Submitted:

12 March 2024

Posted:

12 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Review Questions

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

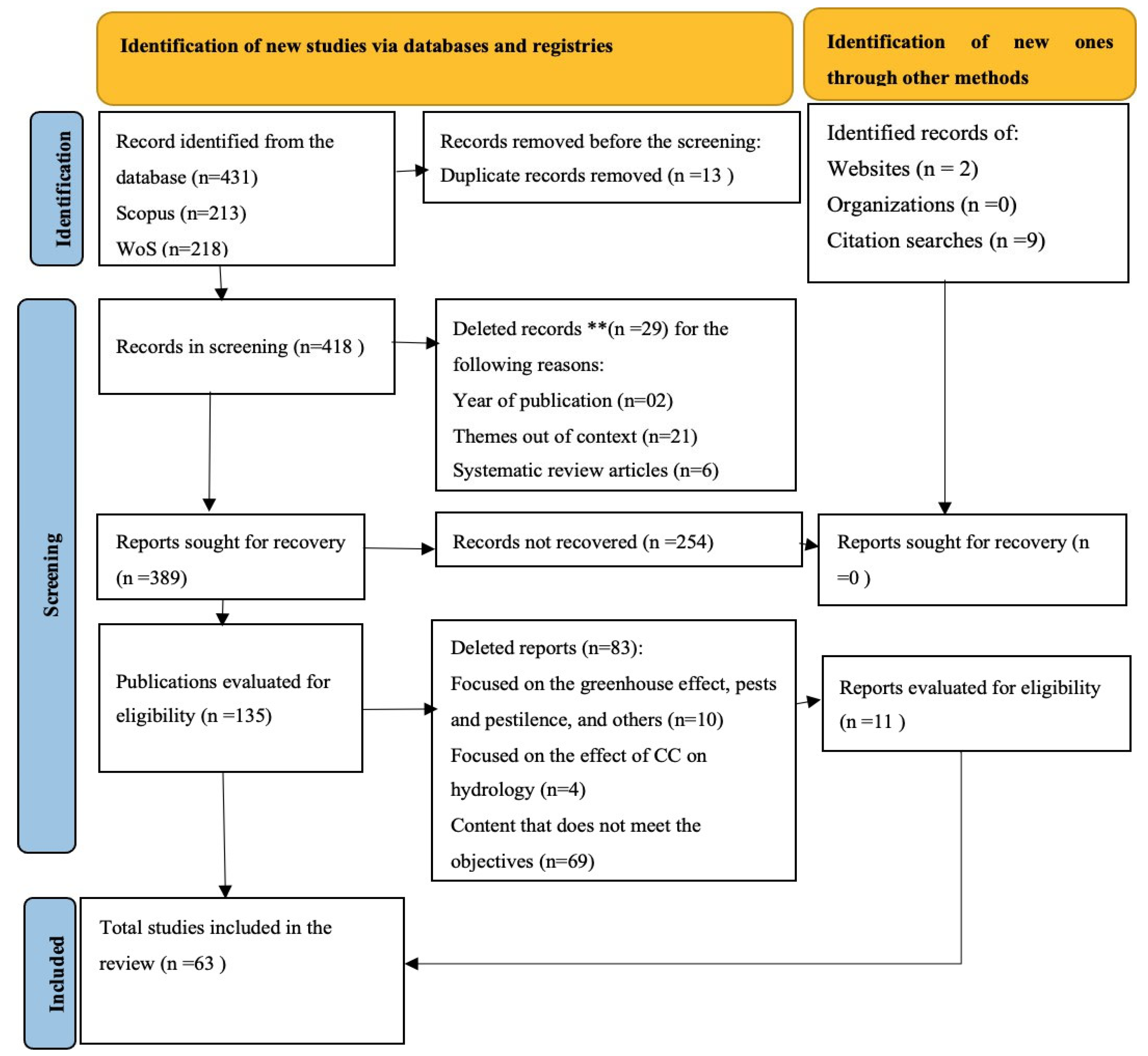

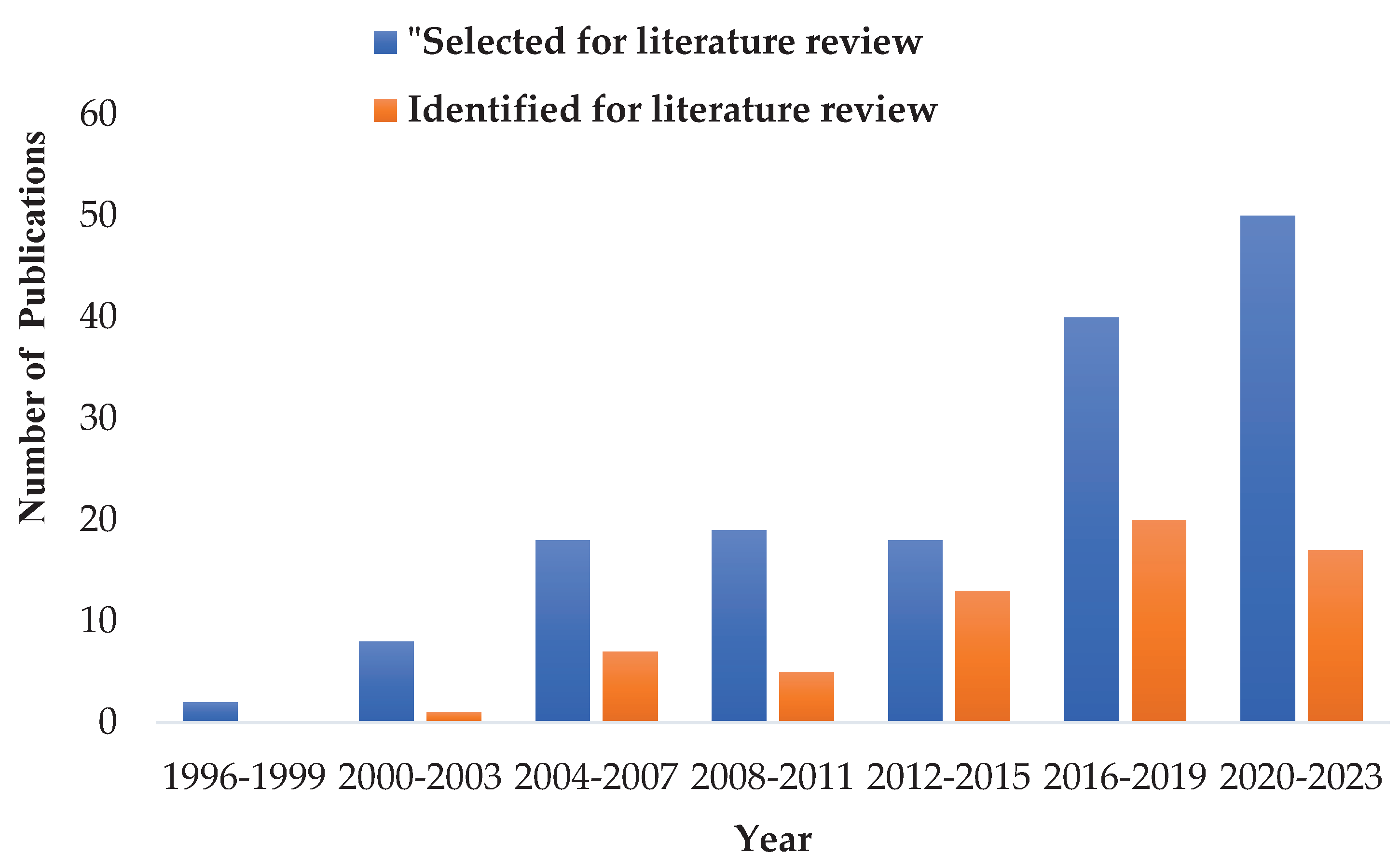

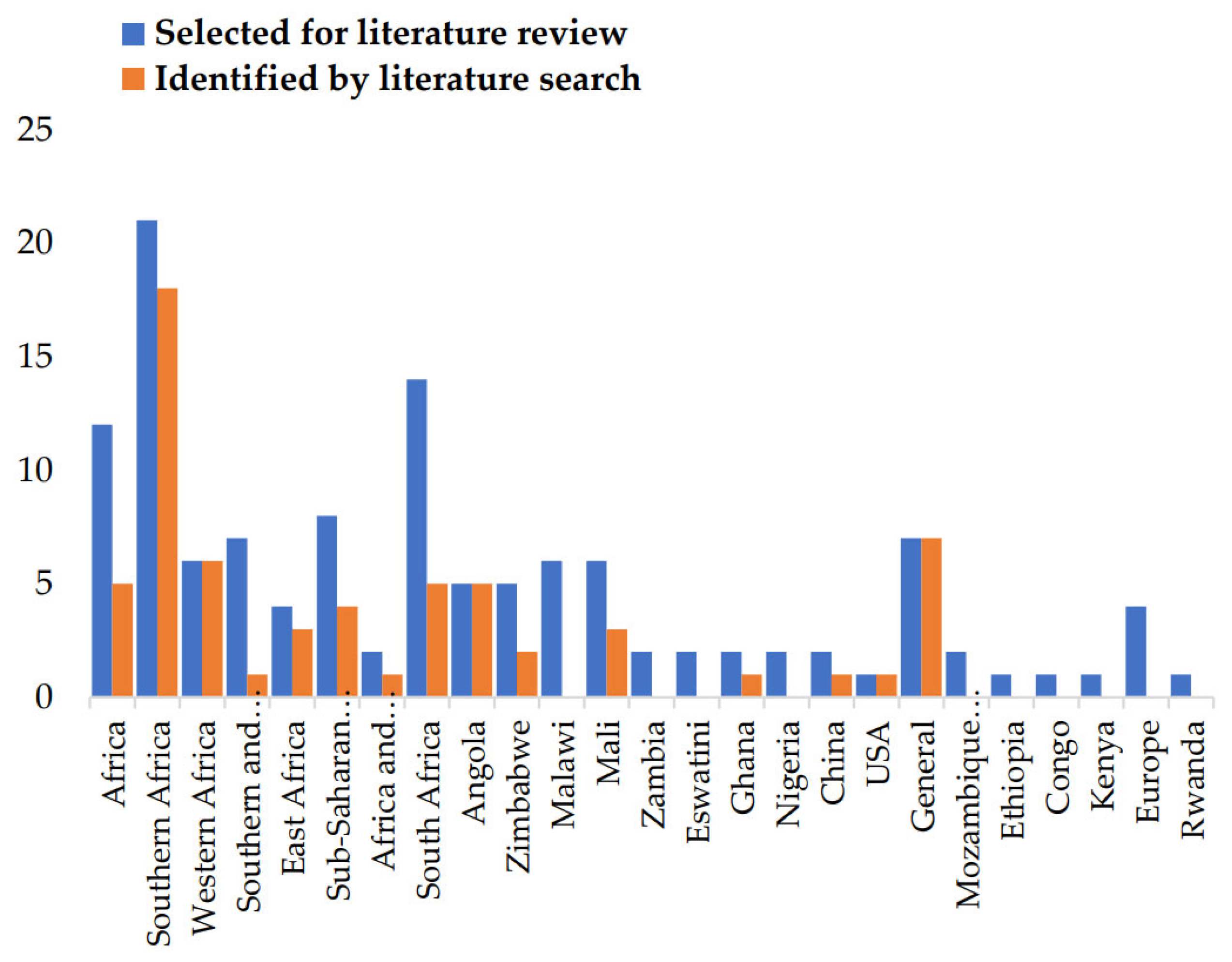

3.1. Publications Identified with the PRISMA2020 Methodology

3.2. Literature Review

3.2.1. Climate Change in Agriculture

3.2.2. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

- (v)

3.2.3. Impact of Agroclimatic and Bioclimatic Indicators on Crop Yields

