Submitted:

20 February 2024

Posted:

22 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Equilibrium and Entropy Generation: Initial and Final Conditions

1.2. Local Equilibrium

1.3. States, Paths and Path Integrals

- Thermodynamics often involves changes in variables between two states. Variables include a set of the independent thermodynamic state variables Z chosen and measured for a particular system, and state dependent system properties which are functions of the states of Z. The Z characterize a system’s thermodynamic state and can include temperature pressure P, and number of moles N, among others. Changes in system properties such as energy E, entropy S, temperature T and use the exact differential d; are path independent wherein changes in properties over an irreversible path (irr) are identical to changes in properties over a reversible path (rev), e.g., dE = dEirr = dErev; and the path integral depends only on the property values at the beginning and end states (o and f). This is the thermodynamic state principle.

- Path-dependent variables such as work W, heat transfer entropy generation and depend on what occurs along the path between states o and f, and use the inexact differential such that must be accumulated over all instants of time t along the (assumed known) transformation path between times and . The path-dependent parameters will depend on a set of variables = {Z} assumed to be time dependent, observable, and measurable. The Z characterize the thermodynamic state, whereas the characterize any active irreversible dissipative processes. Via a suitable numerical integration such as the trapezoid rule, with the = { Z(t), } measured as points = {Z, suitably spaced at time instants < in accord with the sampling theorem [16], the increments can be accumulated into the path integral .

- Exact differentials , state functions of the independent state variables Z(t), if intractable, can be numerically integrated over the (ideal) reversible path per methods of the prior paragraph. The reversible path must transit states o to f in quasi-equilibrium and be continuous and maximally smooth over time, which can be approximated by linear functions with slope determined by the end states, for example, if , components of Z(t) with slope where and must be measured or known at the beginning and final times and . With this, the path integral , where sum index Z denotes a sum over all the components of Z, and dE/dZ must be evaluated at each time instant < along the reversible path.

- For reversible processes with initial and final states and , satisfies the reversible path approximations of item 3.

- An irreversible path (irr) through the thermodynamic state space enclosing = {Z} defined in item 2 includes nonzero . A reversible path (rev) in the reversible subspace {Z} of [17] involves only the thermodynamic states Z, not the . The projection of the set of points = {Z, that comprise an irreversible path onto the reversible subspace is the set of points {Z [17].

