Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Enrollment Procedures

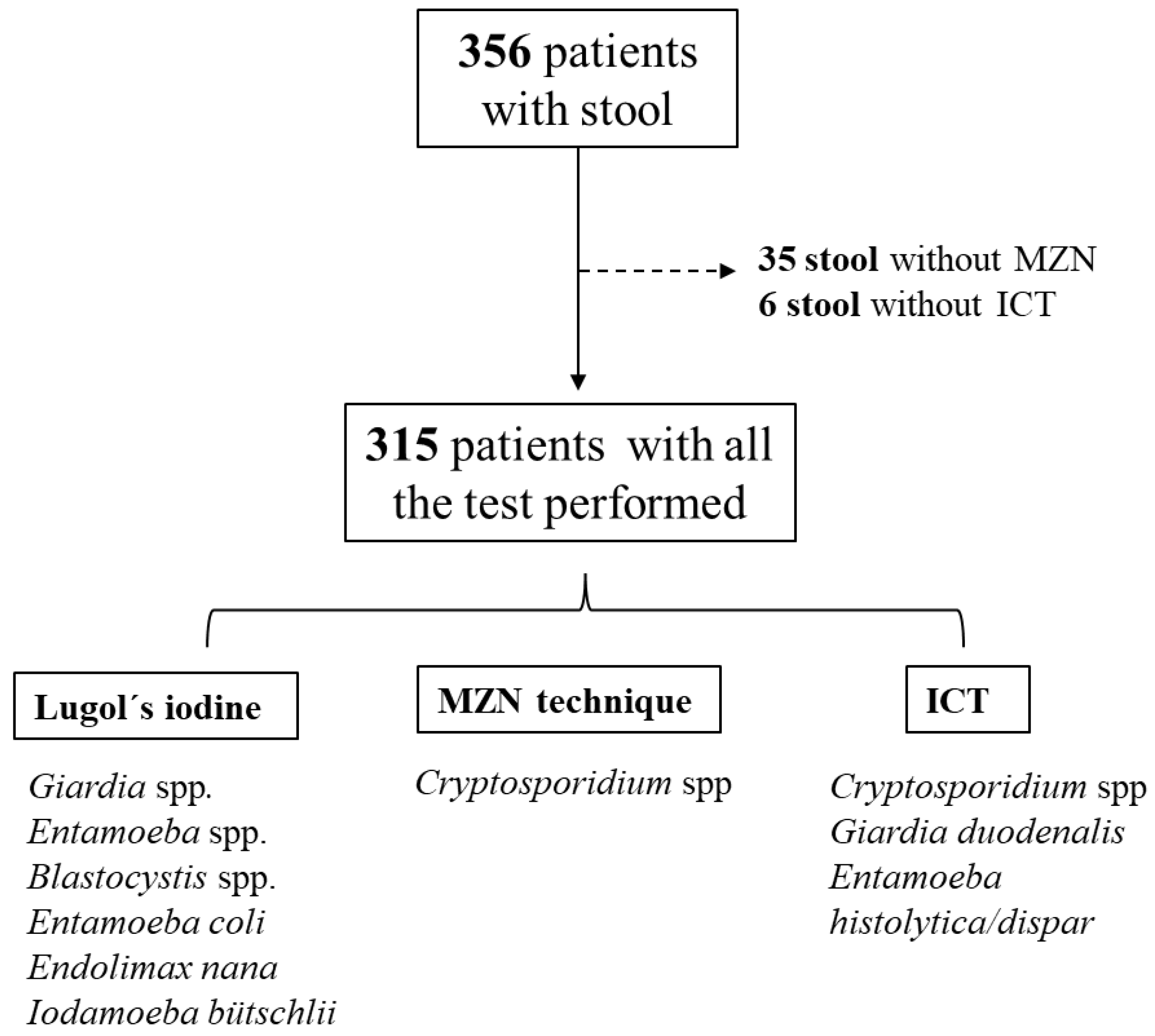

2.3. Stool Specimen Processing, Staining and Microscopy

- -

- Lugol’s iodine solution: Each fecal specimen was analyzed using Lugol’s iodine solution to enhance the diagnostic accuracy of direct microscopy of wet mounts, looking for Giardia spp., Entamoeba spp., Blastocystis spp., Entamoeba coli, Endolimax nana, and Iodamoeba bütschlii. We did not perform a concentration technique before Lugol’s iodine solution because some studies reported a non-significant difference in sensitivity between direct examination and the formalin ether concentration technique [21]. Lugol’s iodine stains glycogen and other cytoplasmic structures, enhancing the visualization of protozoan cysts and trophozoites. Giardia cysts typically appear oval with internal nuclei and axonemes [22], while Entamoeba cysts show characteristic nuclear structures and chromatoid bodies, and the trophozoite could appear with red blood cells in the cytoplasm, what allow it to be sometimes distinguished from the commensal E. dispar [23]. Commensal protozoa, including Blastocystis, display variable shapes and internal granularity, whereas E. coli, E. nana, and I. bütschlii cysts can be distinguished by their size, number of nuclei, and cytoplasmic inclusions. [24]. This technique is simple, fast and useful, and provides a cost-effective approach for preliminary identification of intestinal protozoa in laboratory settings.

- -

- Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain (MZN): Briefly, each stool sample was homogenized with a spatula and, taking a small amount at the edge, spread elliptically over the central part of a slide. The slide was heat-fixed and placed on a support to facilitate washing, then coated with phenolated fuchsin for 5 minutes and gently rinsed with running water to remove the reagent. The slide was incubated in 3% acid alcohol for 1 minute, rinsed, incubated in methylene blue as a contrast stain for 5 minutes, rinsed, and allowed to dry at room temperature on paper towels. Once dry, a drop of immersion oil was added to the center of the extended slide for microscopic observation with the 100X objective. To assure high-quality microscopy results, the two study staff microscopists were trained by the Cayetano Heredia University’s Microbiology Service and Selva Amazonica Civil Association before study initiation.

- -

- Crypto + Giardia + Entamoeba ICT (CerTest ®, Certest Biotec, Zaragoza, Spain): This one step combo card test is a colored chromatographic immunoassay for the simultaneous qualitative detection of Cryptosporidium spp. (via Anti-Crypto MAb (clone CR23) and Inactivated Cryptosporidium parvum antigen (native extract)), Giardia duodenalis and Entamoeba histolytica/dispar in stool samples. It is used by mixing a small amount of stool sample with the provided buffer, applying the mixture to the test cassette, and waiting the specified time (usually 10–15 minutes). The appearance of lines in the result window indicates the presence of antigens from Cryptosporidium spp. and/or Giardia duodenalis and/or Entamoeba histolytica/dispar.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Cohort

3.2. Stool Diagnosis

3.2.1. Prevalence of Giardia, Entamoeba, Blastocystis, and Commensal Pathogens

3.2.2. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp.

