Submitted:

07 March 2024

Posted:

08 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sediments and Overlying Water Sources

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

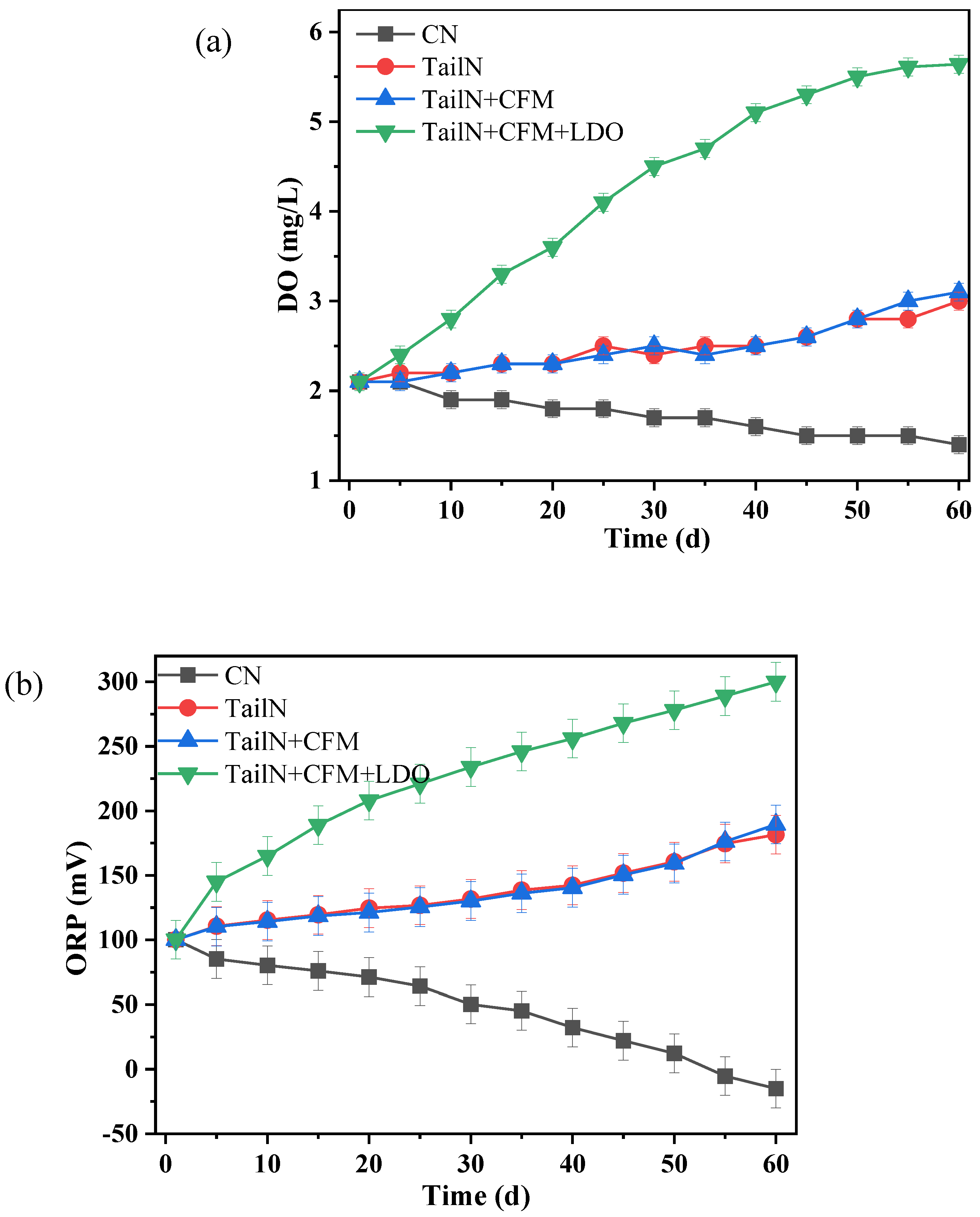

3.1. Physiochemical Parameters

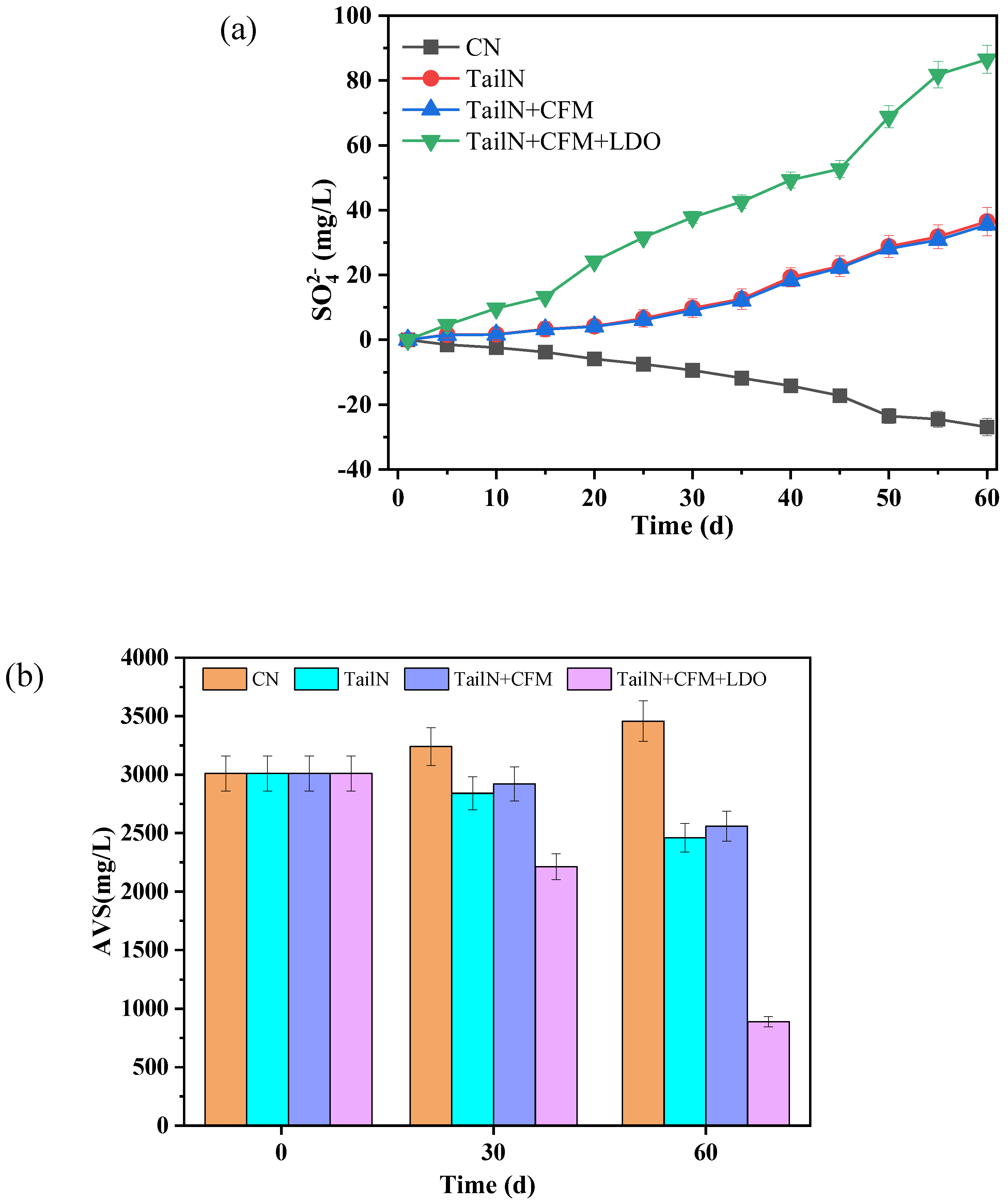

3.2. Changes in Sulfur Forms in Water

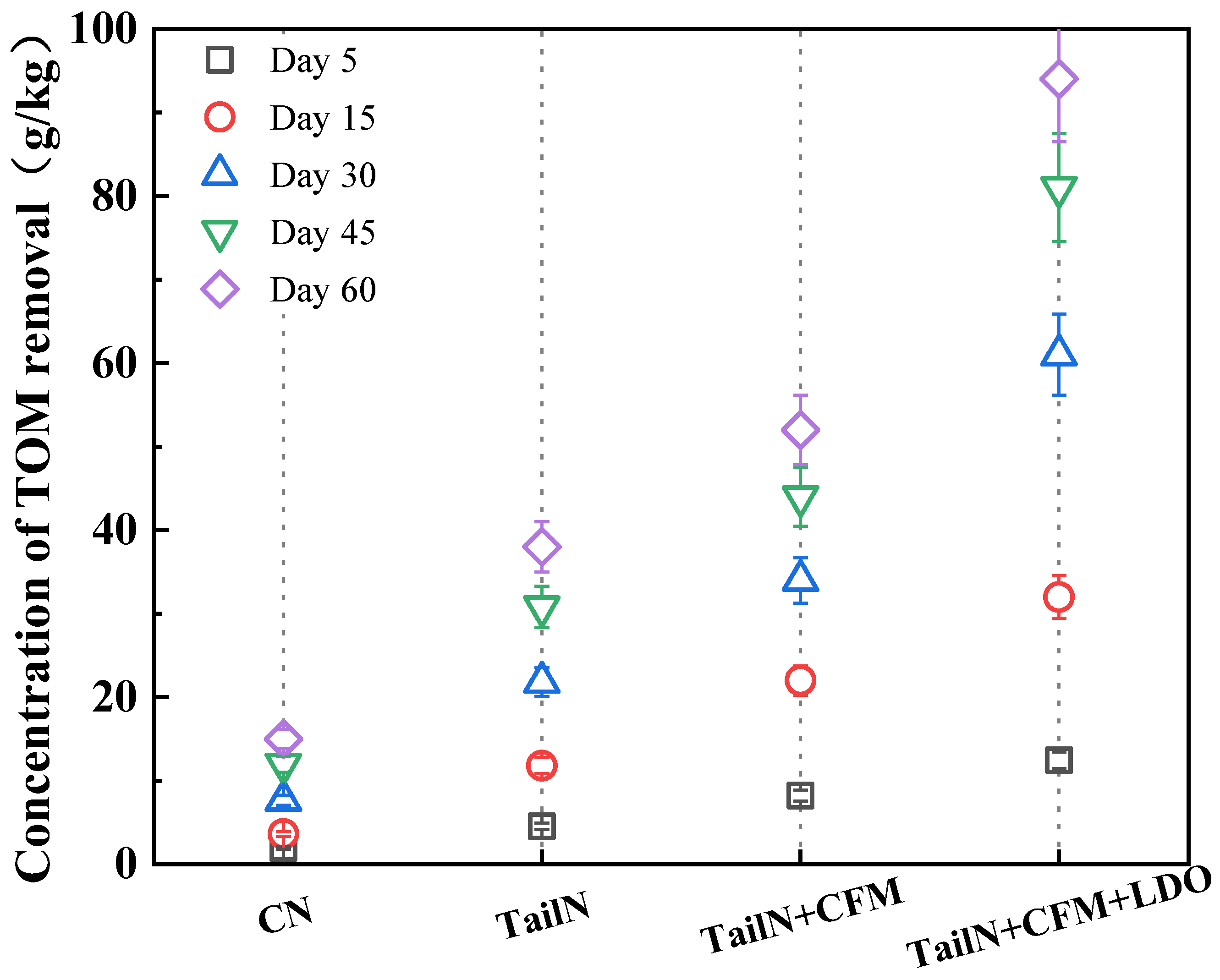

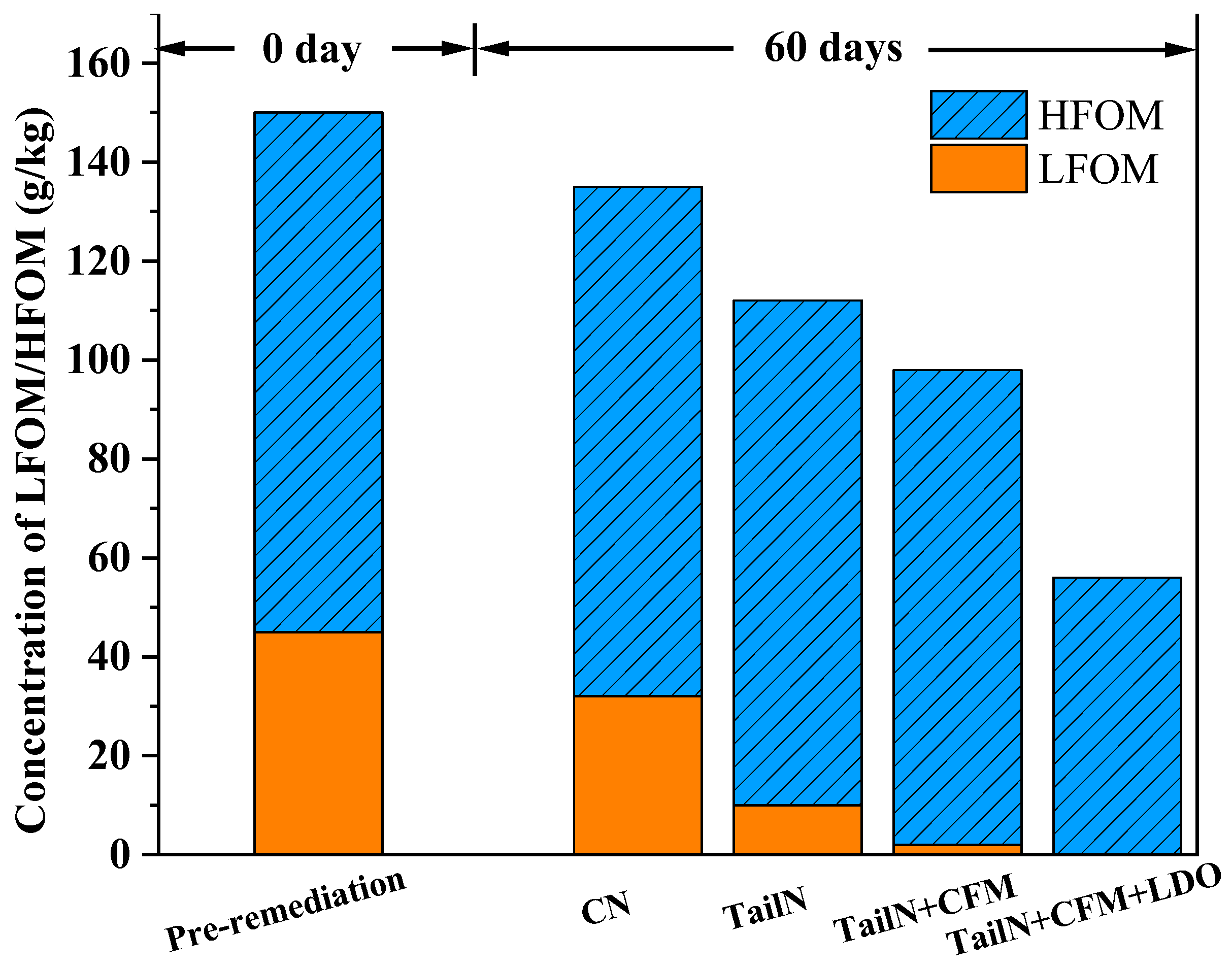

3.3. Changes in the Morphology of Organic Matter in the Sediment

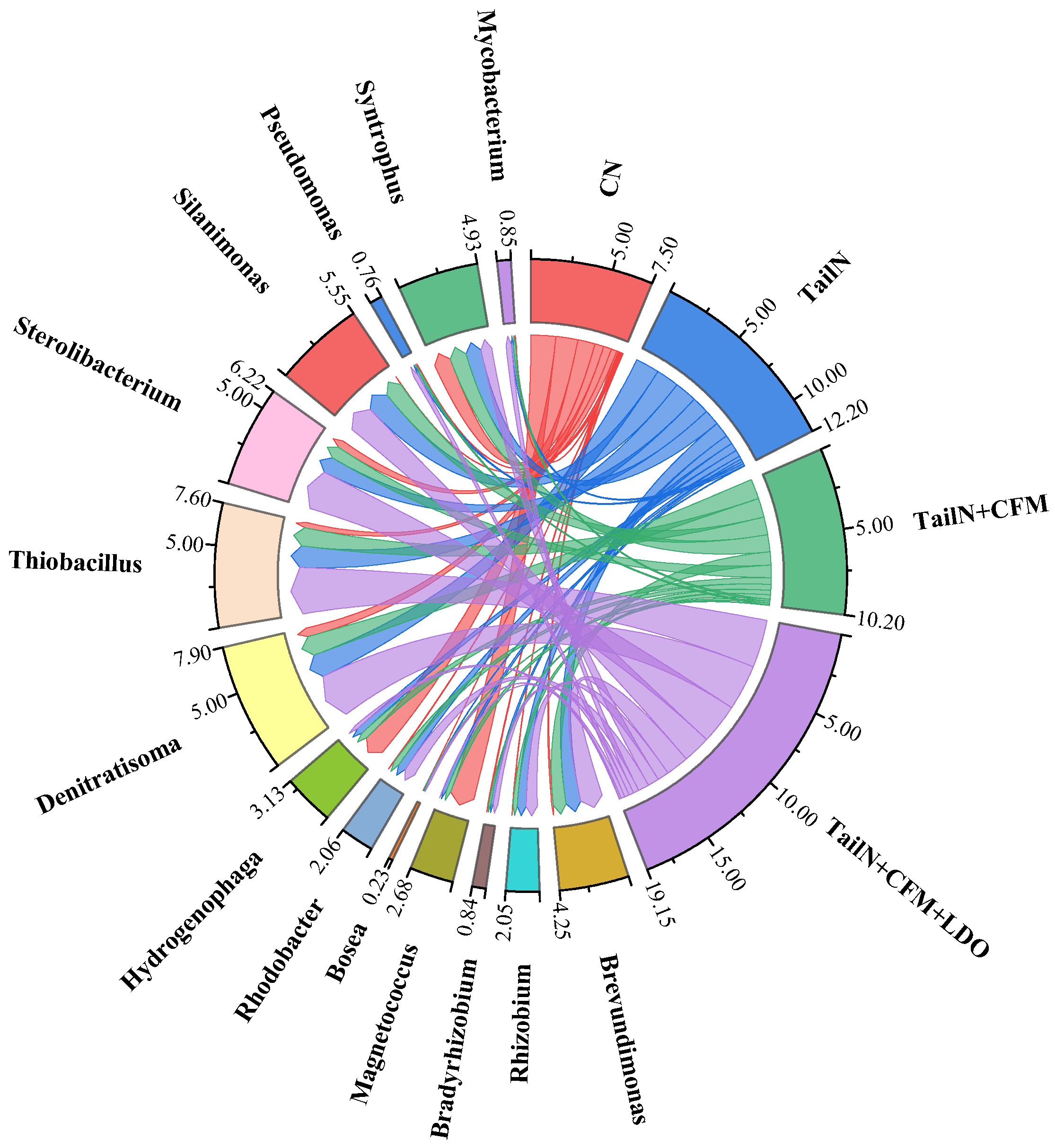

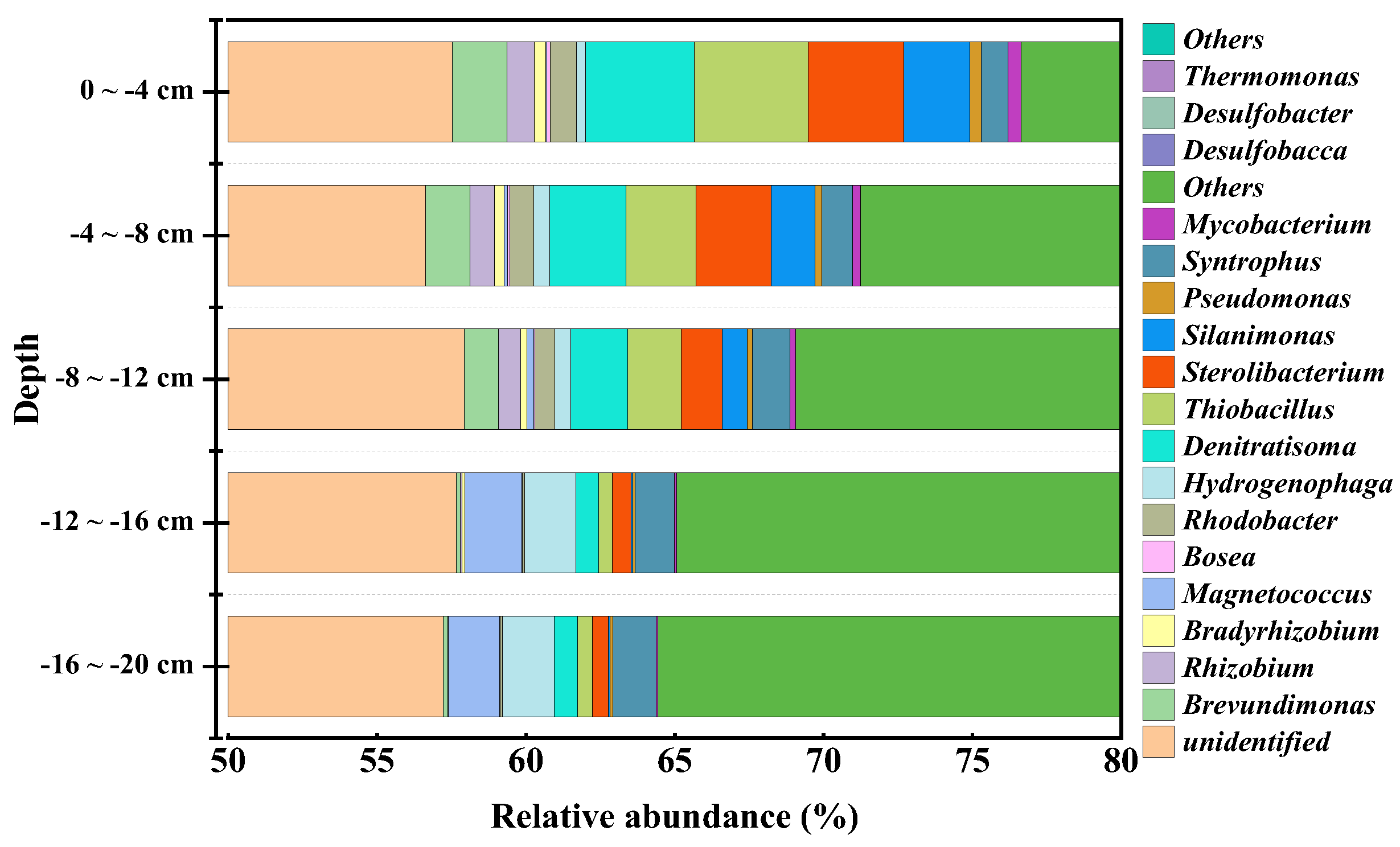

3.4. Analysis of Sediment Microbial Community Structure

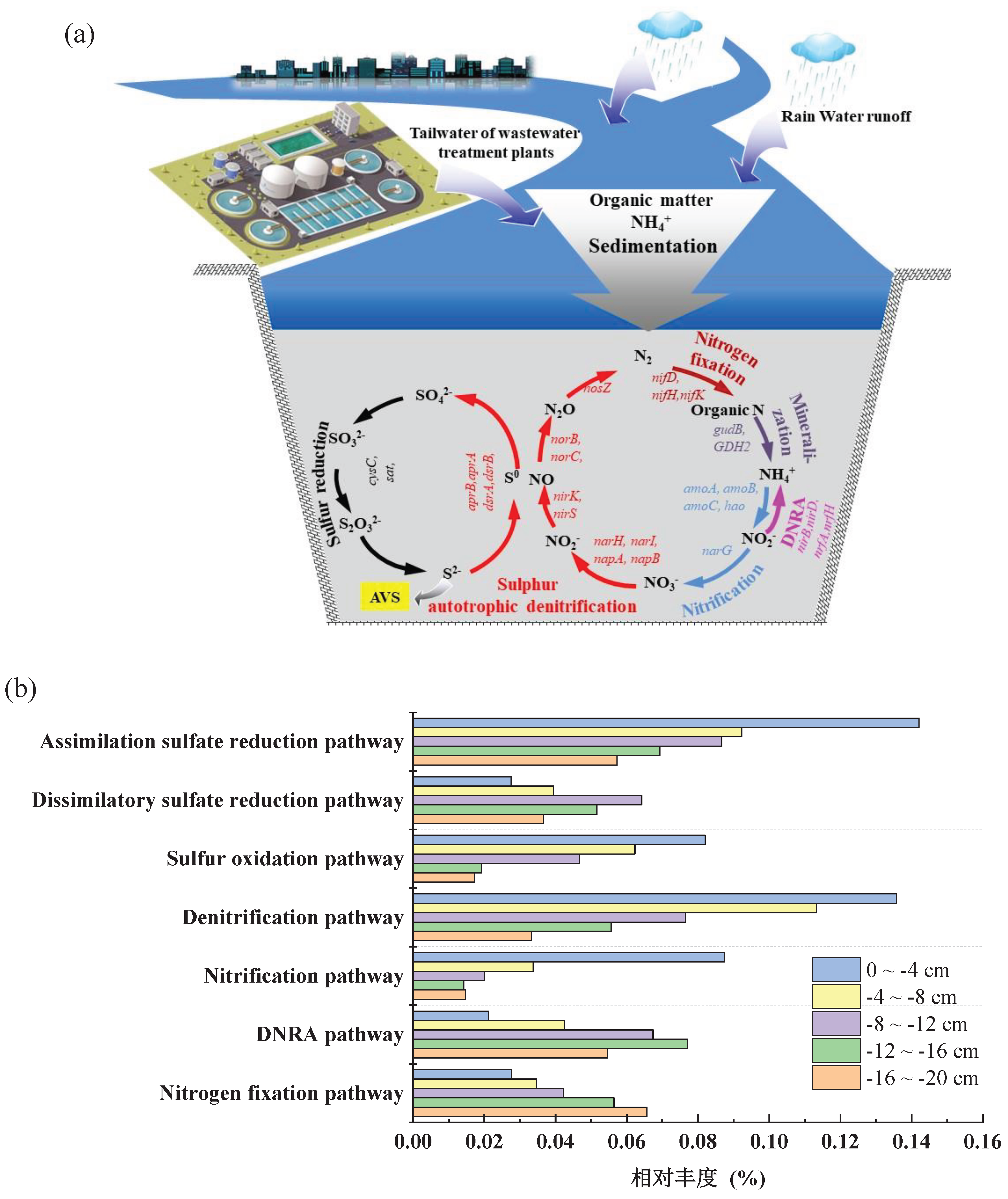

3.5. Mechanisms of Improvement in Sediment Microbial Ecological Environment

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- Gong, S.; Donde, O.O.; Cai, Q.; Wu, X.; Song, K.; Wang, C.; Hong, P.; Xiao, B.; Tian, C. Improved lakeshore sediment microenvironment and enhanced denitrification efficiency by natural solid carbon sources. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2022, 37, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, D.; Xu, M.; Shen, Q.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Ding, S. A critical review of the appearance of black-odorous waterbodies in China and treatment methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Yang, P.; Kong, M. Effects of nitrate dosing on the migration of reduced sulfur in black odorous river sediment and the influencing factors. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 371, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.-H.; Yan, F.-L.; Ding, Z.; Feng, L.-L.; Zhao, J.-C. Effects and mechanisms of calcium peroxide on purification of severely eutrophic water. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2796–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Li, W. In-situ remediation of sediment by calcium nitrate combined with composite microorganisms under low-DO regulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697, 134109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, J. The mechanism of C-N-S interconnection degradation in organic-rich sediments by Ca(NO3)(2)-Ca-O2 synergistic remediation. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhang, X. Effect of water quality improvement on the remediation of river sediment due to the addition of calcium nitrate. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y. Application of calcium peroxide in water and soil treatment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 337, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Roberts, K.L.; Grace, M.R.; Kessler, A.J.; Cook, P.L.M. Role of organic carbon, nitrate and ferrous iron on the partitioning between denitrification and DNRA in constructed stormwater urban wetlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Hou, L.; Gao, D.; Liu, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z. Organic matter degradation state affects dissimilatory nitrate reduction processes in Knysna estuarine sediment, South Africa. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 3202–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yang, F.; Gao, H.; Bai, Y.; Liao, H.; Li, H. Simulation of Denitrification Process of Calcium Nitrate Combined with Low Oxygen Aeration Based on Double Logarithm Mode. Water 2022, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Qi, Z.; Huang, J.; Sun, J. An improved method of fluorescein diacetate determination for assessing the effects of pollutants on microbial activity in urban river sediments. J. Soils Sediments 2022, 22, 2792–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, D.; He, Y.; Yue, H.; Wang, Q. Metagenomic and quantitative insights into microbial communities and functional genes of nitrogen and iron cycling in twelve wastewater treatment systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 290, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.B.; Martiny, A.C.; Martiny, J. Global biogeography of microbial nitrogen-cycling traits in soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8033–8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Sun, F.; Zhao, H.; Mi, H.; He, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lan, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z. Compositional changes of sedimentary microbes in the Yangtze River Estuary and their roles in the biochemical cycle. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Sun, J.; Huang, J.; Chang, S. Fluorescein diacetate hydrolytic activity as a sensitive tool to quantify nitrogen/sulfur gene content in urban river sediments in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 62544–62552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aßhauer, K.P.; Wemheuer, B.; Daniel, R.; Meinicke, P. Tax4Fun: predicting functional profiles from metagenomic 16S rRNA data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2882–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Huang, R.; Liang, Y.; Yu, G.; Chong, Y.; Wang, L. Index for nitrate dosage calculation on sediment odor control using nitrate-dependent ferrous and sulfide oxidation interactions. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 226, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Long, X.; Chong, Y.; Yu, G. Potential risk assessment of heavy metals in sediments during the denitrification process enhanced by calcium nitrate addition: Effect of AVS residual. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 87, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhu, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Duan, X.; Wu, J.; Tong, C. Anaerobic organic carbon mineralization in tidal wetlands along a low-level salinity gradient of a subtropical estuary: Rates, pathways, and controls. Geoderma 2019, 337, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Zhao, X.; Dang, Q.; Cui, D.; Xi, B. Microbially reducible extent of solid-phase humic substances is governed by their physico-chemical protection in soils: Evidence from electrochemical measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 134683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, J.; Liu, C.; Tang, Y.; Huang, J. The remediation of urban freshwater sediment by humic-reducing activated sludge. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 115038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Fan, C.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of in situ simulated dredging to reduce internal nitrogen flux across the sediment-water interface in Lake Taihu, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 214, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Liu, Y.; Fang, K.; Zhang, C. Microbial aerobic denitrification dominates nitrogen losses from reservoir ecosystem in the spring of Zhoucun reservoir. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manucharova, N.A.; Vlasenko, A.N.; Tourova, T.P.; Panteleeva, A.N.; Stepanov, A.L.; Zenova, G.M. Thermophilic chitinolytic microorganisms of brown semidesert soil. Microbiology 2008, 77, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.F.; Zhang, Y.M.; Liang, D.H.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, Z.; Li, M. Performance and microbial community of an immobilized biofilm reactor (IBR) for Mn(II)-based autotrophic and mixotrophic denitrification. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 286, 121407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, Y.; Oguchi, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Kusama, S.; Sugiura, R.; Moriya, K.; Hirata, T.; Yukioka, Y.; Takaya, N.; Yajima, S.; et al. Nitrogen oxide cycle regulates nitric oxide levels and bacterial cell signaling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshri, J.; Ram, A.S.P.; Sime-Ngando, T. Distinctive Patterns in the Taxonomical Resolution of Bacterioplankton in the Sediment and Pore Waters of Contrasted Freshwater Lakes. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 75, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Zhan, G.; Qian, J.; Tao, Y. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction by Pseudomonas alcaliphila with an electrode as the sole electron donor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 2904–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Su, W.; Jiang, Y.; Su, M.; Gao, P.; Li, D. Effects of cathode potentials and nitrate concentrations on dissimilatory nitrate reductions by Pseudomonas alcaliphila in bioelectrochemical systems. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Peng, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhang, L.; Ni, B.; Kartal, B.; Feng, X.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Yuan, Z. Metagenomic analysis of anammox communities in three different microbial aggregates. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 2979–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Niu, L.; Wang, L. The bacterial community structure and N-cycling gene abundance in response to dam construction in a riparian zone. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Ye, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Ye, F.; Chang, X.; Long, A. Shift of DNRA bacterial community composition in sediment cores of the Pearl River Estuary and the impact of environmental factors. Ecotoxicology 2021, 30, 1704–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Nitrate Migration and Transformation in Low Permeability Sediments: Laboratory Experiments and Modeling. Water 2023, 15, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Chen, P.; Wei, X. Correlations of functional genes involved in methane, nitrogen and sulfur cycling in river sediments. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhou, X.-F.; Yu, Y.-Q.; Liu, X.; Zeng, R.J.-X.; Zhou, S.-G.; He, Z. Light-driven nitrous oxide production via autotrophic denitrification by self-photosensitized Thiobacillus denitrificans. Environ. Int. 2019, 127, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Li, Z.; Hou, Y.; Wang, A.; Liu, Q.; Huang, C. Effects of different carbon sources on the efficiency of sulfur-oxidizing denitrifying microorganisms. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G.; Ekama, G.A.; Wang, Y.; Dai, J.; Biswal, B.K.; Chen, G.; Wu, D. Advances in sulfur conversion-associated enhanced biological phosphorus removal in sulfate-rich wastewater treatment: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 285, 121303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Pang, Y.; Ji, G. Increase of N2O production during nitrate reduction after long-term sulfide addition in lake sediment microcosms. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Ji, G. Long-term sulfide input enhances chemoautotrophic denitrification rather than DNRA in freshwater lake sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 270, 116201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Gao, L.; Hou, Y.-N.; Nan, J.; Ren, N.; Li, Z.-L. Influence of microbial spatial distribution and activity in an EGSB reactor under high- and low-loading denitrification desulfurization. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).