Background Note

In India, there have been notable advancements in understanding mental health and disabilities, yet a significant challenge remains in meeting the needs of the vast number of individuals requiring treatment and care compared to the available social and physical support infrastructure. Consequently, many people with psychosocial disabilities continue to reside in hospitals post-recovery, as they lack the opportunity to reintegrate into society or are not wanted by, or unable to locate, their families.

The discourse surrounding mental health has evolved, with increasing emphasis on deinstitutionalization and community involvement. International treaties such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), ratified by India, uphold the rights of individuals with disabilities to live free from discrimination and as equal members of society. National legislations, including the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act and the Mental Healthcare Act of 2017, aim to adopt a human rights-based approach to disability rights.

However, implementation of these laws has been slow and hindered by a lack of political will, with remnants of institutionalized care still prevalent. Civil society initiatives, such as halfway homes, have emerged to address service gaps, offering temporary accommodation and skills development for individuals transitioning to independent living. Yet, halfway homes often reflect a medical approach that views individuals through a deficit model rather than recognizing their capacities, contradicting the human rights perspective promoted by the CRPD.

Gender disparities also influence pathways to recovery and reintegration, with a significant number of women affected by mental health systems. Halfway homes, particularly those in the private sector, may lack privacy, impose financial burdens, and focus excessively on vocational training, neglecting other aspects of meaningful community integration. Additionally, their isolated locations hinder social inclusion.

Even the Supreme Court of India has recognized the need for halfway homes to provide comprehensive services alongside physical infrastructure. Martha Nussbaum highlights how an exclusive focus on economic development fails to address the fundamental needs for agency, dignity, and self-respect, which are crucial for mental health recovery.

While some organizations, like the Medico Pastoral Association and Paripurnata, have evolved their approaches to halfway homes, the underlying principles often perpetuate outdated notions of illness and therapy. The halfway home exists in a complex space, blending innovation with traditional perspectives on mental health treatment and rehabilitation. (ray, 2023)

Introduction

“Those who suffer from mental illness are stronger than you think. We must fight to go to work, care for our families, be there for our friends, and act ‘normal’ while battling unimaginable pain.” – Anonymous (Mahabir, 2019)

The quote attributed to an anonymous individual highlights the resilience of individual grappling with mental illness, who often face considerable hurdles while fulfilling daily obligations. It underscores the pervasive misunderstanding and stigma attached to mental health, frequently trivialized, or disregarded as a manageable issue. Mental well-being warrants equal attention alongside physical health, especially in areas lacking resources and awareness regarding mental health. In today’s fast-paced world, societal pressures exacerbate stress and anxiety, particularly among youth, underscoring the urgency of combating stigma and raising awareness about mental health. This justifies exploring alternative approaches to designing mental health facilities, such as integrating therapeutic architectural principles into community-based housing within urban environments, to offer more effective and sustainable long-term care. (Mahabir, 2019)

Human performance is intricately tied to health, which is influenced by the built environment. Architects should prioritize creating spaces conducive to optimal performance by considering social, physiological, and psychological factors. The intersection of architecture and neuroscience has elucidated how elements like colour and light impact behaviour and well- being, especially within healthcare settings. Research indicates that deliberate choices in colour and lighting can positively affect various healthcare outcomes, such as reducing errors, easing stress, and improving patient and staff satisfaction. Natural light, particularly, has been recognized as beneficial for enhancing patient well-being and overall health outcomes in healthcare settings. Therefore, incorporating these elements into architectural design can foster environments that promote both physical and mental health.

1. Definition of the Problem, Aims and Objectives

1.1. Problem

The current provision of halfway homes to tackle these challenges is insufficient in quantity and lacks designs that promote comprehensive healing. Instead, these halfway homes primarily prioritize accommodation and medical services. The state of mental healthcare facilities in India is a matter of significant concern, particularly regarding the substandard living conditions offered to patients. Many treatment centres suffer from insufficient rooms lacking adequate ventilation, lighting, and sometimes windows. Patients with varying conditions often have to share rooms, leading to accidents and unfortunate incidents. High-risk patients are confined to poorly lit and cramped spaces, impeding their recovery process. Even patients with lower risks and some degree of freedom lack environments conducive to healing. It is essential to improve the living conditions for high-risk patients by incorporating more greenery and cultivating a welcoming, vibrant atmosphere for all.

1.2. Aim

The primary objective of this research is to investigate a de-institutionalized approach as an alternative solution to the current architectural design of healing spaces. The focus is on establishing resort-like open environments within society specifically tailored for individuals with milder mental health challenges. The goal is to explore how this approach can be enhanced through a community-based housing facility that incorporates principles of therapeutic architecture, aiming to create a healing-induced environment within existing unhealthy settings. The aim is to develop a more effective long-term approach to mental health recovery.

The research seeks to design a therapeutic space that integrates elements of nature, with an emphasis on achieving optimal levels of natural lighting and ventilation. Additionally, the study aims to incorporate environmental design principles that promote inner peace and facilitate faster recovery. Furthermore, the research aims to explore the integration of colour therapy concepts into the design to enhance the therapeutic environment.

1.3. Objective

This study aims to analyse the architectural elements of current facilities and their impact on users’ experiences, focusing on community-based halfway homes as potential models for therapeutic environments. It explores therapeutic architecture principles and their potential to enhance the healing journey of individuals, advocating for a sustainable approach to mental health recovery. Additionally, the study examines architectural initiatives to reduce mental health stigma by integrating buildings into their surroundings and serving the community. It emphasizes the need for dedicated spaces for rehabilitation, skill development, and employment opportunities post-recovery, as well as promoting community and support through communal areas and performance spaces while balancing functionality and aesthetics in infrastructure design.

2. Halfway Home

A halfway house, also known as a residential treatment centre, serves as a transitional living environment for individuals transitioning from rehabilitation programs to independent living. It aims to provide support and assistance to residents, helping them develop essential life and social skills necessary for successful reintegration into society and ongoing recovery. Staff members, including house managers and licensed medical professionals, offer various programs and interventions such as clinical treatment, peer support groups, and life skills training. The role of halfway houses includes acting as a replacement for family or home, catering to individuals without support systems, facilitating successful reintegration into society, bridging the gap between correctional facilities and the community, providing employment preparation programs, instilling family values, and contributing to moral regeneration. (ray, 2023)

3. Therapeutic Architecture for Half Way Homes

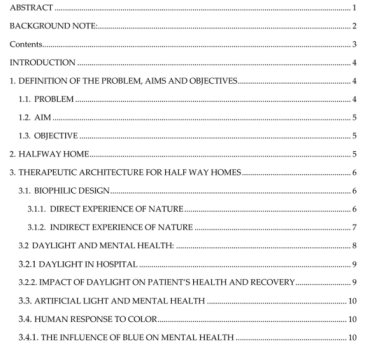

In the late 19th century, Dr. Thomas Kirkbride pioneered the idea that the design of mental health facilities significantly impacts patients’ well-being, advocating for incorporating natural elements into asylum design. Since then, therapeutic architecture, defined by Dr. E. Chrysikou as a “people-centered, evidence-based discipline,” has been extensively studied. It aims to integrate spatial elements that interact with individuals’ physiology and psychology, catering to occupants’ needs, especially during the recovery process from mental disorders. Morgenthaler argues that while architecture itself does not heal people, manipulating structures and space can create a therapeutic environment by leveraging environmental factors like sound, color, views, smell, and light.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating main principles of a therapeutic architecture and how it effects mental health and well- being.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating main principles of a therapeutic architecture and how it effects mental health and well- being.

