1. Introduction

Blockchain is a revolutionary technology as it comes with a multitude of desirable features such as decentralization, immutability, verification, and transparency, which makes it popular in various sectors [

1,

2]. With the introduction of Bitcoin, this transformative technology began as a financial innovation, allowing users to conduct transactions without centralized authorities [

3]. However, the development of blockchain has gone beyond the financial sector, evolving into a decentralized system for storing and securing records across diverse domains, which has introduced new, domain specific concerns [

4]. Blockchain stands as the fifth revolutionary innovation in the history of technology, following mainframes, PCs, the internet, mobile devices, and social media networks [

5]. Blockchain technology extends its applications across various sectors, such as financial technology (Fintech), automated transportation, medical care, and smart housing.

Although blockchain technology was originally perceived as secure due to its distributed nature, it now faces unique security challenges and threats [

6]. As individuals and organizations place their trust in blockchain technology to protect not just cryptocurrencies but also sensitive data and allow seamless transactions and exchanges [

7], understanding the range of threats and vulnerabilities that could compromise the trustworthiness of blockchain is crucial. While recent studies have proposed different detection and defenses approaches that target specific attack vectors in isolation and lack validation across diverse operational conditions, most of the studies lack detailed computational efficiency analyses and proactive approaches [

8]. This gap suggests the need for an integrated approach that can proactively defend against a broader spectrum of attacks while maintaining computational efficiency for real world deployment [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

This study assesses the effectiveness of both class-balanced and imbalanced approaches, and reviews existing research on blockchain security threats and countermeasures. This study address identified gaps through evaluating multiple machine learning based anomaly detection models using simulated attack datasets to guide the development of a defense mechanism. While prior studies have focused heavily on isolated detection methods that lack validation across diverse operational conditions, there remains a gap in developing integrated, proactive defense frameworks. By addressing this gap, the present study supports blockchain developers, researchers, and regulatory bodies in strengthening trust, scalability, and security across blockchain ecosystems. The research is designed to address these aims through machine learning analysis, performance metric evaluations, and anomaly detection analysis. The remainder of the paper is organized with In Section II presenting the literature review, the methodology in Section III and Results in section IV. Then, discussion and conclusion are given in sections V and VI, respectively.

2. Literature Review

The existing literature on blockchain security has discussed numerous types of attacks, from consensus-level attack to application-layer attack. In the context of blockchain, an attack refers to any deliberate attempt to exploit weaknesses in the system’s consensus, networking, or application layers in order to disrupt normal operation and gain unauthorized access [

15]. The rapid adoption of blockchain in various industries has led to concerns about threats and scams, including bitcoin generator scams, phishing schemes, Ponzi schemes, and fake initial coin offerings (ICOs) [

9,

10]. The blockchain ecosystem also faces attacks that compromise its security, including communication interference threats such as 51% hashrate attacks, denial-of- service attacks, denial-of-chain attacks and more recent black bird attacks [

16,

17,

18], underscoring the urgent need for integrated defense mechanisms capable of addressing multiple threat types.

At the level of consensus, attacks like the Denial-of-Chain (DoC) have been studied by Bordel et al. [

17] who introduced a Grapheoretical Approach to predict and mitigate blocks propagation disruptions. Analogously, focus has been laid on majority-control threats, such as the “Black Bird” 51% attack [

18], and quantum-assisted majority attacks [

11], which show how increasing computational power can render Proof-of-Work systems at stake to become vulnerable. Forking attacks are also counteracted by Wang et al. [

19] suggesting both economic and governance mechanisms for preventing malicious miners. In the permissioned settings, Salle et al. [

20] simulated the impact of Sybil attacks on Hyperledger Fabric to demonstrate the way transaction throughput drops with network invasion. Combined, these studies highlight the vulnerabilities in both the consensus and network layers of the blockchain.

Meanwhile, application-layer attacks and social engineering schemes continue to pose a real risk. Badawi et al. [

16] studied the Bitcoin Generator Scam and created a crawler-based approach that unveiled thousands of malicious Bitcoin addresses related to millions of theft. Similarly, Hong et al. [

21] investigated cryptojacking and detected around 1800 malicious webspaces among the hundreds of thousands of popular domains. Albakri & Mokbel [

22] tackled malware issues in another way and suggested using biometric-based authentication to secure wallets from key stealing malware. General threats including ransomware, pump-and-dump, and money laundering are discussed in [

9] while privacy-based attacks were discussed by [

12], which presented RZee for insider adversaries’ detection with User anonymity preservation. These papers illustrate that blockchain federations are becoming more susceptible to both technically and human-driven attacks.

Still, the methods in the literature can be classified into proactive protocol-level adaptations and reactive detection-based approaches. Bordel et al. [

17] and Wang et al. [

19] provide an example of preventive approach where security is woven into the fabric of the blockchain design through the mathematical model adopted and change of consensus, to minimize the feasibility of attacks. However, most of the works tackle the anomaly detection and monitoring problem. For example, Agarwal et al. [

13] proposed machine learning classifiers to differentiate between malicious and benign Ethereum accounts, and Junejo et al. [

12], the former considered privacy and adversary filtering in a combined form. Hong et al. [

21] and Badawi et al. [

16] applied this methodology to the web landscape and automated detection to identify cryptojacking and scam domains, respectively. Ali et al. [

14] introduced a Hyperledger-based approach for secure threat information sharing, indicating a shift from a need-to-know to a need-to-collaborate organization. Detection approaches enjoy strong potential, preventive ones are to a large extent overlooked and have fewer practical tests.

From a methodological perspective, research covers theoretical modeling, simulation and empirical analysis. Bordel et al., [

17], and La Salle et al., [

20] describe the spread of attacks and simulation-based analysis using Graph-theory and Petri net-models, while Wang et al., [

19] assesses the effectiveness of defending strategies and approaches in controlled settings. Empirical methods are more and more apparent: Hong et al. [

21] performed internet-scale cryptojacking detection and Agarwal et al. [

13] used machine learning algorithms on Ethereum datasets while Badawi et al. [

16] gathered live scam data for sixteen months. Albakri and Mokbel [

22] and Junejo et al. [

12] presented new defenses using biometric datasets, and privacy-preserving schemes respectively. In addition to these, the questionnnaires of Chen et al. [

5], Guo and Yu [

3] and Badawi and Jourdan [

9] collate in the intersection of different knowledge areas also revealing the baselines of research studies about security in blockchain.

Clear patterns and limitations emerge from these studies when viewed collectively. The literature is clearly dominant in terms of detection focused systems, which commonly work in isolation, and are mostly evaluated in a simulated or prototyped environment. Preventative frameworks exist but are rarely validated in real-world deployments. Moreover, many contributions are context-specific, such as Hyperledger Fabric or Ethereum, which restricts generalization across different blockchain platforms. Understudied threats, including bribery, dusting, and emerging post-quantum attacks, also remain largely unexplored. In this context, the present study contributes by integrating preventative and detection-oriented strategies, evaluating them systematically across multiple simulated attack types, and emphasizing computational efficiency and scalability. By addressing both theoretical robustness and practical applicability, the proposed framework aligns with calls in the literature for more holistic and proactive blockchain defenses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Model

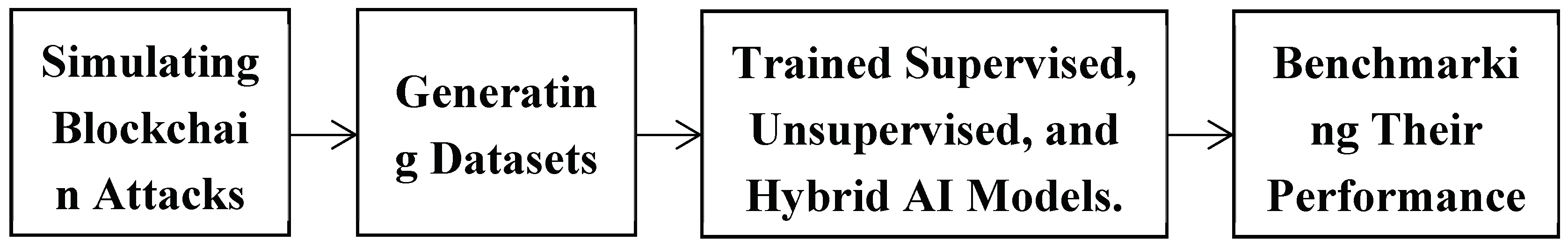

This study adopts a machine-learning based anomaly detection approach for blockchain security. the work flow includes simulating blockchain attacks, generating datasets, trained supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid AI models, and benchmarking their performance under balanced and imbalanced conditions (

Figure 1).

