Submitted:

29 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Conception of the New Device (Step by Step)

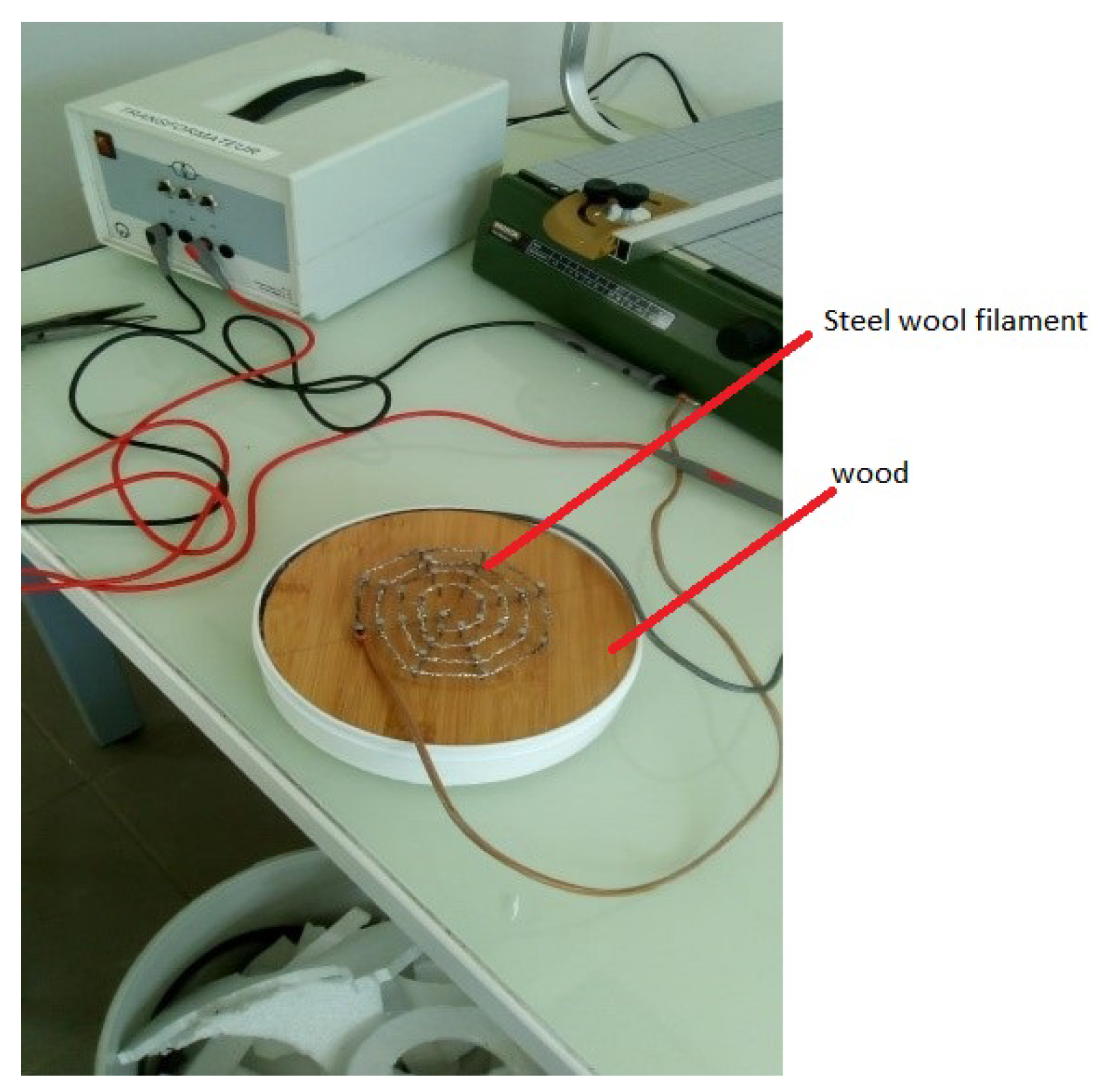

3.1. A Hot Source: Steel Wool

3.2. Flat Steel Iron

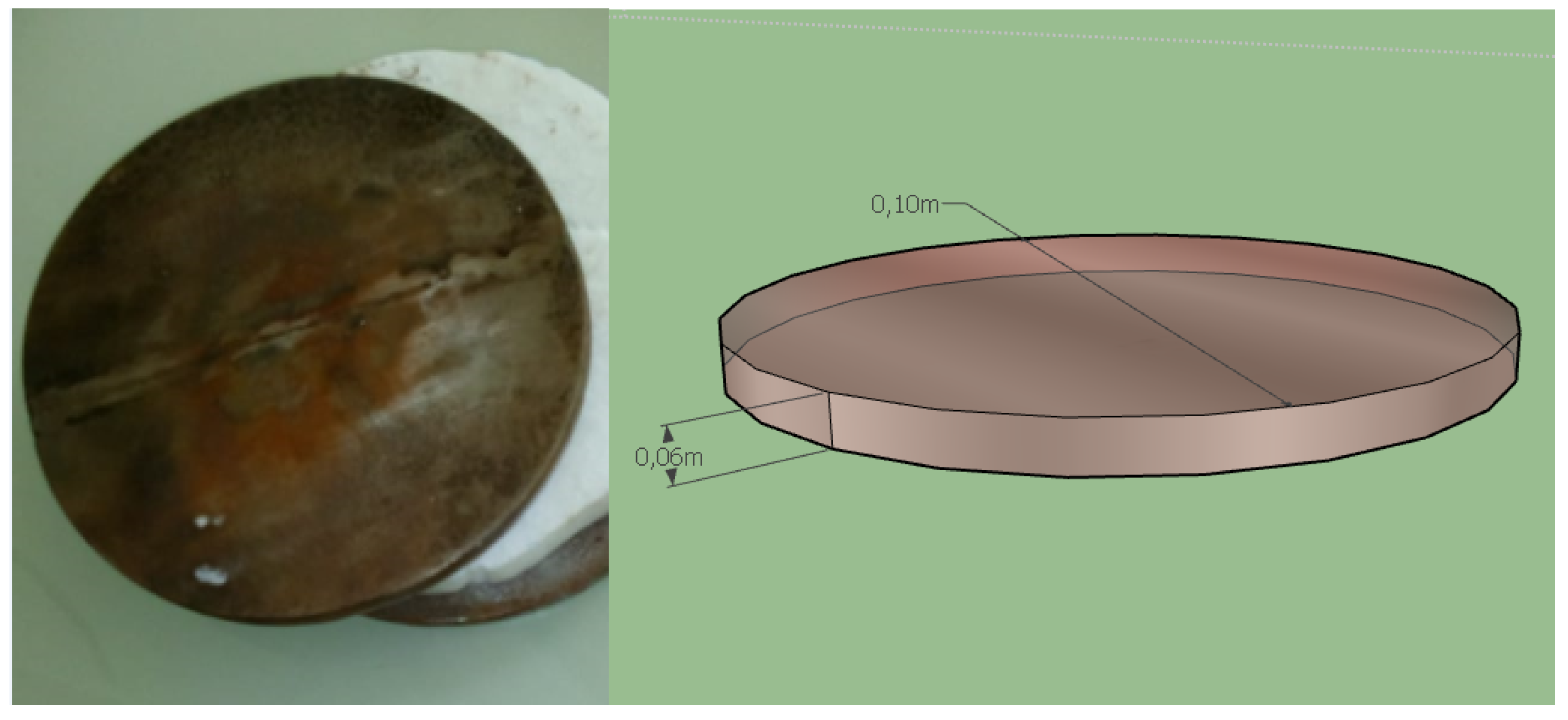

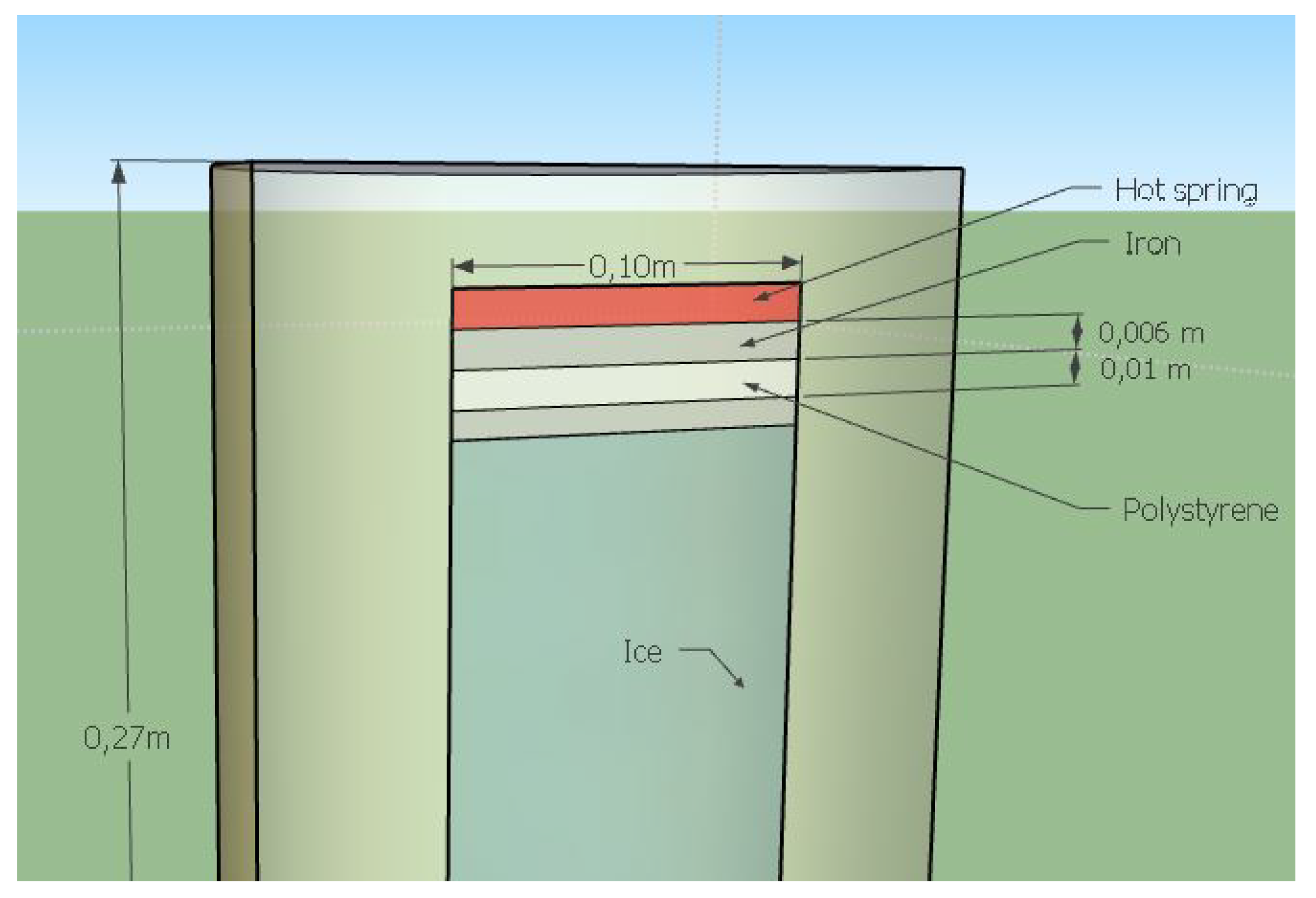

- -

- To ensure uniform thermal flux transfer across the entire surface of the test material. The sample diameter must match that of the flat steel iron (see Figure 5 for the dimension of the flat steel iron).

- -

- To accelerate the heat transfer process between the two sample surfaces in contact with the cold and hot source of the device.

- -

- To secure the sample from too high or too low temperatures from hot and cold heat sources of the device.

