The galactic rotation curve has been observed and studied for a long time.[

1,

2,

3] Because of the advancement of the technology, now, the observation of the velocity of the orbit of the stars in our galaxy is more accurate and precision in a larger area.[

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] First, in 2020, the fastest star in the Milky Way was observed.[

4,

5,

6] The S62 has the shortest known stable orbit around the supermassive black hole in the center of our Galaxy to date. It is with

and a periapse velocity of approximately 10% of the speed of light.[

4] It is contradicted with the galactic rotation curve [

1,

2,

3] in which the largest velocity is

at the distance of

from the center of the galaxy. Second, in recent, the circular velocity curve of the Milky Way from 4 to 30 kpc was measured.[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] It was observed that a significantly faster decline (Keplerian decline) in the circular velocity curve compared to the inner parts. It is contradicted with the previous observation for the galactic rotation curve in which the out parts could be larger or no decline. Third, in recent, it was observed that the fast galaxy bars continue to challenge standard cosmology [

12,

13,

14] and the ultrafast bar cannot be ruled out.[

15] Therefore, new understanding is needed for the new observations.

Here, we emphasize, the current theory for the orbit of the star/stellar around the center of the galaxy was misled by the Poincaré’s equation for Three-body problem. For the convenience of the readers, we copy our previous sentence here:[

16]

Newton established the theory of orbit in 1660s. But, Newton’s theory has not been completely understood till now. As soon as comparing Poincaré’s equation of Three-body problem with Newtonian orbital perturbation theory, we shall know what is the problem in current understanding about Newtonian theory of gravity. The Sun-Earth-Moon system is the oldest Three-Body problem. It is clear, the orbits about it was well resolved by Newton. But, there is a famous old problems: calculating with

, the attractive force of the Sun on the Moon is almost 2.2 times that of the Earth, but the orbit of the Moon around the Earth cannot be broken off by the Sun. It is clear, as Poincaré’s equation for Three-body problem is applied on the solar system, the orbits in it should be broken off in a short time. We think, this is the crucial evidence to show that the Poincaré’s equation for Three-body problem is wrong. And, the triple star system and multiple star systems, including Six-star system,[

17,

18] were observed. The orbit in these systems are stable and certain.

The Poincaré’s equation for Three-body problem is very strange. First, no orbit of the celestial body is chaotic. A broken orbit also is predictable. So, Poincaré’s equation cannot be related with any real orbit. Second, the orbits of the typical Three-body system, such as the Sun-Earth-Moon system and Sun-Pluto-Charon system, are stable. Poincaré’s equation is invalid to understand these orbits. Third, Poincaré’s equation is invalid to design an artificial orbit. It is very clear, the Poincaré’s equation is nonsense in understanding any real orbit. Additionally, the relationship between the Poincaré’s equation and other theory is very weak. If there was not Poincaré’s equation, the celestial dynamics could not be affected. But, very unfortunately, Poincaré’s equation is the mainstream understanding about Newtonian theory of gravity. It results in that, the current theory of orbit about the galaxy is questioned.

Applying the Poincaré’s equation to the N-body problem, there is the Poisson equation: , , . Therefore, the Poisson equation is also wrong in studying celestial orbit. Consequently, the formula, , where M(R) is the sum of all the mass in the radius of R, is wrong.

In the Newtonian theory of gravity,[

16] the radius and velocity of the orbit of all the stars/stellar in a galaxy is only determined with

where,

is only the mass of the center of the galaxy.

For the S62, as

and a periapse velocity of approximately 10% of the speed of light,[

4] approximately under the condition of that the orbit of S62 is a circle, it could be easily known that the radius of the orbit is almost

. From

, we know, there should be

. From the velocity of the orbit of the Sun around the center of the Milky Way, it could be concluded that the mass of the center of the Milky Way need be

. In consideration of the circular velocity curve of the Milky Way [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], we intend to believe that the mass of the center of the Milky Way should be

. Here, it is emphasized that the conclusions of current observations were misled by the wrong Poisson equation (or the Poincaré’s equation). It is clear, the galactic rotation curve and that the center of the Milky Way is

only is a conclusion of the Poisson equation and it is clearly contradicted with the new observations in [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Therefore, new understanding and more accurate and precision measurement are needed to have a more accurate mass for the center of the Milky Way.

