1. Introduction

Supply chain (SC) systems have undergone significant transformations in recent years, driven by the proliferation of data, devices, users, and stakeholders. These advancements have improved efficiency and visibility; however, they introduced new security challenges and threats. For example, a 2017 NotPetya ransomware SC attack, which focused on encrypting and locking data for ransom rather than stealing it [

1]. Additionally, the SolarWinds sunburst attack in 2020 compromised numerous companies globally, gaining unauthorized access to sensitive data for thousands of customers [

2]..

The sprawling interconnections within contemporary SC systems, encompassing a multitude of stakeholders, technologies, and geographies, introduce vulnerabilities that malicious actors can exploit. The problem is compounded as the advent of big data further amplifies the complexity of security breaches in SC. The exponential growth in data generated throughout the SC, including information from procurement and production to distribution and customer interactions, offers both opportunities and risks. Big data analytics can offer valuable insights for optimizing operations, forecasting demands, and enhancing customer experiences; however, it also expands the attack surface, making organizations susceptible to potential breaches, this is particularly evident in the case of identity-based attacks, which encompass the theft or misuse of user credentials, privileges, or personal information. System participants with access to large datasets may unintentionally or intentionally misuse or leak sensitive information.

Cyber-attacks, data breaches, mistrust, counterfeiting, and physical disruptions remain looming threats in SC systems. Recently, ensuring SC security entails safeguarding physical assets and sensitive information, ensuring the integrity of digital transactions, and bolstering the overall network’s resilience against emerging threats. The security landscape of a contemporary SC is marked by intricate challenges that necessitate proactive and adaptable threat prevention, detection, and response security mechanisms; therefore, a comprehensive approach to SC security necessitates continuous assessments, collaborative efforts among stakeholders, and the implementation of robust cyber-security mechanisms, while utilizing the power of big data to identify, predict, and mitigate risks, ensuring the seamless flow of goods, services, and information.

The foundation of a SC rests on the bedrock of trust among its diverse stakeholders. This expansive and intricate system is based on a combination of technologies, human expertise, organizational structures, and established protocols to protect its networks, devices, services, finances, and other vulnerable resources from threats, damage, or unauthorized access [

3]. Initially, there was a belief that fostering trust between SC participants would diminish risk; however, the reality is that increased trust can paradoxically give rise to increased risk, manifesting itself in the form of internal or external threats. Indeed, the SC landscape has witnessed an increased incidence of attacks, which includes strategies malicious software or hardware insertion, node replication, and eavesdropping [

4]. Endeavors aimed at fortifying the security and traceability of digital SC systems are not novel. Concerted efforts are underway to develop effective strategies that can counter these threats and establish a dependable system of traceability while being accountable and secure.

The pivotal role of trust within SC systems, while fostering collaboration and cooperation, introduces a subtle yet significant vulnerability that malicious actors are adept at exploiting. The interdependence and reliance on shared information among stakeholders can inadvertently open avenues for security breaches. As trust grows, stakeholders tend to share more information and grant broader access to each other, creating a larger potential attack surface. This inherent reliance on trust can lead to complacency in security measures, since the assumption of mutual goodwill might overshadow the necessity of stringent safeguards. Consequently, SC systems that are highly dependent on trust can unwittingly expose themselves to a higher risk of security attacks. These attacks may encompass various forms, such as exploiting the access granted by trusted relationships, infiltrating systems with malicious intent, and manipulating vulnerabilities within the network to disrupt operations or compromise sensitive data; therefore , while trust is the cornerstone of SC systems, it is crucial to acknowledge that it can inadvertently pave the way for security vulnerabilities if not complemented by robust and proactive security strategies.

On the other hand, Zero Trust (ZT) is a novel architectural security approach specifically crafted for safeguarding sensitive and confidential data within an SC’s intricate dynamics [

5]. The ZT architectural approach operates on the foundational premise that no human or non-human entities, also called subjects, requesting access to network resources can be automatically deemed trustworthy even following the initial authentication and authorization stages. Every access request is individually validated and cross-checked against the stipulated security policies in real-time during the access period, ensuring robust network security throughout the SC ecosystem. Central to ZT-based security is the acknowledgment that potential threats may emerge from within and outside the SC system, which includes a wide spectrum of SC stakeholders, ranging from suppliers and manufacturers to logistics providers, distributors, customers, employees, competitors, software developers, and regulatory or governmental entities. This diverse array of stakeholders presents a mosaic of potential risks. Consequently, SC can proactively counteract a broad spectrum of security risks by rigorously adhering to these measures, enhancing the system’s overall resilience.

The ZT concept creates notable advancements in security; however, the comprehensive verification and monitoring processes can lead to increased complexity and potential performance overhead. Moreover, successful ZT implementation relies heavily on accurate and up-to-date information about users, devices, and their behaviors, which can be challenging to maintain in dynamic and large-scale environments. Integrating blockchain (BC) technology presents a solution to these challenges. BC constructs a decentralized and immutable ledger that can securely record and verify transactions, actions, and identities that enable exchanges between multiple parties in a secure, immutable manner [

6]. This transparency and immutability can enhance the accuracy of data used in ZT mechanisms, ensuring that the information on which security decisions are based remains trustworthy. Additionally, BC’s ability to establish tamper-resistant audit trails and enforce smart contracts can augment the real-time monitoring and compliance enforcement required by the ZT approach. Organizations can potentially create a more robust and resilient security framework that addresses limitations while fostering a higher level of trust and security within complex systems, such as a SC, by combining the strengths of ZT and BC. Furthermore incorporating machine learning (ML) algorithms is a potent strategy to bolster security protocols. ML algorithms can scrutinize network traffic in real-time, discerning anomalies or patterns that could signify an impending security hazard. The algorithms are adept at observing the conduct of both network devices and users, promptly identifying any deviations or suspicious actions that might signal a prospective security breach. Deep learning (DL) and Reinforcement Learning (RL) can be integrated to create deep reinforcement learning (DRL) algorithm, which represents an effective solution for building an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) embedded into the ZT architecture to gain an elevated capacity, and to efficiently and promptly detect and thwart security threats in real-time, rendering the entire security framework more potent and resilient.

Efforts have been made to use BC for integrating decentralization, privacy, identity management, secure authentication, trust evaluation, penalty enforcement, and attack prevention. Simultaneously, ML is employed to construct efficient IDS within ZT architecture. Despite these attempts, a comprehensive security system that encompasses all these technologies in a unified solution is currently lacking. This challenge motivated the design a comprehensive conceptual ZT security framework that leverages BC and DRL engines to deploy the necessary ZT architecture in the SC context. Our proposed framework, BC-DRLzSC, enables a trustworthy and secure environment for SC. Specifically, BC technology’s ability is utilized in the proposed framework to strengthen the stakeholders’ registration and authentication process, specifically in the context of smart contracts. On the other hand, IDS is tailored to the intricacies of the SC domain. This approach hinges on the utilization of a distributed Q-learning model. Q-learning-based RL model facilitates decision-making within a given context. The principal goal involves establishing an optimal strategy for an agent operating in a specific environment. In this context, "strategy" refers to a predefined sequence of actions for each state of the environment, analogous to detecting attacks within the SC. Thus, in this articel a self-learning system is developed with adaptability and evolution, integrating principles from the ZT architecture and the Q-learning framework. This fusion enhances proactive attack detection in the dynamic landscape of the SC domain.

This paper’s key contribution is the introduction of BC-DRLzSC, a hybrid security framework safeguarding the SC against cyber-attacks. This framework can be clarified by:

Proposing a new architectural solution, called BC-DRLzSC, using the potential of BC, DRL, and the principle of a ZT architecture.

Employing BC through the use of smart contracts for system identity registration, authentication, and resource access control, Where two proposed smart contracts manage these aspects within a Verifiable Byzantine Fault Tolerance (VBFT) based public BC.

Developing an IDS that leverages DRL algorithm integrated with ZT architecture for a proactive attack detection. Our methodology employs a decentralized Q-learning algorithm to monitor and predict unusual behaviors exhibited by the SC devices.

Evaluating the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed IDS through an extensive evaluation, focusing on key performance metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, precision, and detection rate. The evaluation was conducted comprehensive experiments using the NSL-KDD dataset to rigorously evaluate our system’s ability to detect various threats, which included widely recognized attack scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 establishes the foundational background of the ZT architecture, BC technology, and DRL approach in the context of the food SC.

Section 3 reviews the literature and identifies the recent work on combining BC and ZT for SC solutions.

Section 5 describes the proposed BS-DRLzSC security framework. The numerical results of our experiments are presented in

Section 7. Finally, the paper concluds in

Section 8.

2. PRELIMINARIES

This section briefly overviews the ZT principle, BC in the context of enhancing security and preventing cyber-attacks, and DRL for constructing efficient IDS for proactive attack detection.

2.1. Zero Trust

The philosophy of "never trust, always verify and enforce least access privilege," a principle that supports“ identity is the new perimeter,” aims to strengthen the security for each device, user, and connection for all transactions [

7,

8]. ZT assumes that devices or users on the network can’t be trusted by default regardless of its physical location; therefore, there is a need to have strict access policies and security mechanisms in place to authenticate and authorize nodes and users so that the network’s sensitive data resources sre protected [

5,

9].

