1. Introduction

This paper examines the model of a timeless primordial state (PS) of pure space preceding everything, the emergence of time from it, and the subsequent evolution of space-time. It results from a series of earlier investigations ([

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]) each of which has provided ingredients for a new overall concept. Because it’s often about subtleties, and in order to achieve a largely self-contained presentation, some of our earlier calculations, that are important for this paper, are reproduced here (mostly in the Appendix) in compact form and adapted to the present needs. This is important also for the reason that from them partly other and partly new conclusions are drawn. Unlike the earlier studies, which dealt with the origin of

, space expansion, DE, and a multiverse, this paper focuses on the origin and structure of space and time. Essential concepts on which it is based are conveyed below.

1. Already since early antiquity there has been felt a need for putting an end to the endless chain of cause and effect that makes each cause the effect of a preceding cause. For this, Aristotle proposed the concept of the

unmoved mover [

6], a kind of primal force which gave the impetus for all later movements in the universe without having been moved itself. In Ref. [

1], an equilibrium between attractive matter and a repulsive cosmological constant or a scalar field was derived and introduced as initial state of

. Because this equilibrium is unstable, the transition to a temporal evolution is triggered by disturbances. This scenario already exhibits almost all the characteristics of an unmoved mover. (The only exception could be dynamic processes in matter on microscopic scales.)

In this paper, the PS is derived by applying a WDW equation to a simple minisuperspace model. It is timeless, has only 3 spatial dimensions

1 and corresponds one hundred percent to the concept of the unmoved mover due to its complete timelessness. It turns out particularly important to formulate the WDW equation not in terms of the expansion parameter

a, but of the corresponding volume

, because this reveals structures which can be interpreted as space quanta. This has already been observed in Ref. [

5], where the case of a PS consisting of very many space quanta was formulated as a problem. Its elaboration constitutes the content of this paper.

2. Another ingredient is the assumption that the space is uniformly curved and expands, which also pertains to concepts of e.g. Vilenkin [

7,

8], Linde [

9], Hartle and Hawking [

10] and Ref. [

11]. An important reason for this is that only such a space can have come into existence at some finite time in the past, while a Euclidean space has always existed, even if it expands. Our decision for a model of this kind is also motivated by the fact that everything observed in

and also

itself had a beginning.

2012 it was shown by a

global transformation of expanding space solutions of an FL equation, that the space expansion of

can also be viewed as an explosion in a non-expanding and almost Euclidean space [

2], in contrast to the general view since around 2000 at the latest. After this interpretation was initially received with skepticism, it was later devaluated as a matter of course, arguing that General Relativity (GR) would allow you to employ any coordinate system of your choice [

12]. However, this argument falls short as shown by the example of a coordinate system which rigidly rotates in conformity with the earth. Already from 27.6 times the distance between earth and sun the rotation speed exceeds the speed of light, so this coordinate system is unsuitable for describing a whole universe. Another example is the coordinate system commonly used (and also employed by us) for a uniformly curved, expanding space. This space expansion cannot be transformed away globally, because the matter flowing away from the explosion site in all directions would flow back after reaching the antipodean position and collide with the flow towards the latter.

2 This means that it constitutes a

generic expansion, a property that will turn out to be essential for our model.

3. In our present model, the space is uniformly filled with DE which is needed for space expansion and information storage. It thus fulfills important purposes, which have already been discussed more detailed in previous work [

3,

4,

5]. In particular, this provides the reason why DE is even present in

, observed as a gap filler for a significant energy contribution missing in the energy balance without it, and by an acceleration of

’s expansion. DE can thus be considered as a fingerprint of the space containing

. In short

space-time is tied to the presence of DE and would not even exist without it, i.e. DE is space energy. As in the above papers, we assume that in the PS it is due to a cosmological constant

and has a huge mass density

close to the Planck density.

An independent argument for our assumptions about DE is the following. Space is so slightly curved and therefore so extended that it reaches far beyond the boundaries of . According to current knowledge, within the DE is present and evenly distributed everywhere, also between the galaxies. It would be very strange if this distribution would stop at the boundary of . This consideration also led us to assume that DE is the substrate of space and gives it gravity.

4. Physics describes the elements of matter through particles and fields and their temporal behavior through interactions between them. The description of the elements comprises properties that determine which of them interact, how strong the interactions can be and what type they are. However, this description is rather simple, using just a few parameters such as rest mass, charge, spin, etc. for particles, and scalars, vectors, tensors, etc. for fields. This is by far not sufficient to determine the temporal course of interactions which is rather regulated by much more complex laws of nature that the matter elements must obey. As things stand today, this is done in a ghostly way as if following a categorical imperative [

13,

14]. A more scientific approach must take into account that material elements like an electron have no receiver, no brain and no power source to perceive instructions and convert them into prescribed actions.

Perhaps the most important ingredient of this work is a proposal how the obedience to all the laws of nature can be integrated into the rule book of physical description in a manageable and, as far as possible, minimally invasive way, presented for the first time in Ref. [

4] and elaborated in Refs. [

4,

5]. The proposal was inspired by biology, where the molecules forming an animal or a plant are assigned their tasks by the genetic code written down in the DNA. Accordingly, we assume that all information about the laws of nature is encoded into submicroscopic structures of space granules (quanta) forming the timeless PS. Presumably, this will not take the form we know, but rather the form of instructions on law-conforming actions. It follows that the volume of the PS must be very large to contain the huge amount of the pertinent information. This leads to striking differences in the subsequent ES compared to the models studied in Ref. [

5].

The temporal evolution following the timeless PS consists in a generic space expansion as described above (see 2.). That this is not an auxiliary mathematical construct but a real physical process has a decisive meaning for our model. Unrestrained, the huge cosmological constant would cause a strongly accelerated space expansion and thus ever faster create new space elements, to which the information about the laws of nature must be transferred from the already existing ones. This requires a fixed amount of time, while the available time becomes increasingly scarce as the rate of expansion increases. Obviously, this hinders the expansion, which we take into account in a lump sum by subtracting from the expansion acceleration a "friction force" proportional to the expansion velocity, as in our earlier work. It was left open there, how the information is stored. In this regard the present study makes a slightly more concrete proposal, which has similarities to how space quanta are arrived at in LQG, using the group properties of polyhedra and a WDW equation.

3. Primordial State

Because of its extremely high mass density

close or equal to the Planck value

, the PS of the examined space-time system must be described by a general relativistic quantum theory, in our case a WDW equation. From this follows that

must be time-independent (see after Eq. (

A3) of

Appendix A) so that Eq. (

13) reads

In

Appendix A, the WDW equation (

A4) with

is derived from this in terms of the dimensional quantity

V, and the substitution

in it yields the WDW equation (

A5) with

,

As in ordinary quantum mechanics, we interpret

(

since

is real) as a probability density, i.e.

It cannot be localized at spots of one specific space, but it rather is a density with respect to contiguous volumes of independent spaces in the (virtual) ensemble (Hilbert space) of all theoretically possible spaces exhibiting the properties specified at the beginning of

