1. Introduction

Pythagorean theorem stands as one of the most crucial theorems in elementary mathematics, with numerous known proofs and applications. The available literature on this topic is vast, and the selection discussed here is far from being comprehensive. In the interest of brevity, we begin with the established book [

1], delving into the historical development of the Pythagorean theorem, tracing its origins in different cultures and civilizations. It also provides more than 370 proofs of the theorem, showcasing different approaches and techniques used to demonstrate its validity. Additionally, the book discusses the implications and applications of the Pythagorean theorem beyond its basic form. This includes exploring how the theorem can be extended to non-right triangles (such as acute and obtuse triangles) through trigonometry and other geometric concepts. The book also touches on applications of the theorem in fields like geometry, physics, and engineering.

Kassie Smith in reference [

2] inquires about a more geometric proof for these concepts. Consequently, starting with the equation, they deduce that the combined area of two regular

n-gons with side lengths

a and

b respectively, equates to the area of a regular

n-gon with side length

c. This can be shown by multiplying both sides of the equation by a specific constant, which is essentially the area of a regular

n-gon with a side length of 1. Interestingly, for any given

, this assertion also serves as a way to derive Pythagorean theorem in reverse. Within this context, the Wallace-Bolyai-Gerwien decomposition theorem ([

3]) becomes applicable. This theorem suggests the existence of a decomposition of the smaller

n-gons into polygonal components, which can be rearranged to form the larger

n-gon. However, it’s important to note that the number of individual pieces involved in this process might be extensive. The reference [

4] proposes still another proof which is nonstandard as he does not use neither squares nor similarity of triangles. The author introduces a geometric demonstration of the aforementioned assertion concerning equilateral triangles employing arithmetical operations of triangular shapes.

In the following discussion, we present two theorems concerning the application of the Geometric Pythagorean relationship. The first theorem addresses triangles formed by connecting a point in the midsegment to the vertices, while the second theorem pertains to non-coplanar triangles formed by connecting the sides of the original triangle to a point in space.

2. Pythagorean concept for coplanar triangles formed from a point in the midsegment and the vertices of a triangle

Theorem 1 (Geometric Pythagorean Relationships within Triangular Midsegment Compositions).

