1. Introduction

The advent of large-scale Artificial Intelligence (AI) models has marked a transformative era in computational learning, with their unprecedented capacity for data processing and pattern recognition shaping the trajectory of technological advancement. As these behemoths of AI continue to burgeon, their integration into diverse societal sectors underscores a critical need. Cognition alignment ensures that AI models not only perform tasks efficiently but also resonate with the intricacies of human thought processes. Cognition-aligned models promise to deliver more intuitive interactions, enhance decision-making compatibility, and foster trust, as their operational logic mirrors the cognitive frameworks humans use to understand, reason, and contextualise. In essence, aligning AI with human cognition is not merely a technical aspiration but a foundational element for the harmonious coexistence of AI systems and their human counterparts in an increasingly automated world.

The notion of cognition alignment in AI is deeply rooted in the rich soil of cognitive psychology and constructivist theory. Cognitive psychology, a discipline that develops from understanding mental processes, posits that human cognition is a complex interplay of various mental activities. This field has long been fascinated with how people perceive, remember, think, speak, and solve problems. Constructivist theory complements this by suggesting that learners construct knowledge through an active learning process rather than absorbing information passively. It emphasises the learner’s critical role in making sense of new information by linking it to prior knowledge and experiences stored in memory.

Cognition alignment theory extrapolates these principles into the realm of AI. It advocates for the design of AI systems that ‘learn’ as much as humans do – by connecting new data to pre-existing knowledge frameworks and by abstracting underlying principles through reflection. The theory underscores the importance of AI systems being able to not only recall information but also to apply it to novel situations, predict future scenarios, and adaptively learn from experiences. This approach ensures that AI can engage with tasks in a way that is reminiscent of human problem-solving and decision-making processes, with the flexibility and creativity that are hallmarks of human cognition.

In essence, cognition alignment theory in AI calls for the development of intelligent systems that go beyond pattern recognition and data analysis. It seeks to create AI that can understand the context of data, draw upon a wealth of experiences (real or simulated), make inferences, and anticipate future needs or actions — much like a human would when faced with new and complex challenges. It is a pursuit to bridge the gap between human and machine learning processes, to create AI that not only computes but comprehends.

Zero-Shot Learning (ZSL) refers to a classification problem where the learning algorithm must correctly classify objects or data points that it has not seen during training. It is a machine learning technique where the model is expected to infer information about unseen classes by only learning about seen classes, usually through some form of transfer learning or by exploiting commonalities between classes. In ZSL, the model typically uses attributes or descriptions of objects to make these inferences. For example, if a model is trained on a dataset of animal images that includes various seen classes like ‘tiger’, ‘elephant’, and ‘horse’, it might later be tested on its ability to recognise an ‘antelope’, which it has never seen before, by using learned attributes such as ‘four legs’, ‘hooves’, and ‘horns’.

ZSL emerges as an ideal testbed for the study of cognition alignment precisely because it encompasses many of the challenges and intricacies of replicating human cognitive processes in AI systems. The paradigm of ZSL fundamentally relies on the ability of neural networks to engage in visual perception, not merely by recognising patterns through brute computational power but by understanding and extrapolating concepts in the absence of explicit prior examples.

This learning paradigm calls upon advanced knowledge representation techniques that are vital to human cognition, such as the identification of visual attributes, the interpretation of free text, and the application of knowledge encapsulated in ontological taxonomies. Furthermore, zero-shot learning utilises similes and exemplars that are inherently tied to the way humans draw analogies and learn from abstract examples. These methodologies are cornerstones in the extraction and emulation of human cognitive strategies, allowing AI to go beyond simple task execution to demonstrate an understanding of context and meaning.

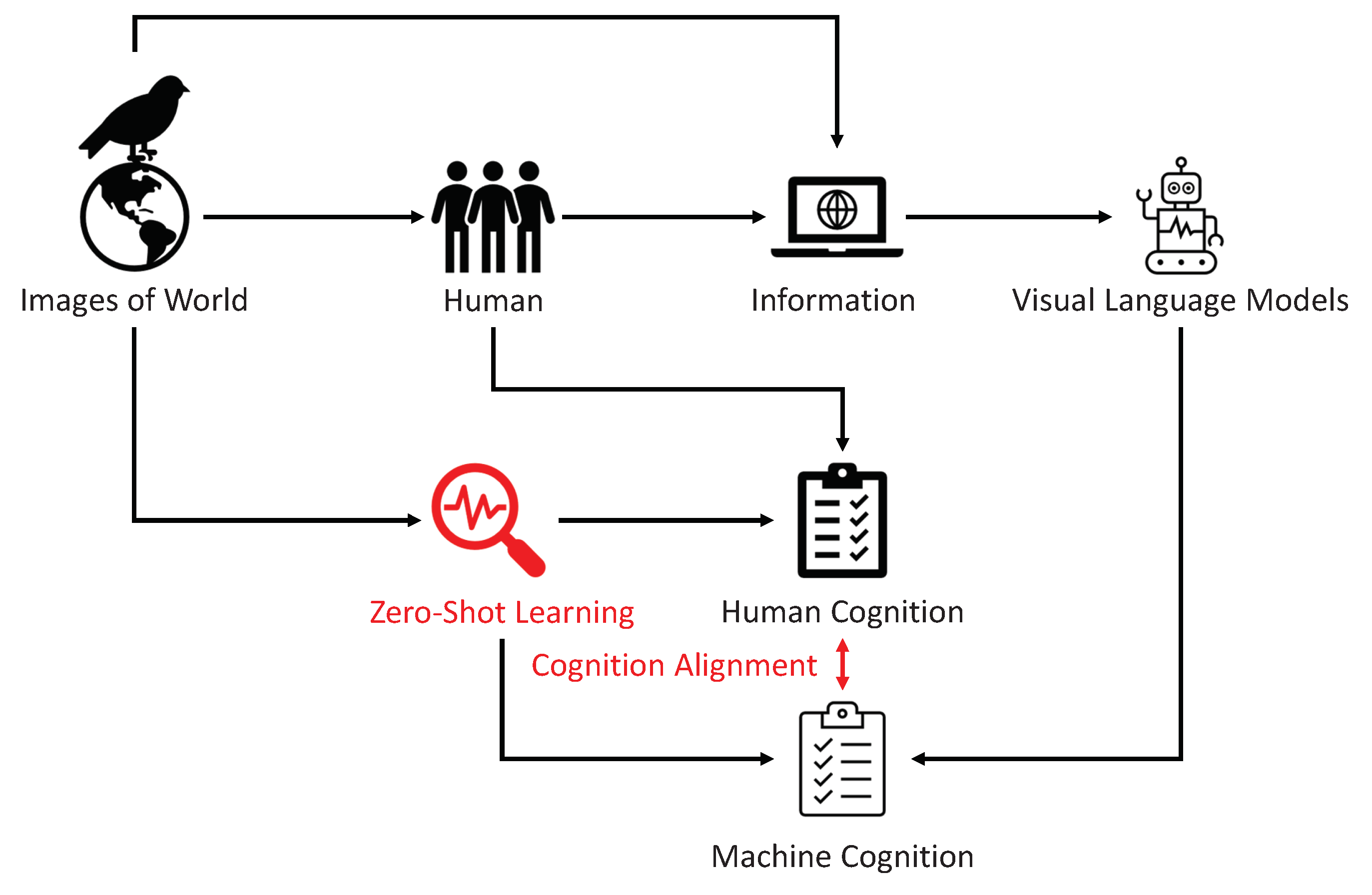

As shown in

Figure 1, in ZSL, the neural network is tasked with the challenge of transferring its learnt knowledge to entirely new classes, samples, tasks or domains it has never encountered during training. The success of this transfer hinges on the model’s alignment with human cognitive representations — its ability to generalise and apply abstract principles to new and unseen data. Hence, ZSL does not just assess an AI’s learning efficiency; it evaluates the AI’s cognitive congruence with human thought patterns. It is in this rigorous testing of generalisation capabilities that the true measure of cognition alignment is found, making zero-shot learning a prime candidate for advancing our understanding of how AI can not only mimic but also meaningfully engage with human cognitive processes.

While traditional ZSL is usually concerned with classification tasks, Zero-Shot Instance Retrieval (ZSIR) [

1] is about retrieving particular instances of data that match a given description or query, without having seen examples of that specific category or instance during training. It’s a more specific task where the model needs to understand and match a complex query to instances in an unseen category. The difference lies in the output and the nature of the task: ZSL is about classifying an instance into a category not seen during training, while ZSIR is about retrieving all relevant instances that match a zero-shot query, even when the model has not been trained with any examples from the category of the query. Essentially, ZSL is about "what" an object is, and ZSIR is about finding "where" or "which" objects fulfil the criteria described in the query.