Section 2.2. (We come back to this interpretation in more detail in

Section 5.2.2.) In

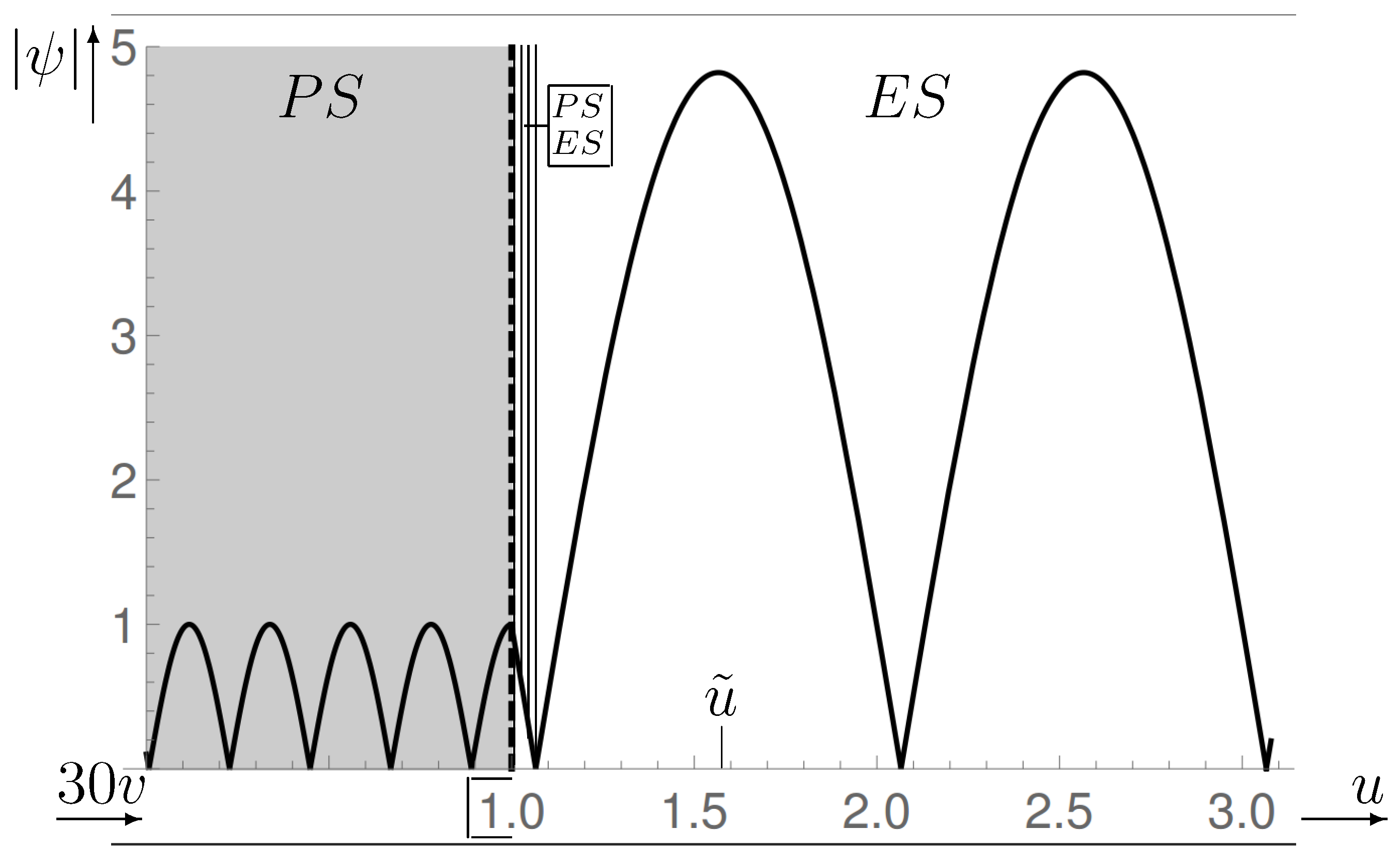

Figure 2 the probability density

is plotted for two solutions

of Eq. (

17) to small initial values

and

specified later in more detail. It has zeros at essentially equidistant consecutive points and nearly equal maxima close to the centers

of neighboring zeros. The fact that

has practically the same shape in essentially all intervals bounded by adjacent zeros constitutes a crucial point of our model: we consider

in each of them as a separate quantum state in which the middle value

has the highest and each edge point has zero probability. From this follows that

v can only assume discrete values differing on average by

, and from this it can be concluded that each of these discrete volumes consists of space quanta of average size

. In principle, values from the interval

would be possible for them. In order not to unnecessarily complicate our calculations, we use the most probable value

in the further course. (It can be guessed, however, that refining our model – as, for example, towards the end of

Section 3.1.1 – would yield sets of space quanta with slightly different sizes.)

As explained in paragraph 2. of the Introduction, the volume of the PS must be extremely large for being able to store the information about all laws of nature. In Eq. (

17) the second term in parentheses can be neglected against the first for

according to Eq. (

33a), which is the case for almost all

v, given the large size of the primordial volume we find out later. Under these circumstances, Eq. (

17) simplifies to

Of the two independent solutions, a suitable one is

where for the amplitude we could arbitrarily chose the value 1, because every multiple of a solution is also a solution. The probability density

has the period

, from which with

it follows, that

with

are the most probable volumes that the PS can assume. (For the numerical values the later result (

33a) for

was used.) The total volume of the PS is

where

has yet to be determined. From this it can be concluded that the total volume is composed of elementary volumes whose average and also most probable size is

(or

in dimensionless variables). We assume that

or

resp. is a most probable volume between two adjacent zeros of

from Eq. (

20) too. We set the end point

of the PS so that

For the sake of simplicity, we address

or

resp. as the uniform volume of

space quanta in the further course. This simplification does not matter for all applications in this study, because – except for a rough determination of the primordial mass density

in the next section – we always have to deal with very large numbers of space quanta, for which only their average volume matters. (This is due to the fact, that differences in size and probability, which we are actually dealing with, cancel each other out in the sum.) However, at the end of

Section 3.1.1 we consider – if only qualitatively – the possibility of distinguishable space quanta that could turn out useful for the information storage so important for our model.

3 Numerical values for

and the corresponding extent of the PS,

are derived in

Section 5.2.1.

proves so large that it consists of a huge number

of space quanta.

3.1. Determination of the Primordial Mass Density

From Eqs. (

21) results with the definition of

in Eq. (

10c)

i.e. the size of the space quanta

is a function of the mass density

of the DE in the PS and is not fixed by the WDW quantization. However, by comparing solutions of Eq. (

17) for different values

we will come to a choice that is acceptable although not stringent. It appears sensible to limit our search to the range where quantum and GR phenomena are equally important, from which it follows that

must be located in the region of

. Accordingly, we must expect the space quanta in the PS to be tiny black holes. In the next section, we want to find out from which point on this is roughly the case. For this, we content ourselves with a simple calculation, ignoring both quantum and GR effects. We then numerically determine the solution of Eq. (

17) for different values of

or

resp. and decide which one seems most suitable for our purposes. The preceding rough calculation will help us to get a particularly illustrative picture of the space quanta.

3.1.1. Simple Black Hole Model

Not only for the simple model now considered, but in general we assume that the whole mass of space is contained within the space quanta .

In the following more detailed calculations we restrict ourselves to space quanta forming non-rotating black holes and consider the entry point of black holes, at which the radius of a sphere of homogeneous mass density (

, see Eq. (

30)) just coincides with the Schwarzschild radius

where

is a constant yet to be determined. From this follows with Eqs. (

1) and (

2)

and with this the volume of the considered Schwarzschild sphere becomes

We assume that the Schwarzschild spheres of our black hole quanta do not penetrate each other, but touch in points and arrange themselves in the closest packing possible, the one claiming the smallest total volume. According to Ref. [

15], this means that the individual spheres occupy the part

of the the quantum volume

from Eq. (

21), found without assumptions about the shape. Substituting the non-numerical part of Eq. (

21b) and Eq. (

27) into Eq. (

28) and solving for

yields

Under the natural assumption that there is only one black hole in each space quantum of volume

, the primordial mass density is

Inserting into this

obtained by resolution from Eq. (

10c),

from Eqs. (

21),

from Eq. (

26), and

from Eq. (

3), we obtain

and substituting this into Eq. (

29) finally yields

With this, we get from Eq. (

31) and Eq. (

10c)

The fact that

is only about 1 percent of

indicates that our classical calculation for the mini black holes is not too wide of the mark. A numerical solution of Eq. (

17) for this

is shown (

Figure 2) and discussed in the next section.

Besides the spherical black holes considered so far there are also rotating black holes. This opens the possibility to include space quanta with spin, that can have slightly different volumes (which is useful because our model allows for space quanta with different volumes). For massive objects with spin the quantum rules are well known and could be used for a different kind of loop quantum gravity (LQG) in a similar way as the polyhedra for the usual LQG [

16,

17]. In particular, space quanta with equal spin but different spin orientations could provide an alphabet for information storage.

