Submitted:

13 March 2024

Posted:

14 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Driesen, E.; Van den Ende, W.; De Proft, M.; Saeys, W. Influence of Environmental Factors Light, CO2, Temperature, and Relative Humidity on Stomatal Opening and Development: A Review. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; An, S.; Pham, M.D.; Cui, M.; Chun, C. The Combined Conditions of Photoperiod, Light Intensity, and Air Temperature Control the Growth and Development of Tomato and Red Pepper Seedlings in a Closed Transplant Production System. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Kumar, N.; Verma, A.; Singh, H.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Singh, N.P. Novel Approaches to Mitigate Heat Stress Impacts on Crop Growth and Development. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2020, 25, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Prueger, J.H. Temperature Extremes: Effect on Plant Growth and Development. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2015, 10, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.; Rasmussen, A.; Porter, J.R. Temperatures and the Growth and Development of Maize and Rice: A Review. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägermeyr, J.; Müller, C.; Ruane, A.C.; Elliott, J.; Balkovic, J.; Castillo, O.; Faye, B.; Foster, I.; Folberth, C.; Franke, J.A.; et al. Climate Impacts on Global Agriculture Emerge Earlier in New Generation of Climate and Crop Models. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghil, M.; Lucarini, V. The Physics of Climate Variability and Climate Change. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2020, 92, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongoma, V.; Chen, H. Temporal and Spatial Variability of Temperature and Precipitation over East Africa from 1951 to 2010. Meteorol. Atmospheric Phys. 2017, 129, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, M.; Fibbi, L.; Gozzini, B.; Orlandini, S.; Miglietta, F. Modelling the Impact of Future Climate Scenarios on Yield and Yield Variability of Grapevine. Clim Res 1996, 7, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droulia, F.; Charalampopoulos, I. A Review on the Observed Climate Change in Europe and Its Impacts on Viticulture. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, S.; Álvarez-Esteban, R.; Alonso-Redondo, R.; Hidalgo, C.; Penas, Á. A New Integrated Methodology for Characterizing and Assessing Suitable Areas for Viticulture: A Case Study in Northwest Spain. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 131, 126391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Yang, Z.Q.; Lee, K.W. Photosynthetic and Physiological Responses to High Temperature in Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Leaves during the Seedling Stage. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 92, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagay, V.; Collins, C. Effects of Timing and Intensity of Elevated Temperatures on Reproductive Development of Field-Grown Shiraz Grapevines. OENO One 2017, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, W.; Petrie, P.R.; Barlow, E.W.R. The Effect of Temperature on Grapevine Phenological Intervals: Sensitivity of Budburst to Flowering. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 315, 108841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rességuier, L.; Mary, S.; Le Roux, R.; Petitjean, T.; Quénol, H.; van Leeuwen, C. Temperature Variability at Local Scale in the Bordeaux Area. Relations With Environmental Factors and Impact on Vine Phenology. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.V.; Davis, R.E. Climate Influences on Grapevine Phenology, Grape Composition, and Wine Production and Quality for Bordeaux, France. Am J Enol Vitic 2000, 51, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Palliotti, A.; Dai, Z.; Duchêne, E.; Truong, T.-T.; Ferrara, G.; Matarrese, A.M.S.; Gallotta, A.; Bellincontro, A.; et al. Grapevine Quality: A Multiple Choice Issue. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droulia, F.; Charalampopoulos, I. Future Climate Change Impacts on European Viticulture: A Review on Recent Scientific Advances. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Jones, G.V.; Alves, F.; Pinto, J.G.; Santos, J.A. Very High Resolution Bioclimatic Zoning of Portuguese Wine Regions: Present and Future Scenarios. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Cardoso, R.M.; Soares, P.M.M.; Cancela, J.J.; Santos, J.A. Integrated Analysis of Climate, Soil, Topography and Vegetative Growth in Iberian Viticultural Regions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venios, X.; Korkas, E.; Nisiotou, A.; Banilas, G. Grapevine Responses to Heat Stress and Global Warming. Plants 2020, 9, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, I.; Droulia, F.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Dimopoulos, P. Future Bioclimatic Change of Agricultural and Natural Areas in Central Europe: An Ultra-High Resolution Analysis of the De Martonne Index. Water 2023, 15, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, I.; Droulia, F.; Evans, J. The Bioclimatic Change of the Agricultural and Natural Areas of the Adriatic Coastal Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, I.; Droulia, F. Frost Conditions Due to Climate Change in South-Eastern Europe via a High-Spatiotemporal-Resolution Dataset. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, I.; Droulia, F. The Agro-Meteorological Caused Famines as an Evolutionary Factor in the Formation of Civilisation and History: Representative Cases in Europe. Climate 2021, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Santos, J.A. An Overview of Climate Change Impacts on European Viticulture. Food Energy Secur. 2012, 1, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.V.; White, M.A.; Cooper, O.R.; Storchmann, K. Climate Change and Global Wine Quality. Clim Change 2005, 73, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgubin, G.; Swingedouw, D.; Mignot, J.; Gambetta, G.A.; Bois, B.; Loukos, H.; Noël, T.; Pieri, P.; García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Ollat, N.; et al. Non-Linear Loss of Suitable Wine Regions over Europe in Response to Increasing Global Warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 808–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittis, G.; Almazroui, M.; Alpert, P.; Ciais, P.; Cramer, W.; Dahdal, Y.; Fnais, M.; Francis, D.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Howari, F.; et al. Climate Change and Weather Extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Molitor, D.; Leolini, L.; Santos, J.A. What Is the Impact of Heatwaves on European Viticulture? A Modelling Assessment. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vautard, R.; van Oldenborgh, G.J.; Bonnet, R.; Li, S.; Robin, Y.; Kew, S.; Philip, S.; Soubeyroux, J.-M.; Dubuisson, B.; Viovy, N.; et al. Human Influence on Growing-Period Frosts like in Early April 2021 in Central France. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Fraga, H.; Santos, J.A. Exposure of Portuguese Viticulture to Weather Extremes under Climate Change. Clim. Serv. 2023, 30, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandhauer, M.; Isotta, F.; Lakatos, M.; Lussana, C.; Båserud, L.; Izsák, B.; Szentes, O.; Tveito, O.E.; Frei, C. Evaluation of Daily Precipitation Analyses in E-OBS (V19.0e) and ERA5 by Comparison to Regional High-Resolution Datasets in European Regions. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