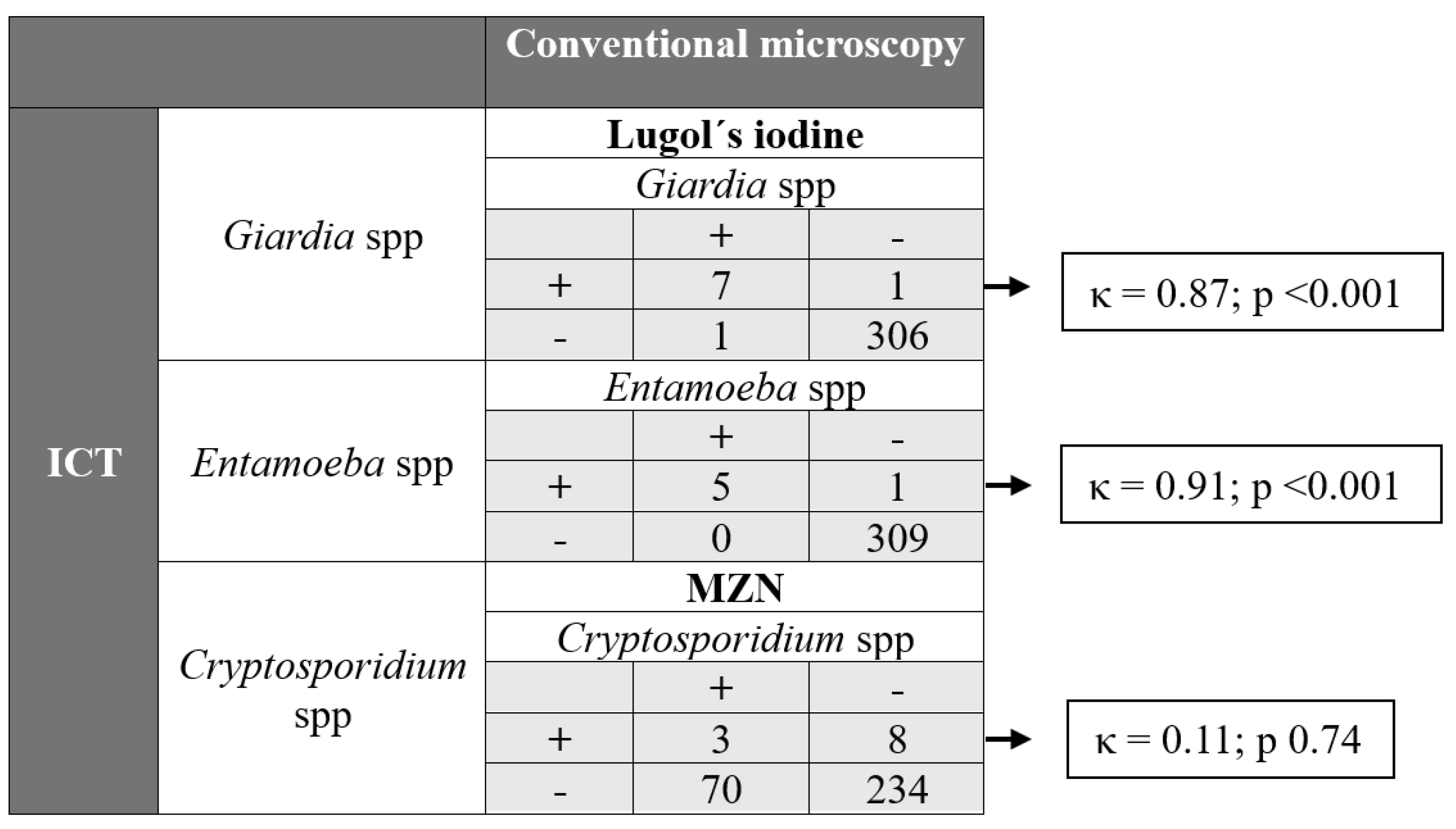

3.2.3. Evaluation of Diagnostic Test Agreement

3.2.4. Prevalence of Co-Infection with Giardia spp., Entamoeba spp., Cryptosporidium spp. and Blastocystis spp.

3.2.5. Epidemiological Risk Factors Associated with Pathogenic Intestinal Protozoa Positivity

3.2.6. Prevalence Pattern of Protozoa in People Referring Diarrhea

4. Discussion

4.1. Cryptosporidium spp. Prevalence in Stool

4.2. Giardia and Entamoeba spp. Prevalence in Stool

4.3. Blastocystis, and Commensal Pathogens Prevalence in Stool

4.4. Risk Factors for Pathogenic Intestinal Protozoa Acquisition

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| PWH | People with HIV |

| MZN | Modified Ziehl Neelsen staining |

| ICT | Immunochromatography |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| AOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| IQRs | Interquartile Ranges |

| N/A | Not Applicable. |

| ART | Anti-retroviral therapy. |

References

- Zorbozan O, Quliyeva G, Tunalı V, Özbilgin A, Turgay N, Gökengin AD Intestinal Protozoa in Hiv-Infected Patients: A Retrospective Analysis. Turk. J. Parasitol. 2018, 42, 187–190. [CrossRef]