ZSIR requires the model to have a sophisticated understanding of attributes and their relationships, as it may need to retrieve specific instances based on descriptions that involve unseen combinations of attributes. This can be a more complex task since the model must deal with a potentially larger and more nuanced space of attributes and must be able to rank instances in terms of their relevance to a query. Our contributions are summarised as follows:

We introduce a novel framework that utilises Zero-Shot Instance Retrieval (ZSIR) as a method to study and analyse the cognitive alignment of large visual language models. This approach allows us to simulate and evaluate how AI interprets and processes visual information in a manner that parallels human cognitive abilities, particularly in scenarios where the model encounters data it has not been explicitly trained to recognise.

A key innovation of our research is the development of a unified similarity function specifically designed to quantify the level of cognitive alignment in AI systems. This function provides a metric that correlates the AI’s interpretations with human-like cognition, offering a quantifiable measure of the AI’s ability to align its processing with human thought patterns.

The effectiveness of our proposed similarity function is thoroughly tested through extensive experiments on the CUB and SUN datasets. Our results demonstrate that the function is versatile and robust across different forms of knowledge representation, including visual attributes and free text generated by large AI models. This versatility is critical as it reflects the level of cognition alignment between humans and AI.

Our experiments not only establish the validity of the proposed similarity functions but also showcase the enhanced performance of our model in the context of ZSIR tasks. The model demonstrates superior capabilities compared to existing state-of-the-art models, marking a significant advancement in the field.

2. Related Work

The recent surge in research on cognition-aligned Large Language Models (LLMs) reflects a growing interest in developing AI systems that can reason, understand and interact in ways that align with human cognitive processes. This literature review insights from key papers in this domain and discusses related Zero-Shot Learning (ZSL) techniques that are related to our work.

2.1. Cognition-Alignment AI

Cognition alignment has become an emerging trend in the AI research community. The sharp-rising intelligence capacity of LLMs has caused both technical and social concerns. Xu et al. (2023) [

2] address the challenges in aligning LLMs with human preferences, proposing a risk taxonomy and policy framework for personalized feedback. Their work underscores the complexity of aligning LLMs with diverse human values and preferences. Another trend of conition alignment studies focuses on enhancing reasoning in LLMs. Wang et al. (2023) [

3] and Lester et al. (2021) [

4] focus on improving reasoning capabilities in LLMs. An Alignment Fine-Tuning (AFT) paradigm has been introduced to address the Assessment Misalignment problem in LLMs, enhancing their reasoning abilities. Lester et al.’s work on CogAlign emphasizes aligning textual neural representations with cognitive language processing signals, highlighting the importance of cognitive alignment in LLMs. For wider concerns and applications in lingustic and social domain, papers by Xu et al. (2023) [

5], Sengupta et al. (2023) [

6], and Zhang et al. (2023) [

7] delve into the alignment of LLMs in specific cultural and linguistic contexts. Xu et al. focus on the values of Chinese LLMs. Sengupta et al. develop Arabic-centric LLMs, and Zhang et al. bridge cross-lingual alignment through interactive translation. Another research direction of cognition alignment of AI focuses on the emotioanal and safety guarantee of AI models. Wang et al. (2023) [

8] and Bhardwaj et al. (2023) [

9] explore the emotional intelligence of LLMs and their safety alignment. Wang et al. assess LLMs’ emotional intelligence, crucial for effective communication, while Bhardwaj et al. propose red-teaming techniques for safety alignment. Considering cognition-alignment in the contexts of LLMs and AI is still a new research topic that just started since the begining of 2023, there are a few survey papers summarises the progression and challenges in this domain. Liu et al. (2023) [

10] and Petroni et al. (2019) [

11] provide comprehensive surveys on LLM alignment and their potential as knowledge bases, respectively. Liu et al., discuss key dimensions crucial for assessing LLM trustworthiness. In contrast, Petroni et al. explore the capability of LLMs to store and recall factual knowledge in 2019. Be comparing the differences and progression of the two survey papers from 2019 and 2023, we found one of the related topics of cognition alignment to our work aims to apply the aligned cognition representation to improve the performance of AI training and machine learning. Gu et al. (2023) [

12] and Kirk et al. (2023) [

13] present application-specific advancements in LLMs. Gu et al. focus on zero-shot NL2SQL generation, combining pre-trained language models with LLMs, while Kirk et al. discuss the personalisation of LLMs within societal bounds.

As a short summary, the review highlights the diverse approaches and challenges in aligning LLMs with human cognition, values, and preferences. From enhancing reasoning capabilities to addressing cultural specificity and emotional intelligence, these studies collectively contribute to the development of more aligned, effective, and ethically sound LLMs. In line with our research focus in this paper, we also explore the new paradigm that can use well-aligned AI cognition to seamlessly improve the efficiency and work satisfactory for human ontological engineering, i.e., brain-storming for conceptualisation, data collection, labelling and tagging class embedding, descriptions and attributes, annotation via crowd-sourcing approaches, validation the ontological structure via theoretical analysis and discussion, etc. In construst to all the existing work as mentioned above, our unique contribution of this paper is to introduce the ZSL task ZSIR as a quantitative measurement for the level of cognition alignment between AI and human. This is considered to be a bilateral reciprocal benefit. For one thing, it is crucial to understand how well the AI LLMs are aligned to human cognition so that the data annotation and interpretation work can be reliably handed over to the machine. Otherwise, the poisoned biased cognition of LLMs can exaggerate the risk when it is applied to downstream supervised learning tasks. From the other perspective, a well-aligned cognition AI can efficiently improve the model performance in downstream tasks. At such an early stage, our work aims to establish a healthy paradigm that both assesses the level of cognition-alignment and also applied the method to improve the downstream task, e.g., ZSL image recognition.

2.2. Zero-Shot Learning

Zero-shot learning (ZSL) has undergone significant advancements, marked by key contributions that have shaped its current state. The journey began with Larochelle et al. [

14], who introduced the concept of zero-data learning, proposing a method to learn new tasks without training data, a foundational idea in ZSL. The first mention of ZSL was given by Palatucci et al. [

15], who explored semantic output codes in ZSL, demonstrating how semantic information could be used to recognize classes unseen during training. Lampert et al. [

16] then introduced an attribute-based approach for detecting unseen object classes, a seminal work that showed the effectiveness of shared attributes in identifying novel objects, which popularised ZSL paradigms in computer vision domain.

The integration of deep learning with semantic embeddings was significantly advanced by Frome et al. [

17] with the DeViSE model, which combined visual and textual information for ZSL. Norouzi et al. [

18] further contributed by combining multiple semantic embeddings, improving the accuracy of ZSL models. The concept of synthesized classifiers, which was crucial for generalizing from seen to unseen classes, was introduced by Changpinyo et al. [

19]. A comprehensive evaluation of various ZSL approaches was presented by Xian et al. [

20], establishing a benchmark for future research in the field. This was crucial for understanding the strengths and weaknesses of different ZSL methodologies. Liu et al. [

21] addressed the problem of generalized zero-shot learning, where the test set contains both seen and unseen classes, proposing a deep calibration network to balance the learning between these classes.

Wang et al. [

22] conducted a detailed survey that provided an extensive overview of methodologies, datasets, and challenges in ZSL, offering insights into the state of the field. This survey was instrumental in summarizing the progress and directing future research efforts. In recent years, the focus in ZSL has shifted towards more complex and realistic scenarios. This includes the integration of unsupervised and semi-supervised techniques, the use of generative models to synthesize features for unseen classes, and the exploration of cross-modal ZSL. These advancements aim at improving the scalability, robustness, and practical applicability of ZSL models.

Zero-shot learning has been applied to various downstream tasks, each marked by key milestone papers that have significantly advanced the field. Khandelwal et al. [

23] proposed a simple yet effective method for zero-shot detection and segmentation, outperforming more complex architectures. This work is pivotal in demonstrating the effectiveness of straightforward approaches in ZSL for object detection and segmentation. Chen et al. [

24] described a vision-based method for analyzing excavators’ productivity using zero-shot learning. This method identifies activities of construction machines without pre-training, showcasing the practical application of ZSL in real-world scenarios. Díaz et al. [

25] presented a novel zero-shot prototype recurrent convolutional network for human activity recognition via channel state information. This method enhances cross-domain transferability, a crucial aspect of ZSL in activity recognition. Nag et al. [

26] designed a transformer-based framework, TranZAD, for zero-shot temporal activity detection. This framework streamlines the detection of unseen activities, demonstrating the potential of transformers in ZSL.

