Submitted:

20 March 2024

Posted:

20 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

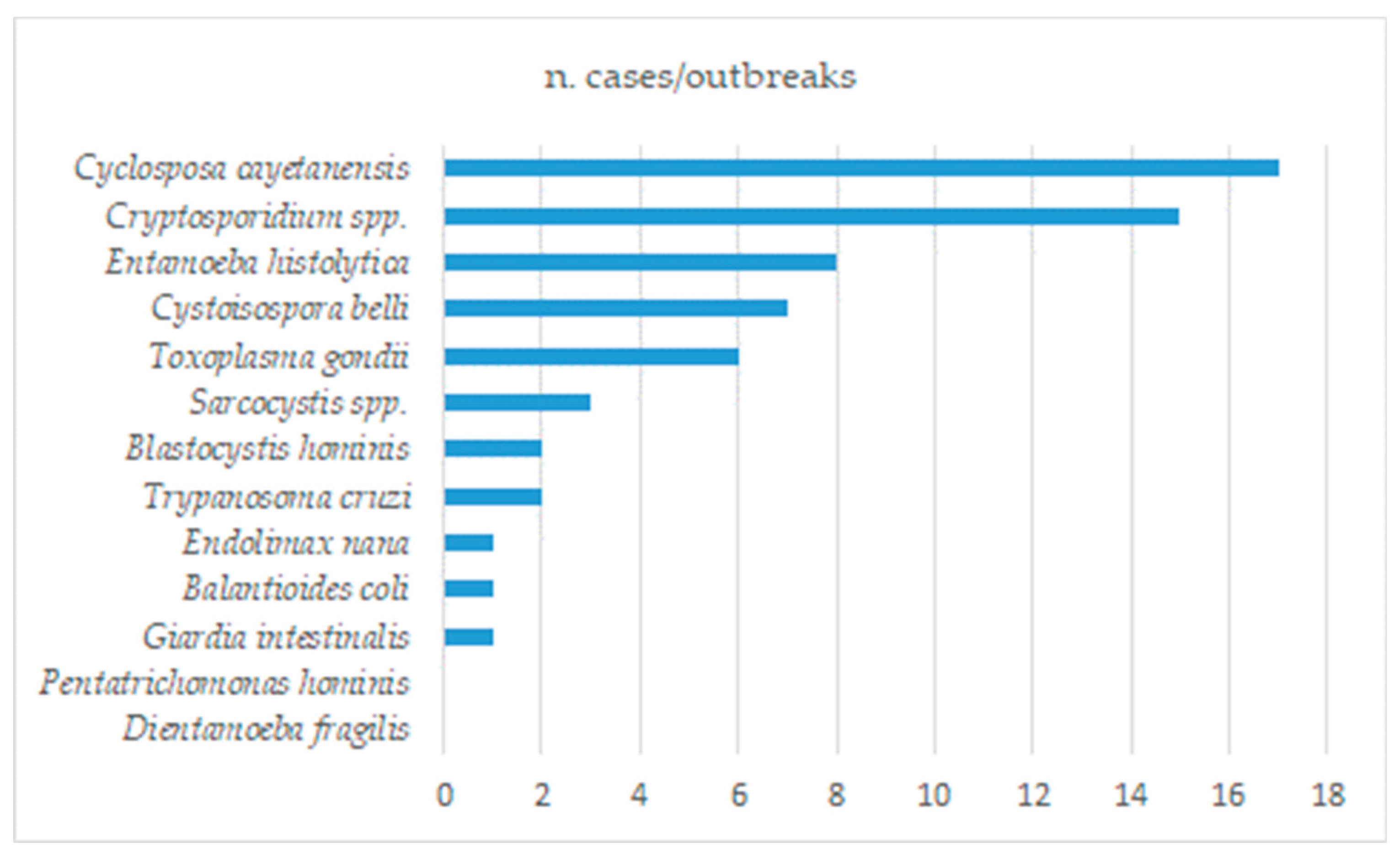

2. Waterborne and Foodborne Protozoan Infections

2.1. Parasitic Protozoans in the General Population

2.2. Parasitic Protozoans in Patients Immunocompromised or with Predisposing Conditions

2.3. Parasitic Protozoans in Food Handlers

2.4. Pathogenic Protozoans in Drinking Water

2.5. Pathogenic Protozoans in Raw Vegetables

3. Cryptosporidium spp.

3.1. Diseases Caused by Cryptosporidium spp.

3.2. Epidemiology of Cryptosporidiosis

3.3. Cryptosporidium spp. in Drinking Water

3.4. Cryptosporidium in Food

4. Entamoeba spp.

4.1. Diseases Caused by Entamoeba spp.

4.2. Epidemiology of Entamoeba spp.

4.3. Drinking Water Involvement in Entamoeba spp. Infections

5. Toxoplasma gondii

5.1. Diseases Caused by T. gondii

5.2. Epidemiology of T. gondii Infections and Involvement of Food and Drinking Water

5.3. Distribution of T. gondii in Food Producing Animals

6. Giardia Intestinalis

6.1. Diseases Caused by G. intestinalis

6.2. Epidemiology of Giardiasis

6.3. G. intestinalis Infections from Food and Drinking Water

7. Trypanosoma cruzi

7.1. Epidemiology and Symptoms of T. cruzi Infection

8. Cyclospora Cayetanensis

8.1. Diseases Caused by C. cayetanensis

8.2. Epidemiology of C. cayetanensis

8.3. Dietary Sources of C. cayetanensis

9. Balantioides coli

10. Cystoisospora belli

10.1. Diseases Caused by C. belli

10.2. Epidemiology of C. belli

10.3. Dietary Sources of C. belli

11. Sarcocystis

11.1. Diseases Caused by Sarcocystis spp.

11.2. Epidemiology of Sarcocystis spp.

11.3. Prevalence of Sarcocystis spp. in Food Producing Animals

12. Protozoan Parasites with a Poorly Defined Impact on Health

12.1. Blastocystis

12.2. Dientamoeba Fragilis

12.3. Endolimax Nana

12.4. Pentatrichomonas Hominis

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaeger, R.G. Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and of the Development. Chapter 77 in: Medical Microbiology. Editor: Samuel Baron. 4th edition. University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. 1996. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7627/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Taxonomy browser. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=2698737&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Baig, A.M.; Suo, X.; Liu, D. Chapter 148 - Pathogenesis of protozoan infections, Editor(s): Yi-Wei Tang, Musa Y. Hindiyeh, Dongyou Liu, Andrew Sails, Paul Spearman, Jing-Ren Zhang, Molecular Medical Microbiology (Third Edition), Academic Press, 2024, Pages 2921-2940.

