3.1. NMR Profiling and Differentiation of Young and Mature Wines and Grape Ales

The chemical profiles of nine young wines and nine mature wines, derived from three grape varieties, were investigated through the application of ¹H NMR spectroscopy. Furthermore, four grape ales were procured and subjected to the same analysis. A total of 37 compounds commonly found in beverages were identified across both products, including alcohols, organic acids, amino acids, saccharides, nucleosides, and other substances such as choline and trigonelline. The minimum and maximum concentrations of these compounds are presented in Table 1, along with the corresponding chemical shifts and multiplicities of the corresponding signals used for quantification.

Table 1.

Minimum and maximum concentrations in mg/L of the identified compounds in wines and grape ales, along with the chemical shifts/multiplicities used for quantitation at pH = 3.10.

Table 1.

Minimum and maximum concentrations in mg/L of the identified compounds in wines and grape ales, along with the chemical shifts/multiplicities used for quantitation at pH = 3.10.

| Compounds |

Young wine |

Mature wine |

Grape ale |

1H δ |

Multiplicity* |

| (mg/L) |

(n=9) |

(n=9) |

(n=4) |

(ppm) |

|

| Alcohols |

| 2,3-Butanediol (2,3Bd) |

218-429 |

337-730 |

120-595 |

1.13 |

d |

| Glycerol (GlycOH) |

5148-8760 |

9847-13688 |

1317-5153 |

3.55 |

dd |

| Isobutanol (iBuOH) |

13-75 |

29-67 |

36-214 |

1.73 |

m |

| Isopentanol (iPentOH) |

91-136 |

156-299 |

76-150 |

1.43 |

q |

| Methanol (MeOH) |

21-158 |

20-245 |

12-50 |

3.35 |

s |

| Myo-Inositol (myoIn) |

217-406 |

349-3373 |

0-432 |

4.05 |

t |

| 2-Phenylethanol (2PhEt) |

7-72 |

14-69 |

27-55 |

7.36 |

m |

| 1-Propanol (1PrOH) |

9-31 |

19-73 |

31-58 |

1.54 |

m |

| Organic acids |

| Citric acid (CitA) |

60-117 |

0-519 |

0-224 |

2.93 |

d |

| Galacturonic acid (GalA) |

118-826 |

41-1399 |

146-602 |

5.31 |

d |

| Formic acid (FoA) |

0-2 |

0-21 |

0-1 |

8.31 |

s |

| Lactic acid (LA) |

76-472 |

208-1816 |

42-3932 |

1.4 |

d |

| Malic acid (MalA) |

0-923 |

0-1761 |

0-165 |

2.87 |

dd |

| Shikimic acid (ShA) |

3-18 |

6-30 |

0 |

6.8 |

m |

| Succinic acid (SA) |

131-836 |

328-1069 |

199-534 |

2.65 |

s |

| Tartaric acid (TA) |

648-1300 |

1019-2295 |

572-879 |

4.55 |

s |

| Amino acids |

| Alanine (Ala) |

2-28 |

8-58 |

34-123 |

1.47 |

d |

| Histidine (His) |

0 |

0 |

45293 |

7.84 |

s |

| Proline (Pro) |

211-1269 |

301-3045 |

713-1467 |

2.35 |

m |

| Tyrosine (Tyr) |

9-30 |

1-56 |

13-89 |

7.18 |

d |

| Saccharides |

| Arabinose (Ara) |

8-132 |

0-412 |

18-111 |

4.45 |

d |

| Fructose (F) |

0-452 |

0-498 |

0 |

3.99 |

m |

| Galactose (Gal) |

20271 |

23-180 |

16377 |

5.25 |

d |

| Glucose (G) |

39-515 |

12-1033 |

331-922 |

4.59 |

d |

| Sucrose (Su) |

11-47 |

0-97 |

28-164 |

5.43 |

d |

| Phenolic compounds |

| Caffeic acid (Caffa) |

0 |

0-21 |

0-6 |

6.33 |

d |

| Caftaric acid (CaftA) |

0-214 |

0-85 |

7-13 |

6.43 |

d |

| Coutaric acid (CoutA) |

0-15 |

0-24 |

5-10 |

6.45 |

d |

| Nucleobases and nucleosides |

| Adenosine (Ado) |

0 |

0 |

31-59 |

8.36 |

s |

| Guanosine (Guo) |

0 |

0 |

14-45 |

8 |

s |

| Inosine (Ino) |

0 |

0 |

2-56 |

8.34 |

s |

| Thymidine (Thm) |

0 |

0 |

4-19 |

7.65 |

s |

| Uracil (Urc) |

0 |

0 |

0-41 |

7.52 |

d |

| Other |

| Acetaldehyde (MeCHO) |

0-36 |

0-13 |

0-3 |

9.67 |

q |

| Acetoin (Acet) |

0-11 |

0-103 |

6-34 |

2.22 |

s |

| Choline (Cho) |

11-23 |

17-46 |

5-14 |

3.19 |

s |

| Trigonelline (Tri) |

4-10 |

5-43 |

15-108 |

9.12 |

s |

Of the identified compounds, 29 were present in both the wine and the grape ale samples. However, six compounds — uracil, thymidine, histidine, guanosine, inosine, and adenosine—were identified as distinctive to grape ale. It is probable that these amino acids and nucleobases have their origin in the malts used in brewing, since the yeast species concerned is common to both beer and wine fermentation [

23].

The presence of shikimic acid and fructose was exclusive to wines. This may be attributed to the distinctive attributes of grape fermentation. Shikimic acid, which is extracted from grape skins, is not typically found in the ingredients used in brewing, such as malted grains [

24]. Furthermore, the fermentation of grapes in winemaking permits the retention of natural sugars such as fructose, which may not persist in grape ales due to the fermentation process employed in brewing, whereby yeast more efficiently consumes available sugars.

