1. Introduction

Colloidal drug carriers (also referred to as controlled release systems) are advanced dosage forms utilized for disease diagnosis, prevention and cure. The design rationale is to supply adequate quantity of the medicaments and/or diagnostic agents to the pathological sites (target cells) at the right time frame to attain maximum therapeutic outcome with minimum, or ideally no adverse effect and toxicity. These carrier systems aim to optimize drug administration, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. Drug delivery systems can vary widely in their structure, size, charge, mechanism of action, and applications, thereby meeting different therapeutic needs and serving various patient populations. Lipid and phospholipid-based carriers are gaining increasing attention as drug delivery systems in both industry and research [

1,

2].

At present, there are several FDA-approved products with verified clinical outcomes, which are incorporating lipidic encapsulation technologies [

1,

2]. These carriers improve the bioavailability and efficacy of therapeutic or preventive compounds by encapsulation and / or entrapment and controlled release of hydrophilic, lipophilic and amphipathic molecules and compounds. Furthermore, they can be used for targeting the bioactive formulations to particular cells or tissues in vitro and in vivo [

3]. Based on these significant characteristics, the lipidic carriers, and their related technologies, are being used in the preclinical and clinical research for several decades [

2].

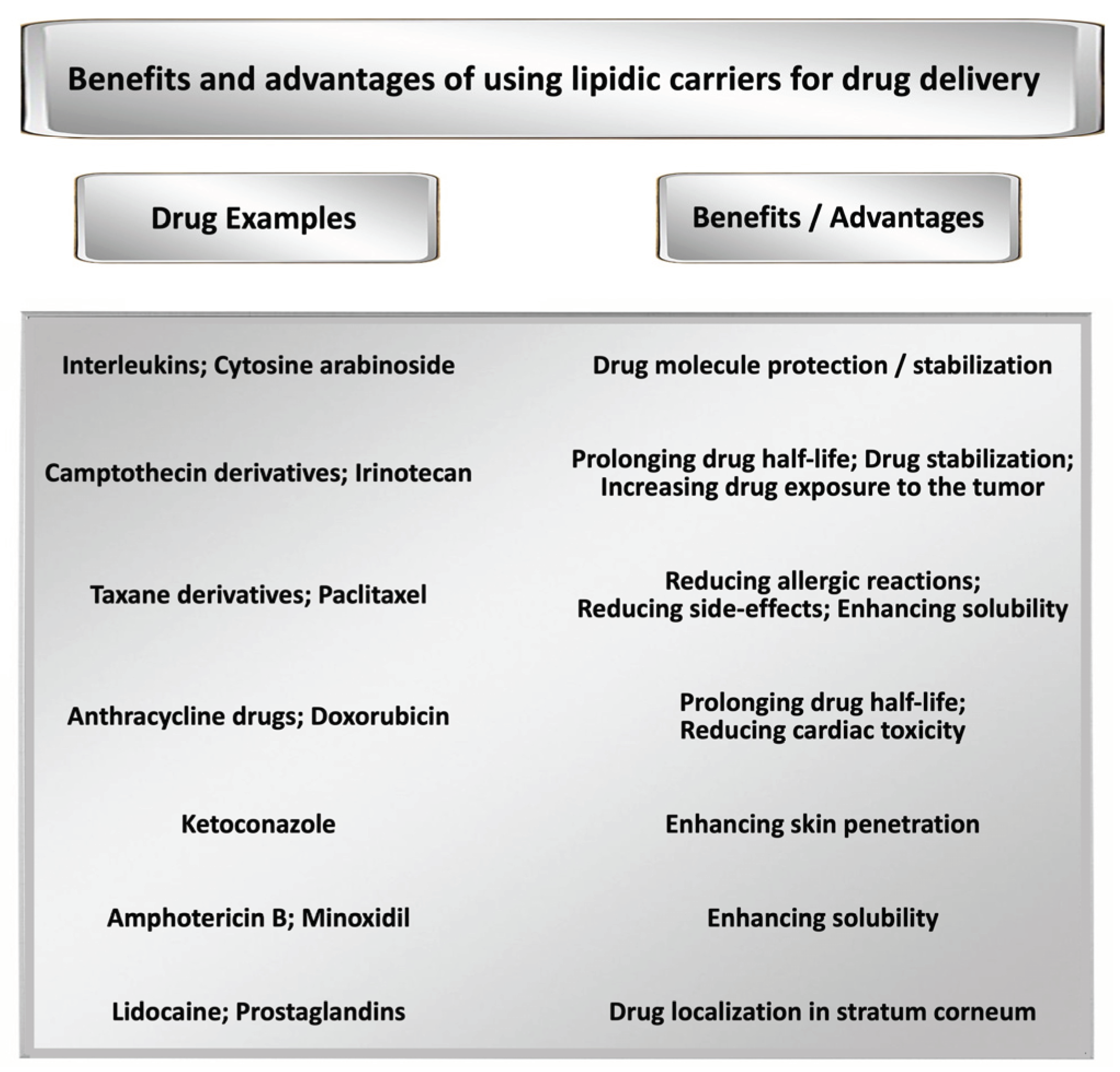

Figure 1 represents some of the proven advantages of using lipidic carriers in the formulation of medicinal products by giving examples of chemotherapeutic and other active compounds. The antineoplastic products primarily include anthracycline drugs, as well as taxane and camptothecin derivatives (see

Figure 1).

Some of the main lipidic carriers include: Vesosome, Phytosome, Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN), Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC), Tocosome and Archaeosome [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These carriers are being used for the entrapment or encapsulation of therapeutic, preventive and diagnostic agents as well as polypeptides and nucleic acid molecules [

8,

9,

10]. Among the lipid-based drug delivery systems archaeolipid vesicles are of particular interest due to their significant thermostability along with long-term stability, resistance to enzymatic degradation, and immunomodulatory characteristics [

11]. This entry provides an overview of carrier systems prepared using natural and synthetic ingredients from archaeal microorganisms, as well as their role in the formulation of nucleic acid therapeutics as well as adjuvants and vaccine candidates.

2. Archaeal Lipid Vesicles

Bilayered vesicles composed of archaeal lipids and phospholipids are generally known as archaeosomes. The term archaeosome is composed of two Greek words: ‘archaea’ (i.e., ancient) and ‘some’ (or soma; i.e., body) and refers to a synthetic drug delivery vesicle containing one or more phospho/lipids extracted from Archaeobacteria (an ancient microorganism from the domain Archaea) [

12,

13].

