4.1. Einstein Suggestions

In the first paragraph on page one of his manuscript “On the electrodynamics of moving bodies,” [

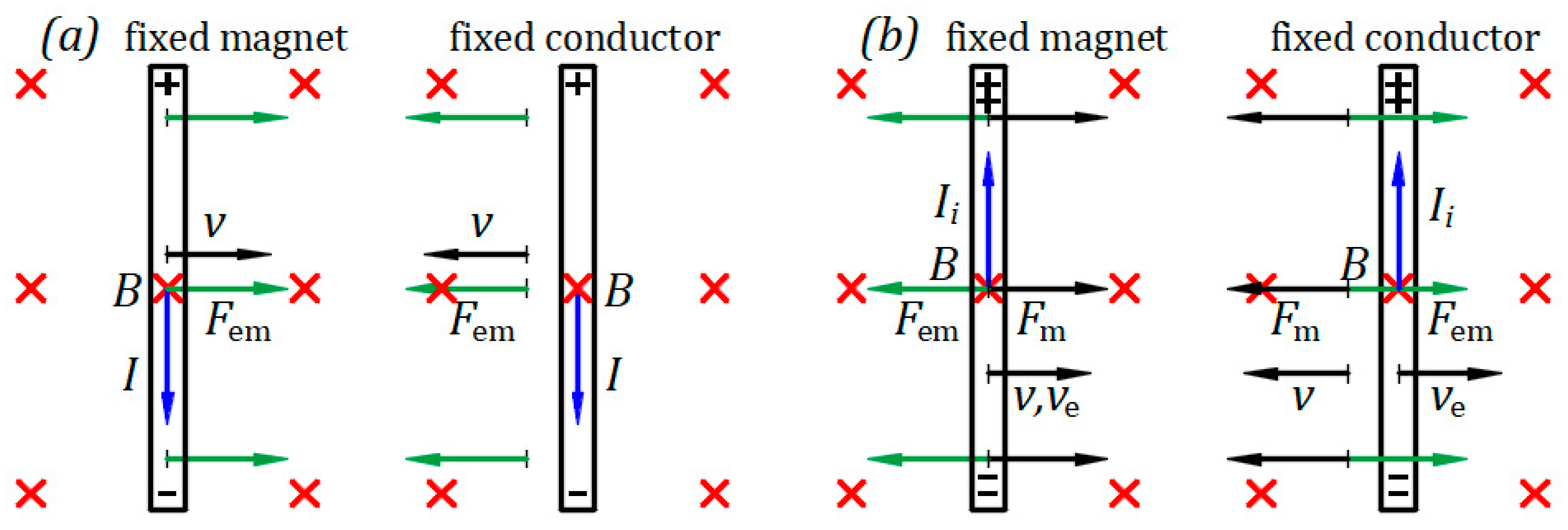

22] Einstein writes the following: “It is known that Maxwell’s electrodynamics—as usually understood at the present time—when applied to moving bodies, leads to asymmetries which do not appear to be inherent in the phenomena. For example, consider the reciprocal electrodynamic action of a magnet and a conductor. The observable phenomenon here depends only on the relative motion of the conductor and magnet, whereas the customary view draws a sharp distinction between the two cases in which either one or the other of these bodies is in motion. If the magnet is in motion and the conductor is at rest, there arises in the neighborhood of the magnet an electric field with a certain definite energy, producing a current at the places where parts of the conductor are situated. However, if the magnet is stationary and the conductor is in motion, no electric field is generated in the neighborhood of the magnet. In the conductor, however, we find an electromotive force, to which in itself there is no corresponding energy, but which gives rise—assuming equality of relative motion in the two cases discussed—to electric currents of the same path and intensity as those produced by the electric forces in the former case.”

Einstein’s example describes a reciprocal experimental observation of a conductor and magnet in proximity when one is in motion/rest and another is at rest/in motion but only when the magnet is in motion an electrical field arises. He may suggest that observations are sufficient to accept reciprocal phenomena symmetrical even if an electromagnetic quantity, such as an electric field, does not occur when the magnet is at rest. Therefore, it is not necessary to rationally understand physical phenomena.

Appendix B shows that in both cases an electric field arises in the conductor, making it an electrical source. Thus, Maxwell’s electrodynamics lead to symmetries when applied to moving bodies; each physical quantity involved in a phenomenon arises and the phenomena can be rationally explained.

Even if the reciprocal phenomena are explained, can we apply the symmetry of phenomena to the symmetry between two inertial frames? Einstein’s example has a magnet and conductor in proximity, and they have reciprocal electromagnetic properties. None of these characteristics applies to a stationary and inertial frame to support special relativity. Origins of the two frames depart from each other and remain nearby for a relatively short time. The frames, including the absolute frame, are hypothetical entities. These tools help us to study and understand physical phenomena. They have no physical properties to transform or duplicate a physical system from one frame to another.

By applying symmetry to two inertial frames, the main idea in special relativity, Einstein unrealistically creates duplicates that lead to irrational conclusions, which are discussed further.

From “Examples of this sort, together with the unsuccessful attempts to discover any motion of the earth relatively to the 'light medium',” Einstein concludes with three suggestions in the second paragraph of page 1:

Einstein rejected the idea of absolute rest. However, the inertial frame considered stationary is a local frame at absolute rest for another inertial frame. The stationary frame was a convenient choice to present his transformational understanding of the phenomenon between the two inertial frames.

- 2.