Zero-Shot Instance Retrieval via Dominant Attributes [

1] presents a methodology that resonates with the core strengths and challenges in the development of cognitively aligned LLMs. It is a novel approach to semantic searching in the context of zero-shot learning. This paradigm is particularly relevant for measuring the cognitive alignment of large language models (LLMs). Firstly, the paper’s focus on semantic searching aligns well with the cognitive capabilities of LLMs, which relies on understanding and processing semantic information. Secondly, the use of dominant attributes in zero-shot retrieval mirrors the way LLMs leverage contextual cues and attributes to generate responses, making it a fitting method to evaluate their cognitive alignment. Thirdly, the approach emphasizes affordability, which is crucial in making advanced semantic searching techniques more accessible, a goal that aligns with the democratisation efforts in AI and LLMs. In addition, the zero-shot aspect of the retrieval process is akin to the generalisation capabilities of LLMs, making it an ideal testbed to assess how well these models can adapt to new, unseen data while maintaining semantic coherence. In contrast to ZSIR model research, this paper focuses on introducing ZSIR to measure the cognition alignment via the visual perception task of image retrieval. Both synthetic attributes and class descriptions are explored and compared against the human cognition representation. To our best knowledge, this is the first-ever paradigm that can quantitatively measure the cognition-alignment between AI and human via a visual perception tasks and ontological engineering.

3. Methodology

In traditional Zero-Shot Learning (ZSL), denotes the visual space, where each instance represents a visual instance. Correspondingly, represents the label space for seen classes, and represents the label space for unseen classes, where . The objective of ZSL is to learn a mapping function that can accurately associate unseen visual instances with their corresponding category label. Because the distribution between and is disjoint, then association between the two domains is required. and denote the perception and cognition functions to process visual features in and labels in , respectively. While collecting category attributes consumes considerable human cognitive labour, it is infeasible to collect instance-level annotation for large datasets. In other words, existing ZSL can only map an unseen instance to a category while ZSIR requires retrieving the specific instance in the category. Our approach adopts both human and AI-generated attribute representation so that each attribute dimension corresponds to a data-driven feature that captures explicit and latent attributes pertinent to cognitive alignment.

To measure Human-AI cognitive alignment, we introduce a cognitive alignment function , which measures the degree of alignment between the AI’s data-driven representation of visual instance and human cognitive processes. The function assesses how closely the AI’s output for an unseen instance x aligns with human-like cognition, e.g., visual attributes, free-texts and knowledge graph when classifying it into an unseen class .

The methodology concentrates on optimising the cognitive alignment function by adjusting the mapping from both visual and attribute spaces to the latent instance attribute, ensuring that AI’s interpretation of visual data not only aligns with human cognition in recognising unseen classes but also adheres to the cognitive processes humans employ in categorising and understanding visual stimuli.

3.1. Cognition Representation

In addressing the challenge of cognitive alignment using the realm of ZSL, our approach begins with the fundamental premise that visual stimuli serve as a common informational ground. We operate under the assumption that both AI systems and humans perceive the same visual information, yet their methods of processing and interpreting this information lead to divergent cognitive representations. Traditional human cognition in ZSL research encompasses a variety of forms, including visual attributes, free-text descriptions, and ontological taxonomies such as similes. A critical challenge in this context is the unification of these diverse cognitive representations into a coherent framework that AI can understand and utilise while minimising the need for extensive manual labour typically required for such tasks.

To bridge this gap, we propose the integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT to facilitate the automated generation of labels and annotations . These models can provide a scalable and efficient means of translating the rich paradigms of human cognitive representations into a format that AI systems can process. In this paper, we consider the most two frequently used paradigms as a comparison:

Automated Attribute Generation: Using LLMs to automatically generate descriptive attributes for visual data, thereby providing a structured and detailed attribute set that mirrors human perception.

Free-Text Description Synthesis: LLMs can be employed to create comprehensive free-text descriptions of visual stimuli. These narratives offer a deeper, more contextual understanding of the images, akin to how humans might describe them.

Through these methods, we aim to significantly reduce the manual labour involved in the annotation process while ensuring that the AI system’s understanding of visual information aligns closely with human cognitive processes. This approach not only enhances the cognitive alignment of AI models but also paves the way for more intuitive and human-like AI interactions and interpretations in the field of ZSL.

For example, we estimate the total hours humans might take to build up the "SUN attribute database". The process can be broken down into three main stages: 1) Developing a Taxonomy of 102 Discriminative Attributes: This initial stage involves crowd-sourced human studies. The complexity here depends on the methodology (e.g., surveys, workshops, etc.) and the level of agreement required to finalise the list. For estimation, we can assume that this stage requires several rounds of surveys and analysis. Assuming an initial setup, literature review, and preparation phase: 40 hours (5 work days).Each round of survey and analysis: 20 hours. Assuming at least 3 rounds for a robust taxonomy: hours. 2) Building the SUN Attribute Database: This involves annotating over 700 categories and 14,000 images. Each image needs to be reviewed and annotated with relevant attributes of the established taxonomy. Time to annotate one image: This can vary significantly, but we can just assume an average of 2 minutes per image. Total time for one annotator: minutes = 28,000 minutes. 3) Annotation by Three Human Annotators: The total effort will be multiplied by three, as each image is annotated by three different people to ensure accuracy and consistency. The total annotation time is hours. So, the estimated total time would be approximately 100+1401=1501 hours. This is a rough estimation and actual time may vary based on the efficiency of the process, the complexity of the images, and the proficiency of the annotators.

While the advance of LLM can significantly reduce the time to build up the class association, hierarchy and attribute annotation, we are curious whether the cognition of LLM can align well with the time-consuming ontological engineering processed by human annotators. In this paper, we consider the following paradigms that have been widely adopted in previous ZSL research.

Class Embedding: Automatic description provided by AI for each given class.

AI-Revised Human Attributes: By incorporating the class names and human-designed attributes, AI revises the attribute list and makes the words more related to visual perception for the image retrieval task.

AI-Generated Attributes: AI create attributes that are associated to the class names without any constrained.

ZSL-Contexualised AI Attributes: Based on the AI-Generated Attributes, the prompting further constrains the task for ZSL purposes that focuses on improving the visual perception association and generalisation for unseen classes and instances.

AI-revised human attributes aim to testify whether AI modal can enhance the human-designed attributes by its own cognition. The new list combines specific elements that are more directly applicable to individual scenes, such as ’Traffic Intensity’ or ’Flora Types’, which were aspects highlighted in the human-generated list. While maintaining specificity, these attributes are still broad enough to apply across various scenes, unlike some of the very niche attributes in the human-generated list. The attributes balance physical characteristics (e.g., ’Rock Formations’, ’Weather Elements’), emotional or atmospheric qualities (e.g., ’Emotional Atmosphere’, ’Safety Perception’), and functional aspects (e.g., ’Commercial Features’, ’Conservation Efforts’). The list includes attributes related to human experiences and activities, reflecting the way people interact with and perceive different environments. Attributes related to sensory experiences (e.g., ’Aroma Characteristics’, ’Acoustic Qualities’) are included, emphasising the multisensory nature of human scene perception. By combining specificity, broad applicability, and a balance of different types of descriptors, this AI-revised human attributes list aims to offer a more comprehensive and nuanced framework for scene classification than the human-generated list. It acknowledges the complexity of scenes and the multifaceted ways in which they can be described and understood.

While the first baseline is more constrained by human cognition inputs, e.g., the class descriptions and human-designed attributes, the later two baselines provide more freedom for AI to incorporate its own cognition to create task-specific attributes. AI-generated attributes create a free attribute list using only given class names. This baseline can best reflect the true AI cognition based on concept-level association. However, our cognition alignment is based on the assumption that both AI and humans aim to describe the same visual perception. The validation of the cognition alignment is based on whether the multi-sourced cognition representation by human, AI, and contrain can lead to accurate image retrieval in the ZSIR task. Therefore, in the final proposed paradigm, the prompting information constrains the AI to create more visual-specific attributes, and the list should be applied to both seen and unseen classes to testify the generalisation of the association.