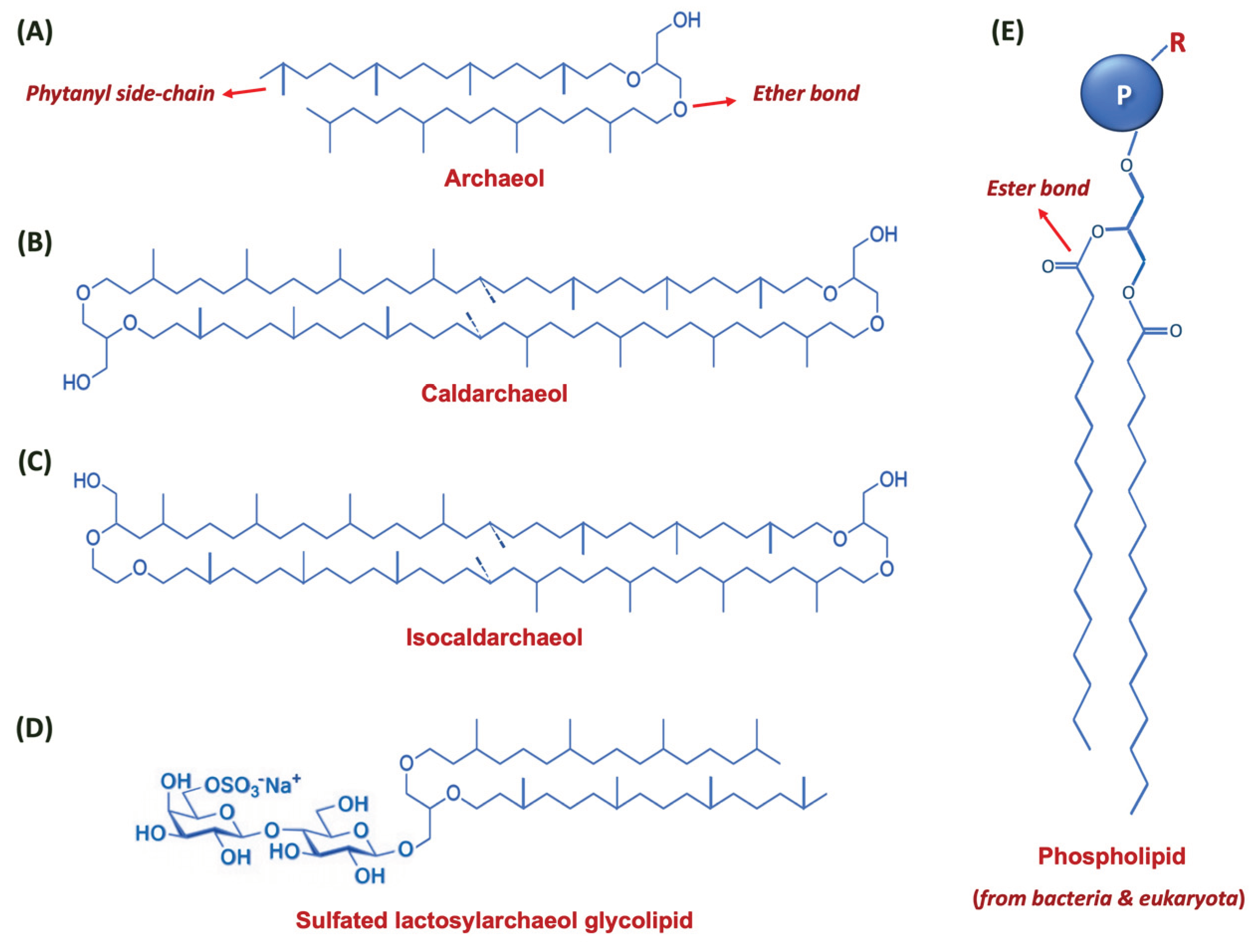

Figure 2 depicts structures of some of the main lipids found in the archaea in comparison with a typical phospholipid found in the eucaryotic and procaryotic organisms. Around 30 years ago, archaea were officially acknowledged as a third domain of life, when a reclassification based on phylogenetic analysis of the rRNA sequences was suggested [

14]. They are a distinctive group of living organisms, which are recognized as “extremophiles” because their species are commonly dispersed in hostile locations.

Many of the archaea species live in harsh environments and inhospitable locations characterised by high salt concentrations, high temperatures or low pH values. Accordingly, the ingredients of their membranes (i.e., ether lipids / phospholipids) are exceptional and enable them to live and thrive in such harsh ecosystems. Compared to liposomes and nanoliposomes (that are made from ester phospholipids -

Figure 2E), archaeal lipid vesicles are more thermostable and more resistant to hydrolysis and oxidation. Furthermore, they are more resilient to bile salts and low pH that would be encountered in the gastrointestinal (GI) milieu [

15]. Archaeal vesicles prepared from the total polar lipid extract or from individually purified polar lipids are very promising as an oral carrier system of drugs and other bioactive agents. As is the case with other drug carriers such as liposomes and nanoliposomes, it is possible to incorporate certain moieties (e.g., polyethylene glycol - PEG or polyhydroxyethyl-L-asparagine - PHEA) on the archaeosome surface to increase their blood circulation time. Some scientists reported that integration of PEG or coenzyme Q10 to the archaeal lipid vesicle formulations can amend their tissue distribution behaviour when administered intravenously [

16].

Omri and colleagues [

17] have shown that oral and intravenous delivery of nanometric-sized archaeal vesicles to an animal model was well tolerated with no detectable toxicity. Li and co-workers [

18] demonstrated that archaeal vesicles possess superior stability in the simulated GI fluids, and enable fluorescently labelled peptides to reside for longer times in the GI tract after oral administration when compared to the unencapsulated peptides. In another study, archaeosomes were prepared using polar lipid fraction E (PLFE) extracted from

Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, and their immunogenic properties as oral vaccine delivery vehicles were evaluated [

19]. Results of the study revealed that the archaeal vesicles had greater stability in the simulated gastro intestinal solutions, and helped antigens to be retained for longer period of time in the GI tract after oral administration [

19]. More recently, archaeal vesicles, prepared using sulfated lactosylarchaeol (SLA) glycolipids (

Figure 2D), proved to be an efficient vaccine adjuvant in multiple preclinical models of cancer or infectious disease [

20].

