1. Introduction

Air pollution from road traffic is

a combination of exhaust emissions (a mixture of gaseous pollutants and

particles from fuel combustion and the volatilization/degradation of lubricants

at the tailpipe) and non-exhaust emissions (mechanical abrasion of brakes,

tyres and road surfaces, resuspension). Road traffic is a major contributor to

non-exhaust emissions which are dependent on weather conditions [1–3], topographical factors of the

built environment in cities as well as road structures [4–6].

Deterioration of air quality in

cities has become a major concern together with environmental and health

impacts [7–13]: there

are more than 430,000 premature deaths every year in Europe and 7 million/year

around the world

[14,15]. Many phenomena can occur during particle exhaust emissions, such

as: atmospheric resuspension of particles, mixing – dispersion, coagulation,

evaporation, dilution and turbulence, resuspension

[16–23]. Kwak et al.

[24] indicated that particles

emitted by tyre wear, in laboratory tests, are in the range of 2–3 μm, while

road surfaces create larger ones. Measuring particle emissions from the

tyres-road wear is complex, in particular because it involves mechanical abrasion

and the resuspension of wear particles deposited on road surfaces

[25]. In fact, a non-negligible

percentage of particles may be deposited. Compared to fine and ultra-fine

particles, these are mainly of large size

[26,27]. Jeong et al.

[28] confirmed that Cr, Ni, Cu, Zn, As, Cd, Sn, Sb, Pb are the major

non-exhaust pollutants emitted by road transport. Indeed, the significant

components of tyres are SBR styrene rubber, butadiene rubber, natural rubber,

organic peroxides, nitro compounds, selenium zinc, and other metals

[29–31]. Kreider et al.

[32] confirmed that the elements

(Ca, Fe, K, S, Zn, Mg, Al, Si, Ti) are emitted from road materials. Zinc

compounds is a tyre marker

[33,34]. Hildemann et al.

[35] and Gustafsson et al.

[36] cited Zn among the elemental compounds. Dahl et al.

[37], Pant and Harrison et al.

[38], and Harrison et al.

[39] found that tyres contain about

1% Zn as inorganic Zn such as ZnO and ZnS, and organic compounds. Khardi et al.

[6] suggested the S

and Zn as tyre tracers. Beji et al.

[40], Khardi and Bernoud-Hubac

[27] confirmed that C, S, Cr, Cu, Ce and Zn compounds are emitted into

the air by road vehicles. They confirm that Zn is a particle tracer of tyre

emissions. Particles emissions are generally thermal in nature due to friction

with the road surface. Harrison et al.

[41] indicated that the emitted non-exhaust particles are in both the

coarse (PM2.5-10)

and fine (PM2.5)

fractions, with a larger proportion in the former.

Effects of particle emissions by

road traffic on human health and environment have been regularly reported

[42,43]. The major observed impacts

are related to the cardiovascular system (strokes and ischemic heart diseases),

lungs inflammations, asthma, chronic lungs diseases, cancers, pulmonary

fibroses, …

[10,22,23,44–53]. It would be very complex and useless to indicate all the found

references on this topic. The literature describing health impacts and

toxicological studies regarding road traffic emissions is very extensive and

reflects the severity of transport particulate emissions. Many given analyses

are based on particle sizes but very rare analyses resulted in studies of these

impacts according to the chemical composition of the emitted particles.

Chronic diseases such as asthma,

cancers, and heart diseases are well documented in the open literature; they

are associated to pollutant exposure. It is confirmed that road transport

contributes to the described impacts

[21–23,39,41,54].

Few reliable and specified

information exists on biological mechanisms and toxicology of non-exhaust

particles

[55–59],

especially those having the potential to penetrate cell membranes, and / or

penetrating the lung alveoli

[16,54,57,60–62].

Liu et al.

[54] suggested that highest

particle counts were observed in the size range of 0.25-0.5 µm, and can be

extended to the interval 0.25-10 μm. Particles can reach the alveoli, thus

causing toxic effects in the lungs

[63]. Particles less than 0.5 µm enter the bronchi and lungs. Between

0.1 µm and 1 µm fine particles can therefore penetrate deep into the

respiratory system. This highlights the link between the mechanical properties

of the particles and the risk that they are deposited in the respiratory

system.

Some of them can pass through the

lung epithelium and can be transported in the blood to other organs

[64]. The main effect on cells

would seem to be the formation of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress.

Genotoxic damage was observed with

an increase in micronucleus formation and TNF-alpha release from lung

macrophages

[65],

which can have serious health consequences

[66,67]. Kreider at al.

[68] suggested a risk assessment calculation for humans considering

exposure duration.

The largest particles are stopped

by inertia in the nasopharyngeal segment, but the smallest particles (less 2

µm) are also stopped by Brownian diffusion. Above 10 µm particles are stopped

by the nose and do not enter the respiratory system.

This paper focuses on the

so-called non-exhaust emissions by the tyre-road friction. It presents an

original experimental work related to the particle’s emissions by the abrasion

of tyres and road in real driving conditions in urban, suburban and highway

areas. Therefore, the results on emission factors are the fruit of a new method

coupled with a fine and efficient analysis. The effective new method, based on

Multivariate data analysis (Hierarchical Classification on Principal Components

‘HCPC’), was used to investigate clusters of size distribution and pollutants

identification (chemical characterization). The method was carried out in

three-stage: Initially, a specification of the most predominant granulometric

intervals of tyre-road emissions; Secondly, an analysis of the chemical

composition of the emitted pollutants and their importance; Finally, the

provision of the emission factors of the road-tyre pollutants supported by a

solid statistical analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Set-Up

Experiments were carried out in

and around the city of Lyon (Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Region, France) in three

different experimental conditions (urban, suburban and highway) during the

summer period. The road traffic was very heavy in Lyon and its suburbs with

about 180,000 vehicles a day. 70% of the vehicles travel less than 3 km

[69]. As regards the highway,

85,760 vehicles travel every day, of which

were trucks and 81% light

vehicles [70].

Table 1 presents measurement features (type of road, travelled distances,

average meteorological conditions) during experiments in real-time driving

conditions. The experiments were carried out on a total distance of 1,950 km:

450 km in urban areas, 650 km in suburban boulevards and 850 km on the highway

(Figure 1).

Table 1.

Real driving conditions (wind speed less than 4 m/s).

Table 1.

Real driving conditions (wind speed less than 4 m/s).

| Type of route |

Distance travelled per trip |

Average temperature (°C) |

Strength of the wind (km/h) |

Relative humidity (%) |

| Urban (U) |

45 km |

17 |

7 |

45 |

| Suburban (SUB) |

65 km |

15 |

11 |

39 |

| Highway (H) |

85 km |

18 |

8 |

53 |

Figure 1.

Experimental areas (A, B) and altimetry (C) where data were collected in urban, suburban and highway areas in real driving conditions.

Figure 1.

Experimental areas (A, B) and altimetry (C) where data were collected in urban, suburban and highway areas in real driving conditions.

The topographical map of the city

of Lyon (surface area, 47.87 km2) and its surroundings are given in the

Figure 1. The average altitude

of the city and surrounding area is 210m, the minimum is 161m, and the maximum

is 333m (Altimetry of Lyon, 2023). The urban environment of Lyon presented an

average road gradient of 12%, with the steepest gradient at 30%. In suburban

and motorway environments, the average gradient was 3 % on 70% of the

experimental routes, and 4.2% on the remaining 30%.

The instantaneous speed of the

vehicle and position have been collected using a global positioning system

under real-world monitoring with a sampling of 1 Hz. The duration of each experiment depended on the road type and the fluidity of the

road traffic.