| Year | Starting Monthsand End of the Drought | Duration(Months) | Dry ThroughoutYear/SeasonRainy/Dry | Max SPI Rating SPI Overlay (max=4) | ENSO (Year) Strength TS anomaly (NOAA,2021,2022) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981-82, | Oct-19 8 1-J an- 19 82 | 4 | Wet | Serious,3 | Neutral (1980-1982) |

| 1989-90, | Oct-1989-May-1990 | 8 | Wet | Extreme,3 | Neutral (1989–1990) |

| 1994 | Mar-199 4 -Oct-1994 | 8 | Wet+Dry | Extreme,3 | El Niño (1994–1995), moderate |

| 1995-97 | April-1995-September-1997 | 33 | Many years | Extreme,4 | La Niña (1995–1996), moderate. Neutral (1996–1997). El Niño (1997–1998), very strong |

| 1999–01 | Nov-1999-Oct-2001 | 24 | Many years | Extreme,4 | La Niña (1999–2000), strong. La Nina (2000–2001), weak |

| 2014–16 | Nov-1999-Oct-2001 | 17 | All year round | Extreme,4 | El Niño (2014–2015), weak. El Niño (2015–2016), very strong |

| 2017–18 | Jan-2017-Feb-2018 | 14 | All year round | Extreme,4 | Niño (2014–2015), weak. El Niño, very strong La Niña (2017–2018), weak |

| 2018–20 | Oct-2018-Feb-2020 | 17 | All year round | Extreme,4 | El Niño (2018–2019), weak. Neutral (2019–2020) |

