Submitted:

04 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

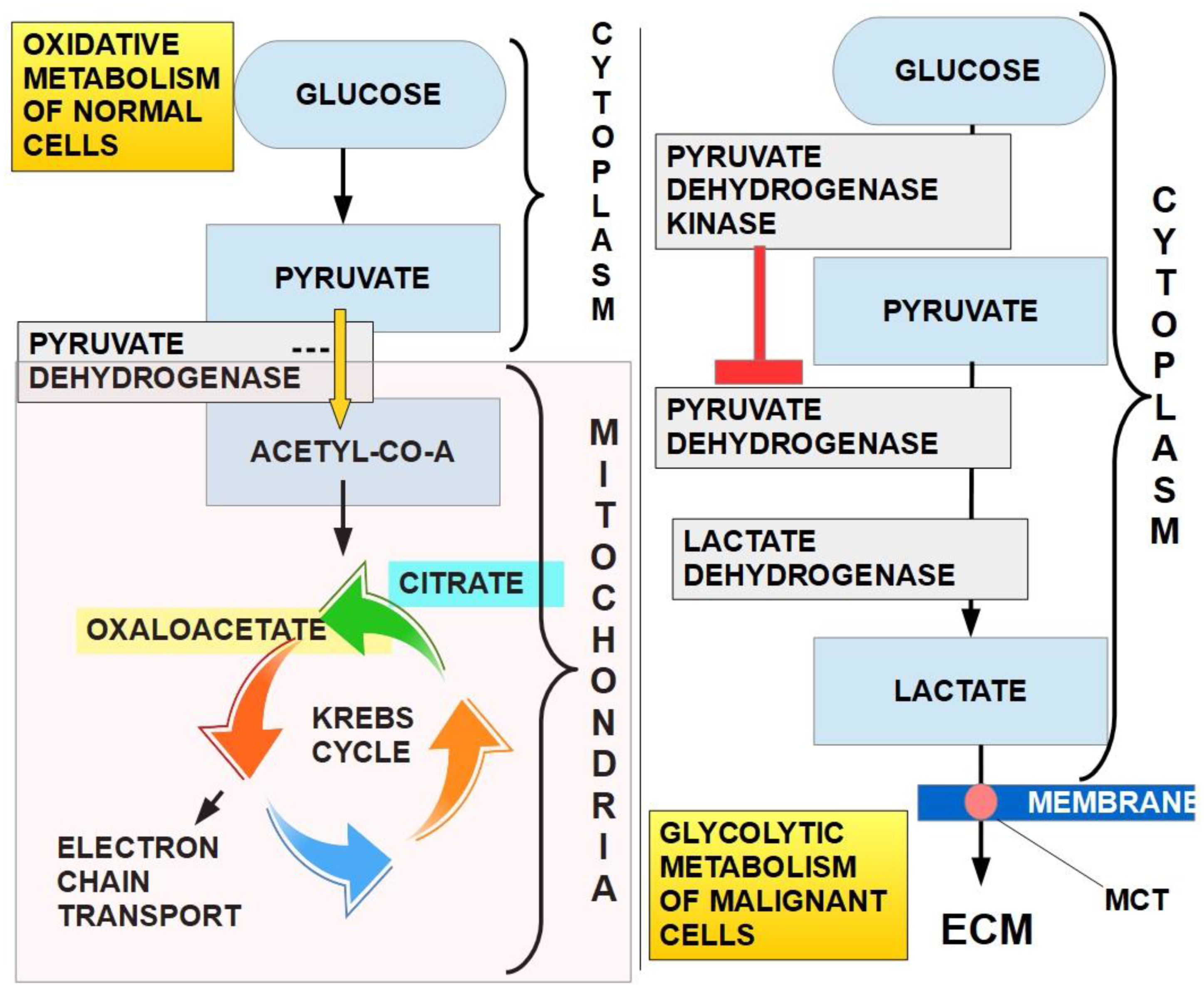

1.1. Lactate and Cancer

- 1)

- Malignant cells’ increased glucose uptake and metabolism.

- 2)

- Glycolytic metabolism which occurs even in the presence of oxygen (Warburg effect).

- 3)

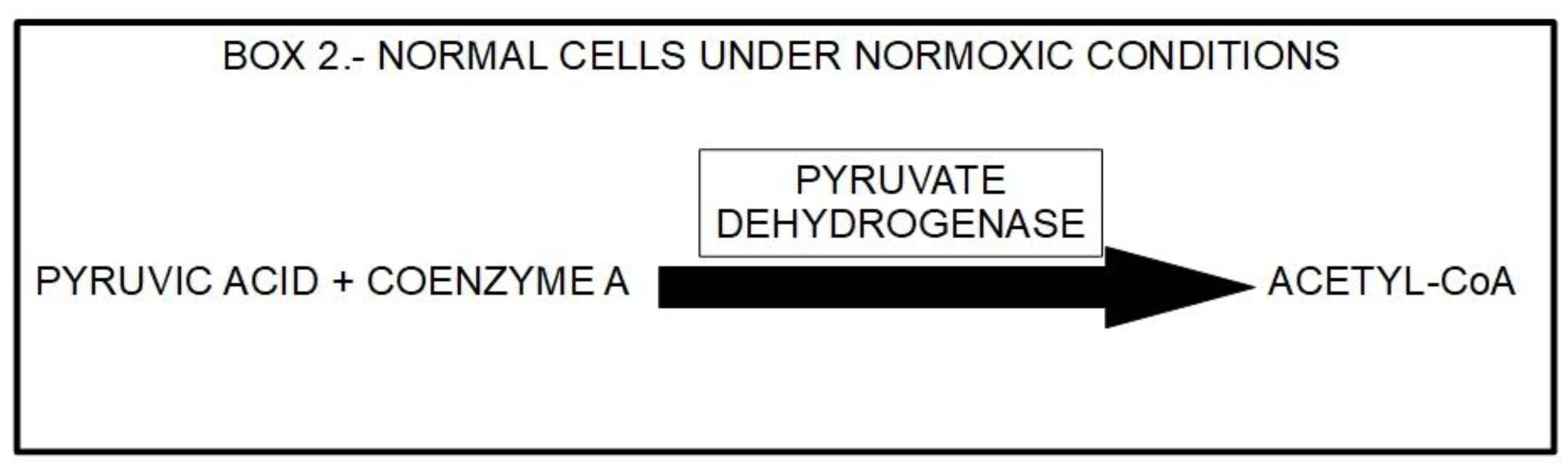

- Decreased activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex.

- 4)

- Increased activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDK)

- 5)

- Increased expression and activity of the lactate extrusion proteins MCT1 and MCT4.

- 6)

- Increased expression and activity of the glycolytic enzymes.

- 1)

- 2)

- 3)

- 4)

- 5)

- 6)

- 7)

- Lactate activates HIF-1α in non-glycolytic cells (but not in glycolytic cells) which in turn further stimulates glycolysis and angiogenesis [50].

- 8)

- 9)

- Lactate has a positive correlation with radioresistance [53].

- 10)

- It increases hyaluronan production involved in migration and growth [54].

- 11)

- Lactate modulates the tumor microenvironment [55].

- 12)

- 13)

- Lactylation has also been found to be an important mechanism of post-translational modification of proteins associated with poor prognosis in cancer progression [59].

- 14)

- Lactate is an important source of energy for oxidative lactophagic cells [60].

- 15)

- The pyruvate to lactate conversion by lactate dehydrogenase regenerates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) in the cytoplasm [61] and NAD+ is an important metabolite for redox processes.

1.2. Dichloroacetate (DCA)

1.2.1. Therapeutic History of Dichloroacetate

1.2.2. DCA Enters the Oncology Terrain

- 1)

- To summarize and review published data on DCA use in cancer.

- 2)

- To establish an impartial view of benefits/harm that DCA may cause.

- 3)

- To determine the role that DCA should or should not have in cancer treatment.

- 4)

- To evaluate the opportunity and convenience of further research.

- 5)

- To find out if DCA deserves to be rescued from the hands of unqualified people and introduced as a complementary treatment for cancer.

1.2.3. Chemistry and Pharmacology of DCA

- 1)

- doubts about the possibility of translating findings in other animals to humans.

- 2)

- the importance of the inter-species differences of the clearance mechanism.

