1. Introduction

Thyroid tumours are classified by listing the major

histologic types: follicular thyroid adenoma (FTA), a benign tumor; papillary

thyroid carcinoma (PTC); follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC); anaplastic thyroid

carcinoma (ATC); and medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) [

1,

2]. The results of large-scale genome analyses,

including TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas), have accumulated. The fourth edition

of the WHO Classification of Endocrine Tumors (WHO 4th), published in 2017,

included information on driver genes for thyroid cancer [

2]. WHO released a beta version of the new

classification of endocrine and neuroendocrine tumors (WHO 5th) in 2022 [

3,

4]. Continuing the trend of the WHO 4th and

taking tumor-specific molecular genetic information into account, the WHO 5th

has been fundamentally revised. It now includes a systematic classification

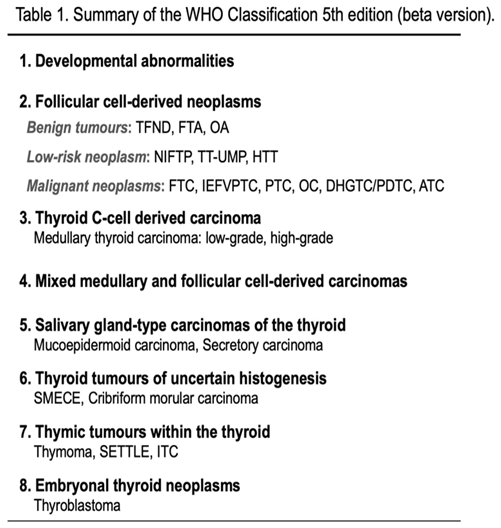

based on the cell-of-origin and the clinical risk (

Table 1). The main categories are follicular

cell-derived neoplasms (FDN) and parafollicular cell (C cell)-derived tumors,

with FDN further divided into three classes: benign, low-risk, and malignant (

Table 1). The only C cell-derived tumor is the

malignant MTC, which has adopted low-grade and high-grade subcategories. Other

tumors are also re-classified as salivary gland-type carcinomas of the thyroid,

thyroid tumours of uncertain histogenesis, thymic tumours within the thyroid,

and embryonal thyroid neoplasms (

Table 2).

This paper outlines eight critical points to better understand the WHO 5th.