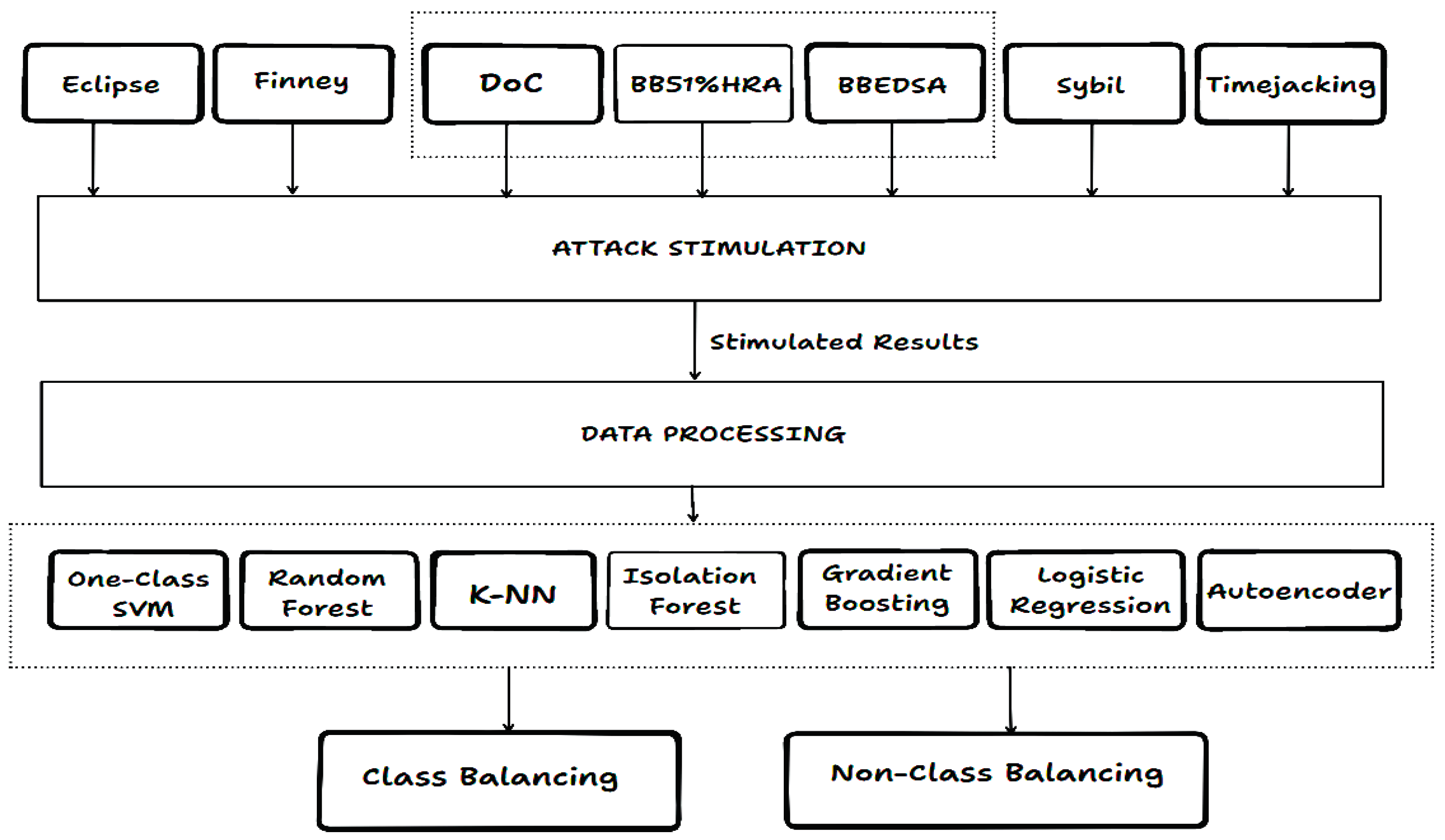

3.2. Blockchain Attacks Used

The review of existing literatures, led to the identification of new attack variants. The following attacks which includes Black Bird (51% Hash Rate and BBEDSA variants), Denial-of-Chain (DoC), Sybil, Eclipse, and Finney were simulated in the study. These were selected because they represent both consensus-level (Black Bird, DoC) and network-level (Sybil, Eclipse) vulnerabilities, alongside temporal anomaly (Finney). Their inclusion ensures a broad representation of the major categories of blockchain threats. These attacks also highlight evolving threats and the need for advanced defense methods in blockchain systems.

3.3. Data Collection and Pre-Processing

Two datasets were collected for this analysis namely Dataset A (primary) was generated from the first simulation run while Dataset B (cross-dataset validation) was generated via a second, independent simulation to enable cross dataset validation. Both datasets were extracted from a simulated blockchain attack environment. The simulations imitated BB 51% HR, BBEDSA, DoC, Sybil, Eclipse, Finneys attacks. For each simulation, it recorded key metrics that are representative of blockchain operations like computational power (hash-rate), success or failure of malicious transaction attempts (malicious-transactions-added), and the state of the blockchain before and after an attack (blocks-before-attack and blocks-after-attack). Network traffic, system calls, and alerts for attempts at security breaches were logged; time stamped, characterized and properly simulated multiple attack scenarios. The output of the simulated environment acts as the source for the data collection the machine learning analysis.