- Bednarska, M.; Jankowska, I.; Pawelas, A.; Piwczyńska, K.; Bajer, A.; Wolska-Kuśnierz, B.; Wielopolska, M.; Welc-Falęciak, R. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium, Blastocystis, and Other Opportunistic Infections in Patients with Primary and Acquired Immunodeficiency. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 2869–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, P.; Maleki, A.; Sadeghi, S.; Shahmoradi, B.; Ghahremani, E. Prevalence of Intestinal Protozoa Infections and Associated Risk Factors among Schoolchildren in Sanandaj City, Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2017, 12, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Darlan, D.M.; Rozi, M.F.; Nurangga, M.A.; Amsari, L.C. Cryptosporidium Sp. and Blastocystishominis Findings: A Cross-Sectional Study among Healthy Versus Immunocompromised Individuals. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 2346–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerace, E.; Lo Presti, V.D.M.; Biondo, C. Cryptosporidium Infection: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Differential Diagnosis. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 9, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV. National Institutes of Health, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at Https://Clinicalinfo.Hiv.Gov/En/Guidelines/Adult-and-Adolescent-Opportunistic-Infection. Accessed May 2025 [I-1, I-6].

- Darlan, D.M.; Rozi, M.F.; Nurangga, M.A.; Amsari, L.C. Cryptosporidium Sp. and Blastocystishominis Findings: A Cross-Sectional Study among Healthy Versus Immunocompromised Individuals. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 2346–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, D.-A.T.; Moonah, S.N.; Kotloff, K.L. Burden of Disease from Cryptosporidiosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 25, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghamolaie, S.; Rostami, A.; Fallahi, S.; Tahvildar Biderouni, F.; Haghighi, A.; Salehi, N. Evaluation of Modified Ziehl-Neelsen, Direct Fluorescent-Antibody and PCR Assay for Detection of Cryptosporidium Spp. in Children Faecal Specimens. J. Parasit. Dis. Off. Organ Indian Soc. Parasitol. 2016, 40, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, T.E.; Ohl, C.A.; Thomas, E.; Subramanian, G.; Keiser, P.; Moore, T.A. Treatment of Patients with Refractory Giardiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S. Multiple Amoebic Liver Abscess As Initial Manifestation in Hiv Sero-Positive Male. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2015, 9, OD04–OD05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidvand, Z.; Khazaei, S.; Amiri, M.; Taherkhani, H.; Mirzaei, A. Worldwide Prevalence of Emerging Parasite Blastocystis in Immunocompromised Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 152, 104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña-Losada C, et al. Características Clínicas y Epidemiológicas de La Parasitación Intestinal Por Blastocystis Hominis. Rev Clin Esp. 2018;218(3):115-120. [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, I.; Poirier, P.; Viscogliosi, E.; Dionigia, M.; Texier, C.; Delbac, F.; Alaoui, H.E. Blastocystis, an Unrecognized Parasite: An Overview of Pathogenesis and Diagnosis. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2013, 1, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa Aranzales, A.F.; Radon, K.; Froeschl, G.; Pinzón Rondón, Á.M.; Delius, M. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Intestinal Parasitic Infections in Pregnant Women Residing in Three Districts of Bogotá, Colombia. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos, L.A.; Gotuzzo, E. Intestinal Protozoan Infections in the Immunocompromised Host. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 26, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárcamo, C.; Hooton, T.; Wener, M.H.; Weiss, N.S.; Gilman, R.; Arevalo, J.; Carrasco, J.; Seas, C.; Caballero, M.; Holmes, K.K. Etiologies and Manifestations of Persistent Diarrhea in Adults with HIV-1 Infection: A Case-Control Study in Lima, Peru. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García C, Rodríguez E, Do N, López de Castilla D, Terashima A, Gotuzzo E. Parasitosis Intestinal En El Paciente Con Infección VIH-SIDA [Intestinal Parasitosis in Patients with HIV-AIDS]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2006;26(1):21-24.

