1. Introduction

The urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and combat climate change has provoked the rapid adoption of renewable energy systems and electrification of the transportation sector. LIBs have gained prominence in both of these areas in recent years. They are used as stationary storage to compensate the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources by fast and efficiently storing the excess energy during periods of high production and releasing it during low or no generation periods. In the transportation sector LIBs are widely used as traction batteries in the area of electromobility due to their high energy density and power capability.

However, like any electrochemical energy storage system, LIBs undergo degradation over time. The SOH is a widely adopted metric to assess the degradation of LIBs, typically expressed as a percentage value that represents the remaining useful life of the battery and is commonly based either on the inner resistance or on the remaining capacity relative to their initial values.

This work presents a methodology to estimate the capacity based SOH, defined as follows:

where

is the nominal and

C the actual capacity. Accurate estimation of the SOH during operation is crucial for ensuring optimal performance, prolonging lifespan and preventing unexpected failures or safety hazards of battery systems. Due to the non-linear degradation and its complex underlying mechanisms and their interactions [

1], accurate online SOH estimation is a non-trivial task. Different methodologies can be found in literature for evaluating the SOH of LIBs with the most basic and accurate technique being coulomb counting while performing a complete discharge of the battery.

Other more sophisticated methods like incremental capacity analysis (ICA) [

2,

3], differential voltage analysis [

4] and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy [

5,

6] are widely discussed in literature for SOH evaluation under laboratory conditions. All three methods are rather suitable for online SOH estimation due to the need of a unique current profile, high measurement accuracy and further processing of the acquired data.

Recently discussed approaches for online SOH estimation can be roughly categorised in model-based [

7,

8,

9,

10] and data-driven [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] methods. Where model-based algorithms are built on a parameterised battery model, usually in a recursive implementation such as kalman filters. The underlying battery model can be either an equivalent circuit model [

7,

8] or an electrochemical model [

9,

10], where the latter is rather suitable for online SOH estimation due to its high computational complexity. The accuracy of model-based algorithms highly depends on the choice of the underlying battery model and its parameterisation, both of which require a high level of domain specific knowledge.

Data-driven methods, on the other hand, have the ability to map measured input data to labelled output data, being able to model complex and non-linear relationships without any information about the underlying physical or chemical processes. The quality of prediction can vary with the selection of the underlying algorithm and the choice, quality and amount of training data.

Many data-driven approaches for SOH prediction can be found in literature ranging from gaussian process regression [

14,

15], support vector machines [

16,

17] over deep learning [

18,

19,

20] and other neural network approaches [

12,

21] commonly using extracted features from voltage, current and/or temperature measurements as input data.

Zheng et al. [

22] analysed the change of terminal voltage during a charging process under constant current condition for various SOH and could show a significant change in inclination of the terminal voltage over time with falling SOH, making them a suitable base as an input feature for data-driven algorithms. Furthermore they used a particle swarm optimization algorithm to find the most linear part of the constant current charging curve and predict the SOH with a

RMSE = 1.9 % based on a linear assumption of the charged capacity within a fixed voltage range.

Wei et al. [

12] extracts features like peak height, area and width from filtered incremental capacity (IC) curves captured during constant current charging and uses a simple multi-layer perceptron neural network to predict the SOH. They evaluate different partial charging areas for different cell chemistries reaching a

MAE < 0.24 % for partial charging with a initial voltage of

Vinit < 3.7 V. Main limitations of this approach are the computational expensive filtering of the IC curve and further feature extraction.

Li et al. [

13] is using the voltage and time samples of partial charging curves under constant current condition as input features. They propose a deep neural network (DNN) consisting of four long short-term memory (LSTM) layers to process the partial charging curve as timeseries, hence being able to process raw sensor data of a battery management system (BMS) without any preprocessing or feature engineering.

The relatively complex topology of the proposed DNN demands a certain amount of storage and computational power, making it unsuitable for low budget embedded devices associated with most modern BMS. Furthermore, all of the above mentioned approaches do not consider different ageing scenarios in their datasets and, therefore cannot validate the robustness of the proposed algorithms against different ageing mechanisms caused by varying environmental conditions or usage of the batteries in a real world application.

This work is motivated by bridging the aforementioned research gap by building a dataset with eleven different ageing scenarios and proposes a storage optimised DNN with low computational complexity, based on a 1-dimensional convolutional neural network (1-D CNN) in combination with two LSTM layers. The proposed methodology will process time-series of raw sensor data (time, voltage, IC) of partial charging curves under constant current condition to predict the SOH of LIBs. Finally, the model is cross-validated over the different ageing scenarios to validate the robustness of the model against different ageing mechanisms.

2. Dataset

The dataset used for this work consists of ageing data collected from 22 Bexel INR18650-2600 cells, built from experiments carried out in-house as part of the LioBat project. The active materials are Lithium-Nickel-Manganese-Cobalt-Oxide (NMC) for the positive electrode and carbon (C) for the negative electrode. The specification of the cell is given in

Table 1.

2.1. Experimental

In order to represent different usage of batteries within the dataset, eleven different ageing scenarios where applied. They encompass a spectrum of different cycling strategies and calendric ageing. Each ageing scenario is applied to two individual cells. A detailed overview of the different scenarios is shown in

Table 2.

Within the experiments, characterisation tests where carried out in regular intervals of 50 equivalent full cycles for cells subjected to cycling and a 30-day interval for cells undergoing calendric ageing. The characterisation tests include the determination of the actual capacity and the acquisition of a full charging curve under constant current condition.

They were conducted under a controlled temperature environment of 35°C. The measurements and cycling were carried out using a Neware CT-4008-5V6A battery testing system.