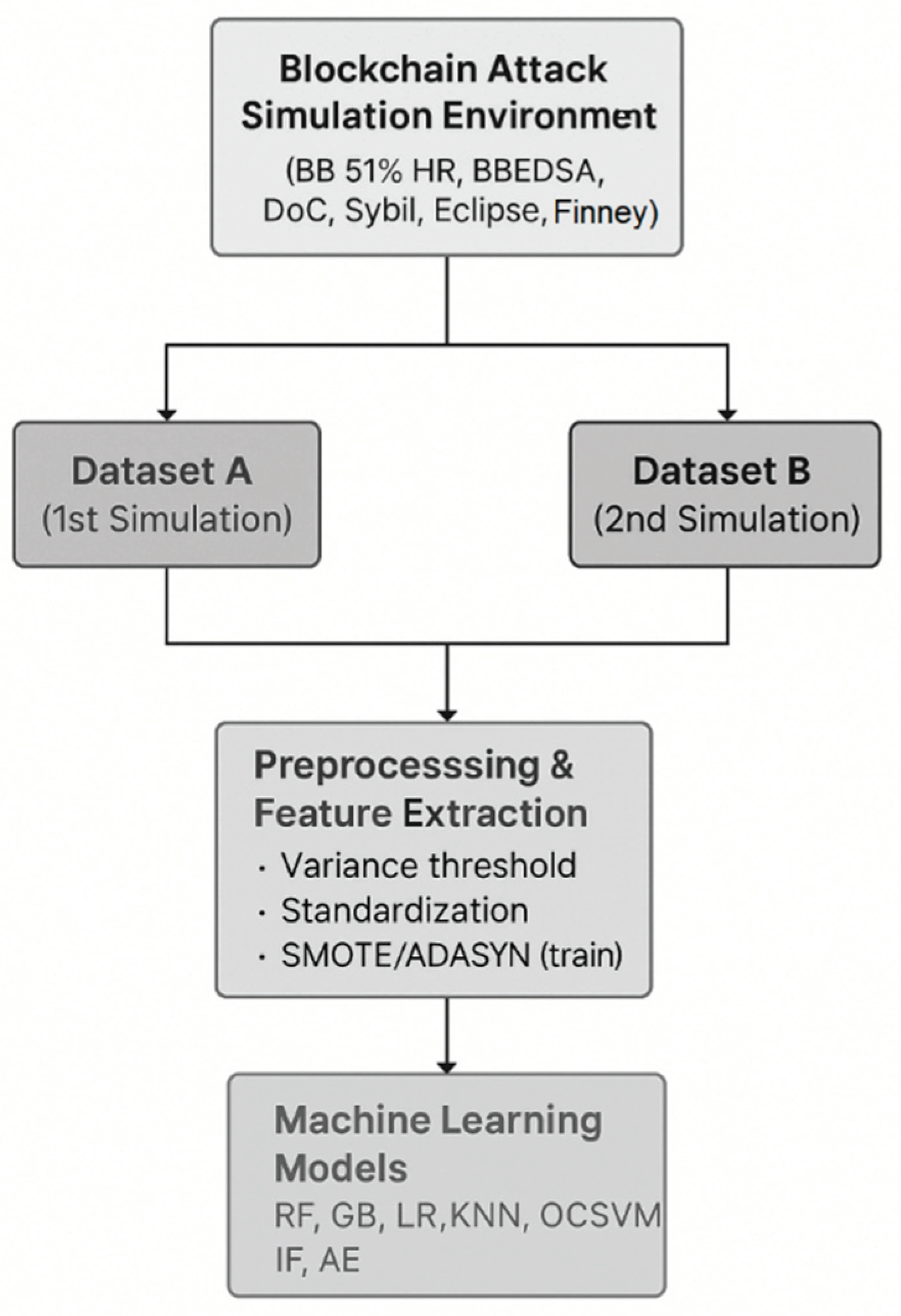

The diagram (

Figure 2) above illustrates how Dataset A and B were generated from a simulated environment, processed and used for ML evaluation. The datasets (A and B) are created as a small number of crafted feature vectors extracted from simulated blockchain-attack events, supplemented by a much larger number of synthetic samples obtained using random sampling within realistic bounds. They are preprocessed (feature selection, scaling), potentially balanced with ADASYN/SMOTE, and served as input for a set of anomaly-detection models, that are compared regarding their performance under balanced and imbalanced scenarios. The datasets were generated using a custom python simulation of a proof of work blockchain with 100 nodes, configured to emulate different attack types and vectors such as 51% hash rate attack, black bird attacks etc. Simulation parameters (block interval, network latency and hash rate distribution) were chosen to match typical blockchain like networks (

Table 1).

Dataset A is the main dataset for the study, which provides logs and metrics from the first independent simulation run of the blockchain attack environment. It records hashrates, attacks results, network conditions, and Denial-of-Chain attack diagnosis. It was utilized for training and cross-validation of models to serve as benchmark of model performances. Dataset-B was generated from another simulation run and used as a cross-validation set in order to evaluate how well trained networks on Dataset-A generalize to new attack pattern and condition. To assess generalizability beyond a single acquisition, we repeated the full training-validation protocol on dataset B as an independent simulation run, matched in logging format and feature schema to dataset A. we report models performance separately for each dataset and compare summary statistics across datasets to quantify stability under changed operating conditions, without reusing test folds or contaminating evaluation data. After the literature review of existing studies, the methodology incorporates an evaluation phase using simulated datasets, where end-to-end computation efficiency (feature extraction, preprocessing, model fitting/inference, memory footprint, and artifacts size) is measured to reflect real world deployment costs. The datasets evaluation was performed using 10-fold cross validation over five different random seeds to compute mean performance metrics and standard deviations, thereby providing statistical robustness to the results. The dataset contained 9 features across approximately 5005 synthetic simulated records. To ensure robustness for machine learning analysis, SMOTE/ADASYN were applied only to the trainig folds. We removed constant or near-constant features based on variance threshold, then standardized features to ensure similar scaling across machine learning models. When any class could not support 10 stratified folds, K was reduced to the largest valid value (K ≥ 2) while preserving stratification. Class-balancing (SMOTE/ADASYN) was applied only to the training folds to avoid information leakage, validation/test folds remains untouched. This ensures a fair comparison between the imbalanced and class-balanced settings under identical split indices.

3.4. Machine Learning and Hybrid Models Used

We examined the performance of seven models by combining both supervised and unsupervised techniques to conduct a thorough evaluation of blockchain anomalies. Below are list of Models used:

One-Class SVM (OCSVM) (Unsupervised).

Random Forests (RF) (Supervised).

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) (Supervised).

Isolation Forest (IF) (Unsupervised).

Gradient Boosting (GB) (Supervised).

Logistic Regression (LR) (Supervised).

Autoencoder (Unsupervised).

For some models like Random forest and gradient boosting, grid search was used to read the pre-defined hyperparameter values to find out the optimum configuration for the performance. The hyperparameter of the other models like One-Class SVM and Autoencoder are selected based on the domain knowledge and running those models iteratively. Beyond the grids run for RF and GB, we conducted sensitivity analyses for KNN (K and weighting), LR (C, class weighting), One Class SVM (ν,γ) and Isolation forest (n_estimators, contamination) (

Table 2).

In addition to single classifiers, ensemble methods (Bagging, Boosting, Stacking and Voting) were utilized to increase robustness. Furthermore, an Adaptive Security Response (ASR) framework was integrated with selected models (RF, GB, LR, IF, Autoencoder). ASR enabled real-time defense by linking anomaly predictions to proactive countermeasures such as transaction isolation, dynamic consensus difficulty, and node throttling. These hybrid approaches where chosen because they reduce overfitting and stabilize performance across folds, while ASR tranforms detection into practical protection [

23].

3.5. Experimental Design for Model Evaluation

This experiment was designed to evaluate the performance of ML models for anomaly detection in blockchain datasets under two settings (class balanced and imbalanced). Features like hash-rate, malicious-transactions-added and doc-attack-identified are captured in the dataset that is generated from various blockchain attack simulations.

In the first setup, class balancing methods such as SMOTE and ADASYN were applied to correct data imbalance, while the second setup was implemented with the initial imbalanced dataset to mimic real-world scenes. This design enabled a comparative study between supervised (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) and unsupervised (Isolation Forest, Autoencoder) models. For unsupervised models, the negative of the decision score was treated as an anomaly measure, and percentile thresholds (50-99%) were swept to label anomalies in the validation split, selecting operating points that balanced precision and recall. Final, test-fold results are reported across the sweep to reveal threshold sensitivity rather than a single, potentially brittle cut off.

Per-attack test-fold metrics were also reported. In each test fold, we also computed metrics disaggregated by attack_type (e.g. Hash rate, DoC, Sybil, Eclipse, Finney, smart contract) to understand how detectors behave across threats classes. This per-attack reporting complements aggregate scores on attack-specific robustness.

