Submitted:

27 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

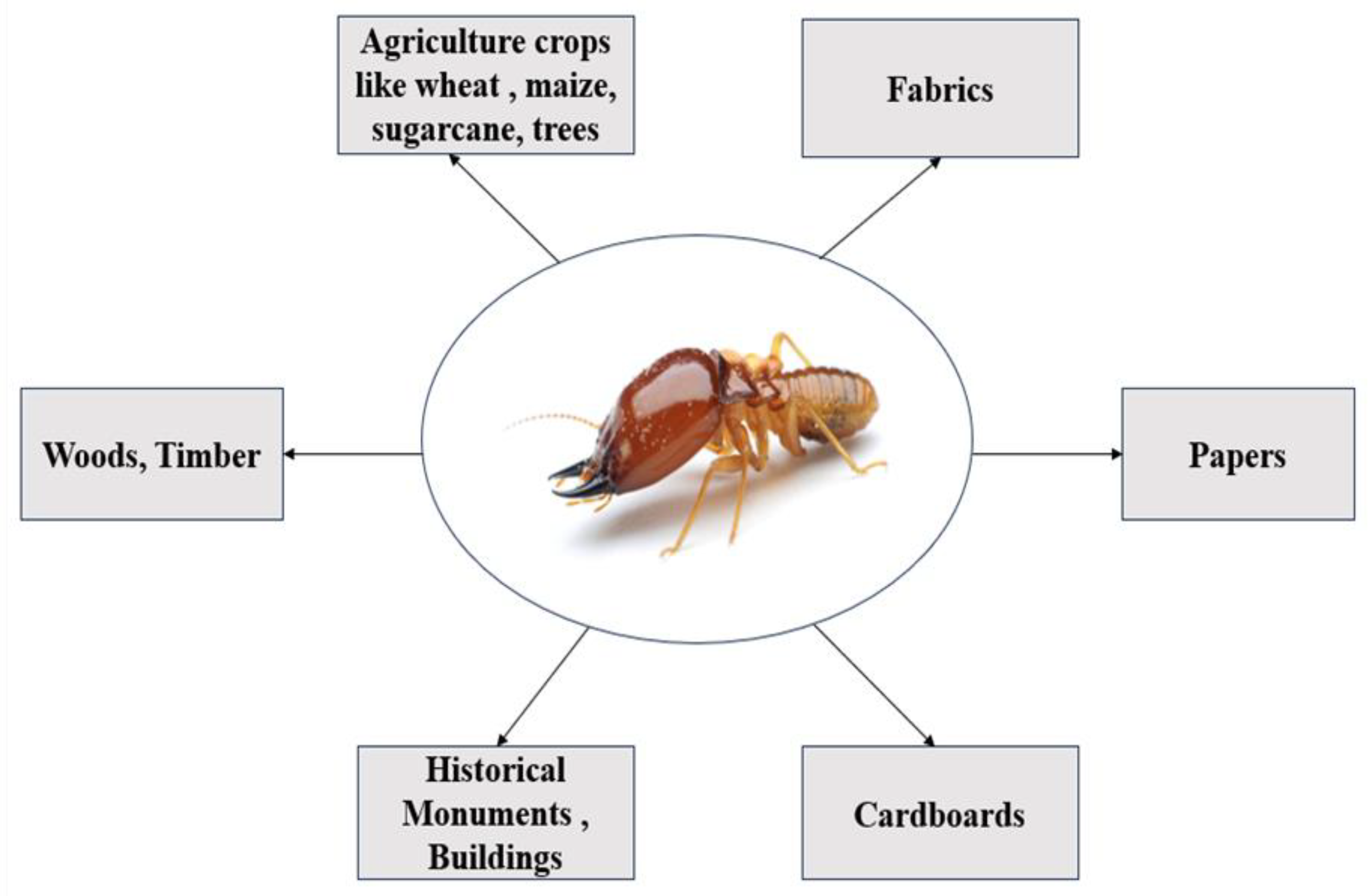

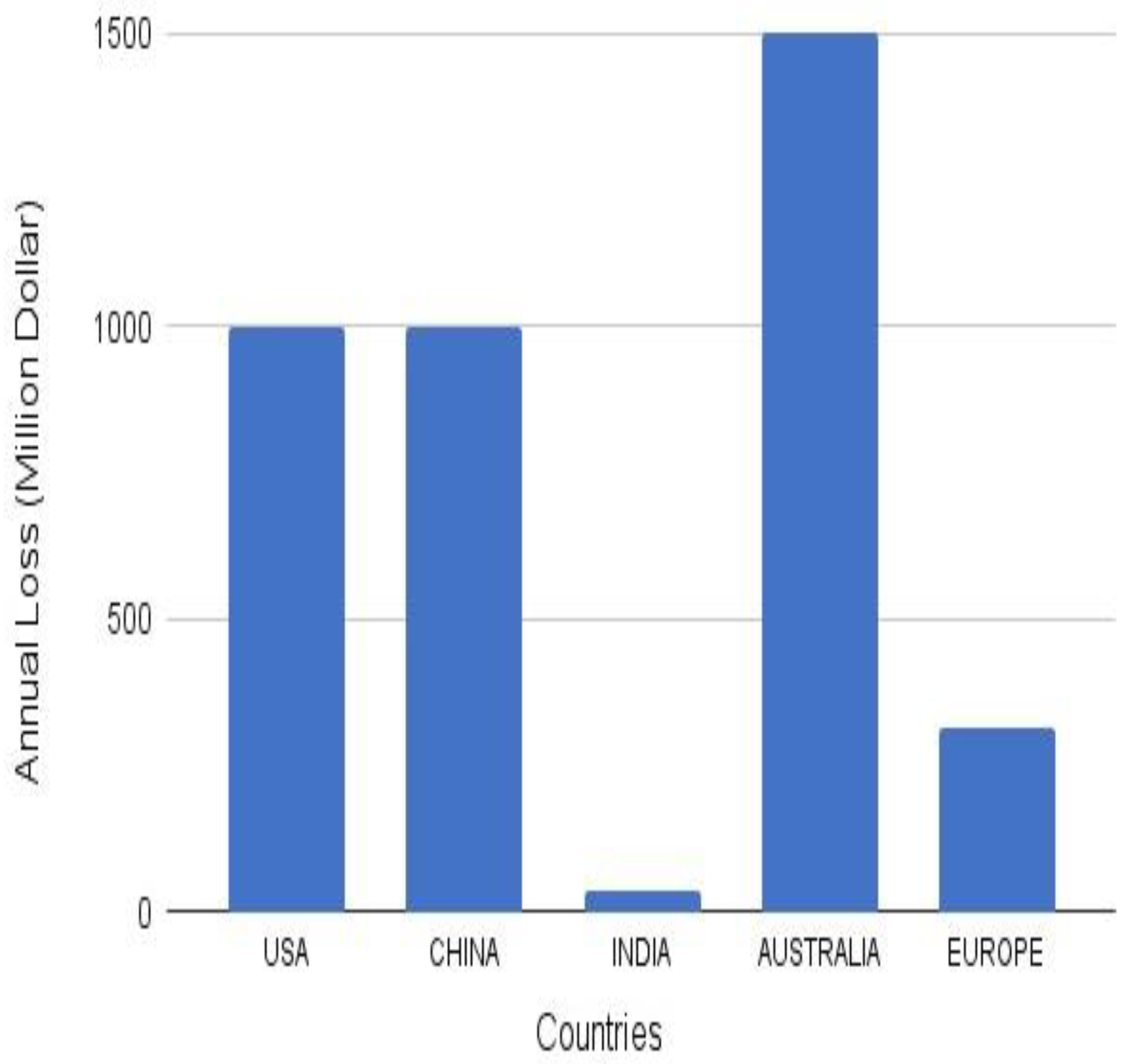

2. Termites as a Noxious Agricultural and Industrial Economic Agent

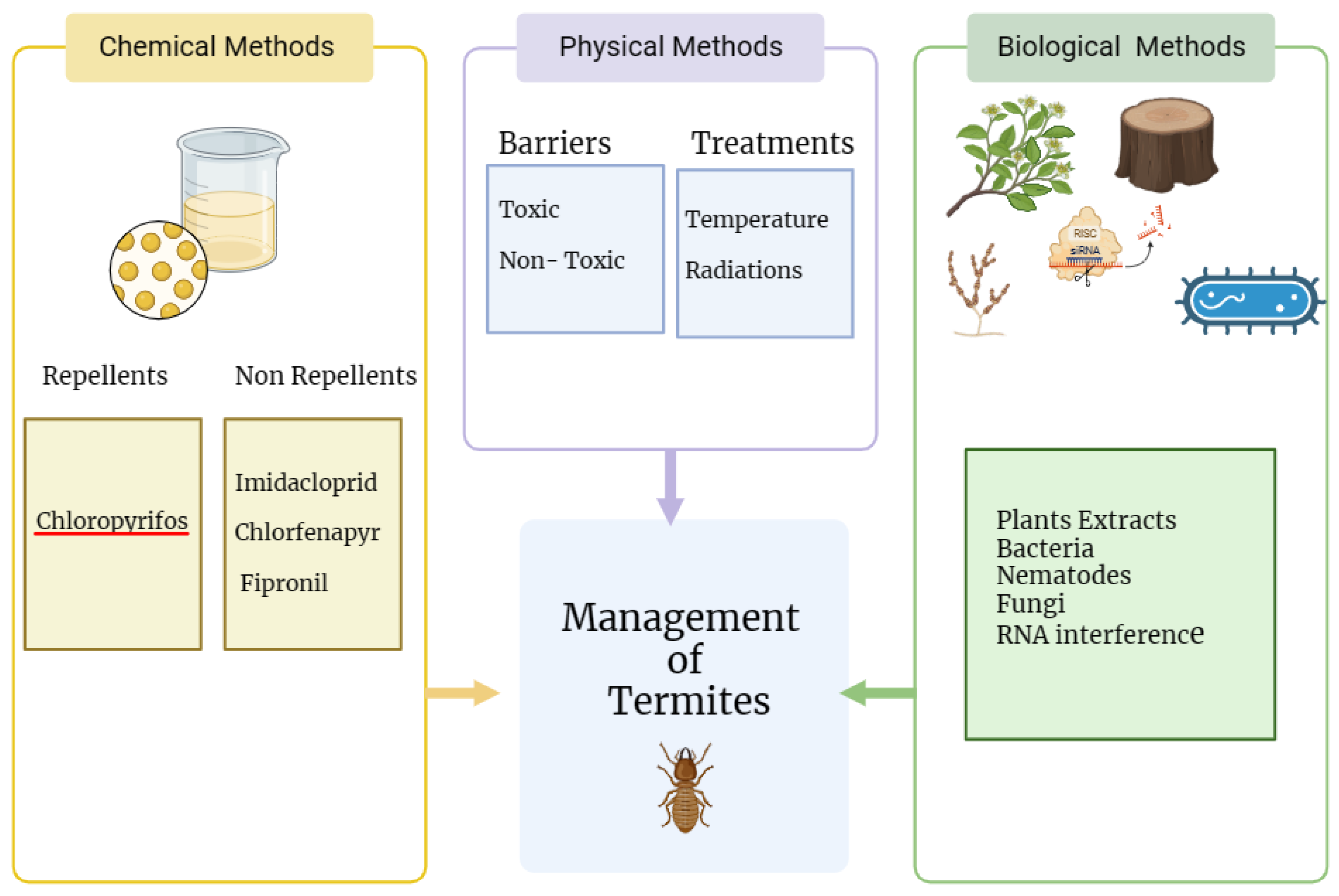

3. Management of Termites

3.1. Physical Methods

3.2 Chemical Methods

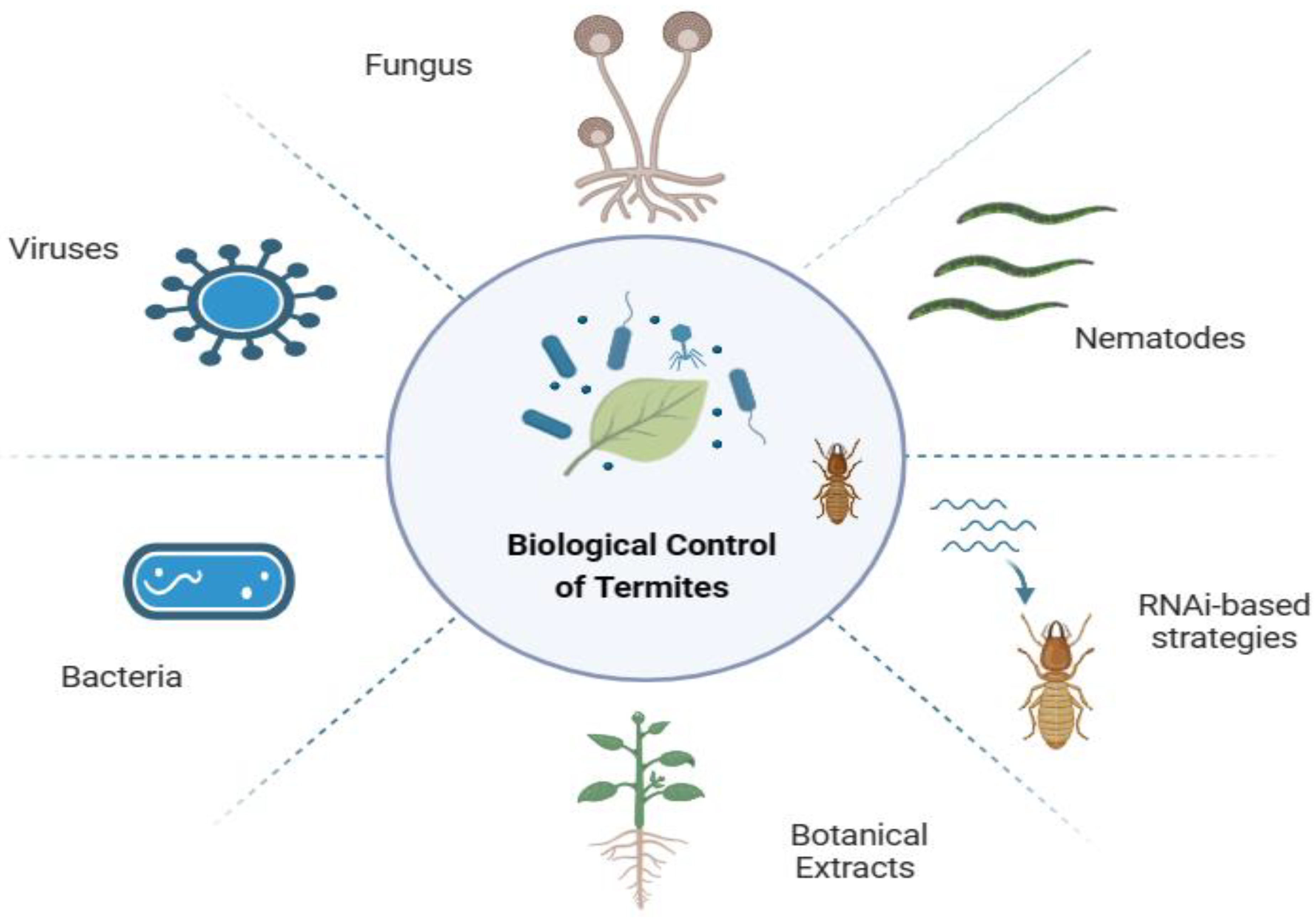

3.3. Biological Warfare Against Termites

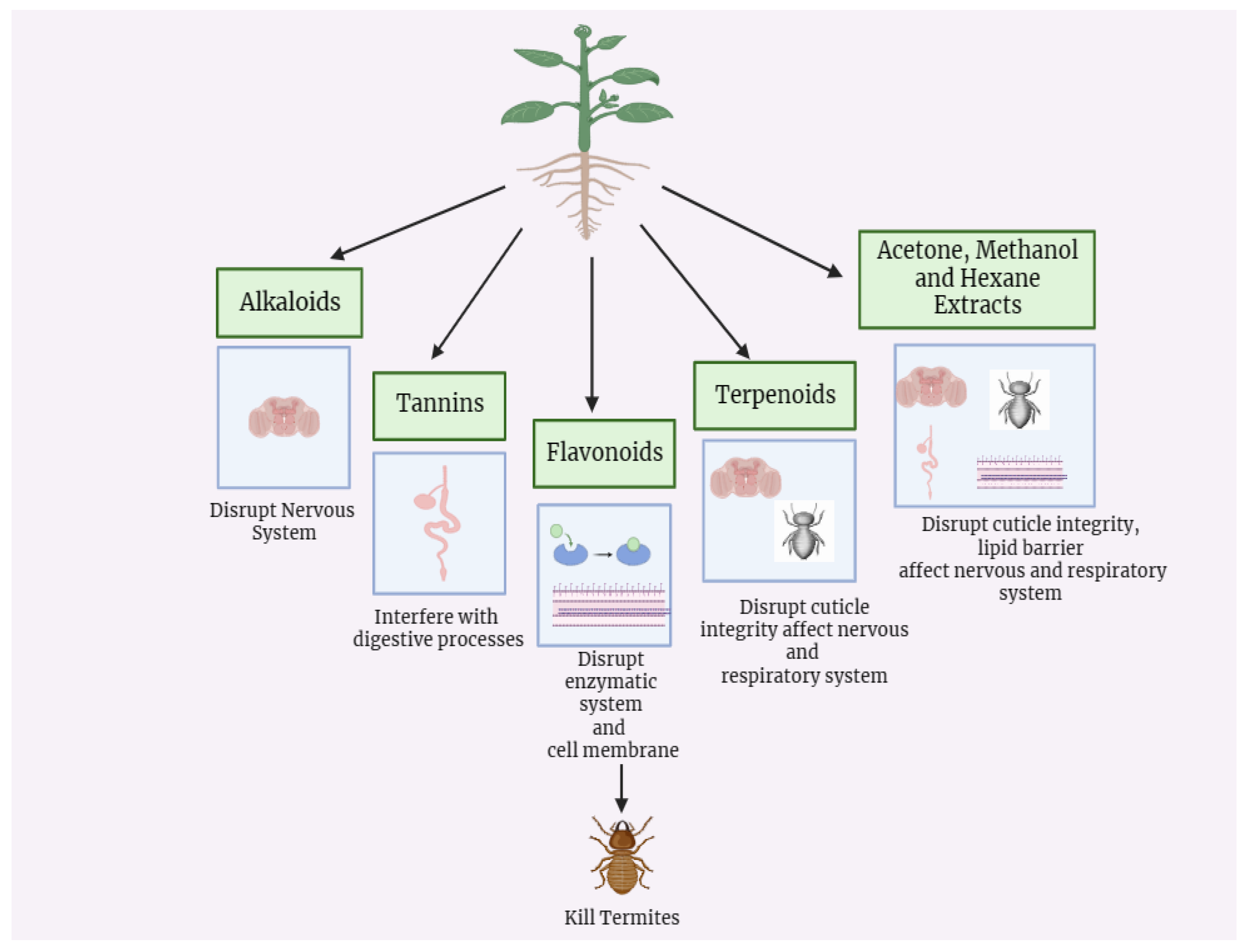

3.3.1. Plant Extracts for Termite Management

| Sr. No. | Plants Species | Parts | Active compounds | Mechanism | MortalityRate | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cymbopogon citratus | Leaves | Alkaloids, Flavonoids, Phenolics, Tannins, Saponins, Glycosides and Citrals | Disrupt cell membrane and cytoskeleton structure Cause blockage of neuromuscular junction and respiratory failure |

75% | Africa | Essien et al., 2023 |

| 2 | Dioscorea bulbifera | Leaves | Methanolic extracts | Inhibit enzymatic activity and affect the metabolism of termites | 70.97% | Indonesia | Oksari et al., 2023 |

| 3 | Rhazya stricta, Lantana camara, Ruta chalepensi and Heliotropium bacciferum | Leaves | n- hexane extracts(Ethyl ester, Octadecadienoic acid) | Disrupt nervous system Interfere with metabolic pathways | 70-76.3% | Saudi Arabia | Alshehry et al., 2014 |

