Submitted:

19 March 2024

Posted:

21 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

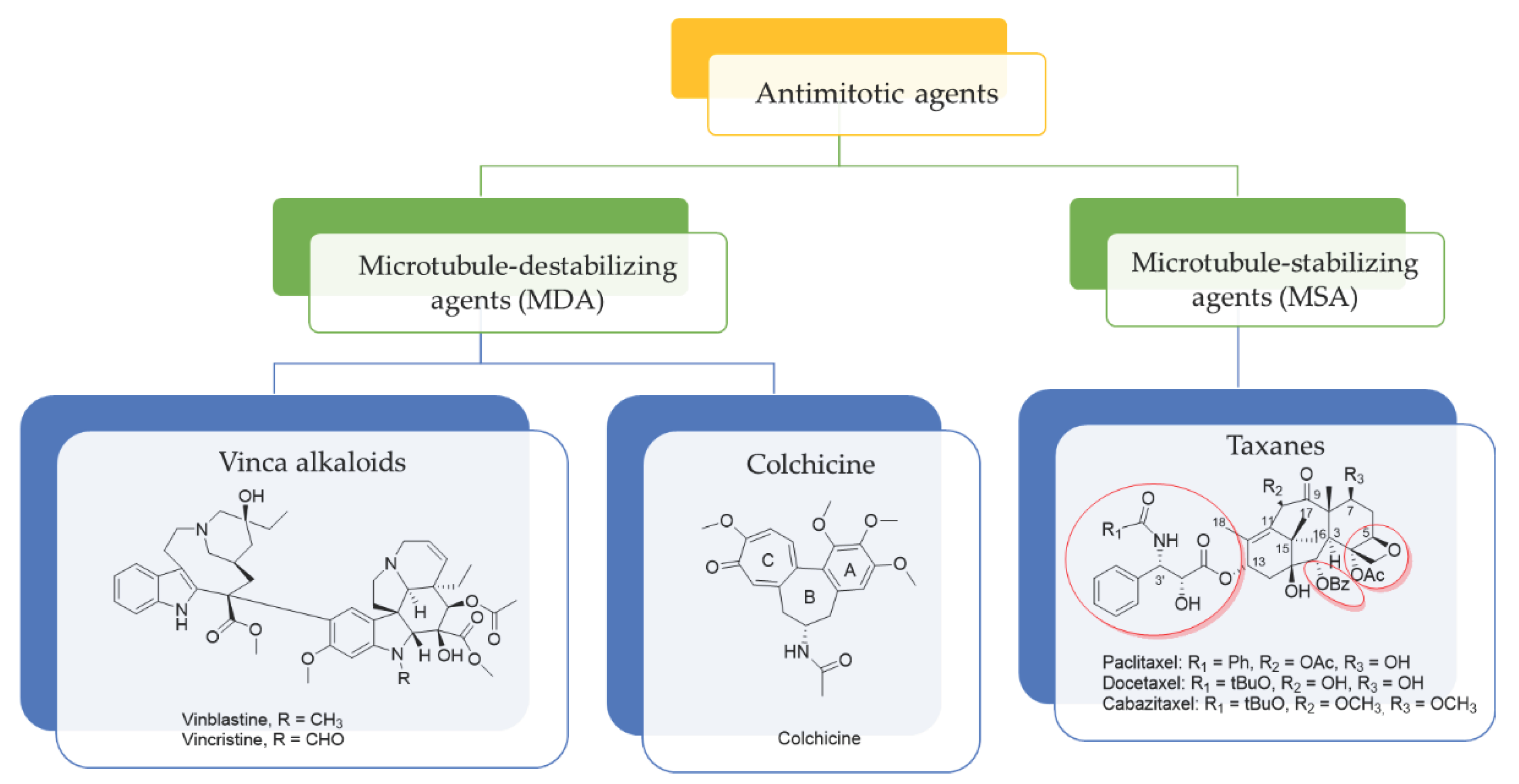

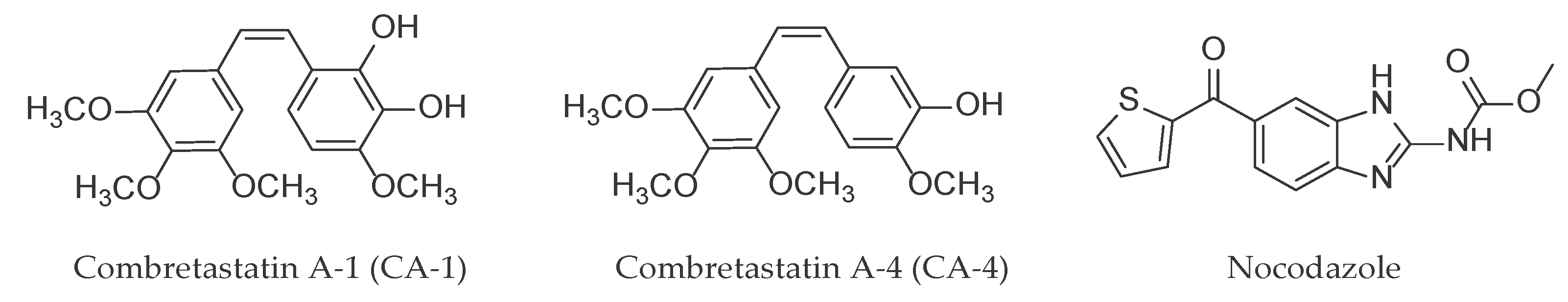

