1. Introduction

Outcomes for cats in municipal animal management facilities (council pounds) and animal welfare shelters are considerably worse than for dogs in most countries where straying and nuisance cats are impounded by authorities [

1]. Return-to-owner rates are usually much lower than for dogs because few impounded cats are identified with a microchip or tag [

1]. Because of overcrowding in pounds and shelters, timid or fearful cats and young kittens are often euthanized on admission [

2]. Across Australia, approximately 33% of cats entering shelters and pounds are euthanized, with the worst-performing quartile of local governments euthanizing 67% to 100% of cats [

2]. Euthanasia of animals, particularly healthy and treatable animals, has adverse effects on the psychological health of the staff involved [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Many stray cats in urban areas are semi-owned and are provided regular food by people who do not perceive the cat as their property [

7]. In Australia, 3-9% of adults feed daily one or more cats they do not perceive they own, and they feed an average of 1.5 cats [

8,

9]. Most are not sterilized and are a substantial source of unwanted kittens. Many of these cats are poorly socialized and are timid or fearful, and therefore are at higher risk of euthanasia in a shelter or pound [

10].

In Victoria, local governments (councils) are responsible for domestic cat management and enforcement of state government legislation. Under the Victorian Domestic Animal Act 1994 [

11], cats over three months of age must be microchipped and annually registered with the council they reside in. The Domestic Animals Act 1994 requires councils to pay the State Government Treasurer

$4.16 for every cat registration collected, which is

$108.40 or

$39.00 (2023-24) respectively for an entire or sterilized cat residing in the City of Banyule [

12]. The council is still obligated to pay this mandatory State Government levy to the Treasurer, even if they provide free or discounted registration for residents’ cats. Under the Local Government Act 2020, councils have the power to make local laws to respond to issues and needs in the broader community. In all councils in Victoria, under local law, there are conditions limiting the number of domestic animals to be kept on property without a permit. Typically, an annual permit is required to keep more than two cats. However, this can vary greatly between councils depending on minimum requirements that need to be met, including housing size and type. For example, the City of Banyule requires a permit to be obtained for more than two cats on a property under 4,000 meters, with an annual cost of

$52.50 for two or more cats [

13].

Animal Management Officers (AMOs) are employed by each council to enforce legislation pertaining to the Domestic Animal Act 1994 [

11]. The standard response by AMOs in Victoria following receipt of a call related to a found cat or nuisance complaint comprises a reactive response, typically lending a cat-trap to the complainant or attending the property and trapping the cat. Following trapping, the cat is held at the pound (animal management facility for council) for the legally required timeframe (eight days for a healthy unidentified cat in Victoria) or transferred to a service provider such as an animal welfare organization. If the cat is not reclaimed by an owner within the legal timeframe, it is rehomed or euthanized. This method of cat control (combined with education) has not been effective in addressing cat-related issues, with many local governments recording steady increases in cat-related calls and impoundments over time [

2,

14]. Frequently AMOs can document attending the same properties numerous times over several years, impounding unwanted cats and/or kittens, providing further evidence that current strategies are not working.

Many Victorian councils already provide low-cost or subsidized sterilization programs for cats. There are concerns that these schemes primarily provide a cheaper option for owners who were already going to sterilize their cats [

15]. Sterilization programs need clear goals, targeting the locations that have the highest cat-related complaints and/or shelter and pound intake [

16,

17].

Cat-related calls and impoundments are highest in lower socioeconomic areas [

9,

18,

19]. In these areas, residents who own a cat or are feeding a stray cat they did not actively seek to own, simply cannot afford the costs of sterilizing, microchipping, and registering these cats, particularly if multiple cats are being cared for. In all states in Australia, trap-neuter and return (TNR) is illegal under various legislation relating to abandonment, biosecurity, and containment to property (referred to as leash laws in the USA [

20,

21]. A property owner does have the legal right to humanely trap or catch any nuisance cats on their property. However, cats found to be “at large” on private property must be handed to an authorized officer (AMO) to be impounded at an animal management facility.

AMOs can find enforcement of domestic cat legislation challenging, mainly due to lack of resources and funding to set up effective preventative programs. The lack of effective programs to prevent kitten births, and the resulting high euthanasia rates, has a negative impact on job satisfaction and psychological well-being of AMOs [

3].

The City of Banyule is 19 kilometers from the central business district (CBD) of Greater Melbourne, Victoria and had a population of 134,047 people in 2021 [

22]. Of the 20 suburbs in the city, three are classified as disadvantaged suburbs with Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas [

23] below 1000, and have more social housing than other areas of the city [

24]. These suburbs also had the highest number of cat-related calls to council per 1000 residents. The remaining suburbs have SEIFA indices that range from 1,011 to 1,145 with average of 1,055 (average SEIFA across Australia is 1000) [

23]. Avenues for subsidized sterilization for community pets in Banyule prior to 2013 were limited to the Australian Veterinary Association (AVA) Desexing (sterilization) Voucher Scheme [

25]. This scheme provided residents with a 25% reduction in any advertised sterilization price, which varied between veterinary clinics. Anecdotally, many residents still could not afford to pay for the sterilization of their cat/s.

Historically, the standard practice for cat management in the City of Banyule involved AMOs attending the property and providing trap cages to complainants to trap or AMOs trapped nuisance cats A free surrender service was also provided for domestic animals, which if necessary, incorporated free pick-up of the animal. In 2012-13, the City of Banyule had two full-time AMOs. Trapped cats were transported to the council-contracted animal management facility, the Cat Protection Society (CPS). CPS was located within the City of Banyule, and residents were also able to deliver stray and surrendered cats or kittens directly to the facility. This was at no cost to the residents, but

$80 per cat was charged to council and this increased to

$150 in 2018. The CPS had numerous councils contracted to their facility, none of which had effective programs in place to manage their stray cat populations. This frequently saw the facility at, or over, capacity. Intake was always extreme throughout kitten season, resulting in most kittens under eight weeks of age being euthanized. Due to the number of councils contracting to CPS, the facility was at capacity all year with 90% of the 12,000 cats or kittens impounded in 2011 euthanized [

26].

