Submitted:

01 April 2024

Posted:

02 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Isolation of Double-Stranded (ds) RNA

Isolation of Total RNA

Stranded Total RNA Sequencing

Bioinformatics

Data Preprocessing

Host Reads Removal

Discovery of Known Virus

Discovery of Novel Viruses

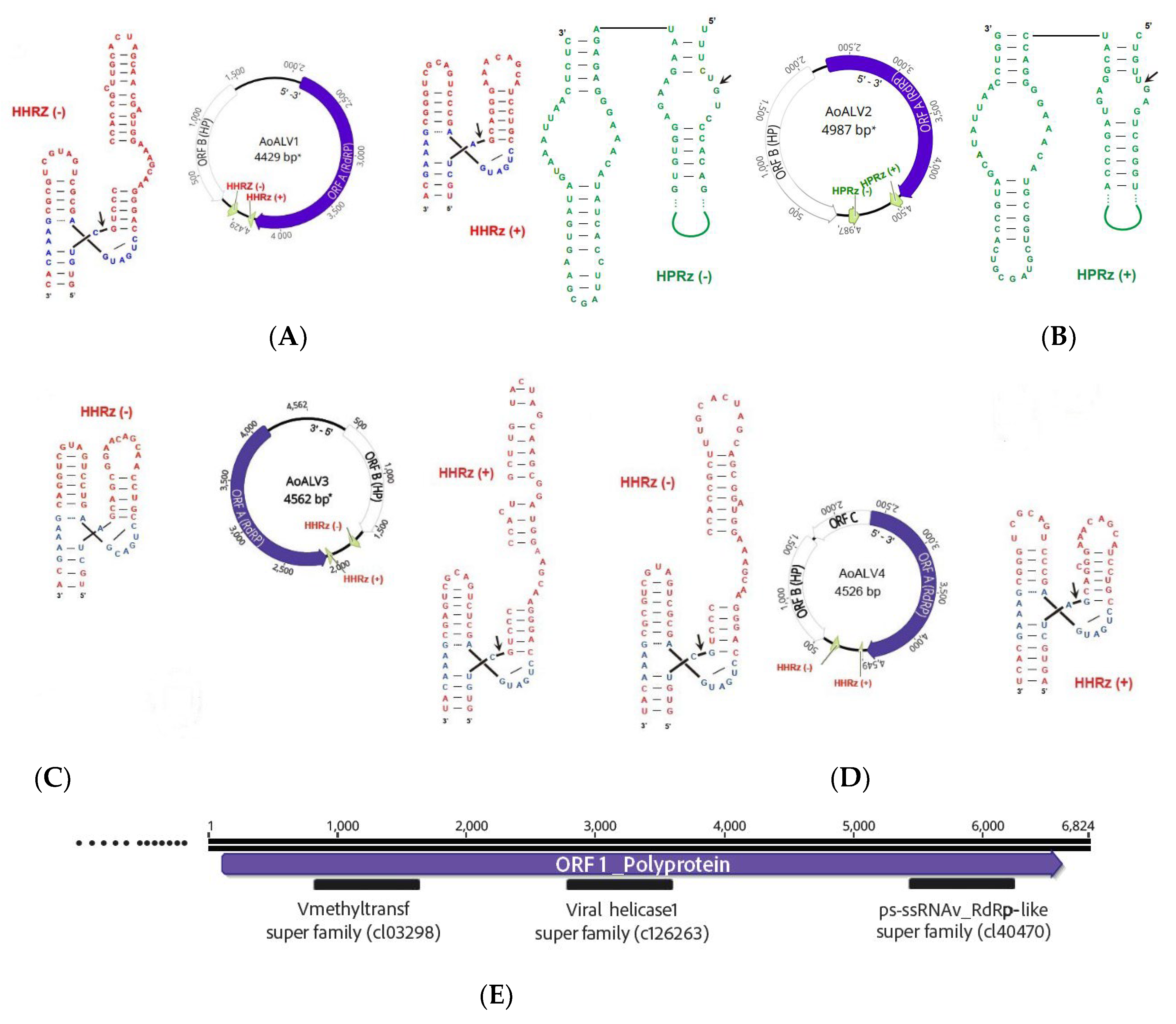

Ribozymes Detection