3.3. A Cold Source: The Ice Cubes

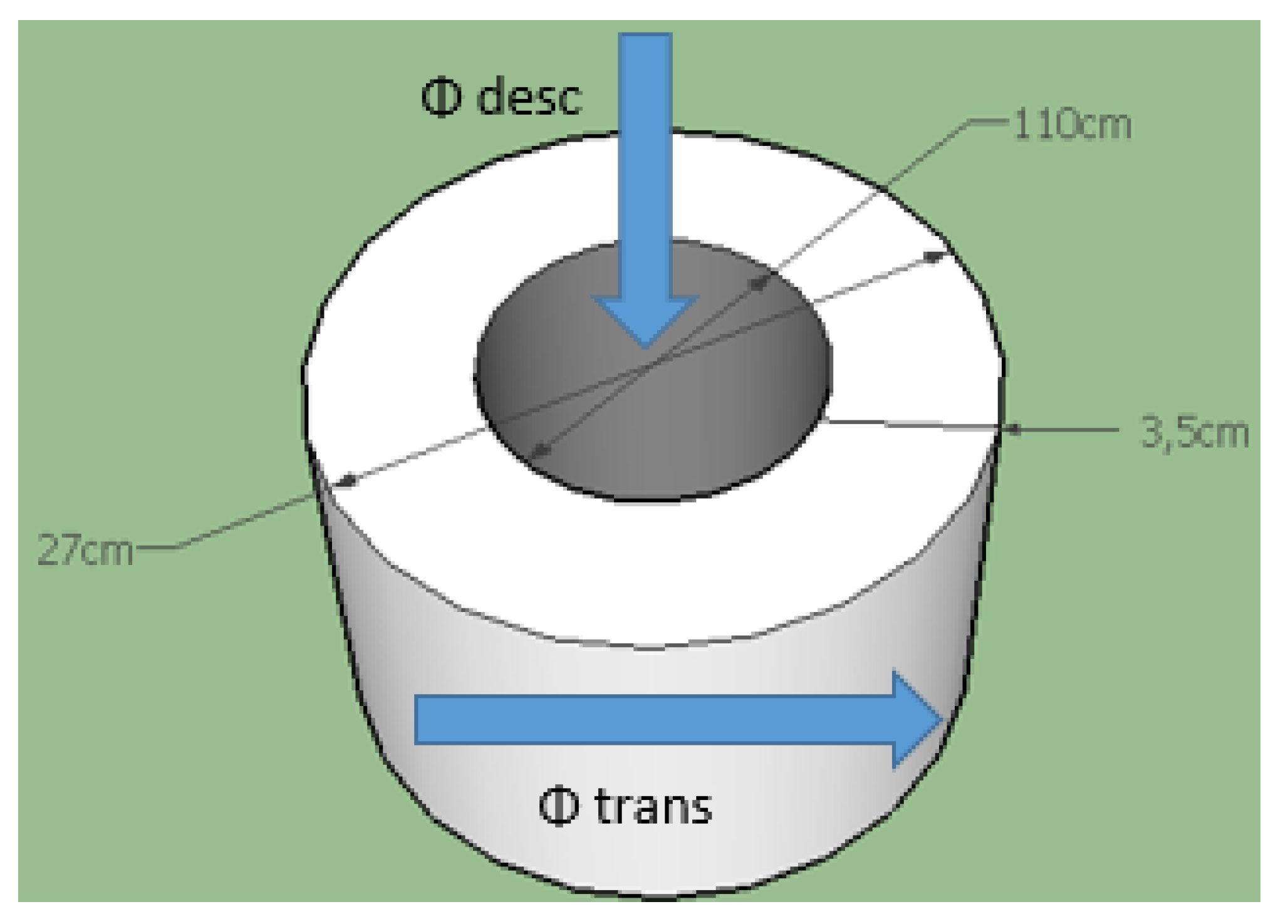

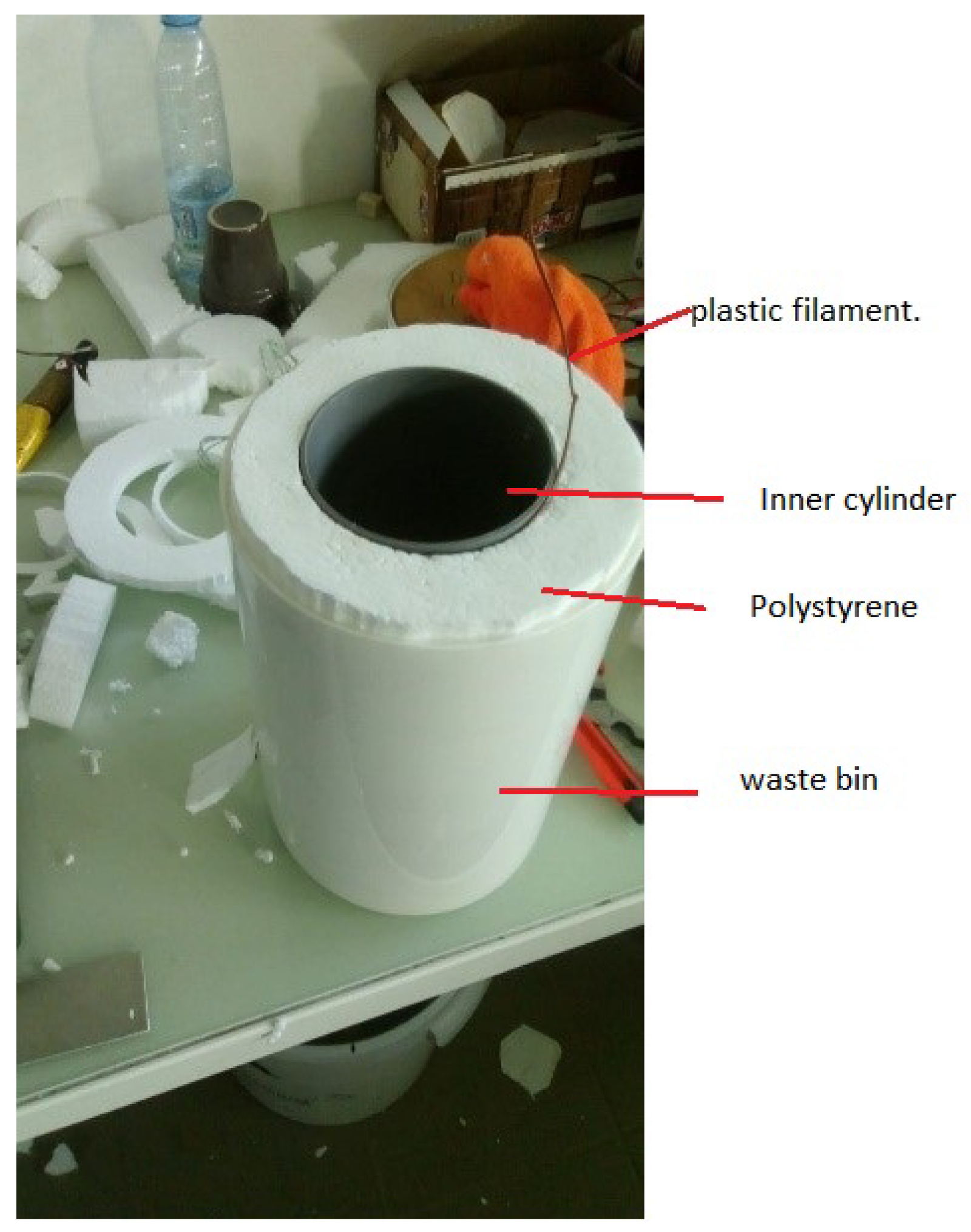

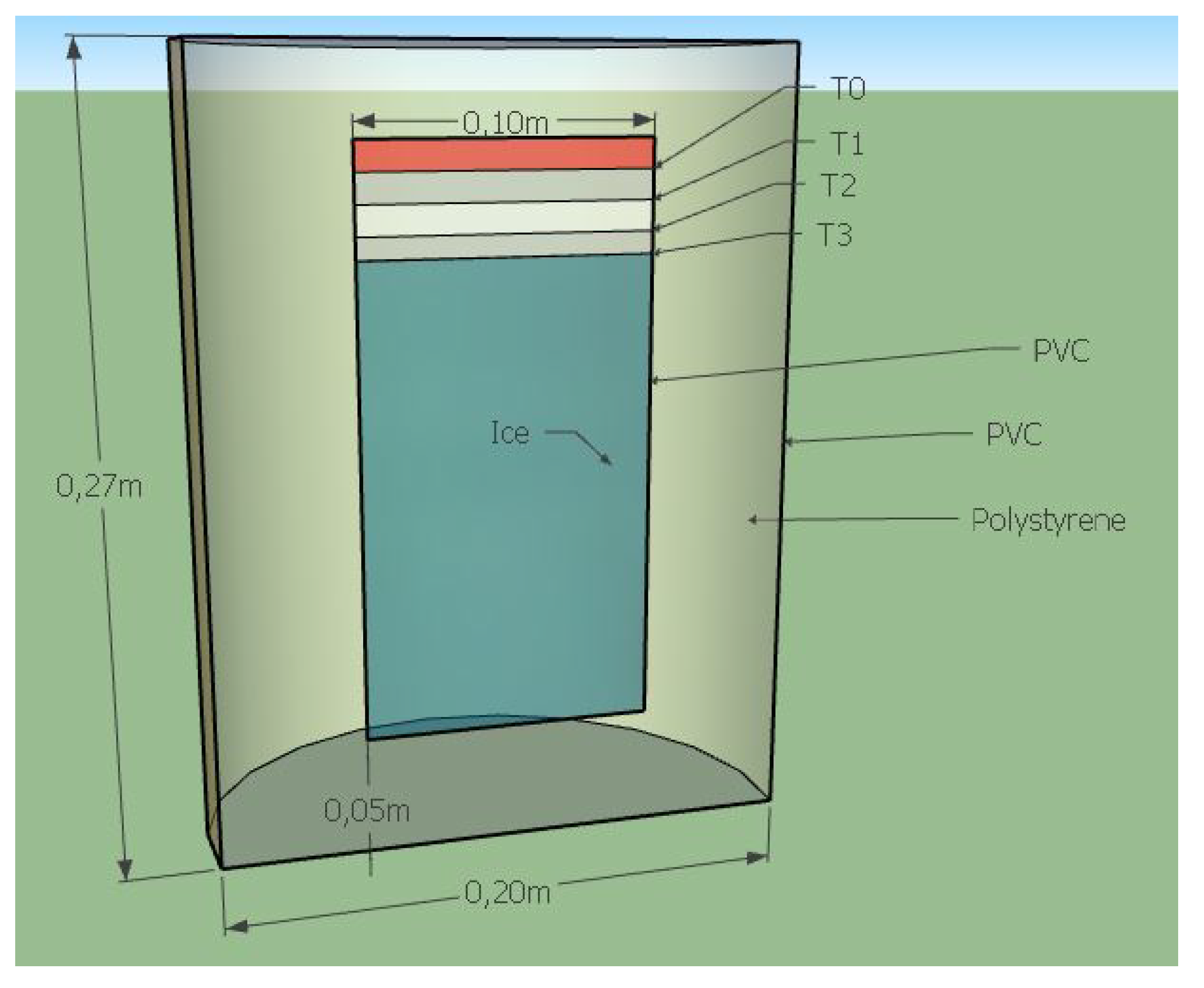

3.4. The Adiabatic Part of the Device

3.5. Calibration Tests and Measurement Protocol

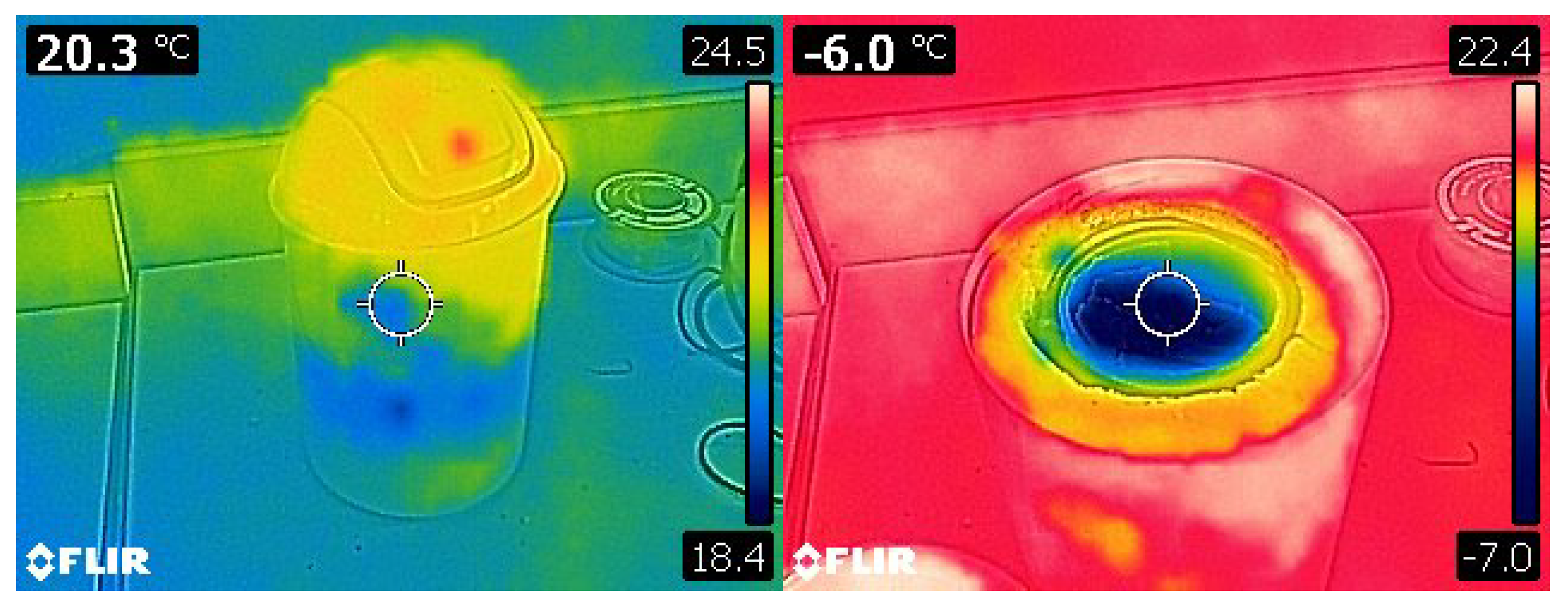

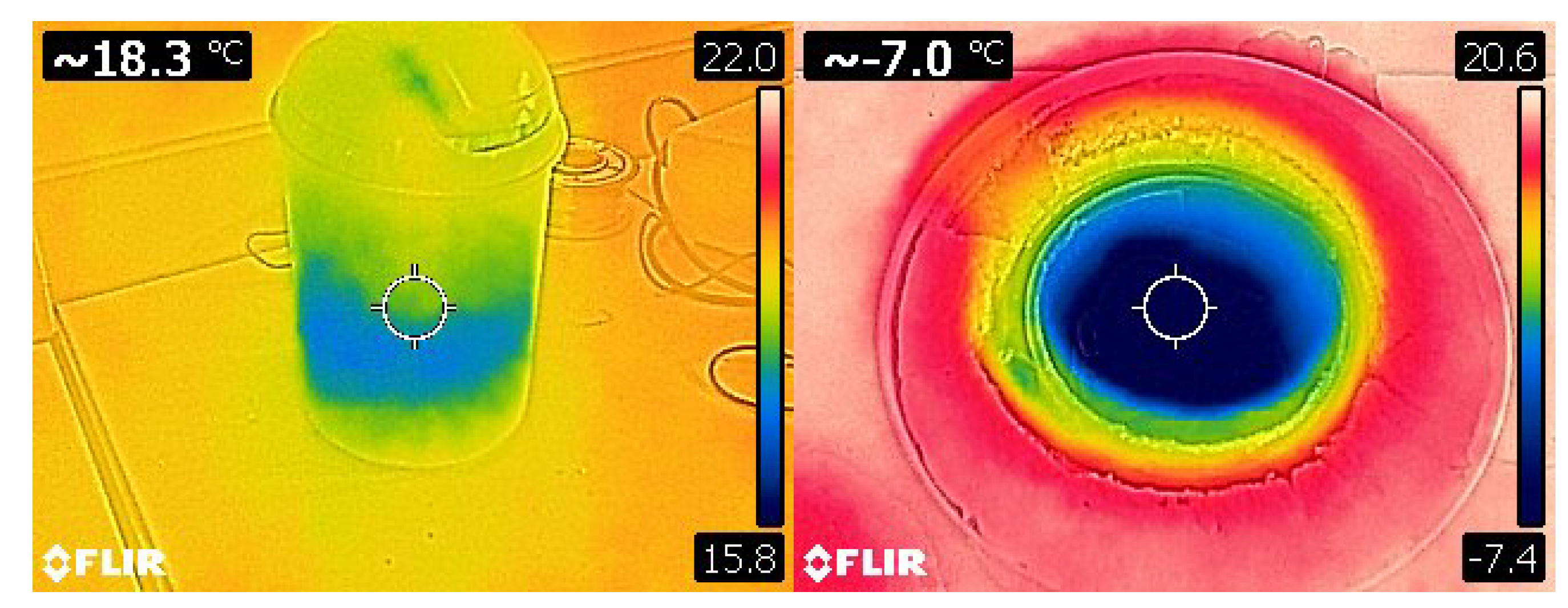