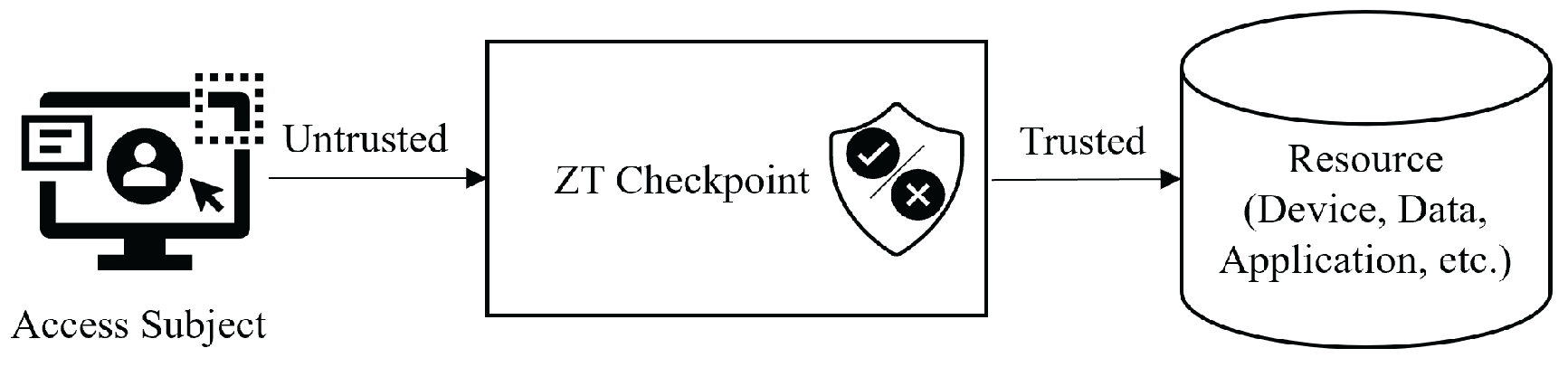

Figure 1 demonstrates an abstract ZT model in which the ZT checkpoint must ensure that the subject is authentic and the request is valid to access an enterprise resource using authentication, authorization, and access control security policies. Failure to meet these policies results in access denial or revocation.

The ZT security approach should encompass several key assets that are essential for building a robust security framework within organizations, including:

Identity: All users and devices must undergo rigorous authentication and authorization processes in a ZT environment. Trust is never assumed, regardless of the entity’s location.

Data: Protecting sensitive data is paramount in the ZT framework. That involves employing encryption, data classification, and strict data access controls to prevent unauthorized access and mitigate data breaches.

Devices and Workloads: ZT extends its security measures to encompass devices and workloads operating within the network. Continuous monitoring and validation of these endpoints are essential to ensure security and compliance with established security policies.

Analytics and Visibility: ZT relies heavily on advanced analytics and visibility tools. Real-time network and user behavior monitoring allows for the early detection of vulnerabilities and potential security threats.

Automation and Orchestration: Automation and orchestration are critical ZT components. Security processes are automated to respond rapidly to security incidents. Orchestrating security actions across the network enhances adaptability in the face of evolving threats.

Network and Endpoint Security: ZT imposes stringent security controls on network traffic and individual endpoints, including network segmentation, micro-segmentation, and robust endpoint security measures to minimize attack surfaces and reduce the impact of security breaches.

Organizations can adopt a ZT approach that prioritizes security at every level by integrating these key assets into a comprehensive security framework. This proactive model assumes both inside and outside threats, making continuous monitoring and identity verification essential for protecting sensitive assets and data.

Figure 1.

Abstract ZT model

Figure 1.

Abstract ZT model

2.2. Blockchain

BC was first introduced for cryptocurrency by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008. BC is a secure, distributed database where digital ledgers store unalterable, untampered data records of transactions in the form of blocks. Each transaction is validated by independent nodes, also known as voters, validators, peers, or miners, without mutual trust. Each group of validated transactions is mined in a block. Each block has two cryptographic hash codes: one for the previous block and one for the current block, meaning that each block is linked to the previous block using a cryptographic hash code. The block’s hash code is changed if another block’s information is changed which means it is not feasible to change any of the blocks’ contents after mining. The trust is distributed among all participants using BC consensus. The consensus mechanism ensures decentralization in validating transactions across the BC Peer-to-Peer (P2P) network. BC is an ideal architecture for applications that require distributed transactions between all participants and decentralize computation and management in a trustless environment, especially considering its main features: data immutability, decentralization, transparency, security and resilience, data signatures, consensus, and smart contracts [

10,

11].

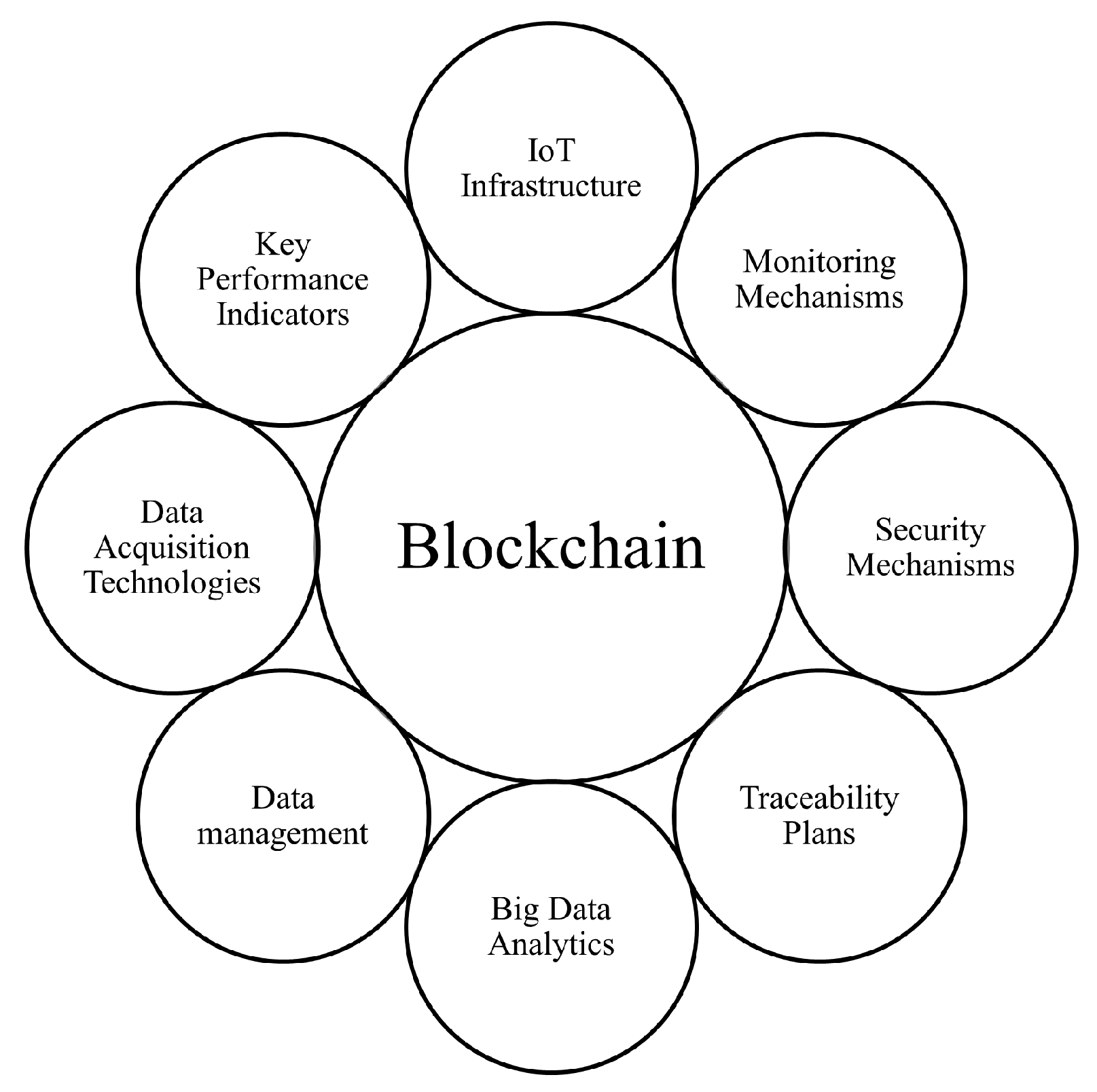

The following key elements are important to consider when implementing BC in SC [

12] (

Figure 2):

Data Acquisition Technologies: IoT devices, sensors, and other data sources are essential for collecting data from various points in the SC which is cryptographically secured on the BC. All data is treated as untrusted until verified in a ZT environment.

Internet of Things (IoT) Infrastructure: IoT infrastructure is integral in BC-based SC implementations since it provides real-time track and trace data for the products throughout their movement in the SC.

Data Management Platforms: Data management platforms can securely store and manage SC information in a distributed ledger, which aligns with the principle of ZT, since access to this data is controlled and monitored, and trust is not automatically granted to any party.

Big Data Analytics: Big Data analytics can be applied to the data stored in the BC. Data analysis can be used to detect threats or security breaches, aligning with ZT’s continuous monitoring and verification principles.

Traceability Plans: BC enables end-to-end traceability, allowing stakeholders to track a product’s journey from source to destination ensuring transparency, product authenticity, and quality.

Monitoring Mechanisms: BC facilitates real-time SC activity monitoring, allowing for an immediate response to security threats. This constant monitoring aligns with the principle of ZT of not trusting any entity by default and verifying all actions.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): KPIs include security-related metrics that gauge SC security measure effectiveness. These KPIs help ensure that security is continuously assessed and improved in a ZT environment.

The key elements of BC implementation in a SC are foundational for creating a ZT environment. SC stakeholders can establish a transparent, secure, and verifiable ecosystem by leveraging BC technology, where trust is built upon continuous validation and monitoring, instead of relying on inherent trust in any entity.

Figure 2.

BC implementation elements in SC

Figure 2.

BC implementation elements in SC

2.3. Deep Reinforcement Learning

DRL is a specialized subset of ML that combines the foundations of DL and RL to handle complex features and significantly enhance the overall accuracy of IDS.

DRL has emerged as a solution to the limitations of Q-learning by employing deep neural networks to approximate the Q-function. This innovation allows for effectively managing state spaces with high dimensions. This approach is commonly referred to as Deep Q-Network (DQN), seamlessly integrating Q-learning with deep neural networks to empower agents to acquire knowledge from inputs with complex, high-dimensional characteristics.

Moreover, DRL algorithms such as DQN offer the flexibility to incorporate alternative exploration strategies, such as softmax action selection or bootstrapped ensembles, which enhance an agent’s ability to navigate the environment efficiently. This balance between exploration and exploitation accelerates the agent’s learning process and improves IDS performance.

In traditional Q-learning, a table is constructed to store state-action pairs, helping determine the best action for a given state. Q-learning often employs the -greedy approach as an exploration strategy to explore potential rewards, which involves randomly selecting an action with a probability of ; however, creating and maintaining a Q-table can be computationally demanding, and may not explore the entire state space thoroughly, resulting in infrequent visits to certain states.