- Pignata, C.; Bonetta, S.; Bonetta, S.; Cacciò, S.M.; Sannella, A.R.; Gilli, G.; Carraro, E. Cryptosporidium Oocyst Contamination in Drinking Water: A Case Study in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chique, C.; Hynds, P.D.; Andrade, L.; Burke, L.; Morris, D.; Ryan, M.P.; O’Dwyer, J. Cryptosporidium Spp. in Groundwater Supplies Intended for Human Consumption - A Descriptive Review of Global Prevalence, Risk Factors and Knowledge Gaps. Water Res. 2020, 176, 115726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjilouka, A.; Tsaltas, D. Cyclospora Cayetanensis-Major Outbreaks from Ready to Eat Fresh Fruits and Vegetables. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharmaratnam, T.; Kumanan, T.; Iskandar, M.A.; D’Urzo, K.; Gopee-Ramanan, P.; Loganathan, M.; Tabobondung, T.; Tabobondung, T.A.; Sivagurunathan, S.; Patel, M.; Tobbia, I. Entamoeba Histolytica and Amoebic Liver Abscess in Northern Sri Lanka: A Public Health Problem. Trop. Med. Health 2020, 48, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, B.M. Zoonotic Sarcocystis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021, 136, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.; Razakandrainibe, R.; Basmaciyan, L.; Raibaut, J.; Delaunay, P.; Morio, F.; Gargala, G.; Villier, V.; Mouhajir, A.; Levy, B.; Rieder, C.; Larreche, S.; Lesthelle, S.; Coron, N.; Menu, E.; Demar, M.; de Santi, V.P.; Blanc, V.; Valot, S.; Dalle, F.; Favennec, L. A Summary of Cryptosporidiosis Outbreaks Reported in France and Overseas Departments, 2017-2020. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2022, 27, e00160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmy, Y.A.; Hafez, H.M. Cryptosporidiosis: From Prevention to Treatment, a Narrative review. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, A.; Gilabert, J.A. Oral Transmission of Chagas Disease from a One Health Approach: A Systematic Review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2023, 28, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Escolano, R.; Ng, G.C.; Tan, K.S.W.; Stensvold, C.R.; Gentekaki, E.; Tsaousis, A.D. Resistance of Blastocystis to Chlorine and Hydrogen Peroxide. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Ureña, N.M.; Chaudhry, U.; Calero Bernal, R.; Cano Alsua, S.; Messina, D.; Evangelista, F.; Betson, M.; Lalle, M.; Jokelainen, P.; Ortega Mora, L.M.; Álvarez García, G. Contamination of Soil, Water, Fresh Produce, and Bivalve Mollusks with Toxoplasma Gondii Oocysts: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwila, J.; Mwaba, F.; Chidumayo, N.; Mubanga, C. Food and Waterborne Protozoan Parasites: The African Perspective. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2020, 20, e00088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brožová, K.; Jirků, M.; Lhotská, Z.; Květoňová, D.; Kadlecová, O.; Stensvold, C.R.; Samaš, P.; Petrželková, K.J.; Jirků, K. The Opportunistic Protist, Giardia Intestinalis, Occurs in Gut-Healthy Humans in a High-Income Country. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2270077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Team Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Prevention and control of intestinal parasitic infections: WHO Technical Report Series N°749. Guideline. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-TRS-749 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Das, R.; Palit, P.; Haque, M.A.; Levine, M.M.; Kotloff, K.L.; Nasrin, D.; Hossain, M.J.; Sur, D.; Ahmed, T.; Breiman, R.F.; Freeman, M.C.; Faruque, A.S.G. Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Enteric Protozoan Parasitic Infection and Their Association with Subsequent Growth Parameters in under Five Children in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, T.L.; Medeiros de Carvalho Neto, A.; Da Silva Ferreira, J.R.; Azevedo, P.V.M.; Wallas Lins Da Silva, K.; Alencar dos Nascimento, C.M.; Calheiros, C.M.L.; Wanderley, F.S. G. Dos Santos Cavalcanti, M.; Alencar Do Nascimento Rocha, M.; Rocha, T.J.M. Frequency of Intestinal Protozoan Infections Diagnosed in Patients from a Clinical Analysis Laboratory. Biosci. J. 2022, 38, e38001. [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO. Multicriteria-Based Ranking for Risk Management of Food-Borne Parasites. Rome. 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112672 (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Iordanov, R.B.; Leining, L.M.; Wu, M.; Chan, G.; DiNardo, A.R.; Mejia, R. Case Report: Molecular Diagnosis of Cystoisospora Belli in a Severely Immunocompromised Patient with HIV and Kaposi Sarcoma. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 106, 678–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahittikorn, A.; Udonsom, R.; Koompapong, K.; Chiabchalard, R.; Sutthikornchai, C.; Sreepian, P.M.; Mori, H.; Popruk, S. Molecular Identification of Pentatrichomonas Hominis in Animals in Central and Western Thailand. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, M.; Katzman, P.J.; Huber, A.R.; Findeis-Hosey, J.J.; Whitney-Miller, C.; Gonzalez, R.S.; Zhou, Z.; N’kodia, H.D.; Skonick, K.; Abell, R.L.; Saubermann, L.J.; Lamps, L.W.; Drage, M.G. Unexpectedly High Prevalence of Cystoisospora Belli Infection in Acalculous Gallbladders of Immunocompetent Patients. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 151, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietilä, J.-P.; Meri, T.; Siikamäki, H.; Tyyni, E.; Kerttula, A.-M.; Pakarinen, L.; Jokiranta, T.S.; Kantele, A. Dientamoeba Fragilis - the Most Common Intestinal Protozoan in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, Finland, 2007 to 2017. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popruk, S.; Adao, D.E.V.; Rivera, W.L. Epidemiology and Subtype Distribution of Blastocystis in Humans: A Review. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021, 95, 105085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matovelle, C.; Tejedor, M.T.; Monteagudo, L.V.; Beltrán, A.; Quílez, J. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Blastocystis Sp. Infection in Patients with Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Spain: A Case-Control Study. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobuccio, L.G.; Laurent, M.; Gardiol, C.; Wampfler, R.; Poppert, S.; Senn, N.; Eperon, G.; Genton, B.; Locatelli, I.; de Vallière, S. Should We Treat Blastocystis Sp.? A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Randomized Pilot Trial. J. Travel Med. 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Montoya, G.M.; Galvan-Diaz, A.L.; Alzate, J.F. Metataxomics Reveals Blastocystis Subtypes Mixed Infections in Colombian Children. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2023, 113, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshyar, H.; Arbabi, M.; Rostamkhani, P. Checklist of Endolimax Species Recognized in Human and Animals, a Review on a Neglected Intestinal Parasitic Amoeba. Iraq Med. J. 2023, 7, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzel, T.; Brown, A.; Libman, M.; Perret, C.; Huits, R.; Chen, L.; Leung, D.; Leder, K.; Connor, B.A.; Menéndez, M.D.; Asgeirsson, H.; Schwartz, E.; Salvador, F.; Malvy, D.; Saio, M.; Norman, F.F.; Amatya, B.; Duvingnaud, A.; Vaughan, S.; Glynn, M.; Angelo, K.M.; GeoSentinel Network. Intestinal protozoa in returning travellers: a GeoSentinel analysis from 2007 to 2019. J Travel Med. 2024 Jan 21:taae010.

- Salim, M.; Mohammad Shahid, M.; Shagufta, P. The Possible Involvement of Protozoans in Causing Cancer in Human. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci., Med. Entomol. Parasitol. 2022, 14, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yu, X.; Zhang, H.; Cui, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Gong, P.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X. Prevalence and Genotyping of Cryptosporidium Parvum in Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 3334–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certad, G. Is Cryptosporidium a Hijacker Able to Drive Cancer Cell Proliferation? Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2022, 27, e00153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrouch, S.; Escotte-Binet, S.; Harrak, R.; Huguenin, A.; Flori, P.; Favennec, L.; Villena, I.; Hafid, J. Detection Methods and Prevalence of Transmission Stages of Toxoplasma Gondii, Giardia Duodenalis and Cryptosporidium Spp. in Fresh Vegetables: A Review. Parasitology 2020, 147, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrouch, S.; Escotte-Binet, S.; Amraouza, Y.; Flori, P.; Aubert, D.; Villena, I.; Hafid, J. Cryptosporidium Spp., Giardia Duodenalis and Toxoplasma Gondii Detection in Fresh Vegetables Consumed in Marrakech, Morocco. Afr. Health Sci. 2020, 20, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, H.; Fortes, B.H.; Dilmaghani, S.; Ryan, S.M. 34-Year-Old Woman with Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Chronic Diarrhea. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 2474–2479. [Google Scholar]