We noted that,

is a very big mass. Currently, it is thought that the mass of the center of the Milky Way is

[

18,

19] and the total mass of the Milky Way is

. [

20] But, the mass of

is too little for the orbit of S62 with the periapse velocity of approximately 10% of the speed of light and

[

4,

5,

6] as the Roche limit is considered. And, it is noted that, for S62[

4,

5,

6], as

and the pericenter distance

, there only is

.

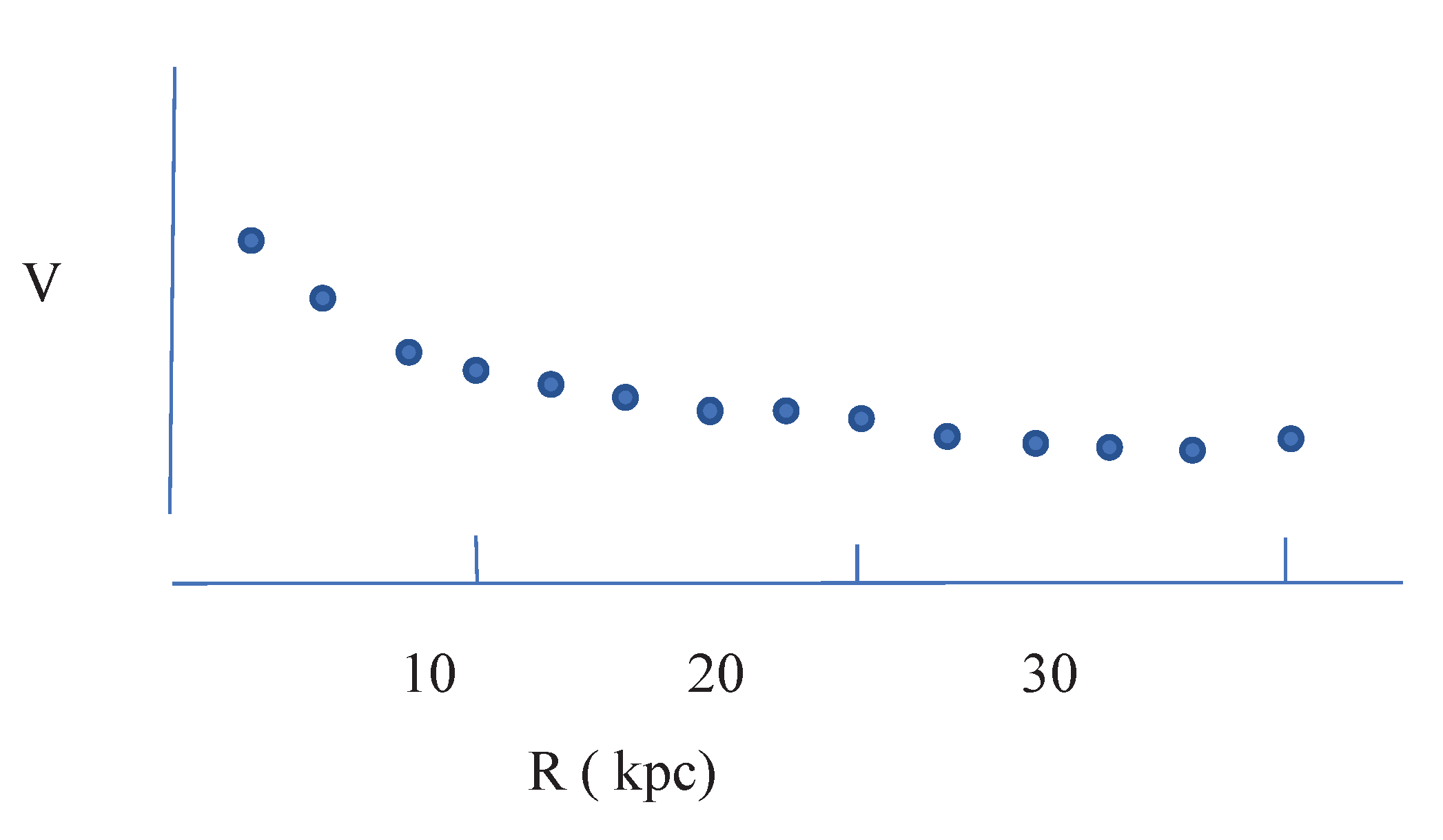

From

, the complete figure for the circular velocity curve of the Milky Way for

could be shown with the

Figure 1.

