Submitted:

18 March 2024

Posted:

22 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

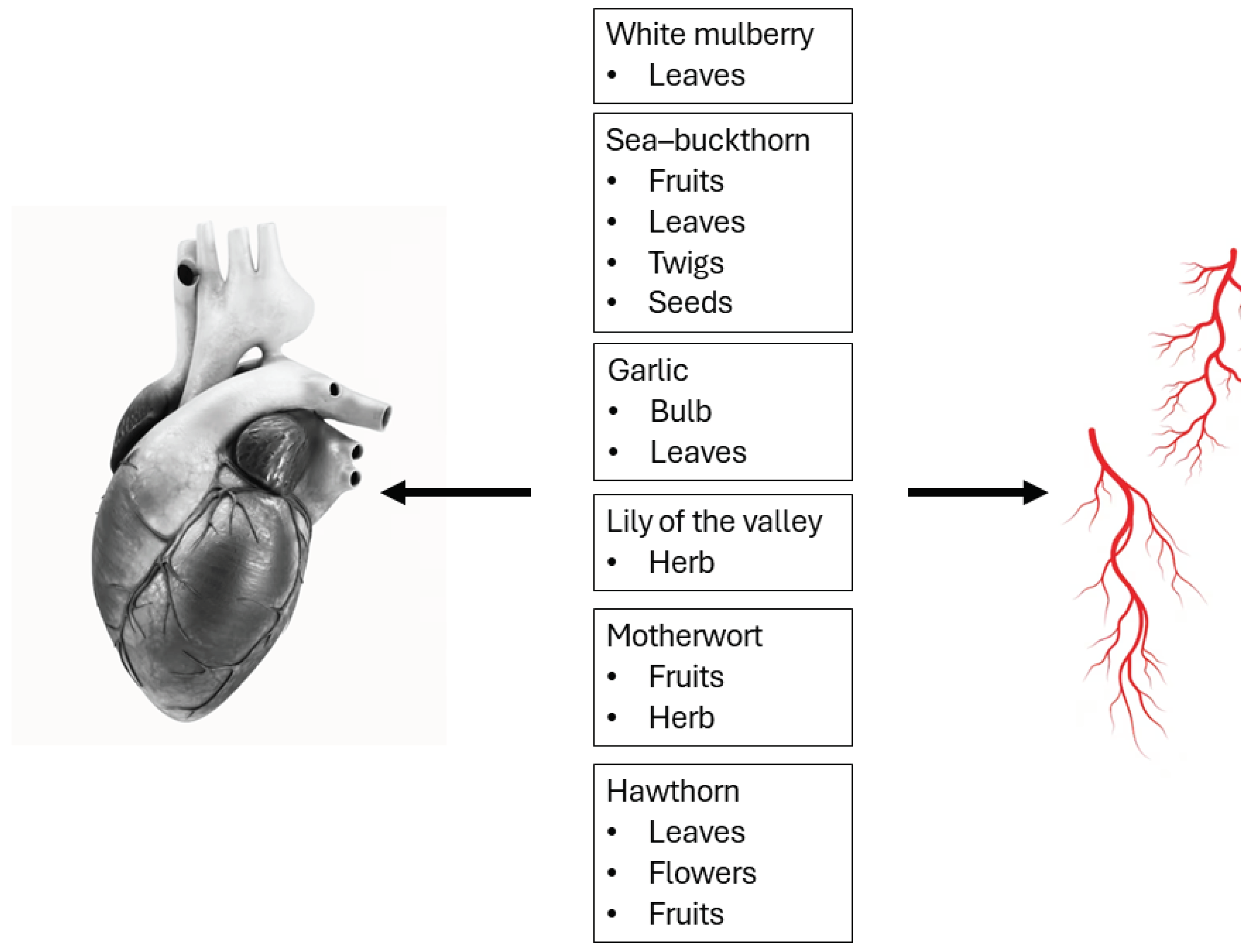

2. White Mulberry

3. Sea–Buckthorn

4. Garlic

5. Lily of the Valley

6. Motherwort

7. Hawthorn

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sánchez-Salcedo, E.M.; Amorós, A.; Hernández, F.; Martínez, J.J. Physicochemical properties of white (Morus alba) and black (Morus nigra) mulberry leaves, a new food supplement. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 5, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, B.; Zahiruddin, S.; Basist, P.; Irfan, M.; Abass, S.; Ahmad, S. Metabolomic Profiling and Identification of Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Compounds from Leaves of Different Varieties of Morus alba Linn Grown in Kashmir. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 24317–24328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryn-Rynko, A.; Bazylak, G.; Olszewska-Slonina, D. New potential phytotherapeutics obtained from white mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaipitakwong, T.; Numhom, S.; Aramwit, P. Mulberry leaves and their potential effects against cardiometabolic risks: A review of chemical compositions, biological properties and clinical efficacy. Pharm. Biol. 2018, 56, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Razali, U.H.M.; Saikim, F.H.; Mahyudin, A.; Noor, N.Q.I.M. Morus alba L. Plant: Bioactive Compounds and Potential as a Functional Food Ingredient. Foods 2021, 10, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Qian, Z.; Wu, P.; Shen, M.; Li, L.; Zhao, W. 1-Deoxynojirimycin from mulberry leaves changes gut digestion and microbiota composition in geese. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5858–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memete, A.R.; Timar, A.V.; Vuscan, A.N.; (Groza), F.M.; Venter, A.C.; Vicas, S.I. Phytochemical Composition of Different Botanical Parts of Morus Species, Health Benefits and Application in Food Industry. Plants 2022, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, B.; Parveen, R.; Zahiruddin, S.; Khan, M.U.; Mohapatra, S.; Ahmad, S. Nutritional constituents of mulberry and their potential applications in food and pharmaceuticals: A review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3909–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhumitha, S.; Indhuleka, A. Cardioprotective effect of Morus alba L. leaves in isoprenaline induced rats. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 1475–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nade, V.S.; Kawale, L.A.; Bhangale, S.P.; Wale, Y.B. Cardioprotective and antihypertensive potential of Morus alba L in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction and renal artery ligation-induced hypertension. J. Nat. Remedies. 2013, 13, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizzo, A.; Ambrosio, M.; Damato, A.; Madonna, M.; Storto, M.; Capocci, L.; Campiglia, P.; Sommella, E.; Trimarco, V.; Rozza, F.; et al. Morus alba extract modulates blood pressure homeostasis through eNOS signaling. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2304–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-S.; Ji, H.D.; Rhee, M.H.; Sung, Y.-Y.; Yang, W.-K.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.-K. Antiplatelet Activity ofMorus albaLeaves Extract, Mediated via Inhibiting Granule Secretion and Blocking the Phosphorylation of Extracellular-Signal-Regulated Kinase and Akt. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 639548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Choi, D.H.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, H.Y.; Kwon, T.O.; Kang, D.G.; Lee, H.S. Hypotensive, Hypolipidemic, and Vascular Protective Effects of Morus alba L. in Rats Fed an Atherogenic Diet. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2011, 39, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jiang, W.; Bai, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Tang, H.; Duan, W.; et al. Study on active components of mulberry leaf for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular complications of diabetes. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 83, 104549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-Y.; Wu, Y.-L.; Yu, M.-H.; Hung, T.-W.; Chan, K.-C.; Wang, C.-J. Mulberry Leaf and Neochlorogenic Acid Alleviates Glucolipotoxicity-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inhibits Proliferation/Migration via Downregulating Ras and FAK Signaling Pathway in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stochmal, A.; Rolnik, A.; Skalski, B.; Zuchowski, J.; Olas, B. Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Activity of Isorhamnetin and Its Derivatives Isolated from Sea Buckthorn Berries, Measured in Whole Blood. Molecules 2022, 27, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalski, B.; Rywaniak, J.; Żuchowski, J.; Stochmal, A.; Olas, B. The changes of blood platelet reactivity in the presence of Elaeagnus rhamnoides (L.) A. Nelson leaves and twig extract in whole blood. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleszko, M.; Wojdyło, A.; Rudzińska, M.; Oszmiański, J.; Golis, T. Analysis of Lipophilic and Hydrophilic Bioactive Compounds Content in Sea Buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides L.) Berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 4120–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sławińska, N.; Żuchowski, J.; Stochmal, A.; Olas, B. Extract from Sea Buckthorn Seeds—A Phytochemical, Antioxidant, and Hemostasis Study; Effect of Thermal Processing on Its Chemical Content and Biological Activity In Vitro. Nutrients 2023, 15, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B.; Żuchowski, J.; Lis, B.; Skalski, B.; Kontek, B.; Grabarczyk, Ł.; Stochmal, A. Comparative chemical composition, antioxidant and anticoagulant properties of phenolic fraction (a rich in non-acylated and acylated flavonoids and non-polar compounds) and non-polar fraction from Elaeagnus rhamnoides (L.) A. Nelson fruits. Food Chem. 2018, 247, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.; Tian, Y.; Wei, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, T. Flavone of Hippophae (H-flavone) lowers atherosclerotic risk factors via upregulation of the adipokine C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein 6 (CTRP6) in macrophages. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2019, 83, 2000–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, T.; Destandau, E.; Le Floch, G.; Lucchesi, M.E.; Elfakir, C. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and phytochemical investigations of sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides L.) leaf, stem, root and seed. Food Chemistry 2012, 131, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupak, R.; Hrnkova, J.; Simonova, N.; Kovac, J.; Ivanisova, E.; Kalafova, A.; Schneidgenova, M.; Prnova, M.S.; Brindza, J.; Tokarova, K.; et al. The consumption of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) effectively alleviates type 2 diabetes symptoms in spontaneous diabetic rats. Res. Veter- Sci. 2022, 152, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.A.; Bordean, D.M.; Radulov, I.; Moruzi, R.F.; Hulea, C.I.; Orășan, S.A.; Dumitrescu, E.; Muselin, F.; Herman, H.; Brezovan, D.; et al. Sea Buckthorn and Grape Antioxidant Effects in Hyperlipidemic Rats: Relationship with the Atorvastatin Therapy. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 1736803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Suo, Y.; Chen, D.; Tong, L. Protection against vascular endothelial dysfunction by polyphenols in sea buckthorn berries in rats with hyperlipidemia. Biosci. Trends 2016, 10, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, A.K.; Raghavan, S.K.; Khanum, F.; Shivanna, N.; Singh, B.A. Effect of Sea Buckthorn Leaves Based Herbal Formulation on Hexachlorocyclohexane—Induced Oxidative Stress in Rats. J. Diet. Suppl. 2008, 5, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, R.; Raghuwanshi, P.; Koul, A.L.; Rastogi, A.; Khajuria, P.; Wahid, A.; Kour, S. Hepatoprotective effect of seabuckthorn leaf-extract in lead acetate-intoxicated Wistar rats. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 45, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, D.; Kumar, M.Y.; Verma, S.K.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, S.N. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities of phenolic rich fraction of Seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) leaves. Food Chem. Toxicol. an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2011, 49, 2422–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Long, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X. Effect of seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides ssp. sinensis) leaf extract on the swimming endurance and exhaustive exercise-induced oxidative stress of rats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 92, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saber Batiha, G.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.; Wasef, L.G.; Elewa, Y.H.; Al-Sagan, A.A.; El-Hack, A.; Taha, M.E.; Abd-Elhakim, Y.M.; Prasad Devkota, H. Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, I.; de Paola, M.; Torres-Palazzolo, C.; Camargo, A.; Ferder, L.; Manucha, W.; Castro, C. Effect of Garlic’s Active Constituents in Inflammation, Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2020, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlinghaus, J.; Albrecht, F.; Gruhlke, M.C.H.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Slusarenko, A.J. Allicin: Chemistry and Biological Properties. Molecules 2014, 19, 12591–12618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L.D.; Hunsaker, S.M. Allicin Bioavailability and Bioequivalence from Garlic Supplements and Garlic Foods. Nutrients 2018, 10, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Zhang, C.; Sheng, Y.; Zhao, C.; He, X.; Xu, W.; Huang, K.; Luo, Y. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effect of S-allyl-cysteine sulfoxide (alliin) in DIO mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, S.A.; Dhir, B.; Kapoor, R.; Fatima, S.; Mahmooduzzafar, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Mujib, A. Alliin obtained from leaf extract of garlic grown underin situconditions possess higher therapeutic potency as analyzed in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, T.; Quine, S.D. Preventive effect of S-allyl cysteine sulfoxide (alliin) on cardiac marker enzymes and lipids in isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2006, 58, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Gloria, J.L.; Arellano-Buendía, A.S.; Juárez-Rojas, J.G.; García-Arroyo, F.E.; Argüello-García, R.; Sánchez-Muñoz, F.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Osorio-Alonso, H. Cellular Mechanisms Underlying the Cardioprotective Role of Allicin on Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marón, F.J.M.; Camargo, A.B.; Manucha, W. Allicin pharmacology: Common molecular mechanisms against neuroinflammation and cardiovascular diseases. Life Sci. 2020, 249, 117513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaviono, Y.H.; Amadis, M.R.; Al-Farabi, M.J. High Dose Allicin with Vitamin C Improves EPCs Migration from the Patient with Coronary Artery Disease. Pharmacogn. J. 2020, 12, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkayam, A.; Peleg, E.; Grossman, E.; Shabtay, Z.; Sharabi, Y. Effects of allicin on cardiovascular risk factors in spontaneously hypertensive rats. The Israel Medical Association journal IMAJ 2013, 15, 170–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Torres-Palazzolo, C.; de Paola, M.; Quesada, I.; Camargo, A.; Castro, C. 2-Vinyl-4H-1,3-Dithiin, a Bioavailable Compound from Garlic, Inhibits Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Proliferation and Migration by Reducing Oxidative Stress. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Paramesha, B.; Kumar, Y.; Tariq, U.; Arava, S.K.; Banerjee, S.K. Allylmethylsulfide, a Sulfur Compound Derived from Garlic, Attenuates Isoproterenol-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy in Rats. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Paramesha, B.; Meghwani, H.; Reddy, M.P.K.; Arava, S.K.; Banerjee, S.K. Allyl Methyl Sulfide Preserved Pressure Overload-Induced Heart Failure Via Modulation of Mitochondrial Function. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Wen, S.-Y.; Shibu, M.A.; Yang, Y.-C.; Peng, H.; Wang, B.; Wei, Y.-M.; Chang, H.-Y.; Lee, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; et al. Diallyl trisulfide protects against high glucose-induced cardiac apoptosis by stimulating the production of cystathionine gamma-lyase-derived hydrogen sulfide. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 195, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.-L.; Yan, L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Zeng, G.-H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.-P.; Peng, W.-J.; He, M.; Huang, Q.-R. A role for diallyl trisulfide in mitochondrial antioxidative stress contributes to its protective effects against vascular endothelial impairment. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 725, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lestari, S.R.; Lukiati, B.; Arifah, S.N.; Alimah, A.R.N.; Gofur, A. Medicinal Uses of Single Garlic in Hyperlipidemia by Fatty Acid Synthase Enzyme Inhibitory: Molecular Docking. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 276, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.; Lowe, G.M.; Smith, S. Aged Garlic Extract Inhibits Human Platelet Aggregation by Altering Intracellular Signaling and Platelet Shape Change. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 410S–415S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, K. Effects of garlic on platelet biochemistry and physiology. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Men, W.-X.; Song, Y.-Y.; Xing, Y.-P.; Bian, C.; Xue, H.-F.; Xu, L.; Xie, M.; Kang, T.-G. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Convallaria majalis L. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2022, 7, 692–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.-X.; Chang, X.; Gao, J.; Wu, X.; Wu, J.; Qi, Z.-C.; Wang, R.-H.; Yan, X.-L.; Li, P. Evolutionary Comparison of the Complete Chloroplast Genomes in Convallaria Species and Phylogenetic Study of Asparagaceae. Genes 2022, 13, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, M.; Tatsumi, K.; Yuui, K.; Terazawa, I.; Kudo, R.; Kasuda, S. Convallatoxin, the primary cardiac glycoside in lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis), induces tissue factor expression in endothelial cells. Veter- Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 2440–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, A.; Bourgeois, L. Convallatoxin, the active cardiac glycoside of lily of the valley, minimally affects the ADVIA Centaur digoxin assay. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2018, 32, e22583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prassas, I.; Diamandis, E.P. Novel therapeutic applications of cardiac glycosides. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansbury, J.; Saunders, P.; Winston, D.; Zampieron, E.R. The Use of Convallaria and Crataegus in the Treatment of Cardiac Dysfunction. J. Restor. Med. 2012, 1, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, M.; Tatsumi, K.; Yuui, K.; Terazawa, I.; Kudo, R.; Kasuda, S. Convallatoxin, the primary cardiac glycoside in lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis), induces tissue factor expression in endothelial cells. Veter- Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 2440–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aperia, A.C.; Akkuratov, E.E.; Fontana, J.M.; Brismar, H. Na+-K+-ATPase, a new class of plasma membrane receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2016, 310, C491–C495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aperia, A. New roles for an old enzyme: Na,K-ATPase emerges as an interesting drug target. J. Intern. Med. 2007, 261, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.H.; Kang, D.G.; Cui, X.; Cho, K.W.; Sohn, E.J.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.S. The positive inotropic effect of the aqueous extract of Convallaria keiskei in beating rabbit atria. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartowska, J.; Sommer, E.; Pastewka, K.; Sommer, S.; Skopińska-Rózewska, E. Anti-angiogenic activity of convallamaroside, the steroidal saponin isolated from the rhizomes and roots of Convallaria majalis L. Acta poloniae pharmaceutica 2004, 61, 279–82. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, Y.; Shinoda, D.; Nakamaru, A.; Kamohara, K.; Sakagami, H.; Mimaki, Y. Steroidal Glycosides from Convallaria majalis Whole Plants and Their Cytotoxic Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijatovic, T.; Van Quaquebeke, E.; Delest, B.; Debeir, O.; Darro, F.; Kiss, R. Cardiotonic steroids on the road to anti-cancer therapy. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer 2007, 1776, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogorodnikova, A.V.; Latypova, L.R.; Mukhitova, F.K.; Mukhtarova, L.S.; Grechkin, A.N. Detection of divinyl ether synthase in Lily-of-the-Valley (Convallaria majalis) roots. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 2793–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreea-Miruna, N.; Corneliu-Mircea, C.; Vasile, S.; Raluca, S. Bioactive polyphenolic compounds from Motherwort and Hawthorn hydroethanolic extracts. Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai Chemia 2021, 66, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.L.; Dinu, M.; Toth, O. Contributions to the pharmacognostical and phytobiological study on Leonurus cardiaca L. (Lamiaceae). Farmacia 2009, 57, 424–431. [Google Scholar]