“… the same laws of electrodynamics and optics will be valid for all frames of reference for which the equations of mechanics hold good.”

The equations/laws of mechanics are valid for phenomena belonging to an inertial frame, but not for the coordinates of phenomena in another inertial frame. However, contrary to the second suggestion, special relativity forces the laws of electrodynamics and optics to hold good for coordinate observations, for which mechanics does not.

- 3.

“… light is always propagated in a vacuum with a definite velocity , which is independent of the state of motion of the emitting body.”

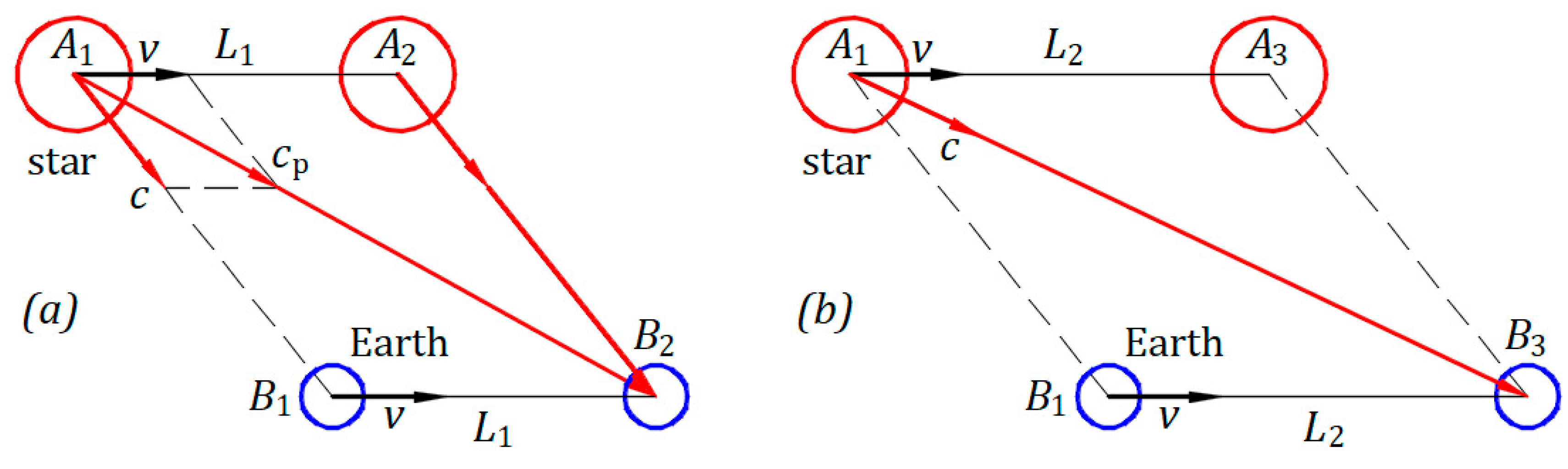

In a stationary frame/local frame at absolute rest, the emitted wavefront from a source at rest travels at the velocity in all directions. The spherical wavefront has continuously its center at the source at rest. However, without considering the ballistic law of light, when the source is in motion at a velocity , the emitted wavefront at an initial instant location of the source travels in the stationary frame at the velocity . In this case, the spherical wavefront has the center at the initial instance location of the source, not at the actual source location. Therefore, there are differences in wave propagation if the source belongs to the stationary or inertial frame.

Without understanding the physical phenomena of his example and the comments from the above suggestions, Einstein has chosen to formulate hypotheses based on observations, elevating them to postulates.