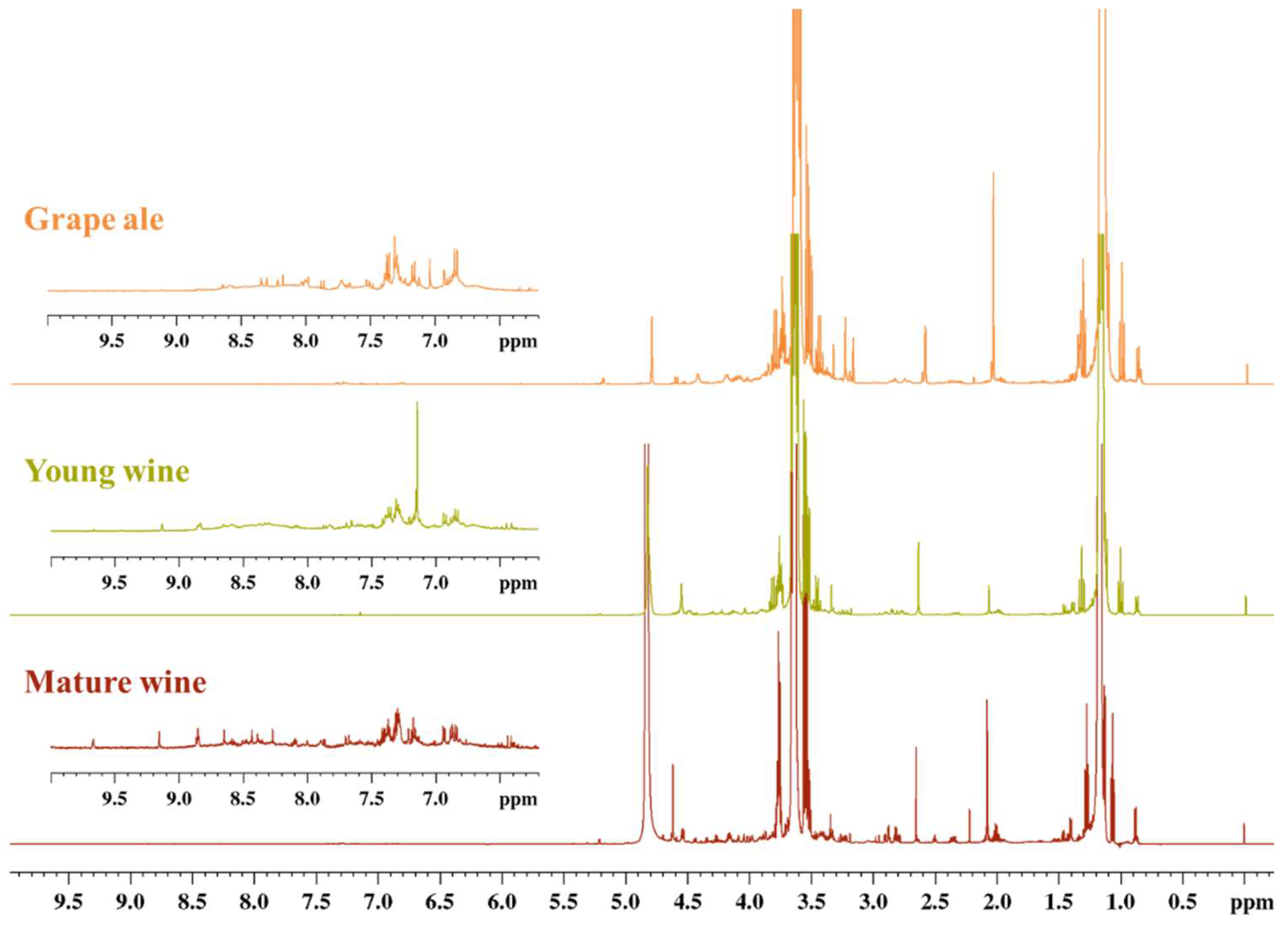

A comparison of the ¹H NMR spectra with water suppression for young and mature wines and grape ale is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

¹H NMR spectra of mature wine (red, sb_m1), young wine (olive, sb_y2), and grape ale (orange, ga_3).

Figure 1.

¹H NMR spectra of mature wine (red, sb_m1), young wine (olive, sb_y2), and grape ale (orange, ga_3).