Retro Transcription (RT) PCR and Sanger Sequencing

Conserved Domains

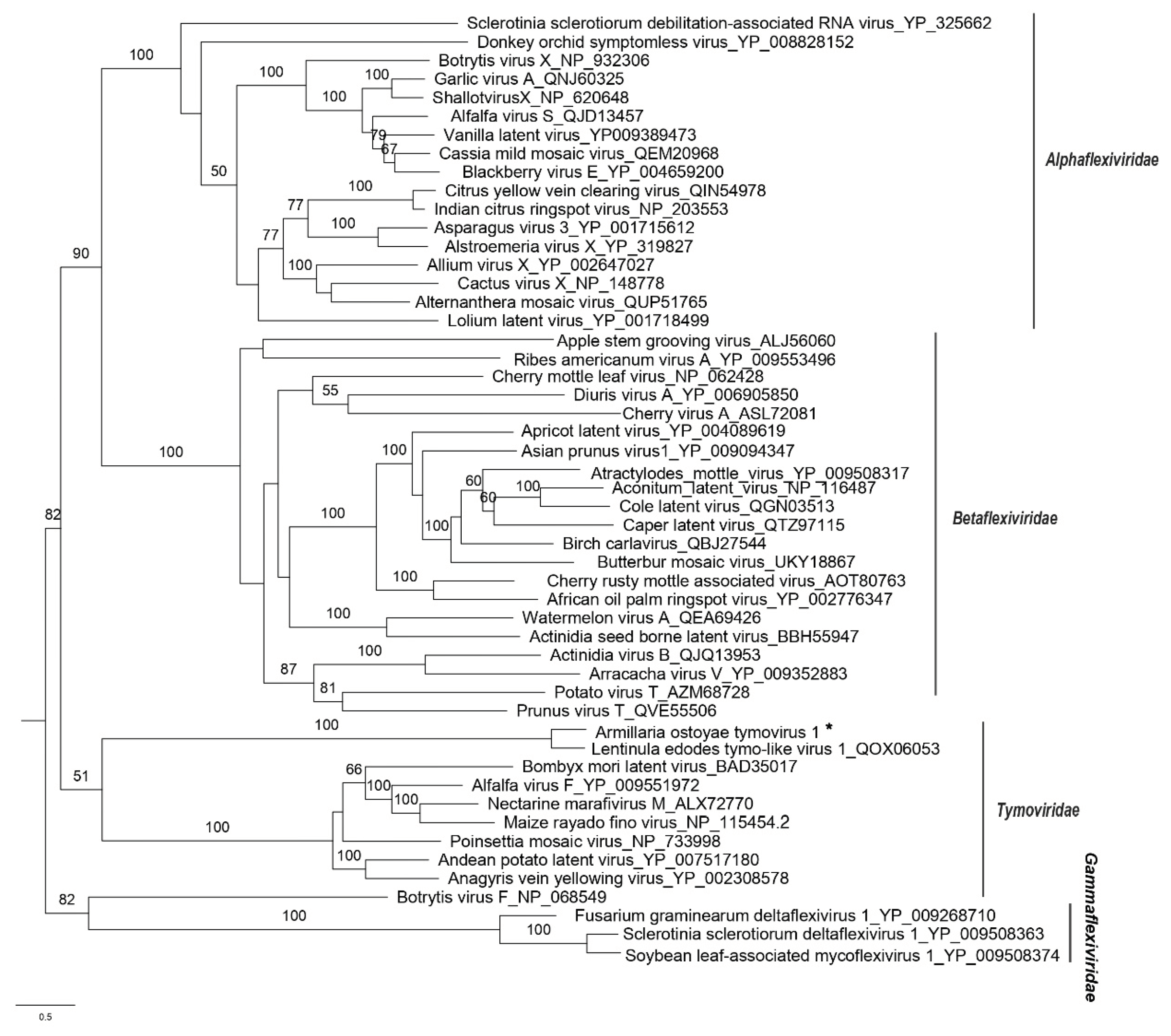

Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

dsRNA Screening

Identification of Final ssRNA Viral Sequences

RT-PCR Screening

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Availability of data and materials