The proposed BC-DRLzSC framework integrates DRL-IDS in a ZT architecture, offering a proactive attack detection within the SC. This system can continuously learn and adapt to evolving attack patterns and vulnerabilities, optimizing decisions to protect the SC while minimizing disruptions. Simultaneously, ZT architecture ensures that every component, whether a device or a user, is subjected to rigorous authentication and validation, reducing the attack surface. This integration facilitates real-time SC operation monitoring and effectively identifies and mitigates threats before they can cause significant damage. As a result, integrating DRL into ZT architecture fortifies the SC against potential cyber-attacks, safeguarding its integrity and ensuring smooth operations.

3. Related Work

The recent surge in interest surrounding BC technology has motivated innovative organizations, entrepreneurs, and researchers to investigate its potential in SC systems [

13,

14]. The primary objective of integrating BC with SC systems is ensuring precise data tracking and secure authentication within the chain [

15]. The authors of [

16] and [

17] highlighted that BC strengthens SC systems security by using a consensus mechanism for dynamic data storage, ensuring secure end-to-end data transmission, and enabling effective product traceability and monitoring. The authors of [

18] specifically addressed threats and attack models that can lead to data tampering in a BC-based SC system. They emphasized the challenge arising from the absence of digitization in different sub-processes of the SC, which hinders the establishment of trust. This drawback significantly obstructs the implementation of a SC system based on BC. These constraints arise primarily from the inherent limitations of the widely utilized classical role-based access control (RBAC) model within the SC [

5]. The research described in [

19] recognized this limitation and proposed a ZT access scheme for designing a consortium BC-based system that has a malicious monitor node. The primary objectives of this proposed scheme were to improve user anonymity and strengthen the security of the access control process in cross-organizational networks, such as those found in SCs. These goals were achieved by implementing multi-signature protocols and smart contracts.

Similarly to BC, DRL has experienced exponential growth in the last decade [

20,

21], and there is currently strong interest in exploring the use of DRL to improve SC network performance (

Table 1) [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]; however, [

22] is the only work reported in the literature that introduces a distributed collaborative dynamic access control scheme utilizing DRL, and redefining network security architecture by combining anomaly detection, dynamic updates to user trust profiles, and collaborative adjustments for mitigation policies, to the best of authors knowledge. This scheme addresses the escalating challenge of insider threats in network security. The work described in [

22] demonstrates the scheme’s effectiveness through meticulous analysis and evaluations against various objectives related to insider threat mitigation’ however, its limitations include the complexity of balancing limited network resources amid dynamic requests and the necessity for a resource management policy adaptable to network dynamics. Additionally, the scheme’s effectiveness may be influenced by the accurate predicting state transitions and properly handling uncertainties in network dynamics.

This paper proposes a trustless framework, BC-DRLzSC, to secure SC systems. The primary objective is to showcase the potential of integrating BC and DRL in a ZT environment as a layered architecture to protect SCs from possible threats. The article discusses BC-DRLzSC, including the overall design, architecture, simulation experiments, and results, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the framework.

4. Identity-Based Cyber-attacks in Supply Chain

Cyber-attacks in the SC are malicious activities aimed at disrupting, compromising, or exploiting the interconnected network of organizations and stakeholders involved in producing, distributing, and delivering products and services. These attacks include data tempering, malware insertion, and identity attacks, often targeting vulnerabilities within the SC ecosystem.

Identity attacks, also known as identity-based attacks or identity-related attacks, refer to cyber-security threats that specifically target the entity identity. These attacks exploit vulnerabilities related to node identification, authentication, authorization, and access controls in the SC ecosystem. Identity attacks can cause misuse, privilege abuse, tampering, and fraud, leading to operation disruption, sensitive data compromises, reputational damage, and financial losses.

The most commonly known identity attacks are:

Identity Spoofing: the attacker attempts to impersonate a legitimate SC actor and generate fake transactions on its behalf to gain unauthorized access. Attackers may use stolen credentials or manipulate headers to appear as authorized entities.

Counterfeit Identity: the attacker creates a fake identity to infiltrate the SC network and gain access to sensitive information or systems. Attackers might pose as authorized personnel to place orders, alter specifications, or manipulate logistics.

Insider attackers: Insiders are usually current or former actors or business associates who have privileges to access sensitive information or privileged accounts in the SC. Insiders might abuse their credentials to steal sensitive information, manipulate orders, or cause disruptions.

Brute Force Attack: the attacker systematically exploits all possible usernames and passwords combinations until the correct combination is found, allowing unauthorized access to an enterprise resource. Weak identity credentials can be easily exploited using automated tools.

Account Hijacking: the attacker takes control of SC-related accounts, such as shipping or inventory management systems, to perform actions on their behalf, such as diverting shipments or altering inventory records, which can result in shipment delays, inventory inaccuracies, and financial losses.

Phishing: the attacker often impersonates a legitimate identity, such as banks or service providers, by sending fraudulent emails or messages to trick network participants into revealing their sensitive information, including user credentials and credit card details.

Man-in-the-Middle (MITM): the attacker intercepts the communication between two SC parties, often without their knowledge, allowing the attacker to eavesdrop on sensitive information, modify data, or inject malicious content into the communication.

Malicious Insertion: the attacker targets hardware or software components within the SC and inserts malicious code or firmware. These compromised components can lead to security vulnerabilities, data breaches, or operational disruptions.

Protecting against these threats present a multifaceted challenge. Big Data analysis enables the early identification of unusual patterns and potential cyber threats in user behavior and access in the SC system. In the proposed framework, this approach is implemented through an IDS empowered by a DRL algorithm to detect intrusions and cyber-attacks proactively and collaboratively. Incorporating ZT architecture, where no entity, whether internal or external, is inherently trusted, requires continuously verifying an individual’s identity and permissions throughout the SC ecosystem, making it highly effective at detecting and preventing identity attacks. This approach establishes a stringent security framework that prioritizes continuous verification and access control, minimizing the risk of unauthorized access or breaches within the SC.

On the other hand, BC, has a transparent and immutable ledger, making it significantly more challenging for attackers to manipulate or compromise product and information identity and integrity within the SC. BC’s cryptographic mechanisms and smart contracts add layers of security, deterring unauthorized access or identity attacks. BC’s decentralized nature ensures that once data is recorded, it is resistant to tampering and fraud, enhancing SC transaction verification and security and reducing the risk of unauthorized access.

5. Proposed BC-DRLzSC Hybrid Security Framework

Our SC system tracks and traces the product throughout its different stages starting from harvesting, and continuing through manufacturing, packaging, shipping, distribution, and delivery. Building an architecture for a SC system involves developing a security plan at the enterprise level and imposing policies to control, monitor, and maintain the relationships of transactions, stakeholders, finances, information, and flows of products and services.

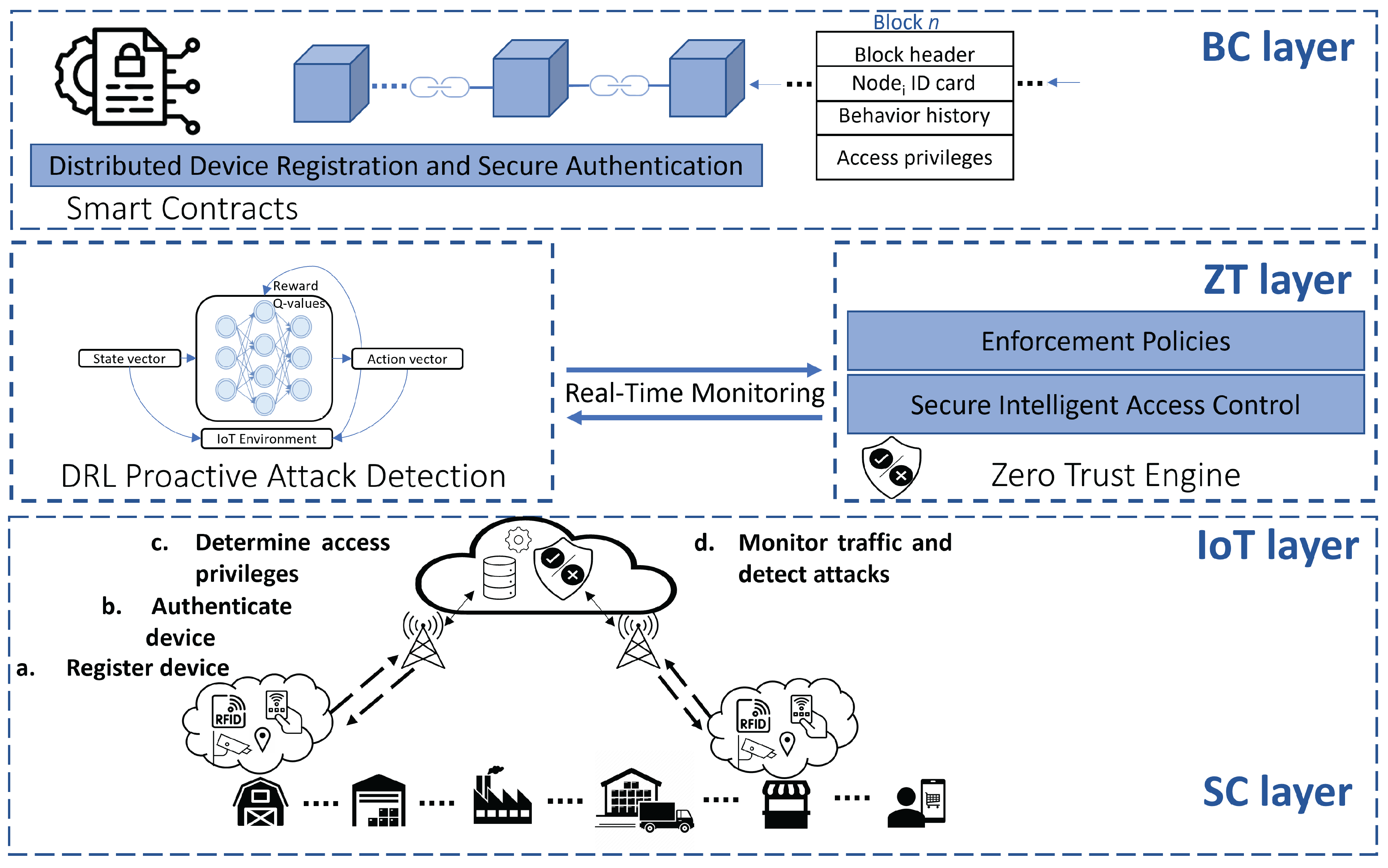

Introducing a BC-DRLzSC hybrid security framework empowered by BC and ML integrated into a ZT architecture can be characterized into four layers: SC, IoT, ZT, and BC (

Figure 4). These layers work as a whole to provide reliable services and data transparency. Adopting BC and ZT within the SC is in its early stages, primarily due to the novelty of these technologies, the complexity that will be added to the already complex SC ecosystem, and limited awareness among stakeholders regarding the unrealized ability to enhance trust and security, eliminate dependence on a central authority, and respond to continuously evolving cyber-threats.

