Submitted:

05 March 2024

Posted:

06 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Impact of GSLs on the Cartilage Homeostasis

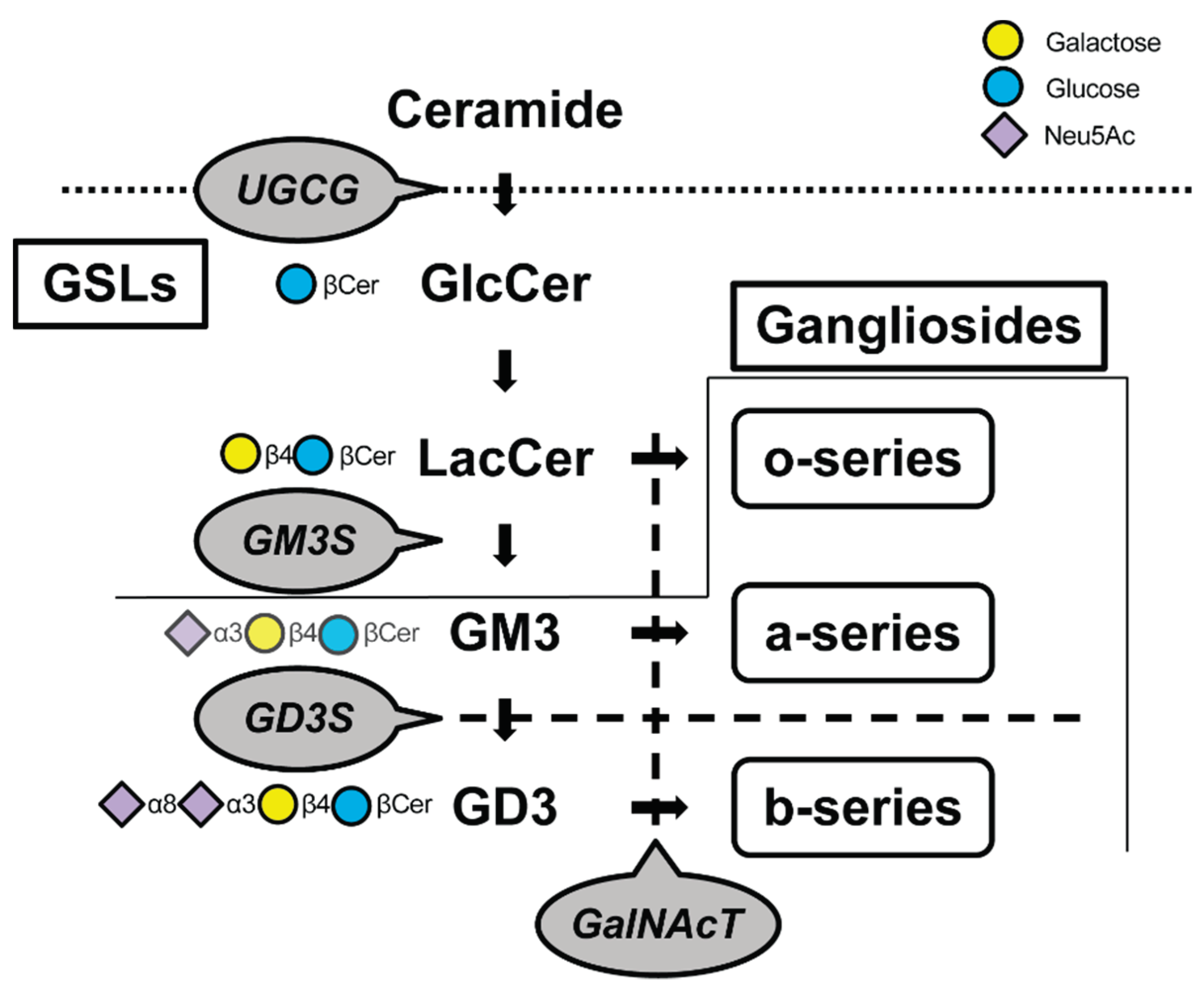

| Glycosyltransferase | Lost glycolipids | Consequences of depletion of its glycolipid | References |

| UGCG (Glucosylceramide synthase) |

GSLs |

Embryonic death. Reduced insulative capacity of the myelin sheath. Col2-Ugcg-/- mice enhance the development of OA | [16,17,19,37,38,39] |

| ST3GalⅣ (GM3S) |

Gangliosides other than the o-series | GM3 plays an immunologic role. Heightened sensitivity to insulin. Severely reduced CD4+ T cell proliferative response and cytokine production. Promote OA and RA but cartilage regeneration | [34,40,41,42,43] |

| ST8SiaⅠ (GD3S) |

b-series ganglioside | Tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens (TACA) in neuro-ectoderm-derived cancers. Suppression of age-related bone loss. Deteriorates OA with aging | [33,44,45,46,47] |

| GalNAcT (GM2/GD2S) |

Almost all gangliosides except GM3, GD3, and GT3 | Age-dependent neurodegeneration, movement disorders associated with it. Defects in spermatogenesis and learning. Exacerbating OA progression | [33,48,49,50] |

3. Role of GSLs in Cartilage Repair and Differentiation Processes

3.1. Endogenous Potential to Heal in Articular Cartilage

3.2. Changes in the Glycan Structure during Chondrogenic Differentiation

4. Cell Sources

4.1. Autologous Cartilage/Chondrocyte Implantation

4.2. Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

4.3. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Su, J. Articular Cartilage Repair Biomaterials: Strategies and Applications. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 24, 100948. [CrossRef]

- Muthu, S.; Korpershoek, J.V.; Novais, E.J.; Tawy, G.F.; Hollander, A.P.; Martin, I. Failure of Cartilage Regeneration: Emerging Hypotheses and Related Therapeutic Strategies. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 403–416. [CrossRef]

- Peat, G.; Thomas, M.J. Osteoarthritis Year in Review 2020: Epidemiology & Therapy. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021, 29, 180–189. [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.R.; Jamal, S.; Riad, M.; Castrejon, I.; Malfait, A.-M.; Block, J.A.; Pincus, T. Disease Burden in Osteoarthritis Is Similar to That of Rheumatoid Arthritis at Initial Rheumatology Visit and Significantly Greater Six Months Later. Arthritis Rheumatol. Hoboken NJ 2019, 71, 1276–1284. [CrossRef]

- Dieleman, J.L.; Cao, J.; Chapin, A.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, A.; Horst, C.; Kaldjian, A.; Matyasz, T.; Scott, K.W.; et al. US Health Care Spending by Payer and Health Condition, 1996-2016. JAMA 2020, 323, 863–884. [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.J.; Beier, F.; Young, D.A.; Loughlin, J. Interplay between Genetics and Epigenetics in Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 268–281. [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, A.; Lane, J.G.; Longo, U.G.; Dallo, I. Joint Function Preservation: A Focus on the Osteochondral Unit; Springer Nature, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-82958-2.