Results of these studies have revealed the ability of the synthetic and semi-synthetic archaeal lipid vesicles to induce strong cellular and humoral immune responses towards different types of antigens [

20,

21]. Authors concluded that the ability of the archaeal vesicles to induce antigen-specific reactions was superior to many of the adjuvants tested in their studies [

19,

20,

21]. Outcomes of these studies are very encouraging for the potential utilisation of archaeal vesicles in the encapsulation and controlled release of various bioactive agents via different routes of drug administration. In the following sections, the applications of archaeal lipid vesicles as adjuvants as well as for the delivery of genetic material and vaccine candidates will be presented.

3. Gene Delivery Applications

The unique chemical and biological properties of the ingredients of archaeal lipid vesicles, characterized by ether bonds, saturation and cyclopentane rings, provides them with high mechanical strength as well as exceptional enzymatic, chemical and physical stability [

22,

23]. Certain properties of the ether lipids, including stability towards high temperatures and acidic environments, make them extremely useful for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications (

Table 1). Their temperature stability is a significant superiority over conventional liposomes and nanoliposomes made from ester lipids, particularly during processing and storage. In addition, stability towards low pH values makes archaeal lipid vesicles suitable for oral drug administration, since they can protect their load from degradation in the GI tract [

24].

Applications of archaeal lipid vesicles in gene or drug delivery has received increasing attention, particularly due to their outstanding ability to preserve the structure and function of the sensitive therapeutic agents [

25]. Traditionally, cationic liposome-DNA multiplexes have been extensively used for in vitro and in vivo gene transfer investigations. Anionic and zwitterionic vesicles were also utilized for the encapsulation and delivery of polynucleotides, albeit to a less degree. However, recently reported research outcomes have established that archaeal lipid vesicles can also be used as efficient carrier vehicles of RNA, DNA and other nucleic acid molecules [

26].

Table 1.

Main advantages of archaeal lipid vesicles for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications.

Table 1.

Main advantages of archaeal lipid vesicles for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications.

| Item |

Advantages of Archaeal Vesicles |

Ref.’s |

| 1 |

The saturated alkyl chains provide protection against oxidative assault. As a result, archaeal vesicles do not need to be kept under inert atmosphere during storage. |

[12,25] |

| 2 |

In the structure of the vesicles, the bipolar lipid molecules traverse the bilayers and improve their stability. |

[22,27,28] |

| 3 |

The archaeal lipid derivatives provide enhanced stability towards hydrolysis. |

[15,29] |

| |

The ether links are more stable than ester bonds at wide range of pH values. |

[30,31] |

| 5 |

The distinctive stereochemistry of the glycerol backbone ensures resistance towards degradation by the phospholipase enzymes. |

[15,32] |

| 6 |

Presence of cyclic rings in the transmembrane section of the bilayers appear to provide thermo-adaptive response, resulting in the improved bilayer packing and decreased membrane fluidity. |

[11,33] |

| 7 |

The branched methyl groups decrease crystallization and reduce bilayer permeability. |

[12,34,35] |

| 8 |

Archaeal lipids can function as self-adjuvant vaccine candidates. |

[20,21,36] |

| 9 |

Archaeal lipid vesicles have demonstrated acceptable safety profile. |

[37,38,39] |

Zwitterionic and positively-charged archaeal tetraether analogues possessing a central cyclopentane ring along with bilayer-forming synthetic cationic tetraether lipids mixed with DOPE or the cationic aliphatic lipid glycine betaine derivative (MM18), were utilized for in vitro transfection of the cultured A549 cells [

40]. Archaeosomes prepared using MM18 or neutrally charged archaeal tetraether-like lipid (at 95.5 w/w ratio), revealed activities similar to the commercial reagent Lipofectamine (at the charge ratio of +8). In addition, the in vivo transfection efficiency of cationic phospholipids and plasmid DNA (coding for the luciferase enzyme) complexed with a synthetic neutrally-charged tetraether-like lipid, was found to depend on certain factors including the type of cationic phospholipid, the lipid/co-lipid molar ratio and the route of administration (intranasal or intravenous) [

41]. Intravenously injected MM18 / neutral archaeal tetraether-like lipid at the 10:1 Molar ratio revealed high in vivo transfection efficiency, particularly to the lungs, and to the spleen (but to a less extent). The lipidic complexes revealed plasma stability while they were able to disassemble inside the cytoplasmic endosomes with subsequent release of the plasmid DNA. Moreover, following the addition of PE-PEG500 to the lipid-based formulations, they were effective after intranasal administration [

40,

41].

In a study aimed to target tumoral cells overexpressing the folate receptor, Laine and co-workers synthesized diether and tetraether lipids and functionalised them with a short polyethyleneglycol chain (i.e., PEG–570) and a folate moiety [

42]. These phospho/lipids, mixed with the conventional bilayer-forming glycine betaine-based cationic lipid (at 5–10 w/w %) resulted in a significant transfection efficiency when tested on the HeLa cells, which was inhibited in the presence of free folic acid molecules. The diether derivative revealed very high transfection potency at a neutral charge ratio, higher than that of the commercially available transfection agent Lipofectamine [

42].

In a recent study, Attar and colleagues [

43] investigated the potential of anionic archaeal vesicles for the delivery of DNA molecules in some mammalian cell lines. They extracted ether lipid molecules from the

H. hispanica 2TK2 strain, which is an extremely halophilic archaeon microorganism. This was followed by combining the archaeal lipids with plasmid molecules encoding the β-galactosidase enzyme or a green fluorescent polypeptide and incubating them on the cultured embryonic renal cells (HEK293) for twenty-four hours at ambient temperatures. Initially, the archaeal vesicles exhibited low efficacy in complexing with the plasmid molecules as well as low transfection efficiency due to their negative charge repelling the similarly charged DNA molecules. In order to overcome this problem, scientists employed positively-charged ions or cationic molecules, including 1,2-dioleoyl-3-(trimethylammonium) propane, Mg

2+ or Ca

2+ as the bridging moieties in the lipidic carrier formulations [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48].

The idea of using non-toxic and biocompatible divalent cations to link polynucleotides to the negatively charged lipids is based on the studies by Zhdanov and co-workers [

49]. Accordingly, studies on the mammalian cell lines revealed that the application of ions / cationic molecules / divalent cations resulted in a substantial improvement in the level of transfection efficiency. In another in vitro research, Benvegnu and co-workers [

50] reported that novel hybrid and cationic archaeal vesicles, formulated using different combinations of cationic / zwitterionic bilayer-forming phospholipids as well as synthetic tetraether-type bipolar phospholipids, revealed significantly high levels of transfection efficiency. The phospho/lipid-DNA multiplexes were formulated by combining optimised quantity of aqueous suspensions of cationic liposomes or archaeosomes with DNA molecules (9.7kb - pTG11033 - containing luciferase gene) and analysed after 30 minutes of incubation at ambient temperatures. These studies have confirmed the advantages of formulating hybrid vesicles by mixing conventional bilayer-forming phospho/lipids with monolayer-forming ingredients as a new approach to modulate membrane fluidity of the multiplexes formed with the nucleic acid molecules [

50,

51].