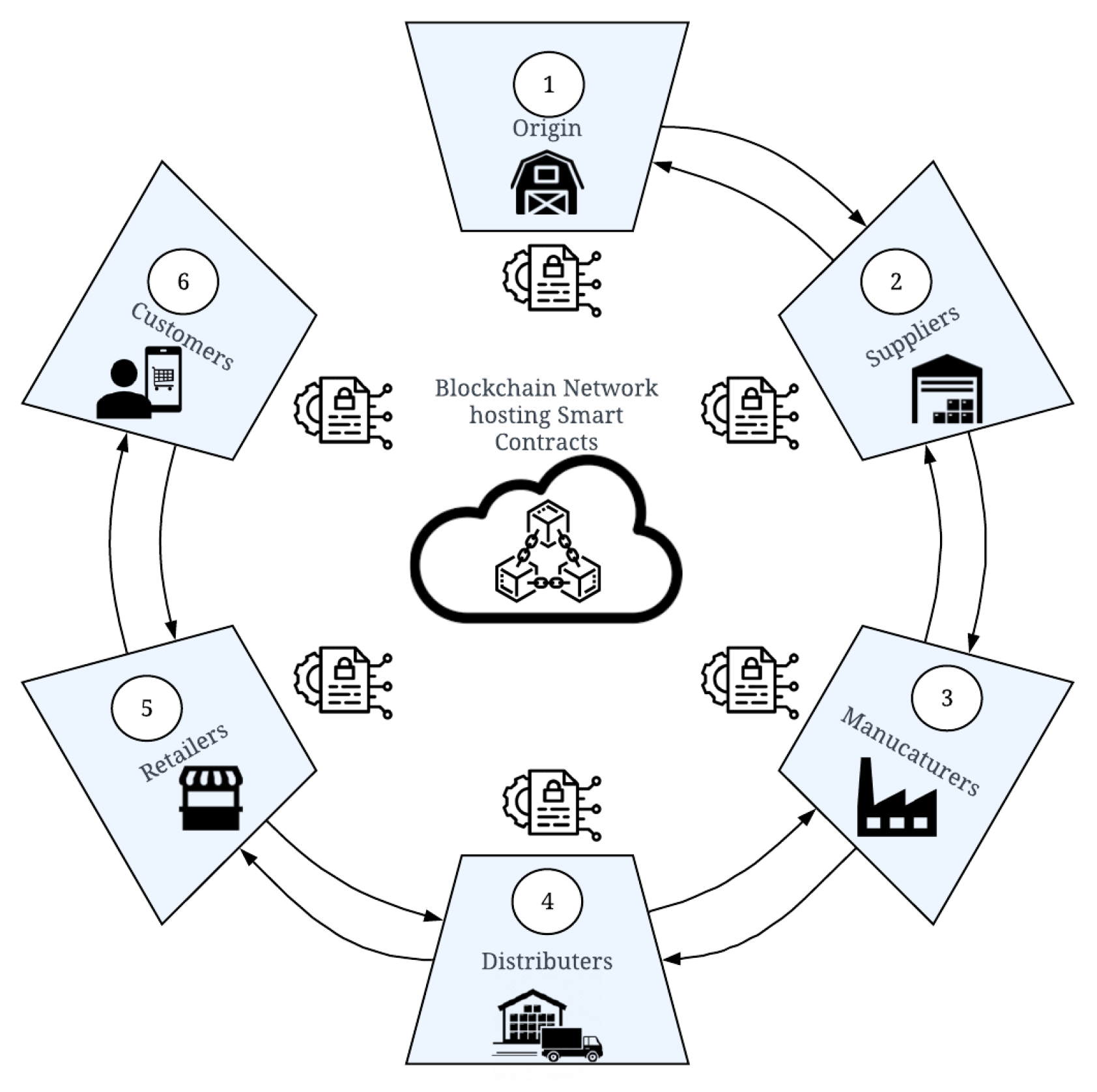

5.1. SC Layer

The SC layer consists of the system actors, that play the role of nodes communication and transaction for the product’s physical flow. The main actors are briefly introduced in the following with their associated activities (

Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Typical flow of BC-based SC scenario

Figure 3.

Typical flow of BC-based SC scenario

Origin: the source of raw materials where the product is cultivated, harvested, processed, and packed.

Supplier: also involved in processing, and packaging for distribution.

Manufacturer: performs actions from simple packaging to complex manufacturing processes and sets product quality specifications.

Distributor (or Wholesaler): acquires the products from various manufacturers in one place, called a distribution center, and assemble, or packages them.

Retailer: sells the products, monitors and analyzes product conditions, and provides APIs for end-consumers.

Consumers: usually have fewer rights than other actors, including viewing the product’s origin and history and verifying product authenticity.

Actors demand a level of transparency supported by BC consensus. These actors are a set of strangers, where each stranger is both watching everyone else and is watched by everyone [

27].

Figure 4.

Proposed BC-DRLzSC layered architecture

Figure 4.

Proposed BC-DRLzSC layered architecture

5.2. IoT Layer

Track and trace information are collected using an IoT layer, validated and secured, then recorded on the distributed ledger at the BC layer and shared among actors. This activity protects the integrity of the products and stakeholders’ sensitive data. The IoT layer consists of IoT devices that are scattered across the different stages at strategic SC locations to collect real-time track and trace data. IoT devices can trigger automated actions, such as adjusting temperature controls in response to environmental changes, preventing SC disruptions. IoT devices are usually connected through a central cloud server such as the case of cloud architecture. IoT devices communicating to and from these cloud servers are exposed to different kinds of threats. BC networks provide P2P connectivity without including any third party. IoT-generated data is fed into the ML detection module for cyber-attack predictions.

5.3. ZT Layer

Our proposed BS-DRLzSC security framework aligns with the ZT principle using the ZT controller and advocates for integrating:

BC by ensuring node registration and authentication and transaction validation and verification.

Secure Intelligent Access Control where ZT enforces the principle of least privilege, which means that users, devices, and applications are granted the minimum access required to perform their tasks. This action limits the potential damage caused by a security breach. Access controls are based on factors such as user identity, device security posture, location, and the sensitivity of the data or resource being accessed. Every access request is scrutinized, and a user or device is given access only if they meet the specific criteria set by the access policies.

DRL detection module, which utilizes RL, a subset of ML that operates within the Markov Decision (MD) framework. This method equips the module with the ability to continuously learn device behavior and adapt to emerging threat patterns. RL utilizes MD to model the environment in situations where rewards or transition probabilities lack clarity,. The central objective of an RL agent is ascertaining an optimal mechanism that guides decision-making by mapping states to actions, enabling it to make informed choices based on its present state. The RL algorithm uses an iterative processes to enhance the agent’s decision-making proficiency over time. The agent refines its policy by selecting actions and receiving feedback in the form of rewards. This iterative interaction allows the agent to gradually discern actions that yield high rewards, eventually converging to an optimal policy that maximizes its expected cumulative reward over time.

5.4. BC Layer

BC decentralization minimizes the need for intermediaries, reducing the potential for third-party manipulation, and increasing transaction security, making it a transformative force for SC systems. Recording transactions to a distributed, shared, and immutable ledger makes a system more transparent, reliable, and, most importantly, reduces interference from third parties. BC, also called Distributed Ledger Technolofy ( DLT), enables data storage in the form of blocks, where each block contains a pointer to the previous block (

Figure 4). These pointers are established using cryptographic hash functions, widely used for data verification.

BC safeguards the SC system against potential threats in the BC-DRLZSC proposed framework, by integrating with smart contracts that are responsible for managing registration, authentication, and revocation of nodes, managing access to system resources, and ensuring the validation and verification of transactions communicated over the network. Exchanged transactions over the BC network collect information related to the SC activities. These transactions are encrypted and controlled by smart contracts and distributed to the involved stakeholders to permanently be recorded to the BC ledger. BC cryptography ensures that messages are encrypted and guaranteed and cannot be tampered with or falsified.