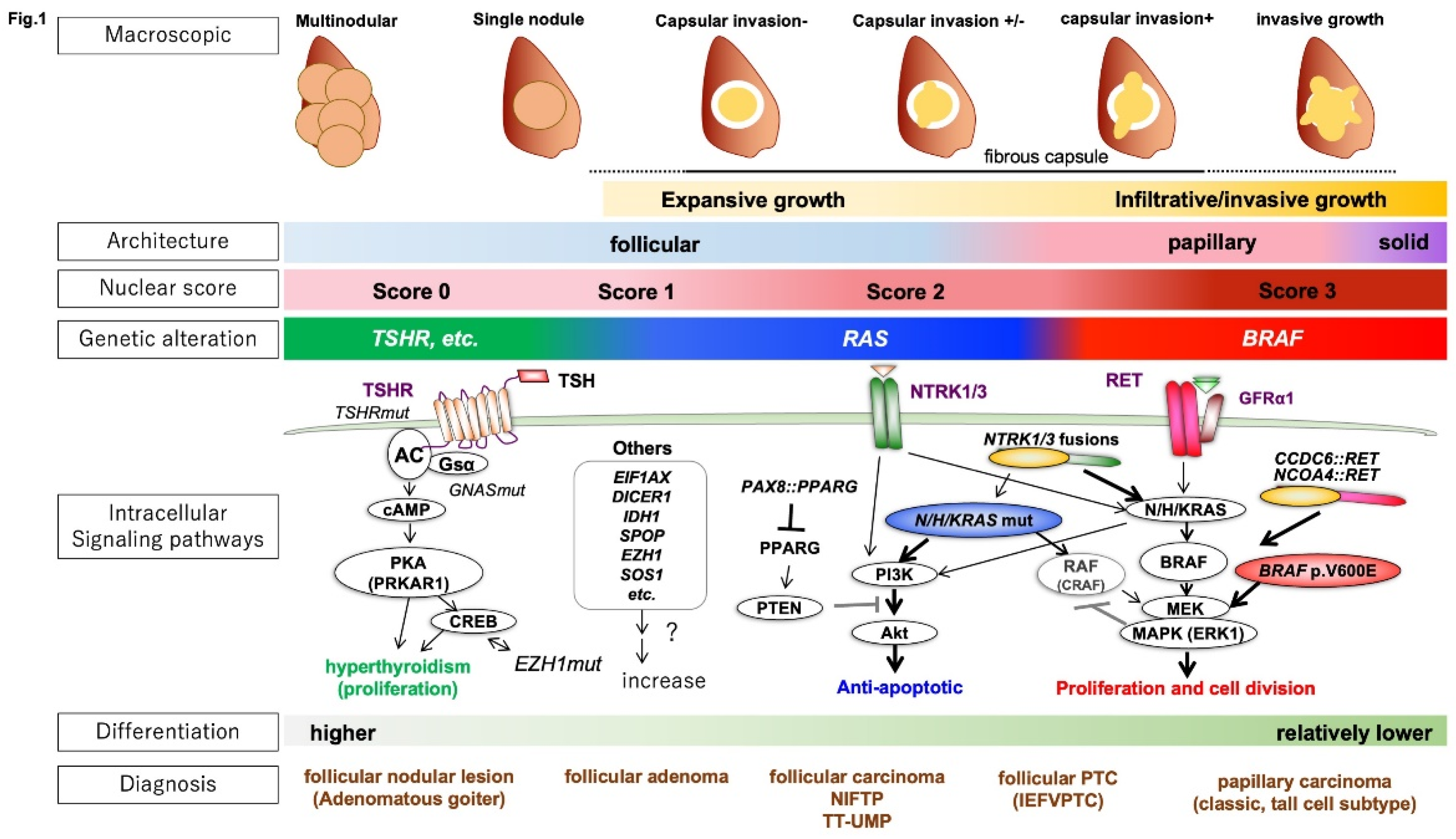

2. Genetic Mutations in Follicular Cell-Derived Tumors (FDN)

In FDN, genetic abnormalities in the MAP kinase pathway, starting from receptor-type tyrosine kinases such as

RET,

RAS, and

BRAF, are the drivers of carcinogenesis [

2,

3,

4,

5]. In differentiated thyroid cancers such as PTC and FTC, a limited number of mutations such as

BRAF p.V600E,

RET translocations,

H/K/NRAS mutations such as

NRAS p.Q61R, and

PAX8::PPARG translocation are often found, which are mutually exclusive. Results of a large-scale thyroid cancer genome analysis [

6] revealed that the type of driver genes correlate well with the morphological classifications (

Figure 1).

The typical FTC has RAS mutations or PAX8::PPARG translocation (PAX8::PPARG fusion protein) as driver gene mutations and grows expansively with retained follicular structure and forming a fibrous capsule. FTC expresses iodine metabolism-related and hormone-related genes, showing thyroidal differentiation. Such tumors are called RAS-like tumors (RLTs) regarding genetic mutations.

On the other hand, the typical PTC has BRAF p.V600E mutations and RET fusion genes and grows invasively with a papillary structure and characteristic nuclear atypia (e.g., ground glass-like chromatin, nuclear grooves, intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions). Such tumors are referred to as BRAF p.V600E-like tumors (BLTs). BLTs have lower iodine metabolic capacity and hormone differentiation compared to RLTs. BRAF p.K601E mutation is found in RLTs. Some tumors are difficult to classify as BLTs or RLTs (non-BRAF/non-RAS tumors: NBNRs).

2.1. Revision of the Framework for Benign Lesions

The fourth edition of WHO (WHO 4th) listed only FTA and Hürthle cell adenoma as benign lesions. The WHO 5th adopted a new category, "developmental abnormalities", such as the thyroglossal duct cyst, and added "thyroid follicular nodular disease (TFND [or multinodular goiter: MND])", which often exhibits clonality [

3,

4,

5], in the benign FDN (

Table 1).

While most FTA are

RLTs, TFND has a cluster of genetic abnormalities in the thyroid stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) and its downstream pathway consisting of Gsα-adenylyl cyclase-protein kinase A (PKA). The most frequent mutation in TFND is

TSHR mutation (~70%)

. Other driver genes in TFND include GNAS, EZH1, ZNF148, and SPOP [

7,

8]. Carney complex, a multiple neoplasia affecting endocrine glands such as the thyroid, is associated with pathological variations in PRKAR1A downstream of cAMP. FTA with papillary architecture is often associated with hyperthyroidism, and like TFND, mutations in

TSHR,

GNAS, PRKAR1A, and EZH1 are common.

2.2. Low-Risk Tumors

"Low-risk tumors" in FDN are morphologically and clinically intermediate between benign and malignant tumors. Low-risk tumors have the potential to metastasize but do so infrequently. Low-risk tumors comprise non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP), thyroid tumors of uncertain malignant potential (TT-UMP), and hyalinizing trabecular tumors (HTT).

NIFTP is an encapsulated FDN with a follicular growth pattern and PTC-like nuclear features, lacking capsular and/or vascular invasion (

Figure 2A-C). NIFTP was previously diagnosed as encapsulated follicular variant PTC, and renamed for a favorable prognosis [

9]. Exclusion criteria for NIFTP are (i) psammoma bodies, (ii) mitotic count of >3 / 2 mm2, (iii) tumor necrosis, and (iv) presence of genetic alterations including

BRAF p.V600E, RET rearrangement, and TERT promoter mutation.