A catalyst for change to cat management methods in the City of Banyule occurred in 2012. Specifically, considerable negative psychological impacts were experienced by two AMOs who in 2012, were forced to deliver a stray socialized kitten to the contracted animal management facility (CPS), only to have the kitten euthanized on admission because it was under eight weeks of age. That day in 2012, the two AMOs decided there had to be a better way to manage cats and were no longer willing to continue using the standard practice of trapping and euthanizing kittens under eight weeks of age, or cats which appeared unsocial at the time of impound, and cats not reclaimed or rehomed but were otherwise healthy. This method of cat management was clearly not working; many surrendered or stray cats and kittens continued to be collected from the same properties each year, and numerous nuisance cat complaints within the municipality also continued.

A new program for cat management was initiated in response to both the negative psychological impacts on AMOs and shelter staff, and the non-effectiveness of the pre-2013 cat management strategy. The program proposed and approved by the City of Banyule was that sterilization, microchipping and the first year of registration would be funded by the council. The purpose of this program was to increase ownership responsibilities for owned and stray cats being fed by residents (semi-owned cats), and to reduce the breeding of cats, and therefore, the number of cats and kittens killed in the council-contracted facility (CPS). This was provided at no cost for all owned cats and semi-owned cats in the target areas. For the cat to be included in the program, semi-owners were required to take ownership of the cat at the time of sterilization and their contact details were entered into microchip and municipal databases. Free transport was provided if needed for residents’ cats to and from the veterinary clinic. The trial program was implemented in October 2013 and initially targeted three suburbs where council received the highest number of cat-related calls. In addition, any resident of Banyule City adopting a cat through the CPS were eligible for free registration of their cat/s for the first year of ownership (subsidized by the council) to encourage adoptions.

The aim of this report is to document the methods and results of this free sterilization and identification program for owned and semi-owned cats, predominantly targeted to suburbs with high cat-related calls in the City of Banyule, Victoria, and microtargeted within those suburbs to locations of cat-related calls.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Program

Two free sterilization, microchipping, and registration (licensing) programs for owned and semi-owned cats were operated in the City of Banyule (population 124,314 in 2013). The first program started in 2013 and was medium-intensity (sterilized 3.0 cats/1000 residents in first year), and targeted to three disadvantaged suburbs. The program continued until the time of reporting (June 2021), except for two years (2015-2016 and 2016-2017) when it was suspended, and the second city-wide program was initiated (

Table A1). The second program began in 2015-2016, was city-wide, low-intensity (sterilized 1.1 cat/1000 residents in first year city-wide), and initially run twice per year. It was the sole program conducted in that financial year and the following year (2016-2017). From 2019-2021, both programs operated concurrently and continuously throughout the year. with demand decreasing over this period. Both programs incorporated free drop-off and pick up services between one of the sterilization facilities for any resident across the city who did not have the means to transport their cats themselves. Although more intense due to the higher cat-related call rate, in both the three target suburbs and city-wide, microtargeting (also know as the “red flag” model) was used [

27]. If AMOs received a cat-related call to a stray or nuisance cat, they assumed there would be more than one cat and focused efforts around that specific area to enroll cats for sterilization.

The medium-intensity sterilization program targeted three suburbs (population 13,445 (2011) which generated the highest calls to council relating to found and nuisance cats/1000 residents (in 2011-12 calendar years an average of 10.8 calls vs 3.5 calls per year for other suburbs). These suburbs had the lowest socioeconomic status for the city and highest proportion of government (social) housing. Within these three suburbs, further microtargeting focused on specific locations of cat-related calls for found cats and nuisance complaints to council. When the medium-intensity program was recommenced in 2017-18, more intensive microtargeting was conducted by one AMO (JC), and involved revisiting properties with remaining unsterilized cats, that were not enrolled in any previous years.

The low-intensity targeted program began in 2015-2016, continuing to December 2021 and was made available to all residents in the City of Banyule who owned cats. Initially, it was offered twice a year in March/April and again in August, prior to the start of kitten season in spring (around September in Victoria). The aim was to facilitate sterilization of cats before the breeding season to prevent kittens being born. The timing aimed to target kittens born or obtained during the preceding kitten season (September to March). Additionally, this city-wide program involved some microtargeting to locations where cat-related calls emanated from.

2.2. Advertising and Recruitment

In the three suburbs where the medium-intensity targeted program operated, it was promoted and advertised to residents primarily via the AMOs. Areas of concentration included advertising in large government housing estates, local community centers, shopping strips and community noticeboards. Microtargeting was also undertaken by the AMOs using door knocking and flyer drops to locations where stray and surrendered cats and kittens repeatedly originated, and to locations from which cat-related calls to council emanated. Prior local knowledge of the AMOs and their relationships with the community played a large part in public engagement with the program, particularly communities in the microtargeted areas. The AMOs responded to residents’ requests for assistance for cat-related issues by attending addresses and enrolling owned and semi-owned cats into the free desexing program. Further advertising of the targeted program in the three suburbs in 2013 was undertaken by AMO (author JC) preparing the flyers, media articles and material for door knocks, the council newsletter and social media, in conjunction with council’s communication officer and was conducted in the same manner through to 2020- 2021.

Advertisements for the medium-intensity, microtargeted program, encouraged residents who were feeding stray cats or kittens or who had acquired a new cat or kitten that was not sterilized, to call the council office to enroll their cat/s in the program. In addition, to maximize recruitment, the AMOs capitalized on existing relationships with employees of external organizations who were active in the community; they were contacted to assist by referring residents to the program. These organizations’ employees included social workers from the local community centers and other organizations, the Victorian police, and inspectors from the Royal Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA).

In contrast, the low-intensity city-wide program was advertised to all residents via the council newsletter that was distributed to every household twice a year, and the council’s Facebook page. As the program only operated twice yearly between 2015-16 and 2016-17 (

Table A1), a waitlist was developed for the months in between programs, to ensure that cats/kittens requiring sterilization were identified and not missed. In the city-wide program, at locations where complaints related to nuisance cats were received, AMOs engaged in some microtargeted advertising of the free sterilization program by door knocking and flyer drops.