6. Smart Contracts

6.1. Implementation

Smart contracts, one of the critical elements in BC design, are responsible for connecting business logic and SC activity process execution [

28]. Smart contracts are event-driven programs stored in a BC database, then executed autonomously on the selected BC platform [

29]. We developed two smart contracts: identity management and resource management, using Solidity programming language for execution on the Ethereum platform. Identity management smart contract functions are called for entity registration, authentication, and revocation [

10], while resource management smart contract functions are called for gaining access to system resources. Smart contracts will be triggered when the different SC activities change states. The peer nodes along the SC will perform smart contract code execution, and the execution outcome should be agreed upon by all miners (

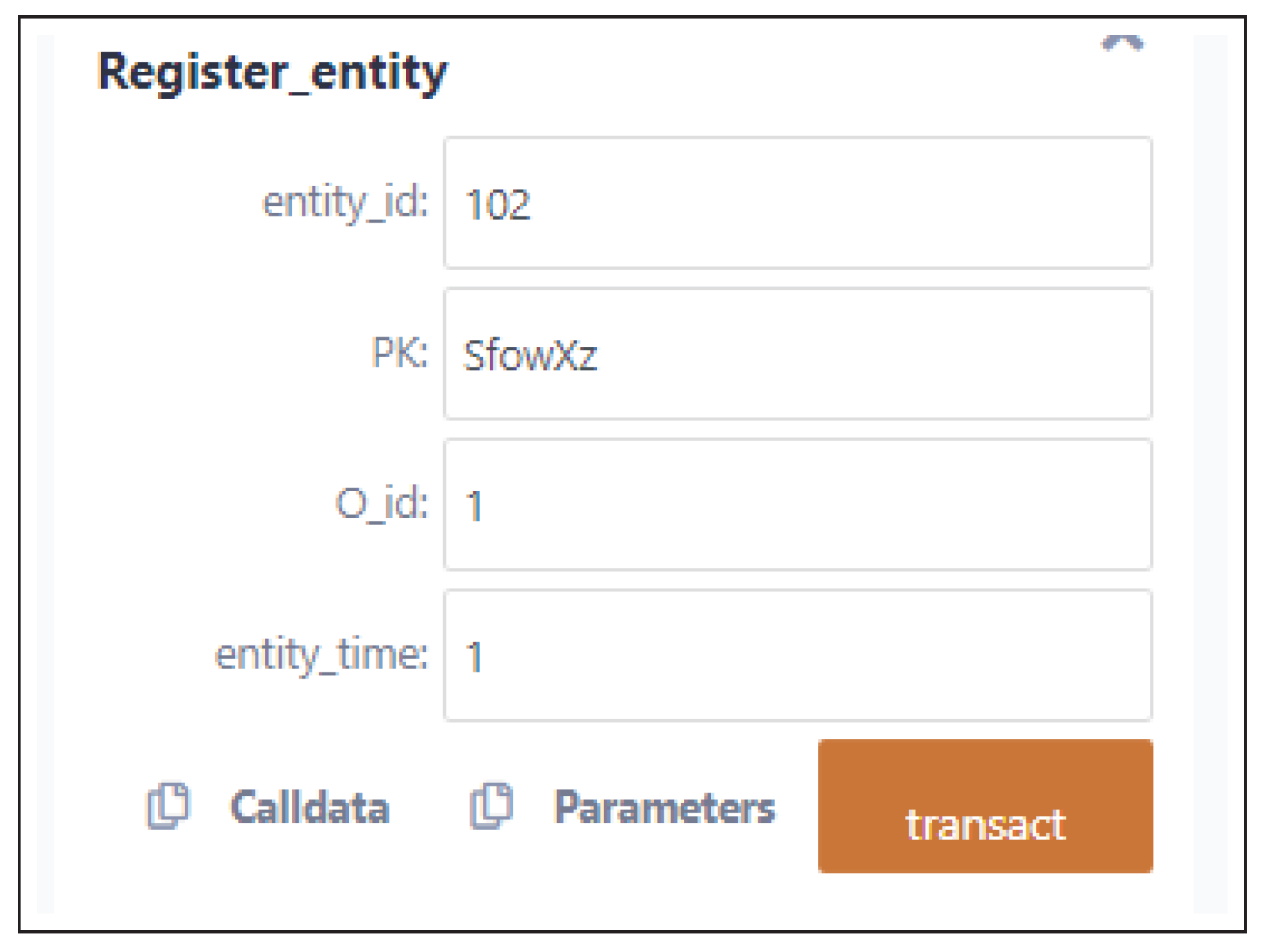

Figure 3). Identity creation depends heavily on the public key cryptography and hashing functions. The registration process should occur before a new device joins the SC system. Successful registration requires generating a cryptographic identifier in the form of a unique ID card (i.e., entity_id, PK, O_id, entity_time) before the device can be recognized for transactions exchange and be maintained throughout the device’s life cycle. One hashing function that works for ETH is called keccak256, which is built into Solidity and used to generate the hash of each node’s unique ID card using the following formula:

where

represents the hashed device identity and PA is usually the node’s physical/MAC address. The keccak256 function decreases costs in contrast to other hashing algorithms. Upon successful registration, BC deploys the smart contracts with all the required functions to be triggered when called, so peers abide by the terms and conditions stated in the smart contracts.

The proposed smart contracts functions can be briefly described as follows:

Register_entity(): creating and initializing an ID card for each unique identity.

Auth_entity(): matches the entity’s credentials against the registered login credentials.

Info_entity(): queries a specific entity information.

Revoke_entity(): removes the entity’s identity by invalidating its credentials.

Create_resource(): creates a new resource (i.e., Data, Application, etc.)

Access_resource(): requests access to a specific resource.

Update_resource(): updates a resource’s details.

Info_resource(): a view function that queries for a certain resource information.

Exit_resource(): returns true if a resource exits safely.

Total_resources(): queries of all system resources.

6.2. Evaluation

We used Solidity language and Remix IDE integrated with the Ethereum wallet using Metamask to develop smart contracts. Remix IDE offers a robust environment for deploying smart contracts, conducting testing, and assessing responses, providing feedback for each transaction and incorporating features for exception handling.

A transaction calling a contract function typically consumes more resources than other types of transactions. This transaction cost can be evaluated once run by a miner. Smart contracts have two types of functions: payable and non-payable. Payable functions transfer some Ethers to the contract upon execution. Non-payable functions, also called view functions, do not involve any Ether payment during execution. This type of function is employed within a contract solely for reading or performing actions that do not alter the contract’s state variables and do not require Ether payments to the contract. Examples of non-payable functions can be querying the contract’s state or conducting computations, such as Info_resource() and Total_resources(). We considered payable functions: Register_entity(), Auth_entity(), and Revoke_entity(), to evaluate identity management smart contract performance and Create_resource(), Total_resources(), Update_resource() to evaluate resource management smart contract performance.

Figure 5 depicts an example of calling Register_entity() and initializing the set of input parameters, including Entity ID and PK. The following log represents an example when the function Register_entity() successfully transacts.

from: 0x5B3...eddC4

to: IdentityManagement.Register_entity(uint256,string,uint256,uint256) 0xd91...39138

value: 0 wei

data: 0xc39...00000logs: 0

hash: 0xd6f...25ada

status 0x1 Transaction mined and execution succeed

transaction hash 0xd6f...25ada

block hash 0x8d8...fe4e5

block number 2

from 0x5B38Da6a701c568545dCfcB03FcB875f56beddC4

to IdentityManagement.Register_entity(uint256,string,uint256,uint256) 0xd9145CCE52D386f254917e481eB44e9943F39138

gas 226421 gas

transaction cost 183589 gas

execution cost 161613 gas

input 0xc39...00000

decoded input {

"uint256 entity_id": "102",

"string PK": "SfowXz",

"uint256 O_id": "1",

"uint256 entity_time": "1"

