1. Introduction

1.1. General Observations about Green and Digital Transition

Urbanization has led to unprecedented challenges for urban environments, including the loss of green spaces, increased pollution, and rising temperatures. Our current urbanization model is unsustainable in many respects. And yet, urbanization continues with 68% of the global population expected to live in cities by 2050 [

1]. Urban life becomes increasingly challenging: heat waves, health and environmental risks are only expected to increase [

2]. At the same time, the share of GHG emissions from cities is making them a major contributor to global warming but also a potential solution provider for achieving the Paris climate agreement objectives [

1,

2]. During COP28 the Secretary General of the United Nations talked of humanity committing “collective suicide” and targeted fossil fuel companies who “have humanity by the throat”. Amid rapidly rising temperatures that were observed earlier this year, he mentioned: “The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived” and encouraged rich countries to provide more support, due to their failure in achieving low emissions and adequate reduction plans [

3]. In this context, urban greening is considered crucial in improving life in cities and climate mitigation and adaptation, since it can improve wellbeing, health, biodiversity, water quality, the microclimate and overall sustainability [

3,

4].

Even the recent COVID-19 sanitary crisis brought changes in the lifestyle and behavior of citizens, which was perceived by many cities as an opportunity to promote sustainable development patterns through open spaces, parks, and alternative models of urban transportation [

5].

More and more national, regional, and local rules require new buildings and developments to respect minimum targets on different green aspects (energy efficiency, water use) including planting (unbuilt and unsealed areas, green roofs) [

4,

6]. For the latter, there are assessment systems developed around the world, such as the Green Building Standards of the United States Environmental Protection Agency [

7] or European Union’s ‘’Level(s)’’ that provide a framework to assess sustainability of buildings [

8]. LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), a widely used US-originated commercial green building rating system, includes credits and categories that might reward or incentivize the incorporation of green spaces, encouraging developers to include outdoor areas, such as vegetated spaces, or sustainable landscaping in their projects. More specifically, the credit of open space requires the creation of outdoor space greater than or equal to 30% of the total site area (including building footprint). A minimum of 25% of that outdoor space must be vegetated to contribute to a project's overall LEED certification score [

9]. Similarly, the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) in the UK encourages the provision of outdoor spaces, biodiversity enhancements, and ecological considerations in the development [

10]. In BREEAM's Land Use and Ecology category, for example, projects can achieve credits by demonstrating features like outdoor amenity spaces, provision of habitat areas, and landscaping that supports biodiversity. On the other side of the planet, the Green Star rating system, developed in Australia, has categories such as 'Landscape' and 'Ecology,' which encourage the provision of outdoor areas, and measures that enhance the environmental performance of the site [

11]. Like other rating systems, projects can earn credits within these categories by including features like green roofs, outdoor amenity spaces, and vegetation promoting biodiversity.

Conversely, many urban structures are primarily characterized by their dense and monochromatic aesthetic. To meet green targets, existing cities and historic centers must intervene in existing facades and roofs, sealed pavements, and roads [

11,

12,

13]. Government-led initiatives, alongside citizen-led efforts, contribute to the greening of cities. In a state of climate emergency, citizens, enterprises, and other types of stakeholders are encouraged to act complementing and enriching institutionalized efforts. While bottom-up initiatives are increasingly crucial for improving quality of life in urban centers, they often consist of small-scale endeavors that are not measured, monitored, assessed, or scaled up. When it comes to monitoring those initiatives, it gets challenging to quantify the dedication and efforts of individuals or businesses in promoting urban greening.

In this context, the green transformation of urban cores can be reinforced through its ’twin’ digital transformation and the integration of smart technologies such as IoT, AI, and cloud computing into urban ecosystems and planning. Smart technologies, encompass remote sensing, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, data analytics, and citizen engagement platforms, which could work towards this goal, as powerful tools to monitor and enhance urban greening efforts. There is abundant evidence that smart environments, smart cities, the Internet of Things, in-short the main components of the smart everything-smart city paradigm, bring in a new way of addressing the environmental challenges of climate change, pollution, and cities in stress [

14,

15]. This twin transition that is reshaping urban ecosystems can lead to new city organization and planning models that diverge from the 20th-century paradigm. The new ‘smart city’ paradigm is defined as a technological construct driven by information technologies and embedded smart objects, but also complex cyber-physical systems of innovation in which physical and social spaces, knowledge processes and digital technologies are blended and produce innovative solutions to current challenges [

15]. Major technologies can allow for citizen engagement and collaboration networks to generate innovations for better cities and help citizens ’collaborative initiatives to scale up.

1.2. Research Statement and Goals

In this paper, we collect 100 citizen-led initiatives of urban greening around the world. We focus on initiatives where the contribution of citizens was the enabling factor. For the scope of this paper, we do not look at institutionalized interventions in urban space, for which official measurements and monitoring are most likely to exist. What we aim for is to shed more light into efforts stemming from citizen involvement, research endeavors, and non-governmental organizations. We are also looking into collaborative efforts fueled by private sector funding (e.g., corporate responsibility funds), such as the Business Development Districts.

The study aims to delve into methods that strengthen citizen ownership of green initiatives through smart technologies. The integration of smart technologies fosters community engagement and participatory actions. Mobile apps and online platforms can allow citizens to commit to act, decide on public budget spending, contribute data, report issues, and take part in partnerships. This interaction enhances public awareness and involvement in maintaining and expanding urban green spaces. Smart technologies, including remote sensing, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and big data analytics, can offer novel opportunities for real-time monitoring and management of urban green spaces. Furthermore, the collected data supports evidence-based policy decisions, aiding in the allocation of resources and targeted scaled up interventions for greening projects. This involves examining various strategies and approaches that can empower individuals and communities to take an active role in the planning, development, monitoring, and maintenance of environmentally sustainable urban greening projects. By shedding light to these often smaller-scale interventions and understanding the key factors that contribute to a sense of ownership and involvement, the research endeavors to offer valuable insights that can guide the implementation and monitoring of effective green initiatives within communities.

The paper sets out the study as follows:

Section 1 presents the topic of urban greening. The twin (green and smart) transition has been discovered to bolster community resilience during the unprecedented challenges caused by the current climate crisis. (

Section 1.1) The section also introduces the main research goals and questions (

Section 1.2). The answer to these questions will provide support to city authorities to monitor citizen-led urban greening initiatives.

Section 2 provides a literature review on the role of bottom-up urban greening initiatives in community empowering (

Section 2.1), an overview of current measurement tools and available mechanisms (e.g., indices) for measuring urban greening with a special focus on historical urban centers (

Section 2.2) as well as the types of urban greening (

Section 2.3). It also provides an overview on current technologies used by urban greening initiatives towards three directions, the digitally enabled participatory urban greening and community engagement (

Section 2.4.1), the monitoring and data analysis (

Section 2.4.2), and the scale up of these initiatives in order to maximize their benefits at the city (livability) and international (climate neutrality objectives) level (Section 2.4.3).

Section 3 introduces our methods and data collection approach and assesses 100 citizen-led initiatives.

Section 4 contains a categorization of the initiatives collected (section 4.1), based on the typology of infrastructure, the mode of implementation, and the incorporation of smart technologies.

