1. A Generalisation of Pythagoras’ Theorem

It has been canonical to associate Pythagoras’ theorem with the geometry of a triangle and De Gua’s theorem and higher dimensional analogues, with the geometry of a simplex. We, however, adopt a more general geometric interpretation. Namely, we state a new theorem, which yields the absolute value of an hyperplane of arbitrary shape in terms of its components,

where

,

X,

p and

d are the components of the hyperplane, the absolute value of the hyperplane, the dimension of the hyperplane and the overall dimension of the space respectively. We retrieve Pythagoras’ theorem,

for

and

. For

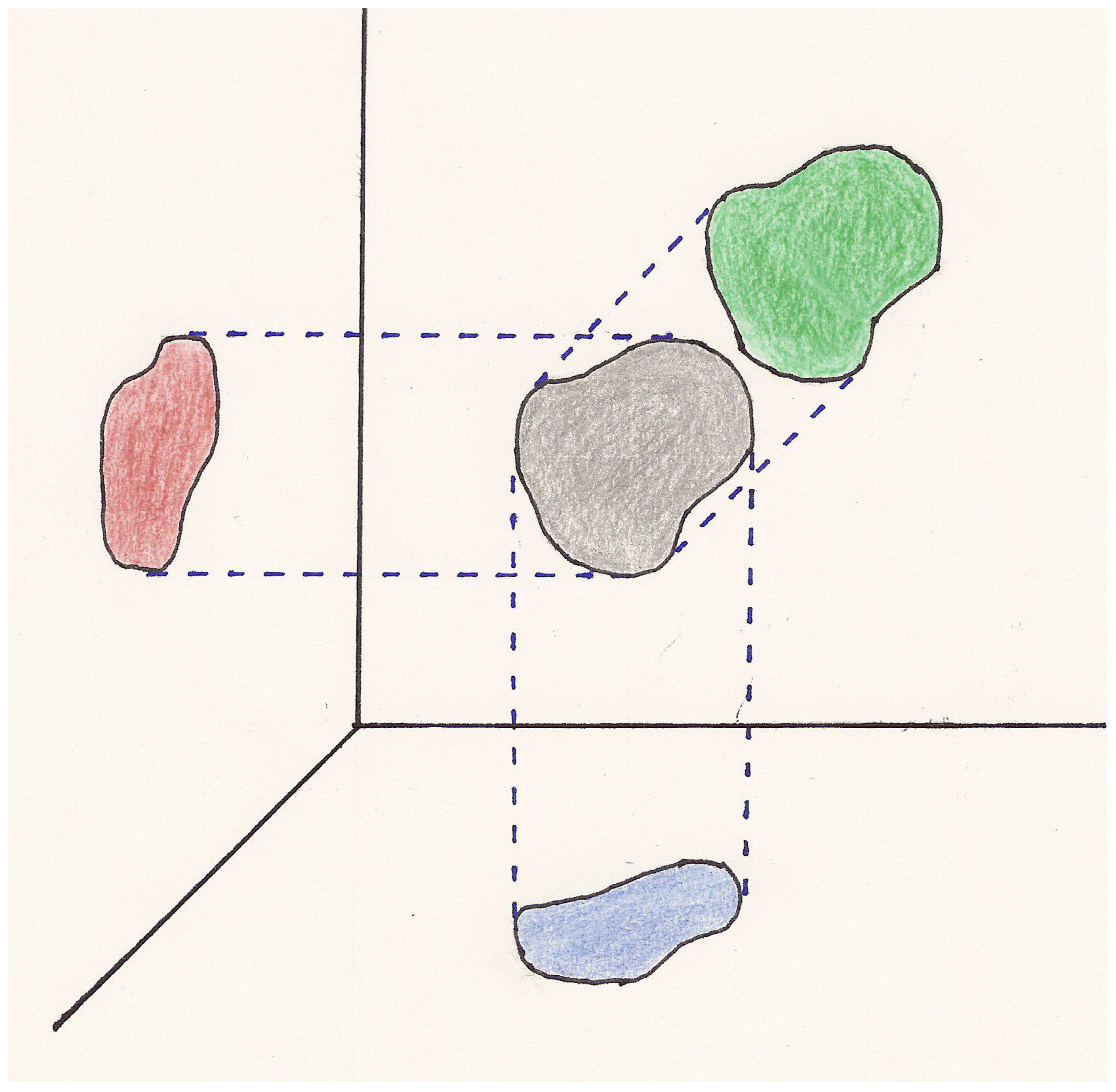

and

, we obtain a new theorem, which gives the absolute value,

X, of a plane of arbitrary shape, in terms of its components

where

and

c are the projections of the plane,

and

, onto the three planes, spanned by the coordinate axis axes. This theorem has geometric meaning, as is illustrated (

Figure 1).