2. Irreversible Thermodynamics and Entropy Generation

2.1. Combining Internal Energy and Entropy Balances

2.2. Entropy Generation of Various System Classes Via Thermodynamic Potentials

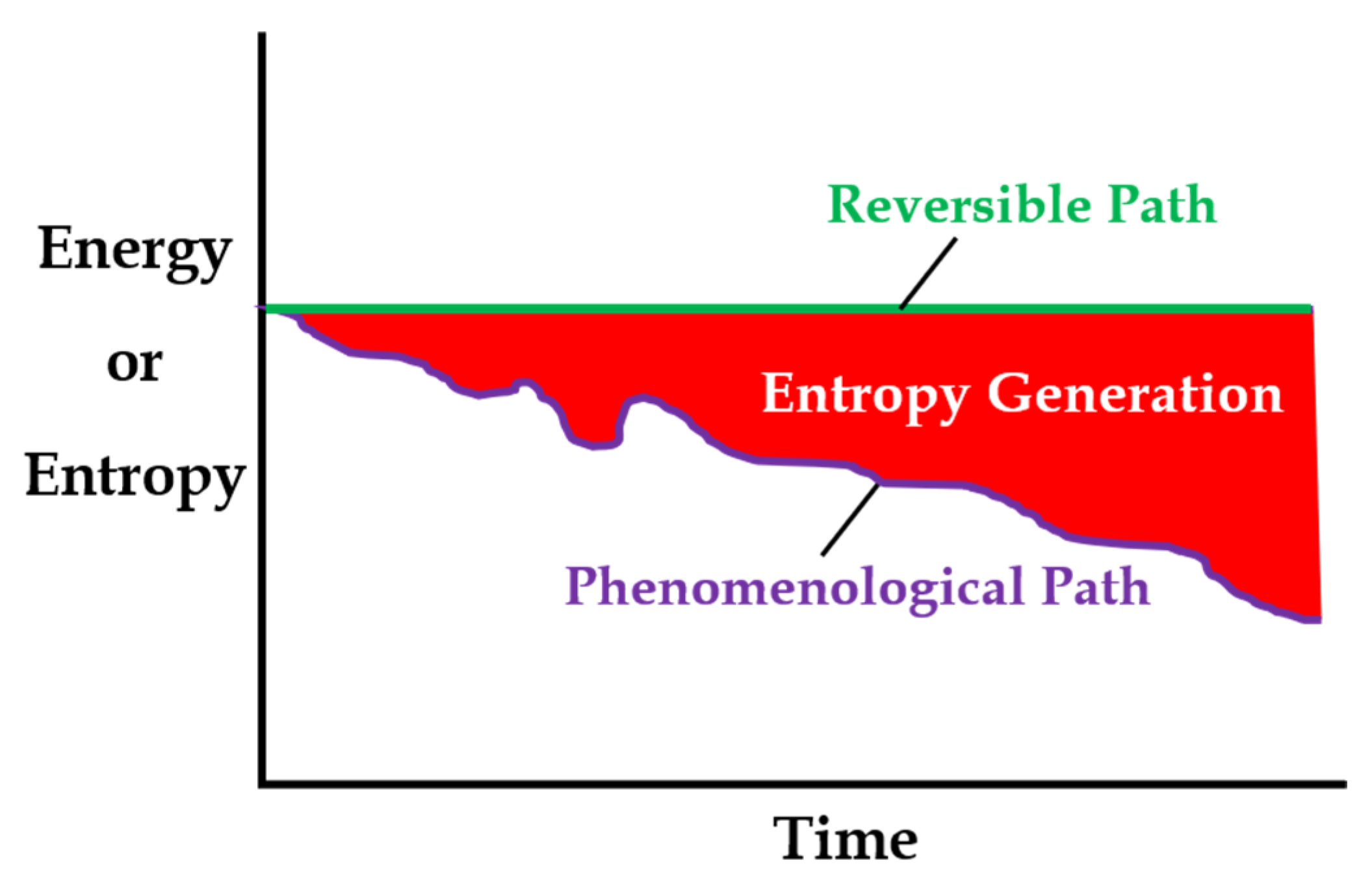

- : evaluated via the expressions of the middle equalities of Equations (5) and (8) at points over the irreversible phenomenological path defined in items 2 and 5 of Section 1.3.

- : evaluated as an exact differential over a reversible path between the beginning and final values of the irreversible path for , as discussed in list items 3, 4 and 5 of Section 1.3. Here the independent states in the parentheses of Equations (5) and (8) are linear in time, as per items 3 and 4 of Section 1.3.

