Submitted:

19 March 2024

Posted:

21 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Conditions and Materials

2.2. Analysis of the Chemical Characteristics of Grapes

2.3. Determination of Meteorological Data

2.4. Analysis of GLV Compounds in Grapes by GC-MS

2.5. Odour Activity Values

2.6. Expression of LOX-HPL Pathway Genes

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Primary Chemical Characteristics of Berries

3.2. Green Leaf Volatile Evolution

3.3. Analysis of Green Leaf Volatile Profiles in Grapes as They Mature

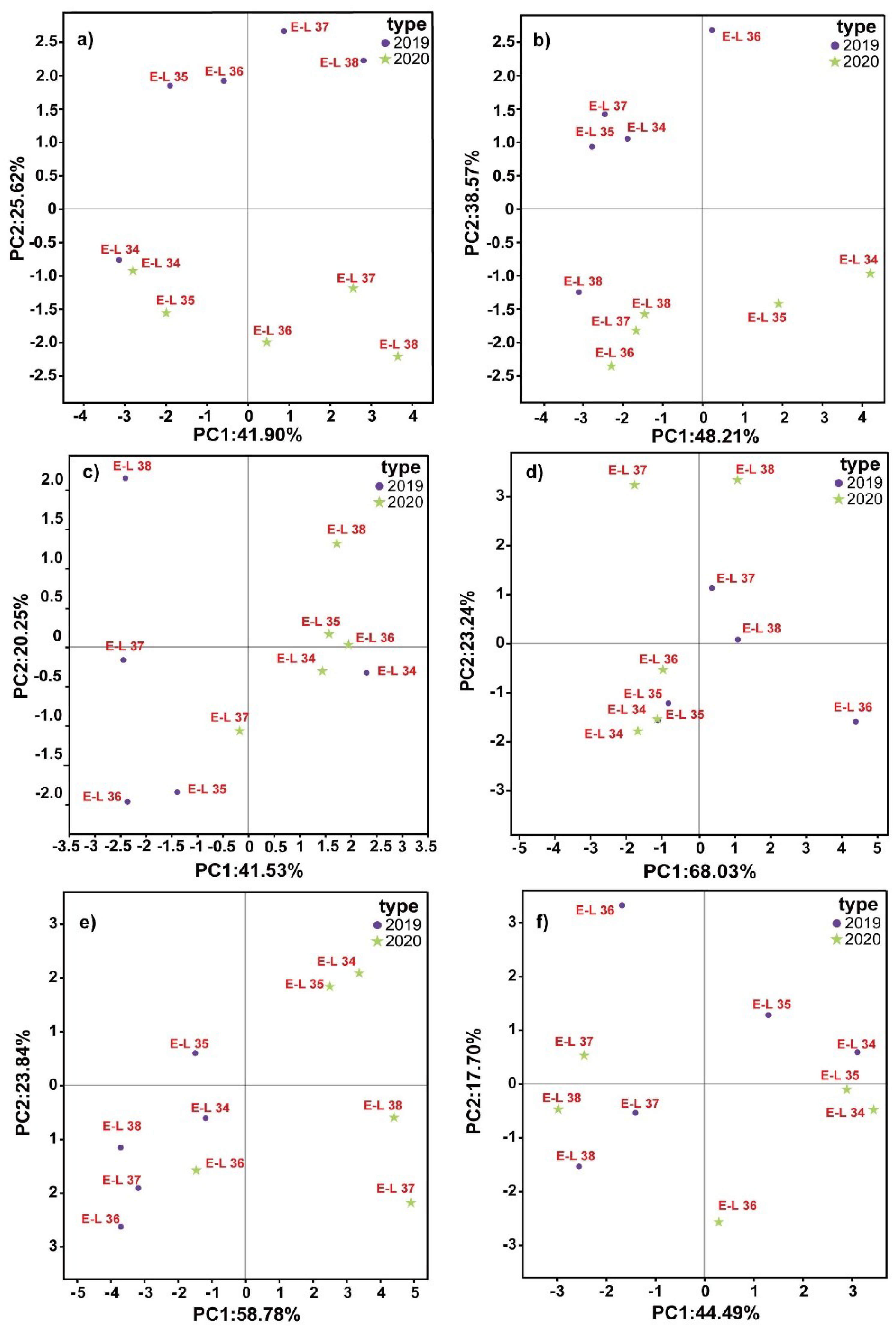

3.4. GLV Evolution Pattern Recognition

3.5. Aroma Activity Analysis

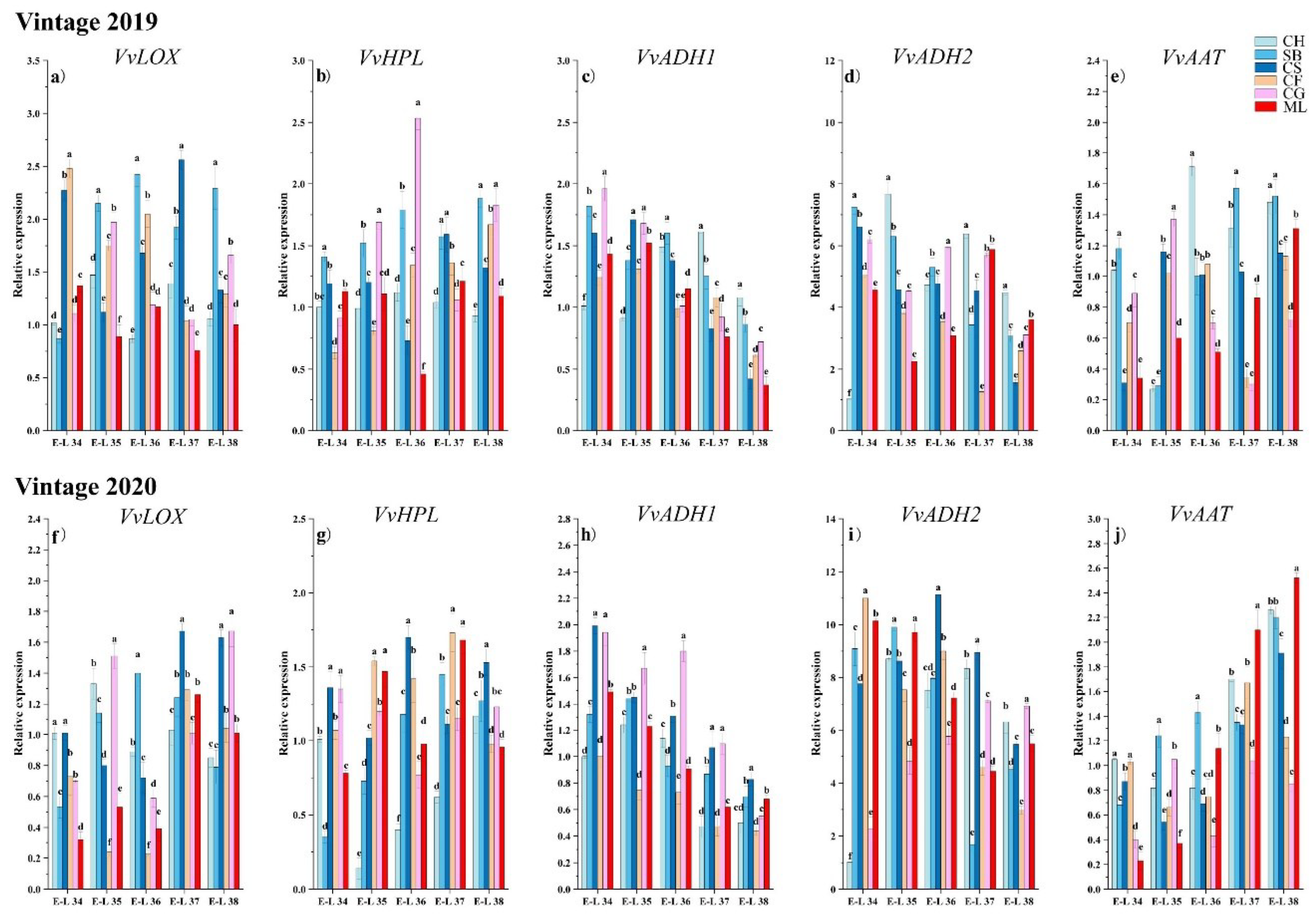

3.6. Expression of Genes in LOX-HPL Pathway

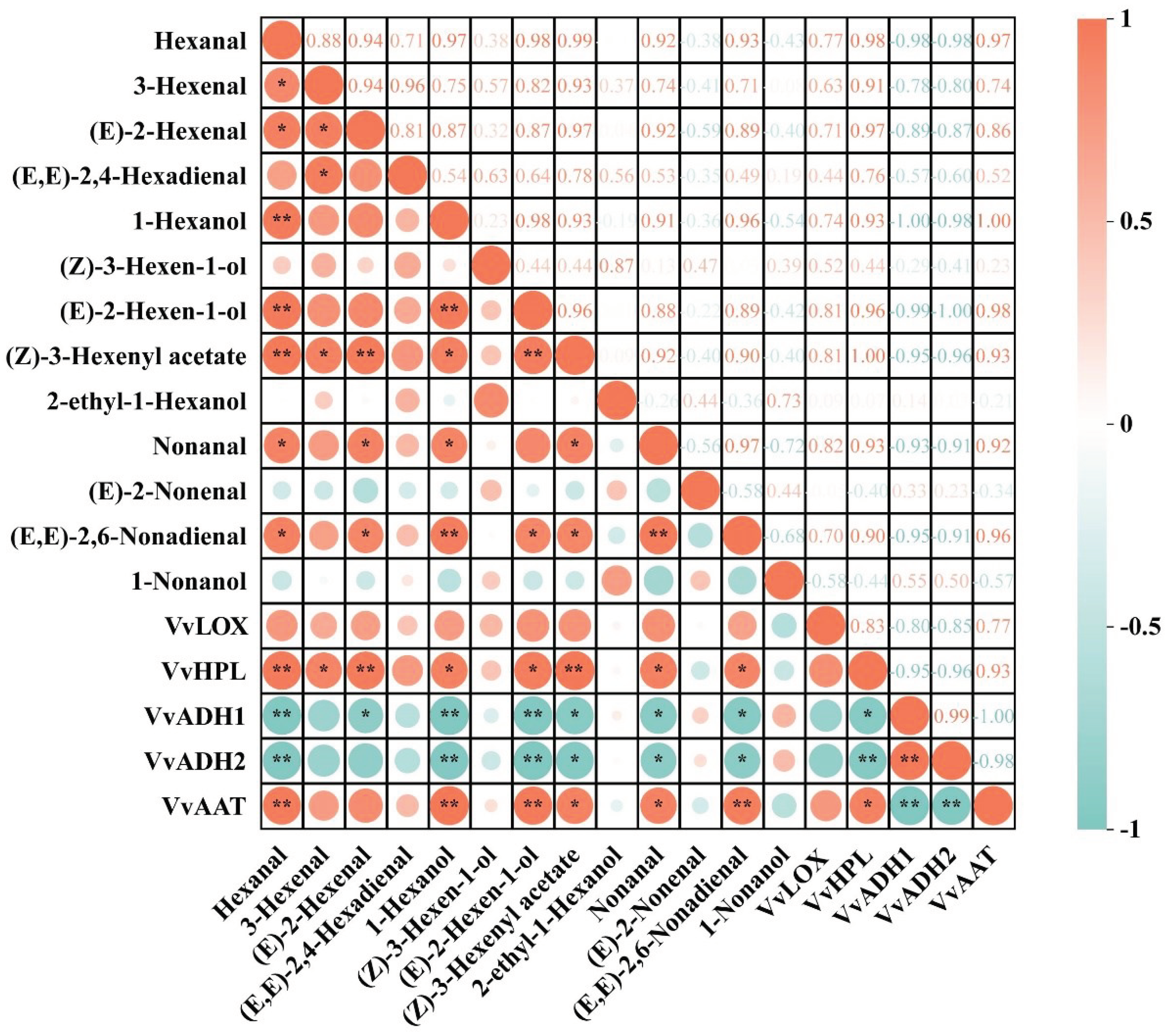

3.7. Correlation Analysis

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Du, T.; Jia, J.; Xi, Z. The Expression of Aroma Components and Related Genes in Merlot and Marselan Scion-Rootstock Grape and Wine. Foods 2022, 11, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Lv, Y.; Nan, H.; Wen, L.; Wang, Z. Research progress of wine aroma components: A critical review. Food Chemistry 2023, 402, 134491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Ju, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis reveals the changes in monoterpene compounds during the development of Muscat Hamburg (Vitis vinifera L.) grape berries. Food Research International 2022, 162, 112065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godshaw, J.; Hjelmeland, A.K.; Zweigenbaum, J.; Ebeler, S.E. Changes in glycosylation patterns of monoterpenes during grape berry maturation in six cultivars of Vitis vinifera. Food Chemistry 2019, 297, 124921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wen, J.; Ma, L.; Wen, H.; Li, J. Dynamic changes in norisoprenoids and phenylalanine-derived volatiles in off-vine Vidal blanc grape during late harvest. Food Chemistry 2019, 289, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.Q.; Cheng, G.; Duan, L.L.; Jiang, R.; Pan, Q.H.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J. Effect of training systems on fatty acids and their derived volatiles in Cabernet Sauvignon grapes and wines of the north foot of Mt. Tianshan. Food Chemistry 2015, 181, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, X.; Zha, Q.; He, Y.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, A. Influence of cluster thinning and girdling on aroma composition in 'Jumeigui' table grape. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillon, O.; Aury, J.-M.; Noel, B.; Policriti, A.; Clepet, C.; Casagrande, A.; Choisne, N.; Aubourg, S.; Vitulo, N.; Jubin, C. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature 2007, 449, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Y.L.; Yue, X.F.; Cao, X.Y.; Wei, X.F.; Fang, Y.L. First study on the fatty acids and their derived volatile profiles from six Chinese wild spine grape clones (Vitis davidii Foex). Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 275, 109709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D.; Valdes, E.; Uriarte, D.; Gamero, E.; Talaverano, I.; Vilanova, M. Early leaf removal applied in warm climatic conditions: Impact on Tempranillo wine volatiles. Food Research International 2017, 98, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Yu, A.; Ji, X.; Mu, Q.; Haider, M.S.; Wei, R.; Leng, X.; Fang, J. Transcriptome and metabolite integrated analysis reveals that exogenous ethylene controls berry ripening processes in grapevine. Food Research International 2022, 155, 111804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Ju, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yu, R.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z. Application of salicylic acid to cv. Muscat Hamburg grapes for quality improvement: Effects on typical volatile aroma compounds and anthocyanin composition of grapes and wines. Lwt-Food Science and Technology 2023, 182, 114828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Abbey, T.; Kozak, B.; Madilao, L.L.; Tindjau, R.; Del Nin, J.; Castellarin, S.D. Evolution over the growing season of volatile organic compounds in Viognier (Vitis vinifera L.) grapes under three irrigation regimes. Food Research International 2019, 125, 10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Wang, P.; He, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Fang, Y.; Sun, X. Using foliar nitrogen application during veraison to improve the flavor components of grape and wine. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2021, 101, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Wu, G.; Ren, R.; Xie, R.; Yin, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, M. Transcriptomic and metabolic analyses reveal differences in monoterpene profiles and the underlying molecular mechanisms in six grape varieties with different flavors. Lwt-Food Science and Technology 2023, 174, 