TT-UMPs are defined as tumors of "questionable" capsular or vascular invasion; those without PTC-like nuclear atypia are follicular tumors of uncertain malignant potential (FT-UMPs), and those with PTC-like nuclear atypia are well-differentiated tumors of uncertain malignant potential (WDT-UMPs). These diagnostic terms should be carefully used after a thorough pathological investigation of the specimen.

HTT was first reported by Carney et al. in 1987 as a benign tumor (hyalinizing trabecular "adenoma") and was later renamed after findings suggestive of malignancy, such as lymph node metastasis [

10,

11]. The presence of PTC-like nuclear atypia and the cell membrane staining of Ki-67 (MIB1), but not the nucleus, are key diagnostic features of HTT (

Figure 2D-I). HTT commonly exhibits translocations of

PAX8::GLIS3 (93%) or

PAX8::GLIS1 (7%) [

12].

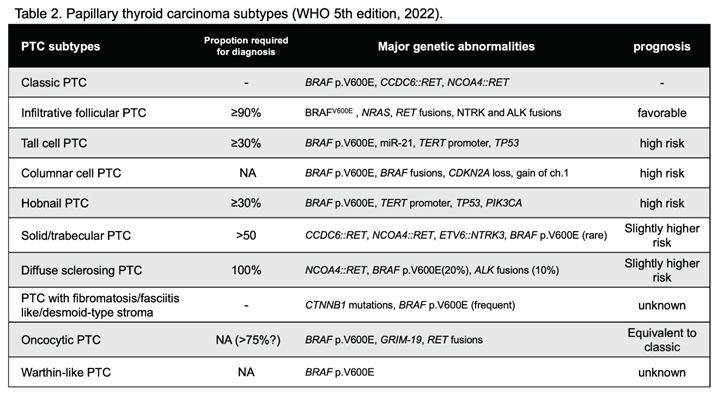

2.3. Subtypes of PTC

PTC subtypes have been described as "variants", but to distinguish them from genetic variants, the term "subtype" is adopted in the WHO 5th (

Table 2). The previous "cribriform morular variant PTC" is "cribriform morular carcinoma" in tumors of uncertain histogenesis. Among the follicular PTCs, those with wide infiltrative growth remain in the PTC subtype as infiltrative follicular PTC (ifPTC), while invasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (IEFVPTC) became a unique classification. This is because the genetic background classifies most ifPTCs as

BRAF tumors and most IEFVPTCs as

RAS tumors.

The subtypes with a poor prognosis include tall cell PTC (tcPTC), hobnail PTC (hPTC), and columnar cell PTC (ccPTC). They are predominantly

BRAF p.V600E mutations and often meet the diagnostic criteria for high-grade differentiated carcinomas as described below. The solid/trabecular PTC (stPTC) is also at slightly higher risk and has a higher frequency of

RET rearrangements. tcPTC and hPTC are diagnosed when they represent more than 30% of all tumors, and stPTC when they represent more than half of all tumors. CDX2 is often positive in ccPTC. The risk of diffuse sclerosing PTC is controversial, but they might have a higher risk [

13].

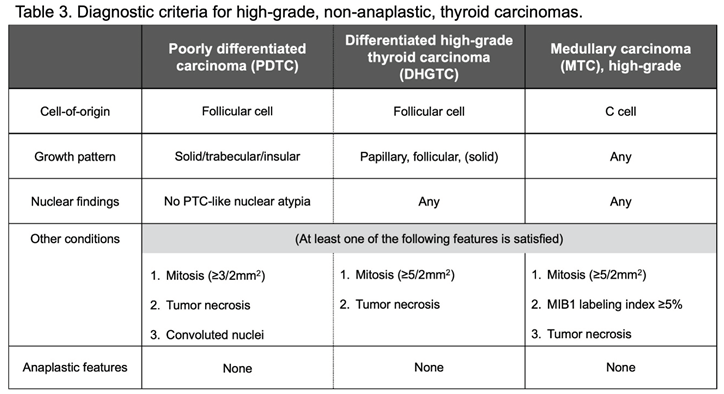

2.4. High-Grade Carcinomas

It has been repeatedly reported that some differentiated follicular cell-derived carcinoma cases, including FTC, PTC, and oncocytic carcinoma (OCA), and MTC cases have a poor prognosis [

3,

4,

5]. The WHO 5th introduced the concept of high-grade carcinomas.

Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (PDTC) has clinicopathological characteristics intermediate between well-differentiated follicular cell-derived carcinoma with excellent prognosis and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC). PDTC is diagnosed based on Turin consensus criteria [

14]: (i) presence of a solid/trabecular/insular growth pattern, (ii) absence of conventional nuclear features of papillary carcinoma, and (iii) presence of at least one of the following: convoluted nuclei, increased mitotic counts (≥ 3 per 2 mm2), tumor necrosis.

In well-differentiated follicular cell-derived carcinomas, there are high-risk cases comparable to PDTC [

15]. These cases are named "differentiated high-grade thyroid carcinoma (DHGTC)" in the WHO 5th and can be morphologically differentiated by increased mitosis (≥5 fissions/2mm

2 ) and tumor necrosis from authentic differentiated thyroid carcinomas (

Figure 3). DHGTC and PDTC comprise a new category, high-grade follicular cell-derived non-anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (

Table 3).

In PDTC and DHGTC, RAS and BRAF mutations are detected at a frequency similar to that in well-differentiated carcinomas. TP53, CDKN2A, PIK3CA, and AKT1 mutations are high-risk mutations related to a poor prognosis and malignant transformation. TERT promoter mutations (C228T and C250T) are also high-risk genetic alterations.

The concept of high-grade carcinoma was also introduced for MTC, a calcitonin-producing C cell-derived carcinoma. MTC exhibits a neuroendocrine differentiation and is a primary neuroendocrine tumor/carcinoma (NET/NEC) of the thyroid gland. Like NET/NEC in other organs, the prognosis for MTC varies significantly from case to case. The tumor proliferative activities can stratify long-term risk for MTC [

16,

17]. The WHO 5th recommended a two-tier risk assessment system based on the proliferative activity and tumor necrosis [

4]: (i) mitotic counts, ≥5cells/2mm

2; (ii) Ki67 labeling index, ≥5%; and (iii) presence of tumor necrosis (

Table 3).

Most cases of hereditary MTC and about half of sporadic MTC have

RET mutations. The second most frequent mutations in sporadic MTC are

RAS mutations. The clinical risk varies depending on the type of

RET mutation, with the frequent

RET p.M918T being the highest-risk mutation [

3,

4,

5].

2.5. Changes in the Definition of Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma (ATC)

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) without a well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma component has been considered a unique histologic type. The WHO 5th edition has incorporated SCC into ATC because SCC of the thyroid generally show

BRAF p.V600E mutations (87%) and are immunohistologically positive for follicular cell markers, PAX8 (91%) and TTF1 (38%) [

3,

4,

5]. SCC of the thyroid also exhibits a poor prognosis comparable to that of other ATCs. Squamous metaplasia of follicular cells and squamous differentiation of PTC should not be mistaken for ATC. Direct invasion of primary SCC of the head and neck region should also be excluded.

2.6. Oncocytic Adenoma and Carcinoma

Hürthle cell adenoma/carcinoma (formerly called follicular adenoma/carcinoma, oxyphilic cell variant) was renamed oncocytic thyroid adenoma (OA)/oncocytic thyroid carcinoma (OCA) in the WHO 5th. The name "Hürthle cell tumor" is no longer used because it is inappropriate. OA/OCA were distinguished from FTA/FTC by their characteristic morphology as well as their unique genetic background [

18,

19]. Oxyphilic PTC is not included in OCA.

The criteria for differentiating OA from OCA are the same as for follicular tumors: the presence of capsular invasion and vascular invasion. Like the subclassification of FTC, OCA is subdivided into three subtypes: minimally invasive, encapsulated angioinvasive, and widely invasive OCA.

OA/OCA has a high frequency of gene mutations in the mitochondrial biosynthesis system, such as ESRRA and PPARGC1A, and has characteristic genetic abnormalities such as a near-haploid (or monoploid) karyotype. OA/OCA, on the other hand, has a low frequency of RAS mutations and PAX8::PPARG translocations, which are the major driver mutations of FN.

2.7. Other Tumors

Other tumors were classified into four categories based on cellular origin or differentiation: (i) salivary gland-type carcinomas of the thyroid, (ii) thymic tumors within the thyroid, (iii) thyroid tumors of uncertain histogenesis, and (iv) embryonal thyroid neoplasms (

Table 1).

Salivary gland-type tumors include mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid (MEC) and secretory carcinoma of salivary gland type (SC). MEC consists predominantly of epidermoid cells admixed with a smaller number of mucocytes. In some MEC cases, CRTC1::MAML2 fusion gene, characteristic of salivary gland MEC, is detected. SC cases commonly involve the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion gene.

Intrathyroid thymic tumors include the thymoma, intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma (ITC), and spindle cell tumor with thymus-like differentiation (SETTLE). The WHO 4th has remained the same for these classifications.

Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia (SMECE) and cribriform morular thyroid carcinoma (CMTC) were classified as tumors of uncertain histogenesis. SMECE was considered a subtype of MEC, but became an independent histologic type due to the absence of MAML2 fusion gene and the presence of Hashimoto's disease in the background. CMTC, which was a subtype of PTC in the WHO 4th, is related to familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and genetic abnormalities in the β-catenin system such as APC. CMTC became independent because they do not show apparent follicular cell differentiation.

Thyroblastoma, has been introduced in a new category of embryonal thyroid neoplasms. Thyroblastoma is a highly aggressive tumor, consisting of primitive thyroid-like follicular cells, a primitive small cell component, and mesenchymal stroma. Most thyroblastoma cases have been classified as malignant thyroid teratoma or carcinosarcoma. DICER1 somatic mutations are common.

Note that lymphomas and mesenchymal tumors have been removed from the specific classification of thyroid tumors because they are now grouped together with other endocrine organs.

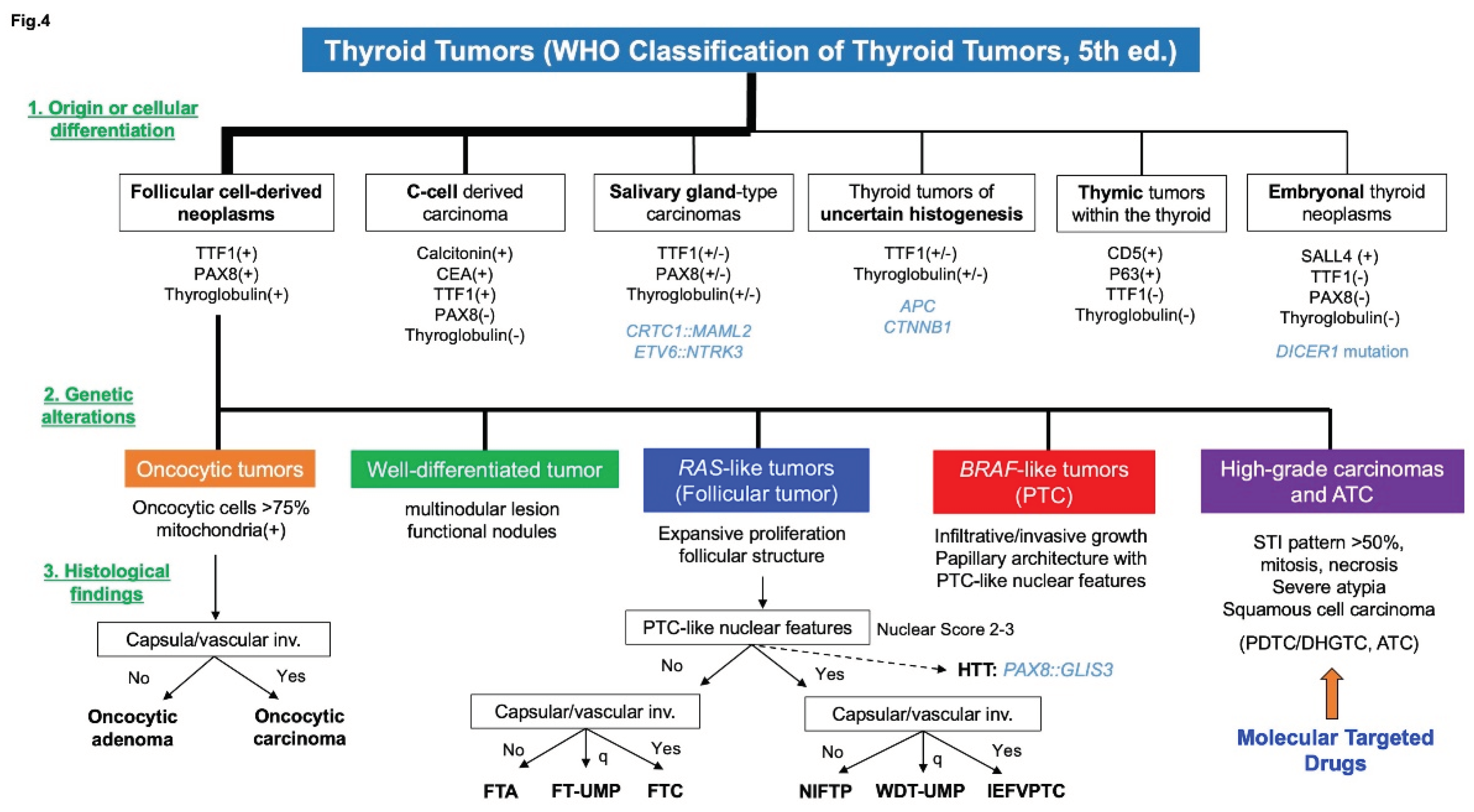

3. Diagnostic Procedure According to WHO 5th

Thyroid tumor diagnosis is principally based on cell-of-origin or tumor differentiation, which is examined by follicular cell markers such as TTF1, PAX8, Thyroglobulin, and other differentiation markers, including calcitonin (

