Submitted:

26 February 2024

Posted:

27 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Graduate Employability: Conceptual Framework and Measures Review

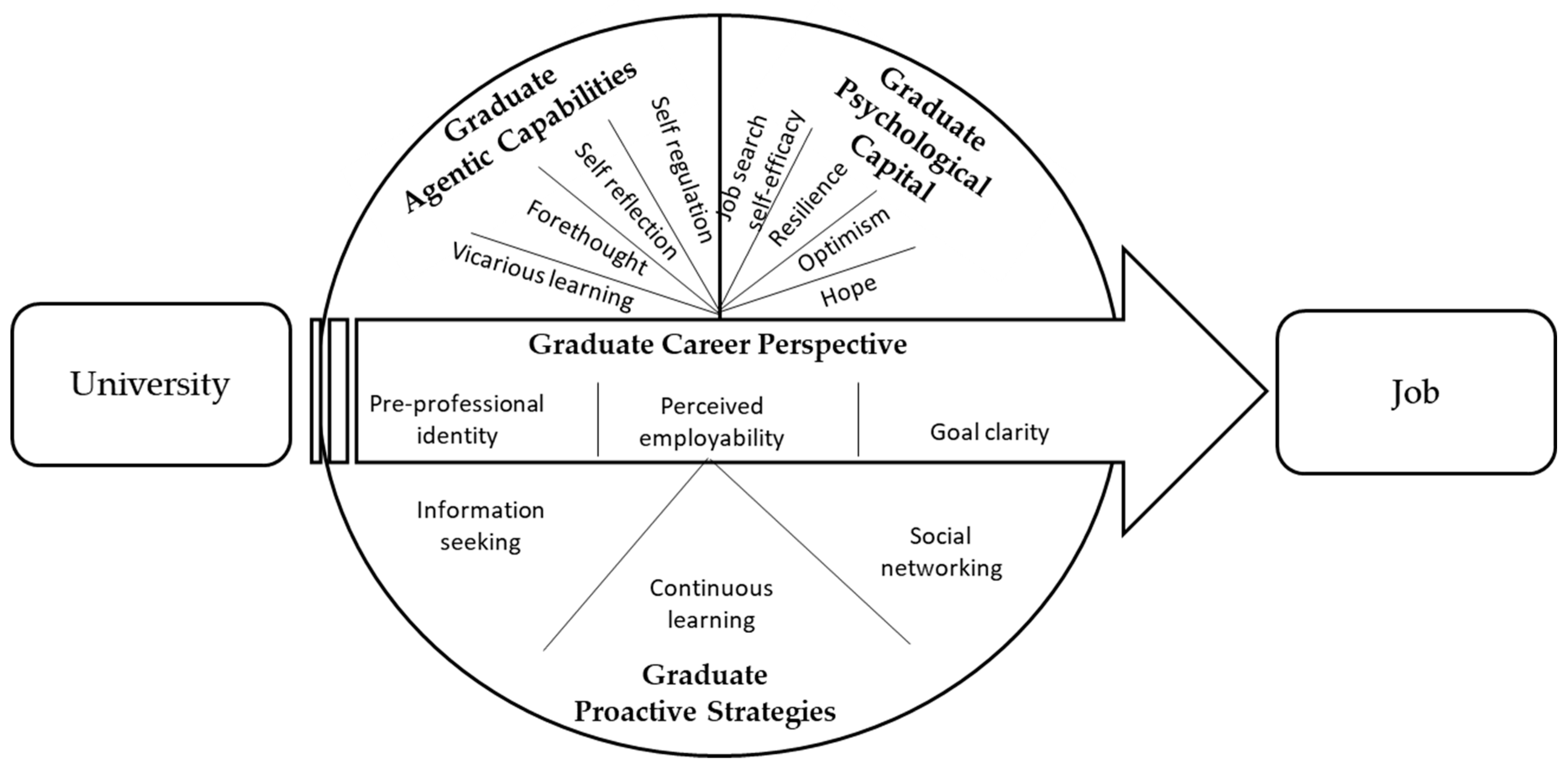

1.2. The Orientamentis Questionnaire. Theoretical Model

1.2.1. Graduate Agentic Capabilities

1.2.2. Graduate Psychological Capital

1.2.3. Graduate Career Perspective

1.2.4. Graduate Employability Behaviors

1.3. The Orientamentis Questionnaire: Tool Development

- -

- Agentic Capabilities: 13 items taken from the WAC questionnaire [31] adapted to graduates. Specifically, self-regulation was assessed with 3 items (e.g. I manage my moods in order to limit their negative influence on my goals), forethought with 4 items (e.g. I envision in advance the actions I will put in place to find work), vicarious learning with 3 items (e.g. In the job search I find very useful to see how others act and what results they get) and self-reflection with 3 items (e.g. I reflect on the feedback I receive, even those that are particularly critical, to better understand my performance).