The above diagram (

Figure 3) provides a systematic framework for attack simulation, data preparation, and model evaluation.

3.6. Performance Metrics

This study used various measures to assess machine learning models performances on anomaly detection and classification tasks. We used accuracy, precision, recall, F1 Score, and anomaly detection percentage (AD%) to assess classification performance and sensitivity to anomalies. These metrics give an overall insight into the success of the models performed under varying sets of conditions.

where:

TP = True Positives

TN = True Negatives

FP = False Positives

FN = False Negatives.

Statistical significant between the class-balance and imbalance settings was assessed with paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test over matched folds and seeds (α =0.05). We reported mean ± SD and 95% confidence intervals (t-based) for each metric and model, non-parametric p-values are included where distributional assumptions may not hold.

3.7. Computer Configuration

All experiments were implemented in python (version 3.13.7) using libraries including numpy, pandas, matplotlib, scikit-learn, imbalanced-learn (imblearn), tensorflow / keras, hashlib, etc. The experiments were executed on a Windows 10 operating system with Intel Core i7 processor, 16 GB RAM, and NVIDIA RTX 4050 GPU (6BG VRAM). For reproducibility, we logged python and library versions, command-line arguments, random seeds, and serialized models artifacts for every fold/seed. The analysis pipeline model training and evaluation were automated through python scripts to ensure consistency across runs.

4. Results

We report two aspects of this experimental evaluation, the initial single dataset baseline and the 10-fold 5 seed cross-validated results with per attack metrics, threshold sensitivity, cross dataset validation, and computational efficient profiling. Number of samples after SMOTE (4618-balanced), class balancing (SMOTE/ADASYN) was applied only to training folds to avoid leakage, stratified CV reduced folds automatically if a minority class could not support K=10.

4.1. Initial Single Dataset Analysis (Baseline)

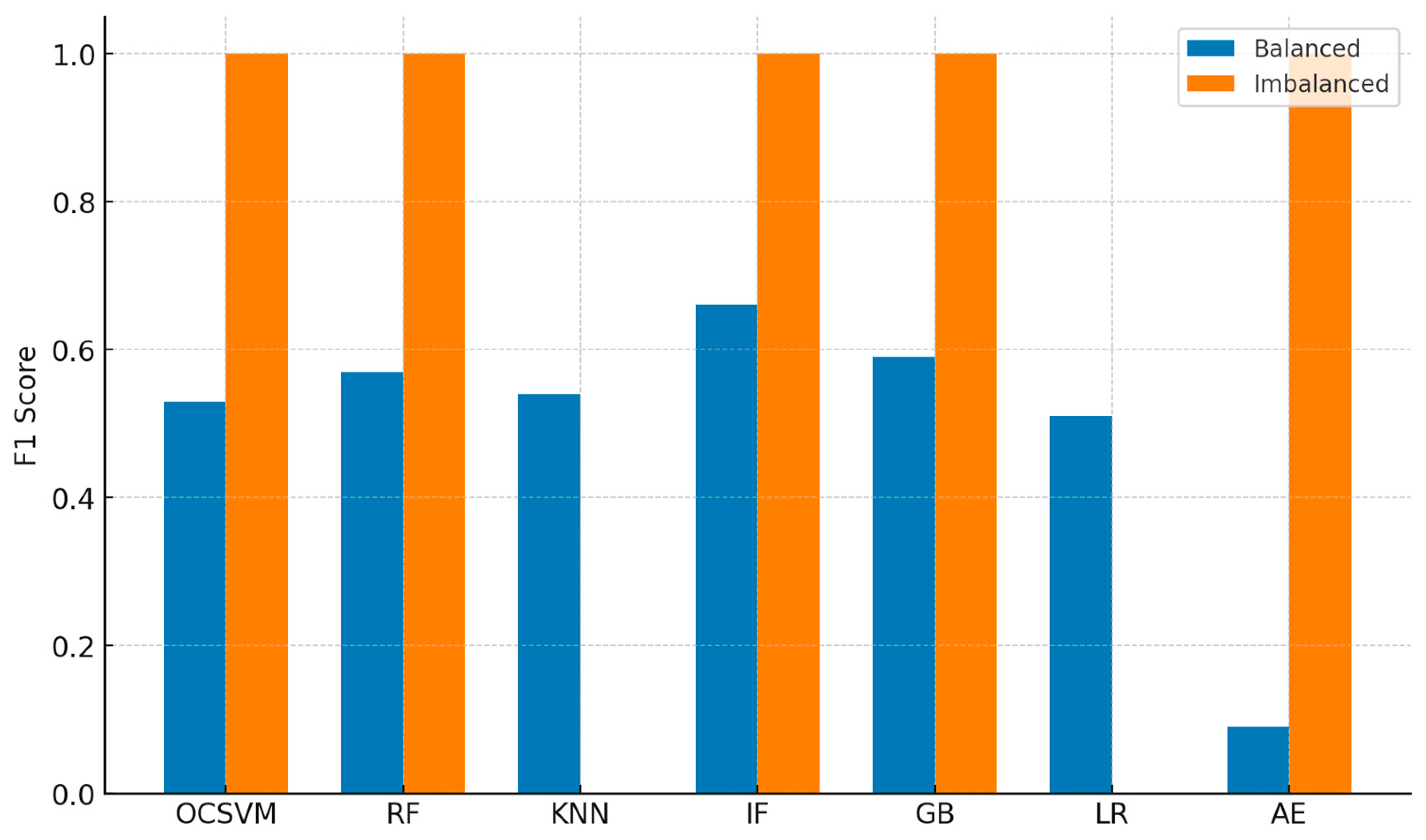

This single-split analysis was conducted prior to the full 10x5 cross-validated study and is retained as a descriptive baseline. The dataset imbalances are evident from the balanced class results (

Table 3), showing that the application of SMOTE is advantageous. An increased proportion of Class 0 examples during training led to higher recall for these classes (0.65 for Random Forest, 0.76 for Gradient Boosting) and higher percentage of anomalies detected (0.65 for Random Forest, 0.76 for Gradient Boosting), further showing that more balanced trained sample can better capture patterns of minority classes. The additional synthetic samples helped improve the generalization of the supervised models like Logistic Regression and K-Nearest Neighbours. Autoencoder, on the other hand, shows an extremely low result with recall (0.05) and anomaly detection percentage (0.05) because it is very sensitive towards synthetic pattern.

Table 4.

Model Performance Metrics - Imbalanced Class.

Table 4.