2.3. Phenomenological Entropy Generation Theorem

2.4. Phenomenological Entropy Generation Functions for Various System Classes

2.4.1. Thermal Systems: Internal Energy and Enthalpy

2.4.2. Boundary-Loaded (Work-Capable) Systems: Helmholtz Potential

2.4.3. Internally Reactive Systems and Energy Storage Systems: Gibbs Potential

2.5. Generalized Material Properties, Entropy Content S, Internal Free Energy Dissipation “–SdT”

2.6. Stress vs Strength Sign Conventions

2.7. Helmholtz-Gibbs Coupling

2.8. Rates

2.9. Open Systems: Pumps, Compressors, Fuel Cells, Etc.

3. Evaluating Total Entropy Generation and Path Integrals

4. Sample (Phenomenological) Entropy Generation Calculations

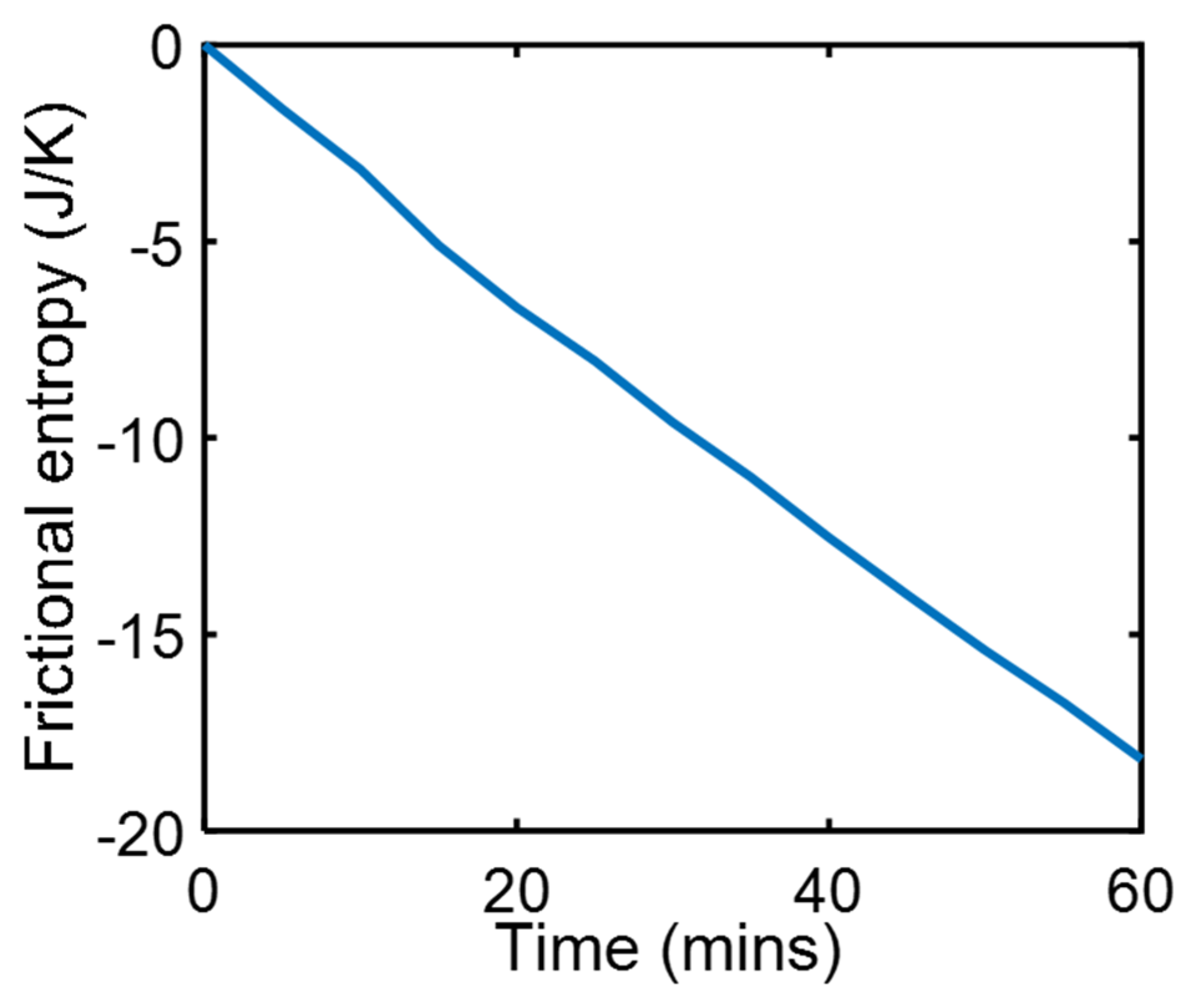

4.1. Friction Sliding of Copper Against Steel at Steady Speed—(Steady State)

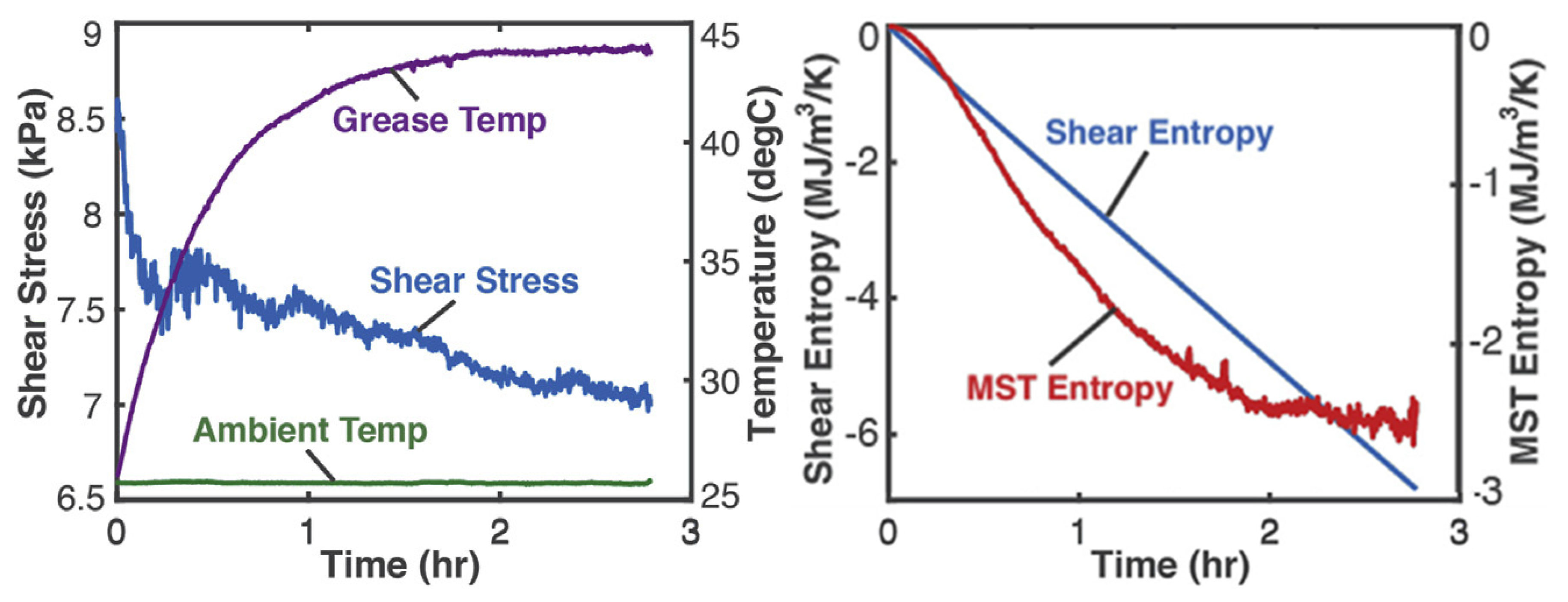