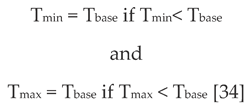

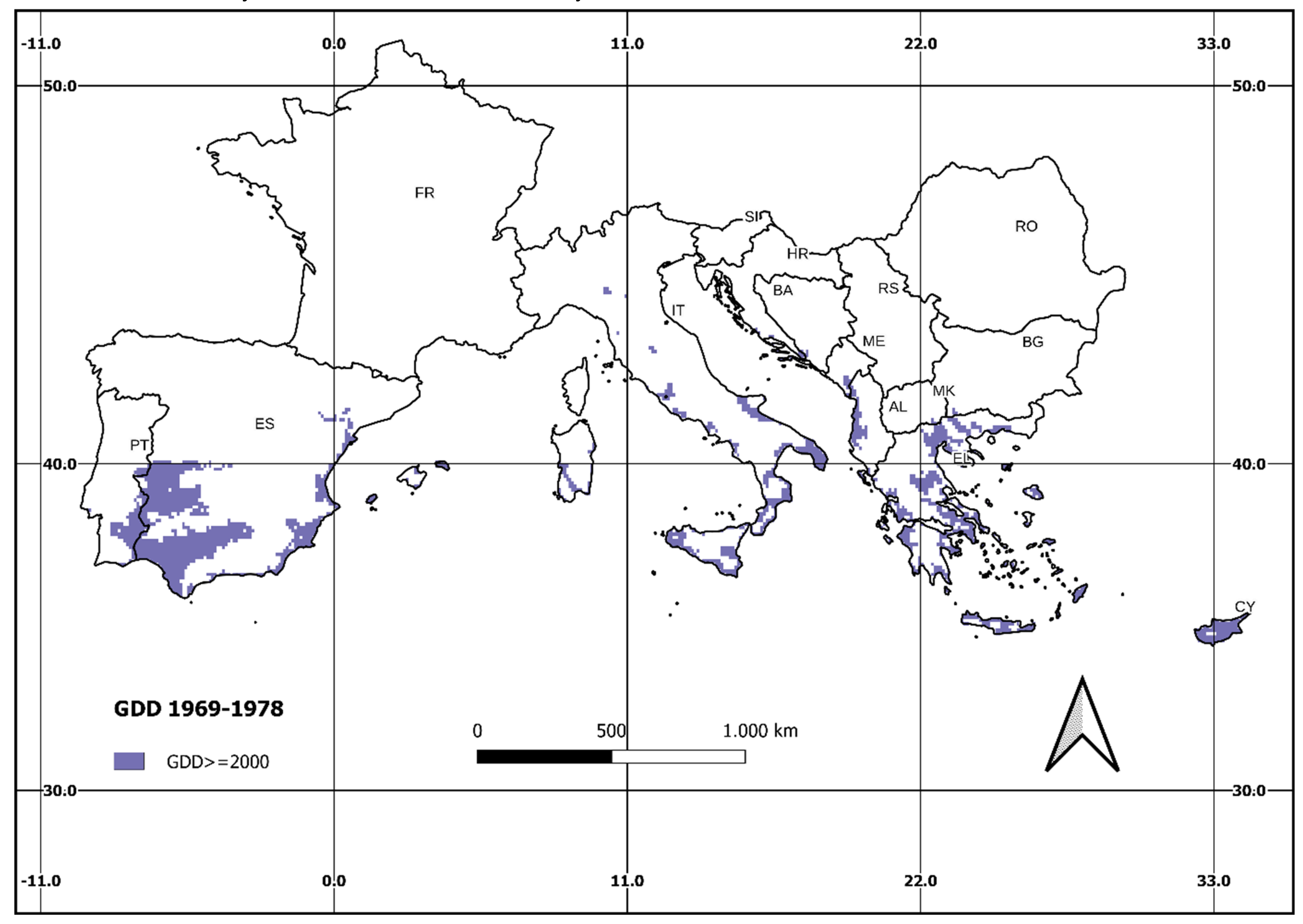

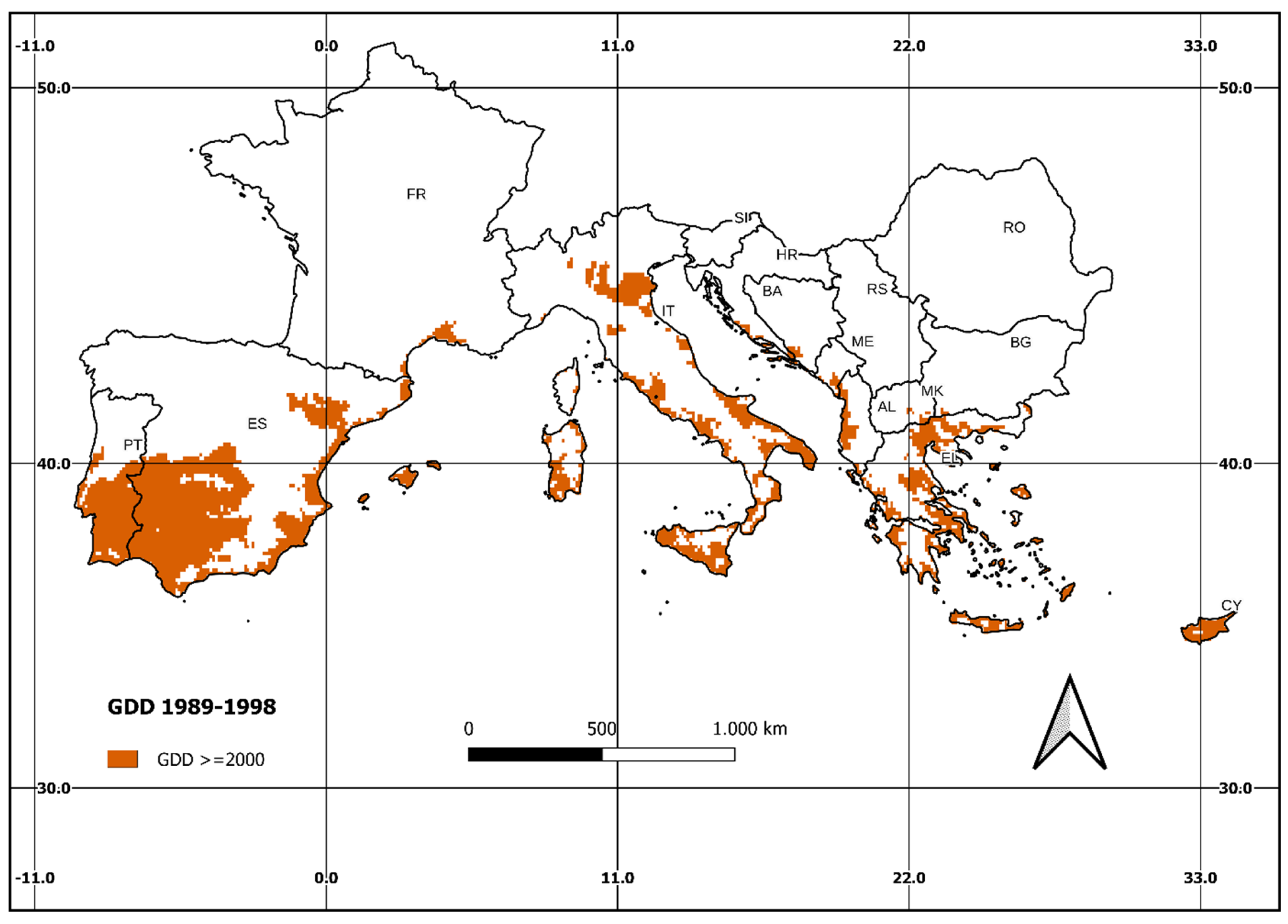

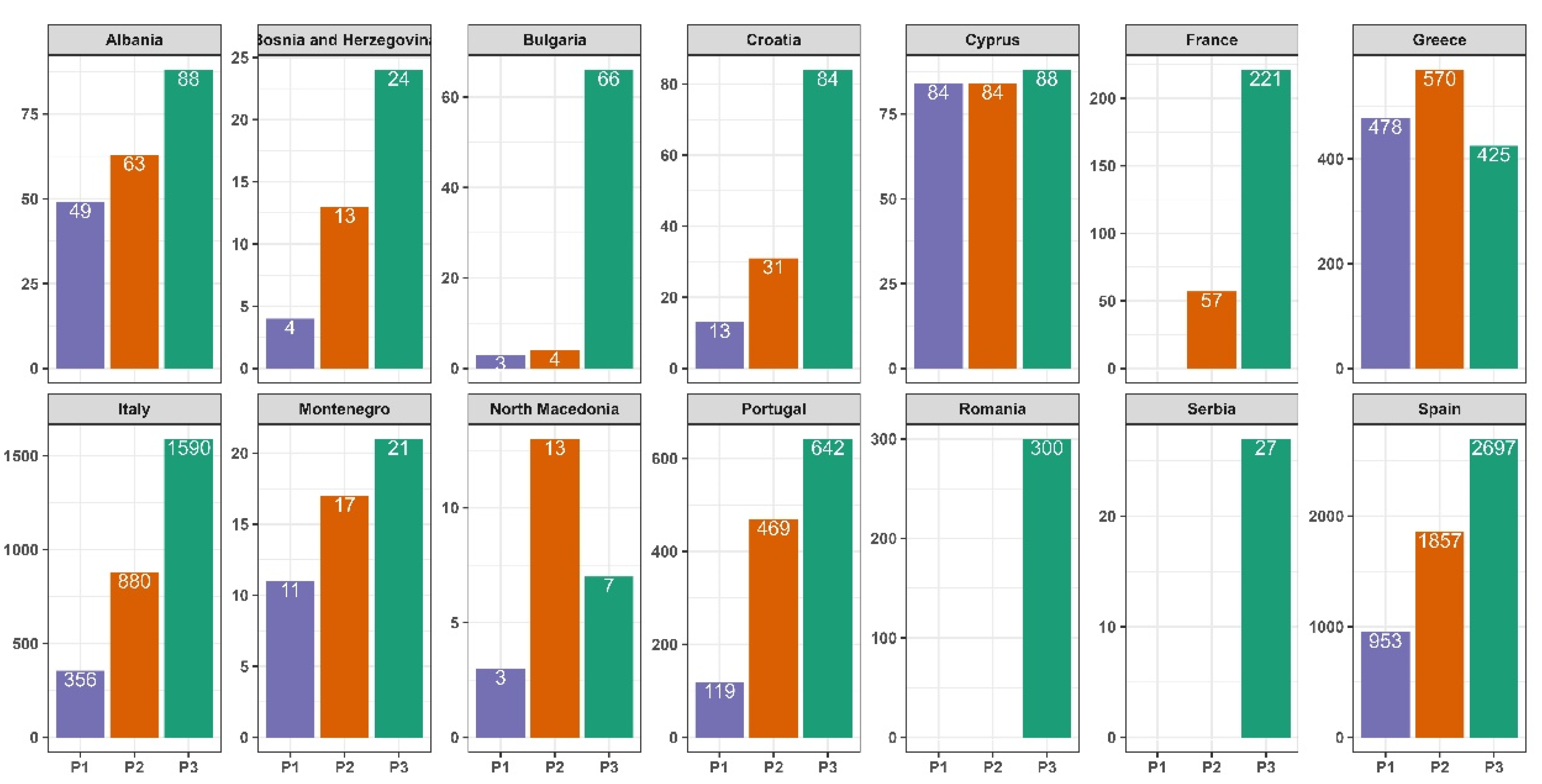

- Charalampopoulos, I.; Polychroni, I.; Psomiadis, E.; Nastos, P. Spatiotemporal Estimation of the Olive and Vine Cultivations’ Growing Degree Days in the Balkans Region. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromatis, T.; Voulanas, D. Evaluating ERA-Interim, Agri4Cast and E-OBS Gridded Products in Reproducing Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Precipitation and Drought over a Data Poor Region: The Case of Greece. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 2118–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photiadou, C.; Fontes, N.; Graça, A.R.; Schrier, G. van der ECA&D and E-OBS: High-Resolution Datasets for Monitoring Climate Change and Effects on Viticulture in Europe. BIO Web Conf. 2017, 9, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, S.; Todorovic, M.; Tanasijevic, L.; Pereira, L.S.; Pizzigalli, C.; Lionello, P. Climate Change and Mediterranean Agriculture: Impacts on Winter Wheat and Tomato Crop Evapotranspiration, Irrigation Requirements and Yield. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 147, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraslis, I.; Dalezios, N.R.; Alpanakis, N.; Tziatzios, G.A.; Spiliotopoulos, M.; Sakellariou, S.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Dercas, N.; Domínguez, A.; Martínez-López, J.A.; et al. Remotely Sensed Agroclimatic Classification and Zoning in Water-Limited Mediterranean Areas towards Sustainable Agriculture. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Duchêne, E.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Barbeau, G.; De Rességuier, L.; Lacombe, T.; Parker, A.; Saurin, N.; van Leeuwen, C. Grapevine Phenology in France: From Past Observations to Future Evolutions in the Context of Climate Change. 2017.