- Vergaray, S.; Paima-Olivari, R.; Runzer-Colmenares, F.M. Parasitosis intestinal y estado inmunológico en pacientes adultos con infección por VIH del Centro Médico Naval "Cirujano Mayor Santiago Távara. Horiz. Méd. Lima 2019, 19, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Prevención y Control de Enfermedades. Situación Epidemiológica Del VIH - Sida En El Perú. Boletín VIH, II Trimestre - 2024. Available at: Https://Www.Dge.Gob.Pe/Epipublic/Uploads/Vih-Sida/Vih-Sida_20246_16_153419.Pdf. Consultado El 20 de Febrero de 2025.

- Wahdini, S.; Putra, V.P.; Sungkar, S. The Prevalence of Intestinal Protozoan Infections among Children in Southwest Sumba Based on the Type of Water Sources. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 53, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calchi L, C. Martinella, Acurero E, et al. Comparación de Técnicas Parasitológicas. Kasmera, 42(1): 32-40, Enero-Junio 2014. ISSN 0075-5222.

- Botero D, Restrepo M. Parasitosis Humanas. 5.a Edición. Medellín, Corporación Para Investigaciones Biológicas, 2012: 38-56.

- Flórez, A.C.; García, D.A.; Moncada, L.; Beltrán, M. Prevalencia de microsporidios y otros parásitos intestinales en pacientes con infección por VIH, Bogotá, 2001. Biomédica 2003, 23, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, R.G. Two-Sided Confidence Intervals for the Single Proportion: Comparison of Seven Methods. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, C.A.; Kaplan, J.E.; Masur, H.; Pau, A.; Holmes, K.K. ; CDC; National Institutes of Health; Infectious Diseases Society of America Treating Opportunistic Infections among HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm. Rep. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recomm. Rep. 2004, 53, 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cama, V.A.; Bern, C.; Sulaiman, I.M.; Gilman, R.H.; Ticona, E.; Vivar, A.; Kawai, V.; Vargas, D.; Zhou, L.; Xiao, L. Cryptosporidium Species and Genotypes in HIV-Positive Patients in Lima, Peru. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2003, 50 Suppl, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankwa, K.; Nuvor, S.V.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Feglo, P.K.; Mutocheluh, M. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium Infection and Associated Risk Factors among HIV-Infected Patients Attending ART Clinics in the Central Region of Ghana. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Munoz, M.; Gómez, N.; Tabares, J.; Segura, L.; Salazar, Á.; Restrepo, C.; Ruíz, M.; Reyes, P.; Qian, Y.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Giardia, Blastocystis and Cryptosporidium among Indigenous Children from the Colombian Amazon Basin. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.A.; Quattrocchi, A.; Elzagawy, S.M.; Karanis, P.; Gad, S.E.M. Diagnostic Performance of Toluidine Blue Stain for Direct Wet Mount Detection of Cryptosporidium Oocysts: Qualitative and Quantitative Comparison to the Modified Ziehl-Neelsen Stain. Diagn. Basel Switz. 2023, 13, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Stool Specimens – Staining Procedures [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023 Aug 31 [Cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: Https://Www.Cdc.Gov/Dpdx/Diagnosticprocedures/Stool/Staining.Html.