Competing interests

References

- Hansen, E.M. , Goheen E.M. Phellinus weirii and other native root pathogens as determinants of forest structure and process in Western North America. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 2000, 38, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, G.S. Evolutionary ecology of plant diseases in natural ecosystems. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 2002, 40, 13–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coetzee, M. , Wingfield B. D., Wingfield M. J. Armillaria root-rot pathogens: Species boundaries and global distribution. Pathogens. 2018, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.E. , Shaw C.G., Wargo P.M., Sites W.H. (1989). Armillaria Root Disease In: Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 78. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service; 1986.

- Baumgartner, K. , Coetzee M., Hoffmeister D. Secrets of the subterranean pathosystem of Armillaria. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holuša, J. , Lubojacký J., Čurn V., Tonka T., Resnerová K., Horák J., Combined effects of drought stress and Armillaria infection on tree mortality in Norway spruce plantations. For. Ecol. Manage. 2018, 427, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienciala, E. , Tumajer J., Zatloukal V., Beranová J., Holá Š., Hůnová I., Russ R. Recent spruce decline with biotic pathogen infestation as a result of interacting climate, deposition and soil variables. Eur. J. Forest. Res. 2017, 136, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turčáni, M. Podiel podkorneho hmyzu na hynutí smrekových porastov postihnutých žltnutím. In: Zúbrik, M. editor: Aktuálne problémy v ochrane lesa. Lesnický výskumný ústav. 2001; 56–60.

- Jankovský, L. Role houbových patogenů v chřadnutí smrku. Collection of lectures of the professional seminar Budišov nad Budišovkou. Research Institute of Forestry and Hunting. 2014; 20–30.

- Garcia, O. A simple and effective forest stand mortality model. Mathematical and Computational Forestry & Natural-Resource Sciences. 2009, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mantgem, P.J. , Stephenson N.L., Byrne J.C., Daniels L.D., Franklin J.F., Fulé P.Z., Harmon M.E., Larson A.J., Smith J.M., Taylor A.H., Veblen T.T. Widespread increase of tree mortality rates in the western United States. Science. 2009, 323, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary M., R. , Arhipova N., Morrison D.J., Thomsen I.M., Sturrock R.N. et al. Stump removal to control root disease in Canada and Scandinavia: A synthesis of results from long-term trial. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 290, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnakoski, R. , Sutela S., Coetzee M. P. A., Duong T. A., Pavlov I. N., Litovka Y. A. Armillaria root rot fungi host single-stranded RNA viruses. Scientific reports. 2021, 11, 7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prospero, S. , Botella L., Santini A., Robin C. Biological control of emerging forest diseases: How can we move from dreams to reality? Forest Ecology and Management. 2021, 496, 119377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuss D., L. Hypovirulence: Mycoviruses at the fungal-plant interface. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2005, 3, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pedrajas M., D. , Cañizares M. C., Sarmiento-Villamil J. L., Jacquat A. G., Dambolena J. S. Mycoviruses in Biological Control: From Basic Research to Field Implementation. Phytopathology. 2019, 109, 1828–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonka, T. , Walterova L. , Curn V. Biological control of pathogenic fungi: Can mycoviruses play an important role? Journal of Central European Agriculture. 2022, 23, 540–551. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Adalia E., J. , Fernández M. M., Diez J. J. The use of mycoviruses in the control of forest diseases. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 2016, 26, 577–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio E., J. , Jurvansuu J., Hyder R., Kashif M., Piri T., Tuomivirta T., Poimala A., Xu P., Mäkelä S., Nitisa D., Hantula J. Heterobasidion partitivirus 13 mediates severe growth debilitation and major alterations in the gene expression of a fungal forest pathogen. Journal of Virology. 2018, 92, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutela, S. , Piri T., Vainio E. J. Discovery and community dynamics of novel ssRNA mycoviruses in the conifer pathogen Heterobasidion parviporum. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattny, C. , Kralik O., Veselsky J., Kasala B., Herzova H. Particles resembling virions accompanying the proliferation of Agaric mushrooms. Česká Mykologie. 1973, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Reaves J., L. , Allen T. C., Shaw C. G., Dashek W. V., Mayfield J. E. Occurrence of virus like particles in isolates of Armillaria. J. Ultrastruct. Mol. Struct. Res. 1988, 98, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonka, T. , Walterová L., Hejna O., Čurn V. Molecular characterization of a ssRNA mycovirus isolated from the forest pathogenic fungus Armillaria ostoyae. Acta Virol. 2022, 66, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, W. , Heinzelmann R., Ulrich S., Kondo H. and Cornejo C. Decoding the RNA virome of the tree parasite Armillaria provides new insights into the viral community of soil-borne fungi. Environmental Microbiology, 2024, 26. [CrossRef]