The final proposed ZSL-contextualised AI attributes focus on improving the generalisation, visual discriminators, balance of abstract and concrete levels, relevance to scene understanding and compatibility with the downstream visual-semantic modelling. These attributes are broad enough to be applicable across a wide range of scenes, which is essential for zero-shot learning where the model needs to generalise from seen to unseen classes. The attributes are chosen for their potential to be visually discriminative. They capture key aspects of scenes that can distinguish one class from another. The list balances abstract qualities (like ’tranquil’ or ’bustling’) with concrete, visually identifiable features (like ’wooden’ or ’mountainous’). This mix is crucial for a model that needs to understand and categorise scenes it has not been explicitly trained on. Attributes are relevant to understanding and describing scenes, which is the primary goal of the classifier. They cover a range of aspects including material properties, environmental characteristics, and human-made vs. natural elements. These attributes are conducive to the creation of visual-semantic models, as they can be easily linked to visual data and semantic descriptions, forming a bridge between the visual appearance of a scene and the language-based descriptors. This revised list is designed to optimise the effectiveness of zero-shot learning models in classifying images by focusing on attributes that are both descriptive and discriminative, enhancing the model’s ability to make accurate predictions on unseen data.

3.2. Latent Instance Attributes Discovery

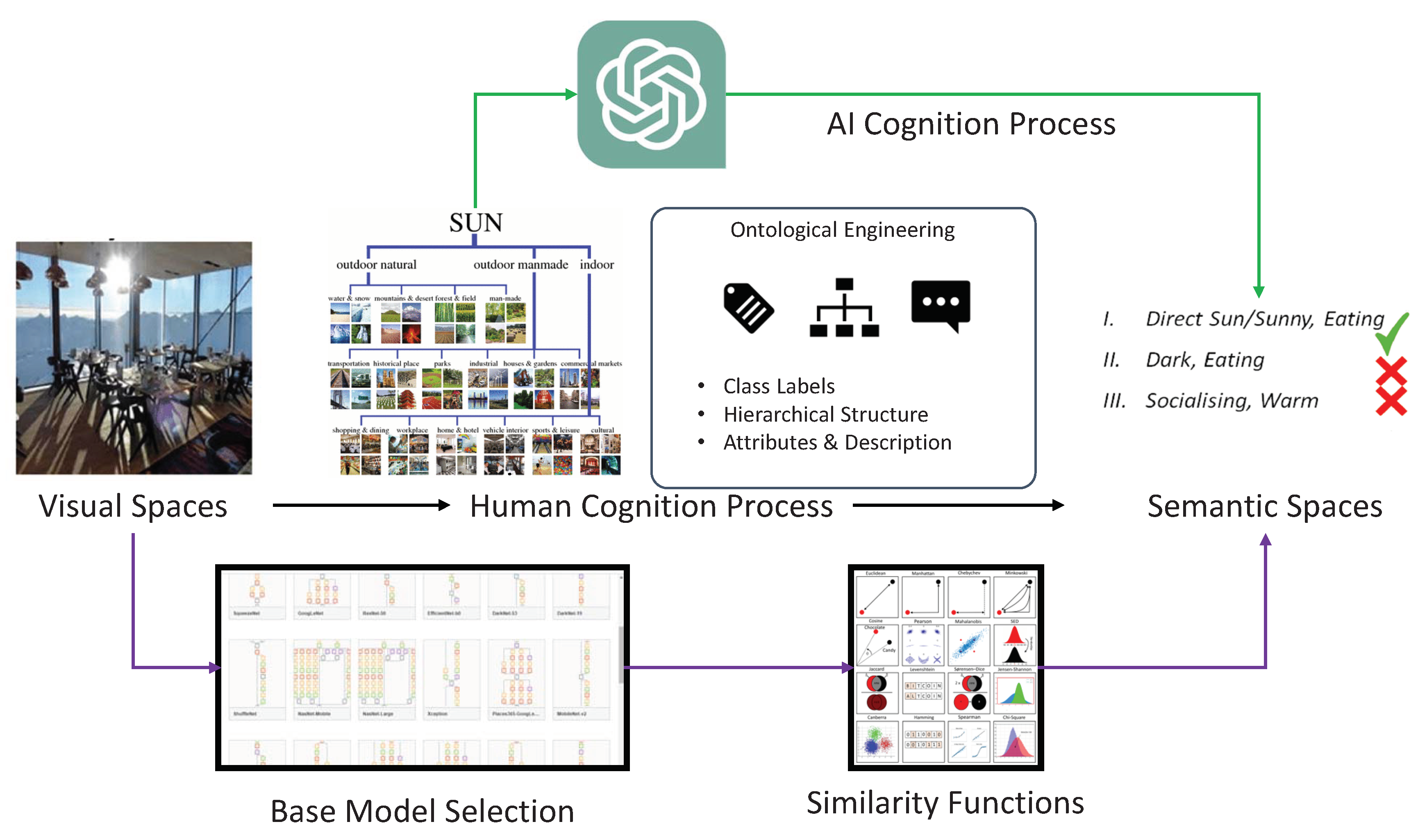

As shown in

Figure 2, for both ZSL and ZSIR, it is essential to establish class association so that the training set of seen class samples can be generalised to the unseen domain. Visual spaces need to be projected into the semantic spaces created by either human annotators or AI models, as mentioned above. Class embedding is the baseline approach that has been widely used in text-based ZSL methods. The generated class descriptions are then encoded by traditional word embedding, intermediate BERT model, and GPT3 LLMs.

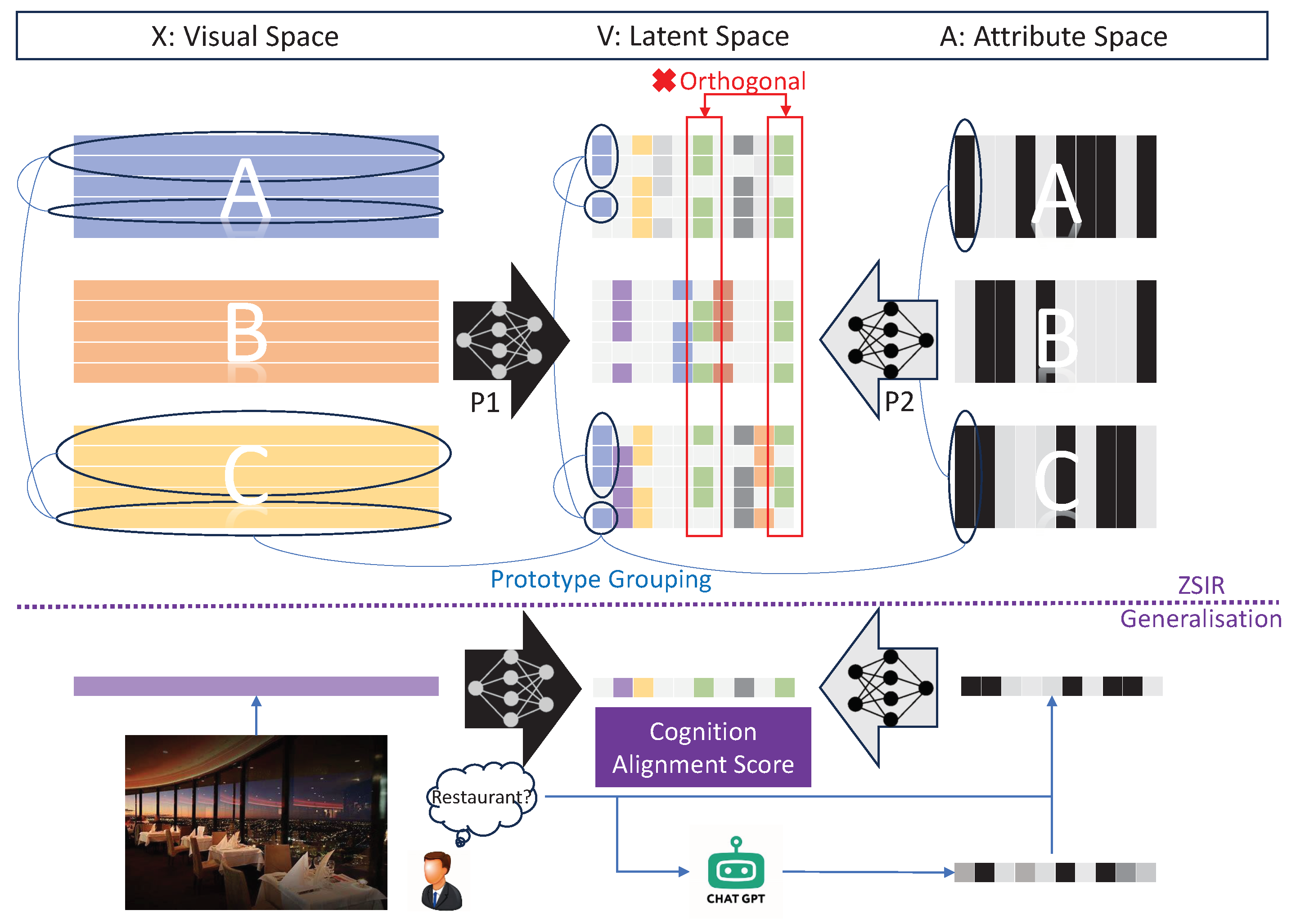

Once class embedding is achieved, ZSL models extract visual features using base models and learn to project into the semantic spaces via similarity functions. As shown in