4.2. Mechanical Shearing of Grease—Shear Stress and Shear Strain (Helmholtz Potential)

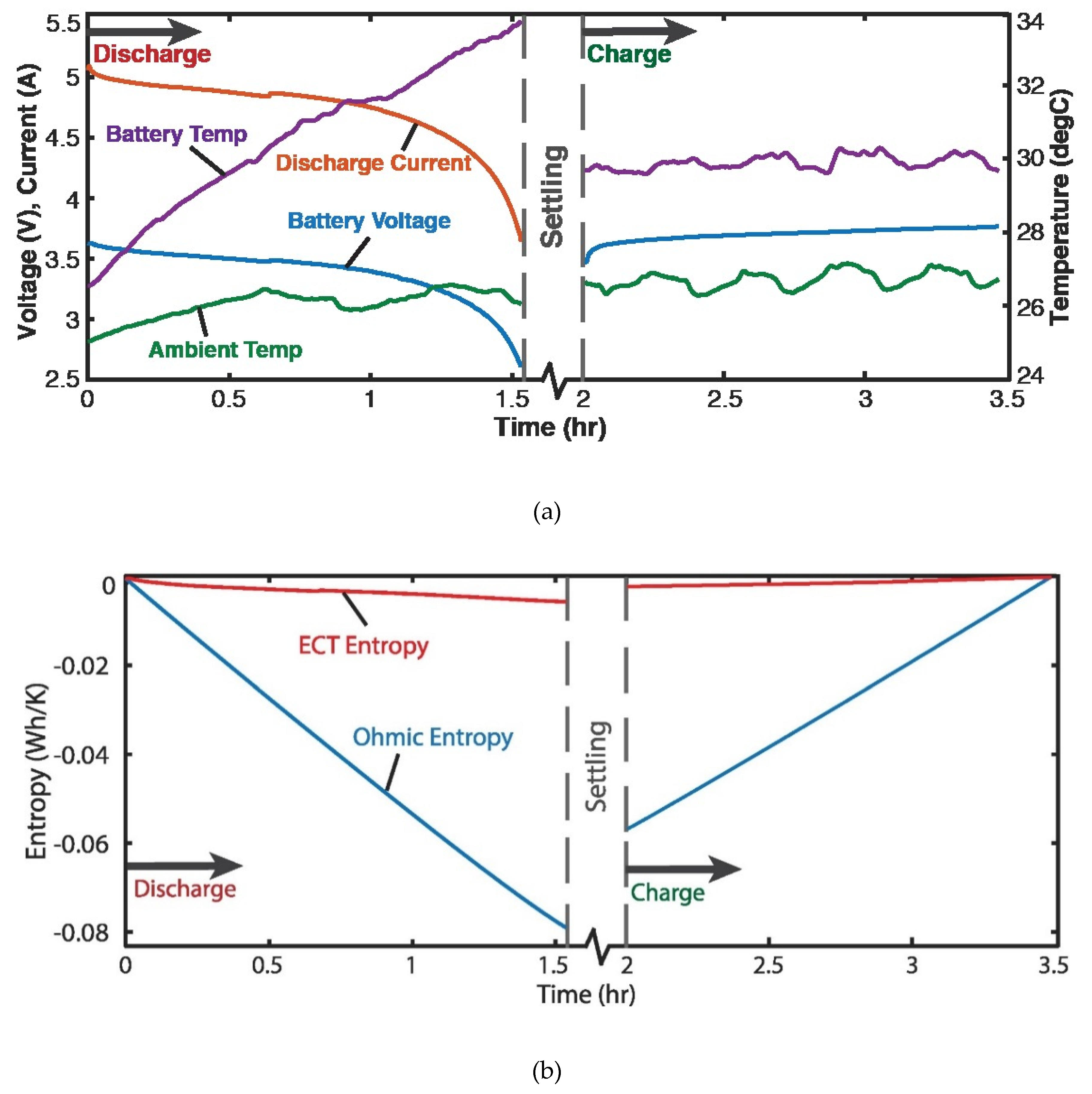

4.3. Discharge of Lithium-Ion Battery—Voltage and Charge (Helmholtz-Gibbs Coupling)

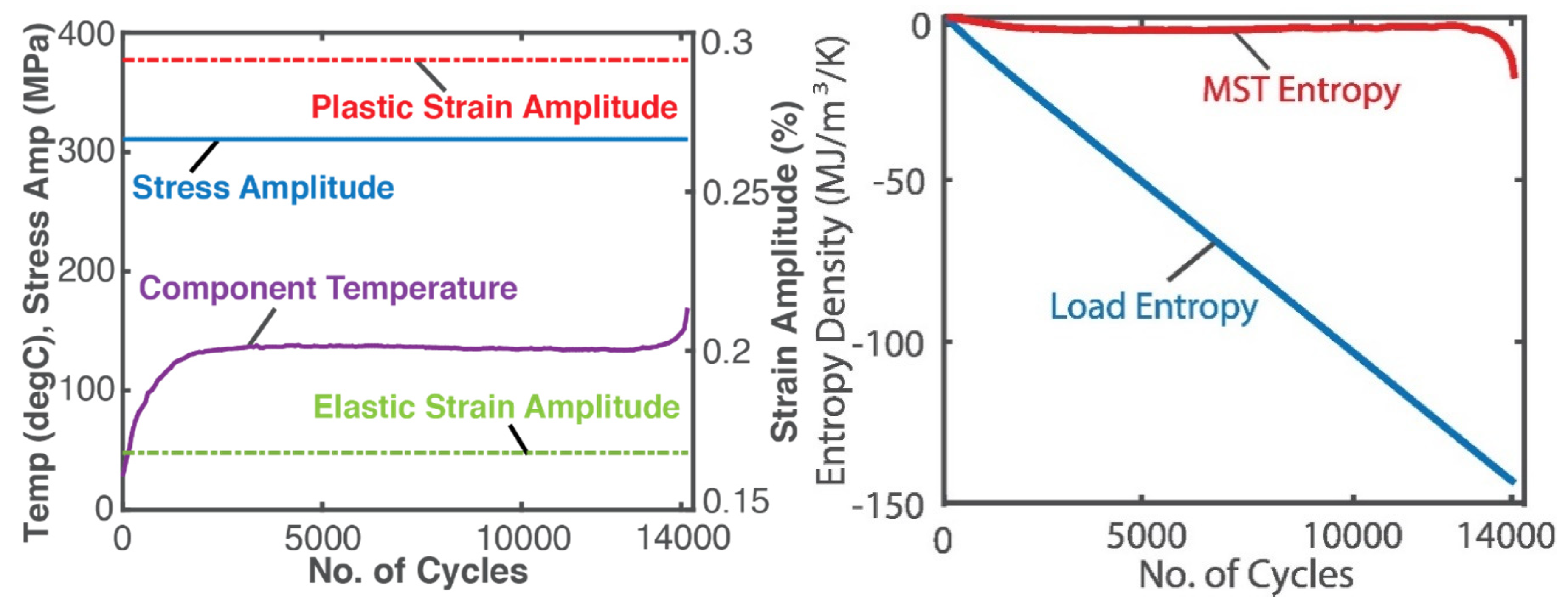

4.4. Fatigue of Metals—Stress and Strain (Helmholtz Potential)

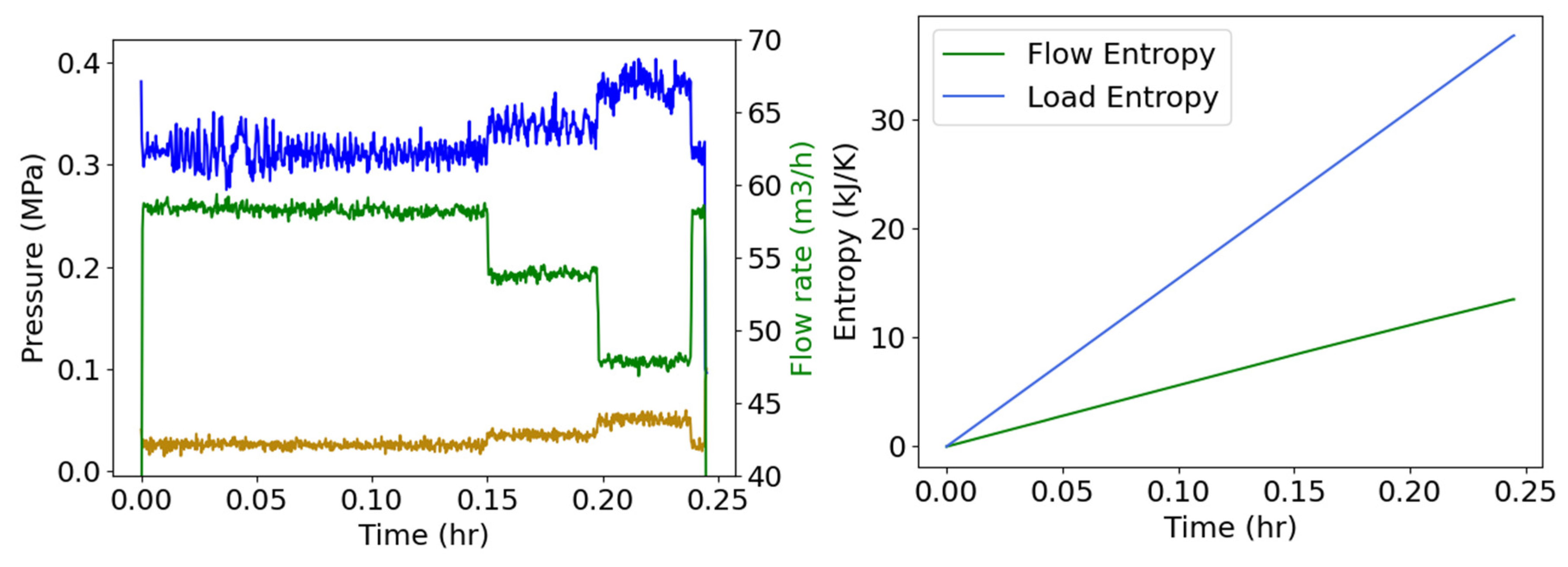

4.5. Pump Flow—Pressure and Flow Rate (Internal Energy)

5. Discussion

5.1. Phenomenology

5.2. Steady vs Unsteady Systems: Minimum Entropy Generation (MEG) vs MicroStructuroThermal (MST) Entropy

5.3. Dissipation Factor and Entropic Efficiency

5.4. Thermal vs Non-Thermal Systems – Internal Energy and Enthalpy vs the Free Energies

6. Summary and Conclusions

- a combination of the thermodynamic potentials and the irreversible form of the TdS equation yields the irreversible Massieu functions;