- -

- Psychological Capital: 18 items were adapted from Luthans PsyCap questionnaire [29]. Specifically, 5 items were used to assess resilience (e.g. After a setback in study/work I immediately regain my good mood); 5 items to assess hope (e.g. “If I had trouble finding a job, I could think of different strategies to get it” and 3 items to assess optimism (e.g. I look to the future with hope and enthusiasm). Job search self-efficacy was measured using 5 items referred to the personal beliefs to successfully engage in job search behaviors and to receive favorable job search outcomes [150] (e.g. I am confident of my ability to be appreciated in a job interview).

- -

- Career perspective: 11 items were employed to assess this area distributed as follows: 4 items to assess perceived employability [114,151] (e.g. My skills are sought-after in the labor market); 3 items to measure goal clarity [116] (e.g. My professional goals are clear and well defined); 4 items for the pre-professional identity adapting an existing work identity scale [34] (e.g. I am highly committed to working in the field I studied for).

- -

- Proactive Strategies: 12 items were used to assess this area, derived comparing existing scales [37,124,143] with qualitative data collected in the preliminary interviews on effective self-initiated job search strategies and were distributed as follows: 4 items to assess social networking (e.g. I reach out to my contacts and friendships to increase my job opportunities); 4 items to measure continuous learning (e.g. I seek out learning opportunities (webinars, courses, events) related to my professional interests); 4 items to assess information seeking (e.g. I keep myself updated on professional opportunities in my local area related to my field).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analytical Strategy

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Factorial Structure of the Questionnaire Areas

- Graduate Agentic Capabilities Factor Structure.

- Graduate Psychological Capital Factor Structure

- Graduate Career Perspective Factor Structure

- Graduate Proactive Strategies Factor Structure

3.2. Cross-Sectional Correlations

3.3. Longitudinal Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Statistical Office. EUROSTAT. Population by educational attainment level, sex and age. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/edat_lfse_03$DV_598/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 25 January 23).

