Submitted:

27 March 2024

Posted:

28 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. New Medical Treatments for HFrEF

2.1. Sodium-Glucose Transport Proteins 2 Inhibitors

- -) blood pressure reduction: an increase in urine glucose excretion as well as reduced sodium reabsorption have been proposed to explain the reducing effect on blood pressure. SGLT2 inhibitors impacted on weight loss[4]. They also act on cholesterol levels by showing low increase in HDL, LDL and total cholesterol levels, and a small decrease in triglycerides[5]. However, improvement of these secondary risk factors of cardiovascular disease are unlikely to completely explain the marked benefit seen with the use of these drugs in patients with HFrEF [6]. It has been hypothesized that other mechanisms could contribute to the beneficial effects observed in HF patients:

- -) effect on cardiac remodeling and contractility: previous studies have demonstrated that empagliflozin led to a significant reduction of diastolic tension without altering the systolic contractile force. Empagliflozin decreases myofilament stiffness in human myocardium through an enhanced phosphorylation process of titin due to improvement of the nitric oxide (NO) pathway[7].

- -) reduction of inflammation: several studies showed that SGLT2 inhibitors have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties[8]. Dapagliflozin reduced the inflammasome and fibrosis in mouse models of type 2 diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction[9] and empagliflozin decreases oxidative stress, associated with metabolic changes, in mice after myocardial infarction [10].

- -) cardiorenal function improvement: SGLT2 inhibitors cause a natriuretic effect favoring sodium excretion by the distal renal tubules inducing a vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriolar vessel and finally restoring the impaired tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. As a result, the reduced blood flow elicits the release of erythropoietin [11].