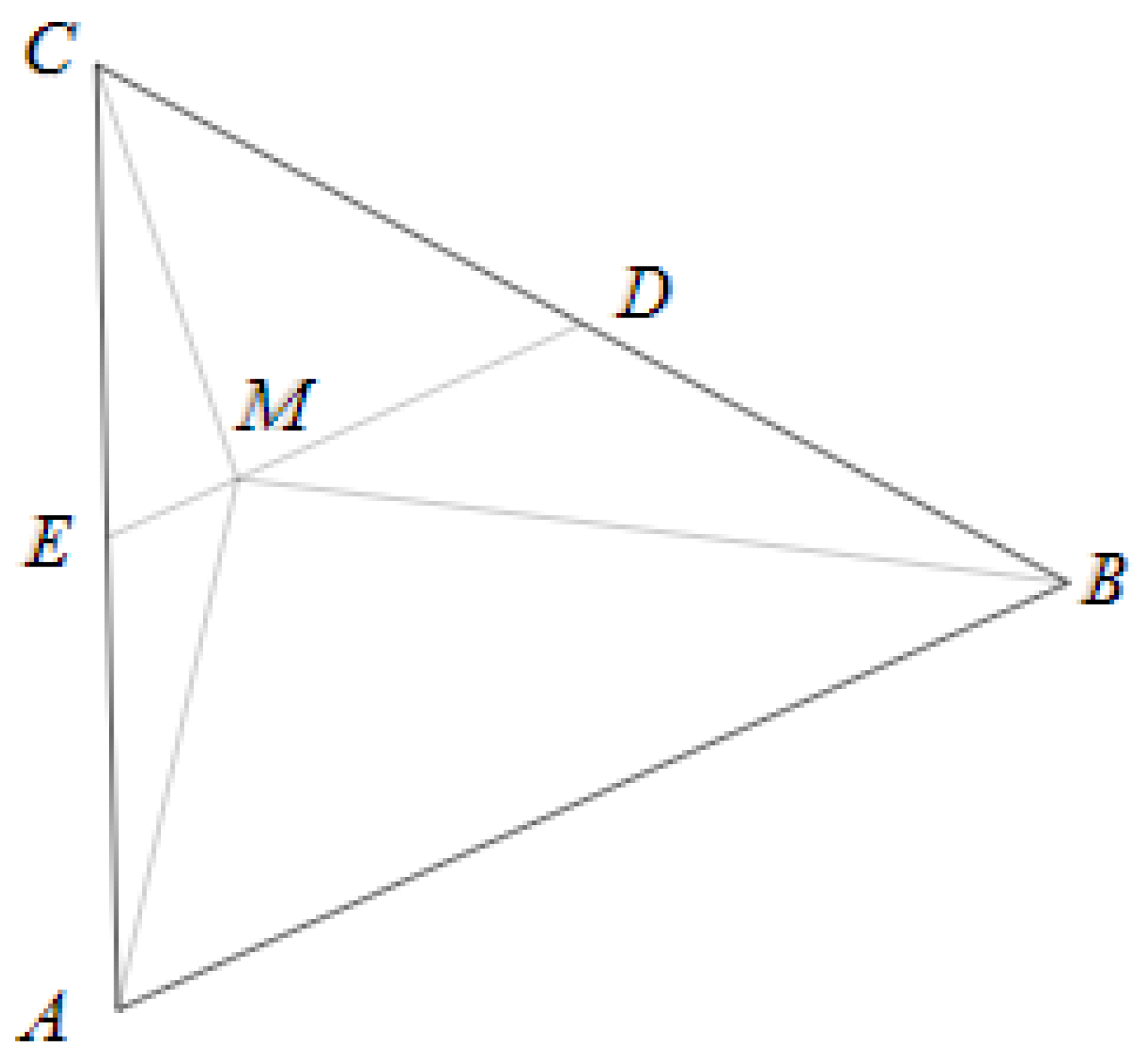

In Euclidean geometry, for any triangle and a point M lying on the midsegment connecting the midpoints of sides and , as depicted in Figure 1, the relationship between the areas of the three triangles , , and , is governed by the Geometric Proof of the Pythagorean theorem. Specifically, the sum of the areas of the triangles and is equal to the area of the triangle .

2.1. Definitions and Proof

Consider a generic triangle

, where

is the base, and

is the midsegment connecting the midpoints of sides

and

, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The Triangle Midsegment Theorem elucidates the properties of triangles and the relationship between their midpoints. According to this theorem, when the midpoints of the sides of a triangle are connected, four identical smaller triangles are formed.

Let

M be any point lying on the midsegment

. If the area of each triangle, formed by connecting the midpoints of the sides of a given triangle, is one-fourth the area of the original triangle

, the following statements for the internally constructed triangles further align with the Triangle Midsegment Theorem and its underlying principles. Thus, it holds true that

The summation of the areas of the triangles

and

is given by Equation (5)

Since

it can be demonstrated that, regardless of the size or shape of a triangle and for any point situated on the midsegment, the relationship between the areas of the three resultant internal triangles follows the principles of the Geometric Proof of the Pythagorean theorem, i.e. the sum of the areas of two smaller internal triangles given by Equation (5) is always equivalent to the area of the larger internal triangle provided by Equation (6). Hence,