In a proprietary research Benvegnu and colleagues [

52] patented a formulation of archaeal lipid vesicles prepared employing positively-charged synthetic archaeobacterial lipid analogues (a positively-charged synthetic diester or a cationic tetraether) by the thin-layer hydration technique. The particle size of the vesicles was then narrowed down by extrusion using polycarbonate membrane filters or by sonication. A plasmid vector expressing the firefly luciferase gene (i.e., plasmid DNA pCMV-Lluc) was encapsulated in the archaeal vesicle formulation, as well as conventional liposomes manufactured using certain proportions of cholesterol and the synthetic phospholipid dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE). The archaeosomal formulations were subsequently tested on the cultured human pulmonary malignant epithelial cells in order to evaluate the transfection efficiency. Study results indicated that the gene transfer efficacies were significantly enhanced by employing vesicles formulated with synthetic tetraether cationic archaeal phospholipids and zwitterionic tetraether co-lipids, compared to the conventional lipid vesicles. Further studies revealed that incorporation of synthetic tetraether archaeal lipid analogues in the lipid-based complexes significantly enhanced the stability of the vesicles, similar to those formulated using the natural phospholipid extracts of the

Thermoplasma acidophilum bacteria [

52]. Thanks to these profound discoveries, new possibilities have been emerged for the employment of synthetic archaeal phospholipid analogues, as safe and stable ingredients, in the construction of gene transfer vectors.

4. Archaeal Lipids as Adjuvants and Vaccine Delivery Systems

Archaea possess a multitude of molecular and cellular features which warrants the stability of their cellular components, particularly polypeptides and bilayer membranes at different biological circumstances. These adjustments to harsh settings resulted in a significant interest among scientists to formulate and develop archaeal delivery systems for different pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals including medicaments, genes, vaccines, proteins, peptides, vitamins, minerals and natural antioxidants. Different formulations of archaeosomes are being developed and tested in vitro as well as in vivo, inside the biological systems [

53,

54]. Some examples of the biomedical applications of archaeal lipids are summarized in

Table 2.

Since liposomes, nanoliposomes and archaeosomes are naturally targeted by the cells of the reticuloendothelial system (RES - in particular mononuclear phagocytic cells) [

55,

56,

57], they are ideal candidates for the incorporation and delivery of antigens. Furthermore, they can be employed directly as adjuvants − or indirectly as carrier systems for adjuvants − with the ability of immune system stimulation. Adjuvants are defined as substances that augment the immune reaction of the body to an exogenous antigen. They are usually incorporated to vaccine candidates in order to provoke more intense in vivo immunogenicity. Tolson and colleagues [

37] have investigated the uptake efficiency of vesicles made using the polar lipid molecules obtained from different methanogenic archaeobacteria (e.g.,

M. mazei,

M. smithii, and

M. voltae), and combined them with the conventional phospholipids comprised of a combination of ester lipids dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine, or dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine: dimyristoyl phosphatidyl glycerol: and cholesterol (in the molar ratio of 1.8:0.2:1.5, respectively). Their study revealed that the vesicles made employing the polar phospholipids of various archaeal species were endocytosed significantly more by the RES cells when compared with the liposomal vesicles. Significant endocytosis of the archaeal vesicles by the RES cells indicates their usefulness for drug targeting to the cells of the immune system and for the transport of antigens to the antigen-presenting cells. These findings reveal that the archaeal vesicles have the potential to be employed as efficient systems for targeting the phagocytic cells of the RES [

37,

58].

Archaeal lipid vesicles formulated using different compositions of total polar lipids (TPL) have the capacity to deliver the incorporated antigen to antigen-processing cells (APCs) for presentation by major histocompatibility complex (MHC class I and II proteins) [

59,

60]. However, studies showed that conventional liposomes were not able to present ovalbumin (OVA) to the MHC class I pathway [

61] and only caused an antibody response that was generally lower than that generated by the archaeal vesicles [

62]. Krishnan and co-workers [

63] assessed the ability of archaeal vesicles to stimulate different aspects of immune responses against the incorporated antigens. They also investigated the mechanisms of adjuvanticity of archaeal vesicles, and evaluated their efficacy in comparison with conventional lipidic vesicles composed of phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylcholine, and cholesterol. Towards this end, conventional lipid vesicles as well as archaeal carriers of the same particle size (∼200nm) were manufactured using the ether glycerolipids of different archaeal species and were loaded with bovine serum albumin (BSA). The vesicles were then injected to mice, that possessed diverse hereditary traits, via subcutaneous, intramuscular and intraperitoneal routes. Findings of the study showed that the archaeal vesicles loaded with BSA increased the serum anti-BSA antibody titers significantly more compared to the alum and conventional lipid vesicles. In addition, production of antigen-specific immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), IgG2a, and IgG2b isotype antibodies by the animals were stimulated. Furthermore, immunizations employing archaeosomal-antigen formulations induced a potent cell-mediated immune reaction, as well as antigen-dependent proliferation and also increased synthesis of cytokines (e.g., interleukin-4 and gamma interferon) by the cultured lymphatic cells. Contrary to the Freund’s adjuvant and alum, archaeal vesicles manufactured using lipids extracted from Thermoplasma acidophilum exhibited a sustained antibody memory reaction to the same antigen (∼300 days) only after two sets of immunizations (at days zero and fourteen). Studies indicated that the archaeal vesicles are potent adjuvants as well as efficient antigen delivery vehicles and are able to improve humoral and cell-mediated immune reactions to various encapsulated antigens [

60,

61,

62,

63].

It has been proposed that the archaeal core lipid structures (branched and saturated isopranoid chains joined by ether bonds to the glycerol backbone) as well as the interaction of archaeal lipid head groups with APC receptors, contribute to the adjuvanticity of archaeal vesicles [

60,

64]. The enhanced adjuvanticity of archaeal vesicles compared to the conventional liposomes is largely based on their unique ability to function as immunomodulators, stimulating the innate immunity, and enhancing the recruitment and activation of specialised APCs, rather than being merely due to the efficient delivery of the antigens to these cells [

65,

66]. Nevertheless, the strong memory responses could be considered to be partially due to the longer antigen persistence that would be expected to be afforded by the depot effect of the robust archaeal vesicles [

67,

68].

