Submitted:

27 February 2024

Posted:

28 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods of Verification of Hypothesis of Electromagnetic Earthquake Triggering by Strong SFs of X-Class

2.1. Testable Hypothesis of Earthquake Triggering by Strong SFs

2.2. Analysis of Geomagnetic Field Variations and Seismic Activity during Strong SFs of X-Class

3. Results of Verification of Hypothesis of Earthquake Triggering by Strong Solar Flares

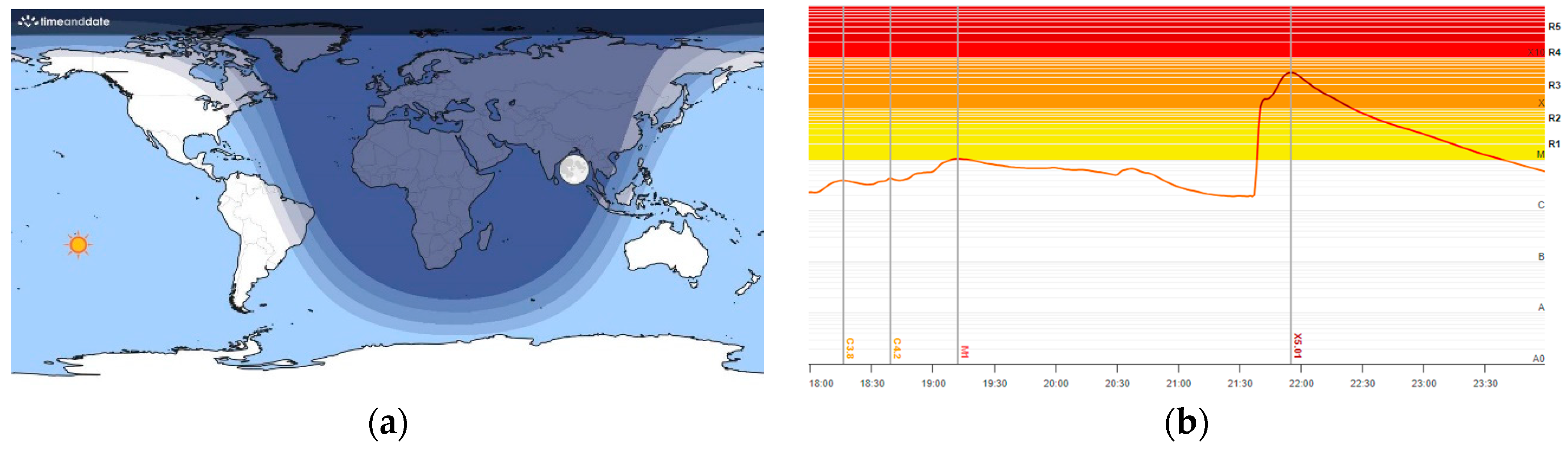

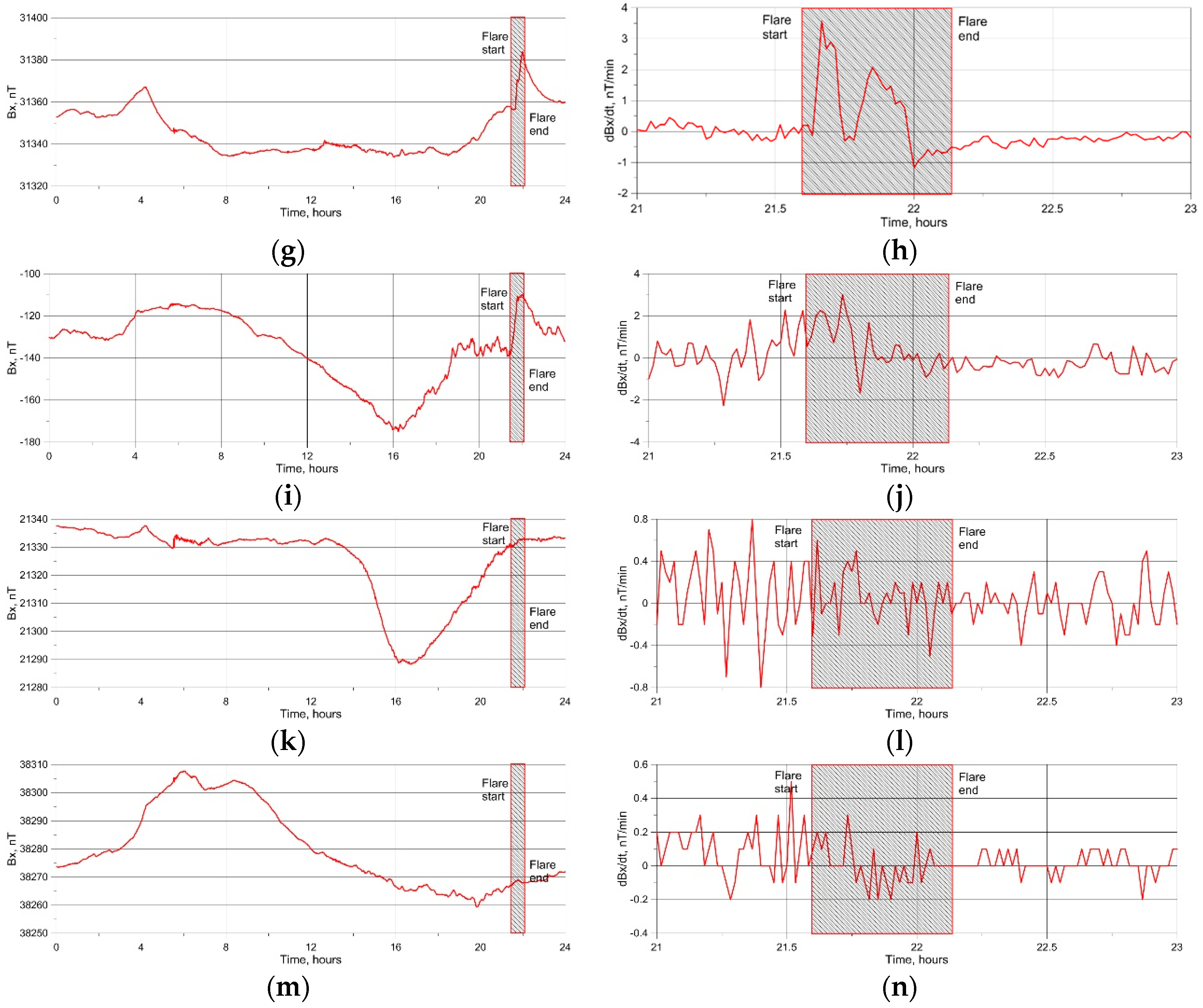

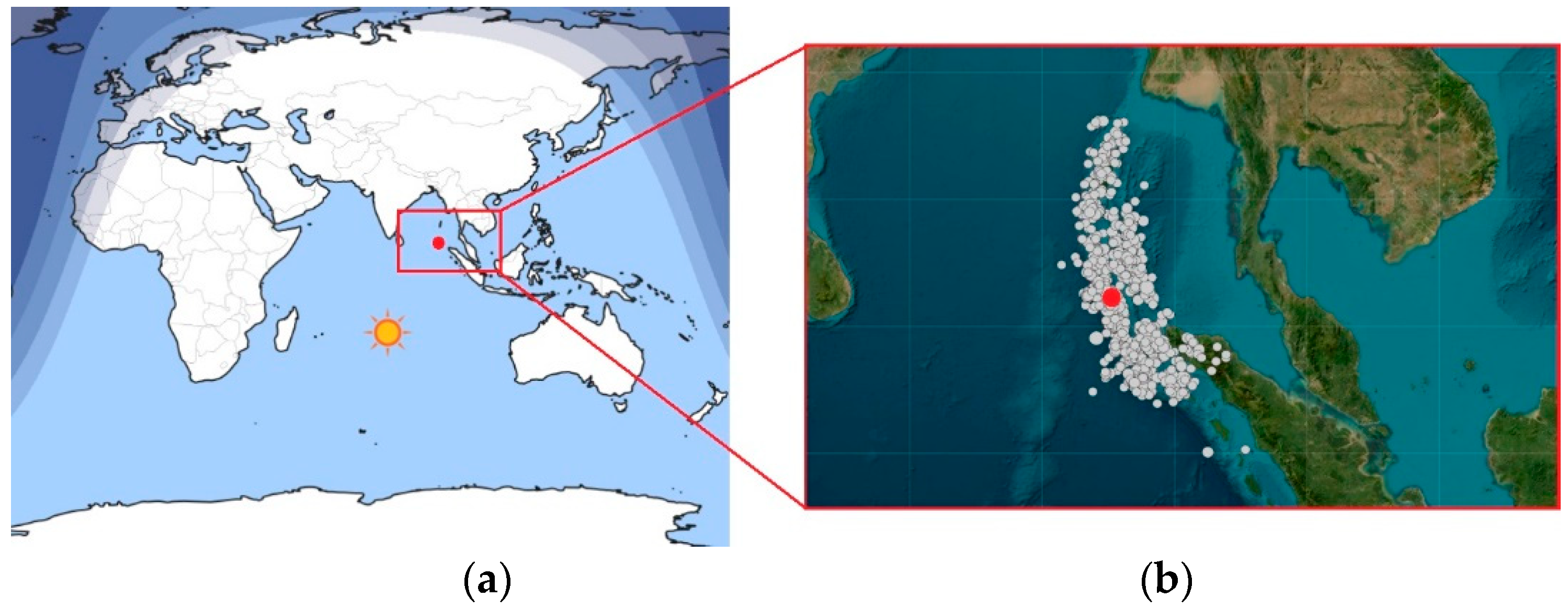