- Özmen-Çapın, B.B.; Gürsoy, G.; Tortop, S.; Jabrayilov, J.; İnkaya, A.Ç.; Ergüven, S. Cystoisospora Belli Infection in a Renal Transplant Recipient: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzhanov, F.; Dogruman-Al, F.; Santin, M.; Maloney, J.G.; Gureser, A.S.; Karasartova, D.; Taylan-Ozkan, A. Investigation of Neglected Protists Blastocystis Sp. and Dientamoeba fragilis in Immunocompetent and Immunodeficient Diarrheal Patients Using Both Conventional and Molecular Methods. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlaam, A.; Sannella, A.R.; Ferrari, N.; Temesgen, T.T.; Rinaldi, L.; Normanno, G.; Cacciò, S.M.; Robertson, L.J.; Giangaspero, A. Ready-to-Eat Salads and Berry Fruits Purchased in Italy Contaminated by Cryptosporidium Spp., Giardia Duodenalis, and Entamoeba Histolytica. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 370, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfun, M.G.; Fuchs, A.; Holtfreter, M.C.; Tufa, T.B.; Orth, H.M.; Luedde, T.; Feldt, T. The Implementation of the Kinyoun Staining Technique in a Resource-Limited Setting Is Feasible and Reveals a High Prevalence of Intestinal Cryptosporidiosis in Patients with HIV. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 122, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bakri, A.; Hussein, N.M.; Ibrahim, Z.A.; Hasan, H.; AbuOdeh, R. Intestinal Parasite Detection in Assorted Vegetables in the United Arab Emirates. Oman Med. J. 2020, 35, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adhroey, A.H.; Mehrass, A.A.-K.O.; Al-Shammakh, A.A.; Ali, A.D.; Akabat, M.Y.M.; Al-Mekhlafi, H.M. Prevalence and Predictors of Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Pregnant Women from Dhamar, Yemen. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Paredes, C.; Villamil-Gómez, W.E.; Schultz, J.; Henao-Martínez, A.F.; Parra-Henao, G.; Rassi, A., Jr; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Suarez, J.A. A Deadly Feast: Elucidating the Burden of Orally Acquired Acute Chagas Disease in Latin America - Public Health and Travel Medicine Importance. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 36, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, F.; Shah, M.; Ali, A.; Ahmad, I.; Sarwar, M.T.; Rapisarda, A.M.C.; Cianci, A. Unpasteurised Milk Consumption as a Potential Risk Factor for Toxoplasmosis in Females with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papatsiros, V.G.; Athanasiou, L.V.; Kostoulas, P.; Giannakopoulos, A.; Tzika, E.; Billinis, C. Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Swine: Implications for Public Health. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2021, 18, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Frickmann, H.; Tannich, E.; Poppert, S.; Hagen, R.M. Colitis Caused by Entamoeba Histolytica Identified by Real-Time-PCR and Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization from Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissue. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. (Bp.) 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini, F.M.; Morselli, S.; Marangoni, A.; Taddei, R.; Maioli, G.; Roncarati, G.; Balboni, A.; Dondi, F.; Lunetta, F.; Galuppi, R. Spread of Toxoplasma Gondii among Animals and Humans in Northern Italy: A Retrospective Analysis in a One-Health Framework. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2023, 32, e00197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominic, C.; Kelly, S.; Melzer, M. Refractory Inflammatory Bowel Disease – Entamoeba Histolytica, the Forgotten Suspect. Clin. Infect. Pract. 2023, 20, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zhong, Q.; Gu, Y.-L.; Liang, N.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Cong, X.-M.; Liang, J.-Y.; Wang, X.-M. Is Toxoplasma Gondii Infection a Concern in Individuals with Rheumatic Diseases? Evidence from a Case-Control Study Based on Serological Diagnosis. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 182, 106257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesema, I.H.M.; Hofhuis, A.; Hoek-van Deursen, D.; Jansz, A.R.; Ott, A.; van Hellemond, J.J.; van der Giessen, J.; Kortbeek, L.M.; Opsteegh, M. Risk Factors for Acute Toxoplasmosis in the Netherlands. Epidemiol. Infect. 2023, 151, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaan, A.A.; Uzairue, L.I.; Alfaraj, A.H.; Halwani, M.A.; Muzaheed, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Alawfi, A.; Alshengeti, A.; Al Kaabi, N.A.; Alawad, E.; Alhajri, M.; Alwarthan, S.; Alshukairi, A.N.; Almuthree, S.A.; Alsubki, R.A.; Alshehri, N.N.; Alissa, M.; Albayat, H.; Zaidan, T.I.; Alagoul, H.; Fraij, A.A.; Alestad, J.H. Seroprevalence, Risk Factors and Maternal-Fetal Outcomes of Toxoplasma Gondii in Pregnant Women from WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sini, M.F.; Manconi, M.; Varcasia, A.; Massei, G.; Sandu, R.; Mehmood, N.; Ahmed, F.; Carta, C.; Cantacessi, C.; Scarano, C.; Scala, A.; Tamponi, C. Seroepidemiological and biomolecular survey on Toxoplasma gondii in Sardinian wild boar (Sus scrofa). Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2024, 34, e00222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusaro, H.; Rostamkhani, P.; Arbabi, M.; Delavari, M. Giardia Lamblia Infection: Review of Current Diagnostic Strategies. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2019, 12, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kyany’a, C.; Eyase, F.; Odundo, E.; Kipkirui, E.; Kipkemoi, N.; Kirera, R.; Philip, C.; Ndonye, J.; Kirui, M.; Ombogo, A.; Koech, M.; Bulimo, W.; Hulseberg, C.E. First Report of Entamoeba Moshkovskii in Human Stool Samples from Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Participants in Kenya. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2019, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantzanou, M.; Karalexi, M.A.; Vrioni, G.; Tsakris, A. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Children in Europe over the Last Five Years. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, E.; Goizueta, C.; Periago, M.V.; Muñoz-Antoli, C. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites and Molecular Characterization of Giardia Intestinalis, Blastocystis Spp. and Entamoeba Histolytica in the Village of Fortín Mbororé (Puerto Iguazú, Misiones, Argentina). Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegen, D.; Damtie, D.; Hailegebriel, T. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Human Intestinal Protozoan Parasitic Infections in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 2020, 8884064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhe, B.; Mardu, F.; Tesfay, K.; Legese, H.; Adhanom, G.; Haileslasie, H.; Gebremichail, G.; Tesfanchal, B.; Shishay, N.; Negash, H. More than Half Prevalence of Protozoan Parasitic Infections among Diarrheic Outpatients in Eastern Tigrai, Ethiopia, 2019; A Cross-Sectional Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilahun, Y.; Gebreananiya, T.A. Prevalence of human intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors at Lay Armachiho District Tikildingay town health center, Northwest Ethiopia. Research Square 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijjawi, N.; Zahedi, A.; Ryan, U. Molecular Characterization of Entamoeba, Blastocystis and Cryptosporidium Species in Stool Samples Collected from Jordanian Patients Suffering from Gastroenteritis. Trop. Parasitol. 2021, 11, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karim, A.; Zartashia, B.; Khwaja, S.; Akhter, A.; Raza, A.A.; Parveen, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Human Intestinal Parasitic Infections (IPIs) in Rural and Urban Areas of Quetta, Pakistan. Braz. J. Biol. 2023, 84, e266898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sultany, A.K.; Al-Morshidy, K.A.H. An Epidemiological Study of Intestinal Parasites in Children Attending the Pediatric Teaching Hospital in the Holy City of Karbala, Iraq. Medical Journal of Babylon 2023, 20, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Deksne, G.; Krūmiņš, A.; Mateusa, M.; Morozovs, V.; Šveisberga, D.P.; Korotinska, R.; Bormane, A.; Vīksna, L.; Krūmiņa, A. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. Infection in Humans in Latvia: Evidence of Underdiagnosed and Underreported Cases. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symmers, W.S.C. Opportunistic Infections: The Concept of ‘Opportunistic Infections. ’ Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1965, 58, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, Y.; Holland, T.; Spelman, L. Toxoplasmosis in a Patient Receiving Ixekizumab for Psoriasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2020, 6, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryaki, T.O.; Anıl, K.U.; Büyük, M.; Yıldırım, A.Y.; Atasoy, A.; Çiftçibaşı Örmeci, A.; Kalayoğlu Beşışık, S. Prolonged Severe Watery Diarrhea in a Long-Term Myeloma Survivor: An Unforeseen Infection with Cystoisospora Belli. Turk. J. Hematol. 2021, 38, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Díaz, A.L.; Alzate, J.C.; Villegas, E.; Giraldo, S.; Botero, J.; García-Montoya, G. Chronic Cystoisospora Belli Infection in a Colombian Patient Living with HIV and Poor Adherence to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Biomedica 2021, 41 (Suppl. 1), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, L.; Feng, Y. Molecular Epidemiology of Human Cryptosporidiosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkorta, M.; Manzanal, A.; Zeberio, I. A Case of Severe Diarrhoea Caused by Cyclospora Cayetanensis in an Immunocompromised Patient in Northern Spain. Access Microbiol. 2022, 4, 000313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahadiani, N.; Habiburrahman, M.; Putranto, A.S.; Handjari, D.R.; Stephanie, M.; Krisnuhoni, E. Fulminant Necrotizing Amoebic Colitis Presenting as Acute Appendicitis: A Case Report and Comprehensive Literature Review. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 16, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, O.; Hassan, A.; Mohamed, W.; Essmyer, C.; Ewing, E.; Lem, V.; Grobelny, B.; Breshears, J.; Akhtar, N. Disseminated Opportunistic Infections Masquerading as Central Nervous System Malignancies. Human Pathology Reports 2022, 28, 300629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaujia, R.; Mewara, A. Cystoisospora Belli: A Cause of Chronic Diarrhea in Immunocompromised Patients. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023, 108, 1084–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardar, S.K.; Goel, G.; Ghosal, A.; Deshmukh, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Haldar, T.; Maruf, M.M.; Mahto, R.; Kumar, J.; Bhave, S.J.; Dutta, S.; Ganguly, S. First Case Report of Cyclosporiasis from Eastern India: Incidence of Cyclospora Cayetanensis in a Patient with Unusual Diarrheal Symptoms. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2023, 17, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Yin, W. A Case of Septic Shock Due to Delayed Diagnosis of Cryptosporidium Infection after Liver Transplantation. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, S.L.; Erasmus, L.; Thomas, J.; Groome, M.J.; Plessis, N.M.D.; Avenant, T.; de Villiers, M.; Page, N.A. Epidemiology and aetiology of moderate to severe diarrhoea in hospitalised HIV-infected patients ≥5 years old in South Africa, 2018-2021: a case-control analysis. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.02.23.23286353v1.