114442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Jin, X.; Feng, M.; Xu, G.; Zhang, P.; Fang, Y.; Xu, T.; Meng, J. Evolution of volatile profile and aroma potential of table grape Hutai-8 during berry ripening. Food Research International 2021, 143, 110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, H.; Rigou, P.; Schneider, R.; Ojeda, H.; Torregrosa, L. Impact of agronomic practices on grape aroma composition: a review. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2019, 99, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Brotchie, J.; Pang, M.; Marriott, P.J.; Howell, K.; Zhang, P. Free terpene evolution during the berry maturation of five Vitis vinifera L. cultivars. Food Chemistry 2019, 299, 125101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antalick, G.; Suklje, K.; Blackman, J.W.; Meeks, C.; Deloire, A.; Schmidtke, L.M. Influence of Grape Composition on Red Wine Ester Profile: Comparison between Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz Cultivars from Australian Warm Climate. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2015, 63, 4664–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Xi, Y.R.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.N.; Xu, Y. Chemical and Sensory Characterization of Cabernet Sauvignon Wines from the Chinese Loess Plateau Region. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombe, B.G. Growth Stages of the Grapevine: Adoption of a system for identifying grapevine growth stages. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 1995, 1, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.Q.; He, F.; Zhu, B.Q.; Lan, Y.B.; Pan, Q.H.; Li, C.Y.; Reeves, M.J.; Wang, J. Free and glycosidically bound aroma compounds in cherry (Prunus avium L.). Food Chemistry 2014, 152, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yan, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Pan, Q.; Xu, H.; Sun, L.; Zhu, B. Alcohol acyltransferase gene and ester precursors differentiate composition of volatile esters in three interspecific hybrids of Vitis labrusca xV. Vinifera during berry development period. Food Chemistry 2019, 295, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, S.; Gao, W.; Hu, B.; Zhu, B.; Sun, L. Monoterpenoids Evolution and MEP Pathway Gene Expression Profiles in Seven Table Grape Varieties. Plants-Basel 2022, 11, 1162143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Massonnet, M.; Cantu, D. The genetic basis of grape and wine aroma. Horticulture Research 2019, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.C.; Chen, W.K.; Wang, Y.; Bai, X.