Submitted:

11 March 2024

Posted:

13 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the specific challenges faced by women in navigating and accessing urban spaces?

- How can feminist architecture contribute to creating more inclusive and empowering spaces?

- What are the potential benefits of integrating feminist architecture principles into urban design practices?

- What are the barriers to implementing feminist architecture in mainstream design practices and how can they be overcome?

2. Material and Methods

3. Literature Review

3.1. Background

3.2. Challenges Faced by Women in Accessing Urban Spaces

- One of the key challenges faced by women is safety. Women are more likely than men to experience harassment, assault, and violence in public spaces (Sharma et al., 2016). Fear of violence can lead women to avoid certain areas or times of day, restricting their mobility and access to public amenities (Pike, Dawes, & Christie, 2010). Additionally, the lack of adequate lighting, security measures, and surveillance in public spaces can exacerbate safety concerns for women (Ghasemi, 2015).

- Another challenge faced by women is the lack of access to public transportation. Women are more likely than men to rely on public transportation for their daily mobility needs (Ghose, 2017). However, women also experience specific challenges related to transportation, such as harassment on public transportation, limited transportation options in low-income areas, and inadequate transportation infrastructure in rural areas (Newman, 2012).

- Furthermore, the built environment can have a significant impact on women's caregiving responsibilities. Women are more likely than men to be responsible for child and elder care, which can impact their mobility and ability to access public spaces (Zhang, 2017). The lack of accessible and affordable childcare options can also create barriers for women's participation in public life (Schroeder, 2015).

3.3. Benefits of Feminist Architecture in Urban Design

3.4. Case Reviews

3.4.1. The City of Vienna, Austria

3.4.2. The City of Montreal, Canada

3.4.3. Kigali, Rwanda

3.4.4. Shan-Shui City in China

3.4.5. The Super-Space Project in Oslo, Norway

3.4.6. Building Homes, Building Hope

4. Discussion

4.1. Concluding Empirical Data

| Principles | Practical solutions | Potential results |

|---|---|---|

|

Gender-sensitive budgeting: Equal distribution of resources Improving access to services Engagement and collaboration: Local community-led solutions and Engagement of civil society Women's advocacy groups Participate in decision-making processes: Meet their specific needs long-term and interdisciplinary approach |

Gender-sensitive public transportation system: women-only subway |

Reduce harassment Increase the feeling of safety Transparency and Accountability |

| Affordable Housing for single mothers with low incomes: women-only housing | Equitable urban living and Livability |

|

| Improving Public Spaces: Seating areas Investing on Street Lighting Construction of public toilets |

Inclusive for all: Comfortable for people of all sizes and abilities Safety, Welcoming Accessibility |

|

| Integration of Green space and Public Infrastructure |

Harmonious coexistence between human communities and natural environments | |

| Digital platform: Allows community members to share their experiences and perspectives on public space |

Diverse perspectives and cultural values: |

4.2. Feminist Design Practices

4.2.1. Approach That Prioritizes Inclusivity and Accessibility

4.2.2. Emphasizing Embodiment

4.2.3. Promotion of Gender-Inclusive Research Methods

4.2.4. Creation of Feminist Design Practices

4.2.5. Creation of Public Spaces That Are Safe and Accessible for Marginalized Individuals

4.3. Barriers for Mainstream Implementation of Feminist Architecture

- One of the most significant barriers to the integration of feminist architecture principles into mainstream design practices is the deeply entrenched patriarchal power structures that underpin the design professions. These structures tend to prioritize the perspectives, experiences and needs of white, male, cisgender individuals over those of marginalized individuals. The architecture profession has historically been dominated by men, which may marginalize the perspectives and experiences of women and gender-nonconforming individuals within the field (Blanchonette and Vanova, 2018).