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

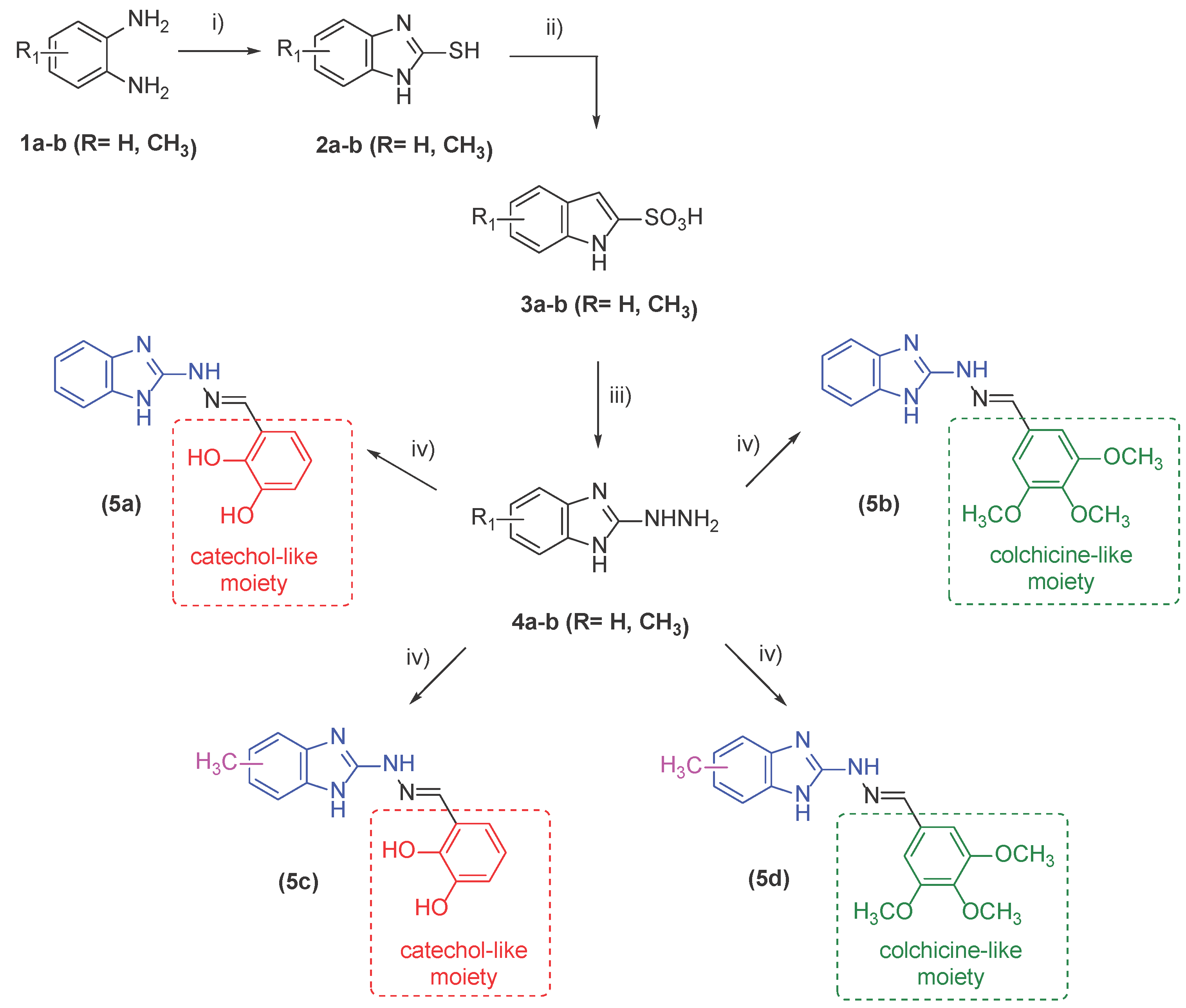

2.1. Synthesis of Target Compounds

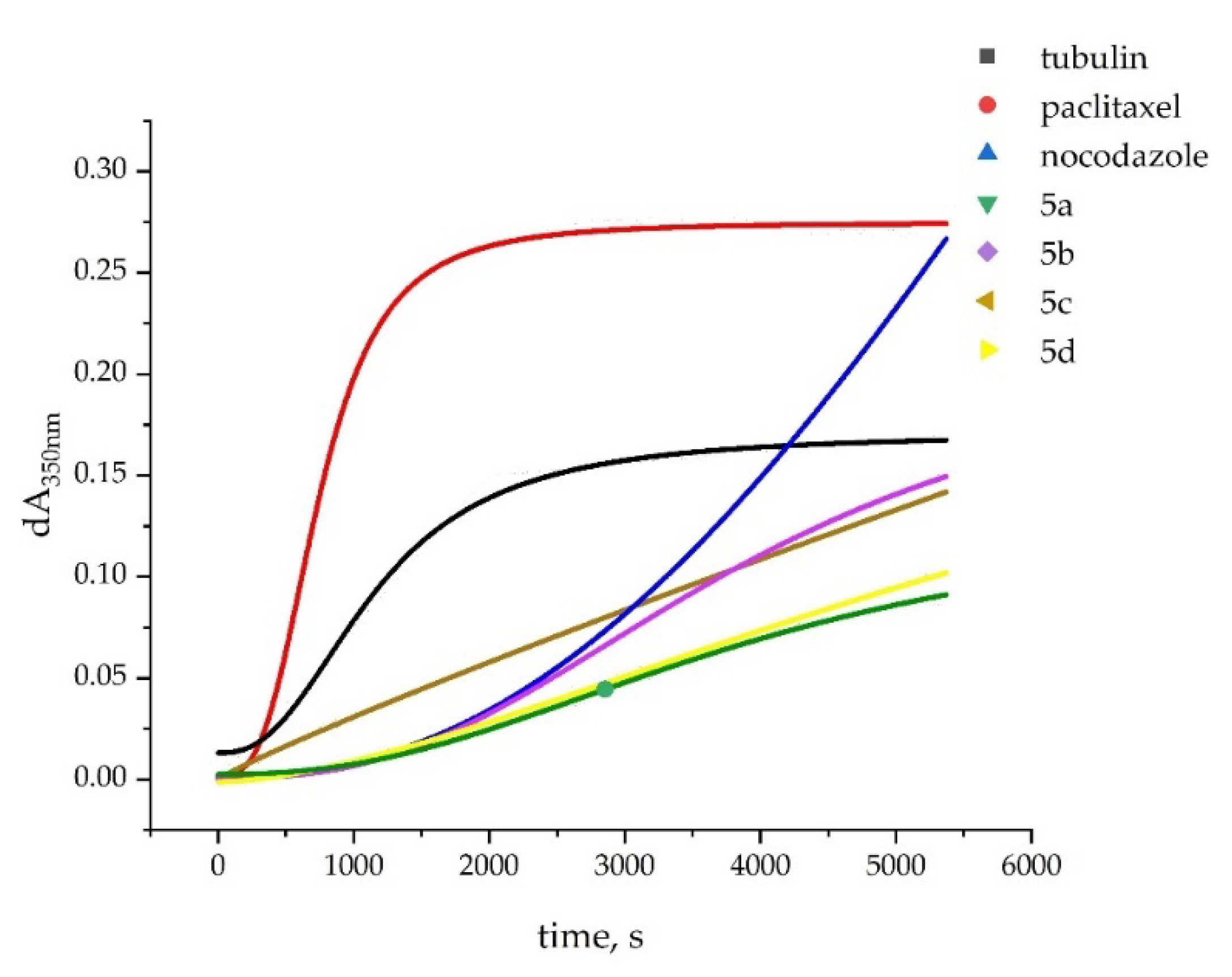