- Younis, E.Z.; Elamami, A.H.; El-Salem, R.M. Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Benghazi, Libya. JCDO 2021, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konadu, E.; Essuman, M.A.; Amponsah, A.; Agroh, W.X.K.; Badu-Boateng, E.; Gbedema, S.Y.; Boakye, Y.D. Enteric Protozoan Parasitosis and Associated Factors among Patients with and without Diabetes Mellitus in a Teaching Hospital in Ghana. Int. J. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 5569262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, A.; Javanmard, E.; Rahimi, H.M.; Abdoli, A.; Matin, S.; Haghbin, M.; Olfatifar, M.; Mirjalali, H.; Zali, M.R. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections in Patients with Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Health 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sror, S.M.; Galal, S.M.; Mohamed, Y.M.; Dyab, A.K. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infection among Children with Chronic Liver Diseases, Assiut Governorate, Egypt. Aljouf Univ. Med. J. 2019, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łanocha, A.; Łanocha-Arendarczyk, N.; Wilczyńska, D.; Zdziarska, B.; Kosik-Bogacka, D. Protozoan Intestinal Parasitic Infection in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, A.D.; Saxena, N.G.; Thakare, S.B.; Pajai, A.E.; Bajpai, D.; Jamale, T.E. Diarrhea after Kidney Transplantation: A Study of Risk Factors and Outcomes. J. Postgrad. Med. 2023, 69, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslahi, A.V.; Olfatifar, M.; Zaki, L.; Karimipour Saryazdi, A.; Barikbin, F.; Maleki, A.; Abdoli, A.; Badri, M.; Karanis, P. Global Prevalence of Intestinal Protozoan Parasites among Food Handlers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Food Control 2023, 145, 109466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimam, Y.; Woreta, A.; Mohebali, M. Intestinal Parasites among Food Handlers of Food Service Establishments in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajare, S.T.; Gobena, R.K.; Chauhan, N.M.; Erniso, F. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasite Infections and Their Associated Factors among Food Handlers Working in Selected Catering Establishments from Bule Hora, Ethiopia. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6669742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lette, A.; Negash, G.; Kumbi, M.; Hussen, A.; Kassim, J.; Zenbaba, D.; Gezahgn, H.; Bonsa, M.; Aman, R.; Abdulkadir, A. Predictors of Intestinal Parasites among Food Handlers in, Southeast Ethiopia, 2020. J. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 2022, 3329237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondimu, H.; Mihret, M. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Intestinal Parasites among Food Handlers Working in Food Service Establishments in Northwest Ethiopia, 2022. J. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 2023, 3230139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, A.S.; Wakid, M.H.; Gattan, H.S. Prevalence, Type of Infections and Comparative Analysis of Detection Techniques of Intestinal Parasites in the Province of Belgarn, Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.; Ödemiş, N.; Yılmaz, H.; Beyhan, Y.E. Investigation of Parasites in Food Handlers in Turkey. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2023, 20, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.-Y.; Li, M.-Y.; Qi, Z.-Z.; Fu, M.; Sun, T.-F.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Cong, W. Waterborne Protozoan Outbreaks: An Update on the Global, Regional, and National Prevalence from 2017 to 2020 and Sources of Contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806 Pt 2, 150562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourli, P.; Eslahi, A.V.; Tzoraki, O.; Karanis, P. Waterborne Transmission of Protozoan Parasites: A Review of Worldwide Outbreaks - an Update 2017-2022. J. Water Health 2023, 21, 1421–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badri, M.; Olfatifar, M.; Karim, M.R.; Modirian, E.; Houshmand, E.; Abdoli, A.; Nikoonejad, A.; Sotoodeh, S.; Zargar, A.; Samimi, R.; Hashemipour, S.; Mahmoudi, R.; Harandi, M.F.; Hajialilo, E.; Piri, H.; Bijani, B.; Eslahi, A.V. Global Prevalence of Intestinal Protozoan Contamination in Vegetables and Fruits: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Food Control 2022, 133, 108656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifleyohannes, T.; Debenham, J.J.; Robertson, L.J. Is Fresh Produce in Tigray, Ethiopia a Potential Transmission Vehicle for Cryptosporidium and Giardia? Foods 2021, 10, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamandane, C.; Lobo, M.L.; Afonso, S.; Miambo, R.; Matos, O. Occurrence of Intestinal Parasites of Public Health Significance in Fresh Horticultural Products Sold in Maputo Markets and Supermarkets, Mozambique. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trelis, M.; Sáez-Durán, S.; Puchades, P.; Castro, N.; Miquel, A.; Gozalbo, M.; Fuentes, M.V. Survey of the Occurrence of Giardia Duodenalis Cysts and Cryptosporidium Spp. Oocysts in Green Leafy Vegetables Marketed in the City of Valencia (Spain). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 379, 109847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Mesonero, L.; Soler, L.; Amorós, I.; Moreno, Y.; Ferrús, M.A.; Alonso, J.L. Protozoan Parasites and Free-Living Amoebae Contamination in Organic Leafy Green Vegetables and Strawberries from Spain. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2023, 32, e00200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, A.; Rana, S.; Singh, R.; Gurian, P.L.; Betancourt, W.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A. Non-Potable Water Reuse and the Public Health Risks from Protozoa and Helminths: A Case Study from a City with a Semi-Arid Climate. J. Water Health 2023, 21, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, U.M.; Feng, Y.; Fayer, R.; Xiao, L. Taxonomy and Molecular Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium and Giardia - a 50 Year Perspective (1971-2021). Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 1099–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, U.; Zahedi, A.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, L. An Update on Zoonotic Cryptosporidium Species and Genotypes in Humans. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Razakandrainibe, R.; Valot, S.; Vannier, M.; Sautour, M.; Basmaciyan, L.; Gargala, G.; Viller, V.; Lemeteil, D.; French National Network on Surveillance of Human Cryptosporidiosis; Ballet, J.-J.; Dalle, F. Epidemiology of Cryptosporidiosis in France from 2017 to 2019. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujila, I.; Troell, K.; Ögren, J.; Hansen, A.; Killander, G.; Agudelo, L.; Lebbad, M.; Beser, J. Cryptosporidium species and subtypes identified in human domestic cases through the national microbiological surveillance programme in Sweden from 2018 to 2022. BMC Infect Dis. 2024, 24, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres Hutter, J.; Dion, R.; Irace-Cima, A.; Fiset, M.; Guy, R.; Dixon, B.; Aguilar, J.L.; Trépanier, J.; Thivierge, K. Cryptosporidium Spp.: Human Incidence, Molecular Characterization and Associated Exposures in Québec, Canada (2016-2017). PLoS One 2020, 15, e0228986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, R.A.; Yanta, C.A.; Muchaal, P.K.; Rankin, M.A.; Thivierge, K.; Lau, R.; Boggild, A.K. Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium Isolates from Humans in Ontario, Canada. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 69–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Ryan, U.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, L. Emergence of Zoonotic Cryptosporidium Parvum in China. Trends Parasitol. 2022, 38, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijjawi, N.; Zahedi, A.; Al-Falah, M.; Ryan, U. A Review of the Molecular Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium Spp. and Giardia Duodenalis in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2022, 98, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Qin, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium Infection in Children from China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Trop. 2023, 244, 106958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebbad, M.; Winiecka-Krusnell, J.; Stensvold, C.R.; Beser, J. High Diversity of Cryptosporidium Species and Subtypes Identified in Cryptosporidiosis Acquired in Sweden and Abroad. Pathogens 2021, 10, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujila, I.; Troell, K.; Fischerström, K.; Nordahl, M.; Killander, G.; Hansen, A.; Söderlund, R.; Lebbad, M.; Beser, J. Cryptosporidium Chipmunk Genotype I - An Emerging Cause of Human Cryptosporidiosis in Sweden. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021, 92, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughattas, S.; Behnke, J.M.; Al-Sadeq, D.; Ismail, A.; Abu-Madi, M. Cryptosporidium Spp., Prevalence, Molecular Characterisation and Socio-Demographic Risk Factors among Immigrants in Qatar. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, A.M. Transmission of Cryptosporidium by Fresh Vegetables. J. Food Prot. 2022, 85, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Guo, Y.; Lysen, C.; Wang, Y.; Tang, K.; Seabolt, M.H.; Yang, F.; Cebelinski, E.; Gonzalez-Moreno, O.; Hou, T.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Wan, M.; Li, N.; Hlavsa, M.C.; Roellig, D.M.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, L. Multiple Introductions and Recombination Events Underlie the Emergence of a Hyper-Transmissible Cryptosporidium Hominis Subtype in the USA. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, L.J.; Temesgen, T.T.; Tysnes, K.R.; Eikås, J.E. An Apple a Day: An Outbreak of Cryptosporidiosis in Norway Associated with Self-Pressed Apple Juice. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Witola, W.H. Past, Current, and Potential Treatments for Cryptosporidiosis in Humans and Farm Animals: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1115522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.L.; Chalmers, R.M.; Davies, A.P. Health Sequelae of Human Cryptosporidiosis in Industrialised Countries: A Systematic Review. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, A.; Ryan, U. Cryptosporidium - An Update with an Emphasis on Foodborne and Waterborne Transmission. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 132, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azami, M.; Amini Rarani, S.; Kiani, F. Treatment of Urticaria Caused by Severe Cryptosporidiosis in a 17-Month-Old Child - a Case Report. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pielok, Ł.; Nowak, S.; Kłudkowska, M.; Frąckowiak, K.; Kuszel, Ł.; Zmora, P.; Stefaniak, J. Massive Cryptosporidium Infections and Chronic Diarrhea in HIV-Negative Patients. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanadi, K.; Khalaf, A.K.; Jafrasteh, A.; Anbari, K.; Mahmoudvand, H. High Prevalence of Cryptosporidium Infection in Iranian Patients Suffering from Colorectal Cancer. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2022, 19, e00271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwknegt, M.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Graham, H.; Robertson, L.J.; van der Giessen, J.W.; Euro-FBP workshop participants. Prioritisation of Food-Borne Parasites in Europe, 2016. Euro Surveill. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.M.; Nasrin, D.; Acácio, S.; Bassat, Q.; Powell, H.; Tennant, S.M.; Sow, S.O.; Sur, D.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Faruque, A.S.G.; Hossain, M.J.; Alonso, P.L.; Breiman, R.F.; O’Reilly, C.E.; Mintz, E.D.; Omore, R.; Ochieng, J.B.; Oundo, J.O.; Tamboura, B.; Sanogo, D.; Onwuchekwa, U.; Manna, B.; Ramamurthy, T.; Kanungo, S.; Ahmed, S.; Qureshi, S.; Quadri, F.; Hossain, A.; Das, S.K.; Antonio, M.; Saha, D.; Mandomando, I.