Introduction

Calprotectin, formerly L1 protein, is the main cytosolic protein in neutrophils and monocytes [

1]. Elevated levels of extracellular calprotectin are found in autoimmune diseases [

2,

3], but have also been detected in severe COVID-19, suggesting that neutrophils are involved in inflammation and respiratory exacerbation in COVID-19 [

4]. Calprotectin is a major component of neutrophil extracellular traps (NET), which are usually involved in host defense for the destruction of invading pathogens [

5]. Increased NET levels have been found in hospitalized COVID-19 patients [

6], where they can obstruct capillary circulation [

7]. In severe COVID-19, NET have been considered to be a driver of endothelial damage for the ensuing immunethrombosis [

8,

9]. However, the formation of NET is counteracted by DNase, which is an enzyme that destroys NET by degradation of their DNA content [

10]. In contrast to the previous and current findings in COVID-19 patients, we only detected moderately increased levels of calprotectin among the other parameters (NET, neopterin and syndecan-1) tested in COVID-19 convalescent blood donors in Oslo [

11].

We and others have found that levels of calprotectin and NET are also raised in vaccine-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT) after vaccination with ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 [

12,

13,

14]. Moreover, recently, we reported increased DNase levels in the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccinated individuals as measured by a novel DNase test, which correlated with their previously measured NET values [

15].

Neopterin is an anti-oxidant agent produced by mononuclear phagocytes upon stimulation with IFNγ, which is produced by T cells and NK cells when they are activated by viruses, cancer cells and other pro-inflammatory danger signals [

16]. IFN-related pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are activated by pathogen- (PAMPs) and damage- (DAMPs) associated molecular patterns in the mucosa [

17]. Previously, neopterin has been used as an unspecific screening test for virus infections in Austrian blood banks [

18,

19]. Elevated neopterin levels have also been found during SARS-CoV-2 infection and at higher levels in severe than mild disease [

20].

Complement activation products C5a and sC5b-9 have been shown to increase rapidly in COVID-19 patients [

21,

22,

23,

24] and are predictors for hospitalization of COVID-19 patients in Northern Italy [

25]. Also, a range of other proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and hematological parameters increased during COVID-19 and more so in severely affected patients during the first pandemic wave [

25].

Here, we wanted to investigate whether the proinflammatory parameters, NET, calprotectin, DNase, and neopterin, could discriminate between hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients examined in the same patient cohort from Northern Italy.

Moreover, we examined whether there were correlations between neopterin, calprotectin, and NET levels and those previously measured for proinflammatory cytokines, complement activation products, and hematology parameters in this patient cohort from Northern Italy.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We enrolled and prospectively followed up 76 symptomatic patients for suspected COVID-19 during the outbreak peak between 9th March 2020 and 22nd April 2020. The inclusion criteria were: age >18 years, diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed by a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 in at least one biological sample. Patients suffering from an infectious disease other than SARS-CoV-2, from previous or current autoimmune diseases, and if pregnant were excluded. Further clinical details have been reported previously [

25].

A multidisciplinary team established a six-phenotype classification based on patient features, vital signs, medical history, symptoms, blood test results, and instrumental findings to manage patients presenting to the emergency room (ER) as previously reported [

26,

27]. Patients from the first two clinical phenotypes (phenotype 1 and 2A) were discharged and referred to the preventive medicine and public health department for follow-up. All other patients were hospitalized. The clinical outcome was evaluated after a 4-week follow-up period, and the patients were classified as mild (n.42) or moderate-severe COVID-19 (n.34). Mild cases included patients with phenotypes one and 2A, who during the follow-up had stable disease and were not hospitalized; patients presenting with phenotypes 2B and three at ER admission and not worsening during the follow-up were considered moderate COVID-19. These patients were hospitalized and responded to conventional patients’ O

2 therapy. Phenotypes 4 and 5 at ER admission or patients presenting with milder disease but worsening during the follow-up were considered severe cases. These patients were hospitalized and were admitted to sub-intensive units or the intensive care unit dedicated to COVID-19 patients requiring non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) or intubation.

On the day of admission or the following day, antecubital vein blood samples were collected into EDTA tubes for the measurement of sC5b-9 and C5a and in serum tubes for the measurement of the other parameters and stored at -80C° until testing as previously described [

25]. Since Fragmin is used in treating most hospitalized COVID-19 patients, and this treatment destroys and lowers NET values, reliable NET testing could not be done in these patients [

28,

29]. This also applies to calprotectin, which is contained in NET, and where the S100A9 (MRP-14) dimer part of calprotectin has an affinity for and interacts with heparin [

28]. Therefore, these hospitalized COVID-19 patients were omitted from this study in contrast to the original Northern Italian COVID-19 patient cohort included in the previous paper [

25]. Moreover, DNase levels are reduced/hampered by EDTA, so their levels will be lower in EDTA plasma than in corresponding/parallel serum samples from patients and controls [

15]. However, since the percent reduction of DNase values must be the same in all EDTA samples, this would not affect comparisons of DNase values between groups or correlations with levels of other parameters in the same samples. All patients’ blood samples were collected before starting other treatments to avoid any drug interference with the biological parameters to analyze. All the hospitalized patients with moderate-severe COVID-19 were then treated with tocilizumab and/or glucocorticoids.

