1. Introduction

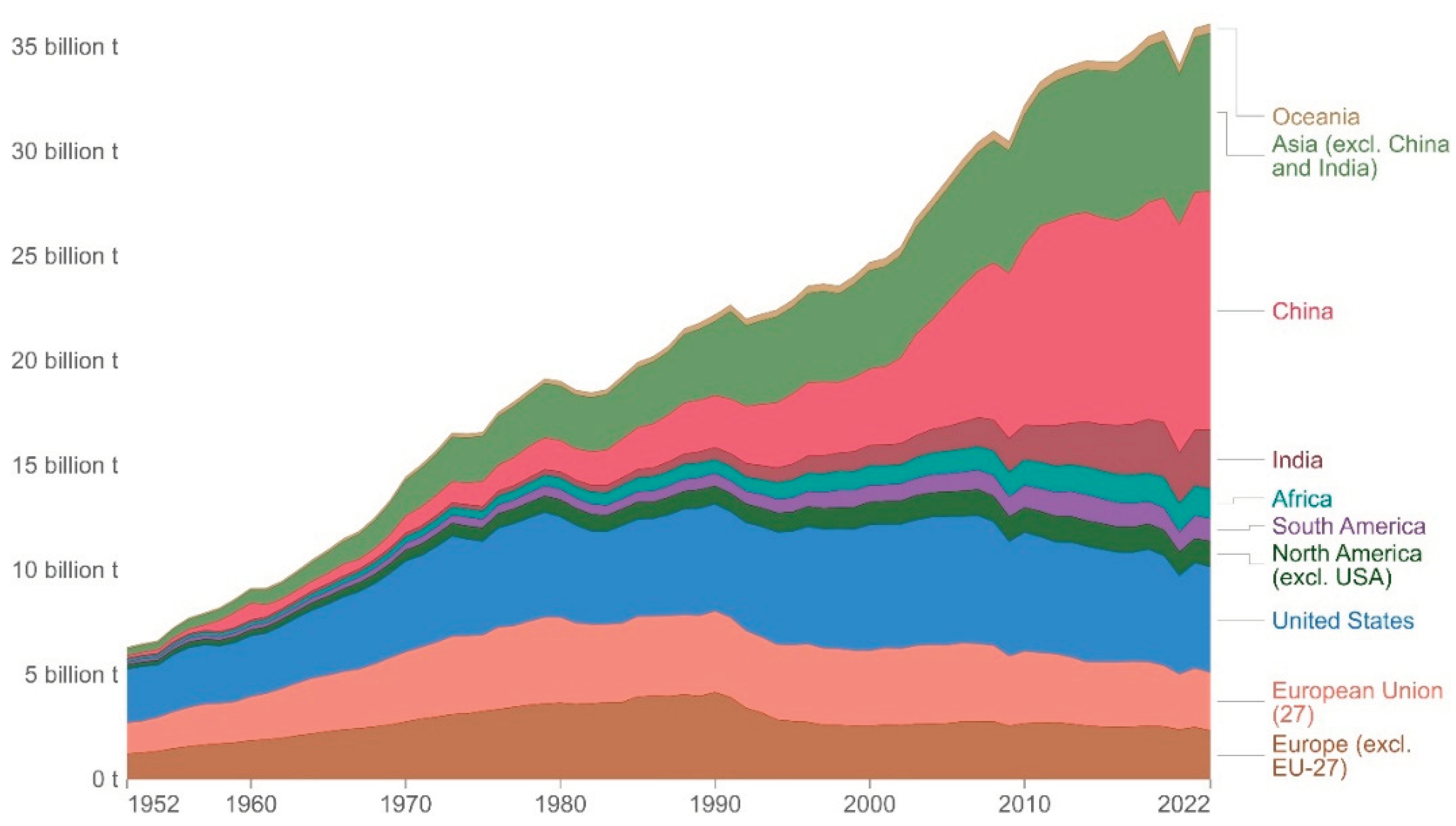

Carbon dioxide (CO

2) is a greenhouse gas and plays a major role in the regulation of Earth’s temperature and affecting global warming patterns. Its concentration in the atmosphere has increased significantly over the past several decades [

1,

2,

3] (

Figure 1). Most carbon on Earth is bound in minerals and sequestered in deep-sea sediments, reminding us that increasing the uptake of CO

2 in minerals could reduce the greenhouse gas content in the atmosphere. Mineral carbonation is the process by which carbon dioxide (CO

2) reacts with minerals in rocks to form solid carbonates and represents the most environmentally and geologically stable method for carbon disposal [

4]. This reaction can occur naturally over geological timescales or can be artificially accelerated for carbon capture and sequestration [

5]. Moreover, anthropogenic gas emissions are projected to alter future climate with potentially non-trivial impacts [

6], and the effects of increased CO

2 concentrations can be clearly documented through greenhouse effects, ocean surface acidification, and ecosystem fertilization [

7,

8].