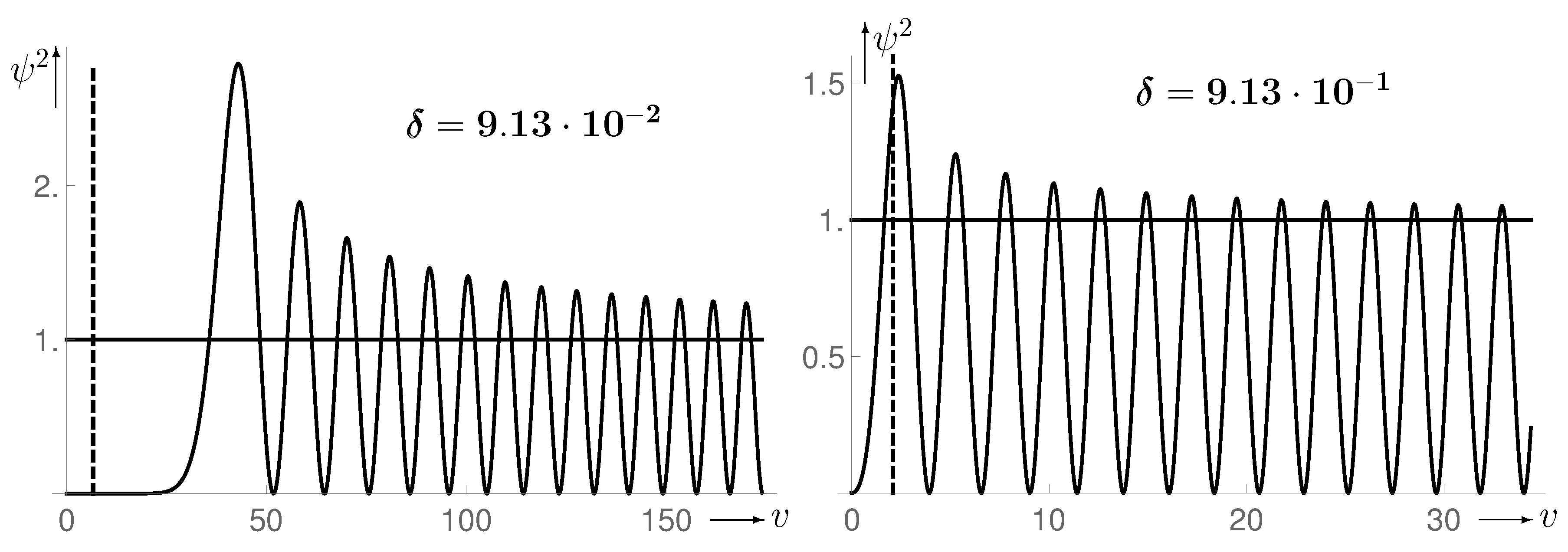

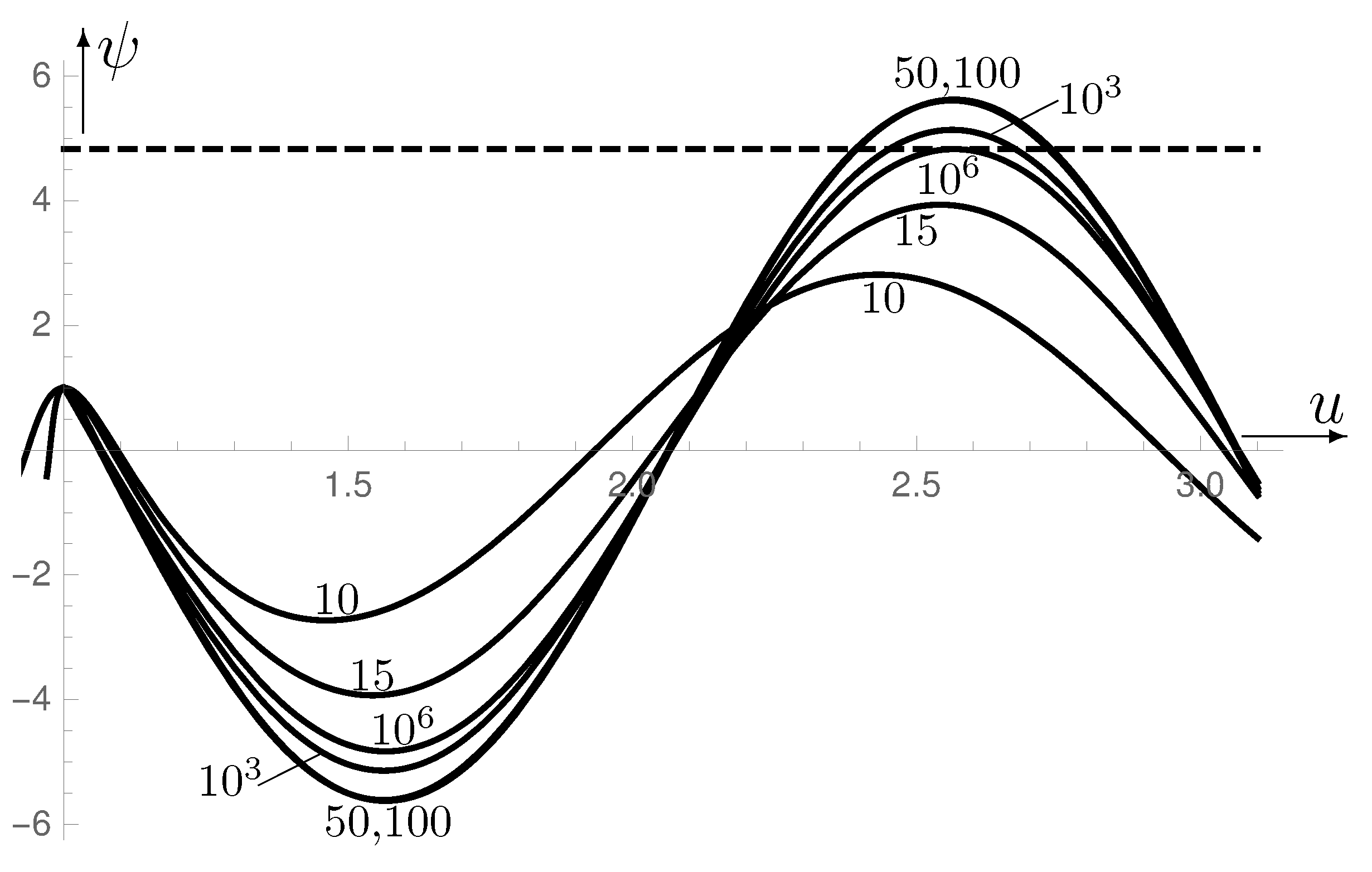

3.1.2. Solutions of the WDW Equation for Different Values

When solving Eq. (

17) numerically, we want to exclude the case of a space with vanishing volume and would therefore prefer initial conditions such that

and

vanish for

. However, instead of zero, we have to take a very small value for

v (we chose

) in order to avoid

becoming singular.

must also assume a value

in order not to get the solution

. Furthermore, we want to obtain solution (

20) for large values of

v. For this purpose, the initial value of

was chosen so that for large

v (about 20 times the largest

v in each picture of

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) the amplitude of

is 1.

In

Figure 2, the left picture shows the solution for

or

obtained in Eq. (

32) of the last section. The dashed vertical line marks the volume

, which would result if the space consisting of a single space quantum had the volume

of space quanta derived for large

v. The horizontal line

represents the amplitude of the asymptotic solution (

20). For larger

v there is already good agreement. That there appear increasing deviations with decreasing

v is due to the fact that simultaneously the space curvature becomes more and more noticeable. According to our model the PS does not arise from a growth process, but by definition consists of a huge number of space quanta. This means that the differently shaped states of small

v do not appear at all in a PS with many states. (It should be remembered that the solutions do not represent one, but many spaces of different sizes.) Rather, we can assume that all space quanta have the same volume

from Eq. (

21) that applies to very large

v values.

