Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined by decreased kidney function demonstrated by glomerular filtration (GFR) rate of 60 mL/min per 1·73 m

2, or markers of kidney damage, or both for at least 3 months duration [

1]. As of 2022 nearly 800 million individuals were diagnosed with CKD worldwide accounting for nearly 10% of the population [

2] and the prevalence of CKD has been increasing in many studies worldwide [

2]. incidence of CKD increased by 302% in the Arab world between 1990 and 2019 [

3] which can be explained by the rise in prevalence of CKD risk factors which include family history, males, older age, smoking, diabetes and hypertension [

4] Diabetes and hypertension are the leading cause of CKD [

1] with DM causing 30 to 50% of all CKD cases worldwide [

5]. DM and hypertension’s prevalence in the middle east have been increasing steadily over the years which can be contributed to lack of physical activity, smoking and obesity among other factors [

6] The cost of care for adults with CKD was estimated to be close to 14000

$ per year for a patient [

7] which bears a heavy burden on patients, their families and the health care system as a whole.

There are many ways to estimate GFR such as inulin clearance which is considered the gold standard [

8] Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD), CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) [

9] and Cockroft-Gault equations [

10] among others. Although Cockroft’s equation is considered one of the best equations and the most commonly used equation for GFR estimation [

11] but it is affected by race, weight and Body Mass Index (BMI) [

9,

11,

12]. In addition MDRD equation is better at estimating GFR for patients with end-stage CKD [

11].

While reviewing literature no papers discussing the causes of CKD among Syrian patients were found but forming an understanding of the epidemiology is crucial since the Syrian crisis has resulted in an increase in chronic diseases like hypertension and DM [

13] which are prominent causes of CKD.

Taking all of the above into consideration the authors conducted this research to study the prevalence of DM type 1 and 2 and hypertension among CKD patients and the relationship between demographic characteristics and CKD and differences between diabetic and non-diabetic CKD patients’ serum creatinine, urea, fasting blood glucose levels and MDRD score in the kidney surgical hospital in Damascus, Syria which is a center specialized in treating kidney and urinary tract diseases.

Methods

An ethical approval from the administration of the Syrian private university was obtained after submitting a proposal detailing how the research will be conducted. The research team was also approved to reach the kidney surgical hospital’s patients’ charts by the administrative of the hospital.

Patients eligible for this study were all patients admitted to the kidney surgical hospital and diagnosed with CKD between 2021 and 2023. Exclusion criteria included patients who continued their treatment outside the hospital, patients who underwent any kind of procedures outside the hospital including bloodwork to ensure that all investigations were done under similar circumstances, patients who refused treatment at any stage of their admission and missing data or damaged charts

604 patients were admitted to the hospital between 2021 and 2023 of which 297 were eligible for the study. The research team extracted the following data manually from the patients’ charts: age, gender, martial states, smoking and drinking states, history of DM and hypertension and serum levels of creatinine, urea and fasting blood glucose on admission.

MDRD score was calculated using an online calculator [

14]. Study data were analyzed with Microsoft Office Excel 2019 and SPSS v.26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative variables were reported as median (IQR), and qualitative variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare kidneys function between diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Spearman’s rank correlation was employed to investigate the relationship between fasting blood glucose and kidney function values among diabetes patients with CKD. A significance level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

The age distribution of our sample was as follows: 18% of patients were 17 years old or below n=18 while 29.3% aged from 18-49 n=87 and lastly 64.6% patients were above 50 n=192.