The observed increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO

2) concentrations motivates the study of carbon capture and storage (CCS) as an important component of multilateral strategies to mitigate the risks of future climate change. Proposed reservoirs for CO

2 storage include terrestrial biomass, deep sea, saltwater aquifers, and minerals, and these reservoirs differ significantly in terms of the rate at which stored CO

2 leaks into the atmosphere. Characteristic storage periods increase from terrestrial pools (tens to hundreds of years), deep sea (hundreds of years), geological reservoirs (thousands of years), to thermodynamically stable minerals (> thousands of years) [

9,

10]. Carbonation is a process that can be performed on metal-rich, non-carbonate minerals (e.g., Mg

2SiO

4 i.e., Mg

2SiO

4 olivine, Mg

3Si

2O

5(OH)

4 serpentinite, CaSiO

3 wollastonite) to geologically and thermodynamically stable mineral carbonates (i.e., MgCO3 magnesite, MgCa(CO

3)

2 dolomite, CaCO

3 calcite, FeCO

3 siderite, NaAl(CO

3)(OH)

2 dawsonite) by induced exothermic alteration [

11]. This technique attempts to mimic the natural low-temperature alteration (carbonation) of a wide range of silicate rocks that safely trap CO

2 over geological time [

7,

12,

13]. Among various mineral species that can undergo carbonation reactions, Mg-rich minerals, as well as Ca-carbonates, are very interesting acting as important reservoirs of CO

2 since they are highly abundant at the Earth’s surface.

The mineral carbonation process is typically a reaction of olivine or serpentinite with carbon dioxide to form magnesite + quartz + water: Mg

3Si

2O

5(OH)

4 + 3CO

2 = 3MgCO

3 + 2SiO

2 + 2H

2O [

14]. The rate of CO

2 sequestration in nature is controlled primarily by reactive surface area, temperature, pH, and CO

2 partial pressure. There is an obvious advantage of in-situ carbonation since CO

2 is injected in-situ, with no need to mine, pulverize, or activate the serpentine rock. The ophiolites of the South Apennines (Italy) represent a natural analogue for in-situ mineralogical sequestration of CO

2. By binding the CO

2 in silicate rocks through mineral carbonation, it is possible to produce stable, also naturally occurring, carbonate rocks [

15].

The typical procedure starts with a complete characterization of the mineralogy and composition of the rock, followed by laboratory and pilot-scale reactivity tests to determine the rate and extent of the carbonation reaction of a given rock [

16,

17]. In the case of field studies, once carbonation has started, the process is monitored to determine the extent of carbonation over time and to ensure long-term carbonate stability [

7,

18,

19]. In the quarry site, the serpentinite rocks reacting with calcite in the presence of CO

2 could be a useful sink for carbonation processes and CO

2 storage.

Serpentinites cropping out in the Pollino mafic–ultramafic massif in the Calabria region of southern Italy have been studied extensively and analyzed for their mineralogical, petrographic, and chemical characteristics, which also provided relevant findings on their impact on environmental and human health [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Cataclastic serpentinites are more apt to be carbonated due to their texture with extensive fracturing of individual grains that increases the reactive surface area of minerals. Regarding future perspectives, it can be interesting to undertake a petrological study of the serpentinites of the Pietra Pica quarry with particular attention to the carbonate phases present and to the existence of talc, to check whether the serpentinites of the Pollino Massif can be used for the induced mineral Carbon Capture Storage.