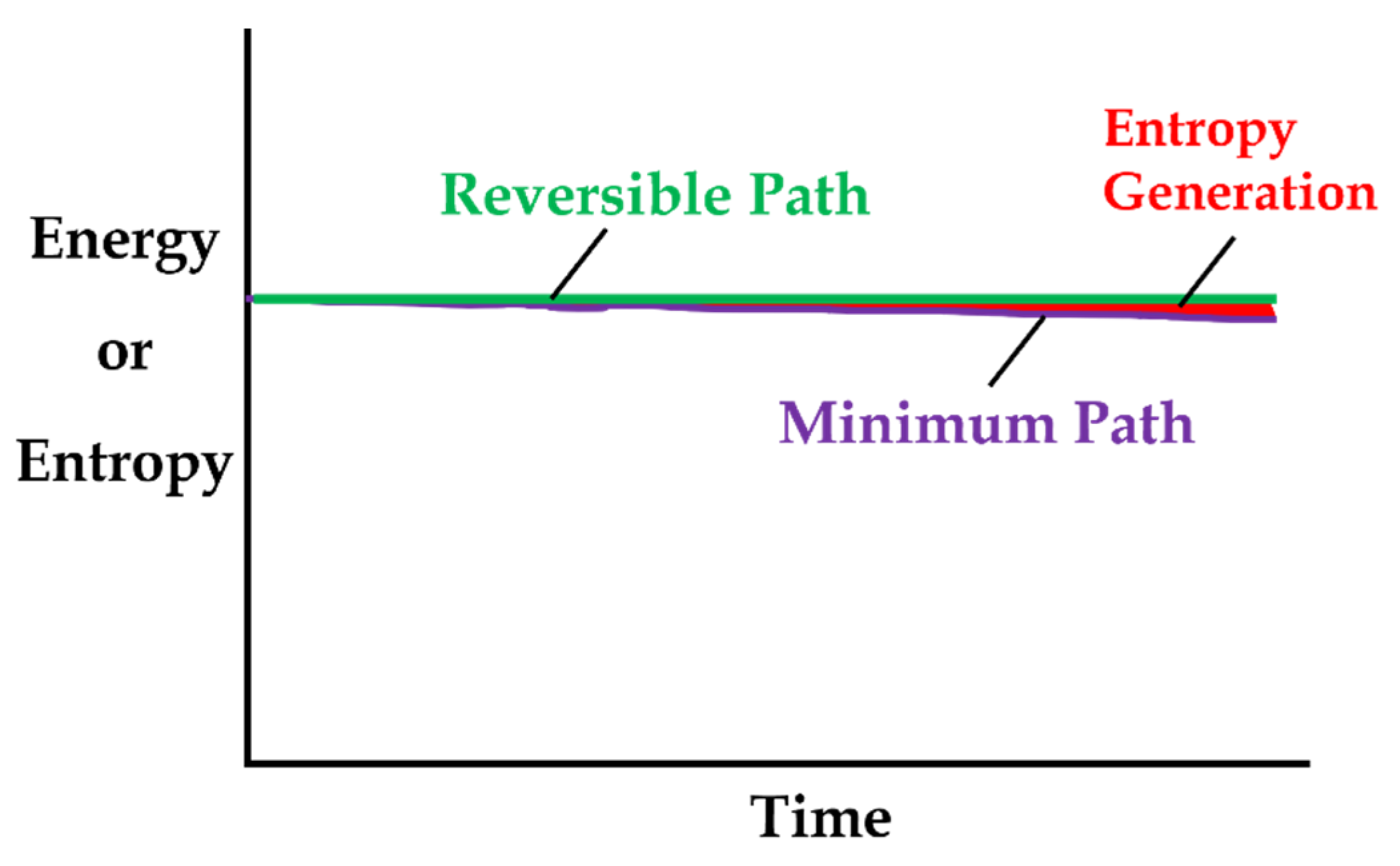

- steady-state systems generate entropy at a minimum rate, which for a boundary-loaded, internally reactive open system is the sum of boundary work/load entropy and compositional change entropy rates;

- for unsteady non-thermal systems, a microstructurothermal MST entropy is included to characterize the accompanying instantaneous transients during system transformation;

- phenomenological entropy generation is the sum of boundary work/load entropy , compositional change entropy and microstructurothermal MST entropy (ElectroChemicoThermal ECT entropy for electrochemical systems);

- entropy generation is the difference between phenomenological and reversible entropies at every instant, named the Phenomenological Entropy Generation (PEG) Theorem;

- entropy generation is always non-negative in accordance with the second law, while its constituent terms and are directional, negative for a loaded system and positive for an energized system. This implies during load application/work output or active species decomposition, and during energization/work input or active species formation, in accordance with experience and thermodynamic laws. In plain words, actual work obtained from a real system is always less than the theoretical maximum/reversible work, and actual work added to a real system is always more than the minimum/reversible work. (Modulus signs indicate magnitudes only).

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Nomenclature | Name | Unit |

|

B F G I m n’ M N, Nk P q Q R |

Helmholtz free energy magnetic field Heat capacity Faraday’s constant Gibbs free energy discharge/charge current or rate mass number of charge species magnetic dipole moment number of moles of substance pressure chargeheat gas constant |

J T J/K C/mol J A kg J/T mol Pa Ah J J/mol·K |

| S | entropy or entropy content | J/K (Wh/K) |

| entropy generation function | J/K (Wh/K) | |

|

S’ t T U v W Z |

entropy generation or production time temperature internal energy voltage volume work thermodynamic state variable |

J/K (Wh/K) sec°C or K J V m3 J |

| Symbols | ||

|

μ ζ ρ |

chemical potential phenomenological variable density |

|

| Subscripts & acronyms | ||

|

Ω 0 c d e f ECT, VT MST rev irr phen DEG PEG NLGI |

Ohmic initial specific heat capacity diffusion flow final Electro-Chemico-Thermal Micro-Structuro-Thermal reversible irreversible phenomenological Degradation-Entropy Generation Phenomenological Entropy Generation National Lubricating Grease Institute |

|

Appendix A

| Category | Gibbs-Based | Helmholtz-Based |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal | Constant-Force Heat Capacity |

Constant-Displacement Heat Capacity |

| Thermo-mechanical | Thermal Displacement Coefficient | Thermal Force Coefficient |

| E’ | ||

| Mechanical | Isothermal Loadability | Load Modulus |

| Chemical | Isothermal Constant-Force Chemical Resistance |

Isothermal Constant-Displacement Chemical Resistance |

| Thermo-chemical | Constant- Force Thermal Decay Coefficient | Constant-Displacement Thermal Decay Coefficient |

| Property | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Heat Capacity | Material’s ability to withstand heat without an increase in temperature. |

| Thermal Displacement/Force Coefficient | Impact of temperature on displacement/force. Physical response to temperature change. |

| Load Modulus | Physical response to non-thermal load. |

| Chemical Resistance | Resistance to chemical conversion of reactive species. |

| Thermal Decay Coefficient | Chemical response to temperature change. |

| 1 | The change in the control volume must equal the amounts in and out. |

| 2 | Via Faraday’s electrolysis law, see paragraph after Equation (16). |

References

- L. Onsager, Irreversible Processes, Phys. Rev. (1931) 183–196. [CrossRef]

- I. Prigogine, Introduction to Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes, Charles C Thomas, 1955.

- S.R. de Groot, P. Mazur, Non-equilibrium thermodynamics, Dover Publications Inc, New York. 2011.