4.3. Lorentz Transformation and Einstein Transformation

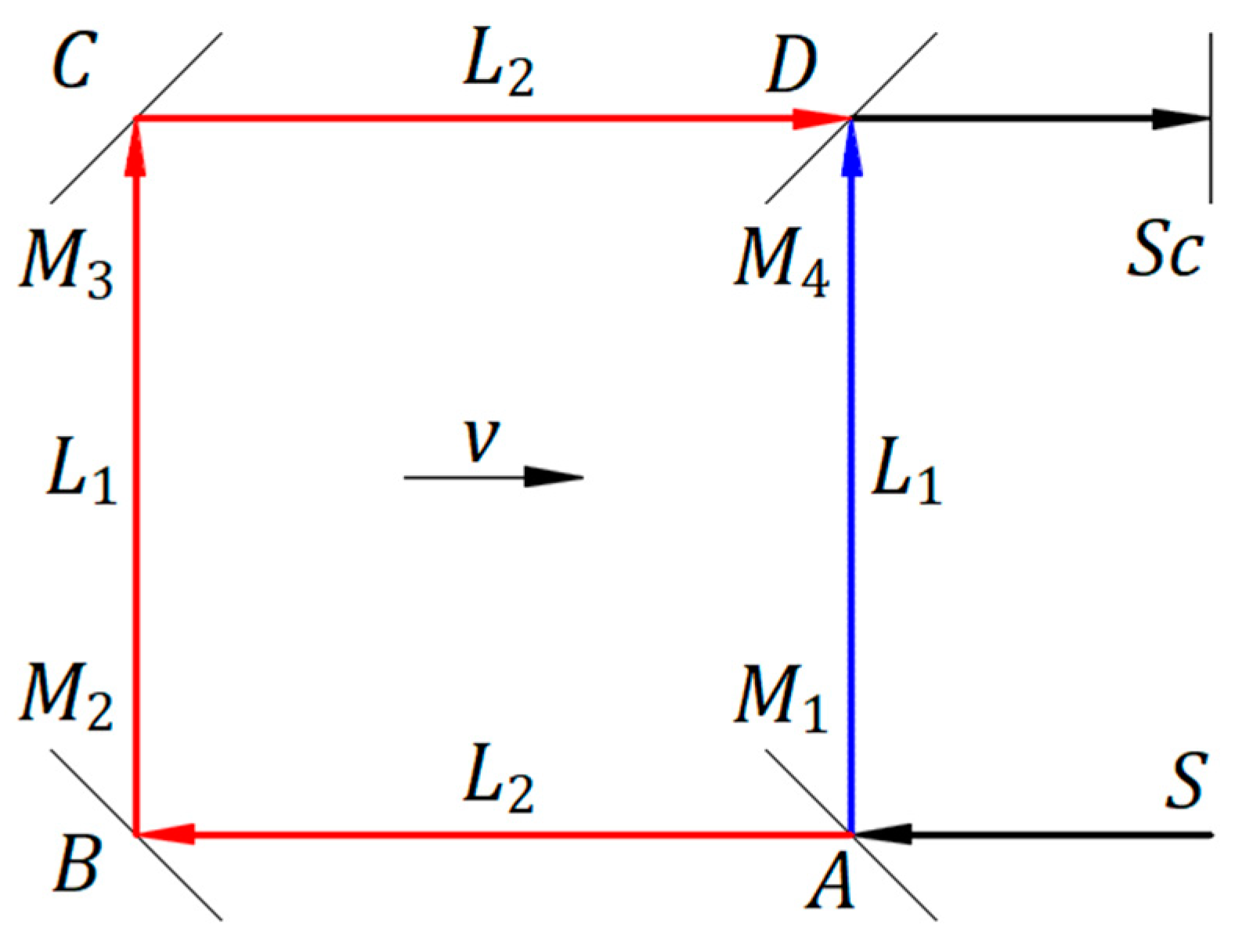

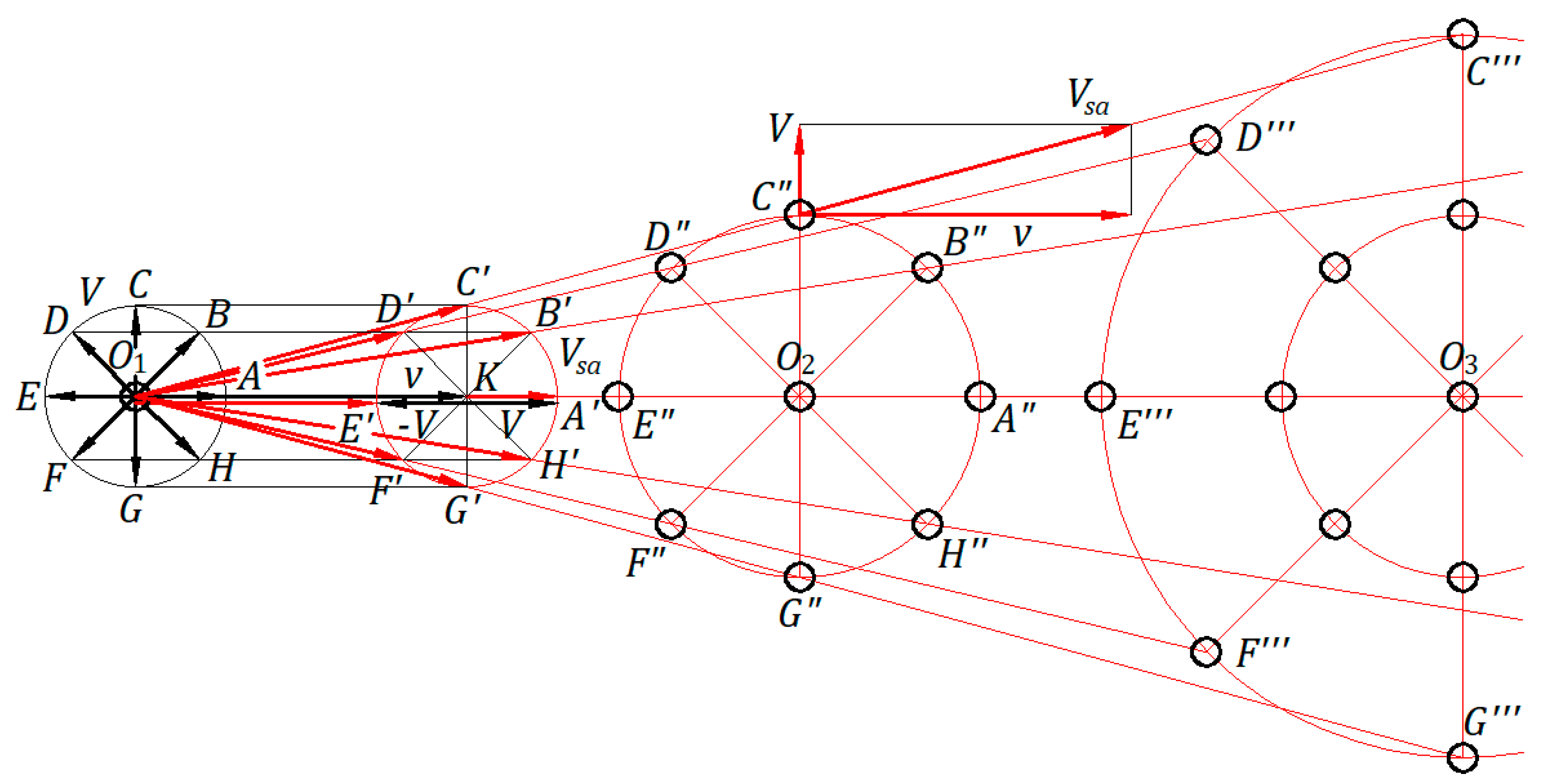

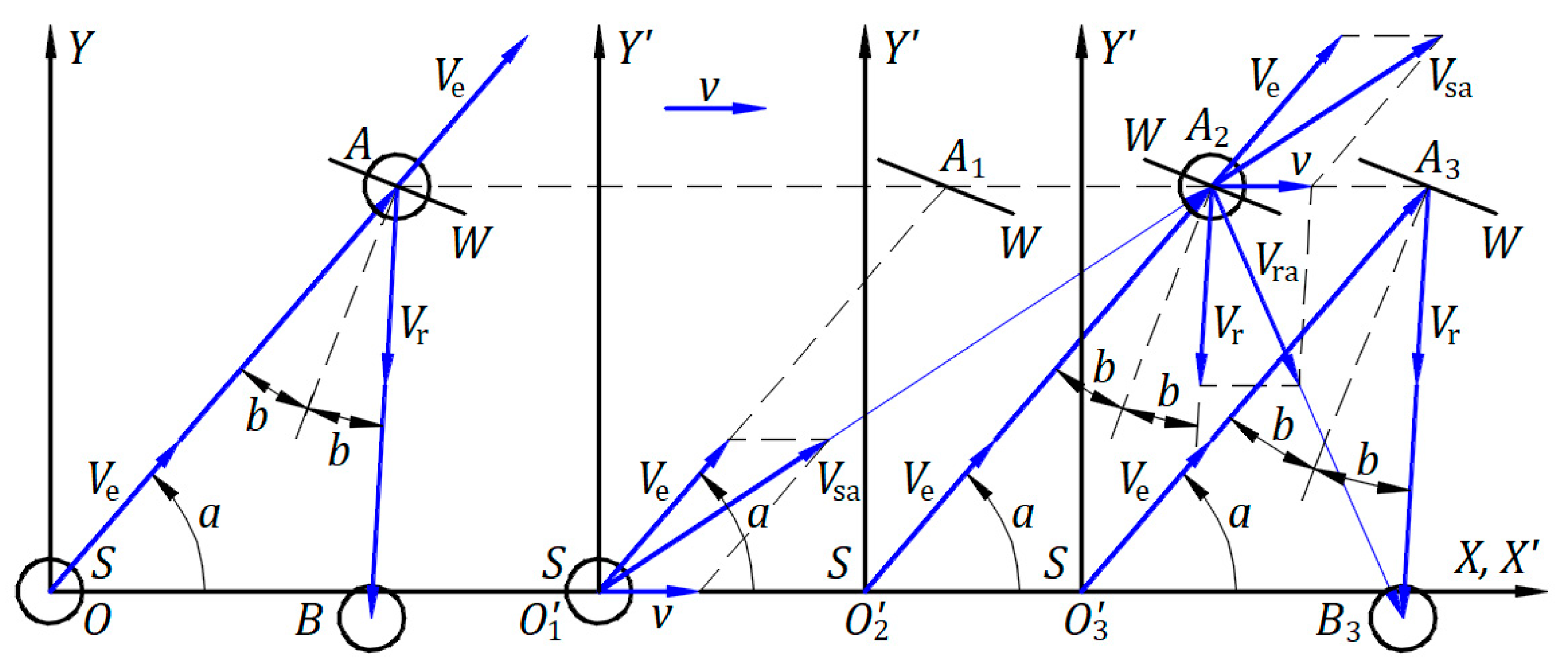

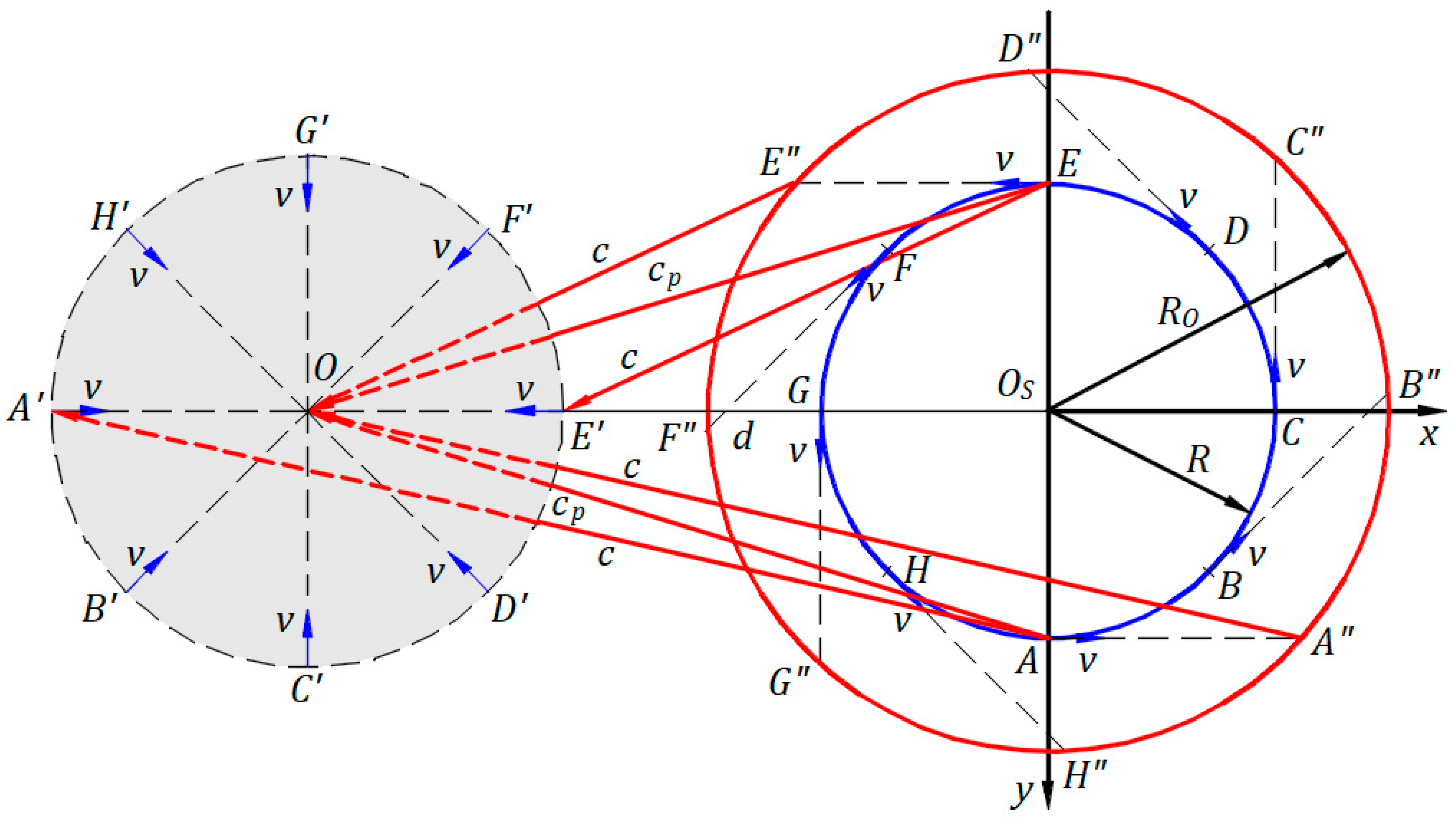

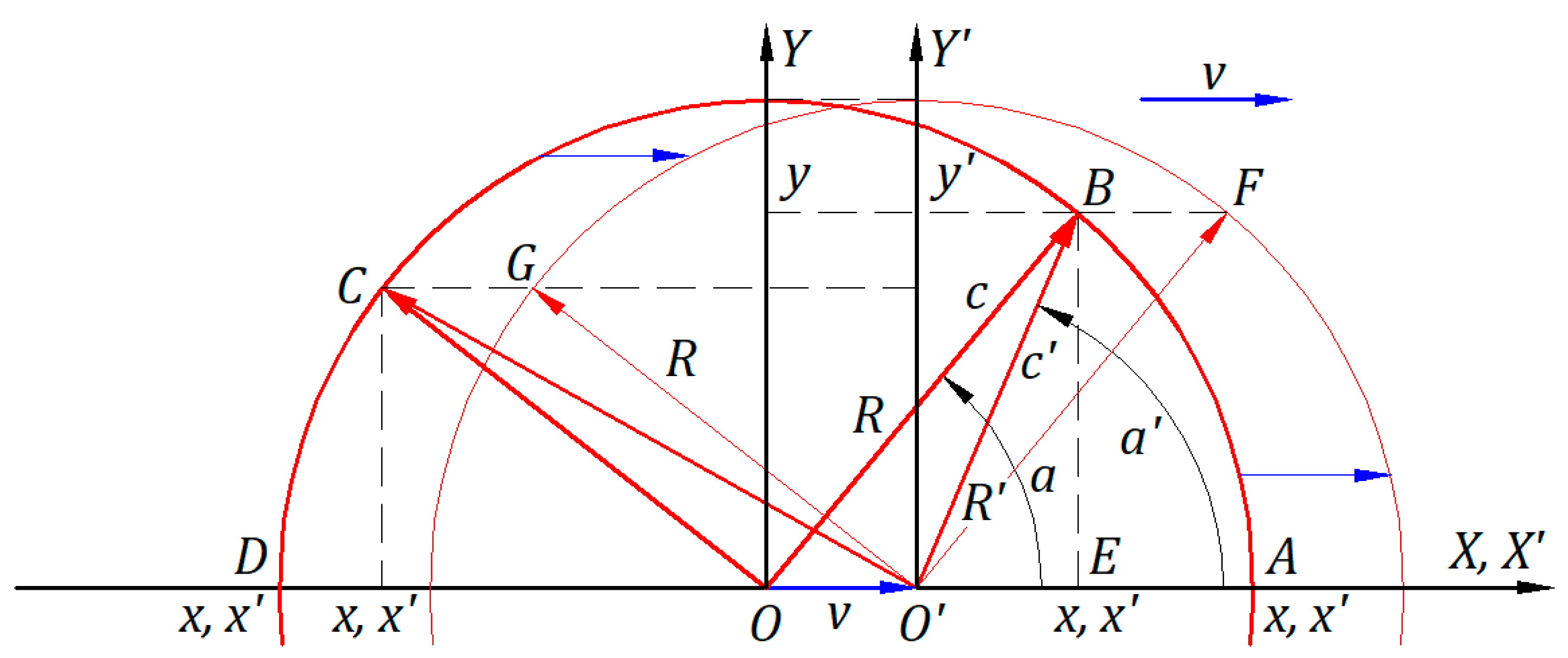

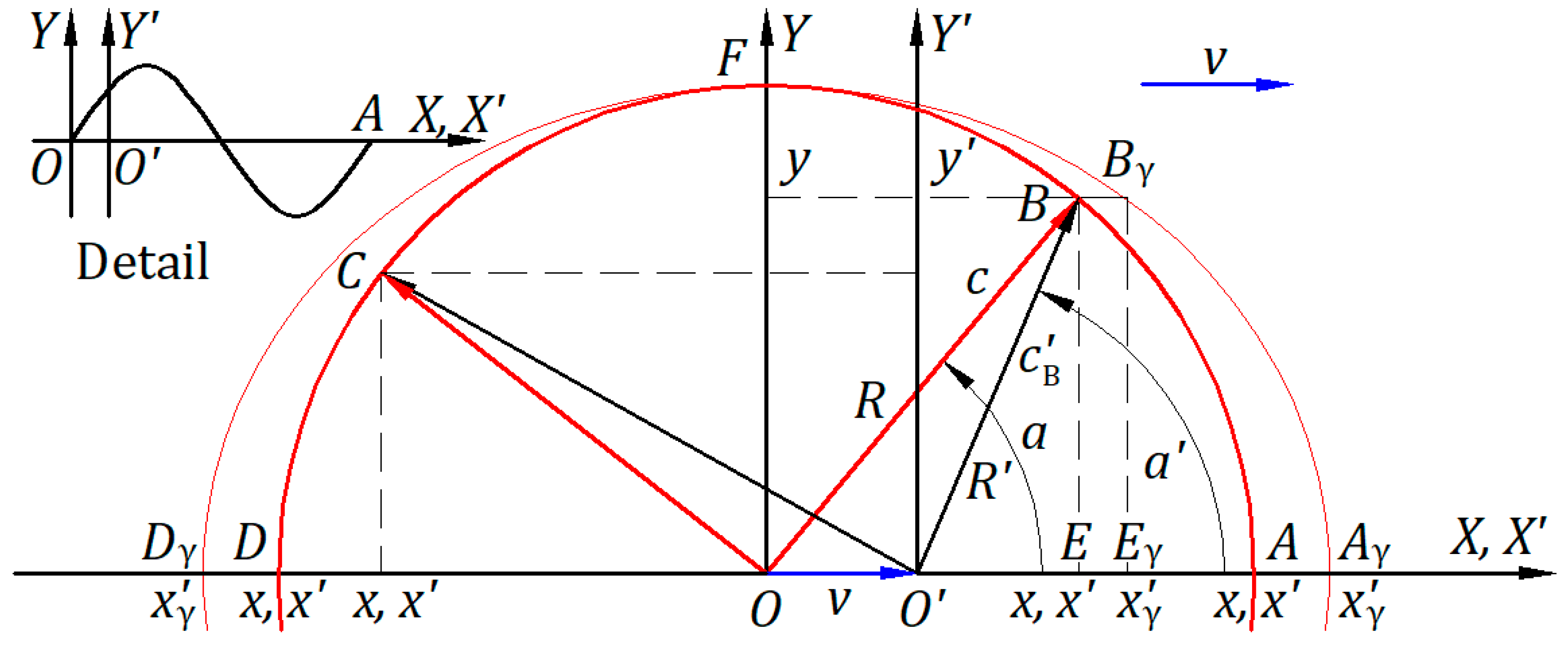

Figure 15 depicts a stationary frame

in which an inertial frame

travels at a velocity

along the

axis, and the planes

and

are common. Origins

and

coincide at the initial instance when a light source belonging to the origin

emits a spherical wavefront. After a time

, the spherical wavefront expands in space with a radius of magnitude

, and the origin

is at a distance

from

