1. Introduction

The first concept of peritoneal dialysis was presented in London in 1743 by Christopher Warrick at the Royal Society of Medicine.

Experiments we done initially on animals. In 1985, Orlow performed the first attempts at peritoneal dialysis on dogs, then in 1923 Putnam published similar experiments on cats, confirming the attempts made by Orlow.

In 1946, Seligman and Fine published the first peritoneal dialysis treatment in humans for a patient with acute renal failure. [

1]

Later, peritoneal dialysis was also introduced for patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD).

In the 60s and 70s, Tenckhoff developed the peritoneal dialysis catheter and the methods of inserting it in the peritoneal cavity.

Later there were continuous pursuits for the improvement of peritoneal dialysis catheters and their insertion techniques.

In Romania, the first insertion of a PD catheter for patients with ESRD was carried out in the 1995.

Catheters in use at the moment are single or double cuff silicone catheters, with straight or coiled tip [

2]

The current unanimously accepted placing techniques for PD catheters are: percutaneous insertion, peritoneoscopic insertion, open surgical or laparoscopic insertion.

The placing of the PD catheter is performed by nephrologists, interventional radiologists or general surgeons. [

3]

The long-term success of PD begins with the correct choice of catheter type and the correctness of its placement.

Over the years there have been numerous attempts at improving PD placement methods with the purpose to decrease as much as possible the number of early complications of peritoneal dialysis and to increase the compliance and well-being of patients with this dialysis type and to avoid PD failure. [

4]

The main early complications that occur after the insertion of the PD catheter are: perforation of the abdominal viscera, migration of the catheter, catheter obstruction, pericatheter leaking and infectious complications (at the external orifice or peritonitis). These are especially related to the way in which the insertion is carried out (regardless of the chosen method), the experience of the medical team involved and less of the type of the catheter used. [

5,

6]

In the USA, most PD catheters are inserted by surgeons (80%), and in their residency training program there is a special internship for learning proper placing techniques. [

5]

In Romania, catheters for PD are installed exclusively by surgeons and there is no training opportunity in residency for learning placing techniques. (

www.rezidentiat.ms.ro).

The first technique used in Romania was the insertion by open laparotomy. Later, due to the increase number of patients who wanted PD, it was switched to laparoscopic placing.

An important obstacle for delaying the use of the laparoscopic technique was lack of confidence and the limited possibilities of general anesthesia.

In this article, we want to present our 10-year experience in laparoscopic placing of PD catheters, the results obtained, the early complications encountered 3 months post-procedure and the way of solving them.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective study on 133 patients hospitalized for PD catheter insertion in“Dr Carol Davila” Teaching Hospital of Nephrology (Bucharest, Romania), a tertiary surgery center dedicated to the treatment of patients with ESRD during the period 2011-2022.

All patients with an indication for PD catheter placement were included, regardless of the technique used, laparoscopic or open, including patients in whom the catheter was reinserted.

All patients were referred to the surgery clinic by the nephrologist after opting for this method of dialysis treatment.

There were no catheters placed for patients with acute renal failure, a diagnosis that would have been an exclusion criterion for our study.

The protocol for patients opting for PD included a surgical clinical evaluation for detection of ventral or inguinal hernia, in which case these were surgically corrected prior to inserting the PD catheter.

The entire group of patients was monitored for 3 months for possible early complications post-placement of PD catheters.

Pre-procedure preparation included a dose of sodium picosulfate for preparation and emptying of the digestive tract.

Before the intervention, an indwelling urethral catheter is placed, which will be removed at the end of the procedure along with prophylactic antibiotic therapy single dose.

The laparoscopic placement of the PD catheter is performed by a single surgical team composed of 2 surgeons.

We practice a minimal open incision above the umbilicus (Hasson technique) for the insertion of the optical trocar. After the introduction of the laparoscopic camera we meticulously inspect the peritoneal cavity for possible intraperitoneal adhesions, parietal defects or other intraperitoneal pathologies.

Afterwards, a working trocar is placed in the right flank. If adhesions were detected during the inspection of the peritoneal cavity adhesiolysis is performed. At the first insertion, the catheter is placed in the left flank.

The trocar for the insertion of the catheter is placed into the left flank by tunneling the right abdominal muscle in an oblique direction towards the bottom of the Douglas sac.

After the correct positioning of the catheter at the bottom of the Douglas sac, it is tightened with polypropylene thread 000 at the point of externalization in the peritoneum with a fascial closure needle. The functionality of the catheter is checked by instillation and aspiration of 0.9% saline solution.

We do not practice suturing the omentum to the anterior abdominal wall.

The exterior lumen of the catheter is placed at 2 cm from superficial cuff through a minimum incision corresponding to the diameter of the catheter.

The suture of the supraumbilical wound aponeurosis is realized with polypropylene thread no. 1.

All skin incisions are sutured with thread polypropylene 000, including the minimum incision for the insertion of the fascial closure needle.

For patients who require laparoscopic catheter reinsertion after its extraction, we use a technical artifice: the opening that remains after the deep cuff dissection during extraction will be used for placing the optic trocar. We use this tactic to decrease the number of incisions and of course possible postoperative parietal complications. Otherwise, the laparoscopic procedure continues as we have described above.

On the 1st postoperative day, we monitor radiographically the correct positioning of the catheter with the tip in the pelvis on the medial line and the absence of folds.

The lavage of the peritoneal cavity is initiated. This is done once/day, on average for 3 days (until clear), then 2 times/week. The frequency is increased to 3 times/week if the inflow or outflow of the solution is difficult due to fibrin deposits obstruction.

The incision wounds and exterior opening around the catheter are protected with non-occlusive dressings.

Monitoring for complications is performed every 2-3 days or as needed.

Disinfection is carried out with betadine followed by washing with 0.9% saline solution and application of mupirocin cream.

Patient training begins in the second week, during the procedures described above and is concluded once the patient understands the techniques and can recognize complications.

The parameters of interest were retrieved from the electronic files of the patients, from the register of surgical interventions and from the PD treatment monitoring files.