Table 2.

Some examples of pharmaceutical applications of archaeal lipid formulations.

Table 2.

Some examples of pharmaceutical applications of archaeal lipid formulations.

| Active Agent |

Function |

Mechanism of Action |

Implications |

Ref. |

| A1 protein |

Anticancer agent |

Causing fast leakage of the cellular contents. |

Cytotoxic to cancer cells. |

[69] |

| Betamethasone dipropionate |

Anti- inflammatory |

Adsorption to the deeper skin layers. |

Efficient infiltration and epidermis drug delivery. |

[70] |

| Bovine serum albumin |

Vaccine |

Enhanced production

of the CD8+ T cells. |

Modulate primary, sustained, and/or innate immunity, archaeal lipid vesicles function as ideal adjuvants. |

[63] |

| Cholera / toxin B subunits |

Vaccine |

Enhanced antibody manufacture. |

Improved humoral immune response. |

[65] |

| Doxorubicin |

Cancer therapy |

Hyperthermia-induced cell death. |

Long-term release with diminished adverse-effects. |

[71] |

| Insulin |

Diabetes treatment |

Reducing blood glucose levels. |

Stable in the digestive system. |

[72] |

| Paclitaxel |

Cancer therapy |

Enhanced polymerization of tubulin. |

Decreased adverse effects and improved therapeutic efficacy. |

[53] |

| Phenols (obtained from olive) |

Antioxidant |

Inhibiting cell damage. |

Enhanced stability,

sustained drug release. |

[73] |

| Plasmid DNA |

Gene delivery / Gene therapy |

Transfection |

Enhanced stability and transfection efficiency. |

[43] |

In an in vivo study, Sprott and co-workers [

65] assessed the capability of archaeal vesicles, as promising antigen carrier vehicles, by comparing the humoral immune reaction in BALB/c mice, induced by different antigens including cholera toxin B subunits and bovine serum albumin. The vesicles were manufactured using the polar phospholipids of different archaeal species including

Methanosaeta concilii GP6 (DSM 3671),

Methanobacterium espanolae GP9 (DSM 5982),

Thermoplasma acidophilum 122-1B3 (ATCC 27658),

Methanobrevibacter smithii ALI (DSM 2375), and

Methanococcus voltae PS (DSM 1537). They observed that after just two vaccinations, maximum IgG + IgM antibody titers in the sera were induced in the mice employing archaeal vesicles formulated using the phospholipids of

Methanobrevibacter smithii that is an inhabitant of the human colon. In a similar manner, a positive reaction to the cholera B subunit peptide was attained using

M. smithii vesicles to activate antibody manufacture in the rodents. Researchers concluded that in addition to the in vivo stability of the archaeal vesicles at the injection site, their enhanced incorporation by the antigen presenting cells, as well as steady and long-term release of their load, could be some of the main reasons for a significant increase in the antibody manufacture. The study has also revealed that entrapment or encapsulation of protein antigens by the archaeal vesicles is a crucial step for achieving an enhanced humoral immune response compared to the free (unencapsulated) antigens [

65,

74].

In more recent studies, researchers employed a semi-synthetic archaeal phospholipid (i.e., sulfated lactosyl archaeol) to encapsulate different antigens and to assess the potential of SLA glycolipid as an adjuvant system [

75,

76]. Their studies revealed that immunizing mice with variants of concern (VOC)-based vaccines, specifically Beta and Delta-based spike trimer antigens, resulted in improved neutralizing responses to spike proteins from the corresponding variant. They also found out that SmT1-O antigen, stimulated stronger neutralizing responses to Omicron-based spike compared to a reference strain-based vaccine candidate, as revealed by two independent neutralization assays. These researchers concluded that cell-mediated responses, which play important roles in the neutralization of intracellular infections, were stimulated to a significantly higher level with the SLA adjuvant when compared with the Adda S03-adjuvanted preparations. Consequently, further developed vaccines, which are better capable of targeting the SARS-CoV-2 variants, could be formulated via an optimized combination of adjuvant and antigen components [

75,

76].

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Drug delivery techniques encompass a wide range of formulations designed to optimize drug efficacy, safety, and patient adherence across various routes of administration and therapeutic indications. Different ingredients, including polymers, surfactants and a variety of lipid molecules, can be used for the construction of drug carriers. The distinctive attributes of the archaeal phospholipids were discussed in this review along with the potential of the archaeolipid vesicles as novel drug carriers, which possess the ability of carrying hydrophilic, hydrophobic and amphiphilic compounds. Their potential as a carrier system for genetic material and vaccine candidates were discussed. The exceptional stability of archaeal lipid vesicles under harsh and extreme conditions allows them to overcome challenges encountered by conventional liposomes and nanoliposomes in the delivery of vaccines and bioactive compounds. The profound potential of archaeal vesicles to safely deliver various adjuvants and antigens offers new prospects in vaccine therapy for different infections and cancers. Archaeal lipid-based carriers are self-adjuvanting and non-replicating antigen delivery systems that can promote efficient and long-lasting antigen-specific humoral and cell-mediated immunities, and induce strong memory responses. The potential of archaeal lipid adjuvants has been confirmed in vivo, in different animal models. Research thus far revealed that the immune profiles promoted by the archaeal adjuvanted protein and peptide vaccines nearly matches those currently achieved only with live, replicating vaccines. Archaeal lipid vesicles have progressed to the phase where they are now suitable for commercial utilisations. Studies in the future should focus on formulating cost-effective and robust carriers with optimised properties to achieve timely and precise diagnosis as well as site-specific, targeted drug delivery. Significant research prospects remain to be unveiled in order to enhance the efficacy of these carriers with respect to their preventive, therapeutic and theragnostic applications. Chemical alterations of the available natural archaeal lipid and phospholipid molecules, as well as design and synthesis of the phospholipid analogues, are among the best approaches to attain optimum clinical outcomes in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.M. and E.T.; validation, M.A., S.M.N. and O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.N.E., S.A. and G.A.; writing—review and editing, E.T. and O.A.; supervision, G.Z., E.T. and M.R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank, acknowledge and remember Professor Dr. Renad Ibrahimovich Zhdanov (Renat Ibrahimovic Zhdanov - BSc, MSc, PhD, DSc) who was the first from whom we learned the concept of liposomes and related technologies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Namiot ED, Sokolov AV, Chubarev VN, Tarasov VV, Schiöth HB. Nanoparticles in Clinical Trials: Analysis of Clinical Trials, FDA Approvals and Use for COVID-19 Vaccines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023 Jan; 24 (1): 787. [CrossRef]

