Submitted:

28 February 2024

Posted:

28 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Develop a glycerin purification process simulation model to determine optimal operating conditions and generate data for the support set.

- Formulate a robust predictive model based on deep learning constructed using LSTM structure fine-tuning based on few-shot learning techniques for tracking the refined glycerin production capacity and water content of refined glycerin under multiple operating conditions.

- Reveal the relationship between the input variables and the target variables of the prediction model to enhance the production capacity and water content using the proposed model.

2. Materials and Methods

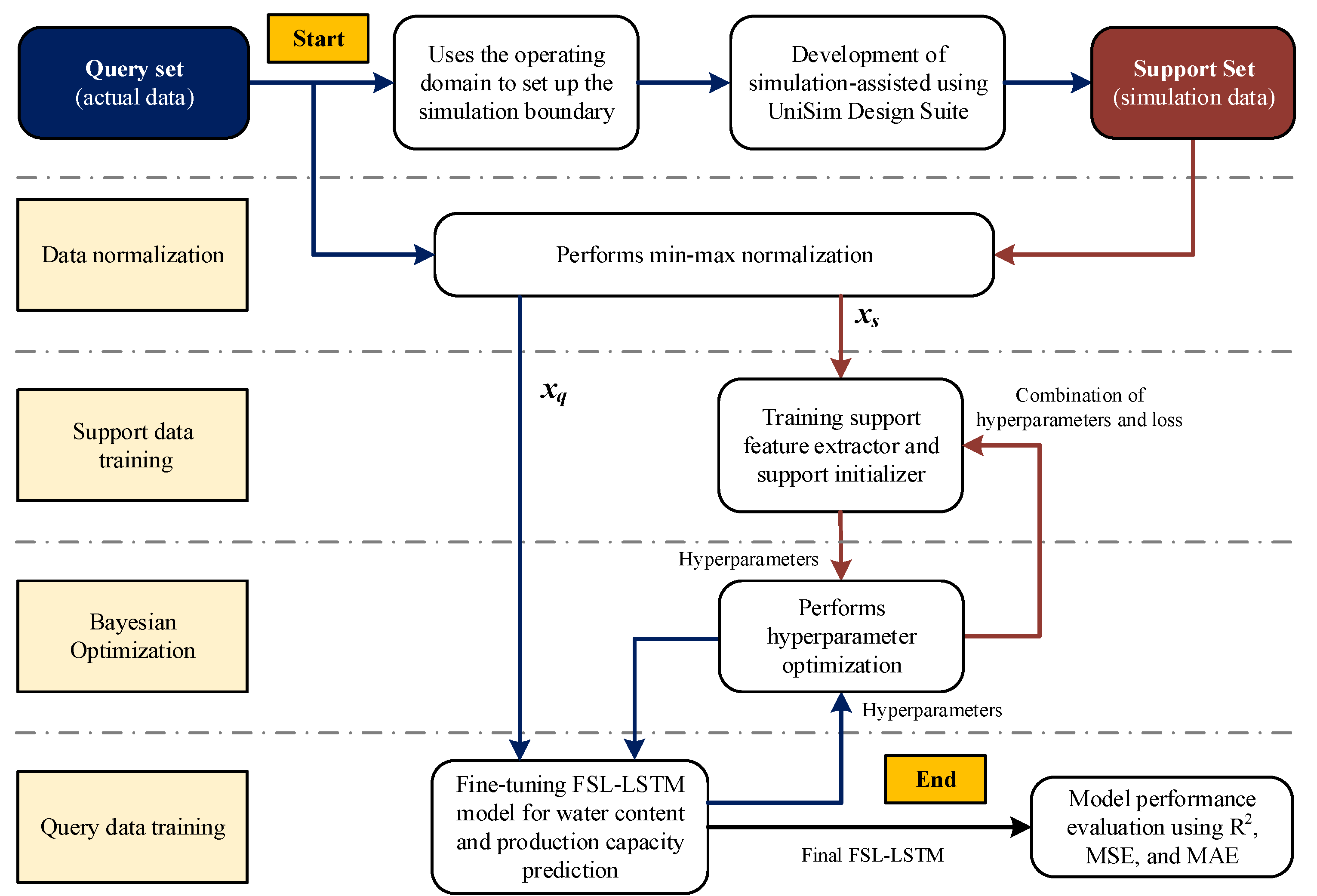

2.1. Simulation-assisted few-shot learning

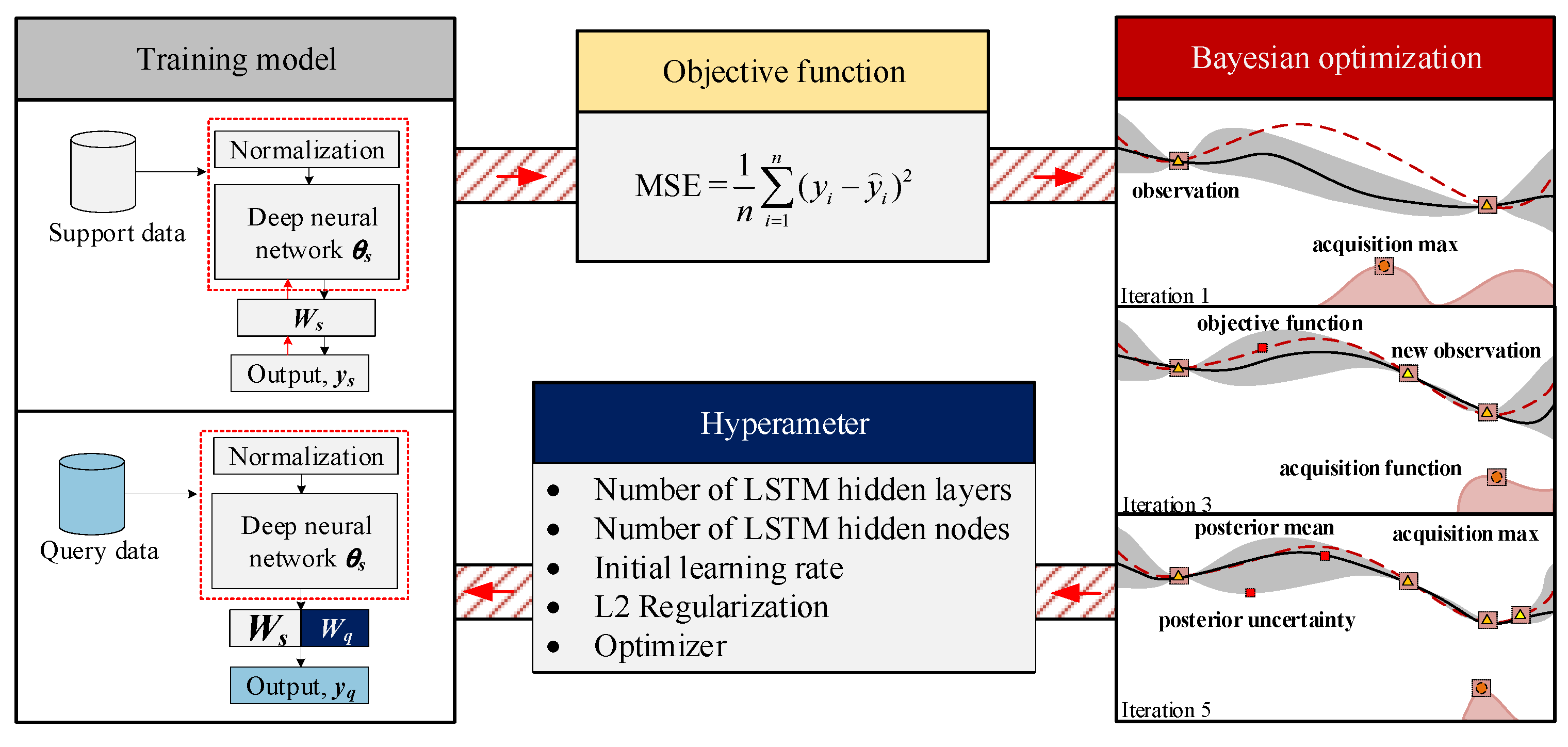

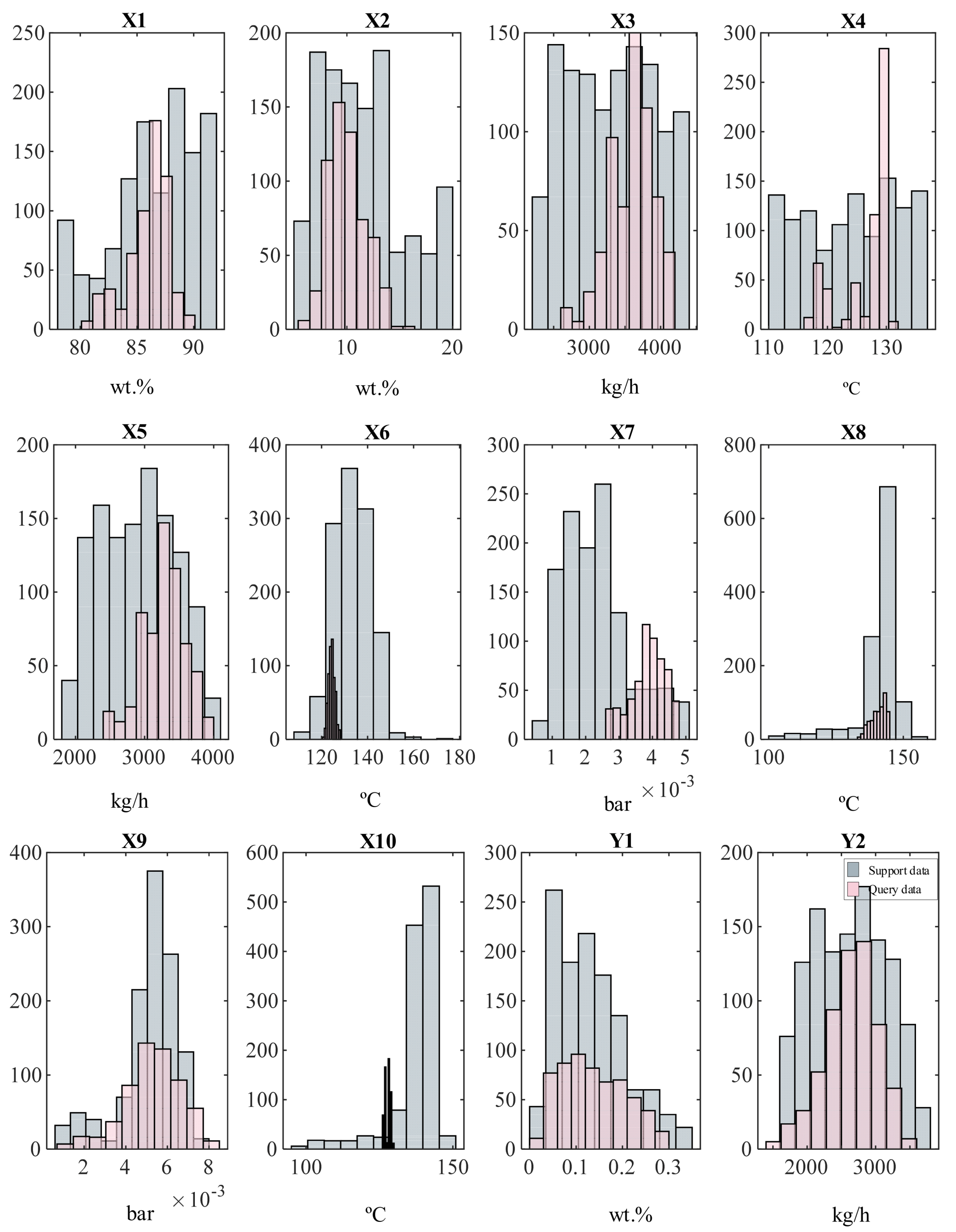