Section 5 includes the conclusions with a summary of the range of factors that affect the incorporation of smart technologies in urban greening, while providing conclusions and recommendations for further study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Empowering Communities through Bottom-Up Urban Greening Initiatives

The relevance and importance of urban green is high in the context of the climate crisis. Rising temperatures and urban heat waves deteriorate the quality of life, the health, and the livability of cities, while urban green spaces become urban oases offering shade, lower temperatures and ecosystem services [

2,

16,

17]. Rapid urbanization and densification have resulted in the depletion of urban green spaces and biodiversity [

18]. Embracing nature-based solutions within urban greening initiatives presents an opportunity to enhance resilience and tackle multifaceted urban challenges simultaneously [

17]. Integrating these solutions into urban planning holds promise for fostering sustainable development and improving the overall quality of urban life.

Several cities have experimented with ways to remake themselves in response to climate change. These efforts, often driven by grassroots activism, aim at creating fair and livable communities from the ground up, including reclaiming their streets from cars, restoring watersheds, growing forests, and adapting shorelines to improve people’s lives while addressing our changing climate [

19]. For example, advocacy groups in Washington, DC are expanding the urban tree canopy and offering job training in the growing sector of urban forestry. In San Francisco, community activists are creating shoreline parks while addressing historic environmental injustice. We found several such advocates, non-profit organizations, community-based groups, and government officials which build alliances to support and embolden the urban greening vision together [

19].

By transforming concrete landscapes into vibrant green spaces, these initiatives create communal hubs that encourage social interaction, recreational activities, and shared experiences. Pocket parks, community gardens, and green corridors enhance the aesthetic appeal of urban areas and serve as focal points for gatherings, events, and community-driven activities and even urban farming. Multiple past analyses have shown that urban agriculture fosters community bonds, nurtures trust among residents, promotes civic participation, enhances well-being, and potentially mitigates socio-economic disparities [

20,

21,

22,

23]. The involvement of residents in the planning, maintenance, and use of these green spaces instills a sense of pride and responsibility, nurturing a shared commitment to the well-being and sustainability of their neighborhood, promoting their social cohesion, sense of belonging, social capital and critical health behaviors that might enhance psychological health and well-being [

24,

25,

26]. Books like "Life Between Buildings" and "Cities for People," from Jan Gehl have become foundational texts in the field of urban design, providing insights into creating cities that enhance the emotional and psychological well-being of their residents [

27,

28]. Jacobs also advocated for a more grassroots, community-driven approach to urban planning. She believed that residents have valuable insights into the needs and dynamics of their neighborhoods, and their input should be considered in planning decisions. As people converge in these green havens, bonds between neighbors foster a sense of unity and collective ownership [

29]. Today, happy cities are characterized by a sense of community and social trust, which can be achieved through a mix of public and green spaces for communal activities [

30].

Urban green spaces including pocket parks were particularly appreciated by residents during the different COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions. Being the principal place for interaction and exercise, urban green spaces were key for both the physical and mental health of people during that period [

5,

31,

32]. Pocket parks can enhance public health and foster social cohesion among residents, particularly in densely populated neighborhoods that are often underserved. The importance of pocket parks in offering accessible green spaces to urban populations was recognized even before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic; however, their role has now become even more critical, serving as essential lifelines for improving the health and well-being of urban residents during these challenging times [

18].

2.2. Urban Greening Policies and Measurement Toolkits

The concept of urban nature is gaining traction as a potential solution for promoting sustainability in urban planning and development [

33,

34]. Overall, at different levels (international, regional, local) urban greening policies and strategies are supported through different means. At the international level, UN is issuing toolkits and guidance documents, sets international fora for peer learning, offers international visibility (positive reputation of the city) through its platforms and communication channels for the best performing cities and initiatives and often offers capacity-building support with tailored advisory to local authorities.

On a regional scale, at the European level, we observe policies such as those supported by the European Union, which offer similar means and tools, with the important addition of funds given to authorities and partnerships that foster bottom-up and multistakeholder urban greening initiatives. Evidence-based policy and monitoring are informed by the European Environmental Agency (EEA), which is studying and issuing recommendations on urban greening. EEA measures urban greening with two indicators, urban tree cover and urban green space. Other indicators on air pollution and urban heat correlate to assessments on urban green. They also raise awareness that the potential of green spaces to boost health and well-being is increasingly recognized, both in science and policy [

35,

36]. The European Union has set a Biodiversity strategy with 2030 as the horizon [

33]. It is recognized that green spaces often lose out in the competition for land as the share of the population living in urban areas continues to rise. A guidance and toolkit are put in the availability of municipalities, proposing collaborative processes of developing urban greening plans. It is highlighted that municipalities need to work with citizens and other stakeholders and aim for cross-departmental work and integration of the greening plan with other aspects of urban development, from mobility and health, air and water, to energy and climate adaptation. Overall, this is indicative of many policy frameworks and measures deployed at the EU level as part of the European Green Deal that relies on citizen participation and activation. The ‘’New European Bauhaus’’ initiative, in the same line, awarded a citizen-led initiative in Spain, where citizens claimed unused space for the creation of a community park [

37].

On the other hand, Data4Cities is an evidence-based foundational initiative by the GCoM that measures and manages climate ambition and progress of cities and local governments. By using data, the GCoM aims at understanding the causes of climate change at an urban level, informing local climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, and advocating for the engagement of governments, private sector partners, and citizens. Through Data4Cities, GCoM aims at creating consistency in the collection of data, transparency, reporting and analysis of information. GCoM cities commit to the use of Environmental Insights Explorer (“Google Environmental Insights Explorer - Make Informed Decisions,” n.d.) launched in collaboration with Google for data access and the Data Portal for Cities (designed by GCoM and the World Resources Institute), for community-specific activity data and emission factors for the development of greenhouse gas emissions inventories and fact-based climate action planning. To allow comparisons and benchmarking, the GCoM created a common reporting framework for cities. Reports from participating cities are compiled in the Annual Impact Aggregation Report [

38].

At the local level, authorities are the ones to ultimately set their political priorities and decide to stream funds and resources towards green interventions. Authorities can decide on the degree of citizen involvement in policy and strategy making (e.g., through voting and participatory budget, workshops) as well as the interventions themselves, their monitoring and scaling up. When it comes to citizen-led initiatives, local authorities can decide on their level of tolerance or support for them. In the examples analyzed in the scope of this paper we find several cases of citizen-led occupation of unused and gray spaces and their transformation to green public spaces. There, the role of the local authorities is to tolerate, ‘’legalize’, or support such initiatives in the longer term through funds and resources.