- Morris T., J. and Dodds J. A. Isolation and analysis of double-stranded RNA from virus-infected plant and fungal tissue. Phytopathology. 1979, 69, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonka, T. , Walterová L., Hejna O., Čurn V. Metodika identifikace, determinace a přenosu mykovirů u hub rodu Armillaria. Zemědělská fak. JU v Č. Budějovicích.

- Botella, L. , Dvořák M., Capretti P., Luchi N. Effect of temperature on G a RV 6 accumulation and its fungal host, the conifer pathogen Gremmeniella abietina. Forest Pathology. 2017, 47, 12291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, L. , Jung T. Multiple viral infections detected in Phytophthora condilina by total and small RNA sequencing. Viruses. 2021, 13, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. Babraham bioinformatics - FastQC A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Soil. 2010; Available at: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc.

- Illumina Adapter Sequences, Available at: https://emea.support.illumina.com/downloads/illumina-adapter-sequences-document-1000000002694.html.

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences From High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. 2012, Available at: https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable.

- GitHub, Available at: https://github.com/marcelm/cutadapt.

- Dobin, A. , Davies C. A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski Ch., Sonali J., Philippe B., Mark Ch., Thomas R. G. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viral NCBI, Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/virus/vssi/#/.

- Burrows-Wheeler Alingner, Available at: https://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/.

- IGV, Available at: https://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/.

- Bankevich, A. , Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., Lesin V. M., et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012, Available at: https://cab.spbu.ru/software/spades. [CrossRef]

- Viral UniProtKB, Available at: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb?query=10239. 1023.

- RVDB, Available at: https://rvdb.dbi.udel.edu/.

- Virus-Host DB, Available at: https://www.genome.jp/virushostdb/.

- Lee, B. D. , Neri, U., Roux, S., Wolf, Y. I., Camargo, A. P., Krupovic, M. et al. Mining metatranscriptomes reveals a vast world of viroid-like circular RNAs. Cell 2023, 186, 646–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y. , Xu, T., Lin, W., Jia, Q., He, Q., Liu, K., et al. (2020). Reference-free and de novo Identification of Circular RNAs. bioRxiv, 2020-04.

- Nawrocki, E. P. , and Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2933–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macke, T. J. , Ecker, D. J., Gutell, R. R., Gautheret, D., Case, D. A., and Sampath, R. RNAMotif, an RNA secondary structure definition and search algorithm. Nucleic acids research 2001, 29, 4724–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonka, T. , Walterová L., Čurn V. Development of RT-PCR for rapid detection of ssRNA ambi-like mycovirus in a root rot fungi (Armillaria spp.). Acta Virol. 2022, 66, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čurn, V. , Tonka T., Křížová L., Jozová E. Metodika izolace DNA analýzy molekulárních markerů u hub, České Budějovice, 20019.

