1. Introduction

Pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF) refer to a form of therapy that utilizes electromagnetic fields to promote various physiological effects within the human body. These fields consist of time-varying electromagnetic waves with specific frequencies, amplitudes, and pulse durations. PEMF therapy has gained significant attention in recent years due to its potential benefits in managing pain, promoting tissue repair, and improving overall well-being [

1].

PEMF therapy operates on the principle that electromagnetic fields can interact with biological systems at a cellular level. The pulsating electromagnetic waves can penetrate tissues and reach deep within the body, interacting with cells, tissues, and organs. This interaction can influence cellular behavior, modulate biochemical processes, and trigger a range of beneficial effects [

2].

Research on PEMF therapy has explored its potential in diverse medical fields, including orthopedics, neurology, and wound healing. Some studies have suggested that PEMF therapy may help in reducing pain and inflammation, accelerating bone healing, enhancing nerve regeneration, and improving circulation [

3,

4,

5]. Additionally, a promising effect has been shown in managing conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and depression [

6].

While the exact mechanisms through which PEMF therapy exerts its effects are still unclear, several hypotheses have been proposed. It is believed that PEMF therapy can stimulate the production of various molecules and signaling pathways involved in tissue repair, such as growth factors, nitric oxide, and cytokines [

7,

8,

9]. Additionally, PEMF may modulate cellular membrane potentials, ion transport, and calcium signaling, all of which play crucial roles in cellular function [

1].

Despite a lot of research and several uses for medical purposes, until now very few studies investigated the influence of PEMF stimulation during sport or physical activity. Kim et al [

10] investigated the influence of 12 weeks of PEMF therapy on plasma Nitric Oxide (NO) in 23 subjects with mild to moderate metabolic syndrome. The authors showed that 16-min of stimulation, three times/day, were able to increase circulating plasma NO levels at rest and at the end of submaximal exercise performed at moderate intensity. The observed improvement in blood flow following PEMF treatment was likely mediated through calcium Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent NO cascades. The potential mechanism is that PEMF enhances the binding of Ca2+ and calmodulin and then Ca2+CaM binds to e-NOS to release NO [

11]. Therefore, PEMF may increase NO synthesis activity [

12] and consequently enhance NO-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) cascades resulting in vasodilation [

13].

Tamulevicius et al. [

14] investigated the effect of acute PEMF treatment on aerobic performance in 14 male cross-country runners of the 2nd division of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). The authors applied 8-minutes of low frequency PEMF stimulation before and after each of the 6-training session for a total of 12 times. Results showed that acute PEMF therapy did not induce significant changes in almost all aerobic performance parameters, as absolute or relative VO2peak, ventilation or maximum respiration rate. However, stimulation induced significant variation in time for relative ventilatory threshold (VT), suggesting possible application of PEMF during short-term training, in order to elevate VT.

Trofè et al. [

15] investigated the effect of PEMF stimulation in semi-professional cyclists. The authors found that stimulation applied during a heavy constant-load exercise was able to enhanced the rate of muscle oxygen extraction and utilization. Stimulation increased the velocity and the quantity of muscle O2 available, accelerating the HHb kinetics, without affecting the pulmonary VO2 on-transition kinetics.

It has been hypothesized that PEMF affected energetic metabolism, especially glycolytic metabolism of type-II muscular fibers [

16]. Indeed, PEMF stimulation increased the blood lactate level during exercise [

15], suggesting a possible influence of stimulation on muscle activity and on the glycolytic metabolism of type-II muscular fibers. This effect could be caused by the change of membrane permeability [

17] and Ca2+ channel conduction [

18], enhancing ion flux and cellular concentrations [

19,

20] that improve contraction mechanisms during exercise. A recent study showed that PEMF could affect glucose utilization. Indeed, in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetic muscle atrophy, PEMF treatment affected metabolic enzymes in the quadriceps, with increased succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and malate dehydrogenase activity (MDH), suggesting an increase in the metabolic capacity of muscle [

21]. In insulinoma cells, PEMF exposure attenuated insulin secretion, suggesting effects on calcium channels and ions flux [

16]. Regarding exercise, a crucial role is played by the mechanism of muscular contraction, which are affected by Ca2+ channels and ions flux. PEMF stimulation affects calcium channels raising Ca2+ intracellular concentration [

19,

20], amplifying signal Ca2+ mediators and Ca-dependent pathways [

22]. Changes in membrane permeability [

17] and ion channel conduction [

18] might be possible mechanisms on how pulsed electromagnetic field affects biological systems. Further, it has been hypothesized an influence on phospholipids of plasma membrane that improves production of second messengers, with starting cascade of multiple intracellular signal transduction [

23,

24,

25]. Considering all these premises, the investigation of PEMF effects during exercise, and more precisely, assessing its influence on muscles activity becomes newsworthy. We hypothesize that PEMF stimulation could improve muscle response following its implication on the mechanisms involved in muscular contraction. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of PEMF in young sedentary people during a constant-load exercise performed at moderate intensity.