Figure 3, ZSIR is different from ZSL since the task requires to differentiate instances in the same class while ZSL aims to reduce the inner-class distances and enhance the inter-class distances. Therefore, the semantic representation of attributes or word embedding in ZSIR needs to reflect the detailed differences between instances in the same class. Although the datasets of SUN and CUB have provided both class-level and instance-level attributes, it is a very challenging task for the AI-generated approaches. We follow the paradigm of Latent Instance Attributes Discovery [

1] which is formalised as follows:

where

and

are the loss functions to learn a mapping from the visual space and attribute space to a shared latent space to discover the instance-level visual semantic attributes. The latent space is constrained by an orthogonal projection so that the discovered attributes in

are uncorrelated. Each dimension of the discovered attribute can be considered as an independent visual-semantic vocabulary formally written as follows, which ensures each latent attribute dimension

is compact and not redundant.

k is a hyper-parameter that controls the dimension of the latent space:

Note that the cardinality

equals to the sample size of images but the cardinality

is the number of categories. Therefore, we would expect a reduced rank from visual to the latent space and an increased rank from the attribute space to the latent space. In other words, for each attribute provided by either humans or LLMs, there are richer image examples to support the concept. In this paper, we introduce a Prototype Grouping (PG) method to 1) encourage more diverse prototypes of each visual-semantic attribute can be learnt 2) encourage inter-class association can be achieved so that the ZSIR generalisation to unseen domain can be achieved. Firstly, to discover the intrinsic relationship between training samples

, we construct a graphical adjacency matrix

for

:

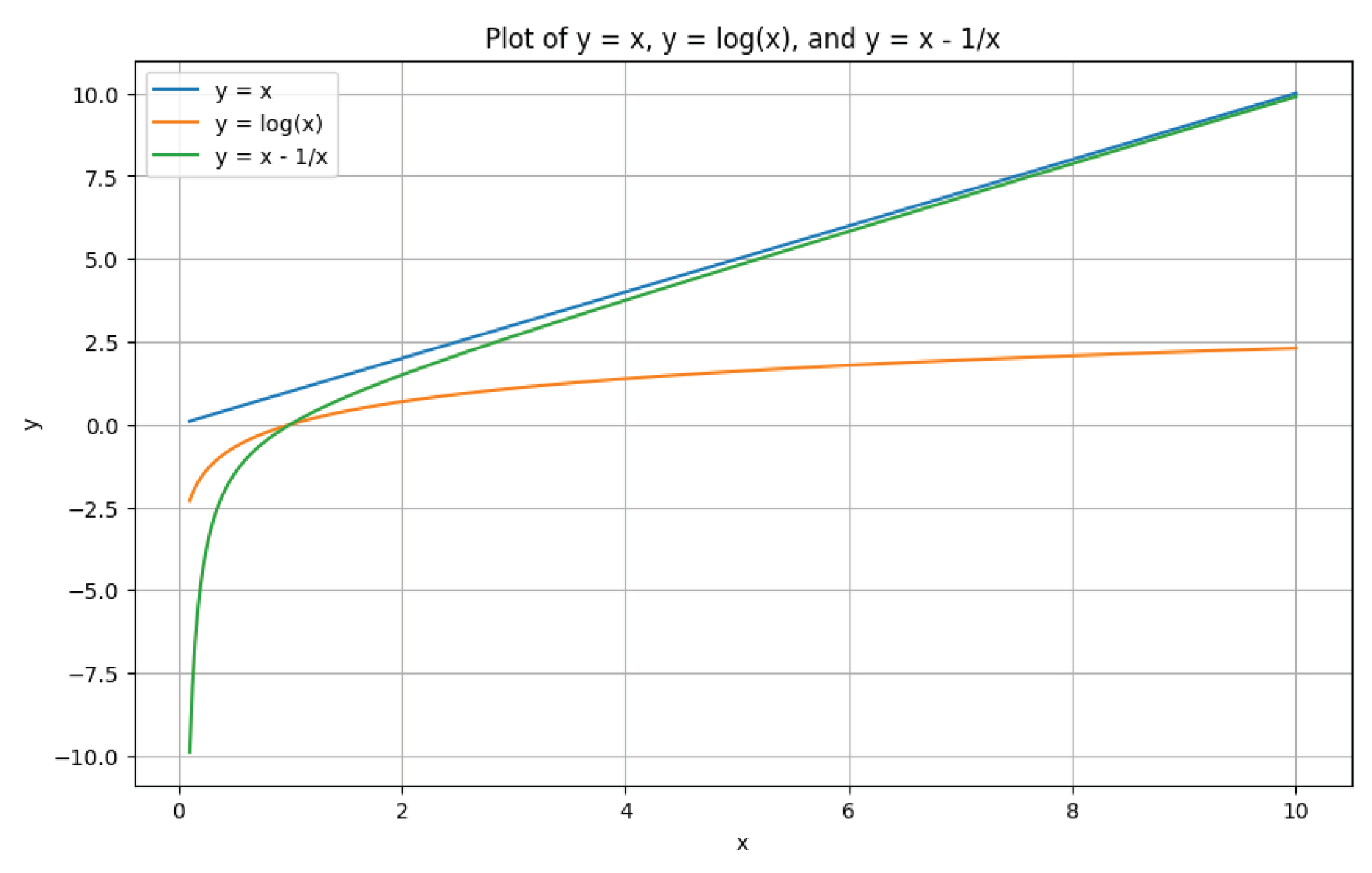

where

is a non-linear mapping function that can keep large similarity responses while eliminating small similarity responses to ensure connected neighbours have strong intrinsic associations.

is a threshold hyper-parameter that ensures the neighbourhood connection in

is stronger so that the learnt prototypes can eliminate outliers. The property of

is shown in

Figure 4.

Similar to the visual space, we apply the same adjacency matrix approach for the attribute space. As illustrated in

Figure 3,

is a low-rank matrix since the rank equals to the number of class

C which is much smaller than the sample size

N. As a result, the adjacency matrix will have a block of connections for the same class samples and the inter-class associations are also reflected at the category level. Finally, the latent instance attribute discovery consists of two mapping functions as follows:

where for both domain

and

,

is the enhanced adjacency matrix by identity matrix

I and

is the degree matrix with values on the matrix diagonal and zeros elsewhere.

is the normalised adjacency matrix so that the graphical condition can be applied to the projections from visual and attribute spaces

and

to provide the prototype grouping condition.

and

are the dimensions of raw visual and attribute spaces

and

and

k is the dimension of the shared latent visual attribute space

.

3.3. Cognition Alignment via ZSIR

Using both the orthogonality and PG constraints, we can project the visual perception

and semantic cognition

into the shared latent space to achieve the Cognition Alignment (CA). The equation serves for our essential promises that different cognition representations in the attributes are aligned with the same visual stimuli in

.

Optimisation Strategy: Solving the above Eq.

5 is a dynamic NP-hard problem because either visual or attribute projection to the latent space is unknown. In this paper, we propose an alternating optimisation strategy which is summarised in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1: LIAD Optimisation for ZSIR Cognition Alignment |

|

Input: Visual feature of training images ; Attributes of seen classes ; |

| Test images from unseen classes with the attributes ; |

|

Output: Gallery and query instances and ; |

| 1. Initialise: and ; |

| 2. While and not converge: |

| 3. ; |

| 4. for iter ∈ 0, 1, ..., MaxIter: |

| 5. ; |

| 6. ; |

| 7. for iter ∈ 0, 1, ..., MaxIter: |

| 8. ; |

| 9. Return: and according to Eq. 4. |

To calculate the cognition-alignment score via ZSIR, the process involves evaluating the system’s ability to correctly match queries with their corresponding instances in a gallery, where both queries and gallery instances belong to unseen classes . This evaluation is conducted under two distinct scenarios: Attributes to Image (A2I) and Image to Attributes (I2A). In the A2I scenario, the system is provided with a set of attributes as the query. The objective is to accurately retrieve the visual instance in the image gallery that best matches these attributes. Conversely, in the I2A scenario, the system is given a query image and must predict its identity by matching it to the exact attribute instance in the gallery. For both scenarios, the initial step involves inferring the full instance attribute vectors from the given class attributes, along with the visual features of the query, are then projected into the orthogonal space. The retrieval process occurs within this space, where the system attempts to find the closest match between the query’s projected representation and the projected representations of instances in the gallery.