- Tomlinson, M. Graduate employability: A review of conceptual and empirical themes. High. Educ. Policy 2012, 25, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, L. Competing perspectives on graduate employability: Possession, position or process? Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Statistical Office. EUROSTAT. Employment rates of young people not in education and training by sex, educational attainment level and years since completion of highest level of education. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/EDAT_LFSE_24__custom_9932846/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. CEDEFOP. Over-qualification rate (of tertiary graduates). Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/skills-intelligence/over-qualification-rate-tertiary-graduates?country=EU&year=2021#1 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Santos, G.G. Career Boundaries and Employability Perceptions: An Exploratory Study with Graduates. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.E. Role models in career development: New directions for theory and research. J. Vocat. Behav 2004, 65, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverke, M.; Hellgren, J.; Naswall, K. No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, L.M. Becoming a graduate: The warranting of an emergent identity. Educ. Train. 2015, 57, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijde, C.M.; van der Heijden, B.I.J.M. A competence-based and multidimensional operationalization and measurement of employability. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2006, 45, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y.; Rousseau, D.M. Integrating psychological contracts and ecosystems in career studies and management. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 13, 84–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Lent, R.W. Vocational psychology: Agency, equity, and well-being, Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrier, A.; De cuyper, N.; Akkermans, J. The winner takes it all, the loser has to fall: Provoking the agency perspective in employability research. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2018, 28, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J.; Ashforth, B.E. Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. J. Vocat. Behav 2004, 65, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A.; Verbruggen, M.; De Cuyper, N. Integrating different notions of employability in a dynamic chain: The relationship between job transitions, movement capital and perceived employability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholen, G. What can research into graduate employability tell us about agency and structure? Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2015, 36, 766–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, G.W.; Jolly, A. Graduate identity and employability. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 37, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, L. Competing perspectives on graduate employability: possession, position or process? Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, A.; Pluviano, S. Looking for a route in turbulent waters: Employability as a compass for career success. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 6, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M.; McCafferty, H.; Port, A.; Maguire, N.; Zabelski, A.E.; Burnaru, A.; Charles, M.; Kirby, S. Developing graduate employability for a challenging labour market: the validation of the graduate capital scale. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2022, 14, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, A.; Arnold, J. Self-perceived employability: Development and validation of a scale. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A.; Sels, L.; Stynen, D. Career mobility at the intersection between agent and structure: A conceptual model. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 739–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. Re-conceptualising graduate employability: the importance of pre-professional identity, High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. Graduate employability and student attitudes and orientations to the labour market, J. Educ. Work. 2007, 20, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Miller, D. Called to account: the CV as an autobiographical practice. Sociology 1993, 27, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.; Bimrose, J.; Barnes, S.A.; Hughes, D. The role of career adaptabilities for mid-career changers, J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the human competitive edge, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cenciotti, R.; Borgogni, L.; Callea, A.; Colombo, L.; Cortese, C.G.; Ingusci, E.; Miraglia, M.; Zito, M. The Italian version of the Job Crafting Scale (JCS). App. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 277, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cenciotti, R.; Borgogni, L.; Consiglio, C.; Fedeli, E.; Alessandri, G. The work agentic capabilities (WAC) questionnaire: Validation of a new measure. Rev. Psicol. Trab y de las Organ. 2020, 36, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, K. Antecedents and consequences of employability orientation. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 13, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, A.; Ingusci, E.; Magrin, M.E.; Manuti, A.; Scrima, F. Employability as a compass for career success: Development and initial validation of a new multidimensional measure. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2019, 23, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J. A dispositional approach to employability: Development of a measure and test of implications for employee reactions to organizational change. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. A review of empirical studies on employability and measures of employability. In Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience, 1st ed.; Maree, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, E.; Nelissen, J.; De Cuyper, N.; Forrier, A.; Verbruggen, M.; De Witte, H. Employability capital: A conceptual framework tested through expert analysis. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, A.; Herbert, I.; Rothwell, F. Self-perceived employability: Construction and initial validation of a scale for university students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, W.; Creed, P.A.; Glendon, A.I. Development and initial validation of a perceived future employability scale for young adults. J. Career Assess. 2019, 27, 610–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.; Ananthram, S. Development, validation and deployment of the EmployABILITY scale. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 1311–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala Calvo, J.C.; Manzano García, G. The influence of psychological capital on graduates’ perception of employability: The mediating role of employability skills. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of personality. In Handbook of personality, 2nd ed.; Pervin, L., John, O.P., Eds.; Guilford Publications: New York, USA, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents, 1st ed.; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, Connecticut, 2006; Volume 5, pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Toward an agentic theory of the self. Adv. Study Behav. 2008, 3, 15–49. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C.; Stark, P. Readiness for self-directed change in professional behaviours: Factorial validation of the Self-reflection and Insight Scale. Med. Educ. 2008, 42, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and wellbeing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindl, U.K.; Parker, S.K.; Totterdell, P.; Hagger-Johnson, G. Fuel of the self-starter: How mood relates to proactive goal regulation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code, J. Agency for learning: Intention, motivation, self-efficacy and self-regulation. Front. Genet. 2020, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henscheid, J.M. Institutional efforts to move seniors through and beyond college. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2008, 144, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social foundations of thoughts and actions: a social cognitive theory. In The Health Psychology Reader, 1st ed.; Marks, D., Ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, California, 1986; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Behavioral management and task performance in organizations: conceptual background, meta-analysis, and test of alternative models. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 155–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooft, E.A.; Wanberg, C.R.; Van Hoye, G. Moving beyond job search quantity: Towards a conceptualization and self-regulatory framework of job search quality. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 3, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kantrowitz, T.M. Job search and employment: A personality motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Stevens, C.K.; Lee, F.K. Effects of conscientiousness and extraversion on new labor market entrants’ job search: The mediating role of metacognitive activities and positive emotions. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Lee, F.K.; Veiga, S.P. D. M.; Haggard, D.L.; Wu, S.Y. Be happy, don't wait: The role of trait affect in job search. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 483–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfenbein, H.A. Emotion in organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2007, 1, 315–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacre Pool, L.; Qualter, P. Emotional self-efficacy, graduate employability, and career satisfaction: Testing the associations. Aust. J. Psychol. 2013, 65, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, D.M.; Gibson, C.B.; Porath, C. Act expediently, with autonomy: Vicarious learning, empowered behaviors, and performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 32, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Shin, H.S. Effects of self-reflection-focused career course on career search efficacy, career maturity, and career adaptability in nursing students: A mixed methods study. J. Prof. Nurs. 2020, 36, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S. Effects of discipline-based career course on nursing students’ career search self-efficacy, career preparation behavior, and perceptions of career barriers. Asian Nurs. Res. 2015, 9, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L. A bridge to success: A nursing student success strategies improvement course. J. Nurs. Educ. 2016, 55, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manz, C.C.; Sims Jr, H.P. Vicarious learning: The influence of modeling on organizational behavior. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1981, 6, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, C.G. Coactive vicarious learning: Toward a relational theory of vicarious learning in organizations. Acade. Manage. Rev. 2018, 43, 610–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraut, M. Learning from other people in the workplace. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2007, 33, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Planta, A.; Bianco, P. The role of agentic capacities in turnover intentions among nurses. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2018, 40, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cenciotti, R.; Alessandri, G.; Borgogni, L.; Consiglio, C. Agentic capabilities as predictors of psychological capital, job performance, and social capital over time. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2022, 30, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S.; Almeida, L.; Garcia-Aracil, A. It's a very different world: work transition and employability of higher education graduates. High. Edu. Ski. Work-based Learn. 2021, 11, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. The additive value of positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors. J. Manage. 2010, 36, 430–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, Social, and Now Positive Psychological Capital Management: Investing in People for Competitive Advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Reichard, R.J.; Luthans, F.; Mhatre, K.H. Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological capital and beyond, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, R.; Liu, Y. The impact of structural empowerment and psychological capital on competence among Chinese baccalaureate nursing students: A questionnaire survey. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 36, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allvin, M. The individualization of labour. In Learning to be Employable: New agendas on work, responsibility and learning in a globalized world, 1st ed.; Garsten, A., Jacobsson, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan London: New York, USA, 2004; pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, H. Job insecurity: Review of the international literature on definitions, prevalence, antecedents and consequences. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2005, 31, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Jackson, D. The need to develop graduate employability for a globalised world. In Developing and utilizing employability capitals: Graduates’ strategies across labour markets, 1st ed.; Nghia, T.L.H., Pham, T., Tomlinson, M., Medica, K., Thompson, C.D., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yorke, M.; Knight, P. Learning, Curriculum and Employability in Higher Education, 1st ed.; Routledge Falmer: New York, USA, 2004; pp. 85–154. [Google Scholar]

