1.1. The Context of Displacement and Access to Energy

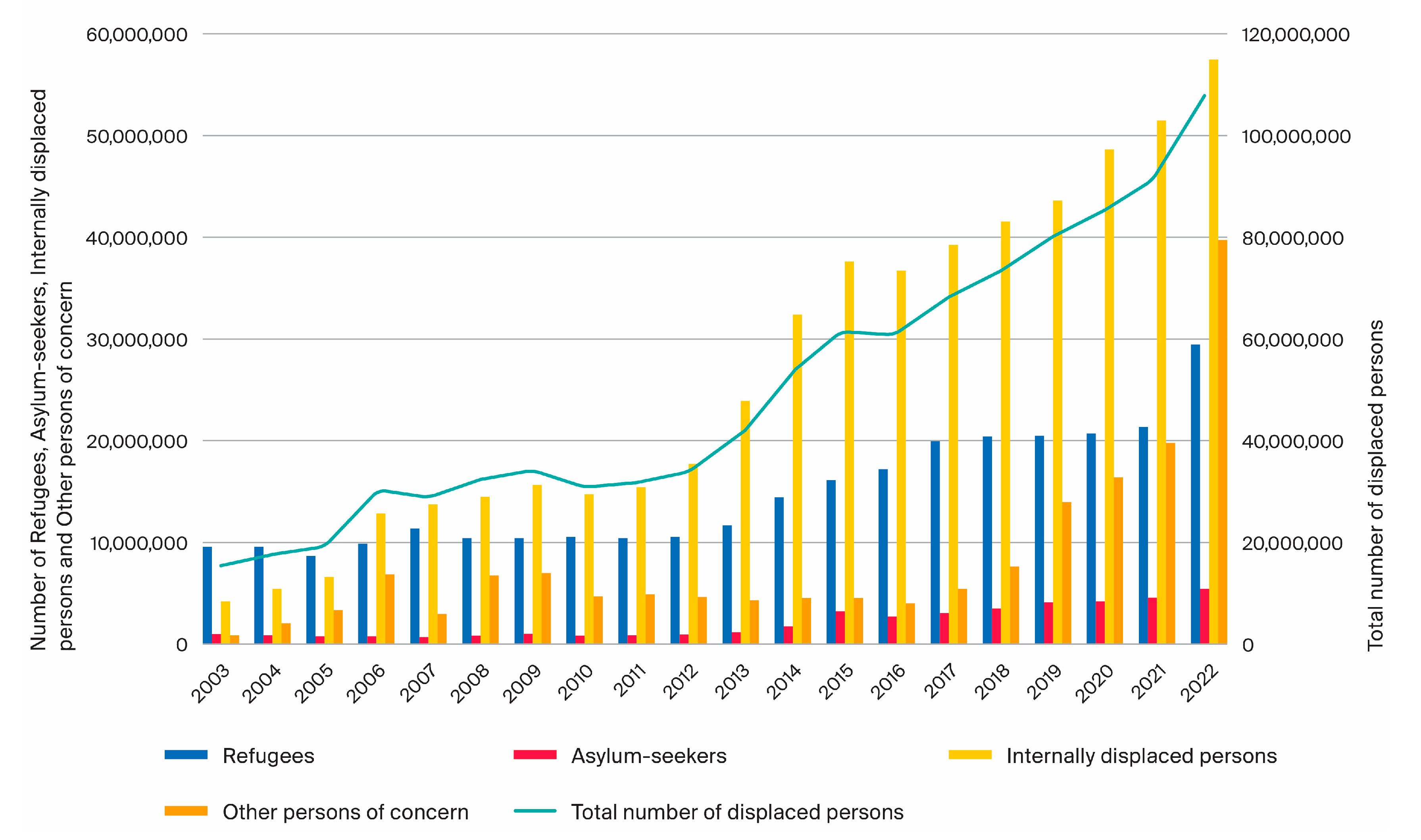

Global crises such as climate change, conflict and natural disasters have resulted in a growing number of persons who were forced to leave their home. UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, estimated that in 2024 there will be 130.8 million displaced persons in the word [

1]. Displaced persons are “persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, either across an international border or within a State […]” [

2]. The term displaced persons includes but is not limited to refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced persons (IDPs), for which relevant definitions can be found elsewhere [

2,

3,

4]. Displacement has implications not only for displaced persons themselves, but also for those hosting them, which are often referred to as the host country and host community. With 134 countries currently accommodating displaced persons [

5], active engagement with the displacement context is a global matter and it is a matter that is growing in scale. As is shown in

Figure 1, in the last decade the number of displaced persons has continuously increased.

While cumulative global statistics are relevant to highlight the increasing relevance of the subject matter, it is essential to acknowledge that the lived experiences of displaced persons vary greatly between different host countries and contexts. A multitude of contextual factors, such as the location and the characteristics of housing (settlement, camp-like, urban, rural, etc.) [

6], the legal status of displaced persons [

7], the socio-cultural background and the availability of humanitarian and public services have a major impact on the conditions of living. In our study we focus on displaced persons residing in settlements and camps. While in the humanitarian space there is no universally agreed upon definition for the term

settlement, we recognize that the terms

settlement and

camp are in many cases used to describe settings with different attributes (e.g., [

4,

6,

8,

9,

10,

11]) and we agree that the differentiation adds a valuable dimension to the discourse.

One key factor determining the conditions of living is access to energy [

12]. In humanitarian settings different energy needs coexist. First, energy is needed to enable the operation of humanitarian actors, such as electricity in the offices of humanitarian organization and fuel for transportation [

6,

12]. Second, displaced persons have a wide range of energy needs that are embedded in basic areas of life [

13], characterized by energy needs on a household level, such as for electricity and cooking, energy needs for income generating activities or businesses and energy needs on the community level, such as streetlights and the operation of public facilities such as schools and hospitals [

13]. In this article, we focus on energy needs of displaced persons on an individual, household and community level as opposed to generalized energy needs that are associated with humanitarian operations.