The statistical analysis of the batch was performed using the Analyse-it™ Standard Edition (Analyse-it 4.80 Software, Ltd., Leeds, UK) package. Categorical variables are presented as percentages, comparisons of which were performed using Pearson’s χ2 test. A p≤0,05 was considered statistically significant.

Continuous variables are presented as median and quartiles [

1,

3]. Microsoft Excel 2013 was used for graphics and tables.

3. Results

From the group of 133 patients hospitalized for catheter implantation for PD, 126 were performed laparoscopically and 7 were inserted via the open technique.

Of the 7 patients with insertion by open technique (laparotomy), 6 patients were having multiple comorbidities which presented a contraindication to general anesthesia and they were on long life catheter hemodialysis. These patients were referred to our clinic for the change/removal of the long-life catheter that no longer provided sufficient flow for hemodialysis. All the above patients presented with stenosis of the femoral vascular axis / cava vein and/or the superior vascular axis being at the 4th (5 patients) and the 5th change (2 patients) of the long-life catheter.

The placement of catheter for PD (6 patients) was in expectancy of the moment when the change of the long-life catheter could no longer be carried out.

For 1 more elderly patient with the most advanced age (88 years old), the insertion was also carried out by open technique as the patient presented with contraindication for general anesthesia and followed the procedure of initiating peritoneal dialysis.

The open PD catheter insertion was performed under local and augmented IV (intravenous) anesthesia.

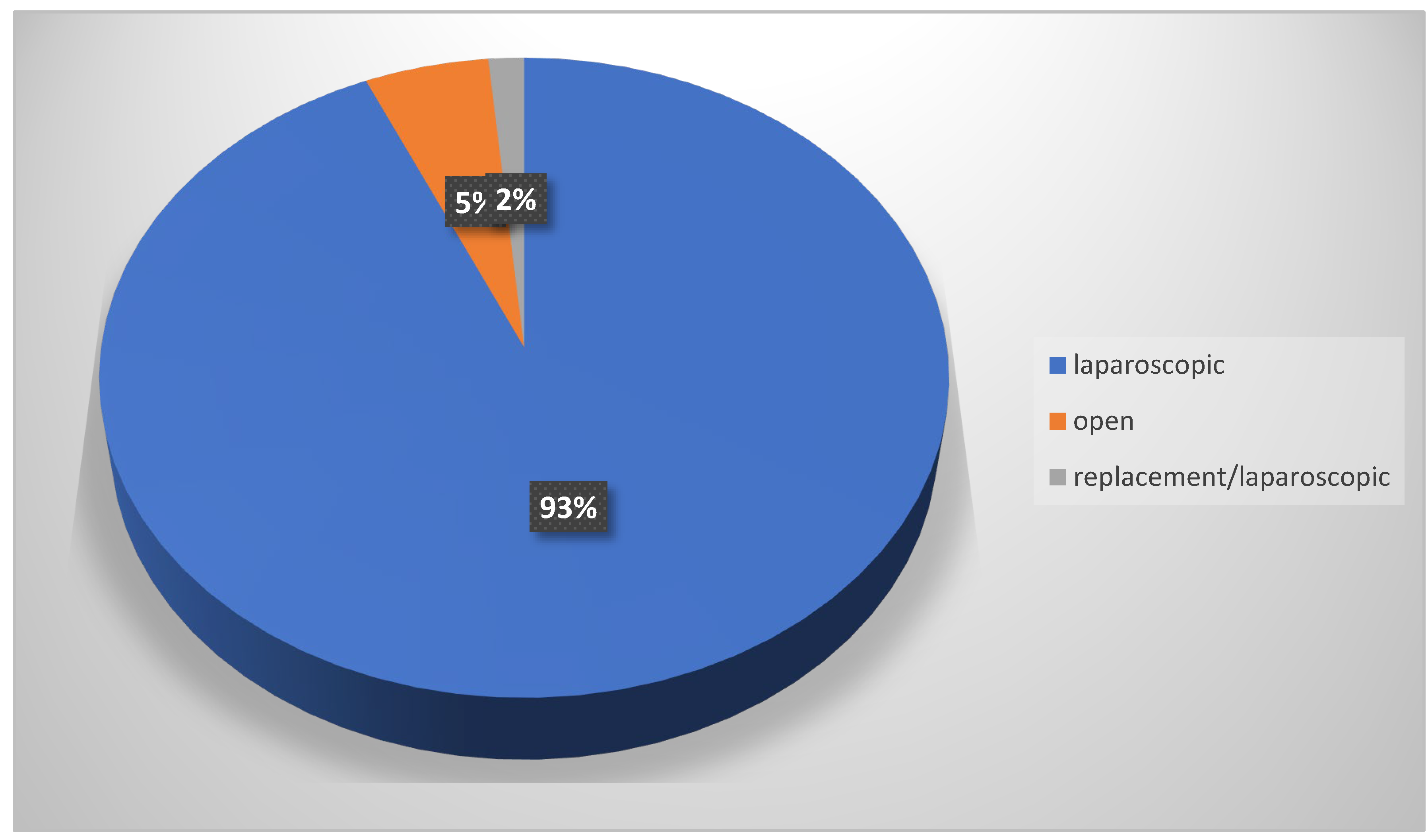

Out of the total number of laparoscopic catheter insertions for PD, 2 were reinsertions, 1 patient presented with a pericatheter hernia and a patient who presented pericatheter leaks. The reinsertion was also carried out by laparoscopic procedure. (

Figure 1)

The gender distribution of the batch is: 44% women/56% men; median age 62 (25; 88) years and according to their background of origin 87%patients were from the urban environment and 23% from the rural environment.

The 7 patiens with open technique insertion where not followed up by our dialysis center.

Laparoscopic adhesiolysis was performed in 17% of patients due to viscero-parietal intraperitoneal adhesions.

Out of these patients 54% had a history of previous surgical interventions (appendectomy, cholecystectomy, cesarean section, tubal abscess).

Based on the clinical examination protocol for hernia and ventral parietal defects, 9 patients were identified to have hernias, 6 presented with inguinal hernia and 3 with umbilical hernia.