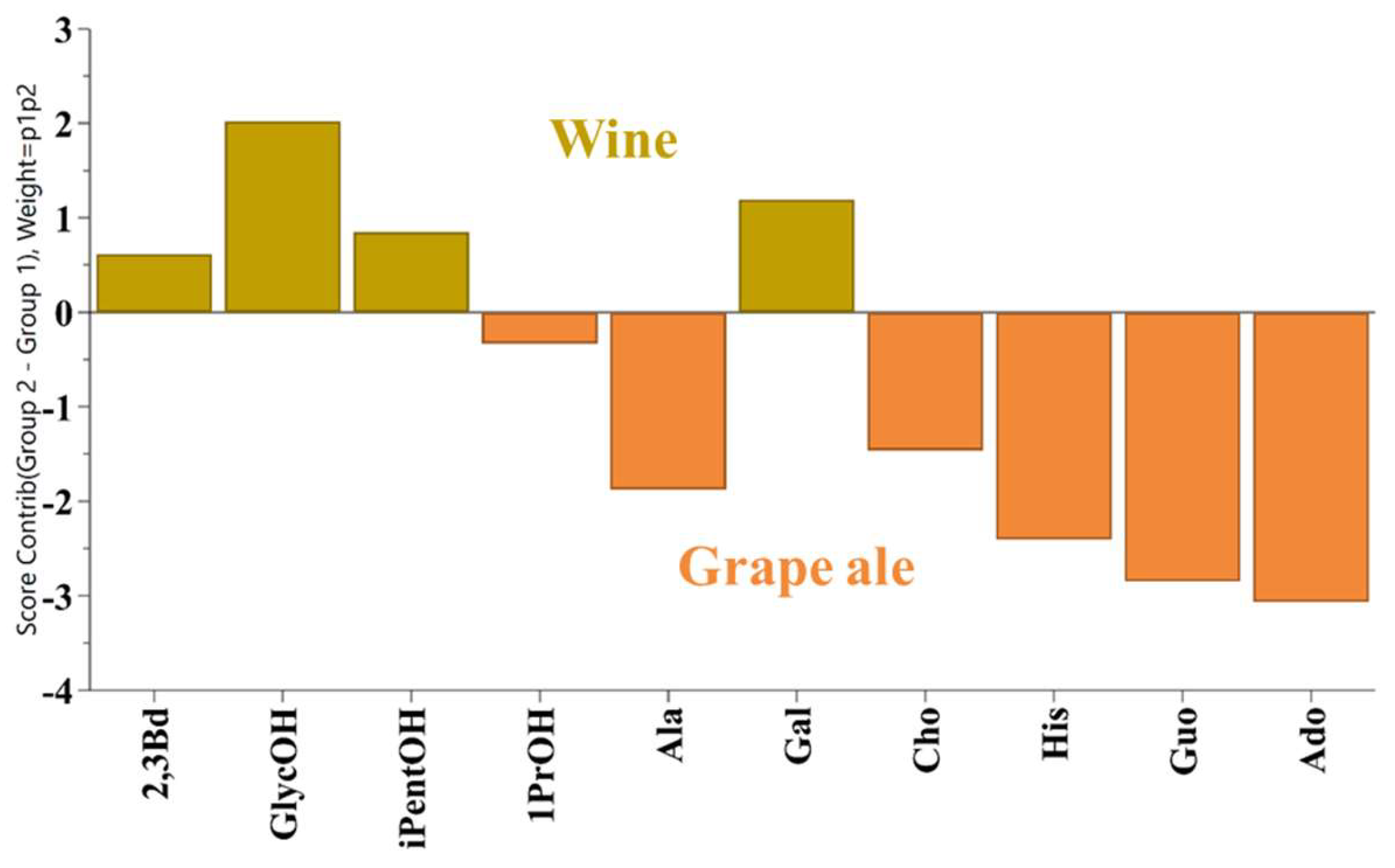

As anticipated, the primary compounds identified in the NMR spectra are ethanol and glycerol, in addition to organic acids such as acetic, lactic, succinic, tartaric and amino acid proline. The differences between the samples are slight, as illustrated in Figure 1. Only a comprehensive statistical examination of the quantitative data can elucidate the subtle distinctions between grape ale, young wine, and mature wine. To evaluate these differences, OPLS-DA was employed, utilizing the quantitative data of 37 compounds. Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores were used to identify statistically significant metabolites that could serve to discriminate between these classes. A total of 10 compounds with VIP scores greater than 0.94 were identified as significant. These included four higher alcohols (2,3-butanediol, glycerol, isopentanol and 1-propanol), two amino acids (alanine and histidine), one monosaccharide (galactose), two purine nucleosides (adenosine and guanosine), and choline. The contribution plot in Figure 2 elucidates the significant compounds that differentiate wine (young and mature) from grape ale. It demonstrates that wines are distinguished by elevated levels of 2,3-butanediol, glycerol, isopentanol, and galactose, whereas grape ales are more closely associated with 1-propanol, alanine, histidine, choline, adenosine, and guanosine.

Figure 2.

Contribution plot of wines (yellow) and grape ale (orange).

Figure 2.

Contribution plot of wines (yellow) and grape ale (orange).