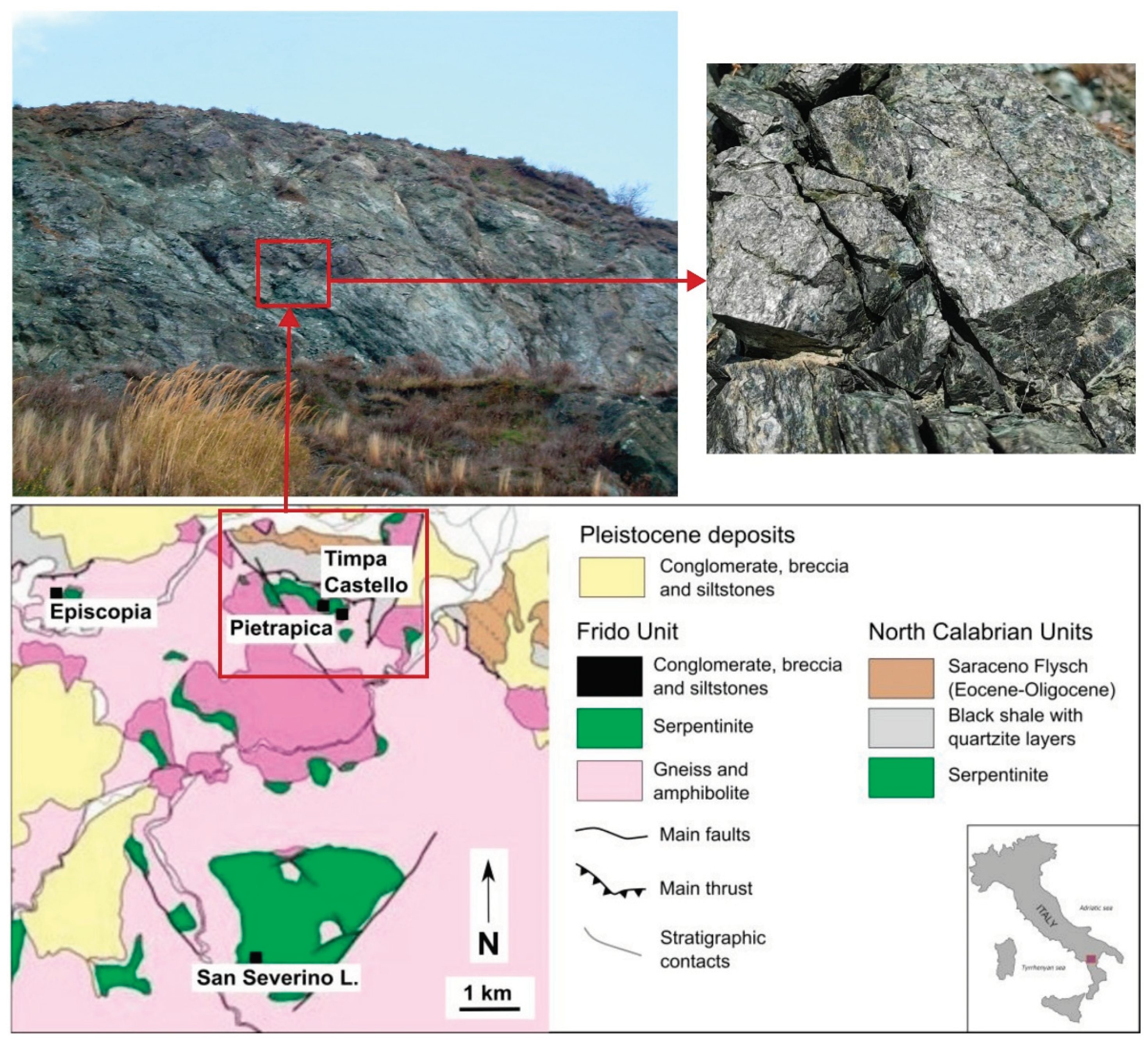

2. Geology of the Pollino Ophiolite Massif

The Pollino Massif in the Southern Apennines (Italy) is located within the continental convergence zone between Eurasia and Africa and is composed mainly of Mesozoic and Tertiary magmatic and sedimentary rocks derived from the Ligurian ocean basin and the African passive margin. These oceanic and continental crustal rocks are overlain by Pliocene – Pleistocene terrestrial deposits [

26] (

Figure 2). Collectively, the Pollino Massif and the continental crustal rocks make up the Liguride Complex of the Apennines and the Calabria region [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

The Pollino Massif (Jurassic palaeo – oceanic lithosphere) is part of the Frido tectonic unit [

33], which includes a metasedimentary sequence (phyllite, meta-arenite, quartzite, and blocks of calcschist and metapelite; [

34,

35] and a Hess-type, incomplete ophiolite, composed of serpentinite, metabasalt, metagabbro, metapillow lavas, and dismembered metadolerite dikes [

16,

27,

36]. The Pollino massif likely represents a fossil ocean–continent transition zone or a continental margin ophiolite [

37,

38], reminiscent of the modern Western Iberia rifted margin [

39]. The second major tectonic entity in the Frido Unit is a non-metamorphic Calabro-Lucano Flysch or the North Calabria Unit. The Pollino Massif tectonically overlies the North Calabrian Unit and forms the structurally highest tectonic unit in the Liguride Complex.

Different interpretations have been proposed for the geological origin of the Liguride complex [

40,

41,

42]. Bonardi et al. [

28] have suggested that metapelitic rock assemblages, including both continental crustal and ophiolitic rocks, constitute a mélange zone (Episcopia – San Severino mélange). Other interpretations consider the Liguride complex as a stack of thrust sheets in an accretionary prism complex, characterized by variable lithologies and metamorphic overprints [

30,

34]. The rock units in the Frido Unit underwent HP-LT, blueschist facies metamorphism [

43].

2. Materials and Methods

Serpentinite samples of the Frido Unit selected for this pilot study were collected at Pietrapica quarry, near the settlements of San Severino Lucano and Episcopia (Calabria-Lucanian boundary, Basilicata region, southern Italy), where outcrops of the Pollino massif serpentinites are widespread. Macroscopically, the analyzed serpentinites have been divided into two main types: (i) cataclastic types, showing fracturing and rigid-body rotation of mineral grains or aggregates; and (ii) massive types, consisting of fractured serpentinites embedded in cataclastic serpentinites. Recent petrographic and mineralogical studies have documented the occurrence of asbestos minerals in the area (e.g. [

20,

21,

22,

32,

44,

45].

Petrographic investigation of all the specimens was carried out by using a Nikon Alphaphot-2 YS2 optical microscope on thin sections of rock samples. Mineralogical analyses were performed on randomly oriented powder by using a Philips X’Pert 3040PW with CuKα radiation, 40 kV and 40 mA, 4 s per step, and step scan of 0.01 °2θ, in the Department of Sciences at University of Basilicata.