These 9 patients underwent open surgery using the Lichtenstein alloplastic technique /omphalectomy and reinforcement mesh insertion, with a minimum of 3 months prior to the placement of the PD catheter.

During the laparoscopic exploration of the peritoneal cavity, no hernias or parietal defects were highlighted that required surgical repair.

The duration of the laparoscopic procedure was on average 32 minutes with an extreme of 20 – 55 minutes.

For the open insertions, the average duration of the procedure was 18 minutes with extremes of 16 - 35 minutes.

During the follow-up period, 14% of patients (18/128) experienced a total of 23 complications of their dialysis treatment: 61% in the first month, 34.7% in the second month, 4.3% in the 3rd month. (

Figure 2)

The most common complication was infection (peritonitis 35%, catheter exit site infection 30.4%).

Eight patients (6.5%) had one episode of peritonitis. It was a single pre-training patient peritonitis episode (12.5% of all peritonitis), 37.5% were diagnosed during the patient training period and 50% were post-training period (in the first month of home treatment) (

Figure 1).

One peritonitis episode was preceded by PD catheter exit site infection and another episode was refractory and the patient was ultimately changed to hemodialysis as he refused to return to PD after healing of the peritonitis episode.

Seven patients (5.5%) were diagnosed with PD catheter exit site infection, none of them in the pre-training period.

Almost half of them (43%) were diagnosed during the training and the other half were post-training episodes (57%) (

Figure 2).

The second most frequent complication was peri-catheter leakage (4% of all patients, 21.7% of total complications). The majority (4/5) presented immediately postoperatively, during lavage.

In one case the peri-catheter leakage started with the initiation of treatment, week 3.

Except one patient who required catheter discontinuation and contralateral insertion, all the episodes were relieved by total, temporary (7-14 days) rest of the peritoneal cavity.

There was an insignificant increase of infection frequency in the leak group (60% vs 23%, p=0.07).

Catheter migration, hernia and significant bleeding were rare events (0,8 % each) (

Figure 2);

To conclude, during the 3 months follow-up of the patient batch, the following complications were identified including the time frame they appeared since the onset of PD and the ways to solve the complications that occurred:

-5 patients with peri-catheter leakage (at day 1, week 1, week 2 after the start of PD); 1 patient requiring re-implantation of the catheter

-1 patient with catheter migration (at 1 month from the start of PD),

-1 patient with bleeding during the procedure

- 1 patient who developed peri-catheter hernia at month 2 – was one of the patients who presented pericatheter leakage at week 2

- 7 patients with infection at the skin opening for the catheter (at 1 month - 3 patients, at 2 months – 4patients); 1 patient required re-implantation of the catheter (month 2)

-8 patients with peritonitis (at 2 weeks – 1 patient, at 1 month – 1 patient, at 2 months -5 patients, at 3 months – 1patient, from the start of PD). The patient who developed peritonitis in month 2 was switched to HD;

One patient was definitively switched from PD toHD.

4. Discussion

Although the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) guidelines describe in detail each insertion method of the PD catheter, there is a continuous pursuit for improving the techniques as the goal is to decrease the number of early complications and subsequently the number of patients with PD failure [

6,

7,

8,

9].

From our experience, the learning curve for laparoscopic PD catheter mounting is a short one,being required to assist in 3 insertions and perform 5 insertions as the first operator.

As such, we do not consider it necessary to introduce a separate internship in residency for this procedure.

The subsequent training of a surgeon specialist with good laparoscopic skills in centers that want to insert the PD catheter being considered sufficient [

10,

11,

12,

13].