Figure 4). FDNs, most frequent thyroid tumors, are generally classified into five types according to their genetic alterations: (i) oncocytic tumors, (ii) well-differentiated tumors such as thyroid follicular nodular disease, (iii) RLTs, (iv) BLTs, and (v) high-grade carcinomas and ATC. High-grade carcinoma and ATC are associated with high-risk gene mutations such as

TERT promoter mutations,

TP53 mutations, and

CDKN2A/2B loss. These high-risk mutations and morphological characteristics, such as mitosis and tumor necrosis, are used to identify high-grade carcinomas and ATC. Diagnosis of high-grade carcinomas is crucial for early initiation of the molecular targeted therapy because a variety of drugs such as Selpercatinib, Entrectinib, Dabrafenib, and Trametinib are currently available for radioactive iodine-resistant thyroid carcinomas. Unique driver gene mutations such as

APC,

CRTC1::MAML2, and

ETV6::NTRK3, may also be vital in diagnosing tumors other than those of FDNs.

4. Conclusions

The WHO 5th has changed the classification based on background genetic abnormalities. Especially for highly differentiated FDNs, it is essential to classify them into OA/OCA, RLTs, and BLTs. Proper diagnosis of high-grade carcinomas is also critical. Knowledge of genetic alterations have significantly improved pathological diagnosis and selection of treatments, including molecular targeted drugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C), Grant Number JP23K06456. The author thanks the members of the Department of Cytology, and the Department of Pathology, the Cancer Institute Hospital of JFCR, for their essential assistance.

Disclosure

The author does not have any potential conflicts of interest associated with this research.

References

- The Japan Endocrine Surgery Society and The Japanese Society of Thyroid Pathology, eds. Japanese Society of Endocrine Surgery and Japanese Society of Thyroid Pathology ed. Kanehara Publishing. 2019.

- Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, et al.: WHO classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs (4th edition). IARC, Lyon. 2017.

- Asa SL, Baloch ZW, de Krijger RR et al: WHO classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs (5th edition) [Internet]. IARC, Lyon. 2022.

- Baloch ZW, Asa SL, Barletta JA, et al.: Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms. Endocr Pathol 2022, 33, 27–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov YE, Biddinger PW, Thompson LDR.: Diagnostic pathology and molecular genetics of the thyroid. Wolters Kluwer. 3rd edition. 2020; 347–387.

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network: integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell 2014, 159, 676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palos-Paz F, Perez-Guerra O, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, et al.: Prevalence of mutations in TSHR, GNAS, PRKAR1A and RAS genes in a large series of toxic. Eur J Endocrinol 2008, 159, 623. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye L, Zhou X, Huan F, et al.: The genetic landscape of benign thyroid nodules revealed by whole exome and transcriptome sequencing. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 15533. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov YE, Seethala RR, Tallini G, et al.: Nomenclature Revision for Encapsulated Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Paradigm Shift to Reduce Over- treatment of Indolent Tumors. JAMA Oncol 2016, 2, 1023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney JA, Ryan J, Goellner JR.: Hyalinizing trabecular adenoma of the thyroid gland. Am J Surg Pathol 1987, 11, 583–591.

- Carney JA, Hirokawa M, Lloyd RV, et al: Hyalinizing trabecular tumors of the thyroid gland are almost all benign. Am J Surg Pathol 2008, 32, 1877–1889. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforova MN, Nikitski AV, Panebianco F, et al.: GLIS rearrangement is a genomic hallmark of hyalinizing trabecular tumors of the thyroid gland. Thyroid 2019, 29, 161–173. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong HG, Kondo T, Pham TQ, et al.: Prognostic significance of diffuse sclerosing variant papillary thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta- analysis. eur J Endocrinol 2017, 176, 433–441. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volante M, Collini P, Nikiforov YE, et al: Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma: the Turin proposal for the use of uniform diagnostic criteria and an algorithmic diagnostic approach. Am J Surg Pathol 2007, 31, 1256–1264. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito Y, Hirokawa M, Fukushima M, et al: Prevalence and prognostic significance of poor differentiation and tall cell variant in papillary carcinoma. World J Surg 2008, 32, 1535–1543. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzumaili B, Xu B, Spanheimer PM, et al.: Grading of medullary thyroid carcinoma on the basis of tumor necrosis and high mitotic rate is an independent. Mod Pathol 2020, 33, 1690–1701. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs TL, Nassour AJ, Glover A, et al.: A Proposed Grading Scheme for Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma Based on Proliferative Activity (Ki-67 and Mitotic. Am J Surg Pathol 2020, 44, 1419–1428. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kure S and Ohashi R. Thyroid Hurthle Cell Carcinoma: Clinical, Pathological, and Molecular Features.