The results of the following laboratory parameters were obtained from the patients’ clinical records: fibrin fragment D-dimer, C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, white blood cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, platelets, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and fibrinogen [

25]. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was also calculated.

The study was approved by the Area Vasta Emilia Nord (AVEN) Ethics Committee on 28 July 2020 (protocol number 855/2020/OSS/AUSLRE – COVID-2020- 12371808) and was carried out in conformity with the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and the code of Good Clinical Practice.

Control samples were from healthy Norwegian blood donors at Oslo Blood Bank, sampled in 2015 before the COVID-19 pandemic, except for the controls used for the in-neopterin test, who were healthy healthcare workers sampled in 2020/2021 (during the pandemic).

H3-NET dual hybrid ELISA

The assay was designed to detect complexes containing DNA and leucocyte calprotectin and was performed as previously described [

30].

Calprotectin mixed monoclonal assay

A novel calprotectin ELISA based on a mixture of monoclonal antibodies was established to ensure that all calprotectin in biological materials containing both histone and DNA fragments could be reliably assayed. The monoclonals were selected to react with all chromatography fractions of stool extracts from inflammatory bowel syndrome patients. The mixed monoclonal (MiMo) antibodies were used both for the coating of microwells and preparation of a horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugate [

31].

Competitive DNase ELISA

In brief, a competitive DNase assay was established using chicken antibodies (NABAS, Ås, Norway) as coat and recombinant human DNase (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) that was conjugated to HRP and mixed with a sample to be examined for readout. Readings at 450 nM after the addition of substrate were inversely proportional to the DNase concentration in the sample [

15].

Neopterin

Neopterin was measured using an ELISA kit (DEIA 1640; Creative Diagnostics®) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Complement activation products

The plasma levels of sC5b-9 and C5a were measured using solid-phase assays (MicroVue Complement SC5b-9 Plus EIA kit, MicroVue Complement C5a EIA, Quidel Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described [

23,

24,

25].

Cytokine detection

We performed multi-analyte profiling of 17 soluble mediators in patients’ and controls’ serum samples using the automated microfluidic analyzer ELLA (BioTechne, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [

25]. The following mediators were measured: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12p70, IFNγ, IFNα, VEGF-A, VEGF-B, GM-CSF, IL-2, IL-17A, VEGFR2, BLyS. Intra- and inter-assay CVs were <8%.

Statistics

One-way ANOVA was used to examine differences between several groups, and t-test/Wilcoxon was used to compare two groups. Pearson correlation was applied to examine correlations between levels of different parameters in COVID-19 patients. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Levels of NET, calprotectin, DNase, and neopterin in hospitalized versus non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients

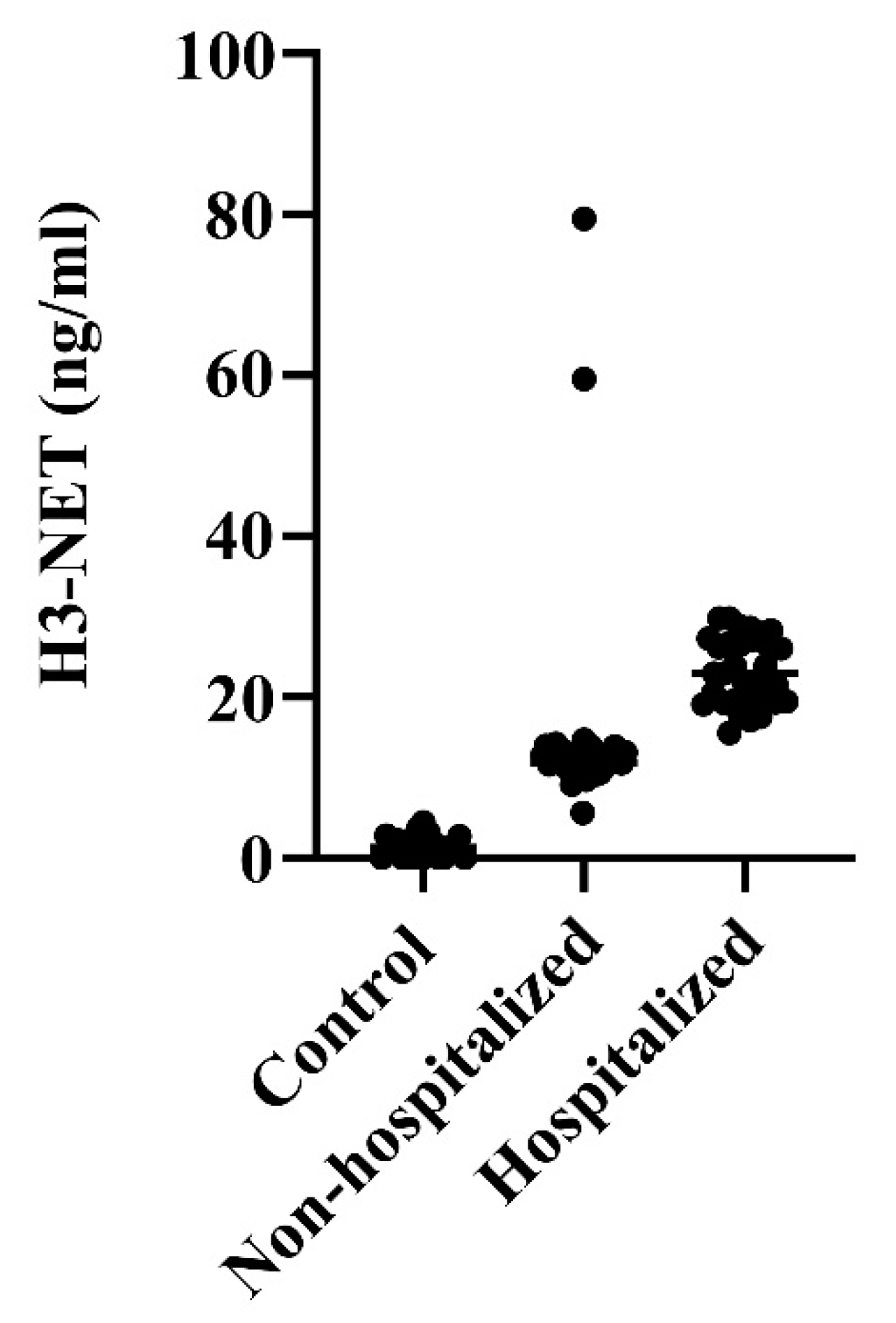

NET levels were 9-fold and 16-fold increased in non-hospitalized and hospitalized COVID-19 patients, respectively, compared with healthy blood donors (ANOVA p<0.0001) (

Figure 1). Thus, NET levels were nearly two-fold higher in patients hospitalized for their more severe COVID-19 than in those not admitted to hospital treatment (p=0.0002).