The cognition-alignment score is derived from the accuracy of these retrieval tasks. It quantifies the system’s proficiency in aligning its data-driven representations (inferred attribute vectors and visual features) with human cognitive processes (dominant attributes and visual identity). High accuracy in retrieval, reflected in a high cognition-alignment score, indicates effective alignment, demonstrating the system’s capability to generalise and accurately interpret unseen classes based on the cognitive congruence between its learned representations and human-understandable attributes.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experiment Setup

Datasets: The assessment of our approach was conducted using two established benchmarks for ZSIR: the SUN dataset introduced by Patterson et al. and the CUB dataset presented by Wah et al., with detailed results presented in

Table 1. The visual features leveraged in our study are derived from [

27]. For the purpose of word embedding, our study utilises the conventional GoogleNews-vectors-negative300, a model crafted by Mikolov et al. in 2013, which underwent training on a segment of the Google News dataset encompassing approximately 100 billion words. Our methodology adheres to the traditional splits between seen and unseen classes typical in zero-shot learning (ZSL) frameworks [

20], with an emphasis placed on evaluating ZSIR capabilities. In scenarios involving Image-to-Attribute (I2A) and Attribute-to-Image (A2I) conversions, attributes and images of unseen instances are interchangeably utilised as gallery and query sets.

Evaluation Methodology: The primary metric for our evaluation is the hit rate accuracy in (%), which assesses if a given query’s corresponding instance ranks within the top selections. To provide a comprehensive overview, we calculate the average hit rates across various classes, reflecting the general performance trend.

Implementation Details: We employ a cross-validation approach for all hyper-parameters within the LIAD on the training dataset. Given the absence of attribute usage during training, we introduce a 5-fold cross-validation strategy tailored for the CA challenge. This involves initially determining across the entire training dataset, which represents the dominant attributes’ inferred outputs, denoted as . The training classes are subsequently segmented into five groups. For each group, we calculate a new pair of projections, and , utilising the remaining four groups. The obtained is then applied to map visual instances from the validation group into . The retrieval performance is assessed by comparing and for unseen classes.

Table 2.

Comparison of human attributes, AI-revised human attributes, AI-generated attributes and ZSL-contextualised AI.

Table 2.

Comparison of human attributes, AI-revised human attributes, AI-generated attributes and ZSL-contextualised AI.

| Human Attributes |

AI-revised Human Attributes |

AI-Generated Attributes |

ZSL-Contextualised AI Attributes |

| ’sailing/ boating’ |

Open Space |

Natural |

Natural |

| ’driving’ |

Enclosed Space |

Man-made |

Man-Made |

| ’biking’ |

Natural Landscape |

Indoor |

Indoor |

| ’transporting things or people’ |

Man-made Structures |

Outdoor |

Outdoor |

| ’sunbathing’ |

Urban Environment |

Urban |

Urban |

| ’vacationing/ touring’ |

Rural Setting |

Rural |

Rural |

| ’hiking’ |

Water Presence |

Modern |

Bright |

| ’climbing’ |

Vegetation Density |

Historical |

Dim |

| ’camping’ |

Color Palette |

Spacious |

Colorful |

| ’reading’ |

Textural Qualities |

Cramped |

Monochrome |

| ’studying/ learning’ |

Lighting Conditions |

Bright |

Spacious |

| ’teaching/ training’ |

Weather Elements |

Dim |

Cramped |

| ’research’ |

Architectural Style |

Colorful |

Populated |

| ’diving’ |

Historical Context |

Monochrome |

Deserted |

| ’swimming’ |

Modern Elements |

Busy |

Vegetated |

| ’bathing’ |

Artistic Features |

Tranquil |

Barren |

| ’eating’ |

Functional Aspects |

Populated |

Watery |

| ’cleaning’ |

State of Maintenance |

Deserted |

Dry |

| ’socializing’ |

Population Density |

Greenery |

Mountainous |

| ’congregating’ |

Noise Level |

Barren |

Flat |

| ’waiting in line/ queuing’ |

Movement Dynamics |

Waterbody |

Forested |

| ’competing’ |

Activity Presence |

Dry |

Open |

| ’sports’ |

Cultural Significance |

Mountainous |

Enclosed |

| ’exercise’ |

Geographical Features |

Flat |

Architectural |

| ’playing’ |

Seasonal Characteristics |

Forested |

Naturalistic |

| ’gaming’ |

Time of Day |

Open |

Ornate |

| ’spectating/ being in an audience’ |

Material Dominance |

Enclosed |

Simple |

| ’farming’ |

Symmetry |

Architectural |

Cluttered |

| ’constructing/ building’ |

Asymmetry |

Naturalistic |

Minimalistic |

| ’shopping’ |

Spaciousness |

Ornate |

Artistic |

| ’medical activity’ |

Clutter |

Simple |

Functional |

| ’working’ |

Tranquility |

Cluttered |

Symmetrical |

| ’using tools’ |

Bustle |

Minimalistic |

Asymmetrical |

| ’digging’ |

Accessibility |

Artistic |

Traditional |

| ’conducting business’ |

Seclusion |

Functional |

Contemporary |

| ’praying’ |

Safety Perception |

Symmetrical |

Luxurious |

| ’fencing’ |

Risk Elements |

Asymmetrical |

Modest |

| ’railing’ |

Sensory Stimuli |

Traditional |

Cultivated |

| ’wire’ |

Emotional Atmosphere |

Contemporary |

Wild |

| ’railroad’ |

Privacy Level |

Luxurious |

Paved |

| ’trees’ |

Connectivity |

Modest |

Unpaved |

| ’grass’ |

Isolation |

Cultivated |

Vibrant |

| ’vegetation’ |

Ecological Elements |

Wild |

Muted |

| ’shrubbery’ |

Industrial Presence |

Paved |

Textured |

| ’foliage’ |

Commercial Features |

Unpaved |

Smooth |

| ’leaves’ |

Educational Aspects |

Vibrant |

Reflective |

| ’flowers’ |

Recreational Facilities |

Muted |

Matte |

| ’asphalt’ |

Religious Symbols |

Textured |

Elevated |

| ’pavement’ |

Cultural Diversity |

Smooth |

Ground-level |

| ’shingles’ |

Historical Monuments |

Reflective |

Aerial |

Table 3.

Augmented attributes example: AI assigned class-attribute association value and the rationale explained by AI why the association makes sense.

Table 3.

Augmented attributes example: AI assigned class-attribute association value and the rationale explained by AI why the association makes sense.

| Attributes |

Value |

Association to the class Abbey as an example |

| Natural |

0 |

(Abbeys are man-made structures, though they may be situated in natural settings.) |

| Indoor |

1 |

(Abbeys typically have significant indoor areas.) |

| Outdoor |

1 |

(They also have outdoor components like courtyards.) |

| Urban |

0 |

(Generally, abbeys are in rural or secluded settings, but some may be in urban areas.) |

| Bright |

0 |

(Traditional abbeys might have a dimmer, more solemn interior.) |

| Colorful |

0 |

(Abbeys often have a more muted, monastic color scheme.) |

| Spacious |

1 |

(They usually have spacious interiors like chapels and halls.) |

| Populated |

0 |

(Abbeys are often associated with tranquility and seclusion.) |

| Vegetated |

1 |

(Many abbeys have gardens or are located in green settings.) |

| Watery |

0 |

(Unless located near a water body, which is not typical for all abbeys.) |

| Mountainous |

0 |

(This is location-dependent.) |

| Forested |

0 |

(Again, location-dependent.) |

| Open |

1 |

(They often have open courtyards.) |

| Enclosed |

1 |

(Enclosed structures like cloisters are common.) |

| Architectural |

1 |

(Abbeys are known for their distinctive architecture.) |

| Ornate |

1 |

(Many abbeys are ornately decorated, especially older ones.) |

| Simple |

0 |

(Abbeys are typically not simple in design.) |

| Artistic |

1 |

(Abbeys often contain artistic elements like stained glass.) |

| Symmetrical |

1 |

(Many have symmetrical architectural designs.) |

| Modest |

1 |

(Abbeys are often modest in terms of luxury.) |

| Cultivated |

1 |

(Gardens or cultivated lands are common.) |

| Paved |

1 |

(Pathways and internal floors are typically paved.) |

| Textured |

1 |

(Stone walls, woodwork, etc.) |

| Elevated |

0 |

(Dependent on the specific location.) |

| Underground |

0 |

(Some abbeys may have crypts or basements.) |

| Foggy |

0 |

(Location-specific.) |

| Daytime |

1 |

(Abbeys are typically functional during the day.) |

| Weathered |

1 |

(Many abbeys are old and show signs of weathering.) |

| Secluded |

1 |

(Abbeys are often in secluded locations.) |

| Quiet |

1 |

(Associated with quietude and peace.) |

| Cool |

1 |

(Stone buildings often have a cool interior.) |

4.2. ZSIR Main Results

Table 4 presents a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed method for Zero-Shot Instance Retrieval (ZSIR) using human attributes, benchmarked against both baseline and state-of-the-art approaches on the SUN Attribute and CUB Dataset. Our method significantly outperforms existing methods across all ranks, showcasing its effectiveness in ZSIR tasks. Baseline methods such as DAP, ALE, ESZSL, LatEm, and LIAD show varying degrees of success, with LIAD previously leading with scores up to 28.7% at Rank1 and 86.2% at Rank50. In comparison, our approach not only surpasses these baselines but also demonstrates superior performance against additional methods like CCA and Siamese Network, particularly noted in the more challenging scenario of retrieving images based on attributes (A2I) and vice versa (I2A).

