Submitted:

08 March 2024

Posted:

08 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains, Plasmids and Primers

2.2. Culture Media

2.3. Cultivation Condition

2.4. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

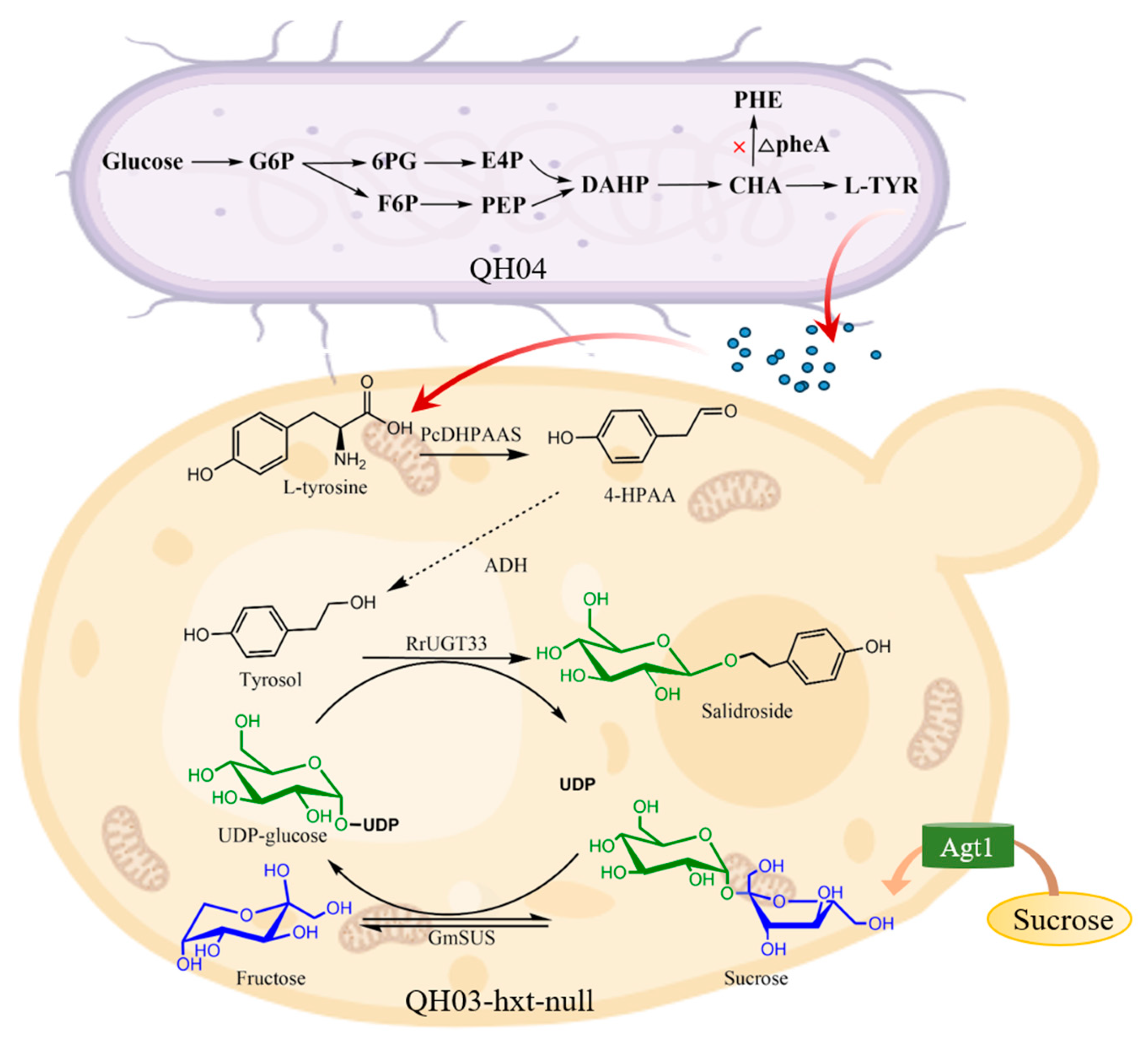

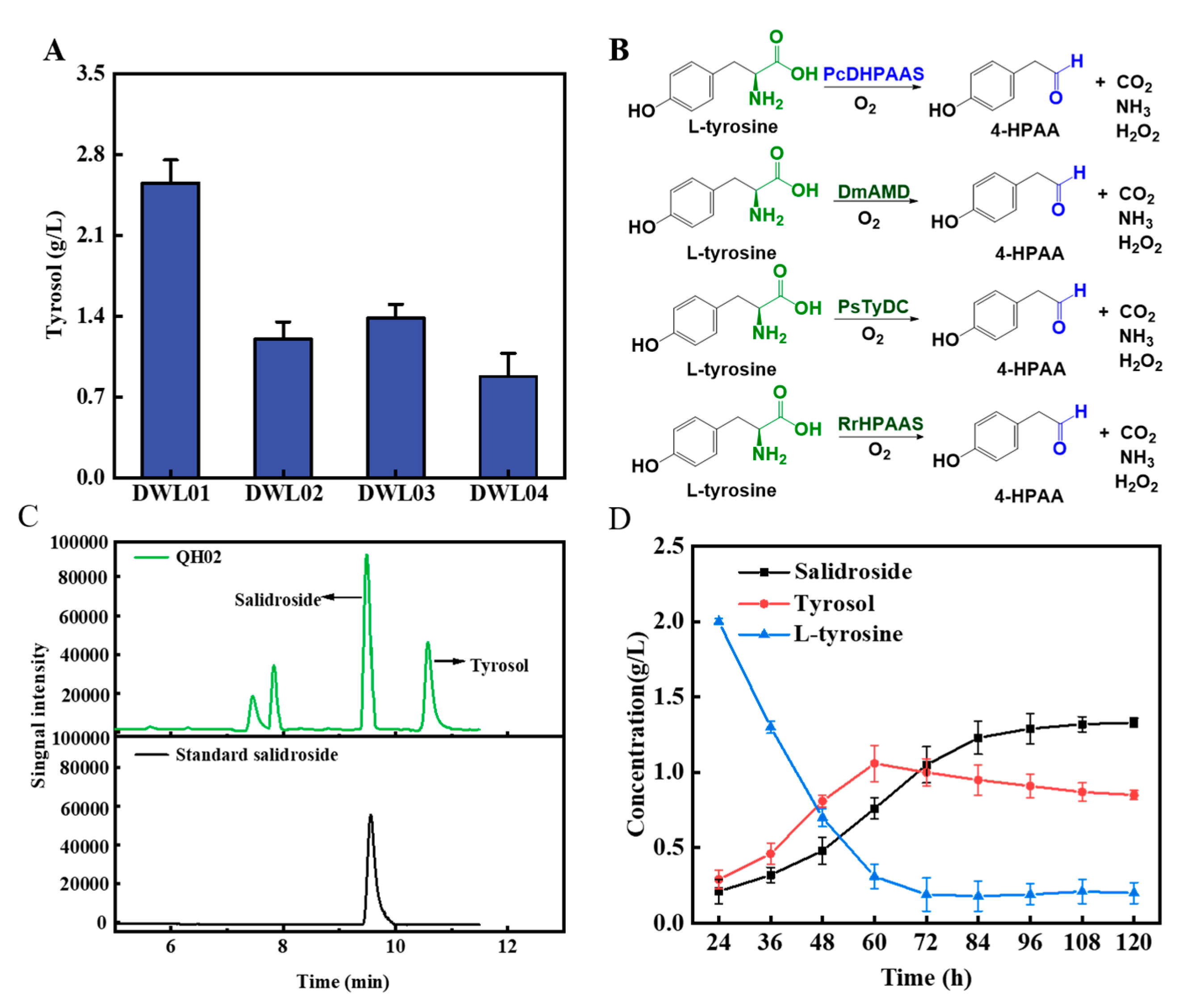

3.1. Construct a Biosynthetic Pathway from L-tyrosine to Salidroside in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

