1. Introduction

From time immemorial, humanity has sculpted stone and cut wood. A readily apparent method of obtaining a desired structure is to remove deliberate volume from a blank stock material until the final shape is manifest. This subtractive take on manufacturing has long been the traditional paradigm, achieved today with precision and scale via many mature techniques including computer numerical control (CNC) machining, abrasive water jet machining (AWJM), laser beam machining (LBM), ultrasonic machining (USM), and electric discharge machining (EDM) [

1].

Additive manufacturing (AM) then stands in contrast, wherein a desired structure is instead obtained by joining together smaller base material units into larger desired structures. Instrumentation that achieves AM are often referred to as 3D printers, based on the concept of a conventional 2D printer for documents and images generalized to 3D space. In this way, many new benefits are realizable - such as complex internal geometries, [

2] more sustainable processes due to lack of swarf, [

3] and multi-material parts with property gradients [

4]. The advent of AM is comparatively recent, with major commercialization starting from the 1980s,[

5,

6,

7] and has less mature processing techniques in terms of both the precision of obtainable structures and library of processable materials. Advancements in AM are thus of intense current interest, both in terms of academic research and industrial application.of particular interest is the applicability of AM to biopolymeric materials. The umbrella of biopolymeric materials includes those extracted from biomass like starch or collagen, produced by microbes like poly(hydroxybutyrate), and chemically synthesized using monomers from agroresources like poly(lactic acid) [

8]. While a main thrust of AM has been toward the realm of mechanics and inorganic manufacturing, similarly to traditional subtractive manufacturing workshops, AM of these biopolymeric materials holds opportunities to impact broader functional and medical applications.

Despite the recency of human-driven AM, additive materials creation is ubiquitous in nature. From spiders spinning silks[

9,

10] to mollusks mineralizing their shells,[

11,

12] many complex and highly performant materials are created in additive processes that build up from simpler base units. Crucially, there remain large gaps between what nature has accomplished and what humans can currently reach. Furthermore, natural processes of evolution are well known for reaching local, but not global, optima.[

13,

14] This means that there is both a lot to learn from studying AM of biopolymeric materials in the context of nature, and a lot to gain in terms of improving natural solutions with greater understanding.

In this review, we first provide perspective on the state of biopolymeric AM techniques and methodologies. Then, we review the advancements that biopolymeric AM enables in the context of augmenting natural systems. Specifically, we view the impacts of biopolymeric AM in how synthetic structures can be applied for biomedical health contexts. We end with a perspective on the possibilities yet to be achieved.

2. Process Status for Additive Manufacturing of Biopolymeric Materials

2.1. Intro

When viewed from a process perspective, evaluations of the state of biopolymer AM can be divided into three categories: what you put in, what the manufacturing instrument can do, and what you get out. Specifically, we review the library of biopolymeric materials under study as AM feedstocks, the categories of AM achievable by current 3D printer instrumentation, and the resultant structures and functionalities generated from the process. In this way, we aim to highlight the current state of the field and areas ripe for further study.

2.2. Categories of Biopolymeric AM Material Feedstock

Biopolymeric materials have received recent attention, with a continually increasing amount of studies on applicability to AM from 2013 to 2020 [

15]. While some studies limit discussion of biopolymeric materials to those strictly extracted from biomass, here we consider the wider diversity of materials encompassing not only those that can be 1) directly extracted from the biomass of plants, animals, and fungi; but also 2) produced by microbial organisms; and 3) chemically synthesized from biological sources. Importantly, the biocompatibility of these polymers is crucial for biomedical applications. At the end of this section 2.2,

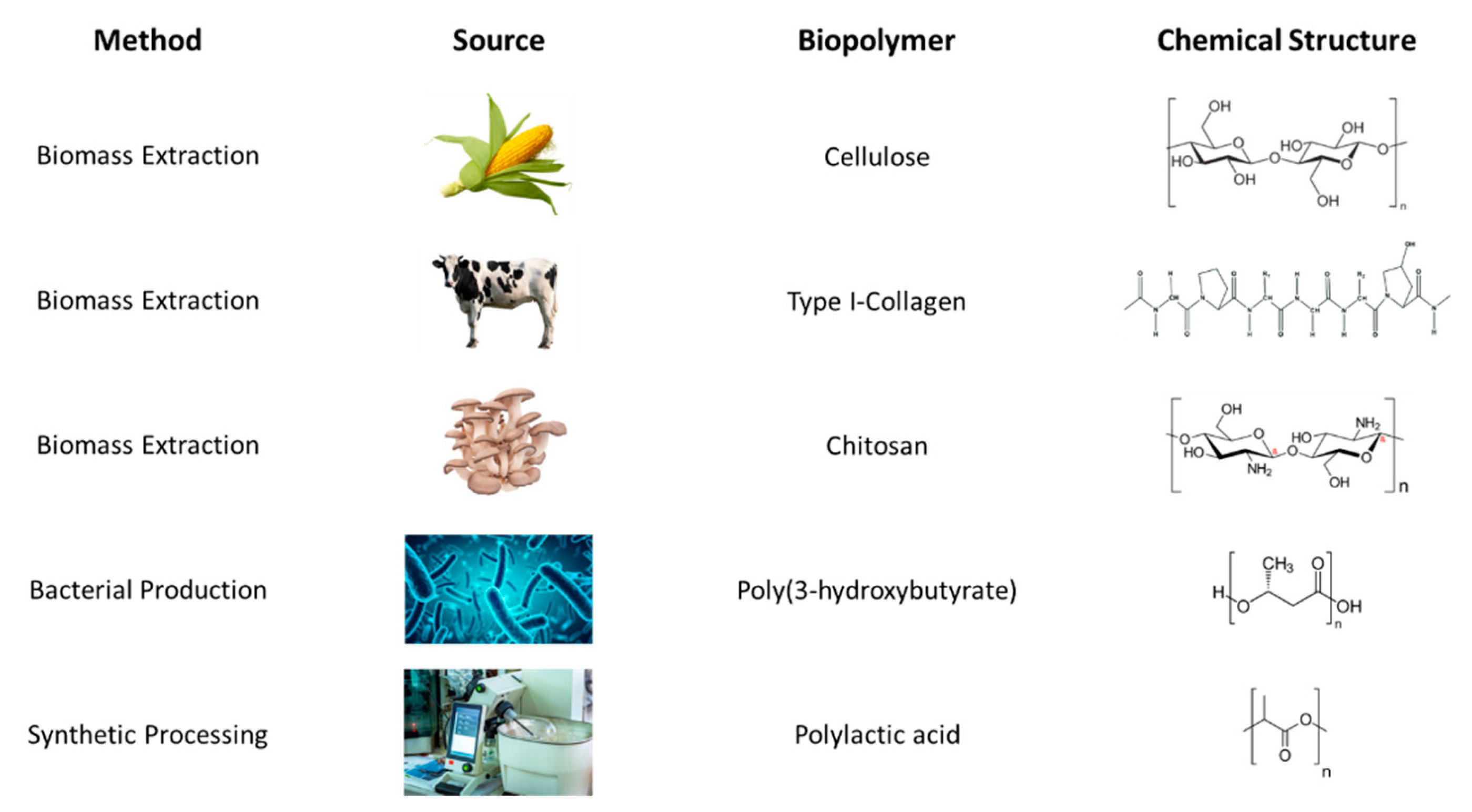

Figure 1 presents a brief overview of the biopolymers discussed.