It is noted that, in the Newtonian theory of gravity, besides the center of the galaxy, other stars also has actions on the orbit. Because all stars are orbiting around the center of the galaxy,[

16,

22] just as the planets are orbiting around the Sun, and, only the Newtonian theory of orbit perturbation is valid to understand the celestial orbit,[

16,

23] the orbit of a star around the center in a galaxy only can be described with the Newtonian theory of orbit perturbation:

where c and s denote the center of the galaxy and the stars,

is the perturbation of other stars on this star,

, where

is a vector. From Eq.(2) we know, (for convenience, assuming that the orbit is a circle,) the radius and velocity of an orbit is determined with Eq.(1) while it is perturbed by other stars/stellar with

. But, the perturbations are so little that the radius and velocity of the orbit can be determined with Eq.(1). And, as the perturbation is large, the orbit shall be broken of. So, to know the velocity of the orbit for our purpose, the perturbation need not be considered. Therefore, although the

Figure 1 is only an approximation to the real orbit, it is useful to know the velocity and radius of an orbit.

Conclusion and discussions: The

Figure 1 is a new predicted galactic circular velocity curve by returning to the Newtonian theory of gravity. The observations in [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] could be complete evidence for it. We emphasize, the observation of the fastest orbits [

4,

5,

6] around the center of the Milky Way is very significant for understanding the mass of the center. It clearly showed that the current galactic rotation curve [

1,

2,

3] is questioned. In theory, in the

Figure 1, it is shown that, the velocity of any one single star in the radius of

is larger than the largest velocity

in the galactic rotation curve with

as

. In observations, the velocities of

of the orbit near the center of the galaxy were observed.[

4,

5,

6] And, the ultrafast galaxy bar was observed.[

12,

13,

14,

15] Therefore, the mass of the center of the Milky Way could be accurately known from the circular velocity curve of the Milky Way [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

The mass of the center of the Milky Way is one of the critical factors about the structure and origin of the galaxy. Therefore, new understanding is needed for the new predicted mass of the center. But, factually, new understanding is needed in more general area. As I know, first, the Poincaré’s equation with the Poisson equation need be excluded from the theory of the orbit of the galaxy. We have had no evidence to show that the Poincaré’s equation with the Poisson equation is valid to the orbit in the galaxy or any other orbit. It is only a misunderstanding about the Newtonian theory of gravity.[

16] Therefore, we need return to the Newtonian theory. Second, the gravitational field is with a very tremendous energy and energy density. It is omitted in current theory of gravity while it should be very important to judge the dark energy.[

24,

25] Third, a galaxy is always moving. Then, how is this galaxy moving? Is it with an orbit around a larger object? These problems showed that our knowledge about the galaxy is poor. We need new knowledge about it from new observation.

References

- Yoon, Y.; Park, C.; Chung, H.; Zhang, K. Rotation Curves of Galaxies and Their Dependence on Morphology and Stellar Mass. Astrophys. J. 2021, 922, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, S.S.; Lelli, F.; Schombert, J.M. Radial Acceleration Relation in Rotationally Supported Galaxies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 201101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGaugh, S.S. The Third Law of Galactic Rotation. Galaxies 2014, 2, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peißker, F.; Eckart, A.; Parsa, M. S62 on a 9.9 yr Orbit around SgrA*. Astrophys. J. 2020, 889, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Peißker, A. Eckart, M. Zajaček and S. Britzen, Observation of S4716- A star with a 4 year orbit around Sgr A*, ApJ, 933, 49 (2022).