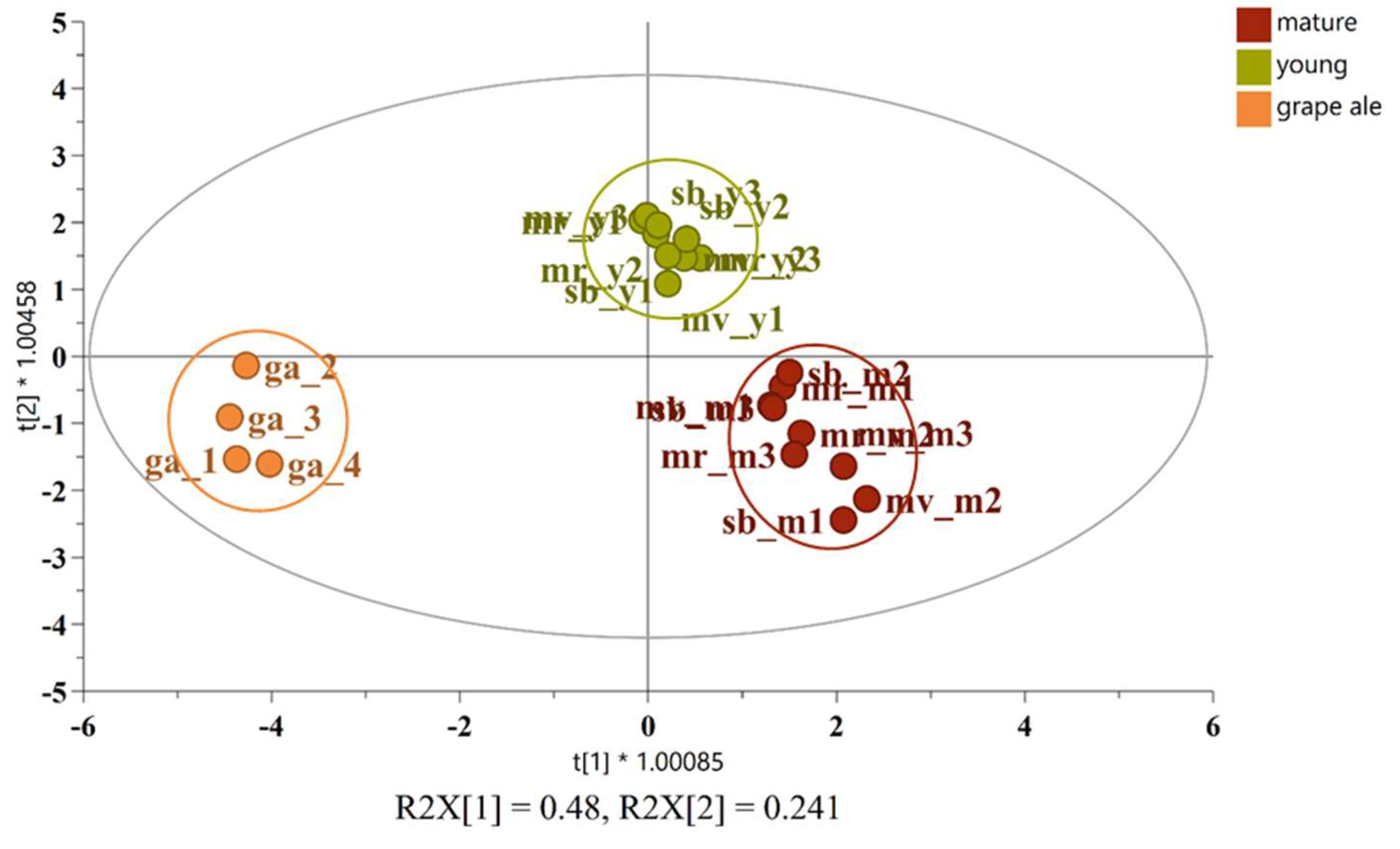

A novel OPLS-DA model was constructed based on the 10 most significant substances, enabling the clear differentiation of the three alcoholic products. The efficacy of this model in discerning between diverse sample types is illustrated by the score plot in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

OPLS-DA score plot for the classification of young wine (olive), mature wine (red), and grape ale (orange).

Figure 3.

OPLS-DA score plot for the classification of young wine (olive), mature wine (red), and grape ale (orange).

The mean content of the majority of identified alcohols, with the exception of isobutanol and 1-propanol, is markedly elevated in both young and mature wines in comparison to grape ale. For instance, the mean concentration of glycerol is 7299 mg/L in young wines, 12296 mg/L in aged wines, and only 3351 mg/L in grape ale. The differences in the concentration of specific alcohols between wines and ales span a considerable range from 3% to 78%. This can be attributed to the longer fermentation process of wine and the different yeast strains used, which are often more efficient at converting sugars to alcohol and producing a variety of higher alcohols. Additionally, wines contain higher concentration of galactose and fructose, which are naturally present in grape skins and seeds. Conversely, grape ales exhibit higher levels of alanine and histidine, which are likely derived from the malted grains. The comprehensive differences between young and mature wines are illustrated in the Nightingale diagram in Figure 4.