2.2.1. From Biomass Extraction

In this section, we focus on one major biopolymer from each category of biomass: cellulose from plants, collagen from animals, and chitosan from fungi. Of course, a wide library of other biopolymers exists within these source categories, but the biopolymers highlighted here are selected because they are some of the most abundant and heavily studied examples.

2.2.1.1. From Plants, Cellulose

Cellulose is the most abundant biopolymer available [

16] and can be sourced from various plant fibers like banana peels, [

17] spent grain, [

18] wood, [

19] corn husks, [

20] etc. Importantly, many of these sources are typically waste products from other industries, making the utilization of cellulose attractive from both sustainability and economic perspectives. Cellulose molecules are a linear homopolysaccharide comprised of β-(1→4) linked d-anhydroglucopyranose sugar units, [

21] typically extracted from these biomass sources via a three step process involving pre-hydrolysis, pulping, and bleaching [

22].

Cellulose is commonly processed into nanocellulose hydrogel for AM. This is because nanocellulose hydrogel is biocompatible and can mimic extracellular matrix environment for biomedical applications. In particular, nanofibrillated cellulose has been shown to support cellular growth and proliferation [

23]. Alternatively, dissolved cellulose has been used to form 3D printing inks. Because cellulose does not dissolve readily in water, other solvent systems have been of great interest. Specifically, ionic liquids have been investigated [

24] due to their ability to disrupt the native hydrogen bonding network of cellulose without requiring high melting temperatures, their less hazardous vapor pressures, and their recyclability [

25]. Furthermore, cellulose has also been utilized in nanocrystal [

26] or nanofiber [

27] form for the manufacturing of structures with tunable mechanical properties. These can be used to make both pure cellulose structures and composite structures where the nanocellulose acts as inclusions to a matrix material. Alignment of nanocrystals or nanofibers via the 3D printing process, the percentage of cellulose inclusions, and interface chemistry between the cellulose and matrix material are all levers that can affect final mechanical properties.

2.2.1.2. From Animals, Collagen

Collagen is the most abundant protein in animals and can be sourced from fish, [

28] livestock, [

29] poultry, [

30] etc. It is a significant structural biopolymer natively present in skin, bones, and tendons, and can also be sourced from waste streams, making the utilization of collagen immediately attractive for synthetic biological applications. Collagen is comprised of a righthanded bundle of three parallel, left-handed polyproline II-type helices [

31].

In order to maintain the integrity of additively manufactured structures, collagen is commonly processed with various crosslinking methods to improve mechanical properties. This can be done through physical processes such as dehydrothermal treatment, [

32] or chemical processes such as with carbodiimide reactions [

33]. Furthermore, other levers have been investigated to control the mechanical properties and suitability of collagen to 3D printing, such as pH tuning to affect gelation kinetics and storage moduli, [

34] incorporation of denatured collagen i.e. gelatin, [

35] or the incorporation of other polymers such as alginate to form mixed bioinks [

36]. When tuning collagen processing parameters, properties relating to biocompatibility are considered along with those relevant to facilitating particular AM methods, such as viscosity or shear thinning.

2.2.1.3. From Fungi, Chitosan

Chitosan can be derived from chitin, the second most abundant biopolymer, via partial deacetylation and is well-known for comprising the cell walls of fungi [

37]. Though chitin can be sourced as a waste product from the shells of marine creatures like lobster, [

38] shrimp, [

39] and crab [

40] and converted to chitosan, extraction of chitin and chitosan from fungi requires less harsh chemical procedures and can result in more reproducibly consistent product [

41]. Chitosan is comprised of β-(1-4) linked 2-amino-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranose, similar in structure to cellulose but with an acetamide group replacing the hydroxyl at position C-2 [

42].

When sourced from marine shells, chitosan extraction follows a typical process of mechanically grinding the feedstock into powder, demineralization with acid, deprotonization with base, extraction with acetone, bleaching and washing to isolate chitin, and deacetylation with a final wash to yield chitosan [

43]. When dealing with fungal sources, there is no need for the initial mechanical grinding and harsh demineralizing acid base treatments. Fungal sourcing is thus promising and, as the commercial standard remains marine waste extraction, relatively unexplored.[

41,

44] Similar to the other previously described biopolymers, hydrogel bioinks have been pursued for the 3D printing of chitosan as well. Such gels can be achieved through a host of both physical and chemical crosslinking strategies resulting in a range of properties and behaviors [

45].

2.2.2. By Microbial Production

Polyhydroxyalkanoates, or PHAs, are a group of thermoplastic biopolymers produced by bacteria via fermentation [

46] when in the presence of excess carbon and limited other nutrients [

47]. PHA production from bacteria can be understood as a two-stage process. First, in the growth stage, bacteria are introduced to a sterile, nutritious environment of trace metals with a carbon source. Then, in the next stage, an essential nutrient is limited, resulting in the accumulation of PHAs [

48]. PHAs are highly biodegradable and are a by-product of algae biofuel production, [

49] making them highly attractive for alternative plastic material applications. The most studied PHA is poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), a linear polyester of D (-)-3-hydroxybutyric acid [

49].

However, applications of PHB are limited due to poor physio-chemical properties and brittleness [

50]. As a result, processing workflows to both improve mechanical properties and increase property stability over time have been of interest [

49]. For example, changing the identity of monomers to one of 150 different known units, [

46] using co-polymers of more than one monomer unit, [

51] or changing the bacteria feeding regime [

52] all impact final properties. In addition to the drawbacks of unstable material composition and poor thermomechanical properties, production costs are high [

53]. Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of PHAs have led to commercial production at companies across the world [

53] with the market entering a growth phase [

46].

2.2.3. Via Synthetic Processing

Polylactic acid, or PLA, is one of the most commonly used synthetic biodegradable polymers, produced by acid condensation or acid ester ring opening polymerization [

54]. PLA has a variety of desirable properties including biocompatibility, biodegradability, high strength, high modulus, thermoplasticity, and the ability to be made from annually renewable resources [

55,

56]. Lactic acid itself is chiral and thus can exist as two enantiomers, L- and D-lactic acid, so PLA can exist as poly(L-lactide), poly(D-lactide), and poly(DL-lactide) [

57].

Various methods of tuning the properties of PLA for AM applications have been explored, such as integrating carbon-based nanomaterials, other biopolymers, or inorganic crystals to form composite materials [

58]. Other treatments used to tweak properties for 3D printing include copolymerization with entities like glycolic acid, poly(ethylene glycol), or polycaprolactone, among others, in order to alter properties such as crystallinity, melting point, and solubility [

59]. And surface plasma treatments have been used to alter cell affinity [

60,

61] for biological applications. Due to its favorable properties, PLA is one of the most commercially used biopolymers in the world, with increasing industrial demand as companies move away from traditional petroleum-based polymers [

62].