- Romanenko, Y.A.; Koshovyi, O.M.; Komissarenko, A.M.; Golembiovska, O.I.; Gladyish, Y.I. The study of the chemical composition of the components of the motherwort herb. News Pharm. 2018, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermukhamedova, O.V.; Sakipova, Z.B.; I Ternynko, I.; Gemedzhieva, N.G. REPRESENTATIVES OF MOTHERWORT GENUS (LEONURUS SPP.): ASPECTS OF PHARMACOGNOSTIC FEATURES AND RELEVANCE OF NEW SPECIES APPLICATION. Acta poloniae pharmaceutica 2017, 74, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Angeloni, S.; Spinozzi, E.; Maggi, F.; Sagratini, G.; Caprioli, G.; Borsetta, G.; Ak, G.; Sinan, K.I.; Zengin, G.; Arpini, S.; et al. Phytochemical Profile and Biological Activities of Crude and Purified Leonurus cardiaca Extracts. Plants 2021, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierascu, R.C.; Fierascu, I.; Ortan, A.; Fierascu, I.C.; Anuta, V.; Velescu, B.S.; Pituru, S.M.; Dinu-Pirvu, C.E. Leonurus cardiaca L. as a Source of Bioactive Compounds: An Update of the European Medicines Agency Assessment Report (2010). BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Raal, A.; Kireyev, I.; Tryshchuk, N.; Ilina, T.; Romanenko, Y.; Kovalenko, S.M.; Bunyatyan, N. Phytochemical and Psychotropic Research of Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca L.) Modified Dry Extracts. Plants 2021, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierascu, I.C.; Fierascu, I.; Baroi, A.M.; Ungureanu, C.; Spinu, S.; Avramescu, S.M.; Somoghi, R.; Fierascu, R.C.; Dinu-Parvu, C.E. Phytosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Leonurus cardiaca L. Extracts. Materials 2023, 16, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchta, K.; Ortwein, J.; Çaliş, I.; Volk, R.B.; Rauwald, H.W. Identification of Cardioactive Leonurus and Leonotis Drugs by Quantitative HPLC Determination and HPTLC Detection of Phenolic Marker Constituents. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikov, A.N.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Makarov, V.G.; Demchenko, D.V.; Shikh, E.V. Effect of Leonurus cardiaca oil extract in patients with arterial hypertension accompanied by anxiety and sleep disorders. Phytotherapy Res. 2010, 25, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liao, J.; Yao, K.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J. Application of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtyniak, K.; Szymański, M.; Matławska, I. Leonurus cardiaca L. (Motherwort): A Review of its Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Phytotherapy Res. 2012, 27, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Assessment report on Leonurus cardiaca L. herba; Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC): London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Luo, Z.; Lai, B.; Xiao, L.; Wang, N. Stachydrine protects eNOS uncoupling and ameliorates endothelial dysfunction induced by homocysteine. Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, D.; Sang, M.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Q. Stachydrine ameliorates isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by suppressing inflammation and oxidative stress through inhibiting NF-κB and JAK/STAT signaling pathways in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 48, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Jiang, X.; Wei, F.; Zhu, H. Leonurine protects cardiac function following acute myocardial infarction through anti-apoptosis by the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikov, A.N.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Makarov, V.G.; Demchenko, D.V.; Shikh, E.V. Effect of Leonurus cardiaca oil extract in patients with arterial hypertension accompanied by anxiety and sleep disorders. Phytotherapy Res. 2010, 25, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernatoniene, J.; Kopustinskiene, D.M.; Jakstas, V.; Majiene, D.; Baniene, R.; Kuršvietiene, L.; Masteikova, R.; Savickas, A.; Toleikis, A.; Trumbeckaite, S. The Effect of Leonurus cardiaca Herb Extract and Some of its Flavonoids on Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation in the Heart. Planta Medica 2014, 80, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, J.B.; O’Kennon, B.; Lance, R. Hawthorns and Medlars. Royal Horticultural Society. 2003. Available online: https://archive.org/details/hawthornsmedlars00jame (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Furey, A.; Tassell, M.C.; Kingston, R.; Gilroy, D.; Lehane, M. Hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.B.; Petersen, R.K.; Kristiansen, K.; Christensen, L.P. Identification of bioactive compounds from flowers of black elder (Sambucus nigra L.) that activate the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ. Phytotherapy Res. 2010, 24, S129–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dönmez, A.A. Taxonomic notes on the genus Crataegus (Rosaceae) in Turkey. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2007, 155, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, J.B. Biogeographic, Taxonomic, and Cladistic Relationships Between East Asiatic and North American Crataegus. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1983, 70, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.K. Meylers’s Side Effects of Herbal Medicines. Meylers’s Side Effects of Herbal Medicines. Published online 2009, 303.