| 4 | `Azadirachta excelsa | Seed Kernel | n-hexane (Hexadecanoic acid, Ethyl ester, Octadecadienoic acid) and methanolic extracts | Disrupt the growth, reproduction and hormonal regulation of termites | 80% | Indonesia | Adfa et al., 2023 |

| 5 | Lavandula latifolia, Origanum vulgare and Syzygium aromaticum | Dry Buds | Lavandula latifolia (Linalool, Lavandulol, β-terpinyl acetate) Origanum vulgare (Thymol, m-cymene, Linalool and Terpinen) Syzygium aromaticum (Eugenol) | Affect nervous system | 75% | Egypt | Salem et al., 2020 |

| 6 | Odontotermes assamensis | Oil | Eugenol, α-pinene, terpinen-4-ol and β-trans-caryophyllene | Affect nervous system and other physiological process like digestion, respiration | 70-90% | India | Pandey et al., 2012 |

| 7 | Syzygium aromaticum | Oil | Flavonoids, Glycosides, Tannins and terpenoids | Affect feeding behaviour of termites by inhibiting enzymes essential for digestion also alter smell and taste of food Blockage of neuromuscular junction | 100% | Africa | Sadiq et al., 2019 |

| 8 | Carica papaya | Leaves | Papain enzyme, Saponins, Flavonoids and Alkaloids Karpain | Proteolytic action of papain disrupt internal proteins affect digestive processes Disrupt cell membrane, leading to cell leakage, also affect nervous system | 40% | Malaysia | Zahtamal et al., 2017 |

| 9 | Eucalyptus globulus | Leaves | Ethanolic Extracts | Disrupt social organization of termite colony Also interfere with termite nervous system, digestive and respiratory processes | 90% | India | Kaundal et al., 2023 |

| 10 | Bintaro | Seeds | Quercetin | Has antioxidant activity may influence cellular processes, interfere with cell cycle | 80% | Japan | Tarmadi et al., 2014 |

| 11 | Azadirachta indica | Oil | Azadirachtin | Disrupt foraging, social behaviour, antifeedant properties and also impact reproductive capability | 74% | Japan | Himmi et al., 2013 |

| 12 | Cissusquadrangularis,Pennisetum purpureum, Vetiveria zizanoides | Leaves | Acetone and Hexane extracts | Disrupt cuticle, neural transmission, has antifeedant properties, interfere with chitin synthesis | 90% | Africa | Kasseney et al., 2016 |

| 13 | L. leucocephala, A. paniculata, A. indica and P. niruri | Leaves | Flavonoids and Methanolic extracts | Antioxidant properties lead to disruption of oxidative balance, disrupt cellular membranes and nervous system | 70-100% | Malaysia | Bakaruddin et al., 2018 |