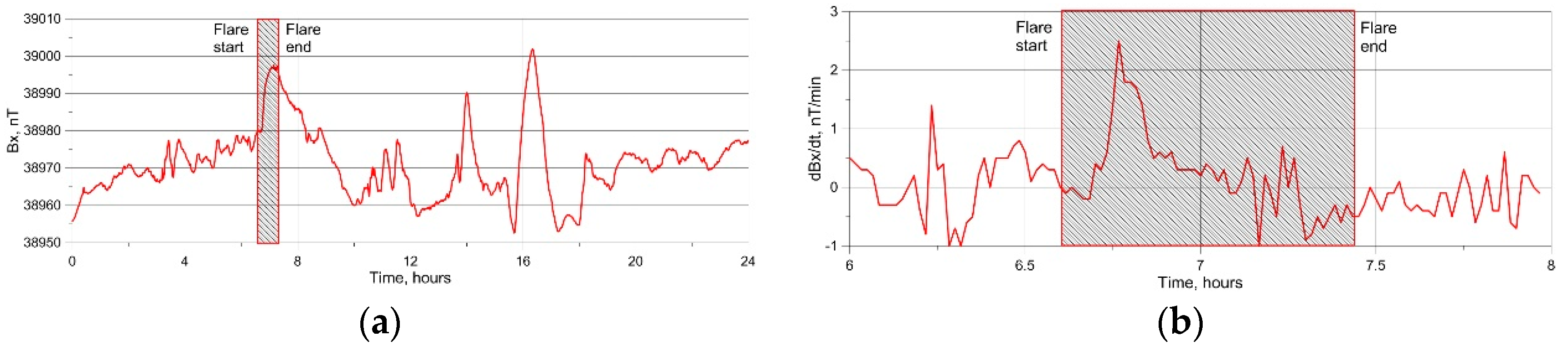

3.1. Response of Geomagnetic Field to Strong Solar Flare: The Case Study of Solar Flare X5.01 of 2023.12.31

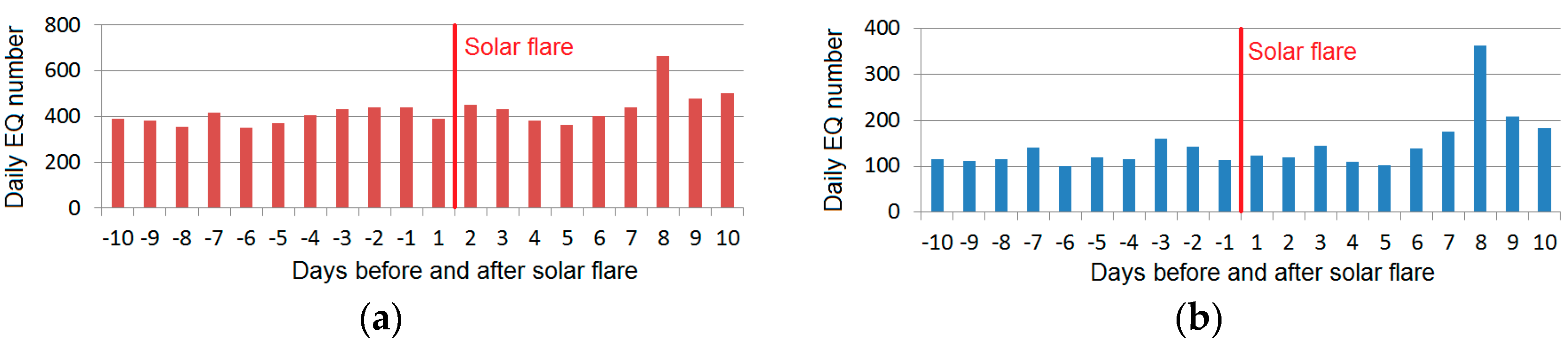

3.2. Seismic Activity before and after Strong SFs of X-Class

4. Discussion

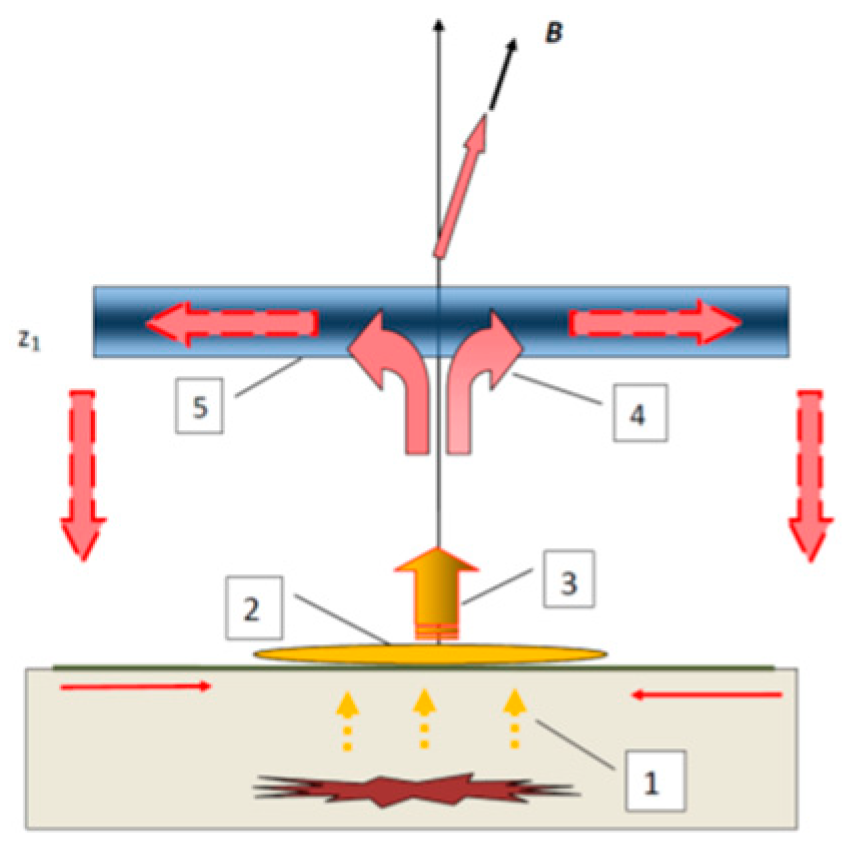

- 1)