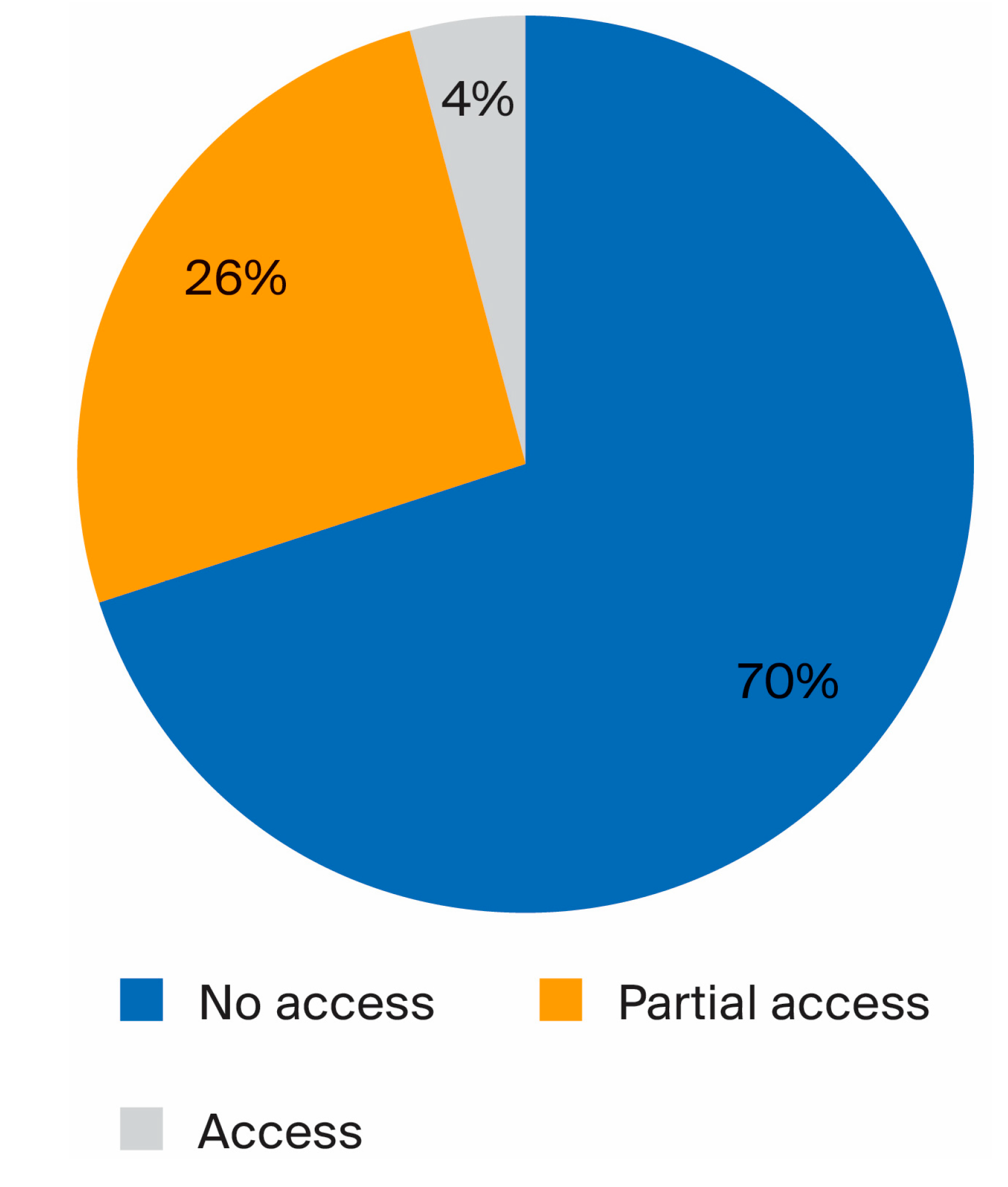

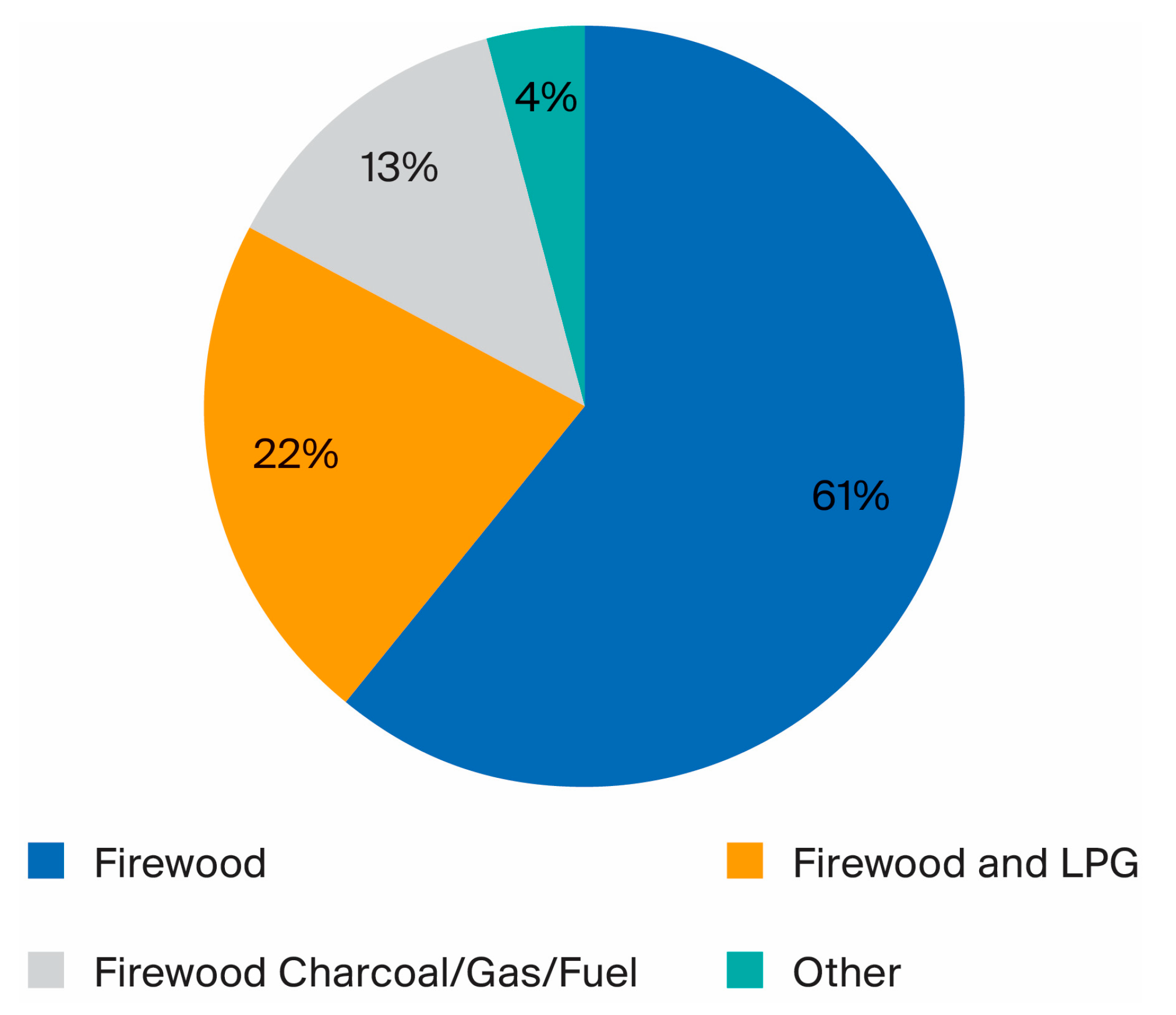

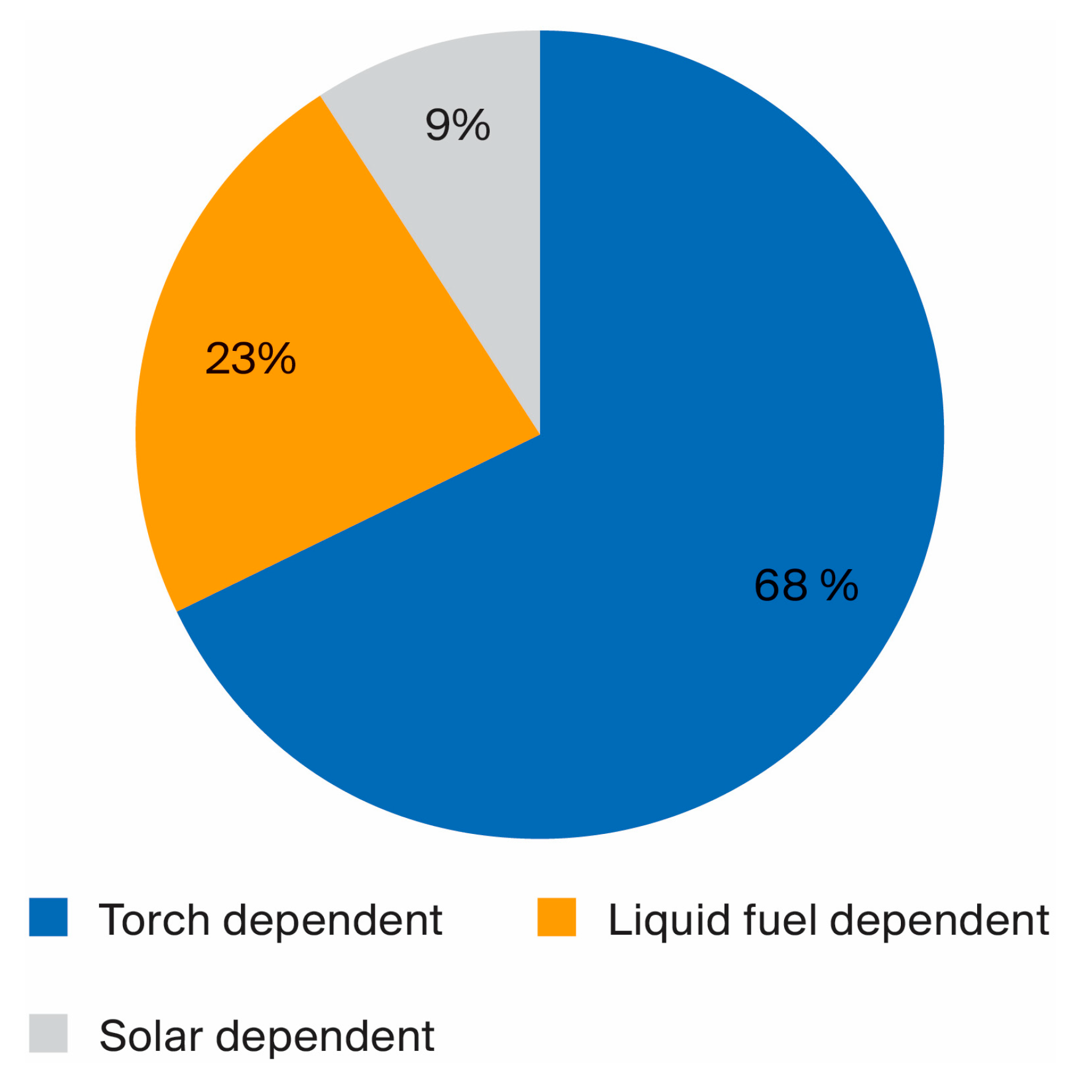

The critical importance of the availability of clean, reliable, and affordable energy services for a qualitive life is reflected in Target 7.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