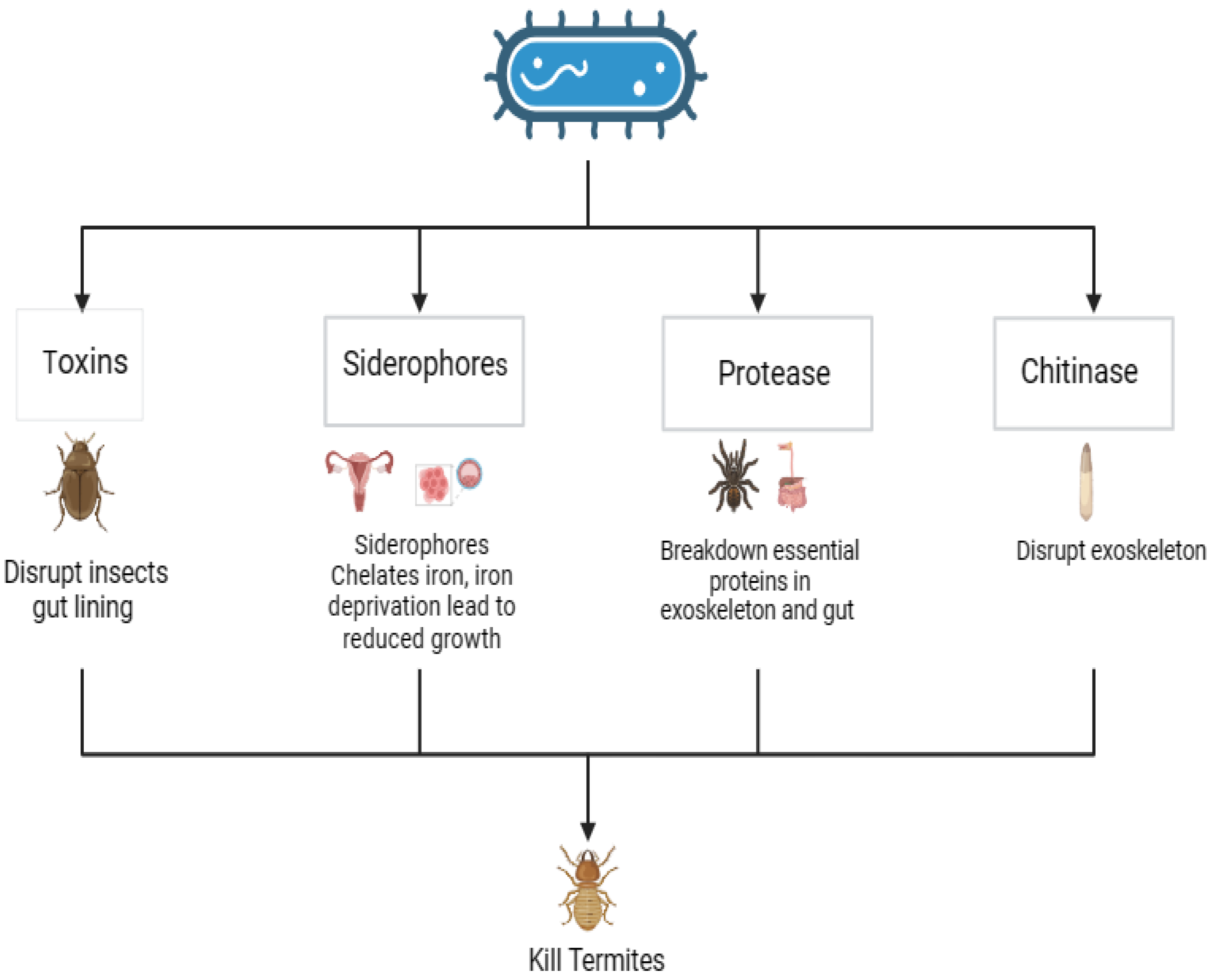

3.3.2. Management of Termites using Bacteria

| Bacteria | Termites | Enzymeformulations | Mode of Action | Country | Mortality Rate | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stentrophomons maltophilia | Coptotermes heimi and Heterotermes indicola | Chitinase | Disruption of cuticle | Pakistan | 53 % | Jabeen et al., 2018 |

| Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Reticulitermes flavipes | Protease | Alter haemolymph protein that affect cellular immune response, Disrupt essential processes like digestion, respiration | Korea | 70% | Zeng et al., 2016 |

| Serratia marcescens (SM1) | Odontotermes formosanus (Shiraki) | Chitinase enzymes | Hydrolyzes chitin in locust midgut and perforates intestinal membranes, making insecticidal proteins more likely to penetrate the insect body and destroy the digestive tract | China | NA | Fu et al., 2020 |

| Rhizobium radiobacter, Alcaligenes latus, Aeromonas caviae | Odontotermes obesus | HCN production | Disrupt electron transport chain and preventing cells from utilizing oxygen | India | 70% mortality followed by 1 hr incubation | Devi et al., 2007 |

| Serratia marcescens | Odontotermes formosans | Protease | Cuticle damage, disrupt microbial balance in termite gut | China | 80 % mortality after 72 hours | Fu et al., 2020 |

| Entrobacter cloacae | Odontotermes obesus | Insecticidal Proteins | Affects the cellular immune response | China | NA | Zhang et al., 2010 |

| Citrobacter freundii | Coptotermes spp. | CellulaseEnzyme | Breaks cellulose present in cell wall so disrupt cuticle | Africa | NA | Omoya and Kelley, 2014 |

| Bacillus licheniformis PR2 | Reticulitermes speratus kyushuensis Morimoto | Chitinase | Cuticle degradation | Korea | 88.9% after 3 hours | Moon et al., 2023 |

| B. licheniformis USMW10IK | G. sulphureus | Chitinase | Cuticle degradation | Malaysia | 22.8% after 48 h | Hussin and Mazid, 2020 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 | O. obesus | Cytochrome C Oxidase enzyme | Inhibit respiratory chain | India | NA | Devi et al., 2009 |

| B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis |

Microtermes obesi and Microcerotermes Beesoni |

Chitinase | Cuticle degradation | India | 80% mortality | Singha et al., 2010; Wang & Henderson, 2013 |

| Bacillus thuringiensis KJ3P1 | Macrotermes gilvus | Chitinase | Cuticle degradation | Indonesia | 50% after treatment | Pujiastuti et al., 2021 |

3.3.3. Fungal Species as a Biocontrol Agent for Termites

| Fungal Species | Termites | Mortality rate | LD50 | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus spp. |

Microcerotermes beesoni Snyder |

55 % | 3.69 × 107 conidia/ml | India | Pandey et al., 2013 |

| Beauveria bassiana | Microtermes obesi Holmgreen | 50% | 2 ×105 conidia /ml | India | Singha and Dutta,2011 |

| Isaria fumosorose | Coptotermes formosanus | 100% | Not Known | Malaysia | Jessica et al., 2019 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | Coptotermes formosanus | 62.8% | 2.5 ×104 conidia /ml | USA | Wright et al., 2008 |

| Metarhizium anisoploae | Odontotermes formasanus | 100% | 3×108 conidia/ml | USA | Dong et al., 2007 |

| Metarhizium brunneum Cb15-III | Odontotermes formasanus | 100% | 1×108 conidia /ml | Kenya | Ambele et al., 2020 |

| Aspergillus auricomus | Coptotermes curvignathus Holmgren | NA | 1.49 × 105 conidia/ml | India | Kamarudin and Lau, 2022 |

| Metarhizium anisoploae | Coptotermes curvignathus | 95% | 1×107 conidia/ml | Malaysia | Samsuddin et al., 2016 |

| M. anisopliae, B. bassiana and A. niger | Psammotermeshypostoma | 61.52, 35.54 and 20.06% | 4×106 spores/ml | Egypt | Somalian et al., 2019 |

| Metarhizium spp. B2.2 | Coptotermes spp. | 100% | 8.3 x 109 conidia/ml | Indonesia | Zulfiana et al., 2020 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | Microtermes obesi (Holmgren) | 90% | 2 × 107 conidia/ml | India | Deka et al., 2021 |

| Isaria farinosa | Nasutitermes cornige | 85% | 6.6 × 104 conidia/ml | Brazil | Lopes et al., 2017 |

| Paecilomyces fumosoroseus | Coptotermes sp. | NA | NA | USA | Dunlap et al., 2007 |

| Beauveria bassiana | Microtermes obesi | 25-40% | 4 ×106 conidia /ml | India | Padmaji and Kaur 2001 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae TK29 | Coptotermes formosanus | 75% | 1 × 108 conidia/ml | China | Keppanan et al., 2018 |