- David, M.J.; Portoukalian, J.; Rebbaa, A.; Vignon, E.; Carret, J.P.; Richard, M. Characterization of Gangliosides from Normal and Osteoarthritic Human Articular Cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 1993, 36, 938–942.

- David, M.J.; Hellio, M.P.; Portoukalian, J.; Richard, M.; Caton, J.; Vignon, E. Gangliosides from Normal and Osteoarthritic Joints. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 1995, 43, 133–135.

- Bonner, W.M.; Jonsson, H.; Malanos, C.; Bryant, M. Changes in the Lipids of Human Articular Cartilage with Age. Arthritis Rheum. 1975, 18, 461–473. [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, S.; Hirabayashi, Y. Glucosylceramide Synthase and Glycosphingolipid Synthesis. Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8, 198–202. [CrossRef]

- Varki, A. Biological Roles of Glycans. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 3–49. [CrossRef]

- Gault, C.R.; Obeid, L.M.; Hannun, Y.A. An Overview of Sphingolipid Metabolism: From Synthesis to Breakdown. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 688, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Degroote, S.; Wolthoorn, J.; van Meer, G. The Cell Biology of Glycosphingolipids. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004, 15, 375–387. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Allende, M.L.; Kalkofen, D.N.; Werth, N.; Sandhoff, K.; Proia, R.L. Conditional LoxP-Flanked Glucosylceramide Synthase Allele Controlling Glycosphingolipid Synthesis. Genes. N. Y. N 2000 2005, 43, 175–180. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Wada, R.; Proia, R.L. Early Developmental Expression of the Gene Encoding Glucosylceramide Synthase, the Enzyme Controlling the First Committed Step of Glycosphingolipid Synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1573, 236–240.

- Yamashita, T.; Wada, R.; Sasaki, T.; Deng, C.; Bierfreund, U.; Sandhoff, K.; Proia, R.L. A Vital Role for Glycosphingolipid Synthesis during Development and Differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 9142–9147.

- Ichikawa, S.; Hirabayashi, Y. Glucosylceramide Synthase and Glycosphingolipid Synthesis. Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8, 198–202. [CrossRef]

- Seito, N.; Yamashita, T.; Tsukuda, Y.; Matsui, Y.; Urita, A.; Onodera, T.; Mizutani, T.; Haga, H.; Fujitani, N.; Shinohara, Y.; et al. Interruption of Glycosphingolipid Synthesis Enhances Osteoarthritis Development in Mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 2579–2588. [CrossRef]

- Khavandgar, Z.; Murshed, M. Sphingolipid Metabolism and Its Role in the Skeletal Tissues. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2015, 72, 959–969. [CrossRef]

- Reunanen, N.; Westermarck, J.; Häkkinen, L.; Holmström, T.H.; Elo, I.; Eriksson, J.E.; Kähäri, V.M. Enhancement of Fibroblast Collagenase (Matrix Metalloproteinase-1) Gene Expression by Ceramide Is Mediated by Extracellular Signal-Regulated and Stress-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 5137–5145. [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, M.; Rolland, G.; Léonce, S.; Thomas, M.; Lesur, C.; Pérez, V.; de Nanteuil, G.; Bonnet, J. Effects of Ceramide on Apoptosis, Proteoglycan Degradation, and Matrix Metalloproteinase Expression in Rabbit Articular Cartilage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 267, 438–444. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Gu, J.; Xu, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B. The Protective Role of Glucocerebrosidase/Ceramide in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Connect. Tissue Res. 2022, 63, 625–633. [CrossRef]

- Hakomori, S. Structure and Function of Glycosphingolipids and Sphingolipids: Recollections and Future Trends. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1780, 325–346. [CrossRef]

- Iwabuchi, K.; Yamamura, S.; Prinetti, A.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S. GM3-Enriched Microdomain Involved in Cell Adhesion and Signal Transduction through Carbohydrate-Carbohydrate Interaction in Mouse Melanoma B16 Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 9130–9138.

- Kojima, N.; Shiota, M.; Sadahira, Y.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S. Cell Adhesion in a Dynamic Flow System as Compared to Static System. Glycosphingolipid-Glycosphingolipid Interaction in the Dynamic System Predominates over Lectin- or Integrin-Based Mechanisms in Adhesion of B16 Melanoma Cells to Non-Activated Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 17264–17270.

- Kojima, N.; Hakomori, S. Specific Interaction between Gangliotriaosylceramide (Gg3) and Sialosyllactosylceramide (GM3) as a Basis for Specific Cellular Recognition between Lymphoma and Melanoma Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 20159–20162.

- Ferrari, G.; Anderson, B.L.; Stephens, R.M.; Kaplan, D.R.; Greene, L.A. Prevention of Apoptotic Neuronal Death by GM1 Ganglioside. Involvement of Trk Neurotrophin Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 3074–3080. [CrossRef]

- Fighera, M.R.; Royes, L.F.F.; Furian, A.F.; Oliveira, M.S.; Fiorenza, N.G.; Frussa-Filho, R.; Petry, J.C.; Coelho, R.C.; Mello, C.F. GM1 Ganglioside Prevents Seizures, Na+,K+-ATPase Activity Inhibition and Oxidative Stress Induced by Glutaric Acid and Pentylenetetrazole. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 22, 611–623. [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, T.V.; Zakharova, I.O.; Furaev, V.V.; Rychkova, M.P.; Avrova, N.F. Neuroprotective Effect of Ganglioside GM1 on the Cytotoxic Action of Hydrogen Peroxide and Amyloid Beta-Peptide in PC12 Cells. Neurochem. Res. 2007, 32, 1302–1313. [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, L.; Venerando, R.; Miotto, G.; Alexandre, A. Ganglioside GM1 Protection from Apoptosis of Rat Heart Fibroblasts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 370, 156–162. [CrossRef]

- Sergent, O.; Pereira, M.; Belhomme, C.; Chevanne, M.; Huc, L.; Lagadic-Gossmann, D. Role for Membrane Fluidity in Ethanol-Induced Oxidative Stress of Primary Rat Hepatocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 313, 104–111. [CrossRef]