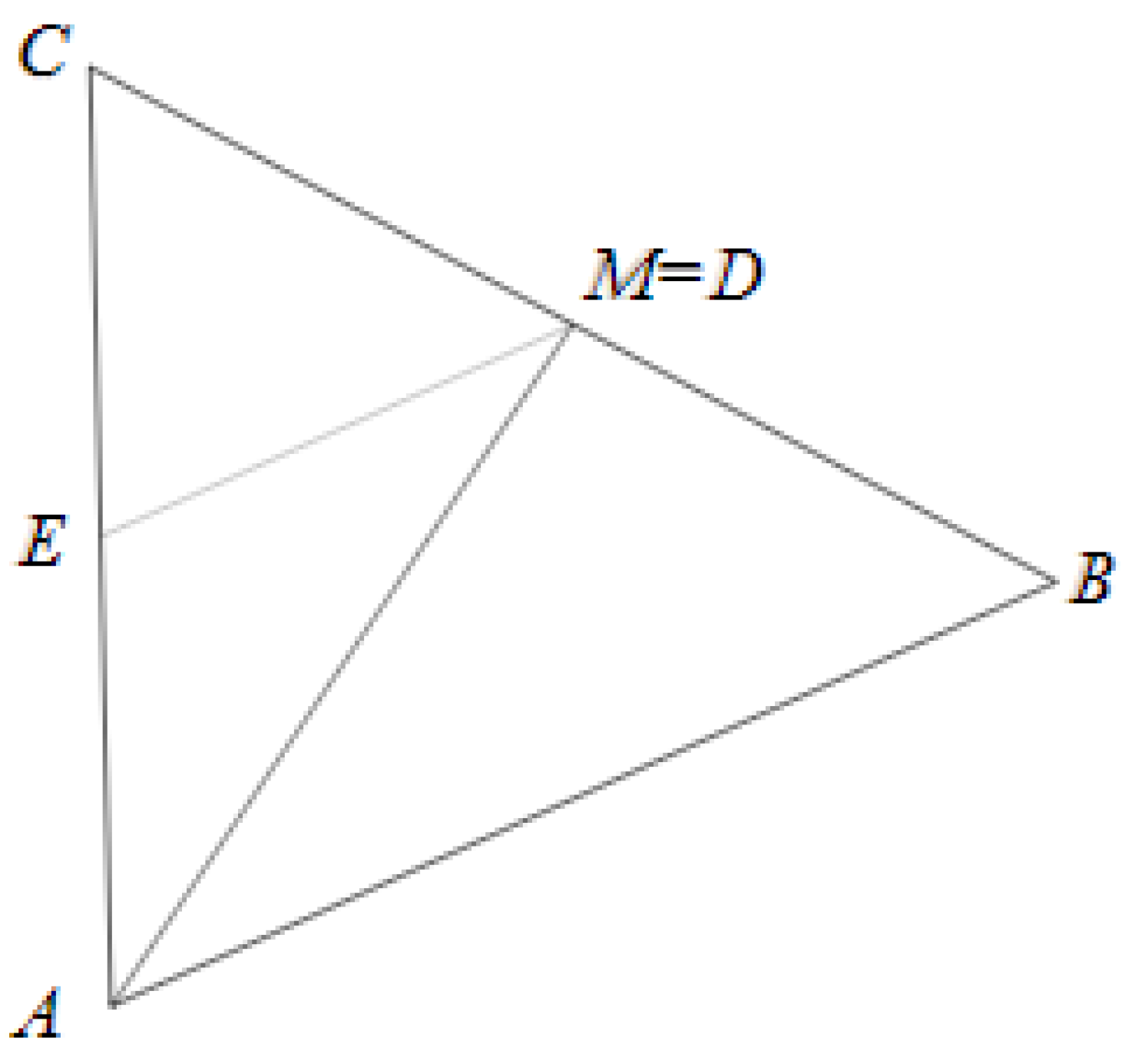

2.2. Special case for

For the case shown in

Figure 2 where

, it holds true that

Unsurprisingly, the relationship between the internal triangle continues to hold Equation (9) assertion.