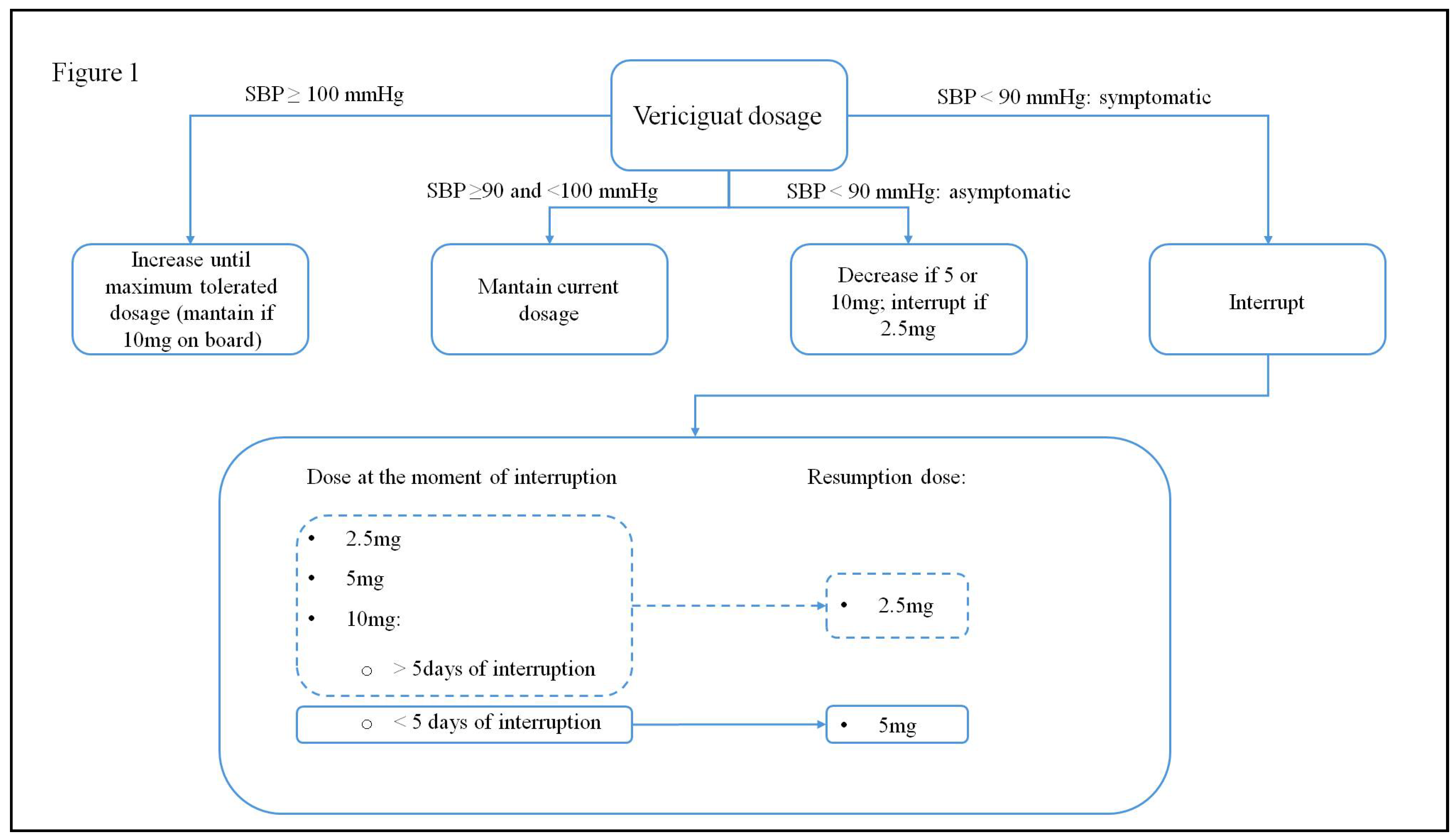

2.2. Vericiguat

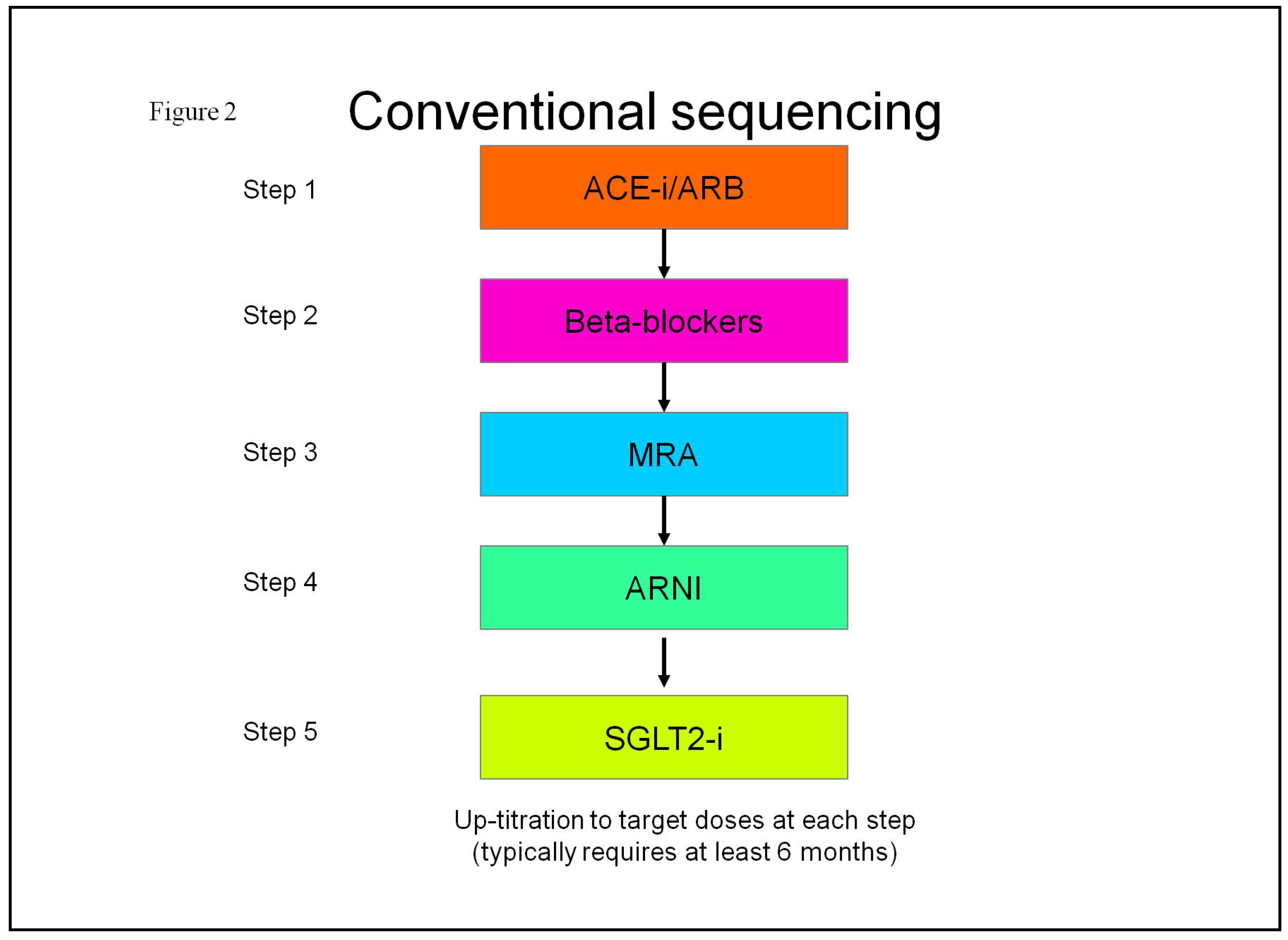

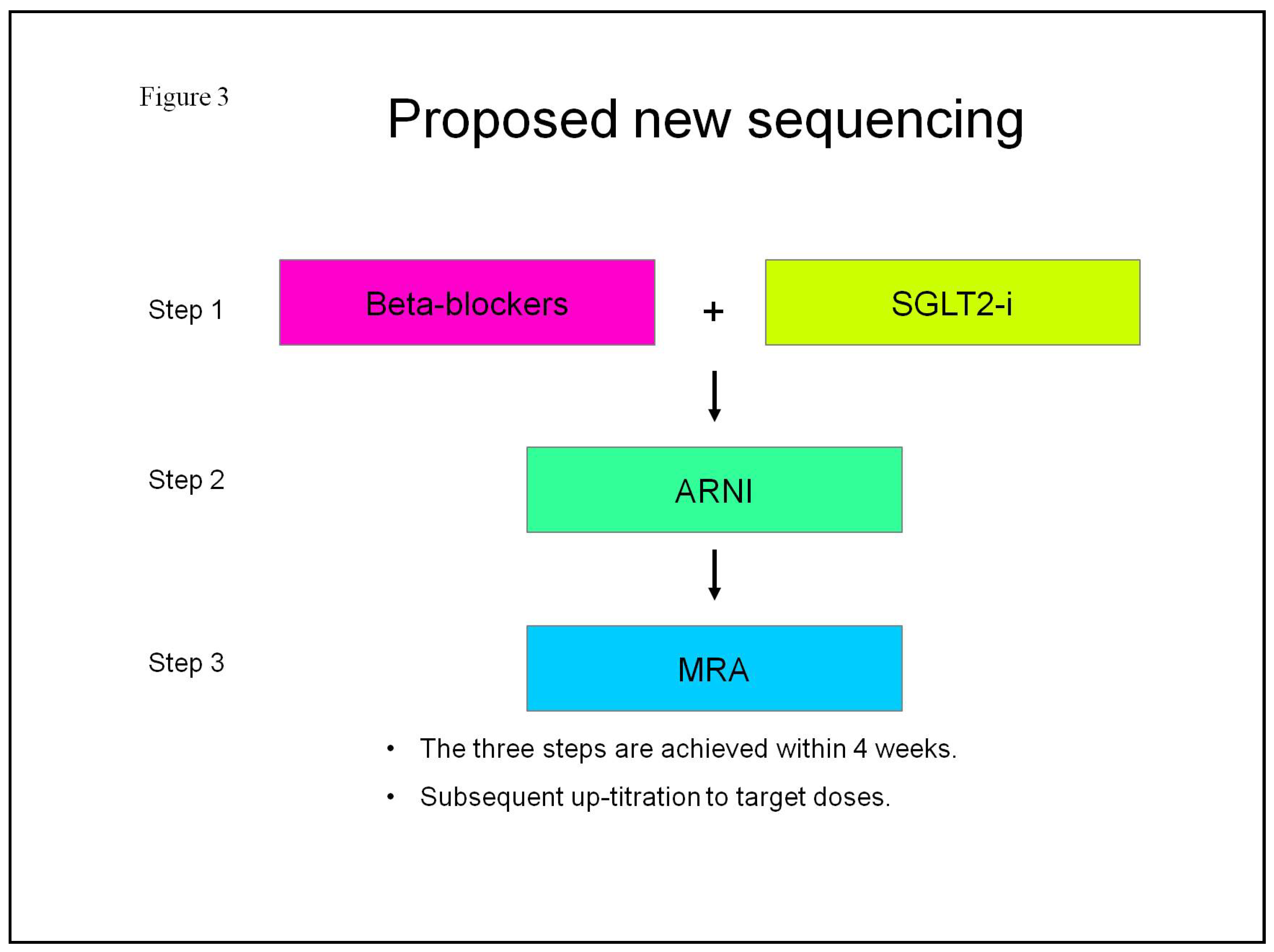

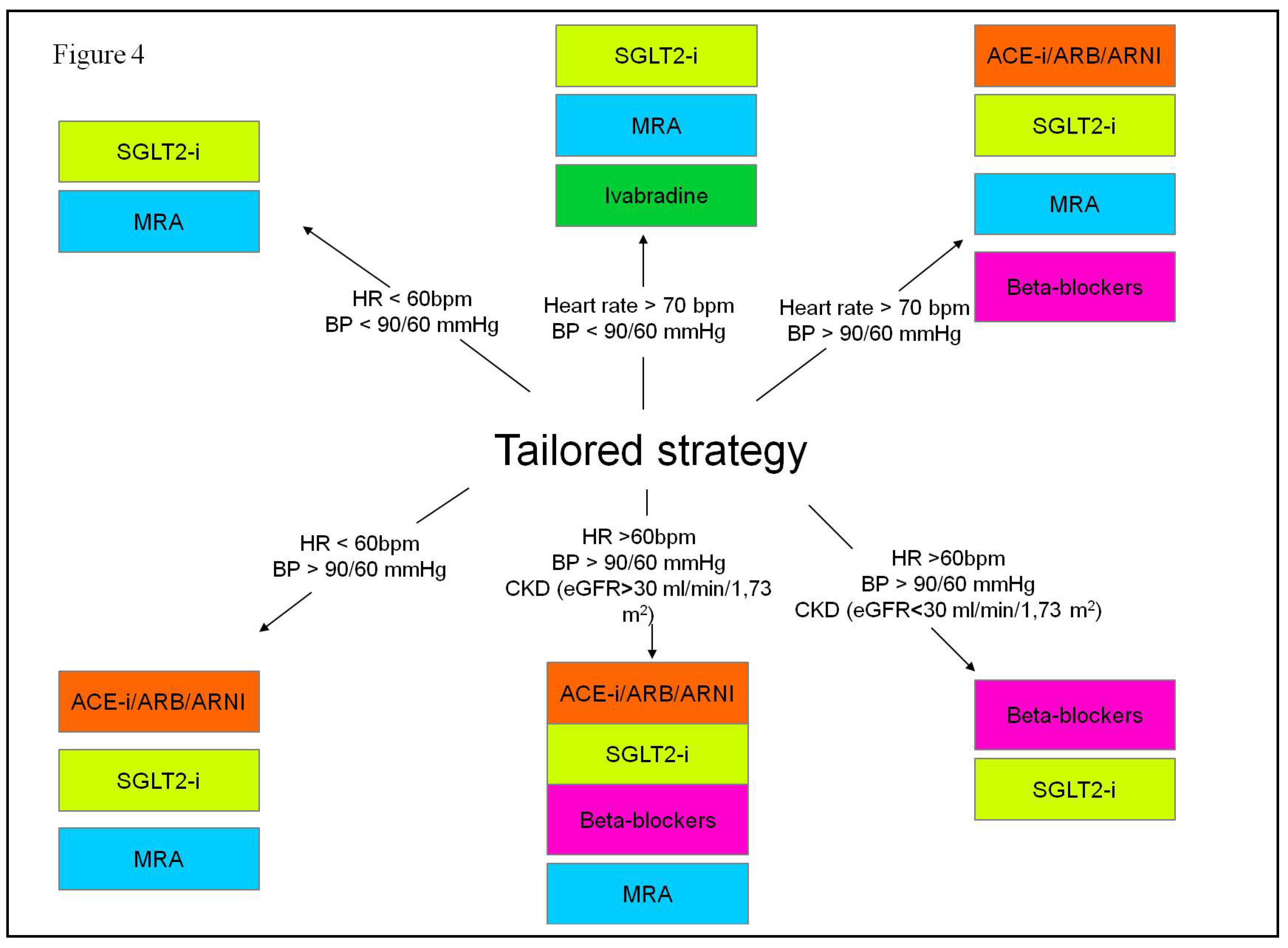

2.3. Pharmacological Treatment Strategies for Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

3. New Devices for Monitor or Treat HFrEF Patients

3.1. Cardio-Microelectromechanical Systems

3.2. Cardiac Contractility Modulation

- LVEF ≥ 25% and ≤ 45%.

- NYHA class II and III despite optimal medical treatment.

- QRS duration < 130 ms or not responder to cardiac resynchronization treatment.

- Left ventricular end diastolic diameter < 70 mm.

- Low arrhythmic burden (<8900 premature ventricular complexes in 24 h).

- No acute coronary events in the last three months.

- No recent hospitalizations (in the last month).

- Absence of comorbidities conditioning a life expectancy lower than one year.

3.3. Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing

3.4. Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillators

3.5. Ultrafiltration for Acute Decompensated HF

4. Conclusions

5. Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ziaeian, B.; Fonarow, G.C. Epidemiology and aetiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016, 13, 368–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.; Rassekh, N.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy for the Treatment of Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Drugs 2023, 83, 747–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Rev Esp Cardiol 2016, 69, 1167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cowie, M.R.; Fisher, M. SGLT2 inhibitors: mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit beyond glycaemic control. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020, 17, 761–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbour, S.; Seufert, J.; Scheen, A.; et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A pooled analysis of safety data from phase IIb/III clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018, 20, 620–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabel, S.; Hamdani, N.; Luedde, M.; et al. SGLT2 Inhibitors and Their Mode of Action in Heart Failure-Has the Mystery Been Unravelled? Curr Heart Fail Rep 2021, 18, 315–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabel, S.; Wagner, S.; Bollenberg, H.; et al. Empagliflozin directly improves diastolic function in human heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2018, 20, 1690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Atkin, S.L.; Butler, A.E.; et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors and oxidative stress: An update. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 3231–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Bajaj, M.; Yang, H.C.; et al. SGLT-2 Inhibition with Dapagliflozin Reduces the Activation of the Nlrp3/ASC Inflammasome and Attenuates the Development of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy in Mice with Type 2 Diabetes. Further Augmentation of the Effects with Saxagliptin, a DPP4 Inhibitor. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2017, 31, 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurista, S.R.; Sillje, H.H.W.; Oberdorf-Maass, S.U.; et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibition with empagliflozin improves cardiac function in non-diabetic rats with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail 2019, 21, 862–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, D.Z.; Perkins, B.A.; Soleymanlou, N.; et al. Renal hemodynamic effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2014, 129, 587–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 2117–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, B.; Perkovic, V.; Matthews, D.R. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 347–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1413–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 3599–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79, 1757–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.; Usman, M.S.; Anstrom, K.J.; et al. Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction across the risk spectrum. Eur J Heart Fail 2022, 24, 2029–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; Anguita-Sanchez, M.; Bayes-Genis, A.; et al. Vericiguat in heart failure: From scientific evidence to clinical practice. Rev Clin Esp (Barc) 2022, 222, 359–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.N.; Diez, J.; Gustafsson, F.; et al. Practical Patient Care Considerations With Use of Vericiguat After Worsening Heart Failure Events. J Card Fail 2023, 29, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillo, M.E.; Ayalasomayajula, S.; Blaustein, R.O.; et al. Vericiguat, a novel sGC stimulator: Mechanism of action, clinical, and translational science. Clin Transl Sci 2023, 16, 2458–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahana, U.; Wehland, M.; Simonsen, U.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Vericiguat on Patients with Heart Failure. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P.W.; Pieske, B.; Anstrom, K.J.; et al. Vericiguat in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1883–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieske, B.; Pieske-Kraigher, E.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. Effect of vericiguat on left ventricular structure and function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The VICTORIA echocardiographic substudy. Eur J Heart Fail 2023, 25, 1012–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. Corrigendum to: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 4901. [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghiade, M.; Shah, A.N.; Vaduganathan, M.; et al. Recognizing hospitalized heart failure as an entity and developing new therapies to improve outcomes: academics', clinicians', industry's, regulators', and payers' perspectives. Heart Fail Clin 2013, 9, 285–90, v. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, K.; Komajda, M.; Bohm, M.; et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2010, 376, 875–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauersachs, J. Heart failure drug treatment: the fantastic four. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 681–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Packer, M. How Should We Sequence the Treatments for Heart Failure and a Reduced Ejection Fraction?: A Redefinition of Evidence-Based Medicine. Circulation 2021, 143, 875–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosano, G.M.C.; Moura, B.; Metra, M.; et al. Patient profiling in heart failure for tailoring medical therapy. A consensus document of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2021, 23, 872–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.R.; Roalfe, A.K.; Adoki, I.; et al. Survival of patients with chronic heart failure in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2019, 21, 1306–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pour-Ghaz, I.; Hana, D.; Raja, J.; et al. CardioMEMS: where we are and where can we go? Ann Transl Med 2019, 7, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