-J.; Cheng, G.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J.; He, F. Effect of the Seasonal Climatic Variations on the Accumulation of Fruit Volatiles in Four Grape Varieties Under the Double Cropping System. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 12, 809558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Yan, A.; Liu, Z.; Ren, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, L. Metabolomic and transcriptomic integrated analysis revealed the decrease of monoterpenes accumulation in table grapes during long time low temperature storage. Food Research International 2023, 174, 113601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakimov, B.; Bakhytkyzy, I.; Fauhl-Hassek, C.; Engelsen, S.B. Non-volatile molecular composition and discrimination of single grape white of chardonnay, riesling, sauvignon blanc and silvaner using untargeted GC-MS analysis. Food Chemistry 2022, 369, 130878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.O.; Lee, D.H.; Park, S.J.; Im, D.; Hur, Y.Y.; Kim, S.J. Changes in Biochemical and Volatile Flavor Compounds of Shine Muscat at Different Ripening Stages. Applied Sciences-Basel 2020, 10, 5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Barreiro, C.; Rial-Otero, R.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gandara, J. Wine Aroma Compounds in Grapes: A Critical Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2015, 55, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, C.; Chalot, G. Chemical composition, bioactive compounds, and volatiles of six table grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L.). Food Chemistry 2018, 240, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.N.; He, L.; He, F.; Chen, W.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J. Changes in global aroma profiles of Cabernet Sauvignon in response to cluster thinning. Food Research International 2019, 122, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Song, S.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Evolution of volatile compounds during the development of Muscat grape 'Shine Muscat' (Vitis labrusca x V. vinifera). Food Chemistry 2020, 309, 125778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Sun, L.; Xu, X.Q.; Zhu, B.Q.; Xu, H.Y. Differential Expression of VvLOXA Diversifies C6 Volatile Profiles in Some Vitis vinifera Table Grape Cultivars. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18(12), 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, F.; Ke, Y.; Yu, R.; Yue, Y.; Amanullah, S.; Jahangir, M.M.; Fan, Y. Volatile terpenoids: multiple functions, biosynthesis, modulation and manipulation by genetic engineering. Planta 2017, 246, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.Q.; Xu, X.Q.; Wu, Y.W.; Duan, C.Q.; Pan, Q.H. Isolation and characterization of two hydroperoxide lyase genes from grape berries. Molecular Biology Reports 2012, 39, 7443–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souleyre, E.J.F.; Chagne, D.; Chen, X.; Tomes, S.; Turner, R.M.; Wang, M.Y.; Maddumage, R.; Hunt, M.B.; Winz, R.A.; Wiedow, C. The AAT1 locus is critical for the biosynthesis of esters contributing to "ripe apple' flavour in "Royal Gala' and "Granny Smith' apples. Plant Journal 2014, 78, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesniere, C.; Davies, C.; Sreekantan, L.; Bogs, J.; Thomas, M.; Torregrosa, L. Analysis of the transcript levels of VvAdh1, VvAdh2 and VvGrip4, three genes highly expressed during Vitis vinifera L. berry development. Vitis 2006, 45, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Xu, X.Q.; Yu, K.J.; Zhu, B.Q.; Lan, Y.B.; Duan, C.Q.; Pan, Q.H. Varietal Dependence of GLVs Accumulation and LOX-HPL Pathway Gene Expression in Four Vitis vinifera Wine Grapes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 111924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

) vintage. Legend: (a) Chardonnay, (b) Sauvignon Blanc, (c) Cabernet Sauvignon, (d) Cabernet Franc, (e) Cabernet Gernischt and (f) Marselan. (Consult the online version of this article for an elucidation of the color codes mentioned in the figure legend.).

) vintage. Legend: (a) Chardonnay, (b) Sauvignon Blanc, (c) Cabernet Sauvignon, (d) Cabernet Franc, (e) Cabernet Gernischt and (f) Marselan. (Consult the online version of this article for an elucidation of the color codes mentioned in the figure legend.).

) vintage. Legend: (a) Chardonnay, (b) Sauvignon Blanc, (c) Cabernet Sauvignon, (d) Cabernet Franc, (e) Cabernet Gernischt and (f) Marselan. (Consult the online version of this article for an elucidation of the color codes mentioned in the figure legend.).

) vintage. Legend: (a) Chardonnay, (b) Sauvignon Blanc, (c) Cabernet Sauvignon, (d) Cabernet Franc, (e) Cabernet Gernischt and (f) Marselan. (Consult the online version of this article for an elucidation of the color codes mentioned in the figure legend.).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).