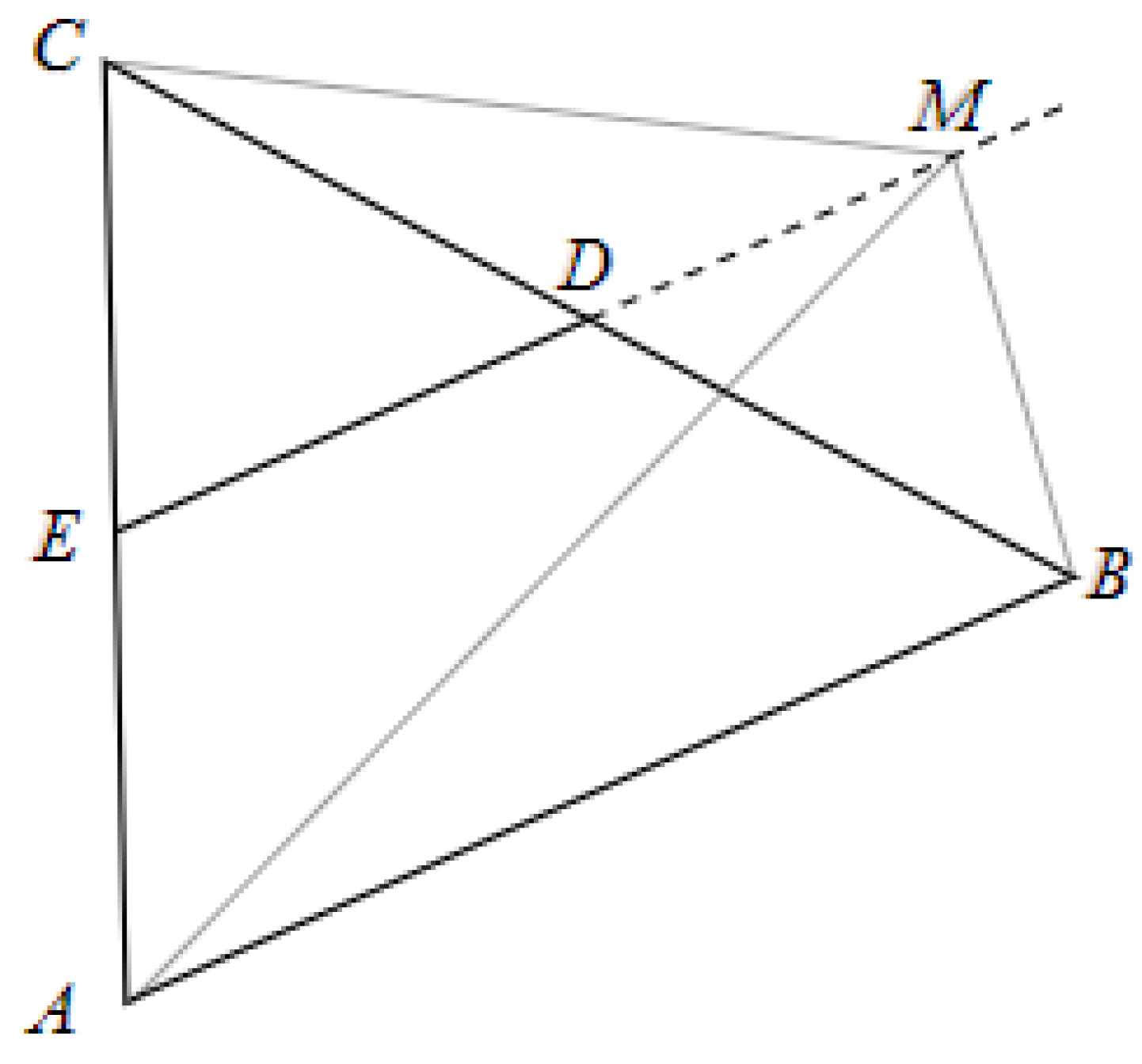

2.3. Theorem special case for

In the situation depicted in

Figure 3, where

M is not inside the

, the Pythagorean structure undergoes a transformation such that the Equation (7) becomes the relationship shown in Equation (10).

Precisely, the triangle

has been enlarged to become the largest among the three triangles, ensuring the preservation of the Pythagorean composition.

3. Extrapolating the Pythagorean structure into the 3D Space

Theorem 2 (Pythagorean Relationships in Three-Dimensional Geometric Structures Formed by Three-Dimensional Spatial Triangular Compositions). In a specific curvature-domain shape within three-dimensional space, a geometric configuration is established wherein the summation of the areas of two constituent triangles created by connecting the vertices of a generic triangle with a point in 3D space, specifically triangle and triangle , is invariably equivalent to the area of the encompassing triangle for any selection of points A, B, and C that form said triangles, equivalent to the geometric demonstration of the Pythagorean Theorem.