2. Inner Product and Projections

The square of the absolute value of any hyperplane with arbitrary boundary is equal to sum of the squares of the absolute values of the projections of the hyperplane onto its basis elements. We argue that this insight is true in the trivial case, by realizing that we can always rotate any hyperplane, such that it has only one component.

For the sake of clarity, a hyperplane can be decomposed into its projections onto its basis elements as follows

where

are the basis vectors and where the components are the projections

. We recognize the theorem for hyperplanes (

1) as an inner product of an hyper plane (

2) with itself and derive the theorem this way. The inner product of the basis elements is equal to the Gram matrix

where

and

. This determines the inner product of two

p-forms,

x, and

y, in the following manner

where the absence of a sum sign implies Einstein summation convention. We now derive the theorem for hyper planes (

1),

Note that the theorem holds in relativistic spaces.

3. Hypersurfaces

We generalize the theorem for hyperplanes to a theorem for hypersurfaces. Letting the components to be infinitesimal,

, yields

where

is the absolute value of an infinitesimal hypersurface, where

are arbitrary coordinates and where the square brackets imply antisymmetrization. Whenever the metric is diagonal, we obtain

We conclude with three examples for clarification. We retrieve the line element,

for

.

Taking the root of both sides of the theorem for hypersurfaces, we obtain the

d-dimensional volume element

for

.

The calculation of the surface of a sphere goes as follows. Taking

,

and choosing the coordinates to be spherical coordinates, gives us

where the metric is given by

and

. The surface of a sphere is characterized by the radius being constant,

. If we then take the root and put in the appropriate integration boundaries, we get the value for the area

4. Historical Discussion

We believe the theorem of Pythagoras to be a most important theorem and also its generalisation. One might question the novelty of this work though. The Namu-Goto action, for instance,

also yields the absolute value of a two dimensional hypersurface, where

is a vector, which determines the shape of the hypersurface. It gives the absolute value, but it is unaware of the projections, the righthand sight of our the theorem for hypersurfaces, a generalisation of Pythagoras’ theorem. This is true, because the vector

is paramatrized by

and

, and moves only on the surface.

There is actually an older physics equation, the electromagnetic energy, which only captures the righthand sight of the theorem for hypersurfaces. We can recognize as the projection of an infinitesimal surface on the -plane. The absolute value of F is then given by .

References

- Bell, John L. (1999). The Art of the Intelligible: An Elementary Survey of Mathematics in its Conceptual Development. Kluwer. ISBN 0-7923-5972-0.

- Benson, Donald. The Moment of Proof : Mathematical Epiphanies, pp. 172-173 (Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Euclid (1956). The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements, Translated from the Text of Heiberg, with Introduction and Commentary. Vol. 1 (Books I and II). Translated by Heath, Thomas L. (Reprint of 2nd (1925) ed.). Dover. On-line text at archive.org.

- Heath, Sir Thomas (1921). "The ’Theorem of Pythagoras’". A History of Greek Mathematics (2 Vols.) (Dover Publications, Inc. (1981) ed.). Clarendon Press, Oxford. pp. 144 ff. ISBN 0-486-24073-8.v.

- Libeskind, Shlomo (2008). Euclidean and transformational geometry: a deductive inquiry. Jones and Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-4366-6.

- Loomis, Elisha Scott (1940). The Pythagorean Proposition (2nd ed.). Ann Arbor, Michigan: Edwards Brothers. ISBN 9780873530361.

- Maor, Eli (2007). The Pythagorean Theorem: A 4,000-Year History. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12526-8.

- Neugebauer, Otto (1969). The exact sciences in antiquity (2nd ed.). Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-22332-9. OCLC 638685764.

- Robson, Eleanor and Jacqueline Stedall, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the History of Mathematics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. pp. vii + 918. ISBN 978-0-19-921312-2.

- Stillwell, John (1989). Mathematics and Its History. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96981-0. Also ISBN 3-540-96981-0.

- van der Waerden, Bartel Leendert (1983). Geometry and Algebra in Ancient Civilizations. Springer. ISBN 3-540-12159-5. Pythagorean triples Babylonian scribes van der Waerden.

- Maor, E. (2019). The Pythagorean theorem: a 4,000-year history (Vol. 65). Princeton University Press.

- James Overduin, Richard Conn Henry (2020). Physics and the Pythagorean Theorem, arXiv:2005.10671.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).