2.3. Complaint Handling

Prior to 2017-18, any resident who lodged a cat-related complaint with the council elicited a reactive response; a trap was delivered by an AMO to the complainant’s property, and trapping would generally commence that night. This single-pronged approach changed in 2017-18, whereby if a complaint was received by council, the trapping process was not commenced until eight days later. The immediate response changed to that of a proactive approach, and an AMO would contact the complainant, gathering further information regarding the issue, including the location of the offending cat. If an address was known, the AMO would attend the property and speak with the cat owner/ carer, assessing the cat situation and enrolling any cat/s into the program if they were entire and/or not microchipped and/or not registered. Owners and semi-owners were encouraged to enroll their cats into the program before action to trap any offending cat/s was undertaken. Educating owners and semi-owners, and enrolling their cats in the desexing program was the highest priority, rather than trapping and impounding the offending cat.

If the complainant could not identify the offending cat owner, a letterbox drop of a “notification of cat trapping” was conducted around the vicinity of the complainant’s address. This letter provided notice of seven days to rectify any issues with cats and included information relating to the legislative requirements pertaining to cats, especially the requirement that pet cats be contained to the owners’ property. Residents were also provided information on the free sterilization, microchipping and registration program provided by council. The complainant was notified of this impending trapping action. If the problem persisted after seven days, the AMO would return with a trap, assess the best trapping location, provide guidelines and instruction to the complainant on setting the trap at night (trapping instruction was this only took place at night), and processes to check the trap and contact council first thing in the morning if a cat had been trapped, so that collection was expedient. In cases where there were several cats, resulting in numerous complaints from one area, in these cases the AMO would attend the property in the morning and check the traps, transporting multiple cats if required. The trapping notification letter stated if any trapped cat was wearing visible identification, it would be returned to the owner, bypassing the pound [

28].

2.4. Bookings

Residents responding by phone to the public flyer or council newsletter would reach the council’s customer service center and provide their contact details. This information would be emailed to the AMO (author JC), who would call the resident to obtain additional information about the cat/cats to be enrolled. This not only provided an opportunity to enroll cats in the program, but importantly, gave an opportunity to build rapport and ask questions relating to the cat/cats, for example, were they owned or semi-owned, how many did they have and any other pertinent information. Direct enrolments were also made in the field by the AMO’s when interacting with residents as part of their positional duties.

Sterilization surgeries in 2013 and 2014 were performed by the RSPCA in their mobile clinic, from 2015 by two participating veterinary clinics, and then from 2018-2021 one private veterinary clinic and the veterinary clinic associated with the contracted animal welfare facility Cat Protection Society (CPS). According to location of the resident, the cat and carer/owner information was emailed to the veterinary clinic by the AMOs. Each clinic would call the resident directly to schedule the cat/s for surgery. This procedure and booking system remained in place throughout the entire program until final data collection in December 2021.

No limitations were placed on how many cats could be sterilized per resident or household, nor any specific limiting criteria set for residents to enroll cat/cats. Whilst the program was advertised city-wide as being available during a two-week period twice yearly, in practicality it took longer for the veterinary clinics to complete all scheduled sterilizations. On occasion when a resident failed to present their cat/s for scheduled sterilization, a follow-up property visit by the AMO was undertaken, along with the veterinary clinic attempting to contact the resident by phone to reschedule the sterilization.

2.5. Sterilization Surgeries

From October 2013 to August 2014, surgeries were undertaken by an RSPCA mobile veterinary clinic located centrally within the targeted suburbs. It was staffed with a team of veterinary nurses and two veterinarians. A free cat transportation service was provided by AMOs for any resident who had limited or no transport, to minimize the barriers for cats to be sterilized.

Learnings from the 2013 program resulted in a change to scheduling of services in 2014. Firstly, female cats required longer anesthetic recovery time than the males, and as all cats were being discharged the same day to recover at home, the females were scheduled for sterilization in the morning and males in the afternoon. Females who were heavily pregnant on arrival at the mobile clinic were not sterilized at that time, but were sterilized along with the kittens, when eligible.

In 2013, non-dissolvable external skin sutures were used for female cat sterilizations, and AMOs would attend home properties to remove the sutures 10 days after surgery. This proved to be a challenge with poorly socialized semi-owned and owned cats, as even with good cat-handling skills, it was difficult to achieve effective restraint for suture removal. In 2014, dissolvable external skin sutures were utilized, and Elizabethan collars sent home with cats to minimize potential suture/wound issues.

Complications associated with the surgeries arising after-hours, typically issues with sutures, were referred to local veterinary clinics for management. As a result, it was agreed to be more appropriate to utilize local veterinarians to undertake the sterilizations, who could then respond to any issues that arose after-hours. Two local veterinary clinics located in the south of the municipality in the vicinity of the three target suburbs agreed to participate in the sterilization program from 2015. Both clinics had existing relationships with council for emergency treatment of stray animals. Thus, they had an existing rapport with AMOs and cat rescue groups within the area and were eager to support the program.

Between 2018-2021, sterilization surgeries were undertaken by a single original veterinary clinic in the south of the municipality, and the veterinary clinic associated with CPS located in the north of the municipality. Having northern and southern clinics made transport easier for residents across the municipality, but transportation remained available to any resident who had limited or no transportation.

Cat traps were sometimes needed to capture poorly socialized semi-owned cats which were unable to be handled. This required flexibility of both the veterinary clinic when scheduling the sterilization procedure, and the AMO to provide transportation. The clinics on occasion needed to reschedule surgeries to fit in with the trapping process, to prioritize the cat’s welfare, and limit time in a trap to reduce stress on the cat.

In late 2018, the council service agreement with the animal management facility (CPS) was renewed for a three-year period. The new agreement included a price increase for the mandated eight-day minimal hold for a cat or kitten from $80 to $150. The increase in price negatively impacted council, because it applied to all stray cats and kittens impounded directly by an AMO or directly by a resident, as well as any cat or kitten surrendered by a resident. To compensate for the increased service costs that occurred without warning or future budget planning for council, 200 free sterilization surgeries at CPS were negotiated by one AMO (JC) for residents’ cats enrolled in the free cat desexing program.

2.6. Resources

From 2013 to 2017, two full-time AMOs were available to liaise with residents and staff to schedule surgeries and transport cats to and from the mobile RSPCA Veterinary Clinic (2013-14) or the two veterinary clinics (2015-2018) using council vehicles equipped for animal transport. The AMOs also conducted door knocking, letterbox flyer drops and liaised with all external organizations. The AMOs operated this program whilst maintaining all other usual day-to-day cat- and dog-related calls and impounds. From 2018 to 2021, one full-time AMO (JC) was available for liaising with residents and veterinary clinics, scheduling surgeries, and if needed, there was a second AMO to assist with transporting cat/s for surgery. From 2015 to 2021, most residents were able and willing to transport the cat/s to the veterinary clinics.

