Submitted:

19 February 2024

Posted:

20 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

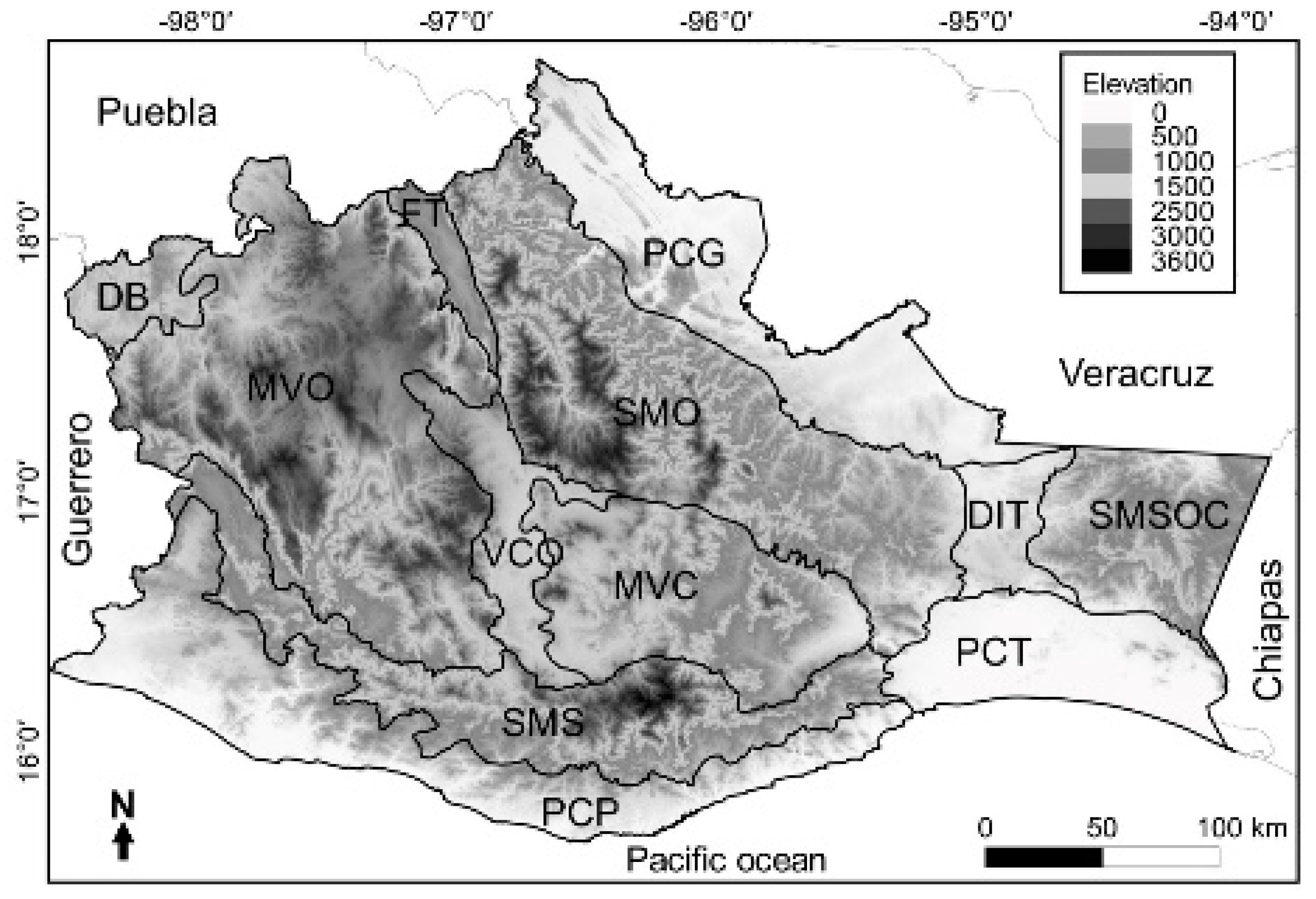

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Species Richness and Endemism