. The drawing is at a scale for a time

s.

In the theory of the ether at rest in the absolute frame, the speed of light is the constant

. Observations and Michelson‒Morley’s experiment can be explained if the speed of light is the constant

in inertial frames. With no explanation of the Michelson‒Morley experiment during his time, FitzGerald [

24] wrote the following: “I would suggest that almost the only hypothesis that can reconcile this opposition is that the length of material bodies changes, according to their movement through the ether or across it, by an amount depending on the square of the ratio of their velocity to that of light.”

Lorentz considers the coordinates of the spherical wavefront of light from the stationary frame along the three axes of the inertial frame and applies his transformation only along the axis

. The projection of each coordinate of the spherical wavefront gives in the inertial frame along the axis

a length

measured from

to

. Lorentz’s transformation hypothesizes that light travels each length

at speed

in a time

and consists of four equations that apply to each point of the spherical wavefront as follows:

where

is the Lorentz factor, which is comparable to the square of the velocity

and

ratio, as suggested by FitzGerald.

In

Figure 15, the mechanical equation for the wavefront traveling the path

is

⇒

⇒

⇒

with

. In Lorentz’s transformation, the equation for

is identical to that in mechanics for

; thus, both lengths

have an equal absolute value. If we hypothesize the constancy of light speed, then

from mechanics becomes the speed

in the inertial frame and

. Therefore,

offers

⇒

which is the equation of time in Lorentz’s transformation. We obtained the following set of equations:

Multiplying and with factor we get Lorentz’s transformation. (10)

Substituting at point , is the absolute coordinate in the inertial frame, and is the hypothetical contracted time by given by Lorentz, in which the wavefront travels length at speed . , , and then , which verifies the constancy of light. Because for , the length is longer than , and point shifts to .