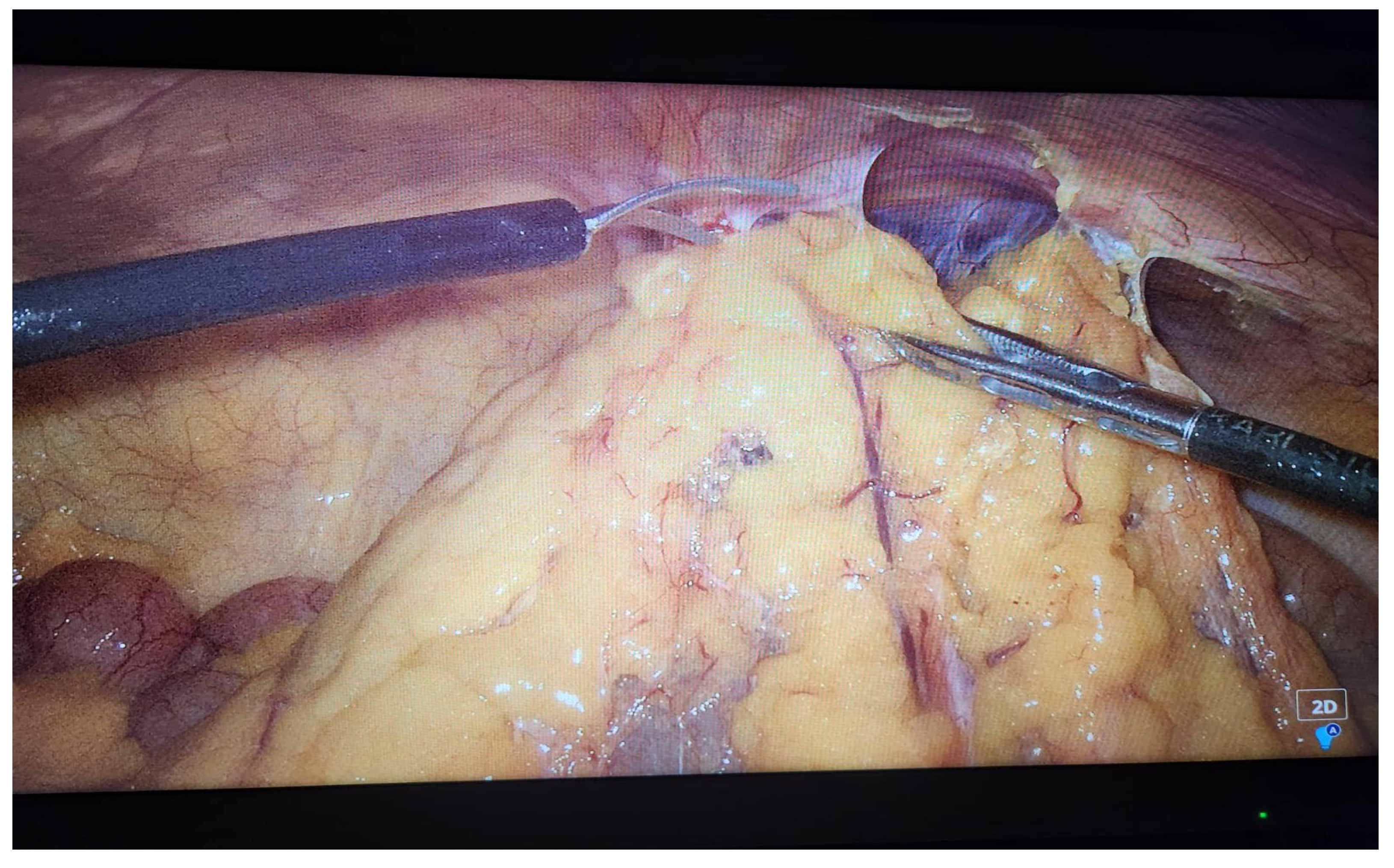

The first big advantage of the laparoscopy technique compared to any other inserting techniques is the correct placement of the catheter at the bottom of the Douglas sac, after tunneling the right abdominal muscle as well as the detailed view of the peritoneal cavity, thus identifying viscero-parietal adhesions or other lesions that could be easily resolved in the same operative act (ex. ventral hernias, genital pathology) [