61.6% of patients in our sample were male n=183 while 38.4 were female n=114

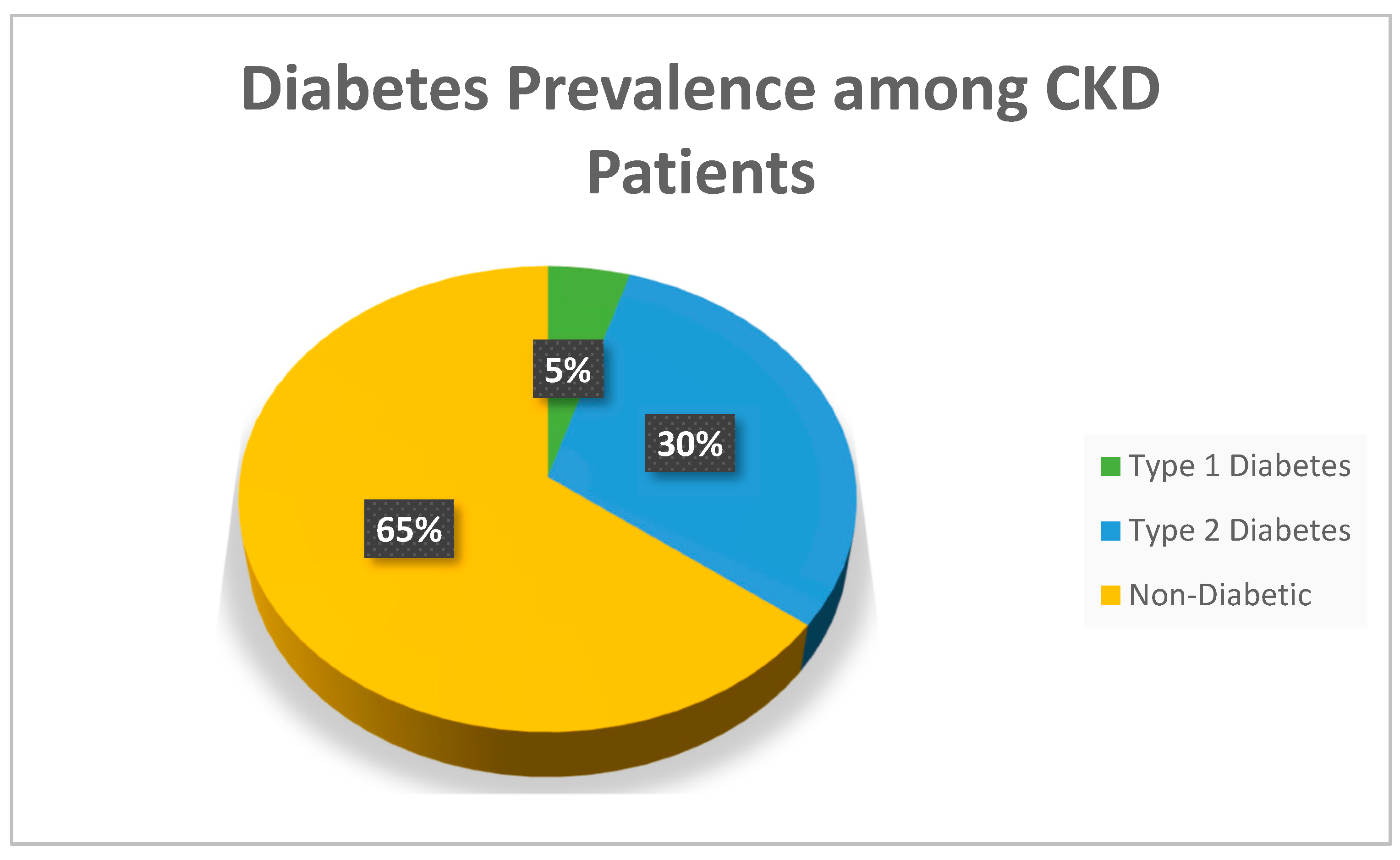

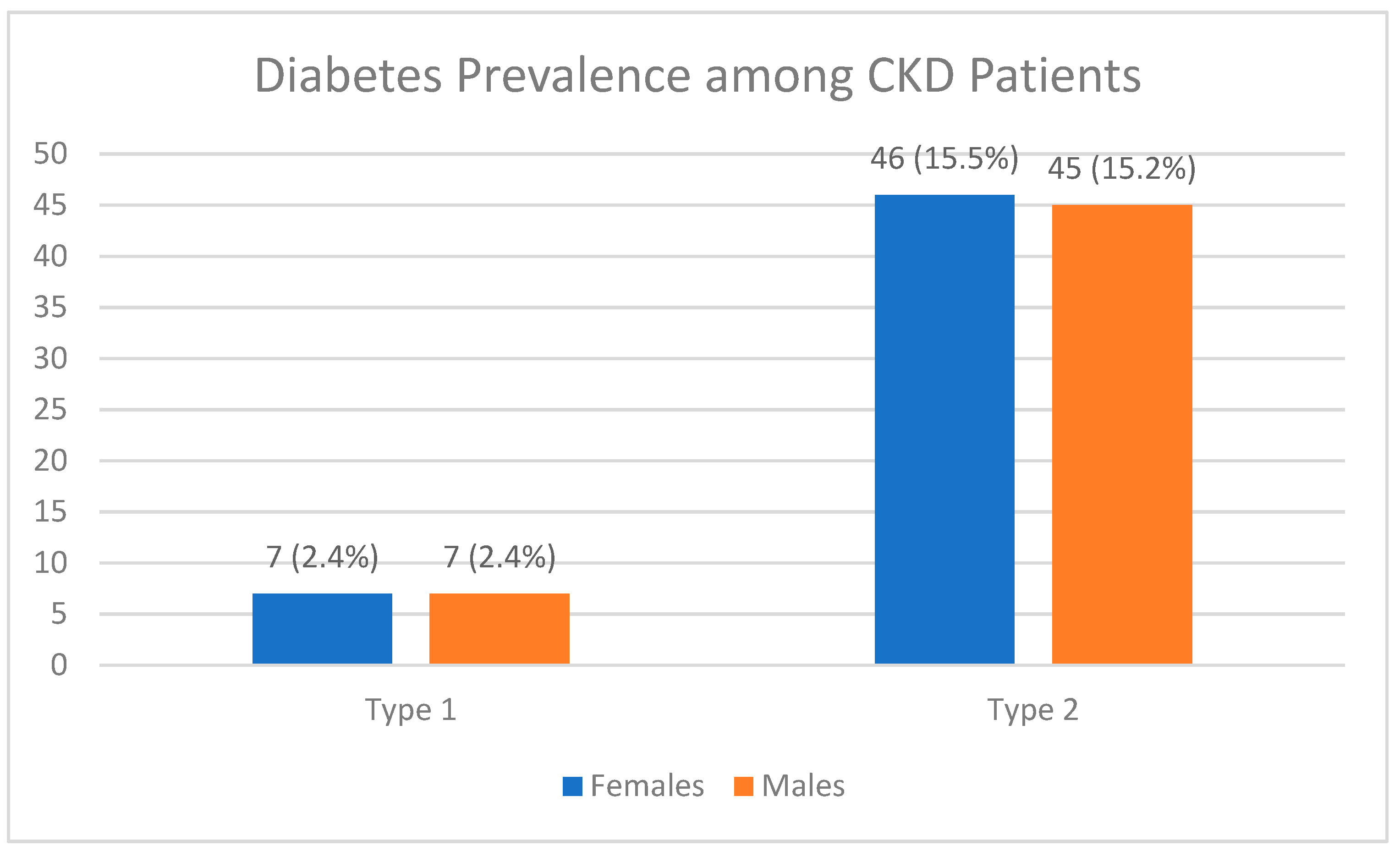

35.4% of patients were diabetics n=105 while 64.4% were not n=192.among diabetic patients 92 had type 2 DM while 14 had type 1 DM. the rest of patients’ characteristics along with the median of each variable are displayed in

Table 1.

Table 2 shows a comparison of MDRD, creatinine, Urea, and fasting blood glucose

Creatinine levels were higher in non-diabetic patients p=0.04 while fasting blood glucose levels were higher in diabetic patients p=0.001. the rest of the comparison is displayed in

Table 2.

No statistically significant correlation was found between fasting blood glucose levels and creatinine, MDRD and Urea levels. P=-0.44, 0.3 and 0.26 respectively. The correlation data is displayed in

Table 3.

Figure 1.

Percentage of diabetic patients among CKD patients (n = 297).

Figure 1.

Percentage of diabetic patients among CKD patients (n = 297).

Figure 2.

Distribution of diabetic CKD patients, broken down by sex and type of diabetes (n = 297).

Figure 2.

Distribution of diabetic CKD patients, broken down by sex and type of diabetes (n = 297).