In this context, cities can play a key role in meeting the targets outlined in the Paris Agreement on climate change. The engagement of cities and urban stakeholders is also supported by the New Urban Agenda and the 2030 SDGs [

39]. Integrating open spaces within urban environments can significantly enhance public health and overall well-being. In greener living environments, depression, diabetes, ADHD, migraines, high blood pressure and premature births are less common [

40]. This is achieved by mitigating socioeconomic disparities, alleviating social isolation, and promoting physical activity. Apart from the minimum number of green spaces per capita, a key aim pursued by many municipal leaders is to ensure that open spaces are conveniently accessible within a ten-minute walking radius. This initiative not only fosters a greater inclination for outdoor recreation and exercise, but also addresses a prevailing challenge in certain regions of the United States. Remarkably, over 100 million individuals in the United States, including 28 million children (about the population of Texas), currently lack access to a park within a ten-minute walk from their residences. More specifically, in Phoenix, merely 22% of the population enjoys such proximity to a park, 99% of Washington, DC residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park, however looking at the median city of the 100 most populous U.S. cities, this scores 74%, while for the median city considering all urban cities and towns in the U.S., the percentage drops to 55% [

41]. We see that San Francisco has achieved the commendable milestone of providing a 10-minute walk access to parks for all its residents in 2017, while other cities of California are still working towards this goal [

42].

Implementing a network of small-scale open spaces, pocket parks, and plazas dispersed throughout neighborhoods can significantly encourage pedestrian activity, ease social engagement, and contribute to an improved state of well-being. These spaces may serve as tranquil retreats for relaxation or dynamic venues for activities such as exercise, jogging, work, and more. ‘Smart Urban Growth’, ‘Transit-Oriented Development’ and ‘New Urbanism’ form a conceptual and planning model for environmentally sustainable communities and cities, promoting both the understanding of cities as living ecosystems as well as principles for the preservation of natural resources and ecosystems [

14,

33,

37]. Local authorities can also influence the international urban development agenda through their participation in networks. UN Habitat and the UN Environmental Program have set up the Green Cities Partnership that following the AVOID – SHIFT – IMPROVE model, which works focusing on four basic areas: the Information Sharing, Analysis and Advice, Tools Development and Practice and Actions [

43]. Networks and city associations, such as C40, ICLEI (Local Governments for Sustainability) or the Global Covenant of Mayors (GCoM), also support urban greening initiatives by issuing guidance and easing peer learning [

34,

38,

44,

45].

2.3. Types of Green Infrastructure

To better understand urban green interventions, it was important to define the type of interventions we are assessing for this study. Urban green infrastructure is characterized by distinctive features than its rural counterparts. One Typology is officially recognized by the European Commission and will be our basis in categorizing the initiatives in terms of the type of greening [

46,

47].

While the following list of elements is not exhaustive, it aims to provide an overview of some of the most common elements within a specifically urban and peri-urban setting as well as illustrative examples. This typology, as used by the European Commission includes ’Blue areas’ and ’Green areas for water management’ as two distinct categories. However, in the context of this research we have decided to merge them. Blue and water management cases are already very few, compared to other categories, especially with our scope being citizen-led initiatives in urban centers. In most cases, water management generally requires calculated infrastructure works and institutionalized interventions. Analyzing citizen-led initiatives based on the type of greening can help show the priorities and needs of citizens. Civic initiatives require the investment of time and effort and aim at addressing needs citizens consider important.

Table 1.

Types of green infrastructure.

Table 1.

Types of green infrastructure.

| Building greens |

Green balconies, ground based green wall, facade-bound green wall, extensive green roof, intensive green roof, atrium, green pavements and green parking pavements, green fences, and noise barriers. |

| Urban green areas connected to gray infrastructure |

Tree alley and street tree/hedge, street green and green verge, house garden, railroad bank, green playground/school ground, green parking lots, riverbank greens. |

| Parks and (semi)natural urban green areas, including urban forests |

Large urban park, historical park/garden, pocket park/parklet, botanical garden/arboreta, zoological garden, neighborhood green space, institutional green space, cemetery and church yard, green sport facility, forest, shrubland, abandoned and derelict area with patches of wilderness. |

| Allotments and community gardens |

Allotment, community garden, horticulture. |

| Agricultural land |

Arable land, grassland, tree meadow/orchard, biofuel production/ agroforestry, horticulture. |

|

Blue areas /Green areas for water management

|

Rain gardens or sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS), rain gardens, swales / filter strips.Lake/pond, river/stream, dry riverbed, canal, estuary, delta, seacoast, wetland/bog/fen/marsh. |

2.4. Smart Technologies, Big Data Analytics and Urban Greening

Upon evaluating the bibliography on the technological aspects of urban greening initiatives, discernible trajectory appears, outlining their advancement along three distinct pathways. The subsequent classification (2.4.1 - 2.4.3) provides a thorough examination of these directions.

2.4.1. Participatory Urban Greening Initiatives, Community Engagement and Partnership Establishment

Smart technologies empower citizens to actively engage in urban greening initiatives. For example, residents could compete in tree-planting contests or take part in scavenger hunts to identify plant species in local parks. Mobile applications and online platforms enable citizens to contribute data, report issues, and take part in tree planting activities, participatory budget spending. Citizen-contributed data enhances public awareness, fosters a sense of ownership, and creates a feedback loop between the community and urban planners. Mobile applications play a pivotal role by actively involving citizens in data collection efforts. These apps empower users to upload images, pinpoint locations, and provide vital feedback on the state of green spaces. This approach not only fosters a stronger sense of community engagement but also significantly amplifies the volume of data collected. Furthermore, specialized apps designed for citizen science projects enable residents to take an active role in monitoring green spaces, allowing them to report on various aspects such as plant health, wildlife sightings, and even participate in tree inventories. Online mapping and crowdsourcing platforms like Google Maps provide citizens with interactive tools to mark areas in need of greening, propose locations for community gardens, and pinpoint potential sites for tree planting. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have been helpful in mobilizing and organizing community events, disseminating progress updates, and building a sense of unity around urban greening endeavors. Additionally, digital surveys and feedback forms serve as invaluable tools to gather input from residents on their preferences for green space design, desired amenities, and suggestions for improvement. Through these technologies, cities are not only transforming urban landscapes but also fostering a stronger sense of community ownership and participation in greening efforts.

However, there are still opportunities to incorporate advanced technologies like Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) to envision urban greening initiatives. By incorporating VR and AR applications, citizens can immerse themselves in interactive experiences that allow them to visualize and engage with proposed greening projects. Implementing gamification and challenges related to urban greening further encourages participation. This hands-on approach provides a clearer understanding of the potential impact and instills a sense of ownership in the community. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and mapping tools play a vital role in planning workshops, where they can be used to visualize data and ease discussions about urban greening plans. This enables citizens to actively take part in the decision-making process and contribute valuable insights.