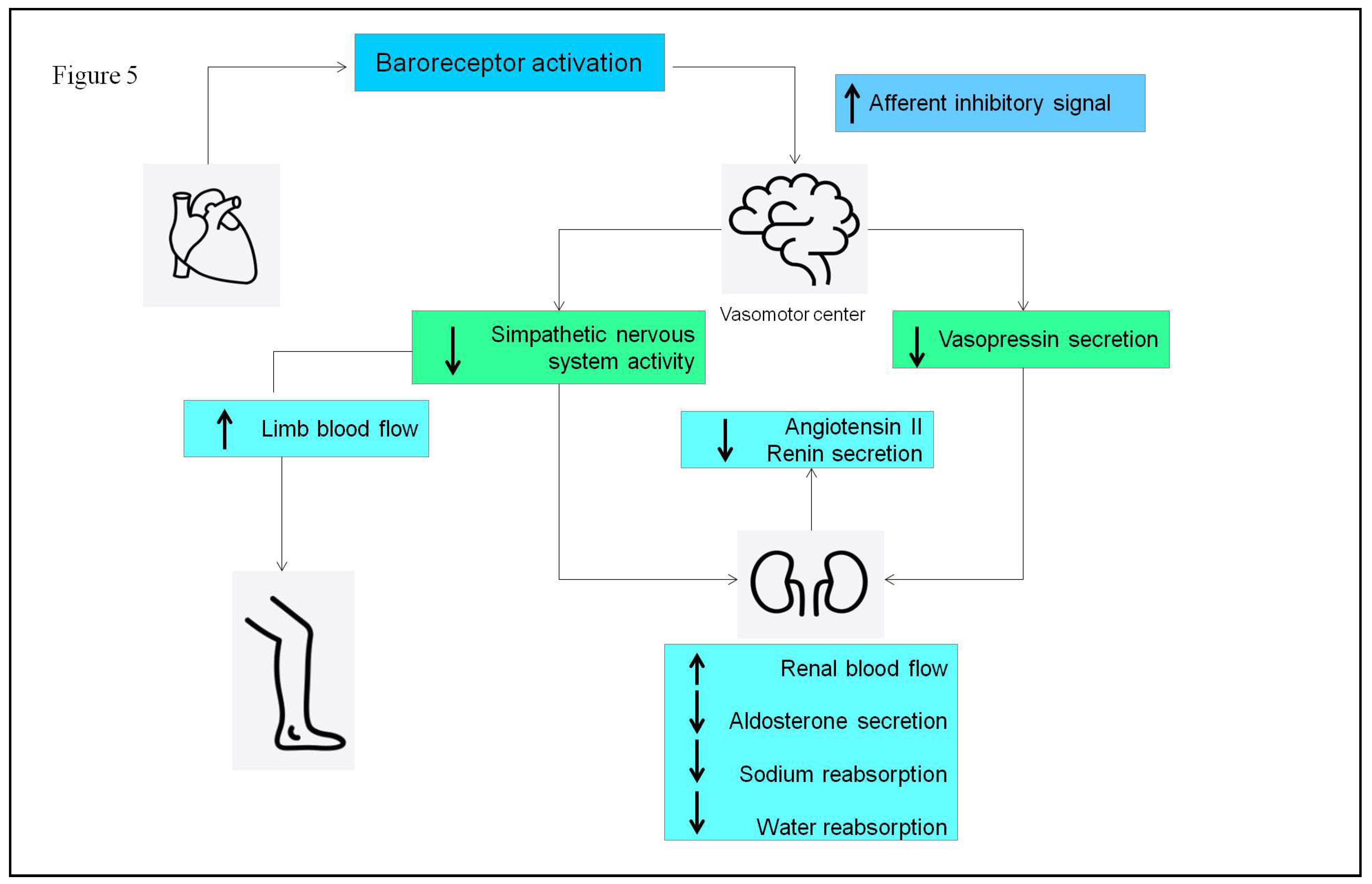

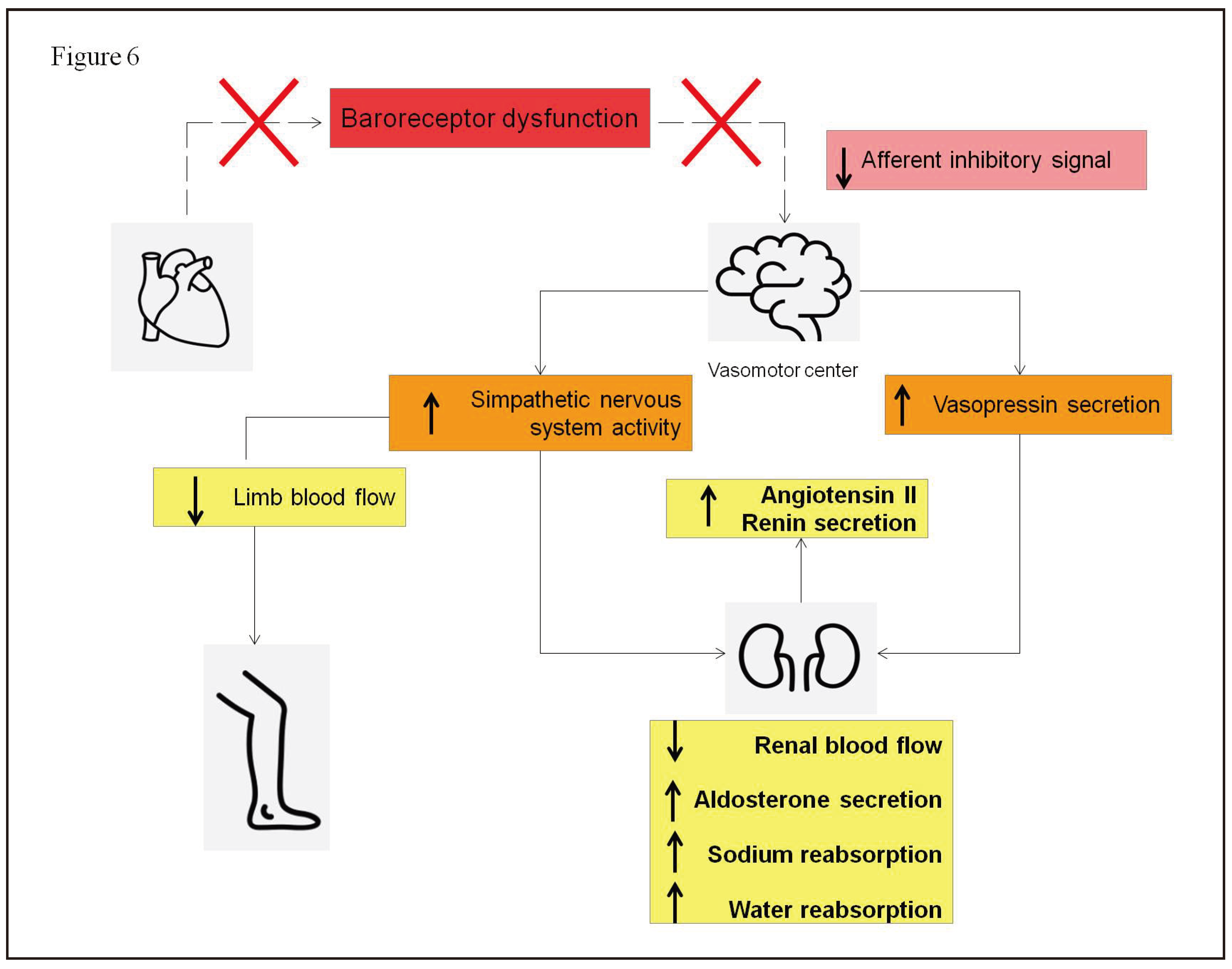

- Linden, R.J. Atrial reflexes and renal function. Am J Cardiol 1979, 44, 879–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibner-Dunlap, M.E.; Thames, M.D. Control of sympathetic nerve activity by vagal mechanoreflexes is blunted in heart failure. Circulation 1992, 86, 1929–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, M.; Magri, P.; Rao, M.A.; et al. Intrarenal determinants of sodium retention in mild heart failure: effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Hypertension 1997, 30, 168–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, W.T.; Adamson, P.B.; Bourge, R.C.; et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 658–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, W.T.; Stevenson, L.W.; Bourge, R.C.; et al. Sustained efficacy of pulmonary artery pressure to guide adjustment of chronic heart failure therapy: complete follow-up results from the CHAMPION randomised trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 453–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.R.; Stevenson, L.W.; Adamson, P.B.; et al. Interventions Linked to Decreased Heart Failure Hospitalizations During Ambulatory Pulmonary Artery Pressure Monitoring. JACC Heart Fail 2016, 4, 333–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenfeld, J.; Zile, M.R.; Desai, A.S.; et al. Haemodynamic-guided management of heart failure (GUIDE-HF): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 41. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. J Card Fail 2022, 28, e1–e167. [CrossRef]