2.7. Costs

The average cost of sterilizations to the City of Banyule was

$105 per cat/kitten (80 cats @

$175 charged by RSPCA, 648 cats @

$108 charged by local vets, and 103 free sterilizations were utilized out of the 200 free sterilizations agreed to by CPS) A total of 831 cats were sterilized over the eight years of the program (

Table A1).

The calculated cost of a cat-related complaint was based on estimated costs to Animal Management Services of

$290 per cat-related call that was acted on by attending the property, trapping the offending cat and delivering the cat to CPS. This was based on 1 hour per call for a customer service officer to take the call (Band 4A wage of

$32.80 per hour), 1h (@

$38.89/h) for local laws administration to process the call, 3.67 hours of AMO time (Band 5A wage of

$35.89 per hour; Banyule Enterprise Bargaining Agreement 2017-2021) to attend the property on average three times (total labor costs

$203.33). Vehicle costs at 40 kms round trip (three trips totaling 120km at

$0.72/km;

Table A2) [

29]. Calculations took into consideration when the call was first logged at council with a customer service officer, then transferred to the local laws team, and included time from initial AMO contact to all actions associated with the complaint, including but not limited to, initial phone contact with the resident, travel time and fuel, site visits, trapping and impounding a cat. In addition, there were costs charged to the City of Banyule under their agreement with CPS, and were associated with care in the animal management facility for the eight-day mandated hold period (initially

$80 per cat increasing to

$150). The same costs applied to the council for any cat/ kitten directly surrendered by the owner, or a stray brought by a resident. The Cat Protection Society also incurred costs associated with either euthanasia or veterinary care, sterilization, microchipping and rehoming the cat after the eight-day hold, and these were not charged to the council.

2.8. Data Management and Analysis

Data for cat-related calls was routinely recorded by the council and obtained directly from council records within the customer request management system between 2011-21. Impound data for cats from 2011 to 2021 was obtained from the council impound register, maintained by administration officers directly within the animal management department. Data for owner-surrendered cats and stray cats brought directly to the shelter was routinely collected by CPS. However, they were only available from CPS from 2017-2021 and were based on electronic records, because paper records prior to 2017 were destroyed at the time of transferring to electronic records. Data for cats being sterilized in the program was collected by customer service officers, initially, then further data collected by the AMOs. For values shown per 1000 residents, Australian Census data from 2011, 2016 and 2021 were used for the population year in which they were collected, and the following three years until the next census data were available (

Table A1) [

22].

Ancillary statistical analyses were conducted for two time periods. Firstly, to explore changes over the entire program, 2012-2013 values for the number of cats impounded, reclaimed, rehomed and euthanized and percentage of impounded cats that were rehomed were used as a baseline for analyses by financial year through to 2020-2021, and the average of 2011 and 2012 values for cat-related calls and costs were used as a baseline for analyses by calendar year through to 2021 [

22]. Secondly, to explore changes over time after the city-wide and targeted-area programs were run concurrently, 2016-2017 was used as a baseline for analyses by financial year through to 2020-2021 and 2016 as a baseline for analyses by calendar year through to 2021. Kendall’s tau was used to measure the strength of the relationship between year and the same set of variables. Where data was available at both city-wide and targeted-area levels, analyses were conducted separately for each level. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 18.0 [

30]. Results are shown in

Table A3.