- Momma, D.; Onodera, T.; Homan, K.; Matsubara, S.; Sasazawa, F.; Furukawa, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Yamashita, T.; Iwasaki, N. Coordinated Existence of Multiple Gangliosides Is Required for Cartilage Metabolism. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019, 27, 314–325. [CrossRef]

- Nagafuku, M.; Okuyama, K.; Onimaru, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Odagiri, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Iwasaki, K.; Fujiwara, M.; Takayanagi, M.; Ohno, I.; et al. CD4 and CD8 T Cells Require Different Membrane Gangliosides for Activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, E336-342. [CrossRef]

- Shikhman, A.R.; Brinson, D.C.; Lotz, M. Profile of Glycosaminoglycan-Degrading Glycosidases and Glycoside Sulfatases Secreted by Human Articular Chondrocytes in Homeostasis and Inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43, 1307–1314. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-W.; Popat, S.D.; Liu, T.-W.; Tsai, K.-C.; Ho, M.-J.; Chen, W.-H.; Yang, A.-S.; Lin, C.-H. Development of GlcNAc-Inspired Iminocyclitiols as Potent and Selective N-Acetyl-Beta-Hexosaminidase Inhibitors. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 489–497. [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, S.; Onodera, T.; Maeda, E.; Momma, D.; Matsuoka, M.; Homan, K.; Ohashi, T.; Iwasaki, N. Depletion of Glycosphingolipids Induces Excessive Response of Chondrocytes under Mechanical Stress. J. Biomech. 2019, 94, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Kolesnick, R.; Golde, D.W. The Sphingomyelin Pathway in Tumor Necrosis Factor and Interleukin-1 Signaling. Cell 1994, 77, 325–328. [CrossRef]

- Hannun, Y.A. The Sphingomyelin Cycle and the Second Messenger Function of Ceramide. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 3125–3128.

- Sasazawa, F.; Onodera, T.; Yamashita, T.; Seito, N.; Tsukuda, Y.; Fujitani, N.; Shinohara, Y.; Iwasaki, N. Depletion of Gangliosides Enhances Cartilage Degradation in Mice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014, 22, 313–322. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Hashiramoto, A.; Haluzik, M.; Mizukami, H.; Beck, S.; Norton, A.; Kono, M.; Tsuji, S.; Daniotti, J.L.; Werth, N.; et al. Enhanced Insulin Sensitivity in Mice Lacking Ganglioside GM3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 3445–3449. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, M.; Onodera, T.; Homan, K.; Sasazawa, F.; Furukawa, J.-I.; Momma, D.; Baba, R.; Hontani, K.; Joutoku, Z.; Matsubara, S.; et al. Depletion of Gangliosides Enhances Articular Cartilage Repair in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43729. [CrossRef]

- Tsukuda, Y.; Iwasaki, N.; Seito, N.; Kanayama, M.; Fujitani, N.; Shinohara, Y.; Kasahara, Y.; Onodera, T.; Suzuki, K.; Asano, T.; et al. Ganglioside GM3 Has an Essential Role in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Rheumatoid Arthritis. PloS One 2012, 7, e40136. [CrossRef]

- Kasprowicz, A.; Sophie, G.-D.; Lagadec, C.; Delannoy, P. Role of GD3 Synthase ST8Sia I in Cancers. Cancers 2022, 14, 1299. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Pang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, C.; Du, G. Ganglioside GD3 Synthase (GD3S), a Novel Cancer Drug Target. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 713–720. [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Hu, X.; Ren, S.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Wu, K.; Yang, Z.; Yang, W.; He, G.; Li, X. The Biological Role and Immunotherapy of Gangliosides and GD3 Synthase in Cancers. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1076862. [CrossRef]

- Yo, S.; Hamamura, K.; Mishima, Y.; Hamajima, K.; Mori, H.; Furukawa, K.; Kondo, H.; Tanaka, K.; Sato, T.; Miyazawa, K.; et al. Deficiency of GD3 Synthase in Mice Resulting in the Attenuation of Bone Loss with Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2825. [CrossRef]

- McGonigal, R.; Barrie, J.A.; Yao, D.; Black, L.E.; McLaughlin, M.; Willison, H.J. Neuronally Expressed A-Series Gangliosides Are Sufficient to Prevent the Lethal Age-Dependent Phenotype in GM3-Only Expressing Mice. J. Neurochem. 2021, 158, 217–232. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, K.A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Kawai, H.; Crawford, T.O.; Proia, R.L.; Griffin, J.W.; Schnaar, R.L. Mice Lacking Complex Gangliosides Develop Wallerian Degeneration and Myelination Defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 7532–7537. [CrossRef]

- Chiavegatto, S.; Sun, J.; Nelson, R.J.; Schnaar, R.L. A Functional Role for Complex Gangliosides: Motor Deficits in GM2/GD2 Synthase Knockout Mice. Exp. Neurol. 2000, 166, 227–234. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, M.; Onodera, T.; Sasazawa, F.; Momma, D.; Baba, R.; Hontani, K.; Iwasaki, N. An Articular Cartilage Repair Model in Common C57Bl/6 Mice. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2015, 21, 767–772. [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.; Wu, G.; Wang, J.; Lu, L.; Wang, J.; Wei, H.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Y.; Mo, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Inhibition of Fibroblast Activation Protein Ameliorates Cartilage Matrix Degradation and Osteoarthritis Progression. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 3. [CrossRef]

- Molin, A.N.; Contentin, R.; Angelozzi, M.; Karvande, A.; Kc, R.; Haseeb, A.; Voskamp, C.; de Charleroy, C.; Lefebvre, V. Skeletal Growth Is Enhanced by a Shared Role for SOX8 and SOX9 in Promoting Reserve Chondrocyte Commitment to Columnar Proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2316969121. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Lu, H. 3D-Printed Extracellular Matrix/Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate Hydrogel Incorporating the Anti-Inflammatory Phytomolecule Honokiol for Regeneration of Osteochondral Defects. Am. J. Sports Med. 2020, 48, 2808–2818. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Urita, A.; Onodera, T.; Hishimura, R.; Nonoyama, T.; Hamasaki, M.; Liang, D.; Homan, K.; Gong, J.P.; Iwasaki, N. Ultrapurified Alginate Gel Containing Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate Enhances Cartilage and Bone Regeneration on Osteochondral Defects in a Rabbit Model. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 2199–2210. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dai, W.; Gao, C.; Wei, W.; Huang, R.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Cai, Q. Multileveled Hierarchical Hydrogel with Continuous Biophysical and Biochemical Gradients for Enhanced Repair of Full-Thickness Osteochondral Defect. Adv. Mater. Deerfield Beach Fla 2023, 35, e2209565. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Han, X.; Li, Z.; Bian, S.; Zeng, W.; Ding, M.; Liang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Molecular Co-Assembled Strategy Tuning Protein Conformation for Cartilage Regeneration. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1488. [CrossRef]