2. Materials and Methods

The study design was a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Nine male sedentary young people participated at this study (

Table 1). Based on the effect size evident in Trofè et al. [

15,

26] G∗power software, version 3.1.9.2 (Kiel, Germany), predicted that a total sample size of 8 would give sufficient power (0.80) to detect a significant difference at alpha level of 0.05. One additional participant was included to ensure the availability of data in case of missing or corrupted data. All participants were volunteers, healthy, non-smokers and none of them were taking medications or supplements. None of the participants reported physical deficit or muscular injury at the time of the study. They received a verbal explanation of experimental procedures, and informed consent was obtained before the beginning of recordings.

2.1. Procedure

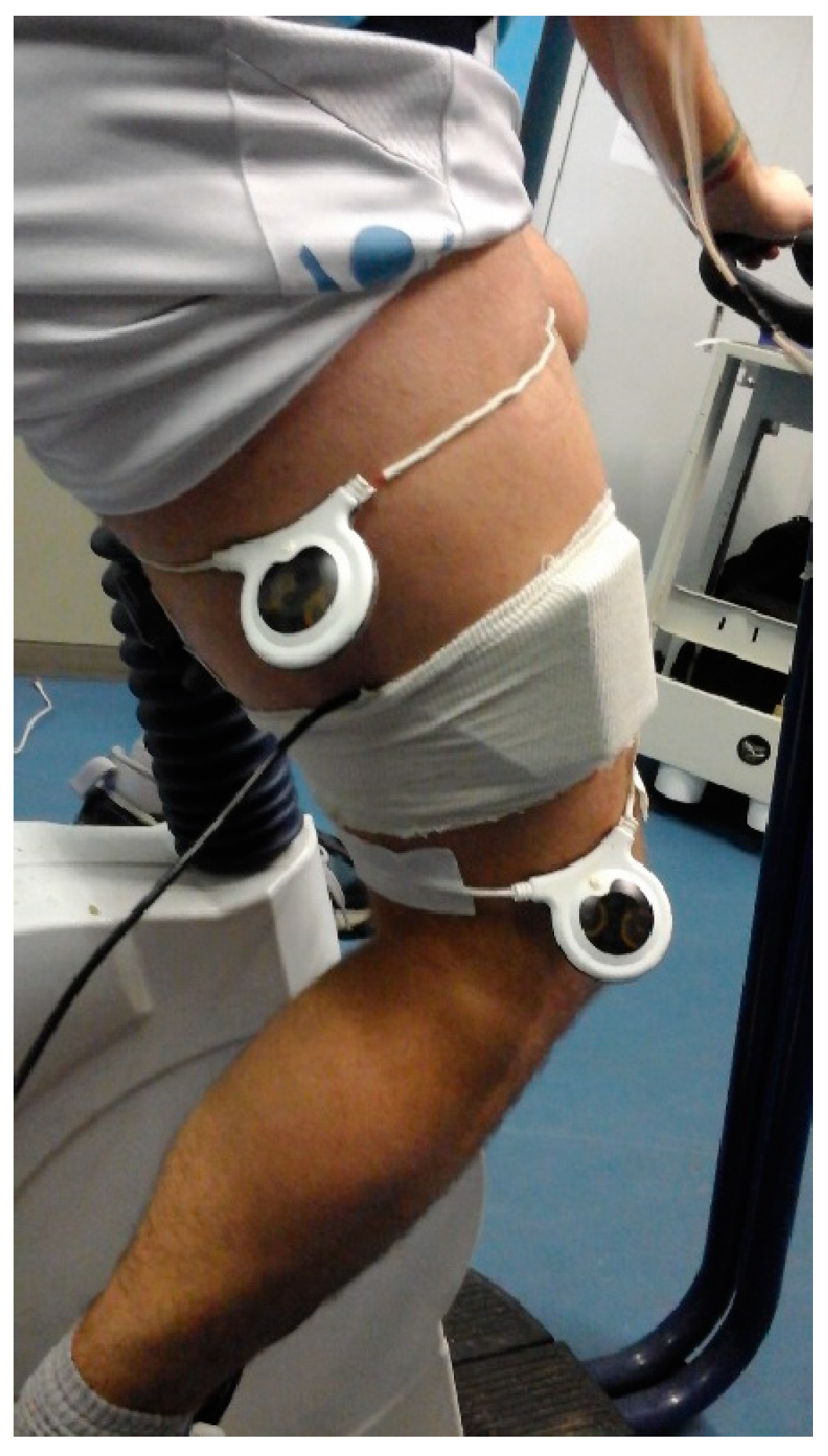

The experiments were performed on the cycle-ergometer (H-300-R Lode, Exere Air Machine, Italy), under a standardized procedure, in a quiet room with a stable and comfortable temperature (22°C), at the same time of the day (9:00-12:00 AM) to avoid circadian influence. Participants were asked to avoid drinking caffeinated beverages before the experimental procedures and were instructed to avoid strenuous activity and alcohol in the 12h preceding the test. We recorded EMG activity from the Vastus Medialis and Biceps Femoris caput longum of the right leg. EMG data were recorder at a sampling rate of 250 Hz by a Free-EMG 1000 (BTS Bioengineering, Inc.). In order to stimulate the entire thigh, two circular 20 cm PEMF loop-antenna devices (Torino II, Rio Grande Neurosciences, USA) were positioned at the beginning and at the end of the right thigh, as showed in

Figure 1.