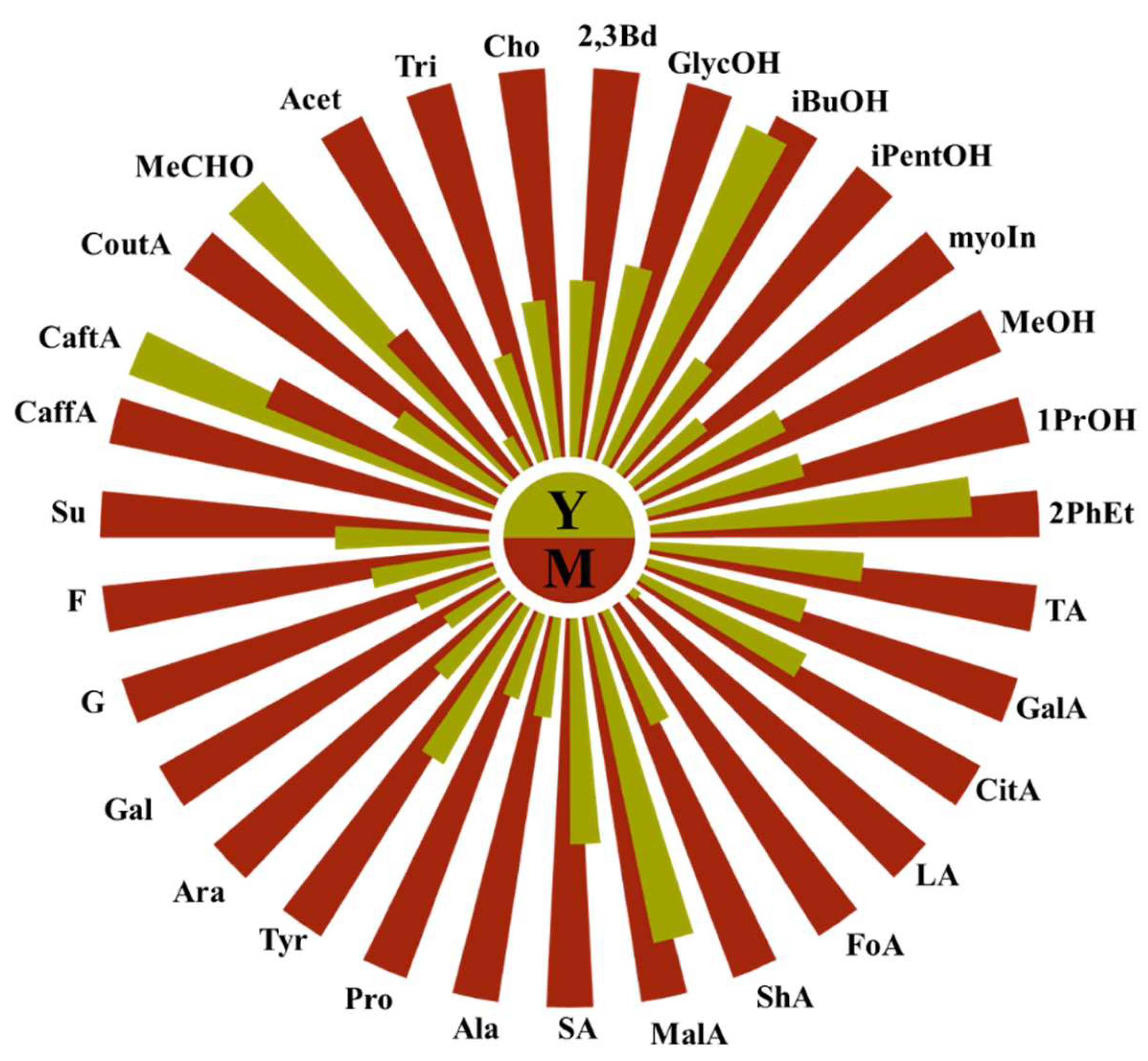

Figure 4.

Nightingale diagram comparing the average content of compounds in young (olive, Y) and mature (red, M) wines.

Figure 4.

Nightingale diagram comparing the average content of compounds in young (olive, Y) and mature (red, M) wines.

As illustrated in the diagram of average content of young (n=9) and aged (n=9) wines, almost all of the compounds identified by NMR increase during aging in oak barrels. In agreement with the literature, higher alcohols and organic acids increase during aging, primarily due to microbial activity such as malolactic fermentation, which converts malic acid into lactic acid, as well as chemical oxidative reactions and various chemical interactions. Contrary to some studies [

21], amino acids also increase during aging, which can be attributed to biochemical processes, particularly yeast autolysis [

25], especially when wines are aged on their lees (the sediment of dead yeast cells). The increase in sugar quantity may result from reactions with hemicellulose from oak barrels. The only compounds that show a decrease in quantity—caftaric acid and acetaldehyde—decline during aging primarily due to oxidation, microbial metabolism, or/and potential interactions with other wine components. A detailed comparison of each wine variety is needed, as the compounds in them can evolve differently during aging.

3.2. Differentiation of Young Wines by Grape Variety and Identification of the Changes in Their Profile During Aging Process