- Pieroni, A.; Rexhepi, B.; Nedelcheva, A.; Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Kolosova, V.; Cianfaglione, K.; Quave, C.L. One century later: The folk botanical knowledge of the last remaining Albanians of the upper Reka Valley, Mount Korab, Western Macedonia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2013, 9, 22–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Q.; Zuo, Z.; Harrison, F.; Chow, M.S.S. Hawthorn. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 42, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xiong, X.; Feng, B. Effect ofCrataegusUsage in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: An Evidence-Based Approach. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Pittler, M.H.; Ernst, E. Hawthorn extract for treating chronic heart failure. Emergencias 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.F.; Rudolf, F.; Fintelmann, V. Herbal medicine. Published online 2000:438. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/44040405 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Phipps, J.B.; Robertson, K.R.; Smith, P.G.; Rohrer, J.R. A checklist of the subfamily Maloideae (Rosaceae). Can. J. Bot. 1990, 68, 2209–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, C.; Mazzanti, G.; Pittler, M.H.; Ernst, E. Adverse-Event Profile of Crataegus Spp.: A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2006, 29, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazier, M.G.; Bowman, M.A. A Review of the Evidence for the Use of Phytoestrogens as a Replacement for Traditional Estrogen Replacement Therapy. Arch. Intern. Med. 2001, 161, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; El-Mleeh, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Devkota, H.P. Traditional Uses, Bioactive Chemical Constituents, and Pharmacological and Toxicological Activities of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (Fabaceae). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.F.; Marakis, G.; Morris, A.P.; Robinson, P.A. Promising hypotensive effect of hawthorn extract: A randomized double-blind pilot study of mild, essential hypertension. Phytotherapy Res. 2002, 16, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietta, P.-G. Flavonoids as Antioxidants. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chang, Q.; Zhu, M.; Huang, Y.; Ho, W.K.; Chen, Z.-Y. Characterization of antioxidants present in hawthorn fruits. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2001, 12, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthi, S.; Parasakthy, K.; Deepalakshmi, P.D.; Devaraj, S.N. Hypolipidemic activity of tincture of Crataegus in rats. Indian journal of biochemistry & biophysics 1994, 31, 143–6. [Google Scholar]