- Support and query data: The model operates on two datasets, including the support data (xs), which is excess data used to pre-train the model obtained by simulation, and the query data (xq), which refers to the limited data utilized to fine-tune and evaluate the ability of the model to generalize obtained by actual data from the large-scale glycerin purification process.

- Deep neural network: A deep neural network, in this case, LSTM (discussed in Section 2.2), functions as a feature extractor. It is optimized using the support data to derive representations that can be adapted to unseen query data or shared between domains.

- Normalization block: Within the neural network, a normalization procedure is applied to regulate the feature scaling. This can significantly help the model maintain and stabilize the training dynamics. Both input and output variables are rescaled into zero to one [0,1] using Equation (1).

- (1)

- Support initializer and extender predictor: The initializer is used to create the predictor initial weights (Ws) based on the support data, embedding the gained knowledge into the model. Subsequently, the extended predictor undergoes a few-shot learning phase using the limited query data to predict the final output (yq). In this step, partial layer freezing is applied to the initial weights to prevent overfitting and preserve previous knowledge gained from the support data while adapting to the specific query data. Only the modifying weights (Wq) are adjusted during fine-tuning using the loss gradient from query data, where the loss is a half-mean-squared error (HMSE) calculated by Equation (2). The local learning rate of initial weight is set to zero during the fine-tuning step.