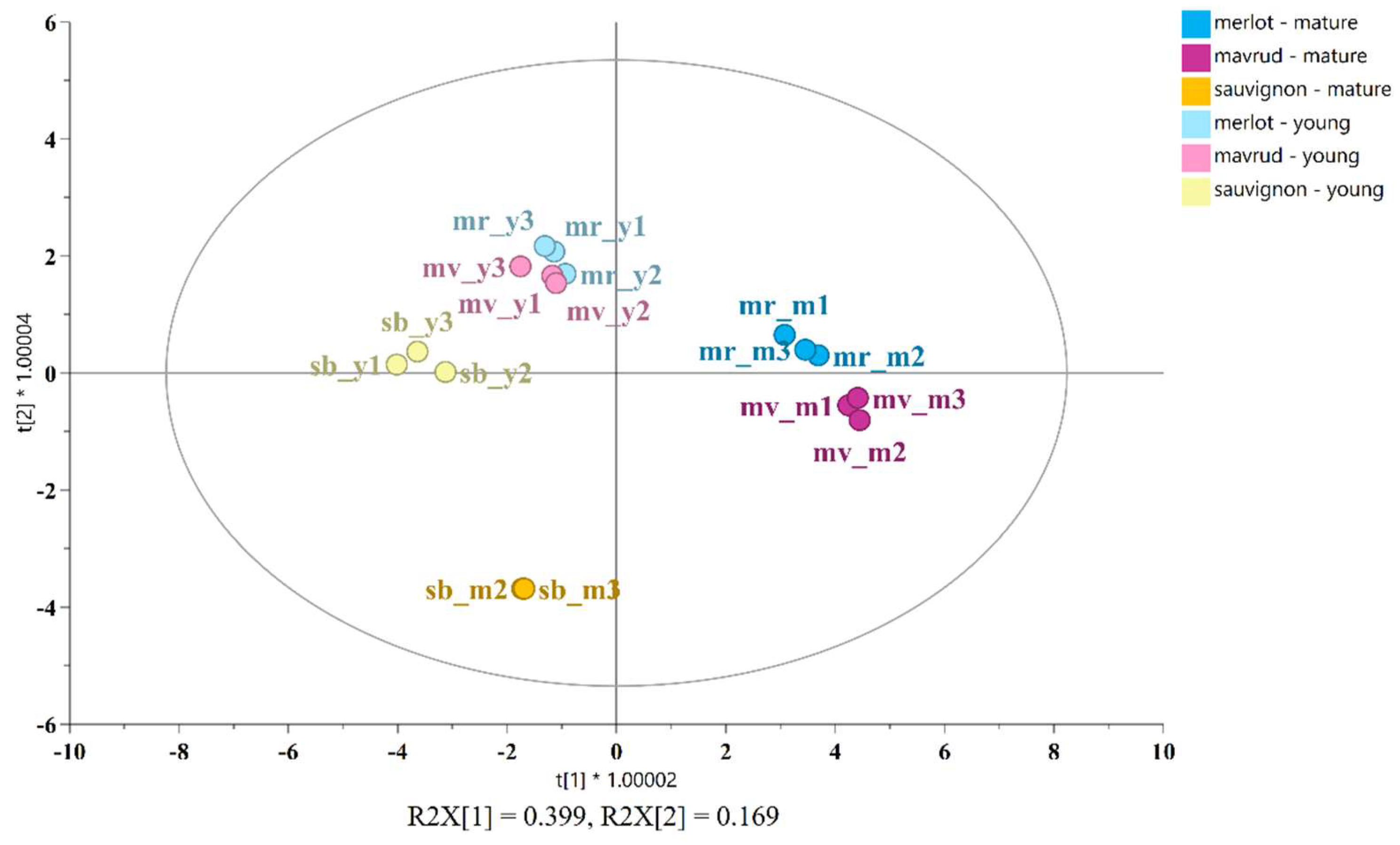

An OPLS-DA analysis was employed to distinguish between the young and aged wines based on their respective grape varieties. The 18 samples were classified into six groups: young and mature Merlot, young and mature Mavrud, and young and mature Sauvignon blanc. A total of 22 compounds with VIP scores exceeding 0.9 were incorporated into the OPLS-DA model. The principal discriminating compounds included seven alcohols (2,3-butanediol, glycerol, isobutanol, isopentanol, myo-inositol, 1-propanol, 2-phenylethanol), six organic acids (galacturonic, citric, lactic, malic, shikimic, succinic), three amino acids (alanine, proline, tyrosine), four sugars (arabinose, fructose, galactose, glucose), coutaric acid and acetoin. The OPLS-DA score plot is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

OPLS-DA score plot illustrating the differentiation of young and aged Merlot (light blue and blue), Mavrud (pink and red violet) and Sauvignon blanc (yellow and orange) wines.

Figure 5.

OPLS-DA score plot illustrating the differentiation of young and aged Merlot (light blue and blue), Mavrud (pink and red violet) and Sauvignon blanc (yellow and orange) wines.

Figure 5 provides a clear illustration of the discrimination between the six classes, emphasizing the compositional variations among the wines. The wines retain their principal characteristic profiles, exhibiting characteristic changes between varieties and different changes between young and mature wines. For example, the young Merlot is distinguished by elevated levels of 2-phenylethanol and tyrosine, the young Mavrud variety contains higher levels of succinic acid, while young Sauvignon blanc is distinguished by higher concentrations of malic acid and fructose. In comparison, mature Merlot is characterized by the presence of lactic and coutaric acid, as well as arabinose. Mavrud, on the other hand, exhibits elevated levels of galacturonic and shikimic acids, along with galactose. Aged Sauvignon blanc displays a higher concentration of 1-propanol, citric acid and malic acid [

16]. The corresponding contribution plots in

Figure S2 illustrate the detailed differences between young and mature wines. This comparison suggests that the major characteristic profile of each wine variety is largely preserved throughout the aging process, despite the changes that occur during ageing.