- Veveris, M.; Koch, E.; Chatterjee, S.S. Crataegus special extract WS® 1442 improves cardiac function and reduces infarct size in a rat model of prolonged coronary ischemia and reperfusion. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 1945–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, G.; Butzer, R.; Gaus, W.; Loew, D. Camphor-Crataegus berry extract combination dose-dependently reduces tilt induced fall in blood pressure in orthostatic hypotension. Phytomedicine international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology 2002, 9, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, D.; Feng, P.-F.; Sun, J.-L.; Guo, F.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, B.-X. The enhancement of cardiac toxicity by concomitant administration of Berberine and macrolides. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. official journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 76, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xu, H.-E.; Ryan, D. A Study of the Comparative Effects of Hawthorn Fruit Compound and Simvastatin on Lowering Blood Lipid Levels. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2009, 37, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, J.A.R.; Leal, A.S.; Alho, D.P.S. Highlights of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in the Cancer Settings. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Elsevier B.V., 2014; Volume 41, pp. 33–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Jain, V.; Verma, D.; Khamesra, R. Crataegus oxycantha - a cardioprotective herb. Journal of Herbal Medicine and Toxicology 2007, 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A.F.; Marakis, G.; Simpson, E.; Hope, J.L.; A Robinson, P.; Hassanein, M.; Simpson, H.C.R. Hypotensive effects of hawthorn for patients with diabetes taking prescription drugs: A randomised controlled trial. The British journal of general practice: The journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 2006, 56, 437–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zick, S.M.; Vautaw, B.M.; Gillespie, B.; Aaronson, K.D. Hawthorn Extract Randomized Blinded Chronic Heart Failure (HERB CHF) Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2009, 11, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanus, M.; Lafon, J.; Mathieu, M. Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a fixed combination containing two plant extracts (Crataegus oxyacantha and Eschscholtzia californica) and magnesium in mild-to-moderate anxiety disorders. Curr. Med Res. Opin. 2003, 20, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chai, X.; Zhao, F.; Hou, G.; Meng, Q. Food Applications and Potential Health Benefits of Hawthorn. Foods 2022, 11, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mobideen, O.K.; Alqudah, A.A.; Al Mustafa, A.; Alhawarat, F.; Mizher, H. Effect of Crataegus aronia on the Biochemical Parameters in Induced Diabetic Rats. Pharmacogn. J. 2022, 14, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, F.; Perrone, A.; Yousefi, S.; Papini, A.; Castiglione, S.; Guarino, F.; Cicatelli, A.; Aelaei, M.; Arad, N.; Gholami, M.; et al. Botanical, Phytochemical, Anti-Microbial and Pharmaceutical Characteristics of Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna Jacq.), Rosaceae. Molecules 2021, 26, 7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rababa'H, A.M.; Al Yacoub, O.N.; El-Elimat, T.; Rabab'Ah, M.; Altarabsheh, S.; Deo, S.; Al-Azayzih, A.; Zayed, A.; Alazzam, S.; Alzoubi, K.H. The effect of hawthorn flower and leaf extract (Crataegus Spp.) on cardiac hemostasis and oxidative parameters in Sprague Dawley rats. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Lin, H.-R.; Yang, C.-S.; Liaw, C.-C.; Sung, P.-J.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Cheng, M.-J.; Chen, J.-J. Antioxidant and Anti-α-Glucosidase Activities of Various Solvent Extracts and Major Bioactive Components from the Fruits of Crataegus pinnatifida. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chi, B.; Xia, M.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, F.; Tian, Z. LC–MS-based lipidomic analysis of liver tissue sample from spontaneously hypertensive rats treated with extract hawthorn fruits. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 963280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, B.Z.; Dizaye, K.F. The impact of Procyanidin extracted from Crataegus azarolus on rats with induced heart failure. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2022, 68, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Herbal Raw Material |

Active Compounds | Functions | Mechanism of Action | Model | Dose | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Phenolic groups, naringenin and quercetin | Cardioprotective Antioxidant |

↑ scavenging of the free radicals (OH) ↓ peroxidation of lipids ↓ GSH, Gpx, SOD, CAT, TBARS |

male albino Wistar rats | 500 mg/kg b.w. for 15 days p.o. | [9] |

| Flavonoids (isoflavones, flavanone, flavonols, morusin, cyclomorusin, and neocyclomorusin) novel prenylated flavonoids (isoquercetin, quercetin, astragalin, and scopoline) glycosides (namelyroseoside III and benzyl D–glucopyranoside) |

Anti–hypertensive Antioxidant Cardioprotective |

↑ cellular antioxidants (↑ GSH, SOD, and CAT, ↓ LPO) ↓ heart rate, ↓ heart weight ↓ pressure–rate index ↓ levels of cardiac damage marker enzymes |

male Wistar rats | 25, 50, 100 mg/kg b.w. for three weeks p.o. | [10] | |

| Anti–hypertensive Hypolipidemic Vascular improvement Lipid regulation agent |

↓ of cell adhesion molecules (E–selectin, VCAM–1, ICAM–1) expression in the aorta |

male rats | 100, 200 mg/kg b.w. for 14 weeks | [13] | ||

| Rutin, chlorogenic acid, astragalin | Vascular effect | ↑ NO, eNOS ↑ phosphorylation of PERK and HSP90 at threonine |