The focus is on adapting therapeutic architecture principles to community-based housing interventions for mentally ill children and adolescents, aiming to demonstrate that a healing environment can be achieved in urban settings. This involves exploring evidence-based theoretical underpinnings such as the role of environmental factors in mental health and well- being such as - (Mahabir, 2019)

3.1. Biophilic Design

Humans have an innate connection to nature, which is increasingly recognized as essential for our well-being, especially in urban environments lacking green spaces. Biophilic architecture addresses this need by integrating natural elements into our built environment, creating spaces that mimic natural settings and fostering a sense of connection to the natural world. This design approach, seen in both small-scale projects and entire biophilic cities, prioritizes vibrant urban spaces that promote health and well-being. By incorporating elements like natural light, ventilation, and visual connections to nature, biophilic architecture can positively impact mental and emotional well-being. This aligns with the theory of Biophilia, which suggests that humans benefit from being in proximity to nature. Recent research underscores the numerous benefits of biophilic architectural design across various contexts. (Mahabir, 2019)

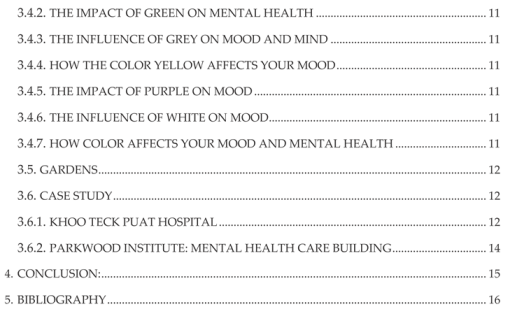

3.1.1. Direct Experience of Nature

The direct experience of nature is essentially tangible contact with natural features that include; natural vegetation, lighting, ventilation and other passive design strategies which has been proven to reduce stress and increase physical health, performance and productivity. Another significant aspect is the inclusion of natural landscapes which can be achieved through the development of self-sustaining eco-systems into the built environment. The element of water is also known to be very therapeutic as it creates a multi-sensory experience for the user through movement, sounds, touch and sight, essentially stimulating the human senses which has the power to eliminate stress, increase health and assist in the process of recovery.

The direct experience of nature is essentially tangible contact with natural features that include; natural vegetation, lighting, ventilation and other passive design strategies which has been proven to reduce stress and increase physical health, performance and productivity. Another significant aspect is the inclusion of natural landscapes which can be achieved through the development of self-sustaining eco-systems into the built environment. The element of water is also known to be very therapeutic as it creates a multi-sensory experience for the user through movement, sounds, touch and sight, essentially stimulating the human senses which has the power to eliminate stress, increase health and assist in the process of recovery. (Mahabir, 2019)

Figure 2.

The sketch portrays the direct experience and relationship between nature, man and architecture.

Figure 2.

The sketch portrays the direct experience and relationship between nature, man and architecture.

3.1.2. Indirect Experience of Nature

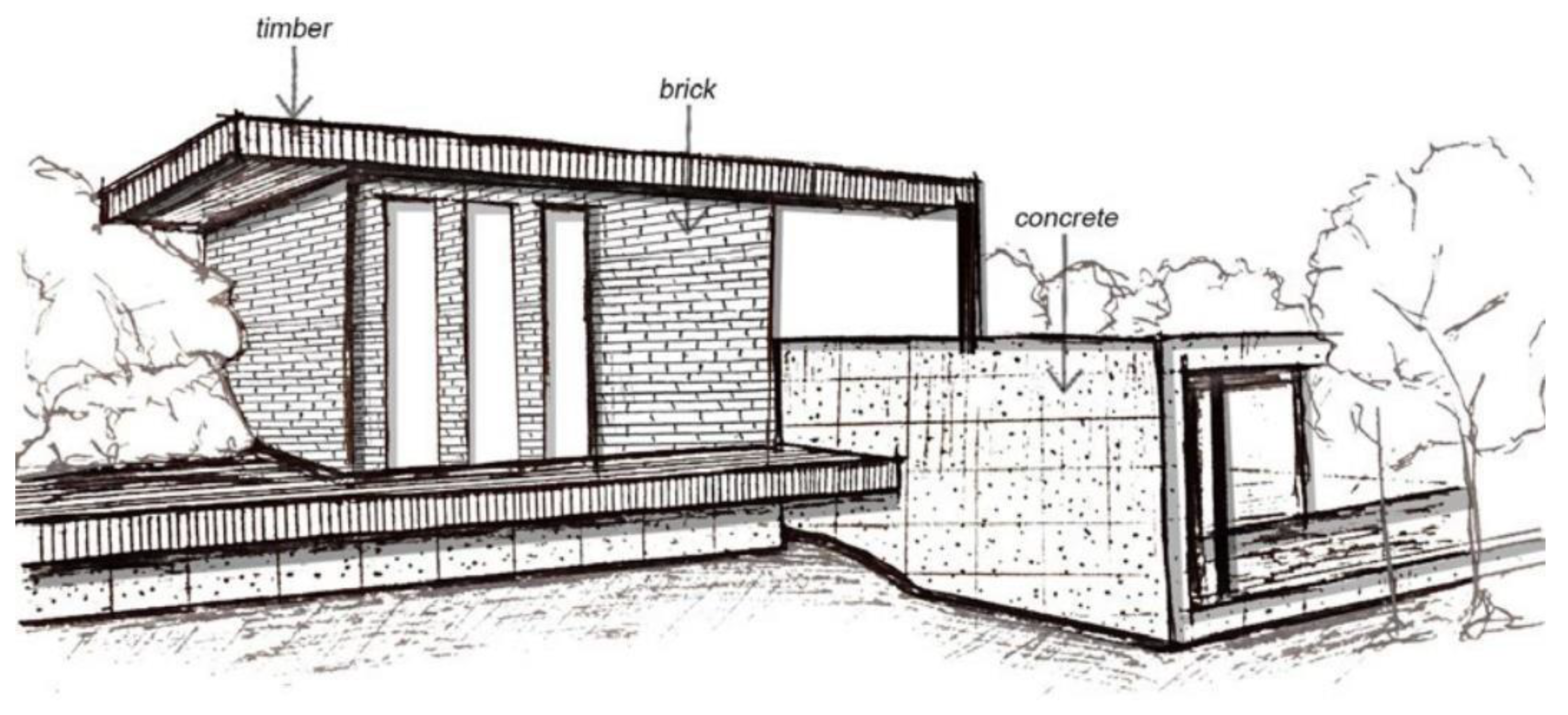

On the other hand, an indirect experience of nature refers to elements included in the architecture and design of a building that aims to depict a sense of connection with nature. This can be done through images, murals and paintings that represent the essence of nature. It can also be achieved through the use of natural colours and materials that age and evolve with time creating an immediate connection between the texture and the individual, which has been proven to be mentally stimulating. Other significant design features, if unable to attain naturally, are the simulations of natural light and air which can be achieved through innovative ways of using interior lighting and mechanical ventilation to mimic natural features as well as depicting nature in the structural design of the building. also known to be very therapeutic as it creates a multi-sensory experience for the user through movement, sounds, touch and sight, essentially stimulating the human senses which has the power to eliminate stress, increase health and assist in the process of recovery.

On the other hand, an indirect experience of nature refers to elements included in the architecture and design of a building that aims to depict a sense of connection with nature. This can be done through images, murals and paintings that represent the essence of nature. It can also be achieved through the use of natural colours and materials that age and evolve with time creating an immediate connection between the texture and the individual, which has been proven to be mentally stimulating. Other significant design features, if unable to attain naturally, are the simulations of natural light and air which can be achieved through innovative ways of using interior lighting and mechanical ventilation to mimic natural features as well as depicting nature in the structural design of the building. (Mahabir, 2019)

Figure 3.