2.4.2. Monitoring Urban Greening Initiatives for Citizen Ownership

Smart technologies apart from the participation during the urban greening initiatives, they can also enable citizens to take an active role in monitoring them. Every neighborhood has the potential to oversee their initiatives using IoT devices and promptly address the ongoing requirements of the green space. Through the strategic application of these technologies, cities can also empower citizens and community organizers to monitor urban green areas in their neighborhoods, fostering a profound sense of ownership and pride in their local environment. In contrast to the environmental logic of New Urbanism and LEED-ND, which tries to improve the physical environment of cities, IoT-based environmental sustainability focuses on user behavior. We may describe the entire process by a sequence that starts from: (a) the deployment of sensors and smart meters across city ecosystems, districts, neighborhoods and utilities, which collect information from city activities, people, and supply chains; (b) information processing, analytics, knowledge extraction and dissemination to users and authorities; (c) users becoming aware and motivated to develop sustainable behavior through realizing they have a direct gain, a long-term environmental benefit, or some kind of reward; (d) public authorities obtaining information to design more sustainable policies; and (e) impact which is monitored, measured, documented, and disseminated [

14]. The Cityscape Lab Berlin is a proper example of this type of initiatives, which was originated within the framework of the Berlin-Brandenburg Institute of Advanced Biodiversity Research (BBIB), a collective of both university and non-university research institutions dedicated to biodiversity studies in Berlin and Potsdam [

48]. Its real-world implementation began in 2016, supported by funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under the collaborative initiative “Bridging in Biodiversity Science—BIBS,” spearheaded by Berlin’s Technical University (Technische Universität Berlin). The major aim of the Cityscape Lab Berlin is to provide a flexible research platform for exploring the effects of urbanization and rapid transitions in urban land-use patterns on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning at different spatial and temporal scales.

The integration of smart sensors and IoT devices for environmental monitoring could empower citizens to play a direct role in tracking parameters like air quality, soil moisture, and temperature. This not only promotes a sense of responsibility for green spaces but also creates a deeper connection between residents and their local environment. Remote sensing technologies, such as satellite imagery that is open source accessed and aerial drones owned by citizens, can offer a macroscopic view of urban green spaces. Satellite imagery provided by open-source applications such as google map enables accurate assessment of green cover, vegetation health, and spatial distribution over large areas. For example, the recent fires in Greece (August 2023), which have been burning for several days, were aerially captured by the European Space Agency's (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission, a constellation of two satellites that each have a high-resolution multispectral imager to observe changes in our land and vegetation [

49]. Satellites are particularly helpful during natural disasters, while aerial drones can also provide high-resolution imagery, allowing for detailed analysis of individual green spaces.

Additionally, a combination of traditional field-based methods and advanced technologies is employed to measure urban greening. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) create spatial databases, enabling mapping, spatial analysis, and calculation of metrics like green space density and connectivity. Urban green space indices like the Vegetation Area Index (VAI) and Green View Index (a measurement of urban green at the street level) that quantify factors like land cover and accessibility. Also, spatial metrics and urban indicators offer quantitative insights into green space quality and accessibility. Utilizing these technologies to measure and monitor urban greening enables policymakers, urban planners, and researchers to assume greater responsibility in green initiatives within urban areas. This empowers them to make informed decisions regarding the management and improvement of green spaces in urban environments.

4.4.3. Smart Technologies for Scaling up Urban Greening Initiatives

The integration of geographic information systems (GIS) also eases the mapping, analysis, and interpretation of remote sensing data, enabling citizens with specific occupations such as Urban Planners, Statisticians, Data Scientists, Urban Technologists, Site and Urban designers etc. to make informed decisions. These technologies collectively generate large volumes of data, which can be analyzed using advanced algorithms to derive valuable insights into the dynamics of urban greening. These technologies offer a bird's-eye view of the city, enabling the measurement of vegetation cover, density, and health.

Collected data is often analyzed using advanced analytics and machine learning techniques. These methods can extract patterns, correlations, and trends that inform urban greening assessments and management strategies, and anomalies in the data, helping in the prediction of vegetation growth, disease outbreaks, and other dynamic processes. These predictive capabilities aid in proactive urban greening management. The large volumes of data generated by smart technologies require advanced analytics for meaningful insights. By using these smart technologies, citizens and stakeholders can significantly enhance their ability to implement community initiatives and manage small-scale urban greening initiatives, leading to scaled up initiatives that can enhance a more sustainable, resilient, and livable future for cities, regions, countries, and the globe.

In recent advancements in urban greening research have been propelled by remarkable technological progress. The transformative impact of machine learning and big data have been proven effective in addressing research gaps within this field. These innovative technologies have offered unprecedented insights into ecosystem dynamics and their associated services, easing a deeper comprehension of intricate ecological processes [

50].

Machine learning algorithms have become indispensable tools for analyzing extensive datasets. By discerning patterns and relationships, these algorithms offer a more refined understanding of urban greening [

51,

52]. Data suggest that knowledge and practice are biased towards the Global North, under-representing key CBS challenges in the Global South, particularly in terms of climate hazards and urban ecosystems involved [

51]

. The integration of big data and technology in research and practice of urban greening transcends mere data analysis [

50]. These innovative tools have become invaluable resources for decision-makers and urban planners alike. The proposal of a geospatial model for nature-based recreation in Paris underscores the empowerment of a data-driven approach to conservation and urban development [

52]. By providing a systematic and informed framework, these technologies ease the seamless integration of sustainable practices into urban development strategies.

3. Scope Methods and Data Collection

To compile a diverse selection of 100 urban greening initiatives from across the globe serving as a representative sample, our methodology relied on two key approaches. Firstly, we drew upon cases that were familiar to the authors and sourced examples from pertinent literature, ensuring a foundation rooted in established knowledge and recognized practices. Secondly, we conducted a specialized workshop moderated by the authors during the Placemaking Europe Week 2023 [

53], specifically designed to gather additional cases. This interactive workshop served as an invaluable platform for collaborative engagement, allowing us to solicit and incorporate a range of innovative initiatives that might not have been previously documented or widely known. Through this dual strategy of leveraging existing knowledge sources and actively engaging with stakeholders, we were able to curate a comprehensive and diverse collection of 100 initiatives that collectively highlight a global perspective on the subject matter. After gathering those examples of urban green initiatives, only the examples where the citizens were the initiators, or the implementers of such initiatives were finally kept. However, we saw that in some cases, these were often fostered, framed, or supported by public institutions or private-public partnerships.

Figure 1.

Geographical spread of analyzed initiatives.

Figure 1.

Geographical spread of analyzed initiatives.

4. Research Findings and Discussion

4.1. Analysis Based on Enabling Actors

Urban greening initiatives can involve a diverse array of actors and stakeholders, each contributing unique expertise and perspectives to enhance the vitality of urban landscapes. Municipal authorities play a pivotal role, providing the regulatory framework, funding, and strategic planning necessary to initiate and sustain green initiatives. NGOs and community-based organizations actively engage with residents, advocating for green spaces, providing expertise, organizing volunteer efforts, and fostering community participation. Private sector entities, including developers and businesses, often collaborate to integrate green elements into urban infrastructure, promoting sustainability while enhancing commercial spaces. Academia and research institutions contribute scientific knowledge and innovation, by conducting pilots, informing evidence-based practices on the ecological and societal benefits of urban greenery [

54]. Collectively, citizens and other stakeholders mentioned can create collaborative networks, which can drive urban greening initiatives towards holistic, sustainable outcomes that benefit both the environment and communities. These synergies can vary based on cultural, societal, and legal frameworks.

Table 2.

Types of partnerships and actors leading and implementing the 100 initiatives.

Table 2.