14], which now explicitly includes displaced persons [

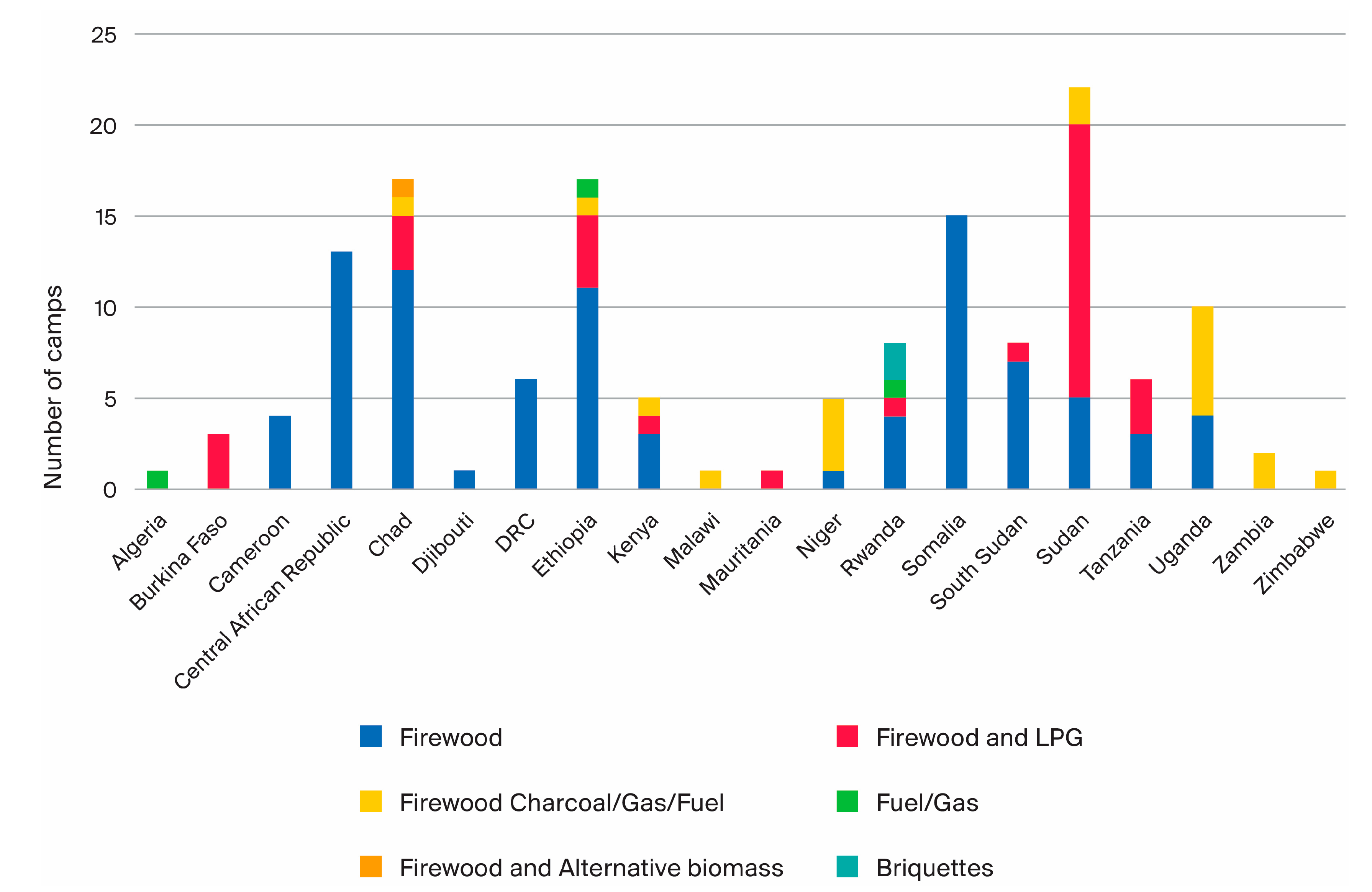

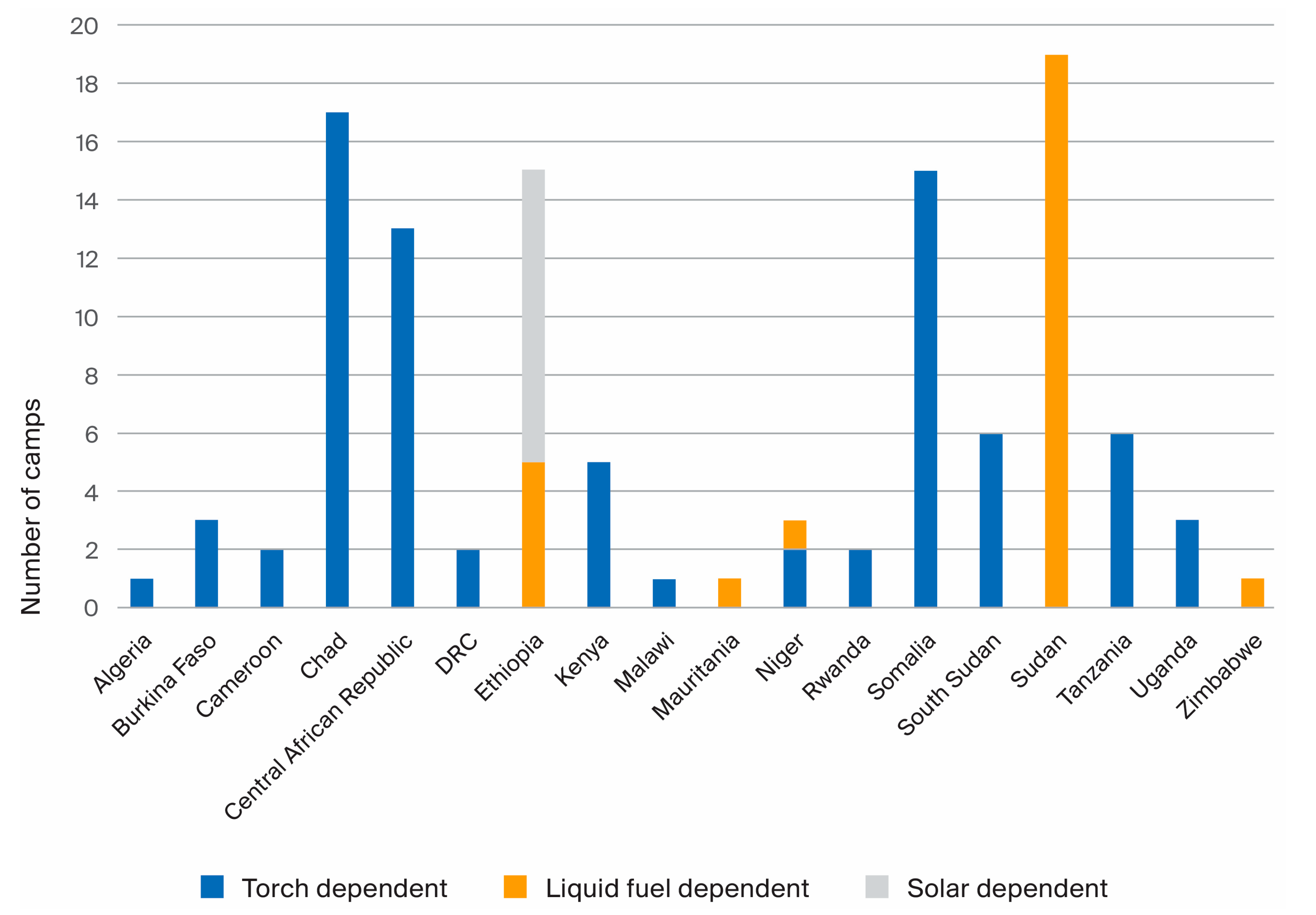

15]. Nevertheless, despite this critical importance, there are fundamental shortcomings in the majority of displacement contexts. The Global Platform for Action, a working group hosted by the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), estimated that in 2022, 94 percent of displaced persons living in settlements and camps did not have access to electricity, and 81 percent of displaced persons living in settlements and camps relied on biomass for cooking [

16]. The limitations in accessing energy services have direct, multilayered, and far-reaching implications, including impacts on health, nutrition, education, protection, and livelihood [

6,

17,

18,

19]. For example, food security is directly linked to a reliable fuel source [

17], the use of firewood for cooking is linked to health risks [

20] - especially respiratory and eye diseases [

7] - and the lack of lighting in public spaces is associated with conflicts, and sexual and gender-based violence [

21,

22].

Besides the direct impact on wellbeing of displaced persons, there is a multitude of downstream impacts associated with the limitations in access to energy. A significant challenge is the high dependency on biomass for cooking leading to environmental degradation [

6]. In some locations this has caused camps being cleared of vegetation in a radius of several kilometers [

23]. The resulting scarcity of resources in turn can fuel conflicts, the consequences of which are especially severe for vulnerable members of the respective communities [

23].