- Vuolo, M.; Mortimer, J.T.; Staff, J. Adolescent precursors of pathways from school to work. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiou, K.; Nikolaou, I. The influence and development of psychological capital in the job search context. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2019, 19, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle, M.A.; Antwi, C.O.; Ntim, S.Y.; Affum-Osei, E.; Ren, J. Am I gonna get a job? Graduating students’ psychological capital, coping styles, and employment anxiety. J Career Dev. 2022, 49, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.M.; Meneghel, I.; Carmona-Halty, M.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Adaptation and validation to Spanish of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire–12 (PCQ–12) in academic contexts. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3409–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R.; Hulin, C.L. Individual differences in successful job searches following lay-off. Pers. Psychol. 1985, 38, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesdale, D.; Pinter, K. Self-efficacy and job-seeking activities in unemployed ethnic youth. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 140, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, L.M.; Roehling, M.V.; LePine, M.A.; Boswell, W.R. A longitudinal study of the relationships among job search self-efficacy, job interviews, and employment outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2003, 18, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, M.; Liao, H.; Shi, J. Self-regulation during job search: The opposing effects of employment self-efficacy and job search behavior self-efficacy. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bul. 1998, 124, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kantrowitz, T.M. Job search and employment: A personality motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saks, A.M. Multiple predictors and criteria of job search success. J. Vocat. Behav., 2006, 68, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, I.; Jacquet, F.; Leroy, N. Self-efficacy, goals, and job search behaviors. Carrer Dev. Int., 2011, 16, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquijo, I.; Extremera, N.; Solabarrieta, J. Connecting Emotion Regulation to Career Outcomes: Do Proactivity and Job Search Self-Efficacy Mediate This Link? Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 1109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, M. Relationships between career motivation, empowerment and support for career development, J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1993, 66, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koen, J.; Klehe, U.C.; Van Vianen, A. Training career adaptability to facilitate a successful school-to-work transition, J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhercke, D.; De Cuyper, N.; Peeters, E.; De Witte, H. Defining perceived employability: a psychological approach. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Hough, L.M.; Song, Z. Predictive validity of a multidisciplinary model of reemployment success. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1100–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, V.; Hernandez, E. The influence of ethnic identity on self-authorship: a longitudinal study of Latino/a college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2007, 48, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, D. Peer observation as a transformatory tool? Teach. High. Edu. 2005, 10, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2004; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Anakwe, U.P.; Hall, J.C.; Schor, S.M. Knowledge-related skills and effective career management. Int. J. Manpow., 2000, 21, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellenz, M. Forming the professional self: Building and the ontological perspective on professional education and development. Educ. Philos. Theory 2016, 48, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, L.; Fehr, L.; Blank, N.; Connell, H.; Georganas, D.; Fernandez, D.; Peterson, V. Lessons learned from experiential learning: What do students learn from a practicum/internship? Int. J. Learn. High. Educ. 2012, 24, 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, S.; Somerville, M. Transformations at work: identity and learning. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2004, 26, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrom, S. The dynamics of professional identity formation: graduates’ transitions from higher education to working life. Vocat. Learn. 2009, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. Developing pre-professional identity in undergraduates through work-integrated learning. High. Educ. 2017, 74, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, S.; Waters, L.; Briscoe, J.P.; Hall, D.T. T. Employability during unemployment: Adaptability, career identity and human and social capital. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, J.; Zhang, T.C.; Li, Q.M. Effects of professional identity on turnover intention in China's hotel employees: The mediating role of employee engagement and job satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khapova, S.; Arthur, M.; Wilderom, C.; Svensson, J. Professional identity as the key to career change intention. Career Dev. Int. 2007, 12, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.; Roziner, I.; Savaya, R. Professional identity, perceived job performance and sense of personal accomplishment among social workers in Israel: The overriding significance of the working alliance. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, M. Rethinking graduate employability: The role of capital, individual attributes and context. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1923–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cron, W.L.; Slocum Jr, J.W. The influence of career stages on salespeople’s job attitudes, work perceptions, and performance. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.J.; Lim, V.K. Strength in adversity: The influence of psychological capital on job search. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 811–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Battisti, F.; Gilardi, S.; Guglielmetti, C.; Siletti, E. Perceived employability and reemployment: Do job search strategies and psychological distress matter? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 813–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, S.; Bakker, R.H.; Schellekens, J.M.H. Predictors for re-employment success in newly unemployed: A prospective cohort study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, L.D.; Qualter, P. Emotional self-efficacy, graduate employability, and career satisfaction: Testing the associations. Aust. J. Psychol. 2013, 65, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, R.; Fazi, L.; Guglielmi, D.; Mariani, M.G. Enhancing sustainability: Psychological capital, perceived employability, and job insecurity in different work contract conditions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio, C.; Menatta, P.; Borgogni, L.; Alessandri, G.; Valente, L.; Caprara, G.V. How youth may find jobs: the role of positivity, perceived employability, and support from employment agencies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, M. Toward a theory of career motivation. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1983, 8, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladany, N.; Melincoff, D.S.; Constantine, M.G.; Love, R. At-risk urban high school students’ commitment to career choices. J. Couns. Dev. 1997, 76, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coté, S.; Saks, A.A.; Zizic, J. Trait affect and job search outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Callanan, G.A.; Kaplan, E. The role of goal setting in career management. Int. J. Career Manag. 1995, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikic, J.; Saks A., M. Job search and social cognitive theory: The role of career-relevant activities. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymon, A. The Student Perspective on Employability. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 841–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, J.S.; Schoon, I. Career success: The role of teenage career aspirations, ambition value and gender in predicting adult social status and earnings. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Niles, S.G.; Akos, P. Engagement in adolescent career preparation: Social support, personality and the development of choice decidedness and congruence. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M. The importance of career clarity and proactive career behaviours in predicting positive student outcomes: Evidence across two cohorts of secondary students in Singapore. Asia Pacific J. Educ. 2017, 37, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Janasz S., C.; Forret, M.L. Learning the art of Networking: A Critical Skill for Enhancing Social Capital and Career Success. J. Manage. 2008, 32, 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Koen, J.; Zizic, J. Job search and social cognitive theory: The role of career-relevant activities. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf S., A.; Colarelli S., M.; Hartman, K. Development of the Career Exploration Survey (CES). J. Vocat. Behav. 1983, 22, 191–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikic, J.; Klehe, U.C. Job loss as a blessing in disguise: The role of career exploration and career planning in predicting reemployment quality J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, G. Testing a two-dimension measure of job search behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1994, 59, 288–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Newman, A.; Le, H.; Presbitero, A.; Zheng, C. Career exploration: A review and future research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.; Arnold, J. The impact of career exploration on career development among Hong Kong Chinese university students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2014, 55, 732–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Ireland, G.W.; Penn, L.T.; Morris, T.R.; Sappington, R. Sources of self-efficacy and outcome expectations for career exploration and decision-making: A test of the social cognitive model of career self-management. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 99, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffy, B.D.; Shaw, K.L.; Noe, A.W. Antecedants and consequences of job search behaviors. J. Vocat. Behav. 1989, 35, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, S.A.; Austin, E.J.; Hartman, K. The impact of career exploration and interview readiness on interview performance and outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 1984, 24, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callanan, G.A.; Greenhaus, J.H. The career indecision of managers and professionals: An examination of multiple subtypes. J. Vocat. Behav. 1992, 41, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, L.; Tziner, A.; Vered, E. Predictors of job search intensity among college graduates. J. Career Assess. 2004, 12, 322–344. [Google Scholar]