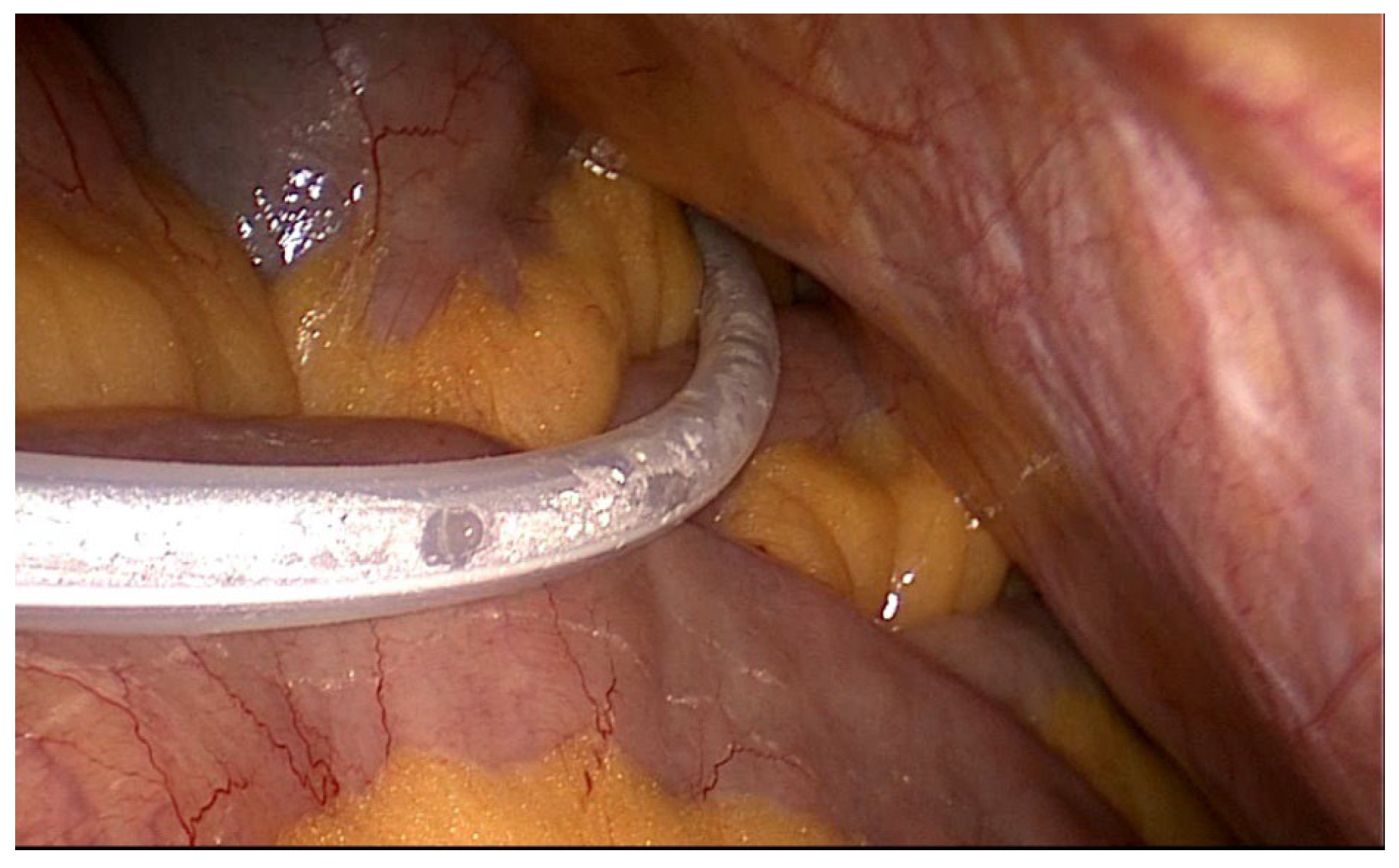

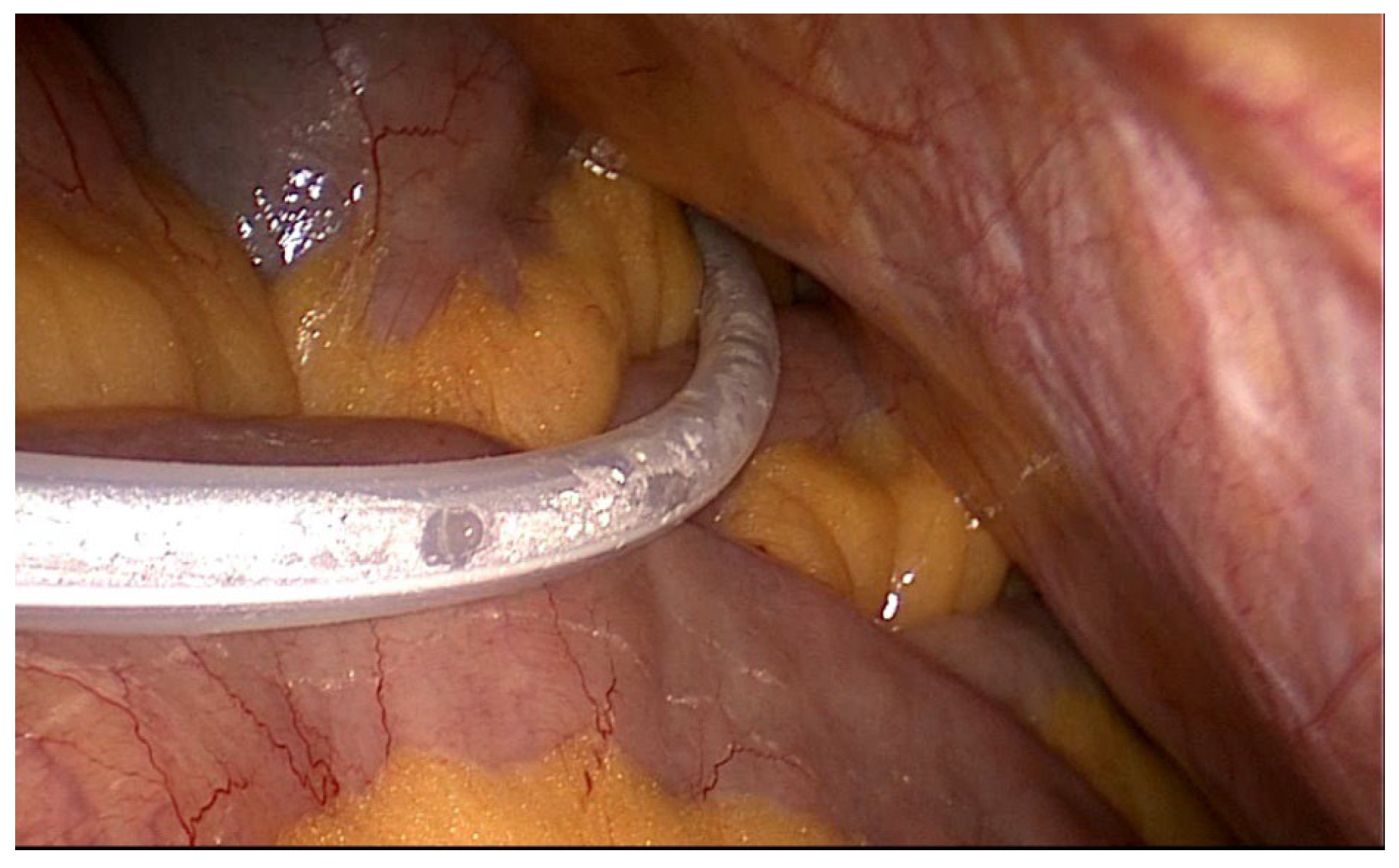

14]– Image 1.

Image 1 – final laparoscopic view position of the catheter.

Performing adhesiolysis laparoscopically facilitates the possibility for patients who have had prior surgical interventions to benefit from the laparoscopic insertion of the PD catheter as the placement by open technique is much more susceptible to incidents. [

15]

In the study group, there were 22 (17%) patients who presented viscero-parietal adhesions (9.5% of patients with previous surgical interventions).