4. Discussion

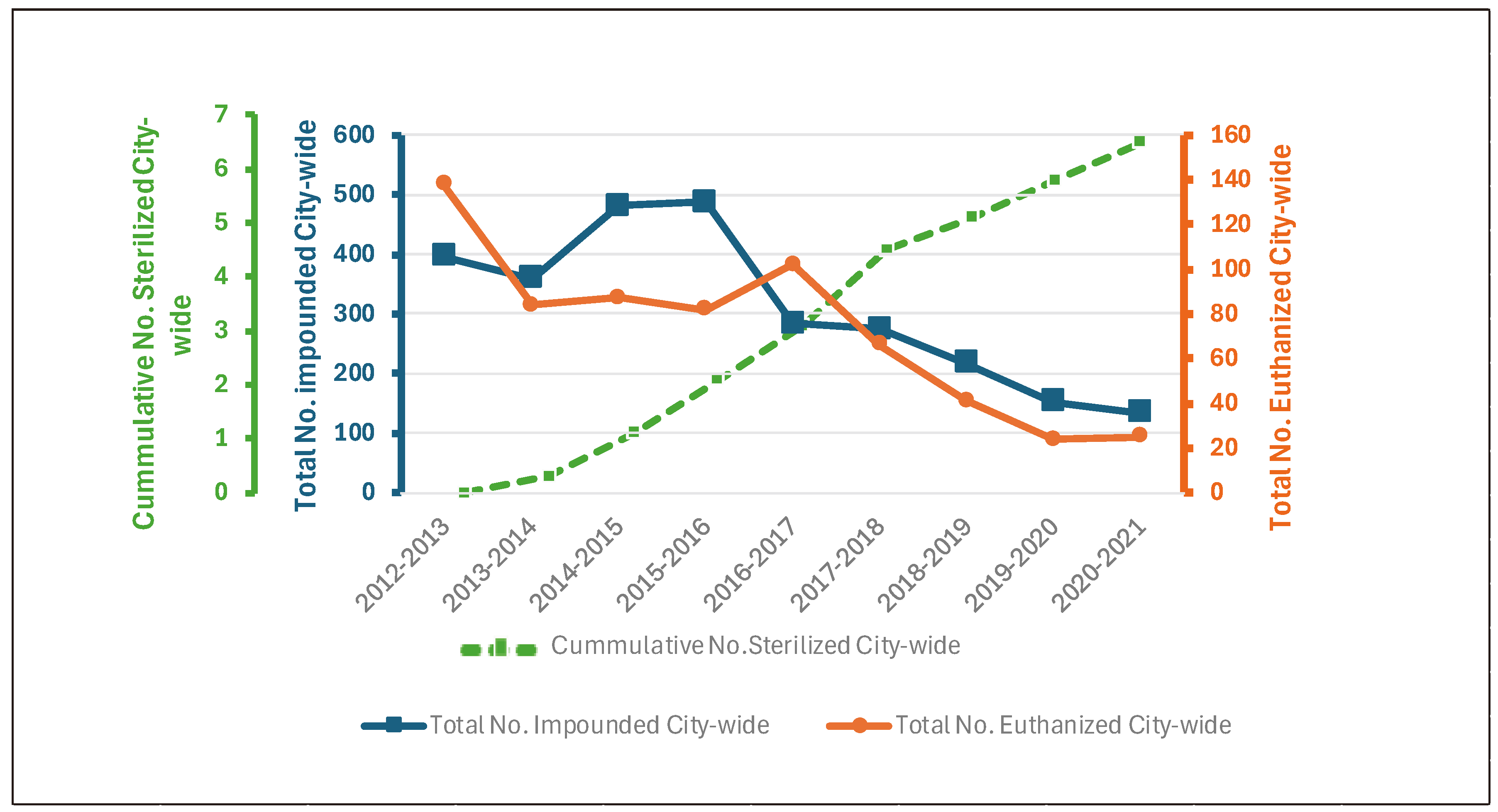

The City of Banyule (population 123,384) implemented a free sterilization, microchipping and registration program in October 2013 for cats that were owned or stray cats cared for by residents (semi-owners). The aim was to trial a new way to manage cat-related issues instead of continuing solely with a traditional trap-adopt-or-kill policy. Whilst the cat trapping continued, the focus shifted from immediately providing a cat trap and trapping the nuisance cat to attending the property of the cat owner and discussing the complaint lodged, and if possible, enrolling the offending cat and any other entire cats into the sterilization program. Initially, a medium-intensity program (3.0 cats sterilized/1000 residents) was implemented in three suburbs with the highest numbers of impounded cats and cat-related calls to council and was microtargeted to the location of calls related to nuisance cats and found cats. Transportation was offered for residents unable to transport the cats they were caring for. In 2014-15, a low-intensity city-wide program (1.1 cat sterilized/1000 residents) was implemented, and the targeted program suspended until 2017-18, when both programs operated concurrently. Over the eight years, a cumulative total of 33 cats/1000 residents were sterilized in the three target suburbs and 6.5 cats/1000 residents city-wide. Key findings were that city-wide, there were decreases in impoundments by 66%, euthanasia by 82%, cat-related calls by 36% and total cost savings to council were estimated at $266,225.00.

4.1. Cats Sterilized and Impoundments

Over the eight-year sterilization program, cat sterilizations averaged 4.1 cats/1000 residents in the three target suburbs, resulting in a 66% decrease in impounded cats. In the three years following the reinstitution of the medium-intensity program targeted to the three suburbs, impoundments decreased by 51% and total intake into the shelter from the city of Banyule, including owner-relinquished cats and stray cats brought in by members of the public, decreased by 42% from 6.2 to 3.6 cats/1000 residents, compared to the average for Victoria of 7.2 cats/1000 residents [

2]. Owner-relinquished cats also decreased by 50%, and the number of stray cats brought by the public to the receiving shelter (CPS) decreased by 28% in the same period.

This three-year reduction in intake of 42% is consistent with reports from six cities in the USA ranging in population from 200,000 to 1.8 million where an average of 5.4 cats/1000 residents were sterilized each year over three years, and shelter intake decreased by a median of 32% [

31]. The greatest decrease in intake occurred in Columbus which implemented the ‘red flag” model where animal control officers utilized prior knowledge of “hot-spot” areas to target sterilizations, reducing intake by 45% [

27] This was similar to the method used in Banyule where AMOs microtargeted locations known to be a source of impounded cats and kittens and cat-related complaints.

A higher intensity program in Florida that did not focus on microtargeting, sterilized 60 cats/1000 residents per year for two years and achieved a 30% decrease in shelter intake in the first year and 66% over the two years [

32]. This compares favorably to our 51% reduction over three years for all cats entering the CPS facility from the target area after sterilizing an average of 4.1 cats/1000 residents using a microtargeted approach. In Florida, a total of 2366 cats were sterilized over the two years, and 52% were returned to the original location or relocated to other sites after sterilization (TNR), whereas 47% were sterilized and adopted or transferred to a rescue group, and were not included in the shelter intake in the target area [

32].

Based on data from our study, resolving complaints by providing the owner or semi-owner whose cats were a source of complaints an opportunity to sterilize the cats they were caring for at no cost, rather than immediately deploying traps as traditionally done, is an effective way to reduce shelter intake of cats. It is consistent with an assistive approach rather than traditional punishment-orientated animal control, and is aligned with the One Welfare philosophy which aims to balance and optimize the well-being of humans, animals, and the environment [

33].

Key differences between the Banyule program and the programs described in the 6 US cities [

31] and in Florida [

32] were that cats in USA were sterilized and returned to their outside homes without the carer being required to take ownership of the cats, commonly called trap, neuter, and return (TNR). Although proven successful, trap neuter return (TNR) is illegal in all states in Australia, except for the ACT [

34,

35,

36]. In the Banyule program, where there were multiple cats on private property and there was an identified caregiver, cats were sterilized and returned, but were microchipped and registered to the caregiver who became the legal owner. Thus, semi-owned cats became fully owned, with permanent identification. In the Banyule program, most of the cats sterilized were owned, with fewer semi-owned cats sterilized, including a minority from multi-cats (>3.0 cats) sites on private property. The decrease in cat intake associated with sterilizing owned cats is consistent with recent modeling showing that sterilizing owned cats in the UK will have the greatest impact on decreasing the free-roaming cat population [

37].

Initial shelter intake in the Florida study was 14 cats/1000 residents [

32]. Although Banyule data was not available prior to 2017-2018 for owner-relinquished cats and strays admitted directly by the public to the shelter, based on known impoundments from the target area at baseline and intake of impoundments, strays from general public and owner-surrendered cats over the last four years of the program, total shelter intake from the three target suburbs was likely around 13 cats/1000 residents at baseline in 2012-13 and approximately 9 cats/1000 residents in 2013-2014.