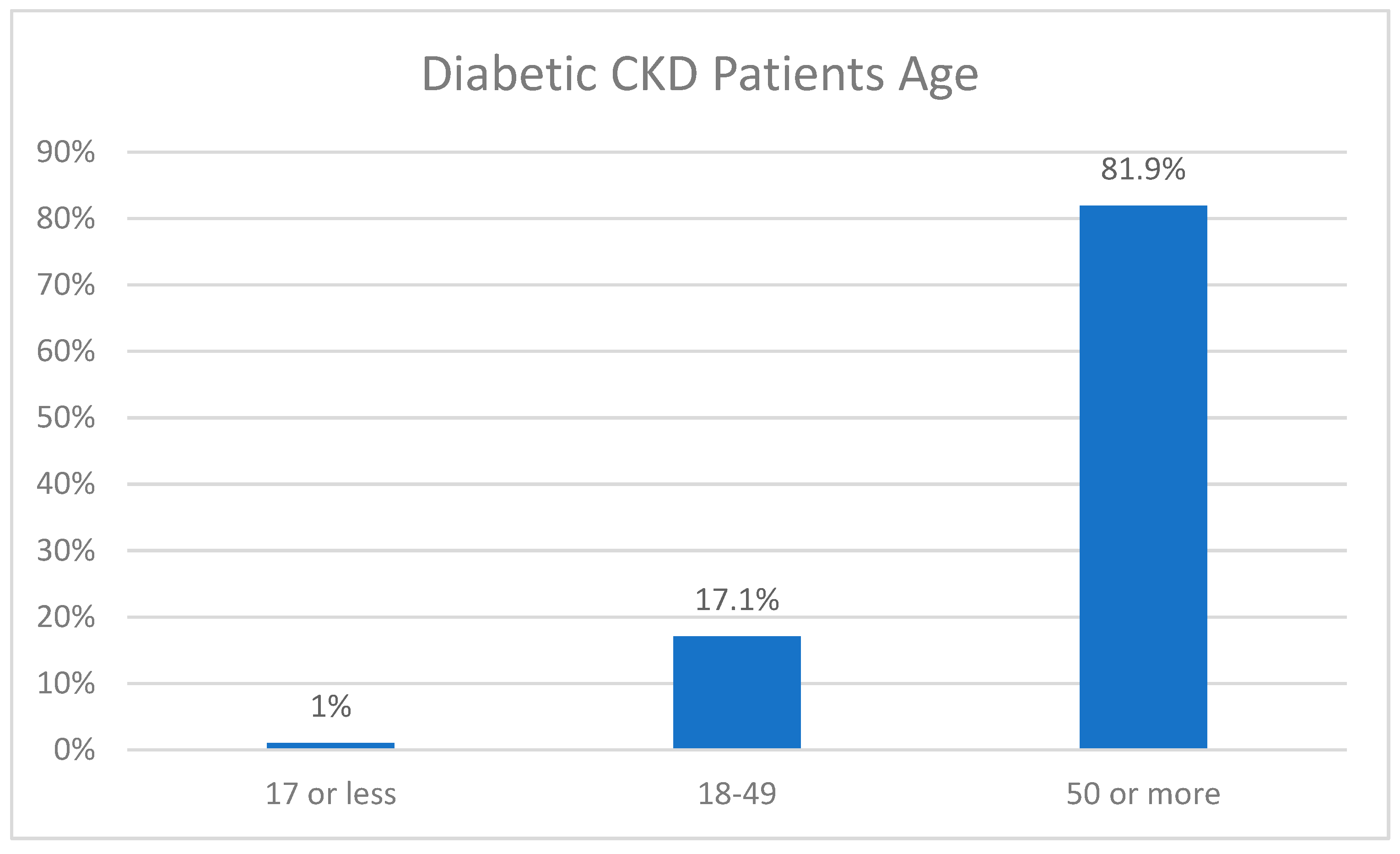

Figure 3.

Distribution of diabetic CKD patients according to age (n = 297).

Figure 3.

Distribution of diabetic CKD patients according to age (n = 297).