Even though we have seen that the deviations from the asymptotic behavior that occur at small

v do not play a role for a large PS, one will prefer if the space quanta in small spaces are approximately the same as in large spaces. This certainly does not apply to the case shown on the left in

Figure 2 due to the large gap of about

between

and the

v belonging to the first maximum of

. For this reason, we have examined a number of other cases which show that the situation improves with increasing

or

resp. The right picture in

Figure 2 shows the situation for ten times the value of

as in the left picture. The first quantum state still has slightly more than twice the volume

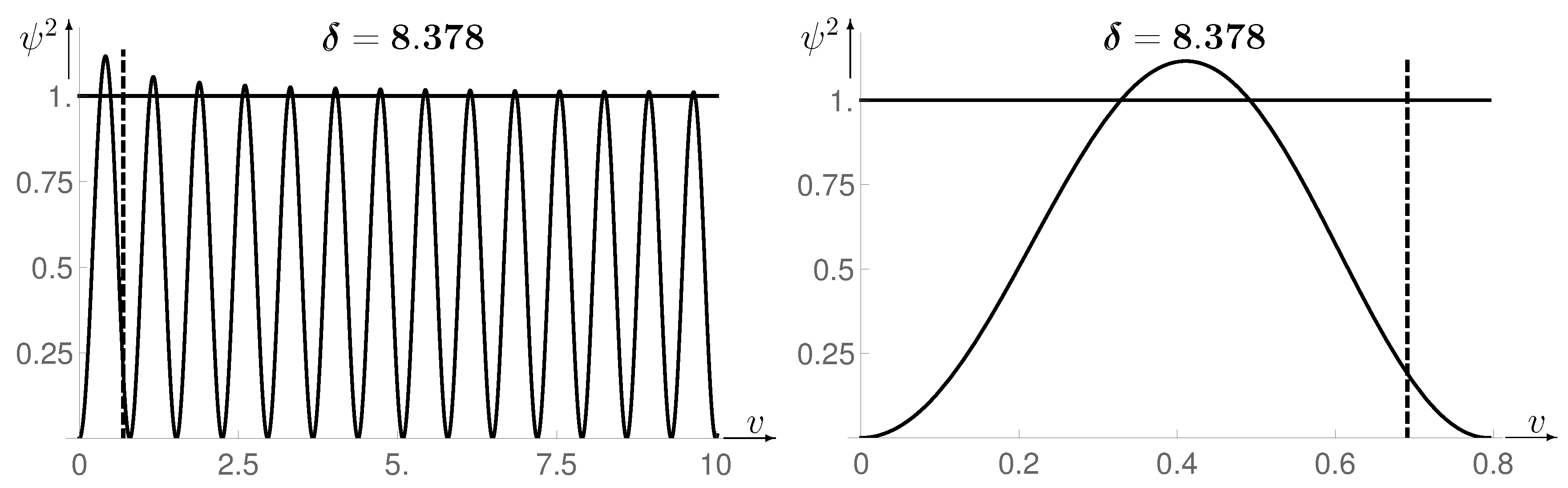

. In

Figure 3,

is again magnified by almost a factor of 10 to

. This situation is already almost optimal, and it has turned out that further enlargements (up to

) do not result in a complete agreement with

. We have therefore decided on the case

for all further calculations, which indeed represents a compromise. Since the value

is almost 100 times larger than the value at which, according to our rough calculation in

Section 3.1.1, the space quanta just become black holes, we can assume with considerable certainty that the space quanta, which we ended up with, are indeed black holes. According to classical GR it follows from this that they are mass points. Nevertheless, each of them requires the finite volume

. This does not imply that they have a structure, but simply means that they must be spaced apart according to their volumes. However, in correspondence to the classical rotation of black holes, they can still have a spin, which is relatively easy to handle quantum mechanically.

In

Table 1 the values of

,

and

are listed for the solutions represented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 and for volume quanta obtained in the LQG [

16]. The value of

corresponding to the latter is calculated with Eq. (

25).

Given the uncertainties associated with each of the underlying assumptions, the results reported in the Table are fairly consistent.

4. Evolution of Space-Time, Classic Treatment

When calculating classical quantities, we can leave it with the usual dependence on x instead of v, because wherever necessary we can use to switch to the v-dependent representation, without changing anything conceptually as with the derivation of a WDW equation.

The classical evolution of space-time can be completely described by the solution of Eq. (

10) to the boundary conditions (

A7) and (

A8), according to Eq. (

A6) with Eqs. (

A9) of

Appendix B given by

After

Section 2.2, at this the FL equation (

9) is already fully taken into account. With

,

according to Eq. (

33), and in anticipation of the later results (

51),

, and (

86),

, instead of Eq. (

34) we can use with extremely little error the much simpler representation

where the upper sign, −, holds for

. The comparison of the two bracketed terms yields

from which follows that due to the extreme smallness of

we can write with extremely high accuracy

4.1. Determination of and

Although Eq. (

9) must no longer be taken into account, we can still use it to calculate

or

resp., i.e.

If we were to use Eq. (

36) for calculating

, according to Eqs. (

9b) and (

37) the initial value of

in the ES would be

which contradicts Eqs. (

11a) and (

33b). In order to remove this discrepancy, for calculating

we must instead employ Eq. (

35) to get

With Eq. (

36) and the (very precise) approximation

follows from this

so we finally get

With this result the discrepancy disappears, because for

, neglecting

and

versus

(based on Eqs. (

33a), (

51) and Eq. (

86b)), we get

and from Eqs. (

9b) and (

10c)

as required. For sufficiently large values of

, the second bracket term in Eq. (

40) becomes negligible versus

, and we obtain

To find out more precisely when this is the case, we determine when

or

holds. This is the case for

with

where Eqs. (

1), (

4), (

33) and (

51) were used for the numerical values. After just

Planck times or

seconds resp., i.e. practically instantaneously

decreases from the huge value

to the much smaller value

(coming about due to

). This density decrease without equal represents a practically instantaneous and exorbitantly huge crash. Detailed reasons for its occurrence are discussed further down. It is particularly noteworthy that due to

the collapse of the density leads almost exactly towards the density

that results from the FL equation (

9) for the equilibrium

at

. The solution belonging to

(lower sign) even leads exactly to this point, because Eq. (

38) results in

In relation to our model, however, this is not an equilibrium, because from Eq. (

10) follows

for

. Because the solutions for both signs behave essentially the same, we further on restrict ourselves to that with the upper sign, i.e.

.

We can now use Eqs. (

9b) and (

41) to calculate

by inserting for

today’s value

and resolving for

,

where

is the present value of

. Since in

, DE contributes 68.3 percent of the total mass density and the latter equals the critical density

with

present Hubble parameter and

present Hubble time, we have

Here,

was plugged in, a value that is slightly higher than the age of

, but slightly below the last values obtained from measurements for

. (This value was chosen because it yields a particularly handy result for

.) The value of

can be freely specified, but only above

due to Eq. (

46). For illustration we relate it to the radius

(slightly below present the Hubble radius

) by setting

or

Inserting all this into Eq. (

46), we get with

from which the condition

results for obtaining real values of

. For the space curvature to be below the maximum value compatible with measurements, according to Ref. [

18] the condition

must be satisfied. In

Appendix D it is shown, that in terms of our parameters this amounts to

. In

, the DE is usually attributed to a cosmological constant. Since the DE of our model fills up the entire space and thus also that of

, it should share this attribute, so we assume that at least during

’s present lifetime the density

of the DE is largely constant. For this reason we choose

still well above 14.5. The value

seems sufficient to us and shall serve as a reference value. With this, due to

, we get from Eq. (

49) with very little error

With the specification of

now also

can be calculated. According to Eqs. (

9b), (

36) and (

41) the further evolution of the density after its crash (i.e. for

) is given by

Characteristic values, calculated with this, Eqs. (

33), (

48), (

86), (

89) and

are given in

Table 2.