The sketch portrays the indirect experience of nature, in this case, through the use of materiality that ages with time and the use of nature inspired structural design elements (timber ceiling panels and columns).

Figure 3.

The sketch portrays the indirect experience of nature, in this case, through the use of materiality that ages with time and the use of nature inspired structural design elements (timber ceiling panels and columns).

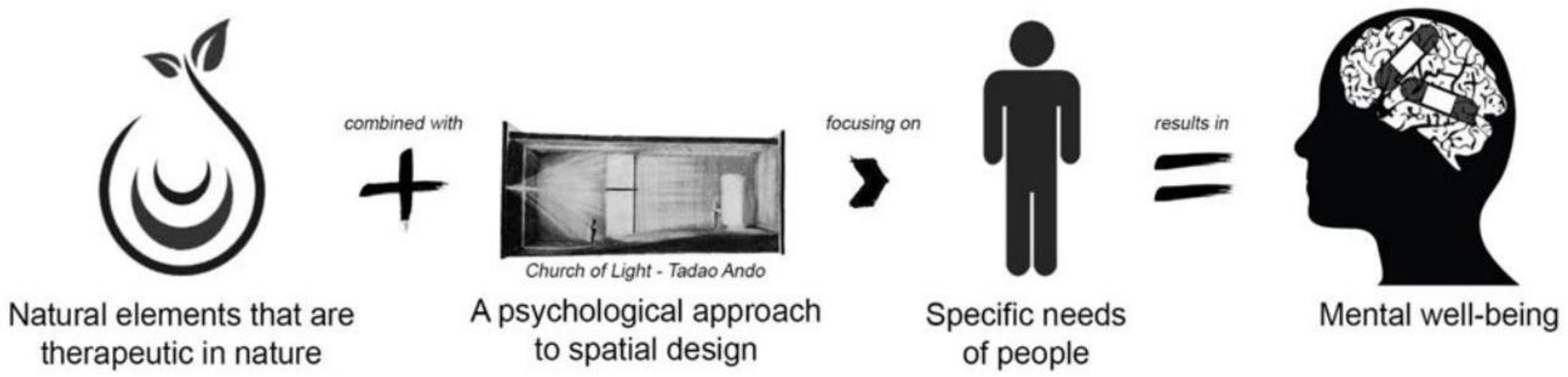

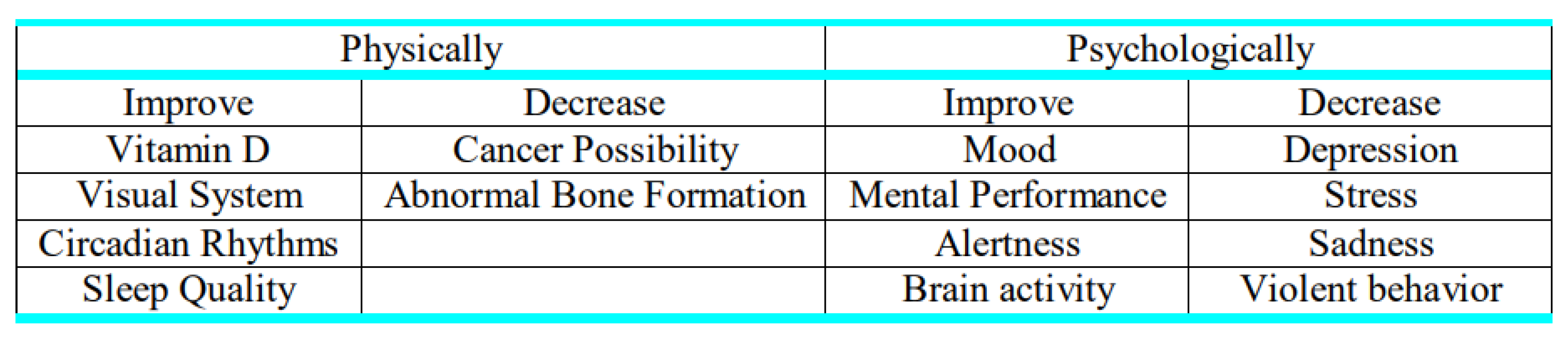

3.2. Daylight and Mental Health

Throughout history, natural daylight has been crucial for illumination, but recent research has underscored its significant impact on mental health. Exposure to higher levels of illuminance, typically ranging from 1000 to 10,000 lux at the eye, activates photoreceptors, leading to improvements in mood, behavior, and physiology. With a color temperature range of 5000 to 10000 K, daylight encompasses the full light spectrum and substantially influences mental well- being. Studies have shown that exposure to daylight can enhance vitality, mood, self-reported sleep quality, and positively influence conditions such as eating disorders, depression, circadian rhythm, and recovery in hospital settings.

In designing healing spaces, building orientation is paramount during the initial design phases. It is crucial in establishing an environment conducive to wellness, yet often overlooked by designers in the healthcare sector who prioritize physical layout concerns. Decisions about building orientation should guide the design of elements such as shading mechanisms, window placement, and architectural profiles, particularly in healing spaces where the aim is to foster a therapeutic atmosphere. The orientation directly impacts window design, affecting the quality of natural light and access to outdoor views, thus influencing the overall experience and well- being of occupants.

Providing access to outdoor views through windows in healing environments can enhance patients’ sense of well-being and connection to nature. Studies have demonstrated that the absence of such views can negatively impact occupants’ well-being. Windows play a crucial role in bringing daylight into built environments and have been linked to occupants’ psychological well-being. Proper window design and size are essential for maximizing daylight in facilities and maintaining a connection with the outside world. Skylights complement windows by allowing natural light to penetrate deep into the building, reducing the need for artificial lighting and contributing to a less stressful work environment for occupants. Factors such as the direction of light, window size, and glare reduction methods affect the quality of daylight indoors. (Husein Ali Husein, 2020)

Figure 4.

Natural light benefits for human health (Shishegar & Boubekri, 2016). (Husein Ali Husein, 2020).

Figure 4.

Natural light benefits for human health (Shishegar & Boubekri, 2016). (Husein Ali Husein, 2020).

3.2.1. Daylight in Hospital

Healthcare facilities are designed to promote patient treatment and enhance overall well-being. The interior design of therapeutic spaces plays a crucial role in creating environments that are flexible, secure, intimate, and relaxing. Neglecting physical and interior design aspects in therapeutic areas can lead to user dissatisfaction and heightened anxiety.

Proper lighting is vital in healthcare settings to create healing conditions. Both natural and artificial light should be optimized to ensure adequate illumination, facilitating ease of navigation, reducing stress, and minimizing confusion and time wastage The level of illumination, measured in lux, should meet the requirements for various activities. For instance, on cloudy days, outdoor light intensity is around 1000 lux, while on sunny days, it exceeds 10,000 lux.

The placement of windows in hospital rooms should also be carefully considered based on sun orientation to prevent direct exposure, which can lead to depression and eye strain. (Husein Ali Husein, 2020)

Figure 5.

Comparison of healthcare with architectural environment design (after Kellert & Calabrese (2015)).

Figure 5.

Comparison of healthcare with architectural environment design (after Kellert & Calabrese (2015)).