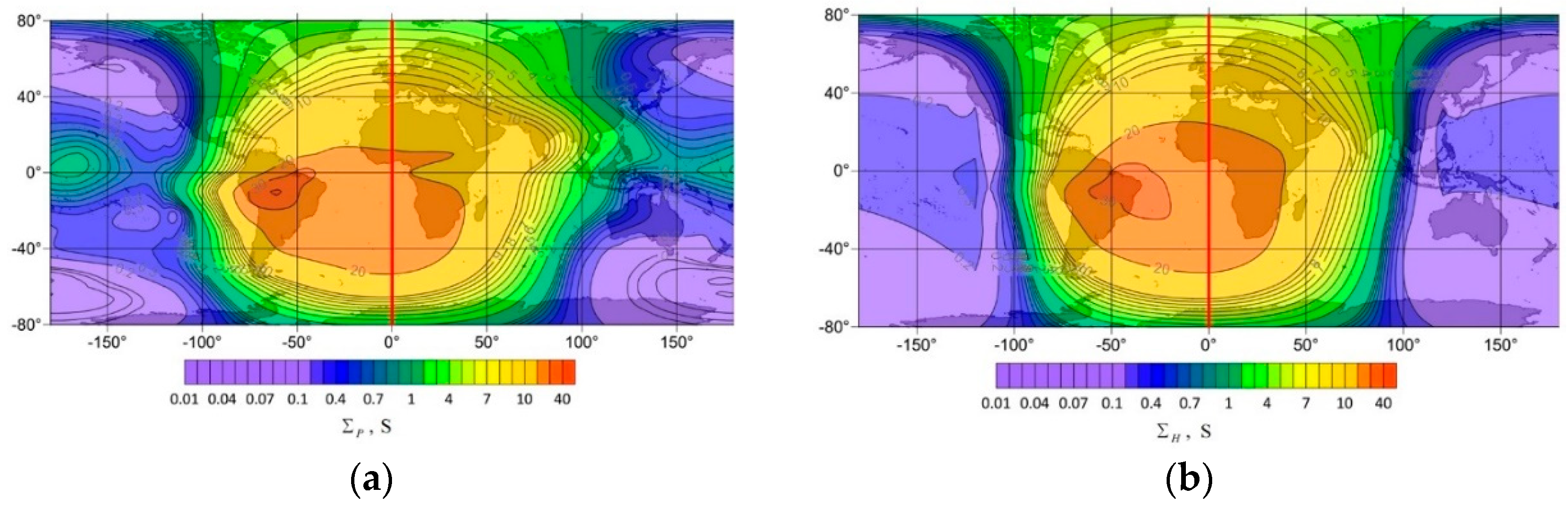

- Pulsations of geomagnetic field predicted by the model [23] due to interaction of X-ray radiation of SFs with ionosphere are observed during the SF on the illuminated part of the globe. The maximal Bx and dBx/dt pulsations are observed in the area of 5000 km radius around the SSP at the time of SF occurrence. With increasing the area radius, Bx and dBx/dt pulsations decrease and practically disappeared at the border of illuminated part. Such pulsations are not observed on the non-illuminated part of the globe.

- 2)

- The observed sharp variations of geomagnetic field are capable to generate GIC in the conductive elements of lithosphere including seismogenic faults. According to the model [23] these GIC are comparable with a splash of telluric currents generated by artificial pulsed power systems resulted in the EQ triggering and spatiotemporal redistribution of seismicity of Northern Tien Shan and Pamir [24]. Our analysis of seismicity after strong SF confirmed the hypothesis of [24] of EM EQ triggering by SFs (Table 2). For illuminated part within 10 days after the X-class SF seismicity increased in comparison with 10 days before the SF by 13.33 to 37.88% depending on the distance from the SSP. It is much more than for consideration of response of seismicity of the whole Earth. This result confirms the hypothesis [23] of EQ triggering by X-ay radiation of the SF and indicates the incorrectness of pure statistical approach to the study of interrelation of solar and seismic activities without of any physical model explained a possible relation between the process on the Sun and the Earth. For further study it looks reasonable to consider the solar-terrestrial relations based on the physical model [23], or any models considered another physical mechanism of these relations provided refined approach to select the data for statistical analysis. The Physics should be ahead of Statistics.

- 3)

- The next finding of the presented analysis is a response of aftershock area to the impact of SF, where the areas of subcritical stress-strain state appear constantly due to redistribution of the stresses in the crust after the main shock. Based on two case studies of aftershock zones of strong EQs of magnitude M7.1 and M9.1 in New Zealand and Indonesia the clear response of aftershock sequences to the SFs of X-class was discovered. The general feature of this response is a 6 to 8 days delay which may indicate a multi-stage physical mechanism of triggering processes in the crust fault including fluid migration under EM impact that require some time for fluid diffusion into the fault reducing its frictional properties and strength.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolf, R. On the periodic return of the minimum of sun-spots: The agreement between those periods and the variations of magnetic declination. Philos. Mag. 1853, 5, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, J.F. Solar activity as a triggering mechanism for earthquakes, Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1967, 3, 417-425. [CrossRef]