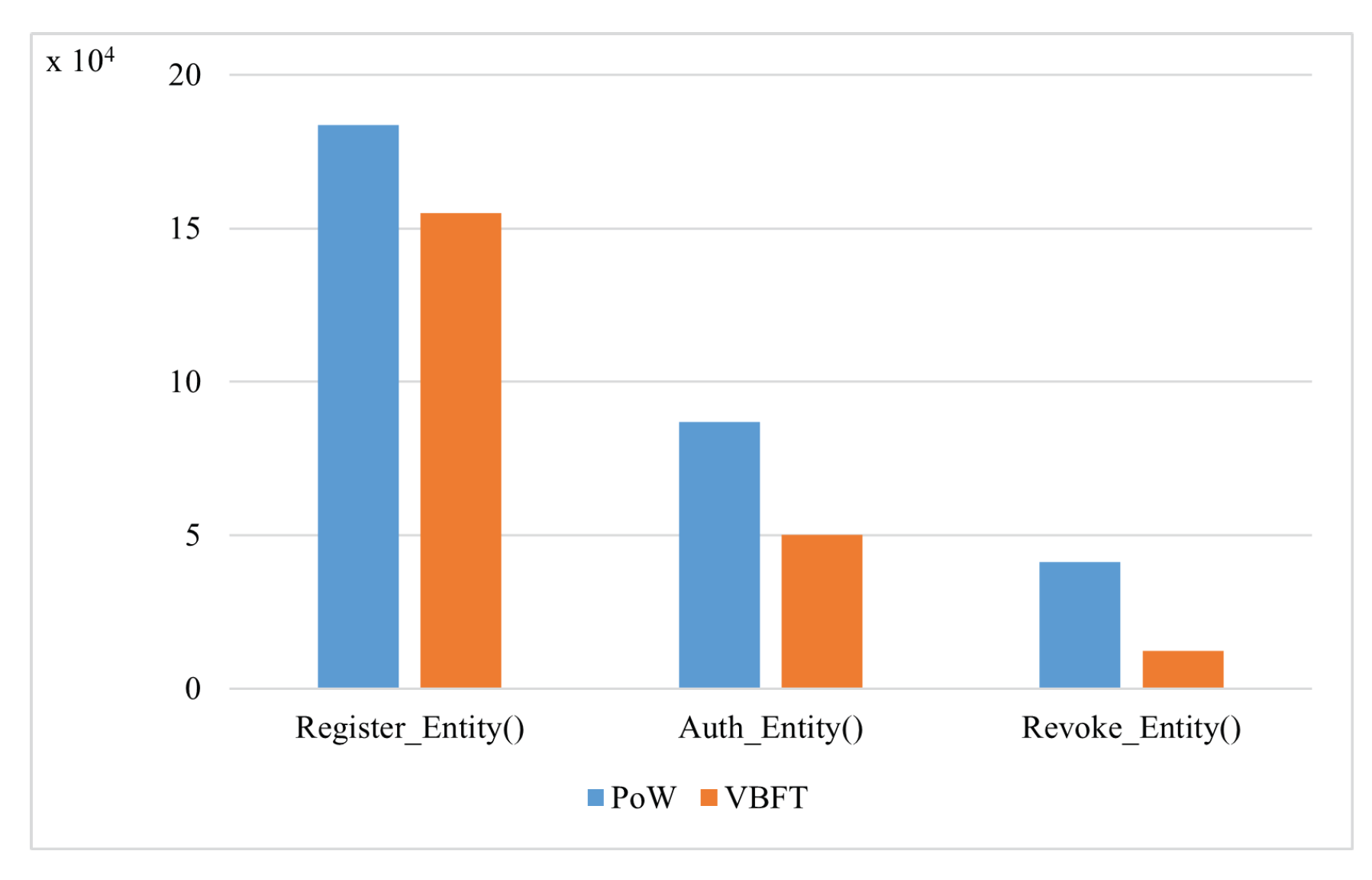

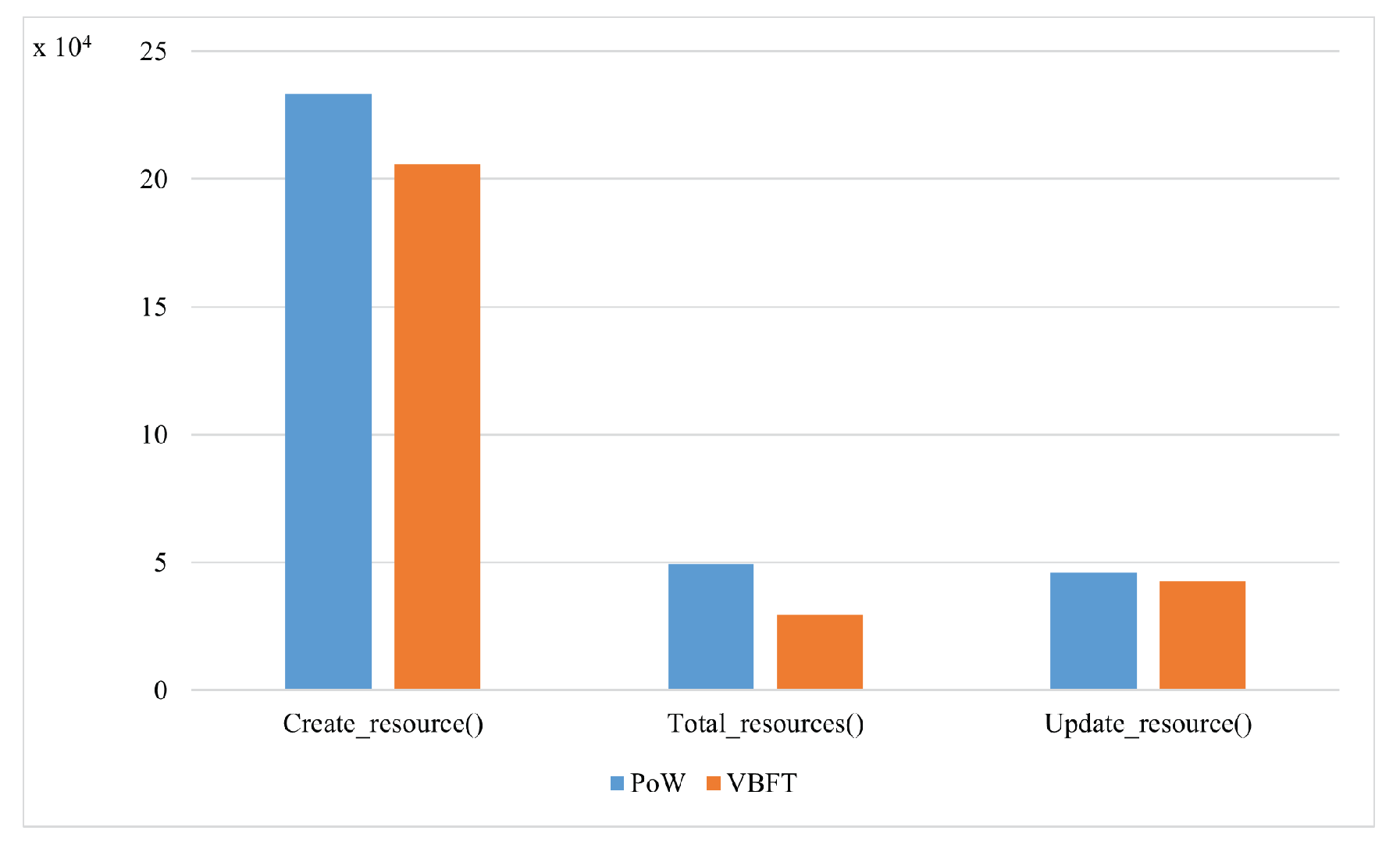

We tested the proposed smart contracts using two consensus algorithms: Proof ofWork (PoW) and VBFT. VBFT was adopted as the consensus mechanism for the proposed framework. VBFT is an enhanced version of the traditional Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT), created by introducing verifiable randomness in the selection of consensus peers for the next block. The randomness adds an additional layer of security to the consensus process. We used PoW as a benchmark scheme, where the nodes compete to solve a mathematical puzzle.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 depict the results of the average transaction costs for the identity management and resource management smart contracts, respectively. VBFT reduced the transaction cost of calling the functions of both smart contracts compared to PoW. PoW is resource-intensive since miners need powerful hardware to solve complex mathematical problems which causes high power consumption.

Figure 5.

Inputs of Register_entity() from Identity Management Smart Contract.

Figure 5.

Inputs of Register_entity() from Identity Management Smart Contract.

Figure 6.

PoW vs VBFT performance for the identity management smart contract.

Figure 6.

PoW vs VBFT performance for the identity management smart contract.

Figure 7.

PoW vs VBFT performance for the resource management smart contract.

Figure 7.

PoW vs VBFT performance for the resource management smart contract.

7. Deep Reinforcement Learning IDS

7.1. Implementation

IDS leverage Big Data, as raw data accumulated from the SC, to help identify anomalies and deviations from the norm, providing real-time insights into potential security breaches.

RL stands as a variant of ML wherein an agent learns through trial and error, adjusting its actions in response to interactions with the environment. The agent’s objective is to maximize its cumulative reward, symbolized as

O, which is formulated as follows:

Q-learning, a widely-used technique within the realm of RL, employs a function denoted as Q to assess the quality of a pairing between a state and an action. The crux of Q-learning is managing the Markov Decision Process (MDP) by learning the optimal value function, which is achieved through iterative value updates and the Bellman equation. The Q function gauges the expected cumulative reward obtained from taking a specific action a and adhering to the current policy. As the algorithm iterates, the Q function evolves to better approximate the optimal value function, consequently enhancing the agent’s decision-making ability over time.

The Q-learning algorithm updates the

Q function using a value iteration update. This update considers factors such as the likelihood of transitioning from state

to state

upon selecting action

a, denoted as

, the reward gained from this transition, represented by

, and the ongoing value function of state

. The value iteration update in Q-learning is articulated as follows:

where

corresponds to the learning rate,

symbolizes the reward accrued by the agent for its action in the state, and

represents the discount factor.

We propose an approach that leverages historical interactions among devices at the IoT layer to determine a trust index (TI) value for each device in an SC. Harmful behaviors can be preempted by assessing the TI values for IoT devices. Our approach operates on the assumption that anomalous behavior diminishes a device’s reputation, while regular behavior enhances it.

The TI assigned to a device functions as an indicator of TI dependability, with a higher TI reflecting greater trustworthiness. A new device entering the system initiates with an initial TI that adapts based on its interactions with other devices. The average reputation is gauged using the formula:

where

signifies the reputation of

k observed by

j.

The TI of each device is formulated according to the kind of behavior it displays:

This assessment calculates the dependability of a recommendation given by device k to device j by evaluating the deviation from the mean recommendation value.

Devices manifesting abnormal behavior are penalized by decreasing their reputation score, yielding:

where

is a predefined parameter encompassed within the range of [0,1]. The weighting is contextually determined by network security, with

representing the frequency of device connections, and

representing the total number of device interactions over a specified time frame.

7.2. Evaluation

We present the numerical results derived from our simulations in the following. We begin with discussing the simulation settings and configuration. Subsequently, we assessed the proposed DRL model using selected evaluation metrics. Finally, we analyzed the impact of detrimental behavior on the system’s performance.

For simulation purposes, we used NSL-KDD as a benchmark dataset, which consists of samples for Denial of Service (DoS), Probe, User to Root (U2R), and Remote to Local (R2L) attacks [

30]. We employed a min-max normalization technique to normalize the training and testing sets within the range of

. Four-layer DRL architecture was employed utilizing relu activation. The input layer, located at the top, consists of neurons that capture environmental variables. The last layer, which corresponds to the value of Q for each category of the simulated attacks, represents the output. The two middle layers function as covert layers that aid in training.