3.3.4. Nematodes Species as Biological Control for Termites

| Nematodes | Termites | Mortality | LD50 | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. bacteriophora | Microcerotermes diversus | 43.6% after 48 hours | 57.9 IJ/ml | Iraq | Zaidawi et al., 2020 |

| Steinernema pakistanense,S. Bifurcatum | Microtermes obesi | 100% after 48 hours | 350 -650 IJ/ml). | Pakistan | Javed et al., 2021 |

| Steinernema carpocapsae, Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and Heterorhabditis indica | Odontotermes obesus | S. carpocapsae (58.46%), followed by H. bacteriophora (45.45%) and H. indica (32.39%) after 48 hours | 1000 IJ/ml | Pakistan | Aslam et al., 2023 |

| Heterorhabditis indica | Odontotermes obesus | 87.98 % after 48 hours | 600 IJ/ml | India | Afroz et al., 2023 |

| Steinernema siamkayai, S. pakistanense and Heterorhabditis indica | Reticulitermes flavipes and Odontotermis hornei | 80% mortality S. pakistanense in 15.5 hrs, S. siamkayai in 16.3 hrs H. indica in 19.8 hrs | 5.84 IJ/ml, 5.68 IJ/ml, 5.00 IJ/ml | Pakistan | Razia and Sivaramakrishnan, 2016 |

| Steinernema karii | Coptotermes formosanus | 100% mortality after 96 hours | Not Known | Kenya | Wagutu et al., 2017 |

| Steinernema feltiae | Reticulitermes tibialis | Not Known | Not Known | USA | Epsky and Capinera,1988 |

| Steinernema thermophilum | Odontotermes obesus | 42 - 48 % mortality after 72 hours | Not Known | India | Rathour et al., 2014 |

| Heterorhabditis sonorensis Azohoue2 | G. mellonella | 63.2% mortality after 48 hours | Not Known | India | Rahman et al., 2011 |

| Steinernema riobrave Cabanillas | H. aureus | 80% mortality after 3 days | Not known | USA | Yu et al., 2006 |

3.3.5. Potential of Viruses as Biocontrol Agent for Termites

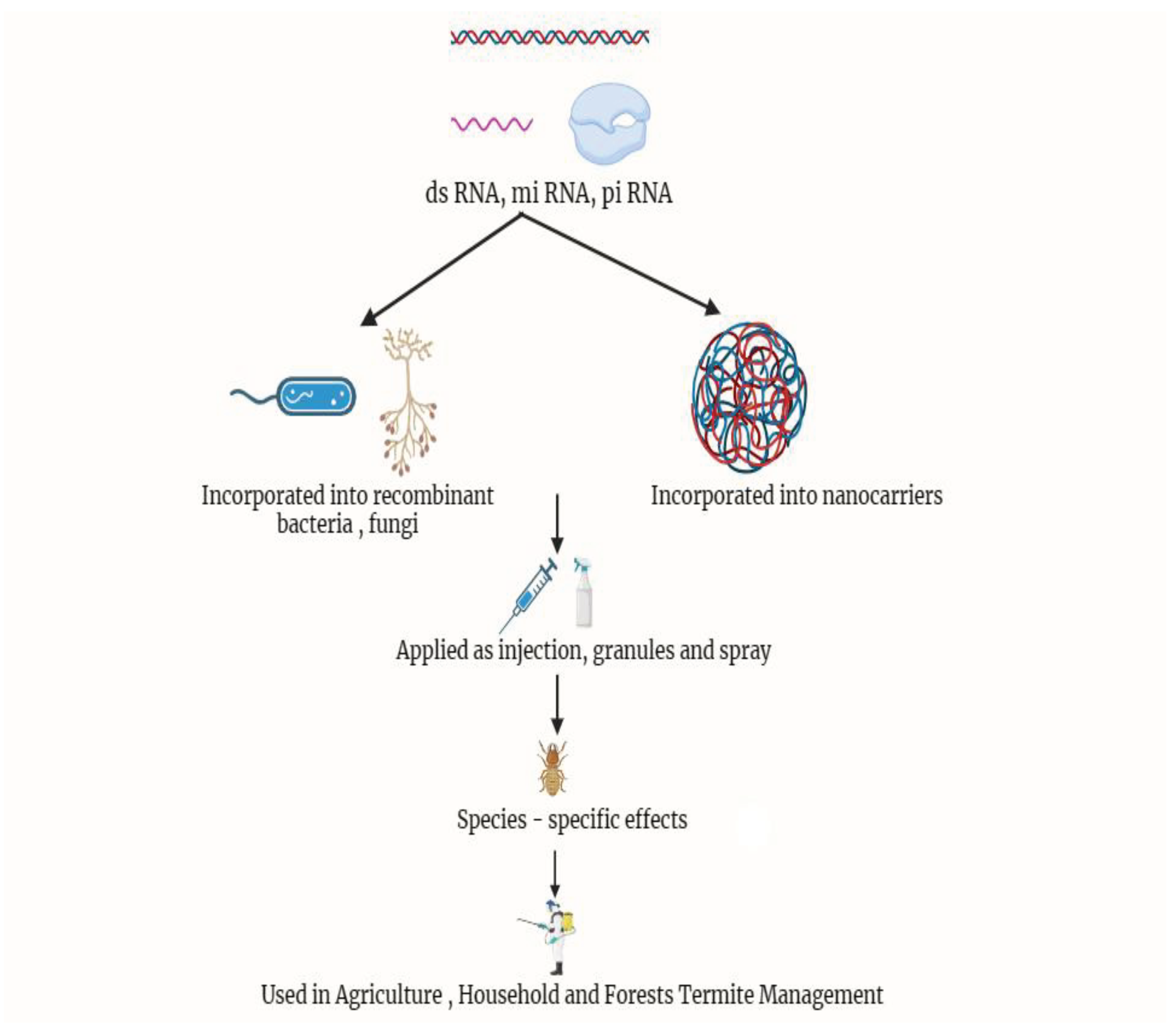

3.3.6. RNAi for Termite Management

| Species | Target gene | Target Gene Function | Type of RNA | Delivery Method | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reticulitermes chinensis and Odontotermes formosanus | Olfactory coreceptor | Necessary for odorant detection | dsRNA | Injection | China | Gao et al., 2020 |

| Odontotermes formosanus | Termicin | Antifungal activity | dsRNA | Feeding | China | Feng et.al, 2022 |

| C. formosanus | Protistan gene | Importantfor protists lignocellulosic process | siRNA | Feeding | China | Liu et al., 2017 |

| Zootermopsis nevadensis | Met, 20E signaling and nuclear receptor, Hormone receptor 39 | Methoprene Tolerant maintains the action of juvenile hormone 20 E signaling and nuclear receptor regulates egg development Hormone Receptor 39 helps in reproductive gland development | dsRNA | Injection | Japan | Masuoka et al., 2018 |

| Hodotermopsis holmgreen | Dac and Distal less | Dac helps in egg and legs development Distal less involved in egg development | ds RNA | Injection | Japan | Sugime et al., 2019 |

| Nasutitermes takasagoensis | Deformed gene | Involved in determining mandibular positional information during pre-soldier differentiation | siRNA | Injection | Japan | Toga et al., 2013 |

4. Conclusion

5. Future Prospectives

Abbreviations

References

- de Figueirêdo, R.E.C.R.; Vasconcellos, A.; Policarpo, I.S.; Alves, R.R.N. Edible and medicinal termites: a global overview. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2015, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.; Aidoo, O.; Ghisletta, M.; Osei-Owusu, J.; Saraswati, Y.; Bhardwaj, K.; Khalid, W.; Fernando, I.; Golik, A.; Nagdalian, A.; et al. African edible insects as human food – a comprehensive review. J. Insects Food Feed. 2023, 10, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoo, O.F.; Osei-Owusu, J.; Asante, K.; Dofuor, A.K.; Boateng, B.O.; Debrah, S.K.; Ninsin, K.D.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Chia, S.Y. Insects as food and medicine: a sustainable solution for global health and environmental challenges. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1113219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muon, R.; Ket, P.; Sebag, D.; Boukbida, H.A.; Podwojewski, P.; Hervé, V.; Ann, V.; Jouquet, P. Termite constructions as patches of soil fertility in Cambodian paddy fields. Geoderma Reg. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subekti, N., Yoshimura, T., Rokhman, F., & Mastur, Z. (2015). Potential for subterranean termite attack against five bamboo species in correlation with chemical components. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 28, 783-788.

- Murthy, K.S.; Resources, P.B.N. 2.N.B.O.A.I. Diversity and abundance of Subterranean Termites in South India. Indian J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2020, 8, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.K.; Su, N.-Y. Managing Social Insects of Urban Importance. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2012, 57, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Ning, L. N. , Yan Xing, Y. X., Zhang MeiLing, Z. M., Xie Lei, X. L., Wang Qian, W. Q., Huang YongPing, H. Y., & Zhou ZhiHua, Z. Z. (2011). a: Microbiome of fungus-growing termites.