- Gribbin, J. Relation of sunspot and earthquake activity. Science 1971, 173, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeus, J. Sunspots and earthquakes. Physics Today 1976, 29, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, F.; Alfonsi, L. Strong earthquakes and geomagnetic jerks: A cause/effect relationship? Ann. Di Geofis. 1995, 38, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, F.; Alfonsi, L.; Piersanti, A.; Spada, G.; Marzocchi, W. Geomagnetic jerks and seismic activity. Ann. Di Geofis. 1996, 39, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, G.A.; Zakrzhevskaya, N.A.; Kharin, E.P. On the relation between seismicity and magnetic storms. Izv. Phys. Solid Earth 2001, 37, 917–927. [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzhevskaya, N.A.; Sobolev, G.A. On the seismicity effect of magnetic storms. Izv. Phys. Solid Earth 2002, 38, 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sobolev, G.A. The effect of strong magnetic storms on the occurrence of large earthquakes. Izv. Phys. Solid Earth 2021, 57, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duma, G.; Ruzhin, Y. Diurnal changes of earthquake activity and geomagnetic Sq-variations. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2003, 3, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odintsov, S.; Boyarchuk, K.; Georgieva, K.; Kirov, B.; Atanasov, D. Long-period trends in global seismic and geomagnetic activity and their relation to solar activity. Phys. Chem. Earth 2006, 31, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeh, T.; Miranda, M.; Hvozdara, M. Strong earthquakes associated with high amplitude daily geomagnetic variations. Nat. Hazards 2010, 53, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, M.; Azevedo, A. Influence of solar cycles on earthquakes. Natural Science. 2011, 3, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestopalov, I.P.; Kharin, E.P. Relationship between solar activity and global seismicity and neutrons of terrestrial origin. Russ. J. Earth Sci. 2014, 14, ES1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, N.; Duma, G.; Freund, F. Geomagnetic Kp Index and Earthquakes. Open Journal of Earthquake Research, 2018, 7, 39-52. 7. [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Yashchenko A.K., Novikov V.A. A possible mechanism of stimulation of seismic activity by ionizing radiation of solar flares. Earthq. Sci., 2019: 32, 1, 26-34. 32. [CrossRef]