Types of partnerships and actors leading and implementing the 100 initiatives.

| Implementing partners and partnerships of the 100 citizen-led initiatives analyzed |

|---|

| Citizens (solely at own capacities) |

28 |

| Local authority and Citizens |

28 |

| NGOs and Citizens |

20 |

| Multistakeholder partnership (public or public-private including citizens, authorities, NGOs and others) |

13 |

| School/University and their communities (professors, students, parents) |

9 |

| Businesses and Citizens |

2 |

4.1.1. Citizen-led Initiatives: Nonprofits, Community Groups

48 of the studied initiatives are entirely led by citizens (including partnerships between NGOs and citizens). Out of these initiatives, 61,7% are dedicated to urban farms and food growing, also showing the pressuring needs for food securing and self-determination in cities. We observe in some cases that after the creation of the green space takes place, the community organizes, setting non-profit organizations and/or setting up a decision-making mechanism that can be as simple as community meetings (e.g., Navarino park in Athens [

55]. Such cases show the role of urban gardening in creating bonds within the community and social cohesion. In relevant research, 8 case studies of community-led urban farms were analyzed showing that neighborhood-bound gardens and gardens with communal plots attract gardeners interested in the social aspects of gardening while non-neighborhood-bound gardens and gardens with individual plots attract gardeners interested in harvest and cultivation [

24].

20 of the 100 cases consist of an NGO or other type of non-profit structure playing a key role in providing expertise and guiding citizens or other citizen organizations. Interesting are the examples of urban forests in France, Luxembourg and Belgium mentioning the Akira Miyawaki method [

56] of fast growing of diverse urban forests and other methods following similar principles. In certain cases, we see non-profits offering training and opportunities for encouraging civic action to interested citizens and citizen groups.

Lastly, we observe other initiatives where citizens act within a capacity, such as the one of the parents or teachers. A few of the collected initiatives (e.g., Greece, France, Poland, Canada, Netherlands) consist of action taken for the greening of schoolyards through gardens, small allotments, and other interventions to depave. Green schoolyard can facilitate diverse behaviors and activities, provide sensory and embodied nature experiences, provide a restorative environment, support biodiversity, and provide a resilient environment that supports climate resilience and mitigates environmental nuisance [

54]. The Grenoble Schoolyard Initiative is a notable urban development project focused on transforming schoolyards in the city of Grenoble, France [

54]. The project aims to reimagine schoolyards as multifunctional spaces that not only cater to educational needs but also serve as vibrant community hubs. It involves comprehensive redesigns that prioritize elements such as greenery, recreational facilities, and innovative learning environments. By integrating sustainable features and fostering a sense of community ownership, the Grenoble Schoolyard Initiative exemplifies a forward-thinking approach to urban development, one that prioritizes the well-being and development of both students and the broader population. This project has served as an inspiring model for cities worldwide looking to create inclusive, dynamic, and environmentally conscious spaces within their urban landscapes.

4.1.2. Citizen and Authorities' Initiatives

28 out of the 100 initiatives are implemented in collaboration between local authorities and citizens. This collaboration materializes in different ways, which we could group under 2 categories:

The municipality creates a framework for citizen action (23 cases). This materialized with the municipality/local authority giving permits to citizens that wish to intervene in the public space by greening. In such cases the citizens decide on the space and intervention. The authority could also describe a set of urban greening activities eligible for a grant. In one case the local authority creates employment opportunities for artists and gardeners to intervene in public space.

The municipality is guided by citizens to decide on urban greening actions (5). As such we group cases of citizens pushing for green interventions through participatory budget or putting pressure on authorities to reutilize abandoned spaces or change plans for parking's or buildings to create common green spaces.

4.1.3. Private Sector Involvement

11 out of the 100 initiatives collected include the involvement of the private sector and notably local businesses. Two of them are in London and follow the Business Improvement District (BID) model [

57,

58]. BID It is a designated area within a city or town where local businesses collaborate to enhance the economic and physical environment. It operates through a self-imposed tax or fee collected from businesses within the district, which is then reinvested back into the community. The primary goal of a BID is to foster economic development, improve the overall attractiveness and vitality of the area, and address specific concerns shared by local businesses and property owners. This may include initiatives such as streetscape enhancements, marketing campaigns of green initiatives, security measures to protect green/public space, and events designed to increase vibrancy. By pooling resources and working collectively, BIDs play a pivotal role in revitalizing commercial areas, fostering a sense of community, and ultimately driving sustained growth in the local economy. They serve as a powerful model for public-private partnerships, illustrating the potential for businesses to proactively shape and improve the environments in which they operate. Other isolated cases among the 100 include funds given to the public for greening purposes as part of corporate responsibility strategies and involvement of small businesses in the rehabilitation of brownfield and abandoned areas.

4.2. Types of Urban Greening

Out of the 100 initiatives, 44 interventions referred to the creation of allotments, community gardens and agricultural land. This finding is interesting as it connects the need for green space with the primary need for access to food. 3 initiatives consist of the creation of green spaces connected to grey infrastructure.

When the private sector is involved (11 initiatives), we see a slightly different breakdown with more initiatives connected to gray infrastructure. 5 out of the 11 initiatives that are driven by schools or universities and their students and professors are allotments, community gardens or agricultural land. Out of the 49 initiatives entirely led by citizens with/or NGO involvement, 31 are allotments, community gardens or agricultural land. It gets clear that when citizens lead interventions to green the public space, they are driven (also) by the need to secure access to food.

Tables 3–6.

Types of greening associated with actors leading the initiative.

Tables 3–6.

Types of greening associated with actors leading the initiative.

| 100 citizen-led initiatives analyzed per type of greening |

| Building greens |

4 |

| Urban green areas connected to gray infrastructure |

34 |

| Parks and (semi)natural urban green areas, including urban forests |

15 |

| Allotments and community gardens |

44 |

| Agricultural land |

1 |

| Blue areas / Green areas for water management |

2 |

| Initiatives led or supported by NGOs analyzed per type of greening (out of 100) |

49 |

| Building greens |

- |

| Urban green areas connected to gray infrastructure |

10 |

| Parks and (semi)natural urban green areas, including urban forests |

8 |

| Allotments and community gardens |

31 |

| Agricultural land |

- |

| Blue areas / Green areas for water management |

- |

| Initiatives ran by schools/universities and their communities analyzed per type of greening (out of 100) |

11 |

| Building greens |

1 |

| Urban green areas connected to gray infrastructure |

4 |

| Parks and (semi)natural urban green areas, including urban forests |

1 |

| Allotments and community gardens |

5 |

| Agricultural land |

- |

| Blue areas / Green areas for water management |

- |

| Initiatives that were realized with private sector involvement analyzed per type of greening (out of 100) |

11 |

| Building greens |

- |

| Urban green areas connected to gray infrastructure |

4 |

| Parks and (semi)natural urban green areas, including urban forests |

3 |

| Allotments and community gardens |

3 |

| Agricultural land |

- |

4.3. Modes of Implementation and the Role of Authorities

The initiatives where municipalities and public authorities are involved, are highlighted in yellow in

Table 7. The role of the authorities can be interpreted as follows:

Providing funding

Providing a framework for action to citizens and small businesses (e.g., allowing citizens to intervene in the public space)

Legalizing citizen action (e.g., by accepting green spaces that are a result of occupation, protests or other)

Transferring part of their power to citizens (e.g., by making part of their budget participatory)