2.3. Printing Methodologies for AM of Biopolymeric Materials

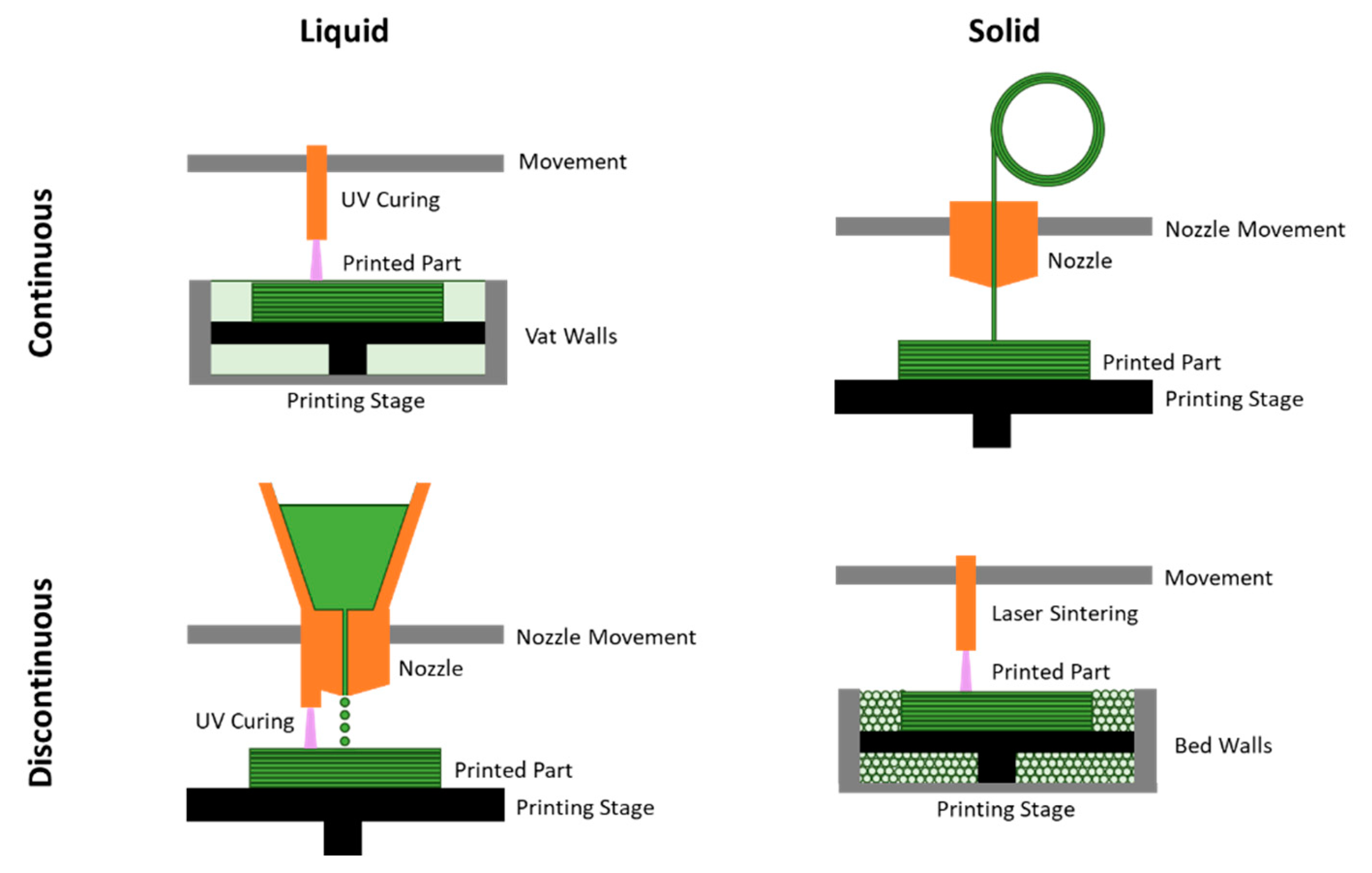

AM techniques can be organized in various ways. It is often common to divide them by the state of matter of the feedstock,

i.e. liquid or solid, and here we further subdivide by the continuity of the feedstock material. For example, stereolithography is conducted with liquid feedstock in a continuous bath, while fused deposition modeling is conducted with solid feedstock from a continuous filament. Material jetting is an example of additively manufacturing structures with liquid feedstock from discontinuous droplets, while powder bed fusion is one of solid feedstock from discontinuous powders. These approaches are illustrated in

Figure 2. Here, we briefly discuss these four categories of AM for biopolymeric materials, noting that many variations of specific techniques exist within these broad categories, then highlight modern advances in AM methodology.

2.3.1. AM with Continuous Liquid Feedstock

Printing from a continuous liquid feedstock is a classic avenue for AM, with the earliest 3D printers patented in 1984 [

5] employing a stereolithographic approach. Specifically, stereolithography begins with a vat of photopolymerizable liquid feedstock in contact with a printing stage. Then, a computer controlled light source (often UV light) is scanned across the vat to solidify a slice of the final desired structure onto the printing stage. The printing stage is then spatially incremented, allowing the previously solidified surface to be covered with new un-polymerized liquid feedstock. Alternate steps of scanning the light source over the vat and incrementing the sample stage result in the successive slice-by-slice construction of the final material. Many variations of stereolithography exist today, with differences in sample stage orientation and light source. Stereolithography has been employed with cellulose nanofibril inclusions, [

63] gelatin bioinks, [

64] chitosan derivatives, [

65] and PHA-based oligomers [

66].

2.3.2. AM with Continuous Solid Feedstock

Printing with a continuous solid feedstock is commonly achieved by fused deposition modeling (FDM). FDM uses a continuous filament of material guided by a heated printer head, which deposits patterns of material onto a printer bed in subsequent layers. When heated, the feedstock softens enough to extrude from the printer head and fuse to either the printer bed at the first layer, or previous material layers in subsequent layers. Similarly, another technique called direct energy deposition (DED) instead uses a laser or electron beam to heat and deposit the solid feedstock, but is often used for metallic materials. PLA is the most commercially widespread material for FDM, with research in this area focusing on optimizing properties with material inclusions or printing parameters like bed temperature, nozzle temperature, print speed, and nozzle diameter [

67]. Outside of PLA, studies have focused on expanding the library of FDM materials to include other plant-based biopolymers [

68] and PHA blends [

69].

2.3.3. AM with Discontinuous Liquid Feedstock

Printing with discontinuous liquid feedstock is commonly achieved through various types of jetting. This category of techniques is similar to FDM, except discontinuous liquid droplets are used instead of a continuous solid filament extruded through a nozzle. These droplets can be deposited in an inkjet via the Rayleigh instability principle, or deposited by controlled signals. This more advanced drop-on-demand (DOD) inkjet printing can be accomplished through thermal or piezoelectric actuators [

70]. Material jetting (MJ) has been suited for printing various types of biopolymers, including carboxymethyl cellulose inks, [

71] collagen hydrogel precursors, [

72] and lactose-modified chitosan [

73].