- Marchitelli, V.; Harabaglia, P.; Troise, C.; De Natale, G. On the Correlation between Solar Activity and Large Earthquakes Worldwide. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novikov, V.; Ruzhin, Y.; Sorokin, V.; Yaschenko, A. Space weather and earthquakes: Possible triggering of seismic activity by strong solar flares. Ann. Geophys. 2020, 63, PA554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, N.T. Effect of Solar Activity on Electromagnetic Fields and Seismicity of the Earth. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth and Env. Sci. 2021, 929, 012019. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, G.; Spyroglou, I.; Rigas, A.; et al. The sun as a significant agent provoking earthquakes. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2021, 230, 287–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, J.J.; Thomas J., N. Insignificant solar-terrestrial triggering of earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondzadeh, M.; De Santis, A. Is the Apparent Correlation between Solar-Geomagnetic Activity and Occurrence of Powerful Earthquakes a Casual Artifact? Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.; Yaschenko, A.; Mushkarev, G.; Novikov, V. Telluric Currents Generated by Solar Flare Radiation: Physical Model and Numerical Estimations. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigarnik, V.A.; Bogomolov, L.M.; Novikov, V.A. Electromagnetic Earthquake Triggering: Field Observations, Laboratory Experiments, and Physical Mechanisms - A Review. Izv., Phys. Solid Earth 2022, 58, 30–58. [CrossRef]

- Lanzerotti, L.J.; Gregori, G.P. Telluric currents: The natural environment and interaction with man-made systems. In The Earth's Electrical Environment; The National Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1986; pp. 232–257. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, J.; Ma, L. Possible triggering of solar activity to big earthquakes (Ms ≥ 8) in faults with near west-east strike in China. Sci China Ser G: Phy & Ast. 2004, 47, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Scoville, J.; Heraud, J.; Freund, F. Pre-earthquake magnetic pulses. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 1873–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, A.V.; Zotov, O.D. Magnetic perturbations before the strong earthquakes. Izv. Phys. Solid Earth 2012, 48, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INTERMAGNET Data Viewer. Available online: https://imag-data.bgs.ac.uk/GIN_V1/GINForms2 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Real-time data and plots auroral activity. Available online: https://www.spaceweatherlive.com/en/solar-activity/top-50-solar-flares.html (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Day and Night World Map. Available online: https://www.timeanddate.com/worldclock/sunearth.html) (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Search Earthquake Catalog. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/search/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Thomson, A.W.P.; McKay, A.J.; Viljanen, A. A Review of Progress in Modelling of Induced Geoelectric and Geomagnetic Fields with Special Regard to Induced Currents. Acta Geophys. 2009, 57, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavialov, A.D.; Morozov, A.N.; Aleshin, I.M.; Ivanov. S.D.; Kholodkov, K.I.; Pavlenko, V.A. Medium-term Earthquake Forecast Method Map of Expected Earthquakes: Results and Prospects Izv., Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2022, 58, 908–924. [CrossRef]