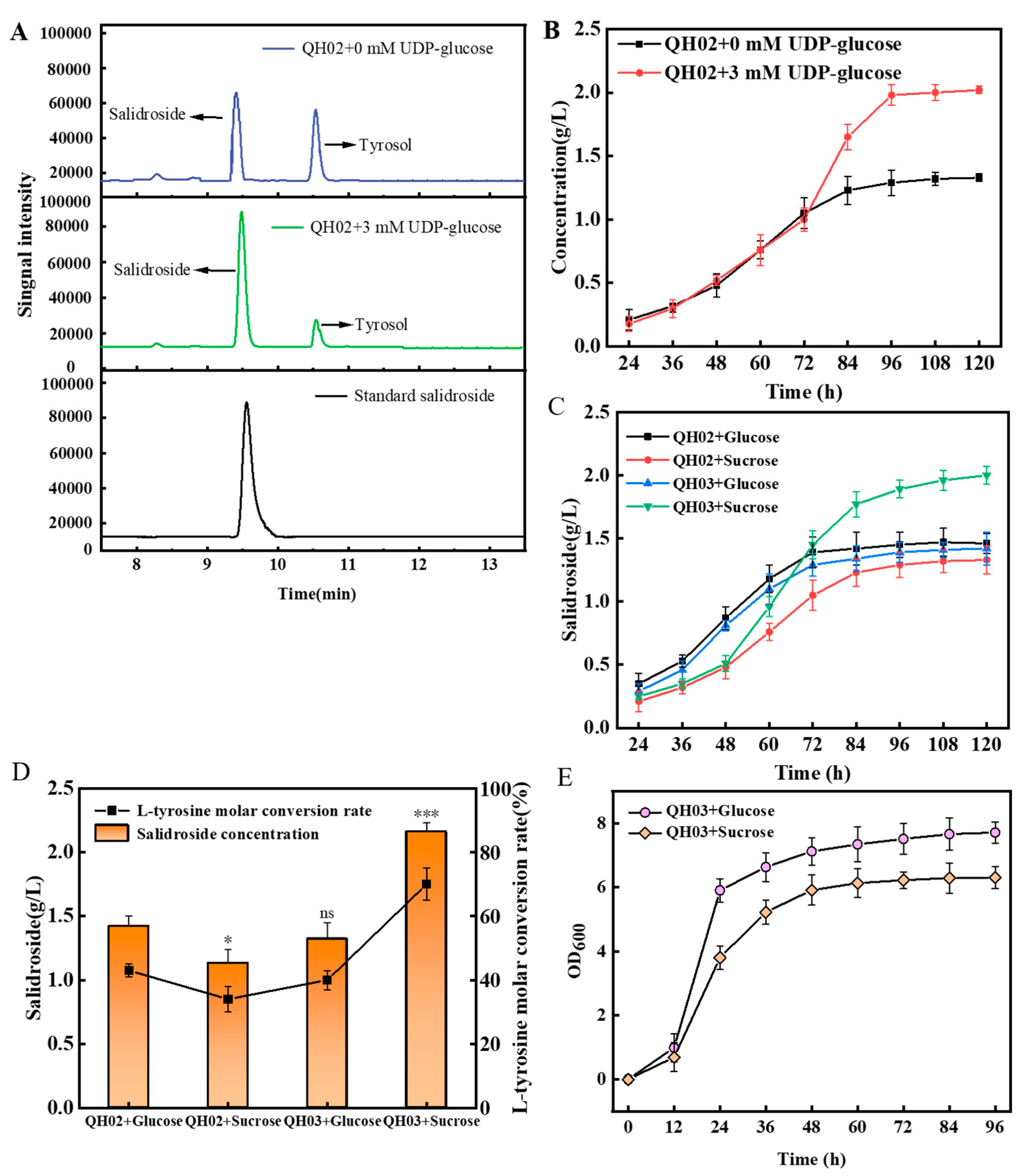

3.2. Efficient Synthesis of Salidroside by In-Situ UDP-Glucose Regeneration

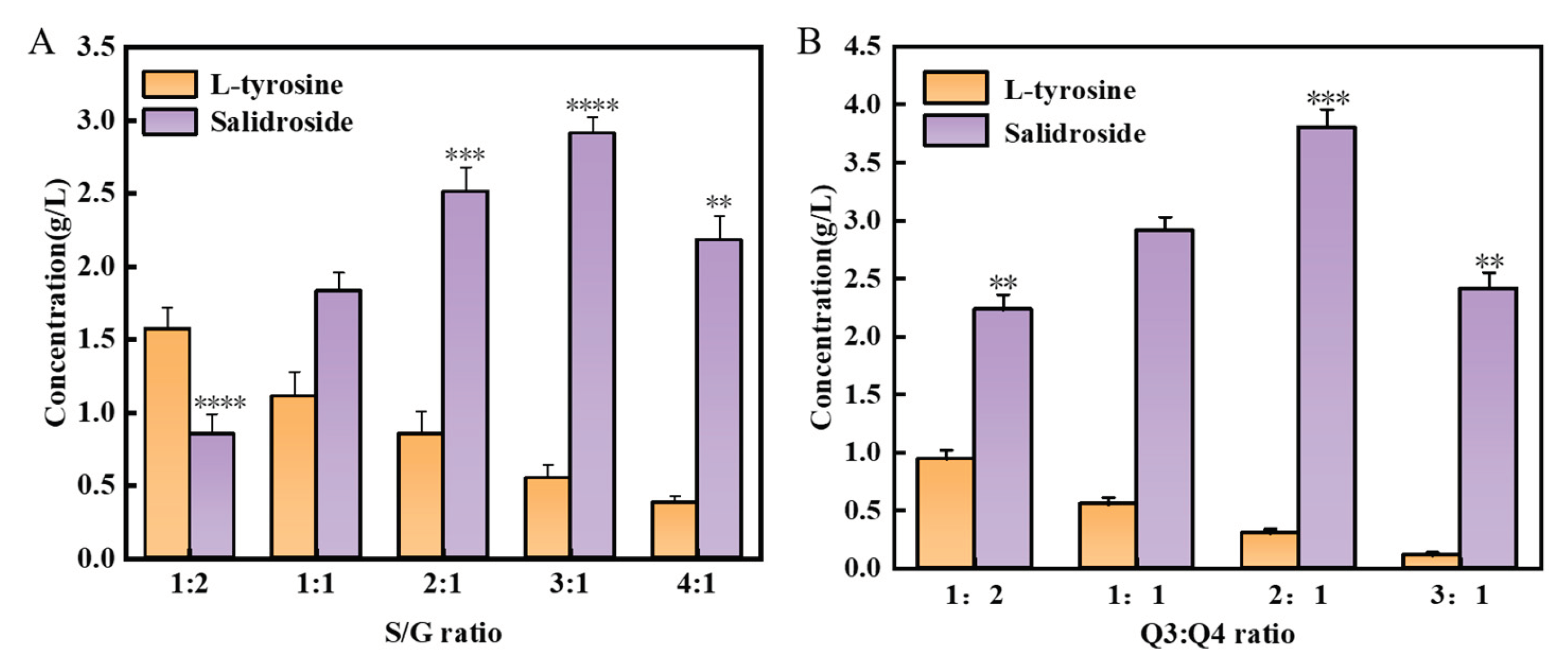

3.3. Optimize the UDP-Glucose Regeneration System for Effective Salidroside Production

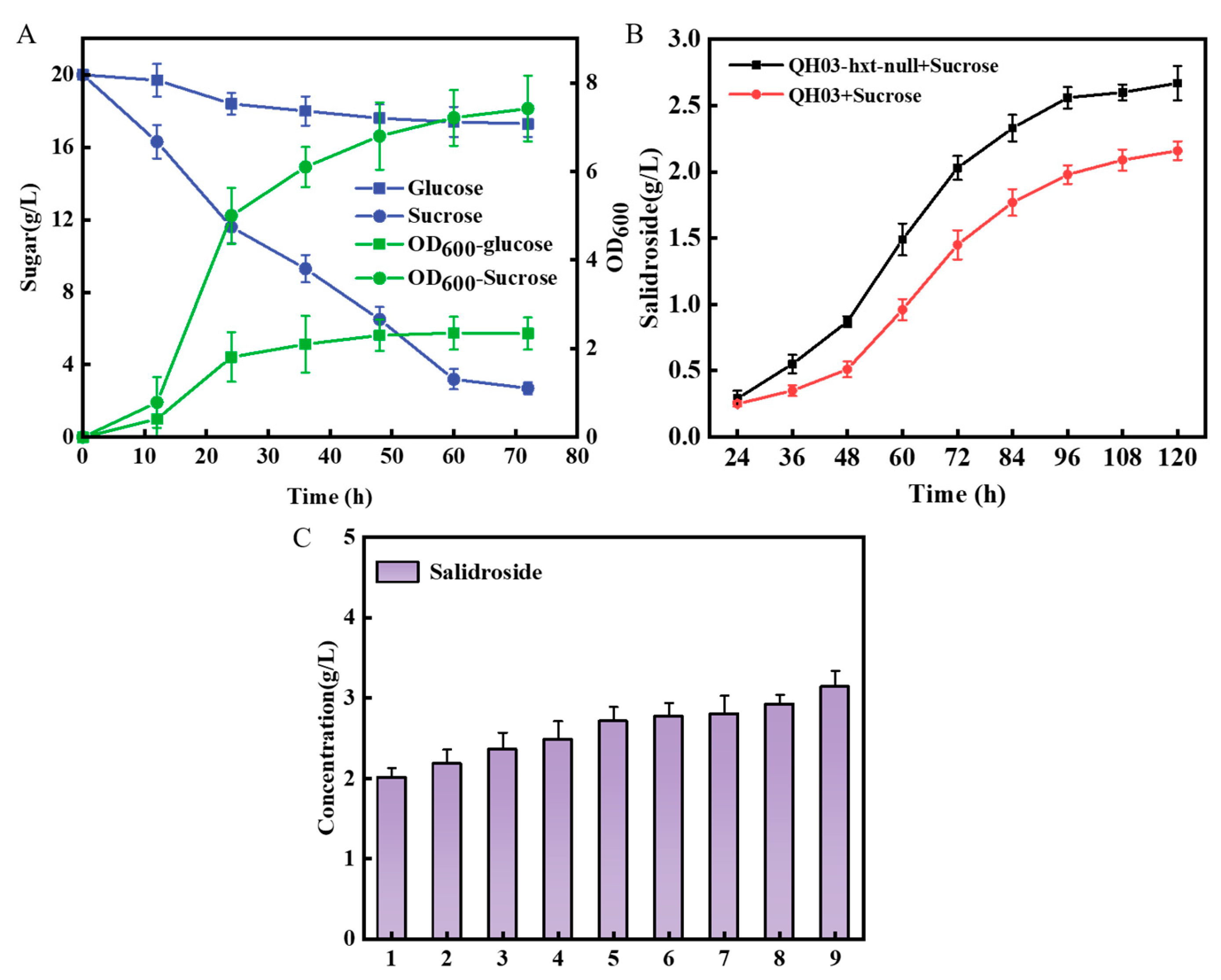

3.4. Construction of a Co-Culture System Used for De Novo Synthesis of Salidroside

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zha, J.; Wu, X.; Gong, G.; Koffas, M.A.G. Pathway enzyme engineering for flavonoid production in recombinant microbes. Metab Eng Commun 2019, 9, e00104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.M.; Chen, H.C.; Wu, C.S.; Wu, P.Y.; Wen, K.C. Rhodiola plants: Chemistry and biological activity. J Food Drug Anal 2015, 23, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, T.; Zhou, F.; Wang, M.; Song, H.; Xiao, X.; Lu, B. Neuroprotective Effects of Four Phenylethanoid Glycosides on H2O2-Induced Apoptosis on PC12 Cells via the Nrf2/ARE Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wen, S.; Yan, F.; Liu, K.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Ji, X. Salidroside provides neuroprotection by modulating microglial polarization after cerebral ischemia. J Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchev, A.S.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Gyorgy, Z.; Mirmazloum, I.; Aneva, I.Y.; Georgiev, M.I. Rhodiola rosea L.: from golden root to green cell factories. Phytochem Rev 2016, 15, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Huang, Q.L.; Feng, Y.H.; Tan, T.C.; Niu, S.H.; Hou, S.L.; Chen, Z.G.; Du, Z.Q.; Shen, Y.; Fang, X. Rewiring central carbon metabolism for tyrosol and salidroside production in " (Vol. 117, pg 2410, 2020). Biotechnol Bioeng 2022, 119, 2010–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.J.; Yin, H.; Wang, S.A.; Zhuang, Y.B.; Liu, S.W.; Liu, T.; Ma, Y.H. Metabolic Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for High-Level Production of Salidroside from Glucose. J Agr Food Chem 2018, 66, 4431–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallscheuer, N.; Menezes, R.; Foito, A.; da Silva, M.H.; Braga, A.; Dekker, W.; Sevillano, D.M.; Rosado-Ramos, R.; Jardim, C.; Oliveira, J.; et al. Identification and Microbial Production of the Raspberry Phenol Salidroside that Is Active against Huntington's Disease. Plant Physiol 2019, 179, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.X.; Chen, X.Z.; Yang, C.; Chang, J.Z.; Shen, W.; Fan, Y. Engineering for Enhanced Tyrosol Production. J Agr Food Chem 2017, 65, 4708–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.; Kim, S.Y.; Ahn, J.