- Ganly I, Makarov V, Deraje S, et al.: Integrated Genomic Analysis of Hürthle Cell Cancer Reveals Oncogenic Drivers, Recurrent Mitochondrial Mutations, and Unique Chromosomal Landscapes. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 256–270. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Morphology, genetic abnormalities, and intracellular signaling pathways of differentiated thyroid tumors. The three most important gross findings of thyroid tumors are (i) single or multiple nodules, (ii) capsule formation, and (iii) the presence or absence of invasive growth. A lesion with a single nodule and a thick fibrous capsule indicates a neoplastic lesion that has expansively grown over time. Multinodular lesions are more likely to be nonneoplastic. Lesions with irregular margins are suspected of infiltrative growth and may be malignant. The most important histological findings are the histological architecture (follicular, papillary, or solid) and papillary carcinoma (PTC)-like nuclear features (nuclear score: nuclear enlargement, glassy chromatin, and irregular nuclear shape [nuclear grooves and pseudoinclusions]), with one point given for each [Total 1-3 points]). Regarding genetic mutations, well-differentiated tumors such as thyroid follicular nodular disease (or functional nodules) show abnormalities in the TSHR to GNAS/cAMP/PKA pathway. Differentiated tumors can be classified into RAS-like tumors (RLTs) and BRAF p.V600E-like tumors (BLTs). Many of the driver gene mutations in differentiated thyroid cancer contribute to activating the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways downstream of tyrosine kinase receptors such as RET and NTRKs. RLTs activate the MAPK and PI3K pathways, and CRAF induces negative feedback to inhibit MAPK. As a result, the anti-apoptotic effect via the PI3K pathway is predominant in RLTs. BLTs activate the MAPK pathway, which is highly proliferative. In well-differentiated thyroid tumors such as thyroid follicular nodular disease (or functional nodule), activation of the TSH receptor-mediated cAMP pathway is predominant, which promotes hormonal functions, such as iodine metabolism and expression of hormone-related genes. *NIFTP: Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features, TT-UMP: Thyroid tumours of uncertain malignant potential, IEFVPTC: Invasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Figure 1.

Morphology, genetic abnormalities, and intracellular signaling pathways of differentiated thyroid tumors. The three most important gross findings of thyroid tumors are (i) single or multiple nodules, (ii) capsule formation, and (iii) the presence or absence of invasive growth. A lesion with a single nodule and a thick fibrous capsule indicates a neoplastic lesion that has expansively grown over time. Multinodular lesions are more likely to be nonneoplastic. Lesions with irregular margins are suspected of infiltrative growth and may be malignant. The most important histological findings are the histological architecture (follicular, papillary, or solid) and papillary carcinoma (PTC)-like nuclear features (nuclear score: nuclear enlargement, glassy chromatin, and irregular nuclear shape [nuclear grooves and pseudoinclusions]), with one point given for each [Total 1-3 points]). Regarding genetic mutations, well-differentiated tumors such as thyroid follicular nodular disease (or functional nodules) show abnormalities in the TSHR to GNAS/cAMP/PKA pathway. Differentiated tumors can be classified into RAS-like tumors (RLTs) and BRAF p.V600E-like tumors (BLTs). Many of the driver gene mutations in differentiated thyroid cancer contribute to activating the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways downstream of tyrosine kinase receptors such as RET and NTRKs. RLTs activate the MAPK and PI3K pathways, and CRAF induces negative feedback to inhibit MAPK. As a result, the anti-apoptotic effect via the PI3K pathway is predominant in RLTs. BLTs activate the MAPK pathway, which is highly proliferative. In well-differentiated thyroid tumors such as thyroid follicular nodular disease (or functional nodule), activation of the TSH receptor-mediated cAMP pathway is predominant, which promotes hormonal functions, such as iodine metabolism and expression of hormone-related genes. *NIFTP: Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features, TT-UMP: Thyroid tumours of uncertain malignant potential, IEFVPTC: Invasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Low-risk neoplasms of the thyroid. A-C: Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP). HE staining images of NIFTP at a low- (A) and a high-magnification (B). A papanicolaou staining image of NIFTP fine needle aspiration specimen (C). D-I: Hyalinizing trabecular tumor (HTT). HE staining images of HTT at a low- (A) and a high-magnification (B). A PAS staining image of HTT (F). Immunohistochemical staining with the MIB1 antibody revealed cytoplasmic (G) and cell membranous (H) immunoreactivity. A papanicolaou staining image of HTT fine needle aspiration specimen (I).

Figure 2.