- Scharf, M.E. Omic research in termites: an overview and a roadmap. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 76–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wekhe, C.; Ugbomeh, A.P.; Ebere, N.; Bawo, D.D.S. Subterranean Termites of a University Environment in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Asian J. Biol. 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subekti, N., Yoshimura, T., Rokhman, F., & Mastur, Z. (2015). Potential for subterranean termite attack against five bamboo species in correlation with chemical components. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 28, 783-788.

- Smagghe, F.; Spooner-Hart, R.; Chen, Z.-H.; Donovan-Mak, M. Biological control of arthropod pests in protected cropping by employing entomopathogens: Efficiency, production and safety. Biol. Control. 2023, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farook, U. B., Khan, Z. H., Ahad, I., Maqbool, S., Yaqoob, M., Rafieq, I., & Sultan, N. (2019). A review on insect pest complex of wheat (Triticum aestivum ). Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 7(1), 1292-1298.

- Sharma, A. K., Babu, K. S., Nagarajan, S., Singh, S. P., & Manoj, K. (2004). Distribution and status of termite damage to wheat crop in India. Indian Journal of Entomology, 66(3), 235-237.

- Parween, T.; Jan, S.; Mahmooduzzafar, S.; Fatma, T.; Siddiqui, Z.H. Selective Effect of Pesticides on Plant—A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 56, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Chandel, R.S.; Verma, K.S.; Joshi, M.J. Termites in Important Crops and Their Management. Indian J. Èntomol. 2021, 83, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B. , Khan, M. A., Paul, S., Shankarganesh, K., & Chakravorty, S. (2018). Termites and Indian agriculture. Termites and Sustainable Management: Volume 2-Economic Losses and Management, 51-96.

- Parween, T., Bhandari, P., & Raza, S. K. (2016). Survey and identification of termite in some selected parts of India. Res J Life Sci Bioinform Pharm Chem Sci, 2, 122-135.

- Roy, S.; Prasad, A.K.; Neave, S.; Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Nagpal, A.; Borah, K.; Rahman, A.; Sarmah, M.; Sarmah, S.R.; Pandit, V. Nonchemical based integrated management package for live-wood eating termites in tea plantations of north-east India. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2020, 40, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatro, G.K.; Chatterjee, D. Termites as Structural Pest: Status in Indian Scenario. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B: Biol. Sci. 2017, 88, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, D.K.; Kalleshwaraswamy, C.M.; Iyyanar, D.; Singh, M.; Jain, R.K.; Kasturi, N.; Ranjith, M.; Mahadevaswamy, H.M.; Asokan, R. First interception of two wood feeding potential invasive Coptotermes termite species in India. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2020, 41, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleshwaraswamy, C.M. Potential Invasive Termites in India and Importance of Integrative Taxonomy. Indian J. Èntomol. 17. [CrossRef]

- de Mello, A.P.; da Costa, B.G.; Da Silva, A.C.; Silva, A.M.B.; Bezerra-Gusmão, M.A. Termites in historical buildings and residences in the semiarid region of Brazil. Sociobiology 2014, 61, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmão, M.A.B.; Barbosa, A.M.S.; Mello, A.P.; Oliveira, J.V.; Barros, A.T. Perceptions of termites in urban areas of semiarid Brazil. Biotemas 2014, 27, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsbha Gebreslasie, A. G., & Hintsa Meressa, H.M. (2018). Evaluation of chemical, botanical and cultural management options of termite in Tanqua Abergelle district, Ethiopia.

- Cao, R.; Su, N.-Y. Temperature Preferences of Four Subterranean Termite Species (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) and Temperature-Dependent Survivorship and Wood-Consumption Rate. Ann. Èntomol. Soc. Am. 2015, 109, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, Z.-Y.; Pan, D.-Z.; Pan, C.-H.; Chen, L.-H. Effects of Termites on Soil pH and Its Application for Termite Control in Zhejiang Province, China. Sociobiology 2017, 64, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Sohail, Mustafa, Tariq, Riaz, M. A., & Hussain, A. B. I. D. (2006). Efficacy of insecticides against subterranean termites in sugarcane. Int. J. Agric. Biol, 8(4), 508-510.

- Iqbal, N. , & Saeed, S. (2013). Toxicity of six new chemical insecticides against the termite, Microtermes mycophagus D.(Isoptera: Termitidae: Macrotermitinae). Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 45(3).

- Liu, N.; Yan, X.; Zhang, M.; Xie, L.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z. Microbiome of Fungus-Growing Termites: a New Reservoir for Lignocellulase Genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.Y.; Palli, S.R. Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges of Insect RNA Interference. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2020, 65, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M. , Verma, S., & Sharma, S. (2018). Eco-friendly termite management in tropical conditions. Termites and Sustainable Management: Volume 2-Economic Losses and Management, 137-164.

- Essien, R. A. , Oboho, D. E., Imakwu, C. A., Atteh, I., & Okwor, J. (2023). Laboratory Evaluation of Termiticidal Efficacy of Cymbopogon citratus Stapf leaf Extract against Termites, Macrotermes bellicosus (Blattodea: Termitidae) in Obio Akpa Community, Oruk Anam Akwa Ibom State-Nigeria. Journal of Experimental Research, 11(2).

- A Oksari, A.; Susanty, D.; Rizki, F.H.; Wanda, I.F.; Arinana; Dadang Potential of Dioscorea bulbifera L. as a bio-insecticide in controlling dry wood termites (Cryptotermes cynocephalus Ligh.). IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehry, A. Z. , Zaitoun, A. A., & Abo-Hassan, R. A. (2014). Insecticidal activities of some plant extracts against subterranean termites, Psammotermes hybostoma (Desneux)(Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). International Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 4(9), 257-260.

- Adfa, M.; Wiradimafan, K.; Pratama, R.F.; Sanjaya, A.; Triawan, D.A.; S. , S.Y.; Ninomiya, M.; Rafi, M.; Koketsu, M. Anti-Termite Activity of Azadirachta excelsa Seed Kernel and Its Isolated Compound against Coptotermes curvignathus. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2023, 51, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M. Z. , Ali, M. F., Mansour, M. M., Ali, H. M., Abdel Moneim, E. M., & Abdel-Megeed, A. (2020). Anti-termitic activity of three plant extracts, chlorpyrifos, and a bioagent compound (protecto) against termite Microcerotermes eugnathus silvestri (Blattodea: Termitidae) in Egypt. Insects, 11(11), 756.

- Pandey, A.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Banerjee, S.; Pakshirajan, K.; Singh, L. Antitermitic activity of plant essential oils and their major constituents against termite Odontotermes assamensis Holmgren (Isoptera: Termitidae) of North East India. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2012, 75, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, S. I., Adeboye, A. G., Yalli, F. A., & Dikwa, M. A. (2019). Phytochemical constituents and termicidal activity of essential oils from Syzygium Aromaticum (Clove bud. Fudma Journal of sciences, 3(2), 220-225.

- Zahtamal, S. A. , Marsifah, T., Soesilohadi, R. H., Handayani, S., & Handayani, S. M. Toxic Potential of Papaya (Carica papaya) Leaves as Termicidal Against Coptotermes curvignathus Holmgren.

- Umang, U.; Kaundal, A.K.; Kumari, P.; Kaur, S. Investigations On Anti- Termite Activity Of Eucalyptus Globulus Leaf Extract. 2023, 3397–3405. [CrossRef]

- Tarmadi, D.; Himmi, S.K.; Yusuf, S. The Efficacy of the Oleic Acid Isolated from Cerbera Manghas L. Seed Against a Subterranean Termite, Coptotermes Gestroi Wasmann and a Drywood Termite, Cryptotermes Cynocephalus Light. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 20, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmi, S.K.; Tarmadi, D.; Ismayati, M.; Yusuf, S. Bioefficacy Performance of Neem-based Formulation on Wood Protection and Soil Barrier against Subterranean Termite, Coptotermes Gestroi Wasmann (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 17, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasseney, B. D., Nyamador, W. S., Abla, D. Ã., Ketoh, G. K., & AdolÃ, I. (2016). Termiticidal activities of few plant extracts against Macrotermes subhyalinus smeathman and Trinervitermes geminatus wasmann (Isoptera: Termitidae) survival. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 11(28), 2475-2480.