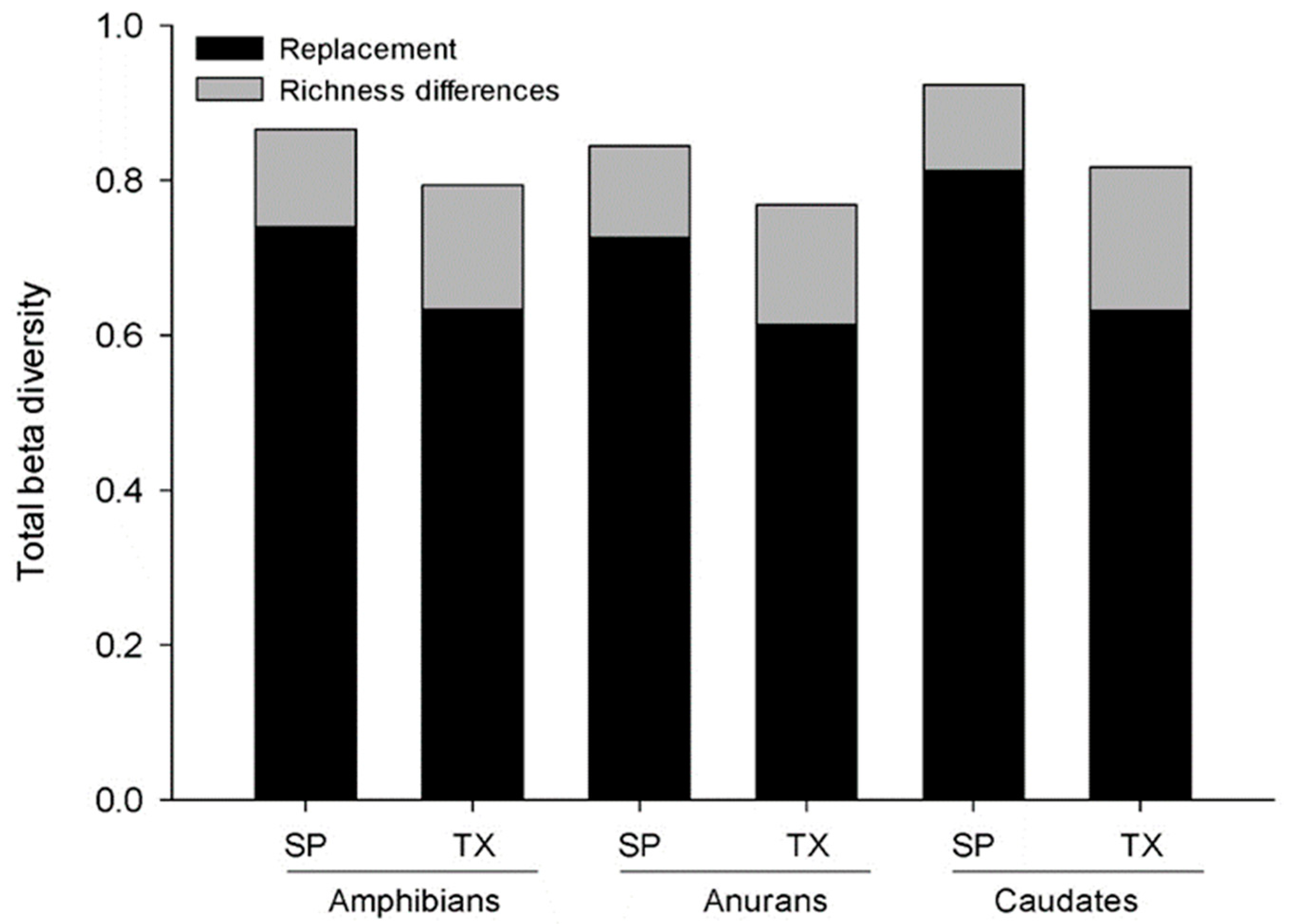

3.2. Total Beta Diversity of Amphibian Species at the State Level

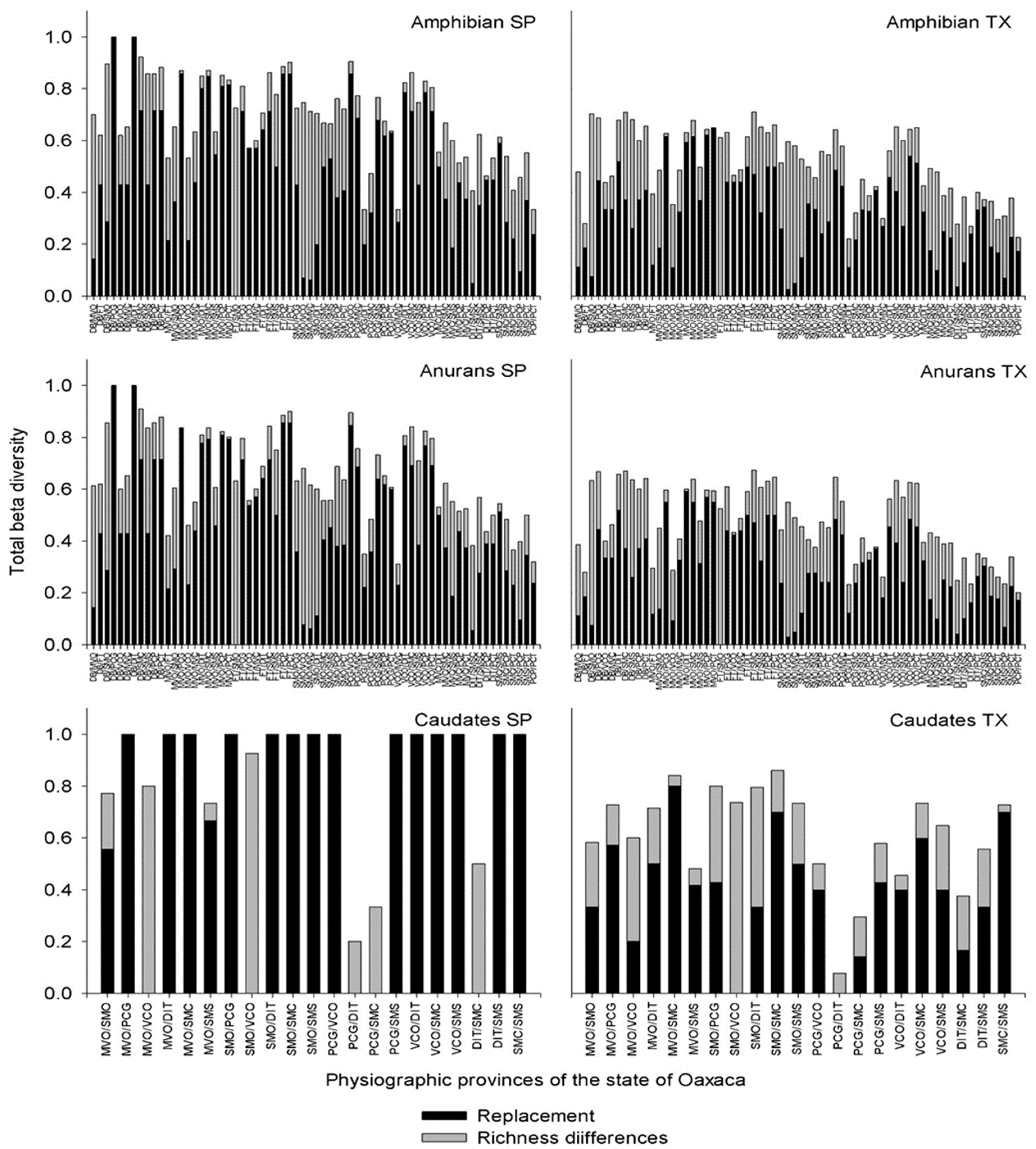

3.3. Beta Diversity of Amphibians between Pairs of Physiographic Subprovinces

3.4. Determination of Beta Diversity of Species and Higher Taxa

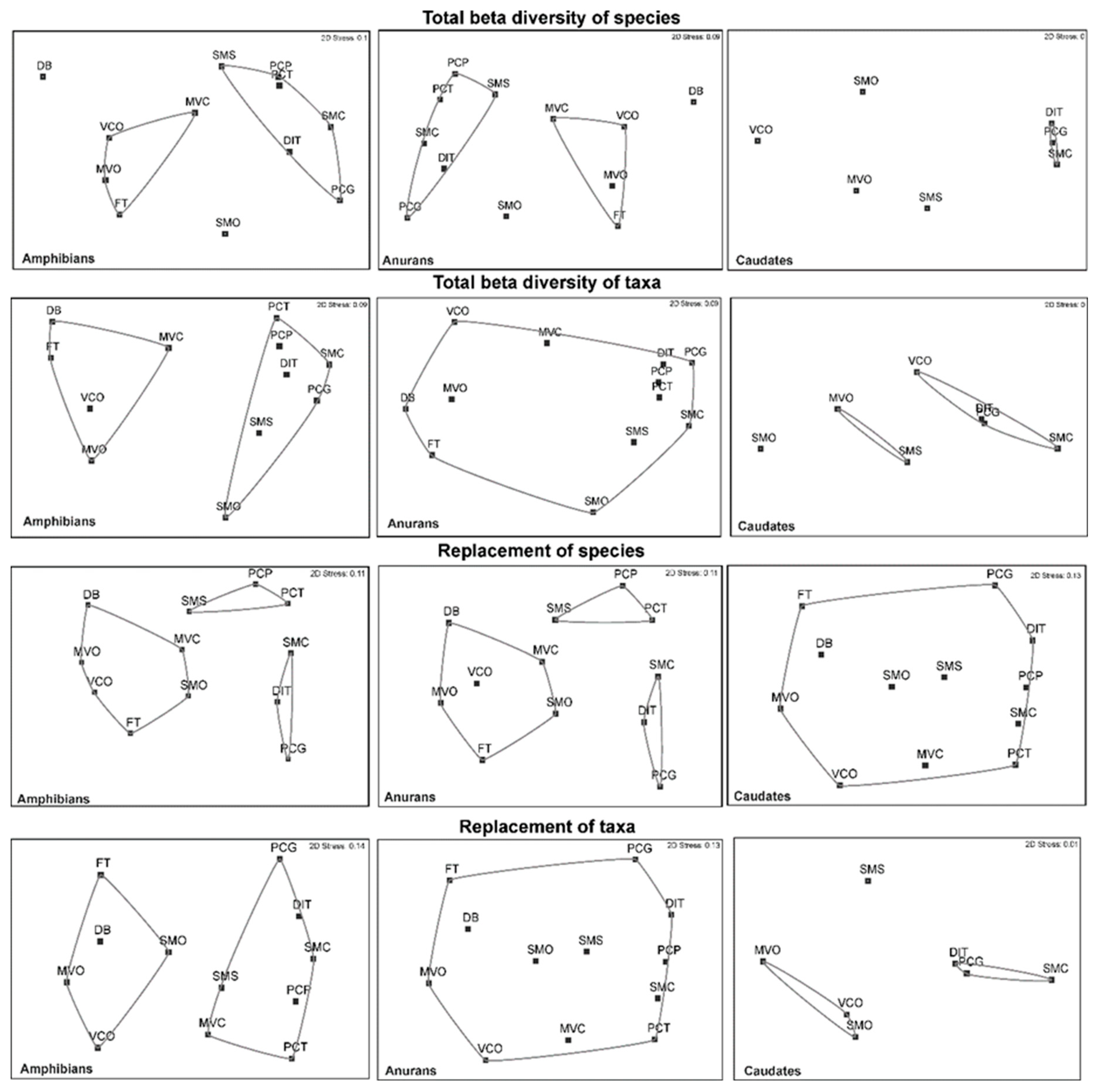

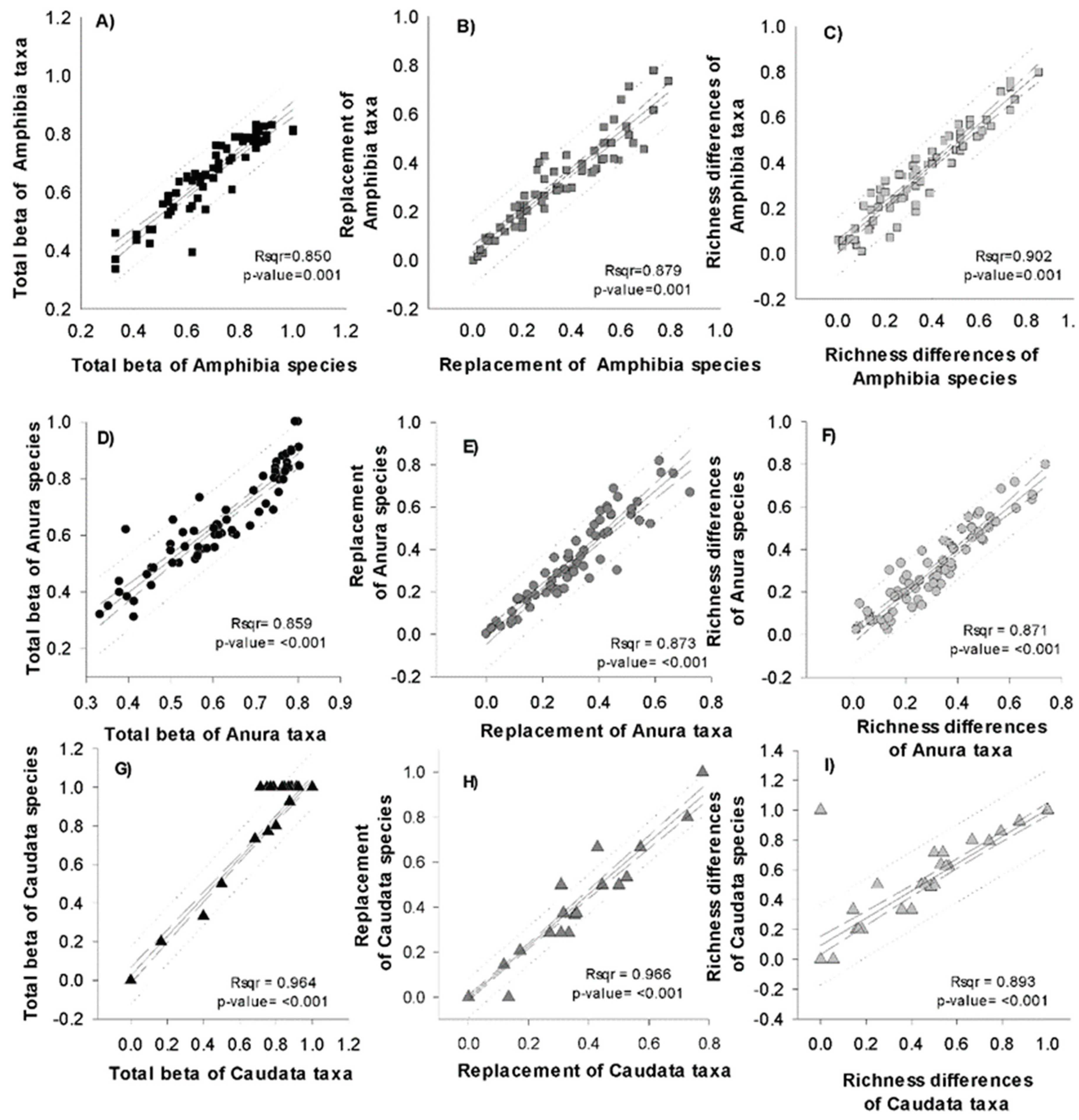

3.5. Relationship between Beta Diversity of Species and Higher Taxa

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parra-Olea, G.; Flores-Villela., O.; Mendoza-Almeralla, C. Biodiversity of amphibians in Mexico. Rev Mex Biodivers 2014, 85, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Silva, V., Johnson, J.D., Wilson, D.; García-Padilla, E. The herpetofauna of Oaxaca, Mexico: composition, physiographic distribution, and conservation status. Mesoam Herpetol. 2015;2(1):6–62.