-H. Production of three phenylethanoids, tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, and salidroside, using plant genes expressing in Escherichia coli. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.B.; Jiang, J.L.; Liu, Z.N.; Qiao, B.; Li, F.F.; Cheng, J.S.; Sun, X.C.; Yuan, Y.J.; Qiao, J.J.; et al. Convergent engineering of syntrophic coculture for efficient production of glycosides. Metabolic Engineering 2018, 47, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Q.; Xue, Y.X.; Yang, C.; Shen, W.; Fan, Y.; Chen, X.Z. Modular Engineering of Tyrosol Production in. J Agr Food Chem 2019, 67, 3900–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.S.; Ma, L.Q.; Zhang, J.X.; Shi, G.L.; Hu, Y.H.; Wang, Y.N. Characterization of glycosyltransferases responsible for salidroside biosynthesis in. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrens-Spence, M.P.; Pluskal, T.; Li, F.S.; Carballo, V.; Weng, J.K. Complete Pathway Elucidation and Heterologous Reconstitution of Biosynthesis. Mol Plant 2018, 11, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Kan, Y.; Wu, T.; Xiao, W.; Luo, Y. Multi-modular engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-titre production of tyrosol and salidroside. Microbial Biotechnology 2021, 14, 2605–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuan, N.H.; Chaudhary, A.K.; Van Cuong, D.; Cuong, N.X. Engineering co-culture system for production of apigetrin in Escherichia coli. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 45, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xie, J.; Cao, S.; Zhang, H.; Pei, J.; Bu, S.; Zhao, L. Efficient production of the glycosylated derivatives of baicalein in engineered Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2023, 107, 2831–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Yang, G.Y.; Chen, X.H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.L.; Deng, Z.X.; Feng, Y. Biosynthesis of plant-derived ginsenoside Rh2 in yeast via repurposing a key promiscuous microbial enzyme. Metabolic Engineering 2017, 42, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Kan, Y.; Wu, T.; Xiao, W.; Luo, Y. Multi-modular engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-titre production of tyrosol and salidroside. Microb Biotechnol 2021, 14, 