Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

23 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

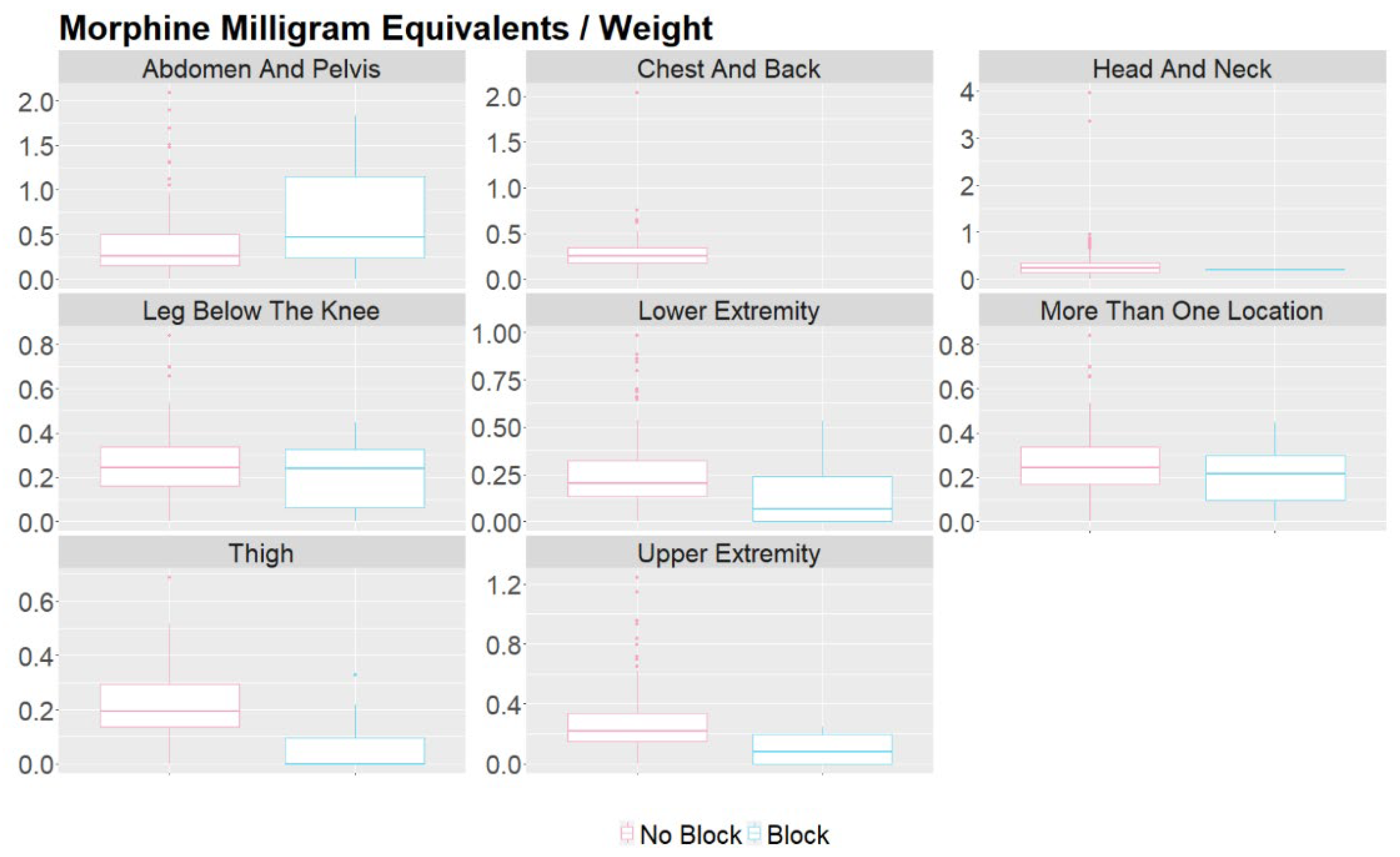

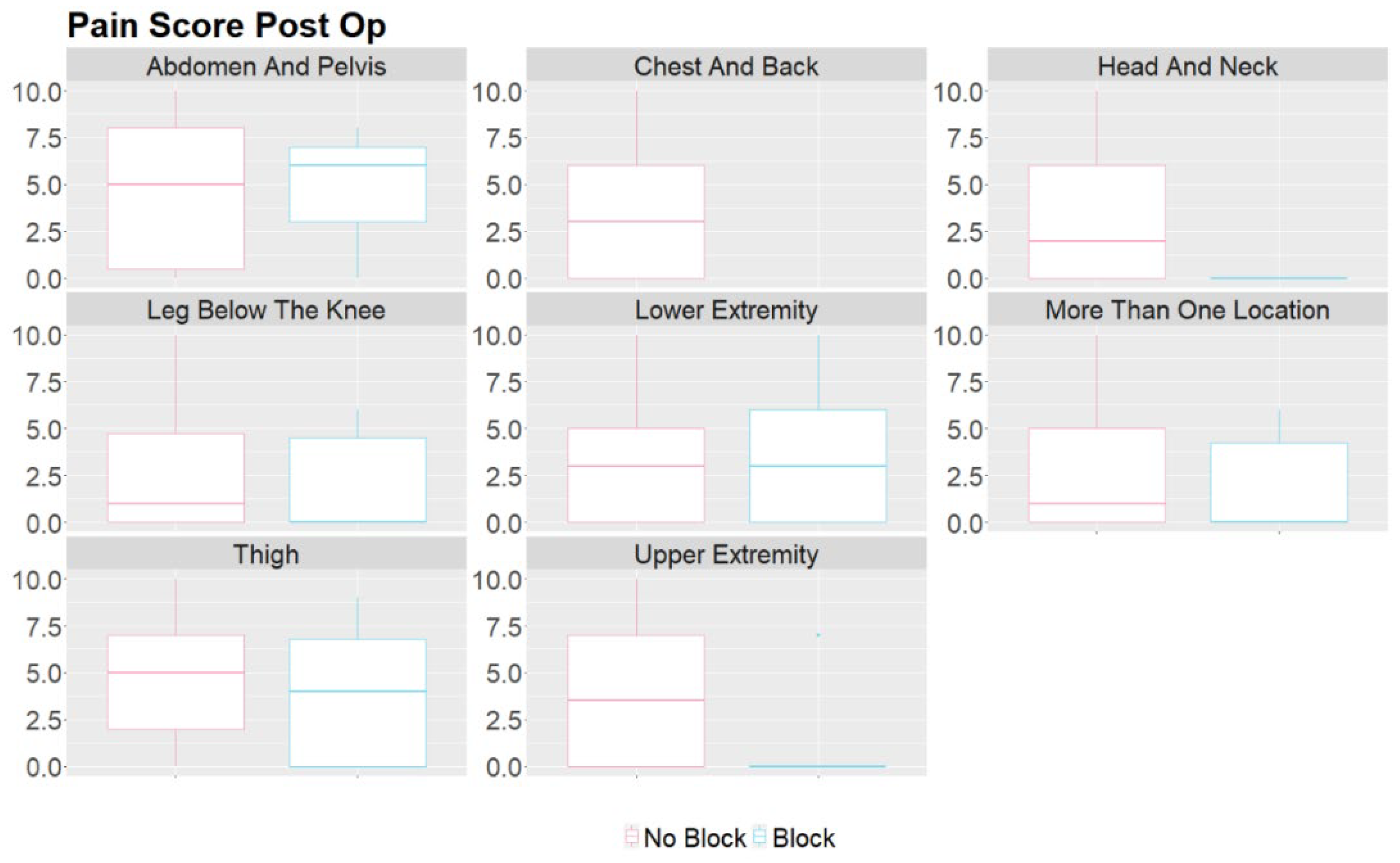

- They can effectively relieve pain during and after vascular malformation therapy and decrease the opioids required during general anesthesia and in the immediate postoperative period. By targeting specific nerves or nerve plexuses responsible for pain perception in the affected area, peripheral nerve blocks can reduce the need for systemic pain medications, which may have side effects and potential complications, such as respiratory depression, constipation, nausea, itching, and altered mental status following surgery. [9,10]. This study showed reduced MME/kg usage and pain scores in the block group, indicating that performing nerve blocks benefits selected patients. This finding is consistent with using peripheral nerve blocks in other surgeries [11,12,13].