The tests proceeded in 3 phases, each of them separated by a 30-minute rest time. The first phase brings the cell to an initial fully charged state by a charging process with a constant current of 1C until the cut-off voltage is reached, followed by a constant voltage step until the current attains a level of C/100. The second phase is oriented to determine the discharge capacity, by using coulomb counting while discharging the cell with a constant current of 1C until the terminal voltage is reaching the discharge cut-off voltage. After the capacity determination, the cell is fully discharged by applying a constant voltage until the current attains again a level of C/100. A third and final phase acquires the full charging curve by charging the cell with a current of 1C until the charge cut-off voltage is reached.

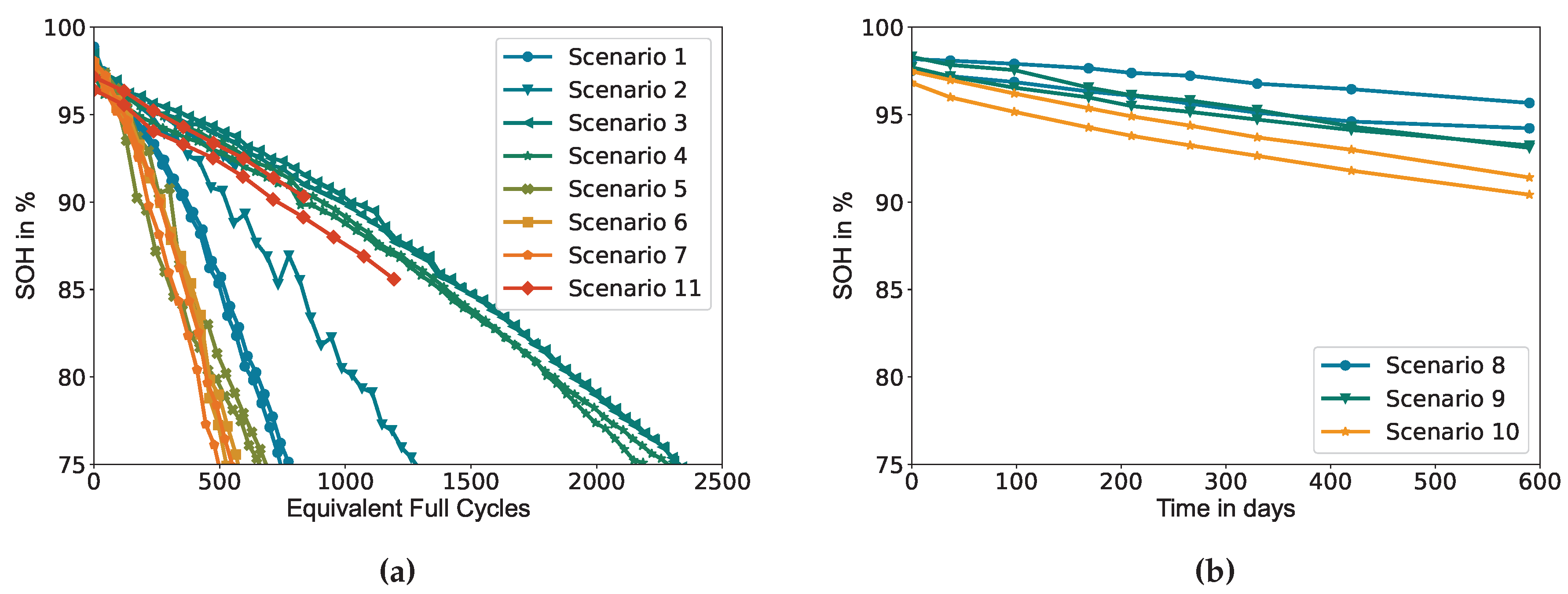

Figure 1 shows the trajectory of capacity degradation of all cells present in the dataset. All cycled cells are aged until they reach 75% of their nominal capacity. Cells number 3 (scenario 2) and 21 (scenario 11) broke down during the experiment with an abrupt drop of the terminal voltage to zero volts. Cell number 4 (scenario 2) shows an unexpectedly accelerated ageing rate compared to analogue scenarios, its data is nevertheless kept in the dataset to proof the robustness of the proposed methodology, even in cases of abnormal ageing behaviours.

2.2. Feature Selection and Data Preprocessing

The proposed model uses time, voltage and IC of partial charging curves under constant current condition (1C) as input features. The features are passed to the model as time series data with a sample rate of 5 seconds, and consisting of raw sensor data and derived values obtained from them.

As stated before, ICA is widely used in literature to determine capacity loss and identifying degradation mechanisms like loss of anode active material and loss of lithium inventory [

23] under laboratory conditions, where the IC is processed from the open circuit voltage (OCV) curve. The IC is given by

Here, Q is the charge in Ah and V the terminal voltage in V. To qualitatively determine the capacity from IC curves, the OCV has to be acquired by either charging the cell with a very small current and subsequent filtering or by incremental charging with a relaxation time in between.

Both of these methods are difficult to capture in a real-world application. Riviere et. al [

3] investigated the effect of c-rate, temperature and depth of discharge (DOD) on ICA and reached with an empirical capacity estimator a prediction error of less than 4% and, therefore, showed that IC curves are carrying information about the capacity degradation under various conditions. Taking this into account, this work uses the IC curve processed from the raw sensor data of the constant current charging curve as captured within the characterisation tests described in

Section 2.1 without any filtering, to keep the computational cost for the data preprocessing as low as possible.