- González Vázquez, A.G.; Blokpoel Ferreras, L.A.; Bennett, K.E.; Casey, S.M.; Brama, P.A.; O’Brien, F.J. Systematic Comparison of Biomaterials-Based Strategies for Osteochondral and Chondral Repair in Large Animal Models. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, e2100878. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, B.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Liang, K.; Fan, Z.; Li, J.J.; Niu, Y.; He, Z.; Li, H.; et al. In Situ Self-Assembled Organoid for Osteochondral Tissue Regeneration with Dual Functional Units. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 27, 200–215. [CrossRef]

- Ibaraki, K.; Hayashi, S.; Kanzaki, N.; Hashimoto, S.; Kihara, S.; Haneda, M.; Takeuchi, K.; Niikura, T.; Kuroda, R. Deletion of P21 Expression Accelerates Cartilage Tissue Repair via Chondrocyte Proliferation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 2236–2242. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, K.; Hettinghouse, A.; Liu, C. Atsttrin Promotes Cartilage Repair Primarily Through TNFR2-Akt Pathway. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 577572. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xu, J.; Schwab, A.; Tong, W.; Xu, J.; Zheng, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Chen, Z.; et al. Engineered Biochemical Cues of Regenerative Biomaterials to Enhance Endogenous Stem/Progenitor Cells (ESPCs)-Mediated Articular Cartilage Repair. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 26, 490–512. [CrossRef]

- Massengale, M.; Massengale, J.L.; Benson, C.R.; Baryawno, N.; Oki, T.; Steinhauser, M.L.; Wang, A.; Balani, D.; Oh, L.S.; Randolph, M.A.; et al. Adult Prg4+ Progenitors Repair Long-Term Articular Cartilage Wounds in Vivo. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e167858. [CrossRef]

- Trengove, A.; Duchi, S.; Onofrillo, C.; Sooriyaaratchi, D.; Di Bella, C.; O’Connor, A.J. Bridging Bench to Body: Ex Vivo Models to Understand Articular Cartilage Repair. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 86, 103065. [CrossRef]

- Fukaya, N.; Ito, M.; Iwata, H.; Yamagata, T. Characterization of the Glycosphingolipids of Pig Cortical Bone and Cartilage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1989, 1004, 108–116. [CrossRef]

- Homan, K.; Onodera, T.; Hanamatsu, H.; Furukawa, J.; Momma, D.; Matsuoka, M.; Iwasaki, N. Articular Cartilage Corefucosylation Regulates Tissue Resilience in Osteoarthritis. eLife 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.-W.; Kim, S.-J.; Choi, H.-J.; Kim, K.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, H.-J.; Ko, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-C.; Suzuki, A.; et al. Ganglioside GM3 Inhibits VEGF/VEGFR-2-Mediated Angiogenesis: Direct Interaction of GM3 with VEGFR-2. Glycobiology 2009, 19, 229–239. [CrossRef]

- Kabayama, K.; Sato, T.; Saito, K.; Loberto, N.; Prinetti, A.; Sonnino, S.; Kinjo, M.; Igarashi, Y.; Inokuchi, J. Dissociation of the Insulin Receptor and Caveolin-1 Complex by Ganglioside GM3 in the State of Insulin Resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 13678–13683. [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N.; Yoon, S.-J.; Itoh, K.; Nakayama, K. Tyrosine Kinase Activity of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Is Regulated by GM3 Binding through Carbohydrate to Carbohydrate Interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 6147–6155. [CrossRef]

- DeLise, A.M.; Fischer, L.; Tuan, R.S. Cellular Interactions and Signaling in Cartilage Development. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2000, 8, 309–334. [CrossRef]

- Vainieri, M.L.; Lolli, A.; Kops, N.; D’Atri, D.; Eglin, D.; Yayon, A.; Alini, M.; Grad, S.; Sivasubramaniyan, K.; van Osch, G.J.V.M. Evaluation of Biomimetic Hyaluronic-Based Hydrogels with Enhanced Endogenous Cell Recruitment and Cartilage Matrix Formation. Acta Biomater. 2020, 101, 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.R.; Patel, J.M.; Locke, R.C.; Eby, M.R.; Saleh, K.S.; Davidson, M.D.; Sennett, M.L.; Zlotnick, H.M.; Chang, A.H.; Carey, J.L.; et al. Nanofibrous Hyaluronic Acid Scaffolds Delivering TGF-Β3 and SDF-1α for Articular Cartilage Repair in a Large Animal Model. Acta Biomater. 2021, 126, 170–182. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Lin, Z.; Makarcyzk, M.J.; Riewruja, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Clark, K.L.; Li, E.; Liu, S.; et al. Differences in the Intrinsic Chondrogenic Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and iPSC-Derived Multipotent Cells. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1112. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jin, M.; Sun, K.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Shi, J.; Liu, P.; Yao, H.; Wang, D.-A. Type II Collagen Scaffolds Repair Critical-Sized Osteochondral Defects under Induced Conditions of Osteoarthritis in Rat Knee Joints via Inhibiting TGF-β-Smad1/5/8 Signaling Pathway. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 35, 416–428. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Wei, Y.; Zeng, C.; Yang, G.; Dong, C.; Wan, W.; Chen, S. Hierarchically Assembled Nanofiber Scaffold Guides Long Bone Regeneration by Promoting Osteogenic/Chondrogenic Differentiation of Endogenous Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Small Weinh. Bergstr. Ger. 2024, e2309868. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xu, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Zheng, B.; Chen, M.; Ke, Q.; Long, J. Unleashing the Power of Immune Checkpoints: Post-Translational Modification of Novel Molecules and Clinical Applications. Cancer Lett. 2024, 216758. [CrossRef]

- Alghazali, R.; Nugud, A.; El-Serafi, A. Glycan Modifications as Regulators of Stem Cell Fate. Biology 2024, 13, 76. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, H.; Tang, F.; Yu, H.; Xia, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; et al. Site- and Stereoselective Glycomodification of Biomolecules through Carbohydrate-Promoted Pictet-Spengler Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2024, e202401394. [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, J.; Shinohara, Y.; Kuramoto, H.; Miura, Y.; Shimaoka, H.; Kurogochi, M.; Nakano, M.; Nishimura, S.-I. Comprehensive Approach to Structural and Functional Glycomics Based on Chemoselective Glycoblotting and Sequential Tag Conversion. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 1094–1101. [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, T.; Miwa, Y.; Kimata, K.; Ikawa, Y. A Chondrogenic Cell Line Derived from a Differentiating Culture of AT805 Teratocarcinoma Cells. Cell Differ. Dev. Off. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Biol. 1990, 30, 109–116.