In this experimental work, the

simultaneous measure of sizes of particles (granulometry) together with the

collect of particles on carbon adhesive tabs (ϕ =12 and 47 mm) and on

polycarbonate Whatman® Nuclepore™ Track-Etched Membranes (ϕ = 25 mm,

pore size 0.4μm) enabled the analyses of their chemical composition and

identification. Membranes were considered free of traces of the chemical

elements Si, Sb, S, Fe, Mg, and Na. They ensured no contamination (high

chemical resistance, good thermal stability, smooth flat surface for good

visibility of particles). No distinction can be made between tyres emissions

and road abrasion emissions. All measuring instruments

were synchronized. An electronic device, having a fixed impedance, has been

used by injecting a square wave signal every 5 minutes to guarantee a

synchronization between measurement systems. An optical particle counter ‘OPC’

GRIMMTM EDM 180

[73]

was used to measure particles concentrations (diameter range [0.35µm,22.5µm])

with a flow rate of 1.2 l/min and 0.1μg/m3 resolution. This OPC is a

real-time measurement in ambient air of PM10,

PM2.5 and PM1. It is considered as an automated monitoring system using a

diagnosis software system. It has an efficient counting statistics and

reproducibility of dust concentrations with low to high levels. GRIMMTM EDM 180

has been calibrated in the Grimm Group company using a dolomite dust. In

comparison with other existing laboratory systems used in this research field,

the preference for the GRIMM system was due to its easy operability and

effectiveness (small size, light weight, high battery life, low power

consumption, large data storage capacity, 12 V power supply, …). All the used

data collection systems were synchronized thus allowing a good results

explanation of the observed data. Before every measurement campaign, zero

calibration was regulated on the GRIMM. During experimentation, a Global

Positioning System (GPS) was used to collect the vehicle trajectory parameters,

its speed and acceleration. Temperature of brake pads was also recorded in

real-driving conditions. All measured signals were synchronized.

Each measurement was followed by

blank tests lasting 15 minutes each in order to remove any impurities that may

have been present in a residual way in the GRIMM pipe. Summer tyres were used

to study particle emissions caused by the abrasive contact between the tyres

and the road surface.

The two following sampling points

were: 1. In the middle of the wheel inter-axis, 3 cm from the road surface. 2.

Behind the wheel at 2 cm from the middle of the wheel and 3 cm from the road

surface. The inlet sampler pipe was fixed in the vertical axis of the wheel.

The particle collection tube has a diameter of ¼”.

Figure 2 shows the

experimental configuration of the light vehicle.

Figure 2.

Two measurement points: 1. Behind the wheel (2 cm from the middle of the wheel and 3 cm from the road surface). 2. In the middle of the wheel inter-axis, 3 cm from the road surface. The particle collection tube has a diameter of ¼”.

Figure 2.

Two measurement points: 1. Behind the wheel (2 cm from the middle of the wheel and 3 cm from the road surface). 2. In the middle of the wheel inter-axis, 3 cm from the road surface. The particle collection tube has a diameter of ¼”.

The exhaust pipe was located

outside of the vehicle on the left rear side. Thus, the installed car exhaust

extraction system is a 6 cm diameter tube attached to the exhaust pipe (20 cm

length, followed by a 90° elbow and a 170 cm high tube). This configuration had

the advantage of avoiding a mix data collection between exhaust and non-exhaust

emissions. Control tests were carried out to ensure that the exhaust and

non-exhaust mixture of emissions was not collected by the measurement system.

Indeed, the sampling probe was placed in the centre axis between the wheels and

at a 3 cm distance from the road surface. This ground distance confirmed the

absence of exhaust particles in the collected data. However, measurements in

this position showed that resuspension-induced particles were found. The

position of the sampling, due to the screen effect of the two wheels,

guaranteed that 98% of the collected particles were emitted by abrasion due to

contact between the tyres and the road. The tests were carried out on days when

road traffic was very low, off-peak hours, to avoid cross-contamination from

other vehicles.

Brake system temperature control

and exhaust emissions: the control of the brake temperature was an important

element to analyse the exhaust emission rate, and subsequently the potential

contamination of the collected tyre-road data. Indeed, the increase in brake

friction could have had an impact in terms of contamination of measurements at

the tyre-to-road contact point. This is one reason why the brakes temperature

was followed during the experiments because the latter gave an information on

their emission rate. A specific system to monitor these emissions was not

installed but the brakes temperature was controlled in case some data seemed

inconsistent. For this reason, tapered metal plates were installed on the back

of the four wheels to avoid this possible contamination. The measured brake

temperature is given in the following Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Control of average brake temperatures during road travels.

Figure 3.

Control of average brake temperatures during road travels.

Temperature of brakes has the

advance to be able to give to the research in tribology or dynamics of the

contact some knowledge elements on the behaviour of the braking systems. The

measured average temperatures in urban, suburban and motorway experiments are

respectively 17°C, 47°C and 56°C. The maximum temperatures reached are

respectively 147°c, 387°C and 482°C. The increase of the brake’s temperature

occurs largely during the suburban and highway experiments (braking due to

speed). With the dynamics of the vehicle in real driving conditions, no

contamination of the experimental data was observed. Moreover, the results of

the presented chemical analyses confirmed this. This precaution, to which was

added the installation of a casing fixed on the exhaust pipeline extended up to

one meter above the roof of the vehicle, enabled the avoidance of this double

contamination through brake and exhaust emissions.

The aim of this paper is to

calculate emission factors for pollutants emitted by tyre and road abrasion,

the experiments followed the established and known procedure from the

literature. Indeed, an emission factor is applied for each vehicle category in the

fleet. In the case of the experiments, it was expressed as the number of

pollutants per kilometer (#/km), designating the number of pollutants emitted

by the vehicle over one-kilometer journey. It depended mainly on: the vehicle

type, its engine and technical features (carburation: petrol, diesel, LNG,

hybrid... and cubic capacity: small, medium, etc.), its date of entry into

service (which determines its age and therefore its wear), average vehicle

speed, track gradient, average traffic speed, and the proportion of the journey

made with a cold engine.

The vehicle used was an ASTRA CDTI

(year 2020) and had the following technical specifications: - Fuel type

(Diesel) - Engine displacement (1496 cm3 Inline 3) - Horsepower (120

HP) - Maximum torque (221 lb-ft) - Top Speed (210 km/h).

The proportion of the experimental

journey carried out with a cold engine was 2%. 84% of Lyon’s streets are

limited to 30 km/h, i.e., 610 kilometres out of 727. The rest of the streets

are limited to 50 km/h. Average speeds during the urban, suburban and motorway

tests were 40 km/h, 80 km/h and 125 km/h respectively. Data relating to the

city of Lyon (topography, slopes, and percentage of road slopes ...) are

described above and have been represented in

Figure 1.

2.2. Analysis of the Tyre-Road Surface Particles by SEM-EDX - Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the collected

particles from dust sampling in real driving condition on the carbon membranes

was carried out with the Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) associated with

Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX)

[74] for identifying the elemental composition of pollutants. SEM uses

an electron beam able to scan a focused stream of electrons over a given

surface to produce an image with a resolution less than 1 nm. Indeed, the

electrons interact with the atoms of the sample to analyse giving signals of

chemical composition of the collected pollutants. The combination of these two

techniques provided an identification of the pollutants elemental composition.

The data generated consisted of spectra showing the chemical elements

collected. Thus, energy of individual photons was measured to establish spectra

representing the energy-dependent distribution of X-rays. The X-photons were

captured by a solid-state detector, a lithium-doped silicon semiconductor,

cooled with liquid nitrogen. X-photons cause ionization in the semiconductor.

Free electron-hole pairs migrate under the effect of the polarization electric

field and cause current pulses whose height is proportional to the energy of

the photon. One can separate the impulses according to their height, and thus

count the photons incidents according to their energy. This method has a good

sensitivity in particular for photons with an energy between 0.2 and 20 keV.