- Angermann, C.E.; Assmus, B.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Pulmonary artery pressure-guided therapy in ambulatory patients with symptomatic heart failure: the CardioMEMS European Monitoring Study for Heart Failure (MEMS-HF). Eur J Heart Fail 2020, 22, 1891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komajda, M.; Bohm, M.; Borer, J.S.; et al. Incremental benefit of drug therapies for chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2018, 20, 1315–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskovitch, J.; Voskoboinik, A. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: a comprehensive review. Minerva Med 2019, 110, 121–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, W.T. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy and Cardiac Contractility Modulation in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure: How to Select the Right Candidate? Heart Fail Clin 2021, 17, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, C.M.; Kahwash, R.; Abraham, W.T. Optimizer Smart in the treatment of moderate-to-severe chronic heart failure. Future Cardiol 2020, 16, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappannoli, L.; Scacciavillani, R.; Rocco, E.; et al. Cardiac contractility modulation for patient with refractory heart failure: an updated evidence-based review. Heart Fail Rev 2021, 26, 227–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anker, S.D.; Borggrefe, M.; Neuser, H.; et al. Cardiac contractility modulation improves long-term survival and hospitalizations in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2019, 21, 1103–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschope, C.; Van Linthout, S.; Spillmann, F.; et al. Cardiac contractility modulation signals improve exercise intolerance and maladaptive regulation of cardiac key proteins for systolic and diastolic function in HFpEF. Int J Cardiol 2016, 203, 1061–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R.; Samara, M.A.; Feldman, D.S. Cardiac contractility modulation therapy in advanced systolic heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2013, 10, 584–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschyk, J.; Nagele, H.; Heinz-Kuck, K.; et al. Cardiac contractility modulation treatment in patients with symptomatic heart failure despite optimal medical therapy and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). Int J Cardiol 2019, 277, 173–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tint, D.; Florea, R.; Micu, S. New Generation Cardiac Contractility Modulation Device-Filling the Gap in Heart Failure Treatment. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchese, P.; Gennaro, F.; Mazzotta, G. Cardiac Contractility Modulation Therapy in Patients with Amyloid Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure, Case Report, Review of the Biophysics of CCM Function, and AMY-CCM Registry Presentation. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschope, C.; Kherad, B.; Klein, O.; et al. Cardiac contractility modulation: mechanisms of action in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and beyond. Eur J Heart Fail 2019, 21, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, M.; Rastogi, S.; Gupta, R.C.; et al. Therapy with cardiac contractility modulation electrical signals improves left ventricular function and remodeling in dogs with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007, 49, 2120–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, M.; Kassiotis, C.; Razeghi, P.; et al. Return to the fetal gene program protects the stressed heart: a strong hypothesis. Heart Fail Rev 2007, 12, 331–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, M.; Goodman, R. A mechanism for stimulation of biosynthesis by electromagnetic fields: charge transfer in DNA and base pair separation. J Cell Physiol 2008, 214, 20–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, S.; et al. Enhancing myocardial function with cardiac contractility modulation: potential and challenges. ESC Heart Fail 2024, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Ahmad, S.; Peltz, J.; et al. Left bundle branch area pacing vs biventricular pacing for cardiac resynchronization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm O2 2023, 4, 671–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, H.; Jastrzebski, M.; Cano, O.; et al. EHRA clinical consensus statement on conduction system pacing implantation: executive summary. Endorsed by the Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS) and Latin-American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace 2023, 25, 1237–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, C.; Li, J.; et al. An individualized criterion for left bundle branch capture in patients with a narrow QRS complex. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, B.; Sharma, P.S.; Cano, O.; et al. Arrhythmic Risk in Biventricular Pacing Compared With Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing: Results From the I-CLAS Study. Circulation 2024, 149, 379–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraman, P. Left Bundle Branch Pacing Optimized Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: A Novel Approach. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021, 7, 1076–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncker, D.; Konig, T.; Hohmann, S. Avoiding Untimely Implantable Cardioverter/Defibrillator Implantation by Intensified Heart Failure Therapy Optimization Supported by the Wearable Cardioverter/Defibrillator-The PROLONG Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Ammendola, E.; Ziacchi, M.; et al. Effect of SAcubitril/Valsartan on left vEntricular ejection fraction and on the potential indication for Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator in primary prevention: the SAVE-ICD study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2021, 77, 1835–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olgin, J.E.; Pletcher, M.J.; Vittinghoff, E.; et al. Wearable Cardioverter-Defibrillator after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 1205–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, R.; Combes, N.; Defaye, P.; et al. Wearable cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with a transient risk of sudden cardiac death: the WEARIT-France cohort study. Europace 2021, 23, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliodromitis, K.; Balogh, Z.; Triposkiadis, F.; et al. Assessing physical activity with the wearable cardioverter defibrillator in patients with newly diagnosed heart failure. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1176710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, F.; D'Onofrio, A.; De Ruvo, E.; et al. Decongestive treatment adjustments in heart failure patients remotely monitored with a multiparametric implantable defibrillators algorithm. Clin Cardiol 2022, 45, 670–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.B.; Sharbaugh, M.S.; Thoma, F.W.; et al. Trends in hospitalization for congestive heart failure, 1996-2009. Clin Cardiol 2017, 40, 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, P.C.; Onat, D.; Harxhi, A.; et al. Peripheral venous congestion causes inflammation, neurohormonal, and endothelial cell activation. Eur Heart J 2014, 35, 448–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Testani, J.; Collins, S. Diuretic Resistance in Heart Failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2019, 16, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voors, A.A.; Davison, B.A.; Teerlink, J.R.; et al. Diuretic response in patients with acute decompensated heart failure: characteristics and clinical outcome--an analysis from RELAX-AHF. Eur J Heart Fail 2014, 16, 1230–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazory, A.; Elkayam, U. Cardiorenal interactions in acute decompensated heart failure: contemporary concepts facing emerging controversies. J Card Fail 2014, 20, 1004–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, W.F.; Costanzo, M.R.; De Marco, T.; et al. Impact of intravenous loop diuretics on outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: insights from the ADHERE registry. Cardiology 2009, 113, 12–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.R.; Jessup, M. Treatment of congestion in heart failure with diuretics and extracorporeal therapies: effects on symptoms, renal function, and prognosis. Heart Fail Rev 2012, 17, 313–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazory, A. Cardiorenal syndrome: ultrafiltration therapy for heart failure--trials and tribulations. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013, 8, 1816–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marenzi, G.; Lauri, G.; Grazi, M.; et al. Circulatory response to fluid overload removal by extracorporeal ultrafiltration in refractory congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001, 38, 963–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.R.; Guglin, M.E.; Saltzberg, M.T.; et al. Ultrafiltration versus intravenous diuretics for patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007, 49, 675–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, B.A.; Goldsmith, S.R.; Lee, K.L.; et al. Ultrafiltration in decompensated heart failure with cardiorenal syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012, 367, 2296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.R.; Negoianu, D.; Jaski, B.E.; et al. Aquapheresis Versus Intravenous Diuretics and Hospitalizations for Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail 2016, 4, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Agrawal, N.; Kazory, A. Defining the role of ultrafiltration therapy in acute heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 2016, 21, 611–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boriani, G.; De Ponti, R.; Guerra, F.; et al. Sinergy between drugs and devices in the fight against sudden cardiac death and heart failure. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021, 28, 110–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teerlink, J.R.; Diaz, R.; Felker, G.M.; et al. Omecamtiv Mecarbil in Chronic Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: Rationale and Design of GALACTIC-HF. JACC Heart Fail 2020, 8, 329–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, F.I.; Hartman, J.J.; Elias, K.A.; et al. Cardiac myosin activation: a potential therapeutic approach for systolic heart failure. Science 2011, 331, 1439–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teerlink, J.R.; Felker, G.M.; McMurray, J.J.; et al. Chronic Oral Study of Myosin Activation to Increase Contractility in Heart Failure (COSMIC-HF): a phase 2, pharmacokinetic, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 2895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayes-Genis, A.; Voors, A.A.; Zannad, F.; et al. Transitioning from usual care to biomarker-based personalized and precision medicine in heart failure: call for action. Eur Heart J 2018, 39, 2793–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.K.; Zhu, J.Q.; Zhang, J.T.; et al. Circulating microRNA: a novel potential biomarker for early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in humans. Eur Heart J 2010, 31, 659–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajcay, N.; Bezak, B.; Segev, A.; et al. Data processing pipeline for cardiogenic shock prediction using machine learning. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1132680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SGLT2-i molecules | Dosage | Frequency | Contraindications | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dapagliflozin | 10 mg | once daily | • Kidney failure (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m2) • History of serious hypersensitivity reaction to drug • Pregnancy or breastfeeding • On dialysis |