Participants came to our laboratory five times, with an interval of three days between each visit. In each of these visits we performed several recordings. In the first day, we recorded maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) and an incremental test until exhaustion to find their individual maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) (see

Table 1). In order to record MVC, each participant performed, for 5 seconds, an isometric contraction against a maximum load using isotonic machines (Exere Air Machine, Italy). They repeated the same procedure 3 times, separated by 2 minutes of rest, and we used the maximum MCV peak value of each investigated muscle to normalize electromyographic data, procedure already used in previous studies [

27]. Participants performed an incremental test on a cycle-ergometer (H-300-R Lode), to determine the peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) to identify their individual workload for the succeeding four recording sessions. Expirated gases were analyzed using a Quark b2 breath-by-breath metabolic system (Cosmed, Rome, Italy) [

28].

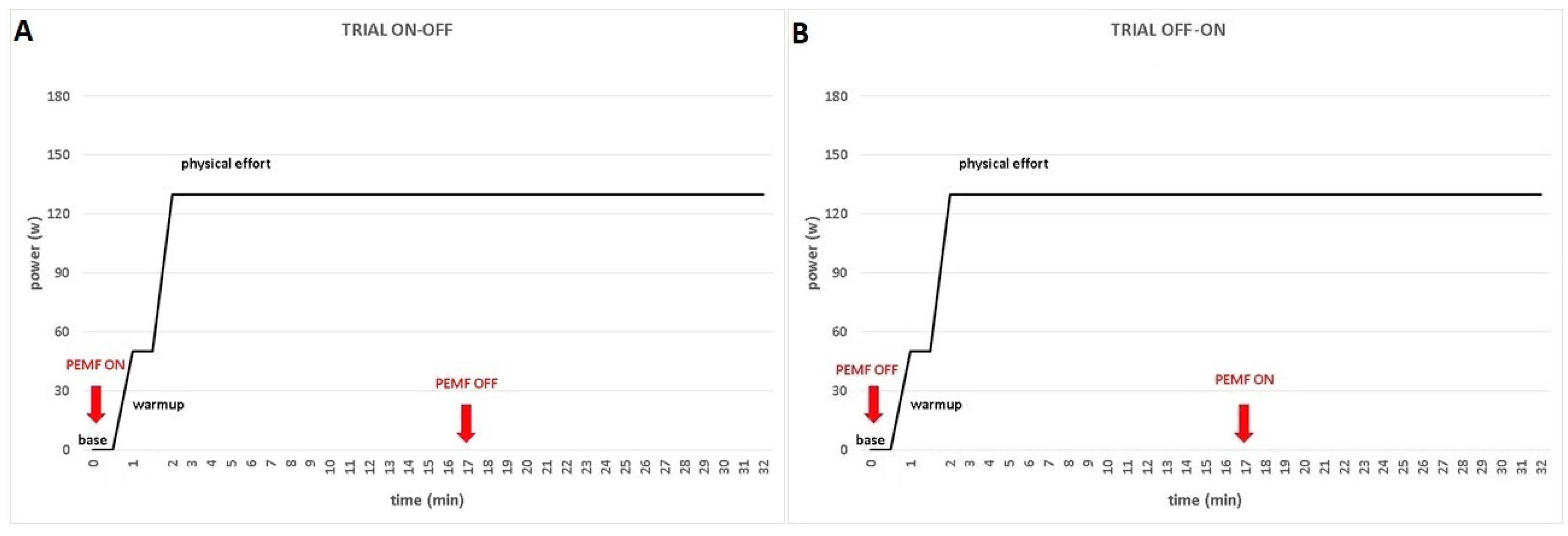

From the day two to the day four, participants come to our laboratory for the exercise sessions. The experimental conditions were PEMF ON and PEMF OFF, in which the PEMF was turned on and off, respectively in the same exercise. When the trial started with the PEMF in ON modality, the device was turned off after 17 minutes and the participant keep going cycling until the end of the trial. Otherwise, when the trial started with the PEMF in OFF modality, the device was turned on after 17 minutes and the participant keep going cycling until the end of the trial (

Figure 2).

The two PEMF loops were positioned on the right leg (

Figure 1) in both experimental conditions because the stimulation was not perceived by the participants at the cutaneous level (single blind trial).

The recording session started with participants standing for 1-minute sitting on cycle-ergometer with extended right leg in order to recorded baseline values. Then, the warm-up involved an unloaded cycling for 1-minute, followed by an instantaneous increase of the individualized workload, which was attained in ~3s. Participants were instructed to keep cycling at a cadence of 70 RPM for the entire duration of the trial. Each trial was ended after 30 minutes of exercise. EMG data were collected at the baseline (standstill sitting), during warm-up (unloaded cycling) and in constant-load exercise, in both experimental conditions (PEMF ON and PEMF OFF) (

Figure 2).