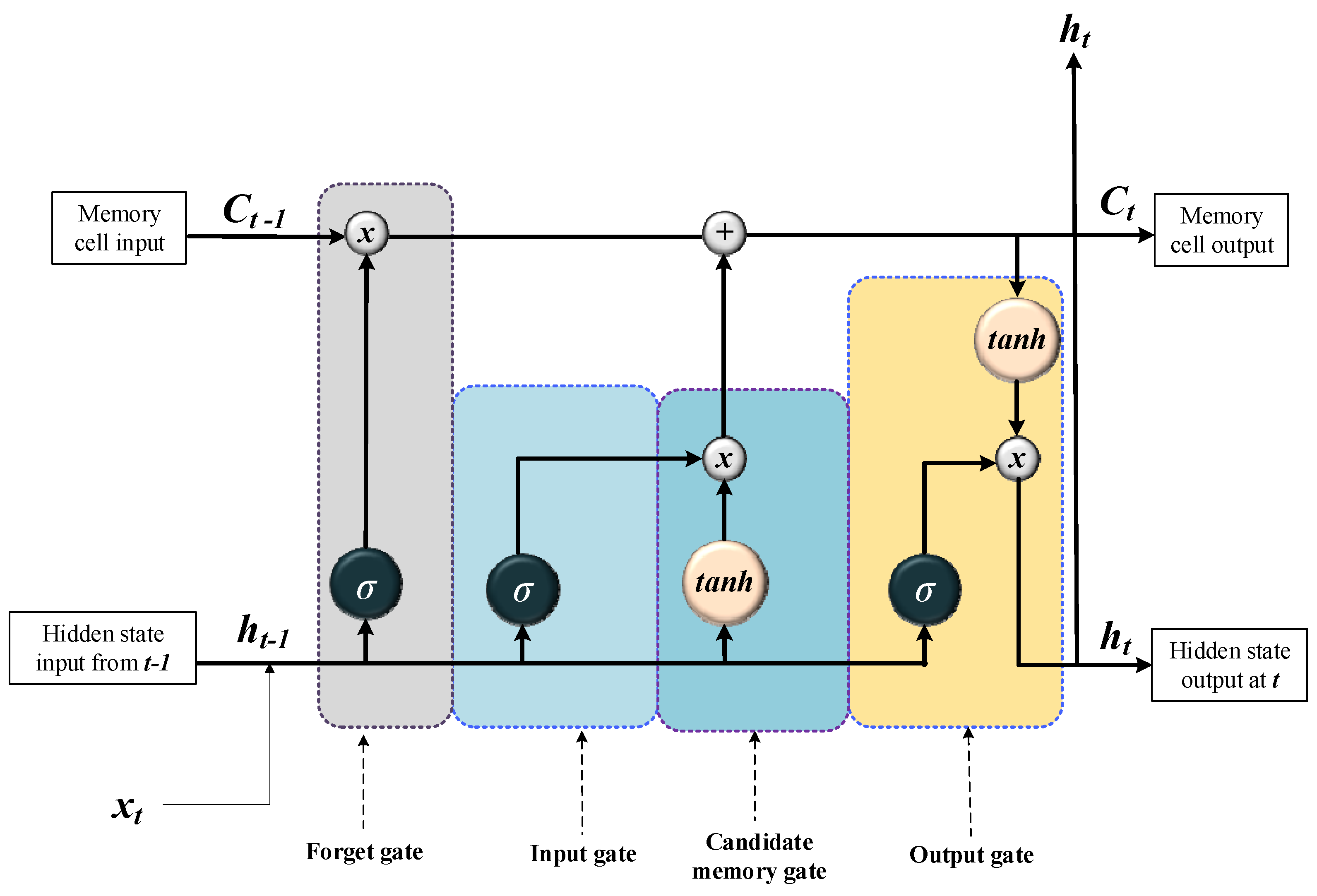

2.2. LSTM network architecture

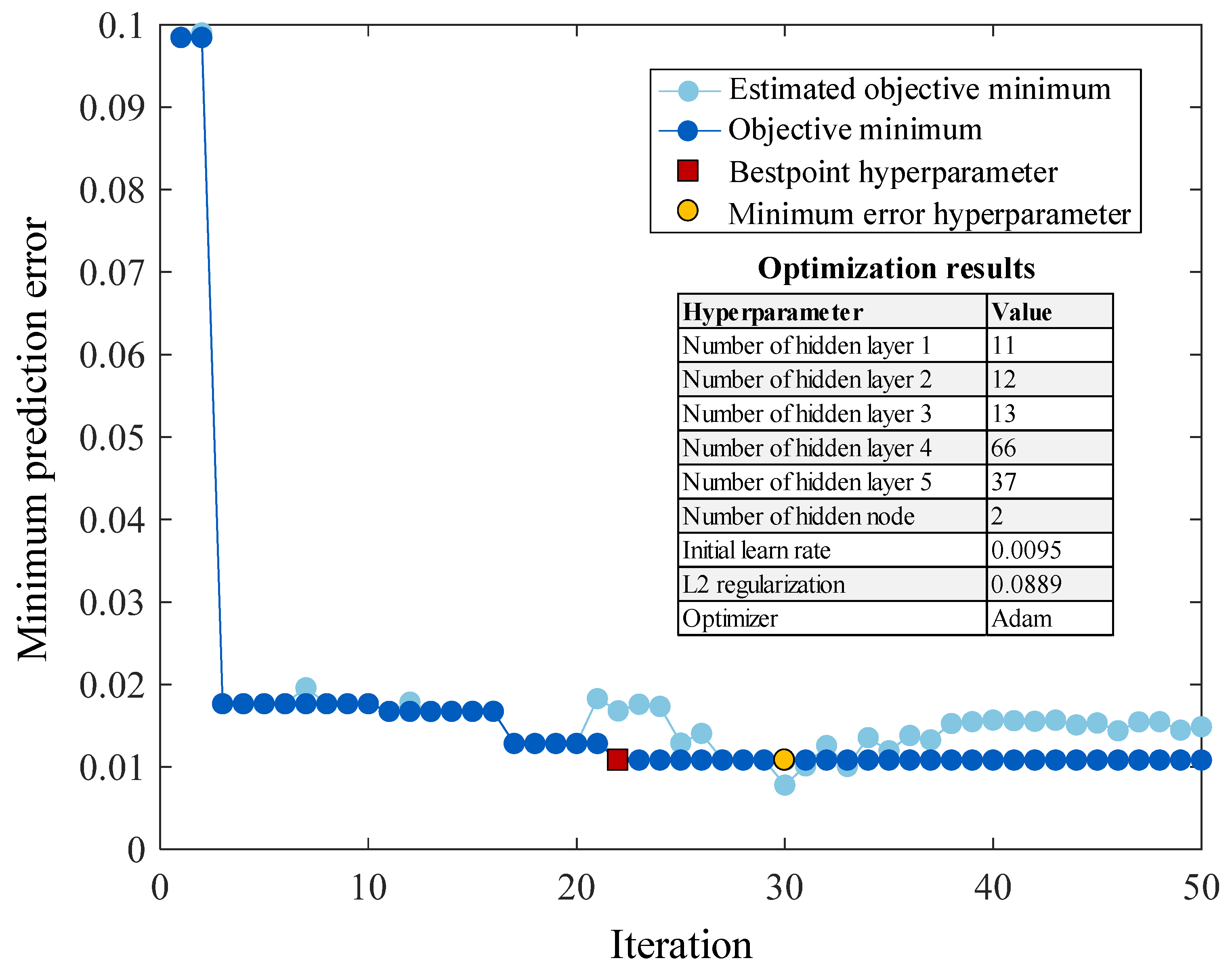

2.3. Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning

3. Glycerin purification case study

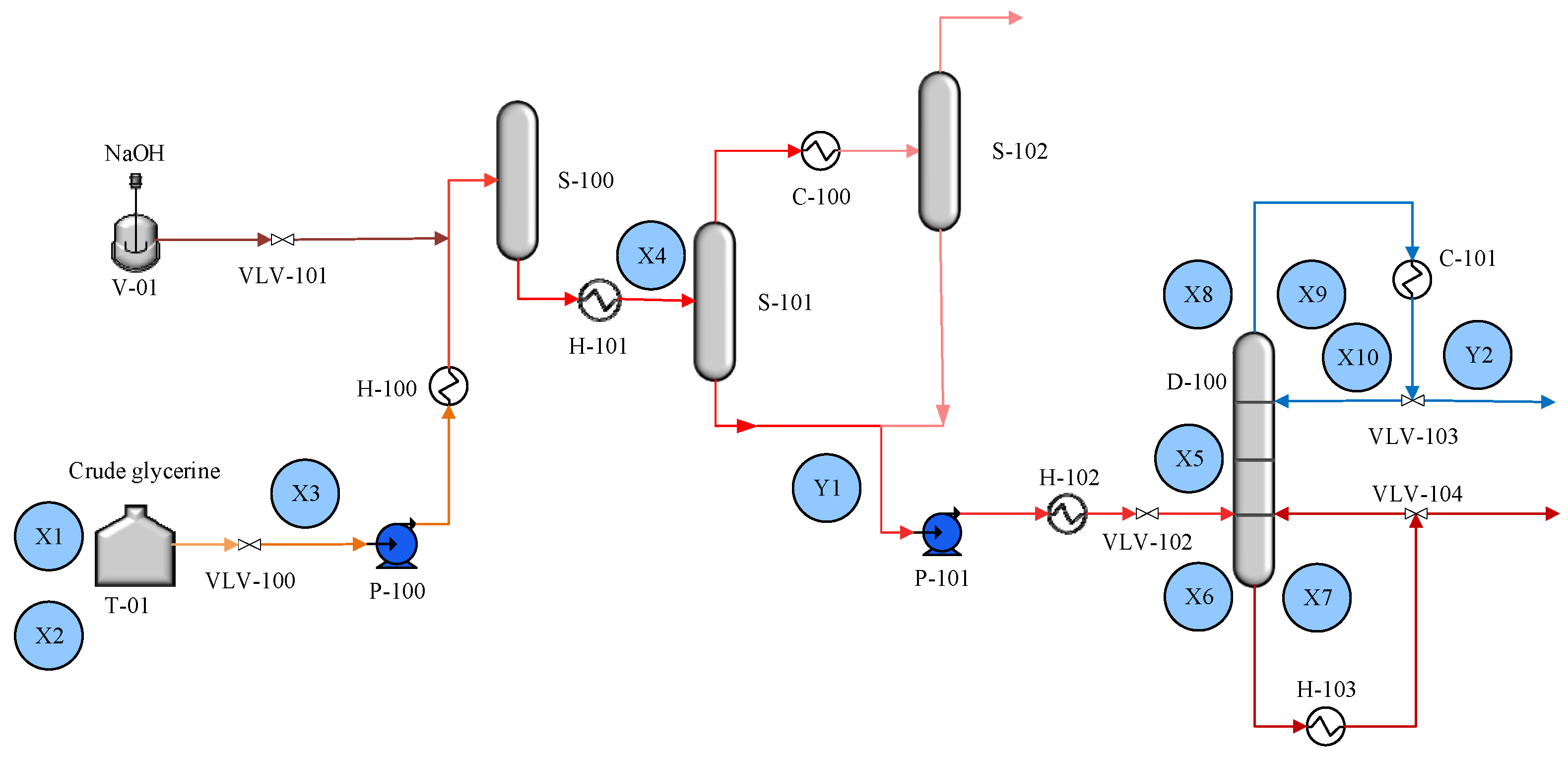

3.1. Process description

3.2. Process simulation modeling

4. Result and Discussion

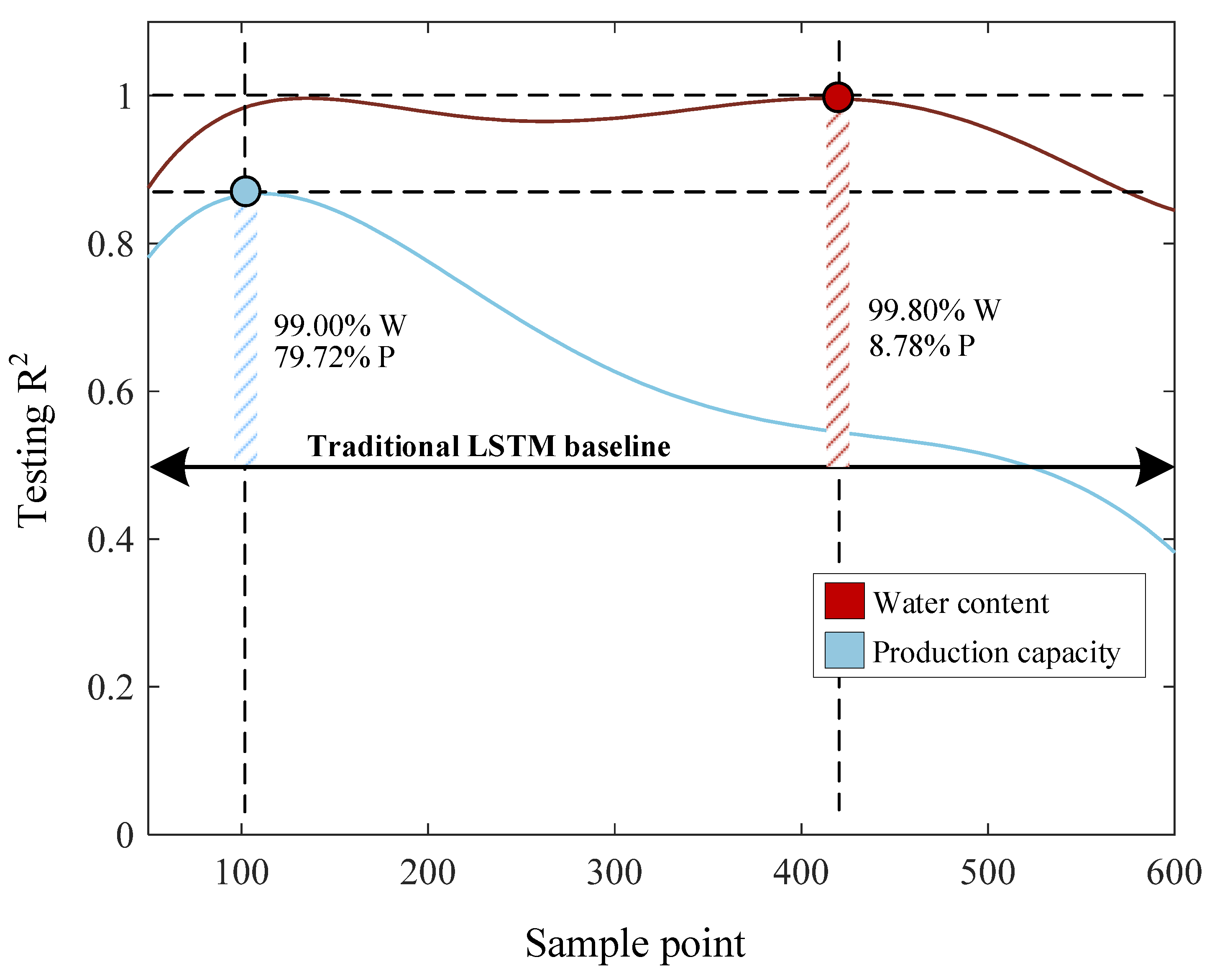

4.1. Water content and production capacity prediction result

4.3. Accuracy-iteration in few-shot learning LSTM tradeoff

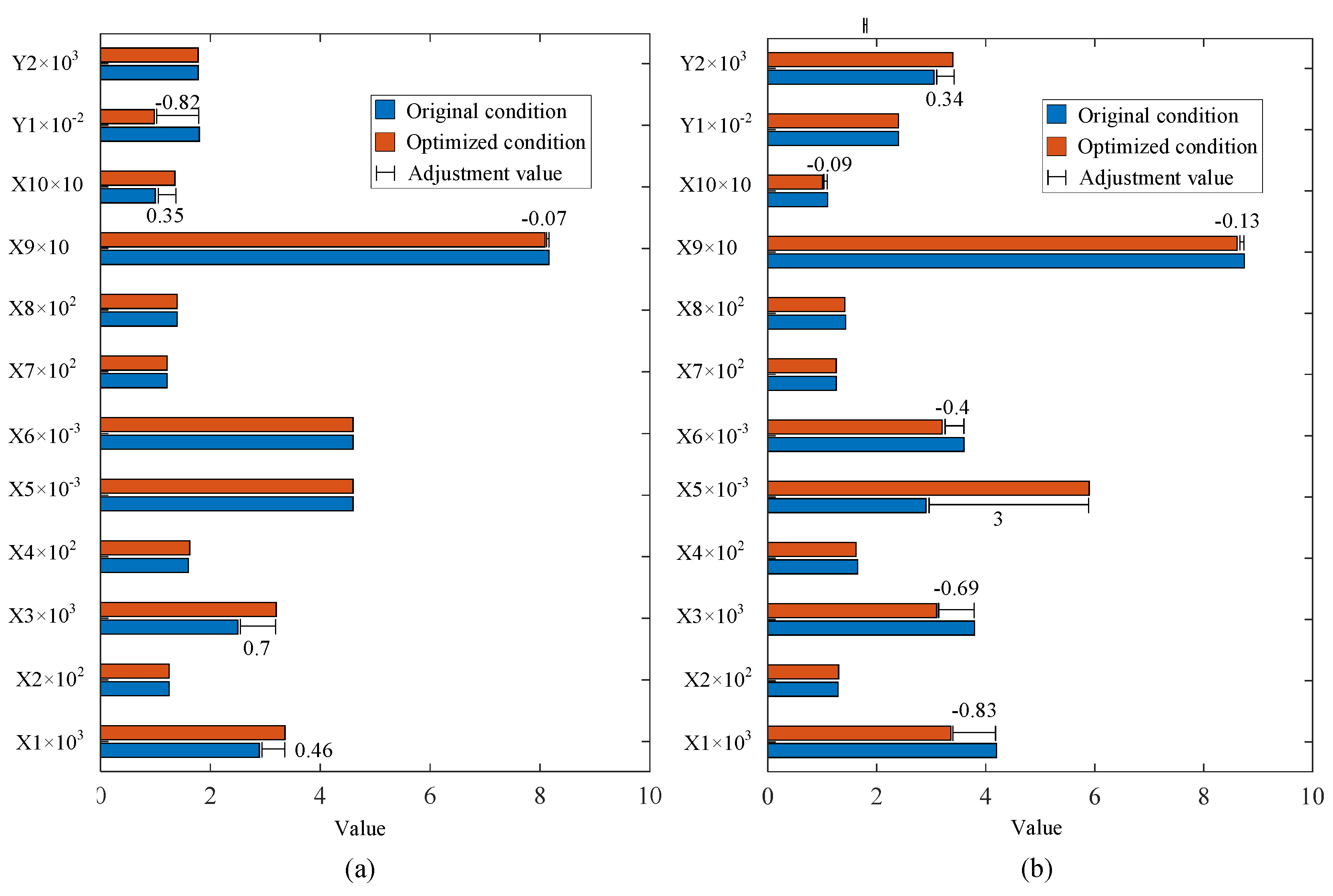

4.4. Production optimization result

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- By utilization of digital-assisted few-shot learing approach, the proposed model achieved 0.895 and 0.955 in prediction R2 of glycerin production and water content, respectively. The incorpolated few-shot learning provides a 99% improvement in water content prediction and a 79.72% improvement in glycerin production over the LSTM baseline.

- (2)