- Minimizing pain and discomfort can improve the child's and parents' overall experience and reduce anxiety. Almost all patients and parents who completed the satisfaction questionnaires (26) were very satisfied with the postoperative pain control provided (8-10 on a 10-point scale). Only one patient rated their satisfaction with the pain control as a 7. Many of these patients returned for repeated sclerotherapy and received another block for postoperative pain control.

- Reducing the use of opioids and general anesthesia can lead to faster recovery times and shorter hospital stays for pediatric patients. This can particularly benefit outpatient procedures, such as vascular malformation therapies. In our study, there was no difference in the length of stay between the two groups, indicating that the nerve blocks did not facilitate a faster discharge at home despite better pain control in the block group. It is essential to mention that there were no complications from the nerve blocks, and most patients could go home the same day as the procedure. However, some patients who experienced severe pain when a previous procedure was done with no nerve block were very anxious to be discharged and stay overnight on the day of surgery. In addition, in many cases, Enoxaparin therapy was initiated on the procedure's day and required hospitalization.

- When performing peripheral nerve blocks in pediatric patients undergoing embolization or vascular therapy, it is essential to consider the child's location and size of the vascular malformation. Vascular malformations are frequently seen in children, with the most common area being in the head and neck [14]. Our retrospective study had similar results, with 39.6% of the vascular malformations treated in the study in the head and neck region. Most head and neck malformations are not amenable to a peripheral nerve block due to the location of the sensory nerves in the face and neck. The upper and lower extremities were the second and third most common sites for therapy, aligning with the most common areas of malformations. These locations are much more amenable to peripheral nerve blocks as nerve blocks have proven safe and effective in treating pain in the extremities. Careful consideration must be taken when determining if a patient should receive a peripheral nerve block for therapy. In this study, the proceduralist requested a peripheral nerve block for patients based on the location of the malformation and the likelihood of the treatment causing severe pain. Some of the nerve blocks performed were done for patients who had previously received therapy without nerve blocks but developed severe pain in the postoperative setting.