- Ishihara, T.; Kakiya, K.; Takahashi, K.; Miwa, H.; Rokushima, M.; Yoshinaga, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Ito, T.; Togame, H.; Takemoto, H.; et al. Discovery of Novel Differentiation Markers in the Early Stage of Chondrogenesis by Glycoform-Focused Reverse Proteomics and Genomics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1840, 645–655. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.Q.; Nakashima, K.; Iwamoto, M.; Kato, Y. Stimulation by Concanavalin A of Cartilage-Matrix Proteoglycan Synthesis in Chondrocyte Cultures. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 10125–10131.

- Yan, W.; Pan, H.; Ishida, H.; Nakashima, K.; Suzuki, F.; Nishimura, M.; Jikko, A.; Oda, R.; Kato, Y. Effects of Concanavalin A on Chondrocyte Hypertrophy and Matrix Calcification. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 7833–7840.

- Homan, K.; Hanamatsu, H.; Furukawa, J.-I.; Okada, K.; Yokota, I.; Onodera, T.; Iwasaki, N. Alteration of the Total Cellular Glycome during Late Differentiation of Chondrocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, E3546. [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Fu, D.; Zhang, T.; Ma, S.; Zhou, F. Microgel-Modified Bilayered Hydrogels Dramatically Boosting Load-Bearing and Lubrication. ACS Macro Lett. 2023, 12, 1450–1456. [CrossRef]

- Alkaya, D.; Gurcan, C.; Kilic, P.; Yilmazer, A.; Gurman, G. Where Is Human-Based Cellular Pharmaceutical R&D Taking Us in Cartilage Regeneration? 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 161. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Liu, W.; Sun, C.; Wang, Q.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Shao, Z.; Wang, B. Endogenous Repair and Regeneration of Injured Articular Cartilage: A Challenging but Promising Therapeutic Strategy. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 886–901. [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Baroncini, A.; Bell, A.; Hildebrand, F.; Schenker, H. Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis Is Effective for Focal Chondral Defects of the Knee. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9328. [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Eschweiler, J.; Götze, C.; Hildebrand, F.; Betsch, M. Prognostic Factors for the Management of Chondral Defects of the Knee and Ankle Joint: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. Off. Publ. Eur. Trauma Soc. 2023, 49, 723–745. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, J.; Kraeutler, M.J.; Fasulo, S.M.; Belk, J.W.; Mulcahey, M.K.; Scillia, A.J.; McCulloch, P.C. Cartilage Repair of the Tibiofemoral Joint With Versus Without Concomitant Osteotomy: A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2023, 11, 23259671231151707. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, X.; Lin, Q.; Xing, Y.; Yang, W.; Duan, W.; Wei, X. Treatment of Articular Cartilage Defects: A Descriptive Analysis of Clinical Characteristics and Global Trends Reported from 2001 to 2020. Cartilage 2023, 19476035231205695. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, J.; Orozco, E.; Keeter, C.; Scillia, A.J.; Harris, J.D.; Kraeutler, M.J. Microfracture of Acetabular Chondral Lesions Is Not Superior to Other Cartilage Repair Techniques in Patients With Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 2024, 40, 602–611. [CrossRef]

- Götze, C.; Nieder, C.; Felder, H.; Migliorini, F. AMIC for Focal Osteochondral Defect of the Talar Shoulder. Life Basel Switz. 2020, 10, 328. [CrossRef]

- Waltenspül, M.; Suter, C.; Ackermann, J.; Kühne, N.; Fucentese, S.F. Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC) for Isolated Retropatellar Cartilage Lesions: Outcome after a Follow-Up of Minimum 2 Years. Cartilage 2021, 13, 1280S-1290S. [CrossRef]

- Tradati, D.; De Luca, P.; Maione, A.; Uboldi, F.M.; Volpi, P.; de Girolamo, L.; Berruto, M. AMIC-Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis Technique in Patellar Cartilage Defects Treatment: A Retrospective Study with a Mid-Term Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1184. [CrossRef]

- Thorey, F.; Malahias, M.-A.; Giotis, D. Sustained Benefit of Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis for Hip Cartilage Repair in a Recreational Athletic Population. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. Off. J. ESSKA 2020, 28, 2309–2315. [CrossRef]

- Salonius, E.; Meller, A.; Paatela, T.; Vasara, A.; Puhakka, J.; Hannula, M.; Haaparanta, A.-M.; Kiviranta, I.; Muhonen, V. Cartilage Repair Capacity within a Single Full-Thickness Chondral Defect in a Porcine Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis Model Is Affected by the Location within the Defect. Cartilage 2021, 13, 744S-754S. [CrossRef]

- Bąkowski, P.; Grzywacz, K.; Prusińska, A.; Ciemniewska-Gorzela, K.; Gille, J.; Piontek, T. Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC) for Focal Chondral Lesions of the Knee: A 2-Year Follow-Up of Clinical, Proprioceptive, and Isokinetic Evaluation. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 277. [CrossRef]

- De Lucas Villarrubia, J.C.; Méndez Alonso, M.Á.; Sanz Pérez, M.I.; Trell Lesmes, F.; Panadero Tapia, A. Acellular Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis Technique Improves the Results of Chondral Lesions Associated With Femoroacetabular Impingement. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 2022, 38, 1166–1178. [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, P.; Laute, V.; Zinser, W.; John, T.; Becher, C.; Diehl, P.; Kolombe, T.; Fay, J.; Siebold, R.; Fickert, S. Safety and Efficacy of Matrix-Associated Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation with Spheroid Technology Is Independent of Spheroid Dose after 4 Years. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. Off. J. ESSKA 2020, 28, 1130–1143. [CrossRef]