- Wake, D.; Vredenburg, V.T. Are we in the midst of the sixth mass extinction? A view from the world of amphibians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;115(1):11466–11473. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Bañuelos, P.; Rovito, S.M., Pineda, E. Representation of Threatened Biodiversity in Protected Areas and Identification of Complementary Areas for Their Conservation: Plethodontid Salamanders in Mexico. Trop Conserv Sci. 2019; 12:1-15. [CrossRef]

- Lips, K.R.; Burrowes, P.A.; Mendelson, J.R; Parra Olea, G. Amphibian population declines in latin America: a synthesis. Biotropica. 2005, 37(2):222–226. [CrossRef]

- Koleff, P.; Soberón, J.; Arita, H.; Dávila, P.; Flores-Villela, O.; Halffter, G.; Lira-Noriega, A.; Moreno, C.E.; Moreno, E.; Munguía, M.; et al. Patrones de diversidad espacial en grupos selectos de especies. In Capital natural de México, vol. I: Conocimiento actual de la biodiversidad. Ciudad de México, México, Conabio; 2008. p. 323-364.

- Ochoa-Ochoa, L.M.; Munguía, M.; Lira-Noriega, A.; Sánchez-Cordero, V.; Flores-Villela, O.; Navarro-Sigüenza, A.; Rodríguez, P. Spatial scale and β-diversity of terrestrial vertebrates in Mexico. Rev Mex Biodivers. 2014;85(3):918–930. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, P.; Ochoa-Ochoa, L.M.; Munguía, M.; Sánchez-Cordero, V.; Navarro-Sigüenza, A.; Flores-Villela, O.; Nakamura, M. Environmental heterogeneity explains coarse-scale β-diversity of terrestrial vertebrates in Mexico. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):1–13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselga, A.; Gómez-Rodríguez, C.; Lobo, J.M. Historical legacies in world amphibian diversity revealed by the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e32341. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2010;19(1):134–143. [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. The relationship between species replacement, dissimilarity derived from nestedness, and nestedness. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2012;21(12):1223–1232. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.C.; Cardoso, P.; Gomes, P. Determining the relative roles of species replacement and species richness differences in generating beta-diversity patterns. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2012; 21(7):760–771. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.C.; Cardoso, P.; Borges, P.A.V., Schmera, D.; Podani, J. Measuring fractions of beta diversity and their relationships to nestedness: a theoretical and empirical comparison of novel approaches. Oikos. 2013;122(6):825–834. [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A., Leprieur, F. Comparing methods to separate components of beta diversity. Methods Ecol Evol. 2015;6(9):1069–1079. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P., Rigal, F.; Carvalho, J.C. BAT - Biodiversity Assessment Tools, an R package for the measurement and estimation of alpha and beta taxon, phylogenetic and functional diversity. Methods Ecol Evol. 2015;6(2):232–236. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Computer software v4.03. ISBN 3-900051-07-0: URL http://www. R-project. org; 2018. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Bacaro, G.; Ricotta, C.; Mazzoleni, S. Measuring beta-diversity from taxonomic similarity. J Veg Sci. 2007;18(6):793–798. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. Primer: user manual/tutorial. Primer-E Ltd, Plymouth, UK. 2015.