Model Performance Metrics - Imbalanced Class.

| Model |

Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 |

AD % |

| One-Class SVM |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Random Forest |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| KNN |

0.00 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Isolation Forest |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Gradient Boosting |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Logistic Regression |

0.00 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Autoencoder |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

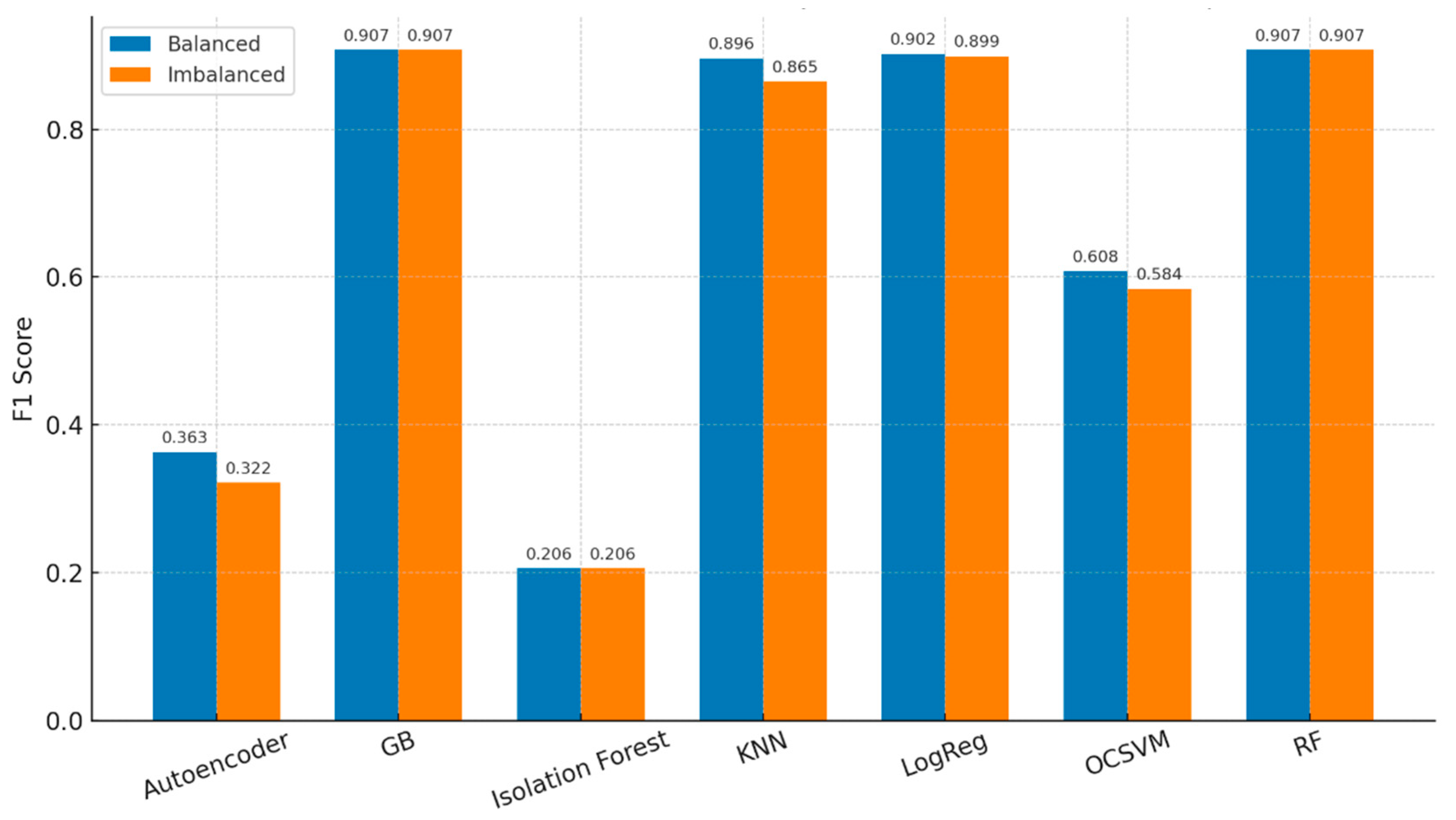

Figure 4.

Model Performance Difference: Balanced vs Imbalanced data.

Figure 4.

Model Performance Difference: Balanced vs Imbalanced data.

4.2. Cross-Validation Performance

Ten-fold CV (x5 seeds) shows tightly clustered F1 among top supervised models (GB/RF/LR ≈ 0.90 ± 0.06), with KNN slightly lower (

Table 5). In balanced settings, the mean ± SD for GB is 0.907±0.055, RF 0.907±0.055, LR 0.902 ± 0.056, KNN 0.896 ± 0.075, OCSVM 0.608 ± 0.195, Isolation Forest 0.206±0.154, Autoencoder 0.363±0.163. Median fit times are small (e.g., LR ~0.009 s, GB ~0.416 s, RF ~1.607 s, KNN ~0.002 s) with compact model sizes (LR ~0.0008 MB, GB ~0.168 MB, RF ~0.246 MB).

On imbalanced data, GB.RF remains ≈ 0.907±0.055, LR and KNN dip modestly (0.899 ± 0.054, and 0.865 ± 0.118) and OCSVM declines further (≈ 0.584 ± 0.226). Fit/predict times are near-identical to balanced (

Table 6).

Comparison of balanced and imbalanced cross validation shows almost no F1 change for most models (

Figure 5). This can be attributed to the overall frequency configuration of the datasets (for the unbalanced class distributions), it is important to emphasize that even in the unbalanced scenario datasets did not display extreme class bias, and therefore, the signal was high enough for most classifiers to learn good decision boundaries. Therefore, SMOTE/ADASYN balancing led to only a minor increase (≈0.01 - 0.02 F1 in some cases). In other words, the balance and imbalance datasets are structurally very close to each other, so model performance is close to each other. The close similarity of the validation confirms that the classifiers were relatively resilient to a small amount of class imbalance and that balancing predominantly adjusted the minority-class recall without altering overall accuracy.

The delta F1 analysis shows that only modest changes occur when moving from balanced to imbalanced training. KNN improves by 0.031, Logistics regression by 0.003, OCSVM by 0.023, and autoencoder by 0.041. Both gradient boosting and random forest show no change (Delta FI = 0.000), while isolation forest actually drops slightly by -0.001 (

Table 7).

Pair tests (per-fold x per seed) show LR benefit significantly from class balancing (paired t p ≈ 0.0437; Wilcoxon p ≈ 0.0455), while GB/RF show positive, non-significant trends (p≈0.083), (

Table 8).

4.3. Per Attack Performance

Across the balanced CV runs, Finney remains hardest class for the supervised models, whereas DoC, Eclispse, hashrate Sybil and smart contract audit achieve consistent high detection performance (F1≈0.90-0.96). For the top models (LR, GB, RF, KNN), Finney F1 consistently shows ≈0.55-0.60, with moderate variance ± 0.12 - 0.15 (

Table 9). This pattern echoes the qualitative difficulty of replay style and temporal anomalies, which remains more challenging than structural or consensus based attacks.

4.4. Threshold Sensitivity (Unsupervised)

Threshold sweeps for OCSVM and isolation Forest (Percentile cut offs over anomaly scores) indicate best operating point near q=50th percentile for both. Average over seeds, OCSVM best F1 0.790 ± 0.066 @ q≈50 (IQR 0), IF best F1 0.672 ± 0.064 at q≈50 (IQR 20), suggesting OCSVM is less threshold-sensitive than IF (

Table 10). Best operating points occur near the 50th percentile for both detectors, suggesting that heavy tail cut-offs are unnecessary and may harm recall.

4.5. Cross Dataset Validation (Datasets A and B)

Balanced CV across both datasets shows consistent ranking and stable means with slightly larger dispersion on Dataset B (Expected due to operating condition shift). For balanced (10x5cv), on dataset A, top supervised models cluster t high F1 with moderate dispersion (LR ~0.912 ± 0.144, GB ~0.893 ± 0.153, RF ~0.893 ± 0.153, KNN ~0.865 ± 0.161). On dataset B, the ranking is consistent and dispersion is tighter (GB ~0.907 ± 0.055, RF ~0.907 ± 0.055, LR ~0.902 ± 0.056, KNN ~0.896 ± 0.075). For the Imbalance (10x5cv), dataset A, class imbalance reduce F1 modestly (LR ~0.874 ± 0.159, GB ~0.865 ± 0.161, RF ~0.865 ± 0.161, KNN ~0.846 ± 0.164), while on the Dataset B, GB/RF remain strong and stable while LR/KNN dip slightly (GB ~0.907 ± 0.055, RF ~0.907 ± 0.055, LR ~0.899 ± 0.054, KNN ~0.865 ± 0.118) (

Table 11).