3. Results

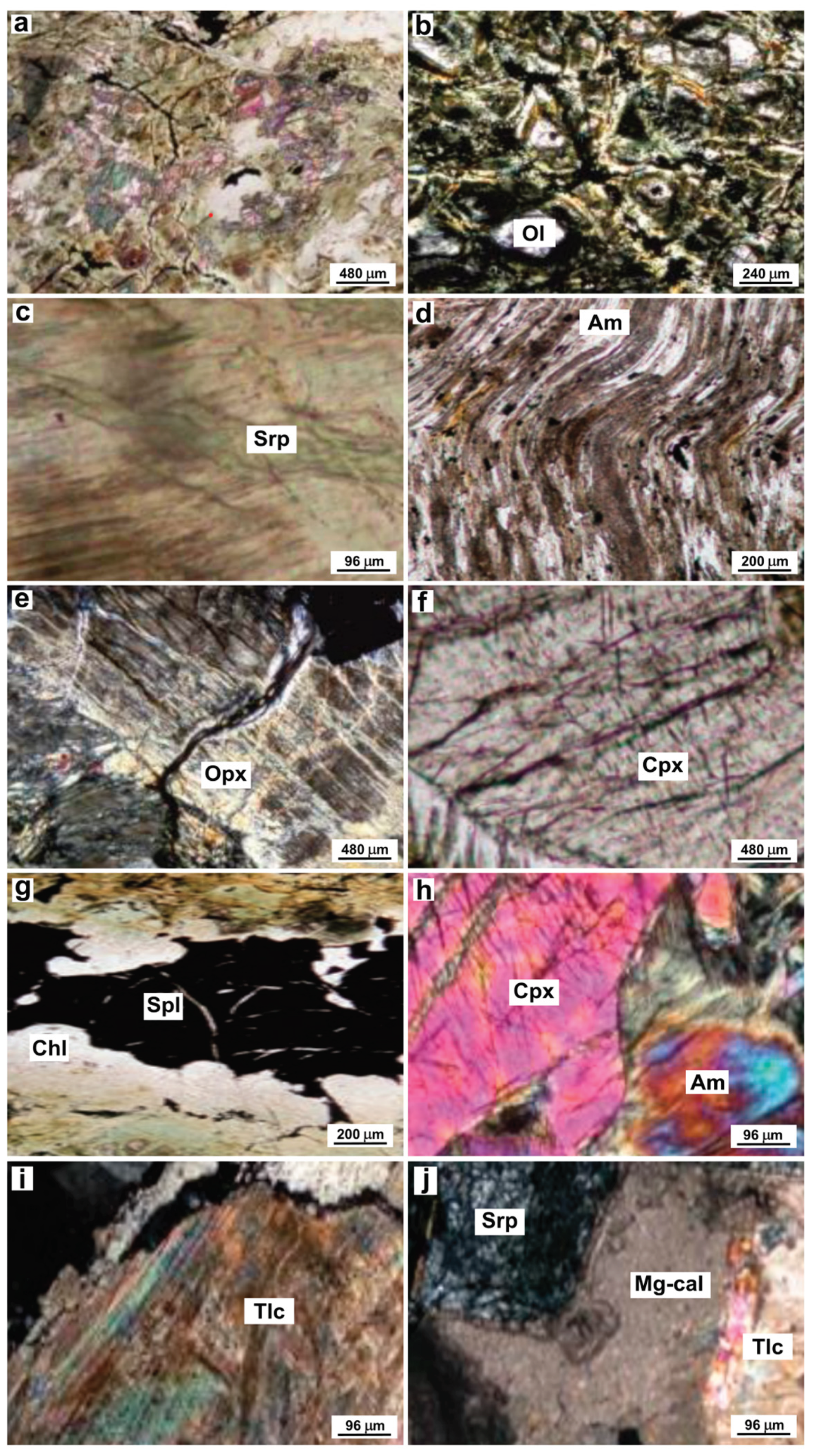

The studied serpentinite rocks are characterized by pseudomorphic and vein textures [

45,

46]. The pseudomorphic texture (

Figure 3a) represents mesh texture [

47,

48,

49] in which serpentine and magnetite phases statically replace olivine crystals, and yellow brown bastite replace orthopyroxene. The vein texture is represented by different sub-millimetric veins intersecting each other and crisscrossing the pseudomorphic texture [

45,

46].

In the Pietrapica serpentinites, the protolith minerals are olivine, pyroxenes (either orthopyroxene and clinopyroxene) and spinel, whereas the secondary (i.e. metamorphic) minerals are serpentine, chlorite, magnetite, prehnite and amphibole. Olivine is locally recognizable in the core of serpentine + magnetite pseudomorphs in the mesh textures (

Figure 3b). Orthopyroxene is observed as fresh porphyroclasts as well as bastite pseudomorphs, which retain the prismatic habit of the original orthopyroxene (

Figure 3c); orthopyroxene also occurs as lamellae within clinopyroxene porphyroclasts. Clinopyroxene porphyroclasts are commonly rimmed by amphibole, which is interpreted as a tremolite-actinolite series based on optical characteristics (

Figure 3d). Spinel forms red-brown coloured, xenomorphic, holly leaf-shaped porphyroclasts defined as typical of porphyroclastic upper mantle peridotites [

50].