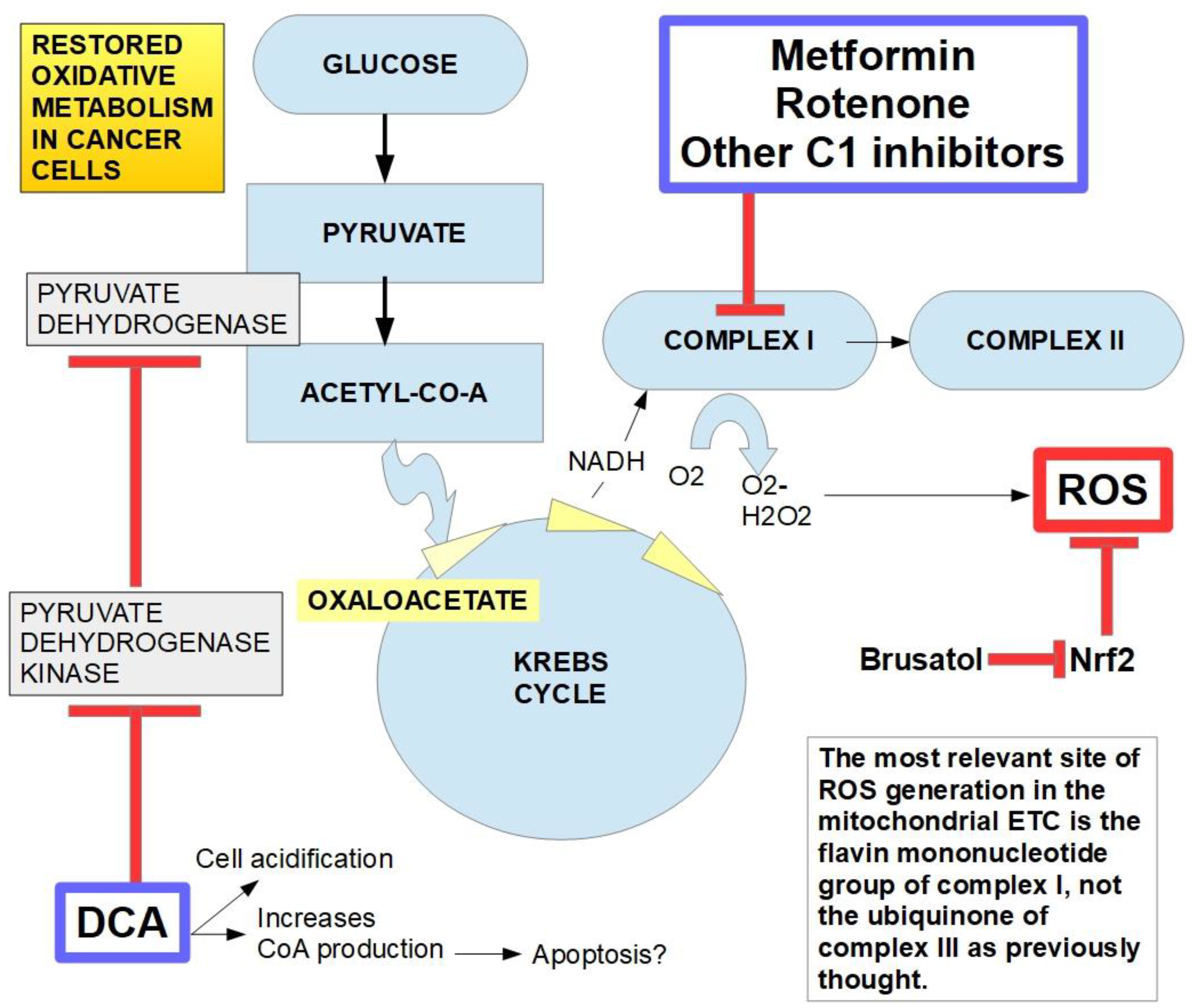

1.2.4. Mechanism of Action

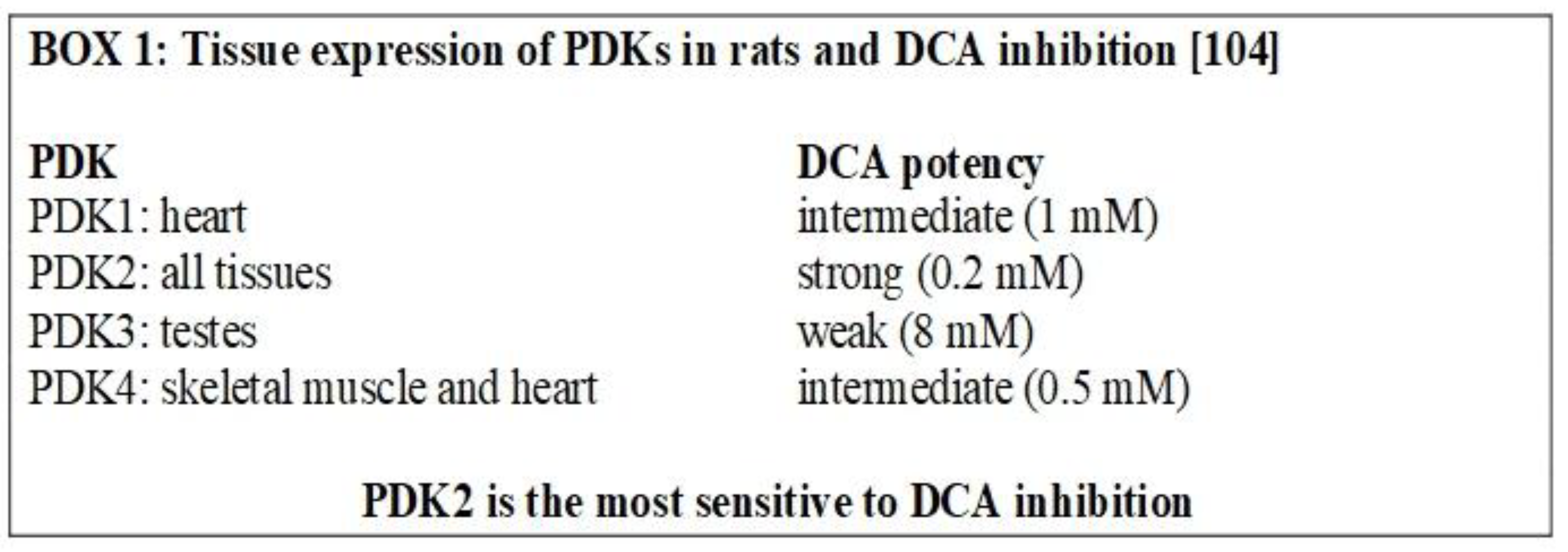

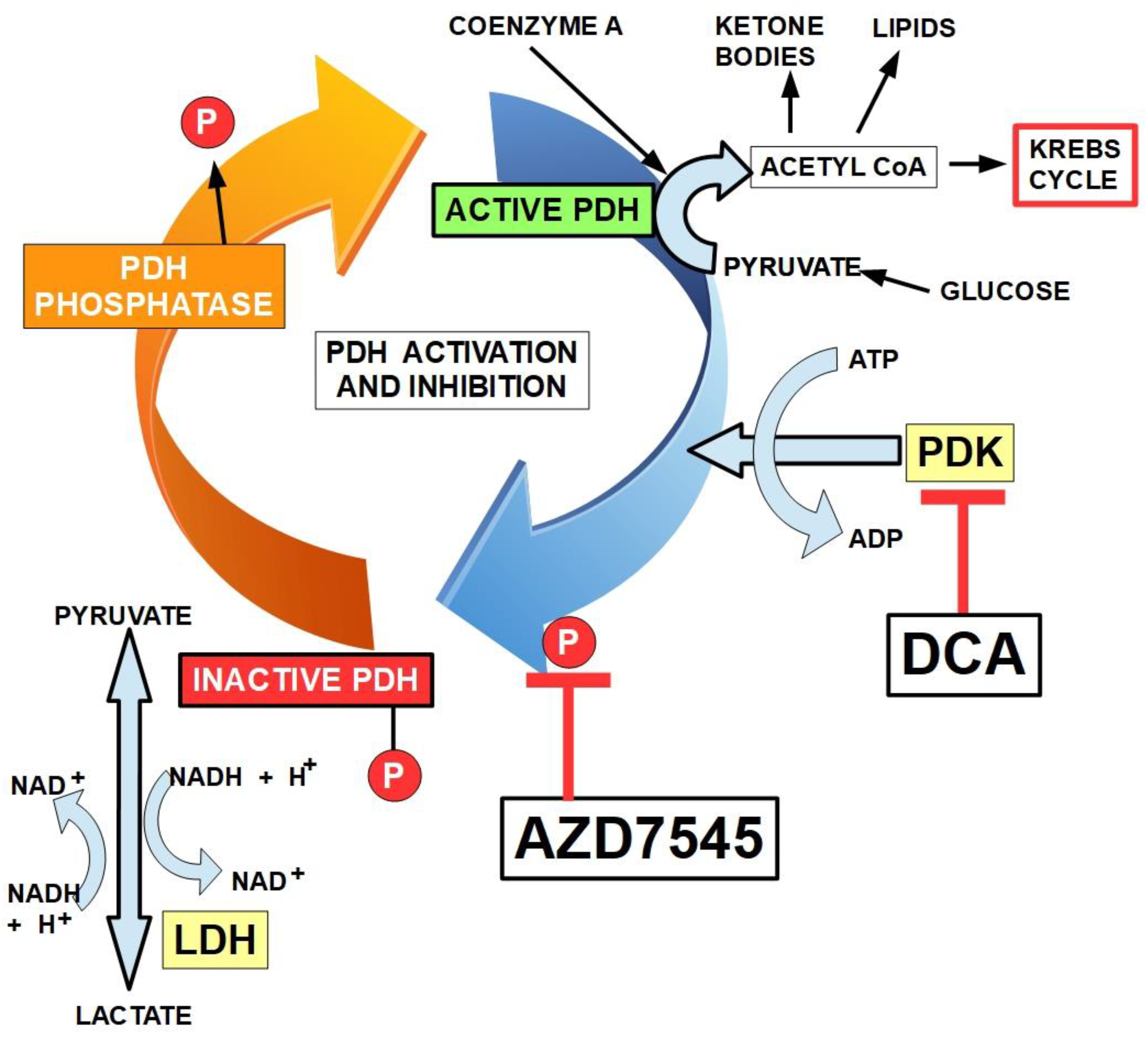

- a)

- an inhibitory system represented by the four isoforms of PDK and

- b)

- a "disinhibitory" system represented by the two PDH phosphatases (see below)

2.

2.1. PDH Complex

2.2. PDK Family of Enzymes

2.3. Inhibition of PDKs

2.4. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Phosphatases (PDP)

2.5. Mechanism of Action of DCA

Lactylation and DCA

- 1)

- 2)

- can external lactate that enters the cell by MCT1 activity be integrated into lactylation, or is it required that it be converted into pyruvate? If external lactate (from the lactate shuttle) participates significantly in lactylation, DCA would be ineffective in preventing it. Thus far, there is only evidence of lactylation that originates from lactate metabolically produced by the cell [149]. However, for now there is no evidence that excludes lactate imported into cells from participating in lactylation.

3. Experimental Evidence on DCA Activity in Cancer

3.1. Breast Cancer

3.2. Prostate Cancer

- 1)

- in prostate cancer cells Krebs cycle oxaloacetic acid is not regenerated but produced from imported aspartate [175].

- 2)

- prostate cancer is initially not a glycolytic type of tumor, rather it adopts a lipogenic phenotype until some critical time later, during its progression when it becomes glycolytic. This last peculiarity in metabolism contrasts with breast cancer where glycolysis is the predominant metabolic feature from very early stages. This also explains the reasons why fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission scans are of little help at initial stages of prostate cancer [176] and become useful in the advanced stages [177].

3.3. Colon Cancer

3.4. Melanoma

3.5. Glioblastoma

3.6. Hematopoietic Tumors

3.6.1. Myeloma

3.6.2. Lymphoma

3.6.3. Leukemia

3.7. Ovarian, Cervical and Uterine Cancer

3.8. Lung Cancer

3.8.1. Non Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

3.8.2. Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC)

3.9. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC)