3.1. Definitions and Proof

Now let’s examine the general triangle

depicted in

Figure 4, in which

,

, and

represent its sides. The

,

and

arise by connecting the generic point

in three-dimensional space with

,

, and

.

The altitude

h and the altitude distance

l to the axis

y of the triangle

are here determined by the its area, computed using the compact Heron’s formula.

Hence,

h and

l may be expressed in the following manner:

We express the demonstration through a computationally efficient equation that necessitates only a single square root operation. The area of a triangle in coordinate geometry can calculated by the Equation (17), where

,

, and

are the vertices of a triangle in three-dimensional space.

In the subsequent iterations, we use Equation (17) to calculate the area of the triangles

,

and

respectively. For the triangle

where

Regarding the triangle

where

with

Concerning the triangle

where

Utilizing the Pythagorean geometric proof concept within the context of the irregular tetrahedron

yields three distinct solutions, as elucidated by Equation (23).

By substituting the terms from Equations (18), (19), (22) into (23), we derive three respective implicit solutions for the hypothesized theorem tailored specifically to tetrahedrons named here as

Pythagorean Tetrahedron:

It is important to note that the concepts introduced here should not be confused with the concept of the Trirectangular Tetrahedron or with De Gua’s theorem, [

5]. De Gua’s theorem asserts that when a tetrahedron contains a right-angle corner (similar to a corner on a cube), the sum of the squares of the areas of the three faces adjacent to the right-angle corner is equal to the square of the area of the face positioned opposite to that corner.