- Eichinger, M.; Henninger, B.; Petry, B.; Schuster, P.; Herbst, E.; Wagner, M.; Rosenberger, R.; Mayr, R. Treatment of Cartilage Defects in the Patellofemoral Joint with Matrix-Associated Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation Effectively Improves Pain, Function, and Radiological Outcomes after 5-7 Years. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.-H.; Lee, J.; Park, J.-Y. Costal Chondrocyte-Derived Pellet-Type Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation Versus Microfracture for the Treatment of Articular Cartilage Defects: A 5-Year Follow-up of a Prospective Randomized Trial. Am. J. Sports Med. 2024, 3635465231222797. [CrossRef]

- Snow, M.; Middleton, L.; Mehta, S.; Roberts, A.; Gray, R.; Richardson, J.; Kuiper, J.H.; ACTIVE Consortium; Smith, A.; White, S.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation Versus Alternative Forms of Surgical Cartilage Management in Patients With a Failed Primary Treatment for Chondral or Osteochondral Defects in the Knee. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 367–378. [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, K.; Yamada, S.; Nejima, S.; Sotozawa, M.; Inaba, Y. Minimum 5-Year Outcomes of Osteochondral Autograft Transplantation with a Concomitant High Tibial Osteotomy for Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee with a Large Lesion. Cartilage 2022, 13, 19476035221126341. [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, D.; Muntean, I.; Simos, C.; Sabido-Vera, R. Prospective Observational Study of a Non-Arthroscopic Autologous Cartilage Micrografting Technology for Knee Osteoarthritis. Bioeng. Basel Switz. 2023, 10, 1294. [CrossRef]

- Trofa, D.P.; Hong, I.S.; Lopez, C.D.; Rao, A.J.; Yu, Z.; Odum, S.M.; Moorman, C.T.; Piasecki, D.P.; Fleischli, J.E.; Saltzman, B.M. Isolated Osteochondral Autograft Versus Allograft Transplantation for the Treatment of Symptomatic Cartilage Lesions of the Knee: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 812–824. [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.; Lee, M.S.; Pettinelli, N.; Norman, M.; Park, N.; Gillinov, S.M.; Zhu, J.; Gagné, J.; Lee, A.Y.; Mahatme, R.J.; et al. Osteochondral Allograft or Autograft Transplantation of the Femoral Head Leads to Improvement in Outcomes But Variable Survivorship: A Systematic Review. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 2024, S0749-8063(24)00128-2. [CrossRef]

- Takei, Y.; Morioka, M.; Yamashita, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Shima, N.; Tsumaki, N. Quality Assessment Tests for Tumorigenicity of Human iPS Cell-Derived Cartilage. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12794. [CrossRef]

- Tam, W.L.; Freitas Mendes, L.; Chen, X.; Lesage, R.; Van Hoven, I.; Leysen, E.; Kerckhofs, G.; Bosmans, K.; Chai, Y.C.; Yamashita, A.; et al. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cartilaginous Organoids Promote Scaffold-Free Healing of Critical Size Long Bone Defects. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 513. [CrossRef]

- Hamahashi, K.; Toyoda, E.; Ishihara, M.; Mitani, G.; Takagaki, T.; Kaneshiro, N.; Maehara, M.; Takahashi, T.; Okada, E.; Watanabe, A.; et al. Polydactyly-Derived Allogeneic Chondrocyte Cell-Sheet Transplantation with High Tibial Osteotomy as Regenerative Therapy for Knee Osteoarthritis. NPJ Regen. Med. 2022, 7, 71. [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Yamashita, A.; Morioka, M.; Horike, N.; Takei, Y.; Koyamatsu, S.; Okita, K.; Matsuda, S.; Tsumaki, N. Engraftment of Allogeneic iPS Cell-Derived Cartilage Organoid in a Primate Model of Articular Cartilage Defect. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 804. [CrossRef]

- Eremeev, A.; Pikina, A.; Ruchko, Y.; Bogomazova, A. Clinical Potential of Cellular Material Sources in the Generation of iPSC-Based Products for the Regeneration of Articular Cartilage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14408. [CrossRef]

- Mologne, T.S.; Bugbee, W.D.; Kaushal, S.; Locke, C.S.; Goulet, R.W.; Casden, M.; Grant, J.A. Osteochondral Allografts for Large Oval Defects of the Medial Femoral Condyle: A Comparison of Single Lateral Versus Medial Femoral Condyle Oval Grafts Versus 2 Overlapping Circular Grafts. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 379–388. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Huang, L.; Song, W.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, P.; Wei, X.; et al. Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes After Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation for Treating Articular Cartilage Defects: Systematic Review and Single-Arm Meta-Analysis of Studies From 2001 to 2020. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2023, 11, 23259671231199418. [CrossRef]

- Nuelle, C.W.; Gelber, P.E.; Waterman, B.R. Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation in the Knee. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 2024, 40, 663–665. [CrossRef]

- Garza, J.R.; Campbell, R.E.; Tjoumakaris, F.P.; Freedman, K.B.; Miller, L.S.; Santa Maria, D.; Tucker, B.S. Clinical Efficacy of Intra-Articular Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Double-Blinded Prospective Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Sports Med. 2020, 48, 588–598. [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, E.D.; Cui, X.; Murphy, C.A.; Lim, K.S.; Hooper, G.J.; McIlwraith, C.W.; Woodfield, T.B.F. Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Cartilage Regeneration: A Review of in Vitro Evaluation, Clinical Experience, and Translational Opportunities. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2021, 10, 1500–1515. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Hu, C.-C.; Wu, C.-T.; Wu, H.-T.H.; Chang, C.-S.; Hung, Y.-P.; Tsai, C.-C.; Chang, Y. Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis with Intra-Articular Injection of Allogeneic Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) ELIXCYTE®: A Phase I/II, Randomized, Active-Control, Single-Blind, Multiple-Center Clinical Trial. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 562. [CrossRef]

- Saris, T.F.F.; de Windt, T.S.; Kester, E.C.; Vonk, L.A.; Custers, R.J.H.; Saris, D.B.F. Five-Year Outcome of 1-Stage Cell-Based Cartilage Repair Using Recycled Autologous Chondrons and Allogenic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A First-in-Human Clinical Trial. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 941–947. [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, I.; Katano, H.; Mizuno, M.; Koga, H.; Masumoto, J.; Tomita, M.; Ozeki, N. Alterations in Cartilage Quantification before and after Injections of Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Osteoarthritic Knees. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13832. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, D. de C.; Araújo, L.T. de; Santos, G.C.; Damasceno, P.K.F.; Vieira, J.L.; Santos, R.R.D.; Barbosa, J.D.V.; Soares, M.B.P. Clinical Trials with Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapies for Osteoarthritis: Challenges in the Regeneration of Articular Cartilage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9939. [CrossRef]

- Razak, H.R.B.A.; Corona, K.; Totlis, T.; Chan, L.Y.T.; Salreta, J.F.; Sleiman, O.; Vasso, M.; Baums, M.H. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Implantation Provides Short-Term Clinical Improvement and Satisfactory Cartilage Restoration in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis but the Evidence Is Limited: A Systematic Review Performed by the Early-Osteoarthritis Group of ESSKA-European Knee Associates Section. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. Off. J. ESSKA 2023, 31, 5306–5318. [CrossRef]

- Langer, R.; Vacanti, J.P. Tissue Engineering. Science 1993, 260, 920–926.