2.3.4. AM with Discontinuous Solid Feedstock

Printing with discontinuous solid feedstock is commonly achieved via powder bed fusion (PBF). This category of techniques is similar to vat polymerization and stereolithography, except the feedstock container is filled with a bed of solid individual powder grains instead of a liquid vat. In this technique, the discontinuous powder solids are fused together into the desired structural patterns with a high energy source. Different variations of powder bed fusion have been achieved with different energy sources, such as electron beam melting (EBM), selective heat sintering (SHS), or selective laser sintering (SLS). Similarly, binder jetting (BJ) also uses solid powder feedstock, but instead of thermal or laser mediated fusion, a secondary binder material is used to hold the structure together. These powder methods of AM are quite versatile, for example, with binder jetting used for various wood powders [

74] or with incorporating collagen into the binder material, [

72] selective laser sintering used for chitosan composite membranes [

75] and PHA scaffolds, [

76] and laser powder bed fusion used for PLA/hydroxyapatite composites [

77].

2.3.5. Further Advancements in Printing Methods and Functionality

The impact of modern artificial intelligence has provided advancements to many aspects of AM. At the processing level, machine learning models have seen great application toward addressing the complex multivariable optimization problems at the heart of printer parameter tuning for stereolithography methods, [

78] extrusion methods [

79] like fused deposition modeling, material jetting methods, [

80] and powder bed fusion methods [

81]. As a result, structures can be obtained quicker, with greater structural precision, and with less waste. At the design level, ML models can be used for tasks like topology optimization [

82] to optimize for certain properties or minimize material used. Recent works have leveraged ML models for inverse design, yielding 3D printed structures that possess precisely desired mechanical properties [

83,

84].

Beyond traditional categories of 3D printing, recent studies have focused on the concept of 4D printing, wherein the generated materials are made to have structure in time as well as space. This paradigm of 4D printing, first coined in 2013, encapsulates dynamic, functional structures that respond to a variety of stimuli [

85]. Of particular note are shape memory polymers (SMP) which undergo a two stage cycle: first, programmed deformation to a temporary desired shape, and second, recovery of the original shape via external trigger [

86]. With respect to the previously mentioned categories of biopolymers in

Section 2.2, 4D printing has yielded many heat-activated structures, for example extruded cellulose composites, [

87] extruded shape memory gelatin-based hydrogels with self-healing properties, [

88] and hydroxybutyl methacrylated chitosan hydrogels from stereolithography [

89]. Of course, heat activation is not the only structural trigger, for example extruded PHA/PLA composites have been made to activate structural change in response to changes in humidity [

90]. Other triggers such as pH, light, magnetic fields, or electric fields, have also been explored [

91]. ML models have also found use in the context of 4D printing, to solve the complex inverse design problem of obtaining structures with controlled deformation morphologies [

92]. In the following section, we delve deeper into specific impacts of biopolymer AM to biocompatible medical contexts.

3. Biocompatible Medical Applications

3.1. Intro

There are 4 basic types of tissue in the human body: epithelial, connective, muscle, and neural tissue. AM of biopolymeric materials in the context of these four tissues are thus topics of great interest and impact. We highlight the impacts of biopolymer AM on a representative system from each of these categories, specifically skin, bone, heart, and nerve applications. A high-level overview is provided in the following

Table 1, with detailed discussion in the subsequent sections.

3.2. Skin

Skin has long been a promising target for bioprinting methods. Like other tissues, autologous transplant is the standard treatment for skin injuries like severe burns, but the supply of autologous skin tissue is often limited, for instance in the case of full body burns [

93]. Engineered skin tissue offers the possibility of developing personalized skin grafts for such patients.

Early attempts at bioprinting viable skin tissue used the laser-induced forward transfer (LIFT) technique, demonstrating that nearly all of the transferred cells survived the printing process [

94]. Recent research however has focused on printing bioinks to create full-thickness skin substitutes that mimic the skin's dermal and epidermal layers [

93]. In 2022, Niu et. al. [

95] focused on optimizing the ratios of concentrations of various materials in bioinks. Their technique creates a skin tissue substitute that exhibits a gradient porous structure and interconnected macroscopic channels, better mimicking the vasculature of natural skin tissue. This results in accelerated wound healing, reduced skin wound contraction, and re-epithelialization in vivo. Additionally, in 2022, Liu et. al. [

96] focused on improving the efficacy of printing methods. By introducing a sterile wire mesh to facilitate an air-liquid interface culture, they were able to produce skin tissue more easily and reliably than with other methods.

3.3. Bone

In most cases, the medical use of biomaterials in 3D-applications for bone focuses on enabling bone repair and is mainly in the exploratory and pre-clinical stages. The few applications where AM involving bone has progressed into the clinical and production stages are more superficial to health, meaning they are meant for aesthetic or temporary purposes. One example is the Osteoplug

TM-C, a polycaprolactone burrhole cover meant to improve aesthetic outcomes of patients undergoing burrhole craniostomy [

97]. Another example are surgical guides that temporarily interface with exposed bone and greatly benefit from the flexibility and patient-specificity AM methodologies provide [

98].

For studies in bone repair and replacement, scientists are concerned with two issues. The first is optimizing biomaterial composition and scaffolding methods to engineer bone grafts that can compete with the gold standard of auto/allografts and commonly used titanium scaffolds [

99,

100]. The aim being that more organic materials would integrate with the body and facilitate bone repair better than existing clinical options [

101]. Until recently, few biomaterials have been determined useful due to lacking the strength and printability of their metallic counterparts. A 2023 study by Bie et. al. [

100] shifts to using new ingredients for a composite biomaterial: ZrO

2 (providing strength and stability), hydroxyapatite (already present in bone and teeth), and polyvinyl alcohol PVA1788 (soluble biopolymer with a variety of health applications). The use of ZrO

2 gave the scaffolds increased compressive strength. The composite’s cytotoxicity testing shows that the generated scaffold supports in vitro cell growth and proliferation, and future studies are planned to test the scaffold performance in vivo. The second issue is on how to properly test or compare these printing methods in vivo. Even when specifically focused on repair of craniomaxillofacial bones, scientists found animal studies of printing methodologies difficult to evaluate against the current standard and other solutions [

97].

3.4. Heart

The ability for 4D printing to yield dynamic, responsive biopolymeric materials provides promising potential for a variety of biomedical applications. Synthetic actuators abound in the literature, with many electromagnetically triggered materials explored to simulate muscular action [

85]. However, despite this excitement and potential for large impact, 4D printing applications remain in the proof of concept stage [

85].