Since the current is kept constant while charging and all features will be normalised before they are passed to the model, the charge

Q in equation

1 can be replaced by time

t, without losing information of the IC curve with respect to the capacity degradation. Hence, equation

1 can be simplified and reformulated as follows

With equation

3, the IC curve can be processed from the voltage and time samples of the charging curves and therefore is independent of the current measurement and potential measurement errors of the sensor from the BMS. An important prerequisite for this, of course, is a precise current measurement and control of the charger.

Considering practical applications, only partial charging curves within a voltage window of 3.7 V - 4.0 V are used as input features for the model. The upper boundary of 4.0 V was chosen to assure a constant current (CC) phase also under the operation with reduced DOD and to avoid incomplete CC phases in case of imbalanced battery packs. The choice of the lower boundary is a trade-off between the accuracy of prediction and the ability to frequently capture the whole voltage window, since a battery is rarely fully discharged in a real-world application. The lower boundary, of 3.7 V encompasses the main peak of the IC curve, which is representative of the intercalation stage II of the anode and displays the highest degree of variability with respect to the degradation of LIBs. Trails with different lower boundaries, showed a remarkable improvement of the prediction accuracy from 3.7 V downwards. Furthermore, a terminal voltage of 3.7 V is considered to be frequently reached in a real-world application.

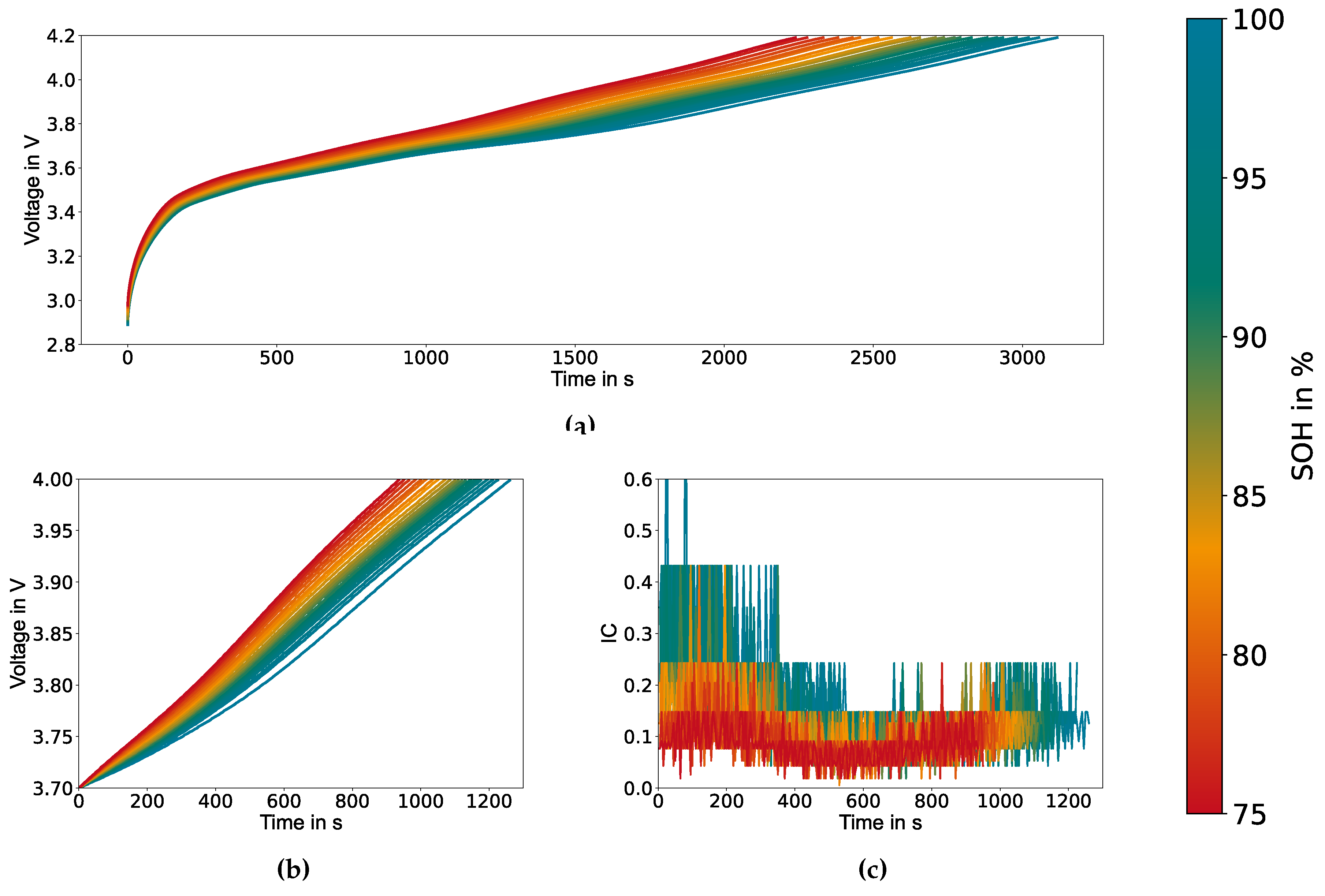

Figure 2(a) shows exemplary the full charging curves of cell number 1 for different SOH.

Figure 2(b) and

Figure 2(c) exhibit respectively the extracted partial charging curves and the IC cures derived from equation

3. Both of which will be passed to the model as input features. Despite the inherent noise of the IC curves, adding them as a input feature enhances model performance. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that using only voltage and time as input features also leads to a satisfactory level of model performance.