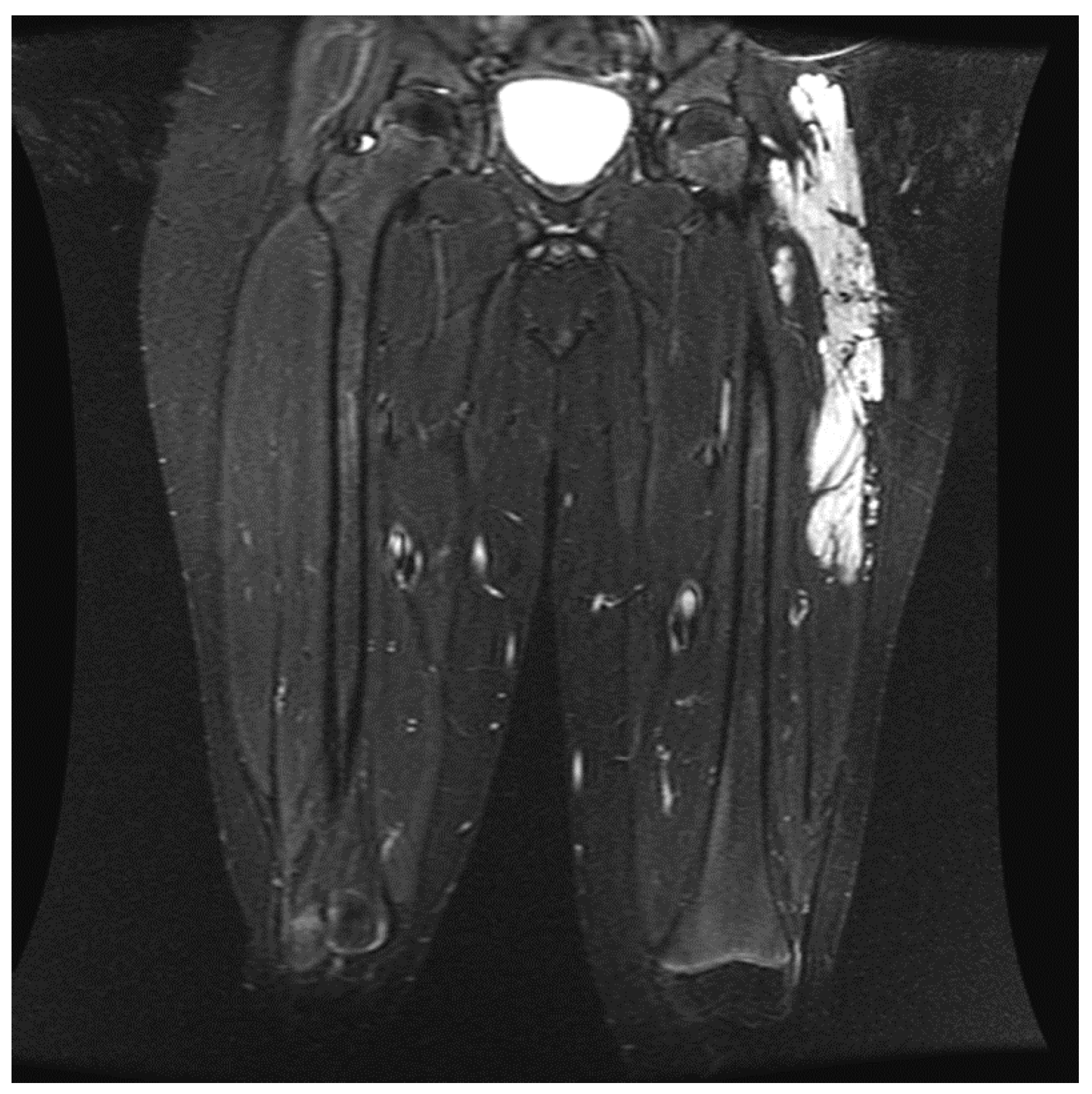

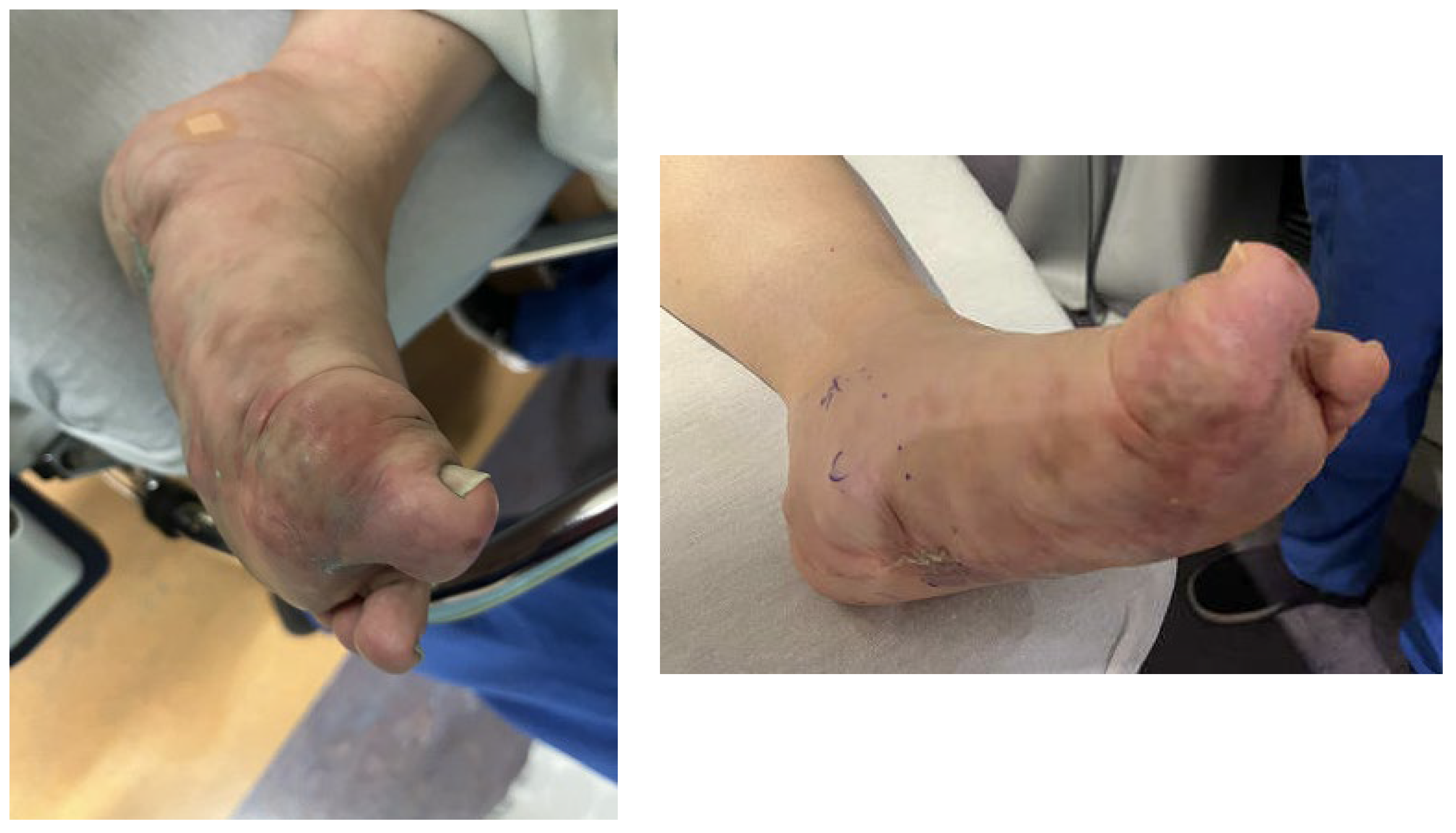

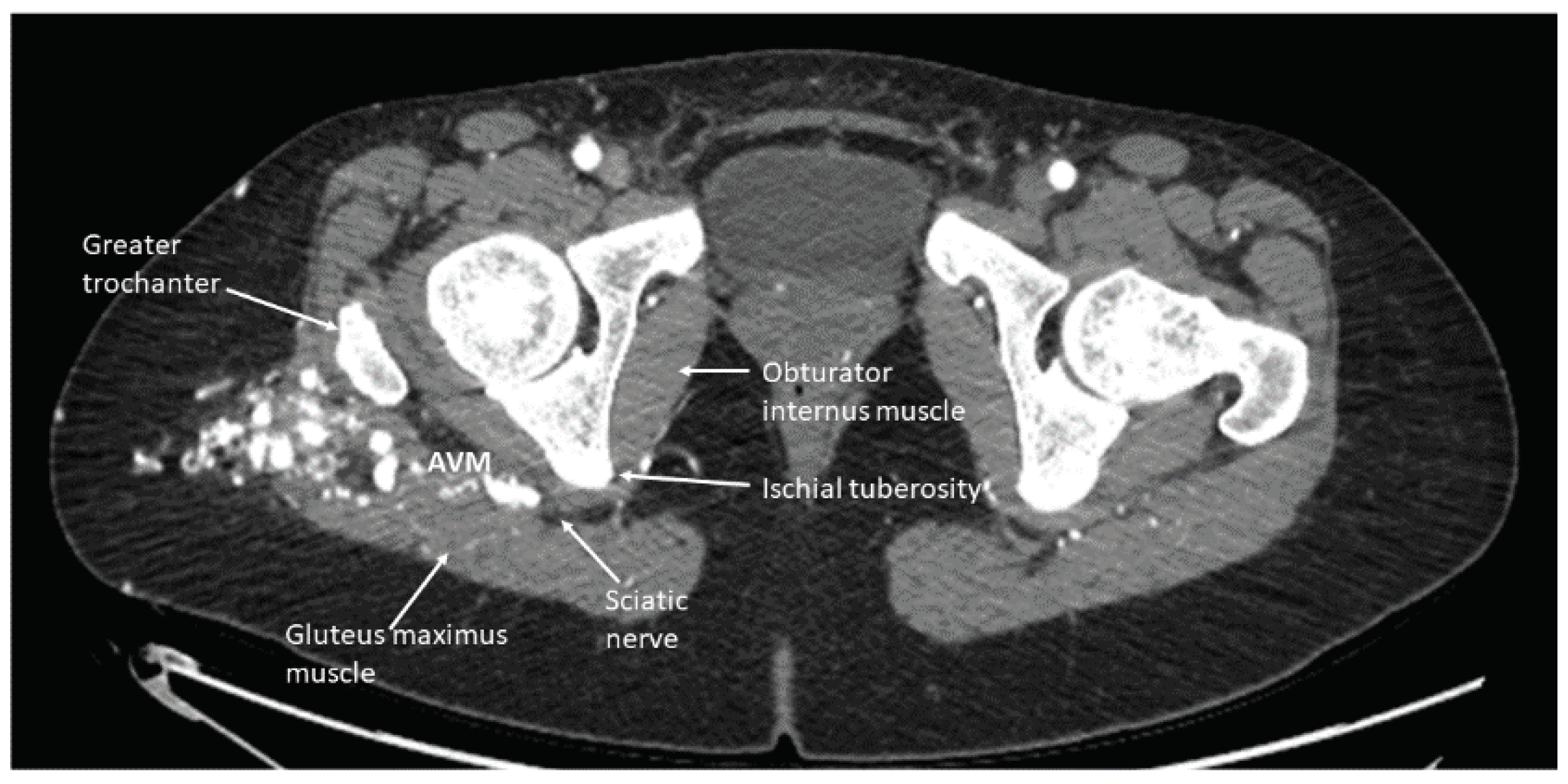

- When administering peripheral nerve blocks in pediatric patients, it is essential to consider potential complications from the nerve block and injecting the sclerosing/embolizing agents. The risk of nerve injury from nerve blocks is low, around 2 to 4 per 10,000 blocks in children, but should still be considered in all patients undergoing this type of therapy [15]. One patient developed a sciatic nerve injury following therapy with a peripheral nerve block. The malformation was located in the hip and close to the sciatic nerve (Figure 6). A quadratus lumborum nerve block was performed intraoperatively for postoperative pain control [16]. The patient made a full neurologic recovery after several months. The nerve injury was likely due to the therapy and unrelated