The number of photons is assessed and the count rate is expressed in count per

second (cps). The main known limitation of this chemical analysis system is the

width of each peak of the spectrum. Indeed, the enlargement of a peak could

reflect the superposition of two or more chemical elements whose energy is close.

The greater the enlargement of the peak, the more difficult the possibility of

identifying a chemical element. For morphological analysis and the

microanalysis of the collected dust, the use of the JSM-6510LV (JEOL Ltd.) was

privileged as it is a high-performance SEM for a fast characterization of

chemical elements. The JSM-6510LV low vacuum scanning electron microscope

(SEM), with its high resolution of 3.0 nm at 30 kV, is a high-performance SEM

for the reliable identification of pollutants.

The JSM was coupled to an EDX

spectrometer (Oxford Aztec-DDI X MAXN 50, JEOL

[75]. SEM analyses were performed

at different magnifications and provided specific information on the

composition of the particles. The analyses of the particles gave a comparison

of their EDX spectra: retro-scattered electrons; intensity varying between 20

kV and 30kV (high resolution of 3.0 nm at 30 kV); working distance equal to

12mm (accelerating voltage from 500V to 30 kV); variation of pressure between

10 and 270 Pa; magnification x5 to 300,000 (printed as a 128mm x 96mm

micrograph); objective lens apertures: three position, controllable in X⁄Y

directions); maximum specimen size: 125 mm

∅ full

coverage; specimen stage: eucentric goniometer (X = 80 mm, Y = 40 mm, Z = 5-48

mm, R = 360° (endless), tilt -10⁄+90°), computer controlled 2, 3 or 5 axis

motor drive. The resolution is much higher compared to optical microscopes,

with a greater focal depth.

The fully automated INCA software

(ETAS Company) was used to analyse the collected particles. The surfaces

analysed for the pollutants chemical identification were all equivalent, and

were of the order of 24 mm2. INCA offered a wide variety of efficient and fast

functions to analyse data (flash programming, measurement data analysis,

calibration data management, and automated parameters optimization) [76]. The combined system used a

motorized turntable that enabled automatic analysis of 1,000 particles for each

sample. In addition to the INCA software, the application of the HCPC method

for the collected data provided structure of data in terms of a partition on

each granulometry interval, an identification of chemical elements, and

consequently gave a hierarchy structure of the sets of different identified

particles. This method was favoured over other simple classical methods that

exist in literature, such as Student’s t test, …. It is based on numerical data

classification methods [77,84] with a simplified application framework. Indeed, it is complete,

efficient and provides excellent quality results. This method allowed the

following analysis process:

- -

Original data - Extraction of particle size ranges

- -

Identification of intervals in order of importance

- -

Assignment of intervals to identified sets of different identified particles groups

- -

Homogenization of the sets according to their predominance. This step assumed, a priori, that the sets of the same identified particles were homogeneous

- -

Start of the calculations and then construction of the sets of particles

- -

Result with a hierarchy tree by granulometric intervals and by chemical element sets, having no consequences on relative loss of inertia of the used calculation algorithm

- -

The last processing step checks error propagation and providing means, Min, gravity centres, …

Data were processed with the R

software [78] which is

a free and open software environment for statistical computing. It compiles and

runs on a wide variety of platforms. It is a language of programming.

Processing of numerical data with R [79] followed the well-numerical known steps [80–82]:

- -

Import dataset in a new data matrix data

- -

Build this matrix of the scaled data and apply the Ward’s minimum variance method hierarchical clustering algorithm

- -

Identify and assess percentages of elements inside the same set. This step required the separation of experimental data on separate homogeneous sets of particles having equal variance that could minimize inertia in each set of data. This allowed the division of each set of data into three data sets (urban, suburban and highway), with the advantage of giving centroids of sets that measured how coherence was inside each set of identified particles

- -

Choose the number of sets of identified particles that seemed relevant based on data measurements

- -

Build the tree and interpret the obtained sets using the principal component analysis of FactoMineR package

- -

Interpret the partition of each set versus the obtained percentages of each chemical element

- -

Based on the previous steps, data analysis of results was grouped by type of route (urban – suburban – highway trips), granulometry interval and percentage of chemical elements which were identified.

Experiments in real-driving

conditions were carried out by the same driver and in the same atmospheric

conditions, allowing complete synthetic results without statistical bias,

confirming and appreciating the quality of homogenization step previously

announced. These analysis data exclude braking emissions: experiments were

carried out in such a way that the particles emitted by the brakes were not

recorded and did not impact whatsoever. In addition, metal wrenching and brakes

abrasion were not considered. Whenever braking occurred, the corresponding data

was systematically deleted. Particles were then classified in a family

according to their chemical composition and the result is given in the form of

a spectrum. As previously described, energy of individual photons is measured

to establish spectra representing the energy-dependent distribution of X-rays.

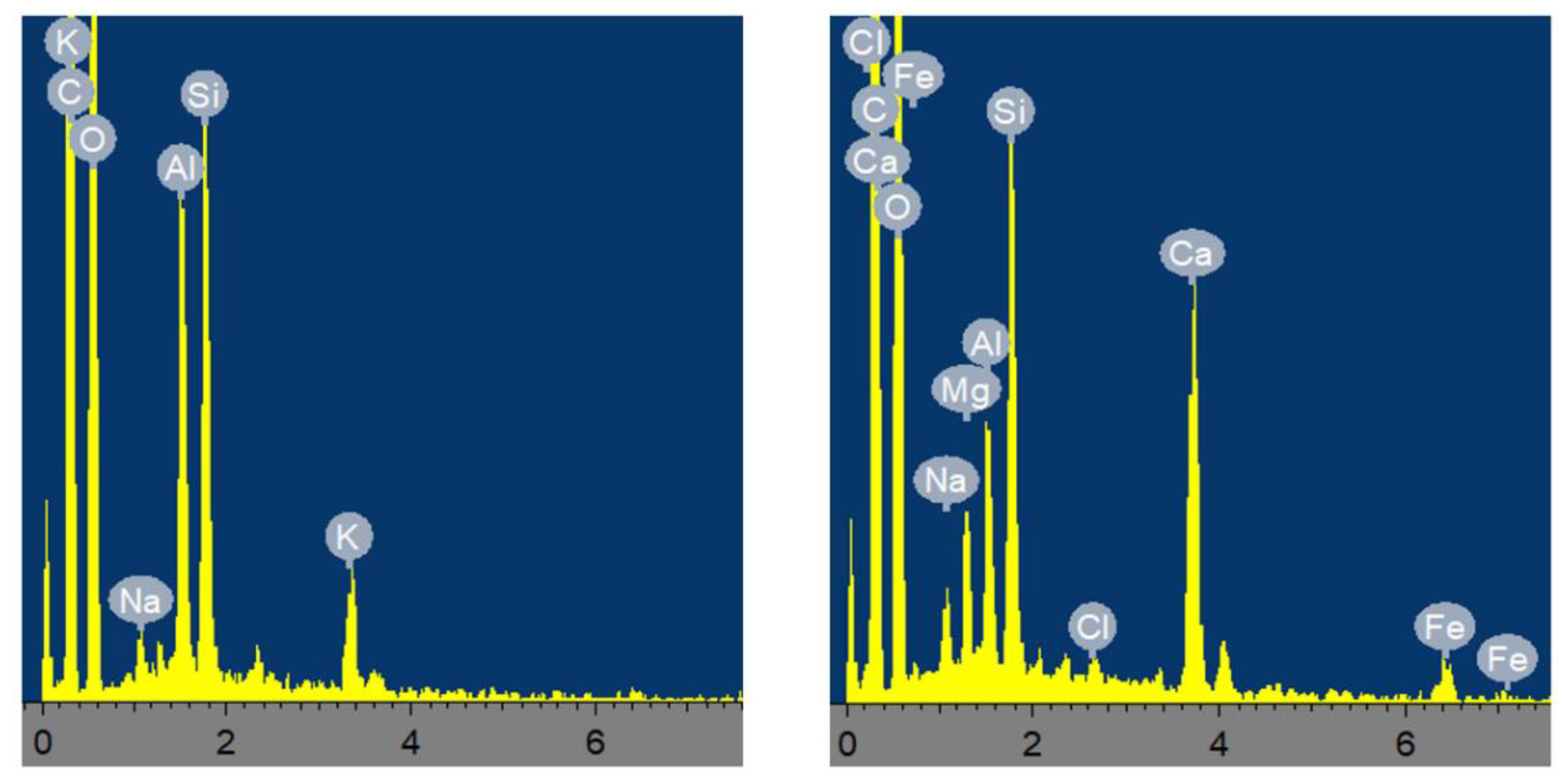

Two concrete examples of spectra

are given below (Figure 4). An elemental composition analysis was carried out using the SEM

EDX to obtain an X-ray emission spectrum for the particles. They show a

multitude of chemical elements identified with a net predominance of Si, Al,

Ca, Mg, Fe and their components.