3.10. Renal Tumors

3.11. Pancreatic Cancer

3.12. Hepatocarcinoma

3.13. Other Tumors

4. Resistance to DCA

5. DCA and Some Interesting Associations

5.1. DCA and Metformin

5.2. DCA and COX2 Inhibitors

5.3. DCA and Lipoic Acid

5.4. DCA and 2D-Deoxy Glucose (2DG)

5.5. DCA and Bicarbonate

5.6. DCA and Sulindac

5.7. Mitaplatin

5.8. Thiamin

5.9. DCA and Betulinic Acid

5.10. DCA and Rapamycin

5.11. DCA and Vemurafenib

5.12. DCA and Ivermectin

5.13. DCA and TRAIL Liposomes

5.14. DCA and 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU)

5.15. DCA and Chemotherapeutic Drugs in General

5.16. DCA and Salinomycin

5.17. DCA and Propranolol

5.18. DCA and All-Transretinoic Acid (ATRA)

5.19. DCA and Radiotherapy

5.20. DCA and Omeprazol

5.21. DCA and 2-Methoxiestradiol

5.22. DCA and Sirtinol

5.23. DCA and EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

6. DCA and T Cells

7. Side Effects, Toxicity and Doses

8. DCA Dosage

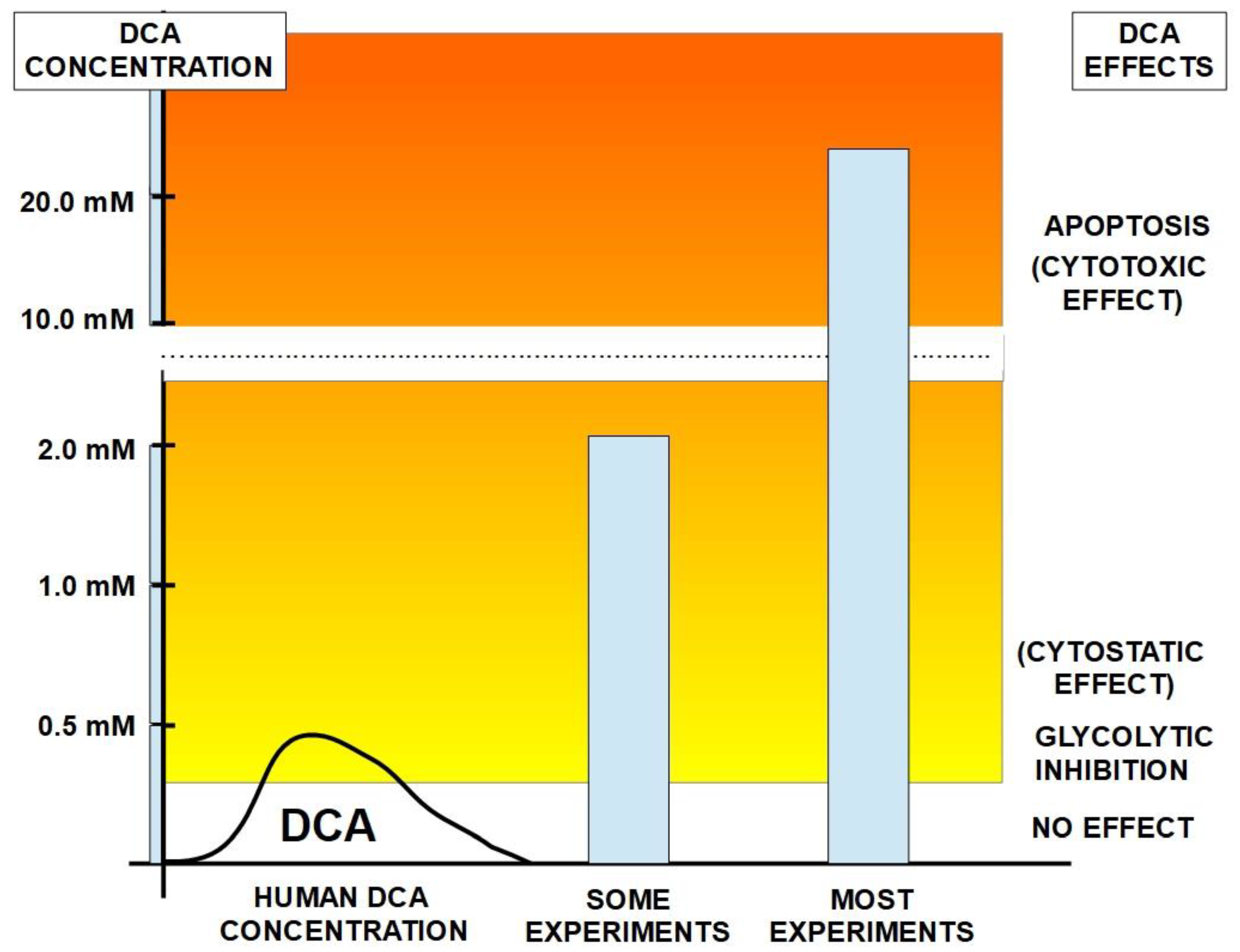

9. DCA Concentrations in Humans and Animals: A Key Issue

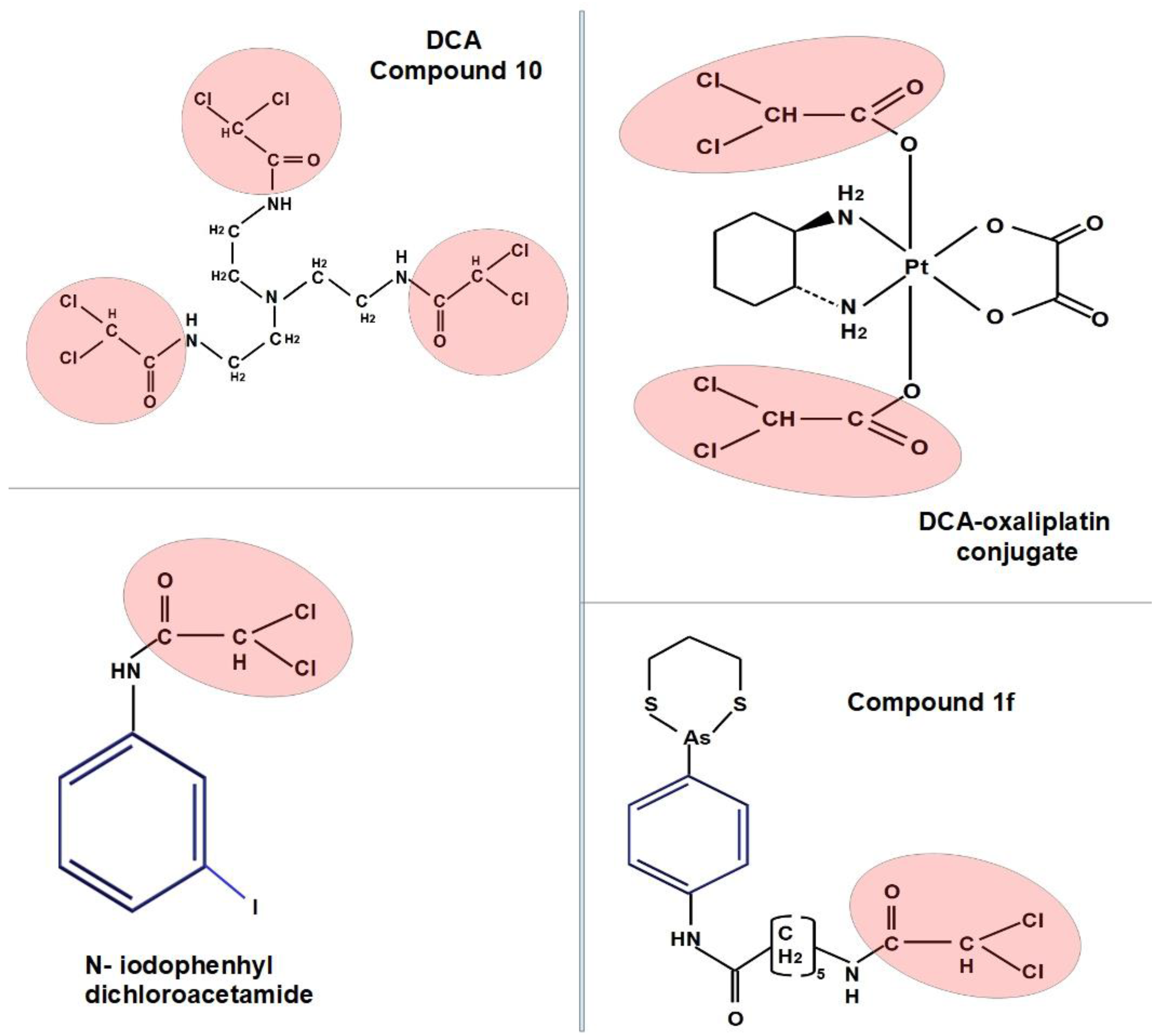

10. DCA Derivatives

11. Clinical Cases

11.1. Clinical Trials

Clinical Trials with Poor Results

12. Negative Results with DCA

13. Discussion

- a)

- cells that survive can switch to another type of metabolism such as mitochondrial oxidative metabolism;

- b)

- there may be a persistence of oxidative cells that are not affected by DCA;

- c)

- DCA is cytostatic rather than cytotoxic, and both require very high concentrations;

- d)

- the tumor is predominantly oxidative.

- 1)

- DCA responders: the glycolytic phenotype is due to up-regulation of PDK.

- 2)

- DCA non responders: the glycolytic phenotype is not dependent on PDK up-regulation.

14. Future Perspectives

15. General Conclusions

16. Main Conclusion

17. Declarations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warburg, O.; Wind, F.; Negelein, E. THE METABOLISM OF TUMORS IN THE BODY. The Journal of General Physiology 1927, 8, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.P.; Sabatini, D.M. Cancer cell metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell 2008, 134, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Thompson, C.B. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell metabolism 2016, 23, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carracedo, A.; Cantley, L.C.; Pandolfi, P.P. Cancer metabolism: fatty acid oxidation in the limelight. Nature reviews Cancer 2013, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danial, N.N.; Gramm, C.F.; Scorrano, L.; Zhang, C.Y.; Krauss, S.; Ranger, A.M.; Datta, S.R.; Greenberg, M.E.; Licklider, L.J.; Lowell, B.B.; Gygi, S.P. BAD and glucokinase reside in a mitochondrial complex that integrates glycolysis and apoptosis. Nature 2003, 424, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomiyama, A.; Serizawa, S.; Tachibana, K.; Sakurada, K.; Samejima, H.; Kuchino, Y.; Kitanaka, C. Critical role for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the activation of tumor suppressors Bax and Bak. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2006, 98, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, R.; Moraes, C.T. Lack of oxidative phosphorylation and low mitochondrial membrane potential decrease susceptibility to apoptosis and do not modulate the protective effect of Bcl-xL in osteosarcoma cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 7087–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Chang, I.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, S.W.; Park, S.H.; Singh, K.; Lee, M.S. Resistance of mitochondrial DNA-depleted cells against cell death: role of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004, 279, 7512–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.H.; Vander Heiden, M.G.; Kron, S.J.; Thompson, C.B. Role of oxidative phosphorylation in Bax toxicity. Molecular and cellular biology 2000, 20, 3590–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Lin, Z.; Ertel, A.; Flomenberg, N.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Birbe, R.C.; Howell, A.; Pavlides, S.; Gandara, R.; Pestell, R.G.; Sotgia, F.; Philp, N.J.; Lisanti, M.P. Evidence for a stromal-epithelial "lactate shuttle" in human tumors: MCT4 is a marker of oxidative stress in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 1772–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.I. Energy metabolism of cancer: Glycolysis versus oxidative phosphorylation. Oncology letters 2012, 4, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, T.; Schuster, S.; Bonhoeffer, S. Cooperation and competition in the evolution of ATP-producing pathways. Science 2001, 292, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaupel, P.; Multhoff, G. Revisiting the Warburg effect: Historical dogma versus current understanding. The Journal of physiology 2021, 599, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppenol, W.H.; Bounds, P.L.; Dang, C.V. Otto Warburg's contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer 2011, 11, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, B.A.; Chimenti, M.; Jacobson, M.P.; Barber, D.L. Dysregulated pH: a perfect storm for cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, L.; T Supuran, C.; O Alfarouk, K. The Warburg effect and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents) 2017, 17, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarouk, K.O.; Verduzco, D.; Rauch, C.; Muddathir, A.K.; Adil, H.B.; Elhassan, G.O.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Orozco, J.D.; Cardone, R.A.; Reshkin, S.J.; Harguindey, S. Glycolysis, tumor metabolism, cancer growth and dissemination. A new pH-based etiopathogenic perspective and therapeutic approach to an old cancer question. Oncoscience 2014, 1, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harguindey, S.; Reshkin, S.J. The new pH-centric anticancer paradigm in Oncology and Medicine"; SCB, 2017. In Seminars in cancer biology 2017 Apr (Vol. 43, pp. 1–4). [CrossRef]

- Walenta, S.; Mueller-Klieser, W.F. Lactate: mirror and motor of tumor malignancy. InSeminars in radiation oncology 2004 Jul 1 (Vol. 14, No. 3, 267-274). WB Saunders. [CrossRef]