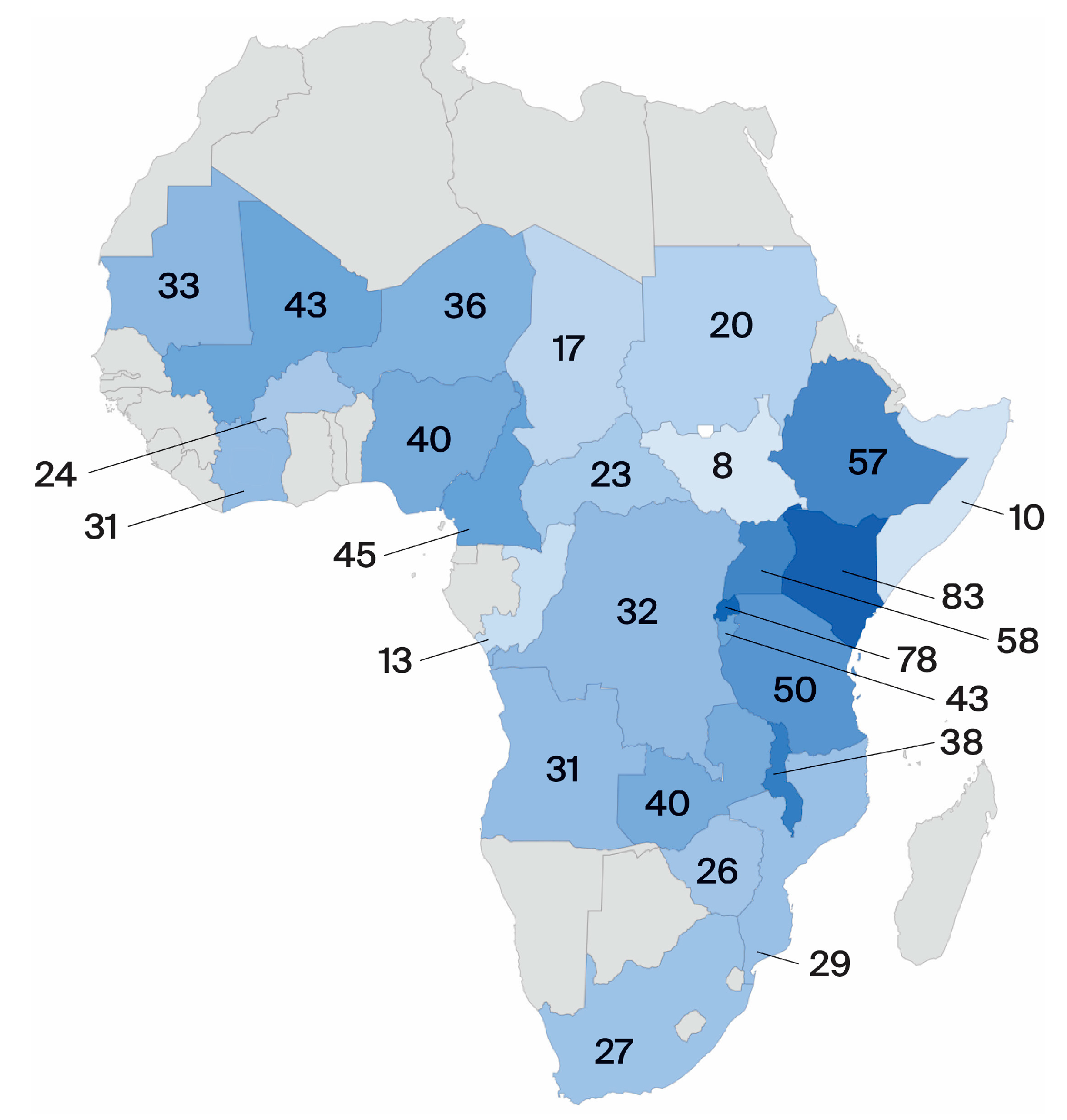

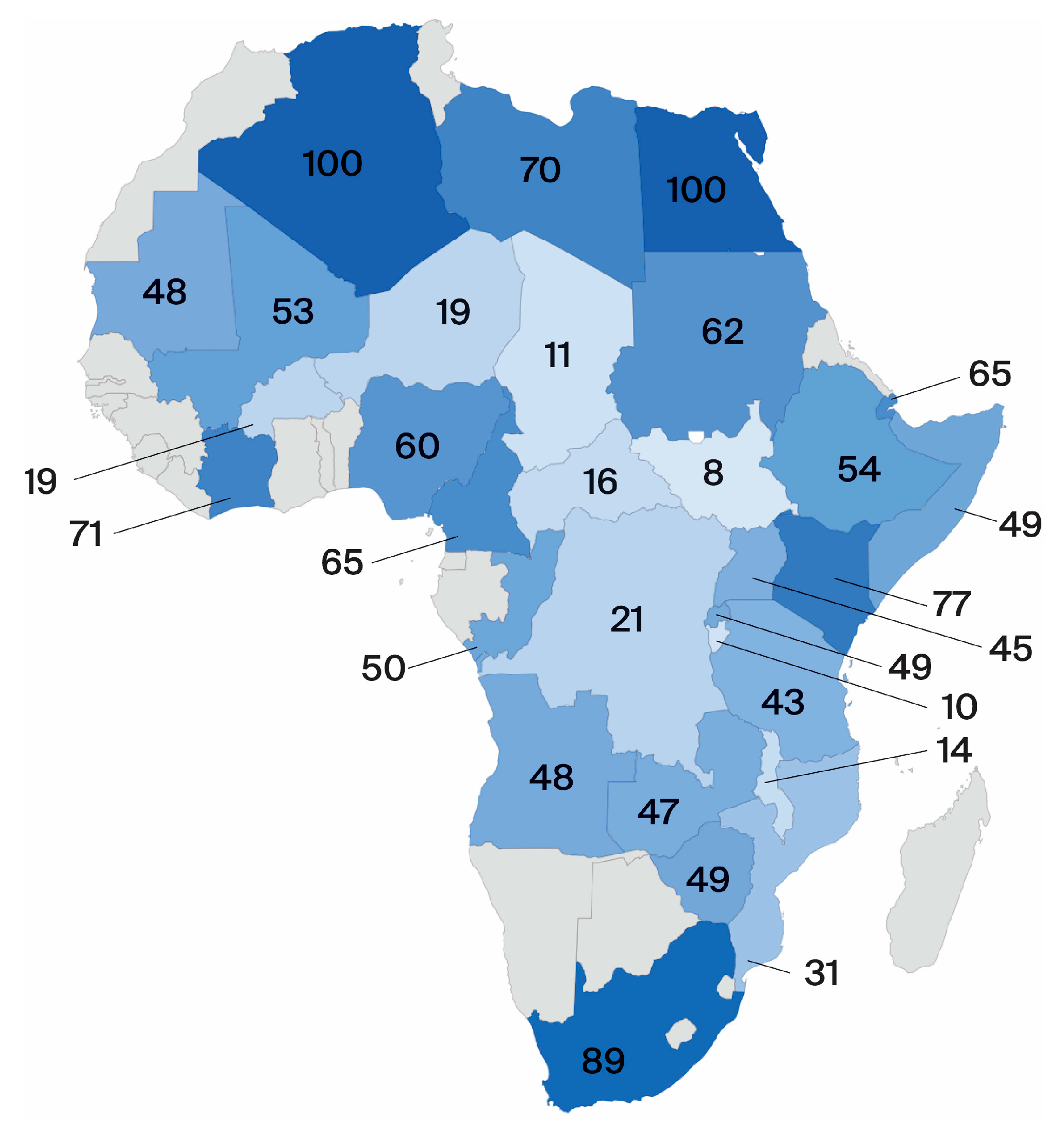

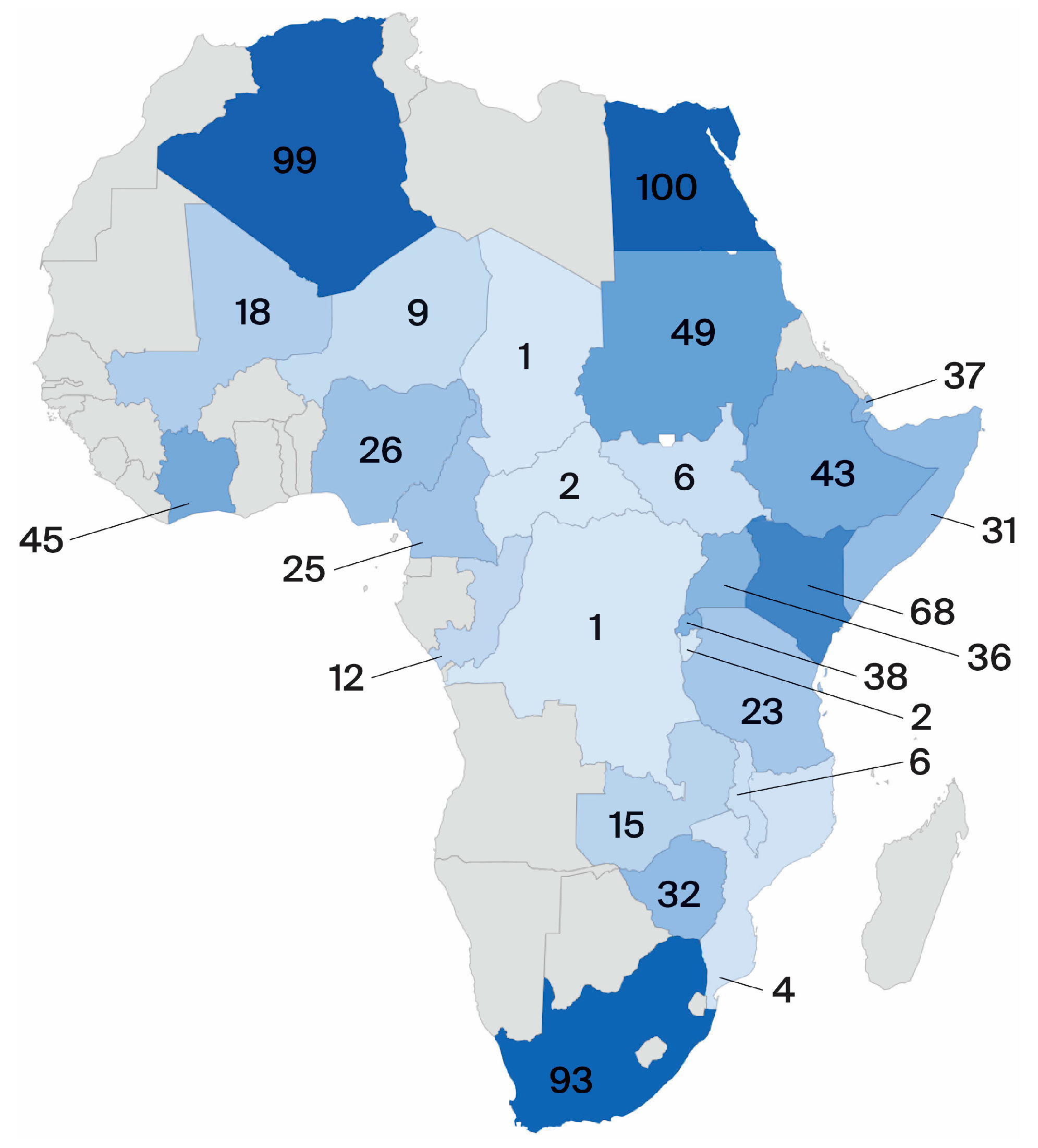

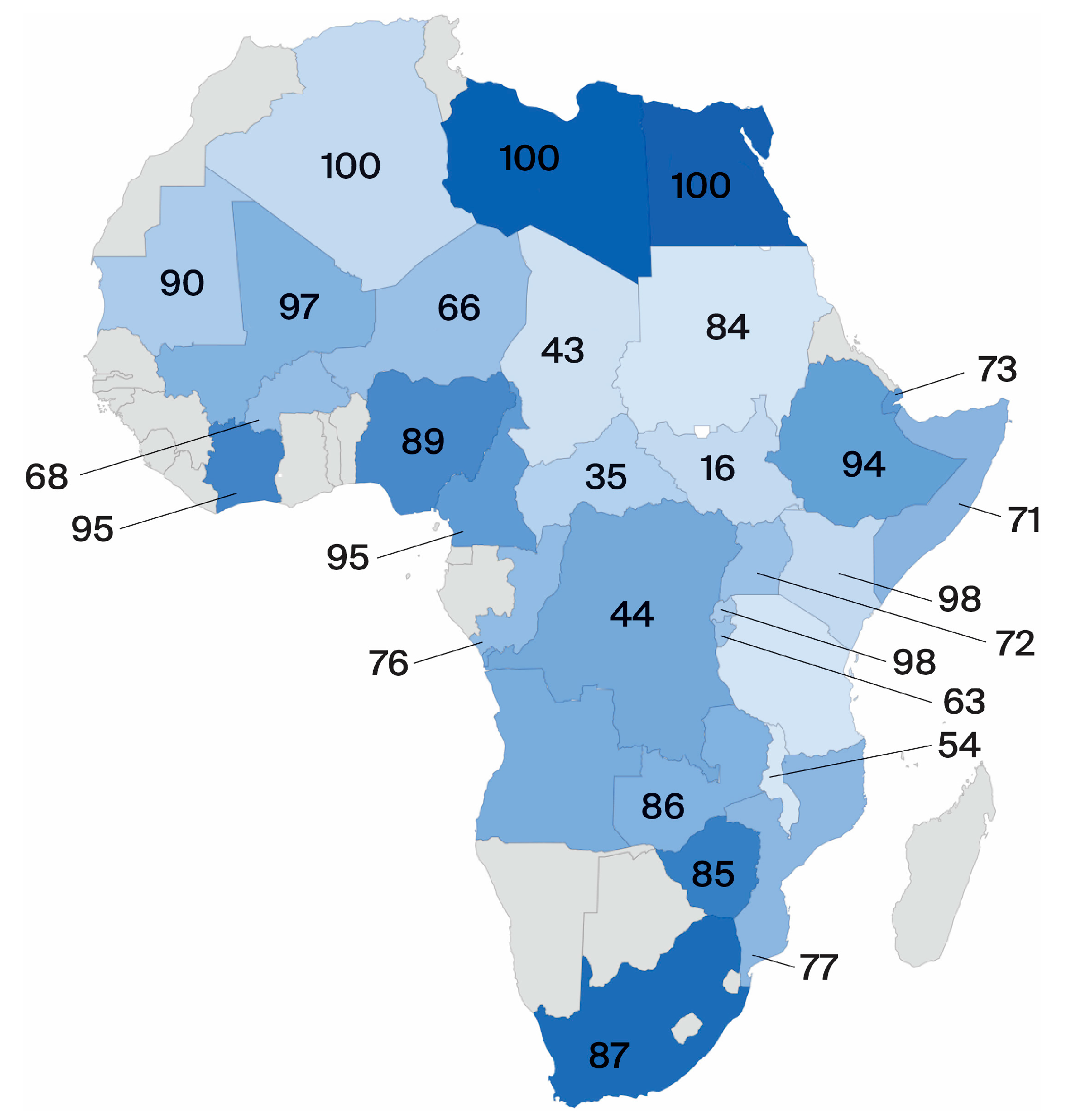

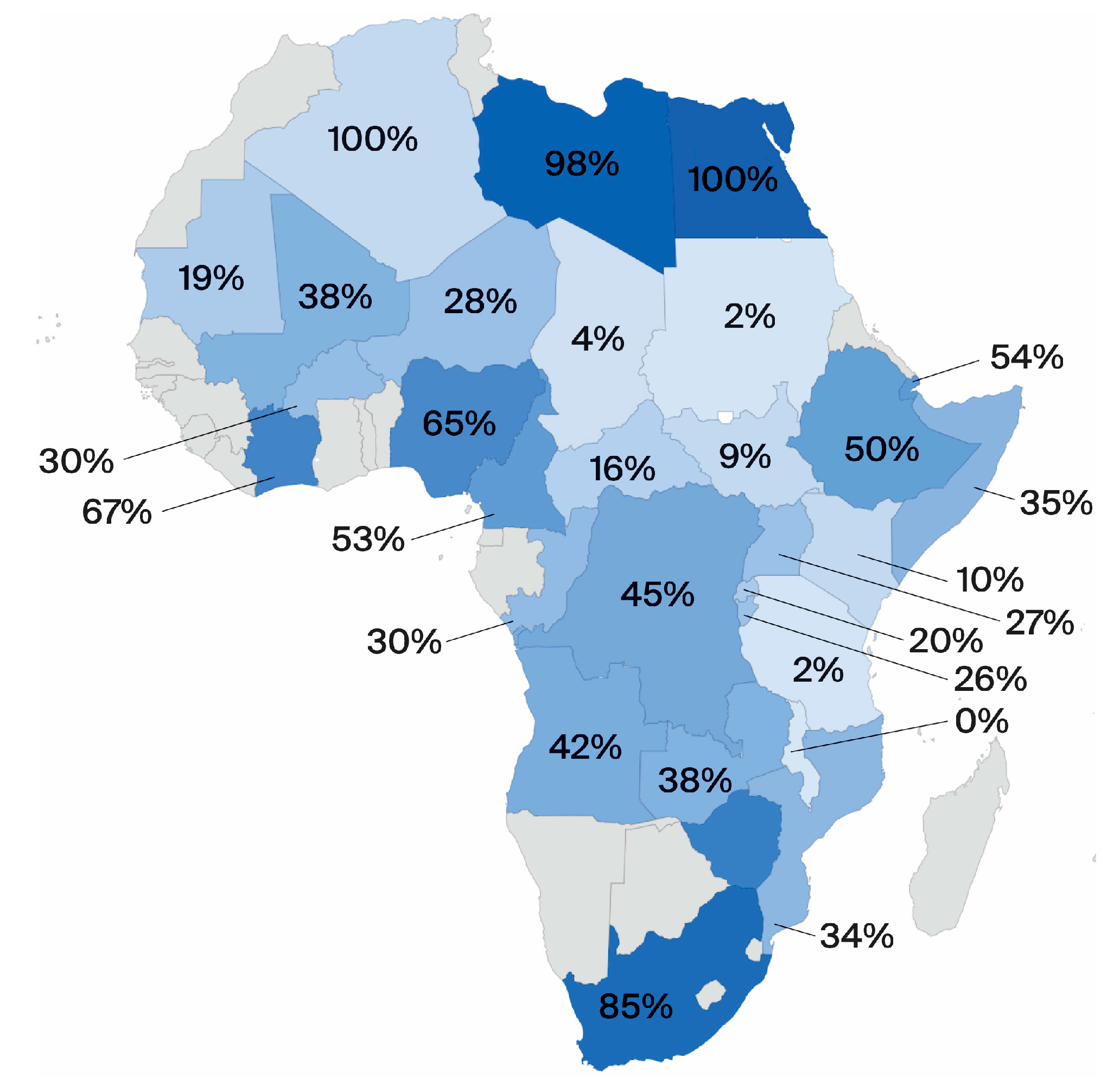

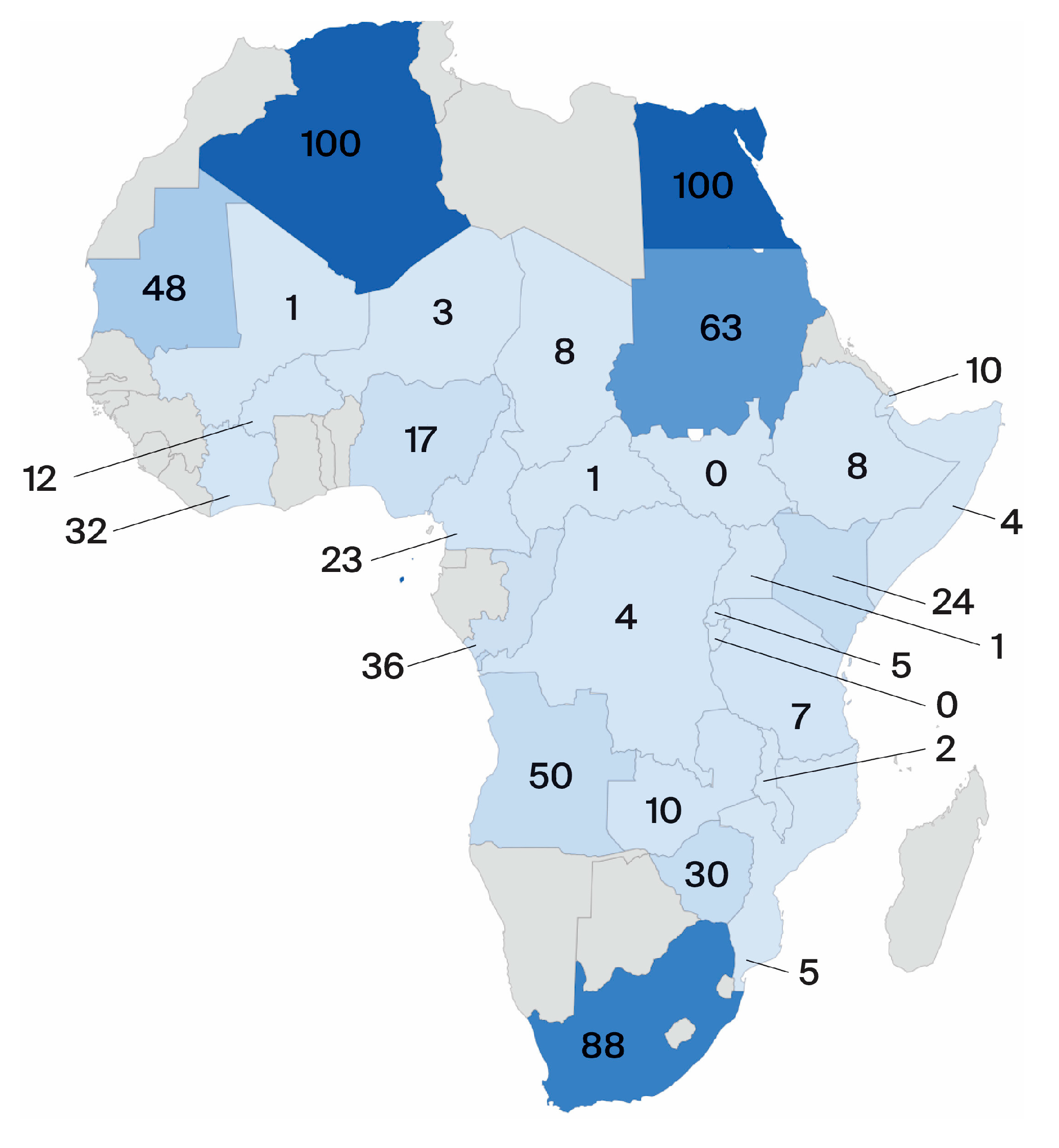

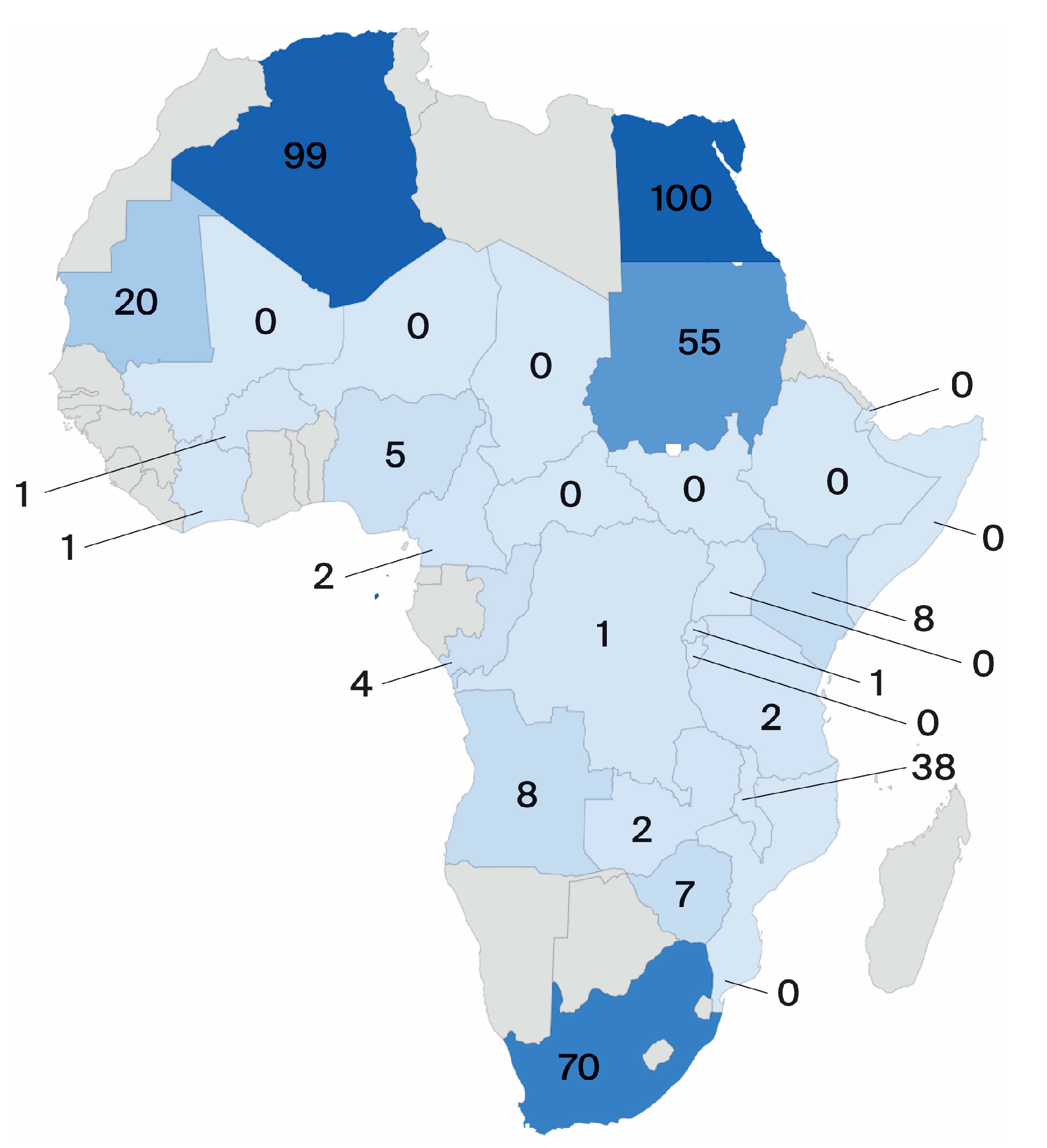

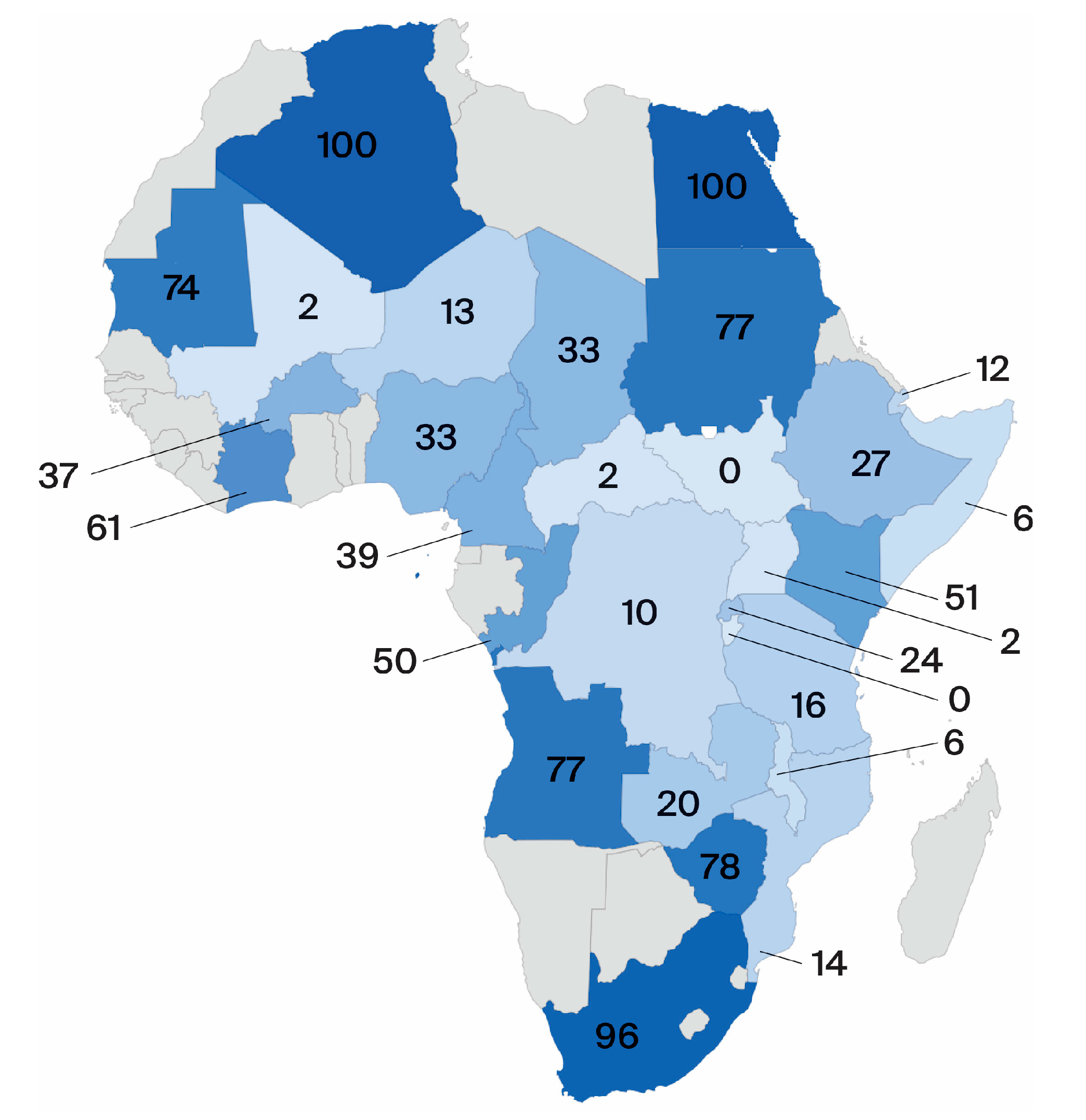

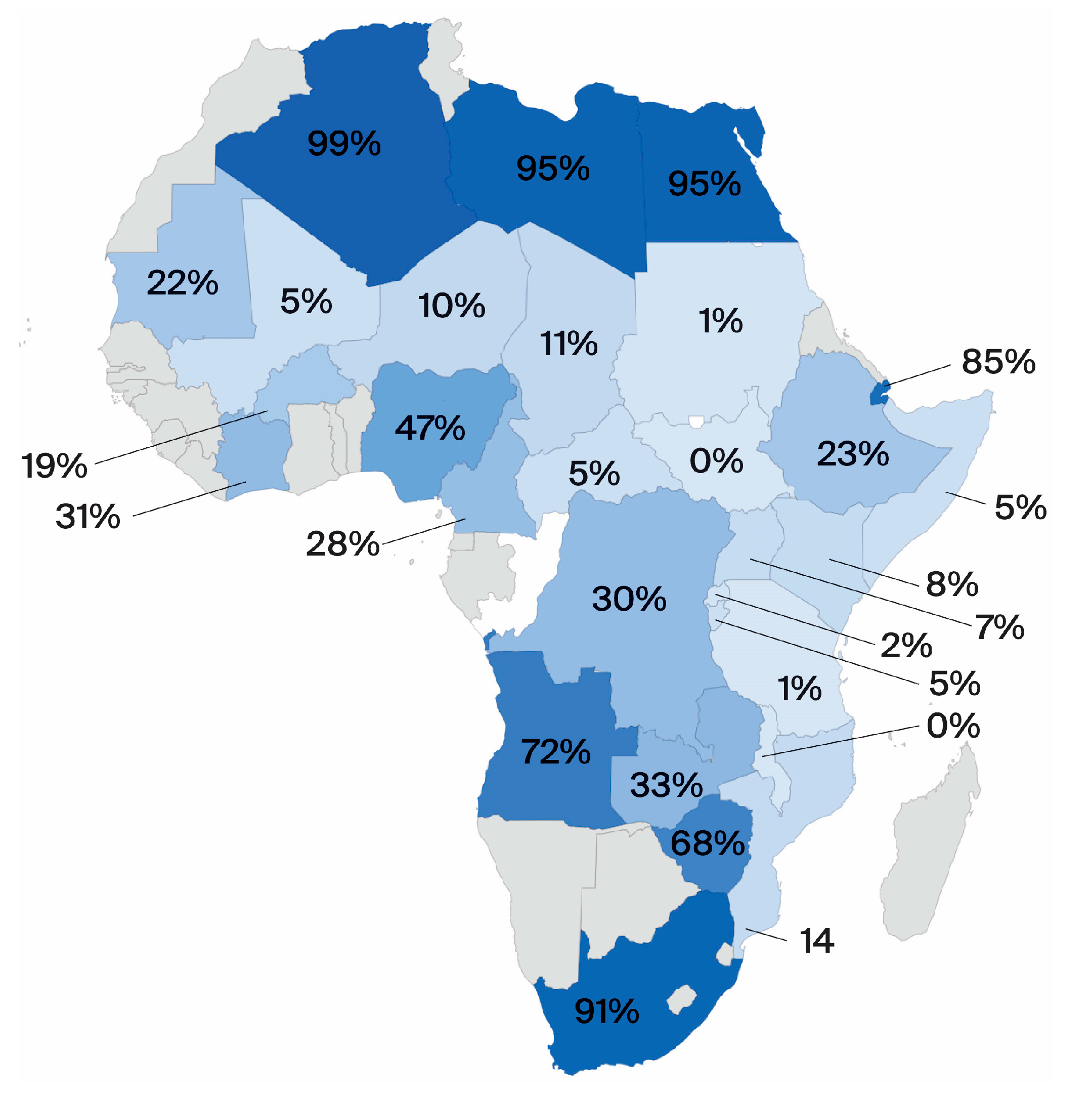

Therefore, international development organisations emphasize and recent publications [

16], [

24] underline, that the affected African settlements have the lowest levels of access to energy in displacement settings and this is, where the most progress is needed to be made. While we acknowledge that research of energy access in displacement settings is critical in all regions of the globe, for pragmatic reasons, this study focuses on the African continent to handle the various information sources and the vast array of data. Also, the majority of the displacement settings in African countries are not connected to an electricity grid whereas grid connection can frequently be found in other parts of the world that have large numbers of displaced persons, specifically in West and South Asia [

16]. Furthermore, the African continent is by far hosting the most displaced persons [

1], which underpins the decision to focus our research on this continent.

While global energy access indicators regarding electricity and clean cooking are relevant to showcase the overall scale of the challenge, it is important to note that access to energy is not a binary condition – grid connected vs. not, cooking with firewood vs. not - but appears on a spectrum [

25]. The Multi-Tier Framework (MTF) of energy access introduced a multidimensional framework that allocates energy access conditions to different tiers, in which Tier 0 constitutes no access at all and Tier 5 constitutes the highest level of access [

25]. In addition, it is significant that access to energy in itself is not a value in isolation, but rather a precondition to satisfy multiple energy service needs [

26].

A further essential consideration regarding access to energy is the diversity of energy demand [

18]. The contextual diversity of displacement settings is mirrored by the contextual diversity of the energy demands, the challenges that are associated with limitations in energy conditions and preferences of displaced persons. In the case of cooking, the associated challenges may be influenced by “culture, geography, season, fuel type, local practices and general awareness” [

27]. Consequently, energy needs are not only determined by the descriptive characteristics of a settlement, but also by individual circumstances and individual preferences. The growing recognition and the increased emphasis of the diversity of energy needs (e.g. [

18,

27,

28,

29]) is not addressable by the predominantly technology-focused and top-down energy interventions in settlements and camps.

1.2. The Levels of Data and the Current State of Affairs

In contrast to other sectors of the humanitarian response system, such as waster, health and shelter, the provision of energy services is not operationalized by established institutional actors [