Our results demonstrate that marked decreases in shelter cat intake can be achieved over three years and eight years of providing a free sterilization, microchipping and registration program for owned cats or semi-owned cats fed by residents. By microtargeting the program to cats most at risk of impoundment or surrender, the decrease in intake was comparable to that achieved in Florida, but at achieved at much lower levels of desexing (5 cats/1000 residents/year for three years versus 60 cats/1000 residents/year for two years) and hence lower cost. The reduction in cat intake freed up resources of the contracted shelter (CPS) and enabled them to assist other animal welfare shelters by taking their excess cats and kittens for rehoming.

4.2. Outcomes - Reclaimed by Owner Rates, Rehomed and Euthanized

4.2.1. Reclaimed

Over the eight years of the program, the proportion of cats reclaimed by owners more than doubled from 6%, which was below the reported average (10-13%) for Victoria in 2018 [

1], to 20% in 2019-2020 and 16% in 2021-22.

Microchipping is mandatory for registration (licensing) in Victoria and all 831 cats sterilized in the Banyule program were implanted with a microchip for permanent identification. It was considered best practice that all stray cats collected by AMOs were scanned in the field (when safe or possible to do so) for a microchip to facilitate cats being returned directly to their owner. In cases where the owner could be quickly contacted, it avoided impoundment of a wandering owned cat. Increasing the proportion of cats returned to owners decreases the proportion that require to be rehomed. Hence, returning cats to owners decreases shelter intake, costs and improves cat welfare, including reducing risk of shelter-acquired infectious disease [

38].

In TNR and return-to-field programs, cats are not traditionally implanted with a microchip, and these cats are sterilized and returned to where found. Because TNR and return to field is illegal in Australia, where multiple cats were sterilized for a semi-owner (cat caregiver), their name was lodged on the microchip and registration databases. Along with sterilization, TNR programs in the USA focus on vaccination for rabies, rather than identification by microchipping. In contrast to USA, Australia is rabies-free and identification by microchipping is mandatory in all states and territories except Northern Territory.

4.2.2. Rehomed

The total number of cats rehomed decreased by 66%, although the percentage of impounded cats that were rehomed did not change significantly from baseline (66% versus baseline of 59%). This was because the number of cats impounded was greatly reduced. Decreasing the number of cats requiring rehoming represents a significant reduction in costs for the shelter, which are reported as AUD

$1,540 (

$385 per week) [

39] for a 30-day length of stay, including the veterinary care required before rehoming. It also frees up shelter resources which could be invested in sterilization programs, pet retention programs, or extending services to other areas.

For shelters with contracts with local government animal management services, cats brought in by AMOs, that are typically trapped in response to nuisance complaints, were reported to place a greater burden on the shelter because of lower adoption rates and longer length of stay, than cats surrendered directly to these facilities by finders, owners or semi-owners [

40]. In Illinois, stray cats impounded by AMOs at a shelter took on average 20 days longer to rehome than a stray cat brought in by a finder (total of 33 days versus 13 days, including the seven-day holding period). Owner-surrendered cats spent the least amount of time in the shelter before rehoming, associated with their greater sociability [

40].

4.2.3. Euthanasia

The number of impounded cats that were euthanized decreased by 82% over the eight years of the program. This reflected both a decrease in the total number of cats impounded, and a decrease in proportion euthanized from 35% (138/396) to 19% (25/134). The number of cats euthanized citywide was reduced from 1.1 cats/1000 residents in 2012-13, to 0.2 cats/1000 residents in 2020-21. Subjectively, AMOs observed that the sociability of impounded cats and kittens improved over the eight years of the program. There was a noticeable reduction in the proportion of trapped cats and kittens that were living under houses or born in sheds, and an increase in the proportion raised in home environments and handled.

This decrease in euthanasia is consistent with results from the study of six US cities where a median reduction of 83% in the numbers of cats euthanized occurred after sterilizing an average of 5.4 cats/1000 residents per year for three years [

27]. However, in contrast to the Banyule program which sterilized mostly owned cats in low socioeconomic suburbs, the US programs employed TNR [

41] and return to field (shelter-neuter-return) [

42].

Return to field (RTF) programs involve unidentified cats that are trapped by AMOs or brought in as strays from the public and are healthy, but may not be readily adopted because they are fearful of people [

40]. These cats are sterilized, vaccinated, ear tipped and returned to their outdoor home location. This is based on the premise that someone is feeding them, and that in the shelter these cats have lower adoption rates and higher euthanasia than cats from other sources [

40]. Following implementation of a RTF program, cat and kitten impounds were reported to decrease by 29% and dead cat pick up off the streets declined by 20% [

38,

40]. Return to field is increasingly being embraced in the USA, and in 2023, 6.6 % of cats were returned to field, representing 12.6% of stray cat intake [

43].

By reducing intake of poorly socialized cats, TNR also reduces the number of cats euthanized for behavior reasons [

32]. TNR was introduced in the USA because the traditional methods of cat management based on trapping, impounding, rehoming, or euthanizing was not effective in stopping complaints or impoundments and was increasingly unacceptable to the community and shelter staff because of the high numbers of healthy cats and kittens being killed [

44]. In contrast to Australia, where TNR is illegal in all states and territories except ACT, TNR is legal in most states of USA [

36].

In 2018-19 in Australia, the average euthanasia rate for shelters and municipalities operating their own facility (excluding rescue groups) was 33% and a quarter of municipalities operating their own facilities in Victoria euthanized 73-98% of cats [

2]. The impact of high euthanasia rates significantly contributes to poor mental health of AMOs, greatly reducing job satisfaction and psychological wellbeing. The potential for psychological injury is not limited to AMOs, but effects all animal carers and advocates who are exposed to euthanizing healthy and treatable cats, including the veterinarians and shelter workers who provide care, form attachments and are bonded to the cats [

1,

3,

6,

45,

46].

AMOs in the city of Banyule observed an increase in job satisfaction associated with offering the free sterilization, microchipping, and registration program to those in the community who had cats they owned or cats they were caring for (per comm JC). This resulted in a feeling of being empowered to provide proactive solutions to the community for cat-related issues, rather than engaging in reactive measures which resulted in feeling helpless and unable to effectively assist residents, or their cats. The program appeared to increase rapport with the community and contributed to improved job satisfaction for the AMOs.