Figure 4.

Example of two SEM-EDX spectra of particles (in Arbitrary Unit – Full scale 2054 cps).

Figure 4.

Example of two SEM-EDX spectra of particles (in Arbitrary Unit – Full scale 2054 cps).

In the spectra of the particles,

different peaks corresponding to C, O, Al, Si, Na, Al, Si, K, Fe, Ca, Mg, Na

and Cl and traces are present. This analysis was conducted spectrum by spectrum

to identify all the particles present on about a hundred sample membranes. The

different set of particles obtained during this analysis were: aluminosilicate,

iron and silicon compounds, iron and calcium oxides, calcium compounds,

silicate without aluminum, calcium phosphate, titanium and copper compounds,

chromium, sulphur and barium compounds, aluminum oxide, zirconium compound and

aluminum compounds, tungsten, …, and chemical traces. Multi-elemental particles

could be found in each set of compounds, with the identification of more than

33% of the total mass in the chemical element. If several elements had a mass

more than 3% in the same set of particles, the heaviest element was considered

and a new set of elements was created. Finally, statistical analysis of the

obtained and identified particle was carried out with the statistical software

R, in particular its FactoMineR package dedicated to multivariate data analysis [84].

This paper uses the identified

chemical elements by the SEM-EDX. Particles emitted from the exhaust,

resuspension and other contaminations, etc., were known, and systematically

eliminated. In fact, this work draws on much of the open literature that has already

provided information on the wide variety of pollutants considered to be

contaminants in this particular case. Larger particles are deposited on a

variety of substrates (buildings, infrastructures, roads, ...). Finer particles

can be deposited by Brownian agitation. When there is any topography of the

area in which particles are emitted, such as a street or neighbourhood, those

with a mass greater than the gas molecules do not follow the air flow which is

responsible for transport or dispersion phenomena. They continue moving in

their original direction in which they were originally emitted. The inertia of

particles allowed them to collide or stick to obstacles in the flow. The higher

the flow velocity, the greater the mass of the particles. In particular, this

phenomenon concerns particles with a diameter greater than 1 µm. For example,

this inertia is commonly used to separate particles according to their size in

cascade impactors or cyclones [2,6,8]. Inertia of chemical species has been used to analyse the

homogeneity of the flow. Chemical species ‘i’ were assessed in all the measured

samples. Calculating the v_test meant applying the following formula [84] for species ‘i’ (i ∈ groups) to verify the

homogeneity degree of flow of particles. These sets consist of chemical

elements with the same properties or the same chemical identification obtained

by a count:

where:

- i: chemical specie (pollutant)

: frequency of the ‘i’ specie in

the set I

: frequency of the ‘i’ specie in

the all sets of data

: the relative number of ‘i’

specie in the set I versus the size

: the relative number of ‘i’

specie in all the sets of data I versus the total size of the sets

I is the set of identical chemical

species, identified by SEM-EDX, analysed for a given surface of the sampling

membrane. This surface may correspond to the total surface of the membrane if

the analysis is performed on a single membrane. In this particular case, the

MEB analysis surface was defined for all the particle collection membranes

v_test is well-known to be

sensitive to the identification sensitivity analysis. It is used in this paper

to categorial variables “i” in terms of chemical identification. This is a

necessary and sufficient condition when sets of species are different.

3. Results

Individual particle analyses

SEM-EDX and global analysis (granulometry - particle size) were performed, as

well as the calculation of the overall values for the data obtained at the

SEM-EDX, this in order to make comparisons. Thus,

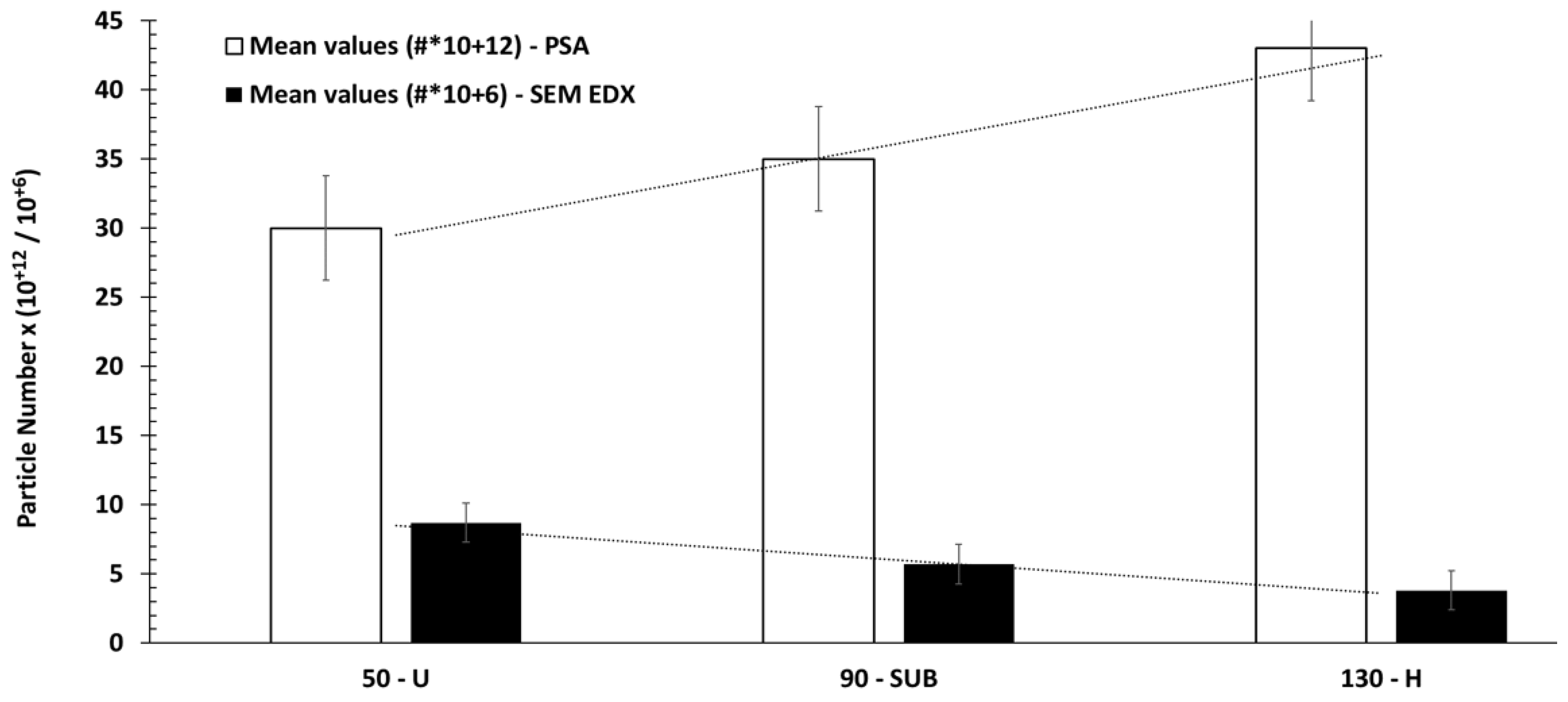

Figure 5 presents the

variations of the mean values of the particle number according to the analysis

by the SEM-EDX of the collected particles on the membranes, and by the particle

size analyser (PSA) vs. the vehicle speed. This analysis was conducted for the

three types of trips: 6 urban trips, 2 sub-urban trips and 3 highway trips. The

respective speed values for the three routes in France (45 km/h, 90 km/h and

130 km/h) represent the maximum values to be performed per site.