Serpentinites are crosscut by several types of veins, filled with various serpentine minerals (

Figure 3e). In some samples, kinked orthopyroxene is replaced by pseudomorphic amphiboles (

Figure 3f), which are interpreted as belonging to the tremolite-actinolite series based on optical characteristics. Clinopyroxene porphyroclasts are sub-euhedral and commonly surrounded by amphibole, which belongs to the tremolite-actinolite series based on its optical characteristics (

Figure 3g). Spinel forms red-brown coloured, xenomorphic, holly-leaf shaped porphyroclasts (

Figure 3h). Talc is detected in some of the studied samples (

Figure 3i) and is spatially associated with carbonate and serpentine veins (

Figure 3j).

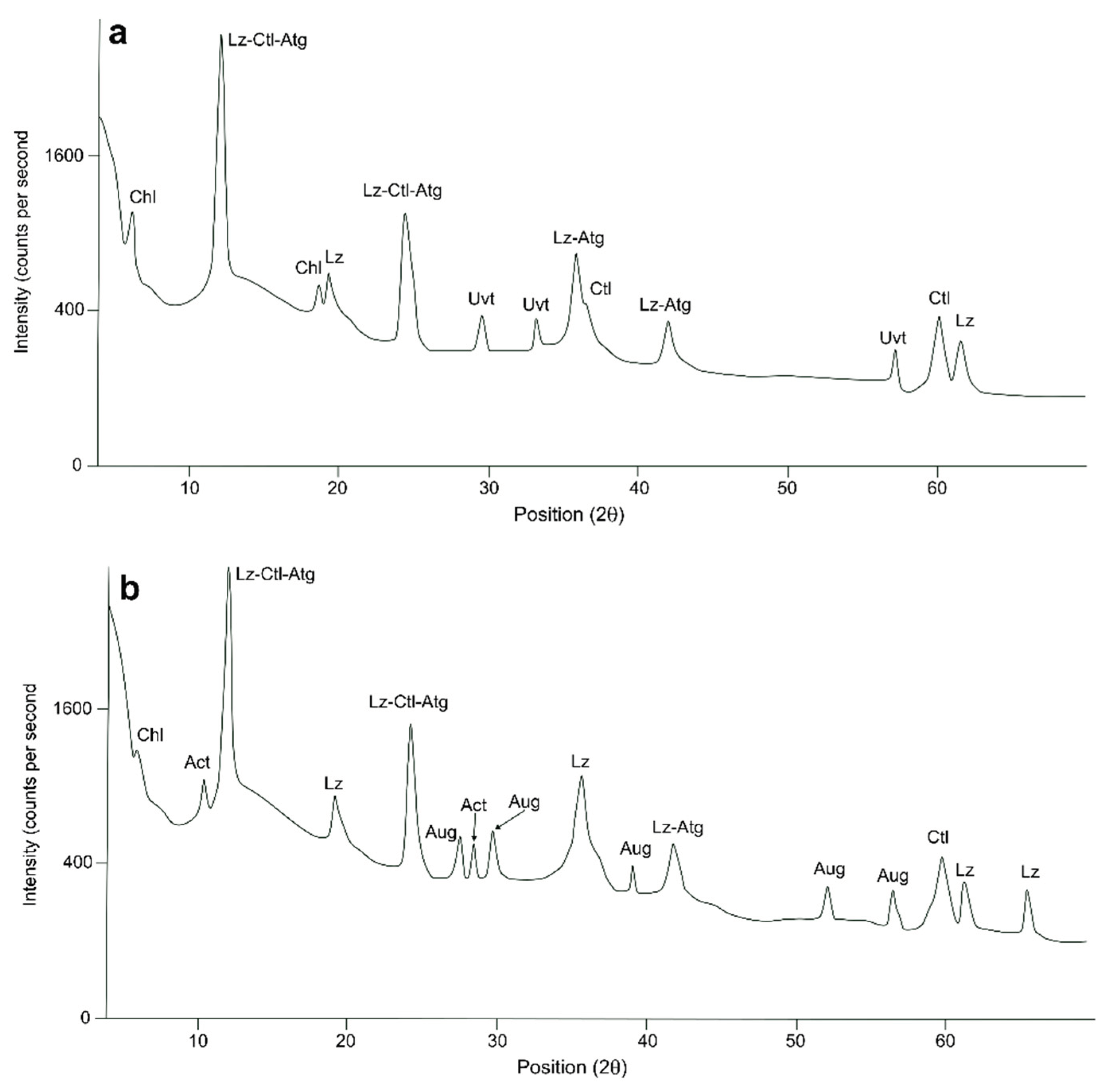

The results of our XRPD X-ray diffraction analysis have shown that the mineralogical phases of the serpentinite samples mainly include lizardite, antigorite, clino-crysotile, Cr-chlorite, magnetite, tremolite, actinolite, pyroxene and calcite. The most commonly occurring minerals are polymorphs of serpentine including lizardite (d = 7.27 Å), clino-crysotile (d = 7.32 Å), and antigorite (d = 7.23 Å). Amphibole minerals such as actinolite (d = 8.31 Å) and tremolite (d = 2.94 Å) were also detected in several samples (

Figure 4). The presence of uvarovite in some samples is likely the result of a Ca-metasomatic process, in which the addition of Ca destabilizes the iron stored in the iron-bearing minerals of the serpentinites (such as magnetite) favouring its formation [

52]. Uvarovite formation may also be related to degradation of ortho- and clinopyroxene phases in the rocks.