- Peng T, Xu W, Li Q, Ding Y, Huang Y. Pharmaceutical liposomal delivery-specific considerations of innovation and challenges. Biomaterials Science. 2023; 11 (1): 62-75. [CrossRef]

- Maherani B, Arab-Tehrany E, Mozafari MR, Gaiani C, Linder M. Liposomes: a review of manufacturing techniques and targeting strategies. Current Nanoscience. 2011 Jun 1; 7 (3): 436-452. [CrossRef]

- Naseri N, Valizadeh H, Zakeri-Milani P. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers: structure, preparation and application. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2015 Sep; 5 (3): 305. [CrossRef]

- Katopodi A, Detsi A. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers of natural products as promising systems for their bioactivity enhancement: The case of essential oils and flavonoids. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2021 Dec 5; 630: 127529. [CrossRef]

- Mozafari MR, Javanmard R, Raji M. Tocosome: novel drug delivery system containing phospholipids and tocopheryl phosphates. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2017 Aug 7; 528 (1-2): 381-382. [CrossRef]

- Asadujjaman MD, Mishuk AU. Novel approaches in lipid based drug delivery systems. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics. 2013 Jul 13; 3 (4): 124-130. [CrossRef]

- Al Badri YN, Chaw CS, Elkordy AA. Insights into Asymmetric Liposomes as a Potential Intervention for Drug Delivery Including Pulmonary Nanotherapeutics. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Jan 15; 15 (1): 294. [CrossRef]

- Jamalifard R, Jamali SN, Khorasani S, Katouzian I, Wintrasiri M, Mozafari MR. Liposomal saffron: A promising natural therapeutic and immune-boosting agent. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2022; 13. https://www.ijpvmjournal.net/text.asp?2022/13/1/105/353567.

- Pourmadadi M, Eshaghi MM, Ostovar S, Mohammadi Z, Sharma RK, Paiva-Santos AC, Rahmani E, Rahdar A, Pandey S. Innovative nanomaterials for cancer diagnosis, imaging, and therapy: Drug deliveryapplications. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2023 Mar 12:104357. [CrossRef]

- Kejzar J, Osojnik Črnivec IG, Poklar Ulrih N. Advances in Physicochemical and Biochemical Characterization of Archaeosomes from Polar Lipids of Aeropyrum pernix K1 and Stability in Biological Systems. ACS Omega. 2023 Jan 13; 8 (3): 2861-2870. [CrossRef]

- Kaur G, Garg T, Rath G, Goyal AK. Archaeosomes: an excellent carrier for drug and cell delivery. Drug Delivery. 2016 Sep 1; 23 (7): 2497-2512. [CrossRef]

- Patel GB, Sprott GD. Archaeobacterial ether lipid liposomes (archaeosomes) as novel vaccine and drug delivery systems. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 1999 Jan 1; 19 (4): 317-357. [CrossRef]

- Winker S, Woese CR. A Definition of the Domains Archaea, Bacteria and Eucarya in Terms of Small Subunit Ribosomal RNA Characteristics. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 1991, 14 (4), 305-310. [CrossRef]

- Patel GB, Agnew BJ, Deschatelets L, Fleming LP, Sprott GD. In vitro assessment of archaeosome stability for developing oral delivery systems. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2000 Jan 20; 194 (1): 39-49. [CrossRef]

- Omri A, Makabi-Panzu B, Agnew BJ, Sprott GD, Patel GB. Influence of coenzyme Q10 on tissue distribution of archaeosomes, and pegylated archaeosomes, administered to mice by oral and intravenous routes. Journal of Drug Targeting. 1999 Jan 1; 7 (5): 383-392. [CrossRef]

- Omri A, Agnew BJ, Patel GB. Short-term repeated-dose toxicity profile of archaeosomes administered to mice via intravenous and oral routes. International Journal of Toxicology. 2003 Jan; 22 (1): 9-23. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Chen J, Sun W, Xu Y. Investigation of archaeosomes as carriers for oral delivery of peptides. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010 Apr 2; 394 (2): 412-417. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Zhang L, Sun W, Ding Q, Hou Y, Xu Y. Archaeosomes with encapsulated antigens for oral vaccine delivery. Vaccine. 2011 Jul 18; 29 (32): 5260-5266. [CrossRef]

- Akache B, Stark FC, Jia Y, Deschatelets L, Dudani R, Harrison BA, Agbayani G, Williams D, Jamshidi MP, Krishnan L, McCluskie MJ. Sulfated archaeol glycolipids: Comparison with other immunological adjuvants in mice. PLoS One. 2018 Dec 4; 13 (12): e0208067. [CrossRef]

- Jia Y, Agbayani G, Chandan V, Iqbal U, Dudani R, Qian H, Jakubek Z, Chan K, Harrison B, Deschatelets L, Akache B, McCluskie MJ. Evaluation of Adjuvant Activity and Bio-Distribution of Archaeosomes Prepared Using Microfluidic Technology. Pharmaceutics. 2022; 14 (11): 2291. [CrossRef]

- Gambacorta A, Gliozzi A, De Rosa M. Archaeal lipids and their biotechnological applications. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1995 Jan; 11: 115-131. [CrossRef]

- Brown DA, Venegas B, Cooke PH, English V, Chong PL. Bipolar tetraether archaeosomes exhibit unusual stability against autoclaving as studied by dynamic light scattering and electron microscopy. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 2009 Jun 1; 159 (2): 95-103. [CrossRef]

- Rastädter K, Wurm DJ, Spadiut O, Quehenberger J. The cell membrane of Sulfolobus spp. –homeoviscous adaption and biotechnological applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020 May 30; 21 (11): 3935. [CrossRef]

- Benvegnu T, Lemiègre L, Cammas-Marion S. Archaeal lipids: innovative materials for biotechnological applications. European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2008 Oct; 2008 (28): 4725-4744. [CrossRef]

- Rethore G, Montier T, Le Gall T, Delepine P, Cammas-Marion S, Lemiegre L, Lehn P, Benvegnu T. Archaeosomes based on synthetic tetraether-like lipids as novel versatile gene delivery systems. Chemical Communications. 2007 (20): 2054-2056. [CrossRef]

- Shinoda W, Shinoda K, Baba T, Mikami M. Molecular dynamics study of bipolar tetraether lipid membranes. Biophysical Journal. 2005 Nov 1; 89 (5): 3195-3202. [CrossRef]

- Benvegnu T, Brard M, Plusquellec D. Archaeabacteria bipolar lipid analogues: structure, synthesis and lyotropic properties. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 2004 Apr 1; 8 (6): 469-479. [CrossRef]

- Benvegnu T, Lemiègre L, Cammas-Marion S. New generation of liposomes called archaeosomes based on natural or synthetic archaeal lipids as innovative formulations for drug delivery. Recent Patents on Drug Delivery & Formulation. 2009 Nov 1; 3 (3): 206-220. [CrossRef]

- Patel GB, Chen W. Archaeosomes as drug and vaccine nanodelivery systems. Nanocarrier Technologies: Frontiers of Nanotherapy. 2006: 17-40.