- Ferretti, C.G. A New Geographical Classification for Vineyards Tested in the South Tyrol Wine Region, Northern Italy, on Pinot Noir and Sauvignon Blanc Wines. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 108, 105737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, I. Agrometeorological Conditions and Agroclimatic Trends for the Maize and Wheat Crops in the Balkan Region. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromatis, T.; Georgoulias, A.K.; Akritidis, D.; Melas, D.; Zanis, P. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Seasonal Crop-Specific Climatic Indices under Climate Change in Greece Based on EURO-CORDEX RCM Simulations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, A.-E.; Man, T.C.; Vâtcă, S.D.; Kobulniczky, B.; Stoian, V. Refining the Spatial Scale for Maize Crop Agro-Climatological Suitability Conditions in a Region with Complex Topography towards a Smart and Sustainable Agriculture. Case Study: Central Romania (Cluj County). Sustainability 2020, 12, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teslić, N.; Zinzani, G.; Parpinello, G.P. Climate Change Trends, Grape Production, and Potential Alcohol Concentration in Wine from the “Romagna Sangiovese” Appellation Area (Italy. Theor Appl Clim. 2018, 131, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vâtcă, S.D.; Stoian, V.A.; Man, T.C.; Horvath, C.; Vidican, R.; Gâdea, Ștefania; Vâtcă, A. ; Rotaru, A.; Vârban, R.; Cristina, M.; et al. Agrometeorological Requirements of Maize Crop Phenology for Sustainable Cropping—A Historical Review for Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adão, F.; Campos, J.C.; Santos, J.A.; Malheiro, A.C.; Fraga, H. Relocation of Bioclimatic Suitability of Portuguese Grapevine Varieties under Climate Change Scenarios. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Santos, J.A. Future Scenarios for Viticultural Zoning in Europe: Ensemble Projections and Uncertainties. Int J Biometeorol 2013, 57, 909–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimia, L.M.; Patriche, C.V.; Roșca, B. Climate Change Impact on Climate Suitability for Wine Production in Romania. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 133, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán, E.; Pino-Otín, M.R. Using Bioclimatic Indicators to Assess Climate Change Impacts on the Spanish Wine Sector. Atmospheric Res. 2023, 286, 106660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysiak, G.P.; Szot, I. The Use of Temperature Based Indices for Estimation of Fruit Production Conditions and Risks in Temperate Climates. Agriculture 2023, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, R.; Ortega, J.F.; Hernandez, D.; del Campo, A.; Moreno, M.A. Combined Use of Agro-Climatic and Very High-Resolution Remote Sensing Information for Crop Monitoring. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2018, 72, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.A.; Aires, F. Assessment of the Agro-Climatic Indices to Improve Crop Yield Forecasting. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 253–254, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramesh, V.; Kumar, P.; Shamim, M.; Ravisankar, N.; Arunachalam, V.; Nath, A.J.; Mayekar, T.; Singh, R.; Prusty, A.K.; Rajkumar, R.S.; et al. Integrated Farming Systems as an Adaptation Strategy to Climate Change: Case Studies from Diverse Agro-Climatic Zones of India. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Dinis, L.-T.; Correia, C.; Moriondo, M.; Leolini, L.; Dibari, C.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; et al. A Review of the Potential Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Options for European Viticulture. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozny, M.; Hajkova, L.; Vlach, V.; Ouskova, V.; Musilova, A. Changing Climatic Conditions in Czechia Require Adaptation Measures in Agriculture. Climate 2023, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhomme, R. Bases and Limits to Using ‘Degree.Day’ Units. Eur. J. Agron. 2000, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgubin, G.; Swingedouw, D.; Dayon, G.; García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Ollat, N.; Pagé, C.; van Leeuwen, C. The Risk of Tardive Frost Damage in French Vineyards in a Changing Climate. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 250–251, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.K.; Cortázar-Atauri, I.G.D.; Leeuwen, C.V.; Chuine, I. General Phenological Model to Characterise the Timing of Flowering and Veraison of Vitis Vinifera L. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2011, 17, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster, G.S.; Wilhelm, W.W. Growing Degree-Days: One Equation, Two Interpretations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1997, 87, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y. A Critique of the Heat Unit Approach to Plant Response Studies. Ecology 1960, 41, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrátilová, M.; Beranová, M.; Severová, L.; Šrédl, K.; Svoboda, R.; Abrhám, J. The Impact of Climate Change on the Sugar Content of Grapes and the Sustainability of Their Production in the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Zhang, X.; Chen, K.; Feng, Y.; O’Brien, T. Observed Long-Term Trends for Agroclimatic Conditions in Canada. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenealy, L.; Reighard, G.; Rauh, B.; Bridges Jr., W. Predicting Peach Maturity Dates in South Carolina with a Growing Degree Day Model. Acta Hortic. 2015, 479–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asseng, S.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; Rötter, R.P.; Lobell, D.B.; Cammarano, D.; Kimball, B.A.; Ottman, M.J.; Wall, G.W.; White, J.W.; et al. Rising Temperatures Reduce Global Wheat Production. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tao, F.; Zhang, Z. Changes in Extreme Temperatures and Their Impacts on Rice Yields in Southern China from 1981 to 2009. Field Crops Res. 2016, 189, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Su, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shan, Y.; Deng, M. Chapter Six - Comprehensive and Quantitative Analysis of Growth Characteristics of Winter Wheat in China Based on Growing Degree Days. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press, 2020; Vol. 159, pp. 237–273.