A key innovation in our method is the introduction of the Prototype Grouping (PG) technique, which significantly enhances the diversity of prototypes for each visual-semantic attribute and strengthens inter-class associations. This is evident in the performance leap observed when comparing our method’s orthogonal-only and PG-only variants to the combined approach. Specifically, our full method achieves remarkable improvements, reaching up to 35.5% at Rank1 and 92.8% at Rank50 for the SUN Attribute Dataset, outstripping the PG-only variant’s 28.9% at Rank1 and 87.7% at Rank50, and the orthogonal-only variant’s 26.6% at Rank1 and 79.9% at Rank50.

These results underscore the efficacy of our method in generalising ZSIR to unseen domains through enhanced attribute representation and cognitive alignment. The Prototype Grouping method, in particular, stands out as a pivotal advancement, enabling more nuanced and contextually rich retrieval outcomes that closely align with human cognitive processes. This breakthrough underscores the potential of our approach in bridging the gap between AI-driven visual recognition and human-like understanding. The evaluation of our methods ensures reliable alignment between visual and cognition spaces and the method can generalised to unseen classes.

4.3. Ablation Study

In our ablation study, we meticulously analyse the impact of two critical components in our framework: Orthogonal Projection and Prototype Grouping (PG). This analysis is grounded in the comparative performance of our method against established baselines, as delineated in the results table.

Effect of Orthogonal Projection The influence of Orthogonal Projection on Zero-Shot Instance Retrieval (ZSIR) performance is evident when comparing the outcomes of Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), the Siamese Network, LIAD, and our method with orthogonal projection only. CCA, which focuses on extracting correlation information between visual features and attributes without imposing specific constraints, offers a foundational comparison point. The Siamese Network, leveraging a deep architecture based on triplet contrastive learning, aims to minimize distances within classes while maximizing distances between classes, offering a nuanced approach to learning separable feature spaces. LIAD, incorporating an orthogonal constraint alongside augmented attributes, introduces a structured approach to aligning visual and semantic spaces. Our method, when employing orthogonal projection exclusively, demonstrates a marked improvement over these baselines, underscoring the efficacy of orthogonal constraints in enhancing cognitive alignment and retrieval accuracy. Specifically, the orthogonal-only variant of our method outperforms CCA and the Siamese Network across all ranks, indicating the orthogonal projection’s pivotal role in achieving more discriminative and well-aligned feature representations.

Effect of Prototype Grouping The Prototype Grouping (PG) mechanism’s contribution is highlighted through a comparison between our method’s PG variant and the baseline approaches. The PG approach is designed to foster more diverse and representative prototypes for each visual-semantic attribute, thereby facilitating better generalization to unseen classes through enhanced inter-class associations. The results table reveals that our method with PG significantly surpasses the performance of all baseline methods, including the orthogonal projection variant. This superiority is particularly pronounced at higher ranks, suggesting that PG effectively captures the complex underlying structures of the data, enabling more accurate retrieval of unseen instances. The comparison underscores PG’s critical role in bridging the semantic gap between visual features and attributes, thereby bolstering the model’s zero-shot retrieval capabilities.

The table results provide a quantitative testament to the individual and combined impacts of Orthogonal Projection and Prototype Grouping. Notably, our method that integrates both components outstrips all other approaches, consistently achieving the highest retrieval accuracy across the board. This comprehensive performance boost, observed across different datasets and ranking metrics, attests to the synergistic effect of orthogonal projection and PG in refining the model’s ability to navigate the complex landscape of ZSIR. The orthogonal projection’s role in structuring the feature space, coupled with PG’s enhancement of prototype diversity and inter-class connectivity, culminates in a robust framework that adeptly aligns AI’s cognitive processes with human-like understanding. These findings not only validate the proposed components’ effectiveness but also pave the way for future explorations into optimising ZSIR frameworks for improved cognitive alignment and retrieval performance.

4.4. Cognition Alignment Analysis

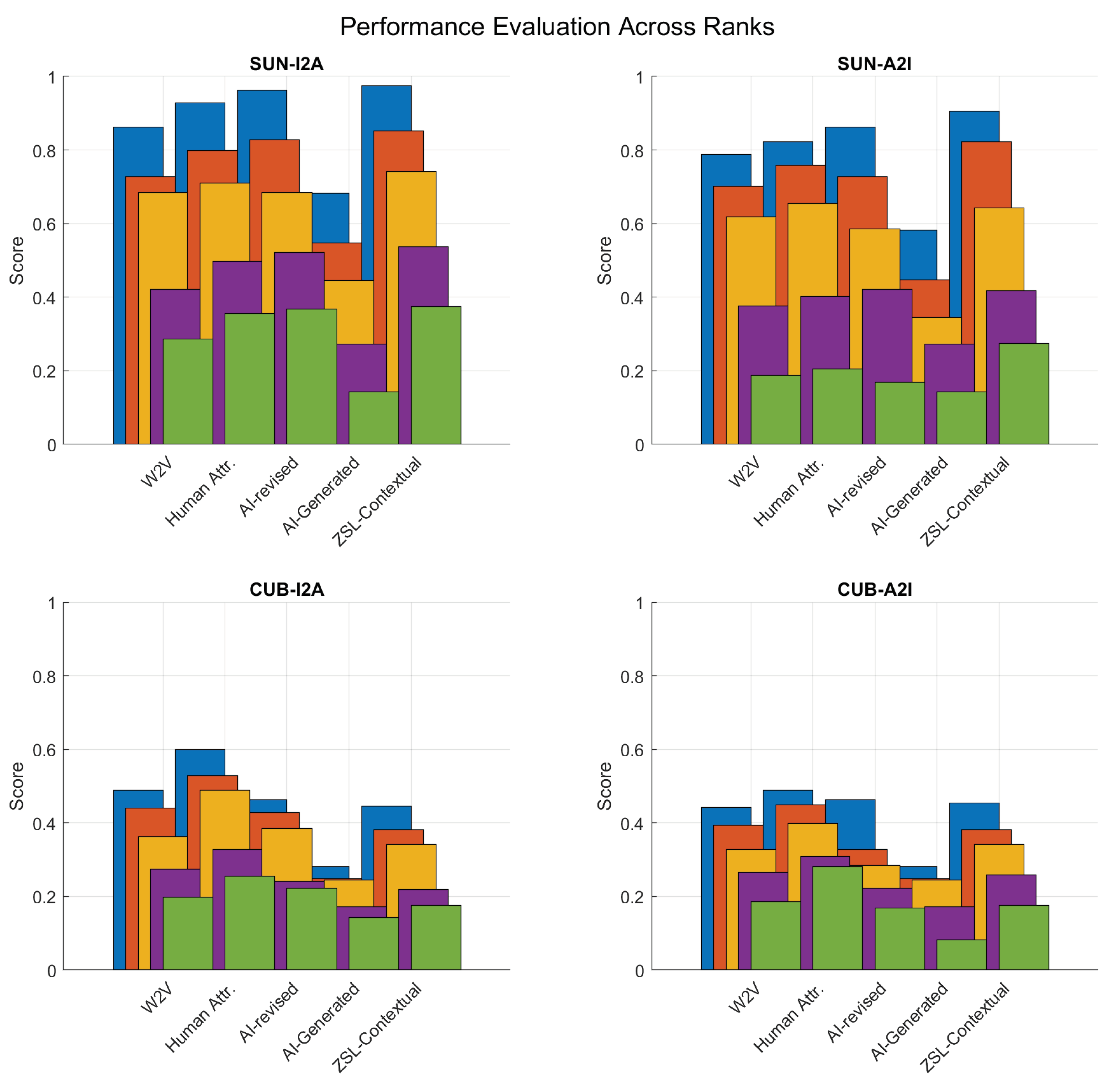

The discussion of the results from the

Figure 5 on ZSIR across the SUN and CUB datasets provides insightful observations into the performance of various AI approaches in comparison to human attributes. This analysis is pivotal for understanding the cognitive alignment between AI-generated attributes and human perception in the context of ZSIR tasks.