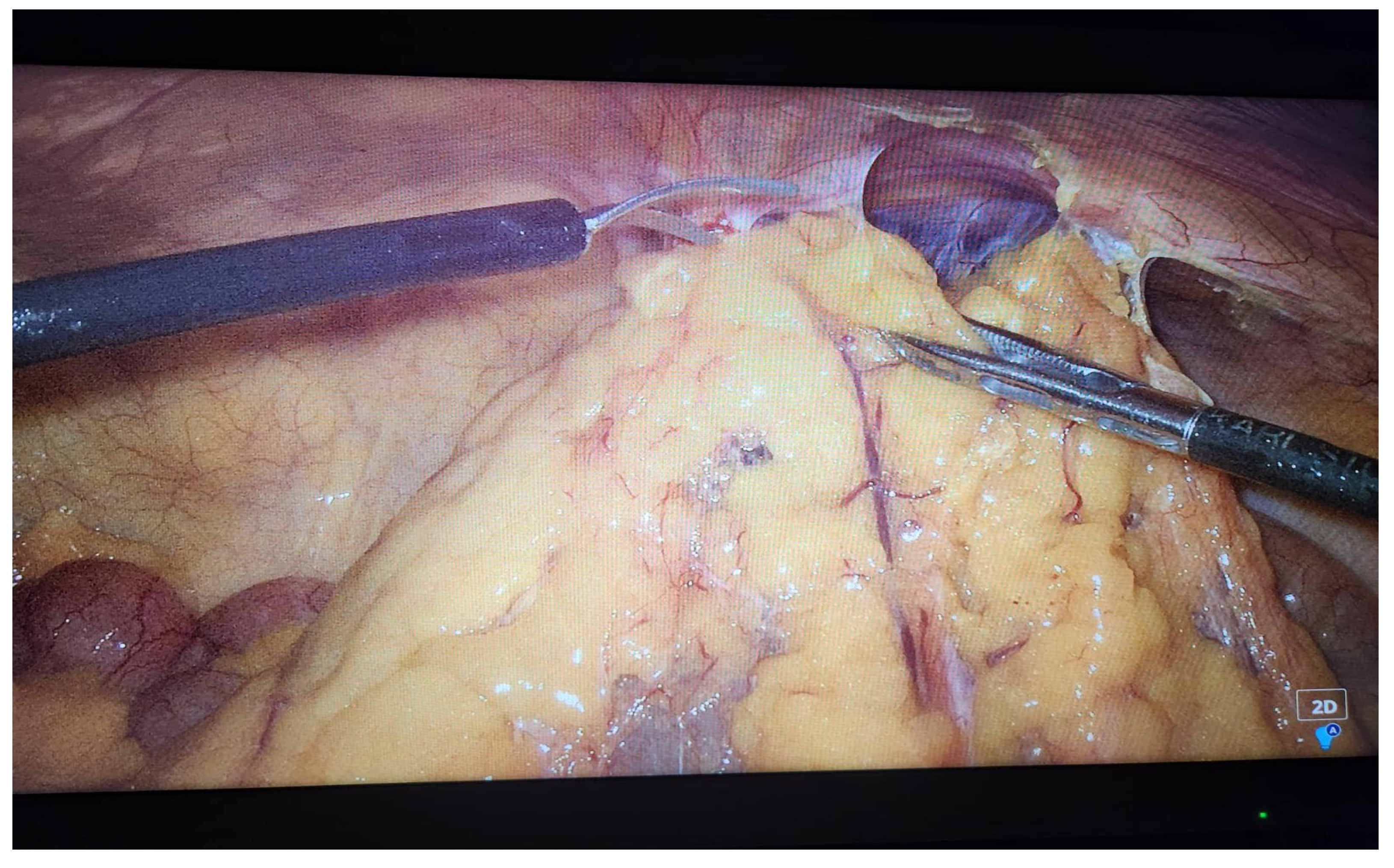

All patients underwent laparoscopic adhesiolysis without intraoperative incidents using various electro-surgery instruments or a blunt instrumental dissection if intestinal loops were present near the adhesions. ( Image 2)

Image 2 – laparoscopic adhesiolysis.

Performing adhesiolysis increases the duration of the operative time - from our study by 30 min on average) but it presents a great advantage, leaving at the end of the surgical intervention, a peritoneal cavity without compartments thus preventing further complications of PD and finally PD failure.

Another advantage of laparoscopic placing is the visible fixation of the catheter at the exit site from the peritoneum, this maneuver also preventing catheter migration. [

16,

17] Other authors prefer fixing the catheter at the pelvic level [

10]. For all patients in whom the catheter was mounted laparoscopically, we performed its attachment at peritoneal exit point.

We do not prefer securing the catheter at the pelvic level because at the time of extraction the maneuver could become much more laborious, requiring either laparoscopic approach or open surgery.

Migration of the catheter occurred in a single patient at week 3 with the initiation of exchanges

The catheter was repositioned and secured to the abdominal wall laparoscopically. Afterwards the catheter worked optimally.

As we explained previously, the mounting technique we were practicing does not include securing the large omentum because after this maneuver extensive adhesions are formed between the large omentum and anterior abdominal wall. If this patient will require a surgical intervention in the future the adhesion process would determine a much more laborious surgical intervention whether it is a laparoscopic or open intervention or an even impossible intervention by laparoscopic surgery.

We consider that if omentum wrapping occurs we will perform the desobstruction of the catheter and laparoscopic partial omentectomy, so that the great omentum would no longer reach the catheter.

Although data from the literature shows a percentage between 3-20% of omentum wrapping, in our study this complication did not occur in any patient [

18].

The overall risk of bleeding is increased in patients initiating dialysis therapy primarily due to uremic toxin-induced platelet dysfunction and the underlying cardio-vascular pathology requiring frequent anticoagulant and (or) antiplatelet treatment [

19].

Bleeding is common peri-procedurally, regardless of whether the implantation is by open or laparoscopic technique, but in most cases, it is minor, self-limited and due to tissue trauma during insertion.

The bleeding is located at the level of the catheter outlet or intra-abdominal [

20,

21,

22,

23], this being already present during the procedure and, although insignificant from the hemodynamic point of view, it is the cause of catheter dysfunction in nearly two-thirds of cases.

Peritoneal lavage initiated early post-operatively allows blood to be removed and catheter patency preserved [

24]. The clinically significant bleeding requiring emergency medical or surgical intervention complicates 2-3% of procedures [

25].

Causes include adhesiolysis, inferior mesenteric artery injury, erosion of a blood vessel by the tip of the catheter, damage to a collateral blood vessel at the level of the abdominal wall, damage to the mesenteries, damage to the rectus abdominis muscle [

20,

21,

26].

In our study, we encountered one patient (0.8%) who presented bleeding from the catheter tunnel, a complication that was resolved successfully on the spot by securing the anchor wire of the catheter.

If lesions appear, they must be identified immediately and require surgical intervention.

In these cases, laparoscopy technique proves its superiority over other techniques by immediately visualizing the hemorrhagic lesions and also by providing the possibility of immediate surgical hemostasis. [

18]

One complication that can lead to changing the catheter is the peri-catheter leakage.

Contrary to the data from the specialty literature, in our study the frequency of peri-catheter leakage was low (4%) [

24,

25]

In the majority of cases this spontaneously resolved (between 1 and 4 weeks).

For the 5th patient, for the continuation of PD it was necessary the extraction of the catheter and reinsertion in the right flank through the previous laparoscopic procedure described above.

The cause of the peri-catheter leakage was the poor adherence of the deep cuff to the surrounding tissues, which was not related to the insertion method.

Infections associated with peritoneal dialysis are of major importance as they represent the first cause of permanent abandonment of technique (technique failure) [

27]

Contamination during surgery can be a cause but, as far as we know, this risk factor has not been evaluated yet [

28,

29,

30].

Data from the literature shows that peritonitis soon after catheter implantation (pre-training peritonitis) compared with post-training peritonitis and peritonitis have worse prognosis (more frequent transfer in hemodialysis, death, shorter PD technique survival) [

29].