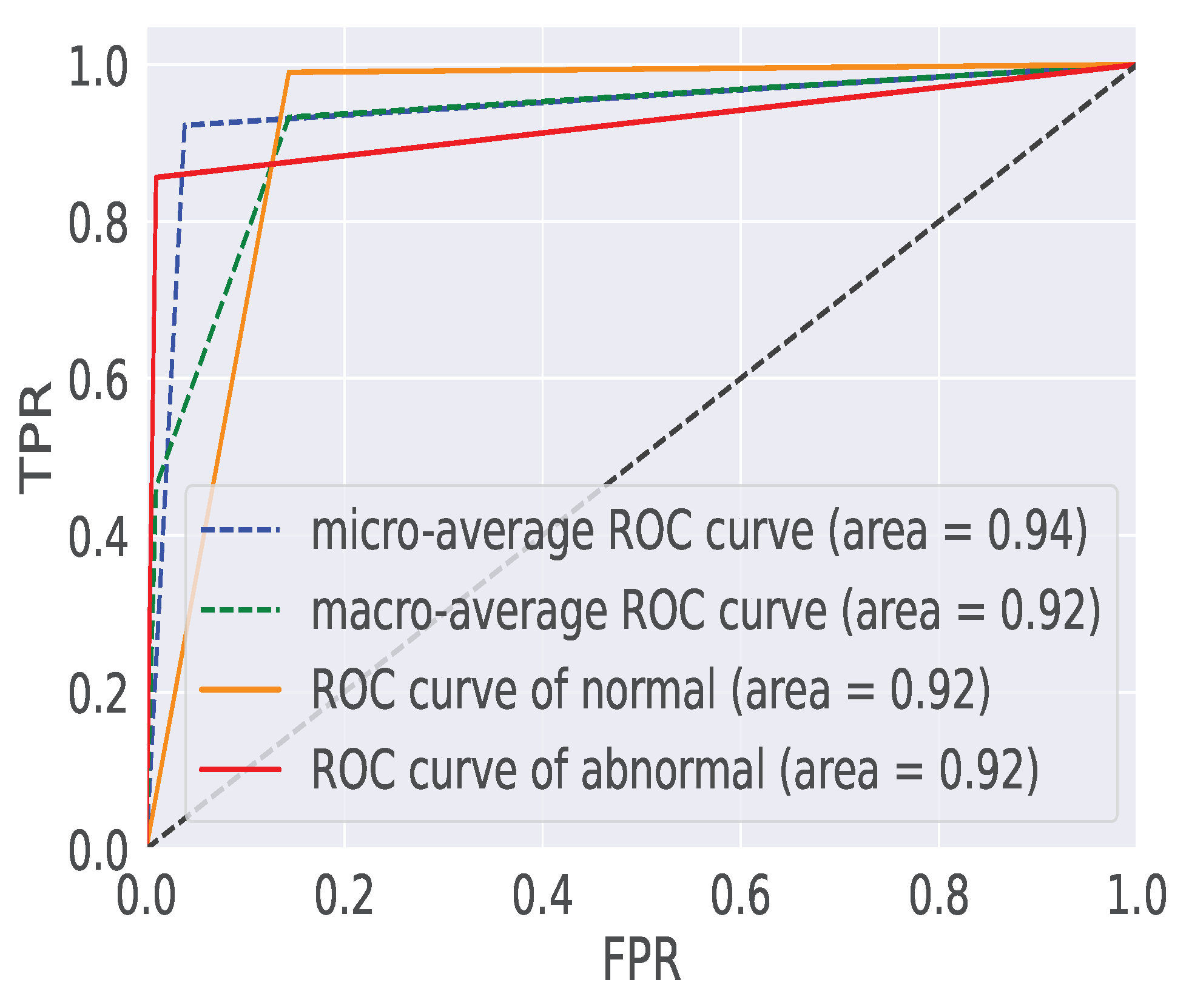

We assessed the model’s performance by employing two key evaluation metrics: the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Precision-Recall (PR) curve. The ROC curve visually depicts the trade-off between the True Positive Rate (TPR), also known as sensitivity, and the False Positive Rate (FPR). The PR curve illustrates the balance between TPR and the Positive Predictive Value.

We established two crucial performance metrics: Detection Accuracy (A) and F1-Score (F1), which measure correct attack detection and prediction, and the harmonic mean of precision and recall, respectively. These metrics can be defined as follows:

Where, TP represents successfully detected attacks, FN denotes attacks falsely identified as reliable device behaviors, FP signifies reliable device behaviors erroneously flagged as attacks, and TN indicates correctly recognized and predicted reliable device behaviors.

Figure 8 presents the ROC curves generated from the performance of our DQL model on the NSL-KDDTest+ dataset, showcasing results for training durations of 50 epochs. The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) is a critical metric, where a higher value indicates the DQL model’s remarkable ability to discriminate between reliable and unreliable device behaviors. Specifically, our DQL model achieves an accuracy of 0.88% after 50 training epochs. These results highlight the model’s capacity to progressively enhance its discriminatory performance over the course of training.

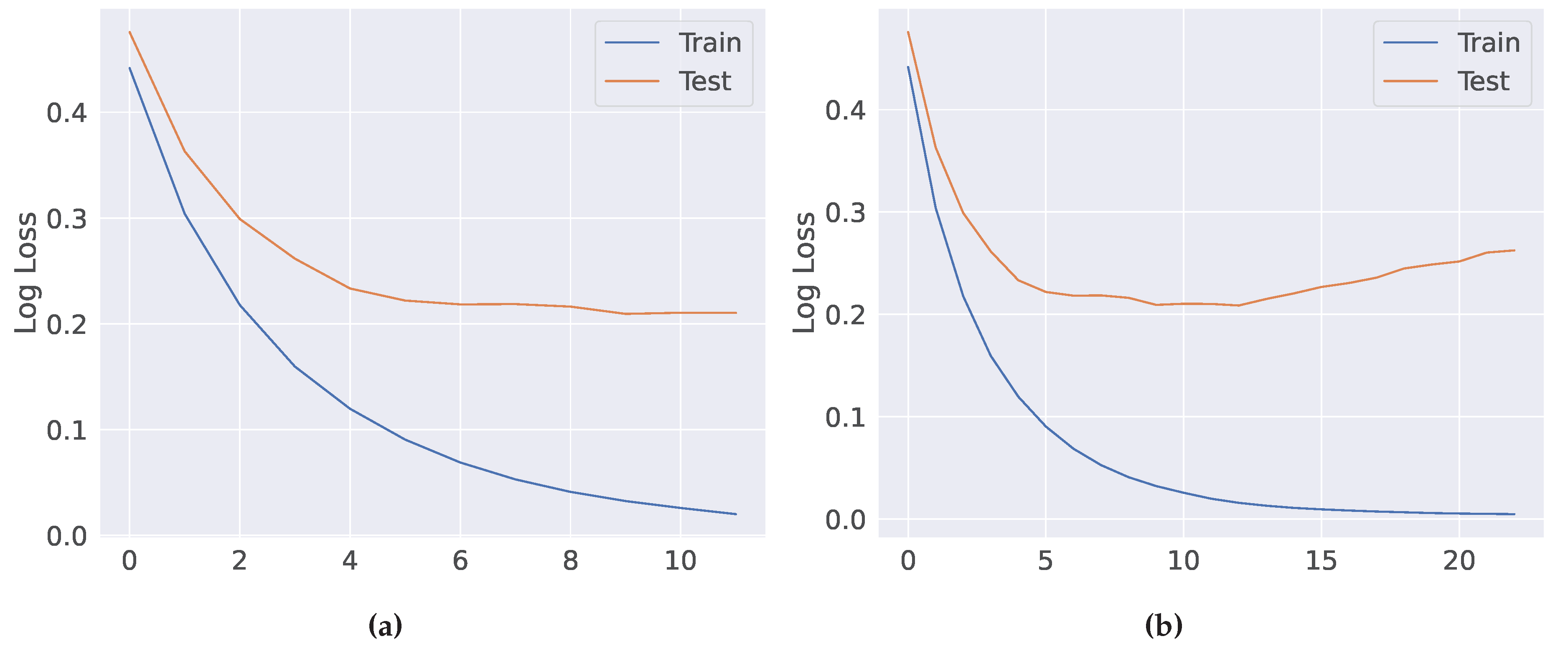

Figure 9a,b depicts the progression of model loss for our Deep Q-Learning (DQL) model across two different training scenarios: 25 epochs and 50 epochs. A clear pattern emerges, exhibiting a consistent reduction in loss values as the training epochs advance. Eventually, these losses converge to nearly zero by the end of the 50-epoch training phase. This trend serves as a compelling indicator of the model’s ability to efficiently learn from its environment and continually improve its performance.

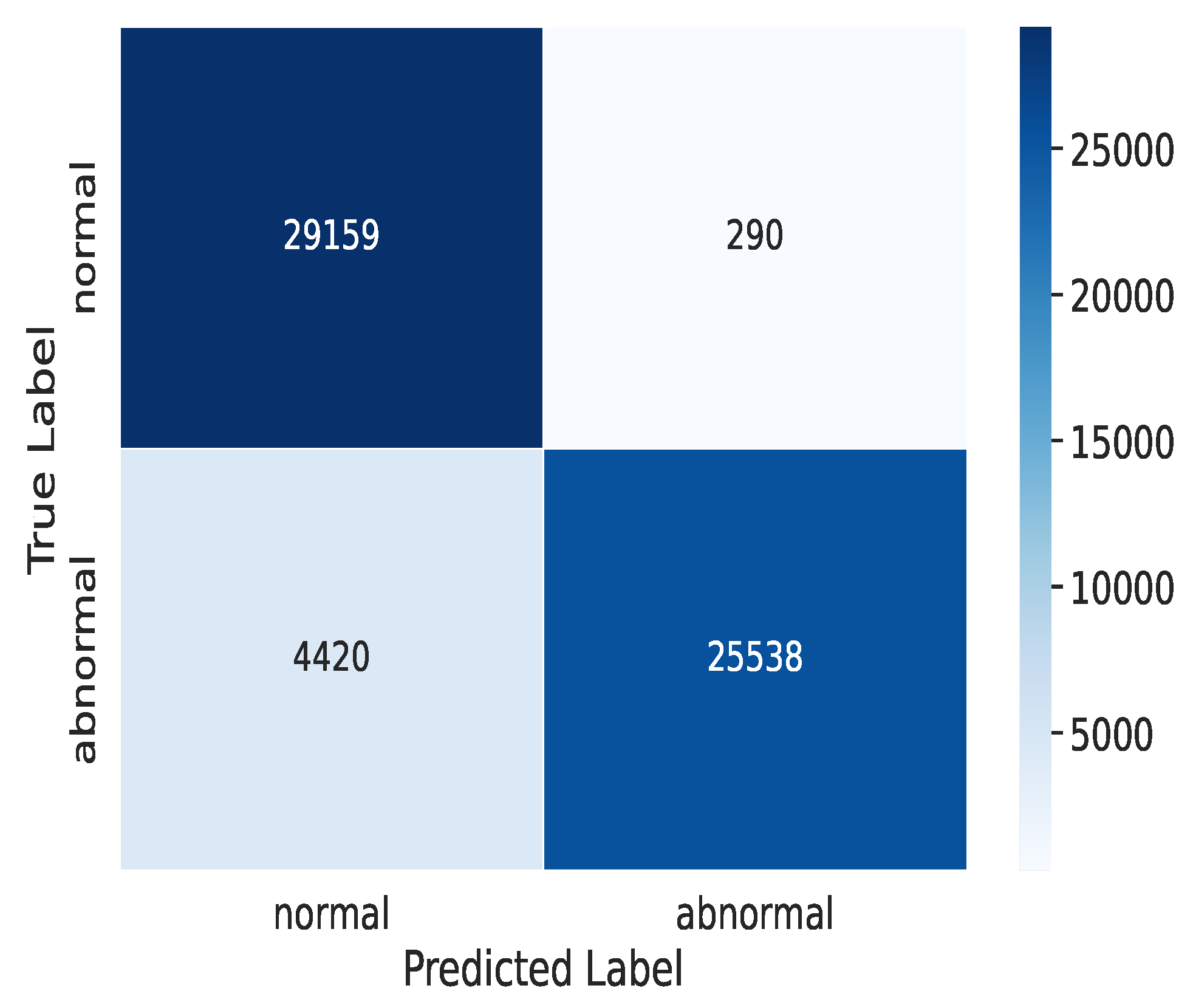

Figure 10 presents the confusion matrix derived from the performance of our DQL model after 50 training epochs. This matrix offers valuable insights into the model’s effectiveness in accurately distinguishing between intrusions and normal device behaviors. Following 50 training iterations, our DQL model achieved a commendable attack detection rate of 25,538, effectively identifying instances of unauthorized access. Additionally, it demonstrated a high precision of 29,159 in correctly categorizing regular and reliable device behaviors; however, there were 290 instances where the model incorrectly classified reliable device behaviors as attacks and 4,420 instances where it erroneously labeled attacks as reliable device behaviors. These results provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance and areas where potential improvements may be needed.