- F. Peißker, A. Eckart, M. Zajaček, S. Britzen, B. Ali and M. Parsa, S62 and S4711: Indications of a Population of Faint Fast-moving Stars inside the S2 Orbit—S4711 on a 7.6yr Orbit around Sgr A*, ApJ, 899, 50 (2020).

- Eilers, A.-C.; Hogg, D.W.; Rix, H.-W.; Ness, M.K. The Circular Velocity Curve of the Milky Way from 5 to 25 kpc. Astrophys. J. 2019, 871, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mróz, P.; Udalski, A.; Skowron, D.M.; Skowron, J.; Soszyński, I.; Pietrukowicz, P.; Szymański, M.K.; Poleski, R.; Kozłowski, S.; Ulaczyk, K. Rotation Curve of the Milky Way from Classical Cepheids. Astrophys. J. 2019, 870, L10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-F.; Chrobáková. ; López-Corredoira, M.; Labini, F.S. Mapping the Milky Way Disk with Gaia DR3: 3D Extended Kinematic Maps and Rotation Curve to ≈30 kpc. Astrophys. J. 2022, 942, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Hammer, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Amram, P.; Chemin, L.; Yang, Y. Detection of the Keplerian decline in the Milky Way rotation curve. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 678, A208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Eilers, A.-C.; Necib, L.; Frebel, A. The dark matter profile of the Milky Way inferred from its circular velocity curve. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2024, 528, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, M.; Ghafourian, N.; Kashfi, T.; Banik, I.; Haslbauer, M.; Cuomo, V.; Famaey, B.; Kroupa, P. Fast galaxy bars continue to challenge standard cosmology. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 508, 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Fragkoudi1, R. J. J. Grand, R. Pakmor, V. Springel, et al., Revisiting the tension between fast bars and the CDM paradigm, A&A650, L16 (2021).

- Corsini, E.M.; Aguerri, J.A.L.; Debattista, V.P.; Pizzella, A.; Barazza, F.D.; Jerjen, H. The Bar Pattern Speed of Dwarf Galaxy NGC 4431. Astrophys. J. 2007, 659, L121–L124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguerri, J.A.L.; Méndez-Abreu, J.; Falcón-Barroso, J.; Amorin, A.; Barrera-Ballesteros, J.; Fernandes, R.C.; García-Benito, R.; García-Lorenzo, B.; Delgado, R.M.G.; Husemann, B.; et al. Bar pattern speeds in CALIFA galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 2015, 576, A102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, Interaction of Gravitational Field and Orbit in Sun-planet-moon system[v1] | Preprints. [CrossRef]

- J. Kazmierczak, Discovery Alert: First Six-Star System Where All Six Stars Undergo Eclipses (2021).

- Boyle, L.; Cuntz, M. Orbital Stability of Planet-hosting Triple-star Systems according to Hill: Applications to Alpha Centauri and 16 Cygni. Res. Notes AAS 2021, 5, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genzel, R.; Eisenhauer, F.; Gillessen, S. The Galactic Center massive black hole and nuclear star cluster. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 3121–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaoun, S.; Johnson, M.D.; Blackburn, L.; Brinkerink, C.D.; Mościbrodzka, M.; Chael, A.; Goddi, C.; Martí-Vidal, I.; Wagner, J.; Doeleman, S.S.; et al. The Size, Shape, and Scattering of Sagittarius A* at 86 GHz: First VLBI with ALMA. Astrophys. J. 2019, 871, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.J.; Menten, K.M.; Zheng, X.W.; Brunthaler, A.; Moscadelli, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Sato, M.; Honma, M.; Hirota, T.; et al. Trigonometric parallaxes of massive star-forming regions. Vi. Galactic structure, fundamental parameters, and noncircular motions. Astrophys. J. 2009, 700, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu,(PDF) The speed of gravity: An observation on galaxy motions (researchgate.net).

- J. Bekenstein, Physics Crunch: Time to Discard Relativity? NewScientist, 217, 42(2013).

- Y. Zhu, Gravitational Field and Mass[v2] | Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, Relativistic Mass of Gravitational Field[v1] | Preprints. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).