- A simulation model for the glycerin purification process, capable of generating data for model use and determining optimal operating conditions. Though the Bayesian optimization, the updates with a low learning rate are more cautious, leading to a smoother convergence towards the optimal parameters and true function of output variables. This can be crucial for avoiding unstable training and achieving better generalization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moklis, M.H.; Cheng, S.; Cross, J.S. Current and Future Trends for Crude Glycerol Upgrading to High Value-Added Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2979. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Jin, Q. Industrial Waste Valorization. In Green Energy to Sustainability; 2020; pp. 515–537 ISBN 978-1-119-15205-7.

- Sidhu et al. - 2018 - Glycerine Emulsions of Diesel-Biodiesel Blends and.Pdf.

- Sallevelt, J.L.H.P.; Pozarlik, A.K.; Brem, G. Characterization of Viscous Biofuel Sprays Using Digital Imaging in the near Field Region. Applied Energy 2015, 147, 161–175. [CrossRef]

- Panjapornpon, C.; Chinchalongporn, P.; Bardeeniz, S.; Makkayatorn, R.; Wongpunnawat, W. Reinforcement Learning Control with Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithm for Multivariable pH Process. Processes 2022, 10, 2514. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hou, G.-Y.; Shao, W.; Chen, J. A Supervised Functional Bayesian Inference Model with Transfer-Learning for Performance Enhancement of Monitoring Target Batches with Limited Data. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2023, 170, 670–684. [CrossRef]

- Jan, Z.; Ahamed, F.; Mayer, W.; Patel, N.; Grossmann, G.; Stumptner, M.; Kuusk, A. Artificial Intelligence for Industry 4.0: Systematic Review of Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 216, 119456. [CrossRef]

- Quah, T.; Machalek, D.; Powell, K.M. Comparing Reinforcement Learning Methods for Real-Time Optimization of a Chemical Process. Processes 2020, 8, 1497. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-J.; Fan, S.-K.S.; Hsu, C.-Y. A Review on Fault Detection and Process Diagnostics in Industrial Processes. Processes 2020, 8, 1123. [CrossRef]

- Thebelt, A.; Wiebe, J.; Kronqvist, J.; Tsay, C.; Misener, R. Maximizing Information from Chemical Engineering Data Sets: Applications to Machine Learning. Chemical Engineering Science 2022, 252, 117469. [CrossRef]

- Panjapornpon, C.; Bardeeniz, S.; Hussain, M.A. Improving Energy Efficiency Prediction under Aberrant Measurement Using Deep Compensation Networks: A Case Study of Petrochemical Process. Energy 2023, 263, 125837. [CrossRef]

- Moghadasi, M.; Ozgoli, H.A.; Farhani, F. Steam Consumption Prediction of a Gas Sweetening Process with Methyldiethanolamine Solvent Using Machine Learning Approaches. International Journal of Energy Research 2021, 45, 879–893. [CrossRef]

- Panjapornpon, C.; Bardeeniz, S.; Hussain, M.A.; Vongvirat, K.; Chuay-ock, C. Energy Efficiency and Savings Analysis with Multirate Sampling for Petrochemical Process Using Convolutional Neural Network-Based Transfer Learning. Energy and AI 2023, 14, 100258. [CrossRef]

- Wiercioch, M.; Kirchmair, J. Dealing with a Data-Limited Regime: Combining Transfer Learning and Transformer Attention Mechanism to Increase Aqueous Solubility Prediction Performance. Artificial Intelligence in the Life Sciences 2021, 1, 100021. [CrossRef]