3.2.2. Impact of Daylight on Patient’s Health and Recovery

Integrating natural daylight into healthcare facilities brings numerous benefits, including improved brightness, reduced heating costs, and enhanced well-being for patients and staff. Patients prefer environments where they can maintain visual contact with medical professionals, aided by clear signage and effective navigation to reduce anxiety. Access to outdoor views is crucial for patients’ physical and psychological health, aiding in the recovery process. Studies underscore the positive impact of natural lighting on patients’ health and recovery, as well as its benefits for hospital staff and the overall environment. Research shows that exposure to natural light indoors can reduce stress, shorten post-operative stays, and alleviate pain. Proper lighting improves biological cycles, transparency, and visual clarity while reducing errors and hospital stays. However, excessive exposure to artificial light can lead to various psychological and physical issues. (Husein Ali Husein, 2020)

3.3. Artificial Light and Mental Health

Artificial lighting complements daylighting in constructed spaces, although occupants generally prefer daylight. While recent advancements in artificial lighting technology have produced high- quality light sources comparable to daylight, they may not be as effective for promoting positive mental health outcomes. Complaints about artificial lighting in constructed spaces often stem from the absence of natural light, rather than issues with artificial lighting itself. Integrating both artificial and daylighting is advocated for, with approaches like Permanent Supplementary Artificial Lighting of Interiors (PSALI) combining the two to positively influence occupants. PSALI utilizes natural light where possible and supplements with artificial lighting in areas lacking sufficient daylight. (t.kohl, 2020)

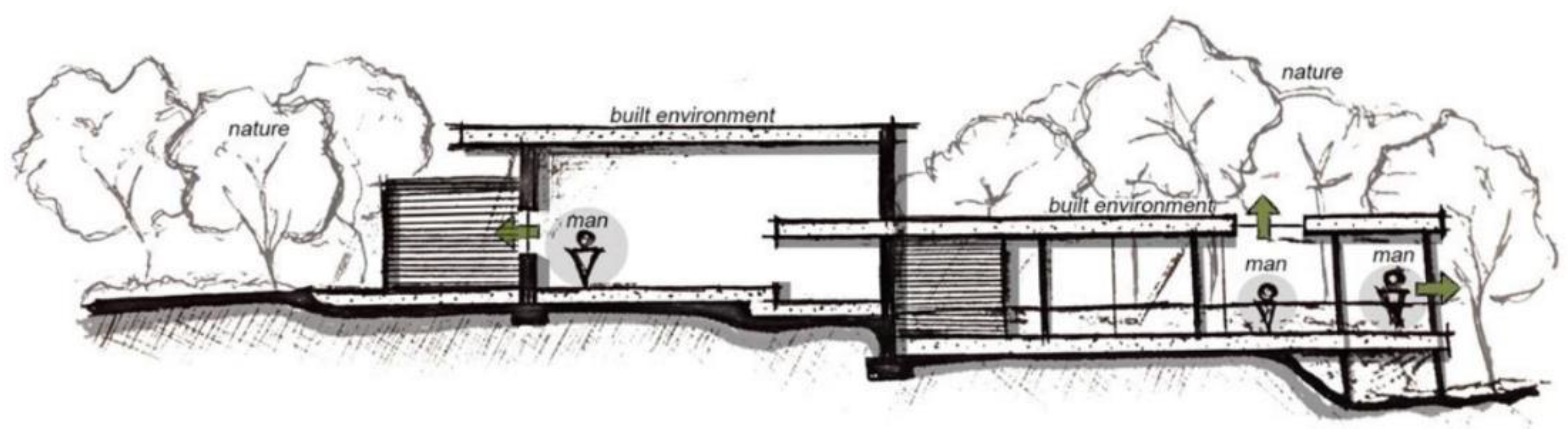

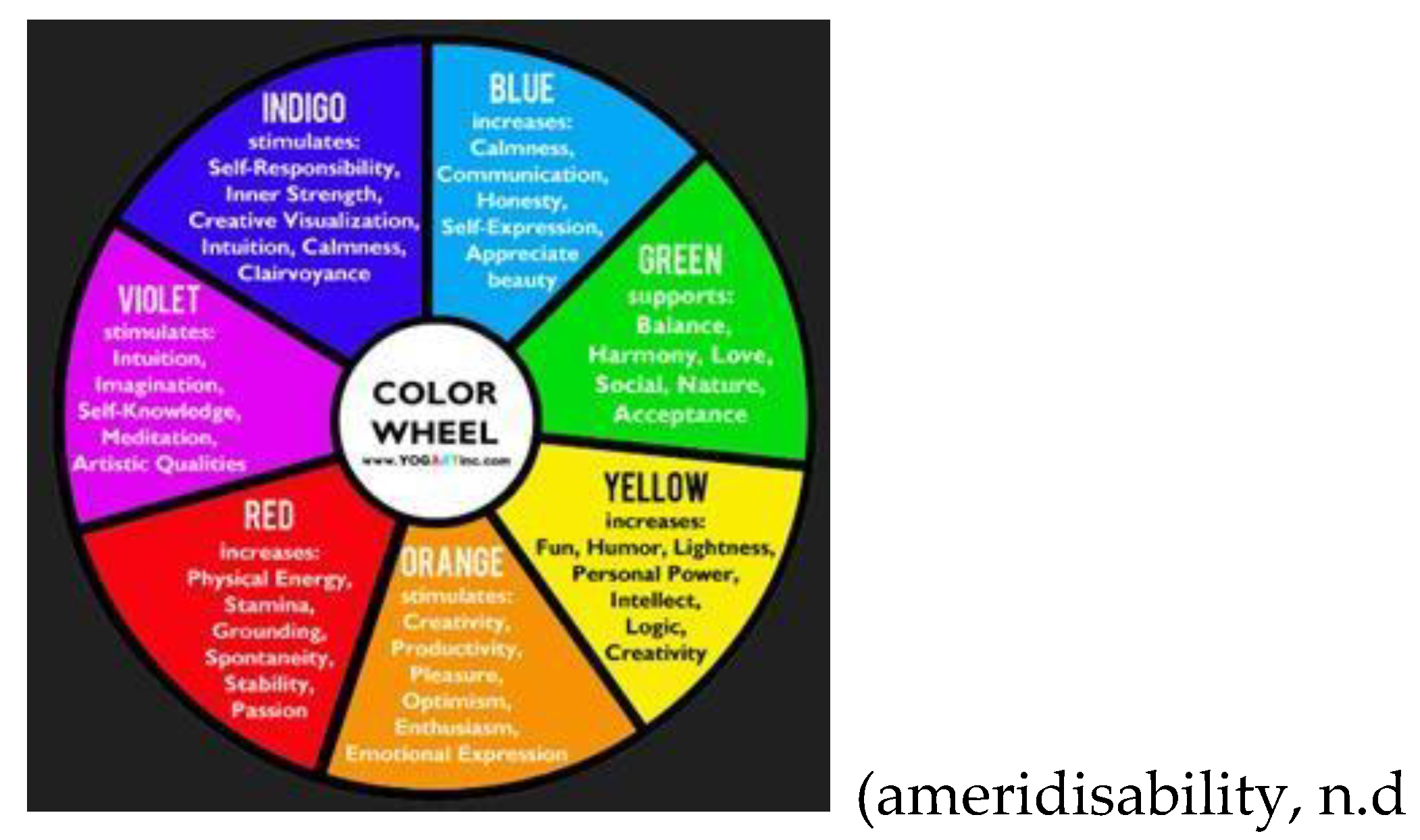

3.4. Human Response to Color

Color therapy utilizes different colors to stimulate or calm individuals, aiming to promote mental and physical well-being by influencing hormonal and biochemical processes. In healing centers, colored lights or silk may be used during treatments to influence mood, while meditation techniques involving colors can energize the body.