2.2. In Vitro Effect on Tubulin Polymerization and Docking Study on the Tubulin-Ligands Interactions

2.3. Determining Cell Viability by MTT Assay

2.4. Investigation of Microtubule Organization and Nuclear Morphology

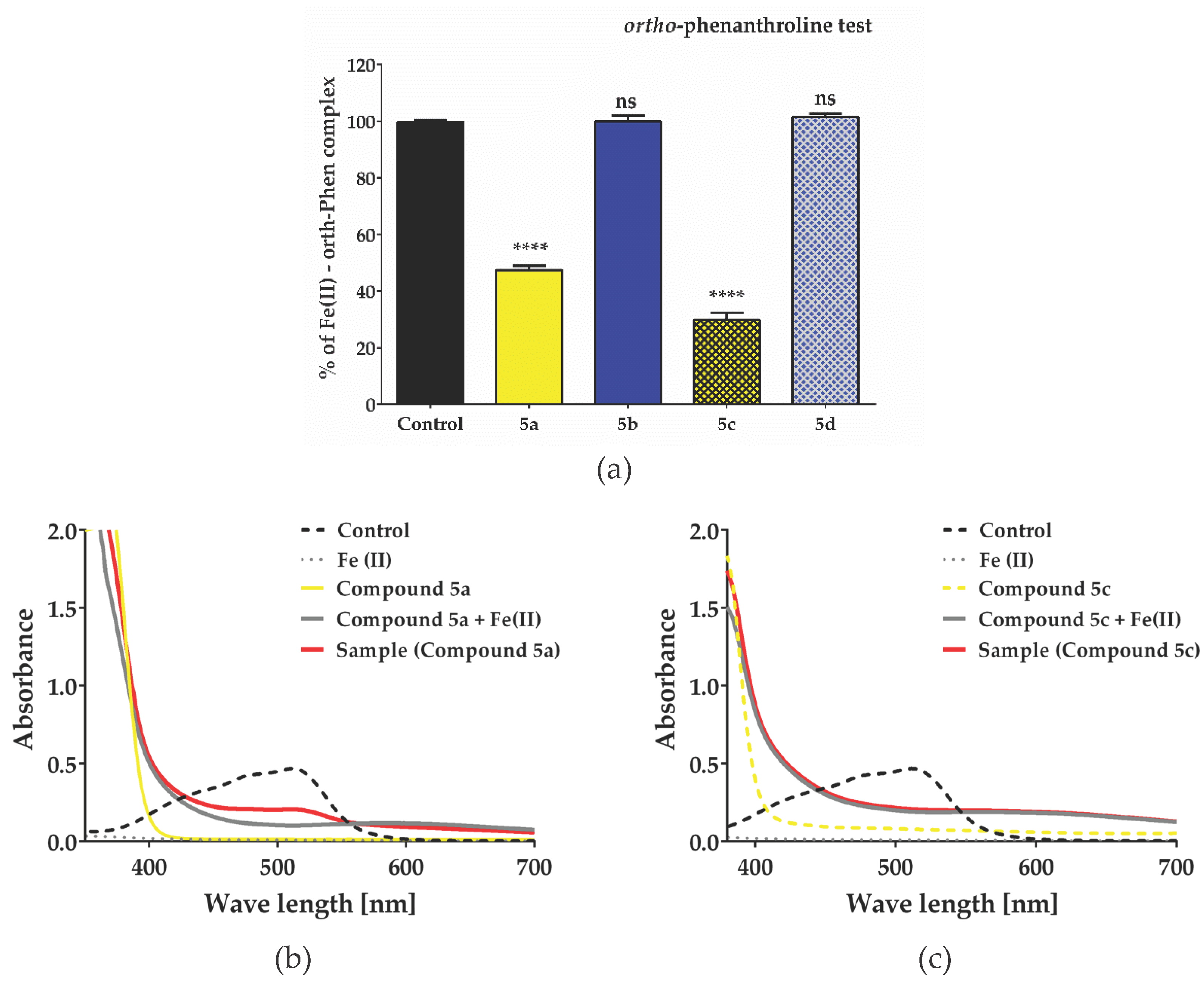

2.5. Evaluation of antioxidant Activity – Radical Scavenging Properties/Anti-Radical Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Materials