The benefits to council in making their cat management programs more proactive and assistive, and less enforcement-centered and reactive, is that they lower the risk of psychological injury to their AMOs, community veterinarians and shelter/pound staff. This may not only increase staff retention and provide greater job satisfaction, but also positively impact council expenditure relating to absenteeism, workers compensation, and recruitment [

1,

47]. A US study on the impacts of euthanasia on employee turnover in animal shelters, found that staff who made decisions on the euthanasia of animals that were not based on behavioral or health reasons, had higher staff turnover compared to staff making decisions on euthanasia for health and behavioral issues [

6].

Animal and human welfare are connected, and by improving animal welfare, human welfare is improved, and vice versa [

48,

49]. Engaging in an assistive-centered approach to cat management aligns with the One Welfare framework and is characterized by a collaborative approach that focuses on amplifying the benefits of human-animal connectedness and their connection to environment. Thus, shelters and municipalities that embrace free sterilization programs for owned and semi-owned cats, microtargeted to locations of high cat impoundments or cat-related calls, can contribute to greater animal and human welfare. Aligning cat management to One Welfare is likely to provide more successful long-term outcomes for owned and semi-owned cats and for those who care for them [

45,

48].

It is recommended that legislation in Australia be amended to allow RTF and TNR to reduce the number of healthy and treatable cats killed in shelters and municipal facilities and negatively impacting staff. When applied with sufficient intensity, TNR will also reduce the environmental footprint of free-roaming cats, because it effectively decreases the number of cats over time [

34,

35]. Given that animal welfare, human well-being and environmental conservation are inextricably linked [

48] these recommended changes to legislation and cat management practices would contribute to addressing the adverse impacts on the psychological well-being of veterinarians, shelter staff and AMOs as well as benefiting the environment. In the city of Banyule, stray cats fed by caregivers (semi-owners) could not be sterilized if the caregiver was unwilling or unable to take ownership of the cats. To sterilize these cats, which are often in public places with multiple cats, it will require legislative changes to be legal.

Additionally, community stakeholders and the general public have an expectation that animal welfare legislation meet their community expectations, and in the past these expectations have been a major driver for legislation changes relating to animal welfare [

14,

50]. This is aligned with the concept of Social License to Operate (SLO) which refers to the implicit process by which a community gives approval to conduct activities [

51].

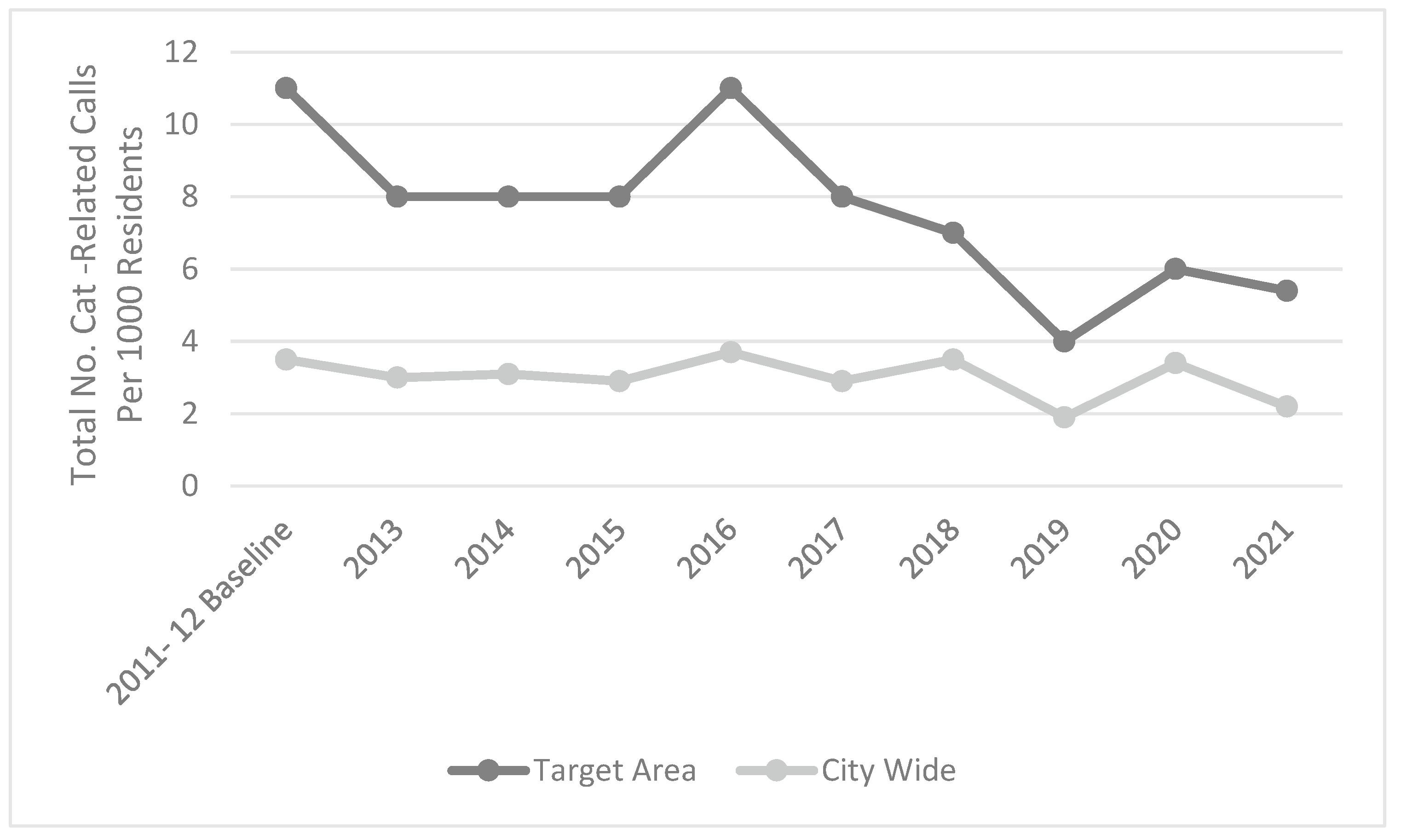

4.3. Complaints/Found Cat Calls to Council

Calls related to found cats and nuisance cats decreased city-wide by 36% over the eight years of the program, and by 51% in the target areas, which at baseline, had substantially higher calls to council relating to cats. However, there was a transient increase in complaints in 2020, potentially attributable to COVID-19 when residents were in lockdown and working from home [

52]. In the city of Banyule, cats are required to be kept on the owner’s property (known as leash laws in USA). Because residents were working from home during the pandemic, it is possible they were more aware of free-roaming cats and had more time to make complaints to council during 2020 [

53], with complaints decreasing again in 2021. This reduction in complaints is consistent with observed in USA associated with sterilization programs [

16,

54].