3.5.1. Cold Source Verification Test

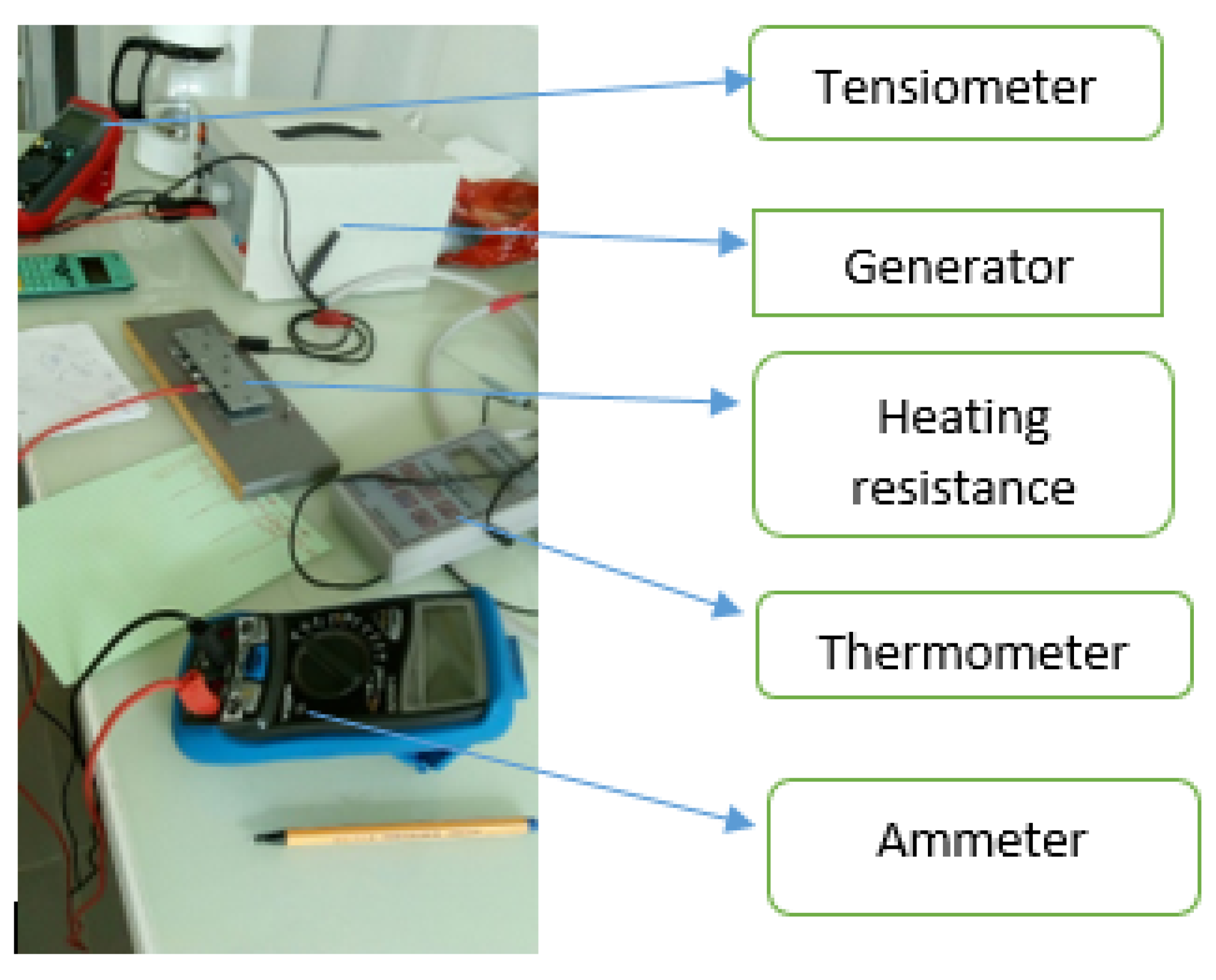

3.5.2. Hot Source Verification Test

- Determining the optimal power level that would permit heat transfer into the tested material without causing it to catch fire;

- ensuring that temperatures can be raised to 373.15 Kelvin and determining the precise power value necessary to achieve this temperature at the hot source; and

- And lastly, ensure that applying a current does not cause the iron filament to break (excessive power circulating through the filament may cause the cable to fuse). Following a series of experiments, it was determined that the ideal nominal power value is 33.9 W.