2605–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, L.; Shi, H.; Tang, F.; Cao, F. Efficient Biotransformation of Luteolin to Isoorientin through Adjusting Induction Strategy, Controlling Acetic Acid, and Increasing UDP-Glucose Supply in Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thummler, F.; Verma, D.P.S. Nodulin-100 of Soybean Is the Subunit of Sucrose Synthase Regulated by the Availability of Free Heme in Nodules. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1987, 262, 14730–14736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Fang, J.W.; Zhang, J.B.; Liu, Z.Y.; Shao, J.; Kowal, P.; Andreana, P.; Wang, P.G. Sugar nucleotide regeneration beads (superbeads): A versatile tool for the practical synthesis of oligosaccharides. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2001, 123, 2081–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masada, S.; Kawase, Y.; Nagatoshi, M.; Oguchi, Y.; Terasaka, K.; Mizukami, H. An efficient chemoenzymatic production of small molecule glucosides with in situ UDP-glucose recycling. Febs Lett 2007, 581, 2562–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roell, G.W.; Zha, J.; Carr, R.R.; Koffas, M.A.; Fong, S.S.; Tang, Y.J.J. Engineering microbial consortia by division of labor. Microb Cell Fact 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.H.; Wang, X.N.; Zhang, H.R. Balancing the non-linear rosmarinic acid biosynthetic pathway by modular co-culture engineering. Metabolic Engineering 2019, 54, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, T.G.; Yuan, S.F.; Wagner, J.M.; Yi, X.; Saha, A.; Smith, P.; Nelson, A.; Alper, H.S. Compartmentalized microbes and co-cultures in hydrogels for on-demand bioproduction and preservation. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X. Modular co-culture engineering, a new approach for metabolic engineering. Metab Eng 2016, 37, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawed, K. Advances in the development and application of microbial consortia for metabolic engineering (vol 9, e00095, 2019). Metabolic Engineering Communications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Akdemir, H.; Silva, A.; Zha, J.; Zagorevski, D.V.; Koffas, M.A.G. Production of pyranoanthocyanins using Escherichia coli co-cultures. Metabolic Engineering 2019, 55, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Qiao, K.J.; Edgar, S.; Stephanopoulos, G. Distributing a metabolic pathway among a microbial consortium enhances