Colors impact emotions by interacting with the nervous system, with warm colors promoting energy and cool colors inducing calmness. When designing mental hospital environments, it’s essential to consider the psychological effects of colors to create positive spaces.

In halfway homes, patients can benefit from color therapy through simple methods like wearing colorful clothing or decorating rooms with vibrant colors. Even dietary choices can be influenced by color therapy, offering additional opportunities to promote well-being. Integrating color therapy into mental hospital environments can create uplifting and supportive spaces for patients. (Dr Amrapali Mahadev Jogdand, 2022)

Figure 6.

Effect of colors on human beings.

Figure 6.

Effect of colors on human beings.

3.4.1. The Influence of Blue on Mental Health

In an early 1930s study by Siegfried E Katz, hospitalized patients showed a preference for the color blue, suggesting a potential association between mental health challenges and this color. Common phrases like “having the blues” further reinforce this connection. However, blue can also evoke feelings of confidence, coolness, and determination, indicating a nuanced relationship with mental well-being.

3.4.2. The Impact of Green on Mental Health

Green is widely recognized for its associations with health, growth, and nourishment, often utilized by health brands to convey a sense of well-being. Psychologically, green promotes trust and well-being, fostering balanced mental states. Spending time in green environments evokes feelings of restoration and neutrality, contributing to mental well-being

3.4.3. The Influence of Grey on Mood And Mind

Grey, associated with calmness and neutrality, provides balance to emotions and promotes stillness. Its neutrality encourages a mindset of authority and strength, beneficial for those dealing with anxiety or stress. Grey facilitates cognitive-behavioral therapy by fostering balance and perspective.

3.4.4. How the Color Yellow Affects Your Mood

Yellow, representing happiness and energy, influences mood significantly. While it grabs attention effectively, excessive exposure can lead to anxiety and low self-esteem. Moderation is key to benefiting from yellow’s positive effects on creativity and well-being.

3.4.5. The Impact of Purple on Mood

Purple, linked to wisdom and creativity, has a soothing effect on mood. Its unique blend of energetic and calming qualities promotes calmness and coziness, enhancing mood and creativity.

3.4.6. The Influence of White on Mood

White, associated with purity and clarity, lifts spirits and creates a sense of newness and cleanliness. Used in modern settings to convey hygiene and spaciousness, white complements other colors to enhance mental clarity and uplift mood. Combining clean, natural colors like white with others can foster mental clarity, particularly during challenging times.

3.4.7. How Color Affects Your Mood and Mental Health

The impact of color on mood and mental well-being varies greatly from person to person and is influenced by individual experiences. Understanding one’s personal responses to different colors is essential for utilizing them effectively to improve mood. Colors can alter spatial perception, evoke emotions, and affect physiological responses, with warm colors stimulating visually and cool colors promoting calmness and relaxation.

In healthcare settings, the visual environment significantly influences the morale and productivity of staff and can even lead to faster patient recovery rates, sometimes by up to 10%. This improvement is often attributed to elements such as the use of appropriate colors in interior design. Color can shape perceptions and responses to surroundings, ultimately impacting patient recovery rates and enhancing the overall experience for patients, staff, and visitors. Additionally, color serves as a powerful tool for. coding, navigation, and wayfinding, promoting a sense of well- being and autonomy. (Dr Amrapali Mahadev Jogdand, 2022)

3.5. Gardens

The theme of gardens encompasses the incorporation of open spaces within hospital premises, with sub themes ranging from therapeutic gardens to Alzheimer’s facilities, and from historical perspectives to moral therapy. Gardens are not exclusively associated with mental healthcare design but are increasingly recognized as beneficial in general healthcare contexts as well. Thus, the theme of gardens is holistic and highly pertinent to mental health care.They promote well- being by providing environments free from harsh noises and demands, facilitating outdoor breaks for nursing staff, and offering therapeutic benefits for psychiatric patients through exposure to nature. Gardens serve as spaces for relaxation, reflection, and socialization, with enduring positive associations for patients. (Kathleen Connellan, Mads Gaardboe, Damien Riggs, Reinschmidt, & Mustillo, 2013)

3.6. Case Study

3.6.1. Khoo Teck Puat Hospital

Location: Yishun Central, Singapore Architects/ designers: CPG consultants Date of completion: 2010.

Figure 7.

Khoo Teck Puat Hospital.

Figure 7.

Khoo Teck Puat Hospital.

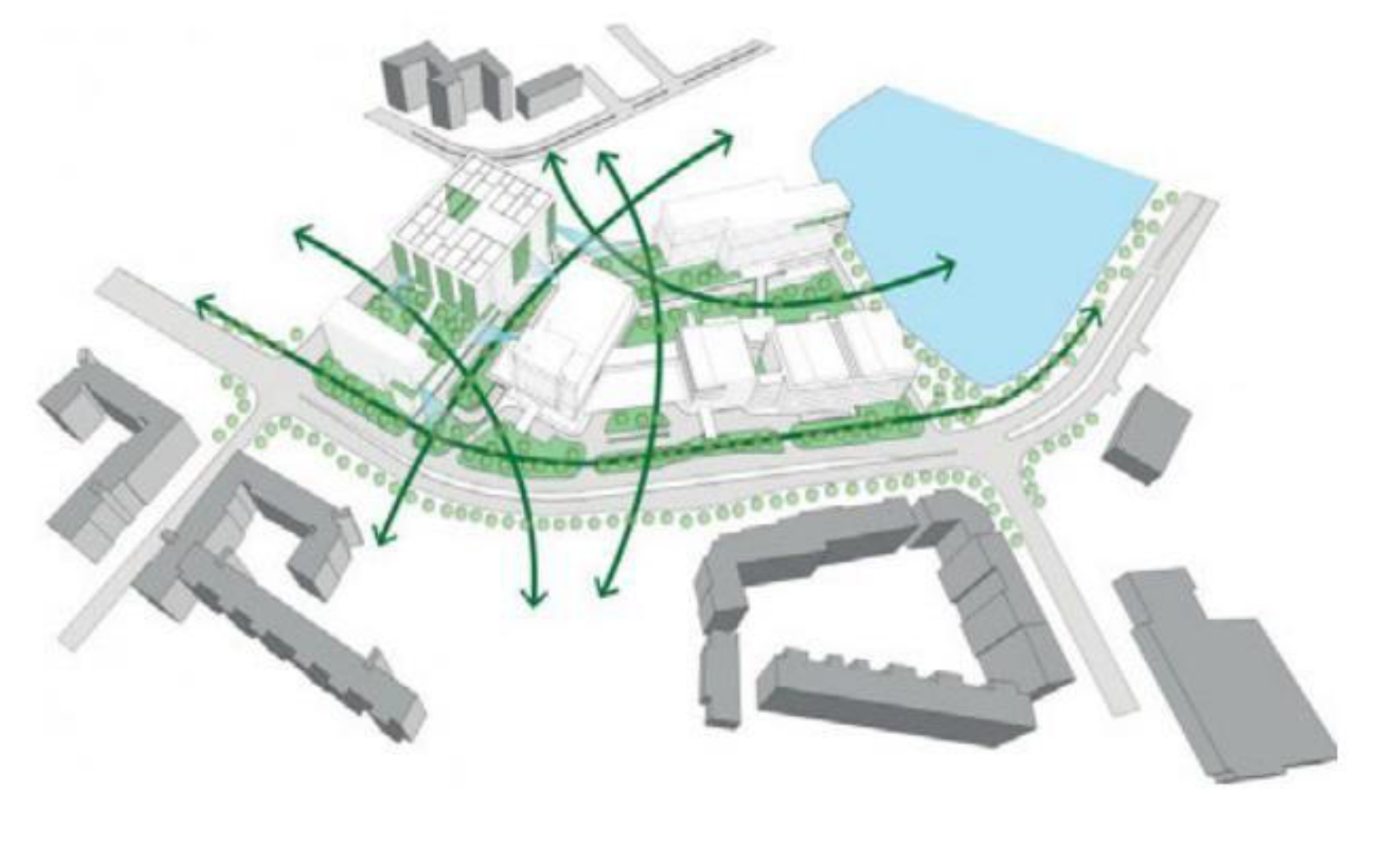

Khoo Teck Puat Hospital is renowned for its biophilic design, aiming to create a healing environment within the constraints of a dense urban setting. The facility, housing 590 beds, blends medical expertise with personalized care. Architects prioritized a hassle-free experience for users while fostering a natural healing environment to enhance patient recovery and staff well-being.