3.2.4. Relationship of Agroclimatic and Bioclimatic Indicators with CROps

3.3. Food Safety

4. Climate Change Projections in Angola

5. Study Limitations and Final Considerations

6. Conclusions

References

- IPCC. Mudanças Climáticas 2007 Relatório de síntese; Intergovernamental Painel ativado das Alterações Climáticas: Genebra, 2007; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bandara, J.S.; Cai, Y. The impact of climate change on food crop productivity, food prices and food security in South Asia. Economic Analysis and Policy 2014, 44, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Dold, C. Climate Change Impacts on Corn Phenology and Productivity. Corn - Production and Human Health in Changing Climate. [CrossRef]

- Gornall, J.; Betts, R.; Burke, E.; Clark, R.; Camp, J.; Willett, K.; Wiltshire, A. Implications of climate change for agricultural productivity in the early twenty-first century. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2010, 365, 2973–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpandeli, S.; Nhamo, L.; Moeletsi, M.; Masupha, T.; Magidi, J.; Tshikolomo, K.; Liphadzi, S.; Naidoo, D.; Mabhaudhi, T. Assessing climate change and adaptive capacity at local scale using observed and remotely sensed data. Weather and Climate Extremes 2019, 26, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, P.; Geza, W.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Sutherland, C.; Queenan, K.; Dangour, A.; Scheelbeek, P. Dietary and agricultural adaptations to drought among smallholder farmers in South Africa: A qualitative study. Weather and Climate Extremes 2022, 35, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H, Y. A Review on Relationship between Climate Change and Agriculture. Journal of Earth Science & Climatic Change 2015, 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirisa, I.; Gumbo, T.; Gundu-Jakarasi, V.N.; Zhakata, W.; Karakadzai, T.; Dipura, R.; Moyo, T. Interrogating climate adaptation financing in zimbabwe: Proposed direction. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L. Adapting agriculture to climate change via sustainable irrigation: Biophysical potentials and feedbacks. Environmental Research Letters 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuor, G.; Amponsah, W.; Oteng-Darko, P.; Osei, G. Safeguarding food security through large-scale adoption of agricultural production technologies: The case of greenhouse farming in Ghana. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2022, 6, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, G.P.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Gyampoh, B.A. The effect of climate variability on maize production in the ejura-sekyedumase municipality, ghana. Climate 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhemachena, C.; Nhamo, L.; Matchaya, G.; Nhemachena, C.R.; Muchara, B.; Karuaihe, S.T.; Mpandeli, S. Climate change impacts on water and agriculture sectors in southern africa: Threats and opportunities for sustainable development. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choruma, D.J.; Akamagwuna, F.C.; Odume, N.O. Simulating the Impacts of Climate Change on Maize Yields Using EPIC: A Case Study in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, O.; Blamey, R.C.; Reason, C.J. Drought metrics and temperature extremes over the Okavango River basin, southern Africa,and links with the Botswana high. International Journal of Climatology 2023, 43, 6463–6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic´, G.; Ivanovic´, T.; Kneževic´, D.; Radosavac, A.; Obhod¯aš, I.; Brzakovic´, T.; Golic´, Z.; Dragicˇevic´ Radicˇevic´, T. Assessment of Climate Change Impact on Maize Production in Serbia. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eka Suranny, L.; Gravitiani, E.; Rahardjo, M. Impact of climate change on the agriculture sector and its adaptation strategies. IOPConference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemi, T. Effects of Climate Change Variability on Agricultural Productivity. International Journal of Environmental Sciences & Natural Resources 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloumi, M. Investigating the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Production in Eastern and Southern African Countries. AGRODEP working paper 0003 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, A.; Abukari, A.B.T.; Abdul-Malik, A. Testing the climate resilience of sorghum and millet with time series data. Cogent Food and Agriculture 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, M.; Awala, S.K.; Watanabe, Y.; Kawato, Y.; Fujioka, Y.; Yamane, K.; Wada, K.C. Mixed cropping has the potential to enhance flood tolerance of drought-adapted grain crops. Journal of Plant Physiology 2016, 192, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M. Economic impacts of climate change on agriculture: The importance of additional climatic variables other than temperature and precipitation. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2017, 83, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzadilla, A.; Zhu, T.; Rehdanz, K.; Tol, R.S.; Ringler, C. Climate change and agriculture: Impacts and adaptation options in South Africa. Water Resources and Economics 2014, 5, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudi. ; Pramudia, A.; Salman, D.; Agustian, A.; Zulkifli.; Permanasari, M.N. Gestão da plantação de culturas na estação seca de 2020, uma adaptação ao impacto da seca para apoiar a segurança alimentar. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouziyne, Y.; Abouabdillah, A.; Chehbouni, A.; Hanich, L.; Bergaoui, K.; McDonnell, R.; Benaabidate, L. Assessing hydrological vulnerability to future droughts in a Mediterranean watershed: Combined indices-based and distributed modeling approaches. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A. Coping with drought: Narratives from smallholder farmers in semi-arid Kenya. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2021, 57, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.C.; Santos, F.D.; Pulquério, M. Climate change scenarios for Angola: an analysis of precipitation and temperature projections using four RCMs. International Journal of Climatology 2017, 37, 3398–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, I.; de Perez, E.C.; Jaime, C.; Wolski, P.; van Aardenne, L.; Jjemba, E.; Suidman, J.; Serrat-Capdevila, A.; Tall, A. Climate change projections from a multi-model ensemble of CORDEX and CMIPs over Angola. Environmental Research: Climate 2023, 2, 035007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, M.; Woodborne, S.; Fitchett, J.M. Drought history and vegetation response in the Angolan Highlands. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2023, 151, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, T.W.B. Angola country climate and development report 2022.