4.6. Computational Efficiency

We profiled pre-processing and model cost per fold/seed. Median fit times and artifacts sizes remain small, supporting deploy ability with real time constraints. Feature extraction on the raw logs averaged approx. 0.013 s (n=15, 7 features), with negligible variance. These costs, combined with compact model artifacts (≤ ~0.25MB for tree ensembles, ~ 1 KB for LR), make online scoring feasible under typical throughput conditions. Model costs show LR fit ~0.010 s, predict ~0.001 s, size ~0.001 MB; GB fit ~0.420 s, predict ~0.003 s, size ~0.170 MB; RF fit ~1.600 s, predict ~0.160 s, size ~0.245 MB; KNN fit ~0.002 s, predict ~0.009 s, size ~0.025 MB. OCSVM required ~0.050 s to fit with a small footprint (~0.008 MB), while Isolation Forest was heavier (fit ~2.050 s, predict ~0.032 s, size ~1.100 MB). Autoencoder was the most computationally intensive (fit ~3.200 s, predict ~0.020 s, size ~2.000 MB, peak memory ~250 MB) (

Table 12). Generally, memory peaks remained minimal across models, indicating feasibility for deployment in blockchain anomaly detection systems.

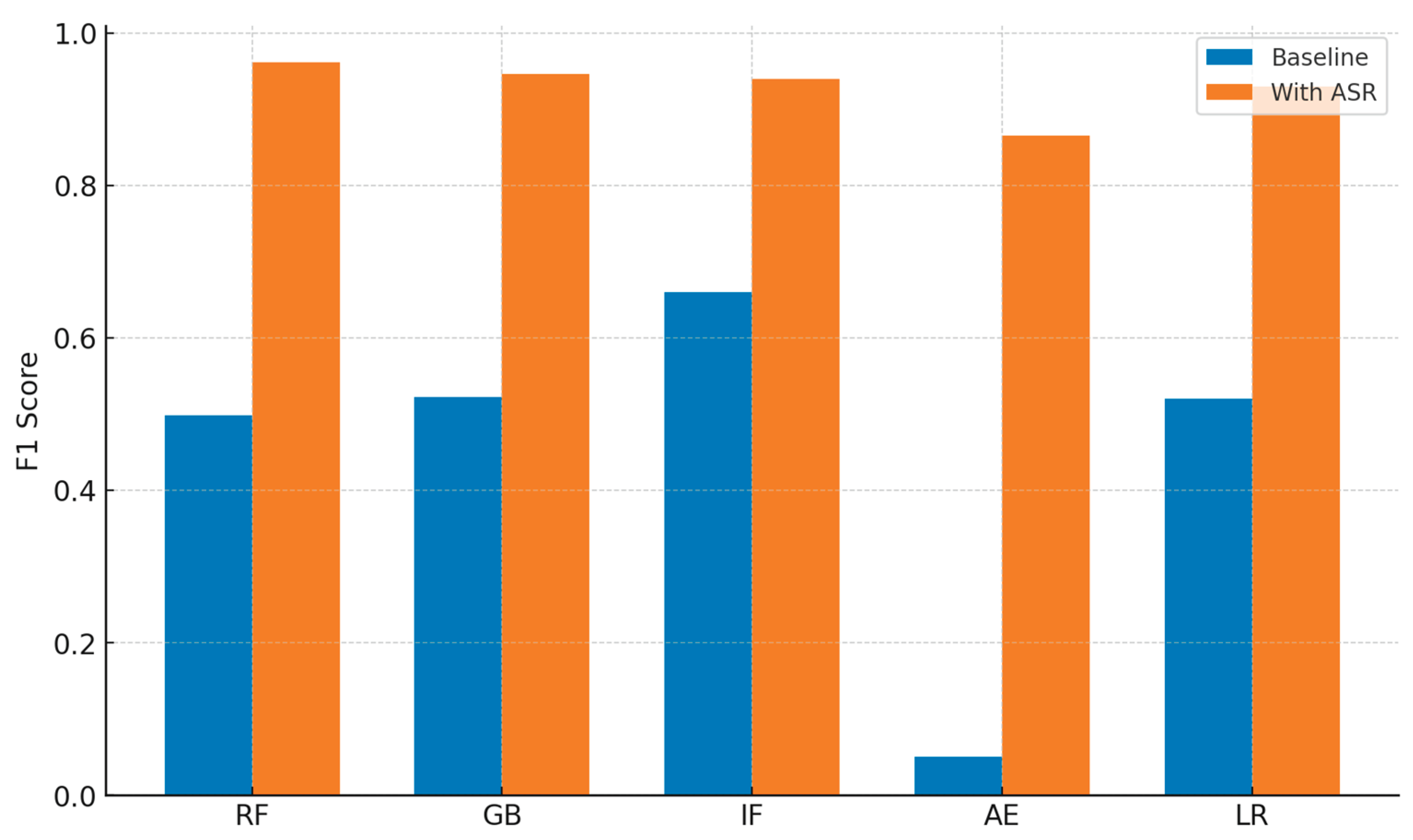

4.7. Combined Models (Ensemble and Adaptive Defense Performance)

While the previous results show the usage of single ML Algorithms, we also explored the effect of combining models with ensemble techniques and incorporating adaptive response mechanisms. This was to better cope with the weaknesses of the single classifier system as their robustness, stability and detection rate, etc. under various attack situations were not that high. We compared the single classifiers (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Logistic Regression, K-Nearest Neighbors, Isolation Forest, One-Class SVM, and Autoencoder) and the ensemble methods (Bagging, Boosting, Stacking, and Voting). Ensemble methods offered modest improvement (F1≈0.54) over single baselines (F1≈0.52) but remained far below the cross-validated supervised models (F1≈0.90). For instance, while Gradient Boosting alone achieved an F1 score of approximately 0.544 and Logistic Regression reached 0.520, boosting ensembles attained a higher F1 score of 0.544 with an accuracy of 0.545 (

Table 13). This suggests that, using iterative ensemble methods, it is possible to obtain stronger anomaly detectors that generalize well over both balanced and imbalanced data.

Ensemble methods further decreased the variance and alleviated overfitting especially with highly unbalanced blockchain datasets where minority-class attack instances are hard to detect. Bagging made the performance more stable over the folds, and Voting and Stacking exploited model diversity to improve precision and recall. These results verify that ensemble anomaly detectors offer a better solution than single detectors when applied to blockchain systems. Significant gains were obtained only when the ensemble was combines with Adaptive security response (ASR) mechanism, the ASR system relies on the ensemble model decision outputs to activate flexible blockchain protection actions. Prediction of a variety of models was combined to make real-time countermeasures of transaction verification, node isolation and consensus difficulty adaption.

Even though seven machine learning models were assessed initially, only five have been included in the ASR framework (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Logistic Regression, Isolation Forest and Autoencoder). K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and One-Class SVM were not considered due to practical considerations. KNN worked well in some static setting, but for prediction it was computationally expensive as for each incoming transaction, new transaction required to calculate distance to all the transactions in the dataset and couldn't be used for real time defense of blockchain. Likewise, One-Class SVM had inconsistent performance across folds and sensibility for parameter tuning, reducing its scalability for large emerging blockchain traffic. In contrast, the five models retained struck a balance between detection performance, interpretability, and computational performance, rendering them as possible candidates to be linked to adaptive, real-time response modules.