- NCBI CD-search tool, Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi.

- Edgar R., C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. , Hoover P., Rougemont J., Diego S., Jolla L. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 2008, 57, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller M., A. , Pfeiffer W., Schwartz T. Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In 2010 gateway computing environments workshop. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Sutela, S. , Forgia M., Vainio E. J., Chiapello M., Daghino S., Vallino M., Martino E., Girlanda M., Perotto S., Turina M. The virome from a collection of endomycorrhizal fungi reveals new viral taxa with unprecedented genome organization. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgia, M. , Isgandarli E., Aghayeva D. N., Huseynova I., Turina M. Virome characterization of Cryphonectria parasitica isolates from Azerbaijan unveiled a new mymonavirus and a putative new RNA virus unrelated to described viral sequences. Virology. 2021, 553, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgia, M. , Navarro B., Daghino S., Cervera A., Gisel A., Perotto S., Aghayeva N. D. et al. Hybrids of RNA viruses and viroid-like elements replicate in fungi. Nature Communications. 2023, 14, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvořak, J. Výskyt RNA elementů u rodu Armillaria. Diplomova prace. Univerzita Karlova, Přirodovědecka fakulta, Katedra genetiky a mikrobiologie. 2008.

- Drenkhan, T. , Sutela S. , Veeväli V., Vainio E. J. Phlebiopsis gigantea strains from Estonia show potential as native biocontrol agents against Heterobasidion root rot and contain diverse dsRNA and ssRNA viruses. Biological Control, 2022, 167, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. , Wang J. , Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M. K., Geer R. C., Gonzales N. R. et al. CDD/SPARCLE: the conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams M., J. , Kreuze J. F., and Martelli G. P. “Tymovirales,” in Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 2011; 901–903.

- King A. M., Q. , Michael J., Carstens E. B., Lefkowitz E. J. Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Amsterdam; American Press/Elsevier; 2012.

- Howitt R., L. , Beever R. E., Pearson M. N., Forster R. L. Genome characterization of botrytis virus F, aflexuous rod-shaped mycovirus resembling plant ‘potex-like’ viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams M., J. , Candresse T., Hammond J., Kreuze J. F., Martelli G. P., Namba S., et al. “Alphaflexiviridae,” in Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 2011, 904–919. [Google Scholar]

- Howitt R., L. , Beever R. E., Pearson M. N., Forster, R. L. Genome characterization of a flexuous rod-shaped mycovirus, botrytis virus X, reveals high amino acid identity to genes from plant ‘potex-like’ viruses. Arch. Virol. 2006, 151, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. , Zheng D., Cheng J., Chen T., Fu Y., Jiang D., et al. Characterization of a novel Sclerotinia sclerotiorum RNA virus as the prototype of a new proposed family within the order Tymovirales. Virus Res. 2016, 219, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. , Lin Y., Zhang H., Wang S., Qiu D., Guo L. Molecular characterization of a novel mycovirus of the family Tymoviridae isolated from the plant pathogenic fungus Fusarium graminearum. Virology. 2016, 489, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomaus, A. , Wibberg D., Winkler A., Puhler A., Schluter A., Varrelmann M., et al. Identification of a novel mycovirus isolated from Rhizoctonia solani (AG 2-2 IV) provides further information about genome plasticity within the order Tymovirales. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, Y. , Abraham A., Uesaka K., Kondo H., Suga H., Suzuki N., et al. Novel mitoviruses and a unique tymo-like virus in hypovirulent and virulent strains of the Fusarium head blight fungus, Fusarium boothii. Viruses. 2018, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, A. , Kevei F., Hoekstra R. F. Factors affecting the spread of double-stranded RNA viruses in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetical Research. 1997, 69, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melzer M., S. , Ikeda S.S., Boland G.J. Interspecific transmission of double-stranded RNA and hypovirulence from Sclerotinia sclerotiorum to S. minor. Phytopathology. 2002, 92, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y. , Linder-Basso D., Hillman B., Kaneko S., Milgroom M. et al. Evidence for interspecies transmission of viruses in natural populations of filamentous fungi in the genus Cryphonectria. Molecular Ecology. 2003, 12, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrmark, K. , Johannesson H., Stenström E., Stenlid J. Transmission of double-stranded RNA in Heterobasidion annosum. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2002, 36, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainio, E.J. , Korhonen K., Tuomivirta T. T., Hantula J. A novel putative partitivirus of the saprotrophic fungus Heterobasidion ecrustosum infects pathogenic species of the Heterobasidion annosum complex. Fungal Biology. 2010, 114, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, E.J. , Hakanpää J., Dai Y. C., Hansen E., Korhonen K., Hantula J. Species of Heterobasidion host a diverse pool of partitiviruses with global distribution and interspecies transmission. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolate code | Fungal species | Site Coordinates | Country | Tree host | Fungal material | Collection date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. cepistipes | 49.5147885N,17.5546327E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Rhizomorphs | 29.9.2020 |