- Huey, D.J.; Hu, J.C.; Athanasiou, K.A. Unlike Bone, Cartilage Regeneration Remains Elusive. Science 2012, 338, 917–921. [CrossRef]

- Brittberg, M.; Lindahl, A.; Nilsson, A.; Ohlsson, C.; Isaksson, O.; Peterson, L. Treatment of Deep Cartilage Defects in the Knee with Autologous Chondrocyte Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 889–895. [CrossRef]

- Brittberg, M.; Peterson, L.; Sjögren-Jansson, E.; Tallheden, T.; Lindahl, A. Articular Cartilage Engineering with Autologous Chondrocyte Transplantation. A Review of Recent Developments. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003, 85-A Suppl 3, 109–115. [CrossRef]

- Steinwachs, M.; Kreuz, P.C. Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation in Chondral Defects of the Knee with a Type I/III Collagen Membrane: A Prospective Study with a 3-Year Follow-Up. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 2007, 23, 381–387. [CrossRef]

- Tohyama, H.; Yasuda, K.; Minami, A.; Majima, T.; Iwasaki, N.; Muneta, T.; Sekiya, I.; Yagishita, K.; Takahashi, S.; Kurokouchi, K.; et al. Atelocollagen-Associated Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation for the Repair of Chondral Defects of the Knee: A Prospective Multicenter Clinical Trial in Japan. J. Orthop. Sci. Off. J. Jpn. Orthop. Assoc. 2009, 14, 579–588. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Menage, J.; Sandell, L.J.; Evans, E.H.; Richardson, J.B. Immunohistochemical Study of Collagen Types I and II and Procollagen IIA in Human Cartilage Repair Tissue Following Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation. The Knee 2009, 16, 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Benya, P.D.; Padilla, S.R.; Nimni, M.E. Independent Regulation of Collagen Types by Chondrocytes during the Loss of Differentiated Function in Culture. Cell 1978, 15, 1313–1321. [CrossRef]

- Tan Timur, U.; Caron, M.; van den Akker, G.; van der Windt, A.; Visser, J.; van Rhijn, L.; Weinans, H.; Welting, T.; Emans, P.; Jahr, H. Increased TGF-β and BMP Levels and Improved Chondrocyte-Specific Marker Expression In Vitro under Cartilage-Specific Physiological Osmolarity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 795. [CrossRef]

- Knudson, C.B.; Knudson, W. Cartilage Proteoglycans. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 12, 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Varki, A. Glycan-Based Interactions Involving Vertebrate Sialic-Acid-Recognizing Proteins. Nature 2007, 446, 1023–1029. [CrossRef]

- Malagolini, N.; Chiricolo, M.; Marini, M.; Dall’Olio, F. Exposure of Alpha2,6-Sialylated Lactosaminic Chains Marks Apoptotic and Necrotic Death in Different Cell Types. Glycobiology 2009, 19, 172–181. [CrossRef]

- Toegel, S.; Pabst, M.; Wu, S.Q.; Grass, J.; Goldring, M.B.; Chiari, C.; Kolb, A.; Altmann, F.; Viernstein, H.; Unger, F.M. Phenotype-Related Differential Alpha-2,6- or Alpha-2,3-Sialylation of Glycoprotein N-Glycans in Human Chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. OARS Osteoarthr. Res. Soc. 2010, 18, 240–248. [CrossRef]

- Kahrizi, M.S.; Mousavi, E.; Khosravi, A.; Rahnama, S.; Salehi, A.; Nasrabadi, N.; Ebrahimzadeh, F.; Jamali, S. Recent Advances in Pre-Conditioned Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell (MSCs) Therapy in Organ Failure; a Comprehensive Review of Preclinical Studies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 155. [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.U.; Mehta, A.; Vũ, T.T.; Yeo, G.C. Cellular Modifications and Biomaterial Design to Improve Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 4752–4773. [CrossRef]

- Giannasi, C.; Della Morte, E.; Cadelano, F.; Valenza, A.; Casati, S.; Dei Cas, M.; Niada, S.; Brini, A.T. Boosting the Therapeutic Potential of Cell Secretome against Osteoarthritis: Comparison of Cytokine-Based Priming Strategies. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2023, 170, 115970. [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, T.; Homan, K.; Fukushima, A.; Ukeba, D.; Iwasaki, N.; Sudo, H. A Review: Methodologies to Promote the Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Regeneration of Intervertebral Disc Cells Following Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Cells 2023, 12, 2161. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-Y.; Zhai, Y.; Li, C.T.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Chen, H.; Tse, H.-F.; Lian, Q. Translating Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Their Exosome Research into GMP Compliant Advanced Therapy Products: Promises, Problems and Prospects. Med. Res. Rev. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Garza, L.E.; Barrera-Barrera, S.A.; Barrera-Saldaña, H.A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapies Approved by Regulatory Agencies around the World. Pharm. Basel Switz. 2023, 16, 1334. [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Zhu, H.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes as a Promising Cell-Free Therapy for Knee Osteoarthritis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1309946. [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, A.; Hirvonen, T.; Salo, H.; Impola, U.; Olonen, A.; Laitinen, A.; Tiitinen, S.; Natunen, S.; Aitio, O.; Miller-Podraza, H.; et al. Glycomics of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Can Be Used to Evaluate Their Cellular Differentiation Stage. Glycoconj. J. 2009, 26, 367–384. [CrossRef]

- Tateno, H.; Saito, S.; Hiemori, K.; Kiyoi, K.; Hasehira, K.; Toyoda, M.; Onuma, Y.; Ito, Y.; Akutsu, H.; Hirabayashi, J. A2-6 Sialylation Is a Marker of the Differentiation Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Glycobiology 2016, 26, 1328–1337. [CrossRef]