We are additionally interested in how the expansion rate

changes over time

t. For this we first calculate

and

for some times

. From Eqs. (

36), (

39), (

51) and (

86) we get

and

where the relation

, used for defining

, was employed to calculate

. For

Eq. (

36) can be used for calculating

, and together with the above relationships, Eq. (

59a), and

for

, we get the values given in

Table 3.

The values

corresponding to

are obtained from

so simply by multiplying

by the speed of light.

According to Eq. (

54),

Table 2 and

Table 3, we have

(the = signs holding with high precision but not exactly), and due to

this state can be considered as start of the space expansion.

4.2. Causes of the Density Crash and Disequilibrium of the Initial ES

The causes of the initial density crash can best be understood on the basis of Eq. (

37). The values of the quantities on the right before and after the crash are given in Eqs. (

53) and (

54) resp.

must even be larger than the already rather large extent

of the PS (consisting of very many space quanta according to Eq. (

97)) in order that

can assume the high primordial value

. (If it consisted of only one or a few space quanta,

would be almost zero, and then the term

in Eq. (

37) would provide the required high density.) From Eqs. (

53) and (

54) follows that essentially

whereas

, i.e.

changes virtually not at all during the crash, while

changes by almost 62 orders of magnitude. In short, the huge extent of the PS in combination with the large initial value of

requires a large initial value of

(see Eq. (

9a)), but both are pushed down nearly instantaneously by many orders of magnitude,

by 42 (see

Table 2) and

by almost 62 (see

Table 3).

The reason for the latter arises from Eqs. (

10b) and (

A6b). Solving the latter with respect to

and taking advantage of the smallness of gamma we obtain

The high value of this friction coefficient combined with the high velocity

leads to the extreme friction force

against which the force

can easily be neglected. Eq. (

10) thus results in

The extremely fast change of

at

leads there as expected to an extreme curvature of

which looks like a kink (see Figure 5).

The extremely high initial velocity in the initial state of the ES means that the space is in an extreme disequilibrium. Obviously, this affects the density much worse than an instability, where first a velocity or must gradually be built up. Now, from a classical point of view, the initial ES is the same as the PS, and one might assume that the latter is also in a disequilibrium and therefore decays. In the PS, however, time does not even exist, and hence the question of equilibrium or disequilibrium is irrelevant. Even so, we will see later that the density crash, initiated by the emergence of time, affects the state of the ES in such a way that an increased probability for the quantum mechanical transition from the PS to the ES comes about.

4.3. Age of Space-Time and Constancy of during U’s Lifetime

To determine the age of space-time, we first obtain from Eq. (

36)

With this and Eqs. (

1), (

48) and (

86) we get for the present age of space-time

For the reference value

follows from this

where

is the age of

.

Now we pursue the question of how it is about the required constancy of

during the lifetime of

. For this, using

we first go in Eq. (

36) from

to a larger time scale in which the age of

becomes

. In this way we obtain from Eqs. (

9b) and (

41) with Eq. (

36)

where for the numerical evaluation Eqs. (

51), (

59)–(

61) and (

86b) were used. If future measurements should show that the

per mil decrease in

found herewith is too much (or too little), our reference value of

could accordingly be adapted.

4.3.1. Universality of t, Irreversibility and Causal Connection

As in the theory of U’s expansion, the time of our model is a measure of change. The mass density

of the DE is a monotonically decreasing function of

t and thus provides the changes necessary to define a time. From the time

after the end of the density crash on,

or

resp. is given by Eqs. (

9b) and (

41). Substituting

from Eq. (

36) and solving for

yields with Eqs. (

4) and (

9b)

is distinguished by the fact that it can be understood as a universal time, which can even be applied to different parallel universes. It is related to the coordinate system used in our model and can physically be characterized by the fact that in it, the DE density has the same value everywhere at any fixed time

t.

Due to the friction term in Eq. (

7), the passage of time becomes irreversible, time is given an arrow in the forward direction. However, there is no major difference to the course of time in a universe described by reversible equations, which in many models also runs just in one direction without reversing. The only difference is that in our model, there is no solution traversing the same states backwards in time. Further below in

Section 6.2.1, we still take a closer look at the problem of irreversibility.

Table 3 shows that the present expansion velocity of space is

times the velocity of light. This makes it interesting to look at the observation horizon of space, given by

What is of most interest here is its relationship to the radial distance

which leads from a starting point to its antipode. For calculating the ratio

we use

,

,

and

(according to Eqs. (

51) and (

59)) and obtain

This means that from a fairly short time on, all space is causally connected. This result is of some relevance to the issue of whether traces of the existence of earlier and, like ours, expanding universes can be detected in

. For this it may matter that the space expansion of a universe can also be interpreted as an explosion [

2], whereby its boundary moves almost at the speed of light. That the boundaries of two universes are consequently approaching each other at a higher speed will however only apply to relatively neighboring universes, because the ever faster expansion of space is a genuine space expansion that can only locally be transformed away. This shows again how important it is that the space expansion in our model is genuine, because without it the explosive propagation of universes would have long since led to unmissable collisions between

and other universes.

5. Evolution of Space-Time, Quantum Treatment

The ES starts deep in the quantum regime, which is why one would like to have a WDW equation available for it as well. However, because is time dependent in the ES, one cannot proceed as usual. Even so, we have found a way to get around this difficulty by using the fact that we already know the classic solution . By substituting its inverses into and using one obtains the function , inserts it into the FL equation and can then derive the associated WDW equation as usual. In its solution we separately treat the short transition from timeless to time-dependent associated with the density crash and the subsequent long-lasting evolution until today.

A WDW equation for the ES that includes both the period

of the density crash and the subsequent time

of the space expansion is derived in

Appendix C and is

The initial conditions to be satisfied by solutions are continuity of

and

in the transition from PS to ES at

, i.e. Eq. (

23),

The reasons leading to the density crash also cause extremely rapid changes in

which provide considerable difficulties for a numerical solution. The latter is unavoidable because there are no analytical solutions. Some reduction in difficulty is achieved by changing from the volume

v to the relative volume

(

being defined in Eq. (

22) and calculated in Eq. (

86)) by which Eq. (

64) is transformed into

and the initial conditions (

65) become

(Note that

describes the same physical object as

but is not the same mathematical function.)

5.1. Decomposition of the Wave Function into Branches

Based on numerical results obtained for (relatively) small

values and shown in

Figure 4, we now seek a solution to this equation for the extremely large true value, considering two branches: one, the main or residual branch, with values of

large enough for neglecting the term

against 1 in Eq (

67), and another, the initial branch, with values of

so small that

is practically indistinguishable from its initial value

.

5.1.1. Main Branch

The condition to be imposed on the main branch is fulfilled if

applies for sufficiently large

. Now

where the e-function was expanded into a Taylor series that could be truncated after the second term because of

, due to the extremely large value of

without noticeable error. In summary, the condition is

In particular, we get

The solution of the equation

obtained by omitting the

term in Eq (

67), can be represented in the form

where the coefficients

A and

still need to be determined.

5.1.2. Initial Branch

We now turn to the initial branch, extending from

to

. Because the point

of attachment to the main branch is so extremely close to

, as verified later, we can assume that up to it,

is practically indistinguishable from its initial value

. Under this assumption Eq. (

67) can be integrated with respect to

u, and with use of the initial condition

we get

Executing the integration yields

Neglecting 1 against

and inserting the result in Eq. (

73) yields

Owing to the extremely large exponents in

and

we still perform the expansions

in the exponent, where

was used in the last step as a very accurate approximation for the extremely small values

. With this and with

from Eq. (

69), at

we get

Due to

and

resp. in the denominator, the first and third term between the brackets can be omitted without noticeable loss of accuracy, so we finally obtain

where at last

was omitted, since

and

for all

.

It still remains to show that our above assumption

for

is justified. From

for

according to Eq. (

73) and

according to Eq. (

68a) it follows

. From Eq. (

73) it also follows that

Integrating this inequality and using Eq. (

76) together with

results in

and inserting

from Eq. (

70) we finally get for the initial branch

i.e. we have with vanishingly small error

According to Eqs. (

66), (

70) and (

83a), the volume of the initial branch is

so negligibly small.