In order to meet the requirement of a constant input length for the proposed model, the time series data of the selected features were preprocessed by zero-padding to the length of the longest series in the dataset. This length is extended by an additional 10 samples to accommodate for charging curves with slightly longer duration, originated by LIBs with higher initial capacity than those included in the dataset. Finally, all features will undergo a min-max normalisation according to their minimum and maximum values within the whole dataset. Subsequently, the normalised data will be randomly partitioned into three distinct subsets, with 80% of the data used for training, 10% designated for validation, and 10% for testing.

3. Model Structure

Due to its ability to model complex relationships in data and learn hierarchical representations of time series, deep learning has recently emerged as a crucial tool for time series analysis and classification. This work proposes a deep learning model which combines a 1-D CNN and a LSTM neural network to predict the capacity of LIBs based on time series data from partial charging curves. In the proposed topology, the 1-D CNN layer provides the ability to extract additional features from the raw input data, while the LSTM layer is able to capture the long-term dependencies present in the time series data [

24].

3.1. 1-Dimensional Convolution Neural Network

A 1-D CNN layer applies a set of learnable filters to the input sequence in order to extract features that are useful for the given task. Each filter consists of a kernel which slides over the input sequence with a specific stride and width, performing a convolution operation. The output of this convolution is a new sequence, where each element is a weighted sum of the input elements that were covered by the kernel. For an input sequence

x, a filter of length

k and a stride of 1, the convolution operation in a discrete form is defined as

Where is the i-th element of the output sequence and is the j-th element of the learnable weight of the kernel. After the convolution operation, a non-linear activation function is applied to each element of the output sequence. This introduces non-linearity into the network and helps to capture more complex patterns in the data. In this work, the ReLU function is used as activation.

The number of filters used in a 1-D CNN layer determines the number of output channels, which can be thought of as different feature maps that capture different aspects of the input sequence. Each filter has its own set of learnable weights, that are adjusted during training.

3.2. Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network

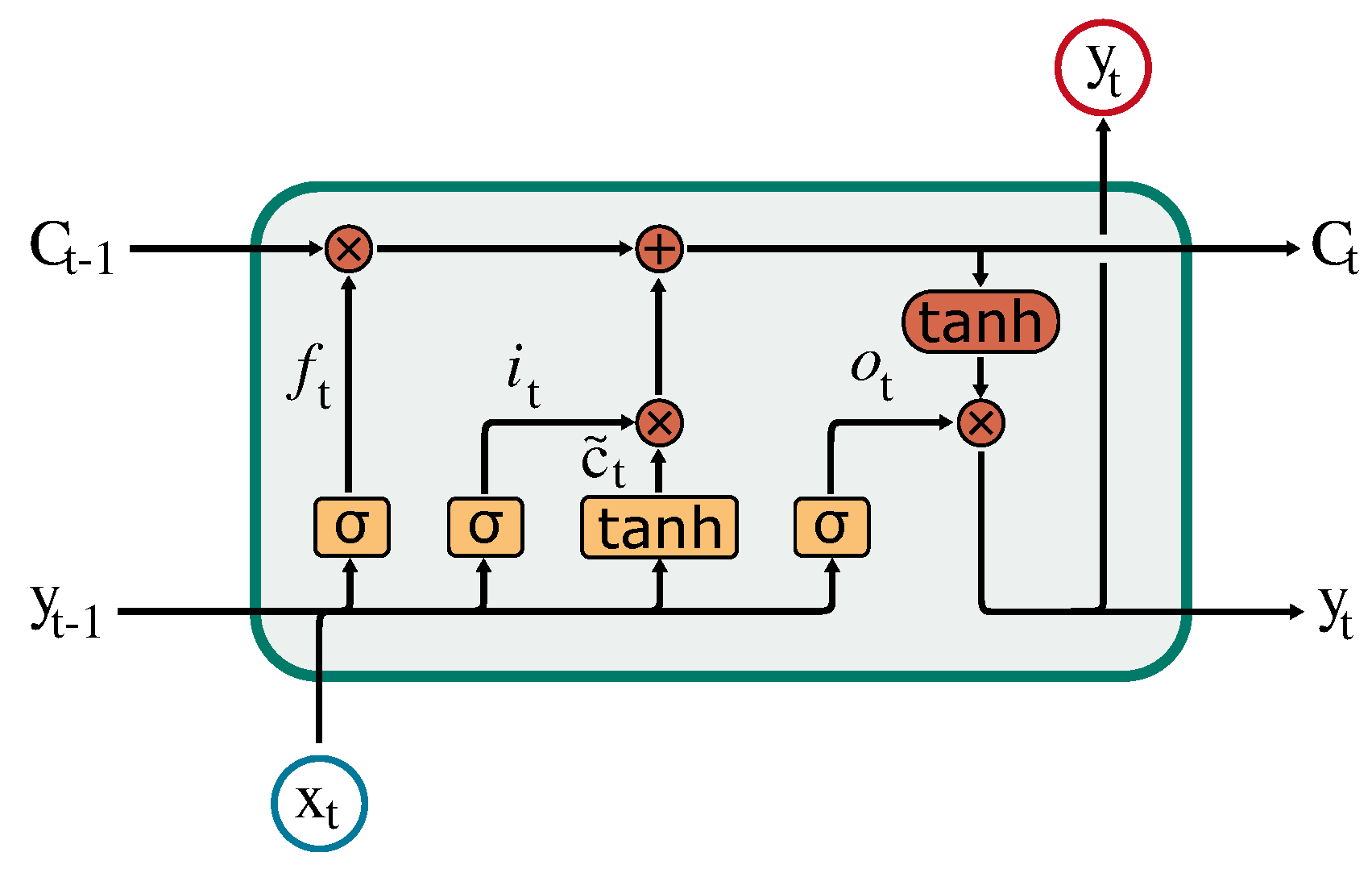

The LSTM neural network is a type of recurrent neural networks (RNN) designed to solve their limitations at learning long-term dependencies in sequential data by addressing the vanishing and exploding gradient problem of traditional RNNs. To do so, LSTM networks incorporate memory into the cell, allowing the selective storage and retrieval of information over long periods of time and, hence, making them a powerful tool to process time series data.