2.2. EMG Recordings

The response of muscular activity over the entire trial was recorded by surface EMG and assessed measuring the root mean square (RMS) normalized to the peak of the MVC. We averaged the values of baseline (standstill sitting), warm-up (unloaded cycling) and constant-load exercise for each condition (PEMF ON vs. PEMF OFF) in each muscle (RBF and RVM).

The software EMG easy report 6.03.8 (Merlo Bioengineering, Italy) was used for EMG data process and artefact removal [

29,

30,

31]. We used a wavelet-based denoising filter, in order to reduce background noise and automatically remove large and frequent artifacts on EMG traces [

32]. Starting from the raw signal, a peak emphasis operator, called Smoothed Non-Linear Energy Operator (SNEO) was applied [

32,

33,

34]. SNEO is similar to the Taeger-Kaiser, other operator frequently used with EMG signals [

34]. Peaks positions and amplitudes were founded using thresholds of the minimum amplitude and distance between PEMF peaks. The position of unrecognized stimulus was found with linear interpolation of the values obtained in the previous point. Found positions of the artifacts, the parts of the signal 20ms before and 80ms after peaks, were forced to zero. After that, the algorithm calculated the amplitude of the RMS limited at the signal of the muscle activity for each detected onset intervals. The activation intervals were calculated through specific algorithm [

32] using a mean background noise level, as 10uV RMS. Then, the values recorded were normalized to the peak of the MVC. The normalized RMS values were calculated in 100 ms bin from EMG signals using MATLAB (The MathWorks).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

A multivariate ANOVA, with conditions (PEMF ON and PEMF OFF) as the between-subjects factor and epochs (warm up, exercise, ON-OFF and OFF-ON) as the within-subjects factors, was applied for both RVM and RBF muscles. Means were considered significantly different at p < 0.05.

To determine the magnitude of the effect of PEMF stimulation we used paired sample t-test; effect sizes (ES) were calculated as the mean difference standardized by the between subject standard deviation and interpreted according to the thresholds [

35]:<0.20; small, >0.20-0.60; moderate, >0.60-1.20; large, >1.20-2.00; very large,>2.00-4.00; extremely large, >4.00. Data were analyzed with SPSS v22.0 (IBM, New York, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of PEMF Stimulation

The multivariate analysis of variance performed on RVM showed a significant effect of PEMF (F1,4=10,838; p< 0.001; η2p=0.798). The within-subjects analysis showed the following significant effects: warmup (F1,4=7.034 p=0.019 η2p=0.334), exercise ON-OFF (F1,4=7.509 p=0.016 η2p =0.349), exercise OFF-ON (F1,4=14.999 p=0.002 η2p =0.517), exercise in the first 17 minutes, (F1,4=7.307 p=0.017 η2p =0.343), exercise in the last 17 minutes, (F1,4=15.770 p=0.001 η2p =0.530).

The multivariate analysis performed on RBF showed a significant effect for conditions (F1,4=7,636; p=0.003; η2p =0.735). The within-subjects analysis showed a significant effect for warmup (F1,4=23.912 p<0.001 η2p =0.631).