Mice | 100, 200, or 400 mg/kg b.w. | [11] | |

| Rutin and isoquercetin | Antiplatelet Antithrombotic Prevention or treatment of myocardial infarction |

↓MAPK–integrin α IIb β 3 ↓ PLA2/TXA2 routes ↓TXB2 formation ↓ serotonin secretion ↓ aggregation ↓ thrombus formation |

male Sprague Dawley rats | 100, 200, 400 mg/kg b.w. for 3 days | [12] | |

| Mulberroside A, chlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, astragaloside, resveratrol, scopoletin, 1–deoxynojirimycin | Glucose improvement Lipid metabolism improvement |

↓TGF–β–Smad2/3 | male C57BL/6 mice | 1,000 mg/kg b.w. for 12 weeks p.o. | [14] | |

| Neochlorogenic acid | Anti–atherosclerotic | ↓ FAK/small GTPase proteins ↓ PI3K/Akt ↓ Ras–related signaling ↓ vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) migration and proliferation |

Ex vivo A7r5 cells (VSMCs) |

3.0 mg/mL for 24 h | [15] |

| Herbal raw material |

Active compounds | Functions | Mechanism of action | Model | Dose | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | polyphenols (proanthocyanidins) flavonoids (flavonol glycosides isorhamnetin 3–O–hexoside–deoxyhexoside and isorhamnetin 3–O–hexoside) phenolic acids vitamins (vitamin C) fatty acids and phytosterols triterpenes and triterpene derivates (derived from isorhamnetin) compounds derived from quercetin, and kaempferol |

Anti–platelet Anticoagulant |

↓ surface exposition GPIIb/IIIa and P–selectin | In vitro | 50 μg/mL; 10 min |

[16] [18] |

| Leaves | ellagitannins (casuarinin, hippophaenin B, casuarictin, stachyurin, strictinin or their isomers), ellagic acid and its glycosides flavonoids (glycosides of isorhamnetin, kaempferol and quercetin) |

Anti–platelet | ↓ surface exposition of P–selectin ↓ surface exposition of GPIIb/IIIa active complex |

In vitro | 5 and 50 μg/mL; 30 min |

[17] |

| Twigs | Proanthocyanidins Catechin |

Anticoagulant Anti–platelet |

↓ surface exposition of P–selectin ↓ surface exposition of GPIIb/IIIa active complex |

In vitro | 5 and 50 μg/mL; 30 min |

[17] |

| Seeds | Flavonoids (glycosides of isorhamnetin, kaempferol, and quercetin), proanthocyanidins and catechin, triterpenoid saponins, and several unidentified polar and hydrophobic compounds |

Antioxidant Anticoagulant |

↓ lipid peroxidation and protein carbonylation ↓ oxidation of thiol groups |

In vitro | 0.5, 5.0, 50 µg/mL | [19] |

| Herbal raw material |

Active compounds | Functions | Mechanism of action | Model | Dose | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulb | Organosulfur compounds: alliin, allicin, E–ajoene, Z–ajoene, 2–vinyl–4H–1,3–dithiin, diallyl sulfide (DAS), diallyl disulfide (DADS), diallyl trisulfide (DATS) and allyl methyl sulfide (AMS) |

Hypoglycemic Hypolipidemic |

↓ total triglycerides and free fatty acids ↑ HDL–cholesterol |

In vivo mice |

0.1 mg/mL for 8 weeks Alliin (S–allyl cysteine sulfoxide) p.o. |

[34] |

| Antioxidant | ↓lipid peroxidation ↓ free radicals |

In vivo male albino Wistar rats |

2 mL S–allyl cysteine sulfoxide (SACS) p.o. |

[30] [31] [36] |

||

| Antioxidant Vascular |

↑ NO and eNOS | In vitro endothelial progenitor cells |

100 µg/mL 200 µg/mL 400 µg/mL allicin |

[39] | ||

| Antioxidant | ↑ glutathione levels in vascular endothelial cells ↓triglycerides |

In vivo male SHR |

80 mg/kg/day allicin p.o. |

[40] | ||

| Antioxidant | ↓ ROS ↓ cell growth and migration |

In vitro vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) |

10 and 100 μg/L 2–vinyl–4H–1,3–Dithiin |

[41] | ||

| Antioxidant | ↓ cardiac hypertrophy markers | In vivo male Sprague Dawley |

250 mg/kg garlic | [42] | ||

| 25, 50, 100, 200 mg/kg/day Allylmethylsulfide (AMS) p.o. | [43] | |||||

| Cardioprotective Anti–apoptotic |

↑ IGF1R survival signaling pathway protein expression ↑ PI3K/Akt pathway ↓ ROS |

In vitro and in vivo cardiomyocyte cell line H9c2 and hearts from rats with streptozotocin–induced diabetes mellitus |