Figure 3 shows the architecture of a single LSTM cell. Where

is the input at time t,

the actual cell state, which can be interpreted as the memory of the cell.

is the cell state of the previous time step and

is called hidden state, which acts also as the output of the cell. Internally the cell consists of three gates, the forget gate

, the input gate

and the output gate

. All internal gates are based on the same equation but with their own trainable weights

W and biases

b.

The results or outputs of these gates decide by multiplication how much information will be forwarded from a specific state. The forget gate

controls how much information will be forwarded from the previous cell state to the actual cell state. The input state decides how much of the new generated memory

should be added to the cell state. The new generated memory

is defined by

Finally the output gate

controls what information will be forwarded from the actual cell state to the hidden state and thus to the actual output of the cell. The actual cell state and hidden states are defined by the following formulas

Where * is indicating an element-wise multiplication.

3.3. Applied Topology

As stated before, this work proposes a combination of a 1-D CNN and LSTM neural networks.

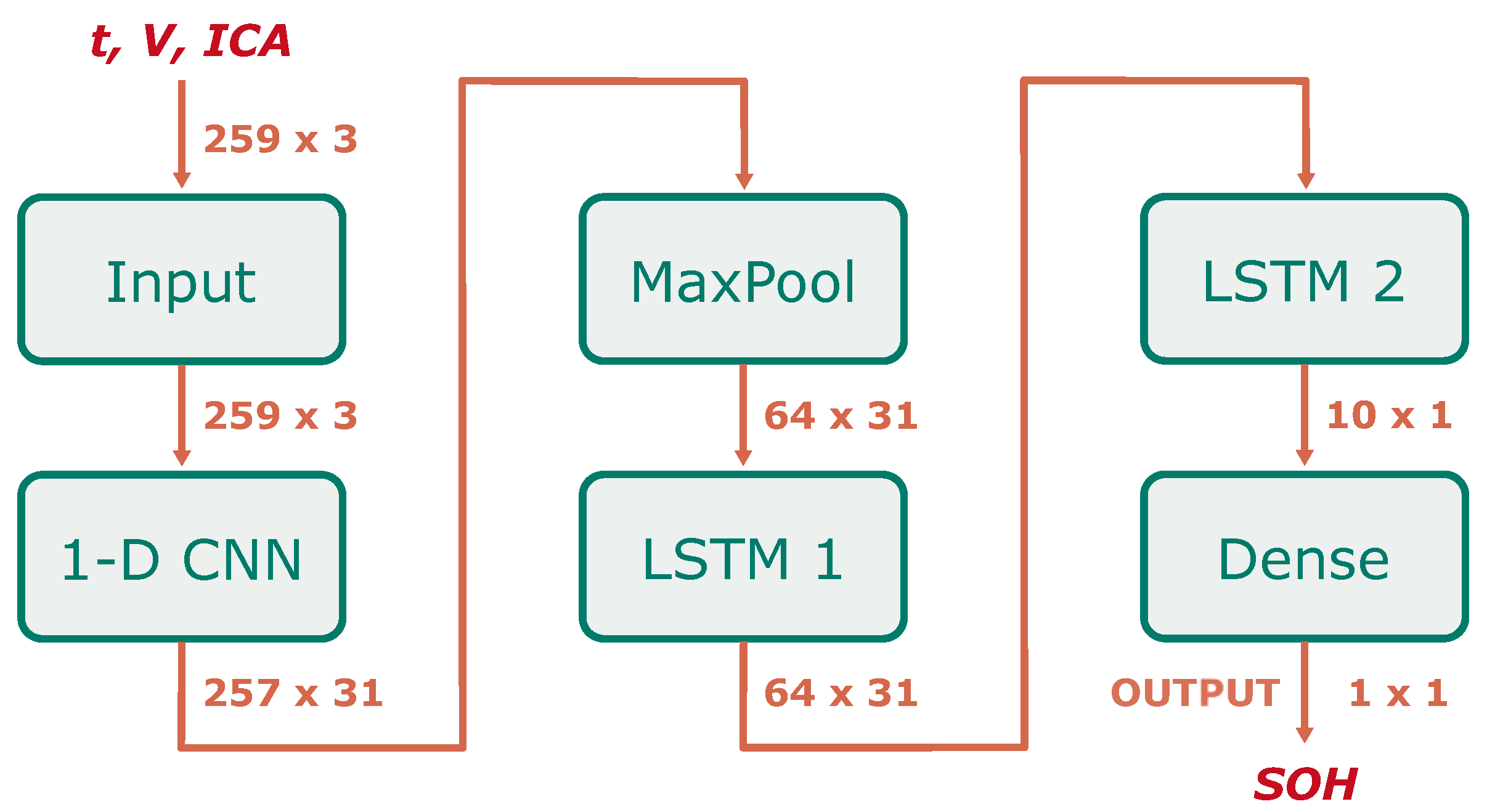

Figure 4 depicts a schematic representation of the applied network topology, along with the corresponding input and output dimensionality for each layer.

The selected input features from the partial charging curves (time, voltage and IC) are processed by the 1-D CNN layer to extract additional features. Subsequently, a one-dimensional maximum pooling layer (1-D MaxPooling) is used to reduce the computational burden of further processing and the overall storage requirements of the neural network by downsampling the resulting multivariate time series. The result is then processed by two sequential LSTM layers, followed by a dense layer consisting of a single node and a linear activation function which outputs the predicted SOH.

