD: Histological Criteria for EPS-A Standardised Approach. PLoS ONE 2012, Vol 7,Issue 11, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Morelle J, Sow A, Hautem N, Bouzin C, Crott R, Devuyst O, Goffin E:Interstitial Fibrosis Restricts Osmotic Water Transport in Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015;26:2521–2533. [CrossRef]

- Hsu HJ, Yang SY, Wu IW, Hsu KH, Sun CY, Chen CY, Lee CC: Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis in Long-Termed Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. BioMed Res. Int. 2018;2018:8250589. [CrossRef]

- del Peso G, Bajo MA, Gil F, Aguilera A, Ros S, Costero O, Castro MJ, Selgas R: Clinical experience with tamoxifen in peritoneal fibrosing syndromes. Adv Perit Dial 19: 32-5, 2003.

- Korte MR, Sampimon DE, Betjes MG, Krediet RT: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: The state of affairs. Nat Rev Nephrol 7(9): 528-38, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary K: Peritoneal Dialysis Drop-out: Causes and Prevention Strategies. Int J Nephrol. 2011: 434608, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Critchley M, Bagley J, Iqbal P: Degenerative fibroid and sclerosing peritonitis. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012: 218126, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Vizzardi V, Sandrini M, Zecchini S, Ravera S, Manili L, Cancarini G:Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in an Italian center: Thirty year experience. J. Nephrol. 2016;29:259–267. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer B, Bartosova M, Macher-Goeppinger S, Sallay P, Vörös P, Ranchin B, Vondrak K, Ariceta G, Zaloszyc A, Bayazit AK, et al: Neutral pH and low–glucose degradation product dialysis fluids induce major early alterations of the peritoneal membrane in children on peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2018;94:419–429. [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó M, Ramírez-Huesca M, Domínguez-Jiménez C, Sánchez-Madrid F, Lara-Pezzi E, Gamallo C, López-Cabrera M, Selgas R, Aguilera A, Sánchez-Tomero JA, et al: Peritoneal dialysis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:403–413. [CrossRef]

- Alscher DM, Braun N, Biegger D, Fritz P: Peritoneal Mast Cells in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients, Particularly in Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis Patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2007;49:452–461. [CrossRef]

- Sherif AM, Yoshida H, Maruyama Y, Yamamoto H, Yokoyama K, et al: Comparison between the pathology of encapsulating sclerosis and simple sclerosis of the peritoneal membrane in chronic peritoneal dialysis. Ther Apher Dial, 2008; 12:33-41. [CrossRef]

- Augustine T, Brown PW, Davies SD, Summers AM, Wilkie ME: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: Clinical significance and implications. Nephron Clin Pract 111(2): c149-54, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Wong YY, Wong PN, Mak SK, Chan SF, Cheuk YY, Ho LY, Lo KY, Lo MW, Lo KC, Tong GM, Wong AK: Persistent sterile peritoneal inflammation after catheter removal for refractory bacterial peritonitis predicts full-blown encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int. 33(5): 507-14, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ryu JH, Lee Kl, Koo TY, Kim DK, Oh KH, Yang J, Park KJ. Outcomes of the surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: A case series from a single center in Korea. Kidney Res Clin Pract 38(4): 499-508, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sharma V, Moinuddin Z, Summers A, Shenoy M, Plant N, Vranic S, Prytula A, Zvizdic Z, Karava V, Printza N, Vlot J, van Dellen D, Augustine T: Surgical management of Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis (EPS) in children: International case series and literature review. Pediatr Nephrol 37(3): 643-650, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S: Experience of 100 surgical cases of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: Investigation of recurrent cases after surgery. Adv Perit Dial 22: 60-4, 2006.

- Phelan PJ, Walshe JJ, Al-Aradi A, Garvey JP, Finnegan K, O’kelly P, Mcwilliams J, Ti JP, Morrin MM, Morgan N, et al: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: Experience of a tertiary referral center Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Ren. Fail. 2010;32:459–463. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).