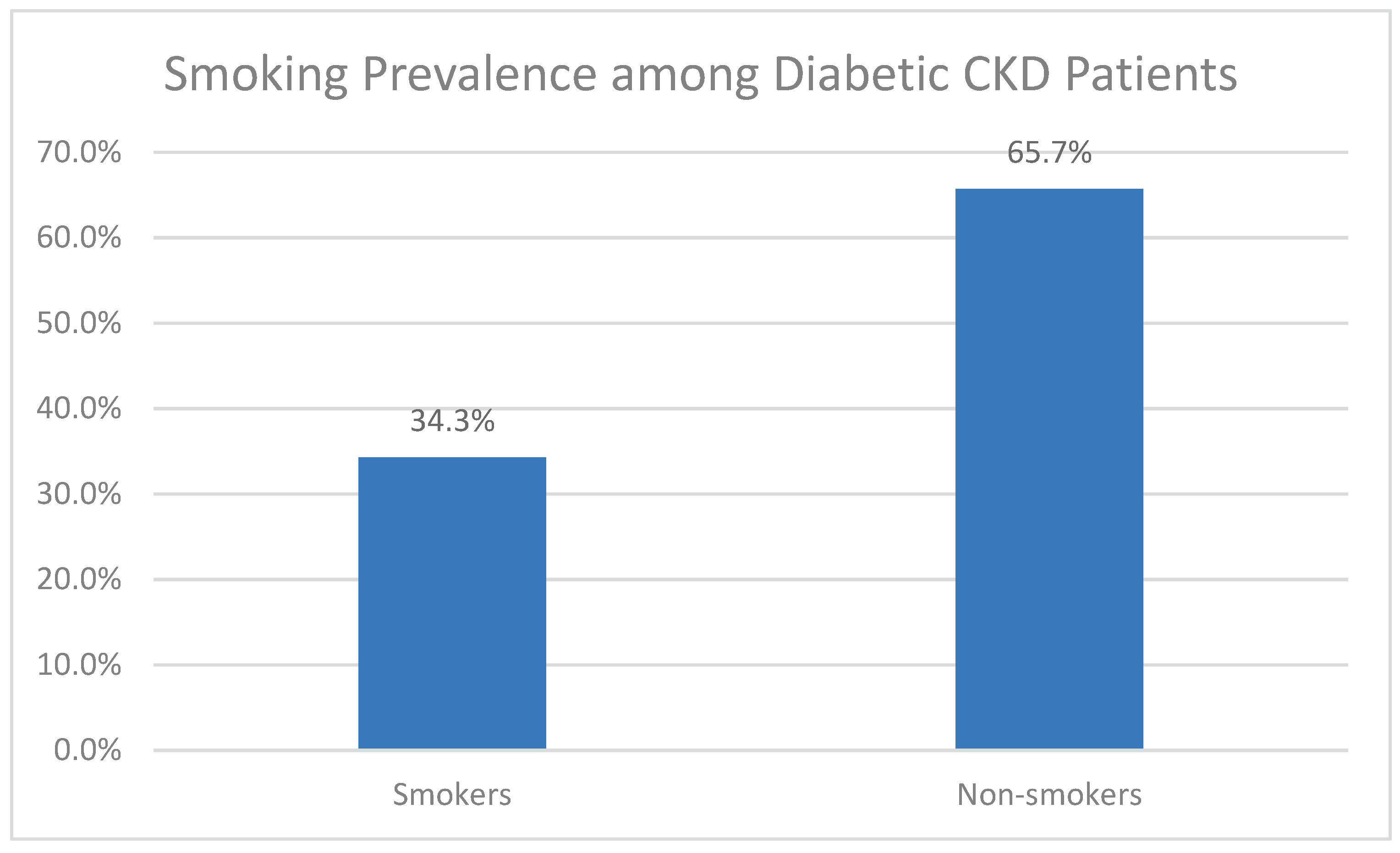

Figure 4.

Percentage of smokers among diabetic CKD patients (n = 297).

Figure 4.

Percentage of smokers among diabetic CKD patients (n = 297).

Discussion

Chronic kidney disease often has a huge impact on the life of the patient finically [

7] it also affects patients psychologically since 50% of patients show signs of depression and anxiety [

15] which lead to low quality of life and poor compliance with treatment resulting in higher mortality rates [

16]. Since most risk factors for CKD are preventable [

17] it’s imperative to understand the epidemiology and causes of CKD to form health policies that serve the well being of patients and society as a whole

The age group of above 50 consisted 65% of patients in our study which consistent with other studies [

18,

19]. These findings are explained by the commonness of DM and hypertension which are common risk factors for CKD among the same age group [

20] as well as the decrease of GFR by 1% per year after the age of 40 [

21]. it’s worth noting that CKD was more prevalent among the age group of 18-49 in our study compared to data from the United States [

22] this could be due to the increased prevalence of DM and hypertension among younger patients in the Middle East [

23] and the commonness of genetic disorders in Arab world [

24].