Central to the concept of therapeutic architecture is designing with occupants in mind. The hospital’s design revolves around three building blocks surrounding a central courtyard, maximizing natural daylight and ventilation to minimize energy consumption. This approach integrates environmentally friendly features, reducing reliance on air conditioning.

The architects embraced biophilic design principles, envisioning the hospital as a forest-like environment. They incorporated existing natural elements like water features and greenery from the adjacent pond and park into the hospital’s core, aiming for seamless integration with the surroundings. The V-shaped configuration of building blocks optimizes natural lighting and ventilation, ensuring calming views and physical interaction with nature throughout the facility.

Eco-friendly measures further enhance the hospital’s sustainability and integration into the ecosystem. These include utilizing the adjacent pond for irrigation, installing solar panels, and implementing “Wing walls” to mitigate sunlight and harness winds. Roof gardens and urban farming areas offer direct contact with nature and provide fresh produce for the hospital kitchen, promoting an engaging and educational experience.

Figure 8.

Diagrammatic representation illustrating how the building ‘draws in’ the existing pond and park into the heart of the hospital. 2010, By Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Living-Future.org.

Figure 8.

Diagrammatic representation illustrating how the building ‘draws in’ the existing pond and park into the heart of the hospital. 2010, By Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Living-Future.org.

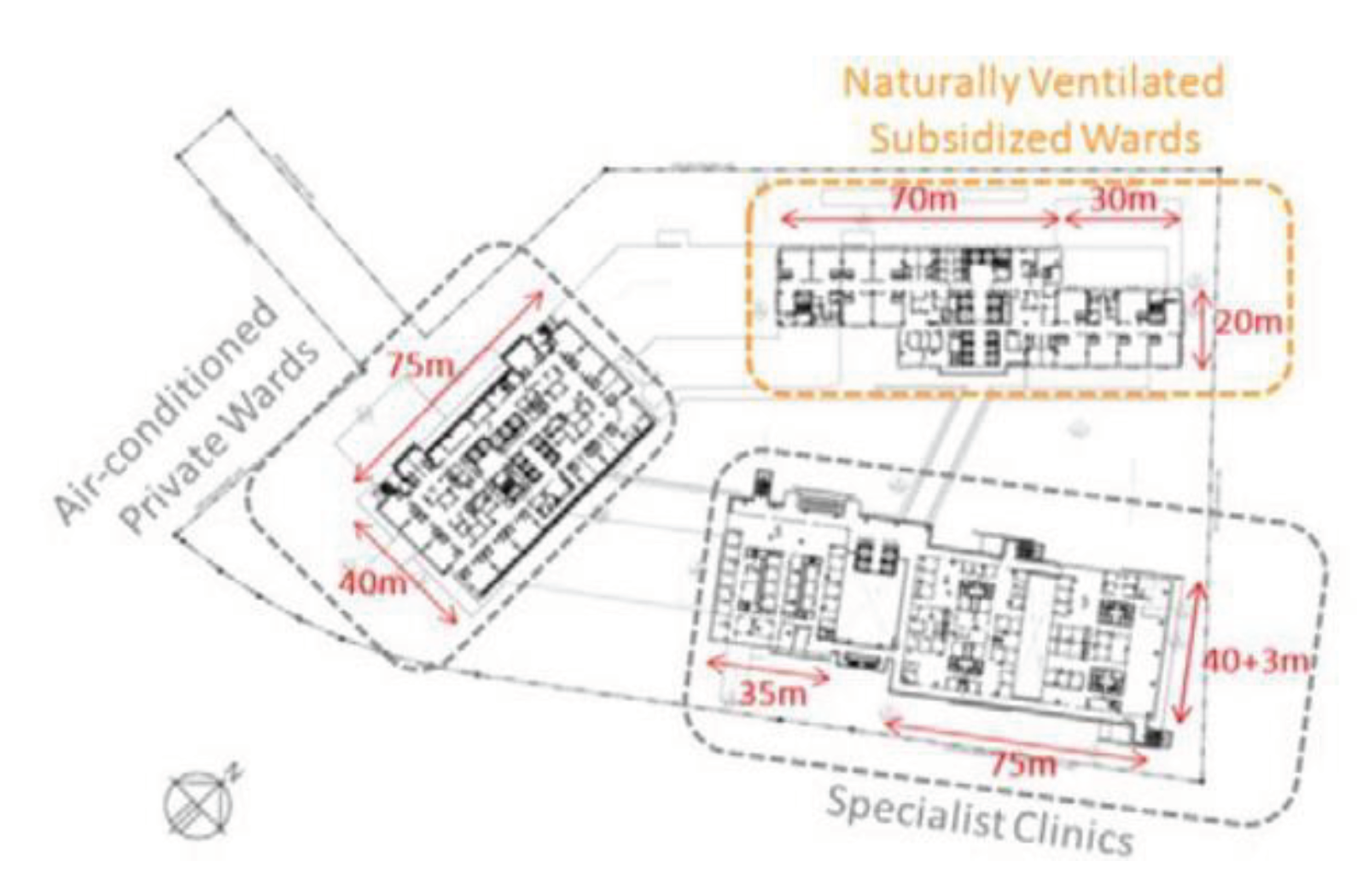

Figure 9.

Floor plan diagram portraying the aspect ratio of each building block. 2012, By CPG Consultants from Tan Shao Yen’s dissertation.

Figure 9.

Floor plan diagram portraying the aspect ratio of each building block. 2012, By CPG Consultants from Tan Shao Yen’s dissertation.