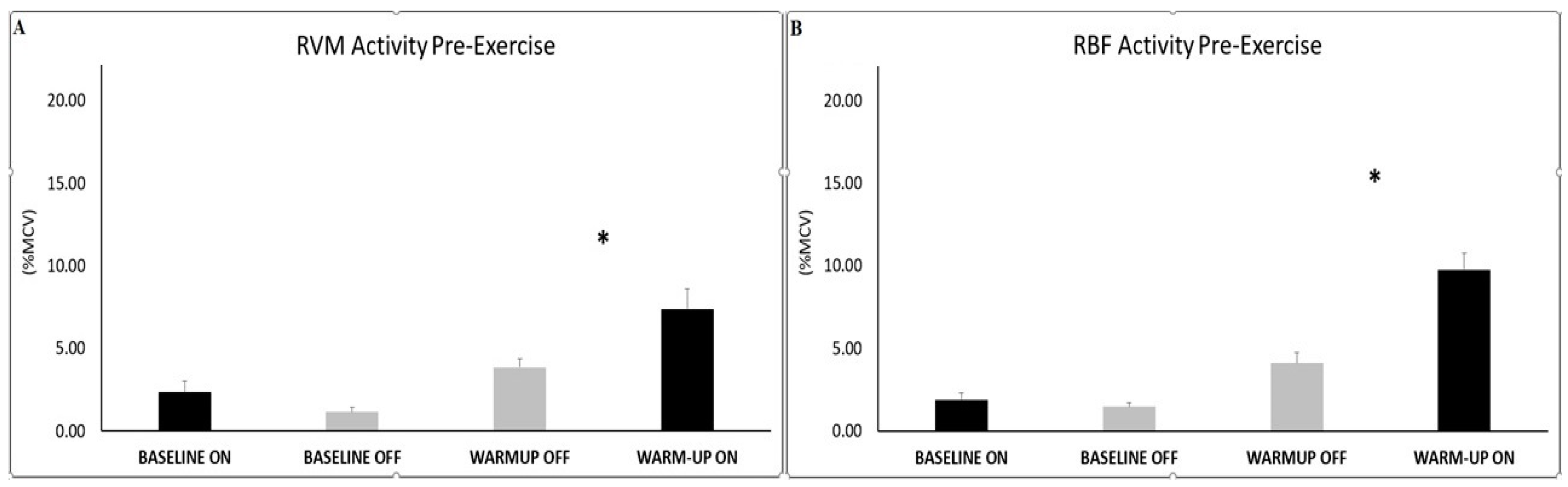

3.2. Effect of PEMF at Baseline and during Warmup

Analysis for muscle activity at the baseline did not show any significant differences between conditions (PEMF OFF vs. ON) for each investigated muscle (RVM and RBF). For both muscle investigated, significant differences were found during warm-up, in which PEMF-ON exhibited higher RMS value with respect to PEMF-OFF condition (RVM ON=7.38±1.23 vs OFF=3.84±0.53; t(7) = -2.32; p=0.027; ES 0.55-moderate; RBF ON=9.77±0.98 vs OFF=4.12±0.60; t(7) = -4.22; p=0.002; ES 0.77-large).

Figure 3.

Histograms represent the root mean square (RMS) of the normalized EMG values (mean ± SEM) of the RVM (A) and RBF (B) at the baseline and during warm-up, across experimental conditions (PEMF ON vs. OFF). Asterisks indicate significant differences at p<0.05.

Figure 3.

Histograms represent the root mean square (RMS) of the normalized EMG values (mean ± SEM) of the RVM (A) and RBF (B) at the baseline and during warm-up, across experimental conditions (PEMF ON vs. OFF). Asterisks indicate significant differences at p<0.05.

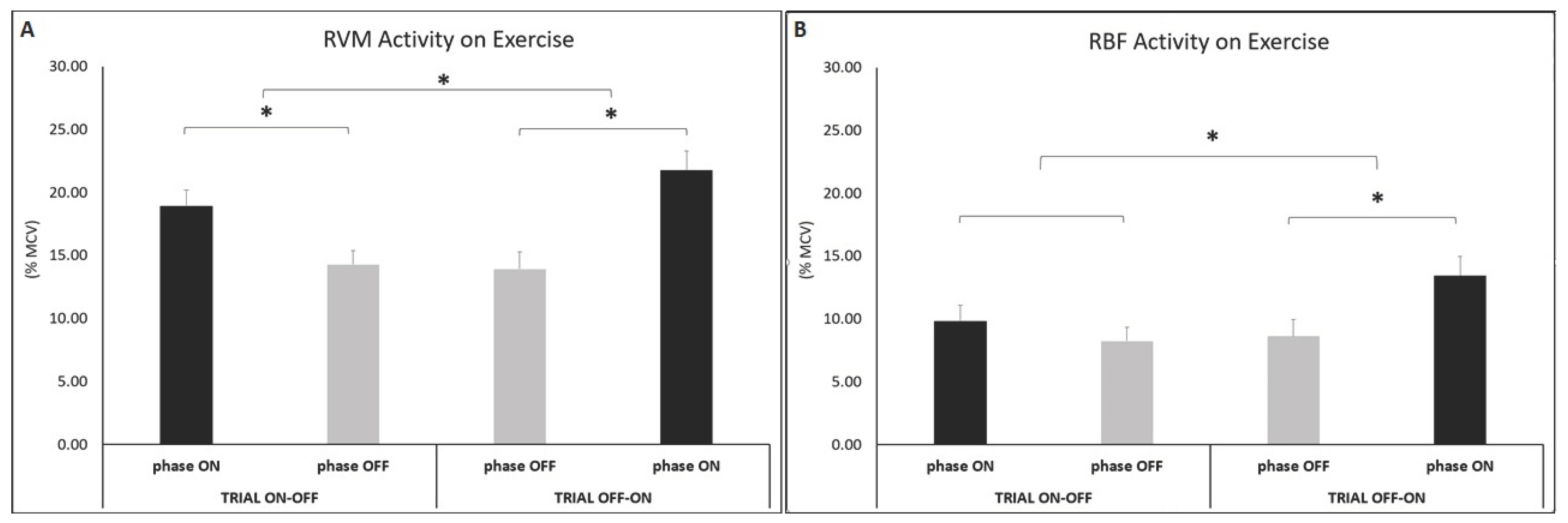

3.3. Effect of PEMF during Exercise

Analysis during epochs (OFF-ON and ON-OFF) showed significant differences between PEMF OFF and PEMF ON in the RVM muscle where the amplitude of EMG was higher during the condition ON with respect to OFF when the PEMF was OFF followed by ON (t(7) =-16.10 p<0.001; ES=0.70-large) than ON followed by OFF (t(7) =-18.11 p<0.001; ES=0.57-moderate).