3.4. Model Implementation and Training

Keras (version 2.6.0), an open-source deep learning library for Python (version 3.9.7) with TensorFlow (version 2.6.3) as a backend, is used for the implementation and training of the above described neural network. Keras is a high-level API that provides all common deep learning layers a variety of optimisers and a model framework for compiling and training. The "Adamax" optimiser with mean-squared error (MSE) as a loss function, is applied for training. Regularisation is implemented by a dropout for each LSTM layer to prevent the update of randomly chosen weights after a training step. Dropout decreases the chance of overfitting the network to the training data, thus enhancing the generalisation ability of the model.

Optuna (version 2.10.0), an automated hyperparameter optimisation framework, was utilized to fine-tune a selected set of hyperparameters for both the model and training process.

Table 3 lists the hyperparameters which resulted in the highest prediction accuracy.

4. Results and Discussion

In order to assess the quality of predictions generated by the trained model, three fundamental metrics are employed. The first one being the simple absolute error (AE), which quantifies the absolute difference between predicted and observed values for each individual prediction. The second metric is the mean absolute error (MAE), computed as the arithmetic mean of all AE within a set of predictions. Lastly, the root-mean-square error (RMSE) is utilised, which represents the square root of the quadratic mean of the differences between predicted and observed values. Both MAE and RMSE quantitatively measure the model’s accuracy, whereas the RMSE is more sensitive to outliers. All used metrics indicate better model accuracy with lower values and are defined as follows

where

n is the number of total samples,

the predicted and

y the measured SOH in percent.

The proposed model will be validated under consideration of two major aspects. First, the determination of the general model performance with respect to the train-validation-test split of the dataset. Secondly, its robustness against different aging scenarios encompassed in the dataset, which is conducted in a cross-validation manner.

4.1. General Model Performance

The dataset described in

Section 2.1 is randomly partitioned into three defined subsets. This train-validation-test split (80%-10%-10%) is used to determine the general performance of the model. The first subset is used for model training. The validation subset is used to identify potential issues like overfitting during the training process and serves as a target for fine-tuning the hyperparameters. The test subset is not used in the whole training and optimisation process and hence is most representative of the model`s performance and generalisation ability.

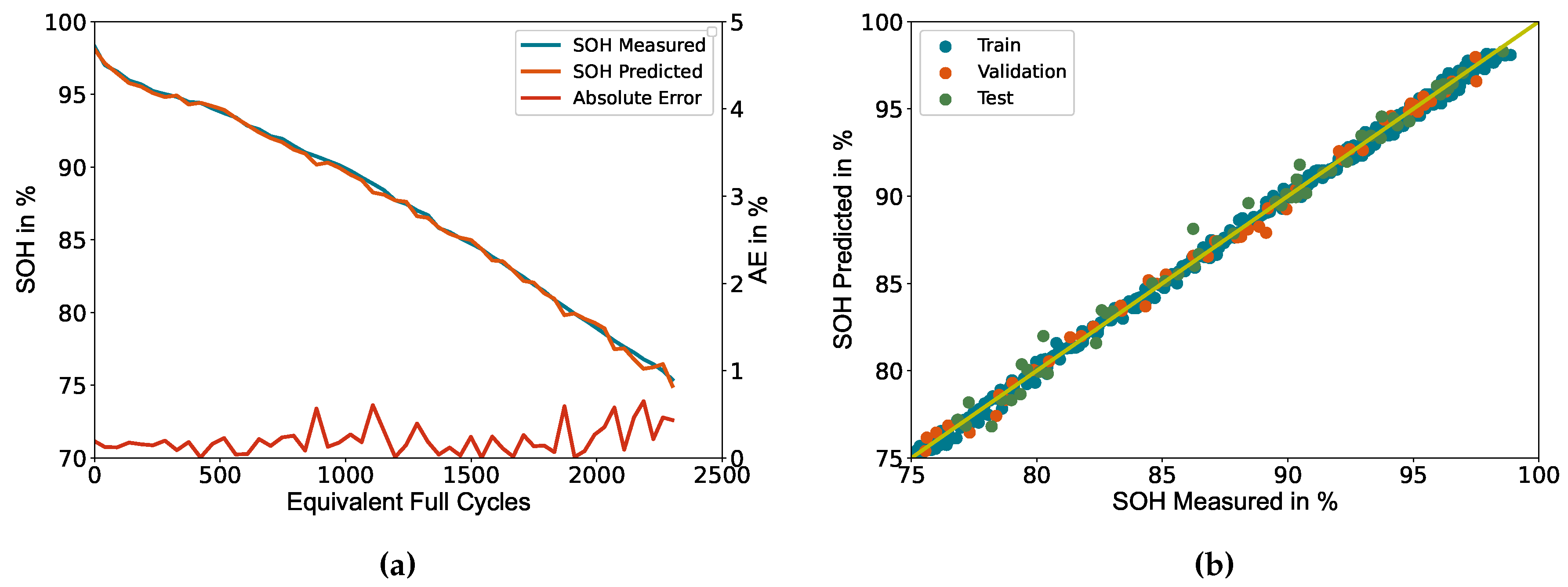

Figure 5(a) depicts an exemplary representation of the measured and predicted SOH based on the data of cell number 6, along with the absolute error associated with each data point. Notably, the absolute error exhibits a marginal inclination as the SOH decreases but never exceeds the threshold of 1%.