- Okay-Somerville, B.; D. Scholarios. Position, Possession or Process? Understanding Objective and Subjective Employability During University-to-Work Transitions. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, M.D.L.; Polzer, J.T.; Stewart, K.J. Friends in high places: the effects of social networks on in salary discrimination negotiations, Adm. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Kanfer, R.; Banas, J.T. Predictors and outcomes of networking intensity among unemployed job seekers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, T.A.; Eby, L.T.; Reeves, M.P. Predictors of networking intensity and network quality among white-collar job seekers. J. Career Dev. 2006, 32, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoye, G.; Van Hooft, E.A.; Lievens, F. Networking as a job search behaviour: A social network perspective. J. Occup. Psychol. 2009, 82, 661–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; van Hooft, E.A.; Liu, S.; Csillag, B. Can job seekers achieve more through networking? The role of networking intensity, self-efficacy, and proximal benefits. Pers. Psychol. 2020, 73, 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A.G. Career guidance and public policy. In Rethinking careers education and guidance: Theory, policy and practice, 1st ed.; Hawthorn, R., Kidd, J.M., Killeen, J., Law, B., Watts, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1999; pp. 380–391. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgstock, R. The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2009, 28, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlveen, P.; Brooks, S.; Lichtenberg, A.; Smith, M.; Torjul, P.; Tyler, J. Career development learning frameworks for work-integrated learning. In Developing Learning Professionals, 1st ed.; Billett, S., Henderson, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, NL, 2011; pp. 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D.; Bosley, S.; Bowes, L.; Bysshe, S. The economic benefits of guidance; Centre for Guidance Studies: University of Derby: Derby, UK, 2002; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarathi, R.; Kulkarni, S. Understanding personal branding perceptions through intentions. BVIMSR’s J. Manag. Rese. 2018, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A.M.; Ashforth, B.B. Change in job search behaviors and employment outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 56, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, C.D.; Highhouse, S. Relation of job search and choice process with subsequent satisfaction. J. Econ. Psychol. 2005, 26, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koen, J.; Klehe, U.C.; Van Vianen, A.E.; Zikic, J.; Nauta, A. Job-search strategies and reemployment quality: The impact of career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Zikic, J.; Koen, J. Job search self-efficacy: Reconceptualizing the construct and its measurement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 86, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernston, E.; Marklund, S. The relationship between employability and subsequent health. Work Stress 2008, 21, 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flora, D.B. Your coefficient alpha is probably wrong, but which coefficient omega is right? A tutorial on using R to obtain better reliability estimates. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 3, 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthen & Muthen: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998-2018. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P.M. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika 2001, 66, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasingam, S.; Fujiwara, Y.; Thurasamy, R. ‘I am competent so I can be choosy’: choosiness and its implication on graduate employability. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Order Dimensions and Items | First Order Factors | |||