4.4. Categorization Based on the Incorporation of Smart Technologies

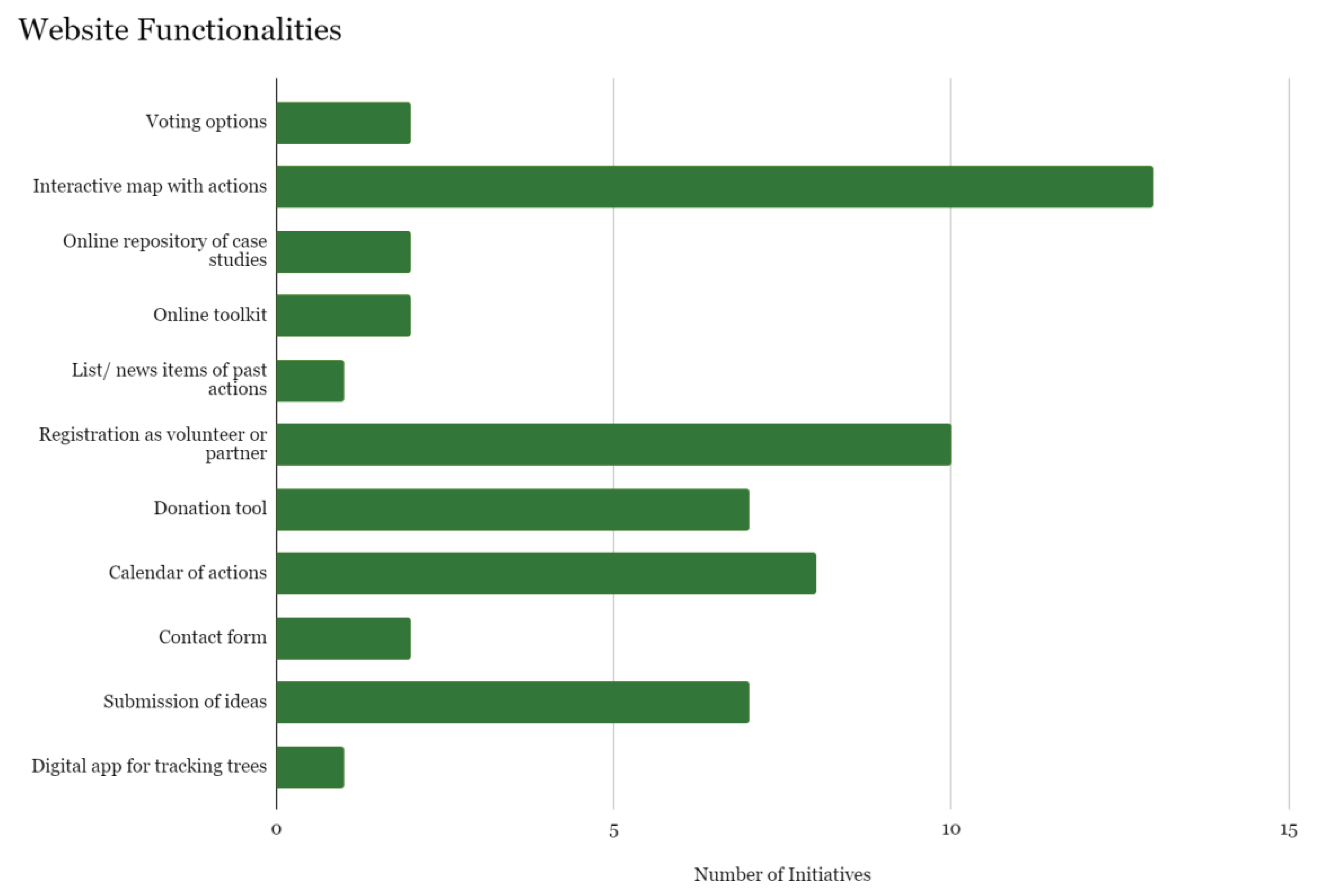

Upon evaluating the technological landscape adopted by these initiatives, we see that 46 out of 100 initiatives, a notable portion of the analyzed initiatives, have integrated smart technologies. Of those 46 initiatives, more than 36 of the initiatives have created a web-based platform, with a corresponding number of 5 featuring a user-friendly and interactive map interface. Furthermore, a considerable proportion of these initiatives have embraced social media channels as a means of communication.

Specifically, 10 of initiatives are actively using these platforms for outreach and engagement purposes, as they provide the users with the option to register as a volunteer or partner, while 8 of the initiatives’ websites include a calendar with the past actions. 7 of the initiatives have an interactive map of the initiatives and the other 7 initiatives allow their users to submit ideas for new actions.

Figure 2.

Functionalities of the urban greening websites/platforms.

Figure 2.

Functionalities of the urban greening websites/platforms.

5. Conclusions, Challenges and Future Outlook

The analysis of citizen-led initiatives showed the actual user needs. Rather than institutionalized and top-level planning, citizen-led initiatives address very real and often urgent needs of the communities. These grassroots efforts, fueled by local insight and passion, target immediate challenges faced by residents, ranging from food insecurity and access to green spaces and environmental conservation. These initiatives leverage the collective expertise, creativity, and resourcefulness of individuals to devise practical solutions. Whether through neighborhood urban farming, to urban greening programs, or advocacy addressed towards authorities for better or bigger green community infrastructure, these endeavors express the urgent needs on the ground. They show the remarkable impact that citizen-driven action can have in effecting positive change within communities.

We observe that most civic actions aimed at the creation of urban farms and food growing, demonstrating the pressuring needs for food securing and self-determination in communities. Initiatives also have better chances to scale up and multiply when public authorities provide a framework or a type of support for their development or when an NGO or other organization is available to provide expertise and mobilize citizens at various stages. Scaling up green initiatives involves navigating a range of factors to ensure their successful expansion and impact. From this study we see that clear frameworks, incentives, and regulations that promote sustainability encourage the adoption and expansion of green initiatives. In addition, engaging stakeholders, garnering local support, and fostering a sense of ownership are vital for successful scaling. Knowledge sharing of best practices, and lessons learned ensures that successful strategies can be replicated or adapted in other contexts, accelerating scaling efforts.

The recognition of varying degrees of policies for green space co-creating leads to the conclusion that certain countries (e.g., UK and USA), have a strong tradition in this regard. This deep-seated practice cultivates an environment conducive to many collaborative initiatives. This tradition of civic action for greening acts as a factor for the scaling up and multiplication of such efforts. We also observe NGOs and community leaders, place makers and architects playing a pivotal role.

Most of the initiatives that receive any type of support from a larger organization, being the municipality or a nonprofit with relevant expertise, are digitally documented through interactive maps, while most calls for further action and support are addressed through online platforms and social media. Integration of more advanced digital technologies in the future could enable accurate and real-time assessment of green spaces, facilitate community engagement, and inform evidence-based decision-making. By embracing innovative technologies and approaches, citizens can streamline processes and enhance efficiency in scaling up green initiatives. Also, robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms help track progress, identify challenges, and refine strategies for effective scaling.