10 μM diallyl trisulfide (DAT) |

[44] | ||

| Antioxidant Vascular |

ND1 | In vivo obese diabetic rats |

5 mg/kg/day diallyl trisulfide (DAT) |

[45] | ||

| Anti–aggregation | ↓platelet aggregation ↓ cAMP and cGMP stimulation ↓fibrinogen binding to the GPIIb/IIIa receptor |

In vitro human platelet aggregation |

6.25% aged garlic extract |

[47] | ||

| Lipid regulation | ↓ lipogenesis and cholesterogenesis | In vivo male albino diabetic rats |

1 mL garlic aqueous leaf extract |

[35] |

| Herbal raw material |

Active compounds | Functions | Mechanism of action | Model | Dose | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herb | cardiac glycosides: convallotoxin, convallarin, convalloside, convallasaponin, cholestane glycoside, strophanthidin, cannogenol, sarmentogenin, dipindogenin, hydroxysarmentogenin saponins |

Heart failure | ↓ Na+/K+–ATPase inhibition ↑ Na+ ions ↑ Ca2+ ions positive inotropic effect ↓ viability of HUVECs ↑ TF mRNA and protein expression |

In vitro Serum Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) |

50 and 100 nM for 4 h |

[52] [55] [56] |

| Anti–inflammatory | ↓ lipoxygenase inhibition | In vitro linoleic acid |

5 g of the roots | [62] | ||

| Convallatoxin/Convallaria keiskei | Cardiovascular effect | ↑ atrial stroke volume and pulse pressure, positive inotropic effect vasoconstrictor, and vasodilator effects ↑ cAMP efflux ↑ K+ concentration |

Ex vivo beating rabbit atria, male New Zealand white rabbits weighing about 2 kg |

1 x 10–5 M Convallatoxin 3 × 10−6 g/mL Convallaria keiskei |

[54] [57] [58] |

|

| convallamaroside | Anticancer | ↓ angiogenesis | Ex vivo mice on tumor angiogenesis reaction induced by tumor cells |

10,20,50,100 µg/day 1.5 h incubation |

[59] [60] [61] |

| Herbal raw material |

Active compounds | Functions | Mechanism of action | Model | Dose | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | Stachydrine | Vaso–protective | ↑ expression of PTCH1 and DHFR | In vivo and ex vivo isolated rat thoracic aortas, mesenteric arteries, and renal arteries from male Sprague–Dawley rats. Bovine aorta endothelial cells (BAECs) |

10 μM for 12 hours; 0–10 μM for 24 hours |

[76] |

| ND1 | Stachydrine | Cardioprotective Antioxidant Anti–inflammatory |

↓NF–κB and JAK/STAT | In vivo male Sprague–Dawley rats |

10, 40 mg/kg b.w. for 21 days p.o. | [77] |

| Herb | Leonurine | Antiapoptotic Cardioprotective |

↑ PI3K/AKT/GSK3β | In vivo male Sprague–Dawley rats |

15 mg/ kg b.w. for 28 days p.o. |

[78] |

| labdane diterpenes: leosibirin, leosibiricin, 19–acetoxypregaleopsin flavonoid glycosides based on querectin and apigenin, phenylpropanoids: eugenol, lavandulifolioside, alkaloids: stachydrine, betonicine, leonurine, iridoids: ajugol, ajugoside, harpagide |

Antihypertensive Psycho–neurological |

ND1 | In vivo male and female patients |

1200 mg per day for 28 days |

[79] | |

| Chlorogenic acid, orientin, quercetin, hyperoside, and rutin | Cardioprotective | ↓ mitochondrial ROS generation | Ex vivo rat heart mitochondria |

6.8 μg/mL 18.2 μg/mL |

[80] |

| Herbal raw material |

Active compounds | Functions | Mechanism of action | Model | Dose | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Flavonoids (quercetin, vitexin–2″–O–α–L–rhamnoside, hispertin, pinnatifinosides I, cratenacin), oligomeric proanthocyanidins (proanthocyanidin A2) |

Antioxidant Cardioprotective Antihypertensive Vasodilator |

↑myocardial perfusion ↓ of phosphodiesterase, ↑ in cGMP in smooth muscle cells |

In vivo diabetic and non–diabetic rats |

5 or 10 mg/kg | [109] [110] |

| Flowers | Flavonoids (rutin, hyperoside, vitexin–2″–O–rhamnoside), phenols (chlorogenic acid) oligomeric proanthocyanidins (proanthocyanidin A2) |

Antioxidant Cardioprotective Anti–inflammatory Anti–atherosclerotic Anticoagulant |

↑ improving the blood flow in blood vessels | Sprague Dawley rats | 100, 200, and 500 mg/kg for 3 weeks p.o. | [109] [111] [112] |

| Fruits | Polyphenols, flavonoids (hyperoside, hesperidin, rutoside, crataequinone A–B), vitamin C proanthocyanidins (procyanidin B2), phenols (chlorogenic acid) |

Antioxidant Cardioprotective Hypolipidemic Anti–aggregation |

ND1 | In vivo 12–week–old rats 8–week–old SHR |

1.08 g/kg body weight per day intragastrically 30 mg/kg Procyanidin |

[109] [111] [113] [114] [115] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).