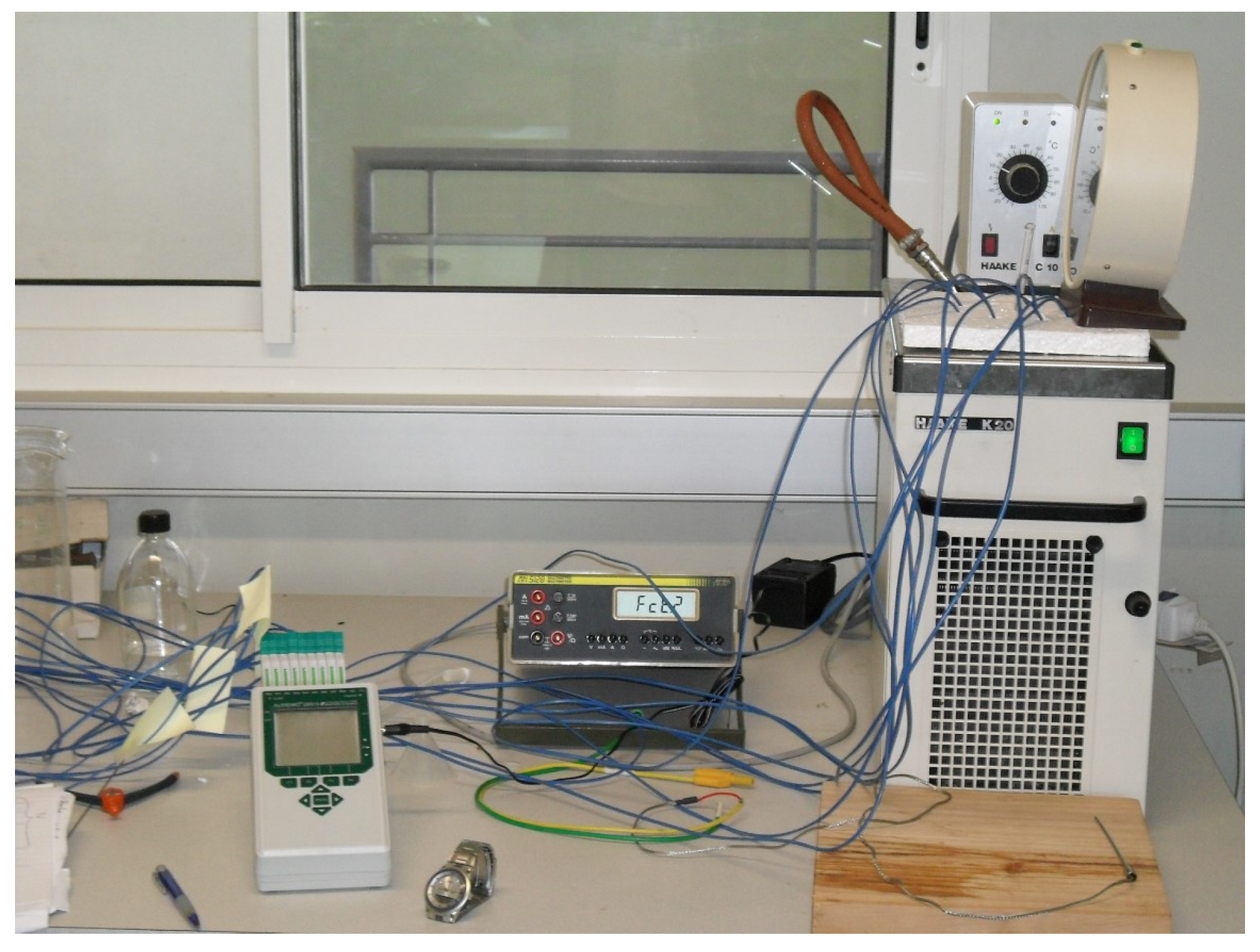

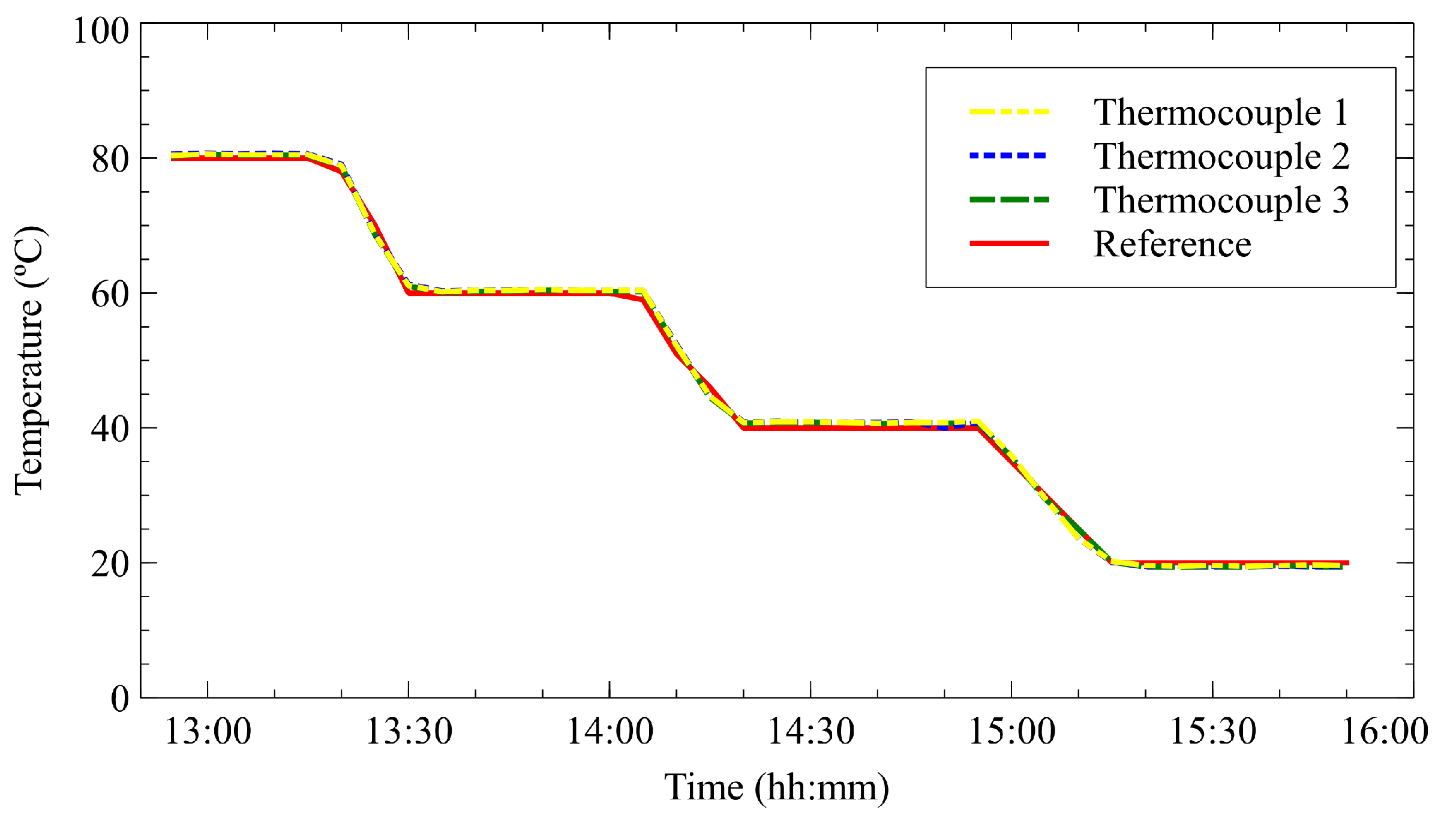

3.5.3. Thermocouple Calibrations

3.5.4. Protocol of Measurements

4. Cost Price of the Device

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Nomenclature

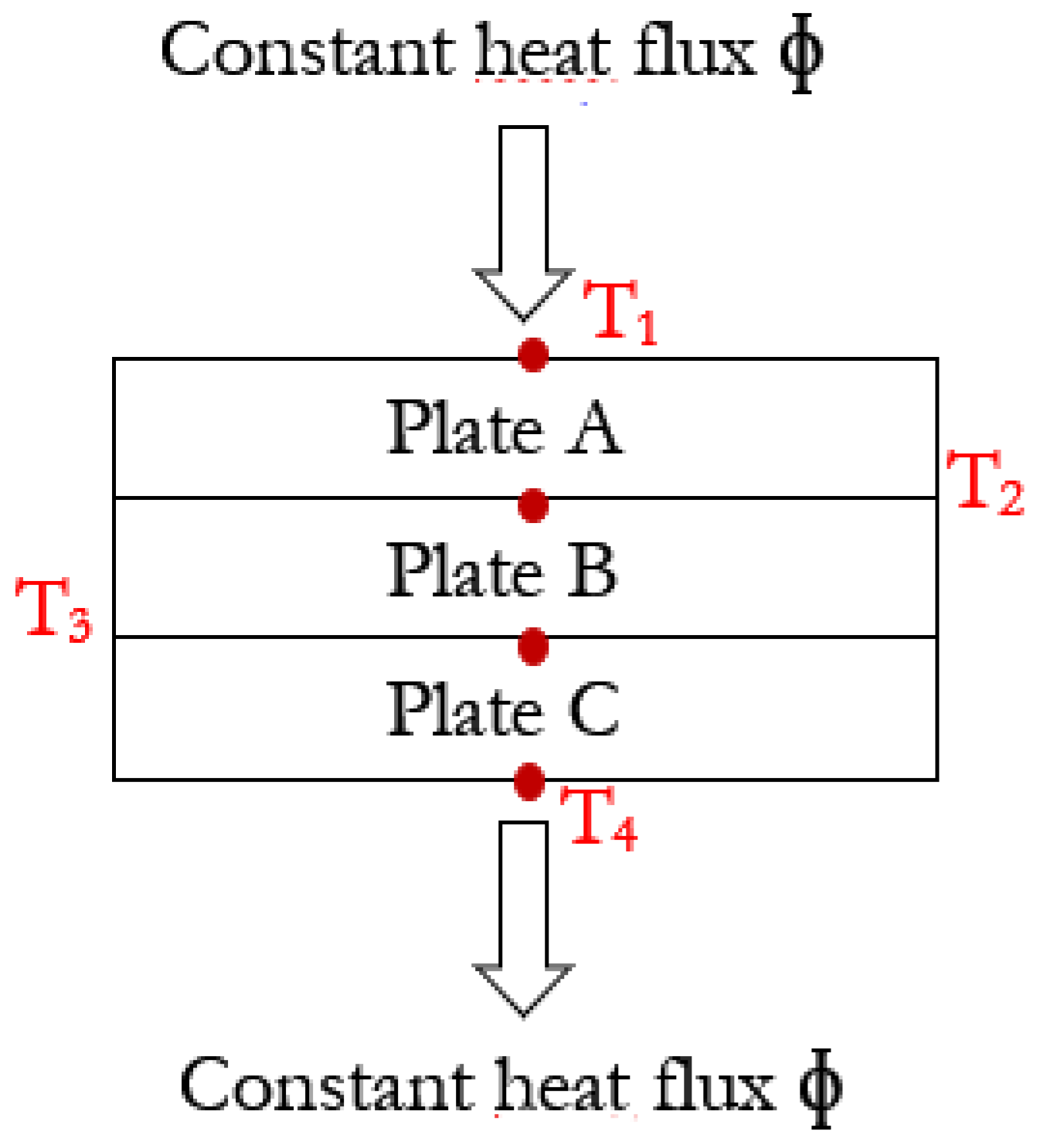

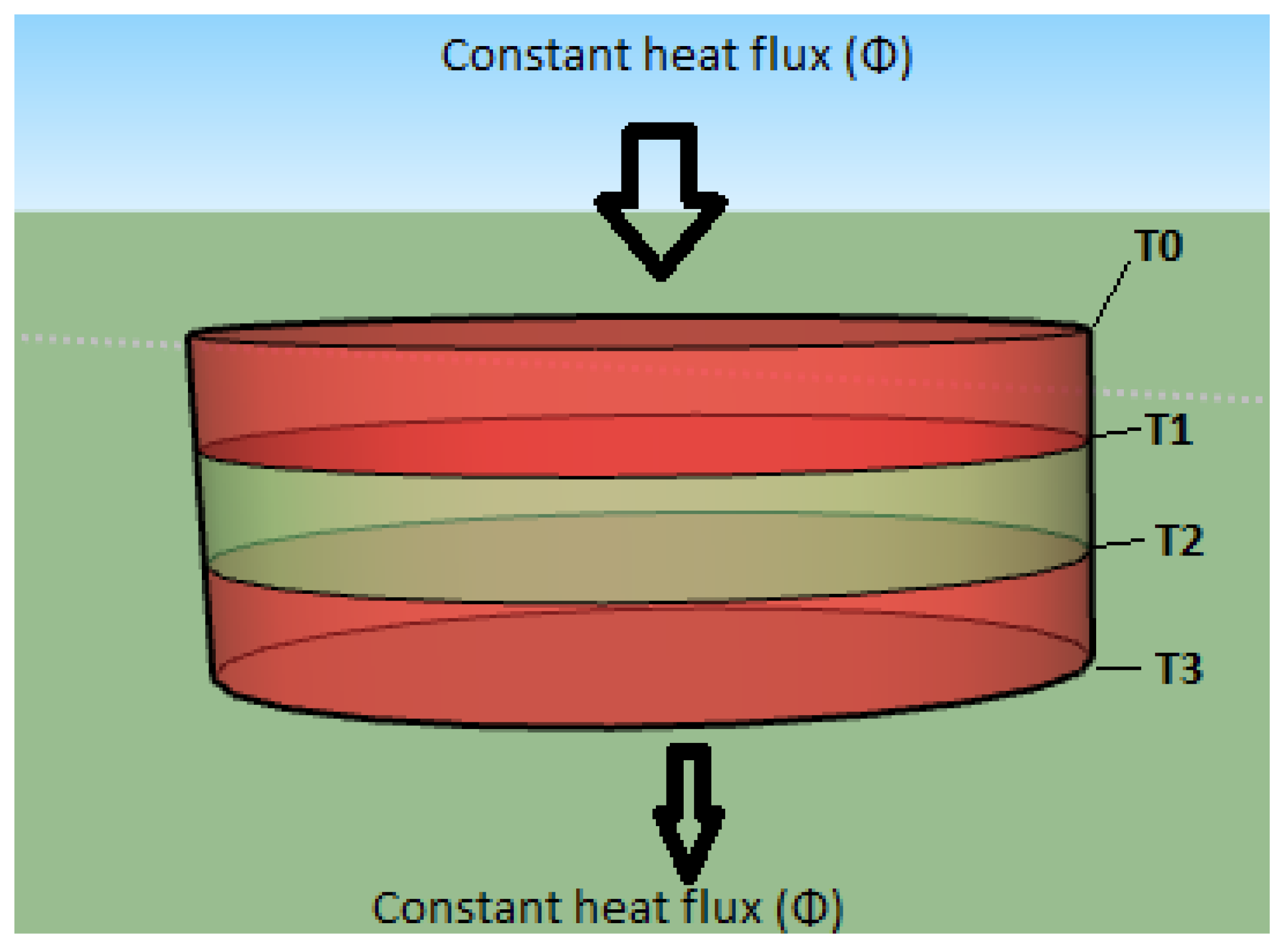

| Hot source thermocouple measurement (in K) | |

| The Thermocouple that measures the sample’s heated surface temperature (in K). | |

| The Thermocouple that measures the sample’s cooled surface temperature (in K). | |

| Cold source thermocouple measurement (in K). | |

| Surface temperature of any material (in K). | |

| Constant thermal flux crossing an opaque wall (in W). | |

| Downward thermal flux through the experimental setup (in W). | |

| Thermal flux passing horizontally through the experimental setup (in W). | |

| e | Thickness of any material described in the Table 2 (in m). |

| dia | diameter of any material described in the Table 2 (in m). |

| Surface of the plate steel iron (in ). | |

| Surface of the sample study (in ) . | |

| Thickness of the plate steel iron (in m). | |

| Thickness of the sample study (in m). | |

| Plate A | Top plate steel iron (-). |

| Plate B | the sample plate study (-). |

| Plate C | Bottom plate steel iron (-). |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials. |

| TPS | Transient Plane Source measurement method. |

| HFM | "Hot Flow Meter" Method for measuring the thermal conductivity of a material (-). |

| GHF | "Guarded Heat Flow" Method for measuring the thermal conductivity of a material (-). |

| GHP | "Guarded Hot Plate" Method for measuring the thermal conductivity of a material (-). |

| GHB | "Guarded Hot Box" Method for measuring the thermal conductivity of a material (-). |

| IRT | "Infrared Thermography" Method for measuring the thermal conductivity of a material (-). |

| SHB | "Surface Heat Balance" Method for measuring the thermal conductivity of a material (-). |

| TBM | "Temperature Based Method" for measuring the thermal conductivity of a material (-). |

| TCB | "Transient-Cylinder Bridge" Method for measuring the thermal conductivity of a material (-). |

| P | Power delivered by the generator (in W). |

| U | Voltage delivered by the generator (in V). |

| I | Intensity delivered by the generator (in A). |

| Phase angle between current and voltage (in °). | |

| Thermal conductivity of the experimental sample measuring in the device (in ). | |

| Thermal conductivity reference of the sample giving by the manufacturer (in ). |