- Anandhi, A. Growing Degree Days—Ecosystem Indicator for Changing Diurnal Temperatures and Their Impact on Corn Growth Stages in Kansas. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorieva, E. Evaluating the Sensitivity of Growing Degree Days as an Agro-Climatic Indicator of the Climate Change Impact: A Case Study of the Russian Far East. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M. Climatic Change Impacts on Growing Degree Days and Climatologically Suitable Cropping Areas in the Eastern Nile Basin. Agric. Res. 2021, 10, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukal, M.S.; Irmak, S. U.S. Agro-Climate in 20th Century: Growing Degree Days, First and Last Frost, Growing Season Length, and Impacts on Crop Yields. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6977–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernáth, S.; Paulen, O.; Šiška, B.; Kusá, Z.; Tóth, F. Influence of Climate Warming on Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Phenology in Conditions of Central Europe (Slovakia. Plants 2021, 10, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalampopoulos, I.; Droulia, F.; Tsiros, I.X. Projecting Bioclimatic Change over the South-Eastern European Agricultural and Natural Areas via Ultrahigh-Resolution Analysis of the de Martonne Index. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortiñas, J.A.; Fernández-González, M.; González-Fernández, E.; Vázquez-Ruiz, R.A.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J.; Aira, M.J. Phenological Behaviour of the Autochthonous Godello and Mencía Grapevine Varieties in Two Designation Origin Areas of the NW Spain. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 265, 109221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Pedroso, V.; Henriques, C.; Matos, A.; Reis, S.; Santos, J.A. Modelling the Phenological Development of Cv. Touriga Nacional and Encruzado in the Dão Wine Region, Portugal. OENO One 2021, 55, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Brisson, N.; Ollat, N.; Jacquet, O.; Payan, J.-C. Asynchronous Dynamics of Grapevine (“Vitis Vinifera”) Maturation: Experimental Study for a Modelling Approach. OENO One 2009, 43, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillakis, M.G.; Doupis, G.; Kapetanakis, E.; Goumenaki, E. Future Shifts in the Phenology of Table Grapes on Crete under a Warming Climate. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 318, 108915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, N.; Pržić, Z.; Tešević, V.; Vukovic, A.; Mutavdžić, D.; Vujadinović, M.; Ruml, M. Variation of Aromatic Compounds in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ Wine under the Influence of Different Weather Conditions and Harvest Dates. Acta Hortic. 2016, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žnidaršič, Z.; Gregorič, G.; Sušnik, A.; Pogačar, T. Frost Risk Assessment in Slovenia in the Period of 1981–2020. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufos, G.; Mavromatis, T.; Koundouras, S.; Fyllas, N.M. Viticulture: Climate Relationships in Greece and Impacts of Recent Climate Trends: Sensitivity to “Effective” Growing Season Definitions. In Advances in Meteorology, Climatology and Atmospheric Physics; Helmis, C.G., Nastos, P.T., Eds.; Springer Atmospheric Sciences; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 555–561 ISBN 978‐3‐642‐29171‐5. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, F.; Chiamolera, F.M.; Hueso, J.J.; González, M.; Cuevas, J. Heat Unit Requirements of “Flame Seedless” Table Grape: A Tool to Predict Its Harvest Period in Protected Cultivation. Plants 2021, 10, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Santos, J. a. Daily Prediction of Seasonal Grapevine Production in the Douro Wine Region Based on Favourable Meteorological Conditions. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- QGIS Development Team QGIS Geographic Information System 2009.

