Submitted:

14 March 2024

Posted:

15 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Eukaryotic Cell Culture and Maintenance Conditions

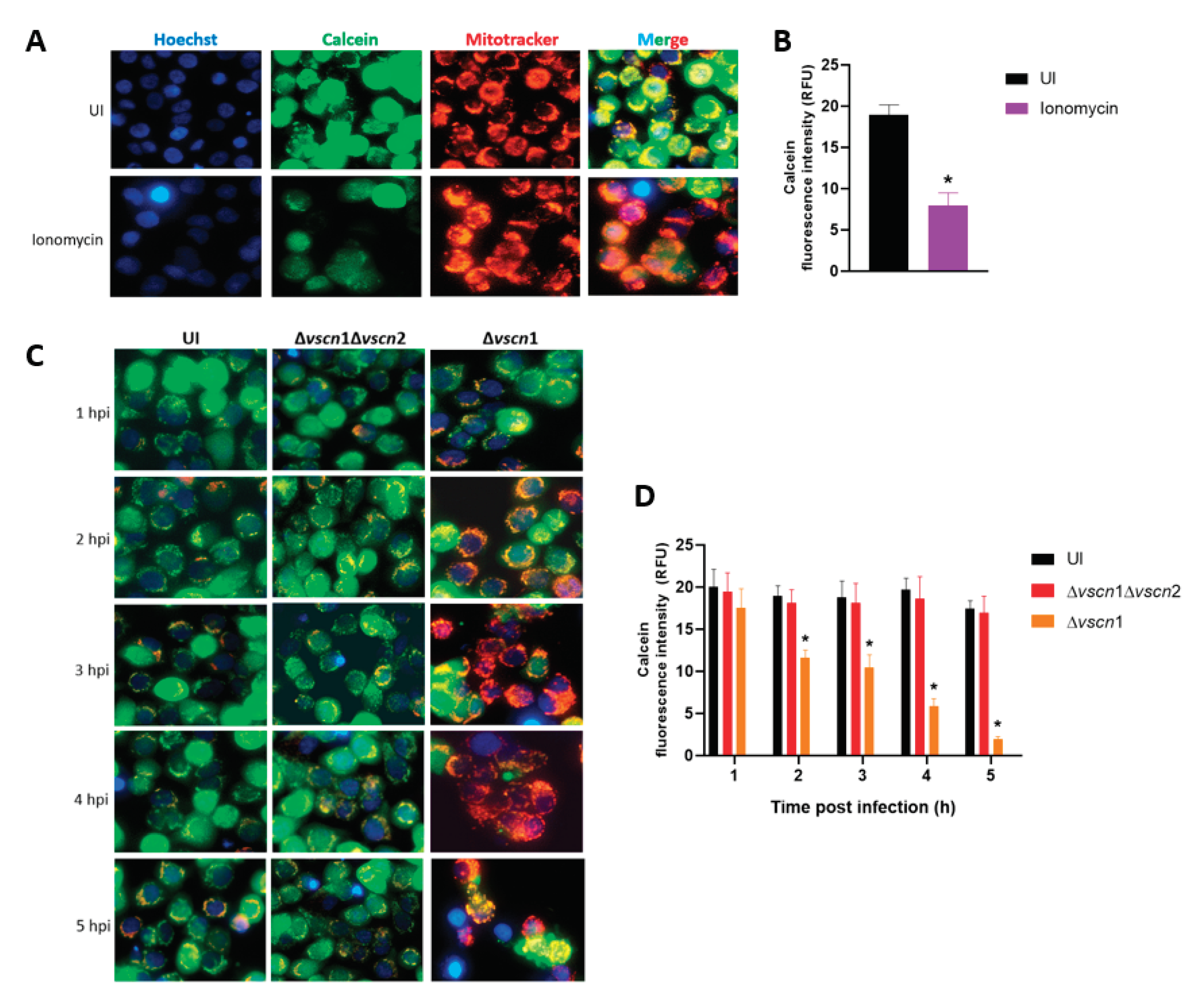

2.3. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (mPTP) Assay

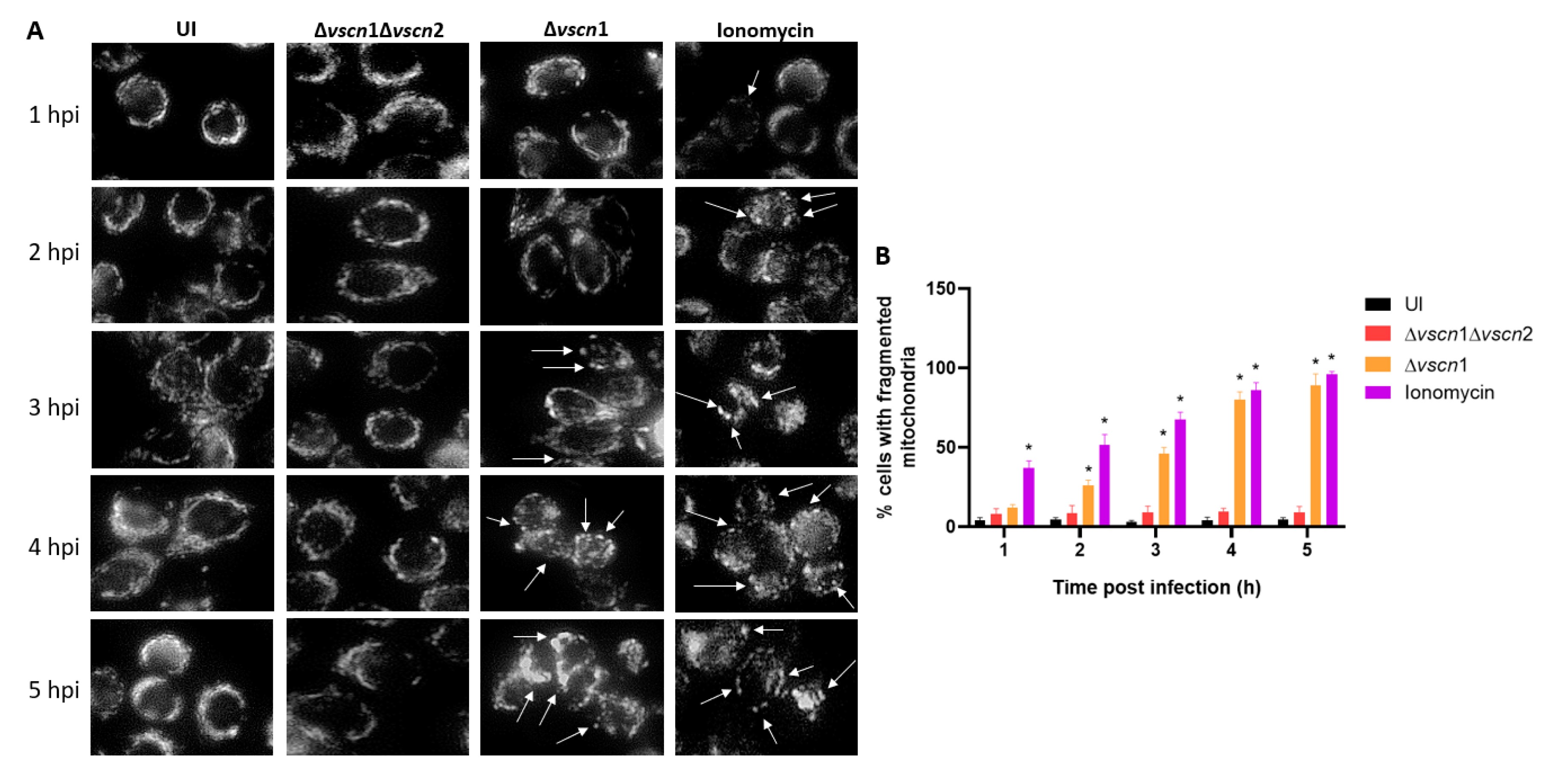

2.4. Mitochondrial Fragmentation

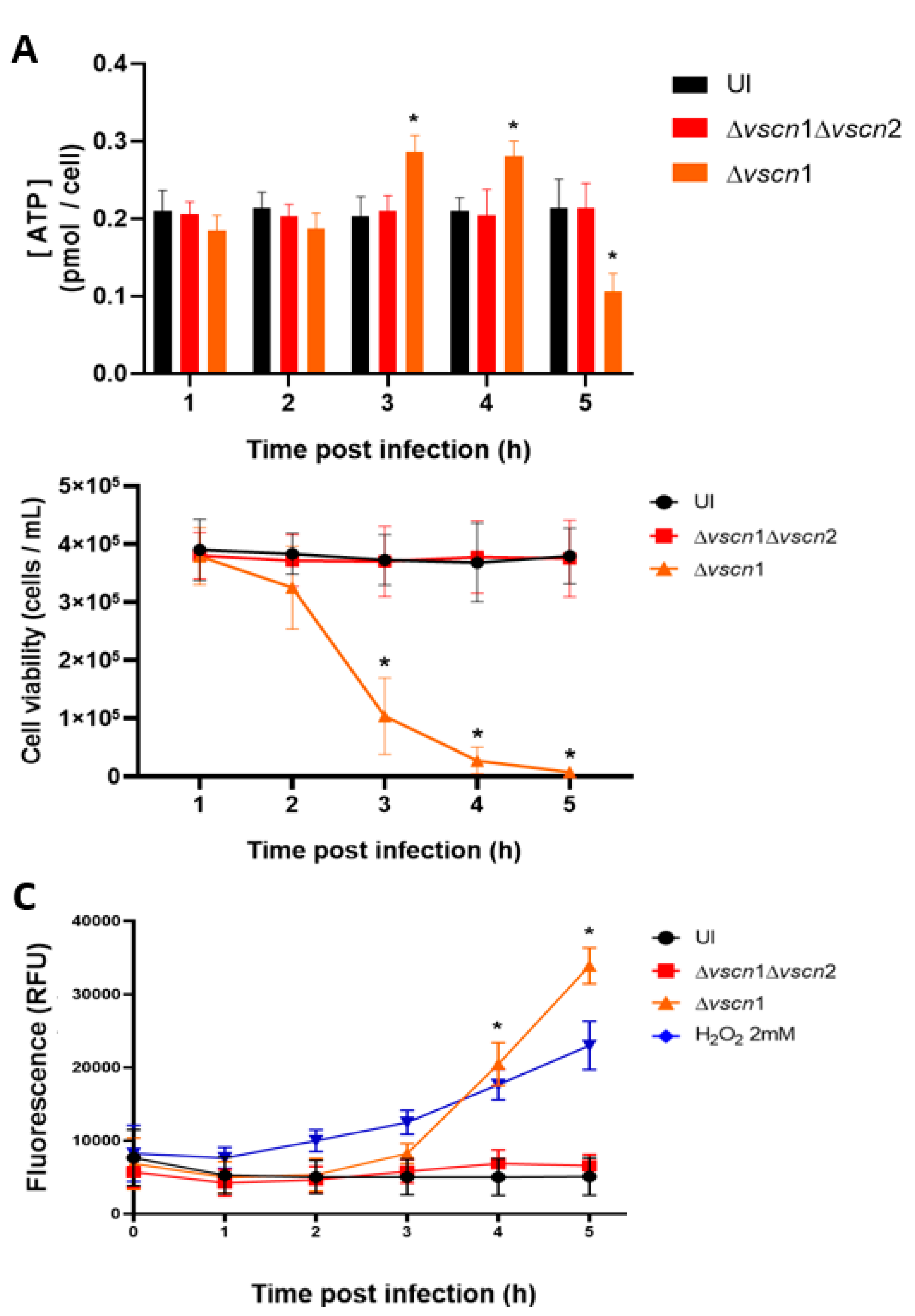

2.5. ATP Determination Assay

2.6. Infection with V. parahaemolyticus and T3SS2-Dependent Cell Death Assay

3. Results

3.1. V. parahaemolyticus Induces mPTP opening T3SS2-Dependent Manner in Intestinal Cells

3.2. V. parahaemolyticus Has the Ability to Induce Mitochondrial Fragmentation, Disrupt ATP Production, and Trigger T3SS2-Dependent Cell Death during Infection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Letchumanan, V.; Chan, K.-G.; Lee, L.-H. Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a review on the pathogenesis, prevalence, and advance molecular identification techniques. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Roman, J.; León-Sicairos, N.; Hernández-Díaz, L.d.J.; Canizalez-Roman, A. Pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 on the American continent. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 3, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, K.; Oshima, K.; Kurokawa, K.; Yokoyama, K.; Uda, T.; Tagomori, K.; Iijima, Y.; Najima, M.; Nakano, M.; Yamashita, A.; et al. Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V cholerae. Lancet 2003, 361, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abby, S.S.; Rocha, E.P.C. The Non-Flagellar Type III Secretion System Evolved from the Bacterial Flagellum and Diversified into Host-Cell Adapted Systems. PLOS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Drees, K.P.; Sebra, R.P.; Cooper, V.S.; Jones, S.H.; Whistler, C.A. Parallel Evolution of Two Clades of an Atlantic-Endemic Pathogenic Lineage of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by Independent Acquisition of Related Pathogenicity Islands. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Tejero, M.; Galán, J.E. The Injectisome, a Complex Nanomachine for Protein Injection into Mammalian Cells. EcoSal Plus 2019, 8, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portaliou, A.G.; Tsolis, K.C.; Loos, M.S.; Zorzini, V.; Economou, A. Type III Secretion: Building and Operating a Remarkable Nanomachine. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 41, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Danilchanka, O.; Mekalanos, J.J. Vibrio cholerae T3SS Effector VopE Modulates Mitochondrial Dynamics and Innate Immune Signaling by Targeting Miro GTPases. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, I.; Aroeti, L.; Ramachandran, R.P.; Kassa, E.G.; Zlotkin-Rivkin, E.; Aroeti, B. Type III secreted effectors that target mitochondria. Cell. Microbiol. 2021, 23, e13352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, D.C. H. Chen, D.C. Chan, Mitochondrial dynamics in mammals, Curr Top Dev Biol 59 (2004) 119-44.

- Ramaccini, D.; Montoya-Uribe, V.; Aan, F.J.; Modesti, L.; Potes, Y.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Krga, I.; Glibetić, M.; Pinton, P.; Giorgi, C.; et al. Mitochondrial Function and Dysfunction in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Dean, M. P. Dean, M. Maresca, S. Schuller, A.D. Phillips, B. Kenny, Potent diarrheagenic mechanism mediated by the cooperative action of three enteropathogenic Escherichia coli-injected effector proteins, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(6) (2006) 1876-81.

- Dean, P.; Kenny, B. The effector repertoire of enteropathogenic E. coli: ganging up on the host cell. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, S.; Rhamouni, S.; Tautz, L.; Denault, J.-B.; Alonso, A.; Becattini, B.; Salvesen, G.S.; Mustelin, T. Yersinia Phosphatase Induces Mitochondrially Dependent Apoptosis of T Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 10388–10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Jesenberger, K.J. V. Jesenberger, K.J. Procyk, J. Yuan, S. Reipert, M. Baccarini, Salmonella-induced caspase-2 activation in macrophages: a novel mechanism in pathogen-mediated apoptosis, J Exp Med 192(7) (2000) 1035-46.