- Usman, M.T.; Archer, E.; Johnston, P.; Tadross, M. A conceptual framework for enhancing the utility of rainfall hazard forecasts for agriculture in marginal environments. Natural Hazards 2005, 34, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutengwa, C.S.; Mnkeni, P.; Kondwakwenda, A. Climate-Smart Agriculture and Food Security in Southern Africa: A Review of the Vulnerability of Smallholder Agriculture and Food Security to Climate Change. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Nigam, S. Twentieth-century climate change over Africa: Seasonal hydroclimate trends and sahara desert expansion. Journal of Climate 2018, 31, 3349–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challinor, A.; Wheeler, T.; Garforth, C.; Craufurd, P.; Kassam, A. Assessing the vulnerability of food crop systems in Africa to climate change. Climatic Change 2007, 83, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, M.E. Global change and southern Africa. Geographical Research 2006, 44, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asafu-Adjaye, J. The economic impacts of climate change on agriculture in Africa. Journal of African Economies 2014, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.M.; O’Brien, K.L. The Dynamics of Rural Vulnerability to Global Change: The Case of southern Africa. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2002, p.1-18. [CrossRef]

- Tirivangasi, H.M. Regional disaster risk management strategies for food security: Probing Southern African Development Community channels for influencing national policy. Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 2018, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, J.P.; Reckziegel, R.B.; Borrass, L.; Chirwa, P.W.; Cuaranhua, C.J.; Hassler, S.K.; Hoffmeister, S.; Kestel, F.; Maier, R.; Mälicke, M.; et al. Agroforestry: An appropriate and sustainable response to a changing climate in Southern Africa? Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.M.; Barros, A.P. Prospects for long-term agriculture in southern africa: Emergent dynamics of savannah ecosystems from remote sensing observations. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbebiyi, T.S.; Lennard, C.; Crespo, O.; Mukwenha, P.; Lawal, S.; Quagraine, K. Assessing future spatio-temporal changes in crop suitability and planting season over West Africa: Using the concept of crop-climate departure. Climate 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manatsa, D.; Unganai, L.; Gadzirai, C.; Behera, S.K. An innovative tailored seasonal rainfall forecasting production in Zimbabwe. Natural Hazards 2012, 64, 1187–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Lai, C.; Wang, R.Y.; Chen, X.; Lian, Y. Drying tendency dominating the global grain production area. Global Food Security 2018, 16, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, M.; Noce, S.; Antonelli, M.; Caporaso, L. Complex drought patterns robustly explain global yield loss for major crops. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooni, I.K.; Hagan, D.F.T.; Ullah, W.; Lu, J.; Li, S.; Prempeh, N.A.; Gnitou, G.T.; Sian, K.T.C.L.K. Projections of Drought Characteristics Based on the CNRM-CM6 Model over Africa. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2022, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahut, D.B.; Aryal, J.P.; Marenya, P. Understanding climate-risk coping strategies among farm households: Evidence from five countries in Eastern and Southern Africa. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 769, 145236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofisi, C.; Chigavazira, B.; Mago, S.; Hofisi, M. "Climate finance issues": Implications for climate change adaptation for food security in Southern Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 2013, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makate, C.; Makate, M.; Mango, N. Smallholder farmers’ perceptions on climate change and the use of sustainable agricultural practices in the chinyanja triangle, Southern Africa. Social Sciences 2017, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leakey, R.R.; Tientcheu Avana, M.L.; Awazi, N.P.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Hendre, P.S.; Degrande, A.; Hlahla, S.; Manda, L. The Future of Food: Domestication and Commercialization of Indigenous Food Crops in Africa over the Third Decade (2012–2021). Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhamo, L.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Modi, A.T. Preparedness or repeated short-term relief aid? Building drought resilience through early warning in southern africa. Water SA 2019, 45, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhin, J.K. South African crop farming and climate change: An economic assessment of impacts. Global Environmental Change 2008, 18, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, B.J.; Russo, V. Biodiversity of Angola; 2019. [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Mannke, F. Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change by Developing Promising Strategies Using Analogue Locations in Eastern and Southern Africa: Introducing the Calesa Project. In Experiences of Climate Change Adaptation in Africa; 2011; pp. 247–253. [CrossRef]