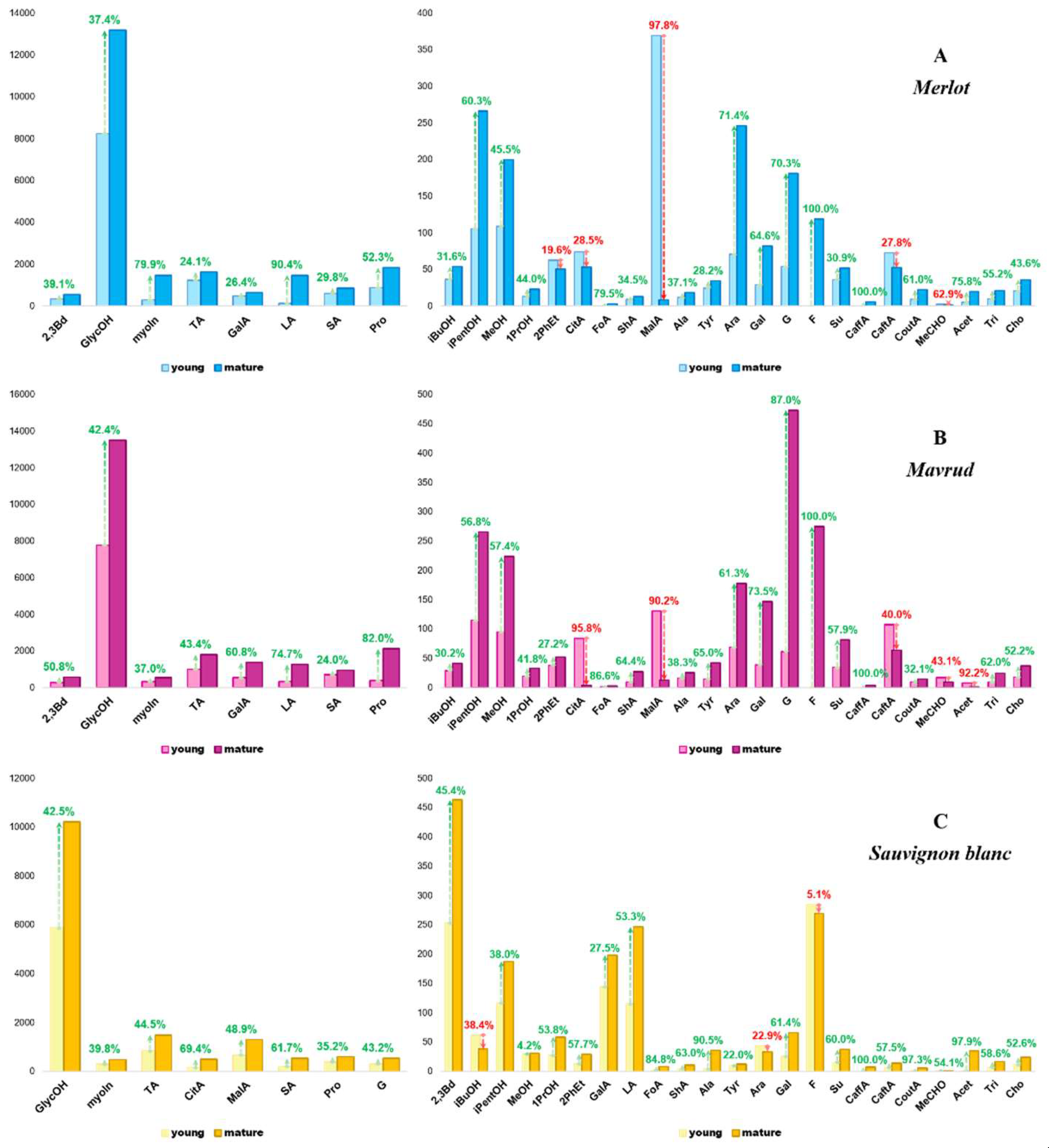

The score plot also demonstrate that the young red wines (Merlot and Mavrud) are closely grouped, as are the mature red wines, indicating comparable compositions and ageing patterns. Conversely, the aged Sauvignon blanc wines are more distant from their younger counterparts, suggesting that white wines undergo a different aging process to red wines. The compositional alterations for each wine variety during the aging process are illustrated in the charts in Figure 6, which compare the concentration differences of the measured components in young and mature wines. For improved visual representation, the components have been divided into two categories: major (≥480 mg/L) and minor (<480 mg/L).

Figure 6.

Concentration changes in Merlot (A), Mavrud (B), and Sauvignon blanc (C) during the aging process from young to mature wine, represented as major (left, ≥480 mg/L) and minor (right, <480 mg/L) groups. Positive changes are indicated in green, while negative changes - in red.

Figure 6.

Concentration changes in Merlot (A), Mavrud (B), and Sauvignon blanc (C) during the aging process from young to mature wine, represented as major (left, ≥480 mg/L) and minor (right, <480 mg/L) groups. Positive changes are indicated in green, while negative changes - in red.

As illustrated in the graphs, the minor and major components in the red wines (Merlot and Mavrud) exhibit notable similarities, yet they diverge significantly from those observed in Sauvignon blanc. Notable differences in the rate of change for specific major substances are evident in the red wines, such as myo-inositol, which exhibits an increase of nearly 80% in Merlot, but only 37% in Mavrud. The concentrations of tartaric acid, galacturonic acid, and proline in Mavrud wines are approximately twice those observed in Merlot wines. The minor compounds in the red wines exhibit slight variations, with significant differences observed in only a few of them, such as 2-phenylethanol and acetoin. In Mavrud, the concentration of 2-phenylethanol increases with age, whereas that of acetoin decreases. In contrast, aged Merlot exhibits elevated acetoin levels relative to the younger wine, accompanied by a decline in 2-phenylethanol. This differs from the findings reported in the literature on other wine types, where some authors have observed increases in both 2-phenylethanol and acetoin, while others have noted declines in acetoin concentration [

26]. It is likely that these differences are attributable to the grape variety used for wine production. The observed changes in red wines are likely due to a combination of biochemical transformations, including oxidation, ester formation, adsorption to wood during barrel aging, and environmental factors. The aging process of Sauvignon blanc has been observed to result in notable decreases in the concentration of certain sugars (arabinose and fructose) and isobutanol. These changes are likely driven by microbial activity, oxidation processes and the formation of esters. Given the distinct aging patterns observed in Sauvignon blanc, it is important to explore how the fermentation profiles of this variety vary not only with aging, but also among different products.