- Omoruyi, B.E.; Nwodo, U.U.; Udem, C.S.; Okonkwo, F.O. Comparative Diagnostic Techniques for Cryptosporidium Infection. Mol. Basel Switz. 2014, 19, 2674–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafari, R.; Rafiei, A.; Tavalla, M.; Moradi Choghakabodi, P.; Nashibi, R.; Rafiei, R. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium Species Isolated from HIV/AIDS Patients in Southwest of Iran. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 56, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cama, V.A.; Bern, C.; Roberts, J.; Cabrera, L.; Sterling, C.R.; Ortega, Y.; Gilman, R.H.; Xiao, L. Cryptosporidium Species and Subtypes and Clinical Manifestations in Children, Peru - Volume 14, Number 10—October 2008 - Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal - CDC. [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, F.; Shams, M.; Sadrebazzaz, A.; Shamsi, L.; Omidian, M.; Asghari, A.; Hassanipour, S.; Salemi, A.M. Global Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Diarrheagenic Giardia Duodenalis in HIV/AIDS Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 160, 105202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peréz Cordón, G.; Cordova Paz Soldan, O.; Vargas Vásquez, F.; Velasco Soto, J.R.; Sempere Bordes, L.; Sánchez Moreno, M.; Rosales, M.J. Prevalence of Enteroparasites and Genotyping of Giardia Lamblia in Peruvian Children. Parasitol. Res. 2008, 103, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chincha L, O.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A.; Samalvides C, F.; Soto A, L.; Gotuzzo H, E.; Terashima I, A. Parasite Intestinal Infection and Factors Associated with Coccidian Infection in Adults at Public Hospital in Lima, Peru. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2009, 26, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannella, A.R.; Suputtamongkol, Y.; Wongsawat, E.; Cacciò, S.M. A Retrospective Molecular Study of Cryptosporidium Species and Genotypes in HIV-Infected Patients from Thailand. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo, F.E.; Singh, G.; Reddy, P.; Bux, F.; Stenström, T.A. Efficiency of Chlorine and UV in the Inactivation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in Wastewater. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0216040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Xiao, S.; An, W.; Sang, C.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Yang, M. Co-Infection Risk Assessment of Giardia and Cryptosporidium with HIV Considering Synergistic Effects and Age Sensitivity Using Disability-Adjusted Life Years. Water Res. 2020, 175, 115698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Cabrera, M.X.; Maguiña, J.L.; Gonzales-Huerta, L.; Panduro-Correa, V.; Dámaso-Mata, B.; Pecho-Silva, S.; Navarro-Solsol, A.C.; Rabaan, A.A.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Arteaga-Livias, K. Blastocystis Species and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Peruvian Adults Attended in a Public Hospital. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 53, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chincha, O.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A.; Samalvides, F.; Soto, L.; Gotuzzo, E.; Terashima, A. Infecciones parasitarias intestinales y factores asociados a la infección por coccidias en pacientes adultos de un hospital público de Lima, Perú [Parasite intestinal infection and factors associated with coccidian infection in adults at public hospital in Lima, Peru] [published correction appears in Rev Chilena Infectol. 2009 Dec;26(6):571]. Rev Chil. Infectol 2009, 26, 440–444. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanelli Sulekova, L.; Gabrielli, S.; Furzi, F.; Milardi, G.L.; Biliotti, E.; De Angelis, M.; Iaiani, G.; Fimiani, C.; Maiorano, M.; Mattiucci, S.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Blastocystis Subtypes in HIV-Positive Patients and Evaluation of Risk Factors for Colonization. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Sánchez, R.S.; Ascuña-Durand, K.; Ballón-Echegaray, J.; Vásquez-Huerta, V.; Martínez-Barrios, E.; Castillo-Neyra, R. Socio-Demographic Determinants Associated with Blastocystis Infection in Arequipa, Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 104, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntonifor, N.H.; Tamufor, A.S.W.; Abongwa, L.E. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites and Associated Risk Factors in HIV Positive and Negative Patients in Northwest Region, Cameroon. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleke, D.G.; Ali, A.; Bisetegn, H.; Andualem, M. Intestinal Parasitic Infections and Associated Factors among People Living with HIV Attending Dessie Referral Hospital, Dessie Town, North-East Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. AIDS Res. Ther. 2022, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahn Junior, E.P.; Oliveira, E.C. de; Barbosa, M.J.; Mareco, T.C. de S.; Brígido, H.A.; Nahn Junior, E.P.; Oliveira, E.C. de; Barbosa, M.J.; Mareco, T.C. de S.; Brígido, H.A. Protocolo Brasileño Para Infecciones de Transmisión Sexual 2020: Infecciones Entéricas de Transmisión Sexual. Epidemiol. E Serviços Saúde 2021, 30. [CrossRef]