| Mean | SD | λ | rtt | |

| Self-regulation (α = .51; ω = .52) | ||||

| Item 1 | 4.84 | 1.44 | 0.508 | 0.359 |

| Item 2 | 4.82 | 1.36 | 0.609 | 0.335 |

| Item 3 | 4.19 | 1.52 | 0.417 | 0.293 |

| Self-reflection (α = .63; ω = .64) | ||||

| Item 4 | 5.85 | 0.97 | 0.598 | 0.419 |

| Item 5 | 5.41 | 1.14 | 0.581 | 0.404 |

| Item 6 | 5.91 | 0.93 | 0.642 | 0.493 |

| Vicarious learning (α = .70; ω = .71) | ||||

| Item 7 | 4.90 | 1.30 | 0.764 | 0.590 |

| Item 8 | 4.93 | 1.27 | 0.698 | 0.534 |

| Item 9 | 5.48 | 1.24 | 0.545 | 0.432 |

| Forethought (α = .70; ω = .70) | ||||

| Item 10 | 4.86 | 1.26 | 0.592 | 0.496 |

| Item 11 | 5.30 | 1.16 | 0.571 | 0.472 |

| Item 12 | 5.06 | 1.17 | 0.579 | 0.442 |

| Item 13 | 5.44 | 1.29 | 0.657 | 0.497 |

| Second Order Dimension | Second Order Factors (ω = .71) | |||

| Self-regulation | 4.62 | 1.03 | 0.441 | - |

| Self-reflection | 5.72 | 0.77 | 0.947 | - |

| Vicarious learning | 5.10 | 1.00 | 0.420 | - |

| Forethought | 5.17 | 0.88 | 0.773 | - |

| First Order Dimensions and Items | First Order Factors | |||

| Mean | SD | λ | rtt | |

| Job Search Self-Efficacy (α = .80; ω = .80) | ||||

| Item 1 | 4.82 | 1.33 | 0.665 | 0.592 |

| Item 2 | 5.04 | 1.21 | 0.663 | 0.579 |

| Item 3 | 5.02 | 1.38 | 0.653 | 0.576 |

| Item 4 | 5.03 | 1.35 | 0.695 | 0.592 |

| Item 5 | 5.28 | 1.24 | 0.637 | 0.547 |

| Resilience (α = .77; ω = .77) | ||||

| Item 6 | 4.77 | 1.35 | 0.524 | 0.442 |

| Item 7 | 4.24 | 1.37 | 0.714 | 0.619 |

| Item 8 | 3.86 | 1.47 | 0.605 | 0.518 |

| Item 9 | 5.03 | 1.33 | 0.645 | 0.557 |

| Item 10 | 4.18 | 1.38 | 0.697 | 0.582 |

| Hope (α = .68; ω = .68) | ||||

| Item 11 | 5.03 | 1.28 | 0.534 | 0.488 |

| Item 12 | 5.57 | 1.17 | 0.665 | 0.450 |

| Item 13 | 4.46 | 1.39 | 0.621 | 0.492 |

| Item 14 | 5.43 | 1.11 | 0.506 | 0.421 |

| Optimism (α = .86; ω = .87) | ||||

| Item 15 | 4.23 | 1.56 | 0.910 | 0.790 |

| Item 16 | 4.67 | 1.56 | 0.881 | 0.768 |

| Item 17 | 4.46 | 1.75 | 0.677 | 0.638 |

| Second Order Dimensions | Second Order Factors (ω = .85) | |||

| Job Search Self-Efficacy | 5.04 | 0.97 | 0.778 | - |

| Resilience | 4.47 | 1.00 | 0.824 | - |

| Hope | 5.12 | 0.8 | 0.937 | - |

| Optimism | 4.15 | 1.43 | 0.738 | - |

| First Order Dimensions and Items | First Order Factors | |||

| Mean | SD | λ | rtt | |

| Goal clarity (α = .83; ω = .84) | ||||

| Item 1 | 4.51 | 1.93 | 0.774 | 0.679 |

| Item 2 | 4.59 | 1.71 | 0.944 | 0.783 |

| Item 3 | 4.54 | 1.83 | 0.657 | 0.596 |

| Perceived employability (α = .58; ω = .60) | ||||

| Item 4 | 3.42 | 1.55 | 0.417 | 0.308 |

| Item 5 | 5.11 | 1.34 | 0.582 | 0.394 |

| Item 6 | 4.69 | 1.25 | 0.599 | 0.430 |

| Item 7 | 4.16 | 1.75 | 0.469 | 0.339 |

| Pre-professional identity (α= .88;ω= .89) | ||||

| Item 8 | 5.92 | 1.26 | 0.904 | 0.820 |

| Item 9 | 5.46 | 1.36 | 0.731 | 0.675 |

| Item 10 | 5.75 | 1.24 | 0.790 | 0.743 |

| Item 11 | 6.06 | 1.23 | 0.816 | 0.743 |

| Second Order Dimensions | Second Order Factors (ω = .78) | |||

| Goal clarity | 4.55 | 1.57 | 0.705 | - |

| Perceived employability | 4.34 | 0.99 | 0.547 | - |

| Pre-professional identity | 5.80 | 1.09 | 0.646 | - |

| First Order Dimensions and Items | First Order Factors | |||

| Mean | SD | λ | rtt | |

| Social networking (α = .75; ω = .75) | ||||

| Item 1 | 3.30 | 1.79 | 0.646 | 0.556 |

| Item 2 | 4.44 | 1.64 | 0.774 | 0.615 |

| Item 3 | 3.93 | 1.68 | 0.697 | 0.572 |

| Item 4 | 2.41 | 1.68 | 0.508 | 0.419 |

| Continuous learning (α = .82; ω = .83) | ||||

| Item 5 | 4.75 | 1.58 | 0.794 | 0.710 |

| Item 6 | 5.33 | 1.33 | 0.642 | 0.557 |

| Item 7 | 4.38 | 1.73 | 0.809 | 0.716 |

| Item 8 | 3.65 | 1.77 | 0.702 | 0.607 |

| Information seeking (α = .75; ω = .76) | ||||

| Item 9 | 4.96 | 1.53 | 0.672 | 0.550 |

| Item 10 | 4.28 | 1.65 | 0.685 | 0.535 |

| Item 11 | 4.37 | 1.67 | 0.765 | 0.656 |

| Item 12 | 3.30 | 1.94 | 0.540 | 0.468 |

| Second Order Dimensions | Second Order Factors (ω = .81) | |||

| Social networking | 3.52 | 1.28 | 0.748 | - |

| Continuous learning | 4.53 | 1.30 | 0.678 | - |

| Information seeking | 4.23 | 1.29 | 0.699 | - |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| Graduate Agentic Capabilities | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Self-regulation | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Self-reflection | .24** | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Vicarious learning | -.01 | .32** | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Forethought | .22** | .48** | .26** | ||||||||||||||||