- Besides that, the dominance of norms and traditions within the architecture profession and broader society is another key barrier to feminist architecture strategies (Blanchonette and Vanova, 2018). These norms can shape the design process and limit opportunities for feminist architects to challenge gendered assumptions and approaches. For instance, some have noted that the design profession is often driven by a "starchitect" model that prioritizes individual genius and competition rather than collaboration and community engagement (Ginwala, 2019). Similarly,

- One more challenge to feminist architecture strategies is the cost and availability of resources needed to incorporate a feminist approach to design. This includes not only financial resources, but also access to data, technology and other specialized tools used to design and implement spaces. If design services are costly and hard to obtain, it may be less inclined to make priority for feminist design principles and accessibility is further reduced for marginalized groups (Shadman et al., 2020). Consequently, it is important that access disparities are addressed and resources shared so that designers from all backgrounds are able to incorporate feminist design principles into their work.

- In addition, further challenge is the lack of political support for feminist architecture strategies, particularly in areas where legislators may be resistant towards social equity and inclusive design practices (Ginwala, 2019). There may be resistance from policymakers due to factors such as budget constraints, economic pressures, or political ideologies that prioritize other concerns over social equality.

- Lack of diversity within design education and practice is the other obstacle that needs to be addressed in order to promote the integration of feminist design principles. Design programs tend to lack diversity, which results in a homogenization of ideas, approaches, and solutions. In response, a key strategy is to promote an interdisciplinary and intersectional approach to design education and practice (Ginwala, 2019).

- Besides all, resistance to change is also a significant barrier to the integration of feminist architecture principles into mainstream design practices. Those in power often resist change as it implies a relinquishing of power.

| Obstacles | Factors | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Norms and Traditions | Patriarchal power structures (Historically been dominated by men) Starchitect |

Prioritizes individual genius and competition Racism |

| Cost and Availability of Resources | Financial resources Access to: Data, Technology and other specialized tools |

less inclined to make priority for feminist design principles |

| Lack of Political support | Budget constraints Economic pressures Political ideologies. |

Resistance from policymakers |

| Lack of Diversity within design education and practice | Gender Race Class Ability |