- Sedghizadeh, M.; Shcherbakov, R. The Analysis of the Aftershock Sequences of the Recent Mainshocks in Alaska. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, E.; Shinohara, M.; Obana, K.; Yamada, T.; Kaneda, Y.; Kanazawa, T.; Suyehiro, K. Aftershock distribution of the 26 December 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake from ocean bottom seismographic observation. Earth Planet Sp. 2006, 58, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.H.; Becker, J.S.; Johnston, D.M.; Rossiter, K.P. An overview of the impacts of the 2010–2011 Canterbury earthquakes. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct, 2015, 14, 6-14. [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Active Faults Database. Available online: https://data.gns.cri.nz/af/ (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Sobolev, G.A. Seismicity dynamics and earthquake predictability. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzeboev, B.A.; Gvishiani, A.D.; Agayan, S.M.; Belov, I.O.; Karapetyan, J.K.; Dzeranov, B.V.; Barykina, Y.V. System-Analytical Method of Earthquake-Prone Areas Recognition. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledo, J.; Jones, A.G.; Ferguson, I.J. Electromagnetic images of a strike-slip fault: The Tintina fault-Northern Canadian. Geophys. Res. Lett 2002, 29, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, M.J.; Malin, P.E.; Egbert, G.D.; Booker, J.R. Internal Structure of the San Andreas Fault Zone at Parkfield, California. Geology 1997, 25, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, M.; Brown, C. A magnetotelluric study of the Alpine Fault, New Zealand. Geophys. J. Int. 1998, 2, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.G.; Kurtz, R.D.; Boerner, D.E.; Craven, J.A.; McNeice, G.W.; Gough, D.I.; DeLaurier, J.M.; Ellis, R.G. Electromagnetic constraints on strike-slip fault geometry - The Fraser River fault system. Geology 1992, 20, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, W.D.; Labson, V.F.; Nokleberg, W.J.; Csejtey, B.; Fisher, M.A. The Denali fault system and Alaska Range of Alaska: Evidence for underplated Mesozoic flysch from magnetotelluric surveys. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1990, 102, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, R.L.; Livelybrooks, D.W.; Madden, T.R.; Larsen, J.C. A magnetotelluric investigation of the San Andreas Fault at Carrizo Plain, California. Geoph. Res. Lett. 1997, 24, 1847–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Wu, L.X.; Zheng, S.; Bai, Y.; Lv, X. Is there an abnormal enhancement of atmospheric aerosol before the 2008, Wenchuan earthquake? Adv. Space Res. 2004, 54, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Mukai, S.; Singh, R.P. Changes in atmospheric aerosol parameters after Gujarat earthquake of January 26, 2001. Adv. Space Res. 2004, 33, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondzadeh, M. Ant Colony Optimization detects anomalous aerosol variations associated with the Chile earthquake of 27 February 2010. Adv. Space Res. 2015, 55, 1754–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondzadeh, M.; Chehrebargh, F.J. Feasibility of anomaly occurrence in aerosols time series obtained from MODIS satellite images during hazardous earthquakes. Adv. Space Res. 2016, 58, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmyrev, V.M.; Isaev, N.V.; Bilichenko, S.V.; Stanev, G.A. Observation by space-borne detectors of electric fields and hydromagnetic waves in the ionosphere over on earthquake center. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 1989, 57, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousheva, M.; Glavcheva, B.; Danov, D.; Angelov, P.; Hristov, P.; Kirov, B.; Georgieva, K. Satellite monitoring of anomalous effects in the ionosphere probably related to strong earthquakes. Adv. Space Res. 2006, 37, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousheva, M.N.; Glavcheva, R.P.; Danov, D.L.; Hristov, P.L.; Kirov, B.B.; Georgieva, K.Y. Electric field and ion density anomalies in the mid latitude ionosphere: Possible connection with earthquakes? Adv. Space Res. 2008, 42, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousheva, M.; Danov, D.; Hristov, P.; Matova, M. Ionospheric quasi-static electric field anomalies during seismic activity August-September 1981. Nat. Hazard. Earth Sys. 2009, 9, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang X.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Shen, X.; Miao, Y.; Duc, X.; Qian, J. Ground-based and satellite DC-ULF electric field anomalies around Wenchuan M8.0 earthquake. Adv. Space Res. 2012, 50, 85–95. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, X.; Zhao, S.; Yao, L.; Ouyang, X.; Qian, J. The characteristics of quasistatic electric field perturbations observed by DEMETER satellite before large earthquakes. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014, 79, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Chmyrev, V.M.; Yaschenko, A.K. Theoretical model of DC electric field formation in the ionosphere stimulated by seismic activity. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2005, 67, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Yaschenko, A.K.; Hayakawa, M. A perturbation of DC electric field caused by light ion adhesion to aerosols during the growth in seismic-related atmospheric radioactivity. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 7, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Chmyrev, V.M.; Hayakawa, M. Electrodynamic Coupling of Lithosphere–Atmosphere–Lonosphere of the Earth; Nova Science Publishers: NY, 2015; p. 355. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Chmyrev, V.M.; Hayakawa, M. A Review on Electrodynamic Influence of Atmospheric Processes to the Ionosphere. Open J. Earthq. Res. 2020, 9, 113–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Hayakawa, M. Generation of seismic-related DC electric fields and lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Hayakawa, M. Plasma and electromagnetic effects caused by the seismic-related disturbances of electric current in the global circuit. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2014, 8, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Chmyrev, V.M.; Isaev, N.V. A generation model of mall-scale geomagnetic field-aligned plasma inhomogeneities in the ionosphere. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 1998, 60, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmyrev, V.M.; Sorokin, V.M. Generation of internal gravity vortices in the high-latitude ionosphere. J. Atmos. Solar–Terr. Phys. 2010, 72, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmyrev, V.M.; Sorokin, V.M.; Shklyar, D.R. VLF transmitter signals as a possible tool for detection of seismic effects on the ionosphere. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr.Phys. 2008, 70, 2053–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Yoshino, T.; Morgounov, V.A. On the possible influence of seismic activity on the propagation of magnetospheric whistlers at low latitudes. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 1993, 77, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecki, J.; Parrot, M.; Wronovski, R. Studies of electromagnetic field variations in ELF range registered by DEMETER over the Sichuan region prior to the 12 May 2008 earthquake. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 3615–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecki, J.; Parrot, M.; Wronovski, R. Plasma turbulence in the ionosphere prior to earthquakes, some remarks on the DEMETER registrations. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov, N.; Chmyrev, V.; Rybachek, S. A new ionospheric mechanism of electromagnetic ELF precursors to earthquakes. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2001, 63, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Chmyrev, V.M.; Yaschenko, A.K. Ionospheric generation mechanism of geomagnetic pulsations observed on the Earth’s surface before earthquake. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2003, 64, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laptukhov, A.I.; Sorokin, V.M.; Yashchenko, A.K. Disturbance of the ionospheric D region by the electric current of the atmospheric - ionospheric electric circuit. Geomagn. Aeron. 2009, 49(6), 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Yaschenko, A.K.; Hayakawa, M. Formation mechanism of the lower ionosphere disturbances by the atmosphere electric current over a seismic region. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2006, 68, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, P.F.; Piccolo, R.; Castellana, L.; Maggipinto, T.; Ermini, A.; Martellucci, S.; Bellecci, C.; Perna, G.; Capozzi, V.; Molchanov, O.A.; Hayakawa, M.; Ohta, K. VLF-LF radio signals collected at Bari (South Italy): A preliminary analysis on signal anomalies associated with earthquakes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2004, 7, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhnoi, A.A.; Solovieva, M.S.; Molchanov, O.A.; Hayakawa, M.; Maekawa, S.; Biagi, P.F. Anomalies of LF signal during seismic activity in November–December 2004. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2005, 75, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhnoi, A.A.; Molchanov, O.A.; Solovieva, M.S.; Gladyshev, V.; Akentieva, O.; Berthelier, J.J.; Parrot, M.; Lefeuvre, F.; Hayakawa, M.; Castellana, L.; Biagi, P.F. Possible seismo-ionosphere perturbations revealed by VLF signals collected on ground and on a satellite. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 7, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Surkov, V.V.; Fukumoto, Y.; Yonaiguchi, N. Characteristics of VHF over-horizon signals possibly related to impending earthquakes and a mechanism of seismo-atomospheric perturbations. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2007, 69, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Pokhotelov, O.A. The effect of wind on the gravity wave propagation in the Earth’s ionosphere. J. Atmos. Solar–Terr. Phys. 2010, 72, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Pokhotelov, O.A. Model for the VLF-LF radio signal anomalies formation associated with earthquakes. Adv. Space Res. 2014, 54, 2532–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzhin, Y.Y.; Sorokin, V.M.; Yaschenko, A.K. Physical mechanism of ionospheric total electron content perturbations over a seismoactive region. Geomag. Aeron. 2014, 54, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Ruzhin, Y.Y.; Yaschenko, A.K.; Hayakawa, M. Generation of VHF radio emissions by electric discharges in the lower atmosphere over a seismic region. J. Atmos. Solar–Terr. Phys. 2011, 73, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzhin, Y.; Nomicos, C. Radio VHF precursors of earthquakes. Natural Hazards 2007, 40, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.M.; Yaschenko, A.K.; Hayakawa, M. VHF transmitter signal scattering on seismic related electric discharges in the troposphere. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2014, 109, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, Y.; Hayakawa, M.; Yasuda, H. Investigation of over-horizon VHF radio signals associated with earthquakes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2001, 1, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, Y.; Ida, Y.; Goto, T.; Hayakawa, M. Interferometric direction finding of over-horizon VHF transmitter signals and natural VHF radio emissions possibly associated with earthquakes. Radio Sci. 2009, 44, RS2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IAGA Code | Latitude | Longitude | Distance to Subsolar Point R, km |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPT | -17.567 | 210.426 | 640.92 |

| EYR | -43.474 | 172.393 | 4287.45 |

| HON | 21.320 | 202.000 | 5059.38 |

| CTA | -20.090 | 146.264 | 6774.29 |

| AIA | -65.245 | 295.742 | 7388.67 |

| FRD | 38.210 | 282.633 | 10003.97 |

| ABG | 18.638 | 72.872 | 15780.24 |

| ΣR=5000 | ΣR=10000 | Σglobal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | a | b | a | b | |

| 1667 | 1209 | 4507 | 3977 | 8664 | 8140 | |

| ΔEQ, % | 37.88 | 13.33 | 6.44 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).