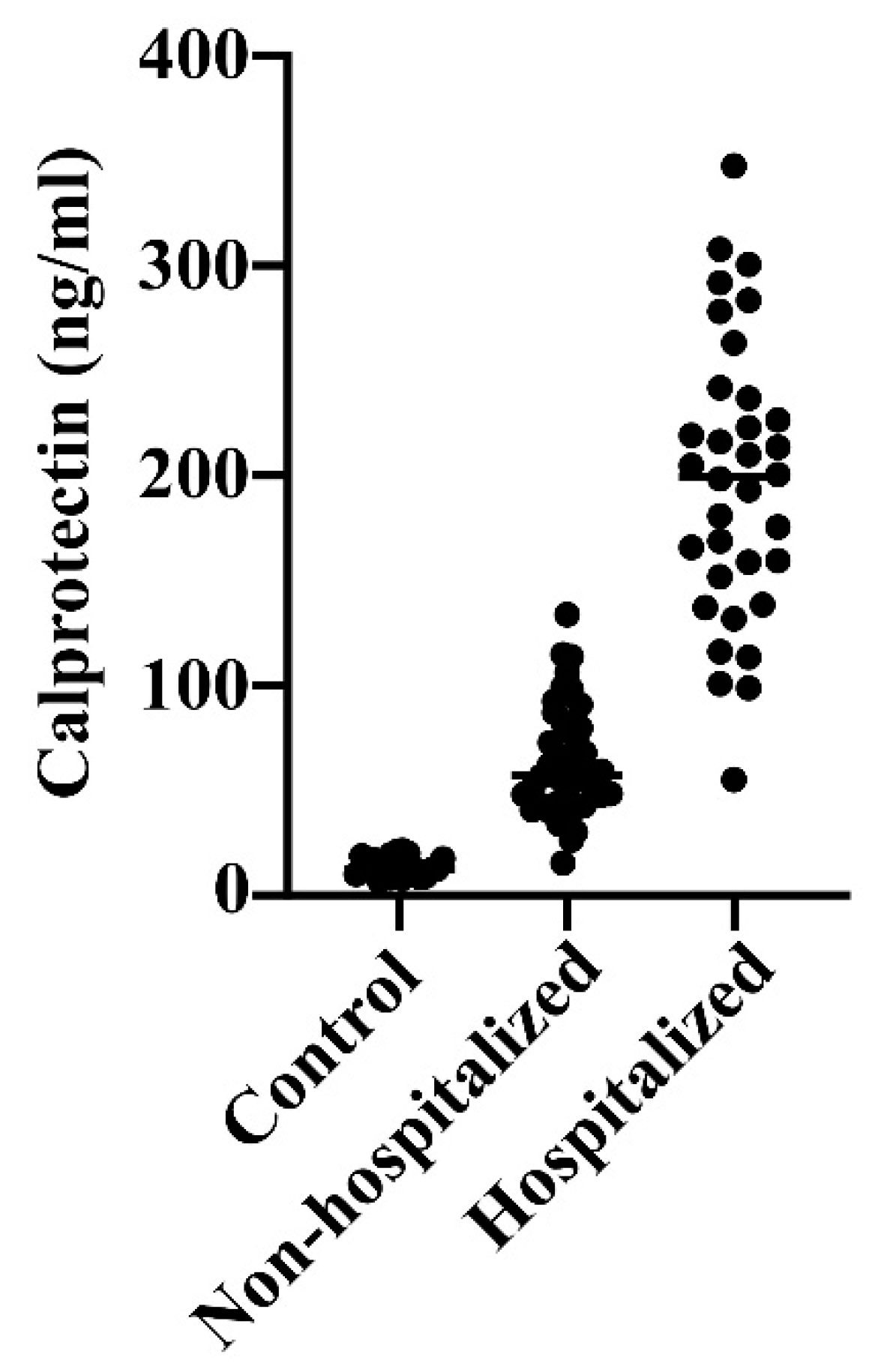

The differences in calprotectin values were even more pronounced; the levels were over 4-fold and 14-fold elevated in non-hospitalized and hospitalized patients relative to blood donors (ANOVA p<0.0001) (

Figure 2). This indicates 3-fold higher calprotectin levels in hospitalized than non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients (p<0.0001).

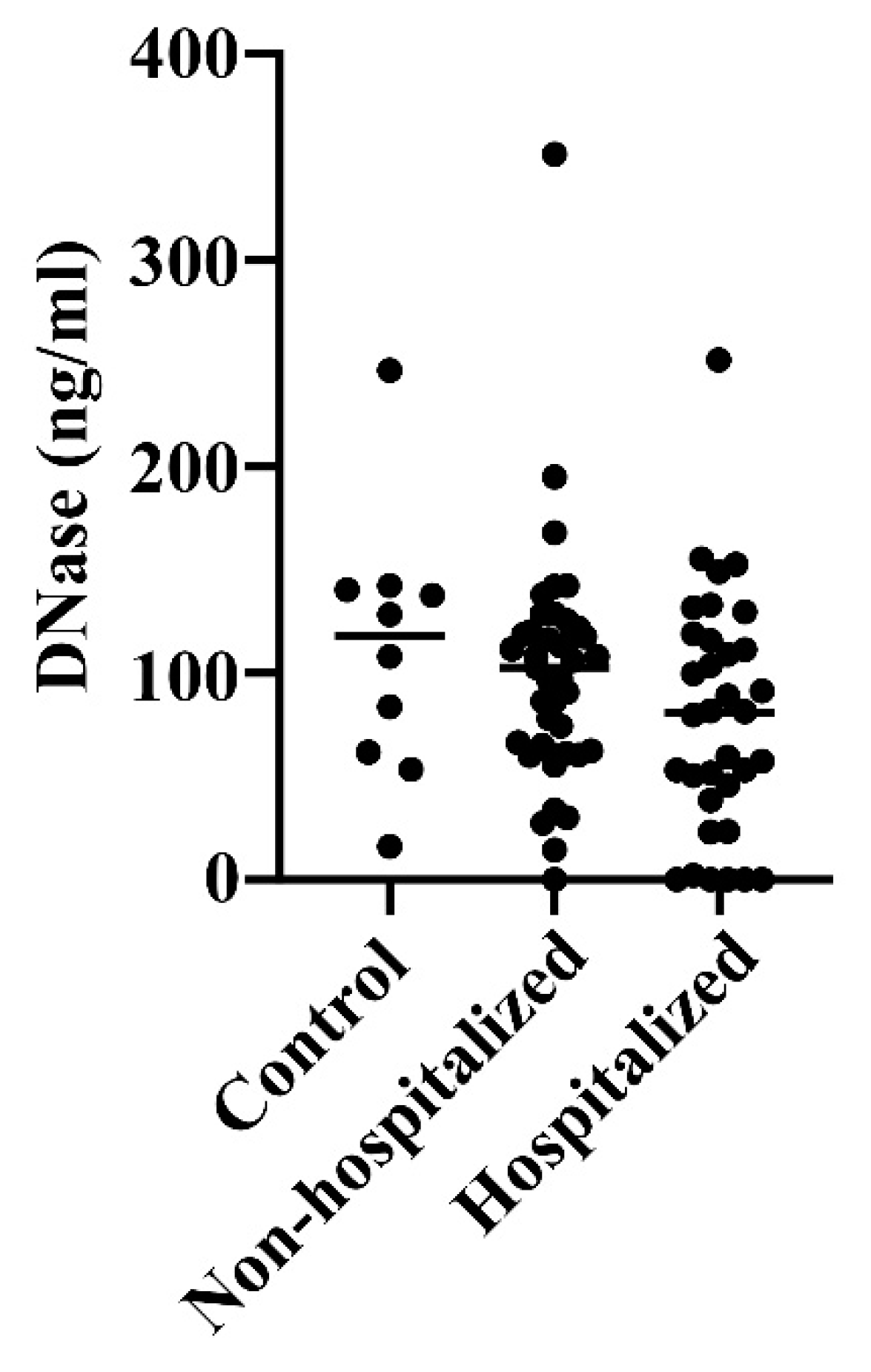

DNase, which digests DNA in NET, was found to be at similar levels in all groups, although with a slight tendency to lower levels in the hospitalized patients (not significant, n.s.) (

Figure 3).