3.2. Synthesis

3.3. In Vitro Tubulin Polymerization Assay

3.4. Cell Lines

3.5. Cell Viability Assay

3.6. Immunofluorescence

3.7. Hypochlorite Scavenging Activity

3.8. Hydrogen Peroxide Scavenging Activity

3.9. Ortho-Phenanthroline Test

3.10. Molecular Docking

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McKean, P.G.; Vaughan, S.; Gull,K. The extended tubulin superfamily. J Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiring, J. C. M.; Shneyer,B. I.; Akhmanova,A. Generation and regulation of microtubule network asymmetry to drive cell polarity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 2020, 62, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, F.; Budman, D.R. Review: tubulin function, action of antitubulin drugs, and new drug development. Cancer Invest. 2005, 23, 264–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlan, K.; Gelfand, V. I. Microtubule-Based Transport and the Distribution, Tethering, and Organization of Organelles. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, 025817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline-Smith S., L.; Walczak, C. E. Mitotic Spindle Assembly and Chromosome Segregation: Refocusing on Microtubule Dynamics. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, K.L. ; PPARgamma Inhibitors as Novel Tubulin-Targeting Agents. PPAR Res. 2008, 2008, 785405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, E.; Adhami, V.M.; Mukhtar, H. Targeting microtubules by natural agents for cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 275–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avendaño,C.; Carlos Menéndez, J. Anticancer Drugs Targeting Tubulin and Microtubules. In Medicinal Chemistry of Anticancer Drugs, 2nd ed.; Avendaño,C.; Carlos Menéndez, J., Eds; Elsevier, 2015, pp 359-390.

- Rowinsky, E.; Donehower, R. Antimicrotubule agents. In DeVita VT, 5th ed, Hellmann, S.; Rosenberg, S.A., Ed.; Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Martin,R. J.; Robertson, A.P.; Bjorn, H. Target sites of anthelmintics. Parasitology 1997, 114, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, D. G. I. In Anticancer Agents from Natural Products; 2nd ed.; Cragg, G. M.; Kingston, D. G. I.; Newman, D. J. Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2005.

- Steinmetz, M. O.; Prota, A. E. Microtubule-Targeting Agents: Strategies to Hijack the Cytoskeleton. Trends in Cell Biology 2018, 28, 776–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Xiao, M.; Li, W.; Miller, D.D. An overview of tubulin inhibitors that interact with the colchicine binding site. Pharm Res. 2012, 29, 2943–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Bossche, H.; Rochette, F.; Hörig, C. Advances in Pharmacology and Chemotherapy; Academic Press: New York, 1982; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari, S.N.A.; Kumar, G.B.; Revankar, H.M.; Qin, H.-L. Development of combretastatins as potent tubulin polymerization inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2017, 72, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uckun, F. M.; Cogle, C. R.; Lin, T. L.; Qazi, S.; Trieu, V. N.; Schiller, G.; Watts, J. M. A Phase 1B Clinical Study of Combretastatin A1 Diphosphate (OXi4503) and Cytarabine (ARA-C) in Combination (OXA) for Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2020, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham, R.; Ky, B.; Tewari, K.S.; Chaplin, D.J.; Walker, J. Clinical trial experience with CA4P anticancer therapy: focus on efficacy, cardiovascular adverse events, and hypertension management. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2018, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blay, J.Y.; Pápai, Z.; Tolcher, A.W.; Italiano, A.; Cupissol, D.; López-Pousa, A.; Chawla, S.P.; Bompas, E.; Babovic, N.; Penel, N.; Isambert, N.; Staddon, A.P.; Saâda-Bouzid, E.; Santoro, A.; Franke, F.A.; Cohen, P.; Le-Guennec, S.; Demetri, G.D. Ombrabulin plus cisplatin versus placebo plus cisplatin in patients with advanced soft-tissue sarcomas after failure of anthracycline and ifosfamide chemotherapy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 531–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Husain, A.; Siddiqui, A. A.; Mishra, R. Benzimidazole clubbed with triazolo-thiadiazoles and triazolo-thiadiazines: New anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 62, 785–798. [Google Scholar]

- Tahlan, S.; Kumar, S.; Kakkar, S.; Narasimhan, B. Benzimidazole scaffolds as promising antiproliferative agents: a review. BMC Chem. 2019, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Reddy, T. S.; Vishnuvardhan, M.V.P.S.; Nimbarte, V. D.; Subba Rao, A.V.; Srinivasulu, V.; Shankaraiah, N. Synthesis of 2-aryl-1,2,4-oxadiazolo-benzimidazoles: Tubulin polymerization inhibitors and apoptosis inducing agents, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 23, 4608–4623. 23.