4. Discussion

The petrographic and mineralogical study of serpentinites from the Frido Unit shows that Mg silicates, mainly serpentine and secondarily olivine, can be used for carbonation purposes. The use of serpentine rocks for CO2 storage is an emerging technique in the field of carbon capture and storage (CCS). This technology aims to remove carbon dioxide (CO2) produced by industries and power plants and deposit it underground, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The objective of this preliminary work is to launch the idea for the suitability of natural analogue systems using different approaches in various sites in the Pollino area (Southern Apennines). Recent work has obtained precise estimates of the content of carbon-bearing minerals that host atmospheric CO

2. Wilson et al. [

53] have shown that the amount of atmospheric CO

2 that has been bound in mineral form can be estimated from the Rietveld results for weight-percent abundance of hydrated magnesium carbonates. Wilson et al. [

53] carried out a study on serpentinite-rich sterile samples from Clinton Creek and Cassiar (Australia) and it has been estimated that a total of 164,000 ± 16,400 tons of CO

2 are bound within the Clinton Creek sterile pile (applying a relative error of 10% corresponding to 4.36 wt. % of hydro magnesite). However, this high degree of accuracy is difficult to obtain with other quantitative phase analysis methods [

53].

Large-scale application of mineral sequestration can represent high potential to fund remediation of mine sites and to provide reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. This refining technique could be applied to serpentine samples allowing for improved characterization of many tailings’ materials and quantification of CO

2 sequestration. Recent work by [

54] have shown the importance of mineralogical and petrographic studies to improve the mineral carbonation process. Initially, it was thought that the hypothesis that lizardite is more suitable for carbonation than antigorite was not correct, but it was, nevertheless, on the right track, because features that positively influence the suitability of a serpentinite rock for mineral carbonation are more common in lizardite than in antigorite. In contrast, amphiboles and pyroxenes have already been reported to be unsuitable for mineral carbonation [

55,

56].

Characteristics that influence the suitability of a serpentine such as mineralogical structure, parent rock, and subsequent rock transformation through metamorphosis must be considered when working with carbonation processes. These integrated studies can be useful for selecting injection sites on a field scale and potential additives or pre-treatment strategies to optimize carbonation reactions of Mg-silicate metals. Therefore, the petrographic and mineralogical study of natural occurring serpentinite rocks hosted in ophiolite sequences cropping out in the southern Apennine can serve as a starting point for the study and analysis of natural materials that can be used for CO2 storage. It is important to continue research in this area at a detailed extent to find more efficient and sustainable ways to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate climate change.

5. Conclusions

The prospects of using serpentine rocks for CO2 storage are promising. The market for CO2 storage and sequestration that is developing in parallel with the European regulated market is an economically promising sector. The growth of this market is based on the prospects for the development of capture and storage technologies over the next decade. CO2 storage in rocks, particularly in serpentine rocks, is important for several reasons:

- −

First, this technique allows some of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to be isolated and injected into deep reservoirs reducing the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, and hence helping to mitigate the greenhouse effect and global warming. CO2 storage can facilitate the energy transition process.

- −

As we move toward cleaner energy sources, CO2 storage can help manage residual CO2 emissions.

- −

Deep reservoirs that were previously occupied by gas and/or oil can be used for CO2 storage since these reservoirs are able to naturally contain gas and fluids, making them suitable for CO2 storage.

Some projects are exploring the possibility of turning CO2 into rock, a process that could offer a long-term and safe method of storage. However, it is important to note that these techniques are still under development and require further research to be implemented on a large scale. Each contribution aimed at providing detailed geological and petrographic features of natural outcrops may add a new piece of information towards sustainable solutions for greenhouse gas reduction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Giovanna Rizzo, Yildirim Dilek and Rosalda Punturo; Data curation, Roberto Buccione; Formal analysis, Roberto Buccione and Marilena Dichicco; Methodology, Marilena Dichicco; Supervision, Giovanna Rizzo, Yildirim Dilek and Rosalda Punturo; Writing – original draft, Roberto Buccione; Writing – review & editing, Giovanna Rizzo.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hegerl, G.C.; Crowley, T.J.; Hyde, W.T.; Frame, D.J. Climate sensitivity constrained by temperature reconstructions over the past seven centuries. Nature 2006, 440, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, G.L.; Royer, D.L.; Lunt, D.J. Future climate forcing potentially without precedent in the last 420 million years. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 14845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Global Carbon Budget. With major processing by Our World in Data. “Annual CO₂ emissions”. Global Carbon Project. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oelkers, E.H.; Gislason, S.R.; Matter, J. Mineral Carbonation of CO2. Elements 2008, 4, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H. Carbon Sequestration via Mineral Carbonation: Overview and Assessment. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, P.; Adegbulugbe, A.; Christophersen, Ø.; Ishitani, H.; Moomaw, W.; Moreira, J. Introduction. In IPCC special report on carbon dioxide capture and storage; Jochem, C.E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, F.; Lackner, K. Carbon dioxide sequestering using ultramafic rocks. Environ. Geosci. 1998, 5, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijgen, W.J.J.; Comans, R.N.J. Carbon dioxide sequestration by mineral carbonation; Report Number ECN-C-03-016; Energy research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN): Petten, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, P.J.; Schmidt, A.D.; Wittbrodt, J.; Stelzer, E.H.K. Reconstruction of zebrafish early embryonic development by scanned light sheet microscopy. Science 2008, 322, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacinska, A.M.; Styles, M.T.; Bateman, K.; Hall, M.; Brown, P.D. An Experimental Study of the Carbonation of Serpentinite and Partially Serpentinised Peridotites. Frontiers in Earth Science 2017, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, K.S. A guide to CO2 sequestration. Science 2003, 300, 1677–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, K.S.; Wendt, C.H.; Butt, D.P.; Joyce, E.L.; Sharp, D.H. Carbon dioxide disposal in carbonate minerals. Energy 1995, 20, 1153–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, I.M.; Wilson, S.A.; Dipple, G.M. Serpentinite Carbonation for CO2 Sequestration. Elements 2013, 9, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifritz, W. CO2 disposal by means of silicates. Nature 1990, 345, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevenhoven, R.; Fagerlund, J. Mineralization of carbon dioxide (CO2). In Developments and innovation in carbon dioxide (CO2) capture and storage technology; Woodhead Publishing, 2010; pp. 433–462. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, M.T.C.; Rizzo, G. Pumpellyite veins in the meta-dolerite of the Frido Unit (Southern Apennines- Italy). Periodico di Mineralogia 2012, 81, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Laurita, S.; Prosser, G.; Rizzo, G.; Langone, A.; Tiepolo, M.; Laurita, A. Geochronological study of zircons from continental crust rocks in the Frido Unit (southern Apennines). Int. J. Earth Sci. (Geol Rundsch) 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadea, P. I carbonati delle rocce metacalcaree della Formazione del Frido della Lucania. Ofioliti 1976, 1, 431–465. [Google Scholar]