In fact, whereas there was a moderately positive correlation (r=0.389, p=0.0005) between levels of NET and calprotectin in the COVID-19 patients, a low negative correlation (r=-0.262, p=0.022) was found between their NET and DNase levels (

Table 1).

Pearson correlation was applied to examine correlations between levels of different parameters in COVID-19 patients. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

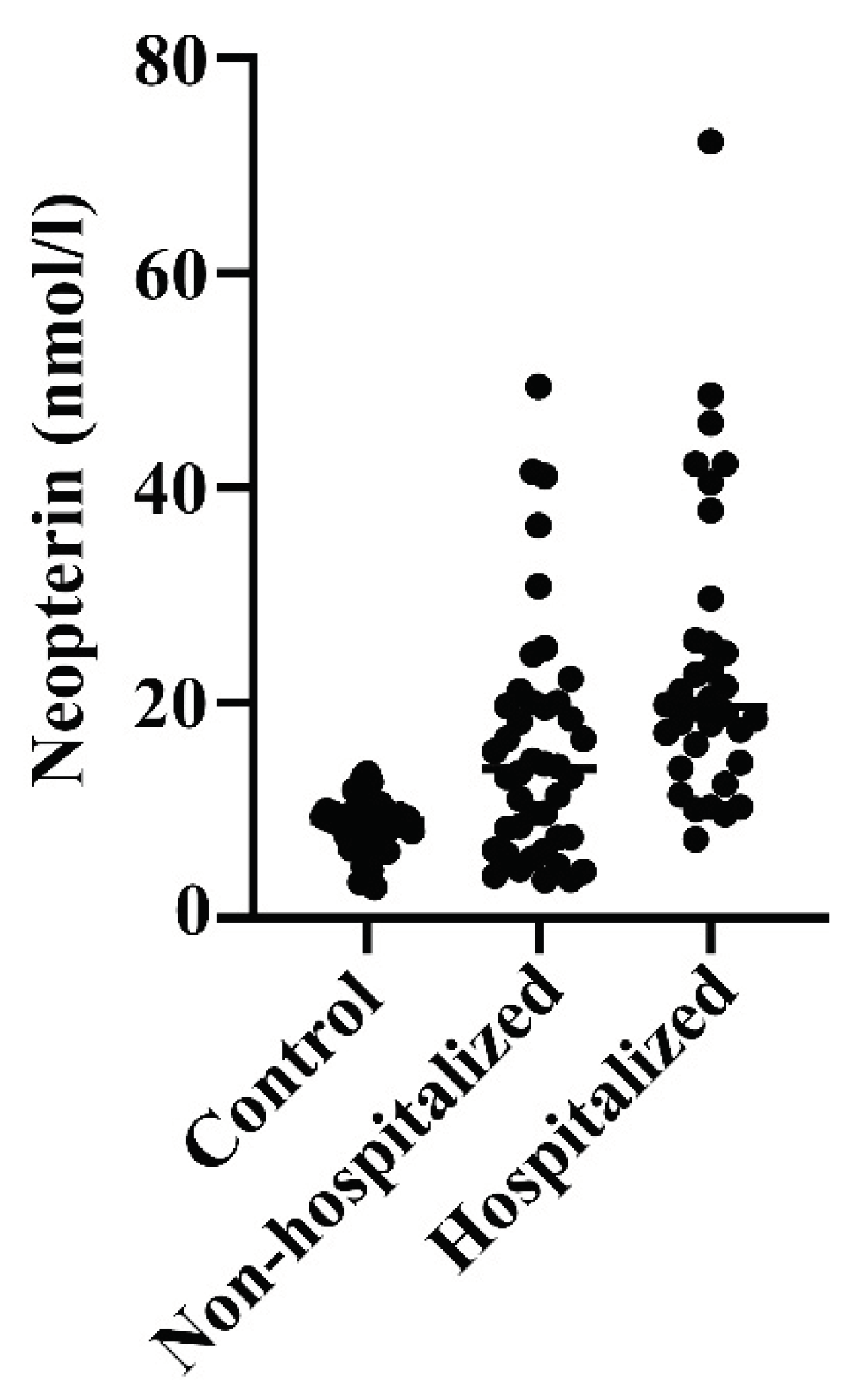

When neopterin was measured, there were 50% increased levels in hospitalized relative to non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients (p=0.0068), which again had near two-fold higher levels than healthy controls (p<0.0001) (

Figure 4). There was a low-grade positive correlation between levels of calprotectin and neopterin in these COVID-19 patients (

Table 1).

Correlations between NET, calprotectin, neopterin, and the other parameters

Table 2 reports the correlations among NET, calprotectin, and neopterin levels on one side and levels of complement activation products C5a, sC5b-9, pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory cells on the other. COVID-19 patients displayed a positive correlation between NET levels and NLR and a negative correlation with platelet count. There were positive correlations with sC5b-9 and leukocytes for calprotectin, which must be with neutrophils because of the negative correlations with lymphocytes and monocytes. There were also positive correlations between calprotectin and other parameters of systemic inflammation, such as ferritin, fibrinogen, and procalcitonin or tissue damage (AST, LDH, CPK). It was found that DNase correlated negatively with some proinflammatory parameters (CRP, C5a, ferritin), and with BAFF levels but positively with IL-17A, VEGFR2. Neopterin correlated positively with proinflammatory biomarkers (CPR, procalcitonin, ferritin), with BAFF and IFNα, with tissue damage markers (AST, LDH, CPK, and troponin HS) but negatively with albumin and platelets.