- Hubbard, T.P.; Chao, M.C.; Abel, S.; Blondel, C.J.; Wiesch, P.A.Z.; Zhou, X.; Davis, B.M.; Waldor, M.K. Genetic analysis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus intestinal colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 6283–6288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeyro, P.; Zhou, X.; Orfe, L.H.; Friel, P.J.; Lahmers, K.; Call, D.R. Development of Two Animal Models To Study the Function of Vibrio parahaemolyticus Type III Secretion Systems. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 4551–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.M.; Rui, H.; Zhou, X.; Iida, T.; Kodoma, T.; Ito, S.; Davis, B.M.; Bronson, R.T.; Waldor, M.K. Inflammation and Disintegration of Intestinal Villi in an Experimental Model for Vibrio parahaemolyticus-Induced Diarrhea. PLOS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondel, C.J.; Park, J.S.; Hubbard, T.P.; Pacheco, A.R.; Kuehl, C.J.; Walsh, M.J.; Davis, B.M.; Gewurz, B.E.; Doench, J.G.; Waldor, M.K. CRISPR/Cas9 Screens Reveal Requirements for Host Cell Sulfation and Fucosylation in Bacterial Type III Secretion System-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Gewurz, B.E.; Ritchie, J.M.; Takasaki, K.; Greenfeld, H.; Kieff, E.; Davis, B.M.; Waldor, M.K. A Vibrio parahaemolyticus T3SS Effector Mediates Pathogenesis by Independently Enabling Intestinal Colonization and Inhibiting TAK1 Activation. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1690–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, K.; Kodama, T.; Hiyoshi, H.; Izutsu, K.; Park, K.-S.; Dryselius, R.; Akeda, Y.; Honda, T.; Iida, T. Bile Acid-Induced Virulence Gene Expression of Vibrio parahaemolyticus Reveals a Novel Therapeutic Potential for Bile Acid Sequestrants. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e13365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petronilli, V.; Miotto, G.; Canton, M.; Colonna, R.; Bernardi, P.; Di Lisa, F. Imaging the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in intact cells. BioFactors 1998, 8, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenger, H.-G.; Langer, T. The Good and the Bad of Mitochondrial Breakups. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamaraeva, M.V.; Sabirov, R.Z.; Maeno, E.; Ando-Akatsuka, Y.; Bessonova, S.V.; Okada, Y. Cells die with increased cytosolic ATP during apoptosis: a bioluminescence study with intracellular luciferase. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlawska-Wasowska, K.; Finn, R.; Mustel, A.; O'Byrne, C.P.; Baird, A.W.; Coffey, E.T.; Boyd, A. The Vibrio parahaemolyticus Type III Secretion Systems manipulate host cell MAPK for critical steps in pathogenesis. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 329–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, N.; Urrutia, I.M.; Garcia, K.; Waldor, M.K.; Blondel, C.J. Identification of a Family of Vibrio Type III Secretion System Effectors That Contain a Conserved Serine/Threonine Kinase Domain. mSphere 2021, 6, e0059921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, S.; Morroni, G.; Pinton, P.; Galluzzi, L. Control of host mitochondria by bacterial pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 30, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Gan, H.; Remold, H.G. A Mechanism of Virulence: Virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis Strain H37Rv, but Not Attenuated H37Ra, Causes Significant Mitochondrial Inner Membrane Disruption in Macrophages Leading to Necrosis. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 3707–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavru, F.; Palmer, A.E.; Wang, C.; Youle, R.J.; Cossart, P. Atypical mitochondrial fission upon bacterial infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16003–16008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vringer, E.; Tait, S.W.G. Mitochondria and cell death-associated inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 30, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Spier, A.; Chaze, T.; Matondo, M.; Cossart, P.; Stavru, F. Listeria monocytogenes Exploits Mitochondrial Contact Site and Cristae Organizing System Complex Subunit Mic10 To Promote Mitochondrial Fragmentation and Cellular Infection. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavru, F.; Cossart, P. Listeria infection modulates mitochondrial dynamics. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2011, 4, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escoll, P.; Song, O.-R.; Viana, F.; Steiner, B.; Lagache, T.; Olivo-Marin, J.-C.; Impens, F.; Brodin, P.; Hilbi, H.; Buchrieser, C. Legionella pneumophila Modulates Mitochondrial Dynamics to Trigger Metabolic Repurposing of Infected Macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Chatterjee, N.S. Vibrio cholerae GbpA elicits necrotic cell death in intestinal cells. J. Med Microbiol. 2016, 65, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, K.; Terasaki, Y.; Miyoshi-Akiyama, T.; Terasaki, M.; Moss, J.; Noda, M.; Yahiro, K. Vibrio cholerae Cholix toxin-induced HepG2 cell death is enhanced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha through ROS and intracellular signal-regulated kinases. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 156, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, R.P.; Spiegel, C.; Keren, Y.; Danieli, T.; Melamed-Book, N.; Pal, R.R.; Zlotkin-Rivkin, E.; Rosenshine, I.; Aroeti, B. Mitochondrial Targeting of the Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Map Triggers Calcium Mobilization, ADAM10-MAP Kinase Signaling, and Host Cell Apoptosis. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbowski, M.; Youle, R.J. Dynamics of mitochondrial morphology in healthy cells and during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2003, 10, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K.W. Kinnally, P.M. K.W. Kinnally, P.M. Peixoto, S.Y. Ryu, L.M. Dejean, Is mPTP the gatekeeper for necrosis, apoptosis, or both?, Biochim Biophys Acta 1813(4) (2011) 616-22.

- Leist, M.; Single, B.; Castoldi, A.F.; Kühnle, S.; Nicotera, P. Intracellular Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Concentration: A Switch in the Decision Between Apoptosis and Necrosis. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L. Necroptosis: an alternative cell death program defending against cancer. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer 2016, 1865, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).