Figure 5(b) shows the deviation between measured and predicted SOH for each datapoint of the dataset separated by the subsets. The yellow line represents an optimal prediction. The deviation shows a homogeneous distribution across all subsets, indicating a high generalisation ability. However, a slight elevation in deviation, accompanied by a rise in the number of outliers, is observed for predictions below SOH = 90%, particularly within the test subset. The corresponding metrics for each subset are listed in

Table 4.

4.2. Robustness against Aging Scenarios

To determine the robustness of the model against different ageing mechanisms, a cross-validation approach over the applied ageing scenarios is employed. For each iteration, the data from a single ageing scenario is designated as the test set, while the data of all remaining scenarios is used for model training. This process is repeated for each ageing scenario listed in

Table 2, except for the calendric aged cells (scenario 8-10). The calendric aged cells are considered as one scenario due to their similar ageing mechanisms.

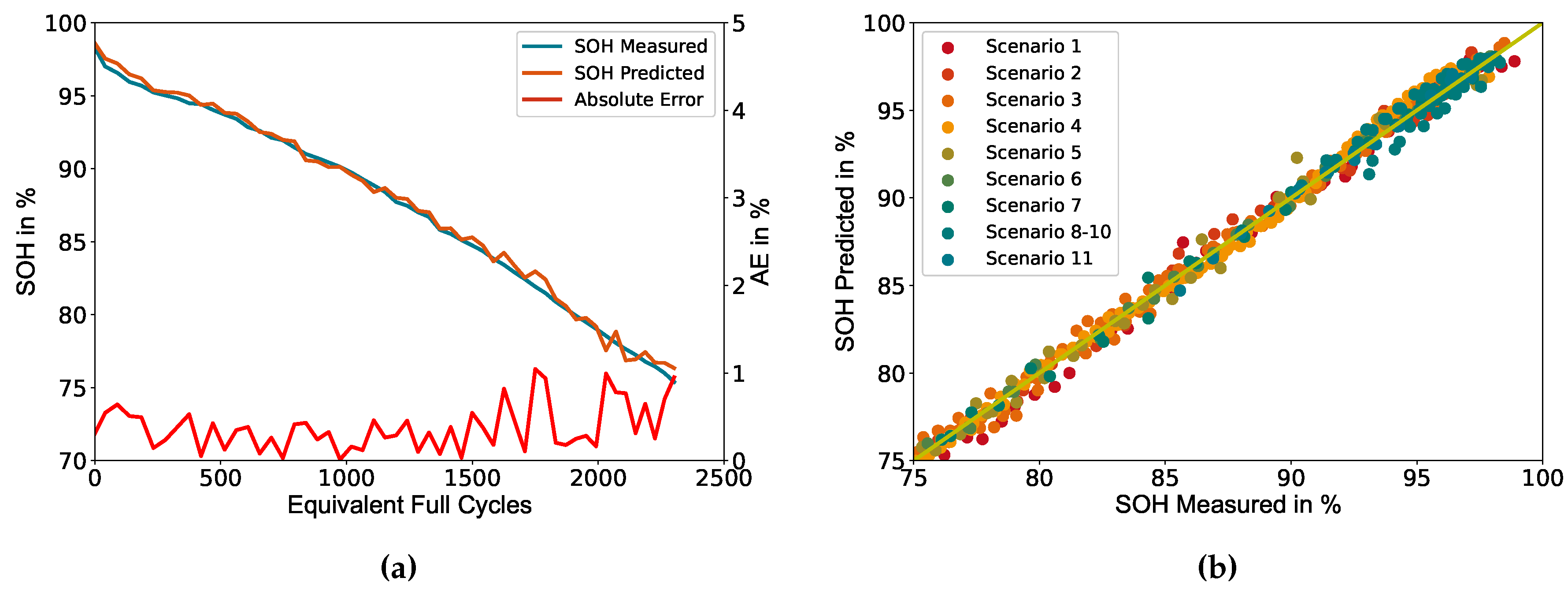

The results of the cross-validation are shown in

Figure 6 and the corresponding metrics for each scenario are listed in

Table 5. Same as for the train-validation-test split,

Figure 6(a) shows the deviation between measured and predicted SOH for cell number 6, achieving comparable results with a slightly increased absolute error for all predictions but always staying below the threshold of 1%.

Figure 6(b) shows the deviation between measured and predicted SOH of the test set for each iteration (scenario) of the cross-validation. The results show a similar behaviour as the train-validation-test split with a homogeneous distribution of the deviation across all iterations, which indicates a high robustness of the model against different ageing scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This work proposes a storage and performance optimised deep learning model to predict the capacity based SOH using time series of raw sensor data from time, voltage and IC of partial charging curves under constant current condition. The model combines a 1-D CNN to extract additional features from the raw sensor data in order to boost prediction accuracy and two sequential LSTM layers to capture long-term dependencies present in the resulting multivariate time series. A 1-D MaxPooling layer is applied to reduce the length of the resulting time series from the 1-D CNN, resulting in lower computational burden and required storage for the subsequent LSTM layers, making the model suitable for small embedded devices found in modern BMS. The model has been cross-validated on different aging scenarios with an average MAE = 0.418% and RMSE = 0.531%, promising accurate SOH predictions of LIBs at varying usage and environmental conditions in a real world application. A rise of prediction accuracy is expected for larger datasets used for the training process.

The primary limitation of the proposed methodology lies in its exclusive applicability to scenarios where a controlled charging phase under constant current condition is feasible. In such instances, the acquisition of data can take place without additional interventions in the battery system’s operation. Additionally, the generation of training data has to be repeated for any additional cell type or applied c-rate, resulting in expensive and time consuming laboratory work.