Discussion

An intense systemic inflammation with high levels of proinflammatory cytokines characterizes the SARS-CoV-2-infected patients who require hospitalization because of a more severe disease [

25,

32].

The increase of H3-NET levels in hospitalized versus non-hospitalized patients is consistent with the widely accepted neutrophil involvement in COVID-19. The complement system is activated in COVID-19, and complement deposits can be found in damaged tissues such as the lungs, which display a chemotactic effect on neutrophils and ultimately favor NETosis [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

33]. We also showed increased levels of IL-8 in sera from the same cohort of patients in Northern Italy [

25]. IL-8 may, in turn, cooperate in recruiting neutrophils to the inflammatory site, and there is evidence that high receptor-saturating IL-8 concentrations promote NETosis [

34]. The resulting enhanced NETosis is associated with thrombosis, which gives further complications at the center of the inflammatory insult [

8,

9].

Hence, the increase in calprotectin, mainly derived from neutrophils, is unsurprising in our COVID-19 cohort, where secondary pneumonia gives an influx of neutrophils to the lungs. It has been shown that calprotectin, which is a heterodimer of S100A8 (MRP-8) and S100A9 (MRP-14), is deposited on the endothelium of venules in inflamed tissue and also promotes extravasation of leukocytes [

28].

Neopterin is an old test for emerging infections [

18,

19], which has also been documented for SARS-CoV-2 infection [

20]. There is evidence that higher levels of neopterin in severe COVID-19 may be used as a predictive marker for disease severity [

35,

36]. This is confirmed here by the increased levels of neopterin and the correlation with other inflammatory markers in our COVID-19 cohort. Moreover, we find that neopterin concentrations can discriminate between hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients, similar to calprotectin and NET values. Previously, this has been shown especially for complement activation products C5a and sC5b-9 and other proinflammatory markers [

25].

Since heparin is known to be involved in NET formation/degradation and most COVID-19 hospitalized patients were treated with heparin (Fragmin), such patients could not be included when measuring NET levels [

28,

29]. Moreover, calprotectin cannot be measured accurately in patients treated with heparin because the S100A9 (MRP-14) dimer part of calprotectin displays affinity and interacts with heparin [

28]. Therefore, heparin-treated patients were excluded in the current paper.

The correlation between NET and NLR levels should be discussed because NLR is a parameter for physiological stress and is particularly important concerning lung affection and pneumonia during SARS-CoV-2 infection, where NETosis plays a critical role. The negative correlation between NET and platelet count may indicate that neutrophil activation contributes to platelet activation, consumption, and/or involvement in leuco-aggregates [

37].

There is a general agreement that SARS-CoV-2 plays a direct role in tissue damage, but the intense immune response further contributes to the clinical manifestations [

38]. The relationship between NET, calprotectin, and neopterin with COVID-19 hospitalization and, simultaneously, with biomarkers of the innate and adaptive immune responses potentially responsible for tissue damage is consistent with this view.

DNase levels are comparable in controls and COVID-19, even though with slightly decreased values in hospitalized patients. Because of the negative correlation between DNase and many proinflammatory parameters, including CRP, one may speculate whether DNase has an anti-inflammatory effect. The negative correlation with complement activation product C5a, especially, may suggest that DNase can inhibit C5 activation. On the other hand, the negative correlation of DNase with neutrophils is apparently surprising since these cells are the primary source of the target that DNase is supposed to digest. The increased release of neutrophil granule proteins associated with the DNA framework may engage a more significant amount of DNase that, in turn, is no longer available for the detection assay.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report here that increased levels of NET and calprotectin can discriminate between disease activity and predict hospitalization in a COVID-19 cohort during the first pandemic wave in Northern Italy. This finding is consistent with a previous study on the same cohort showing that a strong complement activation and proinflammatory cytokine production is associated with the disease activity. Moreover, the study evidences and confirms neopterin as an old test useful for screening emerging infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H., M.K.F., C.S., P.L.M.; Methodology, G.H., M.K.F.; Software, S.C., M.O.B., P.A.L.; Validation, P.A.L., C.B., M.R.M., L.S.H.N.M.; Formal Analysis, G.H., P.A.L.; Investigation, M.B., S.C., F.M.; Resources, P.A.L., C.B., M.R.M., L.S.H.N.M., C.M., F.M.; Data Curation, G.H., P.L.M., M.O.B., S.C., M.B.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, G.H., P.L.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, G.H., P.L.M., M.O.B.; Visualization, G.H., P.L.M.; Supervision, C.S., P.L.M., G.H.; Project Administration, C.S., P.L.M.; Funding Acquisition, C.S., P.L.M.