- Traore, B.; Descheemaeker, K.; van Wijk, M.T.; Corbeels, M.; Supit, I.; Giller, K.E. Modelling cereal crops to assess future climate risk for family food self-sufficiency in southern Mali. Field Crops Research 2017, 201, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, A.; Donkor, E.; Owusu, V. Climate change adaptation strategies, productivity and sustainable food security in southern Mali. Climatic Change 2020, 159, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Boote, K.J.; Kimball, B.A.; Ziska, L.H.; Izaurralde, R.C.; Ort, D.; Thomson, A.M.; Wolfe, D. Climate impacts on agriculture: Implications for crop production. Agronomy Journal 2011, 103, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traore, B.; Van Wijk, M.T.; Descheemaeker, K.; Corbeels, M.; Rufino, M.C.; Giller, K.E. Climate Variability and Change in Southern Mali: Learning from Farmer Perceptions and on-Farm Trials. Experimental Agriculture 2015, 51, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akumaga, U.; Tarhule, A.; Piani, C.; Traore, B.; Yusuf, A.A. Utilizing process-based modeling to assess the impact of climate change on crop yields and adaptation options in the Niger river Basin, West Africa. Agronomy 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, B.; MacRon, C.; Monerie, P.A. Fewer rainy days and more extreme rainfall by the end of the century in Southern Africa. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpandeli, S.; Naidoo, D.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Nhemachena, C.; Nhamo, L.; Liphadzi, S.; Hlahla, S.; Modi, A.T. Climate change adaptation through the water-energy-food nexus in Southern Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhamo, L.; Matchaya, G.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Nhlengethwa, S.; Nhemachena, C.; Mpandeli, S. Cereal production trends under climate change: Impacts and adaptation strategies in Southern Africa. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2019, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupangwa, W.; Chipindu, L.; Ncube, B.; Mkuhlani, S.; Nhantumbo, N.; Masvaya, E.; Ngwira, A.; Moeletsi, M.; Nyagumbo, I.; Liben, F. Temporal Changes in Minimum and Maximum Temperatures at Selected Locations of Southern Africa. Climate 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, O.; Hachigonta, S.; Tadross, M. Sensitivity of southern African maize yields to the definition of sowing dekad in a changing climate. Climatic Change 2011, 106, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, M.V.; Das, H.P.; Brunini, O. Impacts of present and future climate variability and change on agriculture and forestry in the arid and semi-arid tropics. Climatic Change 2005, 70, 31–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.S.; Twyman, C.; Osbahr, H.; Hewitson, B. Adaptation to climate change and variability: Farmer responses to intra- seasonal precipitation trends in South Africa. Climatic Change 2007, 83, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenker, W.; Lobell, D.B. Robust negative impacts of climate change on African agriculture. Environmental Research Letters 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, S.; Jamil, F.; Roson, R.; Sartori, M. Do farmers adapt to climate change? A macro perspective. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim, N.; Zorita, E.; Hünicke, B.; Ivanciu, I. The impact of the Agulhas Current system on precipitation in southern Africa in regional climate simulations covering the recent past and future. Weather and Climate Dynamics 2023, 4, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, B.; Roudier, P.; Quirion, P.; Alhassane, A.; Muller, B.; Dingkuhn, M.; Ciais, P.; Guimberteau, M.; Traore, S.; Baron, C. Assessing climate change impacts on sorghum and millet yields in the Sudanian and Sahelian savannas of West Africa. Environmental Research Letters 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; de Beurs, K.; Vrieling, A. The response of African land surface phenology to large scale climate oscillations. Remote Sensing of Environment 2010, 114, 2286–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbetibouo, G.A.; Hassan, R.M. Measuring the economic impact of climate change on major South African field crops: A Ricardian approach. Global and Planetary Change 2005, 47, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Miller, J.; Künne, A.; Kralisch, S. Using soil-moisture drought indices to evaluate key indicators of agricultural drought in semi-arid Mediterranean Southern Africa. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilomboleni, H.; Recha, J.; Radeny, M.; Osumba, J. Scaling climate resilient seed systems through SMEs in Eastern and Southern Africa: challenges and opportunities. Climate and Development 2023, 15, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopper, E.; Vogel, C.H.; Landman, W.A. Seasonal climate forecasts - Potential agricultural-risk management tools? Climatic Change 2006, 76, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Precipitation Range (mm/Month) | Category |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | <60 | Very dry |