Of particular muscular interest is the ability for AM biopolymers to impact disfunction of the heart, and here the complexity of the system is apparent. Specifically, the workflow for using AM to treat cardiac engineering problems includes the cultivation of a particular patient’s human induced pluripotent stem cells; the differentiation of those cells into fibroblasts, cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells; and then the engineering of muscle structures and vascularization into cardiac tissue [

102]. Each of these steps is non-trivial but great strides have been made in recent years. For example, the technical feasibility of producing clinical-grade human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiovascular progenitors was demonstrated in 2018 [

103]. And in 2020, 3D printed artificial heart structures have been made that both incorporate a high density of cardiomyocytes and possess electromechanical function. To accomplish this, Kupfer et. al. [

104] combine 1) a gelatin methacrylate and lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate base with 2) proteins critical to cardiomyocyte differentiation - specifically fibronectin, laminin-111, and collagen methacrylate. This combination is mixed with human induced pluripotent stem cells and enables the stem cells to first proliferate into a stable heart structure and subsequently mature into cardiomyocytes once printed. The cellular mixture is printed in a hydrogel to support the eventual heart structure as the cells proliferated and matured. The matured final structure, called a human chambered muscle pump, was proven to be both structurally robust and electromechanically functioning [

104].

3.5. Nerve

As with skin and bone, the gold standard for nerve-related medical remediation is autografting, in which functional nerve tissue from the patient is transferred to the location of disfunction within the patient in order to restore function. However, the chance of functional recovery is only around 50%, with various drawbacks including potential loss of function at the donor site.[

105] As a result, there is intense interest in developing alternative practices, with an emergent approach leveraging biopolymer structures to guide the regrowth of nerve tissue.

Though hollow nerve guides such as NeuroGen®, Neurolac®, and Neurotube® (which are comprised of collagen, poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone), and poly(glycolic acid) respectively) have found clinical success for short gap injuries since the 2000’s, [

106] more complicated structures attainable by 3D printing have been recently explored for larger injuries. Specifically, 3D printing can be used to make personalized nerve guide structures with complex internal scaffolding, incorporating embedded stem cells for differentiation into neural cells and gradients of additional growth factors to assist regeneration [

107,

108]. In 2023, Fang et al. [

109] used electrospinning and melt electrowriting, a form of additive manufacturing in which polymer melt is extruded from a needle with an applied voltage, to fabricate conductive multiscale-filled nerve guidance conduits (MF-NGCs) comprised of poly(lactide-cocaprolactone), collagen, and reduced graphene oxide. These MF-NGCs were used for sciatic nerve regeneration in rats and outperformed hollow NGCs. In addition to peripheral nerve studies like this, other works have investigated central nervous applications. For example, Liu et. al. [

110] 3D printed collagen/chitosan composite scaffolds that incorporate neural stem cell derived exosomes pretreated with Insulin-like growth factor 1, and found both physical brain tissue regeneration and behavioral recovery of motor deficits by applying them in rats with traumatic brain injuries.

4. Future Outlook

4.1. The World Today

Complex systems beyond current engineering capabilities abound in nature. From close inspection of natural systems, people have been inspired to extract biological materials in the aim of co-opting their desirable properties and behaviors for their own purposes. Such materials of interest have been studied from plant, animal, fungi, and bacterial sources, and isolated to yield a large library of biopolymers for additive manufacturing. Functionally, the dynamic structures in nature have also inspired the formation of 4D printed structures, which incorporate an element of structure in time via specifically controlled changes in morphology. In these ways, natural systems have led the development of synthetic additive manufacturing.

Commensurately, people have explored synthetic strategies for impacting natural systems. Many of the consequences of biopolymer additive manufacturing are immediately applicable to biomedical contexts. The ability to generate structures with complex geometries, from biocompatible feedstock, with tunable mechanical properties, and the potential for dynamic shape changing has already begun impacting human health - from the printing of artificial skin and bone replacement composites to cardiac tissues and nerve regrowth scaffolding. Today, additively manufacture biopolymers are explored as potential replacements for current standards of treatment.

4.2. The Open Threads

Even after decades of interest in additive manufacturing, many of the desired promises of biopolymer applications remain difficult to achieve.

Much success has been found in the application of 3D printing to skin structures. Using animal models, skin tissue substitutes have been shown in vivo to accelerate wound healing. Further studies will be focused on translating these advancements to humans, requiring future clinical trials.

In the manufacturing of bone structures, many 3D printed biomaterial-based scaffolds have been tested using preclinical animal models. However, a lack of testing guidelines makes comparing the many biomaterial composites to the gold standard of auto/allografts and other proposed composites unclear [

97].

While great progress has been made on the complex matters of the heart, putting together every biological, mechanical, and functional requirement for a fully artificial heart has yet to be accomplished. Progress in the separate issues of cell cultivation, precision printing, and greater control of mechanical behaviors will together compound the efficacy of artificial heart studies.

In the context of nerve treatment, while preliminary studies have shown levels of success in rat models, such techniques are far from clinical trials in humans. Many technical difficulties for optimal nerve regeneration need to be ironed out, with parameters to be optimized and formulations to be tested.

For questions in the realms of optimization and categorization, artificial intelligence models may provide a clearer path to solution than traditional manual iteration. While current efforts are focused on generating synthetic replacements for natural structures, the future may hold the possibility for augmentation and alteration, with various emerging technologies having a cumulative effect on each other.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.L., project administration, A.J.L., writing – original draft preparation, A.J.L., A.F.L., S.P.W., writing – review and editing, A.J.L., A.F.L., S.P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davis, R.; Singh, A.; Jackson, M. J.; Coelho, R. T.; Prakash, D.; Charalambos, C. P.; Ahmed, W.; Da Silva, L. R. R.; Lawrence, A. A. A Comprehensive Review on Metallic Implant Biomaterials and Their Subtractive Manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 1473–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadroitsev, I.; Thivillon, L.; Bertrand, P.; Smurov, I. Strategy of Manufacturing Components with Designed Internal Structure by Selective Laser Melting of Metallic Powder. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 254, 980–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, B. 3-D Printing: The New Industrial Revolution. Bus. Horiz. 2012, 55, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaali, M. J.; Cruz Saldívar, M.; Herranz de la Nava, A.; Gunashekar, D.; Nouri-Goushki, M.; Doubrovski, E. L.; Zadpoor, A. A. Multi-Material 3D Printing of Functionally Graded Hierarchical Soft–Hard Composites. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 1901142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C. W. Apparatus for Production of Three-Dimensional Objects by Stereolithography. 4575330A, August 8, 1984.