Appendix A. Specifications thermostat RE104

| RE104 | ||

| Operating temperature range | ° C | -10 to 120 |

| Ambient temperature range | ° C | 5 ... 40 |

| Setting resolution | ° C | 0.1 |

| Indication resolution | ° C | 0.1 |

| Heater power 230 V; 50/ 60 Hz | kw | 1.5 |

| Heater power 115 V; 60 Hz | 1.3 | |

| Heater power 100 V; 50/60 Hz | 1.0 | |

| Pump type | pressure pump with choice of 5 output steps | |

| Max. discharge pressure | bar | 0.4 |

| Max. flow rate | l/mm | 17 |

| Pump Connections | mm | nipples 13 mm dia. |

| Max. bath volume | l | 3 to 4.5 |

| Bath opening (W x D) | mm | 130 x 105 |

| Bath depth | mm | 160 |

| Usable depth | mm | 140 |

| Height top edge of bath | mm | 363 |

| Overall size (W x D x H) | mm | 180 x 320 x 254 |

| Weight | kg | 21 |

| Power consumption 230 V; 50/ 60Hz | KW | 1.7 |

| Power consumption 115 V; 60 Hz | 1.4 | |

| Power consumption 100 V; 50/60 Hz | 1.1 | |

| Safety features | FL | |

| Temperature Control | ±° C | 0.05 |

Appendix B. Specifications Datalogger CR3000

| Specifications CR3000 | |

| -NOTE- | Note: Additional specifications are listed in the CR3000 Specifications Sheet. |

| Operating Temperature Range | -25° to +50° C (standard)-40° to +85°C (extended)Non-condensing environment |

| The rechargeable base option has an operating temperature range of -40° to +60°C. | |

| The alkaline base option has a temperature range of -25° to +50°C. | |

| 25° to +50°C (standard)-40° to +85°C (extended) | |

| Analog Inputs | 28 single-ended or 14 differential (individually configured) |

| Pulse Counters | 4 |

| Voltage Excitation Terminals | 4 (VX1 to VX4) |

| Communications Ports | CS I/O |

| RS-232 | |

| Parallel peripheral | |

| Switched 12 Volt | 2 terminals |

| Digital I/O | Certain digital ports can be used to count switch closures. |

| 3 SDM and 8 I/Os or 4 RS-232 COM I/O | |

| Input Limits | ±5 Vdc |

| Analog Voltage Accuracy | ± (0.04 % of reading + offset) at 0°to 40° C |

| ADC | 16-bit |

| Power Requirements | 10 to 16 Vdc |

| Real-Time Clock Accuracy | ±3 min. per year (Correction via GPS optional.) |

| Internet Protocols | FTP, HTTP, XML POP3, SMTP, Telnet, NTCIP, NTP, |

| Communication Protocols | PakBus, Modbus, DNP3, SDI-12, SDM |

| Warranty | 3 years |

| Idle Current Drain, Average | 2 mA (@ 12 Vdc) |

| Active Current Drain, Average | 3 mA (1 Hz sample rate @ 12 Vdc without RS-232 communication) |

| 10 mA (100 Hz sample rate @ 12 Vdc without RS-232 communication) | |

| 38 mA (100 Hz sample rate @ 12 Vdc with RS-232 communication) | |

References

- Asadi, I.; Shafigh, P.; Hassan, Z.F.B.A.; Mahyuddin, N.B. Thermal conductivity of concrete–A review. Journal of Building Engineering 2018, 20, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.G.; Flores-Colen, I.; Da Silva, F.; Pedroso, M. Thermal conductivity measurement of thermal insulating mortars with EPS and silica aerogel by steady-state and transient methods. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 172, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudenne, A.; Ibos, L.; Gehin, E.; Candau, Y. A simultaneous characterization of thermal conductivity and diffusivity of polymer materials by a periodic method. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2003, 37, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Ma, A.; Li, Y. Transient hot strip measures thermal conductivity of organic foam thermal insulation materials. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 2018, 91, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaratto, P.G.; De Carli, M. A measuring campaign of thermal conductance in situ and possible impacts on net energy demand in buildings. Energy and Buildings 2013, 59, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, E.; Cuce, P.M.; Guclu, T.; Besir, A.; Gokce, E.; Serencam, U. A novel method based on thermal conductivity for material identification in scrap industry: An experimental validation. Measurement 2018, 127, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Jeon, S.E.; Kim, J.K.; Yang, S. An experimental study on thermal conductivity of concrete. Cement and concrete research 2003, 33, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Guo, L.; Zhong, L.; Zhu, Y. Thermal conductivity and heat transfer coefficient of concrete. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2011, 26, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desogus, G.; Mura, S.; Ricciu, R. Comparing different approaches to in situ measurement of building components thermal resistance. Energy and Buildings 2011, 43, 2613–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Maslehuddin, M.; Al-Hadhrami, L.M. In situ measurement of thermal transmittance and thermal resistance of hollow reinforced precast concrete walls. Energy and Buildings 2014, 84, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaratto, P.G.; De Carli, M.; Marinetti, S. Effect of different parameters on the in situ thermal conductance evaluation. Energy and buildings 2011, 43, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asdrubali, F.; Baldinelli, G. Thermal transmittance measurements with the hot box method: Calibration, experimental procedures, and uncertainty analyses of three different approaches. Energy and buildings 2011, 43, 1618–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, L.; Yin, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zheng, L. An in-situ test apparatus of heat transfer coefficient for building envelope. Building Energy Efficient 2012, 256, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Albatici, R.; Tonelli, A.M.; Chiogna, M. A comprehensive experimental approach for the validation of quantitative infrared thermography in the evaluation of building thermal transmittance. Applied energy 2015, 141, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokaides, P.A.; Kalogirou, S.A. Application of infrared thermography for the determination of the overall heat transfer coefficient (U-Value) in building envelopes. Applied energy 2011, 88, 4358–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, E.; Almeida, R.; Delgado, J. Infrared thermography for assessing moisture related phenomena in building components. Construction and building materials 2016, 110, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelisti, L.; Guattari, C.; Gori, P.; De Lieto Vollaro, R. In situ thermal transmittance measurements for investigating differences between wall models and actual building performance. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10388–10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, I.; Ambrosini, D.; de Rubeis, T.; Sfarra, S.; Perilli, S.; Pasqualoni, G. A comparison between thermographic and flow-meter methods for the evaluation of thermal transmittance of different wall constructions. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing; 2015; Vol. 655, p. 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, I.; Paoletti, D.; Ambrosini, D.; De Rubeis, T.; Sfarra, S. U-value assessment by infrared thermography: A comparison of different calculation methods in a Guarded Hot Box. Energy and Buildings 2016, 122, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavaš, H.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Haničar Buljan, I.; Barić, T. Locating hidden elements in walls of cultural heritage buildings by using infrared thermography. Buildings 2019, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelisti, L.; Scorza, A.; De Lieto Vollaro, R.; Sciuto, S.A. Comparison between heat flow meter (HFM) and thermometric (THM) method for building wall thermal characterization: latest advances and critical review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, N. The Review of Some Commonly Used Methods and Techniques to Measure the Thermal Conductivity of Insulation Materials. In Insulation Materials in Context of Sustainability; IntechOpen, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Rausch, M.H.; Krzeminski, K.; Leipertz, A.; Fröba, A.P. A new guarded parallel-plate instrument for the measurement of the thermal conductivity of fluids and solids. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2013, 58, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wittkopf, S.K. Summer condition thermal transmittance measurement of fenestration systems using calorimetric hot box. Energy and Buildings 2012, 53, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, B.; Zhang, W.; Long, E. Feasibility experiment on the simple hot box-heat flow meter method and the optimization based on simulation reproduction. Applied Thermal Engineering 2015, 83, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Luo, T.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shen, Q.; Long, E. A new simple method to measure wall thermal transmittance in situ and its adaptability analysis. Applied Thermal Engineering 2017, 122, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaze, O.; Khanna, S. Experimental Thermal Conductivity Measurement of Hollow-Structured Polypropylene Material by DTC-25 and Hot Box Test. Buildings 2023, 13, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpińska, M.; Karwacki, J.; Maurin, A.; Kin, M. Measurements of thermal conductivity of LWC cement composites using simplified laboratory scale method. Materials 2021, 14, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobaraki, B.; Komarizadehasl, S.; Castilla Pascual, F.J.; Lozano-Galant, J.A.; Porras Soriano, R. A novel data acquisition system for obtaining thermal parameters of building envelopes. Buildings 2022, 12, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljana, S. Vučićević, Valentina M. Turanjanin, V.V.B.M.P.J.S. Experimental and numerical modeling of thermal performance of a residential building in belgrade. Thermal Science 2009, 13, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andargie, M.S.; Azar, E. An applied framework to evaluate the impact of indoor office environmental factors on occupants’ comfort and working conditions. Sustainable cities and society 2019, 46, 101447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelisti, L.; Guattari, C.; Gori, P.; de Lieto Vollaro, R.; Asdrubali, F. Experimental investigation of the influence of convective and radiative heat transfers on thermal transmittance measurements. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer 2016, 78, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, A.; Thiele, A.M.; Falzone, G.; Sant, G.; Pilon, L. Thermal conductivity of cementitious composites containing microencapsulated phase change materials. International journal of heat and mass transfer 2017, 104, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E.; Roberti, F.; Alexandra, T. Definition of an experimental procedure with the hot box method for the thermal performance evaluation of inhomogeneous walls. Energy and Buildings 2018, 179, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, A.; Cascone, S. Eco-friendly green roof solutions: Investigating volcanic ash as a viable alternative to traditional substrates. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 411, 134442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, E.; Cuce, P.M.; Guclu, T.; Besir, A.; Gokce, E.; Serencam, U. A novel method based on thermal conductivity for material identification in scrap industry: An experimental validation. Measurement 2018, 127, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Ma, A.; Li, Y. Transient hot strip measures thermal conductivity of organic foam thermal insulation materials. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 2018, 91, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.G.; Flores-Colen, I.; da Silva, F.; Pedroso, M. Thermal conductivity measurement of thermal insulating mortars with EPS and silica aerogel by steady-state and transient methods. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 172, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudenne, A.; Ibos, L.; Géhin, E.; Candau, Y. A simultaneous characterization of thermal conductivity and diffusivity of polymer materials by a periodic method. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2003, 37, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, N. Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Engineering, H. F. Mark, N. M. Bikales, C. G. Overberger, and G. Menges, Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1985, 720 pp. Journal of Polymer Science Part C: Polymer Letters 1986, 24, 359–360, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/pol.1986.140240720]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottram. ; Taylor. Thermal transport properties. international encyclopaedia of composity 1989, 127, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakra, D.A.H.; José, B.R.A.; Murad, N.M.; Gatina, J.C. A new affordable and quick experimental device for measuring the thermo-optical properties of translucent construction materials. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 32, 101708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakra, D.A.H.; José, B.R.A.; Murad, N.M.; Randriantsoa, A.N.A.; Gatina, J.C. Experimental data and calibration processes to a new and simple device dedicated to the thermo-optical properties of a polycarbonate construction material. Data in Brief 2020, 32, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delort, M.; Fakra, D.; Malet-Damour, B.; Gatina, J.C. Measuring the uncertainty assessment of an experimental device used to determine the thermo-optico-physical properties of translucent construction materials. Measurement Science and Technology 2022, 33, 055007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Thermal Conductivity of Solids by Means of the Guarded-Comparative-Longitudinal Heat Flow Technique. Technical report ASTM E1225-13, American Society for Testing and Materials, 2013. 8 pp.