17,

18,

30] and energy has historically not been a priority in humanitarian response [

19]. Mirroring the increased recognition of the central importance of access to energy on a global level, efforts to further this challenge in displacement settings have increased in the last decade. Thomas et al. [

19] provided an overview of the most relevant institutional initiatives, including the UNCHR’s commitment in 2019 to enable Tier 2 electricity access by 2030 to all refugees as part of the so called Clean Energy Challenge. The increased recognition of the essential importance of energy in humanitarian settings is also reflected in the growing number of scientific publications [

24]. However, the overall scientific engagement with the subject remains limited. Rosenberg-Jansen [

24] identified a total of 115 relevant scientific documents in a literature review in 2022. The limitations in scientific publications accompany limitations in available data. For a small number of host countries case studies were conducted and published in scientific journals that allow basic insights into the contextual conditions of energy access in selected settlements and camps [

17,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37], while case studies documented in grey literature provide additional selective insights [

24].

Both in the research and in the humanitarian response field, the critical role of data has repeatedly been highlighted [

31,

38,

39,

40]. In a consolidating report on the state of energy access in displacement settings, the GPA highlighted the need for evidence and data to inform systemic change as one of their key messages [

16], which picks up on the Working Area

Data, Evidence, Monitoring and Reporting (Working Area V) that the GPA had outline in the Framework for Action in 2018 [

40]. Establishing a realistic and comprehensive overview of the energy access situation is key to inform action on multiple levels. It is essential for policy making to foster integration of displaced persons in national energy access plans [

41], for humanitarian assistance to inform planning and daily operation and for research to further novel concepts and approaches [

24] and for donors to establish relevant funding programs. Therefore, accurate and detailed data is significant to establish a comprehensive understanding of the diversity of energy-related lived realities of displaced persons, which is a precondition for relevant action and intervention on all levels.

Several initiatives have contributed to further the systematic collection and sharing of data. One of the first initiative to systematically assess the multifaceted role of energy in displacement settings was the Moving Energy Initiative, introduced in 2015 by a consortium of organizations and hosted by Chatham House [

42]. In 2017 UNHCR initiated the Integrated Refugee and Forcibly Displaced Energy Information System, which monitors the progress of improved access to energy [