Homogenization of ideas, approaches, and solutions |

| Resistance to change | Among feminist advocates | Lack of shared language |

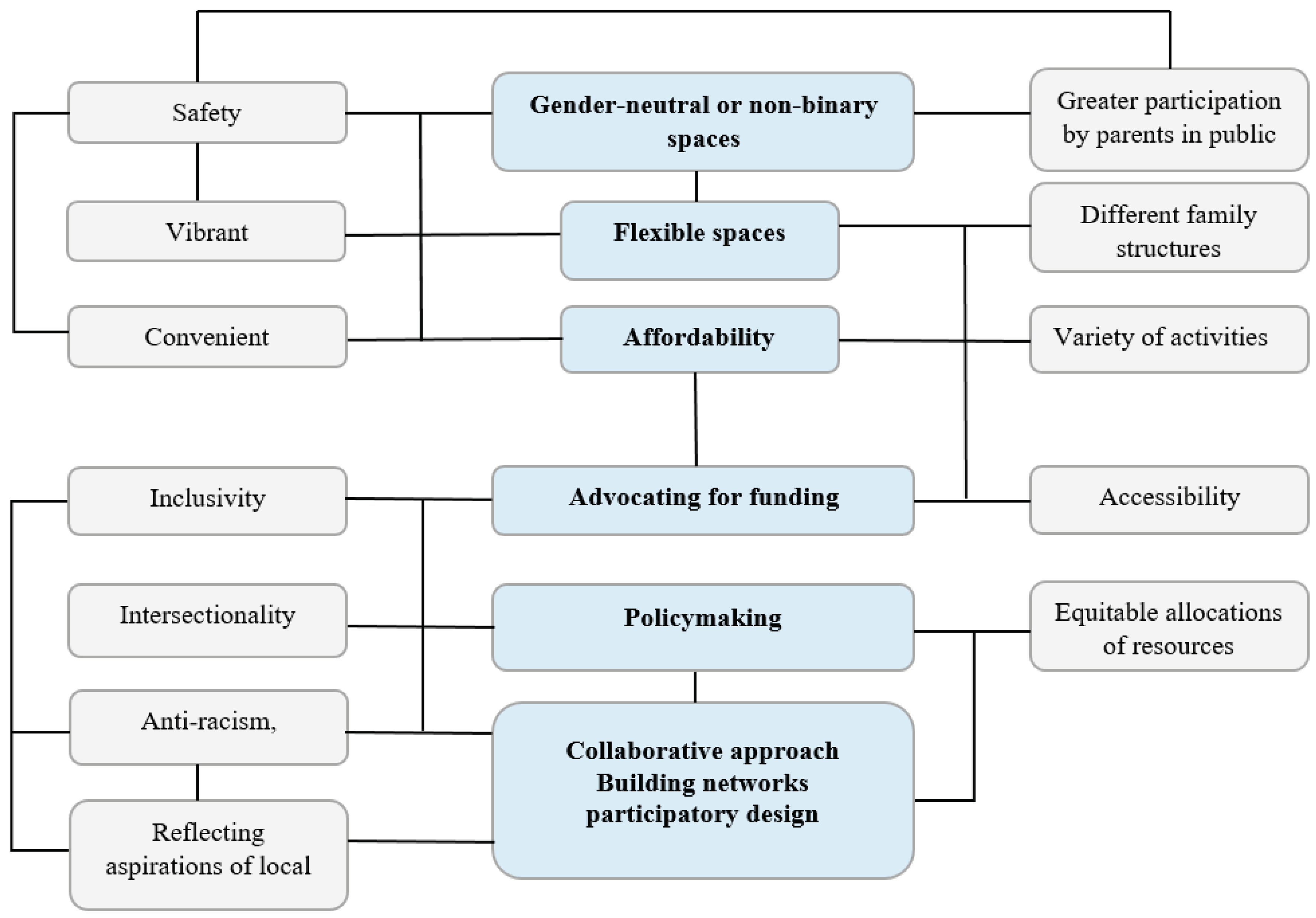

5. Result and Outcomes

Proposed Remedies for Obstacles

6. Conclusion

References

- Gill, E. (2014). An Introduction to Feminist Architecture. Architectural Design, 84(6), 104-109.

- Kerns, M. E. (2017). Feminist Practices in Architecture and Planning. In T. Olwig & J. S. Mitchell (Eds.), Feminist Approaches to the Study of Landscapes (pp. 197-207). Routledge.

- Desai, C. (2018). Architecture and the Paradox of Feminine Space. Journal of Architectural Education, 72(2), 221-230.

- Gharaei, N. (2018). From Women's Issues to Feminist Architecture: An Investigation of Feminist Architecture as a Practice. Oñati Socio-Legal Series, 8(4), 756-769.

- Bailey, N. (2019). Feminism and architecture. The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Architecture. [CrossRef]

- Orr, J. (2017). Feminist architecture? Built Environment, 43(2), 157-169.

- Shivers-Blackwell, S., & Smith, E. C. (2018). Feminist Inquiry and Architecture: From Disciplinarity to Intersectionality. Routledge.

- Gin, D. (2019). Feminist urban design: An idea whose time has come. Planning Theory, 18(2), 188-207.

- Yen, L. S., & Patel, S. (2016). Feminist Practices in Education and Practice: A Case Study of the Architecture and Urban Planning Program at Princeton. In Handbook of Research on Gender and Teaching (pp. 595-611). IGI Global.

- Westerhof, L., & de la Pena, E. R. (2018). Feminist urbanism through intersectional urban design. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(4), 599-622.

- Sharma, R., Kishore, A., & Singh, R. (2016). Women Safety and Accessibility in Indian Urban Cities. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 219, 131-138.

- Pike, L., Dawes, L., & Christie, N. (2010). Crime, Fear of Crime and Mental Health: Synthesised Review of Theories and Psychological Approaches. London: UCL Jill Dando Institute of Security and Crime Science.