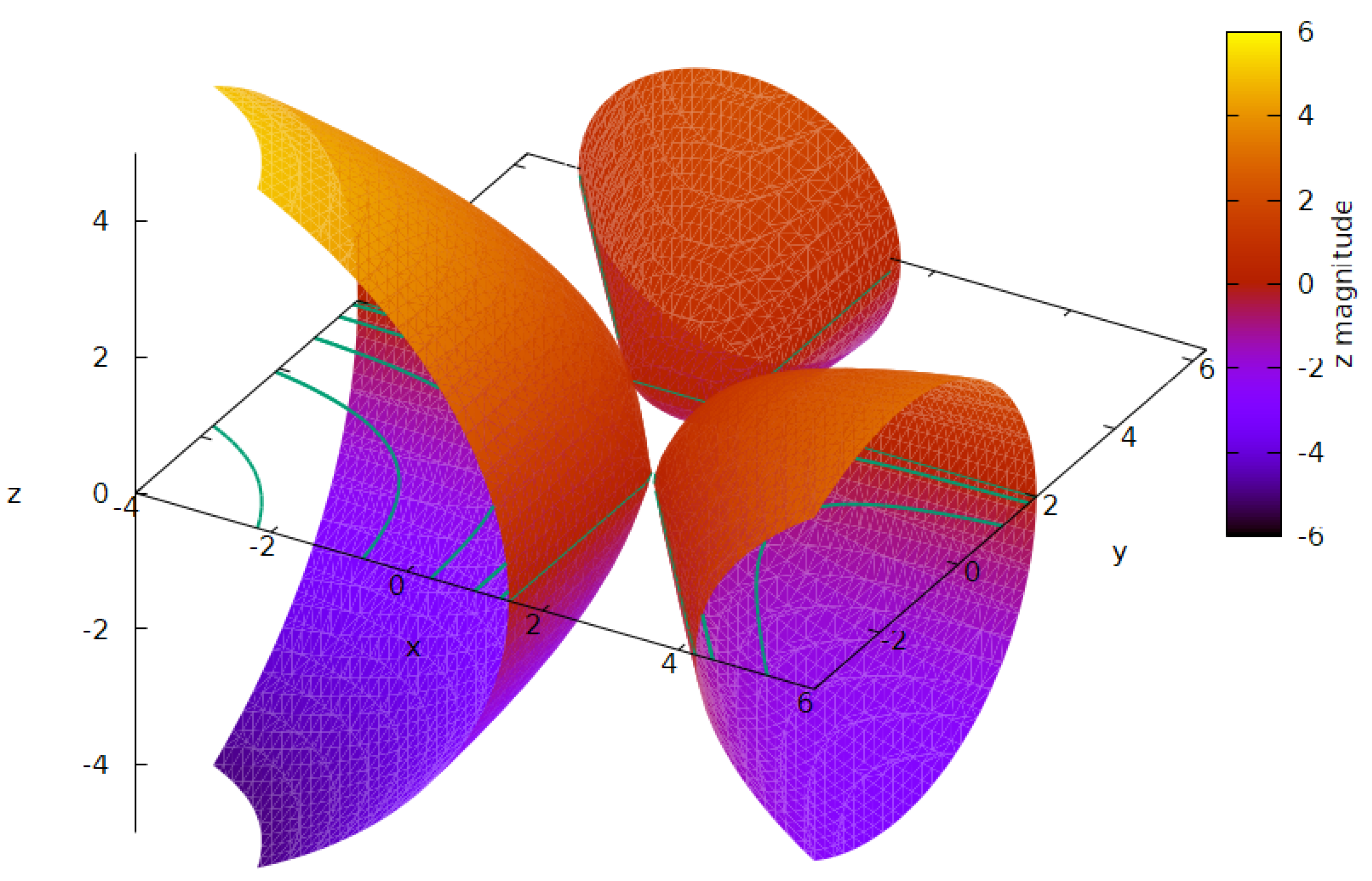

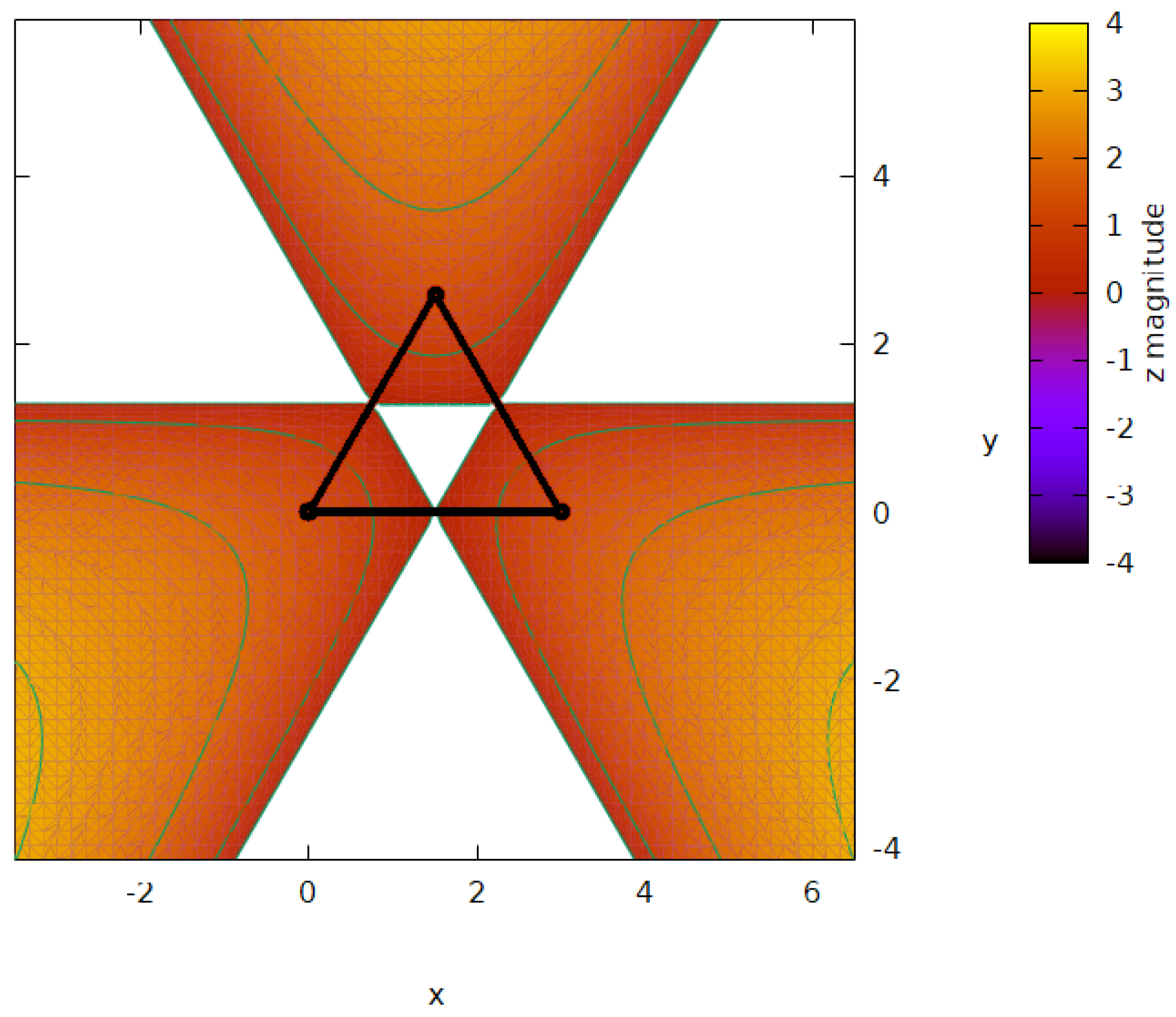

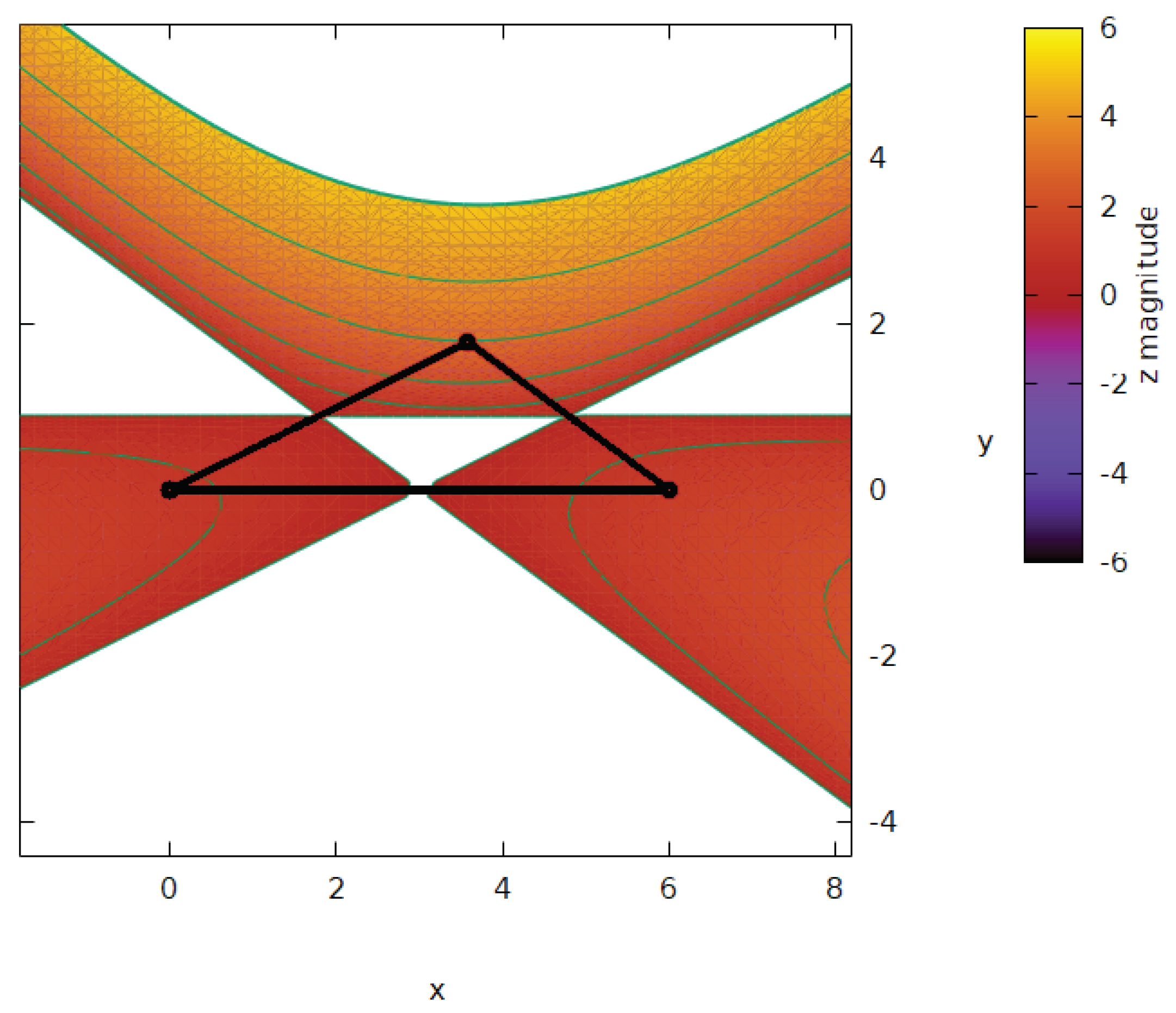

3.2. Graphic representation of the resultant curvature

In this segment, we present some illustrative three-dimensional graphical depictions of the solution of the implicit equations denoted as Equations (24), (25), and (26), corresponding to the conjectured theorem outlined in

Section 3 given the assistance of a computer algebra system (CAS).

We initiate the graphical depiction of resultant curvature using the archetypal right 3-4-5 triangle. By graphically representing Equations (24), (25), and (26), three bell-shaped tri-dimensional curvatures emerge outward from the midsegments of the triangle

, as portrayed in the visual representation labeled as

Figure 5. It is anticipated that these bell-curvatures will continue to grow indefinitely. Void spaces comprise the internal triangle enclosed by the midsegments, as well as three additional regions formed by extending these midsegments in a way that avoids intersecting the vertices of the prototypical triangle.