- Bakaruddin, N.H.; Dieng, H.; Sulaiman, S.F.; Ab Majid, A.H. Evaluation of the toxicity and repellency of tropical plant extract against subterranean termites, Globitermes sulphureus and Coptotermes gestroi. Inf. Process. Agric. 2018, 5, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalha, C.S.; Singh, P.P.; Kang, S.S.; Hunjan, M.S.; Gupta, V.; Sharma, R. Entomopathogenic Viruses and Bacteria for Insect-Pest Control. In Integrated Pest Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 978-0-12-398529-3. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J. H. , Ajuna, H. B., Won, S. J., Choub, V., Choi, S. I., Yun, J. Y.,... & Ahn, Y. S. (2023). The Anti-Termite Activity of Bacillus licheniformis PR2 against the Subterranean Termite, Reticulitermes speratus kyushuensis Morimoto (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Forests, 14(5), 1000.

- Devi, K.K.; Kothamasi, D. Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 can kill subterranean termite Odontotermes obesus by inhibiting cytochrome c oxidase of the termite respiratory chain. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 301, 147–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, F., Hussain, A., Manzoor, M., Younis, T., Rasul, A., & Qazi, J. I. (2018). Potential of bacterial chitinolytic, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, in biological control of termites. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control, 28, 1-10.

- Zeng, Y.; Hu, X.P.; Suh, S.-J. Characterization of Antibacterial Activities of Eastern Subterranean Termite, Reticulitermes flavipes, against Human Pathogens. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0162249–e0162249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R., Qi, X., Feng, K., Xia, X., & Tang, F. (2019). Identification and characteristics of a strain of Serratia marcescens isolated from the termites, Odontotermes formosanus. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University, 62(01), 76.

- Devi, K.K.; Seth, N.; Kothamasi, S.; Kothamasi, D. Hydrogen Cyanide-Producing Rhizobacteria Kill Subterranean Termite Odontotermes obesus (Rambur) by Cyanide Poisoning Under In Vitro Conditions. Curr. Microbiol. 2007, 54, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang PengBo, Z. P. , Yan Xun, Y. X., Qiu XueHong, Q. X., & Han RiChou, H. R. (2010). Application of transgenic Enterobacter cloacae with the insecticidal tcdA1B1 genes for control of Coptotermes formosanus (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) in the field.

- Omoya, F.; Kelly, B. Variability of the potency of some selected entomopathogenic bacteria (Bacillus spp. and Serratia spp.) on termites, Macrotermes bellicosus (Isoptera: Termitidae) after exposure to magnetic fields. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2014, 34, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, N.A.; Ab Majid, A.H. Termiticidal activity of chitinase enzyme of Bacillus licheniformis, a symbiont isolated from the gut of Globitermes sulphureus worker. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, D. I. P. E. N. D. R. A. , Singha, B. K. ( 2010). In vitro pathogenicity of Bacillus thuringiensis against tea termites. Journal of Biological Control, 279–281.

- Wang, C.; Henderson, G. Evidence of Formosan Subterranean Termite Group Size and Associated Bacteria in the Suppression of Entomopathogenic Bacteria, Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies israelensis and thuringiensis. Ann. Èntomol. Soc. Am. 2013, 106, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujiastuti, Y.; Riskal, A.; Suparman; Arsi, A. ; Gunawan, B.; Sulistyani, D.P. Effectiveness of Proteins and Supernatants Isolated from Bacillus Thuringiensis-Based Bio-Insecticides Against Termites Macrotermes Gilvus (Isoptera: Termitidae). IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 810, 012049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P., Singha, L. P., & Singha, B. (2013). Colonization and antagonistic activity of entomopathogenic Aspergillus sp. against tea termite (Microcerotermes beesoni Snyder). Current Science, 105(9), 1216-1219.

- Yii, J.E.; Bong, C.F.J.; King, J.H.P.; Kadir, J. Synergism of entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae incorporated with fipronil against oil palm pest subterranean termite, Coptotermes curvignathus. Plant Prot. Sci. 2016, 52, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, M. Laboratory and field evaluation of Metarhizium anisopliae var. anisopliae for controlling subterranean termites.. 2011, 40, 244–50. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zaidawi, J.B.; Karimi, J.; Moghadam, E.M. Entomopathogenic Nematodes as Potential Biological Control Agents of Subterranean Termite, Microcerotermes diversus (Blattodea: Termitidae) in Iraq. Environ. Èntomol. 2020, 49, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Sun, P.; Lei, C.; Huang, Q. The Influence of Allogrooming Behavior on Individual Innate Immunity in the Subterranean TermiteReticulitermes chinensis(Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). J. Insect Sci. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singha, D.; Singha, B.; Dutta, B.K. Potential of Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana in the control of tea termite Microtermes obesi Holmgren in vitro and under field conditions. J. Pest Sci. 2010, 84, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessica, J.J.; Peng, T.L.; Sajap, A.S.; Lee, S.H.; Syazwan, S.A. Evaluation of the virulence of entomopathogenic fungus, Isaria fumosorosea isolates against subterranean termites Coptotermes spp. (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). J. For. Res. 2018, 30, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.S.; Lax, A.R. Combined effect of microbial and chemical control agents on subterranean termites. J. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Huang, H.; Hu, Y. Characterization of a newly discovered China variety of Metarhizium anisopliae (M. anisopliae var. dcjhyium) for virulence to termites, isoenzyme, and phylogenic analysis. Microbiol. Res. 2007, 162, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambele, C.F.; Ekesi, S.; Bisseleua, H.D.B.; Babalola, O.O.; Khamis, F.M.; Djuideu, C.T.L.; Akutse, K.S. Entomopathogenic Fungi as Endophytes for Biological Control of Subterranean Termite Pests Attacking Cocoa Seedlings. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarudin, M.A.; Abdullah, S.; Lau, W.H. Efficacy of soil-borne entomopathogenic fungi against subterranean termite, Coptotermes curvignathus Holmgren (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2022, 32, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsuddin, A. S. B. (2017). Interaction between an entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae and its host subterranean termites Coptotermes curvignathus during infection process.

- Somalian, M.; Allah, R.K.; Hammad, M.; Ebnalwaled, K. Biological control of subterranean termites (Psammotermes hypostoma ) by entomopathogenic fungi. Sci. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiana, D.; Zulfitri, A.; Lestari, A.S.; Krishanti, N.P.R.A.; Meisyara, D. Production of Conidia by Entomopathogenic Fungi and Their Pathogenicity Against Coptotermes sp. Biosaintifika: J. Biol. Biol. Educ. 2020, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, B. , Babu, A., Peter, A. J., Kumhar, K. C., Sarkar, S., Rajbongshi, H.,... & Talluri, V. R. (2021). Potential of the entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae in controlling live-wood eating termite, Microtermes obesi (Holmgren)(Blattodea: Termitidae) infesting tea crop. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control, 31(1), 1-8.

- Lopes, R. D. S. , Lima, G. D., Correia, M. T. D. S., da Costa, A. F., Lima, E. Á. D. L. A., & Lima, V. L. D. M. (2017). The potential of Isaria spp. as a bioinsecticide for the biological control of Nasutitermes corniger. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 27(9), 1038-1048.

- Dunlap, C. A., Jackson, M. A., & Wright, M. S. (2007). A foam formulation of Paecilomyces fumosoroseus, an entomopathogenic biocontrol agent. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 17(5), 513-523.

- Padmaja, V. , & Kaur, G. (2001). Use of the fungus Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill (Moniliales: Deuteromycetes) for controlling termites. Current Science, 81(6), 645-647.