- IUCN. 2019. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/summary-statistics (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- MacArthur, R.H., Wilson, E.O. The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 1967.

- Rosenzweig, M.L. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge University Press; United Kingdom. 1995.

- Gaston, K.J. Global Patterns in Biodiversity. Nature, 2000; 405:220–227. [CrossRef]

- Casas-Andreu, G. Anfibios y reptiles de las islas Marías y otras islas adyacentes de la costa de Nayarit, México. Aspectos sobre su biogeografía y conservación. An Inst Biol, Univ Nac Auton Mex, Zool, 1992;63(1):95–112.

- Calderón-Patrón, J.M. Biogeografía de islas: el caso de la herpetofauna mexicana. Tesis de Maestría. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. México. 2007.

- Bell, K.E.; Donnelly, M.A. Influence of forest fragmentation on community structure of frogs and lizards in northeastern Costa Rica. Conserv Biol. 2006;20(6):1750–1760. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Guzmán, E.; Reynoso, V.H. Amphibian and reptile communities of rainforest fragments: minimum patch size to support high richness and abundance. Biodiversity Conserv. 2012;21(12):3243–3265. [CrossRef]

- Russildi, G.; Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., Hernández-Ordóñez, O.; Pineda, E.; Reynoso, V.H. Species- and community-level responses to habitat spatial changes in fragmented rainforests: assessing compensatory dynamics in amphibians and reptiles. Biodiversity Conserv. 2016;25(2):375–392. [CrossRef]

- Vitt, L.J.; Caldwell, J.P. Herpetology: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles: Fourth Edition. Elsevier Inc, Norman, Oklahoma. 2014.

- Calderón-Patrón, J.M.; Moreno, C.E.; Pineda-López, R.; Sánchez-Rojas, G.; Zuria, I. Vertebrate dissimilarity due to turnover and richness differences in a highly beta-diverse region: The role of spatial grain size, dispersal ability and distance. PLoS ONE, 2014;8(12):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Patrón, J.M.; Goyenechea, I.; Ortiz-Pulido, R.; Castillo-Cerón, J.; Manríquez, N.; Ramírez-Bautista, A.; Rojas-Martínez, A.E.; Sánchez-Rojas, G.; Zuria, I.; Moreno, C.E. Beta diversity in a highly heterogeneous area: Disentangling species and taxonomic dissimilarity for terrestrial vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 2016;11(8):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Ramírez, C.M.; Aguilar-López, J.L.; Pineda, E. Protected natural areas and the conservation of amphibians in a highly transformed mountainous region in Mexico. Herpetol Conserv Biol, 2016;11(1):19–28.

- Aguilar-López, J.L.; Ortiz Lozada, L.; Pelayo-Martínez, J.; Mota-Vargas, C.; Alarcón-Villegas, L.E.; Demeneghi-Calatayud, A.P. Diversidad y conservación de anfibios y reptiles en un área protegida privada de una región altamente transformada en el sur de Veracruz, México. Acta Zool Mex (ns). 2020;36(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Patrón, J.M.; Moreno, C.E., Zuria, I. Diversidad beta: medio siglo de avances. Rev Mex Biodivers. 2012; 83:879-891. [CrossRef]

- Monroy-Gamboa, A.G.; Sánchez-Cordero, V.; Briones-Salas, M., Lira-Sadee, R.; Maass-Moreno, J.M. Representatividad de los tipos de vegetación en distintas iniciativas de conservación en Oaxaca, México. Bosque. 2015;36(2):199–210. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Toro, W.; Torres-Miranda, A.; González-Rodríguez, A.; Ruíz-Sánchez, E.; Luna-Vega, I.; Oyama, K. A multicriteria analysis for prioritizing areas for conservation of oaks (Fagaceae: Quercus) in Oaxaca, Southern Mexico. Trop Conserv Sci, 2017; 10:1-29; 10. [CrossRef]

- Dalmolin, D.A.; Tozetti, A.M., Pereira, M.J.R. Taxonomic and functional anuran beta diversity of a subtropical metacommunity respond differentially to environmental and spatial predictors. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Alroy, J. Current extinction rates of reptiles and amphibians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015;112(42):13003–13008. [CrossRef]

- McCallum, M.L. Amphibian decline or extinction? Current declines dwarf background extinction rate. J Herpetol, 2007; 41:483–491. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4498614.