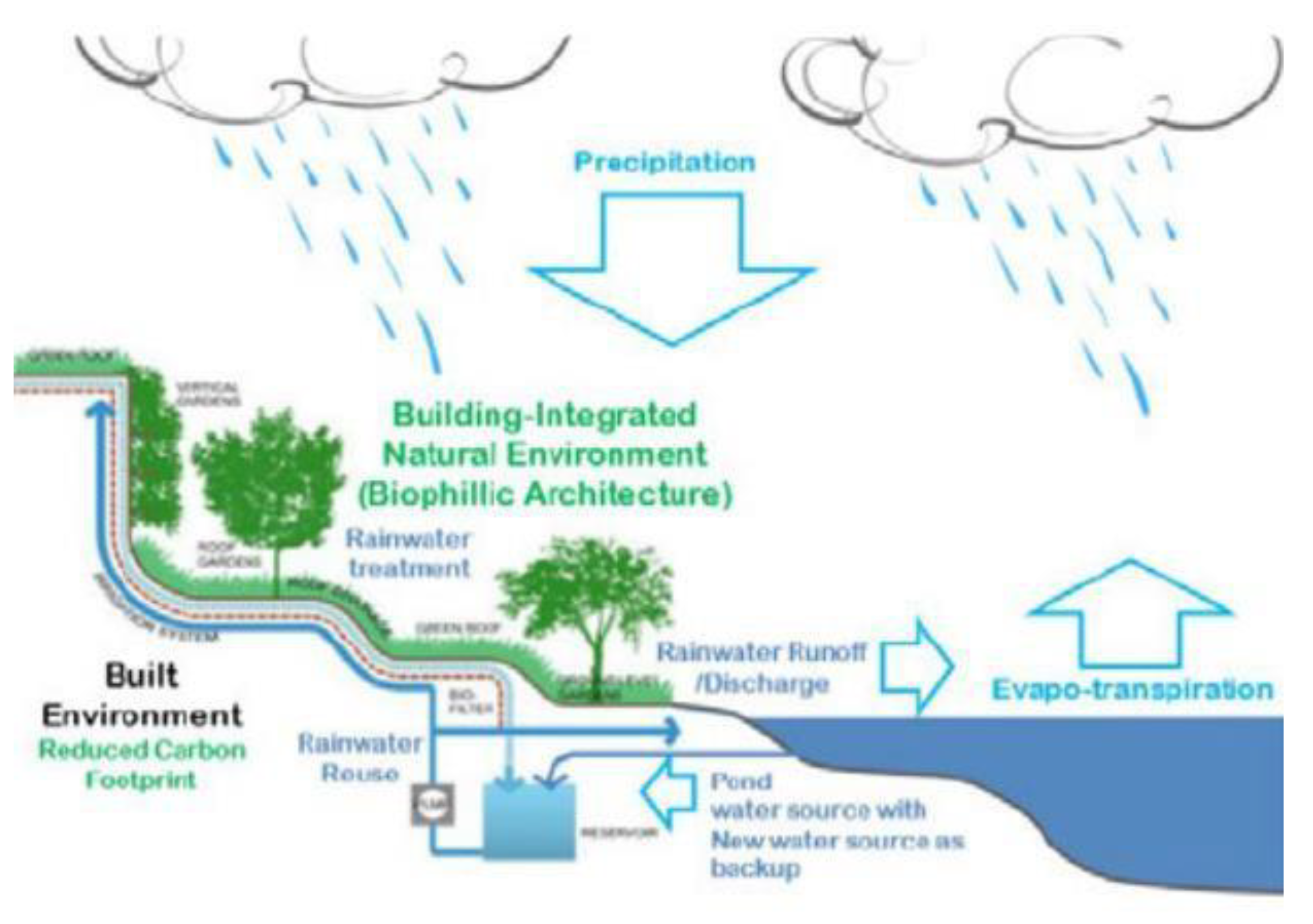

Figure 10.

Diagram of the building’s irrigation system,thus making the building a part of the larger ecosystem.2012,by CPG Consultants from Tan Shao Yen’s dissertation.

Figure 10.

Diagram of the building’s irrigation system,thus making the building a part of the larger ecosystem.2012,by CPG Consultants from Tan Shao Yen’s dissertation.

3.6.2. Parkwood Institute: Mental Health Care Building

Location: Ontario, London, Canada Architects/ designers: Parkin Architects Date of completion: 2014.

Figure 11.

Parkwood Institute: Mental Health Care Building.

Figure 11.

Parkwood Institute: Mental Health Care Building.

The addition of the Mental Health Care Building at Parkwood Institute aimed to merge physical and mental health care services while emphasizing community accessibility and combatting stigma. Designed by Parkin architects, the facility prioritizes treating severe mental illness and preparing individuals for reintegration into society.

Structured around “The House,” “The Neighborhood,” and “The Downtown” concepts, the design encourages community integration and personal growth. The building features light wells and therapeutic courtyards to maximize natural light, ventilation, and connection with nature.

Locally sourced and recycled materials were used to minimize the ecological footprint and create a homely atmosphere. Biophilic design principles were integrated, providing visual interaction with nature through glazed facades and natural materials to promote mental well-being.

Efforts to reduce the building’s environmental impact include water and energy conservation measures, passive design strategies, and a regulated air ventilation system. Overall, the facility’s layout maximizes natural light and ventilation to create a healing environment within familiar settings.

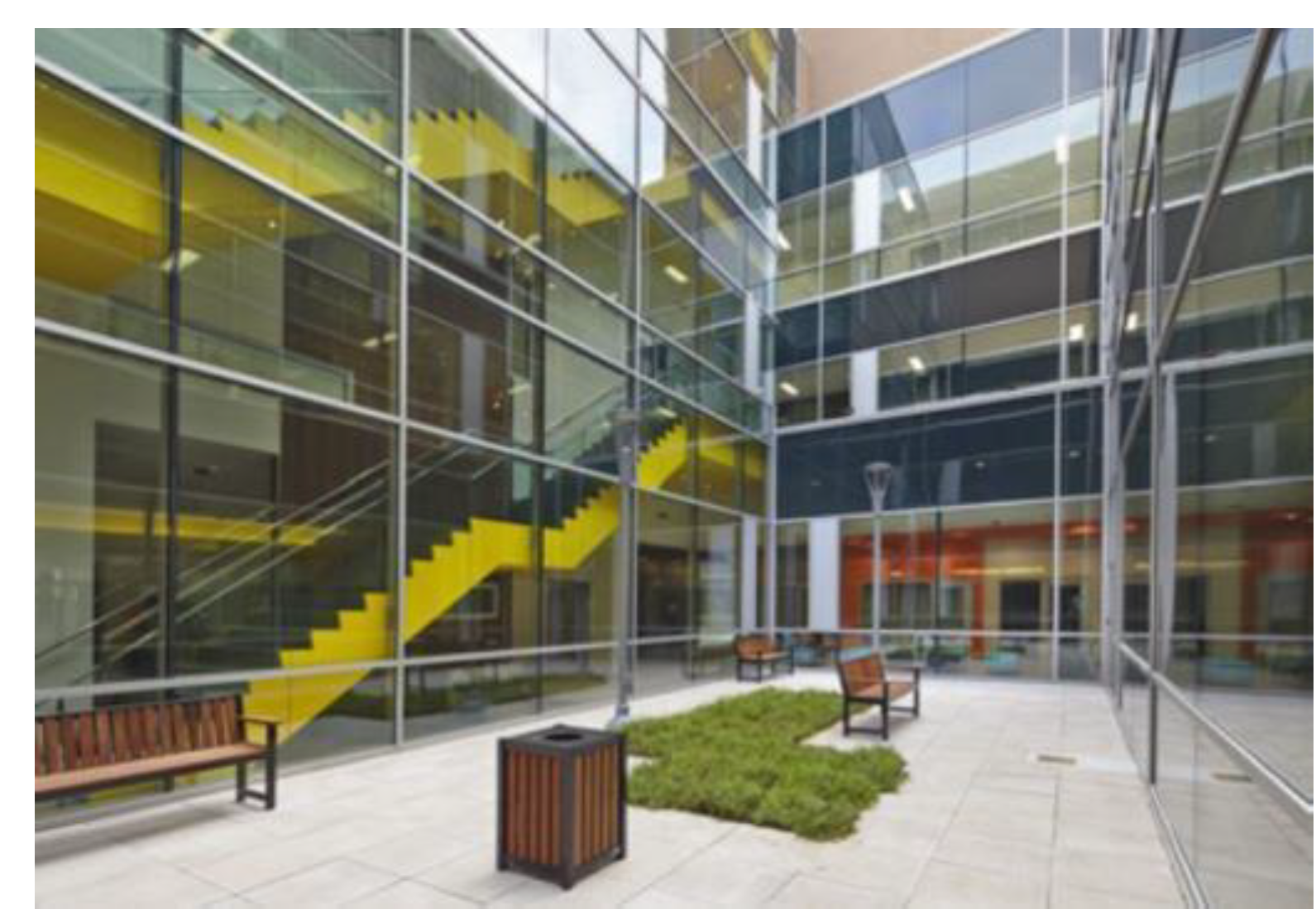

Figure 12.