Analysis for RBF activity showed difference across condition (PEMF OFF vs. PEMF ON) in trial OFF-ON. Stimulation caused a change of the muscular activation, with greater amplitude on PEMF ON condition (t(7) =-7.10 p<0.001; ES=0.39-moderate).

Analysis during physical effort, showed differences for RVM activity across time (trial ON-OFF vs. trial OFF-ON), in both first (t(7) =-8.61 p<0.001; ES=0.56-moderate) and second half of each trial (t(7) =-11.29 p<0.001; ES=0.70-large). Muscle activity was higher in ON condition with respect to OFF.

Analysis for RBF activity showed differences across parameter time (trial ON-OFF vs. trial OFF-ON), in the second half of the trial. Amplitude of muscle activity was higher in phase ON than OFF (t(7) =-2.88 p=0.012; ES=0.44-moderate), due to active PEMF stimulation.3.1.

Figure 4.

Histograms represent the root mean square (RMS) of the normalized EMG values of the RVM (A) and RBF (B) during constant-load exercise, across conditions (PEMF ON vs. PEMF OFF) within trial (phase ON vs. phase OFF) and between trials (trial ON-OFF vs. trial OFF-ON). Data are show mean ±SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences at p<0.05.

Figure 4.

Histograms represent the root mean square (RMS) of the normalized EMG values of the RVM (A) and RBF (B) during constant-load exercise, across conditions (PEMF ON vs. PEMF OFF) within trial (phase ON vs. phase OFF) and between trials (trial ON-OFF vs. trial OFF-ON). Data are show mean ±SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences at p<0.05.

4. Discussion

PEMF strongly enhanced the amplitude of muscle activity in young sedentary people for each investigated muscle. Stimulation increased the magnitude activity of muscle fibers on warm-up, for both vastus medialis and bicep femoris, and during constant-load exercise in vastus medialis. A tendency for a higher muscular basal tone during PEMF stimulation, was also noted for RVM activity, when subjects standstill sitting on cycle-ergometer with extended right leg (baseline). The increase in the amplitude of the muscular response induced by stimulation was likely caused by the effect of PEMF on contraction mechanism of muscular fibers, through a change of membrane permeability and Ca2+ channel conduction, enhancing ion flux and cellular concentration [

17,

18]. The mechanism of muscular contraction, which are affected by Ca2+ channels and ions flux and PEMF stimulation, could affected calcium channels and raise Ca2+ intracellular concentration [

19,

20], leading to improve contraction mechanisms. Further, PEMF stimulation could amplify signal Ca2+ mediators and Ca2+-dependent pathways, as showed in several studies [

22], probably through changes in phospholipids of plasma membrane, that improve production of second messengers, with starting cascade of multiple intracellular signal transduction [

23,

24,

25].

The analysis of muscle activity of RVM and RBF, showed a significantly higher activity for vastus medialis related to bicep femoris. This result is not surprising given that the effective role of vastus medialis during cycling is well-known, but the role of bicep femoris is still under study. The magnitude of the bicep femoris is more affected by fatigue, pedaling rate, coordination/activation timing (angle), training status, shoe-pedal interface and body position [

36]. Bicep femoris is a bi-articular muscle, involved in knee flexion and hip extension and seems to be more important for energy transfer, between joints during cycling rather than to supply main force [

36]. One of the largest activity and earliest activation of bicep femoris seem to be related to increased fatigue in both vastus lateralis and medialis as a consequence of modified coordination and activation patterns [

36]. In the present study, the workload was moderate causing a large response of the main muscles of cycling, such as vastus medialis and a low activation of the bicep femoris [

36].

Results of the present study showed that PEMF stimulation augmented the muscle activity during a low intensity exercise in sedentary people. In our previous study we found no statistical differences in muscle activity during a high intensity exercise in athletes [

26]. We hypothesized that the greater muscle activation evoked in the high intensity of effort of professional athletes, covered the effect of PEMF stimulation given that our cyclists performed strenuous exercise, which required a very high muscle activity. On the other hand, at low and medium intensity of exercise, PEMF stimulation increased muscle activity in both sedentary (during warm up and physical effort) and athletes (during warm-up).