• Genital fungal infections • Urinary tract infections • Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis • Dehydration and hypotension • Hypoglycemia when used with insulin or sulfonylurea • Lower limb ulcerations and soft tissue infections • Dyslipidemia |

| Empagliflozin | 10 mg | once daily | • Kidney failure (eGFR < 20 mL/min/1.73m2) • History of serious hypersensitivity reaction to drug • Pregnancy or breastfeeding • On dialysis |

• Genital fungal infections • Urinary tract infections • Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis • Dehydration and hypotension • Hypoglycemia when used with insulin or sulfonylurea • Lower limb ulcerations and soft tissue infections • Dyslipidemia |

| Starting dose | Target dose | |

|---|---|---|

| ACE-i | ||

| Ramipril | 2.5 mg b.i.d. | 5 mg b.i.d. |

| Enalapril | 2.5 mg b.i.d. | 10-20 mg b.i.d. |

| Lisinopril | 2.5-5 mg o.d. | 20-35 mg o.d. |

| ARB | ||

| Valsartan | 40 mg b.i.d. | 160 mg b.i.d. |

| Candesartan | 4 mg o.d. | 32 mg o.d. |

| Losartan | 50 mg o.d. | 150 mg o.d. |

| ARNI | ||

| Sacubitril/Valsartan | 24/26 mg b.i.d. | 97/103 mg b.i.d. |

| MRA | ||

| Spironolactone | 25 mg o.d. | 50 mg o.d. |

| Eplerenone | 25 mg o.d. | 50 mg o.d. |

| Beta-blockers | ||

| Bisoprolol | 1.25 mg o.d. | 10 mg o.d. |

| Nebivolol | 1.25 mg o.d. | 10 mg o.d. |

| Carvedilol | 3.125 mg b.i.d. | 25 mg b.i.d. |

| SGLT2-i | ||

| Dapagliflozin | 10 mg o.d. | 10 mg o.d. |

| Empagliflozin | 10 mg o.d. | 10 mg o.d. |

| Other agents | ||

| Vericiguat | 2.5 mg o.d. | 10 mg o.d. |

| Ivabradine | 5 mg b.i.d. | 7.5 mg b.i.d. |

| Loop diuretics | Extracorporeal Ultrafiltration | |

|---|---|---|

| Neurohormonal activation | Direct neurohormonal activation | No direct neurohormonal activation |

| Removal | Elimination of hypotonic urine | Removal of isotonic plasma water |

| Control of fluid and waste removal | Unpredictable elimination of sodium and water | Precise control of rate and amount of fluid removal |

| Effect on renal function | Development of diuretic agent resistance with prolonged administration | Restoration of diuretic agent responsiveness |

| Effect of plasma components | Risk of hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia | No effect on plasma concentration of potassium and magnesium |

| Anticoagulation | No need for anticoagulation | Need for anticoagulation |

| Extracorporeal circuit | No extracorporeal circuit | Need for extracorporeal circuit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).