- Sorvillo, F.; Mori, K.; Sewake, W.; Fishman, L. Sexual Transmission of Strongyloides Stercoralis among Homosexual Men. Sex. Transm. Infect. 1983, 59, 342–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohebali, M.; Yimam, Y.; Woreta, A. Cryptosporidium Infection among People Living with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathog. Glob. Health 2020, 114, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.-G.; Wang, T.-P.; Lv, S.; Wang, F.-F.; Guo, J.; Yin, X.-M.; Cai, Y.-C.; Dickey, M.K.; Steinmann, P.; Chen, J.-X. HIV and Intestinal Parasite Co-Infections among a Chinese Population: An Immunological Profile. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2013, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables |

Pathogenic protozoa positive (N = 92) |

Pathogenic Protozoa negative (N = 223) |

OR | p |

| Male, % (n/N) | 60.9 (56/92) | 64.6 (144/223) | 0.85 | 0.54 |

| Age, mean±SD, years | 42 ± 12 | 41 ± 12 | 1.26 | 0.39 |

| Hospital attended, % (n/N) | ||||

| Hospital of Iquitos | 26.1 (24/92) | 10.8 (24/223) | 2.93 | <0.001 |

| Regional Hospital of Loreto | 73.9 (68/92) | 89.2 (199/223) | ||

| Residence, % (n/N) | ||||

| Iquitos district | 33.7 (31/92) | 34.5 (77/223) | N/A | 0.58 |

| Punchana district | 29.3 (27/92) | 25.1 (56/223) | ||

| Belen district | 15.2 (14/92) | 15.7 (35/223) | ||

| San Juan district | 16.3 (15/92) | 22.0 (49/223) | ||

| Outside of Iquitos | 5.4 (5/92) | 2.7 (6/223) | ||

| Occupation, % (n/N) | ||||

| Unemployed or student (yes) | 38.1 (35/92) | 46.2 (103/223) | N/A | 0.19 |

| Cattle, agriculture or construction (yes) | 16.3 (15/92) | 15.2 (34/223) | ||

| Craft work (yes) | 4.3 (4/92) | 4.5 (10/223) | ||

| Intellectual worka(yes) | 15.2 (14/92) | 6.7 (15/223) | ||

| Self-employment (yes) | 26.1 (24/92) | 27.4 (61/223) | ||

| Education, % (n/N) | ||||

| None (yes) | 3.3 (3/92) | 2.7 (6/223) | N/A | 0.31 |

| Attended primary school (yes) | 22.2 (20/92) | 14.3 (32/223) | ||

| Attended secondary school (yes) | 48.9 (45/92) | 59.2 (132/223) | ||

| Attended university (yes) | 26.1 (24/92) | 23.8 (53/223) | ||

| Epidemiological risk factors, % (n/N) | ||||

| Lives with dogs/cats/farm animals (yes) | 69.6 (64/92) | 70.0 (156/223) | 0.98 | 0.94 |

| Walks barefoot (yes) | 33.7 (31/92) | 26.0 (58/223) | 1.45 | 0.17 |

| Resid in rural locationb (yes) | 30.4 (28/92) | 33.6 (75/223) | 0.86 | 0.58 |

| Lives in a house made of wood/leaves (yes) | 44.6 (41/92) | 48.9 (109/223) | 0.84 | 0.49 |

| Alcohol or tobacco consumption (yes) | 55.4 (51/92) | 51.6 (115/223) | 1.17 | 0.53 |

| Comorbidity, % (n/N) | ||||

| Diabetes or high blood pressure (yes) | 6.5 (6/92) | 7.6 (17/223) | 0.85 | 0.73 |