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate the projection of the resulting surface onto the

-plane, with the original triangle depicted using bold black lines, and the contour levels represented by green lines for 3-4-5 right, 3-3-3 isosceles, and 3-4-6 scalene triangles. The conjectured Theorem 1, as outlined in

Section 2, can be readily confirmed by observing the midsegments.

Therefore, as proposed, we have shown that the three inner triangles created by connecting a point on a midsegment with the triangle’s vertices adhere to the geometric verification of the Pythagorean theorem. Moreover, we have clarified the geometric connection, resembling an expanded version of the Pythagorean theorem, which reveals a distinct spatial surface defined by the Pythagorean interrelation of triangle areas for any triangle. Further endeavors should aim to develop an explicit formula for the newly introduced concepts in the current context.

Acknowledgments

Posthumous tributes are extended to Professor Dr. Pérides Silva for his pioneering insights into these conceptions.

References

- Loomi, E. S.,The Pythagorean Proposition: Its Demonstrations Analyzed and Classified, and Bibliography of Sources for Data of the Four Kinds of Proofs, Washington, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1968.

- Smith, K., Pythagorean Theorem, http://jwilson.coe.uga.edu/EMAT6680Fa2012/Smith/6690/pythagorean%20theorem/KLS_Pythagorean_Theorem.html, (Accessed: August 18, 2023).

- Wallace–Bolyai–Gerwien theorem, Wallace–Bolyai–Gerwien theorem — Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wallace–Bolyai–Gerwien_theorem, (Accessed: August 18, 2023).

- Navas A., The Pythagorean Theorem Via Equilateral Triangles, Math. Mag., vol. 93, no. 5, pp. 343–346, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gua de Malves, J.P. de. 1740. Usages de l’analyse de Descartes Pour Découvrir, sans Le Secours Du Calcul Differentiel, Les Propriétés, Ou Affections Principales Des Lignes Géometriques de Tous Les Ordres. Chez Briasson, libraire, ruë S. Jacques, à la science.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).