Funding

The publication fee has been supported by Ricerca Corrente from Italian Ministry of Health. The project has been supported by the Italian Ministry of Health, Grant COVID-2020 12371808.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Area Vasta Emilia Nord (AVEN) Ethics Committee on 28 July 2020 (protocol number 855/2020/OSS/AUSLRE – COVID-2020- 12371808) and was carried out in conformity with the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and the code of Good Clinical Practice.

Informed Consent Statement

All the participants gave their informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

This set of raw data is accessible under request because include sensitive information. Please write your request at pierluigi.meroni@unimi.it.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fagerhol, M.K.; Dale, I.; Andersson, T. A radioimmunoassay for a granulocyte protein as a marker in studies on the turnover of such cells. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir 1980, 16 Suppl, 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Berntzen, H.B.; Olmez, U.; Fagerhol, M.K.; Munthe, E. The leukocyte protein L1 in plasma and synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 1991, 20, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røseth, A.G.; Fagerhol, M.K.; Aadland, E.; Schjønsby, H. Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1992, 27, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zuo, Y.; Yalavarthi, S.; Gockman, K.; Zuo, M.; Madison, J.A.; Blair, C.; Woodward, W.; Lezak, S.P.; Lugogo, N.L.; et al. Neutrophil calprotectin identifies severe pulmonary disease in COVID-19. J Leukoc Biol 2021, 109, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, C.F.; Ermert, D.; Schmid, M.; Abu-Abed, U.; Goosmann, C.; Nacken, W.; Brinkmann, V.; Jungblut, P.R.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5, e1000639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, X. NETosis and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in COVID-19: Immunothrombosis and Beyond. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 838011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneschansker, L.; Inoue, Y.; Oklu, R.; Irimia, D. Capillary plexuses are vulnerable to neutrophil extracellular traps. Integr Biol (Camb) 2016, 8, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wu, Z.; Long, Q.; Huang, J.; Hong, T.; Liu, W.; Lin, J. Insights Into Immunothrombosis: The Interplay Among Neutrophil Extracellular Trap, von Willebrand Factor, and ADAMTS13. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 610696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Y.; Zuo, M.; Yalavarthi, S.; Gockman, K.; Madison, J.A.; Shi, H.; Woodard, W.; Lezak, S.P.; Lugogo, N.L.; Knight, J.S.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps and thrombosis in COVID-19. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2021, 51, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Alcázar, M.; Rangaswamy, C.; Panda, R.; Bitterling, J.; Simsek, Y.J.; Long, A.T.; Bilyy, R.; Krenn, V.; Renné, C.; Renné, T.; et al. Host DNases prevent vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps. Science 2017, 358, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetland, G.; Fagerhol, M.K.; Dimova-Svetoslavova, V.P.; Mirlashari, M.R.; Nguyen, N.T.; Lind, A.; Kolset, S.O.; Søraas, A.V.L.; Nissen-Meyer, L.S.H. Inflammatory markers calprotectin, NETs, syndecan-1 and neopterin in COVID-19 convalescent blood donors. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2022, 82, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetland, G.; Fagerhol, M.K.; Wiedmann, M.K.H.; Søraas, A.V.L.; Mirlashari, M.R.; Nissen-Meyer, L.S.H.; Istre, M.S.; Holme, P.A.; Schultz, N.H. Elevated NETs and Calprotectin Levels after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Vaccination Correlate with the Severity of Side Effects. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, J.; Uzun, G.; Zlamal, J.; Singh, A.; Bakchoul, T. Platelet-neutrophil interaction in COVID-19 and vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1186000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, H.H.L.; Perdomo, J.; Ahmadi, Z.; Zheng, S.S.; Rashid, F.N.; Enjeti, A.; Ting, S.B.; Chong, J.J.H.; Chong, B.H. NETosis and thrombosis in vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerhol, M.K.; Schultz, N.H.; Mirlashari, M.R.; Wiedmann, M.K.H.; Nissen-Meyer, L.S.H.; Søraas, A.V.L.; Hetland, G. DNase analysed by a novel competitive assay in patients with complications after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination and in normal unvaccinated blood donors. Scand J Immunol 2023, 98, e13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieseg, S.P.; Baxter-Parker, G.; Lindsay, A. Neopterin, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress: What Could We Be Missing? Antioxidants (Basel) 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Moyes, D.L.; Ho, J.; Naglik, J.R. Candida innate immunity at the mucosa. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2019, 89, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nübling, C.M.; Chudy, M.; Volkers, P.; Löwer, J. Neopterin levels during the early phase of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, or hepatitis B virus infection. Transfusion 2006, 46, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayersbach, P.; Fuchs, D.; Schennach, H. Performance of a fully automated quantitative neopterin measurement assay in a routine voluntary blood donation setting. Clin Chem Lab Med 2010, 48, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.; Gostner, J.M.; Nilsson, S.; Andersson, L.M.; Fuchs, D.; Gisslen, M. Serum neopterin levels in relation to mild and severe COVID-19. BMC Infect Dis 2020, 20, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holter, J.C.; Pischke, S.E.; de Boer, E.; Lind, A.; Jenum, S.; Holten, A.R.; Tonby, K.; Barratt-Due, A.; Sokolova, M.; Schjalm, C.; et al. Systemic complement activation is associated with respiratory failure in COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 25018–25025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvelli, J.; Demaria, O.; Vély, F.; Batista, L.; Chouaki Benmansour, N.; Fares, J.; Carpentier, S.; Thibult, M.L.; Morel, A.; Remark, R.; et al. Association of COVID-19 inflammation with activation of the C5a-C5aR1 axis. Nature 2020, 588, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugno, M.; Meroni, P.L.; Gualtierotti, R.; Griffini, S.; Grovetti, E.; Torri, A.; Panigada, M.; Aliberti, S.; Blasi, F.; Tedesco, F.; et al. Complement activation in patients with COVID-19: A novel therapeutic target. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020, 146, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cugno, M.; Meroni, P.L.; Gualtierotti, R.; Griffini, S.; Grovetti, E.; Torri, A.; Lonati, P.; Grossi, C.; Borghi, M.O.; Novembrino, C.; et al. Complement activation and endothelial perturbation parallel COVID-19 severity and activity. J Autoimmun 2021, 116, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meroni, P.L.; Croci, S.; Lonati, P.A.; Pregnolato, F.; Spaggiari, L.; Besutti, G.; Bonacini, M.; Ferrigno, I.; Rossi, A.; Hetland, G.; et al. Complement activation predicts negative outcomes in COVID-19: The experience from Northen Italian patients. Autoimmun Rev 2023, 22, 103232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besutti, G.; Ottone, M.; Fasano, T.; Pattacini, P.; Iotti, V.; Spaggiari, L.; Bonacini, R.; Nitrosi, A.; Bonelli, E.; Canovi, S.; et al. The value of computed tomography in assessing the risk of death in COVID-19 patients presenting to the emergency room. Eur Radiol 2021, 31, 9164–9175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, M.G.; Djuric, O.; Besutti, G.; Ottone, M.; Amidei, L.; Bitton, L.; Bonilauri, C.; Boracchia, L.; Campanale, S.; Curcio, V.; et al. Clinical and imaging characteristics of patients with COVID-19 predicting hospital readmission after emergency department discharge: a single-centre cohort study in Italy. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e052665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.J.; Tessier, P.; Poulsom, R.; Hogg, N. The S100 family heterodimer, MRP-8/14, binds with high affinity to heparin and heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans on endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 3658–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longstaff, C.; Varjú, I.; Sótonyi, P.; Szabó, L.; Krumrey, M.; Hoell, A.; Bóta, A.; Varga, Z.; Komorowicz, E.; Kolev, K. Mechanical stability and fibrinolytic resistance of clots containing fibrin, DNA, and histones. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 6946–6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerhol, M.K.; Johnson, E.; Tangen, J.M.; Hollan, I.; Mirlashari, M.R.; Nissen-Meyer, L.S.H.; Hetland, G. NETs analysed by novel calprotectin-based assays in blood donors and patients with multiple myeloma or rheumatoid arthritis: A pilot study. Scand J Immunol 2020, 91, e12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerhol, M.K.; Rugtveit, J. Heterogeneity of Fecal Calprotectin Reflecting Generation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in the Gut: New Immunoassays Are Available. Journal of Molecular Pathology 2022, 3, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merad, M.; Blish, C.A.; Sallusto, F.; Iwasaki, A. The immunology and immunopathology of COVID-19. Science 2022, 375, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macor, P.; Durigutto, P.; Mangogna, A.; Bussani, R.; De Maso, L.; D’Errico, S.; Zanon, M.; Pozzi, N.; Meroni, P.L.; Tedesco, F. Multiple-Organ Complement Deposition on Vascular Endothelium in COVID-19 Patients. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijeira, A.; Garasa, S.; Ochoa, M.D.C.; Cirella, A.; Olivera, I.; Glez-Vaz, J.; Andueza, M.P.; Migueliz, I.; Alvarez, M.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.E.; et al. Differential Interleukin-8 thresholds for chemotaxis and netosis in human neutrophils. Eur J Immunol 2021, 51, 2274–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmann-Weiler, R.; Lanser, L.; Burkert, F.; Seiwald, S.; Fritsche, G.; Wildner, S.; Schroll, A.; Koppelstätter, S.; Kurz, K.; Griesmacher, A.; et al. Neopterin Predicts Disease Severity in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021, 8, ofaa521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozger, H.S.; Dizbay, M.; Corbacioglu, S.K.; Aysert, P.; Demirbas, Z.; Tunccan, O.G.; Hizel, K.; Bozdayi, G.; Caglar, K. The prognostic role of neopterin in COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 1520–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, M.; Canzano, P.; Becchetti, A.; Tremoli, E.; Camera, M. Alterations in platelets during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Platelets 2022, 33, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J.S.; Caricchio, R.; Casanova, J.L.; Combes, A.J.; Diamond, B.; Fox, S.E.; Hanauer, D.A.; James, J.A.; Kanthi, Y.; Ladd, V.; et al. The intersection of COVID-19 and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).