Although infections represented two thirds of the total complications, the incidence of pre-training infection was lower (0.08% of all incident patients) compared to incidents reported in studies that followed the epidemiology and prognosis of pre-training peritonitis (4 - 17.7%) [

29,

30].

After 3 months, only one single patient was switched from PD to HD - resulting in a percentage of 99.2% of functionality of the catheter and the dialysis method.

Although the latest ISPD guidelines establish the procedures related to all aspects discussed in the literature, 2 more important topics are intensively debated, namely - who should install the catheter for PD and what is the best insertion technique to be able to ensure as long of a working life as possible and as much as possible without PD complications.

The installation of the catheter for PD must be performed by well-trained teams regardless of whether the installation is performed by a nephrologist/interventional radiologist or a surgeon. Each geographical area has its particularities both in terms of patient selection and development and implementation of various types of insertion techniques [

31,

32,

33]

From the analysis of the literature, there are constant concerns that analyze the advantages and disadvantages of different PD catheter insertion methods. [

34]

Most studies make references and comparisons of only 2 methods – either laparoscopic/open (most studies); open/percutaneous; [

34,

35,

36,

37]

I have not found any studies in the literature that compare and analyze several types of mounting together with the advantages and complications that can appear both early and late post procedure.

From the meta-analyses published by Sun et all, Agarwal et all, van Laanen et all, the laparoscopic catheter mounting for PD presents important advantages. These advantages are represented by a reduced percentage of early mechanical complications of catheter insertion such as migration, obstructions, peri-catheter leaks, bleeding and perforations of cavitary intraperitoneal organs, something that significantly contributes to the optimal functioning of the PD catheter. [

38,

39,

40]

Our study as well demonstrates good results of the laparoscopic PD catheter insertion technique, the early complications being few in number and the great majority being able to be treated by specific oral medication therapy or through laparoscopic surgical treatment, thus ensuring continuation of PD. Also demonstrates the superiority of the laparoscopic insertion for the patients with intraperitoneal adhesions (postoperative or in situ).

The presented study has a limitation due to the lack of a statistically significant group of patients for which insertion of the catheter was carried out through open technique.

5. Conclusions

Laparoscopic catheter insertion for PD is a safe method, with reduced post-procedural complications, thus ensuring a long duration of the functionality of the catheter.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.I. and C.R.I.; methodology, I.A.; software, I.A.; validation, C.I., S.H.S. and V.S.; formal analysis, I.B.; investigation, T.C; resources, C.R.I. and I.A..; data curation, V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.I.; writing—review and editing, C.I.; visualization, C.I..; supervision, S.H.S..; project administration, C.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- R. A. Pyper, Peritoneal Dialysis -Ulster Med J ,v.17(2); 1948 Nov PMC2479482.

- Sana F. Khan and Mitchell H. Rosner, Optimizing peritoneal dialysis catheter placement Front Nephrol ,v.3; 2023 , PMC10479565, Published online 2023 Apr 11. [CrossRef]

- Xingzhe Gao,* Zhiguo Peng,* Engang Li, and Jun Tian Modified minimally invasive laparoscopic peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion with internal fixation, Ren Fail v.45(1); 2023 PMC9848322, Published online 2023 Jan12. [CrossRef]

- Stefano Santarelli, et all The peritoneal dialysis catheter, J Nephrol. 2013 Nov-Dec;26 Suppl 21:4-75. [CrossRef]

- Wong LP, Liebman SE, Wakefield KA, Messing S. Training of surgeons in peritoneal dialysis catheter placement in the United States: a national survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Aug;5(8):1439-46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John H. Crabtree,1 Badri M. Shrestha,2 Kai-Ming Chow,3 Ana E. Figueiredo,4 Johan V. Povlsen,5 Martin Wilkie,2 Ahmed Abdel-Aal,6 Brett Cullis,7 Bak-Leong Goh,8 Victoria R. Briggs,9 Edwina A. Brown,10 and Frank J.M.F. Dor10, 11 Perit Dial Int 2019; 39(5):414–436 epub ahead of print: 26 Apr 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ultrasound-guided percutaneous peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion using multifunctional bladder paracentesis trocar: A modified percutaneous PD catheter placement technique.

- Zhen Li, Hongyun Ding, Xue Liu, Jianbin Zhang.

- Semin Dial. 2020 Mar-Apr; 33(2): 133–139. Published online 2020 Mar 11. [CrossRef]

- Modified Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Insertion: Comparison with a Conventional Method Yong Kyu Lee, Pil-Sung Yang, Kyoung Sook Park, Kyu Hun Choi, Beom Seok Kim, Yonsei Med J. 2015 Jul 1; 56(4): 981–986. Published online 2015 Jun 5. [CrossRef]

- LAPAROSCOPIC PERITONEAL DIALYSIS CATHETER PLACEMENT WITH RECTUS SHEATH TUNNELING: A ONE-PORT SIMPLIFIED TECHNIQUE Ana Carolina Buffara BLITZKOW, Gilson BIAGINI, Carlos Antonio SABBAG, Victor Assad BUFFARA-JUNIOR, Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2022; 35: e1690. Published online 2022 Sep 16. [CrossRef]