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Farag, T.; Wu, Y.; Houpt, E.R.; Verweiij, J.J.; Sommerfelt, H.; Nataro, J.P.; Robins-Browne, R.M.; Kotloff, K.L. Diarrhoeal Disease and Subsequent Risk of Death in Infants and Children Residing in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: Analysis of the GEMS Case-Control Study and 12-Month GEMS-1A Follow-on Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e204–e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Karanis, P. Cryptosporidium and Cryptosporidiosis: The Perspective from the Gulf Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpe, P.; Ni, Z.; Kabir, M.; Alam, M.; Ferdous, T.; Ara, R.; Munday, R.M.; Haque, R.; Duggal, P. Prospective Cohort Study of Cryptosporidium Infection and Shedding in Infants and Their Households. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 2178–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.J.; Saha, D.; Antonio, M.; Nasrin, D.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Ikumapayi, U.N.; Mackenzie, G.A.; Adeyemi, M.; Jasseh, M.; Adegbola, R.A.; Roose, A.W.; Kotloff, K.L.; Levine, M.M. Cryptosporidium Infection in Rural Gambian Children: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, Ø.H.; Abdissa, A.; Zangenberg, M.; Mekonnen, Z.; Eshetu, B.; Sharew, B.; Moyo, S.; Sommerfelt, H.; Langeland, N.; Robertson, L.J.; Hanevik, K. A Comparison of Risk Factors for Cryptosporidiosis and Non-Cryptosporidiosis Diarrhoea: A Case-Case-Control Study in Ethiopian Children. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, F.; Abbas, I.; Jawad, M.; Hijjawi, N. Cryptosporidium Infection in Humans and Animals from Iraq: A Review. Acta Trop. 2021, 220, 105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nic Lochlainn, L.M.; Sane, J.; Schimmer, B.; Mooij, S.; Roelfsema, J.; van Pelt, W.; Kortbeek, T. Risk Factors for Sporadic Cryptosporidiosis in the Netherlands: Analysis of a 3-Year Population Based Case-Control Study Coupled with Genotyping, 2013-2016. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watier-Grillot, S.; Costa, D.; Petit, C.; Razakandrainibe, R.; Larréché, S.; Tong, C.; Demont, G.; Billetorte, D.; Mouly, D.; Fontan, D.; Velut, G.; Le Corre, A.; Beauvir, J.-C.; Mérens, A.; Favennec, L.; Pommier de Santi, V. Cryptosporidiosis Outbreaks Linked to the Public Water Supply in a Military Camp, France. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschelli, A.; Bonadonna, L.; Cacciò, S.M.; Sannella, A.R.; Cintori, C.; Gargiulo, R.; Coccia, A.M.; Paradiso, R.; Iaconelli, M.; Briancesco, R.; Tripodi, A. An Outbreak of Cryptosporidiosis Associated with Drinking Water in North-Eastern Italy, August 2019: Microbiological and Environmental Investigations. Euro Surveill. 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Gong, B.; Liu, X.; Shen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cao, J. A Retrospective Epidemiological Analysis of Human Cryptosporidium Infection in China during the Past Three Decades (1987-2018). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokdyk, J.P.; Spencer, S.K.; Walsh, J.F.; de Lamber, J.R.; Firnstahl, A.D.; Anderson, A.C.; Rezania, L.I.W.; Borchardt, M.A. Cryptosporidium incidence and surface water influence of groundwater supplying public water systems in Minnesota, USA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 3391–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooh, P.; Thébault, A.; Cadavez, V.; Gonzales-Barron, U.; Villena, I. Risk Factors for Sporadic Cryptosporidiosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Risk Anal. 2021, 17, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, T.; Moro, L.; Requena-Méndez, A.; Bertoli, G.; Buonfrate, D. A Review of Outbreaks of Cryptosporidiosis Due to Unpasteurized Milk. Infection 2020, 48, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Scientific Opinion. The efficacy and safety of high-pressure processing of food. EFSA Journal 2022. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2022.7128. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-03/7128.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Gopfert, A.; Chalmers, R.M.; Whittingham, S.; Wilson, L.; van Hove, M.; Ferraro, C.F.; Robinson, G.; Young, N.; Nozad, B. An Outbreak of Cryptosporidium Parvum Linked to Pasteurised Milk from a Vending Machine in England: A Descriptive Study, March 2021. Epidemiol. Infect. 2022, 150, e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlinder, J.; Svedberg, A.-L.; Nystedt, A.; Dryselius, R.; Jacobsson, K.; Hägglund, M.; Brindefalk, B.; Forsman, M.; Ottoson, J.; Troell, K. Use of Metagenomic Microbial Source Tracking to Investigate the Source of a Foodborne Outbreak of Cryptosporidiosis. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2022, 26, e00142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankwa, K.; Nuvor, S.V.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Feglo, P.K.; Mutocheluh, M. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium Infection and Associated Risk Factors among HIV-Infected Patients Attending ART Clinics in the Central Region of Ghana. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Certad, G.; Follet, J.; Gantois, N.; Hammouma-Ghelboun, O.; Guyot, K.; Benamrouz-Vanneste, S.; Fréalle, E.; Seesao, Y.; Delaire, B.; Creusy, C.; Even, G.; Verrez-Bagnis, V.; Ryan, U.; Gay, M.; Aliouat-Denis, C.; Viscogliosi, E. Prevalence, Molecular Identification, and Risk Factors for Cryptosporidium Infection in Edible Marine Fish: A Survey across Sea Areas Surrounding France. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisuphanunt, M.; Wilairatana, P.; Kooltheat, N.; Damrongwatanapokin, T.; Karanis, P. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium Oocysts in Commercial Oysters in Southern Thailand. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2023, 32, e00205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratal, S.; Dea-Ayuela, M.A.; Martí-Marco, A.; Puigcercós, S.; Marco-Hirs, N.M.; Doménech, C.; Corcuera, E.; Cardells, J.; Lizana, V.; López-Ramon, J. Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium Spp. In Cultivated and Wild Marine Fishes from Western Mediterranean with the First Detection of Zoonotic Cryptosporidium Ubiquitum. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servián, A.; Lorena Zonta, M.; Navone, G.T. Differential Diagnosis of Human Entamoeba Infections: Morphological and Molecular Characterization of New Isolates in Argentina. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balarabe-Musa, B.; Onyeagba, K.D. Prevalence of Entamoeba Histolytica amongst Infants with Diarrhoea Visiting the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital. Journal of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences 2020, 2, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Coria, A.; Kumar, M.; Chadee, K. The Delicate Balance between Entamoeba Histolytica, Mucus and Microbiota. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Banerjee, T. Host-Parasite Interactions in Infections Due to Entamoeba Histolytica: A Tale of Known and Unknown. Trop. Parasitol. 2022, 12, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morán, P.; Serrano-Vázquez, A.; Rojas-Velázquez, L.; González, E.; Pérez-Juárez, H.; Hernández, E.G.; Padilla, M. de L.A.; Zaragoza, M.E.; Portillo-Bobadilla, T.; Ramiro, M.; Ximénez, C. Amoebiasis: Advances in Diagnosis, Treatment, Immunology Features and the Interaction with the Intestinal Ecosystem. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.-H.; Chen, B.-C.; Chou, Y.-C.; Chien, W.-C.; Chung, C.-H.; Hsieh, C.-J.; Yu, C.-P. The Epidemiology of Entamoeba histolytica Infection and Its Associated Risk Factors among Domestic and Imported Patients in Taiwan during the 2011–2020 Period. Medicina 2022, 58, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Sendzischew Shane, M.; Deshpande Amar, R.; Milikowski, C. An Unusual Case of Entamoeba Histolytica Infection in Miami Fl: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Res. Rev. Infect. Dis. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, A.; Mahlaule, L.; Mbati, P.; Nozaki, T.; ElBakri, A. Prevalence and Distribution of Entamoeba Species in a Rural Community in Northern South Africa. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2020, 18, e00076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kanthan, R. Multiple Colonic and Ileal Perforations Due to Unsuspected Intestinal Amoebiasis-Case Report and Review. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020, 216, 152608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuda, D.; Tsuge, S.; Sakurai, R.; Kawai, K.; Matsubara, S.; Tanaka, R.; Suzuki, M.; Takano, H.; Shimozawa, S.; Hotchi, Y.; Tokunaga, S.; Osugi, I.; Katou, R.; Ito, S.; Mishima, K.; Kondo, A.; Mizuno, K.; Takami, H.; Komatsu, T.; Oba, J.; Nomura, T.; Sugita, M. Amebic Liver Abscess by Entamoeba Histolytica. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 13157–13166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrero, J.C.; Reyes-López, M.; Serrano-Luna, J.; Shibayama, M.; Unzueta, J.; León-Sicairos, N.; de la Garza, M. Intestinal Amoebiasis: 160 Years of Its First Detection and Still Remains as a Health Problem in Developing Countries. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 310, 151358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Wiehe, R.; Dommisch, H.; Schaefer, A.S. Entamoeba Gingivalis Causes Oral Inflammation and Tissue Destruction. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda. 2022 ISBN 978-92-4-004506-4. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352532/9789240045064-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=153 (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Fichardt, H.J.; Rocha, J. S2741 Entamoeba Histolytica Dysentery Complicated by Amebic Liver Abscess and Type a Right Heart Thrombus: A Case Report. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, S1432–S1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R.W.J.; Allgeier, J.; Philipp, A.B.; Mayerle, J.; Rothe, C.; Wallrauch, C.; Op den Winkel, M. Development of Amoebic Liver Abscess in Early Pregnancy Years after Initial Amoebic Exposure: A Case Report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaih, M.H.; Khazaal, R.M.; Kadhim, M.K.; Hussein, K.R.; Alhamadani, F.A.B. The Epidemiology of Amoebiasis in Thi-Qar Province, Iraq (2015-2020): Differentiation of Entamoeba Histolytica and Entamoeba Dispar Using Nested and Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, K.T.; Rostam, R.A.; Nasir, K. ِِ.; Qasem, A.O.; Azize, P.M. Epidemiological Study for Entamoeba Histolytica Infection and Their Risk Factors among Children in Pediatric Hospital in, Sulaimani Province-Iraq. Kufa Jour. Nurs. Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Daoody, A.A.K.; A. Ali, F.; Sadiq, L.B.; Samer Mamand, A.; Salah Ismail, R.; Fatah Muhammed, H. Investigation of Intestinal Protozoan Infections among Food-Handlers in Erbil City, Iraq. Plant Arch. 2021, 21, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Bunza, N.; Sale Kumurya, A.; Muhammad, A. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Food Handlers in Kano Metropolis, Kano State, Nigeria. Microbes and Infectious Diseases 2020, 0, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Zanetti, A.; Malheiros, A.F.; de Matos, T.A.; Dos Santos, C.; Battaglini, P.F.; Moreira, L.M.; Lemos, L.M.S.; Castrillon, S.K.I.; da Costa Boamorte Cortela, D.; Ignotti, E.; Espinosa, O.A. Diversity, Geographical Distribution, and Prevalence of Entamoeba Spp. in Brazil: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parasite 2021, 28, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roro, G.B.; Eriso, F.; Al-Hazimi, A.M.; Kuddus, M.; Singh, S.C.; Upadhye, V.; Hajare, S.T. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Entamoeba Histolytica Infection among School Children from Three Primary Schools in Arsi Town, West Zone, Ethiopia. J. Parasit. Dis. 2022, 46, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokijoh, N.I.; Bakar, A.A.; Othman, N.; Noordin, R.; Saidin, S. Assessing the Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Entamoeba Complex Infection among the Orang Asli School Children in Perak, Malaysia through Molecular Approach. Parasitol. Int. 2022, 91, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabati, H.; Kassiri, H.; Shamloo, E.; Akbari, M.; Atamaleki, A.; Sahlabadi, F.; Linh, N.T.T.; Rostami, A.; Fakhri, Y.; Khaneghah, A.M. The Association between the Lack of Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation Facilities with Intestinal Entamoeba Spp Infection Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0237102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yousofi, A.; Yan, Y.; Al Mekhlafi, A.M.; Hezam, K.; Abouelnazar, F.A.; Al-Rateb, B.; Almamary, H.; Abdulwase, R. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites among Immunocompromised Patients, Children, and Adults in Sana’a, Yemen. J. Trop. Med. 2022, 2022, 5976640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, H.; Davtalab-Esmaeili, E.; Mirzapour, M.; Karimi, G.; Rostampour, M.; Mirzaei, Y. A Case-Control Study of Timely Control and Investigation of an Entamoeba Histolytica Outbreak by Primary Health Care in Idahluy-e Bozorg Village, Iran. Int. J. Epidemiol. Res. 2019, 6, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Esiobu, N.; Meeroff, D.; Bloetscher, F. Different Detection and Treatment Methods for Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar in Water/Wastewater: A Review. Journal of Environmental Protection, 2022, 13, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert Algaba, I.; Verhaegen, B.; Murat, J.B.; Coucke, W.; Mercier, A.; Cox, E.; Dorny, P.; Dierick, K.; De Craeye, S. Molecular Study of Toxoplasma Gondii Isolates Originating from Humans and Organic Pigs in Belgium. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2020, 17, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, A.; Blanchard, N.; Besteiro, S. The Bradyzoite: A Key Developmental Stage for the Persistence and Pathogenesis of Toxoplasmosis. Pathogens 2020, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakroub, H.; Sgroi, G.; D’Alessio, N.; Russo, D.; Serra, F.; Veneziano, V.; Rea, S.; Pucciarelli, A.; Lucibelli, M.G.; De Carlo, E.; Fusco, G.; Amoroso, M.G. Molecular Survey of Toxoplasma Gondii in Wild Mammals of Southern Italy. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducrocq, J.; Simon, A.; Lemire, M.; De Serres, G.; Lévesque, B. Exposure to Toxoplasma Gondii through Consumption of Raw or Undercooked Meat: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021, 21, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshina, T.; Horino, T.; Saiki, E.; Aonuma, H.; Sawaki, K.; Miyajima, M.; Lee, K.; Nakaharai, K.; Shimizu, A.; Hosaka, Y.; Kato, T.; Sato, F.; Nakazawa, Y.; Yoshikawa, K.; Yoshida, M.; Hori, S.; Kanuka, H. Seroprevalence and Associated Factors of Toxoplasma Gondii among HIV-Infected Patients in Tokyo: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 26, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral Monica, T.; Pinto-Ferreira, F.; Martins, F.D.C.; de Matos, R.L.N.; de Matos, A.M.R.N.; Santos, A.C.; Nino, B. de S. L.; Pereira, L.; Narciso, S.G.; Garcia, J.L.; Freire, R.L.; Navarro, I.T.; Mitsuka-Bregano, R. Epidemiology of a Toxoplasmosis Outbreak in a Research Institution in Northern Paraná, Brazil. Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, M.A.; Pinto-Ferreira, F.; de Almeida, R.P.A.; Martins, F.D.C.; Pires, A.L.; Mareze, M.; Mitsuka-Breganó, R.; Freire, R.L.; da Rocha Moreira, R.V.; Borges, J.M.; Navarro, I.T. Artisan Fresh Cheese from Raw Cow’s Milk as a Possible Route of Transmission in a Toxoplasmosis Outbreak, in Brazil. Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuzzi, C.E.; Fernandes, F.D.; Portella, L.P.; Bräunig, P.; Sturza, D.A.F.; Giacomini, L.; Salvagni, E.; Ribeiro, J.D.S.; Silva, C.R.; Difante, C.M.; Farinha, L.B.; Menegolla, I.A.; Gehrke, G.; Dilkin, P.; Sangioni, L.A.; Mallmann, C.A.; Vogel, F.S.F. Contaminated Water Confirmed as Source of Infection by Bioassay in an Outbreak of Toxoplasmosis in South Brazil. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, A.C.; Elbadawi, L.I.; DeSalvo, T.; Straily, A.; Ajzenberg, D.; Letzer, D.; Moldenhauer, E.; Handly, T.L.; Hill, D.; Dardé, M.-L.; Pomares, C.; Passebosc-Faure, K.; Bisgard, K.; Gomez, C.A.; Press, C.; Smiley, S.; Montoya, J.G.; Kazmierczak, J.J. Toxoplasmosis Outbreak Associated with Toxoplasma Gondii-Contaminated Venison-High Attack Rate, Unusual Clinical Presentation, and Atypical Genotype. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, R.; Kodo, Y.; Maeno, A.; Suzuki, J.; Mori, K.; Sadamasu, K.; Kawahara, F.; Nagamune, K. Detection of Toxoplasma Gondii and Sarcocystis Sp. in the Meat of Common Minke Whale (Balaenoptera Acutorostrata): A Case of Suspected Food Poisoning in Japan. Parasitol. Int. 2023, 99, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangi, M.; Lago, N.; Mancinelli, G.; Antonio, O.L.; Scirocco, T.; Sinigaglia, M.; Specchiulli, A.; Cilenti, L. Occurrence of the protozoan parasites Toxoplasma gondii and Cyclospora cayetanensis in the invasive Atlantic blue crab Callinectes sapidus from the Lesina Lagoon (SE Italy). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 176, 113428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çulbasan, V.; Gungor, C.; Gundog, D.A.; Koskeroglu, K.; Onmaz, N.E. Molecular surveillance of Toxoplasma gondii in raw milk and Artisan cheese of sheep, goat, cow and water buffalo origin. Int J Dairy Technol, 2023, 76, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbuigwe, P.; Biggs, P.J.; Garcia-Ramirez, J.C.; Knox, M.A.; Pita, A.; Velathanthiri, N.; French, N.P.; Hayman, D.T.S. Uncovering the Genetic Diversity of Giardia Intestinalis in Isolates from Outbreaks in New Zealand. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2022, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, U.; Hijjawi, N.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, L. Giardia: An under-Reported Foodborne Parasite. Int. J. Parasitol. 2019, 49, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resi, D.; Varani, S.; Sannella, A.R.; De Pascali, A.M.; Ortalli, M.; Liguori, G.; Benvenuti, M.; Re, M.C.; Pirani, R.; Prete, L.; Mazzetti, C.; Musti, M.; Pizzi, L.; Sanna, T.; Cacciò, S.M. A Large Outbreak of Giardiasis in a Municipality of the Bologna Province, North-Eastern Italy, November 2018 to April 2019. Euro Surveill. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhri, Y.; Daraei, H.; Ghaffari, H.R.; Rezapour-Nasrabad, R.; Soleimani-Ahmadi, M.; Khedher, K.M.; Rostami, A.; Thai, V.N. The Risk Factors for Intestinal Giardia Spp Infection: Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Acta Trop. 2021, 220, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoseinzadeh, E.; Rostamian, A.; Razaghi, M.; Wei, C. Waterborne Transmission of Protozoan Parasites: A Review of Water Resources in Iran - an Update 2020. Desalination And Water Treatment 2021, 213, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadi, W.F.; Rathi, M.H.; Molan, A.-L. The Possible Link between Intestinal Parasites and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) in Diyala Province, Iraq. Ann. Parasitol. 2021, 67, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thébault, A.; Favennec, L.; Kooh, P.; Cadavez, V.; Gonzales-Barron, U.; Villena, I. Risk Factors for Sporadic Giardiasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Risk Anal. 2021, 17, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, S.H.; Fazlzadeh, A.; Mollalo, A.; Sartip, B.; Mahjour, S.; Bahadory, S.; Taghipour, A.; Rostami, A. The Neglected Role of Blastocystis Sp. and Giardia Lamblia in Development of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 162, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaima, S.N.; Das, S.K.; Ahmed, S.; Jahan, Y.; Khan, S.H.; Mamun, G.M.S.; Shahid, A.S.M.S.B.; Parvin, I.; Ahmed, T.; Faruque, A.S.G.; Chisti, M.J. Anthropometric Indices of Giardia-Infected under-Five Children Presenting with Moderate-to-Severe Diarrhea and Their Healthy Community Controls: Data from the Global Enteric Multicenter Study. Children (Basel) 2021, 8, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groudan, K.; Gupta, K.; Chalhoub, J.; Singhania, R. Giardia Lamblia Diagnosed Incidentally by Duodenal Biopsy. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2021, 9, 23247096211001649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurník, P.; Žiak, D.; Dluhošová, J.; Židlík, V.; Šustíková, J.; Uvírová, M.; Urban, O.; Dvořáčková, J.; Nohýnková, E. Another Case of Coincidental Giardia Infection and Pancreatic Cancer. Parasitol. Int. 2019, 71, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loderstädt, U.; Frickmann, H. Antimicrobial Resistance of the Enteric Protozoon Giardia Duodenalis - A Narrative Review. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. (Bp.) 2021, 11, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/945 of 22 June 2018 on the communicable diseases and related special health issues to be covered by epidemiological surveillance as well as relevant case definitions (Text with EEA relevance.). Official Journal of the European Union. 2018 L 170/1. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2018.170.01.0001.01.ENG (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) Giardiasis (lambliasis) - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2019. 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/giardiasis-%20annual-epidemiological-report-2019_0.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Al-Jawabreh, A.; Ereqat, S.; Dumaidi, K.; Al-Jawabreh, H.; Abdeen, Z.; Nasereddin, A. Prevalence of Selected Intestinal Protozoan Infections in Marginalized Rural Communities in Palestine. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro, C.; Chávez-Romero, Y.A.; Prada, S.L.G.; Serrano-Silva, N.; Bernal, J.E.; González-Jiménez, F.E.; Sarria-Guzmán, Y. Burden and Epidemiology of Human Intestinal Giardia Duodenalis Infection in Colombia: A Systematic Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, D.; Reta, T. Prevalence and distribution of Giardia lamblia infection among patients of children aged 5-11years treated in Sheno town health centers, North Shoa Oromia region, Ethiopia. ClinicSearch 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, S.J.; Mutengo, M.M.; Sitali, L.; Changula, K.; Takada, A.; Mweene, A.S.; Simulundu, E.; Chitanga, S. Prevalence and Genotypic Characterization of Giardia Duodenalis Isolates from Asymptomatic School-Going Children in Lusaka, Zambia. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2020, 19, e00072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muadica, A.S.; Balasegaram, S.; Beebeejaun, K.; Köster, P.C.; Bailo, B.; Hernández-de-Mingo, M.; Dashti, A.; Dacal, E.; Saugar, J.M.; Fuentes, I.; Carmena, D. Risk Associations for Intestinal Parasites in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Schoolchildren in Central Mozambique. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, B.R. Giardia Duodenalis in Humans and Animals - Transmission and Disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021, 135, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawana, M.; Onyiche, T.E.; Ramatla, T.; Thekisoe, O. A “One Health” Perspective of Africa-Wide Distribution and Prevalence of Giardia Species in Humans, Animals and Waterbodies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parasitology 2023, 150, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneto, E.G.; Fernandes-Silva, M.M.; Toledo-Cornell, C.; Martins, S.; Ferreira, J.M.B.; Corrêa, V.R.; da Costa, J.M.; Pinto, A.Y. das N.; de Souza, D. do S. M.; Pinto, M.C.G.; Neto, J.A. de F.; Ramos, A.N.; Maguire, J.H.; Silvestre, O.M. Case-Fatality from Orally-Transmitted Acute Chagas Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Ortiz, N.; Ramírez, J.D. Understanding the Oral Transmission of Trypanosoma Cruzi as a Veterinary and Medical Foodborne Zoonosis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 132, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.K.S.B. de; Sousa, D.R.T. de; Silva Junior, E.F. da; Ruiz, H.J. da S.; Arcanjo, A.R.L.; Ortiz, J.V.; Brito, S.S. de; Jesus, D.V.; Lima, J.R.C. de; Couceiro, K. do N.; Silva, M.R.H. da S. E.; Ferreira, J.M.B.B.; Guerra, J.A.O.; Guerra, M. das G. V. B. Acute Micro-Outbreak of Chagas Disease in the Southeastern Amazon: A Report of Five Cases. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2022, 55, e0687. [Google Scholar]