- Newell, K.; Franchi, A.; Pouyssegur, J.; Tannock, I. Studies with glycolysis-deficient cells suggest that production of lactic acid is not the only cause of tumor acidity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, M.; Hasuda, K.; Stamato, T.; Tannock, I.F. The contribution of lactic acid to acidification of tumours: studies of variant cells lacking lactate dehydrogenase. British journal of cancer 1998, 77, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.C.; Meredith, D.; Fox, J.E.; Manoharan, C.; Davies, A.J.; Halestrap, A.P. Basigin (CD147) Is the Target for Organomercurial Inhibition of Monocarboxylate Transporter Isoforms 1 and 4 THE ANCILLARY PROTEIN FOR THE INSENSITIVE MCT2 IS EMBIGIN (gp70). Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 27213–27221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polański, R.; Hodgkinson, C.L.; Fusi, A.; Nonaka, D.; Priest, L.; Kelly, P.; Trapani, F.; Bishop, P.W.; White, A.; Critchlow, S.E.; Smith, P.D. Activity of the monocarboxylate transporter 1 inhibitor AZD3965 in small cell lung cancer. Clinical cancer research 2013, 20, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, V.; Binet, I.; Steger, U.; Bundick, R.; Ferguson, D.; Murray, C.; Donald, D.; Wood, K. The specific monocarboxylate transporter (MCT1) inhibitor, AR-C117977, a novel immunosuppressant, prolongs allograft survival in the mouse. Transplantation 2007, 84, 1204–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovens, M.J.; Davies, A.J.; Wilson, M.C.; Murray, C.M.; Halestrap, A.P. AR-C155858 is a potent inhibitor of monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and MCT2 that binds to an intracellular site involving transmembrane helices 7–10. Biochemical Journal 2010, 425, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.M.; Hutchinson, R.; Bantick, J.R.; Belfield, G.P.; Benjamin, A.D.; Brazma, D.; Bundick, R.V.; Cook, I.D.; Craggs, R.I.; Edwards, S.; Evans, L.R. Monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 is a target for immunosuppression. Nature chemical biology 2005, 1, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Otsuka, Y.; Itagaki, S.; Hirano, T.; Iseki, K. Inhibitory effects of statins on human monocarboxylate transporter 4. International journal of pharmaceutics 2006, 317, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.; Antunes, B.; Batista, A.; Pinto-Ribeiro, F.; Baltazar, F.; Afonso, J. In vivo anticancer activity of AZD3965: a systematic review. Molecules 2021, 27, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetze, K.; Walenta, S.; Ksiazkiewicz, M.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Mueller-Klieser, W. Lactate enhances motility of tumor cells and inhibits monocyte migration and cytokine release. International journal of oncology 2011, 39, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, F.; Leukel, P.; Doerfelt, A.; Beier, C.P.; Dettmer, K.; Oefner, P.J.; Kastenberger, M.; Kreutz, M.; Nickl-Jockschat, T.; Bogdahn, U.; Bosserhoff, A.K. Lactate promotes glioma migration by TGF-β2–dependent regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Neuro-oncology 2009, 11, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, T.; Hussien, R.; Oommen, S.; Gohil, K.; Brooks, G.A. Lactate sensitive transcription factor network in L6 cells: activation of MCT1 and mitochondrial biogenesis. The FASEB Journal 2007, 21, 2602–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Zuo, H.; Xiong, H.; Kolar, M.J.; Chu, Q.; Saghatelian, A.; Siegwart, D.J.; Wan, Y. Gpr132 sensing of lactate mediates tumor–macrophage interplay to promote breast cancer metastasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.Y.; Collins, C.C.; Gout, P.W.; Wang, Y. Cancer-generated lactic acid: a regulatory, immunosuppressive metabolite? . The Journal of pathology 2013, 230, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Keskinov, A.A.; Shurin, G.V.; Shurin, M.R. Tumor-derived factors modulating dendritic cell function. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2016, 65, 821–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottfried, E.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Ebner, S.; Mueller-Klieser, W.; Hoves, S.; Andreesen, R.; Mackensen, A.; Kreutz, M. Tumor-derived lactic acid modulates dendritic cell activation and antigen expression. Blood 2006, 107, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig-Kröger, A.; Muniz-Pello, O.; Selgas, R.; Criado, G.; Bajo, M.A.; Sánchez-Tomero, J.A.; Alvarez, V.; del Peso, G.; Sánchez-Mateos, P.; Holmes, C.; Faict, D. Peritoneal dialysis solutions inhibit the differentiation and maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells: effect of lactate and glucose-degradation products. Journal of Leucocyte Biology 2003, 73, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, K.; Hoffmann, P.; Voelkl, S.; Meidenbauer, N.; Ammer, J.; Edinger, M.; Gottfried, E.; Schwarz, S.; Rothe, G.; Hoves, S.; Renner, K.; Timischl, B.; Mackensen, A.; Kunz-Schughart, L.; Andreesen, R.; Krause, S.W.; Kreutz, M:. Inhibitory effect of tumor cell–derived lactic acid on human T cells. Blood 2007, 109, 3812–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constant, J.S.; Feng, J.J.; Zabel, D.D.; Yuan, H.; Suh, D.Y.; Scheuenstuhl, H.; Hunt, T.K.; Hussain, M.Z. Lactate elicits vascular endothelial growth factor from macrophages: a possible alternative to hypoxia. Wound Repair Regen 2000, 8, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milovanova, T.N.; Bhopale, V.M.; Sorokina, E.M.; Moore, J.S.; Hunt, T.K.; Hauer-Jensen, M.; Velazquez, O.C.; Thom, S.R. Lactate stimulates vasculogenic stem cells via the thioredoxin system and engages an autocrine activation loop involving hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 2008, 28, 6248–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, T.K.; Aslam, R.S.; Beckert, S.; et al. Aerobically derived lactate stimulates revascularization and tissue repair via redox mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckert, S.; Farrahi, F.; Aslam, R.S.; et al. Lactate stimulates endothelial cell migration. Wound Repair Regen. [CrossRef]

- Végran, F.; Boidot, R.; Michiels, C.; Sonveaux, P.; Feron, O. Lactate influx through the endothelial cell monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 supports an NF-κB/IL-8 pathway that drives tumor angiogenesis. Cancer research 2011, 71, 2550–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walenta, S.; Salameh, A.; Lyng, H.; Evensen, J.F.; Mitze, M.; Rofstad, E.K.; Mueller-Klieser, W. Correlation of high lactate levels in head and neck tumors with incidence of metastasis. The American journal of pathology 1997, 150, 409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwickert, G.; Walenta, S.; Sundfør, K.; Rofstad, E.K.; Mueller-Klieser, W. Correlation of high lactate levels in human cervical cancer with incidence of metastasis. Cancer research 1995, 55, 4757–4759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonuccelli, G.; Tsirigos, A.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Pavlides, S.; Pestell, R.G.; Chiavarina, B.; Frank, P.G.; Flomenberg, N.; Howell, A.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Sotgia, F. Ketones and lactate “fuel” tumor growth and metastasis: Evidence that epithelial cancer cells use oxidative mitochondrial metabolism. Cell cycle 2010, 9, 3506–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Prisco, M.; Ertel, A.; Tsirigos, A.; Lin, Z.; Pavlides, S.; Wang, C.; Flomenberg, N.; Knudsen, E.S.; Howell, A.; Pestell, R.G. Ketones and lactate increase cancer cell “stemness,” driving recurrence, metastasis and poor clinical outcome in breast cancer: achieving personalized medicine via Metabolo-Genomics. Cell cycle 2011, 10, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shegay, P.V.; Zabolotneva, A.A.; Shatova, O.P.; Shestopalov, A.V.; Kaprin, A.D. Evolutionary view on lactate-dependent mechanisms of maintaining cancer cell stemness and reprimitivization. Cancers 2022, 14, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Saedeleer, C.J.; Copetti, T.; Porporato, P.E.; Verrax, J.; Feron, O.; Sonveaux, P. Lactate activates HIF-1 in oxidative but not in Warburg-phenotype human tumor cells. PloS one 2012, 7, e46571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuvel, D.J.; Sundararaj, K.P.; Nareika, A.; Lopes-Virella, M.F.; Huang, Y. Lactate boosts TLR4 signaling and NF-κB pathway-mediated gene transcription in macrophages via monocarboxylate transporters and MD-2 up-regulation. The Journal of Immunology 2009, 182, 2476–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shime, H.; Yabu, M.; Akazawa, T.; Kodama, K.; Matsumoto, M.; Seya, T.; Inoue, N. Tumor-Secreted Lactic Acid Promotes IL-23/IL-17 Proinflammatory Pathway. J. Immunol 2008, 180, 7175–7183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattler, U.G.; Meyer, S.S.; Quennet, V.; Hoerner, C.; Knoerzer, H.; Fabian, C.; Yaromina, A.; Zips, D.; Walenta, S.; Baumann, M.; Mueller-Klieser, W. Glycolytic metabolism and tumour response to fractionated irradiation. Radiotherapy and oncology 2010, 94, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R. Hyaluronidases in cancer biology. InHyaluronan in Cancer Biology 2009 (pp. 207-220). Academic Press. Elsevier. Robert Stein Editor. First Edition Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- de la Cruz-López, K.G.; Castro-Muñoz, L.J.; Reyes-Hernández, D.O.; García-Carrancá, A.; Manzo-Merino, J. Lactate in the regulation of tumor microenvironment and therapeutic approaches. Frontiers in oncology 2019, 9, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San-Millán, I.; Julian, C.G.; Matarazzo, C.; Martinez, J.; Brooks, G.A. Is lactate an oncometabolite? Evidence supporting a role for lactate in the regulation of transcriptional activity of cancer-related genes in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Frontiers in oncology 2020, 9, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, L.T.; Wellen, K.E. Histone lactylation links metabolism and gene regulation. Nature 2019, 574, 492–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Qu, K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J. Lactylation: a Passing Fad or the Future of Posttranslational Modification. Inflammation 2022, 45, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Gu, Y.; Cang, W.; Sun, P.; Xiang, Y. Lactate-Lactylation Hands between Metabolic Reprogramming and Immunosuppression. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, G.A. The tortuous path of lactate shuttle discovery: From cinders and boards to the lab and ICU. Journal of sport and health science 2020, 9, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopp, A.K.; Grüter, P.; Hottiger, M.O. Regulation of glucose metabolism by NAD+ and ADP-ribosylation. Cells 2019, 8, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocianova, E.; Piatrikova, V.; Golias, T. Revisiting the Warburg Effect with Focus on Lactate. Cancers 2022, 14, 6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, M.; Wan, J.; Cai, K.; Song, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Hu, J. Understanding the contribution of lactate metabolism in cancer progress: a perspective from isomers. Cancers 2022, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Harman, E.M.; Curry, S.H.; Baumgartner, T.G.; Misbin, R.I. Treatment of lactic acidosis with dichloroacetate. New England Journal of Medicine 1983, 309, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Lorenz, A.C.; Thomas, R.G.; Harman, E.M. Dichloroacetate in the treatment of lactic acidosis. Annals of internal medicine 1988, 108, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Kerr, D.S.; Barnes, C.; Bunch, S.T.; Carney, P.R.; Fennell, E.M.; Felitsyn, N.M.; Gilmore, R.L.; Greer, M.; Henderson, G.N.; Hutson, A.D. Controlled clinical trial of dichloroacetate for treatment of congenital lactic acidosis in children. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irsigler, K.; Brändle, J.; Kaspar, L.; Kritz, H.; Lageder, H.; Regal, H. Treament of biguanide-induced lactic acidosis with dichloroacetate. 3 case histories. Arzneimittel-Forschung 1979, 29, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Wright, E.C.; Baumgartner, T.G.; Bersin, R.M.; Buchalter, S.; Curry, S.H.; Duncan, C.A.; Harman, E.M.; Henderson, G.N.; Jenkinson, S.; Lachin, J.M. A controlled clinical trial of dichloroacetate for treatment of lactic acidosis in adults. New England Journal of Medicine 1992, 327, 1564–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, S.; Agbenyega, T.; Angus, B.J.; Bedu-Addo, G.; Ofori-Amanfo, G.; Henderson, G.; Szwandt, I.S.; O'BRIEN, R. , Stacpoole, P.W. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dichloroacetate in children with lactic acidosis due to severe malaria. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 1995, 88, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Barnes, C.L.; Hurbanis, M.D.; Cannon, S.L.; Kerr, D.S. Treatment of congenital lactic acidosis with dichloroacetate. Archives of disease in childhood 1997, 77, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, S.; Archer, S.L.; Allalunis-Turner, J.; Haromy, A.; Beaulieu, C.; Thompson, R.; Lee, C.T.; Lopaschuk, G.D.; Puttagunta, L.; Bonnet, S.; Harry, G. A mitochondria-K+ channel axis is suppressed in cancer and its normalization promotes apoptosis and inhibits cancer growth. Cancer cell 2007, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plas, D.R.; Thompson, C.B. Cell metabolism in the regulation of programmed cell death. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2002, 13, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbenyega, T.; Planche, T.; Bedu-Addo, G.; Ansong, D.; Owusu-Ofori, A.; Bhattaram, V.A.; Nagaraja, N.V.; Shroads, A.L.; Henderson, G.N.; Hutson, A.D.; Derendorf, H. Population kinetics, efficacy, and safety of dichloroacetate for lactic acidosis due to severe malaria in children. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2003, 43, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2005. Dichloroacetic Acid in Drinking-water Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality. Downloaded December 26, 2023 from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/wash-documents/wash-chemicals/dichloroaceticacid0505.pdf?sfvrsn=2246389b_4.

- Stacpoole, P.W. Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology of GSTZ1/MAAI. Biochemical Pharmacology 2023, 115818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, S.H.; Lorenz, A.; Chu, P.I.; Limacher, M.; Stacpoole, P.W. Disposition and pharmacodynamics of dichloroacetate (DCA) and oxalate following oral DCA doses. Biopharm Drug Dispos 1991, 12, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharmacokinetics of Sodium Dichloroacetate. PhD dissertation. Gainesville, FL:University of Florida, 1987. Downloaded from https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Chu+P-I.+Pharmacokinetics+of+Sodium+Dichloroacetate.+PhD+dissertation.+Gainesville%2C+FL%3AUniversity+of+Florida%2C+1987.&btnG= Accessed February 2023.