5. Conclusions

PEMF stimulation increased amplitude of muscle fibers activity, according to exercise intensity and muscle fibers recruited. During light physical effort, as warm-up and during moderate constant-load exercise, stimulation increased overall activity of muscle fibers. Results of the present research show a possible application of PEMF in physical activity, in order to enhance the amplitude of muscular activity, in response to physical effort. PEMF stimulation, could be employed to augment the amplitude of muscular activity during work-out sessions, to improve muscular response to moderate or light workload and increase the benefits of the training program. Also, the augmented basal tone observed in standstill sitting, in addition to the higher muscle activity observed during warm-up, suggest a possible application of PEMF on preparatory activity before training, in order to raise the magnitude of muscular activation. Further, PEMF stimulation could also be applied in support to older-age people or subjects with a breakable muscle-joint structure, in order to increase overall muscular response during light exercise. An increase in amplitude of muscular activity induced by stimulation, could improve rehabilitation after injuries or hospitalizations. PEMF could facilitate exercise in people with fragile muscles and joints (e.g., osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome, post-surgery course), in order to boost the results of training session and encourage the adherence to physical activity programs.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research investigating PEMF stimulation during moderate exercise, in healthy and young sedentary people. Based on the present results, stimulation could be used during a moderate exercise, as well as during light physical effort, in order to increase overall muscular response. Also, PEMF could be used during warm-up, in order to raise the amplitude of muscular responses, during the preparatory activity before training. PEMF could be used during physical activity for multiple purposes. It could be important to investigate PEMF treatment in patients and older adults, whose daily mobility and life quality are limited by an impairment in muscle power or joint movement. These people could have greater benefits from therapeutic strategies that increase their muscle activation, a valuable aim for forthcoming investigations. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the stimulation parameters and exercise protocol necessary to make more effective and efficient PEMF stimulation on human subjects. We believe that these first observations could open new horizons in the field of physical activity.

Nevertheless, the accurate interaction between PEMF and human cells and tissue is unclear and needs further studies. Other stimulation parameters like time and frequency are worthy to be investigated given that it has been hypothesized that the different responses on PEMF therapy, depends on the biological tissue or dosage of stimulation of a specific electromagnetic signal [