| 2 | A. ostoyae | 48.9813906N,14.4205031E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Fruiting body | 31.10.2019 |

| 3 | A. ostoyae | 49.81582N, 17.34951 E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Fruiting body | 27.10.2019 |

| 4 | A. ostoyae | 48.6232622N,14.6442581E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Fruiting body | 16.10.2019 |

| 5 | A. ostoyae | 50.10238N, 16.0683E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Fruiting body | 23.10.2019 |

| 6 | A. ostoyae | 49.5226228N,17.5717912E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Rhizomorphs | 5.9.2019 |

| 7 | A. ostoyae | 49.8084936N,17.4939458E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Rhizomorphs | 4.8.2020 |

| 8 | A. ostoyae | 49.31372N, 16.77221 E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Fruiting body | 23.10.2019 |

| 9 | A. ostoyae | 48.6078636N,14.6688486E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Fruiting body | 21.10.2019 |

| 10 | A. ostoyae | 49.8084936N,17.4939458E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Rhizomorphs | 4.8.2020 |

| 11 | A. ostoyae | 49.32247N, 16.78645 E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Fruiting body | 23.10.2019 |

| 12 | A. ostoyae | 48.9815597N,14.4162544E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Fruiting body | 4.11.2020 |

| 13 | A. ostoyae | 49.5419285N,17.3919515E | Czech Republic | Picea abies | Rhizomorphs | 14.8.2019 |

| Virus name | Acronym | L | Accession numbera | Most similar virusb | E value | Q (%) | I (%) | Mapped Reads | Depth of coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armillaria ambi-like virus 1 |

AALV1 | 4663 | ON380550 | Armillaria ambi-like virus 3 | 0.0 | 99 | 97.55 | 24,902 | 780.91 |

| Armillaria ostoyae ambi-like virus 2 |

AoALV2 | 4541 | ON380551 | Phlebiopsis gigantea ambi-like virus 2 | 2,00 E-103 | 41 | 36.65 | 27,239 | 863.10 |

| Armillaria ostoyae ambi-like virus 3 |

AoALV3 | 4562 | ON380552 | Armillaria mellea ambi-like virus 2 | 0.0 | 46 | 78.78 | 21,362 | 678.90 |

| Armillaria ostoyae ambi-like virus 4 |

AoALV4 | 4549 | ON380553 | Armillaria ambi-like virus 3 | 0.0 | 46 | 91.57 | 6169 | 196.26 |

| Armillaria ostoyae tymovirus 1 |

AoTV | 6824 | ON380554 | Lentinula edodes tymo-like virus 1 | 0.0 | 94 | 68.16 | 4959 | 106.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).