- Beccaluva, L.; Maciotta, G.; Spadea, P. Petrology and geodynamic significance of the Calabria-Lucania ophiolites. Rend Soc It Miner Petrol 1982, 38, 973–987. [Google Scholar]

- Dichicco, M.C.; Laurita, S.; Sinisi, R.; Battiloro, R.; Rizzo, G. Environmental and Health: The Importance of Tremolite Occurrence in the Pollino Geopark (Southern Italy). Geosciences 2018, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichicco, M.C.; Paternoster, M.; Rizzo, G.; Sinisi, R. Mineralogical Asbestos Assessment in the Southern Apennines (Italy): A Review. Fibers 2019, 7(3), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloise, A.; Ricchiuti, C.; Giorno, E.; Fuoco, I.; Zumpano, P.; Miriello, D.; Apollaro, C.; Crispini, A.; De Rosa, R.; Punturo, R. Assessment of naturally occurring asbestos in the area of Episcopia (Lucania, Southern Italy). Fibers 2019, 7(5), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punturo, R.; Ricchiuti, C.; Giorno, E.; Apollaro, C.; Miriello, D.; Visalli, R.; Pinizzotto, M.R.; Cantaro, C.; Bloise, A. Potentially toxic elements (PTES) in actinolite serpentinite host rocks: a case study from the Basilicata region (Italy). Ofioliti 2023, 48(2), 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, G.; Sansone, M.T.C.; Perri, F.; Laurita, S. Mineralogy and petrology of the metasedimentary rocks from the Frido Unit (southern Apennines), Italy. Periodico di Mineralogia 2016, 85, 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, G.; Laurita, S.; Altenberger, U. The Timpa delle Murge ophiolitic gabbros, southern Apennines: Insights from petrology and geochemistry and consequences to the geodynamic setting. Period. Mineral. 2018, 87, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cello, G.; Mazzoli, S. Apennine tectonics in southern Italy: A review. Journal of Geodynamics 1999, 27, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadea, P. Continental crust rock associated with ophiolites in Lucanian Apennine (Southern Italy). Ofioliti 1982, 7, 501–522. [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi, G.; Amore, F.O.; Ciampo, G.; De Capoa, P.; Miconnét, P.; Perrone, V. Il Complesso Liguride Auct.: Stato delle conoscenze attuali e problemi aperti sulla sua evoluzione Pre-Appenninica ed i suoi rapporti con l’Arco Calabro. Memorie della Società Geologica Italiana 1988, 41, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, S.D. Structure, kinematics and metamorphism in the Liguride Complex, Southern Apennine, Italy. Journal of Structural Geology 1994, 16, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, C.; Tortorici, L. Tectonic role of ophiolite-bearing terranes in building of the Southern Apennines orogenic belt. Terra Nova 1995, 7, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampfli, G.M.; Borel, G.D.; Marchant, R.; Mosar, J. Western Alps geological constraints on western Tethyan reconstructions. Journal Virtual Explorer 2002, 8, 77–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Buccione, R.; Dichicco, M.; Punturo, R.; Mongelli, G. Petrography, Geochemistry and Mineralogy of Serpentinite Rocks Exploited in the Ophiolite Units at the Calabria-Basilicata Boundary, Southern Apennine (Italy). Fibers 2023, 11(10), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, S.D. The Liguride Complex of Southern Italy-a Cretaceous to Paleogene accretionary wedge. Tectonophysics 1987, 142, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, C.; Tansi, C.; Tortorici, L.; De Francesco, A.M.; Morten, L. Analisi geologico-strutturale dell’Unità del Frido al Confine Calabro-Lucano (Appennino Meridionale). Mem. Soc. Geol. It. 1991, 47, 341–353. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, C.; Tortorici, L. Evoluzione geologico-strutturale dell’Appennino Calabro- Lucano. In: F.; Ghisetti, C. Monaco, L. Tortorici and L. Vezzani. Strutture ed evoluzione del settore del Pollino (Appennino Calabro-Lucano). Università degli Studi di Catania, Istituto di Geologia e Geofisica. Guida all’escursione 1994, 9–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, M.T.C.; Rizzo, G.; Mongelli, G. Mafic rocks from ophiolites of the Liguride units (Southern Apennines): petrographical and geochemical characterization. International Geology Review 2011, 53, 130–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilek, Y.; Furnes, H. Ophiolite genesis and global tectonics: Geochemical and tectonic fingerprinting of ancient oceanic lithosphere. Geological Society of America Bulletin 2011, 123((3–4)), 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilek, Y. and Furnes, H. Ophiolites and their origins. Elements 2014, 10(2), 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.M.; Wilson, R.C.L.; dos Reis, R.P.; Whitmarsh, R.B.; Ribeiro, A. The Western Iberia Margin: A geophysical and geological overview. In: Whitmarsh, R.B.; Sawyer, D.S.; Klaus, A.; and Masson, D.G. (Eds.), 1996, Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, 149.

- Di Leo, P.; Schiattarella, M.; Cuadros, J.; Cullers, R. Clay mineralogy, geochemistry, and structural setting of the ophiolite-bearing units from southern Italy: a multidisciplinary approach to assess tectonics history and exhumation modalities. Atti Ticinensi di Scienze della Terra 2005, 10, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, F.; Belviso, C.; Finizio, F.; Lettino, A.; Fiore, S. Carta geologica delle Unità Liguridi dell’area del Pollino (Basilicata): nuovi dati geologici, mineralogici e petrografici. Regione Basilicata-Dipartimento Ambiente, Territorio e Politiche della Sostenibilità. Ed. S. Fiore 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici, L.; Catalano, S.; Monaco, C. Ophiolite-bearing mélanges in southern Italy. The Journal of Geology 2009, 44, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadea, P. Calabria-Lucania ophiolites. Bollettino di Geofisica Teorica ed Applicata 1994, 36, 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ricchiuti, C.; Pereira, D.; Punturo, R.; Giorno, E.; Miriello, D.; Bloise, A. Hazardous elements in asbestos tremolite from the Basilicata region, southern Italy: A first step. Fibers 2021, 9(8), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, M.T.C.; Prosser, G.; Rizzo, G.; Tartarotti, P. Spinel – peridotites of the Frido Unit ophiolites (Southern Apennines – Italy): evidence for oceanic evolution. Periodico di Mineralogia 2012, 81, 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, M.T.C.; Tartarotti, P.; Prosser, G.; Rizzo, G. From ocean to subduction: the polyphase metamorphic evolution of the Frido Unit metadolerite dykes (Southern Apennine, Italy). In: (Eds.) Guido Gosso, Maria Iole Spalla, and Michele Zucali, Multiscale structural analysis devoted to the reconstruction of tectonic trajectories in active margins, Journal of the Virtual Explorer, Electronic Edition 2012.

- Wicks, F.J.; Whittaker, E.J.W. Serpentine texture and serpentinization. Canadian Mineralogist 1977, 15, 459–488. [Google Scholar]

- Wicks, F.J.; Whittaker, E.J.W.; Zussman, J. Idealized model for serpentine textures after olivine. Canadian Mineralogist 1977, 15, 446–458. [Google Scholar]

- Prichard, H.M. A petrographic study of the process of serpentinization in ophiolites and the ocean crust. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1979, 68, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, J.C.C.; Nicolas, A. Textures and fabric of upper-mantle peridotites as illustrated by xenoliths from basalts. Journal of Petrology 1975, 16, 454–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siivola, J.; Schmid, R. List of Mineral Abbreviations - Recommendations by the IUGS Sub commission on the Systematics of Metamorphic Rocks 2007, 12.

- Plümper, O.; Beinlich, A.; Bach, W.; Janots, E.; Austrheim, K. Garnets within geode-like serpentinite veins: Implications for element transport, hydrogen production and life-supporting environment formation. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2014, 141, 454–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.A.; Raudsepp, M.; Dipple, G.M. Verifying and quantifying carbon fixation in minerals from serpentine-rich mine tailings using the Rietveld method with X-ray powder diffraction data. American Mineralogist 2006, 91, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavikko, S.; Eklund, O. The significance of the serpentinite characteristics in mineral carbonation by “the ÅA Route”. International Journal of Mineral Processing 2016, 152, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, S.; Eklund, O. Suitability of Finnish mine waste (rocks and tailings) for mineral carbonation. Proceedings of ECOS 2014 — 27th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems, Turku, Finland, 15–19 June 2014; p. 244. [Google Scholar]

- Byggmästar, P. Karbonering av mafiska mineral i amfiboliter; Åbo Akademi University: Turku, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).