- Ghasemi, M. R. (2015). City safety and crime prevention via urban design; a review of the theory and practice. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 201, 182-189.

- Ghose, R. (2017). Unequal access: Women's and men's experiences of travel in an Indian city. Transport Policy, 60, 10-19.

- Newman, P. (2012). Crime and vandalism in public transport: international experiences and solutions. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Zhang, L. (2017). Balancing mobility and care: Gendered challenges for low-income women and families in Shanghai. Journal of Transport Geography, 65, 16-23.

- Schroeder, T. (2015). The city as a platform for feminist practices: toward an intersectional approach to care and urban gardening movements. In Gender, Ethnicity and Place (pp. 19-36). Routledge.

- Ginwala, N. (2019). Gender, space and architecture: Introducing feminisms into the design of built environments. Routledge.

- Aragon, L. M., Stoddart, M. C., & Bricker, J. D. (2018). In the name of sustainability: Exploring the links between feminist architecture and sustainability. Journal of Architectural Education, 72(2), 183-194.

- Korzep, K., & Schrader, U. (2017). Participatory design in architecture—Challenges and opportunities for gender-sensitive research and practice. Architecture and Culture, 5(1), 127-143.

- European Institute for Gender Equality. (2016). Gender Equality Index 2015: Measuring Gender Equality in the European Union 2005-2012. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Institute for Gender Equality. (2016). Gender Equality in Austria. Retrieved from https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2015/country/austria.

- Jeffers, E. (2020). Participatory Budgeting and Gender Equity: Evidence from Montreal. Journal of Urban Affairs, 42(3), 346-361.

- Sintomer, Y., Herzberg, C., & Allegretti, G. (2012). Participatory budgeting in Europe: Democracy and public governance. Routledge.

- Vives-Miró, S., & Ferrer, G. (2016). Gender-sensitive budgeting in Rwanda's capital city: promoting equity and inclusion through urban governance. Gender & Development, 24(1), 29-42.

- Wang, Y. (2016). Shan-shui city: A visionary model for China's urbanization. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/1d3e2d9e-f7da-11e5-96db-fc683b5e52db.

- Hao, K. (2019). Ma Yansong's Shan-shui city masterplan is an eco-friendly oasis. ArchDaily. Retrieved from https://www.archdaily.com/916603/ma-yansongs-shan-shui-city-masterplan-is-an-eco-friendly-oasis.

- Ferrell, J. (2019). Super-space: A feminist approach to urban planning in Oslo. Journal of Urban Design, 24(3), 278-293. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J., & Johnson, E. (2020). Building Homes, Building Hope: Collaborative Housing Design for Women and Girls in Latin America. Journal of Feminist Architecture, 4(1), 23-38.

- Blanchonette, I., & Vanova, L. (2018). Feminist spatial practices in architecture: From design activism to affective practices. Gender, Place & Culture, 25(2), 272-290.

- Shadman, F., Ramaswamy, K., & Fumei, A. W. (2020). Advancing feminist architecture through a South-to-South exchange: Views from the field. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(2), 138-157.

- Stratigakos, D. (2016). The challenges of feminist architecture. Places Journal. Retrieved from https://placesjournal.org/article/the-challenges-of-feminist-architecture/.

- Mies, M., & Okoba, B. (2019). Urban planning for gender equality in cities: A review of the literature. Cities & Health, 3(1), 9-22.

- Crenshaw, K., & Pellow, K. (2017). Restrooms and Respect for Gender Diversity. Planning, 83(1), 9-13.

- Achterberg, E. (2019). Incorporating feminist principles into design practice: overcoming financial constraints. Gender, Place & Culture, 26(1), 32-49.

- Evans, J., & Neumann, D. (2019). The politics of feminist knowledge co-production in urban design education. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), 84-9.

- Klein, M. (2018). Collaborative feminist pedagogy: teaching for a feminist built environment. In The Routledge Handbook of Planning Theory (pp. 254-266). Routledge.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).