Nearly 62% of patients in our study were males indicating higher prevalence of CKD among males which contradicts the aforementioned data from the U.S and multiple other studies [

22,

25]. This result can be explained by worse financial and educational states for females compared to males which limit their access to kidney replacement therapy on the other hand males are more likely to reach dialysis stage CKD due to many factors [

26] which was most likely the case in our study in contrast DM is more prevalent among Arab females [

23] which indicates a need for more research into that matter.

DM is considered one of the most important causes of CKD followed by hypertension [

1] and the development of CKD in a diabetic patient increases the risk of death especially for type 2 DM [

27]. 35% of patients in our study were diabetics which a similar percentage to the one observed worldwide which is 30-50% [

28] despite changes in environmental factors such as geography, financial states, the increased risk of DM in the middle east and north Africa which contributed to lack of physical exercise and urbanization and poor nutritional habits [

23] and the latest crisis that Syria has been facing which led to an increase in chronic diseases including DM and hypertension [

13]. 71.1% of patients on our study were diagnosed with hypertension but since kidney disease can be caused by and causes hypertension at the same whether hypertension was the cause or the result of CKD in our sample is unclear.

Males had higher creatinine and urea levels than females which explained by the increase in muscle mass in males [

29] and since MDRD values are dependent on creatinine levels then it makes sense that MDRD values are higher in males as well. Fasting blood glucose levels were also higher in male patients in our study which is also similar to other studies and caused by the difference in insulin effect and other factors affecting blood glucose between males and females [

30]. One of the interesting results in our study was that creatinine levels were higher in non-diabetic patients which can be due to the early start in kidney replacement therapy in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetics, the close monitoring of creatinine levels in diabetic patients by doctors and the increased GFR values in the early stages of CKD caused by DM due to glomerular hyperfiltration [

31]. Using spearmen’s rank correlation test, there was no statistically significant correlation between the fasting glucose levels and urea, creatinine and MDRD values which is converse to previous studies [

32,

33]. Patients with type 2 diabetes were more prevalent than type 1 which consistent with other previous studies [

34] and since the age group of above 50 is the most prevalent in our study and since increased age is a risk factor for type DM type 2 then this result is explained.

Conclusions

despite increased incidence of DM in the middle east and north Africa and Syria especially due to the Syrian crisis, the prevalence of DM as the cause of CKD remains relatively unchanged.

limitations

More studies with bigger samples are needed to establish a clear image of CKD and its causes in Syria. All patients who underwent any procedures outside the kidney surgical hospital were excluded in ensure that all tests were done under the same circumstances which resulted in decreased sample size. The financial burden of relatively expensive investigations such as Hb1c levels limited our ability to have a clearer image on glucose levels control among CKD patients and its relation with MDRD and other kidney function tests.

Funding

There was no funding source for this study.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Dr. MHD BASHEER ALAMEER for helping write this paper, Dr. OMAR AL EMAM for helping with the data collection and Dr. ANAS BITAR for helping with the statistical analysis of data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declarations Ethical approval and consent to participate

An ethical approval from the vice dean of scientific affairs in Syrian Private University was obtained (approval number: 2008). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- Webster, A.C., et al., Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet, 2017. 389(10075): p. 1238-1252.

- Kovesdy, C.P., Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl (2011), 2022. 12(1): p. 7-11.

- Tabatabaei-Malazy, O., et al., Regional burden of chronic kidney disease in North Africa and Middle East during 1990-2019; Results from Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Front Public Health, 2022. 10: p. 1015902.

- Kazancioğlu, R., Risk factors for chronic kidney disease: an update. Kidney Int Suppl (2011), 2013. 3(4): p. 368-371.

- Alemu, H., W. Hailu, and A. Adane, Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease and Associated Factors among Patients with Diabetes in Northwest Ethiopia: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Current Therapeutic Research, 2020. 92: p. 100578.

- Al-Ghamdi, S., et al., Chronic Kidney Disease Management in the Middle East and Africa: Concerns, Challenges, and Novel Approaches. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis, 2023. 16: p. 103-112.

- Manns, B., et al., The Cost of Care for People With Chronic Kidney Disease. Can J Kidney Health Dis, 2019. 6: p. 2054358119835521.

- White, C.A., et al., Simultaneous glomerular filtration rate determination using inulin, iohexol, and (99m)Tc-DTPA demonstrates the need for customized measurement protocols. Kidney Int, 2021. 99(4): p. 957-966.