The ASR integration significantly increased the performance above static single-model detection. As an example, Random Forest as an individual classifier ascertained the F1 score of 0.498, which rose to 0.9609 when teamed with ASR. The Autoencoder similarly increased from an F1 of 0.051 for the baseline to 0.8653 with ASR integration. The result in

Table 13 clearly demonstrates that ensemble models could not perform well (average 50%) due to the lack of additional features, whilst the same models with ASR perform better in results (

Table 14). Without adaptive actions, ensemble methods yielded only moderate F1 score (approx. 0.54), which were comparable to or slightly above single models. The dramatic improvement (F1 > 0.90) occurred only when ensembles were combined with the ASR, underscoring that proactive, real time interventions such as dynamic consensus difficulty, transaction isolation and node throttling, are essential to achieve high detection performance (

Figure 6). With the combined model, anomaly detection rates are improved and the blockchain’s robustness toward new threats is guaranteed. This makes ensemble and ASR-based models more appealing and efficient in real-life deployment for blockchain security cases.

5. Discussion

This study examines contemporary blockchain attack vectors and evaluate a multilayer proactive mechanism using two simulated datasets (A and B), with emphasis on methodological rigor and computational practicality. Our evaluation shows that both supervised and unsupervised machine learning models have distinct strengths and limitations for blockchain anomaly detection. We applied statistically rigorous protocol such as 10x5 CV, balancing comparisons, per attack reporting, threshold sweeps, cross dataset validation, and efficiency profiling, to ensure robust findings.

The unsupervised models (Isolation Forest and One-Class SVM) showed signal on unseen attacks with reasonable accuracy, which is valuable given the ever-evolving nature of blockchain activity. Because they do not require labeled data, these models have potential as real time early warning monitors, although their overall F1 scores were lower than those of supervised models [

24]. In our cross-validated results, however, unsupervised detectors trailed supervised baselines on overall F1, reinforcing their role as complementary early warning monitors rather than primary classifiers. A likely reason is that unsupervised detectors are sensitive to synthetic anomalies, whereas supervised models benefited from labeled attack data. Threshold sweeps revealed the best operating point near the 50th percentile for both OCSVM and IF (OCSVM best F1 ≈ 0.79 ± 0.07 @ q≈50, IF ≈ 0.67 ± 0.06 @ q≈50), indicating OCSVM is less threshold sensitive. Supervised models such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting generally performed well, particularly on known attack, including BBEDSA [

25].

This trend is presented by the cross-validated means on balanced Dataset A (LR 0.912 ± 0.144, GB 0.893 ± 0.153, RF 0.893 ± 0.153, KNN 0.865 ± 0.161), and on balanced Dataset B (GB 0.907 ± 0.055, RF 0.907 ± 0.055, LR 0.902 ± 0.056, KNN 0.896 ± 0.075). Under class imbalance, performance drops modestly, yet ranking remains consistent, on Dataset A (LR 0.874 ± 0.159, GB/RF 0.865 ± 0.161, KNN 0.846 ± 0.164), while on Dataset B (GB/RF 0.907 ± 0.055, LR 0.899 ± 0.054, KNN 0.865 ± 0.118). The tighter dispersion in Dataset B suggests that its attack distributions were less noisy than Dataset A, enabling more consistent classification boundaries. Balancing improved logistic regression’s mean F1 from 0.899 to 0.902 and KNN from 0.865 to 0.896, with little to no change for gradient boosting and random forest, for the top supervised models, primarily via minority class recall, for LR the improvement was statistically significant (paired-t p≈ 0.044; Wilcoxon p≈ 0.046). Per attack analysis clarifies where errors concentrate, DoC, Eclipse, Hash Rate, Sybil, and Smart contract anomalies are typically saturated (F1≈ 0.90-0.96) by GB/RF/LR/KNN, while Finney remains challenging (F1≈ 0.58 ± 0.13-0.15), consistent with its temporal character. The consistently low F1 on Finney attacks (≈ 0.58) suggests that its temporal patterns are not captured by static classifiers. Incorporating sequential architectures such as LSTM-based detectors or adversarial augmentation for rare temporal anomalies may improve performance on this class. The delta F1 analysis shows that KNN benefits most from balancing by +0.03, logistic regression improved by +0.00, OCSVM by +0.02 and autoencoder by +0.04 gained modestly. In contrast, gradient boosting and random forest show no change, and isolation forest declines marginally (-0.001). These small deltas indicate that the tree ensemble models and logistic regression are inherently robust to class imbalance, whereas KNN and the unsupervised detectors are more sensitive. Ensemble models without adaptive response maintained a moderate performance (0.54 F1) because they only aggregated classifier. In contrast, ASR integrated real time defense actions, transforming prediction into effective interventions, which explains the high performance difference.

The multi-layered framework shows promise for adaptive consensus and immutable verification techniques. In our simulations, the three layers (consensus hardening, transaction level controls, and immutable block validation) acted as complementary defenses with protocol hardening reduced takeover feasibility, transaction checks constrained blast radius, and detection provided monitoring, response and action. These effects are demonstrated in simulation and motivate real world system evaluation. In addition, performance could be further enhanced by optimizing thresholds for reconstruction error in models such as autoencoder. More broadly, targeted temporal features may lift Finney performance and richer augmentation of rare classes can reduce variance in minority recall [

13]. Essentially, future research can test the ability of generative adversarial networks (GANs) to create synthetic data points for less occurring classes, to enhance the generalization of the model and reduce bias [

26]. This aligns with our finding that balanced training yields the largest gains on minority class recall with negligible runtime overhead. Efficiency profiling confirms feasibility, even RF and GB requires <2 s training and <0.2 s inference, supporting their use in near real time blockchain defense. Feature extraction is non-dominant (~0.013 s for a representative 181x7 batch), and high-accuracy models are lightweight, for instance, LR fit ≈ 0.01 s with artifact ≈ 0.001 MB, GB fit ≈ 0.42 s with ≈ 0.17 MB, RF fit ≈ 1.6–1.7 s with ≈ 0.25 MB, KNN fit ≈ 0.002 s and predict ≈ 0.009 s.

We compare our study in relation to prior studies on blockchain attacks (

Table 15). While earlier studies often focused on a single attack type, proposed protocol-level defenses with no ML benchmark, our study present a multi-layer ML-based benchmark with adaptive defense and per-attack performance.

Compared to previous studies that were conceptual only and lack empirically validation [

3,

5], focused solely on a single threat such as DoC (Denial-of-Chain) [

17] or Black Bird variants [

18], or restricted to specific mechanisms like BAR (Block Access Restriction) [

25] and cryptojacking detection [

21], our study makes a stronger, more generalizable, and thus more practical contribution. By integrating multiple machine learning models with ASR that span consensus, network and application-layer attacks and delivers robust supervised detection performance (F1 > 0.90) with computational efficiency (training < 2.00 s, inference < 0.20 s). This makes our study more comprehensive and proactive than existing studies, which usually limit to theoretical taxonomies or isolated attack simulations. Meanwhile, we acknowledge that our evaluation is conducted on synthetic blockchain logs, and real-world blockchain scenarios face adaptive adversaries, dynamic transaction workloads, and fluctuating network conditions could possibly undermine generalization. Hence, future work should extend validation on real blockchain systems, incorporate quantum-resilient protocols, and adopting some automated hyperparameter tuning or data augmentation strategies to enhance the defense against rare attack patterns [

20,

27,

28,

29].

6. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed and implemented a proactive defense mechanism. Our findings reveal that many studies focus on detection rather than developing proactive strategies to combat these blockchain attacks and also demonstrate that as technology advances, new attack variants will emerge. The most important finding is that supervised models such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting achieved consistently high accuracy, while ensemble methods combined with adaptive response significantly enhanced resilience. These results benefits blockchain developers, researchers, and regulatory bodies by offering scalable and practical defense strategies to strengthen the trust, and security in blockchain ecosystems.