- Hasehira, K.; Hirabayashi, J.; Tateno, H. Structural and Quantitative Evidence of A2-6-Sialylated N-Glycans as Markers of the Differentiation Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Glycoconj. J. 2017, 34, 797–806. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-S.; Seo, S.Y.; Jeong, E.-J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Koh, Y.-G.; Kim, Y.I.; Choo, Y.-K. Ganglioside GM3 Up-Regulate Chondrogenic Differentiation by Transform Growth Factor Receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Hanamatsu, H.; Homan, K.; Onodera, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Furukawa, J.-I.; Hontani, K.; Tian, Y.; Baba, R.; Iwasaki, N. Alterations of Glycosphingolipid Glycans and Chondrogenic Markers during Differentiation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells into Chondrocytes. Biomolecules 2020, 10, E1622. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [CrossRef]

- Okita, K.; Matsumura, Y.; Sato, Y.; Okada, A.; Morizane, A.; Okamoto, S.; Hong, H.; Nakagawa, M.; Tanabe, K.; Tezuka, K.; et al. A More Efficient Method to Generate Integration-Free Human iPS Cells. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 409–412. [CrossRef]

- Nikolouli, E.; Reichstein, J.; Hansen, G.; Lachmann, N. In Vitro Systems to Study Inborn Errors of Immunity Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1024935. [CrossRef]

- Şen, B.; Balcı-Peynircioğlu, B. Cellular Models in Autoinflammatory Disease Research. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2024, 13, e1481. [CrossRef]

- de Rham, C.; Villard, J. Potential and Limitation of HLA-Based Banking of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells for Cell Therapy. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 518135. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Preynat-Seauve, O.; Tiercy, J.-M.; Krause, K.-H.; Villard, J. Haplotype-Based Banking of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells for Transplantation: Potential and Limitations. Stem Cells Dev. 2012, 21, 2364–2373. [CrossRef]

- Morishima, Y.; Azuma, F.; Kashiwase, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Orihara, T.; Yabe, H.; Kato, S.; Kato, K.; Kai, S.; Mori, T.; et al. Risk of HLA Homozygous Cord Blood Transplantation: Implications for Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Banking and Transplantation. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 173–179. [CrossRef]

- Umekage, M.; Sato, Y.; Takasu, N. Overview: An iPS Cell Stock at CiRA. Inflamm. Regen. 2019, 39, 17. [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, S. Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cell Therapy-Promise and Challenges. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 523–531. [CrossRef]

- Hontani, K.; Onodera, T.; Terashima, M.; Momma, D.; Matsuoka, M.; Baba, R.; Joutoku, Z.; Matsubara, S.; Homan, K.; Hishimura, R.; et al. Chondrogenic Differentiation of Mouse Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Using the Three-Dimensional Culture with Ultra-Purified Alginate Gel. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 1086–1093. [CrossRef]

- Gropp, M.; Shilo, V.; Vainer, G.; Gov, M.; Gil, Y.; Khaner, H.; Matzrafi, L.; Idelson, M.; Kopolovic, J.; Zak, N.B.; et al. Standardization of the Teratoma Assay for Analysis of Pluripotency of Human ES Cells and Biosafety of Their Differentiated Progeny. PloS One 2012, 7, e45532. [CrossRef]

- Kawamata, S.; Kanemura, H.; Sakai, N.; Takahashi, M.; Go, M.J. Design of a Tumorigenicity Test for Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Derived Cell Products. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 159–171. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S.; Nakao, H.; Kawabe, K.; Nonaka, M.; Toyoda, H.; Takishima, Y.; Kawabata, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Furue, M.K.; Taki, T.; et al. A Cytotoxic Antibody Recognizing Lacto-N-Fucopentaose I (LNFP I) on Human Induced Pluripotent Stem (hiPS) Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 20071–20085. [CrossRef]

- Hanamatsu, H.; Nishikaze, T.; Miura, N.; Piao, J.; Okada, K.; Sekiya, S.; Iwamoto, S.; Sakamoto, N.; Tanaka, K.; Furukawa, J.-I. Sialic Acid Linkage Specific Derivatization of Glycosphingolipid Glycans by Ring-Opening Aminolysis of Lactones. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 13193–13199. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Hanamatsu, H.; Xu, L.; Onodera, T.; Furukawa, J.-I.; Homan, K.; Baba, R.; Kawasaki, T.; Iwasaki, N. Evaluation of Residual Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells in Human Chondrocytes by Cell Type-Specific Glycosphingolipid Glycome Analysis Based on the Aminolysis-SALSA Technique. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, E231. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Hanamatsu, H.; Onodera, T.; Furukawa, J.-I.; Xu, L.; Homan, K.; Baba, R.; Kawasaki, T.; Iwasaki, N. Establishment of the Removal Method of Undifferentiated Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Coexisting with Chondrocytes Using R-17F Antibody. Regen. Med. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Clinical practice | Cell source | Lesion size (cm2) / OA grade | Performances | References |

| Microfracture | Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) | 2.0-4.0 | Microfracture is most likely to be successful for small femoral condylar defects | [88,89,90,91,92] |

| Autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) | MSC | 1.3-5.3 | Effective procedure for the treatment of mid-sized cartilage defects. Low failure rate with satisfactory clinical outcome | [88,89,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] |

| Autologous chondrocyte implantation | Chondrocyte | 2.0-10.0 | Superior structural integration with native cartilage tissue compared to microfracture and AMIC, but a two-stage treatment burden exists | [89,100,101,102,103] |

| Osteochondral autograft transplantation | Chondrocyte | 0.1-20.0 / OA grade Ⅰ-Ⅲ | Osteochondral autograft transfer system and mosaicplasty appear to be an alternative for the treatment of medium-sized focal chondral and osteochondral defects of the weight-bearing surfaces of the knee. Chondrocyte sheet and auricular cartilage micrograft for treatment of early-stage OA has been tried | [104,105,106,107] |

| Allogenic transplantation | Chondrocyte, iPSC | 2.2-4.4 / OA gradeⅡ-Ⅳ | Osteoarticular allograft transplantation was used to treat high-grade cartilage defects or arthritis. iPSC-derived cartilages are used in preclinical studies that are in the middle to late stages when clinical trials are within range | [108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115] |

| Intra-articular injection with stem cell | adipose-derived stem cell, MSC | OA grade Ⅱ-Ⅳ | Lower degenerative grades improve outcomes but are less effective for end-stage OA. The results of intra-articular administration of stem cells are better with BMSC. | [116,117,118,119,120,121,122] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).