| The results of the Test (maximum power) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensities (A) | Voltages (V) | Temperature (K) | Power (W) | |

| 1 | 6 | 2.16 | 335.15 | 12.96 |

| 2 | 7.77 | 3 | 364.15 | 23.31 |

| 3 | 8.7 | 3.9 | 373.15 | 33.93 |

| Dimensions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Designation | Q | e (m) | dia (m) | Unit cost () | Total cost () |

| 1 | Generator | 1 | 63 | 63 | ||

| 2 | Steel wool | 1 | 0.50 | 0.50 | ||

| 3 | Thermocouple | 4 | 0.018 | 0.1 | 4.20 | 16.80 |

| 4 | Black flat steel iron | 2 | 0.006 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Polystyrene (sample) | 1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Small waste bin | 1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | Ice | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 8 | recycled Polystyrene (Isolation) | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 9 | Tube PVC | 1 | 0.002 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | Plug PVC | 1 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 11 | 11 |

| Total | 94.30 | |||||

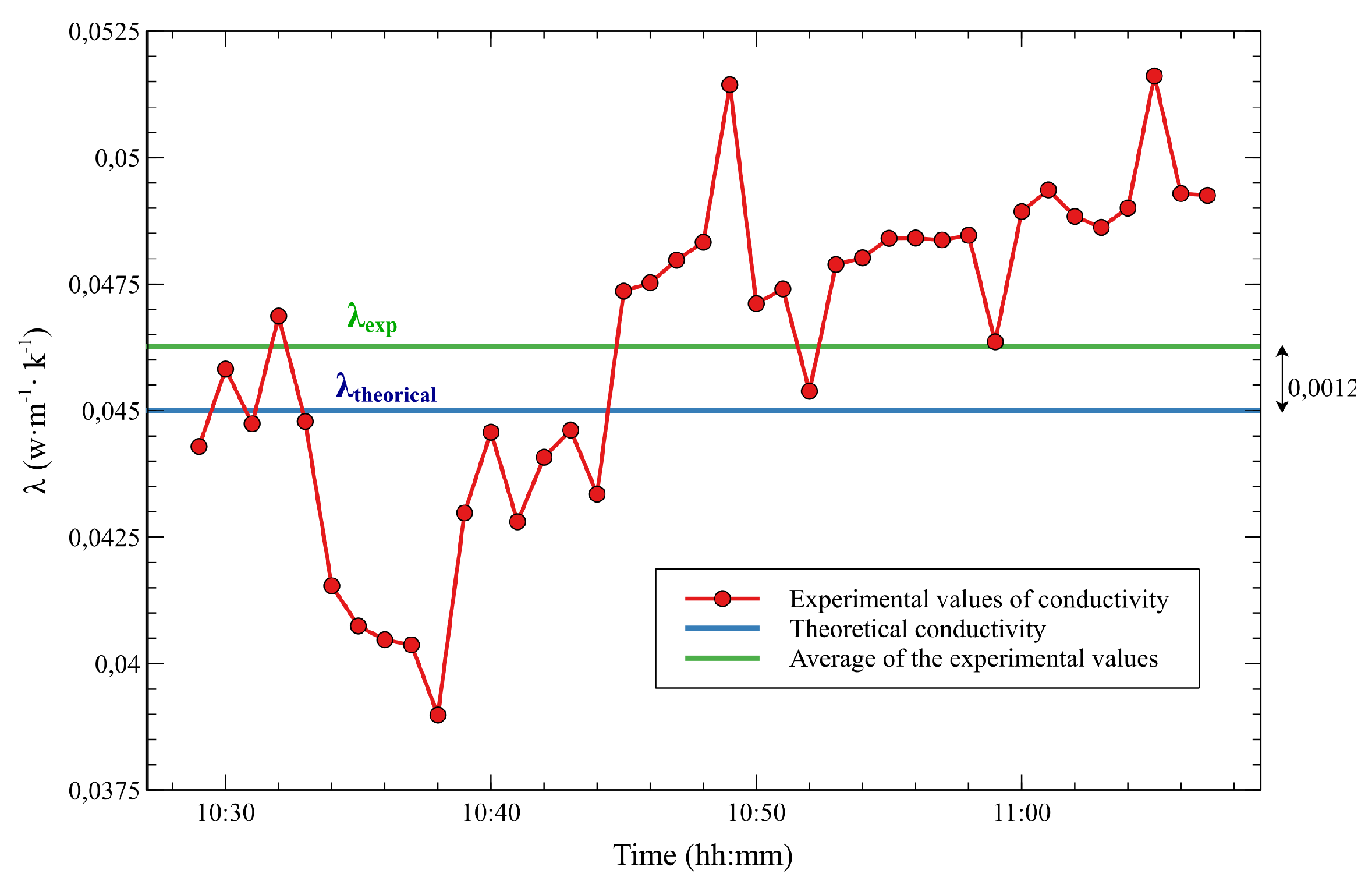

| Type of materials | Relative error | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hard foam | 0.16 | 0.155 | 3.13 % |

| Polystyrene | 0.045 | 0.0468 | 4 % |

| Chipboard wood | 0.12 | 0.117 | 2.5 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).