37].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.; methodology, M.R. and A.P.; software, A.M. A.L, L.B; validation, M.R., A.P.; formal analysis, A.T; A.L; L.B.; investigation, A.T, L.B., A.L., A.M.; resources, M.R.; data curation, A.T.; A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.; AT; writing—review and editing, M.R; AT; visualization, A.P.; supervision, M.R.; project administration, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by University of Bologna RFO program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Bologna (protocol code 224109, approval date in 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the participants of the study. The authors are grateful to David Muesam for his vision and support of the study. The authors are thankful to Andrea Merlo (Merlo Bioengineering, Italy) for the development of the algorithm for removing PEMF artifacts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Markov, M.S. Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy History, State of the Art and Future. The Environmentalist 2007, 27, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adey, W.R. Biological Effects of Electromagnetic Fields. J. Cell. Biochem. 1993, 51, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.L.; Zhou, Y.; McCall, C.E.; Soker, S.; Criswell, T.L. The Use of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field to Modulate Inflammation and Improve Tissue Regeneration: A Review. Bioelectricity 2019, 1, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatscher, J.; Pavez Loriè, E.; Mittermayr, R.; Meznik, P.; Slezak, P.; Redl, H.; Slezak, C. Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields (PEMF)-Physiological Response and Its Potential in Trauma Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biermann, N.; Sommerauer, L.; Diesch, S.; Koch, C.; Jung, F.; Kehrer, A.; Prantl, L.; Taeger, C.D. The Influence of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy (PEMFT) on Cutaneous Blood Flow in Healthy Volunteers1. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2020, 76, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yao, F.; Cheng, L.; Cheng, W.; Qi, L.; Yu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zha, X.; Jing, J. Low Frequency Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Promotes the Recovery of Neurological Function after Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. 2019, 37, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, P.; Soejima, K.; Ito, G. Nitric Oxide Mediates the Effects of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Stimulation on the Osteoblast Proliferation and Differentiation. Nitric Oxide - Biol. Chem. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, J.C.; Prato, F.S.; Thomas, A.W. A Literature Review: The Effects of Magnetic Field Exposure on Blood Flow and Blood Vessels in the Microvasculature. Bioelectromagnetics 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pall, M.L. Electromagnetic Fields Act via Activation of Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels to Produce Beneficial or Adverse Effects. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.-H.; Wheatley-Guy, C.M.; Stewart, G.M.; Yeo, D.; Shen, W.-K.; Johnson, B.D. The Impact of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy on Blood Pressure and Circulating Nitric Oxide Levels: A Double Blind, Randomized Study in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome. Blood Press. 2020, 29, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, F.R.; Zvirbulis, R.; Pilla, A.A. Non-Invasive Electromagnetic Field Therapy Produces Rapid and Substantial Pain Reduction in Early Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Double-Blind Pilot Study. Rheumatol. Int. 2013, 33, 2169–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, Y.; Mori, A.; Liburdy, R.P.; Packer, L. Pulsed Magnetic Fields Enhance Nitric Oxide Synthase Activity in Rat Cerebellum. Pathophysiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Pathophysiol. 2000, 7, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Takayama, K.; Okada, J. Increase in Nitric Oxide and Cyclic GMP of Rat Cerebellum by Radio Frequency Burst-Type Electromagnetic Field Radiation. J. Physiol. 1993, 461, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamulevicius, N.; Wadhi, T.; Oviedo, G.R.; Anand, A.S.; Tien, J.-J.; Houston, F.; Vlahov, E. Effects of Acute Low-Frequency Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy on Aerobic Performance during a Preseason Training Camp: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trofè, A.; Raffi, M.; Muehsam, D.; Meoni, A.; Campa, F.; Toselli, S.; Piras, A. Effect of PEMF on Muscle Oxygenation during Cycling: A Single-Blind Controlled Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, T.; Satake, A.; Sumi, S.; Inoue, K.; Miyakoshi, J. An Extremely Low Frequency Magnetic Field Attenuates Insulin Secretion from the Insulinoma Cell Line, RIN-m. Bioelectromagnetics 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.L.; Siriwardane, M.; Almeida-Porada, G.; Porada, C.D.; Brink, P.; Christ, G.J.; Harrison, B.S. The Effect of Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Field on Human Bone Marrow Stem/Progenitor Cell Differentiation. Stem Cell Res. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov, A.G.; Bowman, A.M.; Ibey, B.L.; Andre, F.M.; Pakhomova, O.N.; Schoenbach, K.H. Lipid Nanopores Can Form a Stable, Ion Channel-like Conduction Pathway in Cell Membrane. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Pan, L.; Lee, I. Magnetic Fields at Extremely Low-Frequency (50 Hz, 0.8 mT) Can Induce the Uptake of Intracellular Calcium Levels in Osteoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan-Jung Li, J.; Cheng-An Lin, J.; Liu, H.C.; Sun, J.S.; Ruaan, R.C.; Shih, C.; Hong-Shong Chang, W. Comparison of Ultrasound and Electromagnetic Field Effects on Osteoblast Growth. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Sun, L.; Fan, X.; Yin, B.; Kang, Y.; An, S.; Tang, L. Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields Alleviate Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Muscle Atrophy. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagopoulos, D.J.; Karabarbounis, A.; Margaritis, L.H. Mechanism for Action of Electromagnetic Fields on Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, I.; Xiao, S.; Pakhomov, A.G. Primary Pathways of Intracellular Ca(2+) Mobilization by Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolstykh, G.P.; Beier, H.T.; Roth, C.C.; Thompson, G.L.; Payne, J.A.; Kuipers, M.A.; Ibey, B.L. Activation of Intracellular Phosphoinositide Signaling after a Single 600 Nanosecond Electric Pulse. Bioelectrochemistry Amst. Neth. 2013, 94, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilla, A.; Fitzsimmons, R.; Muehsam, D.; Wu, J.; Rohde, C.; Casper, D. Electromagnetic Fields as First Messenger in Biological Signaling: Application to Calmodulin-Dependent Signaling in Tissue Repair. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1810, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trofè, A.; Piras, A.; Muehsam, D.; Meoni, A.; Campa, F.; Toselli, S.; Raffi, M. Effect of Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields (PEMFs) on Muscular Activation during Cycling: A Single-Blind Controlled Pilot Study. Healthc. Basel Switz. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffi, M.; Piras, A.; Persiani, M.; Perazzolo, M.; Squatrito, S. Angle of Gaze and Optic Flow Direction Modulate Body Sway. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Electrophysiol. Kinesiol. 2017, 35, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, A.; Zini, L.; Trofè, A.; Campa, F.; Raffi, M. Effects of Acute Microcurrent Electrical Stimulation on Muscle Function and Subsequent Recovery Strategy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinti, M.; Bayle, N.; Merlo, A.; Authier, G.; Pesenti, S.; Jouve, J.-L.; Chabrol, B.; Gracies, J.-M.; Boulay, C. Muscle Shortening and Spastic Cocontraction in Gastrocnemius Medialis and Peroneus Longus in Very Young Hemiparetic Children. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2328601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanini, I.; Cosma, M.; Manca, M.; Merlo, A. Added Value of Dynamic EMG in the Assessment of the Equinus and the Equinovarus Foot Deviation in Stroke Patients and Barriers Limiting Its Usage. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 583399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, D.; Giannotti, E.; Manca, M.; Longhi, M.; Prati, P.; Cosma, M.; Ferraresi, G.; Morelli, M.; Zerbinati, P.; Masiero, S.; et al. Electromyographic Activity of the Vastus Intermedius Muscle in Patients with Stiff-Knee Gait after Stroke. A Retrospective Observational Study. Gait Posture 2018, 60, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, A.; Farina, D.; Merletti, R. A Fast and Reliable Technique for Muscle Activity Detection from Surface EMG Signals. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 50, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Ray, G.C. A New Interpretation of Nonlinear Energy Operator and Its Efficacy in Spike Detection. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1998, 45, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solnik, S.; Rider, P.; Steinweg, K.; DeVita, P.; Hortobágyi, T. Teager-Kaiser Energy Operator Signal Conditioning Improves EMG Onset Detection. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hug, F.; Dorel, S. Electromyographic Analysis of Pedaling: A Review. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.L.; Wong-Gibbons, D.; Maultsby, J. Microcirculatory Effects of Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields. J. Orthop. Res. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).