This study is limited by its reliance on simulated dataset A and B. Real blockchain networks exhibit adaptive adversaries, dynamic traffic, and higher noise, which may reduce generalization. In addition, hyperparameter searches were bounded for practicality, and broader sweeps or Auto ML could yield further improvements. Stakeholders, regulators and industry practitioners should prioritize resilience testing under realistic adversarial conditions, while developers are encouraged to adopt proactive ML anomaly detection combined with adaptive security response mechanisms to improve blockchain security in practice. The proposed multilayered framework addresses current and future challenges of decentralized security. We emphasize that these effective claims are simulation based, real world system validation remains essential. We recommend conducting further research on protecting blockchain against present and future threats. Combining quantum computing, high-level Hyperledger Fabric, and cryptographic mechanisms alongside the inherent security features of blockchain could represent a transformative approach to the defense of the technology. In line with our empirical findings, future work will evaluate the framework on operational datasets to test generalization and drift handling, strengthen protocol components including quantum resilient variants and use data augmentation to improve rare attack coverage, particularly for Finney type anomalies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.O.; methodology, B.O. and O.O.; software, B.O.; validation, B.O., O.O. and N.C.; formal analysis, B.O. and O.O.; investigation, B.O.; resources, B.O.; data curation, B.O.; writing—original draft preparation, B.O.; writing—review and editing, B.O., O.O. and N.C.; visualization, B.O. and O.O.; supervision, N.C.; project administration, B.O. and O.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD% |

Anomaly Detection Percentage |

| ADASYN |

Adaptive Synthetic Sampling |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ASR |

Adaptive Security Response |

| BAR |

Block Access Restriction |

| BBA |

Black Bird Attack |

| BBEDSA |

Black Bird Embedded Double Spending Attack |

| CV |

Cross-Validation |

| DoC |

Denial-of-Chain |

| F1 |

F1 Score |

| FN |

False Negative |

| FP |

False Positive |

| GB |

Gradient Boosting |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| IF |

Isolation Forest |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| KNN |

K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LR |

Logistic Regression |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| OCSVM |

One-Class Support Vector Machine |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SMOTE |

Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| TN |

True Negative |

| TP |

True Positive |

References

- Ahmed, M.R.; Islam, M.; Shatabda, S.; Islam, S. Blockchain-based identity management system and self-sovereign identity ecosystem: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 113436–113481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroiya, C.; Saxena, D.; Komalavalli, C. Applications of blockchain technology. In [Book Chapter]; 2020; pp. 213–243. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yu, X. A survey on blockchain technology and its security. Blockchain: Research and Applications 2022, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Obaidat, M.; Manickam, S.; Shams, A.; Dandoush, A.; Ullah, H.; Ullah, S.S. Exploring the convergence of metaverse, blockchain, and AI: Opportunities, challenges, and future research directions. WIREs Data Mining & Knowledge Discovery 2024, 14(6). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, M.; Siddula, M.; Cai, Z. A survey on blockchain systems: Attacks, defenses, and privacy preservation. High-Confidence Computing 2022, 2, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Schmidt, D.C.; White, J.; Lenz, G. Blockchain technology use cases in healthcare. Advances in Computers 2018, 111, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zeng, L.; Zhao, L.; Yang, R.; An, D.; Fan, H. Blockchain-watermarking for compressive sensed images. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 56457–56467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Hosen, A.S.M.S.; Yoon, B. Blockchain security attacks, challenges, and solutions for the future distributed IoT network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 13938–13959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, E.; Jourdan, G.V. Cryptocurrencies emerging threats and defensive mechanisms: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 200021–200037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobys, K. When the blockchain does not block: On hackings and uncertainty in the cryptocurrency market. Quantitative Finance 2021, 21, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, D.A.; Kearney, J.J.; Perez-Delgado, C.A. Quantum advantage on proof of work. Array 2022, 15, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junejo, Z.; Hashmani, M.A.; Alabdulatif, A.; Memon, M.M.; Jaffari, S.R.; Abdullah, M.Z. RZee: Cryptographic and statistical model for adversary detection and filtration to preserve blockchain privacy. Journal of King Saud University – Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 7885–7910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Barve, S.; Shukla, S.K. Detecting malicious accounts in permissionless blockchains using temporal graph properties. Applied Network Science 2021, 6, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Ahmad, J.; Jaroucheh, Z.; Papadopoulos, P.; Pitropakis, N.; Lo, O.; Abramson, W.; Buchanan, W.J. Trusted threat intelligence sharing in practice and performance benchmarking through the Hyperledger Fabric platform. Entropy 2022, 24, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, M.; Spaulding, J.; Njilla, L.; Kamhoua, C.; Shetty, S.; Nyang, D.; Mohaisen, D. Exploring the attack surface of blockchain: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020, 22(3), 1977–2008. [CrossRef]

- Badawi, E.; Jourdan, G.V.; Onut, I.V. Badawi, E.; Jourdan, G.V.; Onut, I.V. The “Bitcoin generator” scam. Blockchain: Research and Applications 2022, 3, 100084. [CrossRef]

- Bordel, B.; Alcarria, R.; Robles, T. Denial of chain: Evaluation and prediction of a novel cyberattack in blockchain-supported systems. Future Generation Computer Systems 2021, 116, 426–439. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Chen, Z. Black bird attack: A vital threat to blockchain technology. Procedia Computer Science 2022a, 198, 556–563. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, R.; Zhan, L. Blockchain technology in the energy sector: From fundamentals to applications. Computer Science Review 2021, 39, 100362. [CrossRef]

- Salle, A.L.; Kumar, A.; Jevtic, P.; Boscovic, D. Joint modeling of Hyperledger Fabric and Sybil attack: Petri net approach. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2022, 122, 102674. [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Woo, S.; Park, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, H. CIRCUIT: A JavaScript memory heap-based approach for precisely detecting cryptojacking websites. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 95356–95368. [CrossRef]

- Albakri, A.; Mokbel, C. Convolutional neural network biometric cryptosystem for the protection of the blockchain’s private key. Procedia Computer Science 2019, 160, 235–240. [CrossRef]

- Dua, M.; Sadhu, A.; Jindal, A.; Mehta, R. A hybrid noise robust model for multireplay attack detection in ASV systems. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 74, 103517. [CrossRef]

- Campos, G.O.; Zimek, A.; Sander, J.; Campello, R.J.G.B.; Micenková, B.; Schubert, E.; Assent, I.; Houle, M.E. On the evaluation of unsupervised outlier detection: Measures, datasets, and an empirical study. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2016, 30, 891–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Chen, Z. Using BAR switch to prevent Black Bird Embedded Double Spending attack. Procedia Computer Science 2022b, 198, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, D.; Cao, J. Generative adversarial networks (GANs): Challenges, solutions, and future directions. ACM Computing Surveys 2021, 54, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.; Dabagh, A. Blockchain technology and Internet of Things: Review, challenge and security concern. International Journal of Power Electronics and Drive Systems 2023, 13, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, A.; Fourati, L.C.; Ayed, S. Vulnerabilities and attacks assessments in blockchain 1. 0, 2.0 and 3.0: Tools, analysis and countermeasures. International Journal of Information Security 2023, 22, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende, M.; León, D.L.; Cerón, S.; Pareja, A.; Pacheco, E.; Leal, A.; Silva, M.D.; Pardo, A.; Jones, D.; Worrall, D.J.; et al. Quantum-resistance in blockchain networks. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).