3.3. Fermentation products of Sauvignon blanc - comparison of grape ales vs. young and mature wines

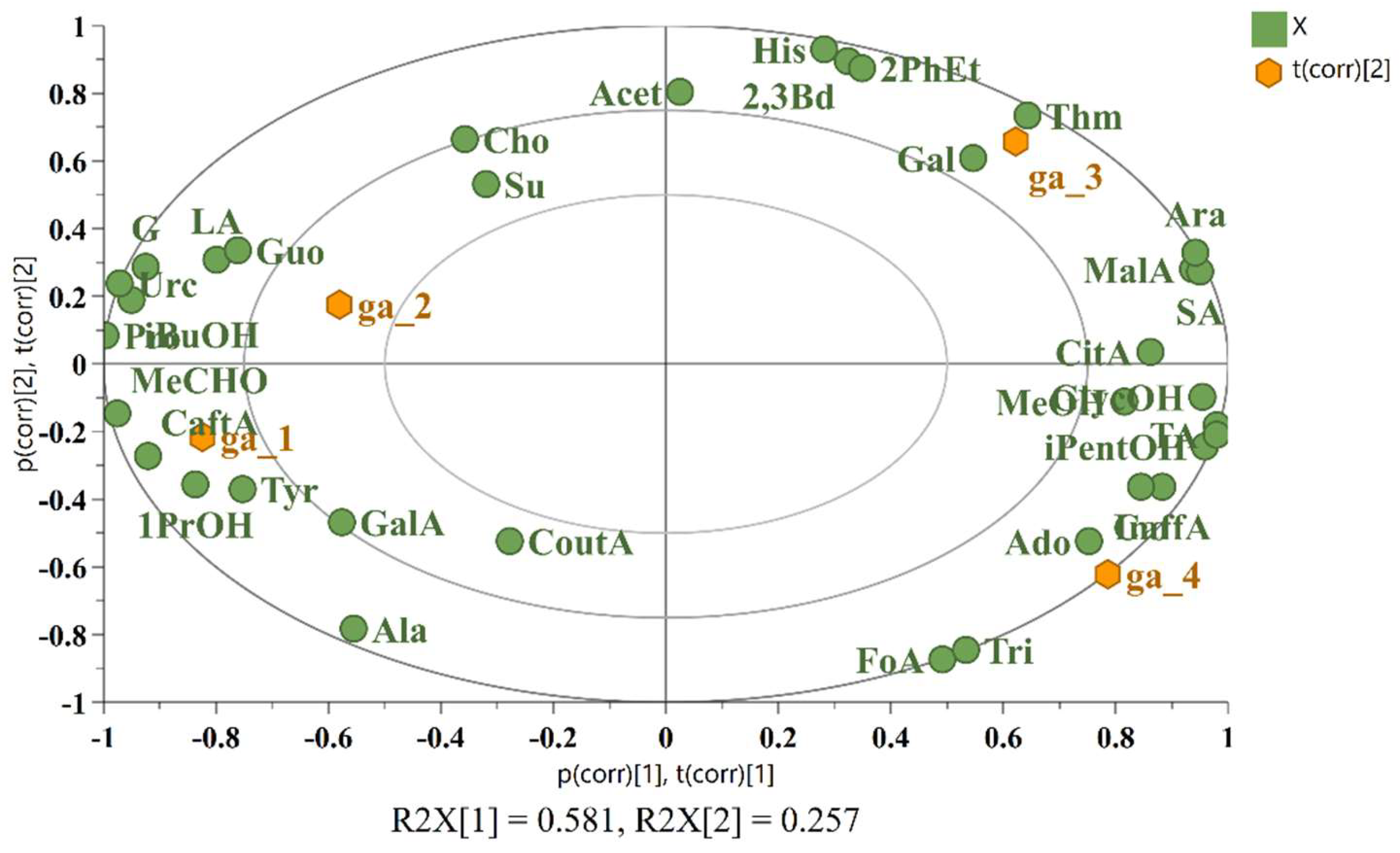

To date, no studies have been published that directly compare grape ales and wines, particularly in terms of the impact of grape variety or the effects of aging. In order to evaluate the influence of grape variety on the composition of grape ales and to assess similarities between these products, a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted. The analysis included quantitative data on 35 components from four samples: one grape ale (ga_1, producer Monyo) made from the red grape variety Kékfrankos, and three grape ales (ga_2, producer Monyo; ga_3, producer Kykao; ga_4, producer Kykao) made from white grape varieties – Sauvignon blanc, Malagouzia and Muscat, respectively. The PCA biplot, which illustrates both the score plot and the loading plot and thus the characteristic components for each grape ale, is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

PCA biplot illustrating the differentiation of four grape ales based on their characteristic components.

Figure 7.

PCA biplot illustrating the differentiation of four grape ales based on their characteristic components.

The PCA plot illustrates the presence of two distinct groups. The first comprises ga_1 (Kékfrankos) and ga_2 (Sauvignon blanc), while the second includes ga_3 (Malagouzia) and ga_4 (Muscat). This clustering indicates that the color of the grape variety utilized in the production of grape ale, in contrast to wine, exerts a comparatively lesser influence on the composition than the brewery. The first group (ga_1 and ga_2) is distinguished by elevated concentrations of iso-butanol, 1-propanol, galacturonic acid, lactic acid, tyrosine, glucose, caftaric acid, acetaldehyde, uracil and guanosine. In contrast, the second group (ga_3 and ga_4) is characterized by higher concentrations of glycerol, isopentanol, methanol, citric acid, malic acid, succinic acid, arabinose, caffeic acid and adenosine. The distinct chemical profiles observed between the two groups are likely to be influenced by several factors, including the fermentation techniques employed, the yeast selection used, the characteristics of the grape variety and the potential for aging.

A further comparison was conducted between the Sauvignon blanc grape ale (ga_2) and both young and mature Sauvignon blanc wines, with the objective of evaluating the similarities between them. Although the principal component analysis did not provide a clear distinction between the samples, the orthogonal projections to latent structures discriminant analysis was performed, including data from all 37 components, with two classes: young wine and mature wine. The misclassification table shown in Table 2 indicates that the grape ale was correctly identified as a mature wine, in accordance with the product label, which specified that the grape ale had undergone barrel aging. The probable cause of this classification is the closer concentrations of key compounds, including 2-phenylethanol, lactic acid, alanine, proline, tyrosine, arabinose, fructose, glucose, succinate, coutaric acid, and acetaldehyde, in the grape ale and the mature Sauvignon blanc.

Table 2.

Misclassification table for the prediction of grape ale ga_2 from data for Sauvignon blanc wines.

Table 2.

Misclassification table for the prediction of grape ale ga_2 from data for Sauvignon blanc wines.

| |

Members |

Correct |

Young |

Mature |

No class (Pred) |

| Young |

3 |

100% |

3 |

0 |

0 |

| Mature |

3 |

100% |

0 |

3 |

0 |

| No class |

1 |

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

| Total |

7 |

100% |

3 |

4 |

0 |

Given the limited sample size, the findings on grape ales should be regarded as preliminary and the necessity for further studies to corroborate these observations is evident.