Figure 5.

Number of particles depending on the type of analysis (PSA and SEM-EDX) and road (urban, suburban and motorway respectively with speed limit of 45 km/h, 90 km/h, 130 km/h).

Figure 5.

Number of particles depending on the type of analysis (PSA and SEM-EDX) and road (urban, suburban and motorway respectively with speed limit of 45 km/h, 90 km/h, 130 km/h).

First of all, we can see that

there is an effect of the vehicle speed. The number of particles emitted

increases with the speed when measurements are made with a particle size

analyser. A slight inverse effect occurred when analysis was performed with the

SEM-EDX. This behaviour in the number evolution is normal and is due to the

fact that a chosen surface was targeted for EDX SEM analysis. The measured

average particle number values are:

- -

Particle size analyser: (30, 35, 43) 10+12 particles.

- -

SEM-EDX: (8.7, 5.7, 3.8) 10+6 particles.

The ratios (particle size count/

SEM-EDX count) are respectively of 6.4 10+6, 6.2 10+6 and

11.3 10+6 for urban, suburban and highway trips.

The following analysis will make

it possible to extrapolate this number of particles for the surrounding

particles collected throughout the membrane.

Several observations can be noted:

A high factor of more that 10+6 is found between the particle size values and the assessment of the total number of particles from the SEM-EDX results. This seems natural because the collection on the membranes is purely qualitative and serves more for chemical identification.

Despite uncertainties in both particle size count, there is an inversion of the curves between particle size and chemical particle counting as a function of velocity. On the one hand, considering SEM-EDX counting, more particles were collected in the urban area than on highways because of the vehicle speed. This is certainly due to the dynamics of emissions as a function. On the other hand, the inversion of this curve, obtained by the particles collected by granulometry method, seems in favour of the speed. The faster we drive, the more we collect. This Figure confirms that the physico-chemistry is preserved with this double collection independently of the variations that can be observed. Therefore, precaution must be taken when counting particles from the collection on membranes for chemical analyses. In this case, the emission dynamics, which is a function of the speed of the vehicle, could not be confirmed.

In conclusion, counting from the

SEM-EDX is a qualitative count in favour of the chemical identification of

emitted particles. On the other hand, particle size counting is quantitative.

Based on the collection of particle size data, the analysis of the most

emissive particle size intervals is shown in the following Table 2 in order of importance

in terms of emission:

Table 2.

Predominance order of the collected particle sizes (U, SUB, H).

Table 2.

Predominance order of the collected particle sizes (U, SUB, H).

Predominance order

of particle sizes |

U |

SUB |

H |

| 1st class |

<1µm |

<1µm |

<1µm |

| 2nd class |

1-2µm |

1-2µm |

1-2µm |

| 3rd class |

- |

2-3µm |

2-3µm |

| 4th class |

- |

- |

3-4µm |

We can observe in this table that

the grain size range widens from the urban to the motorway emissions. The

particles less than 1 µm are the most present in the three road routes;

followed by interval [1 µm, 2 µm], and finally [2 µm, 3 µm] for the sub and [3

µm, 4 µm] for highway. The synthesis thus provides a general predominance of

particles emitted in the particle size range respectively [<1 µm, 2 µm],

[<1 µm, 3 µm] and [<1 µm, 4 µm] for urban, suburban and highway

experiments.

The percentages of the predominant

particle size classes are 72.7% for the first two combined classes, 21% for the

third and 6.3% for the fourth. The effect of the speed of the vehicle, and

therefore the potential for collecting particles online, is certainly obvious.

These percentages are therefore consistent with what was observed in the

literature [6,17,27,85–87]. The first two particle size classes are known to have the highest

degree of toxicity [88] because they easily penetrate the lungs and cross biological

barriers to be located in vital organs, may cause significant health

consequences.

Number concentrations are

therefore dominated by particles <1μm, while most of the mass was in

particles >1μm. This result agrees with the work of Alves et al. [89]. These authors had found

rather 0.5μm instead of 1μm, which is not really in contradiction with this

result if it is refined further, thus it would not be necessary because it does

not improve the results.

Particle larger sizes were not

collected because they were deposited on the road surface. This finding

completes the obtained results by Iijima et al. [90] in terms of size distribution

(1–10μm and 2–3μm). The results indicated in this article confirm the analysis

made by Liu et al. 54] who identified the variations in particle size range, in particular

in 0,25-4μm interval. In addition, Harrison et al. [41] confirmed in their analysis of

the non-exhaust emissions, i.e., from the brakes abrasion, tyres and wear of

the road surface, as well as from resuspension of road dusts, that the emitted

particles have to be in both the coarse (PM2.5-10) and fine (PM2.5) fractions, with a larger proportion in

the former. The results of the experiments agree with those obtained in the

open literature, in particular with Beji et al. [12], Harrison et al. [41], Liu et al. [54], Piscitello et al. [86] and Zhang et al. [87,91].

Concerning the chemical analysis,

data processing shows a wide variety of chemical elements emitted in real

driving situations. During chemical analysis, the systematic presence of carbon

and oxygen was noticed in all analysed tabs (membranes). This is found in

almost all SEM-EDX analyses reported in the open literature [6,27,40].

In order to identify the

tyres-road surface particles, carbon and oxygen C and O were excluded from the

statistical analysis. In this paper, neither the production modes of particles

nor their shapes were analysed because this would require a very complex

additional experimental work. Individual analysis is very expensive in terms of

computational time. These modes and shapes that could be subject to further

works are: 1. Nucleation mode (particles having a spherical shape with ϕ <

30 nm). 2. Accumulation (particles having an angular morphology with 100 nm

< ϕ < 200 nm). 3. Coarse mode (particles aggregated with 1 µm < ϕ).