Current cat management strategies for AMOs in Australia and many other countries are focused on enforcement action, rather than having a One Welfare approach [

33]. This limits the ability to resolve issues relating to cat management in the long-term, because it does not consider the triad relationship between people, their animals, and the environment. For example, it is assumed easier to serve an enforcement notice on a resident directing them to keep a cat confined to a property, have it sterilized and registered (a reactive approach), rather than to provide an avenue for education, and proactively assist a resident to achieve suitable and appropriate cat management objectives. The enforcement focus is on non-compliance rather than garnering an understanding of community or individual needs. Cat intake into shelters and pounds are highest from low socioeconomic areas [

55] where residents are less able to comply with enforcement orders because of barriers of cost and accessibility. Proactively working with the community to overcome barriers to providing good animal health and welfare will ensure not only better outcomes for people and animals, but achieve greater levels of compliance [

56].

Implementing a targeted sterilization program proved a more effective strategy for the City of Banyule than introducing further restrictions or by-laws, for example, mandated sterilization of cats, particularly in low socioeconomic areas where compliance would be minimal for many cat owners or semi-owners because of the cost barrier [

56]. With a substantial proportion of free-roaming cats in urban areas being semi-owned, it is impossible for further mandates to be complied with in the community where there is no owner, or an owner cannot be identified. Like the City of Banyule, many councils in Victoria have mandated containment, but because most trapped cats have no identification, and hence no identifiable owner, mandatory confinement is in most cases not enforceable [

57,

58,

59] and results in many healthy cats being trapped and euthanized. Cat mandates implemented by councils, should be implemented with the view of how the mandate aligns to council objectives, how success will be measured if implemented, having effective consultation process with stakeholders, and most importantly consider alternatives to imposing a more restrictive local law on residents who may not be able to comply. These are part of the guidelines councils are encouraged to consider when preparing to make a local law, along with ensuring the least burden with the greatest advantage to community members [

60]. In USA, in many areas where cat confinement laws were introduced, they have since been retracted, because compliance is impossible to enforce or achieve when there is no identified owner [

61,

62].

In Victorian councils and many others across Australia, traditional trap, impound, reclaim, rehouse or euthanize methods are currently utilized. However, there are many stakeholders with differing opinions relating to cat management strategies. The traditional method of cat management is becoming increasingly unacceptable in the community because of the continuing euthanasia of healthy cats and kittens. Councils would be wise to evolve by shifting strategies to more proactive engagement with community and stakeholders, ensuring the interrelationship between animal welfare, human wellbeing and the physical and social environment are strengthened.

Employing the One Welfare framework to cat management strategies assumes an assistive-centered approach rather than an enforcement-centered approach. One Welfare concept recognizes that while animal welfare and human well-being are interlinked, there is a need for both to be considered in a social context, considering the mental health benefits of owning an animal and negative impacts on staff, including veterinarians, of euthanizing healthy animals [

49].

4.4. City-Wide Impoundments and Cat Nuisance Calls Costs Versus Costs of the Sterilization Program

While the savings related to reduced impound costs charged by CPS to council over eight years of the program were

$110,350, the greatest savings (

$155,875.00) were realized associated with reduced cat-related calls to council and the reduction in time spent by AMOs addressing complaints, estimated at

$290.00 per call. The total estimated savings over eight years was

$266,245.00. In comparison, the total cost to sterilize 831 cats was

$84,000. A study from Salt Lake City US, reported an average of

$400 per animal to implement an enforcement approach, which included officer response to attend, veterinary care, shelter housing and rehoming costs [

56]. It recommended that councils and animal welfare organizations invest in a more sustainable model of support, aimed at keeping animals in their homes [

56].

The cost to the city of Banyule per impounded cat of $80 to $150 was at the lower end of pricing from service providers in Victoria, with some councils paying up to $500 per impounded cat for housing for the mandated eight-day hold. However, many council service agreements only require payment for impounded cats brought in by AMOs, and not for owner-surrendered cats or stray cats coming directly to the shelter from the public. This was in contrast to the service agreement between CPS and the city of Banyule, which required all cats emanating from the local government area to be paid for.

In a study in the USA, a computer simulation model was utilized to estimate and compare costs for management options for free roaming cats to reduce the population size by 45% over 10 years [

63]. Costs were calculated assuming 75% of cats would be trapped and managed in one of five ways - trapped and euthanized; trapped, sterilized and all cats returned to location (TNR), TNR with 10% of trapped cats adopted (mainly kittens); trapped and after a mandatory hold of 7.5 days in shelter, all adopted, or half adopted, and half euthanized. The greatest cost was seen with trapping and adopting all cats (average cost

$US 342 per cat. Trap, hold in shelter for eight days and adopt or euthanize if not reclaimed is the method commonly used across councils in Victoria, Australia. This study also reported that TNR had the lowest costs (

$90 per cat), because of minimal costs for housing and associated care [

63]. Although TNR is illegal in most parts of Australia, the Banyule model was able to sterilize stray cats legally provided the carer became the legal owner. The program did not have any community members enrolling, where the carer was unable or unwilling to take ownership.

Given financial incentive for councils to implement management of free-roaming cats by sterilization, it is recommended that legislative changes be implemented to allow TNR in Australia, particularly where multiple cats are being cared for at a site. Provision in the legislation should be made for the cats to be microchipped as community cats, with contact details provided for a welfare agency, rescue group or the caregiver. This model is being successfully trialed under a research permit provided by the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries to the University of Queensland and operated by the Australian Pet Welfare Foundation in collaboration with RSPCA Qld and Animal Welfare League Qld. Cat intake and euthanasia in the trial suburbs has rapidly decreased over one to three years following implementation depending on numbers desexed per 1000 residents and degree of microtargeting [

64].