- Santhosh PB, Genova J. Archaeosomes: new generation of liposomes based on archaeal lipids for drug delivery and biomedical applications. ACS Omega, 2023; 8, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Vazzana M, Fangueiro JF, Faggio C, Santini A, Souto EB. Archaeosomes for skin injuries. In Carrier-Mediated Dermal Delivery. 2017; (pp. 323-355). Jenny Stanford Publishing, Singapore.

- Jain S, Caforio A, Driessen AJ. Biosynthesis of archaeal membrane ether lipids. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2014 Nov 26; 5: 641. [CrossRef]

- Jacquemet A, Barbeau J, Lemiègre L, Benvegnu T. Archaeal tetraether bipolar lipids: Structures, functions and applications. Biochimie. 2009; 91, 711–717. [CrossRef]

- Haq K, Jia Y, Krishnan L. Archaeal lipid vaccine adjuvants for induction of cell-mediated immunity. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2016 Dec 1; 15 (12): 1557-1566. [CrossRef]

- Shinoda W, Shinoda K, Baba T, Mikami M. Molecular dynamics study of bipolar tetraether lipid membranes. Biophysical Journal. 2005 Nov 1; 89 (5): 3195-3202. [CrossRef]

- Tolson DL, Latta RK, Patel GB, Sprott GD. Uptake of archaeobacterial liposomes and conventional liposomes by phagocytic cells. Journal of Liposome Research. 1996; 6: 755-776. [CrossRef]

- Patel GB, Omri A, Deschatelets L, Dennis Sprott G. Safety of archaeosome adjuvants evaluated in a mouse model. Journal of Liposome Research. 2002 Jan 1; 12 (4): 353–372. [CrossRef]

- Patel GB, Ponce A, Zhou H, Chen W. Safety of intranasally administered archaeal lipid mucosal vaccine adjuvant and delivery (AMVAD) vaccine in mice. International Journal of Toxicology. 2008 Jul; 27 (4): 329–339. [CrossRef]

- Ponti F, Campolungo M, Melchiori C, Bono N, Candiani G. Cationic lipids for gene delivery: Many players, one goal. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 2021 Mar 1; 235: 105032. [CrossRef]

- Le Gall T, Barbeau J, Barrier S, Berchel M, Lemiegre L, Jeftic J, Meriadec C, Artzner F, Gill DR, Hyde SC, Férec C. Effects of a novel archaeal tetraether-based colipid on the in vivo gene transfer activity of two cationic amphiphiles. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2014 Sep 2; 11 (9): 2973-2988. [CrossRef]

- Laine C, Mornet E, Lemiegre L, Montier T, Cammas-Marion S, Neveu C, Carmoy N, Lehn P, Benvegnu T. Folate-equipped pegylated archaeal lipid derivatives: synthesis and transfection properties. Chemistry – A European Journal. 2008 Sep 19; 14 (27): 8330-8340. [CrossRef]

- Attar A, Ogan A, Yucel S, Turan K. The potential of archaeosomes as carriers of pDNA into mammalian cells. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology. 2016 Feb 17; 44 (2): 710−716. [CrossRef]

- Zareie MH, Mozafari MR, Hasirci V, Piskin E. Scanning tunnelling microscopy investigation of liposome-DNA-Ca2+ complexes. Journal of Liposome Research. 1997; 7 (4), pp. 491-502. [CrossRef]

- Mozafari MR, Zareie MH, Piskin E, Hasirci V. Formation of supramolecular structures by negatively charged liposomes in the presence of nucleic acids and divalent cations. Drug Delivery, 1998; 5 (2), pp. 135-141. [CrossRef]

- Mozafari MR, Hasirci V. Mechanism of calcium ion induced multilamellar vesicle-DNA interaction. Journal of Microencapsulation. 1998; 15 (1), pp. 55-65. [CrossRef]

- Mozafari MR, Omri A. Importance of divalent cations in nanolipoplex gene delivery. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007 Aug 1; 96 (8): 1955-1966. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadabadi MR, El-Tamimy M, Gianello R, Mozafari MR. Supramolecular assemblies of zwitterionic nanoliposome-polynucleotide complexes as gene transfer vectors: Nanolipoplex formulation and in vitro characterisation. Journal of Liposome Research. 2009; 19 (2), pp.105-115. [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov RI, Volkova LA, Rodin VV. Lipid spin labeling and NMR study of interaction between polyadenylic acid: polyuridilic acid duplex and egg phosphatidylcholine liposomes. Evidence for involvement of surface groups of bilayer, phosphoryl groups and metal cations. Applied Magnetic Resonance. 1994 Aug;7(1): 131-146. [CrossRef]

- Benvegnu T, Rethore G, Brard M, Richter W, Plusquellec D. Archaeosomes based on novel synthetic tetraether-type lipids for the development of oral delivery systems. Chemical Communications. 2005 (44): 5536-5538. [CrossRef]

- Brard M, Richter W, Benvegnu T, Plusquellec D. Synthesis and supramolecular assemblies of bipolar archaeal glycolipid analogues containing a cis-1, 3-disubstituted cyclopentane ring. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004 Aug 18; 126 (32): 10003-10012. [CrossRef]

- Benvegnu T, Plusquellec D, Rethore G, Sachet M, Ferec C, Montier T, Delepine P, Lehn P. Compounds analogous to lipid membranes in archaebacteria and liposomal compositions including said compounds. PCT Patent WO2006061396 (2006).