- Kuan, Y., et al., GFR prediction using the MDRD and Cockcroft and Gault equations in patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 2005. 20(11): p. 2394-2401.

- Šečić, D., et al., Serum Creatinine versus Corrected Cockcroft-Gault Equation According to Poggio Reference Values in Patients with Arterial Hypertension. Int J Appl Basic Med Res, 2022. 12(1): p. 9-13.

- Fawaz, A. and K.F. Badr, Measuring filtration function in clinical practice. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens, 2006. 15(6): p. 643-7.

- Michels, W.M., et al., Performance of the Cockcroft-Gault, MDRD, and new CKD-EPI formulas in relation to GFR, age, and body size. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2010. 5(6): p. 1003-9.

- Alhaffar, M.H.D.B.A. and S. Janos, Public health consequences after ten years of the Syrian crisis: a literature review. Globalization and Health, 2021. 17(1): p. 111.

- MDRD.

- Guerra, F., et al., Chronic Kidney Disease and Its Relationship with Mental Health: Allostatic Load Perspective for Integrated Care. J Pers Med, 2021. 11(12).

- Muflih, S., et al., Depression symptoms and quality of life in patients receiving renal replacement therapy in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond), 2021. 66: p. 102384.

- Stedman, M., et al., Associations and mitigations: an analysis of the changing risk factor landscape for chronic kidney disease in primary care using national general practice level data. BMJ Open, 2022. 12(12): p. e064723.

- Mallappallil, M., et al., Chronic kidney disease in the elderly: evaluation and management. Clin Pract (Lond), 2014. 11(5): p. 525-535.

- Ji, A., et al., Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease in an Elderly Population from Eastern China. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019. 16(22).

- Naseri, M.W., H.A. Esmat, and M.D. Bahee, Prevalence of hypertension in Type-2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Med Surg (Lond), 2022. 78: p. 103758.

- CDC. 2024; Available from: https://nccd.cdc.gov/ckd/FactorsOfInterest.aspx?type=Age#:~:text=However%2C%20CKD%20becomes%20more%20common,blood%20pressure%2C%20and%20heart%20disease.

- CDC. Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2023. 2023; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/publications-resources/ckd-national-facts.html#:~:text=CKD%20is%20more%20common%20in,%E2%80%9344%20years%20(6%25). 9344.

- El-Kebbi, I.M., et al., Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes in the Middle East and North Africa: Challenges and call for action. World J Diabetes, 2021. 12(9): p. 1401-1425.

- Al-Gazali, L., H. Hamamy, and S. Al-Arrayad, Genetic disorders in the Arab world. Bmj, 2006. 333(7573): p. 831-4.

- Lewandowski, M.J., et al., Chronic kidney disease is more prevalent among women but more men than women are under nephrological care: Analysis from six outpatient clinics in Austria 2019. Wien Klin Wochenschr, 2023. 135(3-4): p. 89-96.

- Harris, R.C. and M.Z. Zhang, The role of gender disparities in kidney injury. Ann Transl Med, 2020. 8(7): p. 514.

- Agarwal R. Pathogenesis of Diabetic Nephropathy. 2021 Jun. In: Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. Arlington (VA): American Diabetes Association; 2021 Jun. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK571720/ doi: 10.2337/db20211-2.

- Aeddula, S.R.V.N.R., Chronic Kidney Disease.

- Hosten AO. BUN and Creatinine. In: Walker HK, H.W., Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 193. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305/.

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F., Gender differences in glucose homeostasis and diabetes. Physiol Behav, 2018. 187: p. 20-23.

- Thomas, M.C., et al., Diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2015. 1: p. 15018.

- Amartey, N.A., K. Nsiah, and F.O. Mensah, Plasma Levels of Uric Acid, Urea and Creatinine in Diabetics Who Visit the Clinical Analysis Laboratory (CAn-Lab) at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. J Clin Diagn Res, 2015. 9(2): p. Bc05-9.

- Pathan, S.B., P. Jawade, and P. Lalla, Correlation of Serum Urea and Serum Creatinine in Diabetics patients and normal individuals.

- Majeed, M.S., F. Ahmed, and M. Teeling, The Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease and Albuminuria in Patients With Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Attending a Single Centre. Cureus, 2022. 14(12): p. e32248.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).