- Schultze, S.R.; Sabbatini, P. Implications of a Climate-Changed Atmosphere on Cool-Climate Viticulture. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2019, 58, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omazić, B.; Prtenjak, M.T.; Prša, I.; Vozila, A.B.; Vučetić, V.; Karoglan, M.; Kontić, J.K.; Prša, Ž.; Anić, M.; Šimon, S.; et al. Climate Change Impacts on Viticulture in Croatia: Viticultural Zoning and Future Potential. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 5634–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriche, C.V.; Irimia, L.M. Mapping the Impact of Recent Climate Change on Viticultural Potential in Romania. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinoni, J.; Vogt, J.; Barbosa, P. European Degree-Day Climatologies and Trends for the Period 1951-2011. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malheiro, A.C.; Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Pinto, J.G. Climate Change Scenarios Applied to Viticultural Zoning in Europe. Clim. Res. 2010, 43, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.A.; Malheiro, A.C.; Pinto, J.G.; Jones, G.V. Macroclimate and Viticultural Zoning in Europe: Observed Trends and Atmospheric Forcing. Clim. Res. 2012, 51, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, J. p.; Végvári, Z. Future of Winegrape Growing Regions in Europe. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2016, 22, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardell, M.F.; Amengual, A.; Romero, R. Future Effects of Climate Change on the Suitability of Wine Grape Production across Europe. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriondo, M.; Jones, G.V.; Bois, B.; Dibari, C.; Ferrise, R.; Trombi, G.; Bindi, M. Projected Shifts of Wine Regions in Response to Climate Change. Clim Chang 2013, 119, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethling, E.; Barbeau, G.; Bonnefoy, C.; Quénol, H. Change in Climate and Berry Composition for Grapevine Varieties Cultivated in the Loire Valley. Clim. Res. 2012, 53, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtural, S.K.; Gambetta, G.A. Global Warming and Wine Quality: Are We Close to the Tipping Point? OENO One 2021, 55, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciocco, K.; Davis, R.; Jones, G. Climate and Bordeaux Wine Quality: Identifying the Key Factors That Differentiate Vintages Based on Consensus Rankings. J. Wine Res. 2014, 25, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.E.; Dimon, R.A.; Jones, G.V.; Bois, B. The Effect of Climate on Burgundy Vintage Quality Rankings. OENO One 2019, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccel, E.; Zollo, A.L.; Mercogliano, P.; Zorer, R. Simulations of Quantitative Shift in Bio-Climatic Indices in the Viticultural Areas of Trentino (Italian Alps) by an Open Source R Package. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 127, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotti, L.; Potentini, R.; Casturà, T.; Lanari, V.; Lattanzi, T.; Dottori, E.; Silvestroni, O. Analysis of Verdicchio Harvest Data in Matelica Appellation Area during the 1989-2016 Time Series. BIO Web Conf. 2022, 44, 02009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, G.; Ferrari, F.; Trevisan, M.; Bavaresco, L. Impact of Climatic Conditions on the Resveratrol Concentration in Blend of Vitis Vinifera L. Cvs. Barbera and Croatina Grape Wines. Molecules 2021, 26, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelini, S.; Tomada, S.; Kadison, A.E.; Pichler, F.; Hinz, F.; Zejfart, M.; Iannone, F.; Lazazzara, V.; Sanoll, C.; Robatscher, P.; et al. Modeling Malic Acid Dynamics to Ensure Quality, Aroma and Freshness of Pinot Blanc Wines in South Tyrol (Italy). OENO One 2021, 55, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teslić, N.; Vujadinović, M.; Ruml, M.; Antolini, G.; Vuković, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Ricci, A.; Versari, A. Climatic Shifts in High Quality Wine Production Areas, Emilia Romagna, Italy, 1961-2015. Clim. Res. 2017, 73, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilesco, G.; Coletta, A.; Tarricone, L.; Alba, V. Bioclimatic Characterization Relating to Temperature and Subsequent Future Scenarios of Vine Growing across the Apulia Region in Southern Italy. Agriculture 2023, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massano, L.; Fosser, G.; Gaetani, M.; Bois, B. Assessment of Climate Impact on Grape Productivity: A New Application for Bioclimatic Indices in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanari, V.; Zacconi, F.M.; Illuminati, S.; Gigli, L.; Canullo, G.; Lattanzi, T.; Dottori, E.; Silvestroni, O. Seasonal Evolution Impact on Montepulciano Grape Ripening. BIO Web Conf. 2022, 44, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigl, E.L.; Tasser, E.; Williams, S.; Tappeiner, U. Defining Suitable Zones for Viticulture on the Basis of Landform and Environmental Characteristics: A Case Study from the South Tyrolean Alps.; 2017. 29 March.