43]. In 2018 the GPA was founded, which has taken up coordination activities, highlighted pathways to efficiently improve energy access and has published contextual insights as part of the READS program [

44]. The Humanitarian Data Exchange platform, which is hosted by OCHA, includes data sets on energy access in settlements and camps [

45].

Despite these recent efforts to improve the information base on energy access in displacement settings, the insights, and the data on energy access in settlements and camps remains dispersed and fragmented. Numerous scientific articles state the lack [

16,

39,

46] and the poor quality [

24,

39,

47] of available data, which is rarely harmonized across the levels from individual over communal to regional and international spheres and therefore insights differ, and comparisons are barely justifiable. While one source might describe the individual level in a country while another one might do so too but uses different definitions of the type and the units of data, what hinders integration and joint usage. Because of the general lack of data and the lack of cohesion, the state of energy access in settlements and camps in large parts are unknown. This is a fundamental limitation as a comprehensive information basis constitutes a basic building block to further energy access in displacement settings from a policy, research and implementation perspective.

The objective of this article is to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the current state of energy access in displacement settings by identifying and utilizing existing data. After a screening of the vast and various available information, setting up of a database, consolidating the gathered data as well as assessing the quality through a quality assessment method, the currently available information is visualised and discussed. As far as the overview allows, conclusions are drawn, as well as current content and structure to the initial and pressing issue of improving access to energy for displaced persons are mirrored. Two research questions are addressed:

(1) What insights can be gained from the available data on access to energy in displacement contexts in several countries of the African continent?

(2) What are the limitations?

(3) What are the differences between multiple countries?

The character of the issue at hand and the fragmented state of the current affairs motivates to map and investigate differences between multiple countries and therefore include transnational data sets. The claim of limited data availability is tested. While available data from case studies are excluded given their small percentage share of total available data as well as their more extended differences in the type and composition of numbers, the identification of relevant data for the description of the state of energy access in displacement settings inevitably raises the question of assessing the quality of the data that we identify. We therefore include a systematic quality assessment in our study and tailor a data quality assessment procedure to the needs of our study.

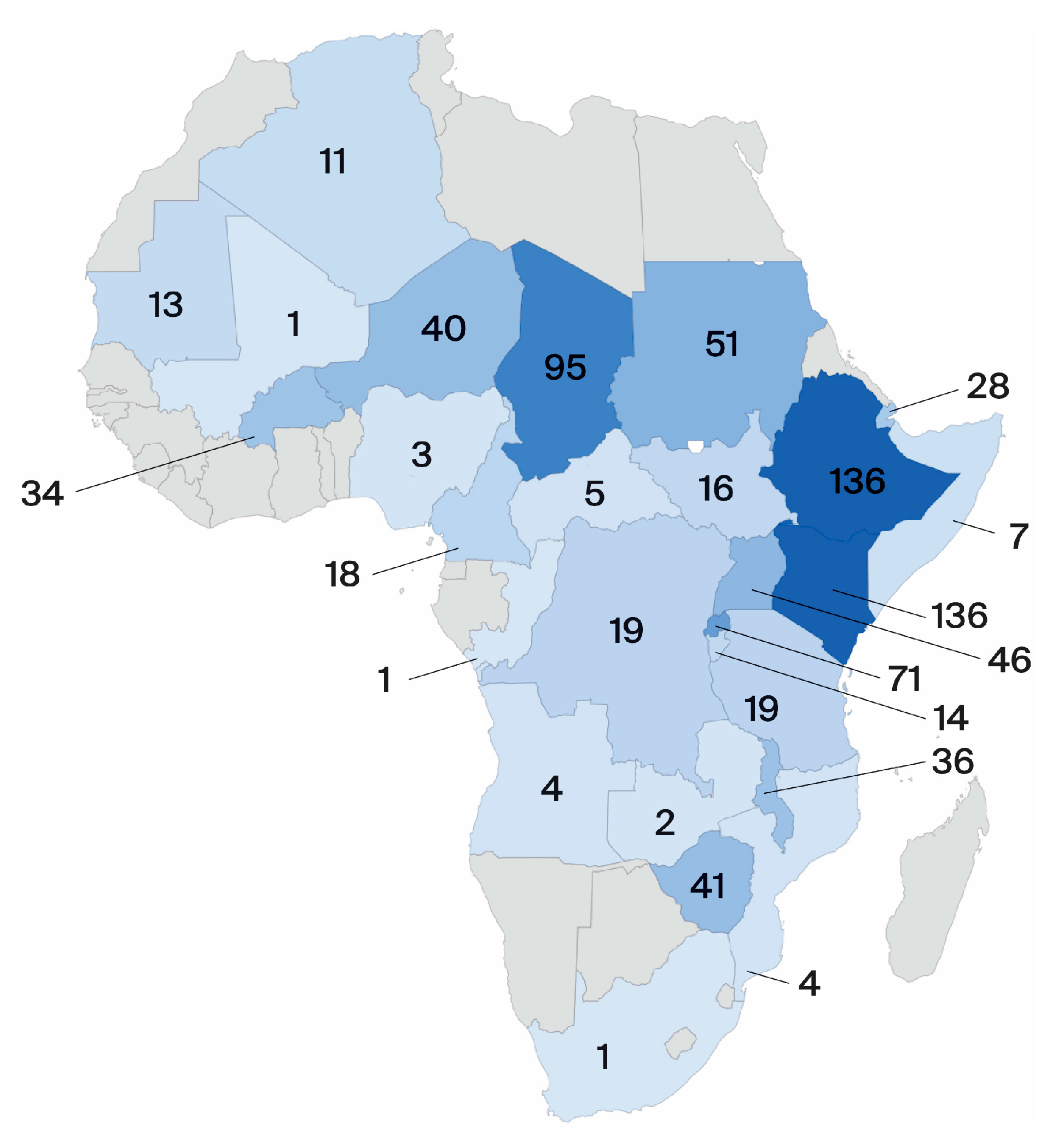

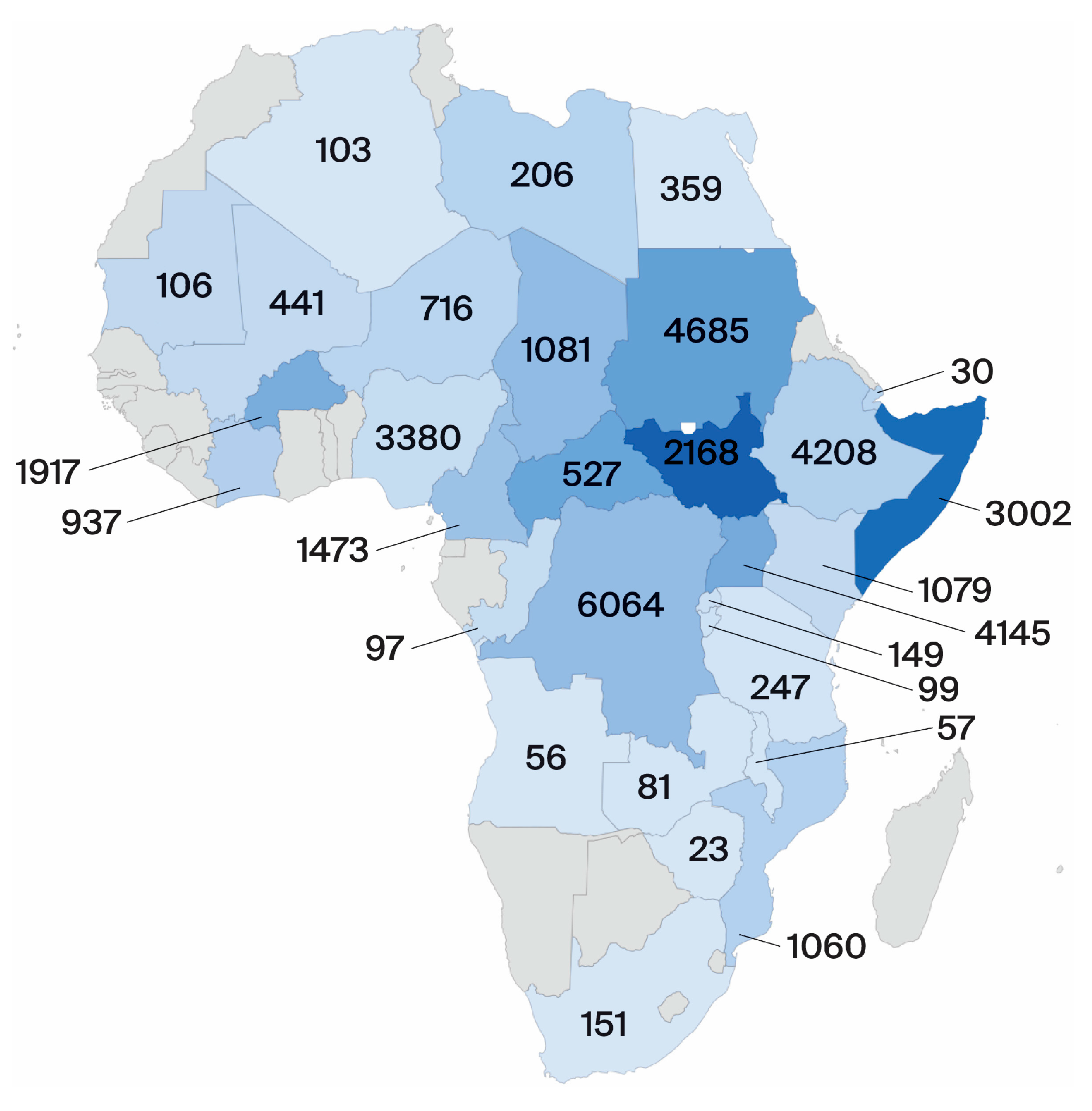

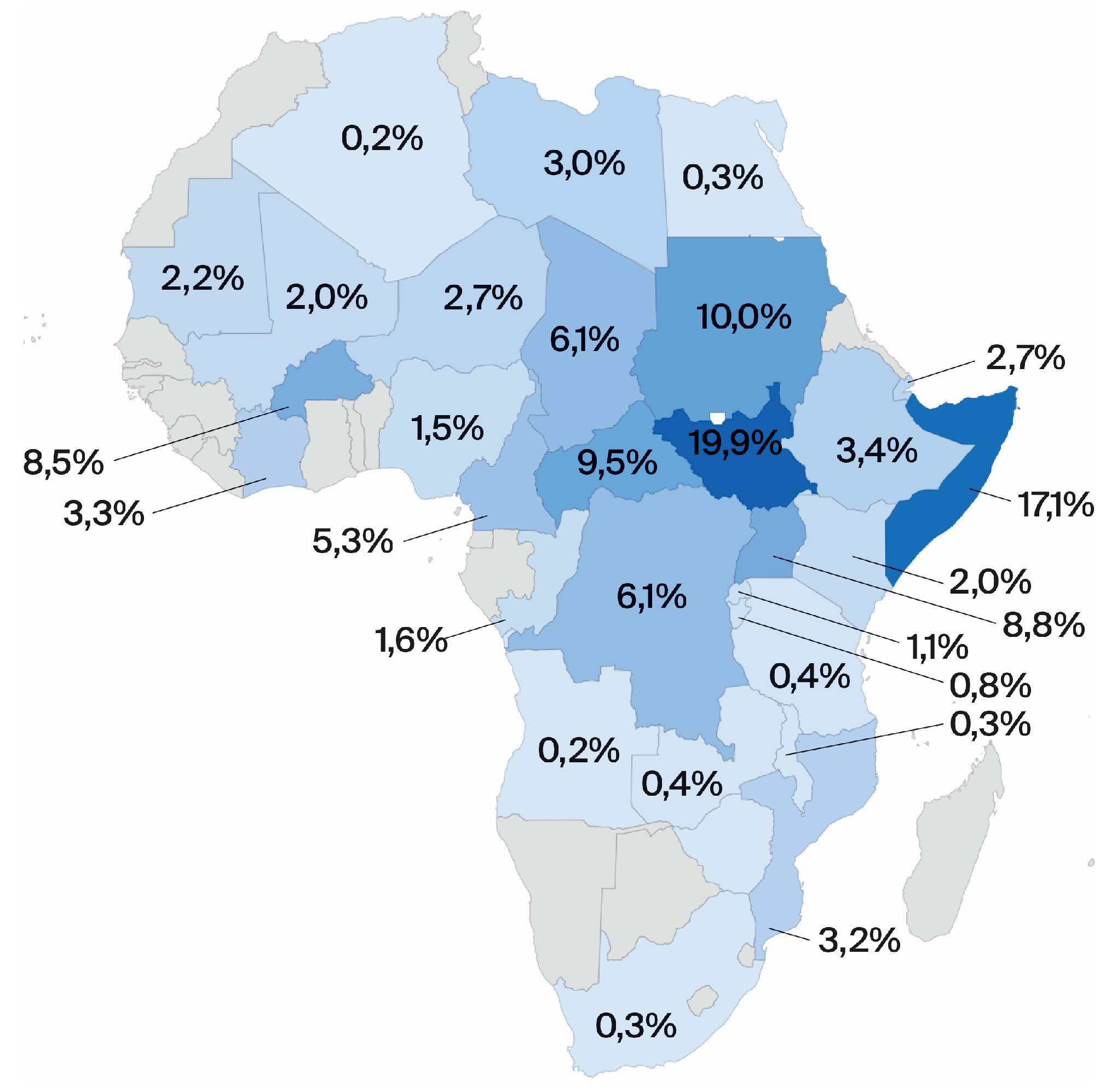

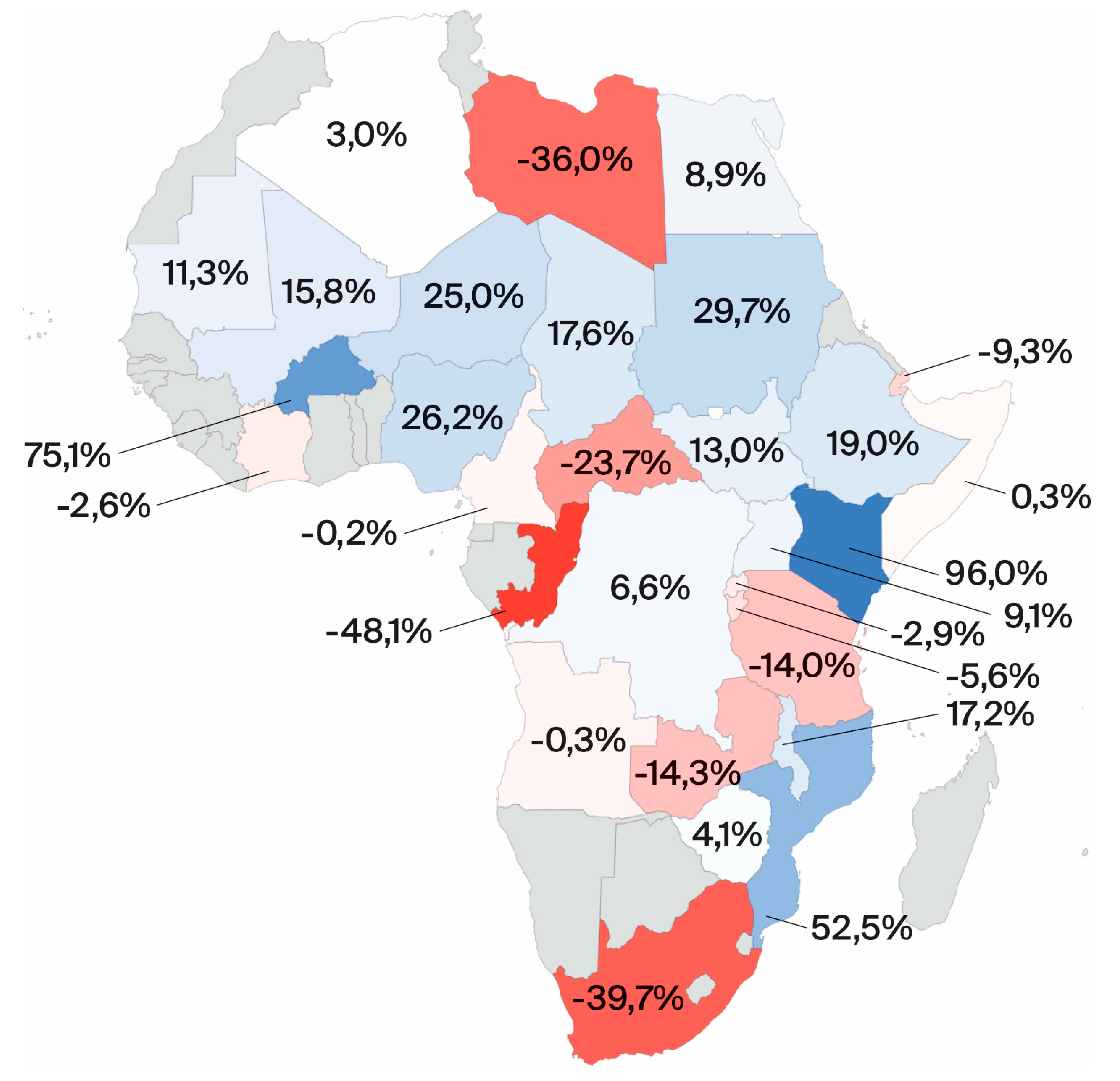

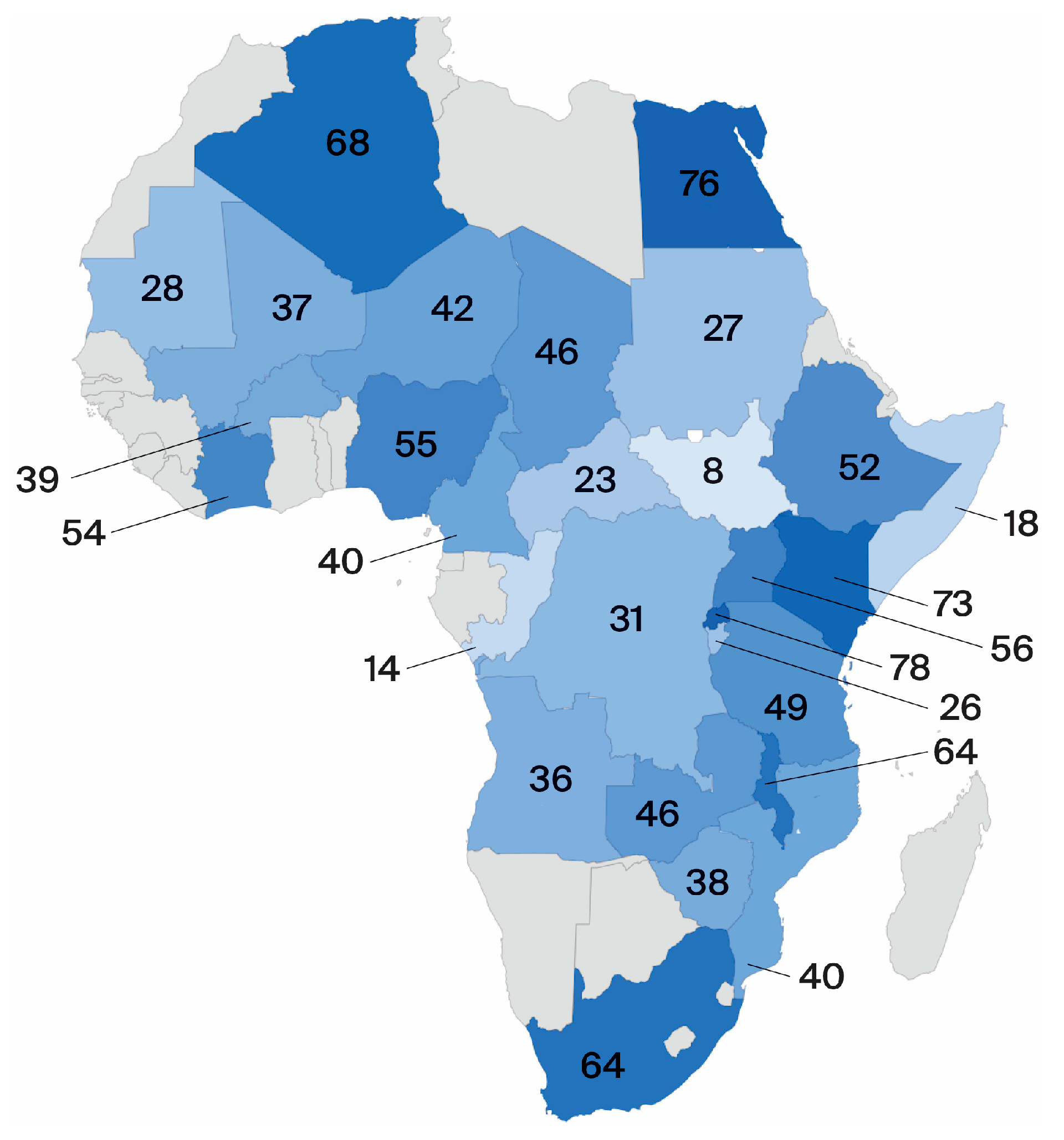

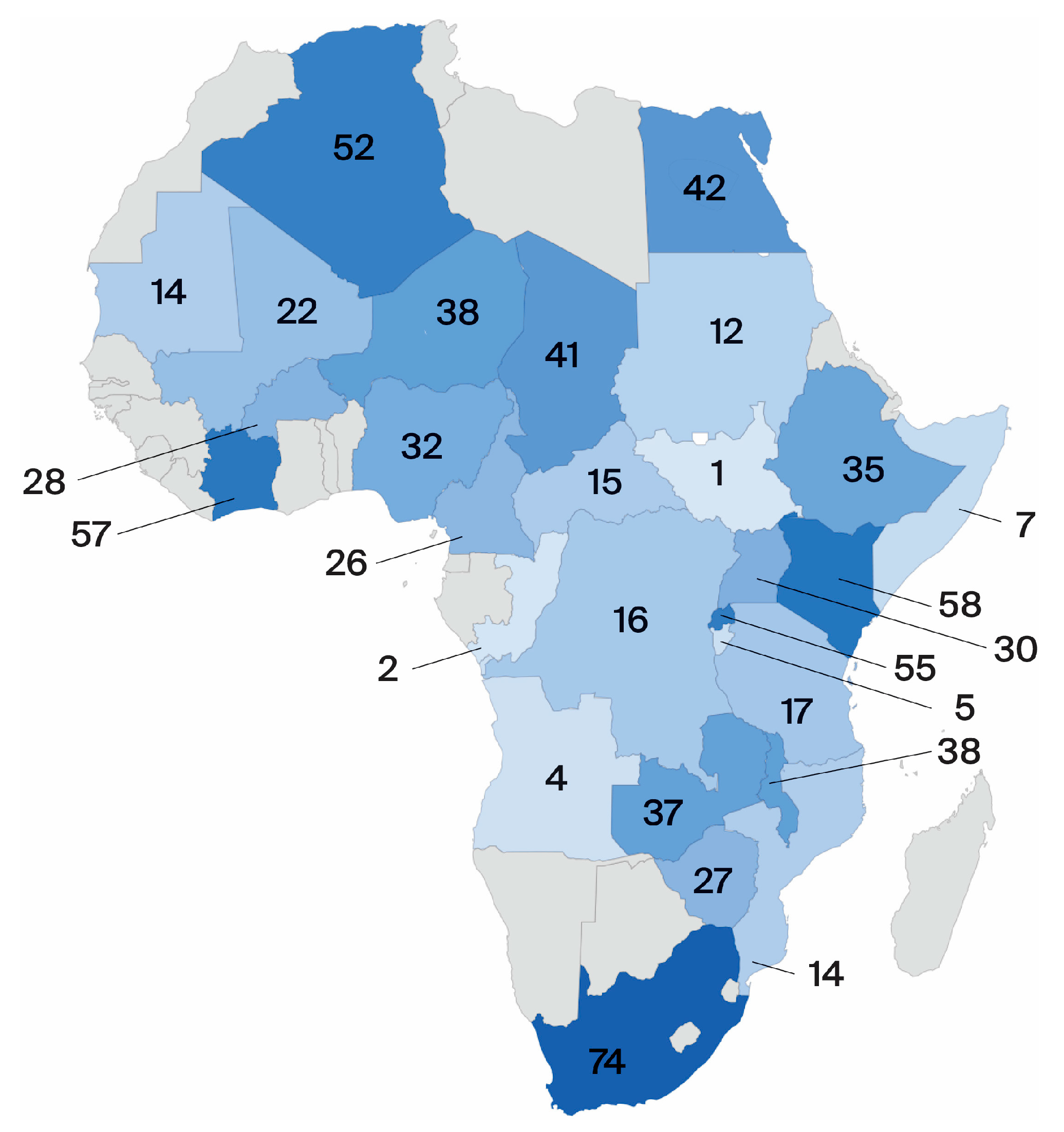

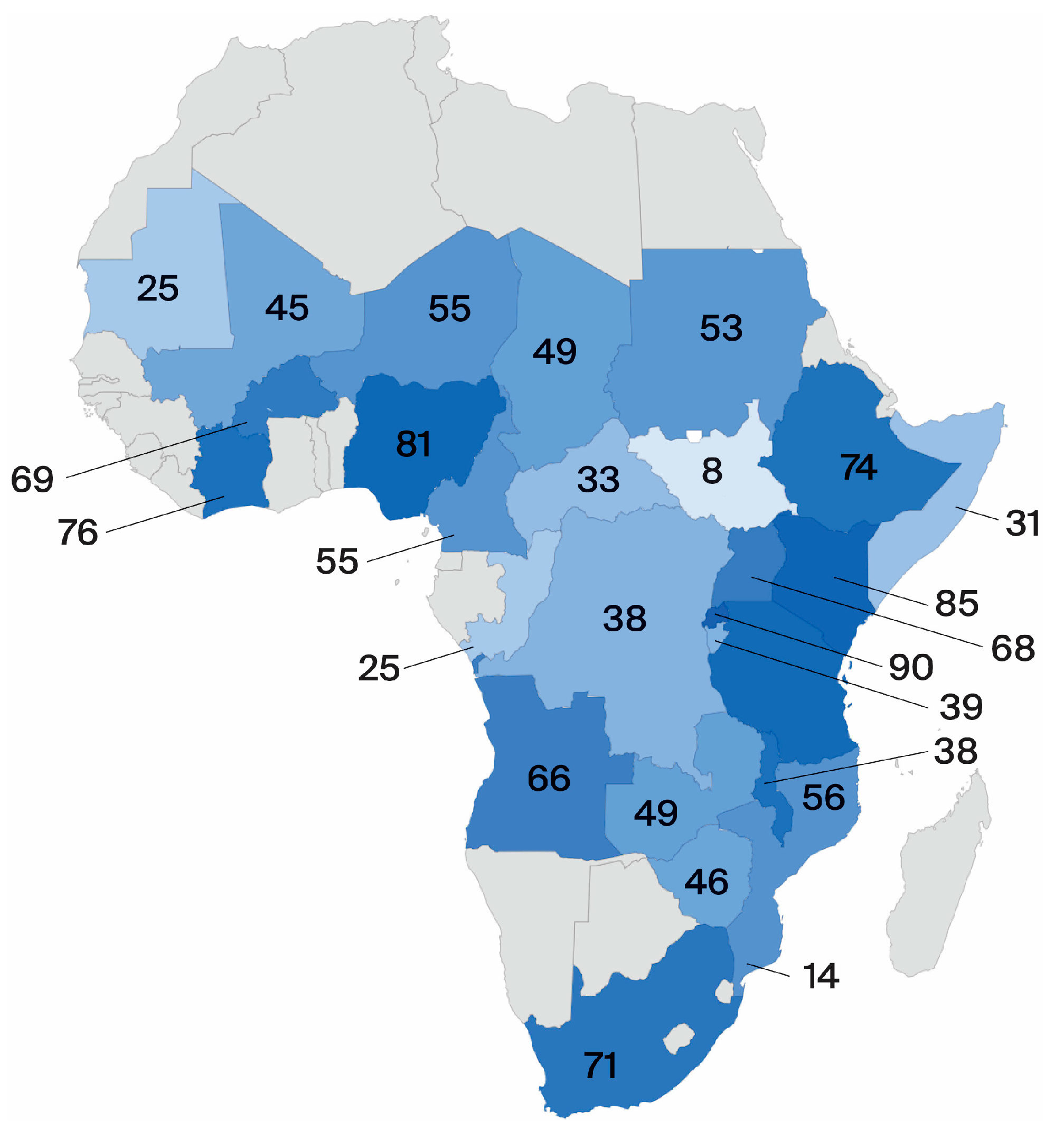

The number of displaced persons varies considerably by country [

48] and so does the available information about the related displacement setting. Countries with a smaller population of displaced persons show little to no available data on energy access [

24]. This fact directs this research to countries with available data and thereby to those with more than 20,000 displaced persons, resulting in 30 African countries result, jointly accounting for 99.8% of displaced persons across all African countries [

48]. The countries of this study are listed in

Table 1.