5.1.3. Connecting Initial and Main Branch of

The demand for continuity of function and derivative at the junction

, i.e.

and

, yields with the results obtained in Eqs. (

72) and (

78) the relations

where in the sine and cosine

was replaced by 1, due to Eq. (

70) with vanishingly small error. From these, elementary calculations lead to

With this and Eqs. (

66), (

70), (

72) and (

86) results for the solution of Eq. (

64)

valid for all

. (The value of

follows directly from Eq. (

64) with the term

being neglected, i.e. from

.) As in the PS, so in the ES the square of the wave function (

81) is used for calculating probabilities. For the reason of clarity

instead of

is shown in

Figure 5 for a combination of the ES wave function (

81) and the last part of the PS wave function (

20).

Figure 5.

for the wave functions of the PS and Es, for reasons of visibility as a function of

in the PS and of

u in the Es. In addition,

is plotted instead of

so that the transition from PS to ES is easier to recognize. The beginning of

in the ES, that looks like a short piece of a straight line, is actually a piece of the function (

72) and is connected to the function

of the PS at

continuously and with continuous derivative. In the main text it is called appendage branch and treated in a separate section.

Figure 5.

for the wave functions of the PS and Es, for reasons of visibility as a function of

in the PS and of

u in the Es. In addition,

is plotted instead of

so that the transition from PS to ES is easier to recognize. The beginning of

in the ES, that looks like a short piece of a straight line, is actually a piece of the function (

72) and is connected to the function

of the PS at

continuously and with continuous derivative. In the main text it is called appendage branch and treated in a separate section.

5.1.4. Appendage Branch

Between

and

(or the corresponding values of

) there is still a short branch of the wave function Eq. (

72) (or Eq. (

81)), which leads

from 1 to 0 and at first glance may look like a superfluous appendage. It only occurs once, because we consider the subsequent arcs of the cosine function, running between two neighboring zeros of

, as separate quantum states. We assume that like the subsequent ES quantum states, it did not arise from nothing. In consequence it also belonged to the PS, but like the other ES states with a correspondingly smaller amplitude, much smaller mass density and with an independent volume that was not duplicated in the transition to the ES. In this sense, it therefore belongs to both the PS and the ES and is accordingly entered in

Figure 5. The size of its volume is

In fact, this branch is not at all superfluous, because from the last section it is clear that through it the amplitude

A of the ES wave function and thus the probability of the quantum states of the ES (see

Section 5.2.2) is enhanced. However, the space quanta it contains can also be useful for other purposes where it is not important that they are not reproduced. One possibility is that certain fractions of them have merged and survived the density crash as somewhat larger black holes. If there are enough of them, some could later appear in just emerging universes and by sucking up matter grow to bigger ones. Another, even more speculative possibility would be that other parts could form into structures that serve as seeds for the creation of universes.

5.2. Properties of the Main Solution Branch

5.2.1. Volume Increase in Quantum Leaps

The period of

, i.e. the distance

from one of its maxima to the next ( = half period of

) results from

and is

This result means that the volume

v increases discontinuously in leaps of size

. In fact, as in the case of the volume quanta

(or

), quantum leaps of somewhat smaller or larger sizes are possible, if only with lower probability. However, because this would unnecessarily complicate the subsequent discussion of information transfer, we assume that the leaps are all the same size. Later results involving many leaps do not result in errors caused by this simplification because corresponding differences cancel by averaging. On the other hand, the possibility of different sizes even turns out to be advantageous for the individual processes of information transmission (see

Section 5.2.4). The maxima of

are at

in the middle between the zeroes, where

is the position of the first maximum (see

Figure 5).

The quantum states of the ES extend over the volume regions , the width of which is so much greater than the width of the PS quantum states, that they must have a different interpretation. Furthermore, for our concept of information transfer to make sense, the volumes added to the ES with each quantum leap must contain the same information as the PS. To this end, it seems reasonable to assume that they contain the same number of space and information quanta as the PS. It is then only logical to assume that the PS has the same volume as the gradual increases in volume of the ES. Unlike in the case of the PS, each quantum state of the ES does not describe one single space quantum, but very many. Albeit, from the shape of no conclusions can be drawn about how the individual quanta are distributed in space. What we will to do, however, is draw conclusions about the probabilities of the quantum states. The assumptions just made are crucial to our model. Briefly summarized they are: The PS and the space added with each quantum leap of the ES have the same volume and contain the same number of space and information quanta.

According to the above, the quantities

and

defined in Eq. (

22) have the values

or, after using Eqs. (

4) and (

1),

Expressed in multiples of the Bohr radius

we have

The relative size of the volume leaps is

according to Eqs. (

5) and (

36). Starting from the initial value 1 deep in the quantum regime, it continually decreases, due to the small value of

very slowly but nevertheless exponentially, until it disappears for

. This is a paradigm of how quantum effects lose significance in the progression of the ES from the quantum to the classic regime without any approximations being made.

For the time that elapses between neighboring quantum states and is used to transfer information from already existing to newly added volume elements, we obtain from Eqs. (

4), (

58) with Eq. (

83), and

Denoting the time elapsed until the first volume doubling with

, we obtain from this with

,

or

and

according to Eq. (

60)

For

and

according to Eq. (

48), the current expansion parameter is

, and with this we get

5.2.2. Probabilities

The overall wave function of space-time is composed of three piecewise solutions of the WDW equation that are continuously and with continuous derivatives interconnected: essentially Eq. (

20) for the PS, Eqs. (

78) for the the density crash, and Eq. (

81) for the remaining ES. The value of a multiplicative factor, free in the determination of

and (in Eq. (

20)) deliberately set to get

, can be left at its arbitrary value, because we only want to compare different contributions to the total probability, where it cancels. In our simplified determination of the quantum states

by means of the respective maxima of

between successive zeroes, we obtain for the ratio of the probabilities

according to Eqs. (

18), (

20) with

and (

81), (

84) with

where

is (up to the said factor) the probability of the first quantum state of the ES, and

(up to the same factor) the probability of the PS. If the amplitude of the (periodic) wave functions in the PS and ES were the same,

would result instead.

In the case of variable quantum leap sizes, one would (with

and

) assign the probability

to the first quantum state of the ES and compare it with the probability

of the PS. Because the volume used for calculating

contains all space quanta duplicated from quanta of the PS for the information transfer, we must likewise include the volume of the total PS when calculating

. For this purpose, we first calculate the total probability of a single space quantum

of the PS, for which with use of Eqs. (

20) and (

21) we get

The desired overall probability

is obtained by multiplying

by the total number

of space quanta of the PS, given in Eq. (

97), and is

This together with Eq. (

92) results in

the same result as in Eq. (

91).

The results (

91) and (

95) show that the transition from the PS with

via the density crash to the first quantum state of the ES leads to a significantly higher probability. The cause is the density crash, which according to Eq. (

78) leaves the value of the wave function unchanged,

, but influences its further course (Eq. (

72) with Eq. (

80)) in such a way that either Eq. (

91) or Eq. (

95) becomes valid. This also influences the slope and thus the importance of the appendage branch of

: the steeper the drop, the larger the maximum of

.

In analogy to Eq. (

91) the probability of the (simplified)

n-th quantum state in the ES is (up to the irrelevant factor mentioned)

, i.e. the same for all quantum states, whereas an increase with time would be indicated. The latter can be achieved by relating

not to the volume

but to the time

with

and

. With this we get

so an increase with time, that plotted over

v follows a step-like curve with slope

.

5.2.3. Merger of Quantum States with Classical

Time Evolution

The time-independence of wave functions for an entire universe (or space-time in our case) raises considerable difficulties, both in finding suitable ones and in interpreting them, particularly in view of the observed time evolution of

[

19]. A so-called minisuperspace model has been studied to a special extent [

10], where the wave function depends only on the scale parameter

a and a scalar function

representing matter or energy resp. From the corresponding WDW equation solutions for a ground state of lowest excitation and states of higher excitation are derived, whereby semi-classical considerations are used for the boundary conditions to be imposed. Due to the vanishment of the total energy it is difficult to specify more precisely what is meant by excitation, but need not interest us further here.