Through this study, we investigated factors that encourage citizens to engage and lead urban greening initiatives, also through digital means. However, we recognize that the responsibility for advancing further digitization initiatives, monitoring, and scaling up greening in urban and larger levels lies with the public authorities. This pivotal role involves not just observing the ongoing technological landscape but also orchestrating strategies for widespread adoption and expansion. In addition, authorities bear the crucial task of ensuring that digitization efforts align with broader organizational goals, fostering seamless integration and maximizing the potential benefits of technological advancements across the spectrum. While the benefits of smart technologies for urban greening monitoring are substantial, challenges such as data privacy, data accuracy validation, and fair access to technology must be addressed. Collaborations among urban planners, technologists, researchers, and policy makers are crucial for designing effective monitoring systems. As cities continue to grow, the use of smart technologies can contribute to creating sustainable, resilient, and livable urban environments that prioritize the health and well-being of residents and ecosystems alike.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O., I.P.; methodology, E.O., I.P.; formal analysis, E.O., I.P.; investigation, E.O., I.P.; resources, E.O., I.P.; data curation, E.O., I.P.; writing—original draft preparation, E.O., I.P.; writing—review and editing, E.O., I.P.; C.K visualization, E.O., I.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table 9.

Locations and names of the studies initiatives.

Table 9.

Locations and names of the studies initiatives.

| Location (City, Country) |

Name of Initiative |

| Lisbon, Portugal |

Participatory Budget |

| Alberta, Canada |

Guerilla gardeners |

| Amsterdam, Netherlands |

'De Ruigi Hof'' nature association |

| Amsterdam, Netherlands |

Bio-receptive concrete as green wall |

| Melbourne, Australia |

Laneway Greening |

| Amsterdam, The Hague Netherlands |

Green Schoolyards |

| Athens, Greece |

Adopt your city, Pocket parks |

| Athens, Greece |

City interventions (''Παρεμβάσεις στην Πόλη'') |

| Athens, Greece |

Navarinou Park |

| Athens, Greece |

Urban Farmers (Aγρότες στην Πόλη) |

| San Sebastian, Spain |

Ulia Garden |

| Berlin, Germany |

Nomadisch Grün |

| Berlin, Germany |

Prinzessinnengarten |

| Berlin, Germany |

Tempelhofer Feld |

| Berlin, Germany |

CitiScapeLab |

| Berlin, Germany |

Volkspark Lichtenrade |

| Bristol, UK |

Avon Wildlife Trust |

| Brussels, Belgium |

Asiat Park |

| Buenos Aires, Argentina |

Huerta Luna garden |

| Buenos Aires, Argentina |

Vivera Organica in Rodrigo Bueno green and social housing development |

| Canada |

Eco-urban gardens |

| Canada, USA |

TD Bank's Green Streets Program |

| Cape Town, South Africa |

Abalimi Bezekhaya |

| Cape Town, South Africa |

Oranjezicht City Farm |

| Greece |

Green schoolyards |

| Chicago, USA |

NeighborSpace |

| Copenhagen, Denmark |

Bioteket |

| Copenhagen, Denmark |

Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Copenhagen, Denmark |

Garden in a night |

| New York, USA |

High Line |

| San Francisco, USA |

Hayes Valley Farm |

| Durban, South Africa |

Local communities improve river flow |

| Edinburgh, UK |

Duddingston Field Group |

| France, Belgium, Luxembourg |

Urban forests |

| São Paulo, Brazil |

Parque Augusta |

| Glasgow, Scotland |

Glasgow Community Gardens |

| Grenoble, France |

Greening of the street in front of the schools |

| Melbourne, Australia |

Pocket Parks |

| Mumbai, India |

Urban Leaves |

| New York, USA |

It's My Park Day |

| London, UK |

Community Garden |

| London, UK |

Curve Garden |

| London, UK |

Drummond BID |

| London, UK |

Green interventions through business Improvement District - Waterloo |

| London, UK |

Guerrilla gardening |

| London, UK |

London's DIY Streets |

| London, UK |

Paper garden |

| London, UK |

Skip Garden |

| London, UK |

The Edible Bus Stop |

| London's |

Capital Growth |

| Los Angeles, California |

Guerrilla gardening |

| Los Angeles, USA |

Los Angeles Community Garden Council |

| New York, USA |

MillionTreesNYC, USA |

| Los Angeles, USA |

Los Angeles TreePeople |

| Ιxelles, Belgium |

Planting permit |

| Manchester, UK |

Leaf Street Community Garden |

| Amsterdam, Netherlands |

ROEF - green roof festival |

| Melbourne, Australia |

3000 Acres |

| Melbourne, Australia |

CERES Community Environment Park |

| Barcelona, Spain |

Guide for green roofs to citizens |

| Milan, Italy |

Boscoincittà |

| Montreal, Canada |

Loyola Farm |

| Montreal, Canada |

NDG Food Depot |

| Montreal, Canada |

P.A.U.S.E -Urban Garden network in the university campus |

| Montreal, Canada |

Santropol Roulant |

| Netherlands |

Tiny forests |

| Curitiba, Brasil |

100 000 trees for Curitiba |

| Detroit,USA |

Detroit Future City's Field Guide to Working with Lots |

| Ilam, East Nepal |

Greening of commercial center |

| Madrid, Spain |

Huertos Urbanos |

| San Francisco, USA |

San Francisco's Pavement to Parks |

| Paris, France |

Greening of the street in front of the schools |

| Paris, France |

Greening Roofs |

| Philadelphia, USA |

Orchard Project |

| Paris, France |

Planting permit |

| Seattle, USA |

Seattle P-Patch Program |

| Philladelphia, USA |

Gibbsboro Community Garden |

| Portland, USA |

Depave |

| Portland, USA |

Portland Neighborhood Greening Projects |

| Singapore |

Singapore's Community in Bloom |

| Rotterdam, Netherlands |

Voedseltuin Rotterdam |

| Rotterdam, Netherlands |

Educational Gardens |

| San Francisco, USA |

Alemany Farm |

| Philadelphia, USA |

Tree Tenders Program |

| Philadelphia, USA |

Philadelphia LandCare Program |

| San Francisco, USA |

San Francisco's Friends of the Urban Forest |

| Los Angeles, USA |

Los Angeles Green Alleys |

| Freetown, Sierra Leone |

The TreeTown campaign |

| Seattle, USA |

Seattle's Neighborhood Street Fund |

| Seattle, USA |

Beacon Food Forest |

| New York, USA |

NYC GreenThumb |

| Reggio Emilia, Italy |

Regulation for citizenship labs |

| San Francisco, USA |

Salesforce Park |

| Stockholm, Sweden |

Stockholm's Inner-City Gardens |

| Tampere, Finland |

Medow planting in the city |

| Toronto, Canada |

Depave Paradise |

| Toronto, Canada |

Toronto Green Community |

| Trento, Italy |

Comun'Orto |

| Vancouver, Canada |

CityStudio Greenest City Projects |

| Warsaw, Poland |

Green schoolyards |

References

- World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities UN-Habitat, https://unhabitat.org/world-cities-report-2022-envisaging-the-future-of-cities.

- Quaranta, E., Dorati, C., Pistocchi, A.: Water, energy and climate benefits of urban greening throughout Europe under different climatic scenarios. Sci Rep. 11, 1–10 (2021). [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC: UN Climate Change Conference - United Arab Emirates UNFCCC, https://unfccc.int/cop28.