- Evans, O.B. Dichloroacetate tissue concentration and its relationship to hypolactatemia and pyruvate dehydrogenase activity by dichloroacetate. Biochemical Pharmacology 1982, 31, 3124–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shroads, A.L.; Guo, X.; Dixit, V.; Liu, H.P.; James, M.O.; Stacpoole, P.W. Age-dependent kinetics and metabolism of dichloroacetate: possible relevance to toxicity. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2008, 324, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, S.C.; Smeltz, M.G.; Hu, Z.; Rowland-Faux, L.; Zhong, G.; Lorenzo, R.J.; Cisneros, K.V.; Stacpoole, P.W.; James, M.O. Regulation of dichloroacetate biotransformation in rat liver and extrahepatic tissues by GSTZ1 expression and chloride concentration. Biochem Pharmacol 2018, 152, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- James, M.O.; Yan, Z.; Cornett, R.; Jayanti, V.M.; Henderson, G.N.; Davydova, N.; Katovich, M.J.; Pollock, B.; Stacpoole, P.W. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of [14C] dichloroacetate in male sprague-dawley rats: Identification of glycine conjugates, including hippurate, as urinary metabolites of dichloroacetate. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 1998, 26, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wells, P.G.; Moore, G.W.; Rabin, D.; Wilkinson, G.R.; Oates, J.A.; Stacpoole, P.W. Metabolic effects and pharmacokinetics of intravenously administered dichloroacetate in humans. Diabetologia 1980, 19, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W. The pharmacology of dichloroacetate. Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental 1989, 38, 1124–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Moore, G.W.; Kornhauser, D.M. Metabolic effects of dichloroacetate in patients with diabetes mellitus and hyperlipoproteinemia. N Engl J Med 1978, 298, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Leon, A.; Schultz, I.R.; Xu, G.; Bull, R.J. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of dichloroacetate in the F344 rat after prior administration in drinking water. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 1997, 146, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukas, G.; Vyas, K.H.; Brindle, S.D.; Le Sher, A.R.; Wagner, W.E. Biological disposition of sodium dichloroacetate in animals and humans after intravenous administration. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 1980, 69, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisenbacher, H.W.; Shroads, A.L.; Zhong, G.; Daigle, A.D.; Abdelmalak, M.M.; Samper, I.S.; Mincey, B.D.; James, M.O.; Stacpoole, P.W. Pharmacokinetics of oral dichloroacetate in dogs. Journal of biochemical and molecular toxicology 2013, 27, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.J.; Lane, J.R.; Turkel, C.C.; Capparelli, E.V.; Dziewanowska, Z.; Fox, A.W. Dichloroacetate: population pharmacokinetics with a pharmacodynamic sequential link model. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2001, 41, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Henderson, G.N.; Yan, Z.; James, M.O. Clinical pharmacology and toxicology of dichloroacetate. Environmental health perspectives 1998, 106, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelakis, E.D.; Webster, L.; Mackey, J.R. Dichloroacetate (DCA) as a potential metabolic-targeting therapy for cancer. British journal of cancer 2008, 99, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwin, L.H.; Yu, S.X.; Borgel, S.; Hancock, C.; Wolfe, T.L.; Phillips, L.R.; Hollingshead, M.G.; Newton, D.L. Sodium dichloroacetate selectively targets cells with defects in the mitochondrial ETC. International journal of cancer 2010, 127, 2510–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin-Teodosiu, D. Regulation of muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in insulin resistance: effects of exercise and dichloroacetate. Diabetes & metabolism journal 2013, 37, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denton, R.M.; McCormack, J.G.; Rutter, G.A.; Burnett, P.; Edgell, N.J.; Moule, S.K.; Diggle, T.A. The hormonal regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Advances in enzyme regulation 1996, 36, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenmann, N.; Tannenbaum, N.; Hodgeman, R.M.; Raju, R.P. Regulating mitochondrial metabolism by targeting pyruvate dehydrogenase with dichloroacetate, a metabolic messenger. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, K.M.; Zhao, Y.; Shimomura, Y.; Kuntz, M.J.; Harris, R.A. Branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase. Molecular cloning, expression, and sequence similarity with histidine protein kinases. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1992, 267, 13127–13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudi, R.; Melissa, M.B.; Kedishvili, N.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Popov, K.M. Diversity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase gene family in humans. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270, 28989–28994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowles, J.; Scherer, S.W.; Xi, T.; Majer, M.; Nickle, D.C.; Rommens, J.M.; Popov, K.M.; Harris, R.A.; Riebow, N.L.; Xia, J.; Tsui, L.C. Cloning and characterization of PDK4 on 7q21. 3 encoding a fourth pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzyme in human. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1996, 271, 22376–22382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.C. Coming up for air: HIF-1 and mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab 2006, 3, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, I.; Cairns, R.A.; Fontana, L.; Lim, A.L.; Denko, N.C. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell metabolism 2006, 3, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degenhardt, T.; Saramäki, A.; Malinen, M.; Rieck, M.; Väisänen, S.; Huotari, A.; Herzig, K.H.; Müller, R.; Carlberg, C. Three members of the human pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase gene family are direct targets of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ. Journal of molecular biology 2007, 372, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Peters, J.M.; Harris, R.A. Adaptive increase in pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 during starvation is mediated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2001, 287, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contractor, T.; Harris, C.R. p53 negatively regulates transcription of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase Pdk2. Cancer research 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeaman, S.J.; Hutcheson, E.T.; Roche, T.E.; Pettit, F.H.; Brown, J.R.; Reed, L.J.; Watson, D.C.; Dixon, G.H. Sites of phosphorylation on pyruvate dehydrogenase from bovine kidney and heart. Biochemistry 1978, 17, 2364–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowker-Kinley, M.M.; Davis, I.W.; Pengfei, W.U.; Harris, A.R.; Popov, MK. Evidence for existence of tissue-specific regulation of the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochemical Journal 1998, 329, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.S.; Ramos, H.; Soares, J.; Saraiva, L. p53 and glucose metabolism: an orchestra to be directed in cancer therapy. Pharmacological research 2018, 131, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Li, J.; Chuang, J.L.; Chuang, D.T. Distinct structural mechanisms for inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoforms by AZD7545, dichloroacetate, and radicicol. Structure 2007, 15, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, T.; Morley, A. An evolutionary perspective on the Crabtree effect. Frontiers in molecular biosciences 2014, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunier, E.; Benelli, C.; Bortoli, S. The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in cancer: An old metabolic gatekeeper regulated by new pathways and pharmacological agents. International journal of cancer 2016, 138, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holness, M.J.; and Sugden, M.C. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity by reversible phosphorylation. Biochem. Soc. Trans 2003, 31, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehouse, S.; Cooper, R.H.; Randle, P.J. Mechanism of activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase by dichloroacetate and other halogenated carboxylic acids. Biochemical Journal 1974, 141, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankotia, S.; Stacpoole, P.W. Dichloroacetate and cancer: new home for an orphan drug? . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Cancer 2014, 1846, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehouse, S.; Randle, P.J. Activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase in perfused rat heart by dichloroacetate (Short Communication). Biochem J 1973, 134, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorini, M.; Ciman, M. Hypoglycaemic action of diisopropylammonium salts in experimental diabetes. Biochemical pharmacology 1962, 11, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albatany, M.; Li, A.; Meakin, S.; Bartha, R. Dichloroacetate induced intracellular acidification in glioblastoma: in vivo detection using AACID-CEST MRI at 9.4 Tesla. Journal of neuro-oncology 2018, 136, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anemone, A.; Consolino, L.; Conti, L.; Reineri, F.; Cavallo, F.; Aime, S.; Longo, D.L. In vivo evaluation of tumour acidosis for assessing the early metabolic response and onset of resistance to dichloroacetate by using magnetic resonance pH imaging. International journal of oncology 2017, 51, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albatany, M.; Li, A.; Meakin, S.; Bartha, R. In vivo detection of acute intracellular acidification in glioblastoma multiforme following a single dose of cariporide. International journal of clinical oncology 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Li, X.; Xiong, H.; Zhou, P.; Ni, Z.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; He, J.; Yang, F.; Zhang, N. Inhibition of COX2 enhances the chemosensitivity of dichloroacetate in cervical cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 51748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, G.M.; Ho, K.L.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Treading slowly through hypoxic waters: dichloroacetate to the rescue! J Physiol 2018, 596, 2957–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolbright, B.L.; Rajendran, G.; Harris, R.A.; Taylor JA 3rd. Metabolic Flexibility in Cancer: Targeting the Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase:Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Axis. Mol Cancer Ther 2019, 18, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Lee, W.D.; Leitner, B.P.; Zhu, W.; Fosam, A.; Li, Z.; Gaspar, R.C.; Halberstam, A.A.; Robles, B.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Perry, R.J. Dichloroacetate as a novel pharmaceutical treatment for cancer-related fatigue in melanoma. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2023, 325, E363–E375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Razek, E.A.; Mahmoud, H.M.; Azouz, A.A. Management of ulcerative colitis by dichloroacetate: Impact on NFATC1/NLRP3/IL1B signaling based on bioinformatics analysis combined with in vivo experimental verification. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W. Therapeutic targeting of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex/pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDC/PDK) axis in cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2017, 109, djx071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tataranni, T.; Piccoli, C. Dichloroacetate (DCA) and cancer: an overview towards clinical applications. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2019, 2019, 8201079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Felts, J.M. Diisopropylammonium dichloroacetate (DIPA) and sodium dichloroacetate (DCA): Effect on glucose and fat metabolism in normal and diabetic tissue. Metabolism 1970, 19, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacpoole, P.W.; Harwood, H.J.; Varnado, C.E. Regulation of rat liver hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase by a new class of noncompetitive inhibitors. Effects of dichloroacetate and related carboxylic acids on enzyme activity. The Journal of clinical investigation 1983, 72, 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.W.; Swift, L.L.; Rabinowitz, D.; Crofford, O.B.; Oates, J.A.; Stacpoole, P.W. Reduction of serum cholesterol in two patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia by dichloroacetate. Atherosclerosis 1979, 33, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stakišaitis, D.; Kapočius, L.; Kilimaitė, E.; Gečys, D.; Šlekienė, L.; Balnytė, I.; Palubinskienė, J.; Lesauskaitė, V. Preclinical Study in Mouse Thymus and Thymocytes: Effects of Treatment with a Combination of Sodium Dichloroacetate and Sodium Valproate on Infectious Inflammation Pathways. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; Ding, J. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Li, P.; Sun, Z. Histone lactylation regulates cancer progression by reshaping the tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Huang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Hou, J.; Tian, M.; Li, J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; Li, Z. Lactate modulates cellular metabolism through histone lactylation-mediated gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Frontiers in oncology 2021, 11, 647559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Ye, Z.; Li, Z.; Jing, D.S.; Fan, G.X.; Liu, M.Q.; Zhuo, Q.F.; Ji, S.R.; Yu, X.J.; Xu, X.W.; Qin, Y. Lactate-induced protein lactylation: A bridge between epigenetics and metabolic reprogramming in cancer. Cell proliferation 2023, e13478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Lv, Y.; Dai, X. Lactate, histone lactylation and cancer hallmarks. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Zheng, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, A.; Qin, Y.; Qin, Z.; Zheng, X. The function and mechanism of lactate and lactylation in tumor metabolism and microenvironment. Genes & Diseases 2023, 10, 2029–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zou, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, A.; Li, N.; Ma, Z. Identification of lactylation related model to predict prognostic, tumor infiltrating immunocytes and response of immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1149989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Cheng, Y. Hypoxia-induced SHMT2 protein lactylation facilitates glycolysis and stemness of esophageal cancer cells. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2024, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Zheng, Z.; Bian, C.; Chang, S.; Bao, J.; Yu, H.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. Functions and mechanisms of lactylation in carcinogenesis and immunosuppression. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1253064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ying, T.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sheng, J.; Teng, L.; Luo, C. BRAFV600E restructures cellular lactylation to promote anaplastic thyroid cancer proliferation. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X. Hypoxia induced β-catenin lactylation promotes the cell proliferation and stemness of colorectal cancer through the wnt signaling pathway. Experimental Cell Research 2023, 422, 113439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rho, H.; Terry, A.R.; Chronis, C.; Hay, N. Hexokinase 2-mediated gene expression via histone lactylation is required for hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Cell metabolism 2023, 35, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fan, W.; Li, N.; Ma, Y.; Yao, M.; Wang, G.; He, S.; Li, W.; Tan, J.; Lu, Q.; Hou, S. YY1 lactylation in microglia promotes angiogenesis through transcription activation-mediated upregulation of FGF2. Genome Biology 2023, 24, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Mang, G.; Chen, J.; Yan, X.; Tong, Z.; Yang, Q.; Wang, M.; Chen, L.; Sun, P. Histone lactylation boosts reparative gene activation post–myocardial infarction. Circulation Research 2022, 131, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Ji, Z.; Gong, Y.; Fan, L.; Xu, P.; Chen, X.; Miao, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, W.; Ma, P.; Zhao, H. Numb/Parkin-directed mitochondrial fitness governs cancer cell fate via metabolic regulation of histone lactylation. Cell reports 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, M.; Chen, Y. Proteomic analysis identifies PFKP lactylation in SW480 colon cancer cells. Iscience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; He, T.; Meng, D.; Lv, W.; Ye, J.; Cheng, L.; Hu, J. BZW2 Modulates Lung Adenocarcinoma Progression through Glycolysis-Mediated IDH3G Lactylation Modification. Journal of Proteome Research 2023, 22, 3854–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.; Mao, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Wen, Q.; Yu, S.C. Beyond metabolic waste: lysine lactylation and its potential roles in cancer progression and cell fate determination. Cellular Oncology 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varner, E.L.; Trefely, S.; Bartee, D.; von Krusenstiern, E.; Izzo, L.; Bekeova, C.; O'Connor, R.S.; Seifert, E.L.; Wellen, K.E.; Meier, J.L.; Snyder, N.W. Quantification of lactoyl-CoA (lactyl-CoA) by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry in mammalian cells and tissues. Open Biology 2020, 10, 200187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Yruela, C.; Bæk, M.; Monda, F.; Olsen, C.A. Chiral posttranslational modification to lysine ε-amino groups. Accounts of Chemical Research 2022, 55, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Kumar, A.; Lokhande, K.B.; Swamy, K.V.; Sharma, N.K. Molecular Docking and Simulation Studies Predict Lactyl-CoA as the Substrate for P300 Directed Lactylation. This manuscript has been released as a Pre-Print at “bioRxiv” downloaded from https://chemrxiv.org/engage/api-gateway/chemrxiv/assets/orp/resource/item/60c74e8d4c8919380fad3a55/original/molecular-docking-and-simulation-studies-predict-lactyl-co-a-as-the-substrate-for-p300-directed-lactylation.pdf. Accessed 02/21/2024.