to the peripheral nerve block. However, determining if the malformation is close to a nerve should raise concerns that signs of a nerve injury may be masked initially by a peripheral nerve block. As previously reported for other blocks by Pickle et al., we encountered no bleeding complications at the block sites after Enoxaparin administration. Continuous patient monitoring during and after the procedure is vital to ensure their safety. Close observation for potential complications related to the nerve block, such as nerve injury, is necessary. At UPMC CHP, we performed home phone call follow-ups for all the patients who received peripheral nerve block follow-up. Some of our patients required pre and post-procedure anticoagulation therapy, and we investigated if any of our patients developed any hematoma at the needle injection site. In addition, some patients require a longer time to recover from peripheral nerve blockade.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, A; Kozakiewicz, H. Histopathology of Vascular Anomalies. Vascular Anomalies Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 2011, Volume 38, 31-44. [CrossRef]

- Green, A; Alomari, A. Management of Venous Malformations. Vascular Anomalies Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 2011, Volume 38, 83-93. [CrossRef]

- Ben-David B, Kaligozhin Z, Biderman D. Quadratus lumborum block in managing severe pain after uterine artery embolization. Eur J Pain. 2018 Jul;22(6):1032-1034. [CrossRef]

- Murauski JD, Gonzalez KR. Peripheral nerve blocks for postoperative analgesia. AORN J. 2002 Jan;75(1):136-47. [CrossRef]

- Voepel-Lewis, Terri, Jay R. Shayevitz, and Shobha Malviya. "The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children." Pediatr Nurs 23.3 (1997): 293-297.