4.5. Observations and Discussion

W2V Word Embedding: The Word2Vec (W2V) embeddings exhibit a stable performance across both tasks (image to attributes and attribute to image), slightly trailing behind the results achieved using human attributes. This consistency underscores the robustness of W2V embeddings in capturing semantic relationships, albeit with a marginal gap in cognitive alignment compared to human-derived attributes.

AI-Revised Attributes Performance: The AI-revised attributes, while maintaining the conceptual framework of attributes defined by human experts, show an interesting dichotomy in performance. On the SUN dataset, these revised attributes outperform both W2V embeddings and human attributes, suggesting a closer alignment with AI’s visual-semantic understanding for this dataset. Conversely, on the CUB dataset, their performance dips below both W2V and human attributes. This variation highlights the context-dependent effectiveness of AI revisions, particularly struggling in the fine-grained classification required by the CUB dataset.

AI-Generated Attributes Limitations: The approach of generating attributes and their values entirely through AI results in the lowest performance across all tasks and datasets. This outcome points to a significant misalignment in the AI’s generation process with the specific demands of visual-semantic learning and zero-shot generalisation. The lack of proper scoping using prompt engineering in attribute generation and value assignment critically hampers the effectiveness of this method.

ZSL-Contextualised Attributes Success: When LLM of ChatGPT is informed about the ZSL and image retrieval tasks, the resulting ZSL-contextualised attributes significantly improve performance, particularly on the SUN dataset. This improvement indicates a higher degree of cognitive alignment, as the attributes and their values are more precisely tailored to the tasks at hand.

Challenges with Fine-Grained Classification: Despite the advancements in AI approaches, human attributes remain the superior cognitive representation for the CUB dataset, which demands extensive expert knowledge for fine-grained bird classification. The ZSL-contextual model and W2V embedding exhibit similar performances in this domain, underscoring the challenge AI faces in matching human expertise in highly specialised tasks.

The comparative analysis of AI approaches against human attributes in ZSIR tasks reveals critical insights into the cognitive alignment of AI with human perception. While AI-revised and AI-generated attributes show potential under certain conditions, they also highlight the limitations of current AI methodologies in fully grasping the nuances of visual-semantic relationships, especially in specialised domains like fine-grained classification. The success of ZSL-contextualised attributes on the SUN dataset opens promising avenues for enhancing cognitive alignment through task-aware attribute generation.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we have introduced a groundbreaking framework that leverages ZSIR to delve into the cognitive alignment of large visual language models with human cognitive processes. Our approach, focused around a novel unified similarity function, marks a significant stride in understanding how AI systems interpret and process visual information in scenarios involving previously unseen data. The rigorous evaluation of our framework across the CUB and SUN datasets has not only validated the effectiveness of our similarity function but also highlighted its adaptability across various knowledge representations, including visual attributes and textual descriptions generated by AI models. Our findings underscore the potential of our method to serve as a benchmark for cognitive alignment in AI, demonstrating superior performance in ZSIR tasks compared to existing state-of-the-art approaches. This research contributes to the broader goal of developing AI technologies that can seamlessly integrate into human-centric applications, ensuring that AI systems can interpret and respond to the world in ways that mirror human thought and understanding.

Several avenues for future research emerge from our findings. First, exploring the application of our unified similarity function across a wider array of datasets and in more diverse scenarios could further validate its robustness and versatility. Additionally, integrating our approach with other forms of knowledge representation, such as video or audio data, could offer deeper insights into the cognitive alignment of AI across different sensory modalities. Another promising direction involves refining the similarity function to accommodate dynamic learning environments, where AI systems continuously adapt to new information in a manner akin to human learning. Finally, investigating the ethical implications of cognition-aligned AI systems and their impact on society will be crucial as these technologies become increasingly prevalent in everyday life. Through these future endeavours, we aim to advance the field of AI towards more intuitive, human-like understanding and interaction with the world, fostering the development of ethical and cognitively aligned AI systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Teng Ma and Wenbao Ma; Methodology, Teng Ma and Yang Long; software, Teng Ma and Yang Long; Formal Analysis, Daniel Organisciak, Teng Ma and Yang Long; writing—original draft preparation, Teng Ma; writing—review and editing, Daniel Organisciak, Teng Ma and Yang Long; Visualisation, Teng Ma; supervision, Wenbao Ma. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligencce |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| ZSL |

Zero-Shot Learning |

| ZSIR |

Zero-Shot Instance Retrieval |

| LIAD |

Latent Instance Attributes Discovery |

| PG |

Prototype Grouping |

| CA |

Cognition Alignment |

References

- Long, Y.; Liu, L.; Shen, Y.; Shao, L. Towards affordable semantic searching: Zero-shot retrieval via dominant attributes. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2018, Vol. 32. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; others. Taming Simulators: Challenges, Pathways and Vision for the Alignment of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.01317 2023.

- Wang, X.; others. Emotional Intelligence of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09042 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lester, B.; others. CogAlign: Learning to Align Textual Neural Representations to Cognitive Language Processing Signals. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.06354 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; others. CValues: Measuring the Values of Chinese Large Language Models from Safety to Responsibility. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09705 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, N.; others. Jais and Jais-chat: Arabic-Centric Foundation and Instruction-Tuned Open Generative Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.16149 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; others. BayLing: Bridging Cross-lingual Alignment and Instruction Following through Interactive Translation for Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.10968 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; others. Making Large Language Models Better Reasoners with Alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.02144 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; others. Red-Teaming Large Language Models using Chain of Utterances for Safety-Alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.09662 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; others. Large Language Model Alignment: A Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.05374 2023.

- Petroni, F.; others. Language Models as Knowledge Bases? arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.01066 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; others. Interleaving Pre-Trained Language Models and Large Language Models for Zero-Shot NL2SQL Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.08891 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, H.R.; others. Personalisation within Bounds: A Risk Taxonomy and Policy Framework for the Alignment of Large Language Models with Personalised Feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.05453 2023. [CrossRef]

- Larochelle, H.; others. Zero-data learning of new tasks. AAAI, 2009.

- Palatucci, M.; others. Zero-shot learning with semantic output codes. Neural Information Processing Systems 2009.

- Lampert, C.H.; others. Learning to detect unseen object classes by between-class attribute transfer. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Frome, A.; others. DeViSE: A deep visual-semantic embedding model. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2013.

- Norouzi, M.; others. Zero-shot learning by convex combination of semantic embeddings. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2014.

- Changpinyo, S.; others. Synthesized classifiers for zero-shot learning. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; others. Zero-shot learning - A comprehensive evaluation of the good, the bad and the ugly. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2017. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; others. Generalized zero-shot learning with deep calibration network. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018.

- Wang, W.; others. A survey on zero-shot learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2019.

- Khandelwal, S.; others. Frustratingly Simple but Effective Zero-shot Detection and Segmentation: Analysis and a Strong Baseline. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.07319 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; others. Automatic vision-based calculation of excavator earthmoving productivity using zero-shot learning activity recognition. Automation in Construction 2023, 104, 104702. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.; others. CSI-Based Cross-Domain Activity Recognition via Zero-Shot Prototypical Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.07076 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; others. Semantics Guided Contrastive Learning of Transformers for Zero-shot Temporal Activity Detection. IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2023.

- Zhang, Z.; Saligrama, V. Zero-shot learning via semantic similarity embedding. International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2015.

- Lampert, C.H.; Nickisch, H.; Harmeling, S. Learning to detect unseen object classes by between-class attribute transfer. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2009. [CrossRef]

- Akata, Z.; Perronnin, F.; Harchaoui, Z.; Schmid, C. Label-embedding for attribute-based classification. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2013. [CrossRef]

- Romera-Paredes, B.; Torr, P.H.S. An embarrassingly simple approach to zero-shot learning. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2015.

- Xian, Y.; Akata, Z.; Sharma, G.; Nguyen, Q.; Hein, M.; Schiele, B. Latent embeddings for zero-shot classification. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).