- Wu, H.; Huang, H.; Zhao, Y. Interplay between metabolic reprogramming and post-translational modifications: from glycolysis to lactylation. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Koo, J.S. Glucose metabolism and glucose transporters in breast cancer. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2021, 9, 728759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, B. Glycolysis-related lncRNA TMEM105 upregulates LDHA to facilitate breast cancer liver metastasis via sponging miR-1208. Cell Death & Disease 2023, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreier, A.; Zappasodi, R.; Serganova, I.; Brown, K.A.; Demaria, S.; Andreopoulou, E. Facts and Perspectives: Implications of tumor glycolysis on immunotherapy response in triple negative breast cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2023, 12, 1061789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, A.; Ulloa, V.; Rodríguez, F.; Reinicke, K.; Yañez, A.J.; García, M.D.; Medina, R.A.; Carrasco, M.; Barberis, S.; Castro, T.; Martínez, F. Differential subcellular distribution of glucose transporters GLUT1–6 and GLUT9 in human cancer: ultrastructural localization of GLUT1 and GLUT5 in breast tumor tissues. Journal of cellular physiology 2006, 207, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciavardelli, D.; Rossi, C.; Barcaroli, D.; Volpe, S.; Consalvo, A.; Zucchelli, M.; De Cola, A.; Scavo, E.; Carollo, R.; D'agostino, D.; Forlì, F. Breast cancer stem cells rely on fermentative glycolysis and are sensitive to 2-deoxyglucose treatment. Cell death & disease 2014, 5, e1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, Y.M.; Shin, Y.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, S.; Jeong, S.H.; Kong, H.K.; Park, E.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Han, J.; Chang, M.; Park, J.H. Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis represses Akt/mTOR/HIF-1α axis and restores tamoxifen sensitivity in antiestrogen-resistant breast cancer cells. PloS one 2015, 10, e0132285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littleflower, A.B.; Parambil, S.T.; Antony, G.R.; Subhadradevi, L. The determinants of metabolic discrepancies in aerobic glycolysis: Providing potential targets for breast cancer treatment. Biochimie 2024, 220(107) 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, E.L.; Eubank, W.B.; Mankoff, D.A. FDG PET, PET/CT, and breast cancer imaging. Radiographics 2007, 207, S215–S229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.C.; Fadia, M.; Dahlstrom, J.E.; Parish, C.R.; Board, P.G.; Blackburn, A.C. Reversal of the glycolytic phenotype by dichloroacetate inhibits metastatic breast cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Breast cancer research and treatment 2010, 120, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, B.P.; Dilda, P.J.; Hogg, P.J.; Blackburn, A.C. Dichloroacetate reverses the Warburg effect, inhibiting growth and sensitizing breast cancer cells towards apoptosis. Proceedings of the 103rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2012 Mar 31-Apr 4; Chicago, IL. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; C.ancer Res 2012;72(8 Suppl):Abstract nr 3228.