Our model for pure space-time can also be classified into this scheme, with the important difference that we use the volume

V instead of

a. This difference leads to the fact that instead of the emergence of a universe from nothing as the ground state (see Figure 4 of Ref. [

10] for a numerical and Eq. (101) of Ref. [

5] for an analytical solution) we get the timeless primordial state PS consisting of many space quanta. The deeper reason for this marked difference is that the order of the processes of transformation from

a to

in the FL equation and the derivation of the associated WDW equation are not convertible. Because in Ref. [

10] a wave function is searched which describes the universe we observe, it is concluded that "our Universe does not correspond to the ground state of the simple minisuperspace model but to an excited state". The latter is calculated for a universe with radiation and a cosmological constant. Accordingly, our solution (

81) for the ES after the density crash can also be regarded as an excitation state, although it is derived in a completely different way and applied to a different physical situation. Furthermore, because it comes from quantization of a classical solution, it is also semiclassical. Unlike in Ref. [

10], however, we do not give up our ground state but connect it continuously and with continuous derivative to our solution for the ES.

Let us now turn to the (interpretation) problem of how time-independent solutions of the WDW equation can be related to temporal evolution. A solution was already given by DeWitt [

20] in 1967. With reference to this, Linde writes on page 198 of Ref. [

21], somewhat simplifying, that

is separated into two parts, a macroscopic observer with a clock, and the rest. Both parts can evolve in time according to the observer’s clock, but together they build the timeless universe. On page 1136 of Ref. [

20] DeWitt separates the world into three parts. The material content of

is one of them and can be seen "as a clock for determining the dynamical behavior of the world geometry". The latter is precisely the way in which time comes into play for the quantum states (

81) associated to the volumes

of Eq. (

84), which in turn are associated to the densities

obtained from Eq. (

52). With this it finally results from Eq. (

63) that the quantum states under consideration occur at times

. Because Eq. (

63) follows from the classical Eqs. (

36) and (

52), we can say that our description of the ES is an equal side by side combination of classic and quantum solutions (certainly not complementary).

Let us still briefly pursue the question of what properties a QG model must have in order to enable the transition from a ground state, e.g. our timeless PS, to a time-dependent ES. For this, the system under consideration must in addition to the quantities describing its geometry (e.g. the scale parameter a) still contain another parameter that can be used to describe changes of state. In earlier papers employing a WKB method for finding approximate quantum mechanical solutions, this parameter is an imaginary time interpreted as a space coordinate, whose continuous shift leads from imaginary via zero to real values and thus to a temporal evolution. In the WDW approach, often a scalar function is used, which e.g. is intended to describe a matter field and is quantized just like geometric parameters. In our case, where takes on the role of the additional parameter, the latter is not possible, because that part of which comes from the friction term and is essential for our model, would be treated inadequately. The new path we took to quantize the ES was therefore inevitable.

5.2.4. Cloning of Space and Information Quanta

We assume that the information about the laws of nature is geometrically stored in finite, but microscopically small bundles of partially distinguishable space quanta, which can be understood as

information quanta.

4The equality of the volume leaps means that they all contain the same number of space and information quanta, and that each one of them is duplicated, or, in other words, cloned during one volume leap. An immediate consequence is that the volume of the space quanta does not change in time. On the other hand, their mass

is like

monotonically decreasing, which means that the space quanta have both time-varying and time-invariant properties.

Note that cloning does not necessarily create just one coherent area of new space. This would only be the case if the volume added by one quantum leap would contain only one information quantum. If there were several, they would be scattered all over the already existing space, which also applies to the constructs contained in the appendage branch. According to Eq. (

101) the production rate

of new space quanta is constant, which agrees well with the assumption that we are dealing with a cloning process that occurs with constant probability.

Little can be said about the size of the volume which contains the information about all primary laws of nature. Due to their complexity must contain very many space quanta. However, from our assumption, that all information is transmitted during one quantum leap, it follows that . If is slightly smaller than , with relatively small integer n must hold. Thus in short we can put on record . In the case with the quantum leaps of the ES volume can have different sizes, namely with , and their description by an extended wave function makes different sizes possible.

5.2.5. Number of Space Quanta

The number of space quanta

contained in the volume

of the PS results from Eqs. (

21) and (

86) and is

According to our model, this number (or a not much smaller fraction

with

) must suffice to contain the entire information about all primary laws of nature. For the present total number of volume quanta

of the ES, Eqs. (

83) and (

104) yield

and the present number of space quanta

is

For the time evolution of the number of space quanta we obtain from Eqs. (

4), (

5), (

36) and (

97)

and

5.2.6. Mass of Space Quanta and Total Mass of Space

Resulting from Eq. (

21) and the mass densities given in

Table 2, the mass

of space quanta at various times

t is listed in

Table 4.

For comparison, the current upper limit of the neutrino mass (15. February 2022, see Ref. [

22]) is

.

For the total mass of space in the PS we get with Eqs. (

32b) and (

87a)

where

is the mass of the sun and

is the mass of the milky way [

23]. (The corresponding energy is

). The total mass at the time

immediately after the density crash is

where

is taken from

Table 2. Using Eqs. (

1), (

4), (

47),

,

and Eq. (

48), we get for the present total mass of space

For

and thus

we get with Eqs. (

4c) and (

52a)

For later purposes, in analogy to Eq. (

62) we still calculate, by how much the total mass changes during the lifetime of

. Using Eq. (

62) first and then Eqs. (

5), (

36) and Eq. (

61), we obtain

and finally

5.2.7. Entanglement of the Emergence of Time and

the Density Crash

Mathematically, the (initial) density crash seems to be due to the (much later) extremely low present value

of the DE density. This almost looks like a reversal of cause and effect, which is of course unacceptable. Conversely, a reason for the initial density drop should explain the low present value. An important hint for this is given by the equation

from

Table 2, by which the present DE density can be represented and from which its small value results. According to Eqs. (

56) and (

57), regardless of the present density a rather small value of

is necessary for a large density drop, and according to

Section 5.1 and

Section 5.2.2, the latter is in turn the prerequisite for the high probability of the transition PS→ES and the associated emergence of time. The latter is therefore the cause of the small value of

.