- Wilson, L.D.; Johnson, J.D.; Mata-Silva, V.A. Conservation reassessment of the amphibians of Mexico based on the EVS measure. Amphib Reptile Conserv, 2013;7(1):97–127(e69). https://biostor.org/reference/192979.

- SEMARNAT. Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental– Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres– Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio– Lista de especies en riesgo. México. Diario Oficial de la Federación 30 diciembre, 2010.

- García-Mendoza, A. Integración del conocimiento florístico del estado. In Biodiversidad de Oaxaca; García-Mendoza, A.; Ordoñez, M.; Briones-Salas, M.; Eds.; Instituto de Biología, UNAM-Fondo Oaxaqueño para la Conservación, México, 2004; pp. 305–325.

- Contreras-Medina, R.; Luna-Vega, I. Species richness, endemism and conservation of Mexican gymnosperms. Biodiversity Conserv. 2007;16(6):1803–1821. [CrossRef]

- Lips, K.R.; Mendelson, J.R.; Muñoz-Alonso, A.; Canseco-Márquez, L.; Mulcahy, D.G. Amphibian population declines in montane southern Mexico: Resurveys of historical localities. Biol Conserv. 2004; 119(4):555–564. [CrossRef]

- Wake, D.B.; Papenfuss, T.J.; Lynch, J.F. Distribution of salamanders along elevational transects in Mexico and Guatemala. Tulane Publ Zool Bot, Suppl Publ. 1991; 1:303–319.

- Rovito, S.M.; Parra-Olea, G.; Vásquez-Almazán, C.R., Papenfuss, T.J.; Wake, D.B. Dramatic declines in neotropical salamander populations are an important part of the global amphibian crisis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(9):3231–3236. [CrossRef]

| Subprovinces | Km2 | S Amphibia | S Anura | S Caudata | S Caecilians | Amphibia Mx/Oax | Anura Mx/Oax | Caudata Mx/Oax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB | 1788.17 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 5/0 | 5/0 | 0/0 |

| MVO | 21262.73 | 33 | 24 | 9 | 0 | 27/13 | 18/5 | 9/8 |

| FT | 1134.21 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 7/0 | 7/0 | 0/0 |

| SMO | 17519.96 | 88 | 62 | 26 | 0 | 62/43 | 36/19 | 26/24 |

| PCG | 7975.92 | 28 | 25 | 3 | 0 | 4/1 | 2/1 | 2/0 |

| VCO | 2267.42 | 14 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 11/2 | 10/1 | 1/1 |

| MVC | 6662.62 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 8/1 | 8/1 | 0/0 |

| DIT | 2114.12 | 20 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 3/0 | 1/0 | 2/0 |

| SMC | 5816.08 | 44 | 37 | 6 | 1 | 11/01 | 7/0 | 4/1 |

| SMS | 12350.15 | 49 | 42 | 6 | 1 | 32/12 | 25/6 | 7/6 |

| PCP | 9262.06 | 21 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 7/0 | 7/0 | 0/0 |

| PCT | 4298.77 | 27 | 26 | 0 | 1 | 6/1 | 6/1 | 0/0 |

| No. Subprovinces | No endemics | Mexico endemics |

Oaxaca endemics | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 23 | 48 | 81 |

| 2 | 12 | 1 | 10 | 23 |

| 3 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 15 |

| 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 47 | 42 | 60 | 149 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).