- Harting, T.P.; Stubbendorff, M.; Hammer, S.C.; Schadzek, P.; Ngezahayo, A.; Escobar, H.M.; Nolte, I. Dichloroacetate affects proliferation but not apoptosis in canine mammary cell lines. PloS one 2017, 12, e0178744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Preter, G. , Neveu, M.-A., Danhier, P., Brisson, L., Payen, V.L., Porporato, P.E., … Gallez, B. (2016). Inhibition of the pentose phosphate pathway by dichloroacetate unravels a missing link between aerobic glycolysis and cancer cell proliferation. ( 7(3), 2910–2920. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, A.C.; Rooke, M.; Sun, R.C.; Fadia, M.; Dahlstrom, J.E.; Board, P.G. Reversal of the glycolytic phenotype with dichloroacetate in a mouse mammary adenocarcinoma model. Pathology 2010, 42, S61–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liao, C.; Hu, Y.; Pan, Q.; Jiang, J. Sensitization of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel by dichloroacetate through inhibiting autophagy. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2017, 489, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.H. , Seo, S.-K., Park, Y., Kim, E.-K., Seong, M.-K., Kim, H.-A., … Park, I.-C. (). Dichloroacetate potentiates tamoxifen-induced cell death in breast cancer cells via downregulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 59809–59819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugrud, A.B.; Zhuang, Y.; Coppock, J.D.; Miskimins, W.K. Dichloroacetate enhances apoptotic cell death via oxidative damage and attenuates lactate production in metformin-treated breast cancer cells. Breast cancer research and treatment 2014, 147, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.C.; Board, P.G.; Blackburn, A.C. Targeting metabolism with arsenic trioxide and dichloroacetate in breast cancer cells. Molecular cancer 2011, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Lam, Y.M.; Leung, Y.C.; Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Cheung, E.; Tam, K.Y. Combined use of arginase and dichloroacetate exhibits anti-proliferative effects in triple negative breast cancer cells. J Pharm Pharmacol 2019, 71, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robey, I.F.; Martin, N.K. Bicarbonate and dichloroacetate: evaluating pH altering therapies in a mouse model for metastatic breast cancer. BMC cancer 2011, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.E.; Shin, K.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Seo, S.K.; Yun, S.M.; Choe, T.B.; Kim, H.A.; Kim, E.K.; Noh, W.C.; Kim, J.I.; Hwang, C.S. Inhibition of S6K1 enhances dichloroacetate-induced cell death. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2015, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xintaropoulou, C.; Ward, C.; Wise, A.; Marston, H.; Turnbull, A.; Langdon, S.P. A comparative analysis of inhibitors of the glycolysis pathway in breast and ovarian cancer cell line models. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 25677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, N.; Brown, A.; Lloyd, V.; Ouellette, R.; Touaibia, M.; Culf, A.S.; Cuperlovic-Culf, M. 1H NMR metabolomics analysis of the effect of dichloroacetate and allopurinol on breast cancers. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 2014, 93, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 172 de Mey, S.; Dufait, I.; Jiang, H.; Corbet, C.; Wang, H.; Van De Gucht, M.; Kerkhove, L.; Law, K.L.; Vandenplas, H.; Gevaert, T.; Feron, O. Dichloroacetate radiosensitizes hypoxic breast cancer cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, L.; Attari, F.; Talkhabi, M.; Saadatpour, F. MDA-MB-231. Nova Biologica Reperta 2023 10(1):1-10Doi: 10.29252/nbr.10.1.1 Downloaded from https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=12666777980647358402&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5&as_ylo=2023. Accessed January 2024. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cutruzzolà, F.; Giardina, G.; Marani, M.; Macone, A.; Paiardini, A.; Rinaldo, S.; Paone, A. Glucose metabolism in the progression of prostate cancer. Frontiers in physiology 2017, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, L.C.; Franklin, R.B. The clinical relevance of the metabolism of prostate cancer; zinc and tumor suppression: connecting the dots. Molecular cancer 2006, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, E.; Hogg, A.; Binns, D.; Frydenberg, M.; Hicks, R. Investigations with FDG-PET scanning in prostate cancer show limited value for clinical practice. Acta Oncologica 2002, 41, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.J.; Akhurst, T.; Osman, I.; Nunez, R.; Macapinlac, H.; Siedlecki, K.; Verbel, D.; Schwartz, L.; Larson, S.M.; Scher, H.I. Fluorinated deoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Urology 2002, 59, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Yacoub, S.; Shiverick, K.T.; Namiki, K.; Sakai, Y.; Porvasnik, S.; Urbanek, C.; Rosser, C.J. Dichloroacetate (DCA) sensitizes both wild-type and over expressing Bcl-2 prostate cancer cells in vitro to radiation. The Prostate 2008, 68, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, L.H.; Withers, H.G.; Garbens, A.; Love, H.D.; Magnoni, L.; Hayward, S.W.; Moyes, C.D. Hypoxia and the metabolic phenotype of prostate cancer cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics 2009, 1787, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harting, T.; Stubbendorff, M.; Willenbrock, S.; Wagner, S.; Schadzek, P.; Ngezahayo, A.; Escobar, H.M.; Nolte, I. The effect of dichloroacetate in canine prostate adenocarcinomas and transitional cell carcinomas in vitro. International journal of oncology 2016, 49, 2341–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Liang, H.; Guan, G. Dichloroacetate enhances the cytotoxic effect of Cisplatin via decreasing the level of FOXM1 in prostate cancer. Int J Clin Med 2016, 9, 11044–11050. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, U.; Poulsen, T.T.; Ulsperger, E.; Poulsen, H.S.; Geissler, K.; Hamilton, G. In vitro cytotoxicity of combinations of dichloroacetate with anticancer platinum compounds. Clinical pharmacology: advances and applications. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.K.; Bhat, T.A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.; Underwood, W.; Koochekpour, S.; Shourideh, M.; Yadav, N.; Dhar, S.; Chandra, D. Mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated apoptosis resistance associates with defective heat shock protein response in African–American men with prostate cancer. British journal of cancer 2016, 114, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, H.W.; Kasai, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Fukuhara, H.; Karashima, T.; Kurabayashi, A.; Furihata, M.; Hanazaki, K.; Inoue, K.; Ogura, S.I. Metabolic shift towards oxidative phosphorylation reduces cell-density-induced cancer-stem-cell-like characteristics in prostate cancer in vitro. Biology Open 2023, 12, bio059615–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Xia, L.; Oyang, L.; Liang, J.; Tan, S.; Wu, N.; Yi, P.; Pan, Q.; Rao, S.; Han, Y.; Tang, Y. The POU2F1-ALDOA axis promotes the proliferation and chemoresistance of colon cancer cells by enhancing glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway activity. Oncogene 2022, 41, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.S.; Wang, J.Y.; Chung, F.Y.; Lee, S.C.; Huang, M.Y.; Kuo, C.W.; Yang, M.J.; Lin, S.R. Significance of the glycolytic pathway and glycolysis related-genes in tumorigenesis of human colorectal cancers. Oncology reports 2008, 19, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhok, B.M.; Yeluri, S.; Perry, S.L.; Hughes, T.A.; Jayne, D.G. Dichloroacetate induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in colorectal cancer cells. British journal of cancer 2010, 102, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G.; Hill, D.K.; Andrejeva, G.; Boult, J.K.; Troy, H.; Fong, A.L.; Orton, M.R.; Panek, R.; Parkes, H.G.; Jafar, M.; Koh, D.M. Dichloroacetate induces autophagy in colorectal cancer cells and tumours. British journal of cancer 2014, 111, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaney, L.M.; Ho, N.; Morrison, J.; Farias, N.R.; Mosser, D.D.; Coomber, B.L. Dichloroacetate affects proliferation but not survival of human colorectal cancer cells. Apoptosis 2015, 20, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Cheng, X.; Pan, S.; Wang, L.; Dou, W.; Liu, J.; Shi, X. Dichloroacetate attenuates the stemness of colorectal cancer cells via trigerring ferroptosis through sequestering iron in lysosomes. Environmental toxicology 2021, 36, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Xie, G.; He, J.; Li, J.; Pan, F.; Liang, H. Synergistic antitumor effect of dichloroacetate in combination with 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer. BioMed Research International. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hou, L.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Hou, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zou, H.; Gu, Y. Dichloroacetate restores colorectal cancer chemosensitivity through the p53/miR-149-3p/PDK2-mediated glucose metabolic pathway. Oncogene 2020, 39, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zhu, L.; Hou, Y.; Hou, L.; Huang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Zou, H.; Wu, T. Dichloroacetate overcomes oxaliplatin chemoresistance in colorectal cancer through the miR-543/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathway. Journal of Cancer 2019, 10, 6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Andrews, D.; Blackburn, A.C. Long-term stabilization of stage 4 colon cancer using sodium dichloroacetate therapy. World journal of clinical cases 2016, 4, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Meyle, K.D.; Lange, M.K.; Klima, M.; Sanderhoff, M.; Dahl, C.; Abildgaard, C.; Thorup, K.; Moghimi, S.M.; Jensen, P.B.; Bartek, J. Dysfunctional oxidative phosphorylation makes malignant melanoma cells addicted to glycolysis driven by the V600EBRAF oncogene. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenius, J.; Lundeberg, J.; Johansson, H.; Tuominen, R.; Frostvik-Stolt, M.; Hansson, J.; Brage, S.E. High expression of glycolytic and pigment proteins is associated with worse clinical outcome in stage III melanoma. Melanoma research 2013, 23, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Ebert, E.V.; Seitz, T.; Dietrich, P.; Berneburg, M.; Bosserhoff, A.; Hellerbrand, C. Characterization of glycolysis-related gene expression in malignant melanoma. Pathology-Research and Practice 2020, 216, 152752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Molina, M.A.; Mendoza-Gamboa, E.; Sierra-Rivera, C.A.; Zapata-Benavides, P.; Hernandez, D.F.; Chávez-Reyes, A.; Rivera-Morales, L.G.; Tamez-Guerra, R.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C. In vitro and in vivo antitumoral activitiy of sodium dichloroacetate (DCA-Na) against murine melanoma. African Journal of Microbiology Research 2012, 6, 4782–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaube, B.; Malvi, P.; Singh, S.V.; Mohammad, N.; Meena, A.S.; Bhat, M.K. Targeting metabolic flexibility by simultaneously inhibiting respiratory complex I and lactate generation retards melanoma progression. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 37281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pópulo, H.; Caldas, R.; Lopes, J.M.; Pardal, J.; Máximo, V.; Soares, P. Overexpression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase supports dichloroacetate as a candidate for cutaneous melanoma therapy. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets 2015, 19, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abildgaard, C.; Dahl, C.; Basse, A.L.; Ma, T.; Guldberg, P. Bioenergetic modulation with dichloroacetate reduces the growth of melanoma cells and potentiates their response to BRAF V600E inhibition. Journal of translational medicine 2014, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.F.; Shen, S.Y. DCA increases the antitumor effects of capecitabine in a mouse B16 melanoma allograft and a human non-small cell lung cancer A549 xenograft. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology 2013, 72, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Andrews, D.; Shainhouse, J.; Blackburn, A.C. Long-term stabilization of metastatic melanoma with sodium dichloroacetate. World journal of clinical oncology 2017, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuss, A.M.; Groos, D.; Buchfelder, M.; Savaskan, N. The acidic brain—glycolytic switch in the microenvironment of malignant glioma. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shingu, T.; Feng, L.; Chen, Z.; Ogasawara, M.; Keating, M.J.; Kondo, S.; Huang, P. Metabolic alterations in highly tumorigenic glioblastoma cells: preference for hypoxia and high dependency on glycolysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 32843–32853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanzey, M.; Abdul Rahim, S.A.; Oudin, A.; Dirkse, A.; Kaoma, T.; Vallar, L.; Herold-Mende, C.; Bjerkvig, R.; Golebiewska, A.; Niclou, S.P. Comprehensive analysis of glycolytic enzymes as therapeutic targets in the treatment of glioblastoma. PloS one 2015, 10, e0123544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanke, K.M.; Wilson, C.; Kidambi, S. High expression of glycolytic genes in clinical glioblastoma patients correlates with lower survival. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 8, 752404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKelvey, K.J.; Wilson, E.B.; Short, S.; Melcher, A.A.; Biggs, M.; Diakos, C.I.; Howell, V.M. Glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation inhibition improves survival in glioblastoma. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11, 633210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelakis, E.D.; Sutendra, G.; Dromparis, P.; Webster, L.; Haromy, A.; Niven, E.; Maguire, C.; Gammer, T.L.; Mackey, J.R.; Fulton, D.; Abdulkarim, B. Metabolic modulation of glioblastoma with dichloroacetate. Science translational medicine 2010, 2, 31ra34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ren, W.; Wang, X.; Yu, K.F.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q. Antitumor activity of dichloroacetate on C6 glioma cell: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. OncoTargets and therapy. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K. , Wigfield, S., Gee, H.E., Devlin, C.M., Singleton, D., Li, J.-L., … Ivan, M. (2013). Dichloroacetate Reverses the Hypoxic Adaptation to Bevacizumab and Enhances its Antitumor Effects in Mouse Xenografts. ( 91(6), 749–758. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morfouace, M.; Lalier, L.; Oliver, L.; Cheray, M.; Pecqueur, C.; Cartron, P.F.; Vallette, F.M. Control of glioma cell death and differentiation by PKM2–Oct4 interaction. Cell death & disease 2014, 5, e1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesnik, D.L.; Pyaskovskaya, O.N.; Boichuk, I.V.; Solyanik, G.I. Hypoxia enhances antitumor activity of dichloroacetate. Experimental oncology. 2: 4). [PubMed]

- Vella, S.; Conti, M.; Tasso, R.; Cancedda, R.; Pagano, A. Dichloroacetate inhibits neuroblastoma growth by specifically acting against malignant undifferentiated cells. International journal of cancer 2012, 130, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sradhanjali, S.; Tripathy, D.; Rath, S.; Mittal, R.; Reddy, M.M. Overexpression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 in retinoblastoma: A potential therapeutic opportunity for targeting vitreous seeds and hypoxic regions. PloS one 2017, 12, e0177744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.M.; Recht, L.D.; Josan, S.; Merchant, M.; Jang, T.; Yen, Y.F.; Hurd, R.E.; Spielman, D.M.; Mayer, D. Metabolic response of glioma to dichloroacetate measured in vivo by hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Neuro-oncology 2013, 15, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorchuk, A.G.; Pyaskovskaya, O.N.; Gorbik, G.V.; Prokhorova, I.V.; Kolesnik, D.L.; Solyanik, G.I. Effectiveness of sodium dichloroacetate against glioma C6 depends on administration schedule and dosage. Exp Oncol. [PubMed]

- Wicks, R.T.; Azadi, J.; Mangraviti, A.; Zhang, I.; Hwang, L.; Joshi, A.; Bow, H.; Hutt-Cabezas, M.; Martin, K.L.; Rudek, M.A.; Zhao, M. Local delivery of cancer-cell glycolytic inhibitors in high-grade glioma. Neuro-oncology 2014, 17, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsakova, L.; Krasko, J.A.; Stankevicius, E. Metabolic-targeted combination therapy with dichloroacetate and metformin suppresses glioblastoma cell line growth in vitro and in vivo. in vivo 2021, 35, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Hau, E.; Joshi, S.; Dilda, P.J.; McDonald, K.L. Sensitization of glioblastoma cells to irradiation by modulating the glucose metabolism. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2015, 14, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, K.M. , Shen, H., McKelvey, K.J., Gee, H.E., & Hau, E. (2021). Targeting glucose metabolism of cancer cells with dichloroacetate to radiosensitize high-grade gliomas. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Finniss, S.; Cazacu, S.; Xiang, C.; Brodie, Z.; Mikkelsen, T.; Poisson, L.; Shackelford, D.B.; Brodie, C. Repurposing phenformin for the targeting of glioma stem cells and the treatment of glioblastoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 56456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokhorova, I.V.; Pyaskovskaya, O.N.; Kolesnik, D.L.; Solyanik, G.I. Influence of metformin, sodium dichloroacetate and their combination on the hematological and biochemical blood parameters of rats with gliomas C6. Experimental oncology. 2018. Т. 40, № 3. — С. 205-210. [PubMed]

- Kolesnik, D.L.; Pyaskovskaya, O.N.; Yurchenko, O.V.; Solyanik, G.I. Metformin enhances antitumor action of sodium dichloroacetate against glioma C6. Experimental Oncology 2019, 41, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Yu, M.; Tsoli, M.; Chang, C.; Joshi, S.; Liu, J.; Ryall, S.; Chornenkyy, Y.; Siddaway, R.; Hawkins, C.; Ziegler, D.S. Targeting reduced mitochondrial DNA quantity as a therapeutic approach in pediatric high-grade gliomas. Neuro-oncology 2020, 22, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, C.; Wang, D. Phosphorylated form of pyruvate dehydrogenase α1 mediates tumor necrosis factor α-induced glioma cell migration. Oncology Letters 2021, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraj, T.; García-Romero, N.; Carrión-Navarro, J.; Madurga, R.; Ortiz de Mendivil, A.; Prat-Acin, R.; Garcia-Cañamaque, L.; Ayuso-Sacido, A. Beyond the Warburg effect: Oxidative and glycolytic phenotypes coexist within the metabolic heterogeneity of glioblastoma. Cells 2021, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griguer, C.E.; Oliva, C.R.; Gillespie, G.Y. Glucose metabolism heterogeneity in human and mouse malignant glioma cell lines. Journal of neuro-oncology. [CrossRef]