- Kashyap, K. Archaeosomes: revolutionary technique for both cell-based and drug-based delivery applications. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Medicine. 2021; 6 (7), 102−127. [CrossRef]

- Alavi SE, Mansouri H, Esfahani MK, Movahedi F, Akbarzadeh A, Chiani M. Archaeosome: as new drug carrier for delivery of paclitaxel to breast cancer. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 2014 Apr; 29: 150−153. [CrossRef]

- Wassef NM, Alving CR, Green R, Kenneth JW, Eds. Complement- dependent phagocytosis of liposomes by macrophages. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press: Orlando, FL 1987; 124-134.

- Moghimi SM, Patel HM. Opsonophagocytosis of liposomes by peritoneal macrophages and bone marrow reticuloendothelial cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1992 Jun 29;1135(3): 269-274. [CrossRef]

- Taher M, Susanti D, Haris MS, Rushdan AA, Widodo RT, Syukri Y, Khotib J. PEGylated liposomes enhance the effect of cytotoxic drug: A review. Heliyon. 2023 Mar 1, 9 (3), e13823. [CrossRef]

- Freisleben HJ, Neisser C, Hartmann M, Rudolph P, Geek P, Ring K, Müller WE. Influence of the main phospholipid (MPL) from Thermoplasma acidophilum and of liposomes from MPL on living cells: cytotoxicity and mutagenicity. Journal of Liposome Research. 1993 Jan 1; 3 (3): 817-833. [CrossRef]

- Sprott GD, Sad S, Fleming LP, DiCaire CJ, Patel GB, Krishnan L. Archaeosomes varying in lipid composition differ in receptor-mediated endocytosis and differentially adjuvant immune responses to entrapped antigen. Archaea. 2003 Oct 1; 1 (3): 151-164. [CrossRef]

- Gurnani K, Kennedy J, Sad S, Sprott GD, Krishnan L. Phosphatidylserine receptor-mediated recognition of archaeosome adjuvant promotes endocytosis and MHC class I cross-presentation of the entrapped antigen by phagosome-to-cytosol transport and classical processing. The Journal of Immunology. 2004 Jul 1; 173 (1): 566-578. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan L, Sad S, Patel GB, Sprott GD. Archaeosomes induce long-term CD8+ cytotoxic T cell response to entrapped soluble protein by the exogenous cytosolic pathway, in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. The Journal of Immunology. 2000 Nov 1;165(9): 5177-5185. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan L, Sad S, Patel GB, Sprott GD. The potent adjuvant activity of archaeosomes correlates to the recruitment and activation of macrophages and dendritic cells in vivo. The Journal of Immunology. 2001 Feb 1; 166 (3): 1885-1893. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan L, Dicaire CJ, Patel GB, Sprott GD. Archaeosome vaccine adjuvants induce strong humoral, cell-mediated, and memory responses: comparison to conventional liposomes and alum. Infection and Immunity. 2000 Jan 1; 68 (1): 54-63. [CrossRef]

- Sprott GD, Dicaire CJ, Gurnani K, Deschatelets LA, Krishnan L. Liposome adjuvants prepared from the total polar lipids of Haloferax volcanii, Planococcus spp. and Bacillus firmus differ in ability to elicit and sustain immune responses. Vaccine. 2004 Jun 2; 22 (17-18): 2154-2162.

- Sprott GD, Tolson DL, Patel GB. Archaeosomes as novel antigen delivery systems. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1997 Sep 1; 154 (1): 17-22. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan L, Sad S, Patel GB, Sprott GD. Archaeosomes induce enhanced cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to entrapped soluble protein in the absence of interleukin 12 and protect against tumor challenge. Cancer Research. 2003 May 15; 63 (10): 2526-2534.

- Krishnan L, Sprott GD. Archaeosomes as self-adjuvanting delivery systems for cancer vaccines. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2003 Jan 1; 11 (8-10): 515-524. [CrossRef]

- Choquet CG, Patel GB, Sprott GD, Beveridge TJ. Stability of pressure-extruded liposomes made from archaeobacterial ether lipids. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1994 Nov; 42: 375-384. [CrossRef]

- Jiblaoui A, Barbeau J, Vivès T, Cormier P, Glippa V, Cosson B, Benvegnu T. Folate-conjugated stealth archaeosomes for the targeted delivery of novel antitumoral peptides. RSC Advances. 2016; 6 (79): 75234−75241. [CrossRef]

- González-Paredes A, Manconi M, Caddeo C, Ramos-Cormenzana A, Monteoliva-Sánchez M, Fadda AM. Archaeosomes as carriers for topical delivery of betamethasone dipropionate: in vitro skin permeation study. Journal of Liposome Research. 2010 Dec 1; 20 (4): 269−276.

- Ayesa U, Chong PL. Polar lipid fraction E from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine can form stable yet thermo-sensitive tetraether/diester hybrid archaeosomes with controlled release capability. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020 Nov 9; 21 (21): 8388. [CrossRef]

- Shah, P. Strategies for Formulation and Systemic Delivery of Therapeutic Proteins. In Protein-Based Therapeutics. 2023 (pp. 163-198). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- González-Paredes A, Clarés-Naveros B, Ruiz-Martínez MA, Durbán-Fornieles JJ, Ramos-Cormenzana A, Monteoliva-Sánchez M. Delivery systems for natural antioxidant compounds: Archaeosomes and archaeosomal hydrogels characterization and release study. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2011 Dec 15; 421 (2): 321−331. [CrossRef]

- Sprott GD, Ferrante G, Ekiel I. Tetraether lipids of Methanospirillum hungatei with head groups consisting of phospho-N, N-dimethylaminopentanetetrol, phospho-N, N, N-trimethylaminopentanetetrol, and carbohydrates. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 1994 Oct 6; 1214 (3): 234-242. [CrossRef]

- Akache B, Renner TM, Stuible M, Rohani N, Cepero-Donates Y, Deschatelets L, Dudani R, Harrison BA, Gervais C, Hill JJ, Hemraz UD. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens derived from beta & delta variants of concern. NPJ Vaccines. 2022; 7 (1): 118. [CrossRef]

- Renner TM, Akache B, Stuible M, Rohani N, Cepero-Donates Y, Deschatelets L, Dudani R, Harrison BA, Baardsnes J, Koyuturk I, Hill JJ, Hemraz UD, Regnier S, Lenferink AEG, Durocher Y, McCluskie MJ. Tuning the immune response: sulfated archaeal glycolipid archaeosomes as an effective vaccine adjuvant for induction of humoral and cell- mediated immunity towards the SARS- CoV-2 Omicron variant of concern. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023; 14: 1182556. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).