- Jemghili, R.; Ait Taleb, A.; Mansouri, K. Additive Manufacturing Progress as a New Industrial Revolution. In IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronics, Control, Optimization and Computer Science (ICECOCS). 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Chohan, J. S. Material-Specific Properties and Applications of Additive Manufacturing Techniques: A Comprehensive Review. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2021 443 2021, 44, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeswari, A.; Christy, E. J. S.; Pius, A. Chapter 5 Biopolymer Blends and Composites: Processing Technologies and Their Properties for Industrial Applications. In Biopolymers and Their Industrial Applications From Plant, Animal, and Marine Sources, to Functional Products; Thomas, S., Gopi, S., Amalraj, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rising, A.; Johansson, J. Toward Spinning Artificial Spider Silk. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, I.; Buehler, M. J. Nanotechnology Nanomechanics of Silk: The Fundamentals of a Strong, Tough and Versatile Material. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 302001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, S. Molecular Recognition in Biomineralization. Nature 1988, 332, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. U. P. A.; Bergmann, K. D.; Boekelheide, N.; Tambutté, S.; Mass, T.; Marin, F.; Adkins, J. F.; Erez, J.; Gilbert, B.; Knutson, V.; Cantine, M.; Ortega Hernández, J.; Knoll, A. H. Biomineralization: Integrating Mechanism and Evolutionary History. Sci. Adv 2022, 8, 9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, N. Assessing the Likelihood of Recurrence during RNA Evolution in Vitro. Artif. Life 2004, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A. J.; Buehler, M. J. A Deep Learning Augmented Genetic Algorithm Approach to Polycrystalline 2D Material Fracture Discovery and Design. Appl. Phys. Rev 2021, 8, 41414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Qiao, D.; Zhao, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, B.; Xie, F. 3D Printing to Innovate Biopolymer Materials for Demanding Applications: A Review. Mater. Today Chem. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Yu, S.; Sun, J. Current Advances and Future Perspectives of 3D Printing Natural-Derived Biopolymers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tochampa, W.; Kongbangkerd, T. Extraction and Properties of Cellulose from Banana Peels. Suranaree J. Sci. Technol. 2014, 21, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, D. M.; De Lacerda Bukzem, A.; Ascheri, D. P. R.; Signini, R.; De Aquino, G. L. B. Microwave-Assisted Carboxymethylation of Cellulose Extracted from Brewer’s Spent Grain. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 131, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, H. Facile Extraction of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Wood Using Ethanol and Peroxide Solvothermal Pretreatment Followed by Ultrasonic Nanofibrillation. Green Chem 2015, 00, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambli, N.; Basak, S.; Samanta, K. K.; Deshmukh, R. R. Extraction of Natural Cellulosic Fibers from Cornhusk and Its Physico-Chemical Properties. Fibers Polym. 2016, 17, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, X.; Sandler, N.; Willför, S.; Xu, C. Three-Dimensional Printing of Wood-Derived Biopolymers: A Review Focused on Biomedical Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5663–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, L.; Manikanika. Extraction of Cellulosic Fibers from the Natural Resources: A Short Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 48, 1265–1270. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, F.; Grénman, H.; Spoljaric, S.; Seppälä, J.; Eriksson, J. E.; Willför, S.; Xu, C. Development of Nanocellulose Scaffolds with Tunable Structures to Support 3D Cell Culture. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 148, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, M.; Sardon, H.; Mecerreyes, D. Ionic Liquids and Cellulose: Dissolution, Chemical Modification and Preparation of New Cellulosic Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 11922–11940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Cheng, T.; Duan, C.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, W.; Zou, X.; Aspler, J.; Ni, Y. 3D Printing Using Plant-Derived Cellulose and Its Derivatives: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 203, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, G.; Kokkinis, D.; Libanori, R.; Hausmann, M. K.; Gladman, A. S.; Neels, A.; Tingaut, P.; Zimmermann, T.; Lewis, J. A.; Studart, A. R. Cellulose Nanocrystal Inks for 3D Printing of Textured Cellular Architectures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M. J.; Dyanti, N.; Mokhena, T.; Agbakoba, V.; Sithole, B. Design and Development of Cellulosic Bionanocomposites from Forestry Waste Residues for 3D Printing Applications. Mater. 2021, 14, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, T.; Suzuki, N. Isolation of Collagen from Fish Waste Material - Skin, Bone and Fins. Food Chem. 2000, 68, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorzai, S.; Casparus; Verbeek, J. R.; Mark; Lay, C.; Swan, J. Collagen Extraction from Various Waste Bovine Hide Sources. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 5687–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, R.; Ghosh, P.; Appapalam Selvakumar, T.; Shanmugavel, M.; Gnanamani, A. Poultry Spent Wastes: An Emerging Trend in Collagen Mining. Adv Tissue Eng Regen Med 2020, 6, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoulders, M. D.; Raines, R. T. Collagen Structure and Stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, M. G.; Jaasma, M. J.; O’Brien, F. J. The Effect of Dehydrothermal Treatment on the Mechanical and Structural Properties of Collagen-GAG Scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 89, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Shimizu, K.; Hara, M. Dynamic Viscoelastic Properties of Collagen Gels with High Mechanical Strength. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 3230–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantides, N.; Wang, L.; Pruiksma, T.; Siemiatkoski, J.; Dugopolski, C.; Shortkroff, S.; Kennedy, S.; Bonassar, L. J. Correlating Rheological Properties and Printability of Collagen Bioinks: The Effects of Riboflavin Photocrosslinking and PH. Biofabrication 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratesteffen, H.; Köpf, M.; Kreimendahl, F.; Blaeser, A.; Jockenhoevel, S.; Fischer, H. GelMA-Collagen Blends Enable Drop-on-Demand 3D Printablility and Promote Angiogenesis. Biofabrication 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J.; Kim, Y. B.; Ahn, S. H.; Lee, J. S.; Jang, C. H.; Yoon, H.; Chun, W.; Kim, G. H. A New Approach for Fabricating Collagen/ECM-Based Bioinks Using Preosteoblasts and Human Adipose Stem Cells. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsoud, M. M. A.; Kady, E. M. El. Current Trends in Fungal Biosynthesis of Chitin and Chitosan. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, G.; Moovendhan, M.; Arasukumar, B.; Gunalan, B. Chemical Composition, Structural Features, Surface Morphology and Bioactivities of Chitosan Derivatives from Lobster (Thenus Unimaculatus ) Shells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trung, T. S.; Tram, L. H.; Van Tan, N.; Van Hoa, N.; Minh, N. C.; Loc, P. T.; Stevens, W. F. Improved Method for Production of Chitin and Chitosan from Shrimp Shells. Carbohydr. Res. 2020, 489, 107913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumayan, E. G.; Gumayan, E. G.; Dimzon, I. K. D.; Guerrero, R. A. Chitosan from Crab Shell Waste for Soft Lithography of Bioplastic Diffraction Gratings. Appl. Opt. Vol. 62, Issue 10, pp. 2487-2492 2023, 62, 2487–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.; Ferreira, I. C.; Torres, C. A. V.; Neves, L.; Freitas, F. Chitinous Polymers: Extraction from Fungal Sources, Characterization and Processing towards Value-Added Applications. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Bhuiyan Rahman, M. A.; Islam, N. M. Chitin and Chitosan: Structure, Properties and Applications in Biomedical Engineering. J Polym Env. 2017, 25, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengíbar, M.; Miralles, B.; Acosta, N.; Aranaz, I.; Harris, R.; Paños, I.; Acosta, N.; Galed, G.; Heras, Á. Functional Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan. Curr. Chem. Biol. 2009, 3, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghormade, V.; Pathan, E. K.; Deshpande, M. V. Can Fungi Compete with Marine Sources for Chitosan Production? Int J Biol Macromol 2017, 104, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, M.; McConnell, M.; Cabral, J.; Ali, M. A. Chitosan Hydrogels in 3D Printing for Biomedical Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya, M.; Vahabi, H.; Barletta, M.; Laheurte, P.; Langlois, V. Additive Manufacturing of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) Biopolymers: Materials, Printing Techniques, and Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 127, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laycock, B.; Halley, P.; Pratt, S.; Werker, A.; Lant, P. The Chemomechanical Properties of Microbial Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 536–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, P. A. Biologically Produced (R)-3-Hydroxy- Alkanoate Polymers and Copolymers. In Developments in Crystalline Polymers; 1988; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnicourt, E.; Cinelli, P.; Lazzeri, A.; Alvarez, V. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): Review of Synthesis, Characteristics, Processing and Potential Applications in Packaging. eXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2014, 8, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V. C.; Singh Patel, S. K.; Shanmugam, R.; Lee, J. K. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Trends and Advances toward Biotechnological Applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Koelling, K.; Vodovotz, Y. Assessment of PHB with Varying Hydroxyvalerate Content for Potential Packaging Applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, P.; Ray, S.; Kalia, V. C. Challenges and Opportunities for Customizing Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Indian J. Microbiol. 2015, 55, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Chen, G. Q. Grand Challenges for Industrializing Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Deng, S.; Chen, P.; Ruan, R. Polylactic Acid (PLA) Synthesis and Modifications: A Review. Front. Chem. China 2009, 4, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D. G.; Langer, R. Physical and Mechanical Properties of PLA, and Their Functions in Widespread Applications-A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoj, A.; Chandra Panda, R. Biodegradable Filament for Three-Dimensional Printing Process: A Review. Eng. Sci. 2022, 18, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savioli Lopes, M.; Jardini, A. L.; Maciel Filho, R. Poly (Lactic Acid) Production for Tissue Engineering Applications. Procedia Eng. 2012, 42, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S. R.; Samykano, M.; Selvamani, S. K.; Ngui, W. K.; Kadirgama, K.; Sudhakar, K.; Idris, M. S. 3D Printing: Overview of PLA Progress. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2059, 020015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, K.; Masek, A. Green Copolymers Based on Poly(Lactic Acid)—Short Review. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoodi, A.; Zadeh, H. H.; Joupari, M. D.; Sahebalzamani, M. A.; Khani, M. R.; Shahabi, S. Physicochemical- and Biocompatibility of Oxygen and Nitrogen Plasma Treatment Using a PLA Scaffold. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 125205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popelka, A.; Abdulkareem, A.; Mahmoud, A. A.; Nassr, M. G.; Al-Ruweidi, M. K. A. A.; Mohamoud, K. J.; Hussein, M. K.; Lehocky, M.; Vesela, D.; Humpolíček, P.; Kasak, P. Antimicrobial Modification of PLA Scaffolds with Ascorbic and Fumaric Acids via Plasma Treatment. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2020, 400, 126216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taib, N. A. A. B.; Rahman, M. R.; Huda, D.; Kuok, K. K.; Hamdan, S.; Bakri, M. K. Bin; Julaihi, M. R. M. Bin; Khan, A. A Review on Poly Lactic Acid (PLA) as a Biodegradable Polymer. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 1179–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, Z. The Reinforcing Effect of Lignin-Containing Cellulose Nanofibrils in the Methacrylate Composites Produced by Stereolithography. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 2968–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Dehne, T.; Krüger, J. P.; Hondke, S.; Endres, M.; Thomas, A.; Lauster, R.; Sittinger, M.; Kloke, L. Photopolymerizable Gelatin and Hyaluronic Acid for Stereolithographic 3D Bioprinting of Tissue-Engineered Cartilage. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater. 2019, 107, 2649–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopova, T. A.; Demina, T. S.; Cherkaev, G. V.; Khavpachev, M. A.; Bardakova, K. N.; Grachev, A. V.; Vladimirov, L. V.; Zelenetskii, A. N.; Timashev, P. S. Solvent-Free Synthesis and Characterization of Allyl Chitosan Derivatives. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 20968–20975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foli, G.; Degli Esposti, M.; Morselli, D.; Fabbri, P. Two-Step Solvent-Free Synthesis of Poly(Hydroxybutyrate)-Based Photocurable Resin with Potential Application in Stereolithography. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandanamsamy, L.; Harun, W. S. W.; Ishak, I.; Romlay, F. R. M.; Kadirgama, K.; Ramasamy, D.; Idris, S. R. A.; Tsumori, F. A Comprehensive Review on Fused Deposition Modelling of Polylactic Acid. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaunier, L.; Guessasma, S.; Belhabib, S.; Della Valle, G.; Lourdin, D.; Leroy, E. Material Extrusion of Plant Biopolymers: Opportunities & Challenges for 3D Printing. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 21, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecen, B. FDM-Based 3D Printing of PLA/PHA Composite Polymers. Chem. Pap. 2023, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkaseer, A.; Jia, K.; Chen, Y.; Chen, K. J.; Janhsen, J. C.; Refle, O.; Hagenmeyer, V.; Scholz, S. G. Material Jetting for Advanced Applications: A State-of-the-Art Review, Gaps and Future Directions. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 60, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hou, S.; Hao, D.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Zu, G.; Huang, J. Food-Based Highly Sensitive Capacitive Humidity Sensors by Inkjet Printing for Human Body Monitoring. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater 2021, 2021, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. M.; Suen, S. K. Q.; Ng, W. L.; Ma, W. C.; Yeong, W. Y. Bioprinting of Collagen: Considerations, Potentials, and Applications. Macromol. Biosci. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nganga, S.; Moritz, N.; Kolakovic, R.; Jakobsson, K.; Nyman, J. O.; Borgogna, M.; Travan, A.; Crosera, M.; Donati, I.; Vallittu, P. K.; Sandler, N. Inkjet Printing of Chitlac-Nanosilver—a Method to Create Functional Coatings for Non-Metallic Bone Implants. Biofabrication 2014, 6, 041001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. K.; Agar, D. A.; Rudolfsson, M.; Larsson, S. H. A Review on Wood Powders in 3D Printing: Processes, Properties and Potential Applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, L.; Tao, S. Preparation of Hybrid Chitosan Membranes by Selective Laser Sintering for Adsorption and Catalysis. Mater. Des. 2019, 173, 107780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalcik, A. Recent Advances in 3D Printing of Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Review. EuroBiotech J. 2021, 5, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zeng, B.; Han, Y.; Dai, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, F. Preparation and Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Composite Microspheres Consisting of Poly(Lactic Acid) and Nano-Hydroxyapatite. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Guan, J.; Alido, J.; Hwang, H. H.; Yu, R.; Kwe, L.; Su, H.; Chen, S. Mitigating Scattering Effects in Light-Based Three-Dimensional Printing Using Machine Learning. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani Dabbagh, S.; Ozcan, O.; Tasoglu, S. Machine Learning-Enabled Optimization of Extrusion-Based 3D Printing. Methods 2022, 206, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsanya, M.; Isichei, J.; Parupelli, S. K.; Desai, S.; Cai, Y. In-Situ Droplet Monitoring of Inkjet 3D Printing Process Using Image Analysis and Machine Learning Models. Procedia Manuf. 2021, 53, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ye, J.; Silva Izquierdo, D.; Vinel, A.; Shamsaei, N.; Shao, S. A Review of Machine Learning Techniques for Process and Performance Optimization in Laser Beam Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A. J.; Buehler, M. J. Encoding and Exploring Latent Design Space of Optimal Material Structures via a VAE-LSTM Model. Forces Mech. 2021, 5, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A. J.; Jin, K.; Buehler, M. J. Architected Materials for Mechanical Compression: Design via Simulation, Deep Learning, and Experimentation. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A. J.; Buehler, M. J. Single-Shot Forward and Inverse Hierarchical Architected Materials Design for Nonlinear Mechanical Properties Using an Attention-Diffusion Model. Mater. Today 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Roach, D. J.; Wu, J.; Hamel, C. M.; Ding, Z.; Wang, T.; Dunn, M. L.; Qi, H. J. Advances in 4D Printing: Materials and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthe, L. P.; Pickering, K.; Gauss, C. A Review of 3D/4D Printing of Poly-Lactic Acid Composites with Bio-Derived Reinforcements. Compos. Part C Open Access 2022, 8, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, M.; Le Guen, M. J.; Mcdonald-Wharry, J.; Bridson, J. H.; Pickering, K. L. Quantifying the Shape Memory Performance of a Three-Dimensional-Printed Biobased Polyester/Cellulose Composite Material. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 8, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Structurally Dynamic Gelatin-Based Hydrogels with Self-Healing, Shape Memory, and Cytocompatible Properties for 4D Printing. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J. W.; Shin, S. R.; Park, Y. J.; Bae, H. Hydrogel Production Platform with Dynamic Movement Using Photo-Crosslinkable/Temperature Reversible Chitosan Polymer and Stereolithography 4D Printing Technology. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2020, 17, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou, A.; Castro, M.; Bevan, R.; Martin, N. 3D Printing of Wood Fibre Biocomposites: From Mechanical to Actuation Functionality. Mater. Des. 2016, 96, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, V.; Agarwal, P.; Srinivasan, V.; Panwar, A.; Vasanthan, K. S. Facet of 4D Printing in Biomedicine. J. Mater. Res. 2023, 38, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, C. M.; Roach, D. J.; Long, K. N.; Demoly, F.; Dunn, M. L.; Qi, H. J. Machine-Learning Based Design of Active Composite Structures for 4D Printing. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 065005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A. 3D Bioprinting Applications for the Printing of Skin: A Brief Study. Sensors Int. 2021, 2, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, L.; Kuhn, S.; Sorg, H.; Gruene, M.; Schlie, S.; Gaebel, R.; Polchow, B.; Reimers, K.; Stoelting, S.; Ma, N.; Vogt, P. M.; Steinhoff, G.; Chichkov, B. Laser Printing of Skin Cells and Human Stem Cells. Tissue Eng. - Part C Methods 2009, 16, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Wang, L.; Ji, D.; Ren, M.; Ke, D.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Yang, X. Fabrication of SA/Gel/C Scaffold with 3D Bioprinting to Generate Micro-Nano Porosity Structure for Skin Wound Healing: A Detailed Animal in Vivo Study. Cell Regen. 2022, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, M.; Song, F.; Feng, C.; Liu, H. Simple and Robust 3D Bioprinting of Full-Thickness Human Skin Tissue. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 10087–10097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatt, L. P.; Thompson, K.; Helms, J. A.; Stoddart, M. J.; Armiento, A. R. Clinically Relevant Preclinical Animal Models for Testing Novel Cranio-Maxillofacial Bone 3D-Printed Biomaterials. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campana, V.; Cardona, V.; Vismara, V.; Monteleone, A. S.; Piazza, P.; Messinese, P.; Mocini, F.; Sircana, G.; Maccauro, G.; Saccomanno, M. F. 3D Printing in Shoulder Surgery. Orthop. Rev. (Pavia). 2020, 12 (Suppl 1), 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Johnson, B. N.; Jia, X. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printed Scaffold and Material Selection for Bone Repair. Acta Biomater. 2019, 84, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bie, H.; Chen, H.; Shan, L.; Tan, C. Y.; Al-Furjan, M. S. H.; Ramesh, S.; Gong, Y.; Liu, Y. F.; Zhou, R. G.; Yang, W.; Wang, H. 3D Printing and Performance Study of Porous Artificial Bone Based on HA-ZrO2-PVA Composites. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chocholata, P.; Kulda, V.; Babuska, V. Fabrication of Scaffolds for Bone-Tissue Regeneration. Materials (Basel). 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadid, M.; Oved, H.; Silberman, E.; Dvir, T. Bioengineering Approaches to Treat the Failing Heart: From Cell Biology to 3D Printing. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menasché, P.; Vanneaux, V.; Hagège, A.; Bel, A.; Cholley, B.; Parouchev, A.; Cacciapuoti, I.; Al-Daccak, R.; Benhamouda, N.; Blons, H.; Agbulut, O.; Tosca, L.; Trouvin, J. H.; Fabreguettes, J. R.; Bellamy, V.; Charron, D.; Tartour, E.; Tachdjian, G.; Desnos, M.; Larghero, J. Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell–Derived Cardiovascular Progenitors for Severe Ischemic Left Ventricular Dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupfer, M. E.; Lin, W. H.; Ravikumar, V.; Qiu, K.; Wang, L.; Gao, L.; Bhuiyan, D. B.; Lenz, M.; Ai, J.; Mahutga, R. R.; Townsend, D.; Zhang, J.; McAlpine, M. C.; Tolkacheva, E. G.; Ogle, B. M. In Situ Expansion, Differentiation, and Electromechanical Coupling of Human Cardiac Muscle in a 3D Bioprinted, Chambered Organoid. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Yu, Q.; Hou, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Li, R. Additive Manufacturing of Nerve Guidance Conduits for Regeneration of Injured Peripheral Nerves. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosshauer, B.; Dreesmann, L.; Schaller, H. E.; Sinis, N. Synthetic Nerve Guide Implants in Humans: A Comprehensive Survey. Neurosurgery 2006, 59, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petcu, E. B.; Midha, R.; McColl, E.; Popa-Wagner, A.; Chirila, T. V.; Dalton, P. D. 3D Printing Strategies for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Biofabrication 2018, 10, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y. 3D Printing and Bioprinting Nerve Conduits for Neural Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z.; Ko, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Fang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z.; Ko, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Center, B. 3D Printed Conductive Multiscale Nerve Guidance Conduit with Hierarchical Fibers for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Adv. Sci. 2023, 2205744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y.; Feng, Y.-H.; Feng, Q.-B.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Zhong, L.; Liu, P.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.-R.; Chen, X.-Y.; Zhou, L.-X. Low-Temperature 3D-Printed Collagen/Chitosan Scaffolds Loaded with Exosomes Derived from Neural Stem Cells Pretreated with Insulin Growth Factor-1 Enhance Neural Regeneration After Traumatic Brain Injury. : Neural Regeneration Research. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).