production of natural products. Nature Biotechnology 2015, 33, 377-U157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.A.; Vernacchio Victoria, R.; Collins Shannon, M.; Shirke Abhijit, N.; Xiu, Y.; Englaender Jacob, A.; Cress Brady, F.; McCutcheon Catherine, C.; Linhardt Robert, J.; Gross Richard, A.; et al. Complete Biosynthesis of Anthocyanins Using E. coli Polycultures. mBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Policarpio, L.; Koffas, M.A.G.; Zhang, H. De novo biosynthesis of complex natural product sakuranetin using modular co-culture engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 4849–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwibedi, V.; Saxena, S. Effect of precursor feeding, dietary supplementation, chemical elicitors and co-culturing on resveratrol production by Arcopilus aureus. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 2022, 52, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoruchko, A.; Nielsen, J. Production of natural products through metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2015, 35, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, S.E. Engineering of Secondary Metabolism. Annu Rev Genet 2015, 49, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Dong, X.T.; Li, F.F.; Wang, E.X.; Wang, E.X.; Li, B.Z.; Yuan, Y.J. Production of naringenin from D-xylose with co-culture of E-coli and S-cerevisiae. Engineering in Life Sciences 2017, 17, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.F.; Yi, X.; Johnston, T.G.; Alper, H.S. De novo resveratrol production through modular engineering of an Escherichia coli-Saccharomyces cerevisiae co-culture. Microb Cell Fact 2020, 19, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, D.; Hu, H.; Yang, R.; Lyu, X. De Novo Production of Hydroxytyrosol by Saccharomyces cerevisiae-Escherichia coli Coculture Engineering. ACS Synth Biol 2022, 11, 3067–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.C.; Hinkelmann, J.; Hermenau, A.; Schwab, W. Enhanced production of β-glucosides by in-situ UDP-glucose regeneration. Journal of Biotechnology 2016, 224, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifenberger, E.; Freidel, K.; Ciriacy, M. Identification of Novel Hxt Genes in Saccharomyces-Cerevisiae Reveals the Impact of Individual Hexose Transporters on Glycolytic Flux. Mol Microbiol 1995, 16, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunas, R. Sugar-Transport in Saccharomyces-Cerevisiae. Fems