- van Laanen JHH, Litjens EJ, Snoeijs M, van Loon MM, Peppelenbosch AG. Introduction of advanced laparoscopy for peritoneal dialysis catheter placement and the outcome in a University Hospital. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022 Jun;54(6):1391-1398. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree JH, Penner T, Armstrong SW, Burkart J. Peritoneal Dialysis University for Surgeons: A Peritoneal Access Training Program. Perit Dial Int. 2016 Mar-Apr;36(2):177-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree JH. Who should place peritoneal dialysis catheters? Perit Dial Int. 2010 Mar-Apr;30(2):142-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra R, Blake P, Berman N, Nolph KD. An analysis of dialysis training in the United States and Canada. Am J Kidney Dis 2002, 40, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou HW, Yeh CN, Tsai CY, Liu SH, Ho WY, Lee CW, Wang SY, Chang MY, Tian YC, Hsu JT, Hwang TL. Clinical Benefits of Laparoscopic Adhesiolysis during Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Insertion: A Single-Center Experience. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023 May 24;59(6):1014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree JH. Previous abdominal surgery is not necessarily a contraindication for peritoneal dialysis. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008 Jan;4(1):16-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Laanen JHH, Cornelis T, Mees BM, Litjens EJ, van Loon MM, Tordoir JHM, Peppelenbosch AG. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Open Versus Laparoscopic Placement of a Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter and Outcomes: The CAPD I Trial. Perit Dial Int. 2018 Mar-Apr;38(2):104-112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Y, Shao Y, Xu J. The Survival and Complication Rates of Laparoscopic Versus Open Catheter Placement in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015 Oct;25(5):440-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu J, Liu Z, Liu J, Zhang H. Reducing the occurrence rate of catheter dysfunction in peritoneal dialysis: a single-center experience about CQI. Ren Fail. 2018 Nov;40(1):628-633. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohal AS, Gangji AS, Crowther MA, Treleaven D. Uremic bleeding: pathophysiology and clinical risk factors. Thromb Res. 2006, 118, 417–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree JH, Chow KM. Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Insertion. Semin Nephrol. 2017 Jan;37(1):17-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li JR, Chen CH, Chiu KY, Yang CR, Cheng CL, Ou YC, Ko JL, Ho HC. Management of pericannular bleeding after peritoneal dialysis catheter placement. Perit Dial Int. 2012, 32, 361–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Xiang S, Wang Y, Liu G, Xie X, Han F, Chen J. Laparoscopic vs open surgical insertion of peritoneal dialysis catheters: A propensity score-matched cohort study. Curr Probl Surg. 2024, 61, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu J, Liu Z, Liu J, Zhang H. Reducing the occurrence rate of catheter dysfunction in peritoneal dialysis: a single-center experience about CQI. Ren Fail. 2018 Nov;40(1):628-633. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadallah MF, Torres-Rivera C, Ramdeen G, Myrick S, Habashi S, Andrews G. Relationship between intraperitoneal bleeding, adhesions, and peritoneal dialysis catheter failure: a method of prevention. Adv Perit Dial. 2001, 17, 127–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lu CT, Watson DI, Elias TJ, Faull RJ, Clarkson AR, Bannister KM. Laparoscopic placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters: 7 years experience. ANZ J Surg. 2003, 73, 109–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natroshvili T, Elling T, Dam SA, Vd Berg M, Nap RRH, Hissink RJ. A Rare Cause of Persistent Blood Loss after Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Placement. Case Rep Surg. 2020, 2020, 1309418. [Google Scholar]

- Bonenkamp AA, van Eck van der Sluijs A, Dekker FW, Struijk DG, de Fijter CW, Vermeeren YM, van Ittersum FJ, Verhaar MC, van Jaarsveld BC, Abrahams AC. Technique failure in peritoneal dialysis: Modifiable causes and patient-specific risk factors. Perit Dial Int. 2023, 43, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerschbaum J, König P, Rudnicki M. Risk factors associated with peritoneal-dialysis-related peritonitis. Int J Nephrol. 2012, 2012, 483250. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat A, Johnson DW, Hawley CM, Jaffrey LR, Mahmood U, Mon SSY, Cho Y. Associations, microbiology and outcomes of pre-training peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis. Perit Dial Int. 2023, 43, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma TK, Chow KM, Kwan BC, Pang WF, Leung CB, Li PK, Szeto CC. Peritonitis before Peritoneal Dialysis Training: Analysis of Causative Organisms, Clinical Outcomes, Risk Factors, and Long-Term Consequences. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016, 11, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip Kam-tao Li and Kai Ming Chow. Importance of peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion by nephrologists: practice makes perfect. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009, 24, 3274–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Henderson et al. Safety and efficacy of percutaneous insertion of peritoneal dialysis catheters under sedation and local anaesthetic. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009, 24, 3499–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasim Shahbazi MD , Brendan B. McCormick MD. Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Insertion Strategies and Maintenance Of Catheter Function. Seminars in Nephrology 2011, 31, 38–151. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaohui Zhang , Shilong Xiang , Yaomin Wang, Guangjun Liu, Xishao Xie, Fei Han, Jianghua Chen. Laparoscopic vs open surgical insertion of peritoneal dialysis catheters: A propensity score-matched cohort study. Current Problems in Surgery 2024, 61, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. YU ∗ 1, J. Li 1, Y. Qiu 1, Y. Ouyang 1, X. Xia 1, X. Lin 1, C. Yi 1, F. Huang 1, W. Chen 1, Q. Liu, WCN23-1153 A MODIFIED PERITONEAL DIALYSIS CATHETER INSERTION PROCEDURE BASED ON SELDINGER TECHNIQUE: COMPARSION WITH CONVENTIONAL SURGICAL METHOD, Kidney International Reports Volume 8, Issue 3, Supplement, March 2023, Page S365.

- Jwo SC, Chen KS, Lee CC, Chen HY. Prospective randomized study for comparison of open surgery with laparoscopic-assisted placement of Tenckhoff peritoneal dialysis catheter--a single center experience and literature review. J Surg Res. 2010 Mar;159(1):489-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen SM, van Alphen AM, Ijzermans JN, Dor FJ. Laparoscopic versus open peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion, the LOCI-trial: a study protocol. BMC Surg. 2011 Dec 20;11:35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun ML, Zhang Y, Wang B, Ma TA, Jiang H, Hu SL, Zhang P, Tuo YH. Randomized controlled trials for comparison of laparoscopic versus conventional open catheter placement in peritoneal dialysis patients: a meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2020 Feb 24;21(1):60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal A, Whitlock RH, Bamforth RJ, Ferguson TW, Sabourin JM, Hu Q, Armstrong S, Rigatto C, Tangri N, Dunsmore S, Komenda P. Percutaneous Versus Surgical Insertion of Peritoneal Dialysis Catheters: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021 Nov 8;8:20543581211052731. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Y, Shao Y, Xu J. The Survival and Complication Rates of Laparoscopic Versus Open Catheter Placement in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015 Oct;25(5):440-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).