If the concept of transfer learning can be applied to reduce these experimental expenses, as well as to prove the suitability of the proposed methodology for other cell chemistries like lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) will be the scope of future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S.; software, M.S.; validation, M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S.; resources, J.K.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, J.K. and M.S.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, J.K.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK), grant number 16KN086221 (Liobat). The authors are responsible for the content. The work was further supported by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Fund of TU Berlin.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author provided the initial authorship and conceptual design of this manuscript, with subsequent refinements and enhancements implemented by AI-based tools such as ChatGPT, DeepL, and Grammarly. It is emphasized that all presented ideas and arguments are the author’s own, and the AI tools were solely employed for linguistic and stylistic improvements. We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Fund of TU Berlin.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOH |

State of Health |

| LIBs |

Lithium-ion batteries |

| ICA |

Incremental Capacity Analysis |

| IC |

Incremental Capacity |

| DNN |

Deep Neural Network |

| LSTM |

Long short-term memory neural network |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| 1-D CNN |

1-dimensional convolution neural network |

| 1-D MaxPooling |

1-dimensional maximum pooling |

| BMS |

Battery Management System |

| OCV |

Open Circuit Voltage |

| DOD |

Depth Of Discharge |

| CC |

Constant Current |

| AE |

Absolute Error |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

References

- Vetter, J.; Novák, P.; Wagner, M.R.; Veit, C.; Möller, K.C.; Besenhard, J.O.; Winter, M.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M.; Vogler, C.; Hammouche, A. Ageing mechanisms in lithium-ion batteries 2005. 147, 0378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Abdel-Monem, M.; Gopalakrishnan, R.; Berecibar, M.; Nanini-Maury, E.; Omar, N.; van den Bossche, P.; van Mierlo, J. A quick on-line state of health estimation method for Li-ion battery with incremental capacity curves processed by Gaussian filter 2018. 373, 0378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviere, E.; Sari, A.; Venet, P.; Meniere, F.; Bultel, Y. Innovative Incremental Capacity Analysis Implementation for C/LiFePO4 Cell State-of-Health Estimation in Electrical Vehicles 2019. 5, 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantenbein, S.; Schönleber, M.; Weiss, M.; Ivers-Tiffée, E. Capacity Fade in Lithium-Ion Batteries and Cyclic Aging over Various State-of-Charge Ranges 2019. 11, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, D.; Meiler, M.; Steiner, K.; Wimmer, C.; Soczka-Guth, T.; Sauer, D.U. Characterization of high-power lithium-ion batteries by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. I. Experimental investigation 2011. 196, 0378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Stimming, U.; Lee, A.A. Identifying degradation patterns of lithium ion batteries from impedance spectroscopy using machine learning 2020. 11. [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Zhang, T.; Yu, H.; Kang, Y. State-of-health estimation of lithium-ion battery packs in electric vehicles based on genetic resampling particle filter 2016. 182, 0306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Hu, X.; Ma, H.; Li, S.E. Combined State of Charge and State of Health estimation over lithium-ion battery cell cycle lifespan for electric vehicles 2015. 273, 0378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A.; Marcicki, J.; Onori, S.; Rizzoni, G.; Yang, X.G.; Miller, T. Electrochemical Model-Based State of Charge and Capacity Estimation for a Composite Electrode Lithium-Ion Battery 2015. p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Wang, G.; Jiang, J. Co-estimation of state-of-charge, capacity and resistance for lithium-ion batteries based on a high-fidelity electrochemical model 2016. 180, 0306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, D.; Saxena, S.; Robu, V.; Pecht, M.; Flynn, D. Machine learning pipeline for battery state-of-health estimation 2021. 3. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Ruan, H.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; He, H. Multistage State of Health Estimation of Lithium-Ion Battery With High Tolerance to Heavily Partial Charging 2022. 37. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sengupta, N.; Dechent, P.; Howey, D.; Annaswamy, A.; Sauer, D.U. Online capacity estimation of lithium-ion batteries with deep long short-term memory networks 2021. 482, 0378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y. Method of Predicting SOH and RUL of Lithium-Ion Battery Based on the Combination of LSTM and GPR 2022. 14, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.R.; Birkl, C.R.; Osborne, M.A.; Howey, D.A. Gaussian Process Regression for In Situ Capacity Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries 2019. 15. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Huang, K.; Hu, X. A state-of-health estimation method of lithium-ion batteries based on multi-feature extracted from constant current charging curve 2021. 36, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klass, V.; Behm, M.; Lindbergh, G. A support vector machine-based state-of-health estimation method for lithium-ion batteries under electric vehicle operation 2014. 270, 0378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Deng, H.; Hu, W. State of health estimation for lithium battery random charging process based on CNN-GRU method 2023. 9, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Kang, L. ; Di Xie. Online State of Health Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Charging Process and Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Network 2023. 9, 9020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Xiao, F.; Li, C.; Yang, G.; Tang, X. A novel deep learning framework for state of health estimation of lithium-ion battery 2020. 32, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, F.; Hematty, P.; Schmitz, M.; Kowal, J. Neural Network Architecture for Determining the Aging of Stationary Storage Systems in Smart Grids 2023. 16, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Qin, C.; Lu, L.; Han, X.; Ouyang, M. A novel capacity estimation method based on charging curve sections for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles 2019. 185, 0360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Ouyang, M.; Lu, L.; Li, J.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Z. A comparative study of commercial lithium ion battery cycle life in electrical vehicle: Aging mechanism identification 2014. 251, 0378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail Fawaz, H.; Forestier, G.; Weber, J.; Idoumghar, L.; Muller, P.A. Deep learning for time series classification: a review 2019. 33. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).