- Aghbashlo, M.; Peng, W.; Tabatabaei, M.; Kalogirou, S.A.; Soltanian, S.; Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Mahian, O.; Lam, S.S. Machine Learning Technology in Biodiesel Research: A Review. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2021, 85, 100904. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.-M.; Geng, Z.-Q.; Zhu, Q.-X. Energy Optimization and Prediction of Complex Petrochemical Industries Using an Improved Artificial Neural Network Approach Integrating Data Envelopment Analysis. Energy Conversion and Management 2016, 124, 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Fan, C.; Xu, M.; Geng, Z.; Zhong, Y. Production Capacity Analysis and Energy Saving of Complex Chemical Processes Using LSTM Based on Attention Mechanism. Applied Thermal Engineering 2019, 160, 114072. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Du, Z.; Geng, Z.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y. Novel Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network Considering Virtual Data Generation for Production Prediction and Energy Structure Optimization of Ethylene Production Processes. Chemical Engineering Science 2023, 267, 118372. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhu, X.; Anduv, B.; Jin, X.; Du, Z. Digital Twins Model and Its Updating Method for Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning System Using Broad Learning System Algorithm. Energy 2022, 251, 124040. [CrossRef]

- Bardeeniz, S.; Panjapornpon, C.; Fongsamut, C.; Ngaotrakanwiat, P.; Azlan Hussain, M. Digital Twin-Aided Transfer Learning for Energy Efficiency Optimization of Thermal Spray Dryers: Leveraging Shared Drying Characteristics across Chemicals with Limited Data. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 122431. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Gonzalez, J.I.M.; Elkamel, A.; Budman, H. Hierarchical Deep LSTM for Fault Detection and Diagnosis for a Chemical Process. Processes 2022, 10, 2557. [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of FNN hidden layers | [1– 100] |

| Number of LSTM hidden node | [1-5] |

| Number of LSTM hidden layersNumber of LSTM hidden node | [1– 100][1-5] |

| Number of NARX hidden layers | [1– 100] |

| Delay of NARX network | [1-5] |

| Number of RNN hidden layers | [1– 100] |

| Delay of RNN network | [1-5] |

| Initial learning rate | [1e-001 – 1e-005] |

| L2 Regularization | [1e-001 – 1e-004] |

| Max training iteration | 500 |

| Optimizer | [Adam, RMSProp, SDG] |

| Operation | Equipment | Unit | Duty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuralization process | Gibbs reactor | S-100 | A vessel that occurs in a transesterification reaction to obtain an outlet glycerin stream. |

| Evaporate process | Heater | H-101 | Heat mixed glycerin stream to 120 °C |

| Evaporator 1 | S-101 | Evaporator vapor stream and liquid glycerin stream | |

| Cooling | C-100 | Condense glycerin in the vapor stream | |

| Evaporator 2 | S-102 | Evaporate condenses glycerin and vapor of impurity | |

| Pump | P-101 | Boost pressure | |

| Purification process | Distillation column | D-100 | Purified glycerin to the desired purity |

| Condenser | C-101 | Condense an alloy glycerin to distillate | |

| Reboiler | H-103 | Heat glycerin returns to distillation and to the bottom product |

| No. | Variable name | No. | Variable name |

| X1 | Glycerin content in feed, wt.% | X7 | D-100 bottom pressure, bar |

| X2 | Water content in a feed, wt.% | X8 | D-100 top temperature, oC |

| X3 | Feed mass flow rate, kg/h | X9 | D-100 top pressure, bar |

| X4 | S-101 inlet temperature, oC | X10 | Top temperature of side steam D-100, oC |

| X5 | Distillation column feed rate, kg/h | Y1 | Production capacity, kg/h |

| X6 | D-100 bottom temperature, oC | Y2 | Remaining water at evaporator outlet, wt.% |

| Name variable | Units | Setpoint | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feed crude glycerin | |||

| Feed mass flow rate | kg/h | 3000 | [2500-400] |

| Component | |||

| Glycerin | wt.% | 88 | [80-90] |

| Water | wt.% | 10 | [10-20] |

| Evaporator | |||

| Inlet temperature | oC | 120 | [120-134] |

| Distillation column | |||

| Feedrate | kg/h | 2700 | [2300-3000] |

| Top temperature | oC | 125 | [125-130] |

| Top pressure | bar | 0.0025 | [0.001-0.005] |

| Bottom temperature | oC | 160 | [155-165] |

| Bottom temperature | bar | 0.0045 | [0.002-0.007] |

| Return top temperature | oC | 134 | [130-137] |

| Method | MSE | MAE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| FNN | 0.009 | 0.038 | 0.793 |

| RNN | 0.067 | 0.099 | 0.204 |

| NARX | 0.075 | 0.105 | 0.149 |

| LSTM | 0.009 | 0.043 | 0.801 |

| FSL-LSTM | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.995 |

| Method | MSE | MAE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| FNN | 0.011 | 0.054 | 0.541 |

| RNN | 0.028 | 0.056 | 0.309 |

| NARX | 0.036 | 0.055 | 0.397 |

| LSTM | 0.012 | 0.057 | 0.498 |

| FSL-LSTM | 0.009 | 0.050 | 0.895 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).