- J. Osara, M. Bryant, A Thermodynamic Model for Lithium-Ion Battery Degradation: Application of the Degradation-Entropy Generation Theorem, Inventions. 4 (2019) 23. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Osara, M.D. Bryant, Performance and degradation characterization of electrochemical power sources using thermodynamics, Electrochim. Acta. 365 (2021) 137337. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Osara, Thermodynamics of Degradation, The University of Texas at Austin, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Osara, M.D. Bryant, Thermodynamics of grease degradation, Tribol. Int. 137 (2019) 433–445. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Osara, M.D. Bryant, Thermodynamics of fatigue: Degradation-entropy generation methodology for system and process characterization and failure analysis, Entropy. 21 (2019). [CrossRef]

- J.A. Osara, M.D. Bryant, A temperature-only system degradation analysis based on thermal entropy and the degradation-entropy generation methodology, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 158 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J.A. Osara, M.D. Bryant, Thermodynamics of Lead-Acid Battery Degradation : Application of the Degradation-Entropy Generation Methodology, J. Electrochem. Soc. 166 (2019). [CrossRef]

- J.A. Osara, M.D. Bryant, Evaluating Degradation Coefficients from Existing System Models, Appl. Mech. 2 (2021) 159–173. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Osara, P.M. Lugt, M.D. Bryant, M.M. Khonsari, Thermodynamic Characterization of Grease Oxidation Stability via Pressure Differential Scanning Calorimetry, Submiss. (n.d.).

- M.D. Bryant, M.M. Khonsari, F.F. Ling, On the thermodynamics of degradation, Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. (2008) 2001–2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Kondepudi, I. Prigogine, Modern Thermodynamics: From Heat Engines to Dissipative Structures, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 1998.

- S.R. de Groot, Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes, North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1951. [CrossRef]

- Taub, H. and D. L. Schilling, Principles of Communication Systems, McGraw-Hill, 1971.

- W. Muschik, Fundamentals of Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics, in book Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics with Applications to Solids, ed. W. Muschik, (1993),1-67.

- H.B. Callen, Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 1985.

- J.A. Osara, Thermodynamics of manufacturing processes—the workpiece and the machinery, Inventions. 4 (2019). [CrossRef]

- R. Bove, S. Ubertini, eds., Modeling Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Methods, Procedures and Techniques, Spinger. 2008.

- J.W. Morris, The thermodynamics of solids Chapter 16 : Elastic Solids, Notes. (2007) 366–411.

- R. Balian, François Massieu and the thermodynamic potentials, Comptes Rendus Phys. 18 (2017) 526–530. [CrossRef]

- A. Bejan, Advanced Engineering Thermodynamics, Third, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2006. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Osara, S. Chatra, P.M. Lugt, Grease Material Properties from First Principles Thermodynamics. Lubrication Science (2023). [CrossRef]

- K.L. Doelling, F.F. Ling, M.D. Bryant, and B.P. Heilman, An Experimental Study on the Correlation between Wear and Entropy Flow in Machinery Components, J. Appl. Phys., Vol. 88, pp. 2999-3003, 2000.

- M.D. Burghardt, J.A. Harbach, Engineering Thermodynamics, 4th ed., HarperCollinsCollegePublishers, 1993.

- A. Bejan, The Method of Entropy Generation Minimization, Energy Environ. (1990) 11–22.

- R. Pal, Demystification of the Gouy-Stodola theorem of thermodynamics for closed systems, Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 45 (2017) 142–153. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Moran, H.N. Shapiro, Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, 5th ed., Wiley, 2004.

- Y.A. Çengel, M.A. Boles, Thermodynamics - an engineering approach, McGraw-Hill Education, 2015.

- M. Naderi, M.M. Khonsari, An experimental approach to low-cycle fatigue damage based on thermodynamic entropy, Int. J. Solids Struct. 47 (2010) 875–880. [CrossRef]

- M. Amiri, M. Naderi, M.M. Khonsari, An Experimental Approach to Evaluate the Critical Damage, Int. J. Damage Mech. 20 (2011) 89–112. [CrossRef]

- J. Morrow, Cyclic Plastic Strain Energy and Fatigue of Metals, ASTM Int. (1965).

- J. Rincon, J.A. Osara, M.D. Bryant, B. Fernandez, Shannon’s machine capacity & degradation-entropy generation methodologies for failure detection: practical applications to motor-pump systems. Turbomachinery & Pump Symposia, Houston, TX. 2021.

- G. Nicolis, I. Prigogine, Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems, John Wiley & Sons Inc, New York, 1977.

| Category | Example | |

|---|---|---|

|

Open Internal Energy |

Equation (10a) (for a non-reacting system) |

Compressor (with temperature rise and boundary work): (Rate form in Equation (19)) |

|

Thermal Enthalpy |

Equation (10b) (for a closed system) |

Combustion systems without boundary work: |

|

Boundary-Loaded Helmholtz potential |

Equation (10c) |

Mechanical loading, e.g., shearing without oxidation: |

|

Reactive/Energy Gibbs potential |

Equation (10d) |

Electrochemical energy systems, e.g., batteries: Via Gibbs-Helmholtz coupling: Via Gibbs-Duhem formulation: |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).