- Esper, H.R.; Freitas, V.L.T. de; Assy, J.G.P.L.; Shimoda, E.Y.; Berreta, O.C.P.; Lopes, M.H.; França, F.O.S. Fatal Evolution of Acute Chagas Disease in a Child from Northern Brazil: Factors That Determine Poor Prognosis. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2019, 61, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Ortiz, N.; Herrera, G.; Hernández, C.; Muñoz, M.; Ramírez, J.D. Discrete Typing Units of Trypanosoma Cruzi: Geographical and Biological Distribution in the Americas. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A.C.; Soccol, V.T.; Rogez, H. Prevention Methods of Foodborne Chagas Disease: Disinfection, Heat Treatment and Quality Control by RT-PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 301, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathison, B.A.; Pritt, B.S. Cyclosporiasis-Updates on Clinical Presentation, Pathology, Clinical Diagnosis, and Treatment. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, J.L.N.; Shen, J.; Houghton, K.; Richins, T.; Sapp, S.G.H.; Cama, V.; Arrowood, M.J.; Straily, A.; Qvarnstrom, Y. Cyclospora Cayetanensis Comprises at Least 3 Species That Cause Human Cyclosporiasis. Parasitology 2023, 150, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, R.; Angulo-Várguez, F.; Ávila-Nava, A.; Gutiérrez-Solis, A.L.; Reyes-Sosa, M.; Medina-Escobedo, M. Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Intestinal Infection by Cyclospora Cayetanensis in a Kidney Transplant Patient. A Case Report. Parasitol. Int. 2021, 80, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn, N.; Lamphier, I.; Klinkova, O.; Baluch, A.; Pasikhova, Y.; Greene, J. Intestinal Coccidian Infections in Cancer Patients: A Case Series. Cureus 2023, 15, e38256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeria, S.; Chacin-Bonilla, L.; Maloney, J.G.; Santin, M. Cyclospora Cayetanensis: A Perspective (2020-2023) with Emphasis on Epidemiology and Detection Methods. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacin-Bonilla, L.; Santin, M. Cyclospora Cayetanensis Infection in Developed Countries: Potential Endemic Foci? Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahart, L.; Jacobson, D.; Rice, M.; Richins, T.; Peterson, A.; Zheng, Y.; Barratt, J.; Cama, V.; Qvarnstrom, Y.; Montgomery, S.; Straily, A. Retrospective Evaluation of an Integrated Molecular-Epidemiological Approach to Cyclosporiasis Outbreak Investigations - United States, 2021. Epidemiol. Infect. 2023, 151, e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanzadeh, S.; Barzegar, G.; Osquee, H.O.; Pirestani, M.; Mahami-Oskouei, M.; Hajizadeh, M.; Hosseini, S.A.; Rodrigues Oliveira, S.M.; Agholi, M.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Ahmadpour, E. Microscopic and Molecular Identification of Cyclospora Cayetanensis and Cystoisospora Belli in HIV-Infected People in Tabriz, Northwest of Iran. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ögren, J.; Dienus, O.; Beser, J.; Henningsson, A.J.; Matussek, A. Protozoan Infections Are Under-Recognized in Swedish Patients with Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 2153–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacin-Bonilla, L.; Sanchez, Y.; Cardenas, R. Factors Associated with Cyclospora Infection in a Venezuelan Community: Extreme Poverty and Soil Transmission Relate to Cyclosporiasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023, 117, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlaam, A.; Temesgen, T.T.; Tysnes, K.R.; Rinaldi, L.; Ferrari, N.; Sannella, A.R.; Normanno, G.; Cacciò, S.M.; Robertson, L.J.; Giangaspero, A. Contamination of Fresh Produce Sold on the Italian Market with Cyclospora Cayetanensis and Echinococcus Multilocularis. Food Microbiol. 2021, 98, 103792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temesgen, T.T.; Stigum, V.M.; Robertson, L.J. Surveillance of berries sold on the Norwegian market for parasite contamination using molecular methods. Food Microbiol. 2022, 104, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalonde, L.; Oakley, J.; Fries, P. Verification and Use of the US-FDA BAM 19b Method for Detection of Cyclospora cayetanensis in a Survey of Fresh Produce by CFIA Laboratory. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeria, S.; Shipley, A. Detection of Cyclospora cayetanensis on bagged pre-cut salad mixes within their shelf-life and after sell by date by the U.S. food and drug administration validated method. Food Microbiol. 2021, 98, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giarratana, F.; Nalbone, L.; Napoli, E.; Lanzo, V.; Panebianco, A. Prevalence of Balantidium coli (Malmsten, 1857) Infection in Swine Reared in South Italy: A Widespread Neglected Zoonosis. Vet. World 2021, 14, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaw, A.; Berhan, A.; Solomon, Y.; Malkamu, B.; Eyayu, T.; Workineh, L.; Mekete, G.; Yayehrad, A.T. Balantidium coli; Rare and Accidental Finding in the Urine of Pregnant Woman: Case Report. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2022, 15, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy Souza Araújo, R.; Rios da Silva, A.; Souza, N.R.; Santos de Melo, K. Parasitological Analysis of Vegetables Sold in Supermarkets and Free Markets in the City of Taguatinga, Federal District, Brazil. Rev. Patol. Trop. 2022, 51, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Li, F.; Chen, D.; Ma, Y. Cystoisospora Belli Infection in an AIDS Patient in China: Need for Cautious Interpretation of mNGS. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 40, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial-Crestelo, D.; Otero, B.; Pérez-Ayala, A.; Pinto, A.; Pulido, F. Severe Diarrhea by Cystoisospora Belli in a Well Controlled HIV-Infected Patient. AIDS 2022, 36, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G.S.; Arnold, C.A.; Badizadegan, K.; Carter, C.M.; Conces, M.R.; Kahwash, S.B.; Nicol, K.K.; Arnold, M.A. Cytoplasmic Fibrillar Aggregates in Gallbladder Epithelium Are a Frequent Mimic of Cystoisospora in Pediatric Cholecystectomy Specimens. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2019, 143, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, A.; Alkhasawneh, A.; Mubeen, A.; Makary, R.; Mohammed, I.; Baskovich, B. Pitfalls in Morphologic Diagnosis of Pathogens: Lessons Learned from the Pseudo-Cystoisospora Epidemic. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021, 29, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.M. Detection of Cystoisospora belli among Children in Sulaimaniyah, Iraq. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Vizon, K.C.C.; Battad, Z.G., 2nd; Castillo, D.S.C. Contamination of Food-Borne Parasites from Green-Leafy Vegetables Sold in Public Markets of San Jose City, Nueva Ecija, Philippines. J. Parasit. Dis. 2019, 43, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barua, P.; Banik, K.S.; Saha, S.; Musa, S. Parasitic contamination of street food samples from schoolbased food vendors of Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Zool. 2023, 51, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Van Damme, I.; Kabi, T.W.; Šoba, B.; Gabriël, S. Sarcocystis Species in Bovine Carcasses from a Belgian Abattoir: A Cross-Sectional Study. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, T.; Nakano, Y.; Mizuno, T.; Shiozaki, A.; Hori, Y.; Yamanishi, K.; Hayakawa, K.; Hayakawa, T.; Fujimoto, T.; Nakamoto, C.; Maejima, K.; Wada, Y.; Terasoma, F.; Ohnishi, T. First Case Report of Possible Sarcocystis Truncata-Induced Food Poisoning in Venison. Intern. Med. 2019, 58, 2727–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiola, S.; Moré, G.; Civera, T.; Hemphill, A.; Frey, C.F.; Basso, W.; Colasanto, I.; Vercellino, D.; Fidelio, M.; Lovisone, M.; Chiesa, F. Detection of Sarcocystis Hominis, Sarcocystis Bovifelis, Sarcocystis Cruzi, Sarcocystis Hirsuta and Sarcocystis Sigmoideus Sp. Nov. in Carcasses Affected by Bovine Eosinophilic Myositis. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2024, 34, e00220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M.; Shamsi, L.; Asghari, A.; Motazedian, M.H.; Mohammadi-Ghalehbin, B.; Omidian, M.; Nazari, N.; Sadrebazzaz, A. Molecular Epidemiology, Species Distribution, and Zoonotic Importance of the Neglected Meat-Borne Pathogen Sarcocystis Spp. In Cattle (Bos Taurus): A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Parasitol. 2022, 67, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzonis, A.L.; Gjerde, B.; Villa, L.; Minazzi, S.; Zanzani, S.A.; Riccaboni, P.; Sironi, G.; Manfredi, M.T. Prevalence and Molecular Characterisation of Sarcocystis Miescheriana and Sarcocystis in Wild Boars (Sus Scrofa) in Italy. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1271–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakas, P.; Kirillova, V.; Dzerkale, A.; Kirjušina, M.; Butkauskas, D.; Gavarāne, I.; Rudaitytė-Lukošienė, E.; Šulinskas, G. First Molecular Characterization of Sarcocystis Miescheriana in Wild Boars (Sus Scrofa) from Latvia. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 3777–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helman, E.; Dellarupe, A.; Cifuentes, S.; Chang Reissig, E.; Moré, G. Identification of Sarcocystis Spp. in Wild Boars (Sus Scrofa) from Argentina. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metwally, D.M.; Al-Damigh, M.A.; Al-Turaiki, I.M.; El-Khadragy, M.F. Molecular Characterization of Sarcocystis Species Isolated from Sheep and Goats in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Animals (Basel) 2019, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Spotin, A.; Rostamian, M.; Adami, M. Prevalence and Molecular Assessment of Sarcocystis Infection in Livestock in Northeast Iran. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 80, 101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Guo, R.; Sang, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Yang, N.; Jiang, T. A Systematic Meta-Analysis of Global Sarcocystis Infection in Sheep and Goats. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januskevicius, V.; Januskeviciene, G.; Prakas, P.; Butkauskas, D.; Petkevicius, S. Prevalence and Intensity of Sarcocystis Spp. Infection in Animals Slaughtered for Food in Lithuania. Vet. Med. (Praha) 2019, 64, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Ying, Z.; Feng, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J. The Occurrence and Meta-Analysis of Investigations on Sarcocystis Infection among Ruminants (Ruminantia) in Mainland China. Animals (Basel) 2022, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidvand, Z.; Khazaei, S.; Amiri, M.; Taherkhani, H.; Mirzaei, A. Worldwide Prevalence of Emerging Parasite Blastocystis in Immunocompromised Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 152, 104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.M.; Ismail, K.A.; Khalifa, O.M.; Abdel-wahab, M.M.; Hagag, H.M.; Mahmoud, M.K. Molecular Identification of Blastocystis hominis Isolates in Patients with Autoimmune Diseases. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakid, M.H.; Aldahhasi, W.T.; Alsulami, M.N.; El-Kady, A.M.; Elshabrawy, H.A. Identification and Genetic Characterization of Blastocystis Species in Patients from Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, J.G.; Molokin, A.; Seguí, R.; Maravilla, P.; Martínez-Hernández, F.; Villalobos, G.; Tsaousis, A.D.; Gentekaki, E.; Muñoz-Antolí, C.; Klisiowicz, D.R.; et al. Identification and Molecular Characterization of Four New Blastocystis Subtypes Designated ST35-ST38. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piubelli, C.; Soleymanpoor, H.; Giorli, G.; Formenti, F.; Buonfrate, D.; Bisoffi, Z.; Perandin, F. Blastocystis Prevalence and Subtypes in Autochthonous and Immigrant Patients in a Referral Centre for Parasitic Infections in Italy. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0210171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinek, O.; Polackova, K.; Odeh, R.; Alassaf, A.; Kramná, L.; Ibekwe, M.U.; Majaliwa, E.S.; Ahmadov, G.; Elmahi, B.M.E.; Mekki, H.; Oikarinen, S.; Lebl, J.; Abdullah, M.A. Blastocystis in the Faeces of Children from Six Distant Countries: Prevalence, Quantity, Subtypes and the Relation to the Gut Bacteriome. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauff-Adedotun, A.A.; Meor Termizi, F.H.; Shaari, N.; Lee, I.L. The Coexistence of Blastocystis Spp. In Humans, Animals and Environmental Sources from 2010-2021 in Asia. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, Y.A.; Ooda, S.A.; Salem, A.I.; Idris, S.N.; Elderbawy, M.M.; Tolba, M.M. Molecular Diagnosis and Subtyping of Blastocystis Sp.: Association with Clinical, Colonoscopic, and Histopathological Findings. Trop. Parasitol. 2023, 13, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gureser, A.S.; Karasartova, D.; Sarzhanov, F.; Kosar, N.; Taylan-Ozkan, A.; Dogruman-Al, F. Prevalence of Blastocystis and Dientamoeba Fragilis in Diarrheal Patients in Corum, Türkiye. Parasitol. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangi, M.; Boughattas, S.; De Nittis, R.; Pisanelli, D.; Delli Carri, V.; Lipsi, M.R.; La Bella, G.; Serviddio, G.; Niglio, M.; Lo Caputo, S.; Margaglione, M.; Arena, F. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Blastocystis Sp. among Autochthonous and Immigrant Patients in Italy. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 185, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.H.; Ismail, M.A.M.; El-Badry, A.A.; Abu-Sarea, E.Y.; Dewidar, A.M.; Hamdy, D.A. An Association between Blastocystis Subtypes and Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Significant Different Profile from Non-Cancer Individuals. Acta Parasitol. 2022, 67, 752–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Velázquez, L.; Maloney, J.G.; Molokin, A.; Morán, P.; Serrano-Vázquez, A.; González, E.; Pérez-Juárez, H.; Ximénez, C.; Santin, M. Use of Next-Generation Amplicon Sequencing to Study Blastocystis Genetic Diversity in a Rural Human Population from Mexico. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzińska, M.; Sikorska, K. Epidemiology of Blastocystis Infection: A Review of Data from Poland in Relation to Other Reports. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutahar, M.; Belaouni, M.; Ibrahimi, A.; Eljaoudi, R.; Aanniz, T.; Er-Rami, M. Prevalence of Blastocystis Sp. in Morocco: Comparative Assessment of Three Diagnostic Methods and Characterization of Parasite Forms in Jones’ Culture Medium. Parasite 2023, 30, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, F.; Babaei, E.; Badirzadeh, A.; Riabi, T.R.; Abdoli, A. Blastocystis, Urticaria, and Skin Disorders: Review of the Current Evidences. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamlih, L.; Abufaied, M.; Al-Allaf, A.-W. An Unusual Cause of Reactive Arthritis with Urticarial: A Case Report. Qatar Med. J. 2020, 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Permasutha, M.B.; Pranata, I.W.A.; Diptyanusa, A.; Murhandarwati, E.E.H. Blastocystis Hominis Infection in HIV/AIDS Children with Extraintestinal Symptom: A Case Report. Bali Med. J. 2022, 11, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascuña-Durand, K.; Salazar-Sánchez, R.S.; Cartillo-Neyra, R.; Ballón-Echegaray, J. Molecular Epidemiology of Blastocystis in Urban and Periurban Human Populations in Arequipa, Peru. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zawawy, H.T.; Farag, H.F.; Tolba, M.M.; Abdalsamea, H.A. Improving Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis by Eradicating Blastocystis Hominis: Relation to IL-17. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 11, 2042018820907013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed Ahmed Nasr, M.; Mohammed Abdellatif, M.; Belal, U.; Abdel-Hafeez, E.; Abdalgelil, N. Detection of Blastocystis Species in the Stool of Immuno-Compromised Patients by Using Two Different Diagnostic Techniques. Minia Journal of Medical Research 2023, 34, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Gonzalez, L.A.; Salgado-Lopez, J.; Pineda-Rodriguez, S.A.; Martinez, A.; Romero-Valdovinos, M.; Martinez-Hernandez, F.; Rendon-Franco, E.; Olivo-Diaz, A.; Maravilla, P.; Rodriguez-Bataz, E. Identification of Blastocystis Sp. in School Children from a Rural Mexican Village: Subtypes and Risk Factors Analysis. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinatham, V.; Wandee, T.; Nonebudsri, C.; Popluechai, S.; Tsaousis, A.D.; Gentekaki, E. Blastocystis Subtypes in Raw Vegetables from Street Markets in Northern Thailand. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Safadi, D.; Osman, M.; Hanna, A.; Hajar, I.; Kassem, I.I.; Khalife, S.; Dabboussi, F.; Hamze, M. Parasitic Contamination of Fresh Leafy Green Vegetables Sold in Northern Lebanon. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraldi, S.; Angileri, L.; Rossi, L.C.; Nazzaro, G. Endolimax Nana and Urticaria. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hasnawy, M.H.; Rabee, A.H. A Review on Trichomonas Species Infection in Humans and Animals in Iraq. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 2023, 37, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, S.M.; Ghallab, M.M.I.; Elhawary, N.M.; Elhadad, H. Pentatrichomonas hominis and other intestinal parasites in school-aged children: coproscopic survey. J Parasit Dis. 2022, 46, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Gong, P.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X. Changes of Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Patients with Pentatrichomonas Hominis Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 961974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withworth, J. Unpasteurized spinach drink tied to increase of cryptosporidium cases. Food Safety News. 2019. Available online: https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2019/12/unpasteurized-spinach-drink-tied-to-increase-of-cryptosporidium-cases/.