Substituting at point , is the absolute coordinate in the inertial frame, and is the hypothetical dilated time by given by Lorentz, in which the wavefront travels length at speed . , , and then , which verifies the constancy of light. Because for , the length is longer than , and point shifts to .

In the relativistic time of Lorentz’s transformation, the speed of light is the constant , and has the same absolute magnitude as in mechanics. Thus, the time contracts or dilates accordingly such that and for each spherical point stay constant, therefore, no length contractions or dilations exist.

The following numerical calculation employs the lengths shown in

Figure 15 which all are of absolute values including the length

offered by Lorentz’s transformation. The speed of light along each length

given by the projection of each wave in any direction on the axis

is constant

according to the relativistic time in Lorentz’s transformation. For an angle

and a time

we can calculate

,

,

,

,

,

, and angle

. Employing relativistic speed

along

,

⇒

. From the geometry of the triangle

with absolute side lengths, the time

the light travels along

must equal the time

the projected light travels

. Therefore, the speed of light

traveling

is

.

Table 1 lists the numerical calculations for the

and

functions of angle

at time

s.

Table 1 confirms that Lorentz's transformation maintains the constancy of the speed of light for the waves in the direction

and the opposite direction. However, the speed of every other wave direction varies converging to infinite. The second postulate asserts the constancy of the speed of light in the inertial frame regardless of its direction; whereas the transformation drastically concludes otherwise.

We can hypothesize that the speed of light along is constant , . In this case, we apply Lorentz’s transformation along as it is used along , at the same time , speed along , and speed along . In this case, the speed along is which when , and points , , and coincide, and for , point is at origin , point coincides with , , and .

The time the light travels the path at speed is , and the time the light travels path at speed is . The time the light travels the path at speed can be calculated with Lorentz’s equation where and are unchanged but and is ; therefore becomes . Times and calculate considering the light passes as absolute values yield the same time s and, applying Lorentz’s equation, time gives s. The time difference between and does not support the constancy of light along too.

Because for , the length is longer than , and points and shift to and , correspondingly. For angle , and . Thus, Lorentz’s transformation creates a duplication as an ellipsoid instead of a sphere. The time gives the time s, which confirm the hypothesis the speed of light is incorrect.

This case confirms the constancy of the speed of light for the waves in the direction and the opposite direction as Lorentz’s transformation does. However, the speed of every other wave direction varies but without converging to infinite.

4.4. Discussions

1. Is it rational to observe the circular wavefront with its center at the origin and to keep the speed of light constant along the axis in both directions or to have a theory that may or may not explain experiments and observations without understanding their physics phenomena? Furthermore, is it reasonable to force the circular wavefront and its observations to follow the same physical laws as those in the stationary frame? Einstein chose this approach, leading to an irrational world. Unlike special relativity, Newtonian laws present phenomena as they are, rationally understood by themselves, and not accepted by observations, hypotheses, or postulates.

2. What natural phenomena can transform each wave from a stationary frame into its unique form, as required by Lorentz’s transformation and shown in

Figure 15? Other mathematical transformations can be considered, e.g., ignoring the Lorentz factor

as discussed in Subsection 4.3, allowing the speed of light to be constant along each wave in the inertial frame, or having the time a constant and the speed of light variable according to its direction. [

25] Could there be a phenomenon for each of these hypothetical mathematical transformations to explain the Michelson‒Morley experiment? If so, which one would be correct? If we try these transformations, we obtain a theory with irrational conclusions like that for special relativity.

3. A ruler identical to that in the stationary frame is required to measure the lengths involved in phenomena that belong to the inertial frame. We also must have two rulers with different scales required by Lorentz's transformation to measure the lengths along according to positive or negative, or considering other directions. The use of multiple rulers is unacceptable. The same conclusion applies to multiple synchronized clocks.

4. Suppose that the inertial frame also has a source at its origin. When the origins coincide, each source emits a circular wavefront of light. Whether or not we consider the factor , imagine the confusion in the inertial frames having two wavefronts, one of its own and another observed from the stationary frame.

5. When we observe a star that involves astronomical distances, as seen in the example in Subsection 3.5.4, we observe it in an enlarged orbit without irregularities; however, our observation does not change the actual orbit. There is no need to mention other observations close to our eyes that we know are not factual. These observations can be explained by laws of physics. However, we must distinguish between actual phenomena and their local observation. Therefore, we cannot rely solely on observations. Special relativity focuses on observations but makes no distinction between the emitted and propagated velocities of waves' wavefronts. It fails to consider that our eyes perceive only the direction of waves emitted by a source and reflected by a mirror, not the direction of wave propagation.

6.

Figure 15 illustrates a case in which origins

and

coincide at the initial instance. However, origin

may be far away from

when the source emits a spherical wavefront at an initial instance. In this case, there is an interval of time when the circular wavefront does not include the origin

, a time when the circular wavefront is at the origin

, and an interval of time converging to infinite when the circular wavefront includes the origin

. How is the circular wavefront observed at

at these different times? Do we force the coordinates of the circular wavefront to be observed according to the Lorentz transformation with its center at

at any time?