- Moral, F.J.; Rebollo, F.J.; Paniagua, L.L.; García, A.; de Salazar, E.M. Application of Climatic Indices to Analyse Viticultural Suitability in Extremadura, South-Western Spain. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 123, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, F.J.; Aguirado, C.; Alberdi, V.; García-Martín, A.; Paniagua, L.L.; Rebollo, F.J. Future Scenarios for Viticultural Suitability under Conditions of Global Climate Change in Extremadura, Southwestern Spain. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-Rey, A.; González-Fernández, E.; Fernández-González, M.; Lorenzo, M.N.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J. Climate Change Impacts Assessment on Wine-Growing Bioclimatic Transition Areas. Agriculture 2020, 10, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, M.N.; Taboada, J.J.; Lorenzo, J.F.; Ramos, A.M. Influence of Climate on Grape Production and Wine Quality in the Rías Baixas, North-Western Spain. Reg. Environ. Change 2013, 13, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de Toda, F.; Ramos Martín, M.C. (Ma C. Variability in Grape Composition and Phenology of “Tempranillo” in Zones Located at Different Elevations and with Differences in the Climatic Conditions. 2019.

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Llacer, E.; Revert, J.; Esteve, M.D.; Climent, M.D.; Palau, D.; Gómez, I. Early Defoliation Reduces Cluster Compactness and Improves Grape Composition in Mandó, an Autochthonous Cultivar of Vitis Vinifera from Southeastern Spain. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 167, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Santos, J.A.; Malheiro, A.C.; Oliveira, A.A.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Jones, G.V. Climatic Suitability of Portuguese Grapevine Varieties and Climate Change Adaptation. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, R.F.; Lin, Y.-P.; Ansari, A. Regional Climate Change Effects on the Viticulture in Portugal. Environments 2023, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Atauri, I.G. de C.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Santos, J.A. Viticulture in Portugal: A Review of Recent Trends and Climate Change Projections. OENO One 2017, 51, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, G.; Dejeu, L. Climate Change Trends in Some Romanian Viticultural Centers. 2021, 5, nr. 2, 2016, 24–27.