Image illustrating the inclusion of the therapeutic courtyard space. 2014, By Parkin architects.

Figure 12.

Image illustrating the inclusion of the therapeutic courtyard space. 2014, By Parkin architects.

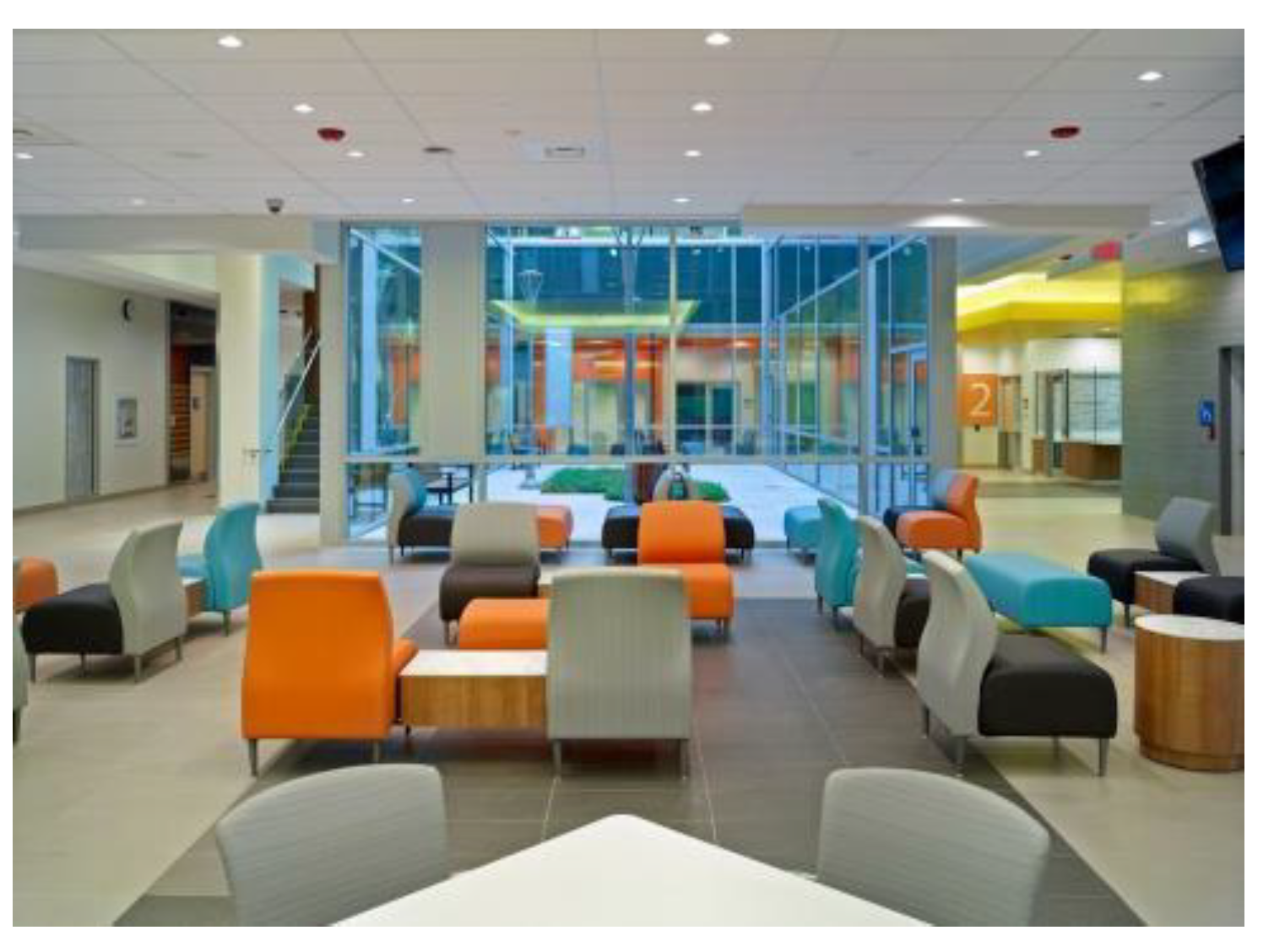

Figure 13.

Image portraying the visual connection between the interior and exterior. 2014, By Parkin 3.

Figure 13.

Image portraying the visual connection between the interior and exterior. 2014, By Parkin 3.

4. Conclusions

Incorporating natural and artificial light in architectural design is crucial for creating healing environments that promote mental and physical well-being. The integration of therapeutic architecture principles, such as Biophilia and Phenomenology, emphasizes the importance of connecting individuals with nature through architectural elements like natural lighting, ventilation, and sound. This connection induces positive emotional changes and contributes to stress reduction, ultimately aiding in the healing process.

The holistic design process considers both the benefits and drawbacks of natural and artificial light to optimize lighting solutions for specific projects. Studies have demonstrated that proper lighting design, including the use of both natural and artificial light, can alleviate symptoms of depression and improve patient outcomes in healthcare settings. Furthermore, integrating daylighting strategies in architecture not only minimizes environmental impacts but also creates healthier and more comfortable indoor environments for occupant

Color therapy, an alternative remedy that utilizes color and light to balance the body’s energy centers, has been recognized for its potential to promote mental and physical health. Its holistic approach to treatment is gaining attention for its positive effects on mood and overall well-being.

In conclusion, the integration of natural and artificial light, and color therapy, plays a significant role in enhancing the healing quality of healthcare spaces. Future research should further explore building techniques that optimize the benefits of natural light and investigate the therapeutic potential of color therapy in architectural design. By prioritizing these elements in architectural practice, designers can create environments that support the holistic well-being of individuals and contribute to improved health outcomes.

References

- (s.f.). Obtenido de ameridisability. Available online: https://www.ameridisability.com/how-color-therapy- benefits-people-with-disabilities/.

- Dr Amrapali Mahadev Jogdand, D. A. Dr Amrapali Mahadev Jogdand, D. A. (2022). The basic idea of colour therapy. Color therapy in mental health and well-being, 7.

- Husein Ali Husein, S. S. (2020). DAYLIGHT, HUMAN BODY, AND HEALTH. IMPACTS OF DAYLIGHT ON IMPROVING HEALING , 10.

- Kathleen Connellan, P., Mads Gaardboe, M., Damien Riggs, P. ,., Reinschmidt, A., & Mustillo, a.

- L. (2013). GARDENS. Stressed Spaces:Mental Health and ArchitecturE, 44. Stressed Spaces:Mental Health and ArchitecturE.

- Mahabir, S. (2019). INTRODUCTION. “Using a therapeutic architecture to re-conceptualize the design of mental health, 146.

- ray, k. d. (2023). background note. the foundation and good practices around halfway homes in india : discussion paper , 15.

- t.kohl, N. (2020). artificial lighting. The Influence of Light in the Built Envir The Influence of Light in the Built Environment t onment to Improve Mental e Mental, 110.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).