- Technical Committee: ISO/TC 34/SC 9. Microbiology of the food chain. Detection and enumeration of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in fresh leafy green. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63252.html (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. Ending the neglect to attain the sustainable development goals: a global strategy on water, sanitation and hygiene to combat neglected tropical diseases, 2021–2030. World Health Organization. 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/340240 (accessed on February 2024).

| Infectious agent | Dietary infection sources in cases and outbreaks* |

|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Drinking water, unpasteurized or re-contaminated pasteurized milk, meat, dairy foods, dishes prepared outdoors, barbecued foods, raw foods, raw vegetables, raw fruits, unpasteurized drinks, apple juice, raw shellfish [9,99,100,107,108,110,113,121,124,125,126,127,129,130,131,132,133,266] |

| Entamoeba spp. | Drinking water, alcoholic fermented sap of the Palmyra toddy [7,162] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Raw vegetables, fruits, raw or undercooked meats, unpasteurized milk, raw cow’s milk cheese, raw or undercooked crustaceans or shellfish, whale meat, drinking water [13,41,43,49,50,64,167,169,170,171,172,173] |

| Giardia intestinalis | Drinking water, fresh produce, composite ready to eat food, canned salmon, raw oysters, ice cream, noodle salad, chicken salad, dairy products, sandwiches, tripe soup, unpasteurized milk, shellfish, unidentified foods [177,178,179,182,194,195] |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | açaí juice, sugar cane juice, palm, guanabana, guava, milpesillo, majo, mango, mandarin, orange juices, raw meat [11,197] |

| Balantioides coli | None reported |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis | berries, cilantro, basil, lettuce, ready-to-eat bagged salads, sugar snap peas [6,207,208,209] |

| Cystoisospora belli | None reported |

| Sarcocystis spp. | Beef, pork, venison, whale meat [8,173,228] |

| Blastocystis hominis | None reported |

| Endolimax nana | None reported |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | None reported |

| Pentatrichomonas hominis | None reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |