1. Introduction

Nothing within our body emerges de novo, isolated from the evolutionary history of life. Life conserves its past, and novel developments often build upon ancient mechanisms that nature has retained rather than discarded. According to this evolutionary rationale, major advancements do not arise from spontaneous random mutations, but instead from the reactivation of mechanisms and programs from earlier evolutionary periods.

The absence of homologous models for cancer development in invertebrates and lower vertebrates has left numerous unanswered questions about human cancer. For instance, what evolutionary circumstances and environmental factors promote cell alteration and propel altered cell phenotypes toward malignancy? To what extent is genome reprogramming involved in malignant transformation, and where does the point of no return lie?

Several researchers like Shapiro (2021) (1) understood the implementation of evolutionary principles in cancer and believed that there is now widespread acceptance of cancer as an evolutionary disease. However, they thought that tumors evolve somatically, transforming themselves from benign hyperplasia to malignant growth, which is not entirely accurate. Nevertheless, over the last 20 years, researchers such as Boveri, Erenpreisa, Craig, Ravegnini et al., and Chen et al. (2-5) recognized that cancer progression is an active process of biological self-transformation triggered by chemical and physical injuries. Concerning the natural history of cancer, Shapiro considered malignancy as a "result of (re)programming imprinted through evolution to cope with DNA damage and stored in the evolutionary memory of the genome."

In 2023, the Khan Academy similarly asserts that genomic-damaged cells typically identify such damage and attempt to repair it. Should the damage remain irreparable, the cell initiates apoptosis. Generally, the failure of defective cells to undergo apoptosis is believed to be an indicator of defective DNA repair and a precancerous cell state, potentially leading to cancer (6).

Conclusively, the cell-of-origin for cancer must be a severely damaged NG germline cell or germline stem cell (GSC) with irreparable DNA DSB defects, capable of inducing malignant transformation in DSCD cells with the assistance of archaic MGRS mechanisms (see

Table 1). According to recent research by Gillespie et al. (2023)

(7) on

oncogenic germline transformation, tumor cancer stem cells (CSCs) are presumed to harbor similar mechanisms that enhance DNA repair efficiency compared to the somatic highly proliferative bulk, thus facilitating improved repair of double-strand breaks induced by radiotherapy in tumor CSCs. Many researchers, however, narrow their focus to repair mechanisms, emphasizing increased expression and splicing fidelity of DNA repair genes

(8).

Dysfunctional tetraploid DSCD cells

DSCD cells can survive irreparable DNA DSB damage, awaiting repair, genome reconstruction, and the restoration of function: non-gametogenic germline renewal, genomic integrity, and the resumption of stem cell generation. Human DSCDs can enter a state of transient quiescence or slow cycling within their niche. However, they can exit the quiescence niche and continue to proliferate through aberrant symmetric cell cycles (9-11). Environmental changes inside the niche or exposure to more oxygenated regions can induce increased proliferation, causing DSCD progeny to become fusible and form cell aggregates (MGRS). This is evidence that, under the influence of environmental changes, DSCD progeny is ready to initiate a repair process. However, in the absence of a suitable multicellular repair mechanism, human DSCD progeny activates an ancient reprogramming mechanism through multinucleated genome repair syncytia (MGRS) driven by genes from the ancestral genome compartment.

Thus, DNA damage repair and genome reprogramming proceed in a unicellular manner under the control of the ancient regulatory network (aGRN) that transforms the precancerous high-risk DSCD phenotype into a cancerous ACD phenotype, with stemness, differentiation potential, and the ability to initiate germ and soma (G+S) life cycles of premetazoan imprinting. The non-gametogenic germline of cancer contains all the hallmarks of the ancestral Urgermline, producing naive cancer stem cells (CSCs) as germline stem cells (9-11).

It is becoming increasingly clear that the conversion of "unhealthy" DSCD cells to malignancy depends on environmental changes in tissue and stem cell niches that favor malignant transformation. Genome reprogramming through hyperpolyploidization is widespread in carcinogenesis and tumorigenesis. At least 90% of undifferentiated colorectal and glioblastoma carcinomas have polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs) as genome repair structures (12). PGCCs are responsible for oncogenic transformation and the generation of CSCs (10).

Evolutionary Cancer Cell Biology (ECCB), recently introduced as a significant advancement in the field of carcinogenic and tumorigenic cancer cell biology (9-11,13) is based on the recognition that human cancer represents a shift to a lower level of cell organization that evolved hundreds of millions of years ago in the common ancestor of amoebozoan, metazoan, and fungi (AMF). Amoebozoa has recently been classified within the stable Amorphea group, recognized as one of the eight eukaryotic supergroups (14). This evolutionary cell orgsanization level has been consistently utilized by pre-metazoans, contemporary protists, and cancer cells alike.

According to ECCB, cancer cells and CSCs possess a hybrid genome comprising numerous genes and programs of premetazoan origin. The evolutionary process involved a competition between the remaining functional multicellularity genes (MG), which persist after malignization, and the ancient AMF genes from the premetazoan era (2350-1750 Mya), promoting unicellularity. It is essential to differentiate these primitive AMF UG genes from the UG genes discussed by Trigos et al. (15-17), which evolved during the transitional period before 650 Mya. The latter genes primarily function as repression and antisuppression genes, regulating the suppression of the germ and soma life cycle and assuming roles in tumor suppression (TSG) and oncogenes in metazoans. Consequently, ECCB conceptualizes cancer as a conflict between two distinct cellular organizational systems and their regulatory networks (GRNs) conserved within the hybrid genome of cancer.

As a consequence, cancer essentially operates within the lower level of cell organization, originating from an oxygen-sensitive non-gametogenic (NG) germline (Urgermline), the progenitor of all stem cell lineages, and a somatic, oxygen-resistant cancer cell line. This dual germ and soma cell system evolved from the AMF ancestor, shared by cancer and protist pathogens such as Entamoeba and Giardia (9-11,13,18-20), and is conserved in the archaic genome compartment of humans and metazoans. Certain genes and programs from this ancestral compartment also regulate vital non-cancerous functions, including various embryonic processes, stemness and differentiation, cell plasticity, and polyploidization.

In the evolutionary ECCB perspective, malignization and carcinogenesis occur from high-risk DSCD cells, deeply homologous to the DSCD cells of protists (

Table 1). According to ECCB, the cell biology of cancer NG cancer germlines and cancer stem cell lineages essentially corresponds to the cell biology of the Urgermline and is under the control of the ancient gene regulatory network (aGRN). The

hallmarks of cancer largely correspond to the hallmarks of the Urgermline and all NG germlines that evolved from the Urgermline.

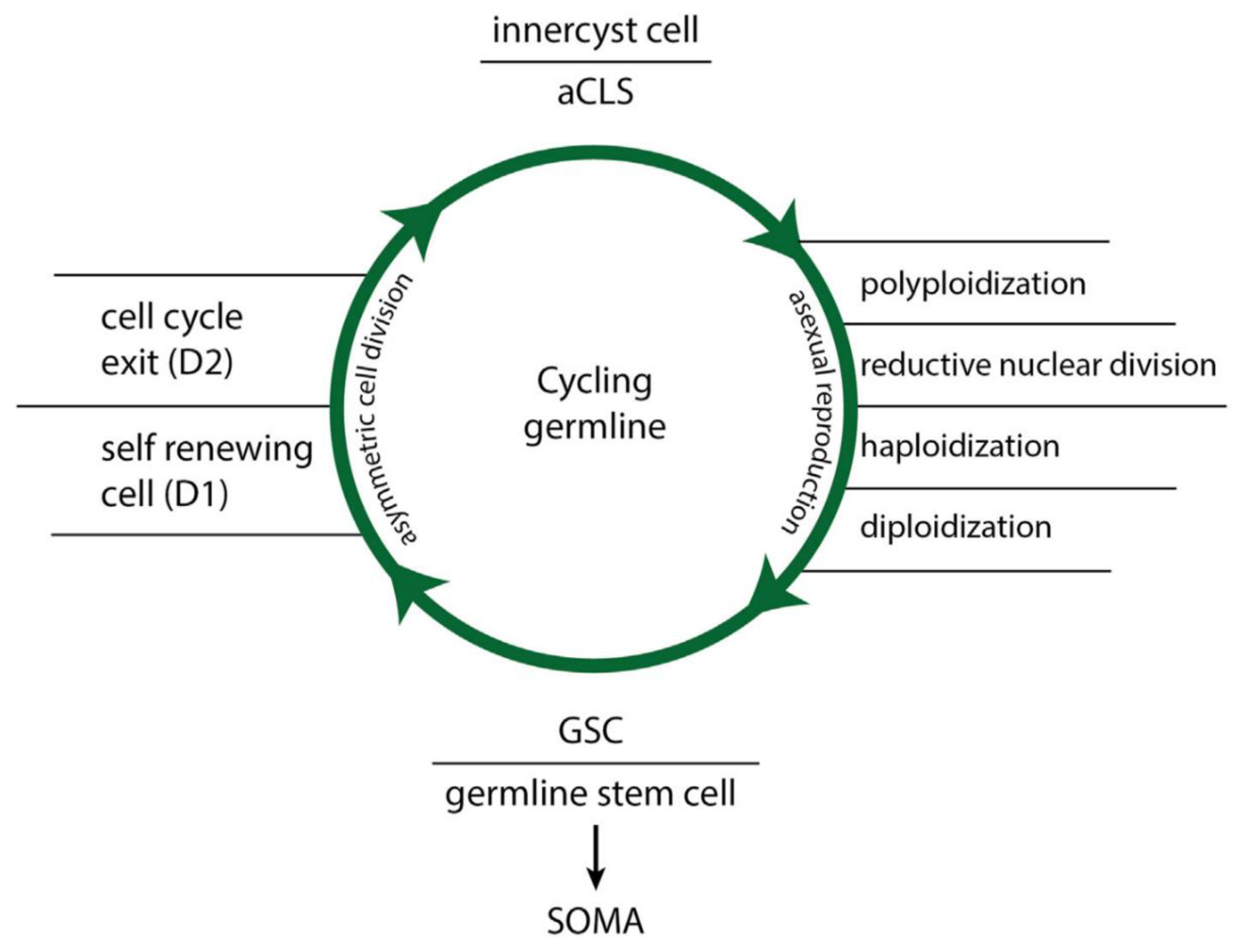

The hallmarks of functional and dysfunctional NG germlines

Functional NG germline features are: (i) continuous cell proliferation, (ii) conversion of asymmetric cell cycling with asymmetric cell division (ACD phenotype) to symmetric cell cycling and symmetric cell division (SCD phenotype), (iii) transformation of soma to germ cells (SGT aka EMT) and germ-to-soma cells (GST aka MET), (iv) sensitivity to oxygen contents of more than 5.7%-6.0% O2 (archaic hypoxia ranges, AMF hypoxia), and (v) the capacity of ACD phenotypes to form stem cells via polyploidization-depolyploidization cycles and generation of diploid/haploid progeny. These reproductive polyploid cycles for stem cell production, previously described (21,22), are now referred to as functional “ polyploidy“ (Fig.2).

The hallmarks of dysfunctional NG germlines exposed to oxygen ranges exceeding 6.0% O2 as occurring in tissue and the bloodstream are: (i) irreversible DNA double-strand break defects (DNA DSBs), (ii) loss of stemness and cell differentiation ability, (iii) cell and mitotic senescence, (iv) senescence bypass, (v) proliferation by defective symmetric cell division (DSCD phenotype) through amitosis, tetraploidization, and binucleation, (vi) the ability of DSCD cells for homotypic cell and nuclear fusion and the formation of multinucleated genome repair syncytia MGRS, (vii) DNA repair and genome reprogramming through hyperpolyploidization cycles, and (viii) the formation of diploid/haploid progeny and cellularization to buds and spores, generating functional stem cells and new germline clones. This type of tetraploidization of DSCD cells in non-cancerous and cancerous germlines and stem cell lineages is now referred to as dysfunctional low-grade polyploidy.

Figure 2.

Functional

“cystic polyploidy“ through polyploidization- depolyploidization cycles forming in

Entamoeba histolytica / E. invadens 4 polyploid nuclei, which give rise during ex-cystation to 16 haploid stem cell progenitors, and in E.coli to 8 polyploid nuclei, 16 diploid daughter cells and 32 stem cell progenitors. (From V.F. Niculescu, Cancer genes and cancer stem cells in tumorigenesis: Evolutionary deep homology and controversies, Genes & Diseases,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2022.03.010 (CC BY-NC-ND license)

(11).

Figure 2.

Functional

“cystic polyploidy“ through polyploidization- depolyploidization cycles forming in

Entamoeba histolytica / E. invadens 4 polyploid nuclei, which give rise during ex-cystation to 16 haploid stem cell progenitors, and in E.coli to 8 polyploid nuclei, 16 diploid daughter cells and 32 stem cell progenitors. (From V.F. Niculescu, Cancer genes and cancer stem cells in tumorigenesis: Evolutionary deep homology and controversies, Genes & Diseases,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2022.03.010 (CC BY-NC-ND license)

(11).

In the present paper, we investigate whether the multinucleated genome repair syncytia (MGRS) repair structures of protists also contain a dysfunctional cystic polyploidy phase, as suggested by the work of Krishnan and Gosh from 2019 (22). We are also exploring whether the dysfunctional cystic polyploidy phase also occurs in cancer (aCLS cancers), as previously assumed (21, 23). Additionally, we seek to clarify to what extent polyploidy variants occurring in the heart and liver represent functional or dysfunctional low- and high-grade polyploidy and how the puzzle of evolutionary polyploidy in lower and higher cell organization systems can be unraveled.

In contrast to previous theories on the atavistic origin of cancer (24-28) and Jinsong Liu's strange theory on the origin of polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCC) and the embryogenic origin of cancer (29,30), we aim to consolidate, with the present work, our ECCB view of cancer as a shift to a lower system or cellular organization directed and controlled by ancestral genes, gene modules, and gene regulatory networks from the AMF compartment of the human genome. We also report on similarities and differences in molecular senescence and senescence evasion in dysfunctional symmetric cell division (DSCD) cells and on the compartmentalization of the metazoan genome. But for now, here are a few words about the cystic polyploidy.

Functional and dysfunctional cystic polyploidy in protists

Protist MGRSs are formed from dysfunctional DSCDs that lack the ability to sustain asymmetric cell cycles, encystation, and polyploid cycles required for generating stem cells. Instead, they exhibit continuous proliferation through defective symmetric cell cycling (DSCD) and binucleated tetraploid cell cycles. In response to inductive environmental conditions, DSCDs cease proliferation, become fusible, and undergo fusion to generate MGRS syncytia.

Included DSCD nuclei initiate a low-grade polyploidization phase (phase I) up to 8n (in E. histolytica) or 16n polyploidy (in E. coli) (22), similar to normal cyst polyploidization, from which defective DSCD cells are usually kept away. The checkpoint that typically prevents the formation of non-viable defective cysts from DSCDs is canceled within the MGRSs. By enabling defective polyploidization/haplodization cycles and removing the natural encystation and polyploidization barrier for defective germline cells, the DNA copy number or DNA mass in MGRS is increased by a factor of 8 (in E. invadens) or 16 (in E. coli).

In a second phase of hyperpolyploidization, numerous defective daughter nuclei undergo nuclear fusion, forming extremely hyperpolyploid giant nuclei (>128n/256n). They repair DNA DSB defects through defective DNA parts excision, reconstruct DNA architecture, regain genome integrity, and form numerous functional daughter nuclei. These cellularize into viable spores and buds, forming new germline clones and stem cells capable of restarting the normal dual life cycle of protists .

2. Ancient genome compartments and evolutionary adaptation

In a recent paper on compartmentalized genome evolution, Frantzekakis et al. (31) present current models of genome evolution and different genome architectures, delineating characteristics of one-/two-/multi-compartment genome characteristics. The original two-speed hypothesis encompasses two different aspects: (1) the presence of physical genomic compartmentalization and (2) the more rapid evolution of genes residing in one of these compartments.

The ECCB adheres to this concept, acknowledging that multicellular genomes include deep archaic genes responsible for overall cellular functionality, cell cycling, and mitosis. In addition to (i) this archaic genome compartment, which evolved more than 2300 million years ago (Mya), the human genome comprises (ii) an ancestral genome compartment containing premetazoan genes, gene modules, and an ancient gene regulatory network (aGRN), all evolved by the common AMF ancestor, and (iii) a further genome compartment with genes from the transition era to multicellularity, including additional genes originating from early metazoans that aim to suppress the AMF lifestyle. Genes from the archaic, basic genome compartment remain persistently active across multicellular life, while those from the pre-metazoan and transitional genome compartments persist in a state of temporary repression, with facultative reactivation potential. Exceptions include stemness genes, which are active during embryogenesis, stem cell and tissue differentiation, and wound healing.

In cancer, the ancient gene regulatory network (aGRN) dominates over the multicellular gene regulatory network, suppressing numerous genes in the multicellular genome compartment and uploading germline genes from the pre-metazoan era. The non-gametogenic NG germline of cancer is fully controlled by the aGRN network, while somatic cancer cell lines exhibit less aGRN control and undergo somatic mutations.

These insights have emerged through advancements in Evolutionary Cancer Cell Biology (ECCB) in recent years (9-11,13). ECCB posits that the malignization of genomically damaged cells constitutes a programmed, non-mutational process developed to repair irreparable DNA double-strand break (DSB) damage and reprogram the dysfunctional genome of precancerous DSCDs, as well cancer germline cells and stemm cells (CSCs) damaged through excess oxygen or genotoxic stress. Similar to germline cells and germline stem cells of protists, human stem cells (HSCs) are sensitive to stress and oxygen contents corresponding to ancient AMF hyperoxia with more than 6.0% O2 content. Oxygen-rich tissues and the bloodstream can damage both HSCs and CSCs. Continuous proliferation under hyperoxic conditions (>6.0% O2) leads to irreparable DNA-DSB defects similar to those observed during aging.

3. Stem cells in aging and cancer: similarities and differences

In humans, age is a significant risk factor for cancer. According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the average age of cancer diagnosis is 66, and this trend of more diagnoses with advancing age applies to various types of cancer. The American Cancer Society (ACS) reports that 80.2 percent of cases occur in patients older than 55.

Smetana et al. (32) believe that age-altered stem cells can serve as the source of cancer formation. According to the researchers, aging involves genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, qualitative and quantitative changes in protein spectra, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communications (33-36).

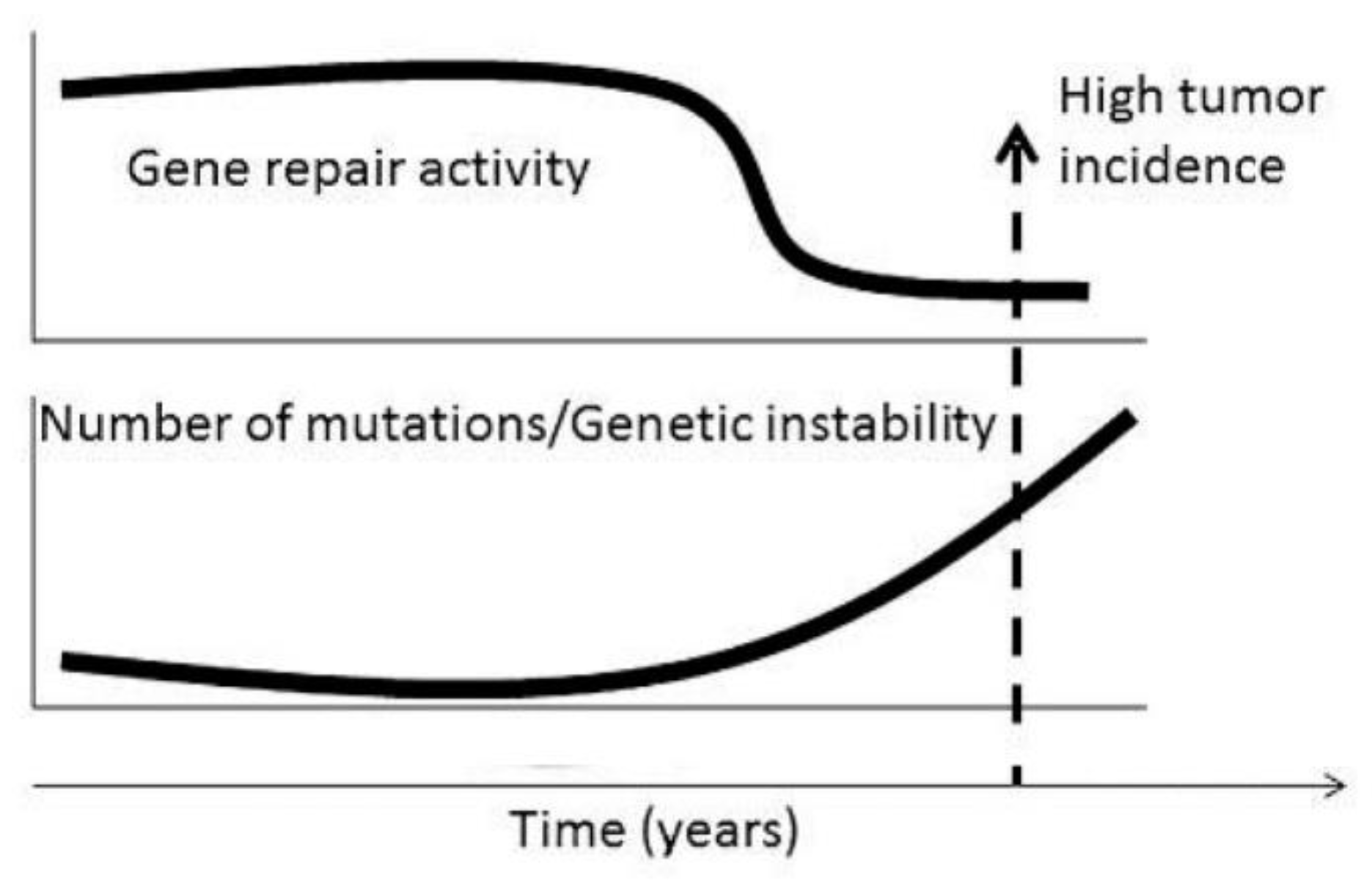

Figure 2.

Temporal coincidence between reduction of capacity for DNA repair, increased number of mutations increasing genetic instability, fertile age and beginning of the period ofhigh incidence of malignant tumors in humans (from Smetana et al 2016 (32) with the permission of Dr. George Delinasios, publisher of journal Anticancer Research).

Figure 2.

Temporal coincidence between reduction of capacity for DNA repair, increased number of mutations increasing genetic instability, fertile age and beginning of the period ofhigh incidence of malignant tumors in humans (from Smetana et al 2016 (32) with the permission of Dr. George Delinasios, publisher of journal Anticancer Research).

Researchers studying aging unanimously agree that the reduction in DNA gene repair activity may contribute to the selection of aberrant clones capable of malignization and tumor formation (37,38), similar to the DSCD cells described by our research. Genetically damaged stem cells exiting the niche can potentially initiate cancer when attempting to repair genomic damage. If the niche is not vacated, genomically damaged stem cells also increase their ability for cancer initiation due to the process of prolonged quiescence. Such genetic alterations can significantly contribute to the development of cancer-related symptoms and co-morbidities. Interestingly, almost 75% of "aging-specific genetic signatures" overlap significantly with those observed in cancer (39,40). In other words, many of the DNA-DSB damaged stem cells emerging during aging, are recognizable in cases of cancer by their altered genetic signature.

The findings discussed closely align with the evolutionary perspective of ECCB concerning the fate of DSCD cells and their malignant evolution (9-11,13) DSCD cells, identified as genome-altered stem cells, lose their stemness, differentiation ability, and potential for asymmetric cell division (ACD). They proliferate through defective symmetric cell cycles, giving rise to a population of potentially precancerous offspring. Malignant transformation occurs through hyperpolyploidization, and genome reprogramming, with or without cell and nuclear fusion.

3.1. Excess oxygen, oxydative stress and aging

According to the review by Berben et al. (41), cancer and aging share close connections. For instance, the incidence of cancer notably increases in older age groups, which are more prone to harboring cells with irreparable DNA DSBs, which occur in response to oxidative stress and a decline in the immune system's strength (42,43). Furthermore, they illustrate how chemotherapy can hasten the accumulation of DNA damage, potentially inducing premature aging (44). Moreover, individuals of the same age may exhibit distinct biological aging profiles.

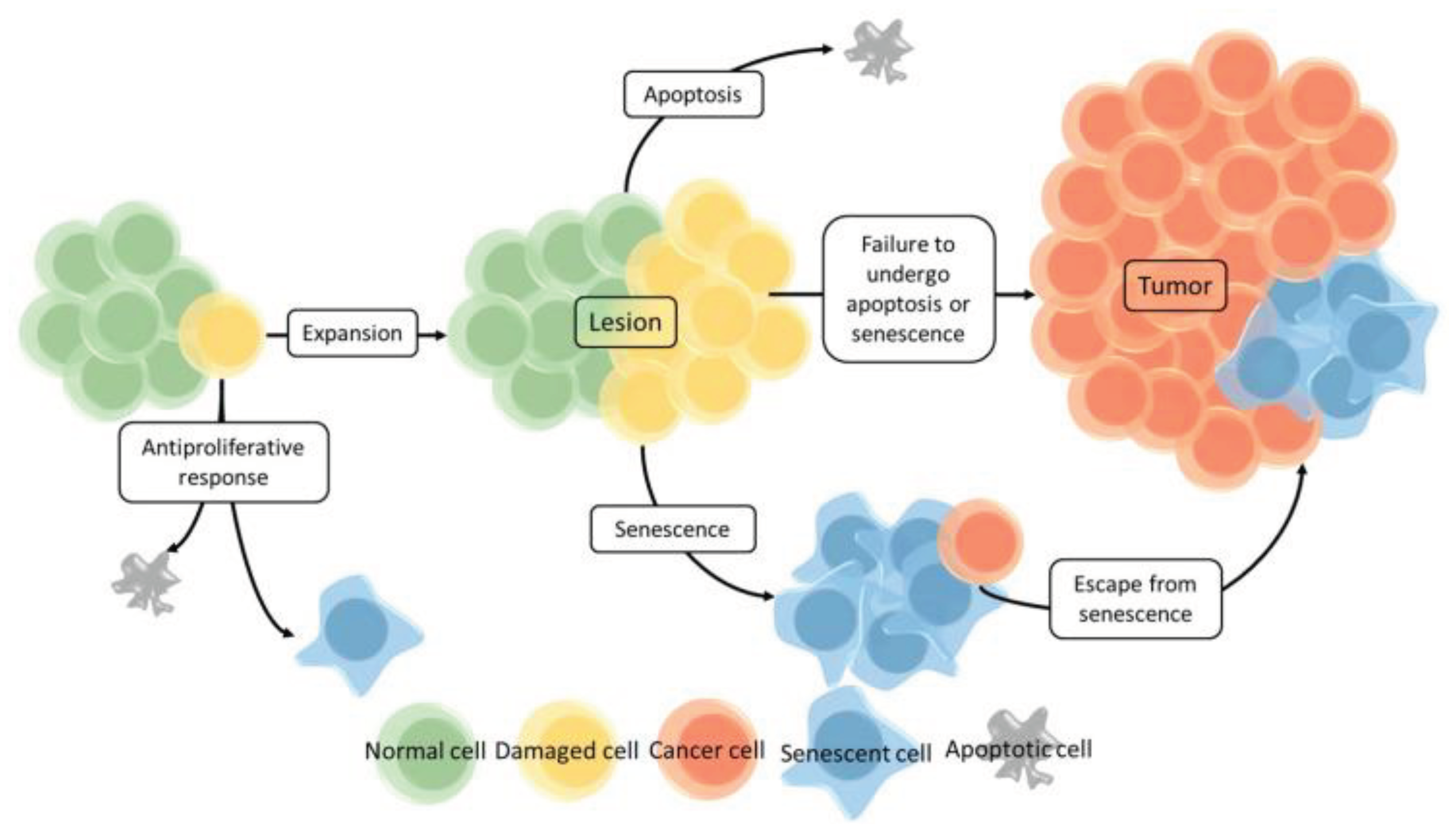

Senescent cells with oxidative DNA damage typically lose in aging their ability to proliferate in an uncontrolled manner and instead enter a state of senescence due to an anti-tumor mechanism. However, in cases where this mechanism fails, the cell retains the ability to replicate and proliferate, and can form a lesion. When the senescent program fails to activate, the lesion can grow, accumulate additional genetic aberrations, and eventually give rise to a malignant tumor. Even if cellular senescence has already been initiated, some cells can bypass this state and undergo malignant transformation

[45,46]. This underscores that passing through senescence does no equate to malignant transformation, and only a few senescent cells have the potential to become pre-cancerous. Why is this the case? Aren't all DSB-damaged cells genomically identical? Could it be that some senescent cells can be reprogrammed into cancer due to certain specific DNA damage patterns, while others undergo apoptosis? Future research will provide the answer.

Due to the deep homologous relationships with the Urgermline, the response of human non-gametogenic (NG) germline cells and stem cells to excess oxygen in aging and cancer reflects incidents and problems of the AMF ancestor. NG germline and stem cells of multicellular origin rely on the heightened sensitivity of the Urgermline to elevated oxygen levels, with more than 6.0% O2 known as archaic premetazoic hyperoxia or

AMF hyperoxia. Oxygen levels exceeding this threshold are considered hyperoxic for stem and germline cells. Therefore, human germline cells and cancer stem cells migrating from the hypoxic quiescence niche into well-oxygenated tissues and the bloodstream suffer irreparable DNA DSB damage for which they are not equipped

[10,37].

DNA DSB defects result in irreparable loss of function in both metazoans and protists. In humans and metazoans, cells with DNA damage may undergo a senescence program and culminate in apoptosis and cell death. However, unlike the fate of most DNA-damaged cells, some can bypass molecular checkpoints and transition to a dysfunctional symmetric cell division (DSCD) phenotype. This shift establishes itself as a potential precursor for cancer, ultimately leading to malignant reprogramming

[41,46].

3.2. Declining DNA-DSB repair ability

As highlighted by Smetana et al.

(32) researchers focusing on aging unanimously agree that when the capacity for DNA repair diminishes and weakens, the resulting genetic instability within stem cells becomes a contributing factor to cancer development

[36,47]. The association between longevity and enhanced gene repair capacity becomes evident when comparing shorter- and longer-living organisms

(48). Aging is consistently linked to a decline in gene repair capabilities. This is notably demonstrated in the case of DNA polymerase δ1, a critical enzyme for DNA replication and repair, whose expression significantly decreases with an individual's aging process. Similarly, the quantity of DNA DSBs and the time required for their repair are significantly influenced by aging

(49,50). Throughout the aging process, there's a substantial accumulation of acquired DNA defects, with robust genomic technologies revealing that 3,000-13,000 genes per genome can be affected

(51). The researchers emphasize that oxygen serves as the most significant exogenous and endogenous source of DNA defects. When DNA errors are not accurately and efficiently repaired, they can contribute to the development of various significant issues, including cancer. These findings underpin the ECCB's perspective.

Nevertheless, a certain frequency of errors during DNA maintenance and replication in the cell cycle is expected, and the cell employs enzymatic machinery for their correction. This includes processes like DNA methylation, acetylation, and histone acetylation, which influence the activity of numerous genes. Epigenetics' role in deactivating gene repair is exemplified in gastrointestinal tumors and triple-negative breast cancer. The poor prognosis for patients is associated with the deactivation of the breast cancer 1 (BRCA1) gene through methylation (52,53). BRCA1 plays a role in DNA repair. The synergy between genetic instability induced by reduced activity in gene repair mechanisms and epigenetic mechanisms triggered, for instance, by excessive production of reactive oxygen species, may play a significant role in cancer initiation and progression (54).

3.3. Irreparable DNA DSB defects require genome reprogramming

These discoveries regarding precancerous genome state are intriguing. However, the conclusions drawn about the causes of malignant changes remain incomplete because the evolutionary research findings from the ECCB had not yet been incorporated at that time. We concur with the notion that genomically damaged stem cells can potentially drive cancer-initiating cell pools toward malignancy. When the process of eliminating such genetically unstable stem cells from the niche fails, they persist, awaiting reprogramming.

It's also highly intriguing that very old healthy individuals possess "cancer-associated mutations" in their genome, yet these mutations remain silent and clinically irrelevant. This leads to the inference that many genome changes occurring in older individuals might not be inherently carcinogenic. Instead, they represent late molecular consequences of (age-related) DNA DSB damage that is not directly implicated in cancer emergence.

It is becoming increasingly evident that the stem cell pools carrying DNA DSB defects are not homogeneous; they vary in terms of their origin, their molecular alteration, the quantity and quality of DSB defects, and their potential to cause cancer. Some of these defective cells undergo programmed senescence and apoptosis, while others persist within their niche or migrate from the niche, perpetuating the malignant program.

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of of cell senescence, senescence exit, and malignization occurring in aging and cancer. From Berben et al. 10.3390/cancers13061400, 2021 (41) (CC BY 4.0) license.

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of of cell senescence, senescence exit, and malignization occurring in aging and cancer. From Berben et al. 10.3390/cancers13061400, 2021 (41) (CC BY 4.0) license.

While genetic instability, declining gene repair, and epigenetic inactivation of gene repair have long been recognized as crucial regulatory checkpoints for carcinogenesis, protist findings have revealed that premetazoans are also incapable of repairing severe DNA DSBs, leading to a loss of stemness and differentiation potential. Attempts to upregulate the gene activity of homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) genes in these organisms proved to be unsuccessful.

The ECCB demonstrates, however, that both cancer and protists, can repair resistant severe DNA DSB defects through hyperpolyploidization, with or whithout cell and nuclear fusion, and DSB excision. This mechanism is dormant in the premetazoan genome compartment of healthy, non-cancerous individuals but can be activated to reprogram the human genome in a premetazoan manner, leadind to PGCC cancers. On could posit that PGCC cancers result from a historically determined reprogramming process dating back to the end of the premetazoan era when non-viable transitional forms toward multicellularity needed reprogramming and revertion to the stable, preceding germ and soma life cycle of the AMF ancestor.

3.4. Genome reprogramming ocurs only in the hyperpolyploid nuclei of MGRSs and PGCCs and not in aging

Comparable to protists and premetazoan cells, human DSCD genomes can only be restored (reprogrammed) through hyperpolyploidization, either with or without prior cell and nuclear fusion, resulting in the formation of multinucleated genome repair syncytia (MGRS), known as PGCC or PGCC-like structures in cancer (9-11,13). In protists and tumors, the resulting hyperpolyploid nucleus can repair the unfunctional genome to ensure genomic integrity. Conversely, PGCC-like structures reprogram human DSCD genome into a lower organizational cell system leading to malignancy.

PGCCs are notably absent in healthy humans and mammals. In the last two decades, however, they have been identified in numerous types of cancer, coined as PGCC cancers or aCLS cancers (55). Nevertheless, owing to a lack of evolutionary understanding, PGCCs, mostly found in the advanced stages of cancer (metastases, recurrence), have been mislabeled as a novel form of cancer cell division entitled neosis (56-58) and embryogenic imprinting (29,30).

4. Physiological and non-physiological polyploidy variants as observed in amoebae are hallmarks of the Urgermline

As described in a previous paper on E. imvadens, there are both physiological and dysfunctional AMF polyploidy in amoebae, previously referred to as developmental and non-developmental polyploidy (59). We update and revise this knowledge. The results of this analysis show that all known forms of polyploidy (functional, dysfunctional, consecutive polyploidy and repair polyploidy) are already present in the ancestor of the AMF and are inherited by the descendant clades and cancer.

4.1. Physiological endopolyploidization in "healthy" NG germline (cystic polyploidy)

Endopolyploidization is an ancient mechanism developed in the reproductive cysts of the common AMF ancestor by healthy Urgermline cells. In protists, endopolyploidization is part of a reproductive polyploidization-haploidization cycle aimed at maintaining genomic integrity and forming germline stem cells (GSCs). Intact DNA repair mechanisms, such as homologous recombination (HR), in conjunction with endopolyploidization, repair genomic lesions and DNA DSB) defects, ensuring the integrity of the genome. Endopolyploidization-depolyploidization cycles occur through repeated endocycles (G1-S-G1) and reductive nuclear division (acytokinetic mitosis) to form polyploid, diploid, and haploid daughter nuclei. We introduce the term cystic polyploidy for this multi-stage process. As observed in amoebae, physiological endopolyploidization is limited to hypoxic ranges and appropriate environments (22,60,61). Cells that are not capable of physiological endopolyploidization and cystic polyploidy, such as somatic cells, can convert through germ-to-soma transition (GST) into germline clones with endopolyploidization potential.

4.2. Cystic polyploidy phase within genome repair syncytia (MGRS)

In cases where cells with DSCD are exposed to conditions favorable for homotypic cell fusion, they give rise to giant repair syncytia (MGRS), and their diploid nuclei undergo cycles of endopolyploidization/depolyloidization within the syncytia. However, it is noteworthy that these polyploidization-depolyploidization cycles are unable to restore genomic integrity and generate functional daughter nuclei. The dysfunctional daughter nuclei resulting from the intersyncytial cystic polyploidy phase, subsequently undergo a process of nuclear fusion and fuse to form hyperploid giant nuclei capable of restoring genomic architecture and forming multiple spores and buds. (10, 64) This cystic polyploidy phase serves to accumulate a critical DNA mass required for the process of genome reprogramming that takes place in the hyperpolyploid nuclei of MGRS.

4.3. Low-grad, non physiological polyploidy in severely damaged NG germline and stem cell lineages(dysfunctional polyploidy)

Cells bearing irreparable DNA DSB defects exhibit an incapacity to undergo endocycling, endopolyploidization, and stem cell generation. DSCD cells in protists cannot be experimentally induced to normal cystic polyploidy, even if surrounding somatic helper cells create hypoxic conditions for encystation (22).

4.3.1. Abortive endopolyploidization in defective cysts

If such defective germline cells are nevertheless induced to form cysts and endocycles, only incomplete endopolyploidization takes place, resulting in binucleated tetraploids (62) or trinucleated octoploids (63), which are not viable and are subject to cell death through lethal tetraploidy or octoploi dy.

4.3.2. Tetraploid cell proliferation through incomplete karyokinesis (acytokinetic mitosis) and premature cytokinsis

In living conditions characterized by ancestral hyperoxia, where the oxygen content exceeds 6.0%, binucleated and trinucleated DSCD cells demonstrate their capability for prolonged tetraploid proliferation. DSCD cells undergo defective cell cycles marked by incomplete karyokinesis [G1-S-G2-(M)-G1], aberrant multipolar mitosis, and become tetraploid, displaying both mature and immature nuclei, along with cytokinesis failure [G1-S-G2-M-G1] (premature cytokinesis) (65,66). These anomalies in the cell cycle are ascribed to the sustained proliferation of DSCD cells in tissue with oxygen contents above 6.0% O2.

4.3.3. Prolonged mitosis: polyploidization-depolyploidization cycles and ploidy reduction ability (tetraploid-diploid cell cycles)

When DSCD cells are induced to undergo prolonged mitosis by starvation, immature nuclei mature, and normal cytokinesis with diploidy occurs. However, upon the restoration of previous living conditions, the DSCD population reverts to proliferative tetaploidy and endomitotic cell cycles. Prolonged mitosis/ cytokinesis results in ploidy reduction and single cycles of depolyploidization and repolyploidization (4n>2n>4n). Nevertheless, the change between starvation and normal growth conditions can lead to a tetraploid-diploid proliferation sequence (4n>2n>4n>2n) (65,66).

4.3.4. Hyperpolyploidy by stress and ploidy reduction

In 1961 Diamond (67) first introduced amoebae from the hypoxic intestinal environment in synthetic hyperoxic culture media without bacteria or oxygen reducing microorganisms (axenic cultures), resulting in hyperpolyploidization.

Under severe nutritional, metabolic, and hyperoxic stress, amoebae develop irreparable DNA DSB defects and transition into a proliferative hyperpolyploid dysfunctional DSCD phenotype with more than 32-64 genome copies. Further proliferation in synthetic hyperoxic culture media progressively reduces hyperpolyploidy to a lower grade of polyploidization (65,66). This development suggests that the severe metabolic-oxidative stress to which the DSCD phenotype was subjected might induce significant genome changes counteracted by hyperpolyploidization. The gradual reduction of hyperpolyploidization over time could then represent an adaptive response of ploidy reduction.

5. Polyploidy in aging

5.1. Senescent low-grade polyploidy after transplantation: reversal, repair and reprogramming

Some years ago, Wang et al. (68) conducted an analysis of the progressive low-grade polyploidization in binucleated tetraploid and octoploid hepatocytes of the mammalian liver. Their findings demonstrated that polyploidy frequency increases with the aging process due to cellular stress, factors, oxygenic stress, and toxic stimulation, reaching approximately 40% in humans and around 90% in mice.

However, the high prevalence of senescent low-grade polyploids could be reversed through transplantation into young mouse livers. Senescent polyploids exhibited the capacity to rejuvenate into healthy diploids, a phenomenon referred to as senescent polyploidization reversal, reprogramming, and repair. Moreover, data suggests that the polyploidization-depolyploidization cycle (4n > 2n), which is hindered in senescent hepatic polyploidy, can be unblocked following transplantation.

5.2. High-grade polyploidy through cell fusion in aging Drosophila

Tetraploidization with age has also been observed in Drosophila neurons, particularly through endocycles. Some researchers associate neuronal polyploidy with Alzheimer’s disease

Dehn et al. observed high-grade age-induced polyploidy occurring through cell fusion and the generation of multinucleated syncytia with large nuclei in Drosophila's abdominal epithelium (69,70). This age-induced hyperpolyploidy was found to be suppressible by inhibiting cell fusion. The researchers suggest that polyploidization through cell fusion contributes to the decline in the biomechanical properties of Drosophila with age. Interestingly, the inhibition of cell fusion did not show improvement in Drosophila's lifespan. In contrast, Nandakumar et al. (71) believe that polyploidy has a protective role for neurons and glia.

5.3. Depletion of functional stem cells in aging Drosophila and polyploidization-depolyploidization cycles

The fitness of an organ relies on the maintenance of a functional stem cell pool, and a reduction in the number of functional stem cells is associated with aging. In 2017, Luchetta and Ohlstein demonstrated that the severe depletion of intestinal stem cells in Drosophila during starvation leads to polyploidization and depolyploidization cycles (72). The authors propose that the decline and loss of functional stem cells, which are hallmarks of aging, coincide with the transition from asymmetric to symmetric cell divisions. This alignment corresponds with our perspective on DSCD cells generation.

However, in cases of complete stem cell ablation in Drosophila’s ovary and testis, germline stem cells are replaced by the de-differentiation of secretory diploid cells.

6. Polyploidization in non-cancerous cell systems

While non-gametogenic (NG) germline polyploidization is rare in human tissue, it is frequently observed in cell types such as hepatocytes, cardiomyocytes, megakaryocytes, and cancer cells. Analogous to amoebae, both physiological and dysfunctional polyploidization occur in precancerous DSCDs and malignant stem cells, exhibiting varying levels of polyploidy, from low to high-level polyploidy.

In recent years, numerous efforts have been undertaken to elucidate the intricate connections among polyploidy, malignancy, and tumorigenesis (73-82). (Kat, Salm, Anats). Matsumoto (83) distinguishes between (i) the infrequent physiological polyploidization observed in healthy humans, (ii) non-physiological polyploidy evident in dysfunctional hepatocytes of aged livers, injured livers, or liver tumorigenesis (84-85), and (iii) polyploidy reduction resulting in the generation of cancer cells with small nuclei and those with large nuclei seen in tumors originating from polyploid hepatocytes (86).

6.1. Dysfunctional low-grade hepatic polyploidy (≤ 8n)

6.1.1. Binucleated tetraploids and ploidy reduction

According to Matsumoto (83) during ploidy reduction, binucleated hepatocytes typically produce four daughter nuclei in a single mitosis (87,88). This finding corresponds to the first observed phase of cystic polyploidy in amoebae, both in its functional and dysfunctional variant, when the one nucleus of the polyploidizing germline cell gives rise to four intracystc nuclei that are species-specific for amoaeba cysts.

In humans, it was postulated that ploidy reduction serves as a previously overlooked reprogramming mechanism linking normal cells to cancer development, and repeated cycles of ploidy reduction and re-polyploidization could be particularly oncogenic. Furthermore, it has been observed that ploidy reduction takes place in the early phases of tumorigenesis, and enhanced polyploid-derived cancer development (86), Researchers propose that polyploid hepatocytes readily serve as a source of tumors and suggest that ploidy reduction may occur during polyploid-derived cancer development.

The ECCB analysis, however, reveals that, carcinogenesis initiates from the oxygen-excess damaged DSCD cell phenotype, capable of indefinite proliferation through tetraploid-diploid cycling, thereby reducing polyploidy. While these cells are potential candidates, these cells are not yet deemed precancerous. The point of no return arises only when they become fusible forming MGRS syncytia. Only the MGRS polyploidy, characterized by double ploidy reduction and distinct phases such as "dysfunctional cystic polyploidy", reductive nuclear division, fusion of daughter nuclei, genome reprogramming, and hyperpolyploidy reduction, serves as an inductive factor for carcinogenesis. GPT +

6.1.2. Pathologic low- grade polyploidy in injured liver

While the physiological polyploidization of hepatocytes is primarily induced by incomplete cytokinesis, polyploidization under pathological conditions has often been associated with oxidative stress, DNA damage, G2/M arrest (89), and multiple cycles of ploidy reduction and re-polyploidization (90,91).. A similar process linking DNA damage and polyploidization has been reported by Johmura (92) and is also known from DSCDs in protists.

From the ECCB perspective, the binucleated hepatocytes observed in injured livers are considered DSCD cells with severe DNA DSB damage. They proliferate through defective symmetric cell cycling, multipolar mitosis, binucleation, amplified centrosomes, and multiple cycles of ploidy reduction and re-polyploidization, representing DSCD cell aberrations stemming from the Urgermline as responses to detrimental factors such as oxygenic stress and genotoxic factors.

In our opinion, malignization does not occur through repeated depolyploidi-zation and re-polyploidization cycles; rather, it involves hyperpolyploidization and reprogramming in hyperpolyploid giant nuclei generated with or without homotypic cell fusion. Cases of heterotypic hepatocyte cell fusion to form new hepatocytes have been also described when injured livers were regenerated with bone marrow cells (93,94).

6.1.3. Low-grade polyploidy in dysfunctional cell phenotypes; mitotic delay (prolonged mitosis), mitotic arrest and mitotic slippage

Recent investigations into the balance between cell cycle progression and cell death provided insights into the biological consequences of mitotic delay, prolonged mitosis and mitotic slippage.

As highlighted by di Rora et al. in 2019 (95), prolonged mitosis induced by factors such as DNA damage, chromosome missegregation (resulting in supernumerary chromosomes), or oncogene activation (96) can lead to mitotic slippage, wherein cells enter a new interphase without undergoing cell division. Mitotic slippage is a contributing factor to genomic instability, extensively studied in solid tumors, especially in cancer germline cells and cancer stem cells following irradiation, chemotherapy, or treatment with microtubule-affecting drugs, leading to the formation of mononucleated polyploid phenotypes (97-102).

Tetraploid cells arrested in interphase may either enter cellular senescence or undergo apoptosis (103). Apoptosis has been linked to the accumulation of DNA damage, both before and during prolonged mitosis. Notably, prolonged mitotic arrest triggers apoptosis predominantly in responsive cell lines, while cells with lower sensitivity tend to undergo mitotic slippage, entering the G1 phase as tetraploids and generating apoptotic daughter cells (104,105)

Researchers have proposed hypothetical models to elucidate prolonged mitosis and P53 activation: (i) According to the “mitotic clock“ model, cells sense the duration of mitosis and gradually accumulate P53 during mitosis, preceding mitotic slippage (106); (ii) According to the“DNA ploidy or centrosome counter checkpoint“ model, P53 activation is suggested to occur in tetraploid cells post mitotic slippage or cytokinesis inhibition (107). In turn, the degradation of cyclin B1 compromises the cell's ability to undergo apoptosis, ultimately resulting in the generation of viable polyploid cells through mitotic slippage.

6.1.4. Proliferation arrest as "terminal differentiation"?

As Matsumoto reports, polyploid cells may represent "terminally differentiated" cells that cease proliferation (108,109). An evolutionary program might ensure that differentiated polyploid cells, unlike diploid hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (110) and diploid cardiomyocytes (111,112), known for their roles in development and regeneration, undergo cell cycle arrest. This assumption coupled with the observation that polyploidization of non-transformed cells in vitro often leads to cell cycle arrest (113), has historically contributed to the formulation of the "tetraploidy checkpoint" hypothesis (114).

6.1.5. Delayd polyploidy initiation after hepatectomy and liver regeneration

Studies have demonstrated that after a partial hepatectomy of approximately 70%, and dynamic liver regeneration in mice, nearly all hepatocytes, including polyploid cells, re-enter the cell cycle and undergo DNA synthesis in S-phase. About half of these hepatocytes do not enter the M phase, resulting in polyploidization and hepatocyte hypertrophy. In contrast, others complete mitosis and proliferate (115).

Research indicates that polyploid hepatocytes proliferate following extensive surgical resection of the liver, albeit with a relatively delayed initiation compared to diploid hepatocytes (115). Recent findings show that even octoploid hepatocytes continue to proliferate continuously during various types of chronic liver injury (88). Notably, proliferating polyploid hepatocytes sometimes give rise to daughter cells, indicating ploidy reduction during regeneration driven by polyploid cells in chronically injured livers.

6.2. Dysfunctional middle-grade hepatic polyploidy (≤ 64n)

6.2.1. Polyploid cardiomyocytes – a dysfunctional pathogenic cell phenotype

While the majority of adult ventricular cardiomyocytes in mammals typically display polyploidy, Jiang et al. (2019) uncovered that the polyploid cardiomyocyte is not the normal physiological phenotype but rather an indication of a pathological condition (116). Shifting oxygen levels from the standard germline and stem cell normoxia (5.7-6.0% O2 content) to hyperoxia, with more as 6.0%O2 content, triggers mitotic slippage in anaphase and polyploidization. This transformation alters normal diploid cardiomyocytes into tetraploids or octoploids with multiple diploid or multiple tetraploid (or higher) nuclei (117).

Cardiomyocytes that exit the cell cycle in anaphase are those that have experienced severe DNA double-strand break (DNADSB) damage and insufficient ECT2 levels, which normally contribute to DNA repair. ECT2 serves as a crucial regulator in cytokinesis; it is phosphorylated during G2/M phase and then dephosphorylated before cytokinesis. Even when not phosphorylated, ECT2 remains biologically active. Depletion of ECT2 efficiently induces multinucleate cells (118). According to Cao et al. (119), “ECT2 deficiency impairs the repair of DNA double-strand breaks and leads to an accumulation of damaged DNA, rendering cells hypersensitive to genotoxic factors such as excess oxygen.

6.2.2. The enigmatic endopolyploidy of up to 64n observed in cardiac injury and cardiac hypertrophy does not contribute to cardiac regeneration

As highlighted by Karbassi et al. in their 2020 study, the observed quiescence or cell cycle arrest in post-natal cardiomyocytes aligns with the transition from a hypoxic to an oxygen-rich environment after birth (120). Polyploidization can occur through DNA synthesis and nuclear division, leading to binucleated cells (as seen in rodents), or through DNA synthesis without subsequent nuclear division, resulting in the formation of polyploid nuclei, a phenomenon predominantly observed in human cardiomyocytes (121,122). Consequently, the degree of polyploidy in human cardiomyocytes tends to increase with age, ranging from 4n to 64n. Additionally, the incidence of polyploid cells rises following injuries and myocardial infarction (123-125).

Despite current limitations in understanding the regulatory mechanisms of polyploidization, evolutionary indicators suggest a connection to DNA error repair. The functional role of polyploidization and its impact on cell physiology present promising avenues for exploration. Derks and Bergmann noted in 2020 –(126) that the benefits and physiological role of polyploidy in cardiomyocytes remain enigmatic. Increased cardiomyocyte ploidy is associated not only with growth and development but also with diseases (122, 127-129). Importantly, the mechanisms underlying polyploidization after cardiac injury and hypertrophy are not identical to postnatal polyploidy.

As Puente et al. stated in 2014 (130) cardiomyocyte binucleation results from oxidative stress during the perinatal period, exposing cardiomyocytes to increasing levels of oxidative stress, causing severe DNA damage and defective cell cycles. This leads to acytokinetic mitosis (cytokinesis failure), multinucleation, or nuclear polyploidy. The physiological significance of such polyploid phenotypes remains elusive. Increased cardiomyocyte ploidy is also associated with pathological heart conditions; however, it is unclear if polyploidization following cardiac injury, myocardial infarction, and cardiac hypertrophy is the same as developmental polyploidization (122).

In our evolutionary perspective, diploid cardiomyocytes, when exposed to oxidative damage or genotoxic stressors, lose functionality but can proliferate through tetraploid cell cycles facilitated by the tetraploid DSCD phenotype. This allows them to evade senescence and programmed cell death. Binucleated cardiomyocytes, in particular, retain the ability to proliferate, and most dividing binucleated cardiomyocytes generate daughter cells containing 2 centrioles, enabling ploidy reduction through the formation of a regular bipolar spindle in the subsequent cell division (131).

In summary, cardiomyocyte polyploidy represents a barrier to the regeneration of the normal cardiomyocyte phenotype. Highly polyploidized cardiomyocytes with up to 64n, which occur after induced cardiac injury (132), have lost the capacity for cardiac regeneration and proliferation. Cardiac regeneration rather depends on the fraction of mononuclear diploid cardiomyocytes. GPT +

6.2.3. Metabolic reprogramming to glycolisis coincides in cardiocytes with cell cycle arrest and binucleation.

In a recent study on the metabolic reprogramming of cardiomyocytes, Elia et al. (133) demonstrated that during the transition from fetal to postnatal cardiomyocytes, the progressive increase in oxygen production induces a shift from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation. This metabolic shift coincides with cardiomyocyte cell cycling arrest and binucleation (134). The researchers propose that the rising reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, particularly after birth, activates mitogen-activated protein kinases, promoting cell cycle arrest and the formation of binucleated cardiomyocytes (135).

Conversely, glycolytic activity increases in postischemic cardiac tissue and gradually declines in heart failure, accompanied by a significant enhancement in polyploidization levels and cell cycle arrest. The researchers consider the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases as a master regulator of heart proliferation and polyploidization, leading to a progressive impairment in cardiac regeneration ability.

Several years earlier, Cui et al. identified a small proliferative diploid cardiomyocyte population in the mouse heart exhibiting increased glycolytic properties but disappearing as the heart matures (136,137).The molecular and metabolic developmental signature is lost with cardiac tissue maturation. Reactivation of developmental signaling factors in the heart leads to metabolic reprogramming favoring increased cell cycle activity and the persistence of mononuclear diploid cardiomyocytes, augmenting myocardial repair after injury (138).

Anaerobic glycolysis is a hallmark of non-gametogenic germlines and stem cell lineages, homologous both with the ancestral hypoxic Urgermline. NG germlines and stem cells heavily depend on anaerobic glycolysis.

6.3. Irreversible DNA damage as the point of no return; checkpoints and malignization barriers

When exposed to oxygenic stress and hyperoxia exceeding 6.0% O2 content, non-gametogenic NG germlines, and stem cell lineages of humans, metazoans, and protists experience DNA DSB damage. This damage results from a decline in HR gene activity, leading to the loss of stemness, differentiation, and asymmetric cell division (ACD) potential. It marks the point of no return from the functional ACD phenotype into (i) a proliferating DSCD phenotype capable of defective symmetric cell cycling (DSCD) and dysfunctional low-grade polyploidy (≤ 8n) or (ii) arrest in a non-proliferative state, continuing endopolyploidization to middle-grade polyploidy (≤ 64n). The transition to proliferative DSCD phenotypes, marked by endomitosis, binucleation, mature and immature nuclei, and low-grade polyploidy, signifies the point of no return to normality, applicable to both damaged cells and theirs progeny.

Although proliferating tetraploid DSCD cells are capable of ploidy reduction and transiently reverting to an apparently nominal diploid cell cycle, they ultimately revert to tetraploid-diploid cell cycles (4n > 2n > 4n) under hyperoxic conditions (>6.0% O2 content). In cases where DSCD cell division is definitively halted by a cytokinetic checkpoint, non-proliferating tetraploids increase their ploidy level to octoploidy, as observed in hepatocytes, or, to a middle-range polyploidy of up to 64n, as observed in cardiomyocytes, resulting from endocycles or homotypic cell fusion (139,140).

Low-grade polyploids (e.g.hepatocytes) can activate the MGRS machinery, leading to malignant transformation and liver cancer, whereas higher-grade polyploids (cardiomyocytes) cannot. It is possible that middle-range polyploidy and the resulting quiescence serves as a barrier in the MGRS activation and malignization of cardiomyocytes.

Low-grade and middle-grade polyploidization are forms of evolutionary polyploidy accompanying the switch into the defective DSCD state, arising as a consequence of HR gene functional decline and irreparable DNA DSB defects. The dysfunctional variants of lower and middle polyploidy are not a cause but a consequence of HR dysfunctionality. We express reservations about the use of the term "terminal differentiation" (139) in the context of lower and middle polyploidy. Still, we agree that the transformation of the ACD phenotype into a proliferating DSCD or a homologous non-proliferating phenotype is an evolutionarily "regulated process."

On the other hand, our findings disagree with the attempt to separate the mechanisms of non-cancerous polyploidy from cancer polyploidy by "distinguishing features between karyokinesis and cytokinesis failure in cardiomyocytes vis-à-vis abnormal mitoses in cancer: the programmed nature, as opposed to dysregulated cancer cell mitosis and the resulting reduction in the proliferative proliferative potential of the polyploid daughter cardiomyocytes, as opposed to the increased the increased malignant potential of aneuploid cancer cells" (139). From our evolutionary point of view, both cases involve a uniform evolutionary mechanism (HR gene defects) that causes dysfunctional low- and intermediate-grade polyploidy. This includes cases of mitotic aneuploidy, which also occur in NG germ lines and stem cell lines as a result of declined HR repair activity, DNA DSB defects, and errors in chromosome partitioning.

7. Functional and dysfunctional cancer polyploidy

Following the overview of functional and dysfunctional polyploidy, spanning from parasitic protists to hepatocytes and cardiomyocytes, we now examine evolutionary polyploidy in cancer.

7.1. Dysfunctional cancer polyploidy (tetraploidy, aneuploidy)

Polyploidy variants described in cancer are often identical to those observed in cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, Drosophila, and parasitic amoebae. However, their interpretation in an evolutionary context remains challenging.

In the realm of cancer, significant efforts have been invested to enhance our understanding of cancer polyploidy. Extensive anatomo-pathological studies, coupled with molecular biological analyses, have been conducted. Numerous experimental studies involving genotoxic agents, irradiation, and chemotherapeutic agents have explored the role of polyploidization in treated cancer germ cells and cancer stem cells (CSCs), as well as the subsequent restoration ability, cell fate, and phenotypes.

Even in the absence of genotoxic treatments, cancer NG germlines and CSCs sustain continuous damage through hyperoxic stress (>6.0% O2 content) from the tissue and bloodstream as well as metabolic and immunological attacks. Consequently, differences in behavior between cancer cell polyploidy and non-cancerous polyploidy, such as in cases of mitotic aneuploidy, emerge. Nevertheless, the observed similarities in polyploidy between cancer and pathogenic protists are particularly noteworthy.

The most intricate review articles of the last 20 years on cancer polyploidy originate from renowned research groups such as Anatskaya and Vinogradow, Erenpreisa and colleagues, as well as Was and coauthors (67-77, 141-144). In many cases, it remains unclear whether low-, medium-, or high-grade ploidy occur and which variants are proliferative or non-proliferative.

In this context, one of the authors of the present paper pointed out in 2020 the deep homology between ancestral polyploid protist cysts and polyploid giant cancer cell structures (PGCCs) (23). The ancestral origin of PGCCs and the equation MGRS: PGCCs were postulated, along with the presence of ancestral cyst-like structures (aCLS’) in cancer. Terms such as "aCLS cancers" and "PGCC cancers," as well as pretumorigenic cyst-like structures (pCLS) and genotoxic-induced cyst-like structures (giCLS), were introduced. It was suggested that there is an intimate relationship between MGRSs and PGCCs, allowing for the common term MGRS/PGCC structures (9-11,13,23]. Despite being long ignored, the role of polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs) has recently been recognized as a key driver mechanism for cancer initiation and metastasis (10, 145-152).

7.2. DOX induced PGCCs and functional cancer polyploidy

One of the most notable works, providing compelling results for the validation of MGRS:PGCC equation is the 2019 paper by Salmina et al. (78). As reported, the induction of polyploidization and PGCC formation in the MDA-MB-231 cell line treated with doxorubicin (DOX) recapitulates an "amoeba-like agamic life-cycle." This article recognizes the presence of reproductive cyst-like structures in cancer, along with phases of cyst polyploidization and hyperpolyploidization in giant PGCC nuclei. These phases closely resemble the phases of polyploidization-depolyploidization and hyperpolidization observed in the MGRS of amoebae (phase I and II).

The findings from DNA cytometry are remarkable. The low-grade polyploidization/depolyploidization cycles (phase I) persist for approximately 16 days, which is notably longer than observed in protists. According to the researchers, there was initially a "progressive increase of ~4C, ~8C, and ~16C peaks of underreplicated DNA due to metaphase arrest and mitotic slippage, along with partial euploid 8C and 16C peaks. Cytokinetic cell division had not yet resumed. All cells that underwent mitotic slippage continued to accumulate increasing amounts of damaged DNA in the cytoplasm."

On day 16, phase I concludes without cytokinetic mitoses. However, a dual development is observed: one involving a depolyploidization trend and another exhibiting a repolyploidization trend (>32C); Two distinct giant cell sublines emerge, with one undergoing depolyploidization and the other persisting in re-replication cycles and mitotic slippage. In our interpretation, a high-grade polyploidization (phase II) follows the low-grade polyploidization (phase I), also referred to as cystic -polyploidy.

The researchers stated, "The proportion of hyperpolyploid cells and mitotic slippage continued to increase. Some cells reached 128 C-ploidy, indicating that giant and supergiant cells dominated, filling up the cell population by their mass. In other experiments with slightly slower recovery, the maximum encountered DNA amount in the (endo)metaphase was 52C, and the largest interphase cell reached 396 C DNA content.".

By the end of the second week, most cells attained a diameter of 50–300 µm, occasionally generating cysts. The budded PGCC progeny promptly engaged in normal bipolar cell division. At this early recovery stage, newly born small amoeboid cells and giant cells appeared to cooperate as a system.

These findings unequivocally demonstrate that MGRS and PGCCs are evolutionary sisters in the recovery, repair, and reprogramming of defective germlines and stem cells. The formation of cysts from PGCCs signifies progress into reproductive-endopolyploid cycles, akin to reproductive-polyploid cyst cycles in amoebae (Figure 2), and the restoration of genomic integrity in damaged dysfunctional cancer germlines and cancer stem cells.

8. Conclusions

8.1. In this study, we successfully deciphered the puzzle of cancer polyploidy by demonstrating, that all NG germlines and stem cell lineages in humans, metazoans, and cancers can be traced back to the oxygen-sensitive Urgermline of the AMF ancestor. Exposure to hyperoxic conditions with an O2 content exceeding 6.0%, beyond the normoxic-physiological range of the Urgermline (AMF hyperoxia) , inevitably leads to irreversible DNA double-strand break (DSB) damage by deactivating homologous recombination (HR) repair genes. As a consequence, there is a loss of stemness, asymmetric cell division (ACD), differentiation capacity, and the ability to generate stem cells.

8.2. This evolutionary polyploidy, with all its variants, originated in the period between 2350-1750 million years ago (Mya) from the AMF ancestor and is a characteristic feature of Urgermline and NG germlines. In the context of AMF hyperoxia (as occurring in tissue and bloodstream), HR repair function is compromised and decline. Consequently, oxygen stress leads to the loss of stemness, differentiation, and ACD potential. It is the transition from a functional ACD phenotype to a dysfunctional DSCD phenotype, capable of proliferating solely through aberrant symmetric cell cycling SCD.

8.3 The evolutionary "healthy" ACD germline phenotype possesses the capacity to undergo functional reproductive-polyploid cycles (8n, 16n cycles). This process leads to the generation of haploid stem cell precursors, which subsequently mature into diploid germline stem cells (GSCs). It is noteworthy that the functional polyploidization-depolyploidization cycle, observed in cancer cysts, has its origins in the cystic AMF polyploidy.

8.4 The DSCD phenotype is a endomitotic phenotype that induces dysfunctional polyploidy in both cancerous and non-cancerous cells, as well as in protists. This encompasses low-grade polyploidy variants (such as tetraploidy and ist aneuploide effects) and the dysfunctional middle-grade forms observed particularly in hepatocytes and cardiomyocytes. Dysfunctional polyploids lack the capability to regenerate "healthy" diploid cells Even if tetraploid cells temporarily revert to diploid cycles, the executing cells retain DNADSB defects and remain non-functional. This assertion is applicable to all low- and middle grade polyploids of cancer.

8.5 Evolutionary MGRS/PGCCs are giant polyploid structures present in carcinogenesis, tumorigenesis and protists. They have repair and reprogramming function, reconstructing genome integrity. MGRS/PGCC can arise through homotypic cell-and-nuclear fusion or through single-celled endomitotic polyploidization. The MGRS/PGCC unfolds in two phases. In phase I, a process of deregulated cystic polyploidy occurs, resembling the healthy cystic polyploidy of protists, with the difference that both mother nucleus and nuclear progeny are defective and can not cellularize to stem cell precursors. In phase II, the defective nuclear progeny fuses, giving rise to hyperpolyploid or superhyperpolyploid giant nuclei that possess the capability to excise and remove damaged DNA fragments.

8.6 Cancer has acquired not only the presence of MGRS’/PGCCs with deregulated cystic polyploidy but also the ability to form complete reproductive cysts, as detailed by Salmina et al. (78). The progeny of MGRS’/PGCCs, appearing as spores and buds, possess the capability to directly establish new NG germ lines or to enhance stem cell production through additional reproductive cysts. This process generates an increased mass of stem cells, facilitating the initiation of new NG germlines and sustaining the dual germline and soma life cycle of cancer.

8.7 This study clarifies the evolutionary nature of cancer polyploidy. The functional NG germline in cancer embraces mechanisms such as ACD proliferation, reproductive cyst formation, and functional cyclic polyploidization, as demonstrated by Salmina et al. On the other hand, cancer employs MGRS/PGCC structures to reprogram dysfunctional DSCD phenotypes. Notably, dysfunctional low- and middle-grade polyploidy events such as tetraploidy, octoploidy, and multinucleation lack repair and reprogramming functions.

Abbreviations

ACD: asymmetric cell division; AMF, amoebozoa, metazoa and cancer; CLS, cyst-like structure ; DSB, double-strand breaks; DSCD; defective symmetric cell division; ECCB, evolutionary cancer cell biology; HR, homologous recombination; MGRS, multinucleated genome repair syncytia; NG, non-gametogenic; PGCC, polyploid giant cancer cell; SCD, symmetric cell division

References

- Shapiro, J.A. What can evolutionary biology learn from cancer biology? Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 2021, 165, 19e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boveri, T. Concerning the origin of malignant tumours by Theodor Boveri. Translated and annotated by Henry Harris. J. Cell Sci. 1914; 121, (Suppl. 1), 1e84. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18089652/. [CrossRef]

- Erenpreisa, J.; Cragg, M.S. Three steps to the immortality of cancer cells: senescence, polyploidy and self-renewal. Canc. Cell Int. 2013, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravegnini, G.; et al. Key genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in chemical carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 148, 2e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; et al. Polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs): the evil roots of cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2019, 19, 360e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.L.; de Lucas, B.; Galvez, B.G. “Unhealthy“ Stem Cells: When Health Conditions Upset Stem Cell Properties. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 46, 1999–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, M.S.; Ward, C.M.; Davies, C.C. DNA Repair and Therapeutic Strategies in Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers. 2023, 15, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokzijl, F.; de Ligt, J.; Jager, M.; Sasselli, V.; Roerink, S.; et al. Tissue-Specific Mutation Accumulation in Human Adult Stem Cells during Life. Nature. 2016, 538, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. The evolutionary cancer genome theory and its reasoning. Genetics in Medicine Open. 2023, 1, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. Understanding cancer from an evolutionary perspective: high-risk reprogramming of genome-damaged stem cells. Academia Medicine 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. Cancer genes and cancer stem cells in tumorigenesis: Evolutionary deep homology and controversies. [CrossRef]

- White-Gilbertson, S.; Voelkel-Johnson, C. Giants and monsters: Unexpected characters in the story of cancer recurrence. Adv Cancer Res. 2020, 148, 201–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niculescu, V.F. Niculescu, V.F. Introduction to Evolutionary Cancer Cell Biology (ECCB) and Ancestral Cancer Genomics. Qeios 2023, ID: 61VCRV. [CrossRef]

- Burki, F.; Roger, A.J.; Brown, M.W.; Simpson, A.G.B. The new tree of eukaryotes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2020, 35, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Trigos, A.S.; Pearson, R.B.; Papenfuss, A.T.; Goode, D.L. Altered interactions between unicellular and multicellular genes drive hallmarks of transformation in a diverse range of solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017, 114, 6406–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigos, A.; Pearson, R.; Papenfuss, A.; Goode, D.L. How the evolution of multicellularity set the stage for cancer. Br J Cancer 2018, 118, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigos, A.; Pearson, R.; Papenfuss, A.; Goode, D.L. Somatic mutations in early metazoan genes disrupt regulatory links between unicellular and multicellular genes in cancer. eLife 2019, 8, e40947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. The stem cell biology of the protist pathogen Entamoeba invadens in the context of eukaryotic stem cell evolution. Stem Cell Biol Res. 2015, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. The cell system of Giardia lamblia in the light of the protist stem cell biology. Stem Cell Biol Res. 2014, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, J. What Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia tell us about the evolution of eukaryotic diversity. J. Biosci. 2002, 27, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. Attempts to restore loss of function in damaged ACD cells open the way to non-mutational oncogenesis. Genes & Diseases 2024, 11, 101109. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, D.; Ghosh, S.K. Cellular Events of Multinucleated Giant Cells Formation During the Encystation of Entamoeba invadens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niculescu, V.F. aCLS cancers: Genomic and epigenetic changes transform the cell of origin of cancer into a tumorigenic pathogen of unicellular organization and lifestyle. Gene. 2020, 726, 144174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.C.W. ; Lineweaver CH (2011). Cancer tumors as Metazoa 1.0: Tapping genes of ancient ancestors. Physical Biology. 2011, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lineweaver, C.H.; Davies, P.C.W.; Vincent, M.D. Targeting cancer’s weaknesses (not its strengths): Therapeutic strategies suggested by the atavistic model. Bioessays. 2014, 36, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktipis, C.A.; Boddy, A.M.; Jansen, G.; Hibner, U.; Hochberg , M.E.; et al. Cancer across the tree of life: cooperation and cheating in multicellularity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2015, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, L.; Bussey, K.J.; Orr, A.J.; Miočević, M.; Lineweaver, C.H.; Davies, P. Ancient genes establish stress-induced mutation as a hallmark of cancer. PloS One. 2017, 12, e0176258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lineweaver, C.H. Lineweaver, C.H.; Davies PCW (2021). Comparison of the atavistic model of cancer to somatic mutation theory: Phylostratigraphic analyses support the atavistic model. Chapter 12 T. In: Gerstman BS (Ed.), The Physics of Cancer: Research Advances, pp. 243–261. World Scientific.

- Li, X.; Zhong, Y.P.; Zhang, X.D.; Sood, A.K.; Liu, J. Spatiotemporal view of malignant histogenesis and macroevolution via formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene. 2023, 42, 665–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J. The, “life code”: a theory that unifies the human life cycle and the origin of human tumors. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020, 60, 380–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantzeskakis, L.; Kusch, S.; Panstruga, R. The need for speed: compartmentalized genome evolution in filamentous phytopathogens. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2019, 20, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetanam K., Jr.; Lacina, L.; Szabo, P.; Dvorankova, B.; Broz, P.; Sedo, A. Ageing as an Important Risk Factor for Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 5009–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feltes, B.C.; de Faria Poloni, J.; Bonatto, D. The developmental aging and origins of health and disease hypotheses explained by different protein networks. Biogerontol. 2011, 12, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.N.; Kaeberlein, M. Why is aging conserved and what can we do about it? PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L. ; Serrano M and Kroemer G: The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhalter, M.D.; Rudolph, K.L.; Sperka, T. Genome instability of ageing stem cells – Induction and defence mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev 2015, 23, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, A.; van Deursen, J.M.; Rudolph, K.L.; Schumacher, B. Impact of genomic damage and on stem cell function. Nat Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsdottir, S.; Hampel, H.; Tomsic, J.; Frankel, W.L.; Pearlman, R.; et al. Colon and endometrial cancers with mismatch repair deficiency can arise from somatic, rather than germline, mutations. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, L.B.; Nik-Zainal, S.; Wedge, D.C.; et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013, 500, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, I.R.; Takahashi, K. ; Futreal PA and Chin L: Emerging patterns of somatic mutations in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berben, L.; Floris, G.; Wildiers, H.; Hatse, S. Cancer and Aging: Two Tightly Interconnected Biological Processes. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, N.A.; Savvides, P.; Koroukian, S.M.; Kahana, E.F.; Deimling, G.T.; et al. Cancer in the Elderly. Trans. Am. Clin. Clim. Assoc. 2006, 117, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Yancik, R. Cancer burden in the aged: An epidemiologic and demographic overview. Cancer. 1997, 80, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccormick, R.E. Possible acceleration of aging by adjuvant chemotherapy: A cause of early onset frailty? Med Hypotheses. 2006, 67, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell. 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunan, J.R.; Cho, W.C.; Søreide, K. The Biology of Aging and Cancer: A Brief Overview of Shared and Divergent Molecular Hallmarks. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løhr, M.; Jensen, A.; Eriksen, L.; Grønbæk, M.; Loft, S.; Møller, P. Association between age and repair of oxidatively damaged DNA in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mutagenesis. 2015, 30, 695–700, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, S.L.; Croken, M.M.; Calder, R.B.; Aliper, A.; Milholland, B.; et al. DNA repair in species with extreme lifespan differences. Aging. 2015, 7, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brun, C.; Jean-Louis, F.; Oddos, T.; Bagot, M.; Bensussan, A.; Michel, L. Phenotypic and functional changes in dermal primary fibroblasts isolated from intrinsically aged human skin. Exp Dermatol. 2016, 25, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfalah, F.; Seggewiß, S.; Walter, R.; Tigges, J.; Moreno-Villanueva, M.; et al. Structural chromosome abnormalities, increased DNA strand breaks and DNA strand break repair deficiency in dermal fibroblasts from old female human donors. Aging. 2015, 7, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavarva, J.H.; Tae, H.; McIver, L.; Karunasena, E. ; Garner HR: The dynamic exome: acquired variants as individuals age. Aging. 2014, 6, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, C. ; Bernstein H: Epigenetic reduction of DNA repair in progression to gastrointestinal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015, 7, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, N.; Tokunaga, E.; Kitao, H.; Hitchins, M.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Epigenetic inactivation of BRCA1 through promoter hypermethylation and its clinical importance in triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015, 15, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.; Ribeiro, M.L. Epigenetic regulation of DNA repair machinery in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 9021–9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. aCLS cancers: Genomic and epigenetic changes transform the cell of origin of cancer into a tumorigenic pathogen of unicellular organization and lifestyle. Gene. 2020, 726, 144174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, M.; Guernsey, D.L.; Rajaraman, M.M.; Rajaraman, R. Neosis: A novel type of cell division in cancer. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2004, 3, 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman, R.; Rajaraman, M.M.; Rajaraman, S.R.; Guernsey, D.L. Neosis – A paradigm for self-renewal in cancer. Cell Biol International. 2005, 29, 1084–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, R.; Guernsey, D.L.; Rajaraman, M.M.; Rajaraman, S.R. Stem cells, senescence, neosis and self-renewal in cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2006, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. Developmental and Non Developmental Polyploidy in Xenic and Axenic Cultured Stem Cell Lines of Entamoeba invadens and, E. histolytica. Insights Stem Cells. 2016, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu, V.F. Growth of Entamoeba invadens in sediments with metabolically repressed bacteria leads to multicellularity and redefinition of the amoebic cell system. Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol. 2013, 72, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu, V.F. Development, cell line differentiation and virulence in the primitive stem-/progenitor cell lineage of Entamoeba. J Stem Cell Res Med 2017, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said-Fernández, S.; Mata-Cárdenas, B.D.; González-Garza, M.T.; Navarro-Marmolejo, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, E. Entamoeba histolytica cysts with a defective wall formed under axenic conditions. Parasitol Res. 1993, 79, 200–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Díaz, H.; Díaz-Gallardo, M.; Laclette, J.P.; Carrero, J.C. In vitro induction of Entamoeba histolytica cyst-like structures from trophozoites. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010, 4, e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.F. Studies upon the amebae in the intestine of man. J Infect Dis. 1908, 5, 324–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, C.; Clark, C.G.; Lohia, A. Entamoeba Shows Reversible Variation in Ploidy under Different Growth Conditions and between Life Cycle Phases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008, 2, e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, C.; Majumder, S.; Lohia, A. Inter-cellular variation in DNA content of Entamoeba histolytica originates from temporal and spatial uncoupling of cytokinesis from the nuclear cycle. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009, 3, e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.S. Axenic cultivation of Entamoeba hitolytica. Science. 1961, 134, 336–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]