- Keppanan, R.; Sivaperumal, S.; Aguila, L.C.R.; Hussain, M.; Bamisile, B.S.; Dash, C.K.; Wang, L. Isolation and characterization of Metarhizium anisopliae TK29 and its mycoinsecticide effects against subterranean termite Coptotermes formosanus. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 123, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poinar Jr, George O. "Taxonomy and biology of Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae." Entomopathogenic nematodes in biological control 54 (1990).

- Al-Zaidawi, J.B.; Karimi, J.; Moghadam, E.M. Entomopathogenic Nematodes as Potential Biological Control Agents of Subterranean Termite, Microcerotermes diversus (Blattodea: Termitidae) in Iraq. Environ. Èntomol. 2020, 49, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.; Ali, A.; Khanum, T.A. Biocontrol potential of the entomopathogenic nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) against the termite species, Microtermes obesi (Holmgren) (Blattodea: Termitidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2021, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A.; Chi, D.-F.; Abbasi, A.; Arshad, M. Biocontrol Potential of Entomopathogenic Nematodes against Odontotermes obesus (Blattodea: Termitidae) under Laboratory and Field Conditions. Forests 2023, 14, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, A.; Shaw, S.S.; Naralasetti, R.; Saxena, R.R. Comparative bio-efficacy of indigenous isolates of Heterorhabditis indica from Chhattisgarh against Odontotermes obesus under laboratory conditions. J. Exp. Zoöl. India 2022, 26, 1245–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razia, M., & Sivaramakrishnan, S. (2016). Evaluation of entomopathogenic nematodes against termites. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 4(4), 324-327.

- Wagutu, G. K., Kang’ethe, L. N., & Waturu, C. N. (2017). Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematode (Steinernema karii) in control of termites (Coptotermes formosanus). Journal of Agriculture, Science and Technology, 18(1), 55-64.

- Epsky, N.D.; Capinera, J.L. Efficacy of the Entomogenous Nematode Steinernema feltiae Against a Subterranean Termite, Reticulitermes tibialis (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). J. Econ. Èntomol. 1988, 81, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathour, K. S., Ganguly, S., Das, T. K., Singh, P., Kumar, A., & Somvanshi, V. S. (2014). Biological management of subterranean termites (Odontotermes obesus) infesting wheat and pearl millet crops by entomopathogenic nematodes. Indian Journal of Nematology, 44(1), 97-100.

- El-Bassiouny, A.R.; El-Rahman, R.M.A. SUSCEPTIBILITY OF EGYPTIAN SUBTERRANEAN TERMITE TO SOME ENTOMOPATHOGENIC NEMATODES. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 89, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. , Gouge, D. H., & Baker, P. (2006). Parasitism of subterranean termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae: Termitidae) by entomopathogenic nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae; Heterorhabditidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 99(4), 1112-1119.

- Gibbs, A.; Gay, F.; Wetherly, A. A possible paralysis virus of termites. Virology 1970, 40, 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Fazairy, A.A.; Hassan, F.A. Infection of Termites by Spodoptera littoralis Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 1988, 9, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.Y.; Palli, S.R. Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges of Insect RNA Interference. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2020, 65, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wheeler, M.M.; Oi, F.M.; Scharf, M.E. RNA interference in the termite Reticulitermes flavipes through ingestion of double-stranded RNA. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 38, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, L.; Zhou, W.; Cai, Q.; Huang, Q. Roles of selenoprotein T and transglutaminase in active immunization against entomopathogenic fungi in the termite Reticulitermes chinensis. J. Insect Physiol. 2020, 125, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, C.-C.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Guan, J.-X.; Lei, C.-L.; Huang, Q.-Y. Isocitrate dehydrogenase-mediated metabolic disorders disrupt active immunization against fungal pathogens in eusocial termites. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 93, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza-Mora, M.A.; Davis, H.E.; Meconcelli, S.; Plarre, R.; McMahon, D.P. Inhibition of a Secreted Immune Molecule Interferes With Termite Social Immunity. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xia, S.; Wu, D.; Behm, J.E.; Meng, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wen, P.; Hughes, A.C.; Yang, X. Understanding global and regional patterns of termite diversity and regional functional traits. iScience 2022, 25, 105538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Xu, H. Silencing Orco Impaired the Ability to Perceive Trail Pheromones and Affected Locomotion Behavior in Two Termite Species. J. Econ. Èntomol. 2020, 113, 2941–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Li, W.; Tang, X.; Luo, J.; Tang, F. Termicin silencing enhances the toxicity of Serratia marcescens Bizio (SM1) to Odontotermes formosanus (Shiraki). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 185, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X. J., Xie, L., Liu, N., Zhan, S., Zhou, X. G., & Wang, Q. (2017). RNA interference unveils the importance of Pseudotrichonympha grassii cellobiohydrolase, a protozoan exoglucanase, in termite cellulose degradation. Insect Molecular Biology, 26(2), 233-242.

- Masuoka, Y. , Yaguchi, H., Toga, K., Shigenobu, S., & Maekawa, K. (2018). TGF β signaling related genes are involved in hormonal mediation during termite soldier differentiation. PLoS genetics, 14(4), e1007338.

- Sugime, Y.; Oguchi, K.; Gotoh, H.; Hayashi, Y.; Matsunami, M.; Shigenobu, S.; Koshikawa, S.; Miura, T. Termite soldier mandibles are elongated by dachshund under hormonal and Hox gene controls. Development 2019, 146, dev171942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toga, K.; Saiki, R.; Maekawa, K. Hox Gene Deformed is likely involved in mandibular regression during presoldier differentiation in the nasute termite Nasutitermes takasagoensis. J. Exp. Zoöl. Part B: Mol. Dev. Evol. 2013, 320, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Agriculture Crops | Termites | Yield Loss (%) | Place | Symptoms of Damage | Year | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Cryptotermes heimi,Odontotermes obesus,O. redemanni,M obesi, O. feae,T. biformis | 43%- 80% | Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Haryana, Kerala and Tamil Nadu | Affected plants dry up completely and may give rise to white ears | 1995 -2016 | Farook et al., 2019 Sharma et al., 2004 |

| Maize | O. obesus,M. obesi | 30% - 75% | Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab | From seedling emergence to ear growth, termites target every stage of the maize crop | 1984-2010 | Parween et al., 2016 Rana et al., 2021 |

| Pulses | Odontotermes obesus, Odontotermes parvide | 25%-90% | Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab | Bore holes on buds, flowers or pods Silvery patches and streaks on leaves |

1990-2012 | Paul et al., 2018 |

| Groundnut | Microtermes spp., Odontotermes spp., Amitermes spp., Microtermes spp., Odontotermes spp. | 15%-30% | Punjab, U.P., Rajasthan, Delhi, Haryana, Karnataka, Gujarat, M.P., Maharashtra, Kerala | Root and stem hollowingPod bore holes | 1984-2012 | Paul et al., 2018 |

| Soyabean | M. albopartitus,M. redenianus,A. latinotus,A. tenax | 20%-25% | Punjab, Haryana | Stem lesions, Wilted or curled leaves | 1980-2012 | Paul et al., 2018 |

| Coconut | Microtermes spp., Microcerotermes spp., Coptotermes spp. | 20%-30% | Western coast of India | Yellowing of leavesStunted growth | 1990-2016 | Paul et al., 2018 |

| Sugarcane | Odontotermes redemanni | 74 % | Punjab, Haryana | Yellowing and wilting of leaves | 1986-2015 | Parween et al., 2016 |

| Tea | M. beesoni | 11%- 55 % | North East India | Galls on the roots affecting nutrient uptake Shoot growth is retarded and photosynthetic rates may decrease |

1980-2016 | Roy et al., 2020 |

| Chilli Pepper | O. obesus andM. obesi | 45 % | Rajasthan | Infested leaves develop crinkles and curl upwards Elongated petioles (leaf stalks) Buds become brittle and may drop down. Early-stage infestations lead to stunted growth | 1984-2012 | Parween et al., 2016 |

| Cotton | M. mycophagus,O. obesi | 25% | Rajasthan, Gujarat,Haryana, Punjab and Madhya Pradesh | Drying and drooping of terminal shoots Shedding of squares (immature flower buds) and young bolls (developing cotton capsules). | 1980-2014 | Parween et al., 2016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).