Microbiol Lett 1993, 104, (3–4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, J.H.; Barford, J.P. Direct Uptake of Sucrose by Saccharomyces-Cerevisiae in Batch and Continuous Culture. J Gen Appl Microbiol 1991, 37, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barford, J.P.; Phillips, P.J.; Orlowski, J.H. A New Model of Uptake of Multiple Sugars by Saccharomyces-Cerevisiae.1. Bioprocess Eng 1992, 7, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, J.; Ottolenghi, P. Localization of Invertase in a Strain of Yeast. Cr Trav Lab Carlsb 1958, 31, 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Barford, J.P.; Mwesigye, P.K.; Phillips, P.J.; Jayasuriya, D.; Blom, I. Further Evidence of Direct Uptake of Sucrose by Saccharomyces-Cerevisiae in Batch Culture. J Gen Appl Microbiol 1993, 39, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.I.S.; Wahl, A.; Gombert, A.K. Aerobic growth physiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on sucrose is strain-dependent. FEMS Yeast Research 2021, 21, foab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Koffas, M.A.G. Production of anthocyanins in metabolically engineered microorganisms: Current status and perspectives. Syn Syst Biotechno 2017, 2, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.S.; Miletti, L.C.; Stambuk, B.U. Sucrose Fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lacking Hexose Transport. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology 2005, 8, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.-F.; Yi, X.; Johnston, T.G.; Alper, H.S. De novo resveratrol production through modular engineering of an Escherichia coli–Saccharomyces cerevisiae co-culture. Microbial Cell Factories 2020, 19, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yuan, Q. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for microbial synthesis of monolignols. Metabolic Engineering 2017, 39, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, S.R.; Bernstein, H.C.; Song, H.S.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Fields, M.W.; Shou, W.Y.; Johnson, D.R.; Beliaev, A.S. Engineering microbial consortia for controllable outputs. Isme J 2016, 10, 2077–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Ding, M.Z.; Jia, X.Q.; Ma, Q.; Yuan, Y.J. Synthetic microbial consortia: from systematic analysis to construction and applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2014, 43, 6954–6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).