- Miao, T.T.; Tao, X.B.; Li, D.D.; Chen, H.; Jin, X.Y.; Geng, Y.; Wang, S.F.; Gu, W. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-aryl-benzimidazole derivatives of dehydroabietic acid as novel tubulin polymerization inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 17511–17526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricart, A.D.; Ashton, E.A.; Cooney, M.M. A phase I study of MN-029 (denibulin), a novel vascular-disrupting agent, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2011, 68, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Roche, N.M.; Mühlethaler, T.; Di Martino, R.M.C; Ortega, J.A.; Gioia, D.; Royd, B.; Prota, A.E.; Steinmetz, M.O.; Cavalli, A. Novel fragment-derived colchicine-site binders as microtubule-destabilizing agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 241, 114614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, L. C.; Espinosa-Mendoza, J. D.; Matadamas-Martínez, F.; Romero-Velásquez, A.; Flores-Ramos, M.; Colorado-Pablo, L. F.; Cerbón-Cervantes, M. A.; Castillo, R.; González-Sánchez, I.; Yépez-Mulia, L.; Hernández-Campos, A.; Aguayo-Ortiz, R. Structure-Based Optimization of Carbendazim-Derived Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors through Alchemical Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 7228–7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anichina, K.; Argirova, M.; Tzoneva, R.; Uzunova, V.; Mavrova, A.; Vuchev, D.; Popova-Daskalova, G.; Fratev, F.; Guncheva, M.; Yancheva, D. 1H-benzimidazole-2-yl hydrazones as tubulin-targeting agents: Synthesis, structural characterization, an-thelmintic activity and antiproliferative activity against MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells and molecular docking studies. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 345, 109540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argirova, M.A.; Georgieva, M.K.; Hristova-Avakumova, N.G.; Vuchev, D.I.; Popova-Daskalova, G.V.; Anichina, K.K.; Yancheva, D.Y. New 1H-benzimidazole-2-yl hydrazones with combined antiparasitic and antioxidant activity. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 39848–39868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argirova, M.; Guncheva, M.; Momekov, G.; Cherneva, E.; Mihaylova, R.; Rangelov, M.; Todorova, N.; Denev, P.; Anichina, K.; Mavrova, A.; Yancheva, D. Modulation Effect on Tubulin Polymerization, Cytotoxicity and Antioxidant Activity of 1H-Benzimidazole-2-Yl Hydrazones. Molecules 2023, 28, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molecular operating environment (MOE) 2020 Chemical Computing Group Inc., 1010 Sherbooke St. West, Suite #910, Mon-treal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7.

- Gigant, B.; Wang, C.; Ravelli, R.B.G.; Roussi, F.; Steinmetz, M.O.; Curmi, P.A.; Sobel, A.; Knossow, M. Structural basis for the regulation of tubulin by vinblastine. Nature 2005, 435, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knossow, M.; Campanacci, V.; Khodja, L. A.; Gigant, B. The Mechanism of Tubulin Assembly into Microtubules: Insights from Structural Studies, iScience, 2020, 23, 101511.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gigant, B.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Lai, Q.; Yang, Zh.; Chen, Q.; Yang, J. Structures of a diverse set of colchicine binding site inhibitors in complex with tubulin provide a rationale for drug discovery, FEBS Journal. 2016, 283, 102–111.