- Good, Marion, et al. "Sensation and distress of pain scales: reliability, validity, and sensitivity." Journal of nursing measurement 9.3 (2001): 219-238. [CrossRef]

- Merkel, Sandra, and Shobha Malviya. "Pediatric pain, tools and assessment." Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing 15.6 (2000): 408-414. [CrossRef]

- Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011 May;46(3):399-424. Epub 2011 Jun 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Howard, Richard F., et al. "Nurse-controlled analgesia (NCA) following major surgery in 10 000 patients in a children’s hospital." Pediatric Anesthesia 20.2 (2010): 126-134. [CrossRef]

- Lönnqvist PA, Morton NS. Postoperative analgesia in infants and children. Br J Anaesth. 2005 Jul;95(1):59-68. Epub 2005 Jan 21. Erratum in: Br J Anaesth. 2005 Nov;95(5):725. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, Hugh W., et al. "Peripheral nerve blocks improve analgesia after total knee replacement surgery." Anesthesia & Analgesia 87.1 (1998): 93-97. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Girish, et al. "Peripheral nerve blocks in the management of postoperative pain: challenges and opportunities." Journal of clinical anesthesia 35 (2016): 524-529. [CrossRef]

- Cardwell, Taylor W., et al. "The effects of perioperative peripheral nerve blocks on peri-and postoperative opioid use and pain management." The American Surgeon 88.12 (2022): 2842-2850. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Kenya, et al. "Vascular malformations of the head and neck." Auris Nasus Larynx 40.1 (2013): 89-92. [CrossRef]

- Neal JM, Barrington MJ, Brull R, Hadzic A, Hebl JR, Horlocker TT, Huntoon MA, Kopp SL, Rathmell JP, Watson JC. The Second ASRA Practice Advisory on Neurologic Complications Associated With Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine: Executive Summary 2015. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015 Sep-Oct;40(5):401-30. [CrossRef]

- Kocher M, Yilmaz S, Visoiu M. Sciatic nerve neuropraxia following embolization therapy in a patient receiving quadratus lumborum nerve block. J Clin Anesth. 2022 Jun;78:110601. Epub 2021 Nov 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickle J, Licata S, Lavage D, Visoiu M. Review of bleeding risk associated with prophylactic enoxaparin and indwelling paravertebral catheters: a pediatric retrospective study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2023 Jul 6:rapm-2023-104492. Epub ahead of . [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total Mean (Sd) |

No Block Mean (Sd) N = 802 (335 distinct patients) |

Block Mean (Sd) N = 52 (24 different patients) |

Absolute Standardized Mean Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11.7 (8.13) | 11.6 (8.1) | 14 (8.3) | 0.3 |

| Weight (Kg) | 45.65 (26.5) | 45.3 (26.8) | 50.7 (20) | 0.23 |

| Height (cm) | 140.71 (33.23) | 139.9 (33.7) | 153 (20.6) | 0.47 |

| BMI | 20.54 (5.52) | 20.5 (5.6) | 20.7 (5) | 0.04 |

| Female - n (%) | 517 (60.5%) | 491 (61.2%) | 26 (50%) | 0.23 |

| Sclerosing agent used for therapy | Percentage of sclerosing agent used for therapy (number of therapies) | Percentage of sclerosing agents used for treatment without nerve block (number of therapies) |

Percentage of sclerosing agent used for therapy with nerve block (number of therapies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| bleomycin | 5.6 (47) | 5.9 (47) | 0 (0) |

| bleomycin, doxycycline | 0.7 (6) | 0.8 (6) | 0 (0) |

| doxycycline | 24.5 (207) | 25.6 (203) | 7.8 (4) |

| ethanol | 1.5 (13) | 1.4 (11) | 3.9 (2) |

| onyx | 0.4 (3) | 0.4 (3) | 0 (0) |

| sotradecol | 64.1 (542) | 63 (500) | 82.4 (42) |

| sotradecol, bleomycin | 0.1 (1) | 0.1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| sotradecol, doxycycline | 0.8 (7) | 0.9 (7) | 0 (0) |

| sotradecol, ethanol | 2.2 (19) | 2 (16) | 5.9 (3) |

| Descriptive Table of Sclerosing Agent Doses by Surgery Location | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Sclerosing Agent | Procedure in Location - n | Procedure in Location - Median (IQR) |