- Kleerekoper, L., van Esch, M., Salcedo, T.B.: How to make a city climate-proof, addressing the urban heat island effect. Resour Conserv Recycl. 64, 30–38 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Kakderi, C., Oikonomaki, E., Papadaki, I.: Smart and Resilient Urban Futures for Sustainability in the Post COVID-19 Era: A Review of Policy Responses on Urban Mobility. Sustainability. 13, 6486 (2021). [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficient-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive_en.

- US EPA, O.P.: Green Building Standards, https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/green-building-standards, (2014).

- European Commission: Level(s) - European Commission, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/levels_en.

- U.S. Green Building Council: Guide to LEED Certification: Commercial, https://www.usgbc.org/tools/leed-certification/commercial.

- BREEAM - BRE Group, https://bregroup.com/products/breeam/.

- Home - Green Building Council of Australia, https://new.gbca.org.au/.

- Moreno, M., Ortiz, P., Ortiz, R.: Analysis of the impact of green urban areas in historic fortified cities using Landsat historical series and Normalized Difference Indices. Sci Rep. 13, 8982 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jul 4, P. por S.C., News, 2023: Lisbon leading the regeneration of european historic areas, https://smart-cities.pt/news/lisbon-leading-the-regeneration-04-07of-european-historic-areas/, (2023). 2023.

- Komninos, N.: Smart Cities and Connected Intelligence: Platforms, Ecosystems and Network Effects. Routledge, London (2019).

- European Commission: Citizen Science: an essential ally for sustainable cities, https://rea.ec.europa.eu/news/citizen-science-essential-ally-sustainable-cities-2023-10-27_en.

- Alberro, H.: Urban greening can save species, cool warming cities, and make us happy, http://theconversation.com/urban-greening-can-save-species-cool-warming-cities-and-make-us-happy-116000, (2019).

- Bowler, D.E., Buyung-Ali, L., Knight, T.M., Pullin, A.S.: Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landsc Urban Plan. 97, 147–155 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Wang, X.: Reexamine the value of urban pocket parks under the impact of the COVID-19. Urban For Urban Green. 64, 127294 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Slingerland, G.: From the ground up: Local efforts to create resilient cities, by Alison Sant. J Urban Aff. 1–2 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Camps-Calvet, M., Langemeyer, J., Calvet-Mir, L., Gómez-Baggethun, E.: Ecosystem services provided by urban gardens in Barcelona, Spain: Insights for policy and planning. Environ Sci Policy. 62, 14–23 (2016). [CrossRef]

- ‘Yotti’ Kingsley, J., Townsend, M.: ‘Dig In’ to Social Capital: Community Gardens as Mechanisms for Growing Urban Social Connectedness. Urban Policy and Research. 24, 525–537 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Peters, K., Elands, B., Buijs, A.: Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban For Urban Green. 9, 93–100 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Teig, E., Amulya, J., Bardwell, L., Buchenau, M., Marshall, J.A., Litt, J.S.: Collective efficacy in Denver, Colorado: Strengthening neighborhoods and health through community gardens. Health Place. 15, 1115–1122 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Veen, E.J., Bock, B.B., den Berg, W., Visser, A.J., Wiskerke, J.S.C.: Community gardening and social cohesion: different designs, different motivations. Local Environ. 21, 1271–1287 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Westphal, L.M. Social Aspects of Urban Forestry: Urban Greening and Social Benefits: a Study of Empowerment Outcomes. Journal of Arboriculture 2003, 29, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, V., Bamkole, O.: The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16, 452 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Jan Gehl: Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. Island Press (2012).

- Jan Gehl: Cities for People. Opensource (2023).

- Jane Jacobs: The death and life of great American cities. New York : Random House (1961).

- Charles Montgomery: Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design. Farrar, Straus and Giroux | New York (2013).

- Kakderi, C., Komninos, N., Panori, A., Oikonomaki, E.: Next City: Learning from Cities during COVID-19 to Tackle Climate Change. Sustainability. 13, 3158 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F., Massetti, L., Calaza-Martínez, P., Cariñanos, P., Dobbs, C., Ostoić, S.K., Marin, A.M., Pearlmutter, D., Saaroni, H., Šaulienė, I., Simoneti, M., Verlič, A., Vuletić, D., Sanesi, G.: Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: An international exploratory study. Urban For Urban Green. 56, 126888 (2020). [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Biodiversity strategy for 2030, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en, (2023).

- ICLEI - Local Governments for Sustainability, https://iclei.org/.

- European Environment Agency: Urban tree cover — European Environment Agency, https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/dashboards/urban-tree-cover.

- European Environment Agency: How green are European cities? Green space key to well-being – but access varies, https://www.eea.europa.eu/highlights/how-green-are-european-cities.

- Ulia Garden - New European Bauhaus, https://2021.prizes.new-european-bauhaus.eu/node/269248.

- Global Covenant of Mayors: Data Portal for Cities, https://dataportalforcities.org/.

- UNFCCC: Key aspects of the Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/most-requested/key-aspects-of-the-paris-agreement.

- van den Bogerd, N., Hovinga, D., Hiemstra, J.A., Maas, J.: The Potential of Green Schoolyards for Healthy Child Development: A Conceptual Framework. Forests. 14, 660 (2023). [CrossRef]

- ParkScore® Index 2020.

- San Francisco - 10 minute city.

- UN-Habitat: Greener Cities Partnership (UN-Habitat and UN Environment), https://unhabitat.org/greener-cities-partnership.

- C40: C40 Cities - A global network of mayors taking urgent climate action, https://www.c40.org/.

- Global Covenant of Mayors, https://www.globalcovenantofmayors.org/.

- Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A. eds: Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2017).

- Urban Greening Platform.

- Berlin-Brandenburg Institute of Advanced Biodiversity Research (BBIB).

- Stefanie Waldek: Satellite imagery captures wildfires breaking across Greece , (2023).

- Manley, K., Nyelele, C., Egoh, B.N.: A review of machine learning and big data applications in addressing ecosystem service research gaps. Ecosyst Serv. 57, 101478 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, S., Olazabal, M., Castro, A.J., Pascual, U.: Global mapping of urban nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation. Nat Sustain. 6, 458–469 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Hamel, P., Tardieu, L., Remme, R.P., Han, B., Ren, H.: A geospatial model of nature-based recreation for urban planning: Case study of Paris, France. Land use policy. 117, 106107 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Placemaking Week Europe 2023.

- van den Bogerd, N., Hovinga, D., Hiemstra, J.A., Maas, J.: The Potential of Green Schoolyards for Healthy Child Development: A Conceptual Framework. Forests. 14, 660 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Elli Ismailidou: Ναυαρίνου: Το πάρκο – πάρκινγκ έκλεισε δύο χρόνια ζωής, (2011).

- Miyawaki, A.: Restoration of living environment based on vegetation ecology: Theory and practice. Ecol Res. 19, 83–90 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Paulo Coelho Ávila: Desenvolvimento urbano por meio dos Business Improvement District.

- We are Waterloo, https://wearewaterloo.co.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).