Low-risk neoplasms of the thyroid. A-C: Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP). HE staining images of NIFTP at a low- (A) and a high-magnification (B). A papanicolaou staining image of NIFTP fine needle aspiration specimen (C). D-I: Hyalinizing trabecular tumor (HTT). HE staining images of HTT at a low- (A) and a high-magnification (B). A PAS staining image of HTT (F). Immunohistochemical staining with the MIB1 antibody revealed cytoplasmic (G) and cell membranous (H) immunoreactivity. A papanicolaou staining image of HTT fine needle aspiration specimen (I).

Figure 3.

Differentiated high-grade thyroid carcinoma (DHGTC). HE staining images of a DHGTC case (A-C). This case is a tall cell papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (A) which meets the criteria of DHGTC. It shows tumor necrosis (B) and mitosis (C). Immunohistochemistry of Thyroglobulin (D) and TTF1 (E). Ki-67 (MIB1) labeling index is about 15% (F).

Figure 3.

Differentiated high-grade thyroid carcinoma (DHGTC). HE staining images of a DHGTC case (A-C). This case is a tall cell papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (A) which meets the criteria of DHGTC. It shows tumor necrosis (B) and mitosis (C). Immunohistochemistry of Thyroglobulin (D) and TTF1 (E). Ki-67 (MIB1) labeling index is about 15% (F).

Figure 4.

Algorithm for diagnosis of thyroid tumors (WHO 5th edition). The WHO 5th simplified the diagnosis of thyroid cancer by dividing it into three steps. The first step is to consider the origin or cellular differentiation of the tumor cells, the second is to consider the gene mutations, and the third is to closely examine morphologic features such as capsular/vascular invasion, mitosis, and tumor necrosis. Cell-of-origin or cellular differentiation can be examined using immunohistological markers such as TTF1, PAX8, and calcitonin. The most frequent follicular cell-derived neoplasms are classified into five categories according to genetic mutations. Oncocytic tumors and RAS-like tumors (RLTs) are commonly encapsulated and are further classified morphologically by the presence or absence of capsular/vascular invasion. In RLTs, papillary-like nuclear features are also important. BRAF p.V600E-like tumors (BLTs) commonly show infiltrative growth with apparent PTC-like nuclear features and papillary structures. Tumors with predominantly solid growth are likely classified as high-grade carcinomas or anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC). Mitotic counts and tumor necrosis are critical in the diagnosis of high-grade carcinomas. *STI: solid/trabecular/insular, Q: questionable, FTA: follicular thyroid adenoma, FT-UMP: follicular tumor of uncertain malignant potential, FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma, NIFTP: Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features, WDT-UMP: well-differentiated tumour of uncertain malignant potential, IEFVPTC: invasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma, PDTC: poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma, DHGTC: differentiated high-grade thyroid carcinoma, ATC: anaplastic thyroid carcinoma.

Figure 4.

Algorithm for diagnosis of thyroid tumors (WHO 5th edition). The WHO 5th simplified the diagnosis of thyroid cancer by dividing it into three steps. The first step is to consider the origin or cellular differentiation of the tumor cells, the second is to consider the gene mutations, and the third is to closely examine morphologic features such as capsular/vascular invasion, mitosis, and tumor necrosis. Cell-of-origin or cellular differentiation can be examined using immunohistological markers such as TTF1, PAX8, and calcitonin. The most frequent follicular cell-derived neoplasms are classified into five categories according to genetic mutations. Oncocytic tumors and RAS-like tumors (RLTs) are commonly encapsulated and are further classified morphologically by the presence or absence of capsular/vascular invasion. In RLTs, papillary-like nuclear features are also important. BRAF p.V600E-like tumors (BLTs) commonly show infiltrative growth with apparent PTC-like nuclear features and papillary structures. Tumors with predominantly solid growth are likely classified as high-grade carcinomas or anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC). Mitotic counts and tumor necrosis are critical in the diagnosis of high-grade carcinomas. *STI: solid/trabecular/insular, Q: questionable, FTA: follicular thyroid adenoma, FT-UMP: follicular tumor of uncertain malignant potential, FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma, NIFTP: Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features, WDT-UMP: well-differentiated tumour of uncertain malignant potential, IEFVPTC: invasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma, PDTC: poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma, DHGTC: differentiated high-grade thyroid carcinoma, ATC: anaplastic thyroid carcinoma.

Table 1.

Summary of the WHO classification, 5th edition (beta, 2022).

Table 1.

Summary of the WHO classification, 5th edition (beta, 2022).

Table 2.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) subtypes (WHO 5th edition, 2022).

Table 2.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) subtypes (WHO 5th edition, 2022).

Table 3.

Diagnostic criteria for high‐grade follicular cell‐derived non‐anaplastic thyroid carcinomas

and high‐grade medullary carcinoma.

Table 3.

Diagnostic criteria for high‐grade follicular cell‐derived non‐anaplastic thyroid carcinomas

and high‐grade medullary carcinoma.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).