- Blajeski, A.L.; Phan, V.A.; Kottke, T.J.; Kaufmann, S.H. G(1) and G(2) cell-cycle arrest following microtubule depolymerization in human breast cancer cells. J Clin Invest. 2002, 110, 91–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryaskova, R.; Georgiev, N.; Philipova, N.; Bakov, V.; Anichina, K. Argirova, M.; Apostolova, S.; Georgieva, I.; Tzoneva, R. Novel Fluorescent Benzimidazole- Hydrazone-Loaded Micellar Carriers for Controlled Release: Impact on Cell Toxicity, Nuclear and Microtubule Alterations in Breast Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, E. T.; Day, B. W.; Rosenkranz, H. S. Direct tubulin polymerization perturbation contributes significantly to the induction of micronuclei in vivo. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1996, 350, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies M., J.; Hawkins, C. L. The Role of Myeloperoxidase in Biomolecule Modification, Chronic Inflammation, and Disease. Antiox. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 957–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J. Myeloperoxidase-derived oxidation: Mechanisms of biological damage and its prevention. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2010, 48, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, D.R.; García, M.V. Canle, M.; Santaballa, J.A.; Furtmüller, P.G.; Obinger, C. Myeloperoxidase-catalyzed chlorination: The quest for the active species. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008, 102, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Ren, H.; Lv. X.; Zhao. Y.; Yu, B.; He, Y.; Ma, Y.; Niu, C.; Kong, J.; Yu, F.; Sun, W.B.; Zhang, Y.; Willard, B.; Zheng, L. Hypochlorite-induced oxidative stress elevates the capability of HDL in promoting breast cancer metastasis. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 30, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doskey, C.M.; Buranasudja, V.; Wagner, B.A.; Wilkes, J.G.; Du, J.; Cullen, J.J.; Buettner, G.R. Tumor cells have decreased ability to metabolize H2O2: Implications for pharmacological ascorbate in cancer therapy. Redox. Biol. 2016, 10, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lázaro, M. Dual role of hydrogen peroxide in cancer: possible relevance to cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Cancer Lett. 2007, 252, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S. J.; Klein, R.; Slivka, A.; Wei, M. Chlorination of taurine by human neutrophils. Evidence for hypochlorous acid generation. J. Clin. Invest. 1982, 70, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, D.; Dasgupta, P.; Sinha Roy, D.; Palchoudhuri, S.; Chatterjee, I.; Ali, S.; Dastidar, S. G. A Sensitive In vitro Spectrophotometric Hydrogen Peroxide Scavenging Assay using 1,10-Phenanthroline. Free Radicals and Antioxidants 2016, 6, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczenko, Z.; Balcerzak, M. In Separation, preconcentration, and spectrophotometry in inorganic analysis. 1st ed.; Kloczko, E., Eds.; Elsevier, 2000, 10, pp 3–521. [Google Scholar]

| Compound | Tubulin polymerization 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| lag time, sec. | initial rate 2 | |

| tubulin (spontaneous polymerization) | no lag phase | 75.3 |

| Unsubstituted benzimidazole ring | ||

| 5a 3 | 1461 | 13.4 |

| 5b 3 | 988 | 20.6 |

| 5(6)-Methyl benzimidazole ring | ||

| 5c | no lag phase | 27.0 |

| 5d | 600 | 12.9 |

| Reference compounds | ||

| Paclitaxel 3 | 151 | 167 |

| Nocodazole 3 | 935 | 52 |

| Compound | IC50 (µM) | |

|---|---|---|

| 48 h | 72 h | |

| Unsubstituted benzimidazole ring | ||

| 5a | 43.93 ± 9.3 | 16.04 ± 2.2 |

| 5b | 60.08 ± 15.3 | 20.30 ± 4.3 1 |

| 5(6)-Methyl benzimidazole ring | ||

| 5c | 47.28 ± 8.0 | 14.83 ± 3.8 |

| 5d | 40.3 ± 4.1 | 12.65 ± 2.5 |

| Reference compound | ||

| Nocodazole | 0.38 2 | |

| Compound | Characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitosis | Morphology | Tubulin | ||||

| Nucleus | Cell | |||||

| Unsubstituted benzimidazole ring | ||||||

| 5a | Until 6 h | Abnormal shape | Abnormal shape | Abnormal mitotic spindle | ||

| 5b | Until 24 h | Micronuclei | Not affected | Not directly observed | ||

| 5(6)-Methyl benzimidazole ring | ||||||

| 5c | Until 12 h | Not affected | Not affected | Elongated polar microtubules, cytoplasmic granules | ||

| 5d | Arrested in mitosis |

Abnormal shape | Abnormal shape | Cytoplasmic granules | ||

| Reference compound | ||||||

| Nocodazole | Arrested in mitosis 1 | Abnormal shape | Abnormal shape | Abnormal mitotic spindle | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).