| Graduate PsyCap | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Job search self-eff | .36** | .30** | .09** | .44** | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Resilience | .56** | .30** | .01 | .30** | .52** | ||||||||||||||

| 7. Hope | .37** | .40** | .18** | .49** | .55** | .52** | |||||||||||||

| 8. Optimism | .31** | .18** | .08** | .28** | .45** | .53** | .51** | ||||||||||||

| Graduate Career Perspective | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Goal clarity | .19** | .18** | .01 | .41** | .39** | .27** | .31** | .30** | |||||||||||

| 10. Perceived empl. | .19** | .20** | .17** | .31** | .47** | .30** | .47** | .44** | .27** | ||||||||||

| 11. Pre-prof. identity | .12** | .19** | .12** | .27** | .36** | .19** | .27** | .20** | .41** | .27** | |||||||||

| Graduate Proactive strategies | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Social networking | .04 | .15** | .22** | .31** | .33** | .14** | .29** | .12** | .21** | .36** | .16** | ||||||||

| 13. Continuous learning | .17** | .26** | .17** | .38** | .30** | .20** | .33** | .18** | .27** | .25** | .23** | .45** | |||||||

| 14. Information seeking | .13** | .21** | .15** | .28** | .29** | .17** | .26** | .05 | .12** | .13** | .12** | .42** | .39** | ||||||

| Second Order Factors | |||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Graduate Agentic Cap | .58** | .73** | .61** | .72** | .29** | .33** | .26** | .27** | .36** | .29** | .45** | .45** | .54** | .33** | |||||

| 16. Graduate PsyCap | .49** | .35** | .11** | .46** | .40** | .53** | .31** | .26** | .31** | .22** | .76** | .80** | .78** | .83** | .54** | ||||

| 17. Graduate Career Perspective | .23** | .25** | .11** | .45** | .84** | .62** | .73** | .31** | .34** | .16** | .54** | .34** | .46** | .42** | .39** | .55** | |||

| 18. Graduate Proactive strategies | .14** | .27** | .23** | .41** | .26** | .32** | .21** | .79** | .79** | .77** | .39** | .22** | .37** | .15** | .39** | .35** | .33** | ||

| Covariates | |||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Age | .04 | .03 | -.09** | -.06* | .09** | .05 | .05 | .04 | .07* | -.04 | -.05 | .02 | .00 | .01 | -.03 | .02 | .01 | .02 | |

| 20. Sex | .13** | -.07** | -.00 | -.05 | .11** | .12** | .04 | .09** | .02 | .09** | -.02 | -.02 | -.13** | -.11** | .01 | -.13** | .03 | -.11** | .05 |

| Variable | Perceived Employability (Rothwell et al., 2008) | Employment status | Professional coherence | Job Satisfaction |

| Graduate Agentic Capabilities | ||||

| Self-regulation | .21*** | .01 | -.05 | .03 |

| Self-reflection | -.01 | .08 | .08 | .15* |

| Vicarious learning | -.02 | .08 | .18** | .22** |

| Forethought | .13* | .13* | .10 | .13* |

| Graduate Psychological Capital | ||||

| Job search self-efficacy | .45*** | .17** | .22** | .25** |

| Resilience | .32*** | .06 | .04 | .12 |

| Hope | .43*** | .17** | .09 | .15* |

| Optimism | .48*** | .21** | .14* | .21** |

| Graduate Career perspective | ||||

| Goal clarity | .16** | .13* | .22** | .21** |

| Perceived employability | .63*** | .20** | .24*** | .18** |

| Pre-professional identity | .20** | .12* | .42*** | .15* |

| Graduate Proactive strategies | ||||

| Social networking | .04 | .05 | .19** | .13 |

| Continuous learning | .08 | .06 | .15* | .20** |

| Information seeking | .13* | .00 | -.18* | -.01 |

| Second Order Factors | ||||

| Graduate Agentic capabilities | .08 | .11 | .13 | .21** |

| Graduate Psychological Capital | .51*** | .20** | .15* | .23** |

| Graduate Career Perspective | .47*** | .20** | .38*** | .25** |

| Graduate Proactive strategies | .10 | .05 | .07 | .14* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).