| All Extremities | bleomycin_units | 16 | 9 (5.75 - 11) |

| doxycycline_mg | 50 | 167.5 (62.5 - 300) | |

| ethanol_ml | 3 | 5 (2.75 - 5) | |

| sotradecol_3_ml | 324 | 10 (7 - 12) | |

| Lower Extremities | bleomycin_units | 1 | 2.5 (2.5 - 2.5) |

| doxycycline_mg | 19 | 150 (47.5 - 200) | |

| ethanol_ml | 1 | 0.5 (0.5 - 0.5) | |

| sotradecol_3_ml | 137 | 10 (7 - 12) | |

| Chest, Back, Abdomen, and Pelvis | bleomycin_units | 9 | 15 (8 - 15) |

| doxycycline_mg | 80 | 200 (100 - 500) | |

| ethanol_ml | 4 | 12 (4.25 - 19) | |

| sotradecol_3_ml | 64 | 9.5 (5.88 - 12) | |

| Procedure Location | Morphine Milligram Equivalents (MME) Median (IQR) |

MME / Weight Median (IQR) |

Post-Surgery Pain Score Median (IQR) |

Length of Stay (Days) Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdomen And Pelvis | 9.25 (3.75 - 29.06) | 0.26 (0.16 - 0.5) | 5 (0.25 - 8) | 0.34 (0.23 - 2.16) |

| Chest And Back | 6.38 (3 - 15) | 0.25 (0.17 - 0.35) | 3 (0 - 6) | 0.25 (0.22 - 0.38) |

| Head And Neck | 7.5 (3.75 - 15) | 0.24 (0.15 - 0.34) | 2 (0 - 6) | 0.25 (0.21 - 0.97) |

| Lower Extremity | 7.5 (3.75 - 15) | 0.19 (0.11 - 0.31) | 3 (0 - 5) | 0.33 (0.25 - 1.18) |

| Upper Extremity | 7.5 (3.75 - 15) | 0.21 (0.14 - 0.32) | 3 (0 - 7) | 0.27 (0.21 - 1.18) |

| More Than One Location | 8.25 (4.5 - 15) | 0.24 (0.17 - 0.34) | 1 (0 - 5) | 0.25 (0.21 - 1.13) |

| Block Performed | Age (Mean) |

Weight (Kg) (Mean) |

MME/Kg (Mean) |

Ropivacaine (mg/kg) (Mean) | Pain Score (Median) |

LOS (Median) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Plexus | 5 | 21.2 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 7 | 0.46 |

| Digital | 8 | 36.6 | 0 | 0.27 | 0 | 0.25 |

| Erector Spinae | 6 | 18 | 0 | 2.78 | 0 | 0.23 |

| Femoral | 13.7 | 56.83 | 0.11 | 2.60 | 0 | 0.88 |

| Femoral & Lateral Femoral Cutaneous | 17.25 | 52.68 | 0.28 | 2.55 | 3.5 | 0.29 |

| Femoral & Sciatic | 9 | 33.6 | 0.21 | 2.08 | 0 | 0.94 |

| Interscalene | 13.5 | 73.45 | 0.11 | 1.36 | 0 | 0.73 |

| Lateral Femoral Cutaneous | 12.25 | 41.54 | 0.08 | 1.63 | 3 | 0.425 |

| Lumbar Plexus | 20 | 64.56 | 0.30 | 1.12 | 7 | 1.13 |

| Sciatic | 13.1 | 51.28 | 0.16 | 1.90 | 0 | 2.17 |

| Supraclavicular | 10 | 34.33 | 0.12 | 1.45 | 0 | 0.53 |

| Outcome | Estimate (95% CI) | P-Value | Adjusted Estimatea (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log-Linear Mixed Models | ||||

| Morphine Milligram Equivalents | 0.43 (0.33, 0.58) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.33, 0.56) | <.001 |

| Morphine Milligram Equivalents/ Weight | 0.9 (0.86, 0.95) | <.001 | 0.91 (0.86, 0.96) | 0.001 |

| Linear Mixed Models | ||||

| Pain | -1.17 (-2.2, -0.1) | 0.027 | -1.25 (-2.3, -0.2) | 0.018 |

| Negative Binomial Mixed Models | ||||

| LOSb (Rounded to Nearest Day) | 0.94 (0.4, 2) | 0.875 | 1.25 (0.6, 2.7) | 0.572 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).