| 2 | 60 - <100 | Dry |

| 3 | 100 - <150 | Moderate (drier) |

| 4 | 150-<200 | Moderate (wetter) |

| 5 | 200-<300 | Wet |

| 6 | >300 | Very wet |

| Database | Search Carried Out | Article Found | Search Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( impact AND climate AND change AND on AND agriculture AND southern AND africa ) | 213 | 19/11/2023 |

| Web of Science | ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( impact AND climate AND change AND on AND agriculture AND southern AND africa ) | 218 | 15/12/2023 |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Have been published between 2000 and 2023 Written in English |

Articles published outside the period 2000 to 2023 |

| Being an article on addressing climate change in agriculture | Works that did not address climate change in agriculture |

| Be an article, thesis, dissertation, or complete report | Articles not available in full and in languages other than English |

| Database | Website Address | Number | Access Date | Search Equation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | https://www.scopus.com/ | 213 | 19November2023 | Search equation |

| WoS | https://www.webofscience.com/ | 218 | 15December2023 | Search equation |

| Academic Google |

https://www.sciencedirect.com/ https://www.sciencedirect.com/ https://iopscience.iop.org/ https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/ http://iopscience.iop.org/ https://scholar.google.com.br/ https://royalsocietypublishing.org https://www.tandfonline.com/ https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ https://iopscience.iop.org/ https://documents1.worldbank.org/ |

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 |

30/January 2024 30/January 2024 30/January 2024 30/January 2024 30/January 2024 30/January 2024 30/January 2024 30/January 2024 30/January 2024 03/February 2024 30/January 2024 |

Citation search Citation search Citation search Citation search Citation search Citation search Citation search Citation search Citation search Website Website |

| Country Average |

2011-2016 | 2015 Corn Production | 2016 Corn Production | % Change 2015/2016 | Number of People Affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 1366 | 878 | 1500 | -20 | 756000 |

| Agroclimatic Variable | Author(s) | Culture | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to temperatures above 35ºC | [4,55,61] | Corn | Pollen viability decreases, which negatively impacts grain set, resulting in reduced yields. Thermal stress in crops and water loss through evaporation. |

| Daytime temperatures > 35 ÿC | [61] | Cereals | They limit the growth and overall productivity of cereals. |

| Extreme daytime temperatures | [61] | Cereals | It causes rapid depletion of soil moisture through an increase in evapotranspiration. |

| Increase in minimum temperatures | [61] | Arvenses | Potentially promotes early senescence, which in turn shortens the grain-filling period, resulting in low yields |

| Lack of precipitation | [4] | Cereals | Extend growing seasons |

| Heavy precipitation | [4] | Cereals | They cause soil flooding, anaerobicity, and reduced plant growth. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).