| Other cardiovascular disease (yes) | 1.0 (1/92) | 3.6 (8/223) | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| Digestive disease (yes) | 8.7 (8/92) | 5.4 (12/223) | 1.68 | 0.27 |

| Urinary disease (yes) | 3.3 (3/92) | 0.9 (2/223) | 3.73 | 0.13 |

| Dermatological disease (yes) | 1.0 (1/92) | 0.4 (1/223) | 2.44 | 0.52 |

| Other (yes) | 0.0 (0/92) | 0.9 (2/223) | 1.42 | 0.36 |

| Previous infections, % (n/N) | ||||

| Tuberculosis (yes) | 20.7 (19/92) | 22.0 (49/223) | 0.92 | 0.80 |

| Intestinal parasitosis (yes) | 18.5 (17/92) | 9.0 (20/223) | 2.30 | 0.017 |

| Gonorrhea (yes) | 19.6 (18/92) | 10.3 (23/223) | 2.12 | 0.026 |

| Syphilis (yes) | 18.5 (17/92) | 13.5 (30/223) | 1.46 | 0.26 |

| Chronic hepatitis (yes) | 8.7 (8/92) | 5.8 (13/223) | 1.54 | 0.35 |

| Cerebral toxoplasmosis (yes) | 0.0 (0/92) | 4.9 (11/223) | 1.43 | 0.038 |

| Symptoms, % (n/N) | ||||

| Cough, cold symptoms (yes) | 14.1 (13/92) | 8.1 (18/223) | 1.87 | 0.10 |

| Fever (yes) | 1.1 (1/92) | 2.2 (5/223) | 0.48 | 0.68 |

| Diarrhea (yes) | 26.1 (24/92) | 19.7 (44/223) | 1.44 | 0.21 |

| Frequency of diarrhea, % (n/N) | ||||

| No diarrhea | 73.9 (68/92) | 80.3 (179/223) | N/A | 0.014 |

| Once a month | 16.3 (15/92) | 16.6 (37/223) | ||

| Once a week | 2.2 (2/92) | 2.2 (5/223) | ||

| Once a day | 7.6 (7/92) | 0.9 (2/223) | ||

| Risk group, % (n/N) | ||||

| Heterosexual | 70.9 (61/86) | 79.0 (166/210) | N/A |

0.046 |

| Homosexual | 27.9 (24/86) | 15.7 (33/210) | ||

| Transexual/Bisexual | 1.2 (1/86) | 5.2 (11/210) | ||

|

6.5 (6/92) | 5.8 (13/223) | ||

| HIV acquisition, % (n/N) | ||||

| Sexual | 92.4 (85/92) | 88.8 (198/223) | N/A | 0.64 |

| Vertical | 0.0 (0/92) | 0.9 (2/223) | ||

| Parenteral | 0.0 (0/92) | 0.4 (1/223) | ||

| Unknown | 7.6 (7/92) | 9.9 (22/223) | ||

| CD4+ nadir, median (IQR), /uL | 234 (131, 369) | 261 (117, 378) | N/A | 0.84 |

|

46.7 (43/92) | (92/223) | ||

| Current CD4+, median (IQR), /uL | 427 (265, 574) | 431 (293, 592) | N/A | 0.61 |

|

30.4 (28/92) | 31.4 (70/223) | ||

| Current CD4+ < 200/ml, % (n/N), /ml | 18.8 (12/64) | 9.8 (15/153) | 2.12 | 0.069 |

|

30.4 (28/92) | 31.4 (70/223) | ||

|

Uncontrolled HIV viral load, (> 20 copies/ml), % (n/N) |

29.4 (25/85) | 18.4 (40/217) | 1.84 | 0.037 |

|

7.6 (7/92) | 2.7 (6/223) | ||

| Poor ART adherence ≤ 95%, % (n/N) | 14.8 (12/81) | 14.2 (26/183) | 1.05 | 0.90 |

|

12.0 (11/92) | 17.9 (40/223) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).