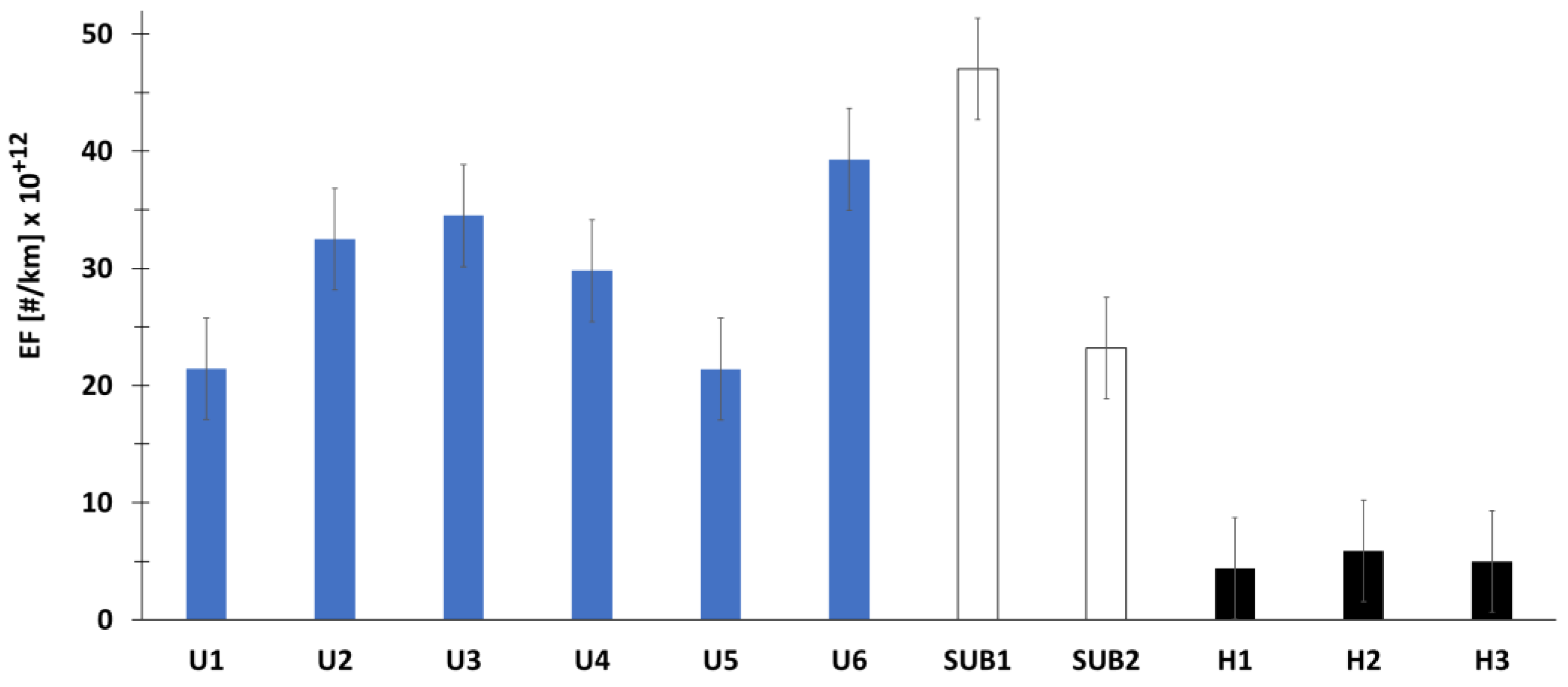

Analysing the particle number

collected by analyser allowed to calculate the emission factor for four

different situations: 1. on an urban site where the traffic speed is between 30

and 50 km/h; 2. on a suburban site where the speed limit is 90 km/h; 3. on a

highway where the speed limit is 130 km/h; 4. in a traffic zone on an urban

site in the city of Lyon (France). Granulometric data was collected with ATMO

AURA fixed systems. Among the data collected, the following selection was made:

6 urban routes (U1 to U6), 2 suburbans (SUB1 and SUB2) and three highways (H1

to H3). For comparison, the collection then analyses focus on a series of data

recorded during 4 different days corresponding to a static urban traffic site

(S1 toS4). The data were collected during days when the weather conditions were

identical to the whole other experiments (U, SUB, H).

Figure 6 below shows emission factors EF in number of particles per km

travelled (#/km).

Figure 6.

Emission factors for three different driving situations. Maximum authorized speed [Urban ‘U’ (50 km/h) – Suburban ‘SUB’ (90 km/h) – Highway ‘H’ (130 km/h)].

Figure 6.

Emission factors for three different driving situations. Maximum authorized speed [Urban ‘U’ (50 km/h) – Suburban ‘SUB’ (90 km/h) – Highway ‘H’ (130 km/h)].

The emission factors are of the

order of 30 10+12 #/km and 35 10+12 #/km for urban and

sub-urban respectively. We observe that there is a difference between urban and

peri-urban of 5 10+12 #/km. However, on highway, the emission

factor, on average in the order of 5 10+12 #/km, is much lower than

the two previous situations. Emission factor obtained on the highway trip is of

the same order of the magnitude as the difference between urban routes and

suburban driving situations. The number of particles was calculated for a

duration equal to the duration of urban experiments U1 to U6. Finally, for the

urban traffic situation site, we have on average a number equal to 43 10+12

#/cm3 (S). This value (number of particles per unit volume) cannot

be related to an emission factor obtained in real driving conditions. However,

this higher value, in static urban site, can be considered quite high. This is

due to the accumulation of pollutants in a fixed urban site, corresponding to

the ambient air pollution in this urban point location.

The obtained EF for the three

types of experiments are above the value of the euro 6 standard (fixed at 6 10+11

#/km) for both diesel and petrol vehicles. It can also be noted that these EFs

are below of the values corresponding to diesel vehicles not equipped with

particle filter (6 10+13 #/km) where ratios are of 2 (U), 1.7 (SUB),

12 (H) and 1.4 (S). As a reminder, the New European Driving Cycle gave a limit

value of 6 10+11 #/km (Euro 6b) for PN (number of particles per km)

for spark-ignition engines (gasoline, LPG, etc.), including hybrids, and a

limit value of 6 10+12 #/km for diesel engines only, including

hybrids. In the future, we shall be seeing stricter regulations on the limit

values that must not be exceeded.

It can be noted that the number of

particles is quite similar in the city static situation compared to experiments

performed in real driving conditions. This is due both to the dispersion of

pollutants but also to the effect of accumulation in a localized static point.

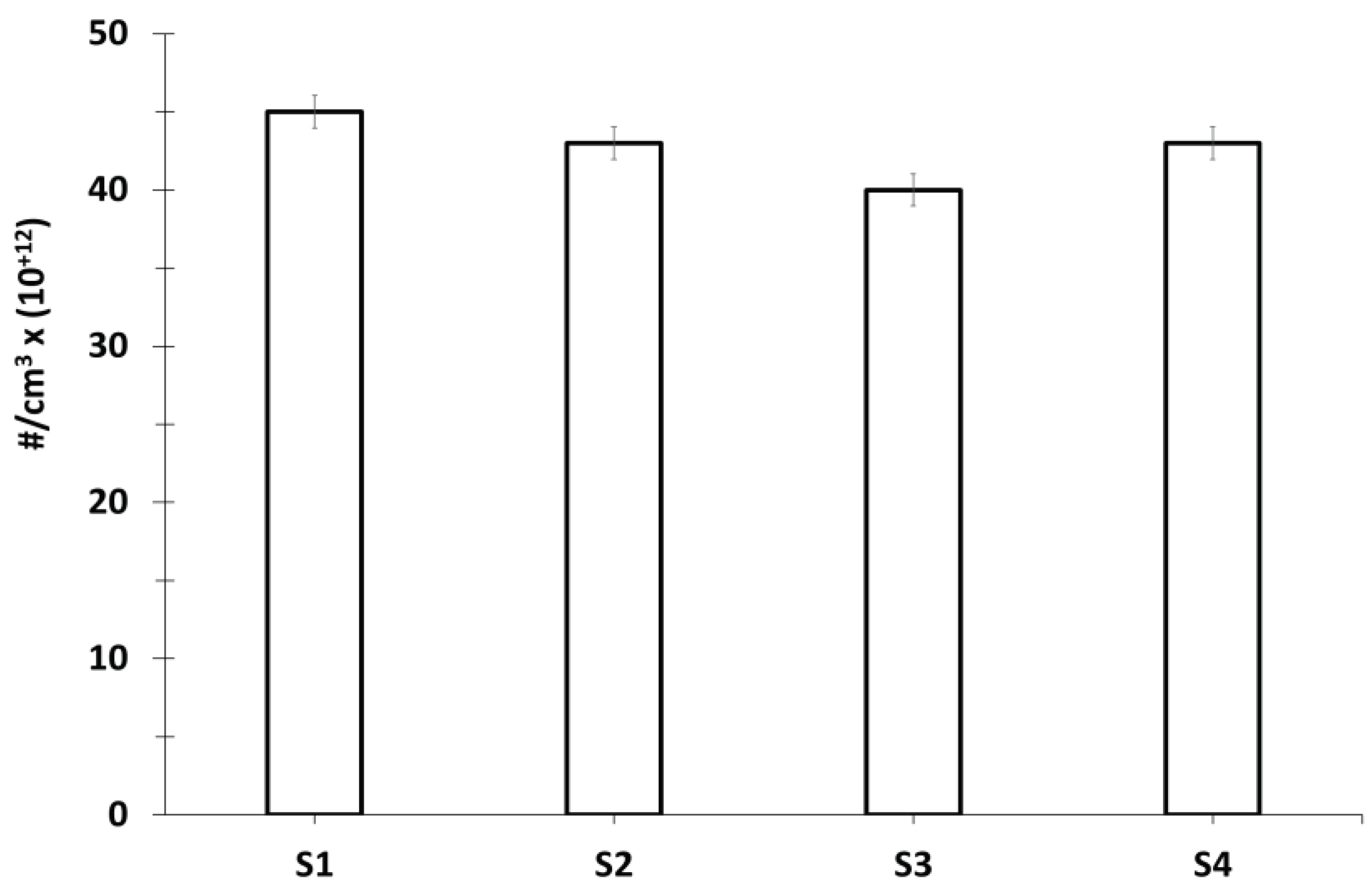

Figure 7 shows the number of

particles per cm3 at this static point in the urban area of Lyon.

For all the performed experimental measurements, with uncertainties, the number

of particles per cm3 is greater in static situation in city (≈ 42.8

10+12 #/cm3) than in real driving situation

(approximately 30 10+12 #/cm3 in urban and 35,1 10+12

#/cm3 in suburban). This is due both to the dispersion of pollutants

but also to the effect of accumulation in a localized unpoint.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of the average number of particles per cm3 in the traffic site, at a fixed location in an urban environment (S1 – S2 – S3 – S4).

Figure 7.

Evaluation of the average number of particles per cm3 in the traffic site, at a fixed location in an urban environment (S1 – S2 – S3 – S4).

These results allowed to evaluate

the average corrective factor ACF between analysis of emission factors obtained

by particle size analysis and those obtained by identification using the MED

EDX. These average factors are respectively 3,4 10+6 (urban), 6,1 10+6

(suburban) and 11,3 10+6 (highway).

Thus, the number of particles used

in the chemical identification of pollutants, obtained by the SEM-EDX analysis,

is multiplied by this corrective factor to obtain the number of particles that

would be analysed online in real driving situation. This analysis enabled to

establish the emission factors by chemical element, as presented in the

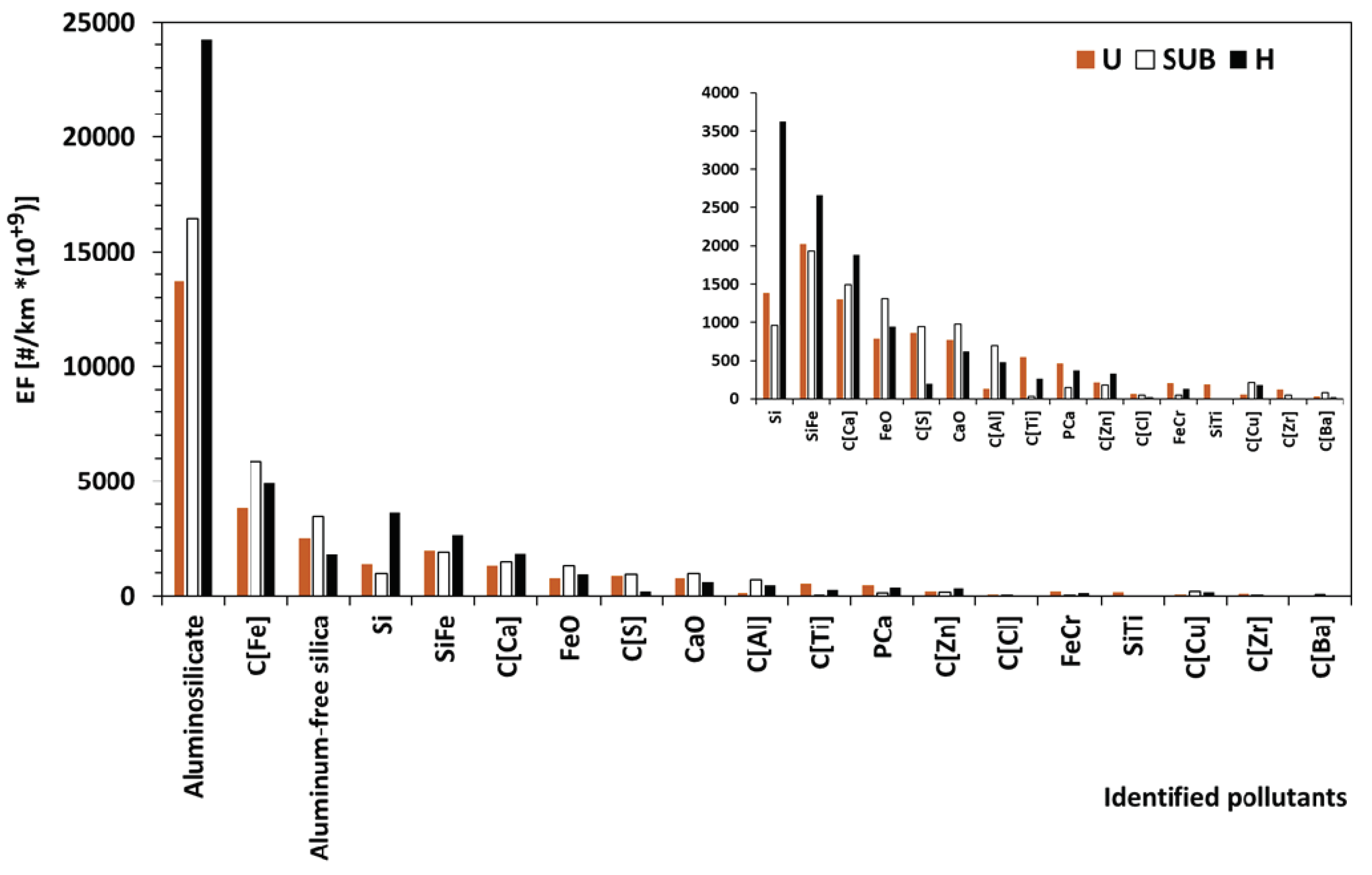

Figure 8 which shows the

average emission factors EF for the 19 identified pollutants.

Figure 8.

Emission Factors for the identified individual pollutants in real driving.

Figure 8.

Emission Factors for the identified individual pollutants in real driving.

We note the predominance of

aluminosilicate, Fe components, aluminum free of silica, Si, SIFe, Ca

components, and FeO. For the rest of the pollutants, the A_EFs are low. This

does not mean that they should not be taken-into-account in any environmental or

health impact analysis, as this will naturally depend on the volume of the

vehicle fleet.

Table 3 gives the emission factors for 19 pollutants identified using the

SEM EDX technique. These are emission factors obtained experimentally in the

region closest to their emission sources (tyres - road surface). Analysis of

pollutants taken individually, EF ranges from 0.003 to 18.142 10+12

#/km.

Table 3.

Emission factor for 19 individual pollutants.

Table 3.

Emission factor for 19 individual pollutants.

Identified pollutants

by SEM-EDX |

Emission Factor

[#/km *10+9] |

Percentages (compared to the total number) |

| 1 |

Aluminosilicate |

18142±597 |

50,9% |

| 2 |

C[Fe] |

4881±175 |

13,7% |

| 3 |

Aluminum

-free silica |

2612±57 |

7,3% |

| 4 |

SiFe |

2206±60 |

6,2% |

| 5 |

Si |

1989±36 |

5,6% |

| 6 |

C[Ca] |

1558±32 |

4,4% |

| 7 |

FeO |

1013±33 |

2,8% |

| 8 |

CaO |

789±26 |

2,2% |

| 9 |

C[S] |

667±25 |

1,9% |

| 10 |

C[Al] |

436±27 |

1,2% |

| 11 |

PCa |

329±17 |

0,9% |

| 12 |

C[Ti] |

281±11 |

0,8% |

| 13 |

C[Zn] |

240±8 |

0,7% |

| 14 |

C[Cu] |

152±5 |

0,4% |

| 15 |

FeCr |

129±9 |

0,4% |

| 16 |

SiTi |

64±7 |

0,2% |

| 17 |

C[Zr] |

58±9 |

0,2% |

| 18 |

C[Ba] |

46±11 |

0,1% |

| 19 |

C[Cl] |

39±11 |

0,1% |

By way of comparison, the euro 6 standard is set at 6 10+11 #/km for both diesel and gasoline. For diesel vehicles not fitted with a filter, the given value is 6 10+13.

Experiments do not take into-account a heterogeneous mixture of components from (P, Cl, Fe, Ba, Cr, Zr) which represents a percentage of less than 0.1% of the total number of particles identified.

Pearson and Spearman correlations [92] applied to the data according to the different variables (urban, suburban and highway routes, the same vehicle equipped with the same tyres, the weight of the vehicle, nature of the road, …), showed that correlations were significant (with p< 0.02).

In addition, analysis of the inertia of chemical species ‘i’ has been carried out to confirm the homogeneity of their identification. Assessment of v_test was also done especially for the comparison between identified pollutants and their numbers. Characterization of each pollutant and the significance test was calculated:

v_test is equal to 1.92 for urban sets of data of pollutants, 1.97 for suburban, and -1.87 for highway (p ≌ 5%). The inertia of chemical species, in the three trips, is definitively homogeneous, and analysis is therefore considered significant (v_test ≌ ±2).

It should be remembered that this finding completes and provides additional information to the work by Dahl et al. [37], Panko et al. [85], Piscitello et al. [86], Iijima et al. [90], Zhang et al. [92] and Kaul and Sharma [93]. Piscitello et al. [86] had confirmed that the emission rate of the non-exhaust pollutants reached 90% by mass of total traffic-related PM emitted. They gave emission factors as follows: 0.3 mg/km to 7.4 mg/km for tire wear; resuspended dust: 5.4 mg/km to 330 mg/km.

Finally, an attempt was made to approximate the EF of the PM10 and PM2.5 from the calculations by Zhang et al. [91]. Indeed, by assessing the density of those two major air pollution determinants, with a conversion of the number into mass and assuming that all the particles are identical and spherical, the obtained FE is of 1.45 mg/km for PM10 and 0.35 mg/km for PM2.5. These FE values are close to those obtained by Zhang et al. [91] (0.21 mg/km for PM2.5 and 1.27 mg/km for PM10), who carried out experiments on a tyre dynamometer. The small difference can be attributed to the fact that this new additional work assesses all the emissions from the tyre-road surface wear and not the emissions from the tyre alone.

This shows that the new methodological approach used in this paper is particularly effective in assessing pollutant emission factors. It is a new alternative to existing methods that are sometimes very difficult and costly to implement. In addition, Alves et al. [89] had generated wear particles on a road simulator to study the interactions between tyres and a composite road surface. They found that the emission factor due to wear between their particular road surface and the tyres was of the order of 2 mg/km. On the one hand, work carried out on any simulator under controlled conditions often deviates from reality or from actual vehicle use. On the other hand, this estimate is not very far removed from the new results being produced and obtained with experiments carried out in real driving situations.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents an original experimental approach combining collection of particles emissions induced by the tyres-road surface wear in real driving conditions, in urban, suburban and highway routes. Comparatively, the data was collected on a site located in the city, on a boulevard where traffic is very important. To determine the chemical compositions and then emission factors of particles emitted by tyre-road surface wear without contamination from brake dust, measurements were performed in real driving conditions. The SEM-EDX has been used to identify the measured chemical elements and their nature. Predominant particles emitted by tyres-road surface have been analysed and emission factors for 19 identified pollutants assessed for the first time using this new approach. The major findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

1. The mainly most measured tyres-road surface particles were smaller than 1 µm for the three road routes; followed by interval size particles [1 µm, 2 µm]. Then, in the third position we have the size range [2 µm, 3 µm] for suburban and highway; and in the fourth position the range [3 µm, 4 µm] for highway alone. It should be noted that particles of sizes between 2 and 4 µm are emitted in urban, between 3 to 4 µm in suburban experiments but at low proportions due to emissions dynamics (vehicle-tire-pavement) related to the movement of the vehicle and the tribology of the materials that constitute the tyres and the road surface.

2. Data processing showed a wide variety of chemical elements emitted in real driving situations. The systematic presence of carbon and oxygen was noticed.

3. Emission factors EF were calculated on the basis of granulometric and global chemical analysis of the measured date: average values for all measured pollutants are 30 10+12 #/km and 35 10+12 #/km respectively for urban and sub-urban. However, on highway, EF is equal to 5 10+12 #/km, about 6 to 7 times lower than the previous two. Analysis for pollutants taken individually, the EF ranges from 0.003 to 18.142 10+12#/km. Significance test analysis was carried-out for the identified pollutant and their EF. v_test is found to be varied between 1.87 and 1.97 (p ≌ 5%). The inertia of chemical pollutants is definitively homogeneous, and analysis is therefore considered significant because the v_test is ≌ ±2.

4. The obtained EF are above the value of the euro 6 standard of 6 10+11 #/km for both diesel and petrol vehicles. EFs are below the values corresponding to diesel vehicles not equipped with particulate filter (6 10+13#/km). As a reminder, the New European Driving Cycle gave a limit value of 6 10+11#/km (Euro 6b) for PN (number of particles per km) for spark-ignition engines (gasoline, LPG, etc.), including hybrids, and a limit value of 6 10+12 #/km for diesel engines only, including hybrids.

5. Assessment of EF of the PM10 and PM2.5 emitted by the tyre-road surface wear are 1.45 mg/km and 0.35 mg/km, respectively.

6. The number of particles number per volume element in static situation in the city is ≈ 42.8 10+12 #/cm3. This number of particles is stable almost every day except for summer holiday periods and Sundays when urban traffic is low in the city. In real driving situation, we obtained 30 10+12 #/cm3 in urban and 35 10+12 #/cm3 in suburban. The larger measured number on the fixed site is due both to the dispersion of pollutants and also to the effect of accumulation in a localized unpoint.

These results show that the methodological approach, used in this paper, is particularly effective in assessing pollutant emission factors. This kind of approach is a new alternative to existing methods. The significant obtained results in this paper thus provide reliable information to help improve emission models, making them more accurate and applicable. Further research, integrating the phenomena of resuspension of particles in the air, is necessary. These researchers will bring other scientific knowledge to the work presented in this paper. They will have to consider the nature of the materials of the road surfaces and tyres. Their physico-chemical characteristics must therefore be specified. Thus, a metrological and methodological development must be carried-out to separate the sources of particles emitted by the tyres, the road surface and the resuspension. These particles will have to be analysed individually, and if possible online to avoid chemical transformations that induce secondary pollution because airborne particles can differ significantly from friction materials. Then, experimental conditions will have to be controlled, and if necessary supported by new tool developments. The problem could become insoluble if we were not to take into-account the “complex” mixing effect between exhaust and non-exhaust emissions.

The results presented in this paper will contribute to future regulations for road vehicles (thermal, hybrid, electric, autonomous). Further scientific work, i.e., analysing exposure-impact relationships to particles emitted by abrasion of tyres and road surface, is needed to complete the development of technical and legislative recommendations, as well as health guidelines. Appropriate regulations will provide the framework for public and environmental policies. They will also provide the necessary support for emerging technologies which objectives are the well-being of population and improvement of the environment.