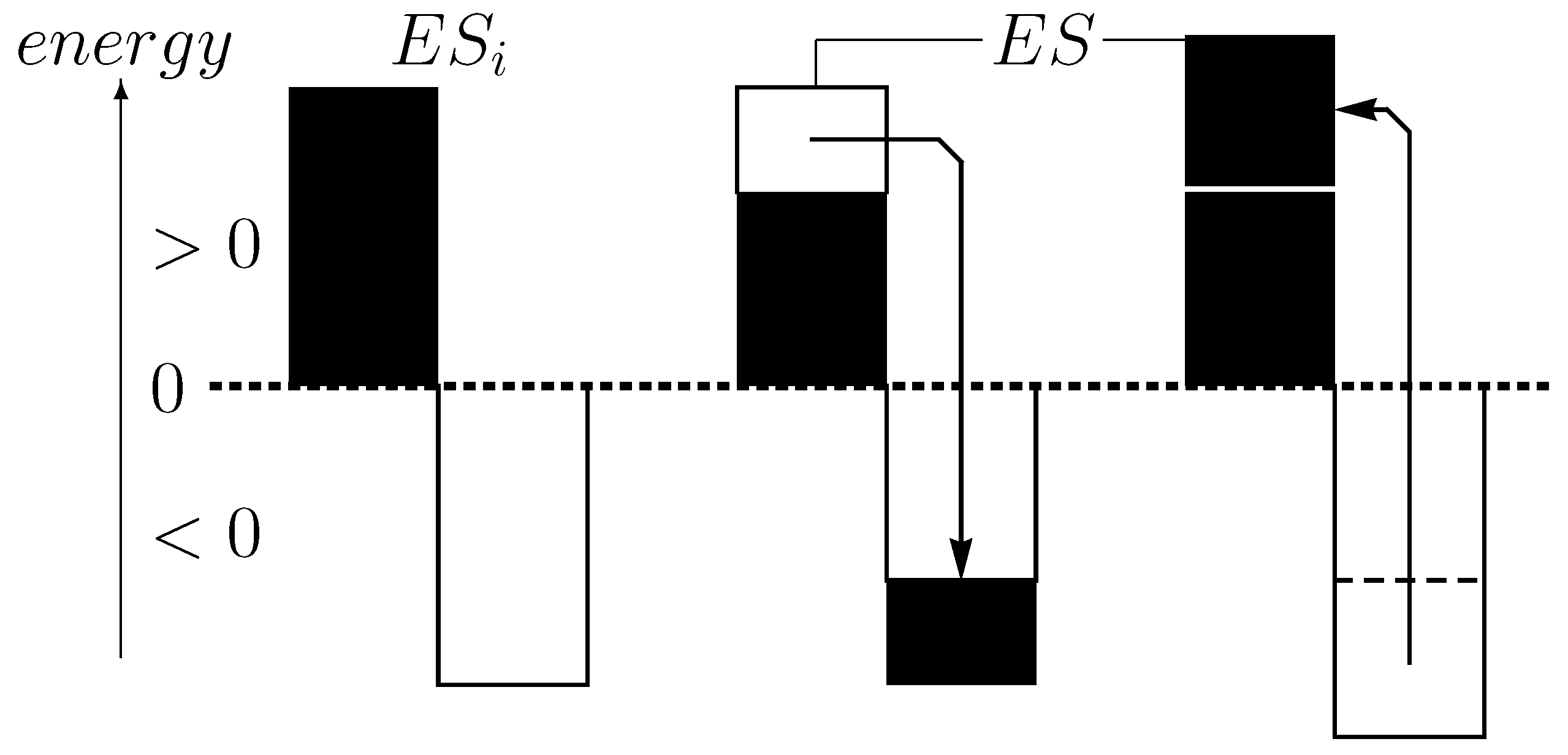

A comparison of the masses

and

given in Eqs. (

102) and (

103), or the corresponding energies

shows that for the birth of time almost the entire DE energy as well as the corresponding (negative) gravitational energy of the PS must be spent. Due to its intrinsic entanglement with the density crash and because the latter occurs so incredibly fast, the birth of the time can truly be called a plunge birth. (This spectacular event represents an essential difference to other models (e.g. Refs. [

7,

8,

9,

10]), in which this transition is accomplished without any physical conspicuousness.)

We still want to find out if the birth of time, called emergence above, is an emergence in a scientific sense as used in system theory, philosophy or various natural sciences [

24]. For this purpose we use the following definition:

Emergence means that a system of many (same or different) elements has properties that are based on cooperation of the elements and which can either 1. principally not, or 2. not without knowledge of the system properties, be traced back to properties of the individual elements. Case 1 is called strong and case 2 weak emergence.

In our model, the system is space-time, and its elements are space quanta, which are treated as same in this paper for simplicity, but because of our assumption about the storage of information should consist of groups with mutually different properties. Observable system properties appear only after the entry of time or after the density crash resp., because unlike the big bang of

, the big crash of our model leaves no measurable traces. From a theoretical point of view, however, the crash is an important system property, which can be traced back to a cumulative effect of the many space quanta of the PS: According to

Section 5.1 and

Section 5.2.2, the density crash, needed for the occurrence of time, can only come about by the fact that the PS contains extremely many space quanta and thus a very high energy

, whose conservation at the transition PS→ES (i.e.

and

) requires an extremely high initial expansion velocity

or

resp. for providing the energy to be spent in the crash. From this it becomes evident that the density crash represents weak emergence. On the other hand, the appearance of time as a fourth variable in addition to the three spatial coordinates can surely be classified as strong emergence. However, exclusively restricted to (in principle) provable properties, the system reduces to the branch

of space-time or even

, starting with the much smaller density

or

, and time is an integral part of the system from the outset and thus not emergent.

5.2.8. Schwarzschild Radii

We now address the question of how the Schwarzschild radii of the space quanta change over time. To this end, at first we slightly reshape Eq. (

26) using one of the relations (

3),

With this,

and Eq. (

21) we obtain

Typical values of this quantity are listed in

Table 5.

In the PS with over

space quanta, the space curvature is already so small that we can calculate the radius of a sphere of volume

with the Euclidean formula, yielding

This is significantly smaller than the Schwarzschild radius

, so our assumption that the space quanta in the PS are mini black holes, whose mass is concentrated in one point, is justified. We assume that the view of space quanta as point masses also applies after the density crash, even if the Schwarzschild radii are then much smaller, because there is no reason for the mass to disperse, but also because concepts with lengths

wouldn’t make sense.

7. Discussion

Our model uses generally accepted equations of physics and deviates from the usual mainly in their interpretation. An exception is only the introduction of a linear friction term into the cosmological momentum equation, but this is compensated by the fact that it is done in a way that the Friedmann-Lemaître equation keeps its full validity. In

Appendix E it is even shown that our classical solution for the ES satisfies the usual equations for a minisuperspace with a scalar potential

, rolling downhill in a simple parabolic potential

. Our model turned out to be surprisingly consistent in all the properties discussed. For many of them this could not be expected in view of the few assumptions used as an input, but rather came out as a result. One example for this is, that space-time is much older than

, another, that the average probability of the ES is significantly larger than that of the PS, and still another, that the present number of space quanta is much larger than the number of atoms in

. But is our model also "correct" in the sense that it is as a whole or at least in parts actually realized? The answer to this question is not known, and it is even possible that our model is "wrong" in the sense stated. The reason for this is as follows: Physical equations have a manifold of distinct solutions, but many of them are not realized in the world we observe.

7To make matters worse, it’s likely there is only one space-time, which reduces the probability that a correct solution for it is also the realized one. In the worst case, all that remains is the hope that questions posed and answered with our model make sense and are worth pursuing further.

An interesting results is the lightning-like huge crash, which initiates the emergence of time. In a way, it is the opposite of a big bang, because it prevents an expansion that starts with enormous speed. Also quite different from a big bang it does not develop from an energetic singularity, but from the very large, but finite energy of the PS. Unfortunately, one consequence of these differences is that, unlike the big bang, it leaves no trace that would be detectable today. (Note that the density crash of our model does not replace the big bang, but precedes it.)

Our most important result and of central importance for the overall concept of our model is the interpretation of the solution of our WDW equation for the PS as an aggregate of

space quanta. If this turns out valid, and also according to the space quanta concept of the LQG, it raises doubts about the validity of various scenarios for the origin of

, which in a WKB approach extend the solution of an FL equation from real to imaginary values of time, then interpreted as a fourth space coordinate. In Refs. [

5,

7,

8],

emerges from absolute nothingness, its volume growing from zero to Planck size. In Ref. [

9], the volume of

attenuates from somewhat larger size down to Planck size in a kind of tunneling process. In cases of this kind, the fourth space coordinate is an arithmetic auxiliary for an actually time-dependent process. Not so in the no boundary proposal of Ref. [

11,

32], where the imaginary time as fourth space coordinate is twisted so that a timeless PS is created. The above mentioned doubts arise from two arguments: 1. The four spatial coordinates supposed to describe the PS of

all extend in the range of

and can therefore be covered by a single space quantum. The granularity of space is therefore far too coarse to provide the structure required for the intended purpose. 2. In the more advanced theories of quantum gravity, such as loop quantum gravity, there is no time in the ground state of the quantum regime. As a result, the assumption of a fourth spatial dimension becomes obsolete.

Our model shares one problem with models about multiverses that contain parallel universes in addition to : At present there are no observations that allow to draw inferences about the results of the models. In question would be peculiarities at the edge of our observable universe, suggesting the existence of parallel universes via collisions with them. With our model, the decrease of the DE density predicted by it would be another way to check its validity.