Figure 8.

ROC curves on for 50 epochs.

Figure 8.

ROC curves on for 50 epochs.

Figure 9.

Model loss on for: (a) 25 epochs; and (b) 50 epochs.

Figure 9.

Model loss on for: (a) 25 epochs; and (b) 50 epochs.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrices on for 50 epochs.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrices on for 50 epochs.

8. Conclusion

Security has become challenging with the rapid growth of SC systems and integration with Big Data and IoT technologies, especially with the increased trust among system participants. An effective approach can be adopting the ZT concept which requires strict authentication and access control requirements and embedding DRL-IDS for proactive attack detection. We proposed a BC-DRLzSC hybrid security framework which integrates BC and DRL designed to operate in a ZT environment. BC records a history of transactions communicated between system entities in a shared, distributed, and tamper-resistant ledger to track product movement along the SC.

Our proposed framework integrates BC with smart contracts to securely identify and register entities and manage access to system resources. DRL is employed to develop an IDS for a proactive attack detection which continuously monitors the incoming traffic from authenticated nodes within the network. The network takes appropriate actions to mitigate the associated risks when malicious behavior is detected. DRL, integrated with ZT, strengthens system security against any vulnerabilities or malicious acts; however, issues such as performance, computational overhead, storage constraints, and appropriate BC platform selection remain unresolved research issues.

References

- Ohm, M.; Plate, H.; Sykosch, A.; Meier, M. Backstabber’s knife collection: A review of open source software supply chain attacks. Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment: 17th Int. Conf., DIMVA 2020, Lisbon, Portugal, June 24–26, 2020, Proc. 17. Springer, 2020, pp. 23–43.

- Ismail, S.; Reza, H. Security Challenges of Blockchain-Based Supply Chain Systems. 2022 IEEE 13th Annual Ubiquitous Comput., Electron. & Mobile Commun. Conf. (UEMCON), 2022, pp. 1–6.

- Melnyk, S.A.; Schoenherr, T.; Speier-Pero, C.; Peters, C.; Chang, J.F.; Friday, D. New challenges in supply chain management: cybersecurity across the supply chain. Int. J. of Production Research 2022, 60, 162–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, E.; Lei, M.; Song, C. Zero trust in edge computing environment: A blockchain based practical scheme. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 2022, 19, 4196–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, Z.A.; Sarkis, J. The zero trust supply chain: Managing supply chain risk in the absence of trust. International Journal of Production Research 2021, 59, 3430–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Reza, H.; Salameh, K.; Kashani Zadeh, H.; Vasefi, F. Toward an Intelligent Blockchain IoT-Enabled Fish Supply Chain: A Review and Conceptual Framework. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, C.; Olenberger, C.; Schweizer, A.; Völter, F.; Eymann, T. Never trust, always verify: A multivocal literature review on current knowledge and research gaps of zero-trust. Computers and Security 2021, 110, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M. Beyond Zero Trust: Trust Is a Vulnerability. Computer 2020, 53, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M.; Hossain, A.; Laila, F.; Taher, K.A.; Islam, M.N. Towards developing a secure medical image sharing system based on zero trust principles and blockchain technology. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, S.; Dawoud, D.; Reza, H. Towards A Lightweight Identity Management and Secure Authentication for IoT Using Blockchain. 2022 IEEE World AI IoT Congress (AIIoT), 2022, pp. 77–83.

- Moudoud, H.; Cherkaoui, S.; Khoukhi, L. An IoT blockchain architecture using oracles and smart contracts: the use-case of a food supply chain. 2019 IEEE 30th Annual Int. Symp. on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Commun. (PIMRC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–6.

- Tsolakis, N.; Niedenzu, D.; Simonetto, M.; Dora, M.; Kumar, M. Supply network design to address United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: A case study of blockchain implementation in Thai fish industry. Journal of Business Research 2021, 131, 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, R.; Chamoun, R.K.; Sokhn, M. The power of a blockchain-based supply chain. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2019, 135, 582–592. [Google Scholar]

- Abeyratne, S.A.; Monfared, R.P. Blockchain ready manufacturing supply chain using distributed ledger. Int. J. of Research in Eng. and Technol. 2016, 05, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W.; Foth, M.; Cao, S.; Natanelov, V. Garbage in garbage out: The precarious link between IoT and blockchain in food supply chains. J. of Ind. Inf. Integr 2022, 25, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Choi, T.M.; Somani, S.; Butala, R. Blockchain technology in supply chain operations: Applications, challenges and research opportunities. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2020, 142, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoukas, V.; Gkogkidis, A.; Kampa, A.; Spathoulas, G.; Kakarountas, A. Enhancing Food Supply Chain Security through the Use of Blockchain and TinyML. Information 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Farsi, S.; Rathore, M.M.; Bakiras, S. Security of Blockchain-Based Supply Chain Management Systems: Challenges and Opportunities. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, K.; She, Y.; Zhu, L.; Choo, K.K.R.; Wan, Z. A blockchain-based access control scheme for zero trust cross-organizational data sharing. ACM Trans. on Internet Technol. (TOIT) 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François-Lavet, V.; Henderson, P.; Islam, R.; Bellemare, M.G.; Pineau, J.; others. An introduction to deep reinforcement learning. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 2018, 11, 219–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobi, M.N.; Krishnan, R.; Huang, Y.; Shakarami, M.; Sandhu, R. Toward deep learning based access control. Proc. of the Twelfth ACM Conf. on Data and Appl. Security and Privacy, 2022, pp. 143–154.

- Jin, Q.; Wang, L. Zero-Trust Based Distributed Collaborative Dynamic Access Control Scheme with Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. EAI Endorsed Trans. on Security and Safety 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegenbekov, Z.; Jackson, I. Adaptive supply chain: Demand–supply synchronization using deep reinforcement learning. Algorithms 2021, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachaïchi, Y.; Chemingui, Y.; Affes, M. A policy gradient based reinforcement learning method for supply chain management. 2020 4th Int. Conf. on Advanced Systems and Emergent Technologies (IC_ASET). IEEE, 2020, pp. 135–140.

- Alves, J.C.; Mateus, G.R. Deep reinforcement learning and optimization approach for multi-echelon supply chain with uncertain demands. Int. Conf. on Computational Logistics. Springer, 2020, pp. 584–599.

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Z.; Su, H. Deep reinforcement learning approach for capacitated supply chain optimization under demand uncertainty. 2019 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 3512–3517.

- Powell, W.; Cao, S.; Foth, M.; He, S.; Turner-Morris, C.; Li, M. Revisiting Trust in Supply Chains: How Does Blockchain Redefine Trust? In Blockchain Driven Supply Chains and Enterprise Information Systems; Bouras, A., Khalil, I., Aouni, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gonczol, P.; Katsikouli, P.; Herskind, L.; Dragoni, N. Blockchain Implementations and Use Cases for Supply Chains-A Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 11856–11871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Dedeoglu, V.; Kanhere, S.S.; Jurdak, R. Trustchain: Trust management in blockchain and iot supported supply chains. 2019 IEEE Int. Conf. on Blockchain (Blockchain). IEEE, 2019, pp. 184–193.

- Moudoud, H.; Cherkaoui, S. Empowering Security and Trust in 5G and Beyond: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Open J. of the Commun. Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Existing Work for DRL Applications in SC Management.

Table 1.

Existing Work for DRL Applications in SC Management.

| Year |

Ref. |

Directions |

| |

|

DRL |

BC |

ZT |

Application |

Insights |

| 2021 |

[23] |

PPO |

|

|

Inbound &Outbound Flow |

PPO based DRL agent that can synchronize inbound and outbound flows in a SC and Support business continuity in a stochastic and non-stationary environment. |

| 2020 |

[22] |

MADDPG |

|

✓ |

Traffic Allocation |

MADDPG based optimize traffic allocation policy for adaptive and automatic collaborative management, considering network security, network environment, and user requirements. |

| 2020 |

[24] |

PPO |

|

|

Order Placement |

Development Of a reinforcement learning agent for optimal order placement and inventory replenishment in SC management. |

| 2020 |

[25] |

PPO2 |

|

|

Operating Cost |

A DRL agent is employed to find an optimal policy for operating the entire SC and minimizing total operating costs . |

| 2019 |

[26] |

PPO2 |

|

|

Inventory Management |

A DRL method that aims to learn optimal policies that can adapt to changing demand conditions and make effective decisions regarding inventory management and capacity utilization in the SC. |

| 2022 |

[17] |

TinyML |

✓ |

|

Security |

Proposed a model to ensure the integrity Of collected data and self-sovereign identity approach to minimize single points of failure. Additionally, it incorporates TinyML's nascent technology to monitor devices to mitigate malicious behavior from actors in the SC. |

| 2022 |

[19] |

|

✓ |

✓ |

Cross Organizational Data Sharing |

An RBAC model using a multi-signature protocol and smart contract methods to facilitate lightweight data sharing among different organizations |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).