- Shibao, S.; Minami, N.; Koike, N.; Fukui, N.; Yoshida, K.; Saya, H.; Sampetrean, O. Metabolic heterogeneity and plasticity of glioma stem cells in a mouse glioblastoma model. Neuro-oncology 2018, 20, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boag, J.M.; Beesley, A.H.; Firth, M.J.; Freitas, J.R.; Ford, J.; Hoffmann, K.; Cummings, A.J.; de Klerk, N.H.; Kees, U.R. Altered glucose metabolism in childhood pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leukemia 2006, 20, 1731–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulleman, E.; Kazemier, K.M.; Holleman, A.; VanderWeele, D.J.; Rudin, C.M.; Broekhuis, M.J.; Evans, W.E.; Pieters, R.; Den Boer, M.L. Inhibition of glycolysis modulates prednisolone resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Blood 2009, 113, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buentke, E.; Nordström, A.; Lin, H.; Björklund, A.C.; Laane, E.; Harada, M.; Lu, L.; Tegnebratt, T.; Stone-Elander, S.; Heyman, M.; Söderhäll, S.; Porwit, A.; Ostenson, C.G.; Shoshan, M.; Tamm, K.P.; Grandér, D. Glucocorticoid-induced cell death is mediated through reduced glucose metabolism in lymphoid leukemia cells. Blood Cancer, J 2011, 1, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, A.L.; Heng, J.Y.; Beesley, A.H.; Kees, U.R. Bioenergetic modulation overcomes glucocorticoid resistance in T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2014, 165, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, M.; McBrayer, S.K.; Rosen, S.T. Targeting the Warburg effect in hematological malignancies: from PET to therapy. Curr Opin Oncol 2009, 21, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herst, P.M.; Howman, R.A.; Neeson, P.J.; Berridge, M.V.; Ritchie, D.S. The level of glycolytic metabolism in acute myeloid leukemia blasts at diagnosis is prognostic for clinical outcome. Journal of leukocyte biology 2011, 89, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Xia, J.; Xu, H.; Frech, I.; Tricot, G.; Zhan, F. NEK2 promotes aerobic glycolysis in multiple myeloma through regulating splicing of pyruvate kinase. Journal of hematology & oncology 2017, 10, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavriatopoulou, M.; Paschou, S.A.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Metabolic disorders in multiple myeloma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 11430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, W.Y.; McGee, S.L.; Connor, T.; Mottram, B.; Wilkinson, A.; Whitehead, J.P.; Vuckovic, S.; Catley, L. Dichloroacetate inhibits aerobic glycolysis in multiple myeloma cells and increases sensitivity to bortezomib. British journal of cancer 2013, 108, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawano, Y.; Sasano, T.; Arima, Y.; Kushima, S.; Tsujita, K.; Matsuoka, M.; Hata, H. A novel PDK1 inhibitor, JX06, inhibits glycolysis and induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2022, 587, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, S. , Kawano, Y., Yuki, H., Okuno, Y., Nosaka, K., Mitsuya, H., & Hata, H. (2013). PDK1 inhibition is a novel therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. ( 108(1), 170–178. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.D.; Bennett, S.K.; Coupland, L.A.; Forwood, K.; Lwin, Y.; Pooryousef, N.; Tea, I.; Truong, T.T.; Neeman, T.; Crispin, P.; D’Rozario, J. GSTZ1 genotypes correlate with dichloroacetate pharmacokinetics and chronic side effects in multiple myeloma patients in a pilot phase 2 clinical trial. Pharmacology research & perspectives 2019, 7, e00526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voltan, R.; Rimondi, E.; Melloni, E.; Gilli, P.; Bertolasi, V.; Casciano, F.; Rigolin, G.M.; Zauli, G.; Secchiero, P. Metformin combined with sodium dichloroacetate promotes B leukemic cell death by suppressing anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 18965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Kant, S.; Singh, S.M. Antitumor and chemosensitizing action of dichloroacetate implicates modulation of tumor microenvironment: a role of reorganized glucose metabolism, cell survival regulation and macrophage differentiation. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2013, 273, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flavin, D.F. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma reversal with dichloroacetate. Journal of oncology. 2010; Article ID 414726. [CrossRef]

- Strum, S.B.; Adalsteinsson, Ö.; Black, R.R.; Segal, D.; Peress, N.L.; Waldenfels, J. Case report: sodium dichloroacetate (DCA) inhibition of the “Warburg Effect” in a human cancer patient: complete response in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after disease progression with rituximab-CHOP. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes 2013, 45, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramek, J.; Bogucki, J.; Ziaja-Sołtys, M.; Stępniewski, A.; Bogucka-Kocka, A. Effect of sodium dichloroacetate on apoptotic gene expression in human leukemia cell lines. Pharmacological Reports 2019, 71, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnoletto, C.; Melloni, E.; Casciano, F.; Rigolin, G.M.; Rimondi, E.; Celeghini, C.; Brunelli, L.; Cuneo, A.; Secchiero, P.; Zauli, G. Sodium dichloroacetate exhibits anti-leukemic activity in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) and synergizes with the p53 activator Nutlin-3. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnoletto, C.; Brunelli, L.; Melloni, E.; Pastorelli, R.; Casciano, F.; Rimondi, E.; Rigolin, G.M.; Cuneo, A.; Secchiero, P.; Zauli, G. The anti-leukemic activity of sodium dichloroacetate in p53mutated/null cells is mediated by a p53-independent ILF3/p21 pathway. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emadi, A.; Sadowska, M.; Carter-Cooper, B.; Bhatnagar, V.; van der Merwe, I.; Levis, M.J.; Sausville, E.A.; Lapidus, R.G. Perturbation of cellular oxidative state induced by dichloroacetate and arsenic trioxide for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia research 2015, 39, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xintaropoulou, C.; Ward, C.; Wise, A.; Queckborner, S.; Turnbull, A.; Michie, C.O.; Williams, A.R.; Rye, T.; Gourley, C.; Langdon, S.P. Expression of glycolytic enzymes in ovarian cancers and evaluation of the glycolytic pathway as a strategy for ovarian cancer treatment. BMC cancer 2018, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, L.; Chai, W.; Zhao, T.; Jin, X.; Guo, X.; Han, L.; Yuan, C. Dichloroacetic acid upregulates apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells by regulating mitochondrial function. OncoTargets and therapy. 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saed, G.M.; Fletcher, N.M.; Jiang, Z.L.; Abu-Soud, H.M.; Diamond, M.P. Dichloroacetate induces apoptosis of epithelial ovarian cancer cells through a mechanism involving modulation of oxidative stress. Reproductive sciences 2011, 18, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štarha, P.; Trávníček, Z.; Vančo, J.; Dvořák, Z. Half-sandwich Ru (II) and Os (II) bathophenanthroline complexes containing a releasable dichloroacetato ligand. Molecules 2018, 23, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priego-Hernández, V.D.; Arizmendi-Izazaga, A.; Soto-Flores, D.G.; Santiago-Ramón, N.; Feria-Valadez, M.D.; Navarro-Tito, N.; Jiménez-Wences, H.; Martínez-Carrillo, D.N.; Salmerón-Bárcenas, E.G.; Leyva-Vázquez, M.A.; Illades-Aguiar, B. Expression of HIF-1α and Genes Involved in Glucose Metabolism Is Increased in Cervical Cancer and HPV-16-Positive Cell Lines. Pathogens 2022, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Wang, B.S.; Yu, D.H.; Lu, Q.; Ma, J.; Qi, H.; Fang, C.; Chen, H.Z. Dichloroacetate shifts the metabolism from glycolysis to glucose oxidation and exhibits synergistic growth inhibition with cisplatin in HeLa cells. International journal of oncology 2011, 38, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.S.; Ma, X.X. Identification of novel cell glycolysis related gene signature predicting survival in patients with endometrial cancer. Cancer cell international 2019, 19, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.Y.; Huggins, G.S.; Debidda, M.; Munshi, N.C.; De Vivo, I. Dichloroacetate induces apoptosis in endometrial cancer cells. Gynecologic oncology 2008, 109, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, L.H.; Zhou, C.; Bae-Jump, V. Dichloroacetate inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in human endometrial cancer cell lines. Cancer Research. 2016 Jul 15;76(14_Supplement):2993. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Gu, J.D.; Zhou, Q.H. Review of aerobic glycolysis and its key enzymes–new targets for lung cancer therapy. Thoracic cancer 2015, 6, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolle, E.; Leko, P.; Stacher-Priehse, E.; Brcic, L.; El-Heliebi, A.; Hofmann, L.; Quehenberger, F.; Hrzenjak, A.; Popper, H.H.; Olschewski, H.; Leithner, K. Distribution and prognostic significance of gluconeogenesis and glycolysis in lung cancer. Molecular oncology 2020, 14, 2853–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Q.; Fu, Y.L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, K.Y.; Ma, J.; Tang, J.Y.; Zhang, Z.W.; Zhou, Z.Y. Targeting glycolysis in non-small cell lung cancer: Promises and challenges. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 1037341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oylumlu, E.; yin Ng, Y. EVALUATION OF ANTIPROLIFERATIVE EFFECTS OF SODIUM DICHLOROACETATE ON LUNG ADENOCARCINOMA. Turkish Journal of Biochemistry/Turk Biyokimya Dergisi. 2019 Dec 3;44. Downloaded from https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A11%3A2866491/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A140410362&crl=c Accessed 20 december 2023.

- Allen, K.T.; Chin-Sinex, H.; DeLuca, T.; Pomerening, J.R.; Sherer, J.; Watkins III JB, Foley, J. ; Jesseph, J.M.; Mendonca, M.S. Dichloroacetate alters Warburg metabolism, inhibits cell growth, and increases the X-ray sensitivity of human A549 and H1299 NSC lung cancer cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2015, 89, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhou, D.; Hou, B.; Liu, Q.X.; Chen, Q.; Deng, X.F.; Yu, Z.B.; Dai, J.G.; Zheng, H. Dichloroacetate enhances the antitumor efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents via inhibiting autophagy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer management and research. 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. , Zhu, A., Zhou, X., & Wang, F. (2017). Suppression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-2 re-sensitizes paclitaxel-resistant human lung cancer cells to paclitaxel. Oncotarget, 2017; 8, 52642–52650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tam, K.Y. Anti-cancer synergy of dichloroacetate and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in NSCLC cell lines. European journal of pharmacology 2016, 789, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azawi, A.; Sulaiman, S.; Arafat, K.; Yasin, J.; Nemmar, A.; Attoub, S. Impact of sodium dichloroacetate alone and in combination therapies on lung tumor growth and metastasis. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, P.; Ran, M.; Xu, N.; Shan, W.; Sha, O.; Tam, K.Y. Dichloroacetophenone biphenylsulfone ethers as anticancer pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer models. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2023, 378, 110467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiebiger, W.; Olszewski, U.; Ulsperger, E.; Geissler, K.; Hamilton, G. In vitro cytotoxicity of novel platinum-based drugs and dichloroacetate against lung carcinoid cell lines. Clinical and Translational Oncology 2011, 13, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesnik, D.L.; Pyaskovskaya, O.N.; Boychuk, I.V.; Dasyukevich, O.I.; Melnikov, O.R.; Tarasov, A.S.; Solyanik, G.I. Effect of dichloroacetate on Lewis lung carcinoma growth and metastasis. Experimental oncology. 1: 2). [PubMed]

- Feng, M. , Wang, J., & Zhou, J. (2023). Unraveling the therapeutic mechanisms of dichloroacetic acid in lung cancer through integrated multi-omics approaches: metabolomics and transcriptomics. Frontiers in Genetics. [CrossRef]

- Penticuff, J.C. , Woolbright, B.L., Sielecki, T.M., Weir, S.J., and Taylor, J.A. MIF family proteins in genitourinary cancer: Tumorigenic roles and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2019, 16, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobre, C.C.; de Araújo, J.M.; Fernandes, T.A.; Cobucci, R.N.; Lanza, D.C.; Andrade, V.S.; Fernandes, J.V. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): biological activities and relation with cancer. Pathology & Oncology Research. [CrossRef]

- Yasasever, V. , Camlica, H., Duranyildiz, D., Oguz, H., Tas, F., & Dalay, N. (2007). Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in cancer. Cancer investigation, 25(8), 715-719. [CrossRef] [PubMed]