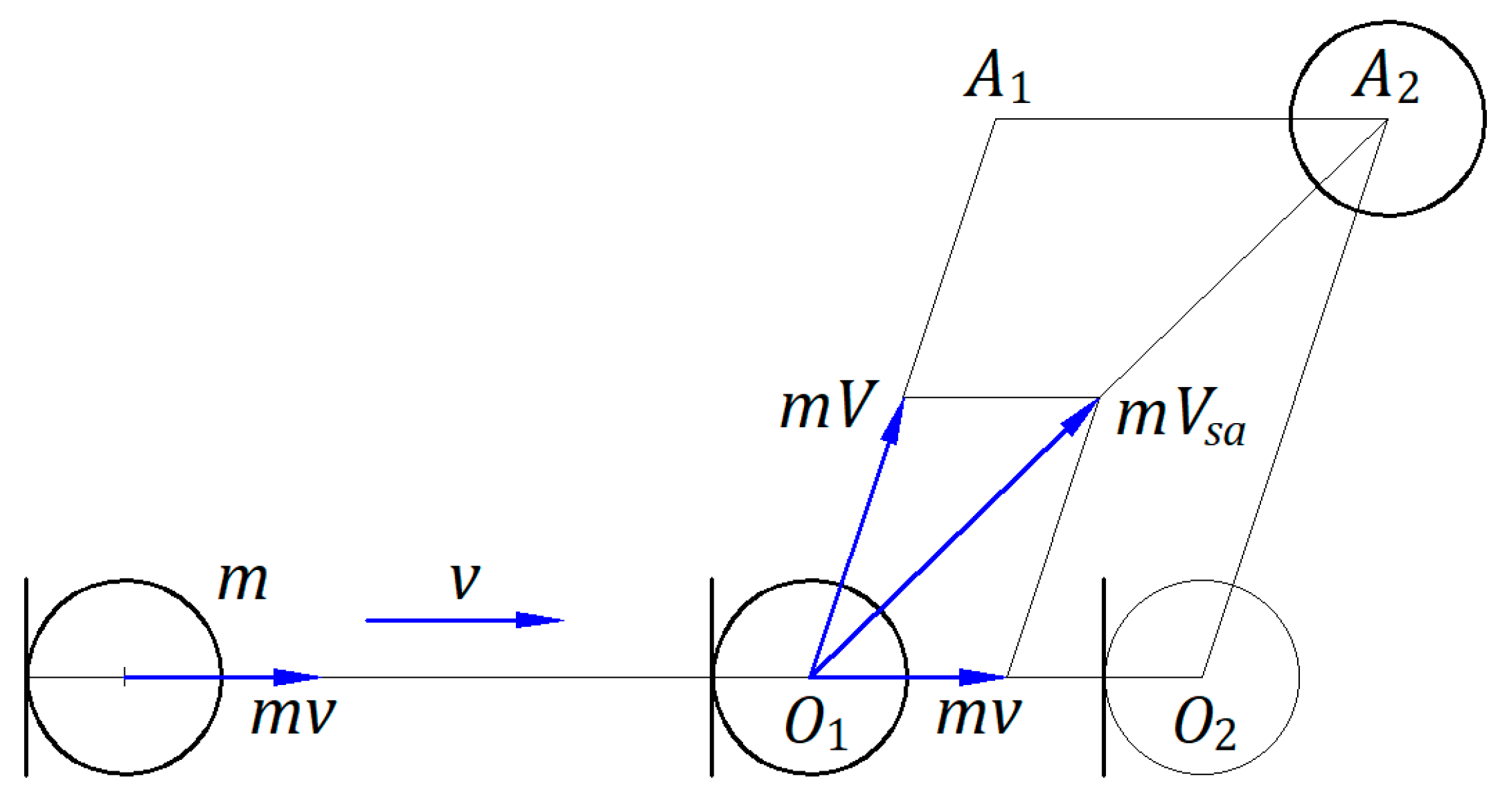

7. Suppose that a source of balls in the stationary frame emits balls of equal mass in all directions at a speed

that is higher than the speed of the inertial frame

. As for light, the coordinates of the spherical ball front in the inertial frame at a time

are as in

Figure 15. Mechanics does not and cannot force the coordinates of the circular ball front to have its center at

; in Einstein’s words, “the equations of mechanics do not hold good” in this case. However, special relativity does not respect Suggestion 2 of Subsection 4.1.

8. The first postulate indicates that the physical systems in the stationary frame change when they are transformed/duplicated into the inertial frame. The physical system mentioned in the first postulate has a source and light rays that create a circular wavefront. However, other systems may contain bodies and living beings involved in a phenomenon. Considering that the origin of inertial frames is relative, their origins can be at the origin of the stationary frame when the source emits a spherical wavefront of light. We can imagine what the physical systems’ duplication from a stationary frame in all other inertial frames means. Moreover, each inertial frame may be arbitrarily stationary; therefore, a phenomenon from another stationary frame can be duplicated in all other inertial frames. Do all these duplications occur just by choosing a stationary frame? All these duplications are irrational and are not observed in the universe or at a local scale.

9. In a stationary frame, as shown in

Figure 15, the origin

of the inertial frame may travel through a few consecutive points along the

axis. Suppose that a phenomenon arises in the stationary frame when the origin

coincides with each consecutive point. Each of these phenomena is thus transformed at the origin

. Imagine all of these phenomena involving bodies and living beings at

.