- Bucur, G.M.; Cojocaru, G.A.; Antoce, A.O. The Climate Change Influences and Trends on the Grapevine Growing in Southern Romania: A Long-Term Study. BIO Web Conf. 2019, 15, 01008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donici, A.; Mari, S.; Baniţă, C.; Urmuzache, R. Evaluation of the Viticultural Potential from the Pietroasa Wine-Growing Region in the Context of Current Climatic Changes. Sci. Pap. Ser. B Hortic. 2021, 65, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ruml, M.; Vuković, A.; Vujadinović, M.; Djurdjević, V.; Ranković-Vasić, Z.; Atanacković, Z.; Sivčev, B.; Marković, N.; Matijašević, S.; Petrović, N. On the Use of Regional Climate Models: Implications of Climate Change for Viticulture in Serbia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 158–159, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujadinović Mandić, M.; Vuković Vimić, A.; Ranković-Vasić, Z.; Đurović, D.; Ćosić, M.; Sotonica, D.; Nikolić, D.; Đurđević, V. Observed Changes in Climate Conditions and Weather-Related Risks in Fruit and Grape Production in Serbia. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovic, D.; Nikolic, N.; Kostic, L.; Todic, S.; Nikolic, M. Early Leaf Removal Increases Berry and Wine Phenolics in Cabernet Sauvignon Grown in Eastern Serbia. Agronomy 2021, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trbic, G.; Popov, T.; Djurdjevic, V.; Milunovic, I.; Dejanovic, T.; Gnjato, S.; Ivanisevic, M. Climate Change in Bosnia and Herzegovina According to Climate Scenario RCP8.5 and Possible Impact on Fruit Production. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović-Cvetković, T.; Sredojević, M.; Natić, M.; Grbić, R.; Akšić, M.F.; Ercisli, S.; Cvetković, M. Exploration and Comparison of the Behavior of Some Indigenous and International Varieties (Vitis Vinifera L.) Grown in Climatic Conditions of Herzegovina: The Influence of Variety and Vintage on Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Grapes. Plants 2023, 12, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzanova, M.; Atanassova, S.; Atanasov, V.; Grozeva, N. Content of Polyphenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Potential of Some Bulgarian Red Grape Varieties and Red Wines, Determined by HPLC, UV, and NIR Spectroscopy. Agriculture 2020, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajović Šćepanović, R.; Wendelin, S.; Raičević, D.; Eder, R. Characterization of the Phenolic Profile of Commercial Montenegrin Red and White Wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 2233–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, R.; Petric, I.V.; Jusup, J.; Banović, M. Geographical Discrimination of Croatian Wines by Stable Isotope Ratios and Multielemental Composition Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoglan, M.; Prtenjak, M.T.; Šimon, S.; Osrečak, M.; Anić, M.; Kontić, J.K.; Andabaka, Ž.; Tomaz, I.; Grisogono, B.; Belušić, A.; et al. Classification of Croatian Winegrowing Regions Based on Bioclimatic Indices. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 50, 01032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omazić, B.; Telišman Prtenjak, M.; Bubola, M.; Meštrić, J.; Karoglan, M.; Prša, I. Application of Statistical Models in the Detection of Grapevine Phenology Changes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 341, 109682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vršič, S.; Pulko, B.; Kraner Šumenjak, T.; Šuštar, V. Trends in Climate Parameters Affecting Winegrape Ripening in Northeastern Slovenia. Clim. Res. 2014, 58, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potisek, M.; Krebelj, A.; Šuklje, K.; Škvarč, A.; Čuš, F. Viticultural and Oenological Characterization of Muscat a Petits Grains Blancs and Muscat Giallo Clones. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2023, 24, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuklje, K.; Krebelj, A.J.; Vaupotič, T.; Čuš, F. Effect of Cluster Thinning within the Grapevine Variety “Welschriesling” on Yield, Grape Juice and Wine Parameters. Mitteilungen Klosterneubg. 2022, 72, 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kopali, A.; Libohova, Z.; Teqja, Z.; Owens, P.R. Bioclimatic Suitability for Wine Vineyards in Mediterranean Climate—Tirana Region, Albania. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2021, 86, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufos, G.; Mavromatis, T.; Koundouras, S.; Fyllas, N.M.; Jones, G.V. Viticulture-Climate Relationships in Greece: The Impacts of Recent Climate Trends on Harvest Date Variation. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 1445–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Dimou, P.; Jones, G.; Kalivas, D.; Koufos, G.; Mavromatis, T. Harvest Dates, Climate, and Viticultural Region Zoning in Greece. Proc. 10th Int. Terroir Congr. 7-10 July 2014 2014, 55–60.

- Koufos, G.C.; Mavromatis, T.; Koundouras, S.; Jones, G.V. Response of Viticulture-Related Climatic Indices and Zoning to Historical and Future Climate Conditions in Greece. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 2097–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xyrafis, E.G.; Fraga, H.; Nakas, C.T.; Koundouras, S. A Study on the Effects of Climate Change on Viticulture on Santorini Island. OENO One 2022, 56, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazoglou, G.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Koundouras, S. Climate Change Projections for Greek Viticulture as Simulated by a Regional Climate Model. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 133, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, S.; Metafa, M.; Kotseridis, Y.; Paraskevopoulos, I.; Kallithraka, S. Amino Acid Content of Agiorgitiko (Vitis Vinifera L. Cv.) Grape Cultivar Grown in Representative Regions of Nemea. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 2041–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, E.; Templalexis, C.; Lentzou, D.; Biniari, K.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Fountas, S. Do Soil and Climatic Parameters Affect Yield and Quality on Table Grapes? Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copper, A.W.; Collins, C.; Bastian, S.; Johnson, T.; Koundouras, S.; Karaolis, C.; Savvides, S. Vine Performance Benchmarking of Indigenous Cypriot Grape Varieties Xynisteri and Maratheftiko: This Article Is Published in Cooperation with the XIIIth International Terroir Congress November 17-18 2020, Adelaide, Australia. Guest Editors: Cassandra Collins and Roberta De Bei. OENO One 2020, 54, 935–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).